Abstract

This study evaluated the effects of high-moisture corn (HMC), rumen-protected fat (CSFA), and organic zinc plus chromium (ZnCr) supplementation, alone or in combination, on feedlot performance, rumen microbiota, carcass traits, and feeding behavior of Nellore cattle with divergent marbling EPD. A total of 150 Nellore yearling bulls were classified into high and low EPD groups and assigned to five diets: (1) fine ground corn (FGC); (2) high-moisture corn (HMC); (3) FGC + calcium salts of fatty acids (FGC + CSFA); (4) HMC + CSFA; and (5) HMC + CSFA + ZnCr (organic zinc and chromium added). The HMC improved average daily gain and gain-to-feed ratio while reducing dry matter intake. The CSFA inclusion enhanced carcass traits and reduced incidence of rumenitis, improving rumen health. The ZnCr supplementation increased glucose availability and dressing percentage, especially in high-EPD animals. Genetic predisposition for marbling influenced dietary responses, with high-EPD bulls showing greater fat deposition and energy efficiency. Rumen microbiota composition was altered by corn processing, CSFA, and ZnCr, particularly affecting specific taxa such as Prevotella, Butyrivibrio, and Firmicutes. Feeding behavior and ruminal morphometry also varied with diet and genetic group. In conclusion, it is recommended to combine HMC and CSFA, while ZnCr proves to be most effective in marbling-genetically predisposed cattle.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The remarkable adaptability of ruminants to dietary challenges is attributed mainly to their symbiotic relationship with the microbial community in the rumen. Modern breeders and nutritionists have focused on enhancing this relationship to maximize microbial and host nutrition, as cattle derive most of their metabolizable energy from short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) produced by ruminal microbial fermentation1.

High-energy diets, particularly those rich in starch, increase ruminal propionate production, which serves as the primary gluconeogenic precursor for marbling2. Therefore, dietary strategies to improve beef marbling typically focus on increasing energy supply by maximizing starch fermentation in the rumen3 or lipid supplementation4. These strategies, however, have distinct effects on ruminal metabolism, starch fermentation increases fermentable substrate availability, whereas lipids do not contribute to ruminal energy supply. Excessive supplementation, in both cases, can affect ruminal metabolism by altering biofilm formation on feed particles and reducing the degradability of organic matter (OM) and dry matter (DM)5. Additionally, high lipid levels may affect hepatic metabolism through increased oxidation6, making ruminal fermentation modulators, such as rumen-protected fat in the form of calcium salts of fatty acids (CSFA), a viable strategy. Chung etal7. proposed that the physiological effects of SCFA and long-chain fatty acids (LCFA) on peripheral adipose tissues are mediated by G protein-coupled receptors, whose expression can be upregulated by propionate8. Corn-based diets9 or those supplemented with palmitic and stearic acids have been shown to stimulate the expression of the stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD) gene, which promotes the synthesis of oleic acid. Oleic acid, in turn, plays a significant role in de novo fatty acid synthesis from glucose in intramuscular adipocytes7,10.

Supplementation with zinc11 and chromium has also been associated with improvements in lipogenesis. However, the exact mechanisms underlying their roles in adipogenesis remain unclear. Oh etal12. reported that zinc supplementation stimulates glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase activity in intramuscular preadipocytes. This enzyme is also present in zinc finger protein 423 (ZFP423), a regulator of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), which is a key factor in adipocyte differentiation13. Chromium, on the other hand, primarily enhances insulin action, thereby increasing muscle and adipose tissue glucose uptake14. Bunting etal15. reported that dietary chromium picolinate supplementation in calves reduced blood glucose concentrations by improving insulin sensitivity.

From a genetic standpoint, marbling is a highly heritable trait in beef cattle, with expected progeny difference (EPD) exhibiting heritability estimates ranging from 0.40 to 0.5516,17. This means that a significant proportion of the variability in marbling scores can be attributed to genetic factors. However, despite its strong genetic basis, marbling expression is also influenced by nutritional and microbial factors, particularly during early developmental stages and throughout the finishing phase18. Strategies that enhance glucose availability by optimizing ruminal fermentation or providing alternative energy sources such as fats can modulate adipogenesis and improve marbling7,10.

We hypothesized that nutritional strategies combining high-moisture corn and rumen-protected fat, with or without organic zinc and chromium, would differentially modulate rumen microbiota composition and functionality, leading to improvements in feedlot performance, carcass traits, and rumen health, and that these effects would be influenced by the animal’s genetic predisposition for marbling. Based on this background and considering the high heritability of EPD for marbling, this study aimed to evaluate the effects of high-energy nutritional strategies, either through different corn grain processing methods or partial carbohydrate replacement by rumen-protected fat, with or without organic zinc and chromium, on feedlot performance, ruminal microbial community, carcass traits, and feeding behavior of Nellore cattle classified as having either high or low EPDs for marbling.

Materials and methods

All procedures with animals followed the relevant guidelines and regulations approved by the São Paulo State University, Brazil. All the experimental procedures were approved following the Ethical Committee for Animal Research (Protocol Number CEUA 0151/2019). We confirm that this study complied with the Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines.

Animals and treatments

The study was conducted at the São Paulo State University feedlot, Dracena campus, Brazil, beginning in July 2020 and lasting 112 days. One hundred and fifty 18-month-old Nellore yearling bulls with an initial body weight (BW) of 403.98 ± 23.90 kg were used. Bulls were from a commercial farm located in Bataguassu, Mato Grosso do Sul State, Brazil, which has been selecting Nellore bulls for three decades. The rancher borrowed the bulls for the university for this study. Before the start of the experiment, marbling data were obtained by ultrasound on day − 4, along with Expected Progeny Difference (EPD) values for animals whose parents had been evaluated. These values were used to classify the animals into high and low EPD for marbling. The experimental design followed a completely randomized block in a factorial arrangement of 2 × 2 + 1, with initial BW and the EPD used as blocking criteria.

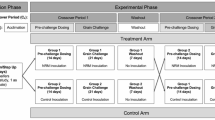

Nellore bulls were allocated in 30 pens (6.0 × 12.0 m; n = 5 animals per pen; 6 pens per treatment), and fed for 112 days, according to the treatments: [1] Finely-ground corn grain (FGC); [2] High-moisture corn grain (HMC); [3] FGC + CSFA (3.2% of diet DM; NutriGordura; Nutricorp, Araras, SP, Brazil;); [4] HMC + CSFA (3.2% of diet DM); [5] HMC + CSFA + ZnCr (organic zinc at 450 mg/kg DM and chromium at 750 mg/kg DM; Zinpro Animal Nutrition; Piracicaba, SP, Brazil). The design evaluated the main effects and interactions between corn processing method (FGC vs. HMC) and CSFA inclusion, plus an additional treatment combining HMC and CSFA with ZnCr supplementation (Fig. 1).

Schematic representation of the dietary treatments evaluated. Finely ground corn (FGC); High moisture corn (HMC); Finely ground corn associated with calcium salts of fatty acids (FGC + CSFA); high moisture corn associated with calcium salts of fatty acids (HMC + CSFA); high moisture corn associated with calcium salts of fatty acids and organic Zinc and Chromium (HMC + CSFA + ZnCr).

