Abstract

Type 2 diabetes can be prevented by lifestyle intervention. We aimed to identify metabolites that associate with glucose metabolism and respond to lifestyle intervention with evidence-based targets for nutrition and physical activity in individuals at high risk of type 2 diabetes. Standard oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) was used to categorize 624 participants into those having normal glucose tolerance (NGT), isolated impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), IGT with increased fasting glucose (IGT + IFG), and type 2 diabetes. Plasma LC-MS metabolomics was performed to reveal metabolic signatures. The baseline group differences were analysed with the Kruskal–Wallis test and the effect of intervention with a linear mixed-effects model. Significant differences in the metabolite signature were observed between the baseline groups, particularly in amino acids, acylcarnitines, and phospholipids. Fatty acid amides, phospholipids, amino acids, dimethylguanidinovaleric acid, and 5-aminovaleric acid betaine responded most to the lifestyle intervention. Lysophosphatidylcholines containing odd-chain fatty acids showed associations with improved glucose metabolism. Twenty-five metabolites differed between the baseline groups, responded to the intervention, and were associated with changes in glucose metabolism. The findings suggest a metabolite panel could be used in distinguishing individuals with varying degrees of glucose metabolism and in predicting response to lifestyle interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes is a complex disorder that is associated with multiple metabolic abnormalities and can be prevented by lifestyle changes1. Many circulating metabolites have been shown to predict the risk of type 2 diabetes and be affected by lifestyle interventions2,3. Lifestyle interventions, which include dietary modification, increased physical activity, and weight loss, are central in type 2 diabetes prevention by improving insulin sensitivity and glycemic control. Landmark studies, such as the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) in the United States and the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS), have shown that lifestyle changes can reduce the risk of developing type 2 diabetes by nearly 60% in high-risk individuals4,5. Metabolomics offers an opportunity to improve the early identification of those at increased risk of type 2 diabetes and may help understand the pathways relevant to disease prevention in response to a healthy lifestyle.

The Human Metabolome Database currently lists 21 unique plasma metabolites associated with type 2 diabetes6. Because type 2 diabetes is a preventable disease, the past metabolomics efforts have mostly focused on studying the pathophysiological processes potentially leading to or associated with the disease, such as impaired fasting glucose (IFG) and impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), to allow an early detection before the onset of the disease itself7. Several metabolites, including different amino acids, lipids and sugar metabolites, have been recognized as markers of impaired glucose metabolism8. For example, increased circulating concentrations of branched-chain amino acids and aromatic amino acids have been consistently associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes, whereas increased circulating levels of glycine, indolepropionic acid and several phosphatidylcholines have been associated with a decreased risk of type 2 diabetes3,8,9. Some of these metabolites associated with increased type 2 diabetes risk have been shown to change in response to lifestyle interventions10. Research has also been conducted on the metabolic impact of intervention studies, where N-acetyl-d-galactosamine, glycine betaine, methionine sulfoxide, 7-methylguanine, propionylcarnitine, putrescine, and serine have been associated with disease regression11,12.

Randomized controlled efficacy trials have been the main approach at investigating the effects of lifestyle interventions on the risk of developing type 2 diabetes or its risk factors. However, the implementation of the models developed in these studies for the prevention of type 2 diabetes in real-world and primary health care settings has been challenging. To this aim, we performed the Stop Diabetes (StopDia) study and developed a model for the prevention of type 2 diabetes as part of the Finnish healthcare system13. We were able to demonstrate the beneficial effects of combined digital intervention and group counselling on diet quality, waist circumference and fasting plasma insulin in individuals at increased risk for type 2 diabetes14, although there were no improvements in the blood glucose and weight.

In this study, we aimed to identify a metabolite pattern both associated with markers of glucose metabolism and impacted by a lifestyle intervention to identify metabolic pathways metabolic pathways that could be potential targets in personalized treatment of type 2 diabetes. First, we explored whether fasting plasma non-targeted metabolomics analysis could identify metabolites that advance the detection of abnormal glucose metabolism in individuals known to be at increased risk for type 2 diabetes based on the Finnish Diabetes Risk Score (FINDRISC) questionnaire15 by dividing the cohort into four baseline groups – normal glucose tolerance (NGT), isolated impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), impaired glucose tolerance with increased fasting glucose (IGT + IFG), and type 2 diabetes – based on their glucose metabolism markers according to the American Diabetes Association (ADA) criteria for the diagnosis of diabetes16. Second, we aimed to determine plasma metabolites that respond to a lifestyle intervention in a real-world setting in order to assess potential individual responses that could affect the potential impact of such an intervention.

Methods

Study design and participants

The StopDia study is a one-year, parallel-group, unblinded, multiple-setting randomized controlled trial (RCT) (ClinicalTrials, NCT03156478; 17/05/2017), which was carried out in the primary health care system as part of the routine actions within three regions in Finland, including North Savo, South Karelia, and Päijät-Häme. The study protocol, clinical measurements, interventions and recruitment process of this RCT have been described in detail previously13,14,17. The StopDia study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of Northern Savo (statement number: 467/2016). Written informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all participants. All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

The participants were recruited using the Stop Diabetes Digital Screening Tool, which included a validated Finnish Diabetes Risk Score (FINDRISC)15. Several communication channels were used for recruitment that was implemented between March 2017 and February 201817. The inclusion criteria for the study were (1) age of 18–70 years; (2) 12 points or more in the FINDRISC or previous gestational diabetes or repeated impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance; (3) living in one of the three regions (North Savo, South Karelia, and Päijät-Häme); (4) possibility to use computer, smartphone or tablet with internet connection; (5) having a phone number of own; and (6) adequate Finnish language skill. Exclusion criteria were (1) type 1 or 2 diabetes (if type 2 diabetes was diagnosed during the study, a person was included in the baseline analyses of the present study); (2) pregnancy or breastfeeding; and (3) current cancer or less than 6 months from the end of cancer treatment.

