Abstract

The use of patient-reported outcomes measures (PROMs) is an application of the volume-to-value-based healthcare services, and was quantitatively used in the field of neurosurgery. Therefore, the current study aimed to investigate the preoperative and early postoperative, as well as changes and factors of changes, in specific PROMs among spinal neurosurgery patients in a tertiary hospital in Palestine. The study was conducted using a prospective longitudinal design on a convenience sample of 99 lumbar and 35 cervical spine neurosurgery patients, who were interviewed to fill in a preoperative and one-month postoperative questionnaire that measures pain, quality of life (QoL), sleep quality, and mental health PROMs. Valid versions of Arabic translated tools were used, including Neck Disability Index (NDI), Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), EuroQoL (EQ-5D-5 L), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). Data were analyzed using SPSS with full commitment to ethical considerations of anonymity and confidentiality. The patients had a mean age of 49.16 years, and were 50.7% females, 74.6% married, 59.7% underwent discectomy, a mean diagnosis-to-operation period of 7.15 weeks, and used preoperative paracetamol (69.4%), cortisones (76.9%), and NSAIDs (59.7%). All PROMs showed significant early postoperative improvements (p-value < 0.001), where better NDI improvements are found among urban residents and congenital disease-related operations, better ODI improvement among tumor resection patients, without hormonal disorders or use of preoperative cortisones, while better EQ-VAS improvements found among patients who are younger, and did not use preoperative paracetamol or muscle relaxants, and better ESS improvement are shown among older patients (p-value < 0.05). The current study found an overall significant early postoperative improvement among spinal neurosurgery patients in PROMs of pain, QoL, sleep quality, and mental health. Several studies agree with the findings of the current study, with differences in the affecting factors related to sampling and population characteristics differences. Patient’s engagement in preoperative education, resource allocation, and conduct of multicenter, interventional studies is recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) has established the term known as patient-reported outcomes (PROs) as a product of the transition from volume-based to value-based healthcare services, in which a Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System has been initiated. In such a system, the focus is on collecting crucial health information related to the patient’s history, assessment and postoperative phase that will help in enhancing the patient outcomes during and after hospitalization, which include, but are not limited to, comorbidities, mental health, social support, pre- and post-injury function, pain and quality of life (QoL)1, which helps in exploring strategies that may enhance the value of care that is provided to patients by improving health outcomes and reducing the cost of delivered care, which is done by developing valid and accurate measurements of the patients’ mental, physical and social health2.

Patient-reported outcomes measures (PROMs) consist of valid tools that intend to gather subjective information related to the patient’s condition during several phases of the surgical process, to build a comprehensive care plan and future short-term and long-term goals to improve surgical outcomes, with an increase in their use among neurosurgery patients3. Despite the abundance of tools that measure PROMs, studies have shown that there is an urgent need to develop disease-specific PROMs in the field of neurosurgery to address the satisfaction, safety, and different QoL and postoperative perspectives of the patients as the main specific outcomes related to neurosurgical procedures4,5,6. Several studies have shown that reporting PROs among spinal neurosurgery patients has demonstrated significant functional and psychological improvements, with decreased related disabilities7, while other studies have also focused on the cost-effectiveness and safety measures improvement in the hospital settings associated with such implementations8.

A systematic review has found that there are 31 unique PROs to assess at least one domain among neurosurgery patients, where 73% of the studies have focused on tools related to specific physical function disability, 55% on pain, and 32% on QoL. It is worth noting that few studies (5.7%) in the neurosurgery field utilize neurosurgery-specific PROMs9. In the neurospine surgical field, the most commonly used PROMs were the Scoliosis Research Society-22 (SRS-22), Short Form-12, Short Form-36 (SF-12 and SF-36), Ronald-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI). Recently, there has been a trend toward using disease-specific rather than generic tools, along with strong encouragement for using translated versions of validated tools across different settings and populations10.

Implementing PROMs effectively in healthcare services involves systematically integrating them into the hospital, outpatient clinic, or other healthcare institution. This process begins with defining the purpose, then moves to designing, preparing, and starting with a trial phase. It concludes with reflection, evaluation of the PROMs process, and making improvements9. Successful implementation of PROMs within health institutions requires ongoing and systematic identification of barriers, such as data collection burdens, healthcare providers’ skepticism about PROMs’ validity, and addressing concerns and issues related to their integration within specific healthcare service types10,11.

Also, the use of PROMs faces methodological issues, which are related to differences in data collection methods, as well as the nature of explanatory variables, which originate from differences between patient-reported and administrative data9. Other issues are concerned with the financial perspective, which are included in the need for support by experts, shared vision among healthcare specialists, patients and purchasers of healthcare services, targeting the sustainable implementation and improvement of healthcare quality10, in addition to financial issues across countries, like differences between low- and high-income courtiers, in the aspects of technological support, robust workflow and socioeconomic factors11.

