Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) poses a significant global health burden due to its high incidence and mortality rates. Early diagnosis is crucial for improving patient outcomes; however, current diagnostic methods, such as the measurement of α-fetoprotein (AFP) levels, have notable limitations. Our study aimed to explore non-invasive markers with superior diagnostic efficacy for HCC. Our findings revealed a significant downregulation of FGA, FGB, and FGG in HCC, with lower expression levels strongly associated with reduced overall survival and disease-free survival rates. Notably, the diagnostic accuracies of FGA and FGB in detecting HCC, particularly in its early stages, surpassed that of AFP. ELISA results further confirmed the reduced serum levels of these proteins in HCC patients. In addition, a negative correlation was observed between fibrinogen expression and the abundance of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in HCC. FGA and FGB emerge as promising non-invasive biomarkers for HCC, offering improved diagnostic accuracy compared to AFP. Their consistent downregulation across different stages of HCC and their linkage to the tumor microenvironment underscore their potential role in HCC pathogenesis. These insights warrant further investigation and may contribute to the development of more effective diagnostic tools.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), a primary liver malignancy, is a leading cause of cancer-related deaths globally, accentuated by its late diagnosis and treatment complexity1. The etiology of HCC is multifaceted, and the prominent risk factors are chronic infections caused by hepatitis B and C viruses, alcohol consumption, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and exposure to aflatoxins2,3,4. In 2020, liver cancer was diagnosed in approximately 905,700 people globally, with approximately 830,200 deaths. The age-standardized incidence and mortality rates were 9.5 and 8.7 per 100,000 individuals, respectively. Liver cancer was among the top three causes of cancer-related deaths in 46 countries and among the top five causes in 90 countries. This emphasizes the urgent need for preventive measures and early diagnosis for HCC5.

Despite the wide clinical use of serum α-fetoprotein (AFP) and prothrombin-induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II (PIVKA-II) as HCC biomarkers, each exhibits notable limitations in sensitivity and specificity, particularly in early-stage HCC6. For instance, AFP is often within the normal range in a considerable subset of early tumors, while non-malignant chronic liver diseases can also elevate AFP, confounding diagnostic accuracy. PIVKA-II provides improved detection in some patients but similarly demonstrates false negatives and inconsistent performance6.

Accordingly, we focused on identifying effective HCC diagnostic markers which led to the investigation of the fibrinogen family, encompassing FGA, FGB, and FGG, as significant targets. Fibrinogen, a vital soluble plasma glycoprotein, plays a pivotal role in the hemostatic process through its essential functions in blood clot formation and tissue repair. Comprised of three polypeptide chains (α, β, and γ), fibrinogen is synthesized by the liver and operates at the terminal stage of the clotting cascade7,8. Upon activation by thrombin, fibrinogen is converted into fibrin, an insoluble protein that forms the blood clot matrix. This conversion not only stabilizes the clot but also acts as a scaffold for cellular components involved in wound healing, which in turn facilitates tissue repair7,9. Furthermore, fibrinogen interacts with various cellular receptors, modulating cellular adhesion, migration, and proliferation, which are critical for the inflammatory response and restoration of tissue integrity following injury10. Through these mechanisms, fibrinogen plays an indispensable role in maintaining vascular integrity and promoting the healing of damaged tissues, underscoring its significance beyond coagulation to include pivotal contributions to inflammation and wound healing11,12,13.

Alterations in fibrinogen have been reported in various cancers, and its levels have been associated with tumor progression and metastasis as an acute-phase reactant whose expression increases in response to systemic inflammation14. In the context of liver cancer, the roles and expression patterns of the fibrinogen family members are controversial across studies15,16.

Fibrinogen proteins are largely produced in hepatocytes, and their dysregulation can reflect both liver-specific pathology and tumor-driven inflammation, positioning them as potential biomarkers for HCC17. Moreover, certain members of the fibrinogen family may have implications not only for early detection but also for tumor aggressiveness, thereby offering prognostic insight beyond what AFP and PIVKA-II typically provide.

Hence, we aimed to clarify the involvement of the fibrinogen family in HCC by analyzing two comprehensive liver cancer datasets, GSE89377 and GSE114564, which we developed as public data resources18,19. We identified the fibrinogen gene family (FGA, FGB, FGG) as downregulated in HCC, with potential as better noninvasive diagnostic markers than AFP. Further analysis revealed a negative correlation between fibrinogen levels and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) in the HCC microenvironment, highlighting fibrinogen’s diagnostic and immune landscape roles, aiding targeted HCC diagnostic strategies.

Methods

Clinical specimens

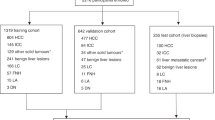

To validate our findings on the fibrinogen family expression, HCC samples were obtained from two patient cohorts at Ajou University Hospital, Suwon, South Korea. qRT-PCR was performed on 86 pairs of frozen HCC and noncancerous liver tissues. Enzyme-linked immune sorbent assay (ELISA) was conducted on serum samples from 34 chronic hepatitis (CH) patients, 33 with liver cirrhosis (LC), 158 with HCC, and 30 normal liver (NL) individuals. NL were patients aged 18–50 without medical history. CH was defined by persistent serum HBsAg or hepatitis C RNA over six months, and LC was diagnosed by ultrasonography and elastography. Early-stage HCC was defined by a single lesion < 2 cm (mUICC stage I). Clinical data included age, sex, AST, ALT, platelet count, AFP level, liver disease etiology, albumin, bilirubin, and INR. Demographics and clinical characteristics are in Tables 1 and 2.

