Abstract

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a genetic condition affecting over 100,000 individuals worldwide. Lung disease is the main cause of mortality in CF, with chronic neutrophilic inflammation as a hallmark. Elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor (ETI) is a combination of highly effective CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) modulators, conferring significant pulmonary gains to treated patients. However, the extent to which ETI controls inflammation is uncertain. To investigate this, we quantified effector proteins, cytokines, and metabolites in sputum fluid supernatant from ETI-treated (n = 32) and treatment-naïve (n = 9) people with CF (pwCF). ETI-treated pwCF showed detectible ivacaftor and tezacaftor in sputum, and overall lower sputum neutrophil elastase (NE) activity than ETI-naïve pwCF, although they displayed a clear bimodal distribution [NEHi: median of 1415.3 ng/mL (IQ: 1113.6–1500.9), NELo: 83.2 ng/mL (IQ: 0–165.9)]. NEHi pwCF on ETI had higher levels of pro-inflammatory mediators, including IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α, MPO activity, and 107 metabolites associated with purine metabolism, proteolysis, and oxidative stress. These findings suggest pwCF on ETI who have high airway NE activity also have high inflammatory burden and a history of lower pulmonary function. Adjunctive neutrophil-targeted interventions may be beneficial for these individuals to receive maximal benefits from ETI therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is an autosomal recessive condition caused by mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), resulting in multi-organ pathology including the gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, lungs, reproductive organs, and others1,2. Progressive respiratory failure remains the leading cause of death among people with CF (pwCF), characterized by airway obstruction, polymicrobial infections, and chronic neutrophilic inflammation2. The highly effective modulator therapy (HEMT) cocktail elexacaftor-tezacaftor-ivacaftor (ETI, marketed as Trikafta™ฏ in Northern America and Oceania and Kaftrio™ฏ in Europe) is indicated for the treatment of pwCF who have at least one F508del mutation in the CFTR gene, accounting for approximately 90% of ≥ 2-year-old pwCF, though access may be limited by drug cost and potential toxicity1.

Use of ETI is associated with rapid increases in pulmonary function and decreased airway obstruction3,4,5. By enhancing CFTR chloride channel activity, ETI is anticipated to increase airway hydration, consistent with observations of decreased mucus viscosity and increased airway clearance6. Notably, spontaneous sputum expectoration appears to cease for many individuals days or weeks after ETI initiation, and emerging evidence suggests ETI has meaningful anti-inflammatory benefits7. In a longitudinal study by Schaupp et al., ETI decreased sputum neutrophil elastase (NE) and IL-1β, while having less impact on other inflammatory markers such as IL-8, IL-6, TNF-ɑ, cathepsin G, and proteinase-38. The longitudinal study of Casey et al. showed anti-inflammatory effects in sputum across the aforementioned range of targets, except IL-6 and TNF-ɑ (not analyzed), with resolution to levels comparable to non-CF bronchiectasis disease controls7. Lepissier et al. found sputum NE, IL-1β, and IL-8 all decreased a month after ETI initiation9. ETI has also been observed to decrease sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage neutrophils7,10, and systemic inflammatory mediators such as IL-6, IL-8, IL-17 A, and C-reactive protein, as well as diminishing the airway count of neutrophils7,11.

ETI has led to substantial improvements in lung function for the majority of eligible pwCF, but responses to ETI among pwCF are likely to be heterogeneous and influenced by the state of disease. Studies conducted by Quinn et al. showed pwCF with worse lung function exhibited higher sputum metabolite diversity and greater prevalence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, while those with better lung function had lower metabolite diversity and fewer pathogenic bacteria12. These authors reported higher NE- and cathepsin G-derived peptides in sputum of pwCF that associated with worse lung function, along with increased free amino acids which correlated with P. aeruginosa burden. In the context of ETI initiation, Sosinski et al. reported a significant decrease in the abundance of CF sputum peptides, amino acids, and kynurenine pathway metabolites13. Moreover, Martin et al. reported considerable interindividual variation in sputum metabolome and microbiome dynamics after ETI initiation and prolonged use14. These results highlight the importance of identifying sub-populations of individuals taking ETI who may greatly benefit from adjunctive therapies addressing inflammation and infection.

Here, we sought to better understand the heterogeneity of response to ETI among clinically stable adults with CF by conducting a cross-sectional, single-center study of sputum from pwCF taking ETI (“ETI” group). First, we compared sputum of those on ETI to CF controls taking no form of HEMT (“NoHEMT” group). We analyzed activities of NE and myeloperoxidase (MPO), immune mediators, and metabolites in sputum supernatant. We also retrospectively analyzed pulmonary function data. While differences between ETI and NoHEMT were modest and likely constrained by small sample size, we observed a bimodal distribution of sputum NE activity within the ETI group. We found that pwCF who had higher sputum NE activity (“NEHi” group) showed extensive molecular evidence of neutrophilic inflammatory pathology, and also had lower lung function prior to and up to three years after ETI initiation, compared to those with low sputum NE activity (“NELo” group).

