Abstract

The present study aims to investigate the optical and structural characteristics of CuMn2O4GO and CuMn2O4GOFe3O4 nanocomposites in comparison to CuMn2O4 nanoparticles, with the goal of exploring linear, nonlinear, and photonic applications. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis determined the crystallite sizes for CuMn2O4, CuMn2O4GO, and CuMn2O4GOFe3O4 samples synthesized by the co-precipitation method to be 16.31, 4.76, and 11.86 nm, respectively. SEM images demonstrate that the particles were generally well-dispersed and mostly spherical to hexagonal in shape. By analyzing the reflectance data through the Tauc model, the direct band gap energies were found to be 2.06 eV, 2.08 eV, and 2.18 eV for CuMn2O4, CuMn2O4GO, and CuMn2O4GOFe3O4 samples, respectively. To examine the NLO properties of the nanopowders, the Z-scan method was utilized with a 532 nm Nd: YAG laser at incident powers of \(P_{0}\) = 20, 25, and 30 mW. The nonlinear absorption coefficient and refractive index determined by the Z-scan method were approximately (103) and (109), respectively. At \(P_{0}\) = 30 mW, for CuMn2O4, CuMn2O4GO, and CuMn2O4GOFe3O4, the NLR and NLA reverse saturable absorption reactions are observed at 3.04 × 10−9, 3.98 × 10−9, and 10.3 × 10−9 m2/W, and 8.6 × 10−3, 6.4 × 10−3, and 5 × 10−3 m/W, respectively. The exceptional nonlinear optical (NLO) coefficients of the prepared nanopowders emphasize their potential for creating ultrafast lasers, anti-laser optical limiters, and two-photon microscopy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The emergence of nanotechnology has stimulated significant interest in nanoparticles and nanocomposites due to their distinctive characteristics[1, 2]. Multi-oxide nanoparticles, such as CuMn2O4, are of particular interest for applications in catalysis, energy storage, and sensing, owing to their electrical and catalytic properties[3]. Integrating CuMn2O4 with graphene oxide (GO) and magnetic nanoparticles like \({\text{Fe}}_{3} {\text{O}}_{4}\) can further augment optical and electrical functionalities, facilitating novel applications[4]. The development and thorough investigation of CuMn2O4GO and CuMn2O4GOFe3O4 nanocomposites represent a novel strategy for advancing the understanding of their physical properties and potential application domains[5, 6]. Among the synthesis techniques, the co-precipitation method[7] is recognized for its simplicity and efficiency in producing nanoparticles with high purity and controlled dimensions. Comprehensive structural and optical characterizations of these nanocomposites were carried out using advanced analytical tools, including FTIR, XRD, EDAX, SEM, and DRS[8, 9]. Anhessari et al.[10] investigated the physicochemical properties and synthesis of CuMn2O4 nanoparticles, identifying them as promising semiconductors for optoelectronic applications. The results of their exploration showed that CuMn2O4possesses favorable structural integrity and electrical attributes, supporting its use in photoelectric and photoluminescent devices. With an average particle diameter of around 39 nm and a band gap of 1.4 eV, these nanoparticles are considered well-suited for integration into modern technology. In another study, Fang et al.[11] provided both experimental observations and theoretical analysis on the behavior of spinel-structured Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\) during chemical looping combustion with CO. Their findings suggested that Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\) undergoes reduction to copper and MnO more efficiently than \({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{3}\), primarily because of the catalytic role of copper. Density functional theory (DFT) computations further supported these outcomes, showing that the exothermic process is predominantly diffusion-controlled, with activation energies of 64.59 kJ/mol on the Mn surface and 58.83 kJ/mol on the Cu surface for CO oxidation. Additionally, Saravanakumara et al.[12] have studied the electrochemical performance of Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\) nanoparticles that are synthesized under hydrothermal conditions at 160 °C, revealing a brass-like microstructure and morphology. XRD patterns showed excellent alignment with standard data, and FTIR confirmed the existence of Mn–O and Cu–O bonds. These nanoparticles exhibited impressive specific capacitances of 520.4 F/g and 577.9 F/g under different testing scenarios, highlighting their utility in supercapacitor devices. Abel et al.[13] investigated Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\) nano sheets synthesized via co-precipitation for photocatalytic applications. PXRD results confirmed a spinel FCC structure, and UV–Vis DRS spectra showed a band gap of 2.54 eV. FTIR analysis validated metal–oxygen bonds, while particle size measurements fell within the range of 50–100 nm. The EDAX spectrum confirmed the chemical purity of the samples. Moreover, these nanoparticles exhibited remarkable photocatalytic activity in degrading organic dyes such as methylene blue and malachite green under sunlight, achieving efficiencies of 86% and 92%, respectively. In this research, the morphological and crystallographic properties of Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\) nanoparticles, incorporated with graphene oxide (GO) and \({\text{Fe}}_{3} {\text{O}}_{4}\) were explored to systematically assess their impact on a range of optical parameters. The synthesized sample’s particle size and crystal structure were determined via XRD pattern analysis. Furthermore, the optical behavior of the nanoparticles was examined using DRS analysis, in combination with the Kubelka–Munk model and the Kramers–Kronig transformation approach[14, 15]. Key optical constants like refractive index, Urbach energy, optical band gap, and linear absorption coefficients were calculated. A comparative evaluation was then carried out to examine how the integration of GO and \({\text{Fe}}_{3} {\text{O}}_{{4{ }}}\) alters the optical and structural attributes of Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\). The literature review shows a lack of comprehensive comparative studies using z-scan to analyze the NLO (nonlinear optical) characteristics of Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\), Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO, and Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO\({\text{Fe}}_{3} {\text{O}}_{{4{ }}}\) nanocomposites. Moreover, specific research on the nonlinear optical properties of these nanocomposites appears to lacking. Therefore, this study represents the first investigation of the nonlinear optical properties of these nanocomposites using the z-scan technique. The simplicity of the co-precipitation method made it the ideal choice for creating Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\), Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO, and Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO\({\text{Fe}}_{3} {\text{O}}_{{4{ }}}\) samples in this metal oxide study, where accurate preparation is key. This study builds upon prior research on Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)-based materials using z-scan technology for getting data. Analyzing the CA (closed-aperture) of z-scan data determined the sign and magnitude of the third-order nonlinearity; open-aperture (OA) measurements showed a useful inverse saturable absorption (RSA) coefficient in the synthesized samples. This study offers a comprehensive analysis of the nonlinear optical (NLO) properties of nanocomposites, using z-scan data for precise linear susceptibility computations. The size of nanoparticles influences the band gap energy (\(E_{g}\)), thereby affecting linear optical properties such as the absorption coefficient (α). Additionally, structural defects, along with europium (\(E_{u}\)), may affect the nonlinear absorption coefficient β’s size. In addition, the Z-scan procedure allows the calculation of \(n_{2}\), β, and \(\chi^{\left( 3 \right)}\)[16, 17].