The use of a longitudinal approach in PROMs for several surgical procedures was found to have an effective assessment of postoperative symptom recovery trajectories, resulting in more reflection of the effectiveness in recovery evaluation over time12,13. Also, the use of longitudinal methods of PROMs assessment was found to be beneficial in predicting the short- and long-term postoperative outcomes of surgeries, including pain and functional disability, using pre-surgical prediction algorithms, with the necessity to combine such longitudinal data with clinical factors to better understand patient outcomes14,15.

Studies have shown that the assessment and documentation of PROs among neurosurgery patients is both “under-utilized” and “under-standardized”3, which is manifested by the few number of neurosurgery-specific PROMs tools16 and the lack of robust evidence, yet high potential, of their use17. Moreover, the area of PROs among spinal neurosurgery patients in Palestine is under-covered in the scientific literature, which may be related to financial and staff-related issues18. Specific barriers related to this issue may include cultural beliefs and health perceptions of the Palestinian community19, language and communication barriers between patients and healthcare providers (HCPs) who mostly use medical jargon20, as well as the lack of validation of Arabic PROMs tools in the Palestinian context, in addition to the influence of healthcare expectations, social and family dynamics and trust in HCPs21.

The results of the current study will guide HCPs and decision-makers towards several interventions that aim to improve spinal neurosurgery patients’ physical and mental health outcomes, in term of increasing physicians and nurses’ awareness about the importance of covering the areas related to PROs among spinal neurosurgery patients, while decision-makers will be able to establish targeted guidelines related to interventions on enhancing the physical and mental health among them.

Methods

Study aim, design, and setting

The study aimed to investigate PROMs related to pain, QoL, sleep quality, and mental status, as well as the most common demographic and medical factors that are related to their pre-post changes, following spinal neurosurgery in Palestine, using a prospective, longitudinal, quantitative design, where the researcher collected data related to spinal neurosurgery patients’ PROMs before and one month after the surgical intervention, without the manipulation of the intervention itself. The used design allowed for the observation of the targeted variables (PROMs) in a temporal way22, to increase the statistical power related to the precision of estimated measures23, , and reduce recall bias24.

The study was conducted in the neurosurgery department of Palestine Medical Complex (PMC), a tertiary hospital that serves as the largest public referral hospital in Palestine, which serves a diverse patient population from various demographics, which improves the generalizability of the results.

Study population, sample, and sampling

The population of the study included all spinal neurosurgery patients who were planned to have cervical or lumbar neurosurgery operations for the removal of discopathies or tumors, who were admitted and scheduled for operations during the study period. The researcher implemented the convenience sampling technique, where all eligible, available, and accessible patients were included in the data collection.

The sampling method interprets the imbalance in some patients’ characteristics, including surgical site and type, the medications used per-operatively (whether in exclusive or in various combination nature), mainly caused by patients being diagnosed and managed by different neurosurgeons, and tumor type (mostly benign), reflecting the natural epidemiology of primary spinal intradural-extramedullary tumors, where benign tumors like meningiomas and schwannomas are dominant.

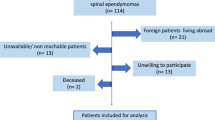

The sample size was calculated using G*Power 3.1.9.6 software25, with an effect size of 0.518 (based on means and standard deviation (SD) of a previous literature), given the recommended sample size was 32, while researcher eventually recruited a total of 134 spinal neurosurgery patients.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria: Adult patient between 18 and 65 years old who underwent spinal neurosurgery operation (e.g., herniated disc, spinal stenosis, degenerative spinal disease and tumors from the cervical and/or lumbar areas), and completed both pre-test and post-test PROMs questionnaires.

Exclusion criteria: Patients undergoing additional major surgeries or operations during the same admission, with severe cognitive or psychiatric conditions, or specific postoperative complications that required readmission during the one-month postoperative period.

Data collection tool and process

Data were collected between 25th of January and 15th of August 2024 using a structured questionnaire that consisted of five main sections: demographic data, pain, QoL, sleep quality, and mental health. Demographic factors also included additional information included the type of surgery, waiting time, and the use of specific pain killers.

The Arabic valid tools were used for PROMs assessment, including the ODI for lower back pain assessment among lumbar spine neurosurgery patients26, Neck Disability Index (NDI) for the cervical spine pain27, the EuroQoL 5-Dimension 5-Level (EuroQoL-5D-5 L) for QoL, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)28 and the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS)29 for sleep quality, and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)30 for mental status.

On the day of admission for each patient, the researcher collected the preoperative data in a specific Google Form that was prepared to include the mentioned sections, which was chosen for clinical relevance and accuracy of the collected data, in addition to standardization and consistency among all the targeted patients. One month after the operation, the researcher contacted the patients again via telephone and collected the postoperative PROMs data, using the same form.

As the study was constructed from a master’s thesis, the one-month follow-up period was limited by time constraints, therefore, determined by its scope and framework. Also, several previous studies on postoperative recovery and patient-reported outcomes after spinal surgeries have also employed short-term follow-up periods of 4 to 6 weeks31,32,33,34 to capture changes in pain, QoL and functional recovery.