Materials and methods

Human subjects

Forty-one adults with CF provided spontaneously expectorated sputum at clinically stable visits (no current or recent pulmonary exacerbation). Subjects with CF were enrolled at Emory University and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta and informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their involvement in the study, as part of the CF Biospecimen Repository (CFBR) protocol, with all aspects of subject enrollment and sample collection approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board (IRB00042577) and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Subject demographics are summarized in Table 1 and detailed in Supplementary Table S1 (deidentified information per donor). Sputum samples were collected cross-sectionally. Longitudinal pulmonary function data (via percent predicted forced expiratory volume in one second, ppFEV1) were retrospectively retrieved from electronic medical records. ppFEV1 was calculated from these data using the reference equations for pulmonary function as published by the Global Lung Function Initiative15.

Sputum processing

Expectorated sputum was homogenized and supernatant isolated as we previously described16. In brief, 3 mL of PBS supplemented with 2.5 mM EDTA was added per g of sputum. The mixture was homogenized by passing through an 18G needle, up and down, 4 times per mL. The homogenized sputum homogenate was centrifuged at 800 g and 4 ˚C for 10 min to yield cell-free supernatant, and this supernatant was centrifuged at 3000 g and 4 ˚C for 10 min to remove any bacteria or large debris that may be present. The resulting sputum supernatant was stored at −80˚C until ready to be assayed.

NE and MPO activity assays

Free NE activity was quantified in sputum using the Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) probe NEmo-1, as described before17. Forty µL of diluted sputum supernatant were added in polystyrene 96-well assay plates. The reaction was initiated by adding 5 µM NEmo-1 and reporter cleavage was recorded over time. A standard curve from known concentrations of purified human NE (Calbiochem) was included in each assay. Values below the detection limit of the FRET assay (which demonstrates high linearity and a clear zero intercept) were assigned a value of zero, as these samples exhibited no detectable enzyme activity17.

MPO activity was measured using an Amplex Red-based procedure as previously described18,19. Briefly, MPO is immunocaptured on high protein-binding plates. A mixture of Amplex Red, sodium bromide, and hydrogen peroxide are introduced and activity is detected based on the fluorescent resorufin product, and calibrated using an authentic MPO standard.

Immune mediator quantification

The concentration of immune mediators was quantified using a 20-plex chemiluminescent assay (U‐PLEX; Meso Scale Diagnostics), as we previously described20. Sputum supernatants were analyzed for the following cytokines and chemokines: chemokine ligand (CCL) 2 (CCL2), CCL4, CXC motif chemokine ligand (CXCL) 5 (CXCL5), CXCL10, CXCL11, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), interferon gamma (IFN-γ), interleukin (IL)−1α (IL-1α), IL-1β, IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA), IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-18, IL-22, IL-29, macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), and vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A). A value of half the lower limit of detection was imputed for samples determined to be below the lower limit, and twice the upper limit of detection was assigned for samples assayed over the upper limit (in both cases, before dilution factors were applied), a common practice for multiplex immunoassays wherein true absence of the analyte versus sensitivity limitations are difficult to distinguish. Owing to large numbers of values below the lower limits of quantification (> 50% in at least one experimental group), GM-CSF and IL-22 were ultimately excluded from analyses. Because IL-1RA and IL-8 concentrations were above limits of quantification in the Mesoscale assay, they were re-assayed using enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) kits (RayBiotech), according to manufacturer’s guidelines. For both IL-1RA and IL-8, ELISA data are presented in lieu of Mesoscale data.

Metabolomics

Metabolites in sputum were extracted and measured analogous to previously described methods18,21. In brief, 50 µL of sputum supernatant were mixed with 100 µl of 1:1 acetonitrile and methanol containing 12.5 µM d5-hippuric acid, vortexed for 5 s, and incubated on ice for 30 min. Samples were centrifuged at 20,000 g and 4 ˚C for 10 min to yield clear supernatant. Next, 100 µL of extract were transferred into a new tube and stored at −80 ˚C. A small, equal volume of each extract was pooled to make a global quality control. Data acquisition was conducted using a Vanquish Horizon liquid chromatography system coupled to a Q Exactive High Field Hybrid Orbitrap mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher). In brief, 2.5 µL of extract per sample were injected for liquid chromatography with a 5 μm, 2.1 × 150 mm iHILIC-(P) Classic column (HILICON) pumped at 0.2 mL/min and 40 ˚C with a 15-min gradient of water containing 15 mM ammonium acetate, pH 9.4 (mobile phase A) or acetonitrile (mobile phase B). The gradient began at 10% A and progressed to 90% A, followed by a 2-min hold and 8-min re-equilibration of the column at 10% A. Column eluate was introduced to a heated electrospray ionization source held at 320 ˚C and + 3.5 or −2.75 kV for positive and negative ionization modes, respectively, and an ion capillary temperature of 275 ˚C. The automatic gain control (AGC) was set to 1 × 106 ions with a maximum injection time of 200 ms. Scan range was 67–1000 m/z and Orbitrap resolution was 120,000 full width at half maximum (FWHM). We used Top20 N for data-dependent MS/MS acquisition, with dynamic exclusion of 8.0 s, AGC of 1 × 105, and maximum injection time of 25 ms. The data acquisition sequence was randomized before injection and the global quality control was injected every 10 samples to determine measurement reproducibility. Data were analyzed using Compound Discoverer 3.3 and FreeStyle 1.7 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). An in-house standard library was used for metabolite annotations according to accurate mass-retention time, and mzCloud (mzcloud.org) and LipidSearch (ThermoFisher) were used for MS/MS identifications.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted in GraphPad Prism (10.6.0) and Excel. We employed nonparametric statistics to describe central tendency (median, interquartile range) and assess group differences (Mann-Whitney test). Metabolomic data were analyzed using Metaboanalyst22 (metaboanalyst.ca), with log10 data transformation and autoscaling prior to analysis, followed by Mann-Whitney test. When conducting cytokine and metabolite analyses, owing to multiple variable testing within either assay, p-values were controlled using the Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple testing (q < 0.05).