Details of the experiment

Synthetic method

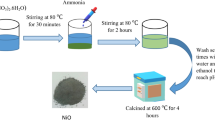

The synthesis of the samples was carried out using the co-precipitation technique. Initially, to prepare Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\) nanoparticles, 0.49 g of copper nitrate was dissolved in 10 mL of deionized water. Separately, 1.22 g of manganese nitrate was dissolved in another 10 ml of water. So that the volume of the two solutions mixed reaches 50 ml. The pH of the solution was regulated to approximately 8 using 2 M sodium carbonate. The resulting mixture was continuously stirred and heated at 80 °C for three h. After the reaction was complete, the resulting precipitate was filtered and thoroughly washed, followed by drying in a 70 °C oven for 24 h. The dried powder was subsequently calcined at 450 °C in a porcelain crucible for two hours. For the synthesis of Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO nanocomposites, a similar procedure was followed, with the addition of graphene oxide. Specifically, 0.1 g of pre-synthesized GO was dispersed in 10 ml of water using ultrasonic agitation for 20 min. This dispersion was then introduced into the copper and manganese solution before following the same precipitation and calcination steps as described above. To get the Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO\({\text{Fe}}_{3} {\text{O}}_{{4{ }}}\) sample, 0.8 g of \({\text{FeCl}}_{3}\) was incorporated into the reaction mixture along with the 0.49 g of copper precursor. The synthesis procedure was then carried out as previously outlined. Ultimately, three distinct samples were produced—Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\), Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO, and Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO\({\text{Fe}}_{3} {\text{O}}_{{4{ }}}\)—each synthesized under identical thermal treatment and experimental conditions, but with compositional differences leading to varied physicochemical properties. Details about the names of the materials and how they were synthesized are given in Table 1.

Characterization

A range of analytical methods, such as XRD, SEM, EDAX, DRS, and FTIR, were used to fully characterize the synthesized nanomaterials. Structural features were examined using Bruker Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) in an X-ray diffractometer to collect data between 20° and 70° 2θ. Surface morphology was investigated using SEM, providing insight into particle shape and distribution. The optical characteristics of the nanoparticles were analyzed using DRS to assess their linear optical behavior. FTIR measurements were conducted to identify functional groups and chemical bonding within the different phases. Elemental analysis was performed using EDAX, enabling the determination of the elemental composition and relative abundance of constituents in each sample. Altogether, these characterization methods facilitated an in-depth evaluation of the structural, morphological, compositional, and optical properties of the synthesized nanoparticle systems.

Findings and discussion

Analysis of the structure

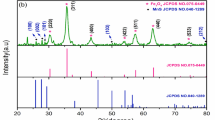

The synthesized samples’ crystalline structures were determined by XRD, using Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) at room temperature. The analysis of structural parameters was carried out using the X’Pert Highscore Plus software from PANalytical. The resulting diffraction patterns corresponding to the three prepared nanocomposite samples are presented in Fig. 1, while the specific 2θ peak positions are summarized in Table 2.

As illustrated in Fig. 1a, the XRD pattern of Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\) reveals distinct diffraction peaks at 2θ values of 29.510°, 33.242°, 35.009°, and 52.62°, which correspond to the (200), (103), (211), and (312) crystallographic planes, respectively. These peaks match well with the reference data from JCPDS Card No. 00-045-0505, confirming a tetragonal crystal structure with a space group of I41/amd. Additionally, minor secondary phases of Mn \({\text{O}}_{2}\) and CuO were identified, as indexed by JCPDS Cards 00-012-0716 and 03-065-2309, and listed in Table 3. Figure 1b shows the diffraction pattern of the CuMn2O4GO composite. This pattern maintains the tetragonal symmetry, but features an additional low-intensity peak at 2θ = 11.54°, indexed to the (002) plane of graphene oxide under JCPDS Card No. 01-075-1621. This signal is attributed to the partial reduction and dispersion of GO, which is known for its inherently low crystallinity. Because of the lack of strong crystalline order in GO, no significant chemical bonding is expected between it and the spinel CuMn2O4 phase[18]. Moreover, slight shifts in the main CuMn2O4 peaks in the GO composite (as detailed in Table 2) further suggest the incorporation of GO into the crystal lattice or its interaction at the structural level. In Fig. 1c, the diffraction pattern of the Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO\({\text{Fe}}_{3} {\text{O}}_{{4{ }}}\) nanocomposite exhibits characteristic peaks corresponding to \({\text{Cu}}_{{{1}{\text{.5}}}} {\text{Mn}}_{{{1}{\text{.5}}}} {\text{O}}_{4}\), \({\text{Fe}}_{3} {\text{O}}_{4}\), and GO phases, confirming all components. The diffraction signals align with reference data from relevant JCPDS cards listed in Table 3. The dominant structure in this sample is cubic, consistent with the Fd-3 m space group. Additional peaks from minor secondary phases are also clear in the pattern. It should be noted that due to the significant contribution of amorphous GO and the overlap between \({\text{Fe}}_{3} {\text{O}}_{{4{ }}}\) and CuO diffraction peaks, Rietveld refinement could not be reliably performed. Therefore, phase identification was carried out qualitatively from XRD patterns and further supported by EDAX elemental analysis.