Bulk RNA datasets analysis

In this study, we constructed a comprehensive database by aggregating RNA-seq datasets from previously published HCC-related studies, focusing on various phenotypes, including normal and HCC subtypes20,21,22,23. RNA expression data were structured in a matrix format, with rows representing genes using official gene symbols and columns representing individual samples, including group information. Expression values were transformed into transcripts per million (TPM) using the hg38 reference genome.

For the analysis, expression values of fibrinogen family genes were normalized to log2 (TPM + 1) for each sample and group. This normalization facilitated comparisons of gene expression across different conditions, providing insights into their relative expression levels within the context of the study.

Comprehensive analysis using microarray, RNA-seq, and protein expression data

In this study, we conducted comparative expression analysis to identify gene signatures across various liver disease stages, leveraging the capabilities of both microarray and RNA-seq datasets. Specifically, the GSE89377 and GSE114564 datasets were analyzed; they encompass a broad spectrum of liver conditions, from normal to advanced HCC (aHCC). These datasets are diverse and include a vast array of samples, with GSE89377 comprising 48,865 probes and GSE114564 containing 39,865 genes categorized into stages such as NL, CH, LC, dysplastic nodules (DN), early HCC (eHCC), and aHCC. Through differential expression analyses, we aimed to pinpoint the genes having significant changes in expression. Next, we compared liver cancer and noncancerous liver samples to select the genes with at least a two-fold decrease in their expression at a significance level of P < 0.001 using Welch’s t-test. To elucidate the gene expression patterns correlated with liver cancer progression, we applied the cluster identification via Connectivity Kernels (CLICK) algorithm, a clustering method from the Expander program, which facilitates the extraction of correlated gene modules to deduce their biological implications. The exploration was extended to the mRNA expression levels of FGA, FGB, and FGG within HCC, utilizing data from The Cancer Genome Atlas liver hepatocellular carcinoma project (TCGA_LIHC) in cBioPortal (https://www.cbioportal.org/) and the Hepatocellular Carcinoma Expression DataBase 2.0 (HCCDB 2.0; http://xsh.mywsat.cn/#/home). The protein expression levels of FGA, FGB, and FGG in human HCC were assessed using representative immunohistochemistry (IHC) images obtained from the Human Protein Atlas (https://www.proteinatlas.org/). We selected antibodies specific for FGA (CAB016776), FGB (HPA001901), and FGG (CAB033120) to accurately target each gene. The IHC staining intensity was categorized into positive and negative groups, which was instrumental in quantifying the negativity ratio of each protein.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) dataset and analysis

To investigate the fibrinogen gene family expression patterns and composition of single HCC cells, we obtained expression data from 50,023 single cells of 46 patients with HCC from the GSE151530 dataset of the single-cell Atlas in Liver Cancer data, which is commonly used to evaluate gene expression in tumor and non-tumor cells of patients with liver cancer24. Using the metadata included in the dataset to annotate each cell, singleR and a manual script based on MDSC-specific genes were applied to subdivide the cell types and confirm the distribution of MDSC.

To distinguish the MDSC sub-clusters, the shared nearest neighbor module optimization algorithm was applied to the first 14 principal components for Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP). The cells were then clustered using the FindClusters function with a resolution parameter of 0.4. Subsequently, based on the UMI count for each gene in the fibrinogen family, positive and negative cell groups were distinguished and the functions of each sub-cluster were examined. Additionally, functional enrichment analysis was conducted for each cluster using single sample Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (ssGSEA) in the hallmark database.

Analysis of spatial transcriptomic sequencing datasets

To acquire spatial transcriptome data for HCC tissues related to the fibrinogen family genes, spatial data (skrx2fz79n) which were utilized in a previous study were collected25. Using the Seurat R package, spatial RDS files for each dataset were read and spatial count values for individual cells within the data were obtained. The sctransform method was employed to normalize the spatial data and construct regularized negative binomial models to mitigate technical noise while retaining biological variance. Tissue clusters were annotated based on marker gene information from prior studies to differentiate malignant cells from non-malignant cells. Spatial distributions and normalized counts for fibrinogen family genes were calculated and visualized, including dim plots and bar plots generated using Seurat and ggplot2 (version 3.4.4).