Eligible individuals were invited to participate in the study and book an appointment with a study nurse at their local primary healthcare centre. At the first study visit, the participants signed a written informed consent form, and the nurse performed clinical measurements and referred the participants to laboratory measurements. After the first study visit, the participants received a personal link by email to the StopDia Digital Questionnaire and were instructed to complete the questionnaire within two weeks. Physical activity was assessed with questions of conditioning and everyday physical activity as well as physical activity during work trips. Adherence to a recommended diet and diet preventing type 2 diabetes were assessed using the Healthy Diet Index18. The participants who met the inclusion criteria, had filled out the StopDia Digital Questionnaire, had given blood samples in a local laboratory, and had no diabetes according to the results of the 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) were randomly assigned to a digital intervention group (DIGI), a combined digital and group-based face-to-face intervention group (DIGI + F2F), or a control group (CONTROL) with 1:1:1 allocation. The control group was not included in this metabolomics study. The participants for the metabolomics study (N = 624) were randomly chosen except for the following conditions: all participants classified into T2D group were chosen; the participant was excluded if the plasma sample or clinical data entry was missing from either baseline or 1-year time point.

The digital intervention involved the use of an application available for portable devices, which allowed for user-chosen behavioral suggestions (out of 489 total suggestions), and support for habit formation with prompts for daily self-monitoring and provision of summary feedback13. The behavioural suggestions were related to improving meal frequency, the intake of various food groups, physical activity, sedentary behaviour, sleep, mood, and non-smoking. The face-to-face activities contained group coaching complementing the digital habit formation strategies with motivational, problem solving, and peer support components. Adherence to the lifestyle intervention was monitored by the application.

In total, a subset of 624 individuals from the StopDia study population14 was included in the metabolomics analyses. Out of them, 455 individuals meeting the criteria for prediabetes, participating in the lifestyle intervention, had their 1-year samples analysed, whereas 169 individuals diagnosed with type 2 diabetes only had their baseline measurements taken. Supplemental Figure S1 shows the baseline subgroups and the intervention groups of the StopDia study that were included in these analyses. For the one-year intervention analysis, the participants were categorised into three groups according to the American Diabetes Association criteria for the diagnosis of diabetes 14: normal glucose tolerance (NGT; N = 153), isolated impaired glucose tolerance (IGT; N = 87), and impaired glucose tolerance with increased fasting glucose (IGT + IFG; N = 216)16. Because the primary outcome of the StopDia study only showed an effect when the two intervention groups were treated as one, in this metabolomics study we were especially interested in the plasma metabolites that were altered during the intervention in those individuals at increased type 2 diabetes risk. Therefore, we focused on the two intervention groups and performed metabolomics only on the baseline and one-year samples of the two groups.

LC-MS analysis

The plasma samples were prepared for the metabolomics analysis according to Klåvus et al.19. Briefly, cold acetonitrile was added in a ratio of 400 µL per 100 µL of plasma into filter plates (Captiva ND filter plate 0.2 μm) and mixed by pipetting. The samples were then centrifuged for 5 min at 700 × g at 4 °C and kept at 10 °C until analysis. The quality control (QC) samples were prepared by pooling aliquots from the experimental samples.

An ultra-high performance liquid chromatography (LC) system (Vanquish Flex UHPLC, Thermo Scientific, Bremen, Germany) was used for the analysis, which was coupled online to a high-resolution mass spectrometry (MS, Q Exactive Classic, Thermo Scientific). The samples were measured using two distinct chromatographic techniques: reversed phase (RP) and hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC). The analyses in RP include the utilization of both electrospray ionization (ESI) polarities, which were ESI positive (ESI+) and ESI negative (ESI−). Only ESI + data was collected in HILIC. The centroid mode was used to obtain a full scan data. The data was collected over a mass to charge ratio (m/z) range of 120 to 1200 in the RP technique and 75 to 750 in HILIC technique. To identify metabolites, we acquired data-dependent product ion spectra (MS/MS) from pooled quality control (QC) samples at the beginning and end of the analysis for each mode. In addition, QC samples were incorporated in the analysis at the beginning and subsequently after every 12 samples. The configuration and specifications for the LC-MS instrument have been previously published20.

Data analysis

The signal detection and alignment were performed in MS-DIAL version 4.4821 according to Klåvus et al.19. Briefly, the minimum peak height for the mass spectrometry data was set at 200 000 counts, and for the alignment, retention time tolerance was set at 0.6 min for HILIC data and 0.5 min for RP data. A sample-to-blank filter was used to remove the solvent background by requiring that the ratio of the maximum peak height in the samples and the average peak height in the solvent blank injections was more than 5. The gap filling by compulsion option was used to reduce missing values in the data by re-extracting signal intensities at expected m/z and retention time positions where a feature was detected in other samples. The data matrix containing the aligned peak areas across all samples was then pre-processed in notame R package19 to correct the drift in signal intensity across the QC samples and analytical batches and to filter out poor-quality molecular features. The number of molecular features after each data processing step is presented in Supplemental Table S1. The k-means clustering analysis was performed with Multiple Experiment Viewer 4.9.0.