Debye–Scherer method

Using the Debye-Scherer equation, Modified Debye–Scherer method and the Williamson-Hall method, the average crystallite size (⟨D⟩) of the synthesized samples was estimated, with the calculated values summarized in Table 4. These estimations were based on the following standard formulas[19,20,21,22]:

here crystallite size is D, shape factor (k) is 0.9, incident X-ray wavelength is λ, FWHM is β, strain is ε, and Bragg diffraction angle is θ. To accurately calculate the size of crystallites in samples, it is necessary to subtract the effect of the broadening caused by the device from the measured broadening. The following equation shows the corrected broadening[22]:

In the equation utilized βᵢ denotes the broadening caused by the device, βₒ represents the experimentally measured broadening, and \(\beta_{d}\) which is used to estimate crystallite size, represents the amount of modified broadening. For accurate peak width correction, the broadening value of crystalline silicon was used as a standard reference[22]. Table 4 shows that pure Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\) had an average crystallite size of about 55.8 nm, as determined using the Debye–Scherer equation. This size significantly decreased to 14.6 nm upon incorporation of graphene oxide, forming the Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO nanocomposite. However, when \({\text{Fe}}_{3} {\text{O}}_{{4{ }}}\) was further introduced, resulting in Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO\({\text{Fe}}_{3} {\text{O}}_{{4{ }}}\), the average crystallite size increased again to about 58.5 nm.

Modified Debye–Scherer (Monshi–Scherer) method

The Modified Debye–Scherer method to estimate a more precise value of nanocrystalline size was expressed as follow equation[23]:

The average crystallite size amount is calculated by plotting Ln β (radians) against Ln(1/Cosθ) as y = ax + b equation as depict in Fig. 2. In detail, Fig. 2a illustrates the results for sample Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\), Fig. 2b for Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO, and Fig. 2c for Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO\({\text{Fe}}_{3} {\text{O}}_{{4{ }}}\). The fixed L value, which represents the crystallite size, is determined by the following equation:

Figure 2 shows the modified Debye-Scherer diagrams of the samples.

Williamson–Hall method

Figure 3 presents the Williamson–Hall analysis, where linear fitting was performed using Origin software to extract both the microstrain (ε) and crystallite size (D) values, which are listed in Table 4. Based on this method, the crystallite size for Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\) was estimated at 16.31 nm (Fig. 3a), which decreased to 4.76 nm in the GO-modified sample (Fig. 3b). Interestingly, the crystallite size in the Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO\({\text{Fe}}_{3} {\text{O}}_{{4{ }}}\) composite was measured at 11.86 nm (Fig. 3c), showing a reduction compared to the unmodified Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\) nanopowder. When comparing the estimation techniques, the Williamson–Hall method is considered more accurate, as it accounts for strain and multiple diffraction peaks. The results indicate that the incorporation of GO and \({\text{Fe}}_{3} {\text{O}}_{{4{ }}}\) generally leads to a reduction in crystallite size. Furthermore, all calculated strain values were negative, as shown in Table 4, suggesting that the synthesized samples experienced compressive strain during formation[23].

Morphological analysis

SEM (Scanning Electron Microscopy) is critical in evaluating the morphological characteristics of nanomaterials, offering the significant advantage of generating detailed three-dimensional surface images of the samples[18]. The SEM micrographs of the synthesized nanoparticles are presented in Fig. 4a–c. These images demonstrate that the particles are generally well-dispersed and exhibit predominantly spherical to hexagonal shapes. Furthermore, the SEM observations align in good agreement with the XRD results, confirming the consistency of the structural data. Notably, due to the presence of surface roughness and porosity, the particle sizes determined by SEM often differ from those obtained through XRD measurements. This difference is attributed to the fact that SEM provides insight into the external morphology and surface topology, whereas XRD calculates average crystallite dimensions based on the broadening of diffraction peak. As parameters such as particle size, shape, structural geometry, and spatial distribution significantly influence the optical behavior of nanoparticles, understanding these morphological details is essential. Consequently, the optical properties discussed in the subsequent sections are closely linked to these structural and morphological features.

The histogram plots of the samples is shown in Fig. 5. The particle size distribution of the synthesized \({\text{CuMn}}_{{2}} {\text{O}}_{{4}}\) nanocomposite in Fig. 5a shows an average particle size of 0.5 μm with a standard deviation of 0.06 μm (500 ± 60 nm), indicating a relatively narrow size distribution. Also, the histogram of Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO in Fig. 5b shows an average particle size of 0.15 μm with a standard deviation of 0.04 μm (150 ± 40 nm), and Fig. 5c shows the histogram of Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO\({\text{Fe}}_{3} {\text{O}}_{{4{ }}}\), showing an average particle size and standard deviation of 0.6 μm and 0.1 μm (600 ± 100 nm), respectively. The graphs, show particle diameter changes as measured by SEM, consistent with XRD data. SEM provides a slightly larger crystallite size compared to XRD. The observed difference could be connected to the surface structure of combined grains, resulting in the formation of big grains with pores and rough surfaces[24]. Because a nanoparticle system’s characteristics are affected by key factors such as size, form, and structure, along with their distribution, unique optical properties arise, which have potential use in novel materials[25]. Consequently, the linear and non-linear optical properties will be studied based on the nanoparticles’ structure and morphology.

EDAX analysis

The structural characteristics and elemental composition of the samples are examined using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDAX). The EDAX spectra for the samples are presented in Fig. 6a–c. The patterns for CuMn2O4 (Fig. 6a) clearly verify the presence of Cu, Mn, and O at their standard energy levels. Similarly, the spectra for other samples (Fig. 6b, c) confirm that the target elements are detected at their expected energy values[12]. EDAX spectra confirm the presence of C in CuGO and CuGOFe3O4 samples, attributable to GO, with atomic percentages of ~ 2–5 at%, indicating successful incorporation without significant impurities.