Cell culture

Human HCC cell lines, including SNU368, SNU398, SNU423, SNU475, SNU449, Hep3B, and Huh-7 were obtained from the Korean Cell Line Bank (Seoul, South Korea). Immortalized normal hepatocytes (MIHA) were obtained from Dr. Roy-Chowdhury (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY, USA). HCC and MIHA cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 or Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin (GenDEPOT, Barker, TX, USA). Cells were grown in a humidified incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

Quantitative analysis of fibrinogen gene expression in HCC tissues and cell lines

Total RNA was extracted from frozen tissues and cell lines using the QIAzol reagent (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. We synthesized cDNA from 500 ng total RNA employing 5X PrimeScript™ RT Master Mix (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan). The cDNA synthesis conditions were as follows: 37°C for 15 min, 85°C for 5 s, and 4°C. qRT-PCR was performed using the amfiSure qGreen Q-PCR Master Mix (GenDEPOT) and monitored in real time using a CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). HMBS was employed as the internal control for tissue samples, and GAPDH was utilized as the internal control for cell line studies. The amplification FGA primer sequences were 5′- AGATGAGGCCGGAAGTGAAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGAGAAGTGTGGATACCTCTGAC-3′ (reverse); the FGB primer sequences were 5′-GGACAGTGATTCAGAACCGTCA-3′ (forward) and 5′- TCACCTGGTAGGCCACAGTA − 3′ (reverse); the FGG primer sequences were 5′-ACCCGGTGGTATTCCATGAAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CGTCTCCAGCCTGTTTGGCT-3′ (reverse); the HMBS primer sequences were 5′-ACGGCTCAGATAGCATACAAGAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTTACGAGCAGTGATGCCTACC-3′ (reverse); and the GAPDH primer sequences were 5’-AGTATGACAACAGCCTCAAG-3’ (forward) and 5’ TCATGAGTCCTTCCACGATA-3’ (reverse). The PCR conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 2 min, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 58 °C for 34 s, and 72 °C for 30 s, followed by a dissociation stage at 95 °C for 10 s, 65 °C for 5 s, and 95 °C for 5 s. The relative standard curve method (2−ΔΔCt) was used to determine the relative expression. All experiments were performed at least three times.

IHC analysis of fibrinogen expression in the tissue samples of BALB/c nude mouse

Tissue samples from BALB/c nude mice injected with Huh-7 cells to develop an orthotopic xenograft tumor model and were processed using IHC to evaluate the fibrinogen protein expression levels. After tumor development, the tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, and sectioned into 5-µm slices. These sections were then deparaffinized with xylene, rehydrated using an alcohol gradient, and incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4 °C. Primary antibodies specific for FGA (ab92572; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), FGB (sc-271035; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, Texas, USA), and FGG (sc-133226; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, Texas, USA) were used. Following incubation with secondary antibodies for 1 h to develop the desired staining intensity, this meticulous protocol enabled for the detailed evaluation of fibrinogen protein levels exclusively in the developed tumor tissues of mouse models.

ELISA-based quantification

Serum samples, collected from both healthy individuals and patients with liver disease, were immediately stored at − 80 °C post-collection. For analyses, these samples were gently thawed at 4 °C. ELISA was employed to quantify the FGA, FGB, and FGG protein concentrations within the serum samples of each group. Using specific ELISA kits (FGA: HUEB0398, FGB: UEB0399, FGG: UEB0394; Assay Genie, Ireland), measurements were performed in strict adherence to the manufacturer’s protocol, ensuring the accurate and reliable assessment of these proteins as HCC biomarkers.

Comprehensive immune infiltration analysis using TIMER 2.0

Our analysis leveraged the Tumor Immune Estimation Resource 2.0 (TIMER 2.0) tool (http://timer.comp-genomics.org/timer/), which is a comprehensive tool for investigating the correlation between gene expression and immune cell infiltration across more than 30 cancer types from The TCGA26,27,28.

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as mean values with ± standard deviation. Differences between groups were evaluated using the unpaired Student’s t-test using GraphPad software (version 10.0; GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were performed to evaluate the impact of fibrinogen genes (FGA, FGB, FGG) on overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Univariate Cox regression was conducted separately for age, gender, serum AFP, tumor grade, and each fibrinogen gene. Multivariate Cox regression models were constructed to assess the prognostic contribution of each gene while adjusting for clinical variables (age, gender, AFP, and tumor grade). Gender was treated as a binary categorical variable (male vs. female), and tumor grade was analyzed as an ordinal variable (G1–G4). These analyses were performed using SPSS software version 22. For multiple comparisons among three or more groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post-hoc test was applied. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to analyze the survival curves; the log-rank test was used to assess the differences between groups. receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, conducted using MedCalc, was used to assess the sensitivity, specificity, and area under the curve (AUC) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for markers. Logistic regression analysis was performed using SPSS for two- or three-marker combinations; the cut-offs were determined using MedCalc’s maximum Youden index. All the experiments were repeated at least three times, and statistical significance was set at a P-value < 0.05.

Results

Identification of fibrinogen family as a potential HCC marker using transcriptomic datasets

We used two comprehensive multistage liver cancer datasets, GSE89377 and GSE114564, to identify potential biomarkers for HCC diagnosis (Fig. 1a). Through an integrated differential expression analysis, we conducted the Welch’s t-test, which revealed genes having a significance level of P < 0.001 and an expression fold change of less than 2 in HCC compared to those in noncancerous liver tissues. This approach identified a common set of 169 genes across both liver cancer datasets that exhibited a consistent decrease in expression in HCC; thus, they were selected as candidate tumor suppressor genes. Using the cluster identification via Connectivity Kernels (CLICK) algorithm in the Expander tool, we performed pattern analysis on a set of 169 genes. The cluster with the highest homogeneity score, consisting of 88 genes, demonstrated a pattern of decreased expression correlated with HCC progression, indicating that these genes are potential tumor suppressor genes involved in liver cancer development. Notably, within these gene lists, the fibrinogen family members, including FGA, FGB, and FGG, were found to exhibit very similar expression patterns, all showing a common decrease in expression in correlation with liver disease progression (Fig. S1A).