Feeding and management description

At the start of the study, all bulls were dewormed and vaccinated (tetanus, bovine viral diarrhea virus, 7-way Clostridium sp.; Cattlemaster and Bovishield, Pfizer Animal Health, New York, NY). They were fed ad libitum twice daily at 09:00 h (45% of the total ration) and 16:00 h (55% of the total ration), targeting 1% to 5% refusal. Water was provided ad libitum via a water trough (3.00 × 0.80 × 0.20 m). Experimental diets were formulated according to the Large Ruminant Nutrition System19 and are detailed in Table 1. The CSFA lipid profile data are presented in Supplementary Table S1.

The adaptation program consisted of three diets containing 69%, 74%, and 79% concentrate, fed ad libitum for 6, 5, and 9 days, respectively. Experimental diets included sugarcane bagasse, Cynodon dactylon hay, cracked corn grain, high-moisture corn grain, soybean meal, and urea supplement (Table 1).

Feed ingredient samples were analyzed for dry matter (DM) per charge received, and dietary DM was adjusted daily according to ingredient changes. Water was added to the diets to maintain an approximate DM content of 70%. Feed and diet samples were dried in a forced-air oven for DM determination20(method 930.15), ground to pass through a 1-mm screen, and analyzed for ether extract20(method 920.39), ash20(method 942.05), and crude protein20(method 990.02). Neutral detergent fiber (NDF) was determined using a Fiber Analyzer (A200; ANKOM Technology Corp., Fairport, NY) with α-amylase inclusion21.

The mean particle size of HMC and FGC was evaluated following Yu etal22.(Supplementary Table S2). The complete diet particle size was assessed (n = 3 per diet) using the Penn State Particle Size Separator23, with an additional sieve (1.18-mm pore size; Table 1).

Feeding behavior and particle sorting

Cattle were visually observed every five minutes over 24 h to evaluate feeding behavior. A team of twenty trained observers recorded the feeding behavior. The observers were divided into four groups of five, each collecting data for six hours. Each individual in a group was responsible for recording the feeding behavior of six pens (24 animals).

Visual observation was conducted only on day 107 of the study, following the methodology of Robles etal24.. Feeding behavior data were recorded for each animal, identified by ear tags, and included time spent eating, ruminating, and resting (expressed in minutes), as well as the number of meals per day. A meal was the uninterrupted period during which cattle remained at the feed bunk consuming the ration. Final data for each variable were averaged across animals within each pen.

The DMI was also measured per pen on the feeding behavior data collection day. Meal length (minutes) was calculated as the time spent eating divided by the number of meals per day. DMI per meal (kg) was determined by dividing total DMI by the number of meals per day. Additionally, time spent eating, and ruminating were used to calculate the eating rate of DM (time spent eating/DMI) and the rumination rate of DM (time spent ruminating/DMI), both expressed in minutes per kilogram of DM, following Pereira etal25..

Diet and ort samples were collected for neutral detergent fiber (NDF) analysis21 to determine NDF intake on the day of feeding behavior data collection. The eating rate of NDF was calculated as time spent eating divided by NDF intake, while the rumination rate of NDF was determined as time spent ruminating divided by NDF intake. Both rates were expressed in minutes per kilogram of NDF25.

On day 107 of the study, diet, and ort samples were also collected to determine particle-size distribution. The samples were assessed using a Penn State Particle Size Separator (PSPS) and reported on an as-fed basis, as described by Heinrichs and Kononoff26. Physically effective fiber (peNDF) in the diet was determined according to Kononoff etal27. as the proportion of DM retained by 19-, 8-, and 1.18-mm sieves of the PSPS, multiplied by dietary NDF. The eating rate of peNDF was calculated as time spent eating divided by peNDF intake, while the rumination rate of peNDF was determined as time spent ruminating divided by peNDF intake. Both rates were expressed in minutes per kilogram of peNDF.

Particle sorting was assessed using the ratio of actual to predicted intake for each particle fraction: 19 mm (long), 8 mm (medium), 1.18 mm (short), and pan (fine). A particle sorting value of 1 indicated no sorting, values < 1 indicated selective refusals (sorting against), and values > 1 indicated preferential consumption (sorting for), as described by Heinrichs and Kononoff26.

Feedlot performance, blood Profile, and carcass characteristics

At the beginning and end of the experimental period, bulls were withheld from feed for 16 h before BW assessment. Dry matter intake (DMI) was calculated daily by weighing the feed offered and orts before the next morning’s feeding, expressed in kilograms and as a percentage of BW. Average daily gain (ADG) and gain-to-feed ratio (G: F) were calculated at the end of the study. DMI variation was determined daily as the difference in intake between consecutive days28 and expressed in kilograms and percentage variation.

Net energy for maintenance (NEm) and net energy for gain (NEg) of diets were estimated using methods from Lofgreen and Garrett29, NRC30, and Zinn and Shen31.

Blood samples were collected at the beginning of the adaptation period, day 1, and the end of each experimental period, day 111, in the morning, before feeding. Blood was collected in three tubes of 10 mL with heparin via jugular venous puncture. Plasma samples were analyzed for non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA) content, which was determined with a colorimetric assay32; insulin (Elisa commercial kit) and glucose33(Elisa commercial kit).

At the beginning of the study, one animal per pen (n = 30) was randomly selected for carcass, rumen, and cecum evaluations, including ruminal protozoa and bacterial community composition. The remaining 120 animals were harvested at the study’s end. Cattle were transported 110 km (~ 3 h) to a commercial slaughterhouse. The final BW was recorded in the feedlot before harvest.

Animals were handled according to good welfare practices, and no additional experimental manipulation was performed prior to slaughter. Stunning was carried out using a penetrating captive bolt device, followed immediately by exsanguination, in accordance with Brazilian regulations for humane slaughter34. Anesthesia or analgesia was not required, as animals were not subjected to surgical interventions or painful experimental procedures before slaughter. Every effort was made to minimize stress and ensure animal welfare during handling and slaughter. Hot carcass weight (HCW) was recorded after kidney, pelvic, and heart fat removal. The dressing percentage was calculated as HCW divided by the final BW. The initial dressing percentage was estimated based on a regression equation developed from the 30 cattle slaughtered at the study’s beginning:

HCW daily gain, carcass transfer (proportion of live BW gain captured as HCW), and DMI:15-kg carcass ratio were calculated as follows:

Fat thickness at the 12th rib, Biceps femoris (BF) fat thickness, Longissimus muscle (LM) area, and marbling were measured via ultrasound at the beginning and end of the study35. Daily gains in these parameters were calculated as the difference between the two measurements divided by days on feed. Images were collected using an Aloka SSD-1100 Flexus RTU unit (Aloka Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) with a 17.2 cm, 3.5 MHz probe.

Rumen morphometrics

Rumenitis evaluation was recorded after cattle evisceration, and all thoroughly washed rumens were scored. The rumen epithelium was classified based on the presence of lesions (rumenitis) and abnormalities (e.g., clumped papillae) as described by Bigham and McManus36. Data was reported as a percentage of animals presenting evidence of rumenitis. All rumens were scored by two trained individuals blinded to the treatments, and the final data represent the average of both scores.