Results

Study demographics

We analyzed 39 clinically stable pwCF, consisting of 30 undergoing ETI therapy (“ETI”) and 9 not receiving any modulator treatment (“NoHEMT”). Summary demographics and clinical characteristics are provided in Table 1, with individualized, fully deidentified data presented in Supplementary Table S1. Sputum donors must have been taking ETI for at least 3 months to be included in the ETI group. Because of limited sputum volumes and incomplete clinical records, not all analyses were carried out for every subject; deviations in sample size for specific assays are noted in figure and table legends.

ETI and NoHEMT groups did not significantly differ in age, sex, race, lung function, BMI, sputum culture, pancreatic sufficiency, or use of insulin therapy. However, the distribution of CFTR genotypes in pwCF taking ETI trended toward more F508del homozygosity and less non-F508del homozygosity (p = 0.0651, Fisher’s exact test; Table 1). This result could be anticipated based on requirements of ETI eligibility3. Prior history of HEMT use was significantly overrepresented in pwCF taking ETI at the time of sputum donation for this study (p = 0.0142; Table 1). Almost half (46.7%) of pwCF in the ETI group had a prior history of using tezacaftor-ivacaftor. In summary, prior ETI history distinguished these groups, as well as a trend toward different CFTR genotype distributions, but they were otherwise undistinguishable.

Differences in sputum inflammatory profiles of PwCF taking ETI or no HEMT

We sought to compare pwCF taking ETI to individuals who were not taking HEMT. First, we analyzed immune mediator levels in sputum supernatants. Across 18 mediators analyzed in total, none were significantly different between the two groups after adjusting for multiple comparisons (Supplementary Figure S1). We also analyzed differences in sputum metabolites between these two groups. In total, we detected 380 metabolites in sputum supernatant that could be annotated with high confidence using a combination of reference standard matching to accurate mass and retention time and/or mzcloud.org MS2 spectral library matches. However, when comparing sputum metabolomes of pwCF taking ETI to those not taking HEMT, the only differences we observed were for ivacaftor (Mann-Whitney p = 9.9 × 10− 8, q = 3.9 × 10− 5) and tezacaftor (Mann-Whitney p = 6.9 × 10− 7, q = 1.3 × 10− 4) (Supplementary Figure S2). These results were expected considering that they are two components of ETI therapy, although to the best of our knowledge this is the first report of them being detected in sputum. Note that we did not detect elexacaftor in sputum with the method used in this study.

Lastly, we considered NE and MPO activities, as these are critical effector molecules of neutrophils that modify the airway environment in CF. NE activity was significantly higher in pwCF not taking HEMT compared to those on ETI (Fig. 1A; NoHEMT: median 1,553 ng/mL, n = 9; ETI: median 930 ng/mL, n = 30; p = 0.0090). In contrast, MPO activity did not significantly differ between the two groups (Fig. 1B; NoHEMT: median 4,638 ng/mL, n = 9; ETI: 932 ng/mL, n = 25; p = 0.2664). For both enzymes, there was a wide range of variation within groups. In particular, we noted that the significant difference in NE was driven by an obvious bimodal distribution of NE activity above or below 400 ng/mL among pwCF taking ETI, with 13 of 30 (43%) falling below this threshold. Only one of nine (11%) NoHEMT subjects also had sputum NE activity below the same threshold. Reasoning that the two sub-populations likely had major differences in disease that may impact outcomes of ETI therapy, we decided to further investigate them.

PwCF taking ETI had lower NE activity driven by an activity low (NELo) sub-population. (A) NE activity in sputum supernatant was significantly lower in pwCF taking ETI than in those with no HEMT, owing to an activity low sub-population. The cutoff of 400 ng/mL activity, delineating NEHi and NELo subpopulations, is marked with a dashed line. n = 30 pwCF on ETI and n = 9 taking no HEMT. (B) MPO activity in sputum supernatant was not statistically significant between the two groups. Statistical significance is derived from Mann-Whitney test. n = 25 pwCF on ETI and n = 9 taking no HEMT.