Data analysis

For the purpose of data analysis, Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 25.0 was used to produce the descriptive and analytical results of the study’s data. Descriptive results included frequencies and percentages of patients’ demographics and statements of PROMs tools, as well as the mean and SD of scores. Analytical results included paired sample t-test for pre- and postoperative differences in PROMs scores, independent samples t-test and one-way ANOVA for mean differences across demographic factors, and Pearson Correlations, with a significance set at p-value < 0.05. Effect sizes were calculated to quantify the magnitude of change in PROMs, where Cohen’s d for t-test and eta-squared (η2) for ANOVA models were interpreted according to conventional benchmarks (small = 0.2/0.01, medium = 0.5/0.06, large = 0.8/0.14).

Results

Demographic data of the patients

Most of the patients who were recruited in the current study (70.1%) were in the later middle-aged adult group, with a mean age of 49.16 ± 6.06 years old, ranging from 32 to 66 years old. Around half of the sample were male patients (49.3%), with an approximate percentage of patients who live in rural areas (48.5%). Moreover, nearly half of the participants (45.5%) have a bachelor’s educational degree, while nearly three-fourths of them (74.6%) are married. In terms of professional life, 38.8% of the patients work in the private sector, compared to 23.9% who are self-employed, with 39.6% having between 1800 and 3000 ILS of monthly income, as shown in Table 1.

In terms of the operation-related data, most of the patients (73.9%) underwent a lumbar spine neurosurgery approach, compared to 26.1% for the cervical approach. Of these patients, 59.7% underwent discectomy, while around one-third of them (29.9%) underwent tumor resection. The patients had a mean period between diagnosis and operation of 7.15 ± 4.68 weeks, with a mean weight of 80.31 ± 7.40 kg, ranging from 64 to 99 kg, while the mean height was 169.28 ± 7.51 centimeters, ranging from 150 to 185 centimeters, giving a mean Body Mass Index (BMI) of 28.17 ± 3.47 kg/m2, giving an overall overweight status, which ranged from 20.52 to 38.46 kg/m2. The most common comorbidities found among the patients were hypertension (29.9%), followed by diabetes mellitus (24.6%) and hormonal issues (14.9%). During the preoperative period, more than two thirds of the patients reported having paracetamol (69.4%), which was higher than NSAIDs (59.7%), for pain relief, while more than half of the patients have used muscle relaxants (54.5%), with a higher percentage of patients who reported consuming corticosteroids (76.9%), as shown in Table 2.

Pain

For the patients who underwent cervical spine neurosurgery approach, the overall NDI score was calculated and categorized, where Table 3 showed a significant decrease in overall score from a mean of 53.847 ± 6.658 in the preoperative phase to a mean of 21.568 ± 5.283 in the postoperative phase, with a mean decrease by 32.279 (t = 26.943, p-value < 0.001), which was also reflected in the categories of NDI, where 85.7% of the patients had severe preoperative disability, which was significantly decreased to a percentage of 57.1% having moderate and 42.9% having minimal disabilities (t = 15.289, p-value < 0.001), indicating a significant improvement in neck pain after one month of the operation.

Patients who underwent lumbar spine neurosurgery approach were evaluated for their pain using ODI, with their overall and categorization shown in Table 4, where the overall score showed a significant decrease from a preoperative mean of 58.929 ± 5.438 to a postoperative mean of 24.687 ± 5.629, with a mean decrease by 34.242 (t = 47.424, p-value < 0.001), indicating an overall improvement in lumbar area pain after one month of the operation. In more detail, 68.7% of the patients had severe disability category in the preoperative phase, compared to 71.7% having moderate and 27.3% having minimal disability categories in the postoperative phase (t = 25.803, p-value < 0.001).

Quality of life (QoL)

The quality of life (QoL) among the recruited patients was assessed using the five-dimensional EuroQoL tool, where patients’ responses and pre-post comparison are shown in Table 5. The domain of mobility showed a significant improvement, where 58.2% of the patients had a moderate problem in walking, compared to 53.0% having a slight problem in walking in the postoperative phase (t = 8.242, p-value < 0.001). The same pattern was witnessed in other domains. For example, the problem in self-care was moderate among 49.3% of the patients in the preoperative phase, while it was slight among 52.2% of them postoperatively (t = 6.797, p-value < 0.001), with 59.7% having severe preoperative problems in usual activities, compared to 63.4% having slight related problems (t = 16.930, p-value < 0.001). Also, problems related to pain or discomfort were severe among 73.9% of the patients in the preoperative phase, compared to slight among 56.7% of them in the postoperative phase (t = 19.497, p-value < 0.001). Lastly, anxiety issues were severe among 52.2% of the patients preoperatively, compared to 54.5% with slight and 40.3% with no related problems in the postoperative phase (t = 13.302, p-value < 0.001).