Additionally, a 1-cm2 fragment of each rumen was collected from the dorsal cranial sac and placed in a PBS solution for morphometric measurements following the methodology of Resende Júnior etal37.. The number of papillae per square centimeter of the rumen wall (NOP) was manually determined. Twelve papillae were randomly collected from each fragment scanned, and the mean papillae area (MPA) was determined using an image analysis system (Image Tool, version 2.01 alpha 4, UTHSCSA Dental Diagnostic Science, San Antonio, TX). The rumen wall absorptive surface area (ASA) in cm2 was calculated using the following equation:

where 1 represents the 1-cm2 fragment collected, and 0.002 is the estimated basal area of papillae in square centimeters. The papillae area, expressed as a percentage of ASA, was calculated as follows:

Protozoa counting and ruminal bacterial community composition

Samples for counting protozoa and studying the ruminal bacterial community composition were collected by cutting the animal’s rumen shortly after slaughter. 120 Nellore bulls were sequenced to characterize the rumen microbial community. Of these, 60 were classified as high EPD for marbling, while 60 were classified as low EPD for marbling. Within each group, 15 animals were sampled on day 0 for model fitting, and the remaining 45 were sampled on day 113.

Protozoa collection, preparation, counting, and differentiation followed the methodology described by Pinto etal38.. Samples were analyzed using a Neubauer Improved Bright-Line counting chamber (Hausser Scientific Partnership R, Horsham, PA, United States) with optical microscopy39(Olympus CH-2 R, Japan). Protozoa were differentiated by genus: Isotricha, Dasytricha, Entodinium, and Diplodinium.

For microbial community sequencing, 50 mL of rumen contents, including solid and liquid phases, were collected by a trained person wearing gloves to prevent contamination. Samples were stored in DNA- and RNA-free tubes, refrigerated, and kept at −80 °C. DNA extraction followed the methodology of Weimer et al40 and Pinto etal38.. After thawing, 10 mL of the contents were placed in a stomacher bag and 40 mL of DNA extraction buffer were added. A subsample of the recombined contents underwent DNA extraction using the bead-beating method40, which includes mechanical disruption using glass beads, followed by extraction with phenol: chloroform: isoamyl alcohol. The DNA was resuspended in 10 mM Tris HCl with 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), quantified fluorometrically using a Qubit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States), and stored at −80 °C prior to library preparation. Samples were diluted to 10 ng/µL to ensure a minimum of 50 ng per PCR reaction. The microbial DNA was amplified by PCR38 using universal primers to target the four variable regions of the bacterial 16 S rRNA gene (F-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA; R-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT) as described by Kozich etal41.. The primers also included unique barcodes for multiplexing and adapter suitable for sequencing using Illumina technology adapter suitable for sequencing using Illumina technology (F- TGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACAC; R-CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGAT; Kozich etal41.). Each reaction contained 50 ng of DNA, 0.4 µM of each primer, 12.5 µL of 2X Hot Start Ready Mix (KAPA Biosystems, Wilmington, MA, USA), and DNA/RNA-free water to a final volume of 25 µL. Cycling conditions were: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 25 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s, and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min.

Amplified products (25 µL) were loaded onto a low-melt agarose gel with five µL of 6X Orange loading dye. Samples displaying bright bands around 380 bp were excised for extraction and subsequent sequencing on an Illumina MiSeq platform (San Diego, CA, USA), using 5% PhiX as a control and MiSeq v4 kits (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA; Dill-McFarland etal42.). Sequences were demultiplexed using sample-specific indices on an Illumina MiSeq and deposited in the Short Read Archive of the National Center for Biotechnology Information under BioProject Accession PRJNA641164.

Non-bacterial DNA contamination was removed following Pinto etal38.. Reads were processed using Mothur software (v. 1.41.1)43. The SILVA 16 S rRNA gene reference alignment database (v132) was used for sequence alignment. Pre-clustering (diffs = 2) was performed to reduce errors, and chimeras were identified and removed using UCHIME44. Sequences were classified using the GreenGenes database45 with an 80% bootstrap cutoff. Sequences classified as cyanobacteria, mitochondria, Eukarya, or Archaea were removed. Unique reads were also removed to improve computational efficiency.

Statistical analysis

The experimental design followed a completely randomized block arrangement in a 2 × 2 + 1 factorial, with initial BW and marbling EPD used as a blocking criterion. The block and marbling EPD were included in the model as a random effect; however, the interaction between treatment and marbling EPD was considered fixed.

Pens were the experimental unit (n = 30; 5 bulls/pen), with each treatment replicated 6 times. On study day 1, one animal per pen was slaughtered to collect reference data. Data on feedlot performance, carcass traits, feeding behavior, and particle sorting were analyzed using the MIXED procedure of SAS (SAS Inst., Inc., Cary, NC) with Tukey’s test for mean comparisons. The model included the effects of corn processing (fine ground vs. high moisture), CSFA inclusion, the interaction between processing and CSFA, and the impact of adding organic zinc and chromium.

Analysis of variance for the finishing period included initial measurement covariates (BW, HCW, initial 12th rib fat, initial Biceps femoris fat thickness, initial marbling, initial rumen, and cecum data). Normality (Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests) and homogeneity of variance (GROUP option in SAS) were verified before statistical analysis. Significance was set at P ≤ 0.05.

Bacterial sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at 97% sequence similarity. Good’s coverage was calculated in Mothur, with a cutoff of ≥ 0.95 for sufficient sequencing depth. OTU counts were normalized to 10,000 sequences per sample for further analyses. Alpha diversity was assessed using Chao’s species richness estimate and Shannon’s diversity index. Differences in community diversity and richness were evaluated using a two-way ANOVA in R v3.2.1 (R Core Team). Beta diversity was assessed via non-metric multidimensional scaling using the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity metric. Community structure changes (relative abundance, Bray–Curtis metric) were evaluated using permutational multivariate ANOVA (PERMANOVA) in R (vegan package v2.5-2). Pairwise comparisons were performed using PERMANOVA, with p-values adjusted for false discovery rate (FDR) correction. For the relative abundances, the SIMPER procedure was used. The R code used in this study is provided in the Supplementary File S1.

Results

Performance and blood profile

A significant interaction between EPD and treatment classification was observed for the G: F ratio (P = 0.02; Table 2; Supplementary Fig. 1a), and for NEFA concentrations (P < 0.01; Table 2; Supplementary Fig. 1b), where cattle with low EPD fed with FGC or HMC + CSFA had higher serum NEFA levels.

The processing of corn significantly affected final BW (P = 0.03), ADG (P = 0.03), DMI (P < 0.01), and daily DMI as a percentage of BW (P < 0.01), with HMC improving weight gain and final BW while reducing DMI. Similarly, total DMI for the feedlot period differed between treatments (P < 0.01; Table 2). Similar to corn processing, CSFA inclusion improved final BW (P = 0.02), ADG (P = 0.02), and DMI during the adaptation period (P = 0.01; Table 2). Supplementation with organic ZnCr reduced G: F (P = 0.09; Table 2) and insulin levels (P = 0.02), but increased circulating glucose levels (P = 0.02; Table 2).