High or low NE activity distinguishes two populations of PwCF undergoing ETI therapy

We reinterrogated MPO, immune mediators, and metabolites in the context of low (NELo) or high (NEHi) sputum NE activity among pwCF taking ETI. MPO activity was significantly higher in NEHi subjects compared to NELo subjects (Fig. 2A; p = 0.0002). Similarly, 12 (of 18) immune mediators assessed were significantly different (p < 0.05 and q < 0.05, each). Three (CXCL5, and interferon-responsive CXCL10, and CXCL11; Fig. 2B-D) were lower and seven (G-CSF, IFNγ, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, M-CSF, TNF-ɑ, VEGF-A; Fig. 2E-M) were higher, respectively, in NEHi vs. NELo subjects. These data suggest an overall increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines and suppression of interferon responses in NEHi subjects, which is consistent with high neutrophil burden and rewiring of immune crosstalk. Non-significant differences between the two groups for the remaining six immune mediators are shown in Supplementary Figure S3.

PwCF taking ETI with high NE activity have higher sputum MPO activity and pro-inflammatory cytokine burden, and lower CXC chemokines. (A) MPO activity significantly differed between NEHi and NELo subpopulations (n = 14 and n = 11, respectively). P-value shown is from Mann-Whitney test. (B-M) Twelve immune mediators assayed using Mesoscale or ELISA assay that were significantly different between NEHi and NELo subpopulations. All data are presented as median with interquartile range, with individual data points. P-values shown are from Mann-Whitney tests. Results also passed q < 0.05 thresholding based on the Benjamini-Hochberg test for multiple comparisons. n = 17 pwCF NEHi and n = 13 NELo, except for IL-8 (n = 16 NEHi and n = 11 NELo).

We also interrogated metabolites in sputum, again sub-setting for NEHi or NELo subjects within pwCF taking ETI (Fig. 3). Metabolomic data were available for 22 pwCF on ETI. NE activity was associated with 107 (out of 380 total) metabolites (Fig. 3A; Mann-Whitney p < 0.05 and q < 0.05), including amino acids, biogenic amines, phospholipids, nucleotides, and organic acids. All significant results are provided in Supplementary Table S2. Notably, the significant metabolites were consistently higher in NEHi. Pathway analysis of selected metabolites (55 successfully matching to KEGG pathways) revealed overrepresentation in five pathways (Fisher’s exact test p < 0.05, q < 0.05): purine metabolism; branched chain amino acid, arginine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan biosynthesis; nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism (Fig. 3B). We noted a clear module within purine metabolism connecting purines and their degradation products (Fig. 3C), as well as critical metabolites in arginine metabolism (Fig. 3D), and methionine oxidation by MPO (Fig. 3E). We also noted several metabolites consistent with proteolytic activity, including essential and N-acetylated amino acids, N N,N-trimethyllysine, and dipeptide glycylleucine (Fig. 3F). Overall, the metabolite results are consistent with broad neutrophil-driven pro-inflammatory metabolome disruption (reflected by higher proteolysis and oxidation) in the sputum supernatant of NEHi subjects.

Metabolomics reveals broad differences between NEHi and NELo subjects with strong evidence of higher neutrophilic involvement in NEHi subjects. (A) Heatmap of 107 metabolites selected by Mann-Whitney test controlled by Benjamini-Hochberg correction of p-values (p < 0.05, q < 0.05). Column (sample) and row (metabolite) data are clustered using Ward clustering with Euclidean distance, and columns are Z-scored. n = 12 NEHi and n = 10 NELo pwCF on ETI. (B) Pathway analysis of significant metabolites. Pathways that are p < 0.05 and q < 0.05 are named. (D-F) Significant metabolites selected from important pathways and/or associated with pathological processes are shown in grouped barplots. For all barplots, individual data points are shown over bars of median and interquartile ranges.

Worse lung function in the NEHi subset precedes the initiation of ETI therapy and is maintained thereafter

We sought to understand whether the NEHi subjects differed from NELo in demographics and overall disease (Table 2). Females were significantly underrepresented among NELo subjects (1/13, 7.7%; Fisher’s exact test p = 0.0174). However, age, race, duration of ETI use, prior HEMT use, CFTR genotype, insulin use, and BMI did not significantly differ between the two groups. All subjects in both groups were pancreatic enzyme insufficient. Although the overall frequency of sputum culture results did not significantly differ between NEHi and NELo pwCF, the NEHi group exhibited a trend toward higher prevalence of P. aeruginosa, while NELo subjects cultured Staphylococcus aureus more often than P. aeruginosa (Fisher’s exact test p = 0.0776; Table 2). Including those with polymicrobial infections, 10/16 total NEHi sputum specimens (62.5%) cultured P. aeruginosa, while only 4/13 (30.8%) of NELo did so (Fisher’s exact test p = 0.1394). Conversely, 6/16 (37.5%) of NEHi subjects cultured S. aureus, and 9/13 (69.2%) of NELo subjects did so (Fisher’s exact test p = 0.1394).

Lung function (ppFEV1) was significantly lower in NEHi compared to NELo subjects (Table 2; p = 0.0101).