The overall VAS mean significantly improved from 21.642 ± 13.500 in the preoperative phase to a mean of 68.508 ± 22.158 in the postoperative phase, with a mean increase of 46.9 points (t = -28.720, p-value < 0.001). The utility score also showed a significant improvement from a mean of 0.0637 to 0.7012, with a mean improvement of 0.638 points (t = -20.753, p-value < 0.001).

Sleep quality

According to the scoring of the PSQI tool, the global PSQI score showed a significant decrease from a preoperative mean of 13.522 ± 1.995 to a postoperative mean of 7.866 ± 1.969, with a mean decrease of 5.657 points (t = 26.830, p-value < 0.001). In addition, all components of sleep quality showed significant improvements between the preoperative and the one-month postoperative phases, including sleep latency (2.687 ± 0.554 to 1.873 ± 0.896, respectively, t = 16.309, p-value < 0.001), sleep efficiency (1.403 ± 1.034 to 0.358 ± 0.481, respectively, t = 10.769, p-value < 0.001), and daytime dysfunction (1.903 ± 0.533 to 0.851 ± 0.569, respectively, t = 18.345, p-value < 0.001), except for sleep duration (1.388 ± 1.501 to 1.522 ± 1.505, respectively, t = -0.749, p-value = 0.455), as shown in Table 6.

The daytime sleepiness of the recruited patients was assessed using ESS, as shown in Table 7. All areas of sleepiness have witnessed significant improvements from the preoperative to one-month postoperative phases, where majority of the issues happened “mostly” in the preoperative phase, and turned to become rare or never happening in the postoperative phase, including sleepiness while sitting and reading (68.7% mostly vs. 52.2% never, respectively, t = 17.939, p-value < 0.001), as well as while watching TV (64.2% mostly vs. 48.5% never, respectively, t = 17.094, p-value < 0.001), and while lying down to rest (57.5% mostly vs. 50.7% rarely, respectively, t = 12.748, p-value < 0.001). This also applies for sleepiness while sitting after a lunch (57.5% mostly vs. 44.8% rarely, respectively, t = 11.654, p-value < 0.001).

Other differences were less significant, including sleepiness while being a passenger in a car (from 70.1% rarely to 61.9% never, respectively, t = 11.464, p-value < 0.001) and while sitting and talking (from 67.2% rarely to 64.2% never, respectively, t = 8.672, p-value < 0.001). Overall, the score of ESS significantly decreased from a preoperative mean of 11.425 ± 2.328 to a postoperative mean of 4.672 ± 1.867, with a mean decrease by 6.754 points (t = 37.539, p-value < 0.001), indicating an overall significant decrease in sleepiness in the one-month postoperative phase.

Mental health

The mental status of the patients was assessed using the PHQ-9 tool, where the overall score and categorization are explained in Table 8, which shows that the overall score significantly decreased from a preoperative mean of 12.00 ± 2.639 to a postoperative mean of 4.31 ± 1.890 (t = 37.650, p-value < 0.001), with 67.9% of the patients categorized as having moderate depression in the preoperative phase, compared to 54.1% of them having minimal, and 45.1% having mild, depression in the postoperative phase (t = 29.079, p-value < 0.001).

Differences in proms improvement across patients’ characteristics

As shown in Table 9, which tested the significance of differences in preoperative-postoperative PROMs scores across the categories of patients’ demographic factors, the age of the spinal neurosurgery patients was significantly related with differences in both EQ-VAS and ESS scores, where the highest improvement in VAS scores the represent their QoL are significantly noticed among patients between 30 and 44 years old with a medium effect size (mean difference = 53.33, F = 2.365, η2 = 0.035) than older patients, with a significant, negative mild correlation between patients’ age and the mean difference of VAS after one month of the operation (r = -0.184, p-value < 0.05), which indicates and overall better improvement in spinal neurosurgery patients’ QoL among younger patients. Also, the daytime sleepiness significantly improved among older patients with a medium effect size, for example, among patients 60 years old and more (mean difference = -8.86) compared to those who are between 45 and 59 years old (mean difference = -6.50, F = 4.821, η2 = 0.069), without a significant correlation between age and improvement in daytime sleepiness.

The residency of the patients also significantly impacted the improvement in NDI scores with a small effect size, where the mean difference was − 35.26 among patients living in urban areas, compared to -30.22 among rural area residents and − 29.14 among residents of refugee camps (F = 2.987, Cohen’s d = 0.157, p-value < 0.05), which indicates a better improvement in NDI among urban area residents than others. On the other hand, none of the rest of the spinal neurosurgery patients’ demographic factors showed significant relationships with the improvements in postoperative PROMs (p-value > 0.05).