Feeding behavior and particle sorting

A significant interaction was observed between EPD and treatment classification, with effects on time spent ruminating (P = 0.03; Supplementary Fig. 2a), time spent eating (P = 0.03; Supplementary Fig. 2b), rumination rate of dry matter (DM; P = 0.03; Supplementary Fig. 2c), eating rate of DM (P = 0.03; Supplementary Fig. 2 d), rumination rate of neutral detergent fiber (NDF; P < 0.01; Supplementary Fig. 2e), eating rate of NDF (P = 0.01; Supplementary Fig. 2f), and, meal length (P = 0.03; Supplementary Fig. 3a). Animals with high EPD fed with FGC + CSFA spent more time ruminating. Cattle with low EPD fed with HMC spent more time eating, had a higher eating rate of DM, and had a lower rumination rate of DM and NDF compared to those with high EPD. Particle sorting analysis showed significant interactions for long (P < 0.01; Supplementary Fig. 3b) and medium particles (P = 0.03; Supplementary Fig. 3c). Animals with low EPD fed with HMC + CSFA or HMC + CSFA + ZnCr sorted more intensively for long and medium particles when compared to animals with high EPD.

Feeding behavior data revealed that HMC-treated animals had lower NDF intake (P < 0.01) and physically effective NDF (peNDF; P = 0.02; Table 3). The CSFA inclusion increased the number of meals per day (P = 0.02), reduced DMI per meal (P < 0.01), and decreased NDF (P < 0.01) and peNDF intake (P = 0.01; Table 3). Particle sorting analysis showed that CSFA reduced intake only through the pan screen (P < 0.01; Table 3). Supplementation with ZnCr increased NDF and peNDF intake (P ≤ 0.01) but reduced peNDF rumination efficiency (P = 0.02; Table 3).

Carcass characteristics

A significant interaction between EPD and treatment classification was found for carcass transfer (P < 0.01; Supplementary Fig. 4a), DMI:15-kg carcass (P = 0.01; Supplementary Fig. 4b), final LM area (P = 0.04; Supplementary Fig. 4c), final 12th rib fat thickness (P = 0.03; Supplementary Fig. 4 d), 12th rib fat daily gain (P = 0.03; Supplementary Fig. 4e), final backfat thickness (P < 0.01; Supplementary Fig. 4f), and for initial marbling scores (P < 0.01; Table 4; Supplementary Fig. 4 g), expressed as a percentage of the LM area. In both cases, the high EPD group exhibited greater marbling than the low EPD group.

The CSFA inclusion improved hot carcass weight (HCW; P = 0.02), daily carcass gain (P = 0.02), and daily backfat gain (P < 0.05; Table 4). Supplementation with ZnCr improved the dressing percentage (P = 0.02; Table 4).

Rumen morphometrics

Regarding rumen morphometrics, a significant interaction between EPD and treatment classification was found for the number of papillae (P < 0.01; Supplementary Fig. 5a), mean papillae area (P = 0.03; Supplementary Fig. 5b), and absorptive surface area (ASA; P < 0.01; Supplementary Fig. 5c). Cattle with low EPD fed with FGC had the highest number of papillae and ASA but a lower mean papillae area than those with high EPD fed with HMC.

Rumen morphometry data showed a significant effect of corn processing on the percentage of animals with rumenitis (P = 0.01; Table 5), with HMC increasing the incidence of ruminal lesions. In contrast to corn processing, CSFA inclusion reduced this percentage (P = 0.04; Table 5).

Ciliated protozoa counting and ruminal bacterial community

No significant interactions between EPD and treatment classification were found for protozoa counts. The Isotricha protozoa population differed between corn processing treatments (FGC: 0.96 and 4.34 vs. HMC 4.00, 5.99 and 5.88, respectively no or with CSFA, and ZnCr added; P = 0.03; Supplementary Table S3). Additionally, CSFA increased the Isotricha protozoa count (P = 0.01; Supplementary Table S3). Supplementation with ZnCr reduced the Dasytricha genus (HMC + CSFA + ZnCr, 1.27 vs. HMC 4.13 and 6.51, respectively no or with CSFA; P = 0.02; Supplementary Table S3) and total protozoa count (HMC + CSFA + ZnCr, 107.43 vs. HMC 154.54 and 123.55, respectively no or with CSFA; P < 0.01; Supplementary Table S3).

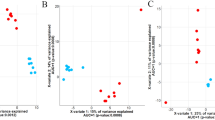

A total of 13,095,286 raw sequences were generated with an average of 78,414 +/−25,317 SD sequences per sample. After cleaning and filtering, the pooled samples contained an average of 6,829 unique OTUs, and a Good’s coverage ≥ 0.96. Richness estimates (Chao index) and diversity indices (Shannon index) are illustrated in Fig. 2a and b, showing significant differences in richness only between corn processing treatments (P < 0.01; Fig. 2d and e) and only a significant difference in diversity indices for the effect of ZnCr supplementation (P = 0.05; Fig. 2j and k). There are no significant differences in richness estimates or diversity indices for CSFA inclusion (Fig. 2g and h).

Alpha diversity (Shannon index and Chao estimator) and beta diversity (NMDS of Bray–Curtis dissimilarity) of ruminal microbial communities in the rumen of 18-month-old Nellore bulls fed high-energy diets. (a) Comparison of Shannon diversity index among treatments; (b) Comparison of Chao’s richness among treatments; (c) NMDS of Bray–Curtis distances among treatments; (d) Comparison of Shannon diversity index between FGC and HMC; (e) Comparison of Chao’s richness between FGC and HMC; (f) NMDS of Bray–Curtis distances between FGC and HMC; (g) Comparison of Shannon diversity index between treatments with or without CSFA; (h) Comparison of Chao’s richness between treatments with or without CSFA; (i) NMDS of Bray–Curtis distances between treatments with or without CSFA; (j) Comparison of Shannon diversity index HMC + CSFA and HMC + CSFA + ZnCr; (k) Comparison of Chao’s richness HMC + CSFA and HMC + CSFA + ZnCr; (l) NMDS of Bray–Curtis distances HMC + CSFA and HMC + CSFA + ZnCr. Finely ground corn (FGC); High moisture corn (HMC); Finely ground corn associated with calcium salts of fatty acids (FGC + CSFA); high moisture corn associated with calcium salts of fatty acids (HMC + CSFA); high moisture corn associated with calcium salts of fatty acids and organic Zinc and Chromium (HMC + CSFA + ZnCr). Effect of corn processing, Shannon (P = 0.17), Chao (P < 0.01); Effect of CSFA inclusion, Shannon (P = 0.30), Chao (P = 0.34); Effect of supplementation with ZnCr, Shannon (P = 0.05), Chao (P = 0.28). Bray-curtis effect’s on corn processing on Bray-curtis (P = 0.017); CSFA inclusion (P < 0.01); supplementation with ZnCr (P < 0.01). Arrows highlight the pairwise comparisons derived from treatment interactions.

Bray–Curtis dissimilarity analysis, visualized using NMDS (P < 0.01; Fig. 2c), indicated a significant effect of corn processing (Fig. 2f; P = 0.017), CSFA inclusion (Fig. 2i; P < 0.01), and ZnCr supplementation (Fig. 2l; P < 0.01).