Identification of FGA, FGB, and FGG as potential diagnostic biomarkers for HCC using public-omics data. (A) Analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) for HCC diagnosis using the multistage liver cancer datasets GSE89377 and GSE114564. (B) The expression levels of FGA, FGB, and FGG were analyzed in multiple stages of liver disease including non-cancerous liver (NL; normal liver, CH; chronic hepatitis, LC; liver cirrhosis, DN; dysplastic nodule) and tumor (eHCC; early staged HCC, aHCC; advanced HCC) tissues using the GSE89377 and GSE114564 datasets. (C) Heatmap and hierarchical clustering analysis of FGA, FGB, and FGG according to the stage of liver disease. (D) Investigation of the expression patterns of FGA, FGB, and FGG from normal liver to HCC using the integrated liver expression atlas, GepLiver DB, and bulk RNA-seq data. Left: Heatmap of FGA, FGB, and FGG expression (z-score) in a total of 13 data sets from GepLiver DB. Right: FGA, FGB, and FGG expression across tissues with different phenotypes. (E) Expression of FGA, FGB, and FGG in non-malignant and malignant liver cell analyzed using spatial transcriptomics data. Statistically significant differences were determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. Data are shown as mean ± SD.

Subsequent validation in the multistage liver disease datasets GSE89377 and GSE114564 confirmed the statistically significant downregulation of FGA, FGB, and FGG in HCC compared to that in noncancerous conditions including NL, CH, LC, and DN (Fig. 1b). Hierarchical clustering analysis revealed that these genes exhibited similar expression patterns, with the most significant decrease observed in advanced stages of liver cancer (Fig. 1c). Furthermore, an analysis using HCCDB 2.0 across 18 datasets demonstrated a consistent decrease in the expression of these genes in HCC tissues compared to those in adjacent noncancerous liver tissues (Table S1). Additional investigations using the Integrated Liver Expression Atlas, GepLiver DB, and bulk RNA-seq data corroborated the progressive decrease in FGA, FGB, and FGG expression from NL to HCC (Fig. 1d). Spatial transcriptomic data derived from Mendeley’s 10X Visium platform further confirmed the lower expression pattern of FGA, FGB, and FGG in malignant liver cells compared to that in non-malignant cells, with a highly similar expression pattern across the cells (Fig. 1e). The protein expression levels of FGA, FGB, and FGG in the HCC tissues were investigated using the Human Protein Atlas database. FGA, FGB, and FGG were negatively expressed in 90%, 14.3%, and 85.7% of the cases, respectively, indicating a predominantly negative expression pattern for these genes in HCC, which supports their downregulation at the protein level in liver cancer (Fig. S1B).

Clinical implications of fibrinogen family expression in the patients with HCC

Using TCGA Pan-Cancer dataset, we investigated the expression of FGA, FGB, and FGG in tumor and non-tumor tissues. We observed a specific increase in the expression of these genes in liver-associated cancers, cholangiocarcinoma (CHOL), and LIHC. Moreover, their levels displayed increased expression in normal liver tissues, thereby confirming the liver specificity of FGA, FGB, and FGG (Fig. S2). To further elucidate the mRNA expression patterns of these genes at the individual patient level, we analyzed data from 371 patients with liver cancer within the TCGA_LIHC cohort. Expression levels of FGA, FGB, and FGG were categorized into three groups—High (z-score ≥ 0.5), Low (z-score ≤ − 0.5), and No Alteration (–0.5 < z-score < 0.5)—based on mRNA expression z-scores relative to diploid samples, following the cBioPortal convention. Using these thresholds, 15.4%, 17.0%, and 15.9% of patients were classified into the High expression groups for FGA, FGB, and FGG, respectively, whereas 51.2%, 50.7%, and 50.7% were classified into the Low expression groups. Heatmaps illustrated a general trend of decreased expression in tumor tissues compared to adjacent non-tumor tissues (Fig. 2a).

The FGA, FGB, and FGG expression pattern and their clinical correlations in patients with HCC. (A) The oncoprint analysis of FGA, FGB, and FGG expression in patients with HCC using TCGA_LIHC arranged by the mRNA expression level. mRNA expression is represented as z-scores relative to diploid samples and categorized as high (z > 0) or low (z < 0). Genetic alterations are annotated separately. (B) Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was used to evaluate the effect of the fibrinogen family expression on overall survival (OS) (left) and disease-free survival (DFS) (right). (C) Proportions of alterations in the expression levels of the fibrinogen family members across different clinical characteristics. Left: Distribution of patients according to the histologic grades of the neoplasm. Right: Distribution of patients according to vascular invasion. Statistically significant differences were determined using unpaired Student’s t-test. (D) Kaplan–Meier survival curves assessing the prognostic impact of individual gene expression (FGA, FGB, FGG) and the combined expression profile (FGA + FGB + FGG) on OS (top row) and DFS (bottom row). Statistical differences were determined by log-rank test. All gene expression values were dichotomized by median expression levels. Statistically significant differences were determined using the log-rank test; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01. Data are shown as mean ± SD.