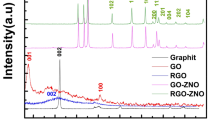

FTIR study

Figure 7a–c presents the FTIR analysis of the synthesized samples, conducted within the 400–4000 cm−1 range to investigate the structural composition and functional groups of the nanocomposites[26,27,28,29]. Variations in vibrational frequencies are observed, attributed to differences in ionic and bond radii[30]. In Fig. 7a, the spectrum of FTIR of Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\) reveals a distinct peak at 1120 cm−1, corresponding to O–H stretching vibrations, alongside two peaks at 470 cm−1 and 628 cm−1, associated with Mn–O and Cu–O bonds, respectively. Figure 7b displays the spectrum of graphene oxide (GO), with peaks at 1448 cm−1 and 1629 cm−1 linked to C=C and carboxyl C=O bonds, respectively. Additionally, a peak at 2923 cm−1 corresponds to C–H bonds, and a broad peak at 3433 cm−1 is attributed to O–H bond vibrations. Figure 7c shows the FTIR spectrum of the Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO\({\text{Fe}}_{3} {\text{O}}_{{4{ }}}\) sample. The peak recorded at 3436 cm−1 is related to the O–H stretching vibration and the peaks at 2922 cm−1 and 2853 cm−1 are related to the asymmetric and symmetric C-H vibrations of the graphene structure, respectively. The stretching vibration of the carbonyl group is observed in the range of 1720–1740 cm−1 and the C=C vibration is observed at 1627 cm−1. The bending vibration of the hydroxy group due to the absorbed moisture is observed at 1461 cm−1 and the C–O stretching vibration related to the GO component is observed at 1380 cm−1 and 1097 cm−1. Considering that the vibrational peak related to oxygen-metal is observed in the range of 400–830 cm−1, the vibrations at 470 cm−1, 588 cm−1, and 801 cm−1 are related to the vibrations of Fe–O, Mn–O, and Cu–O. Figure 7d illustrates the FTIR spectra of the samples across the 400–4000 cm−1 range. The presence of impurities influences the FTIR peak intensities, with the base material (Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)) exhibiting stronger peaks compared to other samples. Table 5 summarizes key IR peaks and their corresponding assignments[11,12,13,14,15].

Linear optical characteristics

Reflectance

Diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS), a key method for evaluating the optical properties of materials, especially nanocomposites, was utilized to measure the reflectance spectra of the synthesized samples across the 350–800 nm wavelength range, as depicted in Fig. 8. The findings indicate that the Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO sample demonstrates the highest reflectance percentage. Conversely, the reflectance is lower in the Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO\({\text{Fe}}_{3} {\text{O}}_{{4{ }}}\) and Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\) samples, respectively. Furthermore, the addition of GO and GO\({\text{Fe}}_{3} {\text{O}}_{{4{ }}}\) to the base material shifts the edge wavelength (\(\lambda_{edge}\)) toward shorter wavelengths, exhibiting a rise in the \(E_{g }\) of the samples[10,11,12,13,14,15].

Tauc plot of Kubelka–Munk function

The Kubelka–Munk method is widely utilized to interpret diffuse reflectance spectra, particularly in the visible range and for semiconductor materials. By employing diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS) data, the reflectance spectrum can be converted into an equivalent absorption spectrum using the Kubelka–Munk function. This function, represented as F(R), is expressed by the equation provided in reference[30].

Which can ultimately be written as \({\text{ F}}\left( {\text{R}} \right) = \frac{{\left( {{\text{h}}\upnu - {\text{E}}_{{\text{g}}} } \right)^{{1/{\text{n}}}} }}{{{\text{h}}\upnu }}\). In the given equation, h denotes Planck’s constant, while the absorption and scattering coefficients are expressed by K and S, respectively. In semiconductor materials, optical transitions occur through both direct and indirect mechanisms. The optical band tail can be evaluated from the absorption spectrum; this means electrons are excited from the valence band into the conduction band. Applying the Tauc method, the absorption coefficients of the samples are analyzed to determine the direct band gap energy, calculated using the equation referenced in[31].

In this context, hν represents the energy of incident photons, and A is a constant specific to the material. The absorption coefficient is denoted by α, while \(E_{g }\) signifies the material’s band gap energy. Experimentally determined exponent n reveals the kind of electronic transitions involved in light absorption. Typically, direct transitions have values of 2, and indirect transitions have values of 1/2[32]. Figure 9 illustrates the direct band gap energy (\(E_{g }\)) of the synthesized nanoparticles, calculated using the Tauc method by plotting (αhν)2 against photon energy (hν). The linear segment of each curve is extrapolated to intersect the energy axis, where (αhν)2 = 0, providing the estimated \(E_{g }\)[33]. Table 6 shows the values of the band gap energy for the synthesized nanoparticles. According to the optical absorption spectra in Fig. 9, the direct band gap energies for Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\), Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO, and Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO\({\text{Fe}}_{3} {\text{O}}_{{4{ }}}\) nanoparticles are 1.77 eV, 1.83 eV, and 1.93 eV, respectively. This increase in \(E_{g }\) is attributed to the reduced particle size in the nanocomposites[34]. These results are consistent with the trends observed in the absorption spectra and their corresponding absorption coefficient values[35]. Consequently, Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\) nanoparticles demonstrate semiconductor properties, making them promising candidates for photoelectric device applications[36].

Urbach energy

Structural parameters like dislocation density lead to localized defect states, which form the Urbach tail, expanding the absorption edge to cover the forbidden energy gap. Urbach energy (\(E_{u }\)) measures the absorption tail’s width, showing the material’s disordered nature and localized states close to the band gap. In nonlinear optical absorption studies, identifying and quantifying these defect states relative to the band gap energy is essential[37]. Near the band edge, Urbach’s empirical rule shows an exponential relationship between the absorption coefficient and photon energy[37, 38].

In this expression, \(\alpha_{0}\) is a fixed value, and hν indicates the energy of the emitted photons, as referenced in[38]:

Here, β is a constant and α ≈ F(R).