Bacterial community analysis revealed differences in the relative abundance of the top seven phyla (Supplementary Figure S6). Differences in bacterial community classification were found for five operational taxonomic units (OTUs), including three from the genus Prevotella, one from Butyrivibrio, and one from the phylum Firmicutes (Supplementary Figure S7). Two OTUs from Prevotella and Firmicutes differed based on processing type (P < 0.05; Supplementary Figure S8).

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the effects of genetic predisposition for marbling (EPD classification) and nutritional strategies, with corn processing, CSFA inclusion, and supplementation with ZnCr, on animal performance, rumen microbiome and morphometrics, feeding behavior, and carcass characteristics in Nellore bulls. The findings highlight complex interactions between genetic and dietary factors, influencing multiple animal performance and metabolism aspects. We first evaluated how modifications in starch availability through corn processing can influence microbial community structure and, consequently, nutrient utilization and energy metabolism.

Nutritional interventions: grain processing and starch availability

Corn processing significantly influenced animal performance, with HMC improving final BW and ADG while reducing DMI. These findings align with research demonstrating improved starch digestibility and energy efficiency with HMC utilization46. Jurjanz & Monteils47 observed a ruminal starch degradability of 92.3% after ensiling, compared to 70.2% for unensiled grains. This increased starch availability explains the improvements in ADG by 0.105 kg and final BW by 11.79 kg in animals fed HMC, despite their DMI being 0.425 kg lower than those fed FGC. These findings contradict previous literature48,49, as HMC typically reduces DMI while maintaining ADG. The reduction in DMI observed with HMC feeding may be related to enhanced ruminal starch digestibility. In a companion study using the same dietary treatments in cannulated Nellore steers, HMC increased SCFA concentrations, particularly propionate, without affecting ruminal pH50. Therefore, the higher rumenitis scores observed in HMC-fed animals could be partially explained by shifts in ruminal fermentation, as suggested by these data from the companion study50. However, despite this increase, lesions were not severe enough to negatively impact performance. Furthermore, these animals exhibited a lower intake of neutral detergent fiber (NDF), indicating no signs of acidosis.

Interestingly, HMC processing influenced microbial community structure, as reflected by significant shifts in bacterial composition and Bray-Curtis dissimilarity metrics. Corn processing also increased microbial richness (Chao index), suggesting an expansion of the microbial community capable of exploiting a broader range of fermentable substrates, which likely enhances functional diversity and ruminal fermentation efficiency. Specifically, bacterial community analysis revealed changes in the relative abundance of key taxa, including three OTUs of Prevotella, one OTU of Butyrivibrio, and one OTU of Firmicutes. Prevotella, known for its broad metabolic capacity, is involved in the degradation of soluble carbohydrates and protein, producing SCFAs such as acetate and propionate, which contribute to energy availability51,52,53. The observed increase in Prevotella with HMC likely reflects the higher availability of readily fermentable starch. Butyrivibrio is associated with fiber degradation and butyrate production54, while Firmicutes, more abundant in diets with higher forage content, are linked to slower carbohydrate fermentation53. The reduction in Firmicutes alongside the increase in Prevotella and Butyrivibrio suggests a dietary shift toward faster starch fermentation, which may explain the observed differences in DMI and rumenitis scores. These changes highlight how corn processing modulates microbial composition and function, linking dietary interventions to ruminal fermentation dynamics and energy metabolism51,52,53,54.

These microbial community shifts, supported by beta diversity analyses, indicate that corn processing modulates ruminal fermentation dynamics by altering microbial composition and expanding functional potential, ultimately optimizing nutrient utilization and animal performance. Although changes in microbiota composition suggest potential shifts in ruminal fermentation pathways, we did not measure SCFA profiles.

However, Squizatti etal50., in a companion study using the same treatments in cannulated Nellore steers, found no differences in ruminal SCFA concentrations. These complementary findings support the idea that, despite lower DMI, HMC-fed animals maintained similar SCFA levels in our study. This helps explain the reduced DMI, since propionate is known to regulate feed intake6. Because starch from HMC is more readily available, less fermentable substrate is needed to produce equivalent SCFA amounts. Additionally, the inclusion of 20% FGC in our HMC diets likely delayed starch fermentation compared with diets in which all starch originated from HMC, thereby contributing to greater ruminal pH stability.

Next, we explored how rumen-protected fat supplementation interacts with dietary starch and affects feed intake patterns, microbial dynamics, and energy partitioning.

Nutritional interventions: CSFA supplementation and energy partitioning

Rumen-protected fat supplementation is a common practice in beef cattle diets to increase energy intake. However, the scientific literature has not yet reached a consensus on the effects of CSFA supplementation on DMI. According to a meta-analysis of 38 studies conducted by Rabiee etal55., this effect varies and generally depends on the type of fat supplied. In the present study, CSFA improved final body weight, average daily gain, and daily intake during the diet adaptation period. CSFA enhanced carcass traits, increasing hot carcass weight, daily carcass gain, and backfat accumulation. These findings align with previous studies highlighting the role of rumen-protected fat sources in improving energy utilization and deposition of adipose tissue56. Studies suggest that CSFA supplementation can increase intramuscular fat accumulation and improve carcass yield, especially in diets with high starch content57,58. This result is crucial for beef production systems aiming to enhance the quality of carcass traits without negatively impacting feed conversion efficiency.

From a rumen health perspective, CSFA supplementation mitigated the adverse effects observed with HMC, reducing the percentage of animals with rumenitis. This effect may be attributed to the lower fermentation rate of CSFA compared to starch sources, thereby reducing acid load and stabilizing ruminal pH59. However, changes in feeding behavior, including increased meal frequency and reduced meal size, suggest that CSFA alters feeding patterns to accommodate differences in energy partitioning.

Finally, we assessed the role of Zn and Cr supplementation in modulating glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity, with responses potentially influenced by genetic predisposition for marbling, highlighting gene × diet interactions.

Nutritional interventions: ZnCr supplementation and gene × diet interactions

The supplementation of ZnCr influenced multiple metabolic and physiological parameters in our study, particularly improving insulin efficiency and energy metabolism, which are critical for muscle growth and fat deposition. Organic chromium has been shown to potentiate insulin action by enhancing insulin receptor signaling and stimulating GLUT4 translocation, thereby increasing glucose uptake by muscle and adipose tissue60,61,62. Zinc plays complementary roles by stabilizing insulin structure, modulating key enzymes of carbohydrate metabolism, and protecting β-cells from oxidative stress63,64,65. Together, Zn and Cr may favor glucose utilization for glycogen synthesis and ATP production in muscle while limiting adipocyte glucose uptake. Consistent with these mechanisms, we observed reduced circulating insulin concentrations alongside higher glucose levels in ZnCr-fed steers, indicating enhanced insulin sensitivity and greater glucose availability for muscle accretion rather than lipogenesis. This metabolic shift likely contributed to the increase in dressing percentage observed in our trial, particularly in animals with a genetic predisposition for marbling (high EPD), supporting a gene × nutrient interaction66. The greater marbling response in high-EPD cattle may be explained by a gene × nutrient interaction, in which the improved insulin sensitivity and glucose utilization promoted by ZnCr provide additional metabolic precursors that high-EPD animals are genetically predisposed to channel into intramuscular adipogenesis. Low-EPD animals, having lower genetic potential for marbling, respond less to this metabolic stimulus.