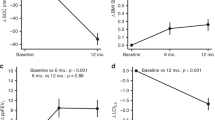

Retrospective analysis of ppFEV1 revealed that subjects classified as NEHi at the time of sputum sampling exhibited lower ppFEV1 values compared to NELo subjects for multiple years prior to ETI initiation (Fig. 4A; p = 0.0027 for NE activity subset effect by type III mixed effects model). While both groups showed improvements following ETI, the NEHi group’s ppFEV1 remained significantly lower than that of the NELo group across all measured post-ETI time points (Fig. 4A, p < 0.05 determined by Sidak’s multiple comparison test). However, by the third year post-ETI, the NEHi subjects gained lung function and overlapped to a greater extent with the NELo group. Most individuals in both groups showed similar improvements each year relative to the year of ETI initiation (Fig. 4B).

ppFEV1 is lower in NEHi donors prior to the start of ETI and remains low. (A) Retrospective analysis of lung function was conducted from the medical record of sputum donors. A type III mixed effects model indicated significant difference (indicated on the graph) and Sidak multiple comparison test also showed significant (adjusted p < 0.05) differences of the following time points relative to the year of ETI therapy start: −4, −1, 0, 1, 2, 3. Data are shown as median with interquartile range. The n per group are as follows (NELo followed by NEHi): Year − 5, n = 4 and n = 8; Years − 4 and − 3, n = 12 and n = 16; Year − 2, n = 13 and n = 16; Year − 1, n = 13 and n = 15; Year 0, n = 12 and n = 16; Year 1, n = 12 and n = 14; Year 2, n = 12 and n = 15; Year 3, n = 5 and n = 7. (B) Change in ppFEV1 after the year of ETI introduction was tested for up to 3 years following start of therapy. Data are shown as median with interquartile range. No significant differences were observed. The n per group are as follows (NELo followed by NEHi): Year 1, n = 11 and n = 14; Year 2, n = 11 and n = 15; Year 3, n = 5 and n = 7.

Discussion

In the current study, we analyzed neutrophil-derived proteins, immune mediators, and metabolites in sputum of clinically stable, adult pwCF within a single center. We observed minimal differences between subjects taking ETI and those using no HEMT. Besides ivacaftor and tezacaftor, the only significant difference in sputum (after controlling for multiple comparisons in cytokine and metabolite assays) was NE activity. However, this result was driven by a sub-population of individuals with low NE activity (NELo). When we compared the NEHi and NELo subpopulations among pwCF on ETI, we detected broad differences in soluble mediators of inflammation (MPO, cytokines, chemokines) and metabolites (including purines, proteolytic products, oxidized amino acids previously associated with neutrophils23. Retrospective analysis of pulmonary function also revealed lower lung function in the NEHi group that predated ETI initiation and persisted for multiple years after treatment initiation.

Neutrophilic inflammation is a major factor in the pathogenesis of CF24. We previously showed that neutrophils recruited to CF airways exhibit a phenotypic shift with overactive exocytosis of primary granules and metabolic reprogramming25,26,27. Exocytosis releases several effector proteins into the extracellular environment including NE, causing proteolysis of specific surface receptors28,29, and MPO, which generates strong halogenating oxidants that can irreversibly modify biological molecules18,21,30. NE and MPO activities and their byproducts are well-established biomarkers of CF disease severity that have been previously associated with CF lung structure and function, including in predictive roles18,31,32,33. CF lung inflammation is also associated with higher levels of neutrophil chemo-attractants like IL-8, TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-628[,34[,35. Previous work showed that ivacaftor has little impact on sputum inflammatory markers in less than a year and modest effects thereafter36,37. ETI has shown greater potential to decrease sputum inflammatory markers like NE and IL-1β over time, in some cases within weeks, albeit not below disease control levels7,8,9. ETI also affects systemic chemokine levels associated with neutrophilic inflammation including CXCL5, CXCL11, and IL-88, 38.

We observed the suppression of CXCL5, CXCL10, and CXCL11 in NEHi subjects, despite high levels of other pro-inflammatory markers like IL-8. While IL-8 is a powerful neutrophil chemoattractant, suppression of CXCL5 (another neutrophil chemoattractant) and the interferon-responsive T-cell chemokines CXCL10 and CXCL11 suggests a possible rewiring of the inflammatory response. In agreement with these results, Ford et al. also reported that immune cells recruited to the CF airway microenvironment express less CXCL1139. Our finding suggests altered or impaired inflammatory signaling in NEHi subjects which may contribute to worsened inflammation.

While our cross-sectional analysis did not reveal widespread differences in metabolites between ETI and NoHEMT groups (beyond expected ivacaftor and tezacaftor), a longitudinal study of CF sputum by Sosinski et al. demonstrated decreased leucine-, isoleucine-, valine- and phenylalanine-containing peptides and kynurenine pathway metabolites post-ETI therapy13. Notably, these are similar metabolites to those that differed in our study when comparing NEHi and NELo subjects (leucine, isoleucine, phenylalanine, tryptophan, and glycylleucine). Another study using home-collected sputum by Martin et al. also showed significant changes of the sputum metabolome after introduction of ETI, although trajectories were highly variable between individuals and no single metabolite consistently changed during the course of ETI therapy14. Overall, we observed stark metabolomic differences between NEHi and NELo subpopulations featuring metabolites related to neutrophil metabolic activities18,23,40,41, namely, purine degradation, proteolysis (essential and N-acetylated amino acids), arginine metabolism, and oxidized amino acids (products of methionine and cysteine oxidation). Additional studies should test whether these biomarkers are able to predict ETI responsiveness, for example methionine sulfoxide that reflects neutrophil exocytosis18,21.