When the medical and health-related factors of spinal neurosurgery patients were tested in having significant relationships with the improvement in postoperative PROMs, more factors showed significant results, as shown in Table 10. For example, there was a significant improvement in NDI scores with a moderate effect size among spinal neurosurgery patients who underwent congenital diseases-related surgeries (mean difference = -36.67) compared to discectomy (mean difference = -33.04) and tumor resection (mean difference = -29.64) approaches, indicating an overall higher improvement in NDI among patients with congenital diseases (F = 2.689, η22 = 0.071, p-value < 0.05). Also, differences in ODI scores showed significant differences with a moderate effect size across types of surgeries, where tumor resection patients (mean difference = -36.67) showed better improvement than patients of discectomy (mean difference = -33.05) and congenital diseases (mean difference = -33.83), indicating an overall better improvement in back pain index among patients with tumor-related spinal neurosurgical disorders (F = 2.951, η2 = 0.051, p-value < 0.05).

Moreover, patients without hormonal disorders showed more significant improvement with a moderate effect size in ODI scores (mean difference = -34.99) than patients with related disorders (mean difference = -30.38), indicating a better improvement in back pain index among patients who do not present with preoperative hormonal disorders (t = 2.409, Cohen’s d = 0.658, p-value < 0.05). Also, patients who reported using preoperative paracetamol for pain management showed less improvement in EQ-VAS scores (mean difference = 43.76) compared to patients who consumed them preoperatively (mean difference = 53.9), which applies for the use of muscle relaxants (mean difference = 41.78 vs. 52.95, respectively), indicating and overall less improvement in postoperative QoL VAS scores with moderate effect sizes among patients who consumed preoperative paracetamol (t = -2.095, Cohen’s d = -0.393) or muscle relaxants (t = -2.512, Cohen’s d = -0.436). In terms of the ODI scores, patients who reported using preoperative cortisones significantly showed less improvement (mean difference = -33.09) than who did not use them (mean difference = -37.83) with a moderate effect size, indicating an overall less improvement in back pain index among patients who reported preoperative cortisones (t = 2.919, Cohen’ d = 0.685, p-value < 0.05). On the other hand, the rest of the medical and health-related factors did not significantly affect the improvement in postoperative PROMs among spinal neurosurgery patients (p-value > 0.05).

Discussion

The current study is the first study in Palestine to evaluate the early postoperative changes in multiple PROMs among spinal neurosurgery patients (health-related quality of life (HRQoL), sleep quality and mental health). All PROMs showed statistically significant improvements at one month following the surgery, which provides crucial insights into the multidimensional nature of early recovery, as well as specific concordance and discrepancy with prior literature.

Focusing on areas related to disability and functional recovery, the current study showed significant disability decrease, as measured by both ODI and NDI tools, which is consistent with previous studies35,36,37. The baseline ODI mean score was notably higher among our patients, which may indicate a greater preoperative disability burden among Palestinian patients, mostly related to late presentation and differences in access to care. The sharper decline in ODI scores may also suggest notable functional gains and rapid recovery within just one month postoperatively following decompression or tumor resection. On the other hand, early improvements should be interpreted with caution, as other previous literature shows continued improvements beyond three to six months38, which may indicate a partial rather than full recovery among the patients of the current study. Also, the used functional disability scales are limited to physical functions only, and may not fully reflect emotional or social picture.

Significant improvement in back pain were also observed among patients who underwent tumor resection compared to other types, which is similar to the findings of Chouhdari and colleagues39. Focusing on tumor part, it is worth mentioning that the sample of the study predominantly consisted of patients with benign tumor types, which is similar to the epidemiological findings of previous studies40,41,42, like schwannomas and meningiomas. Significant improvements in PROMs after resection of such benign intradural-extramedullary tumors was also supported by findings of previous studies43,44,45. It is recommended for future research to use domain-specific tools, as VAS is less granular in isolating pain as a domain.

Moving to HRQoL, the current study showed significant improvements the overall QoL and subjective health perception postoperative, using EQ-5D and EQ-VAS. Our study showed more profound change in the utility scores in comparison with the previous study of Hey and colleagues35, reflecting a possibly lower baseline QoL among Palestinian population, mostly related to socioeconomic hardship, late presentation and limited multidisciplinary preoperative care access. Although, the exclusion of patients with postoperative complications may have skewed outcomes toward more favorable results.

While previous studies46,47 utilized PSQI foe sleep quality to find that spinal pathology patients suffer from sleep disturbances, few of them have conducted pre-post analyses. The findings of our study support the hypothesis related to getting better sleep when pain and psychological distress are reduced. While the used sleep quality tools are validated, they remain subjective and may not capture the complexity of neurophysiological sleep disorders, with the presence of other factors, such as social support and communal living, especially in a conflict-affected country as in Palestine.

Mental health outcomes have shown significant postoperative improvement, as assessed by PHQ-9, which is consistent with literature that linked physical recovery to psychological well-being48,49. A specific preoperative finding is related to that 57.5% of the patients have denied thoughts of self-harm, which supports the preventive role of cultural and religious stigma surrounding suicide50.

The cultural norms may have influenced how depressive symptoms are perceived and reported, although the valid Arabic version was used, such as somatic expression of distress, that are often emphasized over emotional symptoms among Arab societies, leading to psychological complaints being underreported. Therefore, future research should consider supplementing standardized scales with culturally adapted qualitative assessment, and use mixed-methods approaches, to ensure a more comprehensive evaluation of depression among Palestinian patients.