Chromium supplementation has also been associated with increased propionate conversion to glucose in ruminants67,68,69,70, further contributing to enhanced glucose availability. Although we did not directly measure propionate metabolism, the observed metabolic responses align with this mechanism.

From a feeding behavior standpoint, ZnCr supplementation increased NDF and peNDF intake but reduced feeding and rumination efficiency, suggesting alterations in ruminal fermentation. Our microbial analyses confirmed significant shifts in community composition, including a reduction in Dasytricha protozoa, which may indicate a transition toward a bacterial-dominated fermentation system. Such microbial restructuring likely reduced protozoal-mediated starch fermentation, contributing to changes in fermentation pathways and nutrient utilization, and ultimately influencing host metabolism.

To link these nutritional effects with animal genetics, we analyzed differences between high and low EPD groups, evaluating how genetic background modulates microbial responses and energy utilization.

Genetic background: marbling EPD effects on microbiota and energy metabolism

Our study was conducted with contemporary animals from a farm evaluated through a genetic improvement program. The initial marbling level of 18-month-old Nellore bulls was 2.73% of the LM area for the high EPD group and 2.07% for the low EPD group. These values differed across all treatments between the low and high EPD groups. These data indicate that 18-month-old Nellore bulls exhibit different fat percentages in their body composition.

The observed interactions between treatment and EPD classification suggest that genetic predisposition for marbling influences how animals respond to dietary interventions. High-EPD animals consistently exhibited superior initial marbling scores, reinforcing the role of gene selection in meat quality71. Jurie etal72. evaluated different breeds with varying maturity levels and reported differences in their performance and muscle metabolism. These differences arise due to variations in the proportion of protein and fat in weight gain73. Diets rich in grains, which increase metabolizable energy (ME) and thus retain energy, tend to enhance fat deposition4. In our study, energy availability for gain increased between EPD groups as dietary energy levels rose. However, animals classified as low EPD seemed to require greater dietary increments to elevate these values.

When these findings are applied to carcass data, we observe that fat deposition increases more intensely in high EPD animals. In contrast, low EPD animals require greater dietary increments to reach similar fat deposition levels. This trend is also reflected in the gain-to-feed ratio (G: F) and DMI:15-kg carcass. As described by McMeekan74, tissue deposition follows a specific sequence: skeletal first, followed by muscle, and finally, fat. Fat deposition, in turn, follows an order: visceral, intermuscular, subcutaneous, and intramuscular. Additionally, the significant interactions for feed efficiency metrics (G: F ratio, biological efficiency, and gain yield) indicate that high-EPD animals may have a more efficient energy utilization pathway when exposed to specific dietary treatments75. Furthermore, differences in feeding behavior, including rumination rate and eating rate of both DM and NDF, suggest that genetic selection for marbling is associated with modifications in feeding patterns, potentially optimizing nutrient digestion.

However, because we used Nellore bulls (Bos indicus) in this study, both the relatively short feeding period and the inherent genetic characteristics of the breed may have limited intramuscular fat deposition. Bos indicus cattle generally exhibit lower marbling potential than Bos taurus, tending to deposit subcutaneous fat before intramuscular fat, even under extended finishing periods76. Thus, while longer feeding durations can increase marbling in Bos indicus77, the rate and maximum achievable level remain considerably lower than in Bos taurus.

Intramuscular fat is a late-developing lipid deposit, with 50–75% of acetyl units for lipogenesis derived from glucose2. This fat deposit enhances meat juiciness and palatability, making it desirable to consumers78. Therefore, as proposed in this study, dietary strategies that optimize starch fermentation in the rumen could be key to intramuscular fat development. The liquid energy for gain (ELg) values improved and remained stable across EPD groups when using HMC diets.

Regarding rumen morphometry, diets containing only FGC reduced the absorptive surface area (ASA) in high EPD animals compared to low EPD animals. High EPD animals tended to have fewer ruminal papillae as dietary energy levels increased, whereas low EPD animals maintained constant papillae count across diets. However, the average papillae area tended to decrease in low EPD animals as dietary energy increased.

Although the study was conducted under feedlot conditions, the relatively short finishing period and use of only Nellore bulls may limit the extrapolation of results to other Bos indicus or Bos taurus breeds with different fat deposition patterns and marbling potential. Additionally, the lack of lipidomic analyses precludes detailed evaluation of intramuscular fatty acid composition. Despite these limitations, the nutritional strategies evaluated had a significant impact on performance, ruminal microbiota, and carcass traits, highlighting their potential for practical application.

In summary, diets based on high-moisture corn combined with rumen-protected fat improved feedlot performance and positively influenced carcass traits in Nellore yearling bulls. These nutritional strategies were also associated with shifts in the rumen bacterial community, most notably an increase in the relative abundance of Prevotella, which may underlie changes in ruminal fermentation and energy availability. Supplementation with organic zinc and chromium produced genotype-dependent effects, enhancing dressing percentage and markers of glucose availability, particularly in animals with higher marbling EPD. Taken together, our results suggest that integrating corn processing and protected fat can be a valuable approach to enhance production efficiency while considering genetic background; however, longer-term trials and direct measurements of intramuscular lipid composition and ruminal fermentation metabolites are necessary to confirm the effects on marbling and lipid metabolism.

Data availability

Sequences were deposited in the Short Read Archive of the National Center for Biotechnology Information under BioProject Accession PRJNA641164.

References

Perea, K. et al. Feed efficiency phenotypes in lambs involve changes in ruminal, colonic, and small-intestine-located microbiota. J. Anim. Sci. 95, 2585–2592 (2017).

Smith, S. B. & Crouse, J. D. Relative contributions of acetate, lactate and glucose to lipogenesis in bovine intramuscular and subcutaneous adipose tissue. J. Nutr. 114, 792–800 (1984).

Owens, F. N., Secrist, D. S., Hill, W. J. & Gill, D. R. The effect of grain source and grain processing on performance of feedlot cattle: a review. J. Anim. Sci. 75, 868 (1997).

Krehbiel, C. R., Cranston, J. J. & McCurdy, M. P. An upper limit for caloric density of finishing diets1,2. J. Anim. Sci. 84, E34–E49 (2006).

Hess, B. W., Moss, G. E. & Rule, D. C. A decade of developments in the area of fat supplementation research with beef cattle and sheep1. J. Anim. Sci. 86, E188–E204 (2008).

Allen, M. S., Bradford, B. J. & Oba, M. BOARD-INVITED REVIEW: The hepatic oxidation theory of the control of feed intake and its application to ruminants. J. Anim. Sci. 87, 3317–3334 (2009).

Chung, K. Y., Smith, S. B., Choi, S. H. & Johnson, B. J. Oleic acid enhances G protein coupled receptor 43 expression in bovine intramuscular adipocytes but not in subcutaneous adipocytes1. J. Anim. Sci. 94, 1875–1883 (2016).