Next, we assessed the clinical relevance of the fibrinogen family protein expression in patients with liver cancer. By classifying the expression of the fibrinogen family members into High, Low, and No Alteration groups within the TCGA_LIHC dataset, we evaluated patient prognosis based on their expression levels. Our analysis demonstrated that patients with low expression levels of the fibrinogen family members exhibited significantly poorer outcomes in terms of OS (log-rank P = 0.014) and DFS (log-rank P = 0.0054) (Fig. 2b). Analysis of the distribution of patients across the histological grades of the neoplasm showed a decreasing proportion in the High group and an increasing proportion in the Low group from the G1 to the G3/G4 stages (Fig. 2c, left). Additionally, the distribution of the vascular invasion status indicated a higher proportion of patients with vascular invasion in the Low group (Fig. 2c, right).

We then classified patients into high- and low-expression groups based on the median values. Subsequently, we identified a subset of patients with high expression levels of all three genes (All_High), and another subset with low expression levels of all three genes (All_Low). Survival analyses for OS and DFS confirmed that patients with reduced expression levels of individual genes, as well as those with low expression levels of FGA, FGB, and FGG, exhibited worse outcomes in terms of OS and DFS (Fig. 2d; OS in the upper panel, DFS in the lower panel).

To further validate these associations, we performed Cox proportional hazards regression analyses using the TCGA_LIHC clinical dataset. In the univariate analyses for DFS, low expression of FGA, FGB, and FGG remained significantly associated with worse prognosis (p = 0.005, 0.009, and 0.009, respectively). Although these associations did not reach statistical significance in the multivariate models, all three genes showed a consistent trend toward poorer outcomes (hazard ratio < 1). For OS, no statistically significant associations were observed in either univariate or multivariate analyses. All corresponding results are provided in Supplementary Tables S2 to S5.

Diagnostic analysis of fibrinogen family expression in liver cancer detection

To validate our findings derived from public data analyses, we conducted qRT-PCR assays to assess the mRNA expression pattern of FGA, FGB, and FGG in a panel comprising the normal liver cell line, MIHA, and seven liver cancer cell lines (SNU368, SNU398, SNU423, SNU475, SNU449, Hep3B, and Huh-7). Compared to MIHA, FGA and FGG expression levels were consistently reduced in six cancer cell lines, with the exception of Huh-7. For FGB, lower expression was observed in five liver cancer cell lines, excluding Hep3B and Huh-7 (Fig. 3a).

The FGA, FGB, and FGG expression and diagnostic analyses in HCC cell lines and tissues. (A) The FGA, FGB, and FGG mRNA expression levels in immortalized normal hepatocytes (MIHA) and seven human HCC cell lines were assessed using qRT-PCR. (B) Fold change in FGA, FGB, and FGG expression in 86 pairs of HCC tissues and corresponding non-cancerous liver tissues. (C) Comparative analysis of FGA, FGB, and FGG expression in 86 pairs of HCC tissues and corresponding non-cancerous liver tissues from the same patient. (D) Comparative analysis of the AUC in HCC tissues to validate the diagnostic potential of FGA, FGB, and FGG as biomarkers for HCC. (E) Representative IHC photomicrographs and rate of stained areas of FGA, FGB, and FGG expression in non-cancerous and HCC tissues of orthotopic xenograft mouse model. Scale bar = 50 μm. ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. Data are shown as mean ± SD.

We evaluated the mRNA expression of FGA, FGB, and FGG in a cohort of 86 paired liver cancer tissue samples using qRT-PCR. Our results showed decreased expression of FGA, FGB, and FGG in 75 (87.2%), 74 (86%), and 71 (82.6%) patients, respectively (Table 1; Fig. 3b).

A comparative analysis of the expression pattern of FGA, FGB, and FGG in cancerous versus noncancerous liver tissues from the same patients revealed a statistically significant decrease in their expression in most cancer tissues (Fig. 3c). To ascertain the diagnostic potential of FGA, FGB, and FGG as biomarkers for liver cancer, ROC curve analysis was performed. The results revealed AUC values of 0.85 (95% CI, 0.79–0.91) for FGA, 0.88 (95% CI, 0.82–0.93) for FGB, and 0.83 (95% CI, 0.76–0.89) for FGG, indicating that FGB possesses the highest diagnostic potential in tissue samples (Fig. 3d). Additionally, immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis was performed to examine the expression pattern of FGA, FGB, and FGG in noncancerous and cancerous liver tissues from orthotopic xenograft mouse models. The expression levels of FGA, FGB, and FGG were lower in the liver cancerous tissues than those in the noncancerous tissues (Fig. 3e).

Evaluation of the fibrinogen family expression in the Sera of patients with liver cancer

To assess the potential of employing FGA, FGB, and FGG as biomarkers for liver cancer, we conducted ELISA for serum samples obtained from NL individuals and patients with HCC. In a test cohort comprising 10 healthy controls (NL) and 10 patients with HCC, we observed significantly lower serum protein concentrations of FGA, FGB, and FGG in patients with HCC (Fig. 4a). Further validation was performed in a larger cohort comprising 30 NL individuals, 34 patients with CH, 33 patients with LC, and 158 patients with liver cancer; ELISA was performed to measure the FGA, FGB, and FGG protein concentrations according to the mUICC stages. Significant reductions in the protein concentrations of FGA, FGB, and FGG were observed in the patients with liver cancer (mUICC I, II, III, and IV) and LC compared to those in NL and patients with CH (Table 2; Fig. 4b).