The Fig. 10a–c display Ln(F(R)) against photon energy (hν), with the Urbach energy (\(E_{u }\)) derived from the slope of the linear region near the optical band edge, as per the equation[37]:

Table 6 presents the calculated Urbach energy (\(E_{u}\)) values for the samples. It is obvious that the incorporation of composites such as GO (Fig. 10b) and \({\text{GOFe}}_{3} {\text{O}}_{4}\) (Fig. 10c) with Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\) leads to an increase in \(E_{u}\), which suggests a reduction in nanoparticle size as well as a rise in lattice structural disorder. These findings align well with the results obtained from XRD and SEM analyses[12].

Kramers–Kronig

Various techniques exist for determining the optical constants of nanomaterials. In this study, the Kramer-Kronig approach is employed to derive the optical constants of the synthesized nanoparticles[39]. The complex refractive index plays a crucial role in defining the optical behavior of nanoparticles and can be represented by the following equation[40]:

In this context, k represents the extinction coefficient, while n represents the refractive index. According to the Kramers–Kronig relation, the real and imaginary parts of the complex refractive index are described as follows[39]:

Figures 11 and 12 show the refractive index and extinction coefficient curves for the samples, derived from their reflectance spectra and the Kramers–Kronig relations. For most nanomaterials, the refractive index (n) varies depending on synthesis conditions. Figure 11’s UV–Vis spectrum illustrates the synthesized samples’ high refractive index and primary absorption edge[41]. Initially, as photon energy increases at longer wavelengths, the refractive index rises due to strong electron-photon interactions, before declining within the 1.5 to 2.25 eV range. Figure 12 shows the extinction coefficient (k) values, which peak in the longer wavelength region (783–787 nm) and decrease to minima at shorter wavelengths (638–649 nm), indicating greater transparency to light[12]. Table 7 summarizes the maximum refractive indices, extinction coefficients, and other key optical parameters. The slight variations in refractive index values may stem from differences in impurity levels and nanoparticle porosity. Additionally, the decrease in n may be associated with the absorption properties and initial energy gap of the samples[11].

The complex dielectric function can be determined using the following equations, based on the calculated values of n and k:

The real part of the dielectric function, \(\varepsilon_{r }\) describes the delay experienced by light as it propagates through a material, while the imaginary part, \(\varepsilon_{i}\), represents the energy absorbed from the electric field due to dipole motion[11].

Optical absorption coefficient (α) values for each synthesized sample is expressed according to the following relationship[42]:

In this equation, k represents the imaginary component of the refractive index, and λ denotes the wavelength. Figure 13 illustrates the absorption coefficient (α) curves for the samples. The peak values of \(\varepsilon_{r}\), \(\varepsilon_{i}\) and the absorption coefficients are summarized in Table 7.

The band gap and Urbach energy values determined in this study for the synthesized samples closely align with those reported in the literature (Fig. 14), demonstrating a strong consistency with previously published results[43].

Non-linear optical (NLO) characteristics

Sheikh Bahae and his colleagues introduced the z-scan technique to measure the nonlinear optical properties of materials in 1989[44]. The z-scan technique was utilized to investigate the nonlinear refractive index (\(n_{2}\)) and nonlinear absorption coefficient (β) of the synthesized nanomaterials[38, 45, 46]. This approach employs two configurations: open-aperture (OA) to evaluate nonlinear refraction and closed-aperture (CA) to assess intensity-dependent absorption. Measurements were captured using two photodiodes positioned to detect the transmitted and diffracted beam intensities, respectively. The experiments used a continuous-wave Nd:YAG laser at a wavelength of 532 nm with a Gaussian beam profile. Laser powers incident on the samples were set at 20, 25, and 30 mW, given that the initial beam intensity is \(I_{0}\) = 3.694 × 104 W/m2. The nonlinear optical parameters \(n_{2}\) and β were calculated from signals collected by photodiodes 1 and 2, respectively. A schematic of the z-scan experimental setup is shown in Fig. 15, featuring a beam splitter (BS) and the laser beam propagating along the z-axis (negative to positive values)[47]. Laser focusing was performed using a lens (f = 10 cm). Photodiode 1 monitored intensity-dependent absorption in the OA configuration, while photodiode 2 measured diffraction-related intensity variations in the CA configuration[48]. In nonlinear optical media, the refractive index becomes intensity-dependent under high-power laser illumination it is commonly described by the expression n = \(n_{0}\) + \(n_{2}\) I, where the parameters \(n_{0}\) (linear refractive index) and \(n_{2}\) (nonlinear refractive index) describe the optical properties of the material. This nonlinear behavior gives rise to self-focusing when \(n_{2}\) > 0 and self-defocusing when \(n_{2}\) < 0. In cases where \(n_{2}\) > 0, the transmitted signal (T) measured by the photodiode (1) (Fig. 15) shows a prefocal valley and a postfocal peak, whereas the sequence reverses for \(n_{2}\) < 0, indicating the sign change in the nonlinear index.

Similarly, relationship between absorption coefficient and incoming light intensity at elevated intensities is described by α = \(\alpha_{0}\) + βI, where \(\alpha_{0}\) is the linear absorption coefficient and β denotes its nonlinear counterpart. During its translation along the beam path the sample, photodiode (2) in Fig. 15 registers a transmission valley with β > 0, attributed to two-photon absorption (TPA), and a transmission peak when β < 0, corresponding to saturable absorption (SA)[16]. The closed-aperture (CA) and open-aperture (OA) z-scan profiles of the synthesized nanostructures are illustrated in Figs. 16 and 17. The self-defocusing and the negative nonlinear refractive index (\(n_{2}\) < 0) in Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\) are clear from its characteristic peak-valley CA z-scan curve in Fig. 16a. Similar trends are observed for Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO and Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO\({\text{Fe}}_{3} {\text{O}}_{{4{ }}}\) in Fig. 16b, c, respectively. These CA profiles collectively demonstrate lens-induced self-defocusing effects across all samples. In contrast, the OA z-scan traces shown in Fig. 17a–c display pronounced valleys at the focal point, signifying the presence of two-photon absorption (TPA) mechanisms in the studied materials. Open aperture measurements show that transmission is minimized at the focal point (z = 0), a characteristic of reverse saturation absorption (RSA)[16].The nonlinear refractive index (\(n_{2}\)) is computed using the equation provided below[49]:

Accordingly, the effective length can be calculated using the expression provided below:

In this relation, L represents the length of the sample. The experimental data were analyzed using the standard Sheik-Bahae formalism for a Gaussian beam[44]. For the CA z-scan, the theoretical fit was obtained from[48, 49]:

Which \(\Delta \Phi_{0}\) is expressed by the relation k \(n_{2} I_{0} L_{eff} .\) In this context, the Rayleigh diffraction length is defined \(z_{0}\) = k\(\omega_{0}^{2}\)/2, and the wave number is given by k = 2π/λ; the beam waist radius at the first lens’ focal point is \(\omega_{0 }\), which here is about 1 mm; also, the symbol λ signifies the laser beam’s wavelength[49].

Within the open-aperture (OA) analysis, the nonlinear absorption coefficient (β) can be accurately extracted through both theoretical modeling and experimental curve fitting. Graphical representation is achieved using Eq. (21), while numerical values are obtained based on the corresponding computational expression (22).

Hence

Also, a z-scan technique measured the third-order nonlinear optical (NLO) properties of these samples. The nonlinear susceptibility parameter, \(\chi^{\left( 3 \right)}\), and the following equations calculate its real and imaginary parts[50]:

Table 8 summarizes the z-scan experimental data and results for the studied samples. The Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO\({\text{Fe}}_{3} {\text{O}}_{{4{ }}}\) composite exhibited the highest third-order nonlinear optical (NLO) coefficients, likely due to a powerful self-centered effect. These results can be attributed to strong self-focusing. The negative \({\text{n}}_{2}\) within an OA correlates with increased peak transmittance at the focal point, suggesting SA. The positive β parameter observed in all samples indicates reverse saturable absorption (RSA). In fact, RSA in these samples arises from excited-state absorption and free-carrier absorption, resulting in a self-defocusing effect (negative \({\text{n}}_{2}\))[51, 52]. Tables 8 and 9 present the z-scan measurement outcomes and related experimental data. A comparative analysis shows that the Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO composite displays significantly improved third-order nonlinear optical responses compared to pure Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\) and Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO\({\text{Fe}}_{3} {\text{O}}_{{4{ }}}\) samples[53,54,55,56], primarily due to an enhanced self-focusing effect within the material[44, 47].

Conclusion

Using the co-precipitation technique, Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO and Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO\({\text{Fe}}_{3} {\text{O}}_{{4{ }}}\) nanocomposites and Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\) nanoparticles have been successfully synthesized. The effects of GO and GO\({\text{Fe}}_{3} {\text{O}}_{{4{ }}}\) nanoparticles on the Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\) have been investigated for structural, morphological, and optical properties. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis revealed crystallite sizes of 16.31, 4.76, and 11.86 nm for Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\), Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO, and Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO\({\text{Fe}}_{3} {\text{O}}_{{4{ }}}\) samples, respectively. In the SEM image, all nanopowders revealed a sheet-like morphology with particle sizes between 50 and 100 nm. The average grain size of the SEM analysis is greater than their respective < L > estimated by XRD results, which could be due to agglomeration. Furthermore, FTIR spectroscopy revealed key metal oxide functional groups. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDAX) confirmed Cu, Mn, O, C, and Fe, showing a complex elemental composition. Kubelka–Munk analysis for direct band gap determination indicated that the incorporation of GO\({\text{Fe}}_{3} {\text{O}}_{{4{ }}}\) resulted in an increased band gap and a reduction in structural defects and Urbach energy. The linear optical parameters obtained from the K–K method exhibited the highest values of (k), (n), (ε1, ε2), and (α) for Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO nanocomposite. At the excitation wavelength, z-scan measurements yielded the β, \({\text{n}}_{2}\), and third-order \(\chi^{\left( 3 \right)}\) susceptibility values for the samples. The maximum reverse saturable absorption (RSA) coefficients for Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\) and Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO were 8.6 × 10–3 m/W and 6.4 × 10–3 m/W, respectively, at an input power of P0 = 30 mW. Moreover, at the input power P0 = 30 mW, the highest values of \(n_{2}\)(10.3 × \(10^{ - 9 } \;{\text{m}}^{2} /{\text{W }}\)); and \(\chi^{\left( 3 \right)}\) (4.9 × \(10^{ - 3}\) (esu)(, were achieved for the Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\)GO\({\text{Fe}}_{3} {\text{O}}_{{4{ }}}\) nanocomposite. Also, z-scan revealed RSA behavior in metal oxides, where a smaller crystallite size enhances nonlinearity. This research demonstrates the considerable potential of Cu\({\text{Mn}}_{2} {\text{O}}_{4}\) nanocomposites for application in optical limiting and protection systems against high-power lasers. So, these nanocomposites offer a promising avenue for advancing nonlinear optics and photonics, with the capacity to address future requirements in these fields.

Data availability

Data sets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Khan, Y. et al. Classification, synthetic, and characterization approaches to nanoparticles, and their applications in various fields of nanotechnology: A review. Catalysts 12(11), 1386 (2022).

Ni, B., Shi, Y. & Wang, X. The sub-nanometer scale as a new focus in nanoscience. Adv. Mater. 30(43), 1802031 (2018).

Narayan, S. A comprehensive review of manganese dioxide nanoparticles and strategy to overcome toxicity. Nanomed. J. 10(1) (2023).

Medhi, R., Marquez, M. D. & Lee, T. R. Visible-light-active doped metal oxide nanoparticles: Review of their synthesis, properties, and applications. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 3(7), 6156–6185 (2020).

Chakradhary, V. K., Ansari, A. & Akhtar, M. J. Design, synthesis, and testing of high coercivity cobalt doped nickel ferrite nanoparticles for magnetic applications. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 469, 674–680 (2019).