Statistical analyses

The differential molecular features between the NGT, isolated IGT, IGT + IFG, and T2D groups at baseline were determined with the Kruskal–Wallis test. Multivariable linear mixed-effects models (LME) were applied to determine the contribution of each molecular feature on the changes in clinical outcome variables (Supplemental Table S2) during the intervention in DIGI and DIGI + F2F. The covariate p-value from the model signifies whether there was a statistically significant association between the molecular feature and the clinical outcome variable, whereas the time * group interaction p-value indicates how the intervention modified the association between the molecular features and the clinical outcomes. Both models were adjusted for age and sex and repeated-measures structure was taken into account with the mixed model using the participant as subject for random effects. Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate correction was performed on the p-values (reported as q-values) to account for the potential false positive results caused by multiple measurements. The principal component analysis (PCA) was generated with the prcomp function in R version 4.3.3., with variables centered and scaled to unit variance. Features with zero variance were excluded prior to analysis. The resulting PCA scores were visualized using the ggbiplot package and the density curves with the cowplot package. The PERMANOVA analysis was performed on the good-quality molecular features using vegan package in R.

Metabolite identification

The differential metabolites between the baseline groups and altered by the intervention were identified with MS-DIAL by comparing the observed MS/MS spectra with our in-house spectral database (level 1), publicly available spectral databases, such as MassBank, ReSpect, GNPS, RIKEN, and HMDB (level 2), and MS/MS spectra generated in silico in MS-FINDER 3.5022 (level 3). The level of the annotation reliability is based on the Metabolomics Standards Initiative (MSI) recommendations23.

Results

Differences among baseline groups

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the participants included in this metabolomics study. Of the 624 participants including those with type 2 diabetes, 72% were women, 29% were people with overweight (BMI 25–30), and 64% were people with obesity BMI > 30. The mean age (SD) was 57.5 (8.8) years and the mean BMI (SD) was 32.3 (5.5) kg/m2. At baseline, 153 participants (25%) were classified as having normal glucose tolerance (NGT), whereas 87 (14%) had isolated impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), 215 (34%) had impaired glucose tolerance with increased fasting glucose (IGT + IFG), and 169 (27%) had type 2 diabetes.

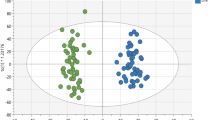

First, we studied the differences in the metabolic profiles among the four baseline groups with variable glucose metabolism (NGT, isolated IGT, IGT + IFG, and T2D). The differences in the overall molecular features were visible already in the principal component analysis (PCA) (Supplemental Figure S2), where a gradual shift from the NGT group to T2D group via the IGT and IGT + IFG groups can be observed from the 95% confidence intervals; however, these differences in the molecular features representing the whole metabolome were not statistically significant in the PERMANOVA analysis (p = 0.085). When the metabolic profiles of those individuals that underwent the DIGI or DIGI + F2F intervention were compared between the baseline and one-year time points, a negligible difference was observed based on the confidence intervals and the density plots (Supplemental Figure S2).

We then identified metabolites that were different among the baseline groups. Out of the 149 metabolites identified in this study, 113 were statistically significantly different (q < 0.05) across the NGT, isolated IGT, IGT + IFG, and T2D groups at baseline (Supplemental Table S3). Many of these metabolites exhibit associations among the baseline groups ranging from participants with normal glucose metabolism to those with type 2 diabetes, the metabolites having gradually higher or lower levels in groups with a metabolic status closer to type 2 diabetes (Fig. 1). Differential metabolites with lower levels in the T2D group compared to NGT include lysophosphatidylcholines (LPCs) with odd-chain fatty acid chains (e.g., LPC 17:0 and LPC 19:0), plasmalogens (e.g., LPC P-16:0), alkyl ether phosphatidylcholines (e.g., LPC O-18:1), glycerophosphocholine (GPC), alpha-tocopherol, glutamine, trigonelline, hippuric acid, pyrocatechol sulfate, and fatty acid amides (stearamide and palmitamide) (Supplemental Table S3). We detected four isomers of LPC 17:0, all behaving similarly across the four baseline groups; the isomers were determined using our in-house database of reference standards to differentiate based on the location and chain type (straight or branched-chain) of the fatty acid moiety (Supplemental Figure S3). Metabolites with higher levels in the T2D group compared to the NGT group include amino acids and their derivatives (e.g., glutamic acid, isoleucine, leucine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, and valine), polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs; e.g., FA 24:6 and FA 22:4), dimethylguanidinovaleric acid (DMGV), phosphatidylcholines, acylcarnitines (short-, medium- and long-chain), and ursodeoxycholic acid. Figure 1 shows the levels of metabolites representing different metabolite classes that had differences between the baseline groups.

Levels of selected metabolites, representing various metabolite classes, in the baseline groups at baseline. Wilcoxon tests were performed between the group pairs; ns: not significant; *: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.01; ***: p < 0.001; ****: p < 0.0001. Metabolite abbreviations: DMGV: dimethylguanidinovaleric acid; LPC: lysophosphatidylcholine; P: plasmalogen; FA: fatty acid; AA: arachidonic acid; CAR: acylcarnitine. NGT: normal glucose tolerance, IGT: isolated impaired glucose tolerance, IGT + IFG: impaired glucose tolerance with increased fasting glucose, T2D: type 2 diabetes.