Evaluation of the FGA, FGB, and FGG expression in the sera of patients with HCC. (A) Serum protein concentration of FGA, FGB, and FGG in the test cohort as measured by ELISA. Statistically significant differences were determined using unpaired Student’s t-test. (B) Serum protein concentrations of FGA, FGB, and FGG according to the mUICC stages in the validation cohort as measured by ELISA. Statistically significant differences were determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (C) The AUC values of serum FGA, FGB, and FGG compared to that of the serum AFP for the evaluation of their diagnostic power in HCC. Left: AUC for discriminating patients with all-stage HCC, mUICCI/II, and mUICC I. Right: P-values for each AUC analysis. (D) AUC values of serum FGA, FGB, and FGG compared to that of the serum AFP for diagnosing HCC in the high-risk group (CH/LC) and HCC subgroups. Left: AUC for discriminating patients with all-stage HCC, mUICC I/II, and mUICC I from CH/LC. Right: P-values for each AUC analysis. (E) Positivity rates for AFP, FGA, FGB, and FGG in the patients according to the liver disease group. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

Next, ROC curve analysis was conducted to evaluate the diagnostic power of serum FGA, FGB, and FGG as noninvasive biomarkers for liver cancer and compare their diagnostic performance with that of serum AFP. The diagnostic effectiveness of AFP declined in the early stages of liver cancer, with AUC values of 0.716 (versus HCC), 0.682 (versus mUICC I/II), and 0.653 (versus mUICC I), whereas FGA, FGB, and FGG showed stable diagnostic performances across the various disease stages (Fig. 4c). Specifically, FGA showed a statistically significant diagnostic performance across all the stages of liver cancer, with AUC values over 0.8, indicating a superior diagnostic performance compared to that of AFP. FGB exhibited a statistically significant diagnostic performance in the early-stage liver cancer (mUICC I/II), exhibiting a diagnostic performance comparable to that of AFP in very early-stage liver cancer (mUICC I). Though FGG showed a statistically significant diagnostic performance in all stages of liver cancer, its AUC value decreased compared to FGA and FGB, rendering it a less effective diagnostic marker.

Consequently, ROC analysis was conducted to compare the groups having a high risk of liver cancer (CH and LC) with the liver cancer groups. Serum AFP levels showed a decrease in their diagnostic performance from the normal versus liver cancer group (AUC = 0.716), and CH/LC versus liver cancer group (AUC = 0.604). Except for mUICC I, serum FGA maintained AUC values > 0.8; thus, it was considered as the best stand-alone diagnostic marker for liver cancer. Serum FGB maintained AUC values > 0.7; despite the decrease in its value in the early-stage liver cancer, it presented as a potential diagnostic marker. FGG showed the lowest diagnostic performance, with a decrease in its AUC values in the early-stage liver cancer (Fig. 4d).

By specifying marker-specific cutoff values (AFP ≥ 20 ng/mL, FGA ≤ 565.2762 ng/mL, FGB ≤ 51.7183 ng/mL, and FGG ≤ 67.999 ng/mL) and evaluating the positivity rates for AFP, FGA, FGB, and FGG in each disease group, varying rates of positivity were observed. In the NL group, the positivity rates were 0%, 3%, 20%, and 70% for AFP, FGA, FGB, and FGG, respectively. In the CH and LC groups, AFP showed relatively high positivity, whereas FGA showed lower positivity rates in high-risk conditions than AFP. FGB exhibited relatively higher positivity rates in the mUICC I-IV groups and showed promising diagnostic rates as an early-stage liver cancer biomarker. Interestingly, FGG showed high positivity rates across all liver disease states, suggesting its limited utility as a diagnostic marker (Fig. 4e).

Diagnostic validity of biomarker panels combining fibrinogen family and AFP

To identify an optimal biomarker panel for liver cancer diagnosis, we analyzed various combinations of AFP with FGA, FGB, and FGG. Initially, binary logistic regression was performed to evaluate dual-marker combinations. The combination of FGA + FGB exhibited the highest diagnostic performance across all stages of liver cancer, with an AUC of 0.900 for overall liver cancer, 0.901 for mUICC I, and 0.876 for mUICC I/II (Fig. 5a, left panels; Tables S6 and S7). When comparing each combination in the high-risk groups of CH/LC against the stages of liver cancer, the FGA + FGB combination maintained high diagnostic performance with an AUC value > 0.85 despite the observed decrease in diagnostic performance from the non-liver cancer model versus the liver cancer model (Fig. 5a, right panels and Tables S6 and S7).

Identification of fibrinogen family and AFP combinations and diagnostic validity of biomarkers. (A) AUCs of dual marker combinations for non-tumor (NT) versus HCC subgroups (left). AUCs of dual marker combination for high-risk group (CH/LC) versus HCC subgroups (right). (B) AUCs of triplet marker combinations for non-tumor (NT) versus HCC subgroups (left). AUCs of triplet marker combination for high-risk group (CH/LC) versus HCC subgroups (right). (C) Analysis of individual and combined marker positivity rates in 158 patients with HCC. (D) Correlation between the FGA, FGB, and FGG levels and liver functional markers.