Limitations

The current study’s strength mainly includes the use of validated Arabic PROMs and a prospective design, while several limitations should be considered, like the use of observational, single-center design, with the absence of a control group and multivariate analyses that limits causal inference, in addition to the short one-month follow-up that restricted evaluation of long-term outcomes. Also, the exclusion of complicated cases may have limited generalizability of results. Lastly, the geopolitical and logistical constraints have affected recruitment feasibility, though the study hospital serves a population with diverse demographics. These findings are considered as a foundation for future research that is recommended to be conducted in multicenter, long-term and controlled approach.

Implications

Despite the mentioned limitations, the value of conducting health outcomes research in such underrepresented populations is worth being highlighted, contributing important data on having achievable substantial PROMs improvements even within constrained systems. The findings of the current study encourage patients on education management through counselling on expected recovery timelines and influencing factors, necessity of social support and postoperative adherence. Among healthcare providers, it is recommended to utilize pre- and post-operative care through holistic assessment, and individualized care plans by recognizing variability in recovery based on corresponding factors.

Lastly, policymakers should struggle to provide equity in access to neurosurgical and rehabilitation services, especially among disadvantaged populations, in addition to the use of standardized PROMs in guidelines to support quality monitoring and cross-facility benchmarking. Multicenter studies and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that include private and governmental sectors are recommended to generate context-specific and evidence-based practices in current settings. Moreover, outcomes are recommended to be studied over longer, multiple follow-up periods.

Conclusions

The current prospective study was conducted on convenience sample of 134 lumbar and cervical spine neurosurgery patients to assess differences in pre- and post-operative PROMs related to pain, QoL, sleep quality and mental health using Arabic valid tools, which all showed significant early improvement at the one-month postoperative time point. Some patients’ factors have independently contributed to significant differences in postoperative improvements.

Several studies agreed with the overall improvements in postoperative PROMs among spinal neurosurgery patients, with some differences related to the used tools, sample characteristics and population-related factors, which calls for the importance of personalized care approaches.

Future research in Palestine should strengthen the generalizability and better assess the durability of outcomes by including larger, multi-center, controlled samples and longer follow-up periods, with the conduction of multivariate analyses. Using culturally sensitive assessment tools will also strengthen causal interpretation and provide more comprehension into recovery after spinal neurosurgeries.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Additional supporting materials, including the institutional approval letters, supplementary figures and charts, and the approval from the Palestinian Ministry of Health, are available in the Supplementary Material. All requests relating to data should be addressed to [ahmadaadaqqa@gmail.com](mailto: ahmadaadaqqa@gmail.com) .

Abbreviations

- ACDF:

-

Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion

- ADLs:

-

Activities of Daily Living

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of Variance

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- EQ-5D-5L:

-

EuroQoL-5 Dimension-5 Level

- ESS:

-

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

- HCPs:

-

Healthcare Providers

- HRQoL:

-

Health-Related Quality of Life

- ILS:

-

Israeli Shekel (Currency)

- IRB:

-

Institutional Review Board

- NDI:

-

Neck Disability Index

- NIH:

-

National Institute of Health

- NSAIDs:

-

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

- ODI:

-

Oswestry Disability Index

- PHQ-9:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire

- PMC:

-

Palestine Medical Complex

- PROMs:

-

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measures

- PROs:

-

Patient-Reported Outcomes

- PSQI:

-

Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index

- QoL:

-

Quality of Life

- RCT:

-

Randomized Controlled Trial

- RMDQ:

-

Ronald-Morris Disability Questionnaire

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for Social Sciences

- SRS:

-

Scoliosis Research Society

- VAS:

-

Visual Analogue Scale

References

Tatman, L. M. & Obremskey, W. T. Patient reported outcomes: The foundation of value. J. Orthop. Trauma. 33(Suppl 7), S53–S55 (2019).

Baumhauer, J. F. & Bozic, K. J. Value-based healthcare: Patient-reported outcomes in clinical decision making. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 474, 1375–1378 (2016).

Beighley, A. et al. Patient-reported outcome measures in spine surgery: A systematic review. J. Craniovertebr Junction Spine. 13(4), 378–389 (2022).

Ghimire, D., Hurwitz, M. & Ashkan, P. PP53. Proms in neurosurgery: Where are we now? Neuro-Oncology 19, i15 (2017).

Ghimire, P., Hasegawa, H., Kalyal, N., Hurwitz, V. & Ashkan, K. Patient-reported outcome measures in neurosurgery: A review of the current literature. Neurosurgery 83, 622–630 (2018).

Ramesh, R. et al. Patient-reported outcome measures in cerebrovascular neurosurgery. J. Neurosurg. 140, 1357–1368 (2023).

Hartmann, C., Fischer, K., Haneke, H. & Kirchberger, V. Patient-reported outcomes in spinal surgery-how can we keep getting better? J. Spine Surg. 6(4), 820–824 (2020).