Metabolic response to the intervention

Because StopDia was a trial on type 2 diabetes risk factors, our main interest was on the metabolites that in addition to their associations with baseline glucose metabolism could be modified by a lifestyle intervention. We performed multivariable linear mixed-effects models (LME) to study the impact of the intervention on the metabolite levels. Since the two intervention groups (digital application with and without face-to-face group counselling) performed very similarly regarding the change in clinical markers14, they were treated as one intervention group in these analyses. We annotated 55 metabolites that were differential between baseline and one-year timepoint (Fig. 2; Table 2). The 21 metabolites that increased during the intervention belong to three main metabolite classes: amino acids and derivatives, phospholipids, and fatty acid amides. The amino acid derivatives include DMGV, two N-methylated lysines, indoxyl sulfate, and 5-aminovaleric acid betaine (5-AVAB). The phospholipids include GPC and three lysophosphatidylcholines, whereas the nine fatty acid amides include oleamide, oleoyl ethylamide, and palmitamide.

We annotated 34 metabolites that decreased during the intervention. Apart from one fatty acid amide and one amino acid, these metabolites belong to other metabolite classes than those that increased during the intervention: free fatty acids, acylcarnitines, and steroids. In fatty acids, we found decreases mostly in PUFAs, such as FA 18:2 (linoleic acid), FA 20:4 (arachidonic acid), FA 22:4 (adrenic acid) and FA 22:6 (DHA). Acylcarnitines that decreased were mostly medium- and long-chain acylcarnitines, such as C12, C14 and C16. Among the decreased steroids in our study were dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), testosterone sulfate, and androsterone sulfate. Out of the metabolites affected by the intervention, the levels of 40 metabolites were also different between the baseline groups at baseline (Fig. 2); out of these, acetylcarnitine, beta-leucine, CAR 12:0;O, DMGV, GPC, FA 22:6 (DHA), stearamide, and two unknown molecular features with formulas C8H12N2O5 and C7H16N2O were among the most significant annotated metabolites in both the Kruskal–Wallis test between baseline groups and the LME on the intervention effect.

Heatmaps of the metabolites that increased (A) or decreased (B) during the intervention and their associations with clinical biomarkers. The Cohen’s d values are calculated for the difference between baseline and 1-year timepoint (all groups that underwent the intervention; a positive value indicates an increase during the intervention) and for the difference between the NGT and T2D groups at baseline, where a positive value indicates a higher metabolite level in the T2D group. The associations between the metabolites and the clinical biomarkers are represented as normalized standard scores of the covariates from the linear mixed model: a positive value indicates that the metabolite and the clinical biomarker changed in the same direction during the intervention. A cut-off value − 2…+2 was applied to all the values for the colour scale, and the metabolites were arranged based on their chemical class and hierarchical clustering.

Associations with clinical markers

Finally, we explored whether the identified metabolites, both associating with baseline glucose metabolism and responsive to the lifestyle intervention, differed in their correlations with the change in weight, waist circumference, glucose or insulin metabolism, the Healthy Diet Index (HDI), and physical activity. These results are summarized in Fig. 2. Out of the 40 metabolites that were different between baseline groups and were altered by the intervention, 25 also were associated (q < 0.05) with the change in 120-min glucose (Fig. 3). Of the metabolites that increased during the intervention, DMGV positively correlated with weight, waist circumference, and fasting glucose, whereas LPC 19:0, a lysophosphatidylcholine containing an odd-chain fatty acid, correlated negatively with weight, waist circumference, and fasting glucose and positively with physical activity and HDI. We did not observe a significant impact of the intervention on LPC 17:0. Of the metabolites that decreased during the intervention, several fatty acids and all acylcarnitines correlated positively with the 120-min glucose, and the steroids tended to correlate negatively with physical activity and HDI.

DMGV exhibited an unexpected behaviour during the intervention: it increased in response to the intervention and positively correlated with weight change even though weight did not change significantly during the intervention. Therefore, to investigate the potential differences in individual responses to the intervention, we divided the individuals based on the increase/decrease of DMGV levels and plotted them based on weight change (Supplemental Figure S4). Compared to LPC 19:0, which responded to the intervention as expected, individuals with increased DMGV levels had a high number of those whose weight decreased but also several cases with a high weight increase. We further analyzed the two metabolites and two endpoint markers (weight and 120-min glucose, which correlated with the metabolites) in more detail using k-means clustering. This resulted in a heatmap showing several subgroups of individuals with unique responses in the metabolite levels and endpoint markers unrelated to the baseline group (Supplemental Figure S5).

Venn diagram showing the numbers of annotated metabolites that differed across the four groups of glucose metabolism at baseline, that were changed during the one-year intervention period, and/or whose one-year changes correlated with a one-year change in 120-min glucose. Box plots show the baseline and one-year plasma levels of selected metabolites that were statistically significant in all these three statistical analyses in the four groups of glucose metabolism at baseline. Box plots of all the 55 metabolites impacted by the intervention are presented in Supplemental Figure S6. NGT: normal glucose tolerance, IGT: isolated impaired glucose tolerance, IGT + IFG: impaired glucose tolerance with increased fasting glucose, T2D: type 2 diabetes.