Hong, Y. H. et al. Acetate and propionate short chain fatty acids stimulate adipogenesis via GPCR43. Endocrinology 146, 5092–5099 (2005).

Chung, K. Y., Lunt, D. K., Kawachi, H., Yano, H. & Smith, S. B. Lipogenesis and stearoyl-CoA desaturase gene expression and enzyme activity in adipose tissue of short- and long-fed Angus and Wagyu steers fed corn- or hay-based diets. J. Anim. Sci. 85, 380–387 (2007).

Ladeira, M. M., Neto, M., Chizzotti, O. R., Oliveira, M. L. & Chalfun Junior, A. Lipids in the diet and the fatty acid profile in beef: A review and recent patents on the topic. Recent. Pat. Food Nutr. Agric. 4, 123–133 (2012).

Spears, J. W. & Kegley, E. B. Effect of zinc source (zinc oxide vs zinc proteinate) and level on performance, carcass characteristics, and immune response of growing and finishing steers. J. Anim. Sci. 80, 2747 (2002).

Oh, Y. S. & Choi, C. B. Effects of zinc on lipogenesis of bovine intramuscular adipocytes. Asian-Australasian J. Anim. Sci. 17, 1378–1382 (2004).

Gupta, R. K. et al. Transcriptional control of preadipocyte determination by Zfp423. Nature 464, 619–623 (2010).

Mertz, W. Chromium in human nutrition: A review. J. Nutr. 123, 626–633 (1993).

Bunting, L. D., Fernandez, J. M., Thompson, D. L. & Southern, L. L. Influence of chromium picolinate on glucose usage and metabolic criteria in growing Holstein calves2. J. Anim. Sci. 72, 1591–1599 (1994).

Wulf, D. M. et al. Genetic influences on beef longissimus palatability in Charolais- and Limousin-Sired steers and heifers. J. Anim. Sci. 74, 2394–2405 (1996).

Van Eenennaam, A. L. et al. Validation of commercial DNA tests for quantitative beef quality traits. J. Anim. Sci. 85, 891–900 (2007).

Smith, S. B. et al. Cellular regulation of bovine intramuscular adipose tissue development and composition. J. Anim. Sci. 87 (2009).

Fox, D. G. et al. The Cornell net carbohydrate and protein system model for evaluating herd nutrition and nutrient excretion. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 112, 29–78 (2004).

AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC (Association of Official Analytical Chemists, 1990).

Van Soest, P. J., Robertson, J. B. & Lewis, B. A. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy. Sci. 74, 3583–3597 (1991).

Yu, P., Huber, J. T. T., Santos, F. A. P. A. P., Simas, J. M. M. & Theurer, C. B. B. Effects of ground, steam-flaked, and steam-rolled corn grains on performance of lactating cows. J. Dairy. Sci. 81, 777–783 (1998).

Lammers, B. P., Buckmaster, D. R. & Heinrichs, A. J. A simple method for the analysis of particle sizes of forage and total mixed rations. J. Dairy. Sci. 79, 922–928 (1996).

Robles, V., González, L. A., Ferret, A., Manteca, X. & Calsamiglia, S. Effects of feeding frequency on intake, ruminal fermentation, and feeding behavior in heifers fed high-concentrate diets. J. Anim. Sci. 85, 2538–2547 (2007).

Pereira, M. C. S. et al. Effects of different doses of sodium monensin on feeding behaviour, dry matter intake variation and selective consumption of feedlot Nellore cattle. Anim. Prod. Sci. 55, 170–173 (2014).

Heinrichs, J. & Kononoff, P. Evaluating particle size of forages and TMRs using the New Penn State Forage Particle Separator. 14 at (1996).

Kononoff, P. J., Heinrichs, A. J. & Buckmaster, D. R. Modification of the Penn state forage and total mixed ration particle separator and the effects of moisture content on its measurements. J. Dairy. Sci. 86, 1858–1863 (2003).

Bevans, D. W., Beauchemin, K. A., Schwartzkopf-Genswein, K. S., McKinnon, J. J. & McAllister, T. A. Effect of rapid or gradual grain adaptation on subacute acidosis and feed intake by feedlot cattle1,2. J. Anim. Sci. 83, 1116–1132 (2005).

Lofgreen, G. P. & Garrett, W. N. A system for expressing net energy requirements and feed values for growing and finishing beef cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 27, 793–806 (1968).

National Academies of Sciences, E. and M. Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cattle: Eighth Revised Edition. Nutr. Requir. Beef Cattle, 8th Revis. Ed. https://doi.org/10.17226/19014 (2016).

Zinn, R. A. & Shen, Y. An evaluation of ruminally degradable intake protein and metabolizable amino acid requirements of feedlot calves. J. Anim. Sci. 76, 1280–1289 (1998).

Eisemann, J. H., Huntington, G. B. & Ferrell, C. L. Effects of dietary clenbuterol on metabolism of the hindquarters in steers. J. Anim. Sci. 66, 342 (1988).

Cooke, R. F. & Arthington, J. D. Concentrations of haptoglobin in bovine plasma determined by ELISA or a colorimetric method based on peroxidase activity. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl). 97, 531–536 (2013).

MAPA (Ministério da Agricultura, P. e A. Decreto no 9.013, de 29 de março de 2017. Regulamento da Inspeção Industrial e Sanitária de Produtos de Origem Animal (RIISPOA). MAPA, (2017).

Perkins, T. L., Green, R. D. & Hamlin, K. E. Evaluation of ultrasonic estimates of carcass fat thickness and longissimus muscle area in beef cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 70, 1002–1010 (1992).

Bigham, M. L. & McManus, W. R. Whole wheat grain feeding of lambs. V.* effects of roughage and wheat grain mixtures. Aust J. Agric. Res. 26, 1053–1062 (1975).

de Resende-Junior, J. C. et al. Effect of the feeding pattern on rumen wall morphology of cows and sheep. Brazilian J. Vet. Res. Anim. Sci. 43, 526–536 (2006).

Pinto, A. C. J. et al. Ruminal fermentation pattern, bacterial community composition, and nutrient digestibility of Nellore cattle submitted to either nutritional restriction or intake of concentrate feedstuffs prior to adaptation period. Front. Microbiol. 11, 553979 (2020).

Burk, A. D. Laboratory manual for classification and morphology of rumen ciliate protozoa. Lab. Man. Classif. Morphol. Rumen Ciliate Protozoa. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781351073912 (2018).

Weimer, P. J., Stevenson, D. M., Mantovani, H. C. & Man, S. L. C. Host specificity of the ruminal bacterial community in the dairy cow following near-total exchange of ruminal contents1. J. Dairy. Sci. 93, 5902–5912 (2010).

Kozich, J. J., Westcott, S. L., Baxter, N. T., Highlander, S. K. & Schloss, P. D. Development of a dual-index sequencing strategy and curation pipeline for analyzing amplicon sequence data on the miseq illumina sequencing platform. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 5112 (2013).

Dill-McFarland, K. A., Breaker, J. D. & Suen, G. Microbial succession in the gastrointestinal tract of dairy cows from 2 weeks to first lactation. Sci. Rep. 7, 40864 (2017).