We detected ivacaftor and tezacaftor in sputum, but not elexacaftor. Sosinski et al. did detect elexacaftor in post-ETI sputum, and also reported extensive metabolism of ivacaftor and tezacaftor in sputum detected via GNPS molecular networking13. Our annotation methods, which relied on in-house standards of ETI and MS/MS matching to online databases (but did not use molecular networking), did not detect these ETI metabolites. We believe the reason we did not detect parent elexacaftor in sputum of pwCF taking ETI is likely related to poor retention of the hydrophobic modulator in our hydrophilic molecule-retaining LC method, which in combination with overall low elexacaftor concentrations may have led to ion suppression.

Lung function in pwCF has overall improved, from 74.6% in 2007 to 85% in 2022, mostly due to the introduction of modulator therapy42. When looking at the trajectory of pulmonary function among the adults with CF in our study, the ppFEV1 did generally improve in the years after starting ETI therapy. NEHi subjects ranged from moderate (ppFEV1 40% to 69%) to mild (ppFEV1 70% to 89%) lung disease, while NELo pwCF tended to be in the mild to normal (ppFEV1 ≥ 90%) categories. Treatment with ETI did not negate this difference, although the gap narrowed by the third year post-therapy. These data suggest initiating ETI with worse inflammatory burden might limit the extent of improvement, but it is important to note that all individuals gained lung function after ETI initiation. Schütz et al. reported that CF children with more severe lung disease prior to ETI showed more improvement in lung function than CF adults with severe lung disease, suggesting that clinical response might depend on age of ETI initiation43. Gill et al. reported decreased respiratory symptom severity over two years in pwCF with advanced disease taking ETI compared to those who were not, but also noted that respiratory symptoms persisted in pwCF with advanced lung disease44. Understanding the influence of inflammatory burden on ETI (and other HEMT) efficacy will be key to advance CF care going forward.

A striking demographic finding in our study was the significant overrepresentation of females in the NEHi group (52.9%) compared to the NELo group (7.7%). Females with CF experience a more rapid decline in pulmonary function and worse outcomes, including after pulmonary exacerbations, compared to males45,46. Our cross-sectional results support the potential for higher female prevalence of persistent neutrophilic inflammation after ETI initiation. The basis for sex differences in CF lung disease appears to be multicausal47, and should be a key factor in future studies evaluating the stratification of pwCF responses to therapy.

Our study has several limitations. First, the relatively small number of NoHEMT control samples reduced the statistical power to detect differences from ETI in this cross-sectional comparison. The variability within the NoHEMT group, including a potential bimodal distribution, suggests potential for a likely NELo subpopulation therein, which may have been detected with a larger sample. Another important consideration in the ETI era is the potential for selection bias. HEMT including ETI reduce or even cease sputum production in many pwCF7. Therefore, our cohort may represent a subgroup of ETI-taking pwCF with more severe or persistent airways disease. Another limitation is the lack of comparison to baseline (pre-ETI) sputum, without which we cannot definitively ascertain whether the NEHi and NELo subsets also existed prior to ETI initiation. However, our retrospective lung function analysis suggests this was likely the case, particularly in light of a prior study connecting high sputum proteolytic activity and decreased lung function12. Finally, we had access to a limited volume of sputum, which left insufficient material for all assays to be completed for all subjects (e.g., several samples were unavailable for metabolomics).

Since the introduction of ETI, many pwCF have seen improvement in clinical outcomes and life expectancy. However, modulator therapy is not available to all pwCF, highlighting the need for additional therapies48,49,50. Additionally, inflammation remains high in modulator-treated pwCF with established lung disease25,51. Our findings suggest that pwCF on ETI who have higher neutrophilic inflammation also have worse pulmonary function that is not rescued to low inflammation levels by ETI. This is concordant with the finding that higher sputum neutrophil inflammation and proteolytic activity associate with decreased lung function, a more amino acid-rich environment, and higher P. aeruginosa burden12. Identifying NEHi pwCF and providing adjunctive therapies targeting inflammation, P. aeruginosa, and related factors may be key to equalizing the benefits of ETI among eligible pwCF. Our study also highlights the potential benefit for adjunctive neutrophil-targeting therapy for pwCF with remaining significant amounts of NE activity after introduction to ETI therapy.

Data availability

Data supporting the conclusions of this article are provided in the manuscript or as supplementary material associated with it. Supplementary Table S3 identifies which subjects contributed to which assays.

Abbreviations

- CF:

-

Cystic fibrosis

- CFTR:

-

CF transmembrane conductance regulator channel

- ETI:

-

Elexacaftor-tezacaftor-ivacaftor

- HEMT:

-

Highly effective modulator therapy

- MPO:

-

Myeloperoxidase

- NE:

-

Neutrophil elastase

- pwCF:

-

People with CF

- ppFEV1:

-

percent predicted forced expiratory volume in one second

References

Ong, T. & Ramsey, B. Cystic Fibrosis: A Review. JAMA 329(21), https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.8120 (2023).

Grasemann, H. & Ratjen, F. Cystic fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 389 (18). https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra2216474 (2023).