Jwad, A. S. & Abdulridha, A. R. Enhancement the structural and electrical properties of PVA by the additive of Y2O3 and SrCO3 nanoparticles and apply as the antibacterial. J. Nanostruct. 14(2), 481–491 (2024).

Vijayaprasath, G., Murugan, R., Mahalingam, T. & Ravi, G. Comparative study of structural and magnetic properties of transition metal (Co, Ni) doped ZnO nanoparticles. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 26(9), 7205–7213 (2015).

Sakib, M. N., Ahmed, S., Rahat, S. S. M. & Shuchi, S. B. A review of recent advances in manganese-based supercapacitors. J. Energy Storage 44, 103322 (2021).

Sarathkumar, A., Manjula, S. & Sivakumar, D. G. Preparation of pure-phase Cu2mnsns4 nanoparticle for enhanced electrochemical and photocatalytic properties. Available at SSRN 5001662.

Mabhouti, K., Norouzzadeh, P. & Taleb-Abbasi, M. Effects of Fe Co, or Ni substitution for Mn on La0.7Sr0.3MnO3 perovskite: Structural, morphological, and optical analyses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 610, 122283 (2023).

Norouzzadeh, P., Mabhouti, K., Golzan, M. M. & Naderali, R. Investigation of structural, morphological and optical characteristics of Mn substituted Al-doped ZnO NPs: A Urbach energy and Kramers-Kronig study. Optik 204, 164227 (2020).

Norouzzadeh, P., Mabhouti, K., Golzan, M. & Naderali, R. Consequence of Mn and Ni doping on structural, optical and magnetic characteristics of ZnO nanopowders: The Williamson–Hall method, the Kramers–Kronig approach and magnetic interactions. Appl. Phys. A 126(3), 154 (2020).

Pramothkumar, A., Senthilkumar, N., Jothivenkatachalam, K. & Fermi Hilbert Inbaraj, P. Flake-like CuMn2O4 nanoparticles synthesized via co-precipitation method for photocatalytic activity. Physica B Condens. Matter 572, 117–124 (2019).

Hutchings, D. C., Sheik-Bahae, M., Hagan, D. J. & Van Stryland, E. W. Kramers–Krönig relations in nonlinear optics. Opt. Quant. Electron. 24(1), 1–30 (1992).

De, L. & Kronig, R. On the theory of dispersion of x-rays. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 12(6), 547–557 (1926).

Asaldoust, F., Mabhouti, K., Jafari, A. & Taleb-Abbasi, M. Study of Z-scan technique, dispersion energy, and Wemple–DiDomenico model on Cu, Cr and Fe doped NiO nanopowder for the determination of nonlinear and linear optical characteristics. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 9963 (2025).

Zarei, K., Jafari, A. & Mabhouti, K. Investigation of the nonlinear optical characteristics of the La0.7Sr0.3MnO3 nano-perovskite under (iron, cobalt, and nickel) substitution for manganese by Z-Scan technique and Wemple–DiDomenico model. Optik 320, 172137 (2025).

Nawaz, M. et al. Transport properties in spinel ferrite/graphene oxide nanocomposites for electromagnetic shielding. Ceram. Int. 47(18), 25505–25513 (2021).

Karmakar, S., Varma, S. & Behera, D. Investigation of structural and electrical transport properties of nano-flower shaped NiCo2O4 supercapacitor electrode materials. J. Alloys Compd. 757, 49–59 (2018).

Karmakar, S. & Behera, D. Almond-West type grain and grain boundary conduction-modified dielectric relaxation in NdCoO3. Appl. Phys. A 124(11), 745 (2018).

Karmakar, S. et al. A study on optical and dielectric properties of Ni-ZnO nanocomposite. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 88, 198–206 (2018).

Nath, D., Singh, F. & Das, R. X-ray diffraction analysis by Williamson-Hall, Halder–Wagner and size-strain plot methods of CdSe nanoparticles-a comparative study. Mater. Chem. Phys. 239, 122021 (2020).

Nazari, N., Golzan, M. M. & Mabhouti, K. Study of Urbach energy and Kramers–Kronig on Mn and Zn doped NiFe2O4 ferrite nanopowder for the determination of structural and optical characteristics. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 6407 (2024).

Norouzzadeh, P., Mabhouti, K., Golzan, M. & Naderali, R. Comparative study on dielectric and structural properties of undoped, Mn-doped, and Ni-doped ZnO nanoparticles by impedance spectroscopy analysis. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 31(10), 7335–7347 (2020).

Quinten, M. Optical Properties of Nanoparticle Systems: Mie and Beyond (Wiley, 2010).

Ni, H. et al. Synthesis and characterization of CuFeMnO4 prepared by co-precipitation method. J. Mater. Sci. 53(5), 3581–3589 (2018).

Sobhani-Nasab, A., Eghbali-Arani, M., Hosseinpour-Mashkani, S. M., Ahmadi, F. & Rahimi-Nasrabadi, M. Eco-friendly preparation and characterization of CuMn2O4 nanoparticles with the green capping agent and their photocatalytic and photovoltaic applications. Iran. J. Catal. 10(2) (2020).

Khan, M. F. et al. Sol-gel synthesis of thorn-like ZnO nanoparticles endorsing mechanical stirring effect and their antimicrobial activities: Potential role as nano-antibiotics. Sci. Rep. 6(1), 27689 (2016).

Khalid, R., Alhazaa, A. N. & Khan, M. M. Synthesis, characterization and properties of Mn-doped ZnO nanoparticles. Appl. Phys. A 124(8), 536 (2018).

Soltanpour, P., Naderali, R. & Mabhouti, K. Comparative study on structural, morphological, and optical properties of MS/Fe3O4 nanocomposites and M-doped Fe3O4 nanopowders (M= Mn, Zn). Sci. Rep. 14(1), 21287 (2024).

Khodadadi, B. & Bordbar, M. Sonochemical synthesis of undoped and Co-doped ZnO nanostructures and investigation of optical and photocatalytic properties. Iran. J. Catal 6(1), 37–42 (2016).