Schloss, P. D. et al. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 7537–7541 (2009).

Edgar, R. C. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods. 10, 996–998 (2013).

DeSantis, T. Z. et al. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 5069–5072 (2006).

Coulson, C. A. et al. Impact of different corn milling methods for high-moisture and dry corn on finishing cattle performance, carcass characteristics, and nutrient digestion. J. Anim. Sci. 101, skac385 (2023).

Jurjanz, S. & Monteils, V. Ruminal degradability of corn forages depending on the processing method employed. Anim. Res. 54, 3–15 (2005).

Caetano, M. et al. Effect of flint corn processing method and roughage level on finishing performance of Nellore-based cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 93, 4023–4033 (2015).

Caetano, M. et al. Impact of flint corn processing method and dietary starch concentration on finishing performance of Nellore bulls. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 251, 166–175 (2019).

Squizatti, M. M. et al. Nutritional protocols that alter ruminal fermentation and nutrient disappearance to increase marbling precursors in Nellore cattle. Livest. Sci. 299, 105758 (2025).

Li, F. et al. Host genetics influence the rumen microbiota and heritable rumen microbial features associate with feed efficiency in cattle. Microbiome. 7 (2019).

Stevenson, D. M. & Weimer, P. J. Dominance of prevotella and low abundance of classical ruminal bacterial species in the bovine rumen revealed by relative quantification real-time PCR. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 75, 165–174 (2007).

Hernandez-Sanabria, E. et al. Impact of feed efficiency and diet on adaptive variations in the bacterial community in the rumen fluid of cattle. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 1203–1214 (2012).

Palevich, N. et al. Comparative genomics of rumen Butyrivibrio spp. uncovers a continuum of polysaccharide-degrading capabilities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 86, e01993–e01919 (2019).

Rabiee, A. R. et al. Effect of fat additions to diets of dairy cattle on milk production and components: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. J. Dairy. Sci. 95, 3225–3247 (2012).

Nascimento, F. A. et al. Calcium salts of fatty acids with varying fatty acid profiles in diets of feedlot-finished Bos indicus bulls: impacts on intake, digestibility, performance, and carcass and meat characteristics. J. Anim. Sci. 98 (2020).

Zinn, R. A. Influence of level and source of dietary fat on its comparative feeding value in finishing diets for feedlot steers: metabolism. J. Anim. Sci. 67, 1038–1049 (1989).

Costa, D. M. et al. Performance, carcass traits and meat quality of lambs fed with increasing levels of high-oleic sunflower cake. Agriculture 15, 191 (2025).

Manriquez, D., Chen, L., Melendez, P. & Pinedo, P. The effect of an organic rumen-protected fat supplement on performance, metabolic status, and health of dairy cows. BMC Vet. Res. 15, 450 (2019).

Vincent, J. B. Mechanisms of chromium action: Low-molecular-weight chromium-binding substance. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 18, 6–12 (1999).

Havel, P. J. A scientific review: the role of chromium in insulin resistance. Diabetes Educ. Suppl., 2–14 (2004).

Cefalu, W. T. & Hu, F. B. Role of chromium in human health and in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 27, 2741–2751 (2004).

Chausmer, A. B. Zinc, insulin and diabetes. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 17, 109–115 (1998).

Kambe, T., Taylor, K. M. & Fu, D. Zinc transporters and their functional integration in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 296, (2021).

Jansen, J., Karges, W. & Rink, L. Zinc and diabetes — clinical links and molecular mechanisms. J. Nutr. Biochem. 20, 399–417 (2009).

Spears, J. W., Lloyd, K. E. & Krafka, K. Chromium concentrations in ruminant feed ingredients. J. Dairy. Sci. 100, 3584–3590 (2017).

Spears, J. W. et al. Chromium propionate enhances insulin sensitivity in growing cattle. J. Dairy. Sci. 95, 2037–2045 (2012).

Bernhard, B. C. et al. Chromium supplementation alters the performance and health of feedlot cattle during the receiving period and enhances their metabolic response to a lipopolysaccharide challenge1–3. J. Anim. Sci. 90, 3879–3888 (2012).

Kneeskern, S. G., Dilger, A. C., Loerch, S. C., Shike, D. W. & Felix, T. L. Effects of chromium supplementation to feedlot steers on growth performance, insulin sensitivity, and carcass characteristics1. J. Anim. Sci. 94, 217–226 (2016).

Sano, H., Mowat, D., Ball, R. & Trout, D. Effect of supplemental chromium on whole-body kinetics of glucose, lactate, and propionate in Rams fed a high grain diet. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 118, 117–121 (1997).

Nguyen, D. V., Nguyen, O. C. & Malau-Aduli, A. E. O. Main regulatory factors of marbling level in beef cattle. Vet. Anim. Sci. 14, 100219 (2021).

Jurie, C. et al. Adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein and mitochondrial enzyme activities in muscles as relevant indicators of marbling in cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 85, 2660–2669 (2007).

Owens, F. N., Gill, D. R., Secrist, D. S. & Coleman, S. W. Review of some aspects of growth and development of feedlot cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 73, 3152–3172 (1995).

McMeekan, C. P. Growth and development in the pig, with special reference to carcass quality characters. I1. J. Agric. Sci. 30, 276–343 (1940).

Archer, J. A., Richardson, E. C., Herd, R. M. & Arthur, P. F. Potential for selection to improve efficiency of feed use in beef cattle: a review. Aust J. Agric. Res. 50, 147–162 (1999).

Bressan, M. C., Rodrigues, E. C., Rossato, L. V., Ramos, E. M. & da Gama, L. T. Physicochemical properties of meat from Bos taurus and Bos indicus. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 40, 1250–1259 (2011).

Bruns, K. W., Pritchard, R. H. & Boggs, D. L. The relationships among body weight, body composition, and intramuscular fat content in steers. J. Anim. Sci. 82, 1315–1322 (2004).

Garmyn, A. J. et al. Estimation of relationships between mineral concentration and fatty acid composition of longissimus muscle and beef palatability traits. J. Anim. Sci. 89, 2849–2858 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior-Brasil (CAPES) and to the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP; process: 2019/20164-4) for the scholarship provided to the first author, and for the financial support of this study (Grant number: 2019/24747-4). We are also thankful to the NUTRICORP (Araras, São Paulo, Brazil) for the financial support of this study. The authors also would like to acknowledge the support from São Paulo State University and the technical help provided by the co-workers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

(A) M. S.: Writing – original draft, review & editing, Investigation, Conceptualization; M. M. S.: Collected data and samples; L. D. F.: Collected data and samples; (B) L. D.: Collected data and samples; L. A. F. S.: Collected data and samples; D. M. C.: Collected data and samples; J. M. S.: Writing – review & editing; G. F. V. J.: Writing – review & editing; G. S.: Writing – review & editing; D. D. M.: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Silvestre, A.M., Squizatti, M.M., Felizari, L.D. et al. Nutritional protocols that shift ruminal microbiota to improve the feedlot performance of Nellore cattle differing in marbling EPD. Sci Rep 15, 41785 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25745-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25745-3