Discussion

This study showed that a metabolite signature that differs according to glucose metabolism can be used to advance the detection of abnormal glucose metabolism in individuals considered to be at increased risk for type 2 diabetes in a primary care setting even before traditional markers show adverse changes. Second, we found that some of these metabolites respond to a lifestyle intervention in a real-world setting that could be used in stratifying subgroups (“metabotypes”) that benefit from the intervention, as demonstrated by the individual responses of certain metabolites on the intervention, such as DMGV. Some of these metabolites are known to be related to the risk of type 2 diabetes, such as fatty acids, acylcarnitines, and lysophosphatidylcholines, whereas others are novel candidates to be explored further, such as fatty acid amides. On the other hand, several metabolites previously associated with the risk of type 2 diabetes, such as BCAAs and branched-chain fatty acids (BCFAs), did not respond to the intervention in an expected way. This suggests that either the amino acid metabolic pathways related to type 2 diabetes development were not affected by the lifestyle intervention or the effect was hindered by individual variation in the responses, as shown for DMGV.

Our first main finding was that certain BCAAs, aromatic amino acids, acylcarnitines, GPC, lysophosphatidylcholines containing odd-chain fatty acids and DMGV differed across the groups of glucose metabolism at baseline. Our results agree with the results of previous studies which have shown the associations of BCAAs (such as isoleucine and leucine), aromatic amino acids (such as tyrosine and phenylalanine), and short-chain acylcarnitines (such as C2, C3 and C6), with increased risk of type 2 diabetes3,8. GPC is an intermediate of glycerophospholipid metabolism whose metabolite linoleoylglycerophosphocholine (LGPC) has been found to be associated with decreased risk of type 2 diabetes24. It is also an osmolyte; lower plasma GPC levels in the T2D group can be a sign of disturbed cellular osmoregulation caused by high extracellular glucose levels, and the increase in plasma GPC levels during the intervention may indicate an improvement in the body fluid balance and osmolality25,26. Furthermore, several phospholipid species containing odd-chain fatty acids 15:0, 15:1, 17:0 and 19:0 have been inversely associated with the development of type 2 diabetes in previous studies9,27. It remains unclear how lipids containing odd-chain fatty acids are involved in the pathways of type 2 diabetes development. One hypothesis is that odd-chain fatty acids could improve mitochondrial function by providing intermediates for the tricarboxylic acid cycle28.

It is important to note that most of the metabolites that are associated with abnormal glucose metabolism are potentially regulated by lifestyle. We found the most significant increases in response to the lifestyle intervention in fatty acid amides, phospholipids, and amino acids and their derivatives. Fatty acid amides are a group of lipids that have been increasingly studied in recent years for their physiological and pharmacological effects, including regulation of the sleep/wake cycle and cell signalling via multiple receptors, such as the cannabinoid receptors29,30, which in turn are involved in the development of diabetes31. Recently, several fatty acid amides were identified as mediators of better exercise performance within the gut–brain axis, promoting dopamine levels in brain areas related to reward and pleasure processing32. Among phospholipids, GPC, LPC 19:0, and LPC 20:1 were found to increase most significantly and they were also associated with better glucose metabolism, which is parallel with the findings from the Australian prospective study on the risk and prevalence of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease33 and another Finnish study on the prevention of type 2 diabetes9. Interestingly, LPC 19:0 and 20:1 were also positively associated with the HDI18 as well as leisure time and time spent on physical exercise. Eicosenoic acid (FA 20:1) is a monounsaturated fatty acid found in several vegetable oils34, which could explain its association with HDI. Furthermore, habitual physical activity could induce adipose tissue lipolysis which increases the levels of circulating free fatty acids. Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity has been positively associated with eicosenoic acid in plasma phospholipids in pregnant women35. Furthermore, eicosenoic acid is part of a fatty acid signature associated with decreased risk of type 2 diabetes36 and lysophosphatidylethanolamine (20:1) has been observed to decrease during gestational diabetes and be associated with 120-min glucose37; thus, the increase in LPC 20:1 observed in this study, linked to the metabolism of eicosenoic acid, could refer to improved glucose metabolism.

Among individual metabolites that increased after the intervention were 5-AVAB, DMGV, proline, and ornithine. 5-AVAB, which belongs to amino acid-derived quaternary ammonium compounds, has been suggested to have protective effects on heart function and type 2 diabetes38,39. Plasma DMGV differed across the groups of glucose metabolism, with the T2D group having the highest levels. DMGV has been identified as a predictive marker of type 2 diabetes up to 12 years before its onset40 and associated with increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease in the future41. Proline has been linked with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes as well42. The unexpected increase in DMGV and proline levels during the intervention may point towards individual factors in response to the intervention, as evidenced by subgroups with varying responses to the levels of DMGV and associated endpoint markers. This suggests that there are metabotypes associated with the efficiency of the intervention (Supplemental Figure S4 and S5). Ornithine is an amino acid in the urea cycle that is metabolized by ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) into putrescine. Early diabetes exhibits kidney growth and a higher glomerular filtration rate (GFR), which is linked to increased ODC activity43. We suggest that the increased ornithine levels observed in this intervention study could be a sign of lowered ODC activity and reduced hyperfiltration related to the onset of type 2 diabetes; however, more studies involving GFR measurements are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Among the metabolites that decreased after the lifestyle intervention most significantly were free fatty acids (mostly PUFAs), acylcarnitines, and steroids. The effects of PUFAs, especially arachidonic acid and DHA, in eicosanoid production and inflammation have been extensively studied; however, both have also been associated with increased insulin sensitivity44, and therefore their decrease in this study may point out towards individual responses to the intervention. The decrease in acylcarnitines was associated with a decrease in 120-min glucose. The accumulation of long-chain acylcarnitines has been suggested to reflect incomplete fatty acid oxidation, and especially increased concentrations of acylcarnitines C10–C14 have been found in individuals with type 2 diabetes45. A decrease in the long-chain acylcarnitines in this study could indicate improved mitochondrial function and lipid metabolism as a result of the intervention. Many of the decreased steroids in our study were their sulfated form and also inversely associated with physical activity. Higher serum DHEAS levels have been associated with decreased risk of type 2 diabetes in older men but not in women46. Our results are in line with the previous findings which have shown that physical activity decreases free testosterone, androstenedione and DHEAS levels in women47. These findings could be explained by the conversion of sulfated steroids into their active forms in target tissues48.