Ajmi, A., Karoui, K., Khirouni, K. & Rhaiem, A. B. Optical and dielectric properties of NaCoPO4 in the three phases α, β and γ (2019).

Sagheer, R. et al. Effect of Mg doping on structural, morphological, optical and thermal properties of ZnO nanoparticles. Optik 200, 163428 (2020).

Kamakshi, T., Sundari, G. S., Erothu, H. & Rao, T. Synthesis and characterization of graphene based iron oxide (Fe3O4) nanocomposites. Rasayan J. Chem 11(3), 1113–1119 (2018).

Indrayana, I., Tuny, M., Putra, R., Istiqomah, N., & Suharyadi, E. (2021). Optical properties of Fe3O4/chitosan and its applications for signal amplifier in surface plasmon resonance sensor. In 2nd International Conference on Science, Technology, and Modern Society (ICSTMS 2020).

Enhessari, M., Salehabadi, A., Maarofian, K. & Khanahmadzadeh, S. Synthesis and physicochemical properties of CuMn. Int. J. Bio-Inorg. Hybr. Nanomater. 5(2), 115–120 (2016).

Njagi, E. C., Genuino, H. C., King’ondu, C. K., Dharmarathna, S. & Suib, S. L. Catalytic oxidation of ethylene at low temperatures using porous copper manganese oxides. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 421, 154–160 (2012).

Zhang, Y. X. & Wang, Y. H. Nonlinear optical properties of metal nanoparticles: A review. RSC Adv. 7(71), 45129–45144 (2017).

Zak, A. K., Ghanbari, A. & ShekoftehNarm, T. The effect of molybdenum on optical properties of ZnO nanoparticles in ultraviolet–visible region. Adv. Powder Technol. 28(11), 2980–2986 (2017).

Mabhouti, K., Norouzzadeh, P. & Taleb-Abbasi, M. Effects of Fe Co, or Ni substitution for Mn on La0.7Sr0.3MnO3 perovskite: Structural, morphological, and optical analyses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 610, 122283 (2023).

Lemziouka, H. et al. Synthesis, structural, optical and dispersion parameters of La-doped spinel zinc ferrites ZnFe2−xLaxO4 (x = 0.00, 0.001, 0.005, 0.01 and 0.015). Vacuum 182, 109780 (2020).

Aghgonbad, M. M. & Sedghi, H. Optical and electronic analysis of pure and Fe-doped ZnO thin films using spectroscopic ellipsometry and Kramers-Kronig method. Int. J. Nanosci. 18(01), 1850013 (2019).

El Ghandoor, H., Zidan, H., Khalil, M. M. & Ismail, M. Synthesis and some physical properties of magnetite (Fe3O4) nanoparticles. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 7(6), 5734–5745 (2012).

Sheik-Bahae, M., Said, A. A. & Van Stryland, E. W. High-sensitivity, single-beam n 2 measurements. Opt. Lett. 14(17), 955–957 (1989).

Khosrozadeh, M., Mabhouti, K., Norouzzadeh, P. & Naderali, R. Complex impedance spectroscopy, dielectric response, and magnetic properties of the La0.7Sr0.3BO3 (B = Mn, Fe Co, or Ni) perovskite oxides. Ceram. Int. 50(1), 315–328 (2024).

Tahmasbi, A., Jafari, A. & Nikoo, A. Synthesis, characterization, and nonlinear optical properties of copper (II) ligand Schiff base complexes derived from 3-Nitrobenzohydrazide and benzyl. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 10988 (2023).

Afshar, B. A., Jafari, A., Golzan, M. M. & Naderali, R. Nonlinear optical properties of gold nanoparticles produced by laser ablation at two different radiation wavelengths. Results Opt. 12, 100462 (2023).

Naderali, R., Jafari, A. & Motiei, H. Nonlinear optical properties of carboxymethyl starch nanocomposite by Z-scan technique using a Nd–YAG laser. Appl. Phys. B 120(4), 681–687 (2015).

Jafari, A., Zeynizadeh, B. & Darvishi, S. Study of linear and nonlinear optical properties of nickel immobilized on acid-activated montmorillonite and copper ferrite nanocomposites. J. Mol. Liq. 253, 119–126 (2018).

Jafari, A., Naderali, R. & Motiei, H. The effect of doping acid on the third-order nonlinearity of carboxymethyl cellulose by the Z-scan technique. Opt. Mater. 64, 345–350 (2017).

Chen, J., Zhang, W. & Pullerits, T. Two-photon absorption in halide perovskites and their applications. Mater. Horiz. 9(9), 2255–2287 (2022).

Menon, P. S. et al. Role of surface defects in the third order nonlinear optical properties of pristine NiO and Cr doped NiO nanostructures. Ceram. Int. 49(4), 5815–5827 (2023).

John Abel, M. et al. Facile synthesis of solar light active spinel nickel manganite (NiMn2O4) by co-precipitation route for photocatalytic application: M. John Abel et al. Res. Chem. Intermed. 46(7), 3509–3525 (2020).

Fabbiyola, S., Sailaja, V., Kennedy, L. J., Bououdina, M. & Vijaya, J. J. Optical and magnetic properties of Ni-doped ZnO nanoparticles. J. Alloys Compd. 694, 522–531 (2017).

Pepe, Y. et al. Nonlinear optical performance and optical limiting of germanate glasses modified with PbF2 and B2O3 induced by nanosecond pulsed laser. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 590, 121704 (2022).

Hassanien, A. S. & Akl, A. A. Influence of composition on optical and dispersion parameters of thermally evaporated non-crystalline Cd50S50−xSex thin films. J. Alloys Compd. 648, 280–290 (2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SN: Investigation, Writing original draft, Software. HK: Supervision. AJ: Supervision, Formal analysis. KM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Editing original draft.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Najafialiabadi, S., Kangarlou, H., Jafari, A. et al. Enhanced nonlinear optical properties of GO and Fe3O4-Modified CuMn2O4 nanocomposites. Sci Rep 15, 42338 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26354-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26354-w