Mekhail, N., Costandi, S., Abraham, B. & Samuel, S. W. Functional and patient-reported outcomes in symptomatic lumbar spinal stenosis following percutaneous decompression. Pain Pract. 12(6), 417–425 (2012).

Sutherland, J. M. et al. Comparing patient-reported outcomes across countries: an assessment of methodological challenges. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 26(3), 163–171 (2021).

Van Der Wees, P. J. et al. Integrating the use of patient-reported outcomes for both clinical practice and performance measurement: Views of experts from 3 countries. Milbank Q. 92(4), 754–775 (2014).

Cheung, Y. T. et al. The use of patient-reported outcomes in routine cancer care: Preliminary insights from a multinational scoping survey of oncology practitioners. Support Care Cancer. 30(2), 1427–1439 (2022).

Fagundes, C. P. et al. Symptom recovery after thoracic surgery: Measuring patient-reported outcomes with the MD Anderson symptom inventory. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 150(3), 613–9e2 (2015).

Shi, Q. et al. Patient-reported symptom interference as a measure of postsurgery functional recovery in lung cancer. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 52(6), 822–831 (2016).

Marek, R. J., Lieberman, I., Derman, P., Nghiem, D. M. & Block, A. R. Validity of a pre-surgical algorithm to predict pain, functional disability, and emotional functioning 1 year after spine surgery. Psychol. Assess. 33 (6), 541–551 (2021).

Rubery, P. T., Houck, J., Mesfin, A., Molinari, R. & Papuga, M. O. Preoperative patient reported outcomes measurement information system scores assist in predicting early postoperative success in lumbar discectomy. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976). 44 (5), 325–333 (2019).

Winebrake, J. P., Lovecchio, F., Steinhaus, M., Farmer, J. & Sama, A. Wide variability in patient-reported outcomes measures after fusion for lumbar spinal stenosis: A systematic review. Global Spine J. 10 (2), 209–215 (2020).

Silveira Bianchim, M. et al. The implementation, use and impact of patient reported outcome measures in value-based healthcare programmes: A scoping review. PLoS One 18, e0290976 (2023).

Schiavolin, S., Broggi, M., Ferroli, P., Leonardi, M. & Raggi, A. Letter: Patient-reported outcome measures in neurosurgery: A review of the current literature. Neurosurgery 83(1), E54–E5 (2018).

Najjar, S. et al. Similarities and differences in the associations between patient safety culture dimensions and self-reported outcomes in two different cultural settings: a National cross-sectional study in Palestinian and Belgian hospitals. BMJ Open. 8, e021504 (2018).

Dunbar, M. R. & Ghogawala, Z. Patient-reported outcomes. In: Quality Spine Care (2018).

Nshuti, S. et al. (eds) Long-Term Systematic Outcome Assessment of Patients Following Spine Surgery in Rwanda: The Use of Patient Reported Outcome Tools (2020).

Schober, P. & Vetter, T. R. Repeated measures designs and analysis of longitudinal data: If at first you do not succeed—Try, try again. Anesth. Analg. 127, 569–575 (2018).

Kwon, J.-Y., Sawatzky, R., Baumbusch, J. L., Lauck, S. B. & Ratner, P. A. Growth mixture models: A case example of the longitudinal analysis of patient-reported outcomes data captured by a clinical registry. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. ;21, 79 (2021).

Stonbraker, S., Porras, T. & Schnall, R. Patient preferences for visualization of longitudinal patient-reported outcomes data. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. JAMIA 27, 212–224 (2019).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A-G. & Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods. 39(2), 175–191 (2007).

Algarni, A. S., Ghorbel, S., Jones, J. G. & Guermazi, M. Validation of an Arabic version of the Oswestry index in Saudi Arabia. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 57(9), 653–663 (2014).

Shaheen, A. A., Omar, M. T. & Vernon, H. Cross-cultural adaptation, reliability, and validity of the Arabic version of neck disability index in patients with neck pain. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976). 38(10), E609–E615 (2013).

Suleiman, K. H., Yates, B. C., Berger, A. M., Pozehl, B. & Meza, J. Translating the Pittsburgh sleep quality index into Arabic. West. J. Nurs. Res. 32(2), 250–268 (2010).

Attal, B. A., Al-Ammar, F. K. & Bezdan, M. Validation of the Arabic version of the Epworth sleepiness scale among the Yemeni medical students. Sleep. Disord. 2020, 6760505 (2020).

AlHadi, A. N. et al. An Arabic translation, reliability, and validation of patient health questionnaire in a Saudi sample. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry. 16(1), 32 (2017).

Asch, H. L. et al. Prospective multiple outcomes study of outpatient lumbar microdiscectomy: Should 75 to 80% success rates be the norm? J. Neurosurg. Spine. 96(1), 34–44 (2002).