This study has several strengths. The intervention has been carried out in a real-world primary care setting, which offers a novel approach to investigate metabolomic associations occurring without controlled experiments. The study setting also allows for combining associations with baseline glucose metabolism with the response to lifestyle intervention. The large number of studied samples combined with extensive characterization of the untargeted metabolomics data enabled us to determine several metabolites that differed statistically between all the baseline groups, some of which have not been described earlier. The study also has limitations in the study setting and analytical methodology. Due to our main study question, we did not perform metabolomics on the control group samples, which prevented us from verifying the intervention effect in a controlled setting. The study was conducted in a Finnish population, known to be genetically homogenous and relatively distant from other European ethnicities, which limits the generalizability of the results to other populations. Some of the interesting molecular features could not be identified because of the limited availability of reference spectra, an inherent issue in non-targeted metabolomics.

In this study, we report a panel of metabolites that differentiated four groups of individuals with varying glucose metabolism. These metabolites, which include both known markers of type 2 diabetes and novel candidates, could be utilised as a biomarker pattern to predict the stage of type 2 diabetes onset earlier than what is possible with traditional glucose tolerance tests. Identifying the status of glucose metabolism from a single blood sample with a sensitive method, such as LC-MS metabolomics, could allow for a cost-effective and individual treatment plan, and similar approaches have already been implemented commercially49. A significant portion of the metabolites reported in this study, including amino acids, phospholipids, fatty acid amides, free fatty acids, acylcarnitines, and steroids, responded to the lifestyle intervention in a real-world type 2 diabetes prevention program. They suggest various metabolic changes during the intervention, such as reduced production of inflammation markers, improved lipid metabolism via mithocondrial β-oxidation, and increased steroid sulfatase activity. Further research on the novel candidate markers, such as fatty acid amides, is warranted. Several key amino acid markers of active type 2 diabetes did not respond to the intervention, suggesting that individual means for type 2 diabetes prevention may be necessary and that single metabolite markers may not be specific enough to reflect the preventive effects. Our findings suggest that the metabolites reported in this study indicate the most responsive metabolic pathways to be targeted by personalized lifestyle interventions to mitigate the risk of type 2 diabetes.

Data availability

The dataset generated during and analyzed in the current study is available in the B2SHARE repository (https://doi.org/10.23728/b2share.04de8e6f764a49baaca536d1ede1d3ae).

Abbreviations

- 5-AVAB:

-

5-Aminovaleric acid betaine

- BCAA:

-

Branched-chain amino acid

- BCFA:

-

Branched-chain fatty acid

- DHA:

-

Docosahexaenoic acid

- DHEAS:

-

Dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate

- DMGV:

-

Dimethylguanidinovaleric acid

- FINDRISC:

-

Finnish diabetes risk score

- GFR:

-

Glomerular filtration rate

- GPC:

-

Glycerophosphocholine

- HDI:

-

Healthy diet index

- IFG:

-

Increased fasting glucose

- IGT:

-

Isolated impaired glucose tolerance

- LGPC:

-

Linoleylglycerophosphocholine

- LME:

-

Linear mixed-effects models

- LPC:

-

Lysophosphatidylcholine

- MASH:

-

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis

- MASLD:

-

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease

- MSI:

-

Metabolomics Standards Initiative

- NGT:

-

Normal glucose tolerance

- ODC:

-

Ornithine decarboxylase

- OGTT:

-

2-hour oral glucose tolerance test

- PUFA:

-

polyunsaturated fatty acid

- QC:

-

Quality control

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

References

Ahmad, E., Lim, S., Lamptey, R., Webb, D. R. & Davies, M. J. Type 2 diabetes. Lancet 400, 1803–1820 (2022).

Li, J. et al. The mediterranean diet, plasma metabolome, and cardiovascular disease risk. Eur. Heart J. 41, 2645–2656 (2020).

Morze, J. et al. Metabolomics and type 2 diabetes risk: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Diabetes Care. 45, 1013–1024 (2022).

Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or Metformin. N. Engl. J. Med. 346, 393–403 (2002).

Tuomilehto, J. et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N. Engl. J. Med. 344, 1343–1350 (2001).

Wishart, D. S. et al. HMDB 5.0: the human metabolome database for 2022. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D622–D631 (2022).

Pallares-Méndez, R., Aguilar-Salinas, C. A. & Cruz-Bautista, I. Del Bosque-Plata, L. Metabolomics in diabetes, a review. Ann. Med. 48, 89–102 (2016).