Burgel, P. et al. Rapid Improvement after Starting Elexacaftor-Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis and Advanced Pulmonary Disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med. 204(1), https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202011-4153OC (2021).

Jia, S. & Taylor-Cousar, J. Cystic fibrosis modulator therapies. Annu. Rev. Med. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-med-042921-021447 (2022).

Tiotiu, A., Ioan, I. & Billon, Y. Effects of elexacaftor-tezacaftor-ivacaftor on daily treatment burden and airflow obstruction in adults with cystic fibrosis. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pupt.2023.102248 (2023).

Donaldson, S. et al. Effect of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor on mucus and mucociliary clearance in cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibrosis: Official J. Eur. Cyst. Fibros. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcf.2023.10.010 (2023).

Casey, M. et al. Effect of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor on airway and systemic inflammation in cystic fibrosis. Thorax 78 (8), https://doi.org/10.1136/thorax-2022-219943 (2023).

Schaupp, L. et al. Longitudinal effects of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor on sputum viscoelastic properties, airway infection and inflammation in patients with cystic fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 62 (2), https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.02153-2022 (2023).

Lepissier, A. et al. Moving the dial on airway inflammation in response to Trikafta in adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med. 207 (6). https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202210-1938LE (2023).

Vuyst, R. D., Bennard, E., Kam, C., McKinzie, C. & Esther, C. Elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor treatment reduces airway inflammation in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 58 (5). https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.26334 (2023).

Sheikh, S. et al. Impact of elexacaftor-tezacaftor-ivacaftor on bacterial colonization and inflammatory responses in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 58(3), https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.26261 (2023).

Quinn, R. et al. Neutrophilic proteolysis in the cystic fibrosis lung correlates with a pathogenic microbiome. Microbiome 7(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-019-0636-3 (2019).

Sosinski, L. et al. A restructuring of Microbiome niche space is associated with Elexacaftor-Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor therapy in the cystic fibrosis lung. J. Cyst. Fibrosis: Official J. Eur. Cyst. Fibros. Soc. 21 (6). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcf.2021.11.003 (2022).

Martin, C. et al. Longitudinal microbial and molecular dynamics in the cystic fibrosis lung after Elexacaftor-Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor therapy. Res. Square. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3356170/v1 (2023).

Cooper, B. et al. The global lung function initiative (GLI) network: bringing the world’s respiratory reference values together. Breathe (Sheff). 13 (3), e56–e64. https://doi.org/10.1183/20734735.012717 (2017). From NLM.

Forrest, O. et al. Frontline science: pathological conditioning of human neutrophils recruited to the airway milieu in cystic fibrosis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 104 (4). https://doi.org/10.1002/JLB.5HI1117-454RR (2018).

Dittrich, A. et al. Elastase activity on sputum neutrophils correlates with severity of lung disease in cystic fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01910-2017 (2018).

Chandler, J. et al. Myeloperoxidase oxidation of methionine associates with early cystic fibrosis lung disease. Eur. Respir. J. 52 (4). https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01118-2018 (2018).

Chapman, A. et al. Ceruloplasmin is an endogenous inhibitor of myeloperoxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 288 (9), 6465–6477. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M112.418970 (2013). From NLM.

Giacalone, V. et al. Pilot study of inflammatory biomarkers in matched induced sputum and Bronchoalveolar lavage of 2-year-olds with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 57 (9). https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.26023 (2022).

Kim, S. et al. Substrate-dependent metabolomic signatures of myeloperoxidase activity in airway epithelial cells: implications for early cystic fibrosis lung disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 206 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2023.06.021 (2023).

Pang, Z. et al. MetaboAnalyst 5.0: narrowing the gap between Raw spectra and functional insights. Nucleic Acids Res. 49 (W1), W388–w396. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab382 (2021). From NLM.

Chandler, J. & Esther, C. Metabolomics of airways disease in cystic fibrosis. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 65 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coph.2022.102238 (2022).

Giacalone, V., Dobosh, B., Gaggar, A., Tirouvanziam, R. & Margaroli, C. Immunomodulation in cystic fibrosis: why and how? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21 (9). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21093331 (2020).

Margaroli, C. & Tirouvanziam, R. Neutrophil plasticity enables the development of pathological microenvironments: implications for cystic fibrosis airway disease. Mol. Cell. Pediatr. 3 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40348-016-0066-2 (2016).

Tirouvanziam, R. et al. Profound functional and signaling changes in viable inflammatory neutrophils homing to cystic fibrosis airways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105(11), https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0712386105 (2008).

Laval, J., Ralhan, A. & Hartl, D. Neutrophils in cystic fibrosis. Biol. Chem. 397(6), https://doi.org/10.1515/hsz-2015-0271 (2016).

Bruce, M. et al. Biochemical and pathologic evidence for proteolytic destruction of lung connective tissue in cystic fibrosis. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 132(3), https://doi.org/10.1164/arrd.1985.132.3.529 (1985).

Genschmer, K. et al. Activated PMN exosomes: pathogenic entities causing matrix destruction and disease in the lung. Cell 176 (1–2), 113–126e115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.002 (2019). From NLM.