Bovonratwet, P. et al. Association between patient reported outcomes measurement information system physical function with postoperative pain, narcotics consumption, and patient-reported outcome measures following lumbar microdiscectomy. Glob. Spine J. 14(1), 225–234 (2024).

Pereira, M. et al. Responsiveness and interpretability of the Portuguese version of the neck disability index in patients with chronic neck pain undergoing physiotherapy. Spine. 40, E1180–E1186 (2015).

Wolf, J. C. et al. Do six-week postoperative patient-reported outcomes predict long-term clinical outcomes following lumbar decompression? World Neurosurg. 185, e900–e906 (2024).

Hey, H. W. D. et al. The predictive value of preoperative health-related quality-of-life scores on postoperative patient-reported outcome scores in lumbar spine surgery. Glob. Spine J. 8(2), 156–163 (2018).

Croci, D. M. et al. Differences in postoperative quality of life in young, early elderly, and late elderly patients undergoing surgical treatment for degenerative cervical myelopathy. J. Neurosurg. Spine 37, 339–349 (2022).

Vaishnav, A. S. et al. Correlation between NDI, PROMIS and SF-12 in cervical spine surgery. Spine J. 20, 409–416 (2019).

Shahi, P. et al. Improvement following minimally invasive lumbar decompression in patients 80 years or older compared with younger age groups. J. Neurosurg. Spine 37, 828–835 (2022).

Chouhdari, A. et al. Effect of basic characteristics on improving quality of life after lumbar spine decompression surgery. Arch. Neurosci. 6, e90159 (2019).

El-Hajj, V. G., Pettersson-Segerlind, J., Fletcher-Sandersjöö, A., Edström, E. & Elmi-Terander, A. Current knowledge on spinal meningiomas epidemiology, tumor characteristics and non-surgical treatment options: A systematic review and pooled analysis (Part 1). Cancers 14(24), 6251 (2022).

Kumar, N., Tan, W. L. B., Wei, W. & Vellayappan, B. A. An overview of the tumors affecting the spine-inside to out. Neurooncol. Pract. 7(Suppl 1), i10–i17 (2020).

Liu, L., Shi, L., Su, Y., Wang, K. & Wang, H. Epidemiological features of spinal intradural tumors, a single-center clinical study in Beijing, China. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 25 (1), 613 (2024).

Viereck, M. J., Ghobrial, G. M., Beygi, S. & Harrop, J. S. Improved patient quality of life following intradural extramedullary spinal tumor resection. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 25(5), 640–645 (2016).

Newman, W. C. et al. Improvement in quality of life following surgical resection of benign intradural extramedullary tumors: A prospective evaluation of patient-reported outcomes. Neurosurgery 88(5), 989–995 (2021).

Ali, A. M. S. et al. Patient-reported outcomes in primary spinal intradural tumours: A systematic review. Spinal Cord. 62(6), 275–284 (2024).

Kim, J. et al. Prevalence of sleep disturbance in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis and analysis of the risk factors. Spine J. 20, 1239–1247 (2020).

Marrache, M. et al. Persistent sleep disturbance after spine surgery is associated with failure to achieve meaningful improvements in pain and health-related quality of life. Spine J. 21(8), 1325–1331 (2021).

Kohrt, B. A., Luitel, N. P., Acharya, P. & Jordans, M. J. D. Detection of depression in low resource settings: validation of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) and cultural concepts of distress in Nepal. BMC Psychiatry ;16, 58 (2016).

Na, P. J. et al. The PHQ-9 item 9 based screening for suicide risk: a validation study of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ)—9 item 9 with the Columbia suicide severity rating scale (C-SSRS). J. Affect. Disord. 232, 34–40 (2018).

Wagner, A. et al. Psychological predictors of quality of life and functional outcome in patients undergoing elective surgery for degenerative lumbar spine disease. Eur. Spine J. 29(2), 349–359 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The author(s) would like to thank An-Najah National University (www.najah.edu) for the technical support provided to publish the present manuscript.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The article was processed from the master’s thesis of AD, who contributed to manuscript writing, primary data collection, and data analysis and interpretation. JQ contributed to supervision, scientific writing and interpretation and discussion of the results. AH and BS contributed to discussion of results and providing critical feedback. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and informed consent

Every study process adhered to the guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration for research with human beings. Approval was granted from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of An-Najah National University before the start of the data collection, which was followed by the approval from the MoH for starting data collection from the PMC. Also, before any data was collected, an Arabic consent form was received from each patient, which highlighted the aims of the study, components of the questionnaire, and follow-up process, with ensuring anonymity and confidentiality protocols. The names and phone numbers of the participants for the sake of follow-up were kept anonymous, and the data were used by the researcher and the supervisors for research purposes only. Finally, the patients had the ability to withdraw from the participation at any time, without the need to declare any reasons.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Daqqa, A.A., Qaddumi, J., Salameh, B. et al. Changes in pain, quality of life, sleep, and mental health after uncomplicated spinal neurosurgery in palestine: a prospective study of patient-reported outcomes. Sci Rep 15, 41841 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25850-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25850-3