Guasch-Ferré, M. et al. Metabolomics in prediabetes and diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 39, 833–846 (2016).

de Mello, V. D. et al. Indolepropionic acid and novel lipid metabolites are associated with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes in the Finnish diabetes prevention study. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–12 (2017).

Kivelä, J., Meinilä, J., Uusitupa, M., Tuomilehto, J. & Lindström, J. Longitudinal Branched-Chain amino Acids, lifestyle Intervention, and type 2 diabetes in the Finnish diabetes prevention study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabolism. 107, 2844–2853 (2022).

del Sevilla-Gonzalez, R. M. et al. Metabolomic markers of glucose regulation after a lifestyle intervention in prediabetes. BMJ Open. Diabetes Res. & Care 10 (2022).

Walford, G. A. et al. Metabolite profiles of diabetes incidence and intervention response in the diabetes prevention program. Diabetes 65, 1424–1433 (2016).

Pihlajamäki, J. et al. Digitally supported program for type 2 diabetes risk identification and risk reduction in real-world setting: protocol for the StopDia model and randomized controlled trial. BMC public. Health. 19, 1–13 (2019).

Lakka, T. A. et al. Real-world effectiveness of digital and group-based lifestyle interventions as compared with usual care to reduce type 2 diabetes risk–A stop diabetes pragmatic randomised trial. The Lancet Reg. Health–Europe 24 (2023).

Makrilakis, K. et al. Validation of the Finnish diabetes risk score (FINDRISC) questionnaire for screening for undiagnosed type 2 diabetes, dysglycaemia and the metabolic syndrome in Greece. Diabetes Metab. 37, 144–151 (2011).

Association, A. D. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 33, S62–S69 (2010).

Jalkanen, K. et al. Comparison of communication channels for large-scale type 2 diabetes risk screening and intervention recruitment: empirical study. JMIR Diabetes. 6, e21356 (2021).

Lindström, J. et al. Formation and validation of the healthy diet index (HDI) for evaluation of diet quality in healthcare. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18, 2362 (2021).

Klåvus, A. et al. Notame: workflow for Non-Targeted LC–MS metabolic profiling. Metabolites 10, 135 (2020).

Lapatto, H. A. et al. Nicotinamide riboside improves muscle mitochondrial biogenesis, satellite cell differentiation, and gut microbiota in a twin study. Sci. Adv. 9, eadd5163 (2023).

Tsugawa, H. et al. MS-DIAL: data-independent MS/MS Deconvolution for comprehensive metabolome analysis. Nat. Methods. 12, 523–526 (2015).

Tsugawa, H. et al. Hydrogen rearrangement rules: computational MS/MS fragmentation and structure Elucidation using MS-FINDER software. Anal. Chem. 88, 7946–7958 (2016).

Sumner, L. W. et al. Proposed minimum reporting standards for chemical analysis. Metabolomics 3, 211–221 (2007).

Vangipurapu, J., Fernandes Silva, L., Kuulasmaa, T., Smith, U. & Laakso, M. Microbiota-related metabolites and the risk of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 43, 1319–1325 (2020).

Feldman, E. L., Russell, J. W., Sullivan, K. A. & Golovoy, D. New insights into the pathogenesis of diabetic neuropathy. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 12, 553–563 (1999).

Baumgartner, C. et al. Potential role of skeletal muscle Glycerophosphocholine in response to altered fluid balance in humans: an in vivo nuclear magnetic resonance study. Am. J. Physiology-Endocrinology Metabolism. 324, E339–E346 (2023).

Prada, M. et al. Association of the odd-chain fatty acid content in lipid groups with type 2 diabetes risk: A targeted analysis of lipidomics data in the EPIC-Potsdam cohort. Clin. Nutr. 40, 4988–4999 (2021).

Pfeuffer, M. & Jaudszus, A. Pentadecanoic and heptadecanoic acids: multifaceted odd-chain fatty acids. Adv. Nutr. 7, 730–734 (2016).

Farrell, E. K. & Merkler, D. J. Biosynthesis, degradation and Pharmacological importance of the fatty acid amides. Drug Discovery Today. 13, 558–568 (2008).

Lambert, D. M. & Di Marzo, V. The palmitoylethanolamide and oleamide enigmas: are these two fatty acid amides cannabimimetic? Curr. Med. Chem. 6, 757–773 (1999).

Gruden, G., Barutta, F., Kunos, G. & Pacher, P. Role of the endocannabinoid system in diabetes and diabetic complications. Br. J. Pharmacol. 173, 1116–1127 (2016).

Dohnalová, L. et al. A microbiome-dependent gut–brain pathway regulates motivation for exercise. Nature, 1–9 (2022).

Huynh, K. et al. High-throughput plasma lipidomics: detailed mapping of the associations with cardiometabolic risk factors. Cell. Chem. Biology. 26, 71–84 (2019).

Orsavova, J., Misurcova, L., Ambrozova, V., Vicha, J., Mlcek, J. & R. & Fatty acids composition of vegetable oils and its contribution to dietary energy intake and dependence of cardiovascular mortality on dietary intake of fatty acids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 12871–12890 (2015).

Xia, T. et al. A longitudinal study on associations of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity with plasma monounsaturated fatty acids in pregnancy. Front. Nutr. 9, 983418 (2022).