Further analysis of triplet marker combinations revealed that the AFP + FGA + FGB combination showed the highest diagnostic performance with an AUC value of 0.916 for all liver cancer groups. Moreover, the FGA + FGB + FGG combination presented the highest AUC value of 0.907 for mUICC I/II and 0.882 for mUICC I (Fig. 5b, left panels and Tables S6 and S8). In the high-risk CH/LC group, triplet marker analysis of pairwise AUC comparisons showed that the AFP + FGA + FGB combination had the best diagnostic performance, with an AUC value of 0.900 for overall liver cancer, 0.888 for mUICC I, and 0.854 for mUICC I/II (Fig. 5b, right panels and Tables S6 and S8).

When evaluating the sensitivity and specificity of each combination, the cutoff values for the triplet marker combination of AFP + FGA + FGB had the highest diagnostic power. However, there was no significant difference in their diagnostic performance when compared with the dual-marker combination of FGA + FGB (Table S9). As previously mentioned, FGG exhibited high positivity rates across all liver disease stages, including HCC. This complicates its use as an exclusive marker of liver cancer, supporting the decision to use a combination of FGA and FGB as a more specific diagnostic tool (Fig. 5c).

To further validate the utility of the proposed biomarker combinations, we conducted 240 pairwise comparisons of ROC curves between single markers and their respective dual or triplet combinations across all diagnostic categories. Among these, 177 comparisons (73.75%) demonstrated statistically significant improvement (P < 0.05), indicating that combinatorial use of biomarkers provided substantial gains in diagnostic accuracy. In particular, AFP was included in 60 comparisons, and 52 of them (86.7%) showed significant improvement when combined with fibrinogen-related markers. FGA, FGB, and FGG also showed significant improvements in 48.3%, 65.0%, and 95.0% of comparisons, respectively. These data support the robustness of our combinatory approach and suggest that specific multi-marker panels may outperform individual biomarkers in both early- and late-stage HCC. A complete summary of these comparisons is provided in Table S10.Correlation analysis between FGA, FGB, FGG, and liver function markers did not reveal a statistically significant correlation between FGA and FGB. However, FGG displayed a modest positive correlation with the AST levels at 0.20, which was considered less significant compared to the stronger positive correlation of 0.36 between AFP and AST (Fig. 5d and Table S11). Therefore, the FGA, FGB, and FGG levels were not significantly influenced by liver function, suggesting their viability as independent biomarkers for clinical use.

Profiling fibrinogen family distribution in the HCC tumor microenvironment

To understand the expression patterns of fibrinogen in the context of HCC and its tumor microenvironment, we conducted immune infiltration analysis using TIMER 2.0 on the TCGA liver cancer dataset. Notably, a strong negative Spearman’s correlation between the fibrinogen family and MDSCs, specifically in HCC, implies an association. (Fig. 6a and Tables S12 and S13). This correlation was quantitatively supported by the Spearman’s correlation coefficients and P-values for the fibrinogen family members: FGA (Rho = -0.472; P = 1.42e-20), FGB (Rho= -0.403; P = 6.15e-15), and FGG (Rho=-0.415; P = 8.74e-16), indicating statistically significant inverse relationships with MDSCs (Table S14). Subsequently, cells from patients with HCC were grouped according to their lineage into malignant cells, T cells, B cells, tumor-associated macrophages, cancer-associated fibroblasts, tumor endothelial cells, and MDSCs; this was facilitated by the expression of lineage-specific marker genes (Fig. 6b). Upon investigating the distribution of the fibrinogen family members across the different cells, we observed that their expression was particularly decreased in the MDSC group (Fig. 6c). Considering the negative correlation identified in the results of TIMER 2.0, the expression of the top 100 genes in 504 MDSCs was examined. FGA, FGB, and FGG exhibited similar trends where they were expressed as either positive or negative values in MDSCs, and were categorized into three major clusters (Figure S3A, S3B and Fig. 6d). An analysis using EnrichR against MSigDB was performed to further investigate the genes that were altered in cells with reduced fibrinogen expression. The analysis revealed that the interferon response ranked highest in all three cases which suggests that the expression of the fibrinogen family could play a role in regulating the interferon signaling pathways (Fig. 6e and Table S15). Furthermore, single-sample GSEA revealed that the genes related to the regular biological functions of fibrinogen with respect to coagulation, hypoxia, and KRAS signaling were enriched in the cells displaying increased fibrinogen expression (Figure S3C). Conversely, interferon enrichment was observed in cells with decreased fibrinogen expression, highlighting the importance of the interferon response to fibrinogen (Fig. 6f).

Investigation of fibrinogen expression in the HCC tumor microenvironment. (A) Immune cell infiltration analysis using TIMER 2.0 (http://timer.comp-genomics.org/timer/). Correlation analysis of fibrinogen family expression with the tumor purity and MDSC cells in TCGA_LIHC. (B) UMAP of immune-associated and malignant cells colored according to the cell types analyzed using 50,023 cells from 25 patients with HCC. TAMs, tumor-associated macrophages; TECs, tumor endothelial cells; CAFs, cancer-associated fibroblasts; Tregs, regulatory T cells; MDSCs, myeloid-derived suppressor cells. (C) Violin plots of cell-type specific FGA, FGB, and FGG expression. (D) UMAP plot of FGA, FGB, and FGG expression across the MDSCs colored according to the cell clusters. (E) The top 10 pathways analyzed by GSEA with fibrinogen-associated genes. (F) Biological and functional pathway analysis with the low expressed fibrinogen cells showing interferon alpha and gamma response performed using GSEA.