Dalen, C. V., Whitehouse, M., Winterbourn, C. & Kettle, A. Thiocyanate and chloride as competing substrates for myeloperoxidase. Biochem. J. 327 (Pt(2), https://doi.org/10.1042/bj3270487 (1997).

Mayer-Hamblett, N. et al. Association between pulmonary function and sputum biomarkers in cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med. 175 (8). https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200609-1354OC (2007).

Dickerhof, N. et al. Oxidative stress in early cystic fibrosis lung disease is exacerbated by airway glutathione deficiency. Free Radic Biol. Med. 113, 236–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.09.028 (2017). From NLM.

Dickerhof, N. et al. Oxidized glutathione and uric acid as biomarkers of early cystic fibrosis lung disease. J. Cyst. Fibros. 16 (2), 214–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcf.2016.10.012 (2017). From NLM.

Lepissier, A. et al. Inflammation biomarkers in sputum for clinical trials in cystic fibrosis: current Understanding and gaps in knowledge. J. Cyst. Fibrosis: Official J. Eur. Cyst. Fibros. Soc. 21 (4). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcf.2021.10.009 (2022).

Gars, M. L. et al. Neutrophil elastase degrades cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator via calpains and disables channel function in vitro and in vivo. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med. 187 (2). https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201205-0875OC (2013).

Harris, J. et al. Changes in airway Microbiome and inflammation with Ivacaftor treatment in patients with cystic fibrosis and the G551D mutation. Annals Am. Thorac. Soc. 17 (2). https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201907-493OC (2020).

Hisert, K. et al. Restoring cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator function reduces airway bacteria and inflammation in people with cystic fibrosis and chronic lung infections. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med. 195 (12). https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201609-1954OC (2017).

Westhölter, D. et al. Plasma levels of chemokines decrease during elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor therapy in adults with cystic fibrosis. Heliyon 10 (1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e23428 (2023).

Ford, B. et al. Functional and transcriptional adaptations of blood monocytes recruited to the cystic fibrosis airway microenvironment in vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (5). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22052530 (2021).

Esther, C. J. et al. Metabolomic evaluation of neutrophilic airway inflammation in cystic fibrosis. Chest 148 (2), 507–515. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.14-1800 (2015). From NLM.

Ingersoll, S. et al. Mature cystic fibrosis airway neutrophils suppress T cell function: evidence for a role of arginase 1 but not programmed death-ligand 1. J. Immunol. (Baltimore Md. : 1950) 194(11), https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1500312 (2015).

Foundation, C. F. Patient registry; (2022).

Schütz, K. et al. Spirometric and anthropometric improvements in response to elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor depending on age and lung disease severity. Front. Pharmacol. 14 https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2023.1171544 (2023).

Gill, E. et al. A longitudinal analysis of respiratory symptoms in people with cystic fibrosis with advanced lung disease on and off ETI. J. Cyst. Fibrosis: Official J. Eur. Cyst. Fibros. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcf.2023.11.008 (2023).

Wang, A. et al. Sex differences in outcomes of people with cystic fibrosis treated with elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor. J. Cyst. Fibrosis: Official J. Eur. Cyst. Fibros. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcf.2023.05.009 (2023).

Kerem, E. et al. Factors associated with FEV1 decline in cystic fibrosis: analysis of the ECFS patient registry. Eur. Respir. J. 43 (1). https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00166412 (2014).

Silveyra, P., Fuentes, N. & Bauza, D. R. Sex and gender differences in lung disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1304, 227–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-68748-9_14 (2021). From NLM.

Hisert, K. et al. Understanding and addressing the needs of people with cystic fibrosis in the era of CFTR modulator therapy. Lancet Respiratory Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(23)00324-7 (2023).

Desai, M. et al. Who are the 10%? - Non eligibility of cystic fibrosis (CF) patients for highly effective modulator therapies. Respir. Med. 199, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2022.106878 (2022).

Ensinck, M. & Carlon, M. One Size Does Not Fit All: The Past, Present and Future of Cystic Fibrosis Causal Therapies. Cells 11(12), https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11121868 (2022).

Margaroli, C. et al. Transcriptional firing represses bactericidal activity in cystic fibrosis airway neutrophils. Cell. Rep. Med. 2(4), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100239 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank PwCF and their families who participated in the research program. We also thank the CF Biospecimen Registry at the Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta and the Emory University CF Discovery Core, in particular Dr. Arlene A. Stecenko and Chris Driggers.

Funding

NIH (R01 HL150658, R01 HL159058), CFF (CAMMAR21F0, TIROUV19A0, TIROUV22G0-CFRD), I3 Teams Research Award (Emory) and CF@LANTA, a component of Emory University and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. Supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR002378.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ACM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing. DMG: Formal analysis, Data curation, Software, Writing. GLC: Investigation, Data curation. SOK, SM: Formal analysis, Software. VDG, MMP: Investigation. KAC: Formal analysis. RT, JDC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing, Resources, Supervision. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cammarata-Mouchtouris, A., Giraldo, D.M., Collins, G.L. et al. People with cystic fibrosis with high sputum neutrophil elastase on elexacaftor-tezacaftor-ivacaftor exhibit worse pulmonary function and pro-inflammatory airway milieu. Sci Rep 15, 43430 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26263-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26263-y