Zhu, X. et al. Association between fatty acids and the risk of impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes mellitus in American adults: NHANES 2005 – 2016. Nutr. Diabetes. 13, 8 (2023).

Dudzik, D. et al. Metabolic fingerprint of gestational diabetes mellitus. J. Proteom. 103, 57–71 (2014).

Haikonen, R., Kärkkäinen, O., Koistinen, V. & Hanhineva, K. Diet-and microbiota-related metabolite, 5-aminovaleric acid betaine (5-AVAB), in health and disease. Trends Endocrinol. & Metabolism (2022).

Kärkkäinen, O. et al. Whole grain intake associated molecule 5-aminovaleric acid betaine decreases β-oxidation of fatty acids in mouse cardiomyocytes. Sci. Rep. 8, 13036 (2018).

O’Sullivan, J. F. et al. Dimethylguanidino valeric acid is a marker of liver fat and predicts diabetes. J. Clin. Investig. 127, 4394–4402 (2017).

Ottosson, F. et al. Dimethylguanidino valerate: a lifestyle-related metabolite associated with future coronary artery disease and cardiovascular mortality. J. Am. Heart Association. 8, e012846 (2019).

Chen, Y. et al. Associations between serum amino acids and incident type 2 diabetes in Chinese rural adults. Nutr. Metabolism Cardiovasc. Dis. 31, 2416–2425 (2021).

Thomson, S. C. et al. Ornithine decarboxylase, kidney size, and the tubular hypothesis of glomerular hyperfiltration in experimental diabetes. J. Clin. Investig. 107, 217–224 (2001).

Lankinen, M. A. et al. Plasma fatty acids as predictors of glycaemia and type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 58, 2533–2544 (2015).

Adams, S. H. et al. Plasma acylcarnitine profiles suggest incomplete long-chain fatty acid β-oxidation and altered Tricarboxylic acid cycle activity in type 2 diabetic African-American women. J. Nutr. 139, 1073–1081 (2009).

Veronese, N. et al. Serum dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate and risk for type 2 diabetes in older men and women: the Pro. VA study. Can. J. Diabetes. 40, 158–163 (2016).

Ennour-Idrissi, K., Maunsell, E. & Diorio, C. Effect of physical activity on sex hormones in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Breast Cancer Res. 17, 1–11 (2015).

Sánchez-Guijo, A. et al. Role of steroid sulfatase in steroid homeostasis and characterization of the sulfated steroid pathway: evidence from steroid sulfatase deficiency. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 437, 142–153 (2016).

Buergel, T. et al. Metabolomic profiles predict individual multidisease outcomes. Nat. Med. 28, 2309–2320 (2022).

Acknowledgements

Mrs. Miia Reponen (School of Pharmacy, University of Eastern Finland) is acknowledged for technical assistance. We appreciate Biocentre Finland and Biocentre Kuopio for supporting LC-MS laboratory facility. We acknowledge the health and social care workers in the three participating regions (Hospital districts of North Savo, Päijät-Häme and South Karelia) and the stakeholders of the StopDia project (Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Finnish Social Security Institute Kela, Regional councils of North Savo and Päijät-Häme, Cities of Kuopio, Varkaus, and Siilinjärvi, Ylä-Savon SOTE, Finnish Heart Association, Finnish Diabetes Association, Family Federation of Finland, Association of Finnish Pharmacies, Consumers’ Union of Finland, Etera Mutual Pension Insurance Company, Agency for Rural Affairs Mavi and its partner organisations, Self-care and Digital Value Services project ODA) for participating in planning the recruitment of the participants and the intervention. We acknowledge Juho Viitasalo and Juha Kekäläinen from the University of Eastern Finland for their extensive work in the development of the StopDia digital tools. We also acknowledge Tiina Laatikainen, Kennet Harald, Markku Peltonen, Pekka Jousilahti, Katri Hemiö, Maliheh Nekouei, Marvi Langari, Eeva Virtanen, and Riia Järvenpää from the National Institute for Health and Welfare; Saara Vanhatalo, Johanna Leväsluoto, Adil Umer, Juha Leppänen, Samuli Heinonen, and Eeva Rantala from the Technical Research Centre of Finland VTT; Kari Jalkanen and Matti Uusitupa from the University of Eastern Finland; and Jaakko Tuomilehto from the University of Helsinki for their role in the development of the StopDia protocols and for participating in the project. We also thank the international advisory board of the StopDia project, including professors Edith Feskens, Theresa Marteau, and Peter Schwarz. The LC-MS analysis was supported by Biocenter Finland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.K. and S.Ma. drafted the manuscript. V.K. and M.T. performed the metabolomics data analysis. K.A., T.T.T., R.M., N.L., L.K., and M.K. were involved in performing the RCT experiment. K.A., E.J.R., T.T.T., and R.M. were responsible for data management. S.Mi. performed the statistical analysis. M.L. designed and performed the LC-MS analysis. L.K., J.M., K.P., U.S., P.A., and J.L. designed the RCT experiment. T.L., K.H., and J.P. designed the study setting. J.P. is the PI of the StopDia project. All authors critically revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

V.K. and K.H. are associated with Afekta Technologies Ltd. J.M. is a founding partner of ESiOR Oy. These companies were not involved in carrying out this research. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Koistinen, V.M., Manninen, S., Tuomainen, M. et al. Metabolites associated with abnormal glucose metabolism responding to primary care lifestyle intervention. Sci Rep 15, 39093 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25749-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25749-z