Discussion

Fibrinogen, a crucial plasma glycoprotein involved in blood clotting and tissue repair, is primarily synthesized in the liver and regulated at the transcriptional and translational levels. This ensures a steady fibrinogen supply, which is essential for hemostasis and response to injury or inflammation29. Its production, exclusive to the liver, is controlled by transcription factors targeting upstream gene sequences that facilitate its expression in hepatocytes30,31,32. Observations from the TCGA-Pan-Cancer dataset al.so support this selective expression, which is further influenced by hormonal and cytokine signals such as dexamethasone and IL-6, which enhance fibrinogen output in the liver33,34. These findings highlight the significance of fibrinogen proteins in liver pathology and their capacity to serve as biomarkers of liver health and disease progression.

Despite the varying reports on fibrinogen protein expression in liver cancer, a deeper investigation into its role and potential as a biomarker is imperative. For instance, Dong et al. reported the upregulation of fibrinogen chains in small extracellular vesicles from patients with HCC, suggesting a link with disease progression15. Another group reported that FGA was significantly elevated in the plasma of patients with HCC through proteomic analysis which was further supported by ELISA35. Moreover, Zhang et al. reported increased FGB expression in liver disease pathology, indicating its association with poor recurrence-free survival in patients with HBV-related HCC36.

Likewise, many research groups have suggested increased fibrinogen expression in such cases, whereas others have suggested its decreased expression16,37. This divergence of findings points to the complexity of the role of fibrinogen in HCC, indicating the need for further research to clarify its expression patterns, implications for liver disease, and potential use as a biomarker for HCC.

ELISA revealed significantly reduced serum levels of FGA, FGB, and FGG in patients with liver cancer compared to healthy controls, a trend consistently observed across our datasets. Notably, FGA and FGB individually demonstrated higher diagnostic accuracies than AFP, with FGA displaying exceptional performance across all cancer stages. Although FGG was downregulated, its early-stage diagnostic capability did not exceed AFP’s. This suggests that measuring FGA and FGB in serum may offer a promising noninvasive approach for early detection of liver cancer, consistent with their liver-specific expression patterns (Figure S4).

Nonetheless, our study has certain limitations that warrant consideration. Because the cohort predominantly originated from a single institution, its demographic and clinical variability may not fully capture the complexity of HCC in broader populations. Furthermore, chronic liver diseases or concurrent therapies, such as antiviral treatment, could influence fibrinogen gene expression. In addition, although our findings highlight a downregulation of FGA and FGB in HCC, other studies have reported elevated fibrinogen levels and a correlation with poor prognosis, underscoring the heterogeneity of fibrinogen dysregulation across different patient cohorts17,38,39,40,41. These divergent observations will require larger, multi-center investigations that span diverse etiologies and disease stages, ideally supported by standardized protocols for fibrinogen measurement and clinical data collection. Such efforts would help clarify the precise role of FGA and FGB in HCC progression and further validate their clinical utility in diverse patient settings. Moreover, the variability in FGA and FGB levels suggests that different HCC subtypes may emerge according to whether these genes are suppressed or retained, potentially reflecting distinct immune profiles or oncogenic pathways17,42,43.

To expand upon the diagnostic significance of these biomarkers, we compared the performance of all single markers and their combinations across diverse clinical scenarios. These analyses consistently revealed that combinatory panels—especially AFP + FGA + FGB and FGA + FGB + FGG—offered improved diagnostic accuracy over individual markers, even in early-stage HCC. Statistical comparisons showed that many of these multi-marker strategies significantly outperformed single-marker approaches, reinforcing the clinical relevance of integrating fibrinogen-related markers to overcome the known sensitivity and specificity challenges of AFP.

In parallel with their diagnostic utility, our findings suggest that fibrinogen genes may also possess prognostic relevance. Specifically, decreased fibrinogen correlated negatively with MDSCs, which are known to promote immune evasion. This implies a more immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, potentially accelerating HCC progression. Of note, this observation differs from our earlier work showing that SF3B4, an oncogenic driver, positively correlated with MDSCs21. Such contrasting relationships among tumor-associated factors underscore the complexity of immune regulation in HCC. Clinically, evaluating FGA and FGB expression at diagnosis could thus inform not only early detection but also tumor aggressiveness, offering a practical complement to AFP and PIVKA-II. The combination of fibrinogen-based assays and established markers may be particularly beneficial for high-risk patients requiring stringent surveillance and individualized therapies.

Conclusion

FGA and FGB show promise as non-invasive biomarkers for HCC, offering enhanced diagnostic accuracy compared to AFP. Their consistent downregulation across various HCC stages and their association with the tumor microenvironment suggest they may play a significant role in HCC pathogenesis.

Data availability

All data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AFP:

-

α-fetoprotein

- ADJ:

-

Adjacent

- ALT:

-

Alanine aminotransferase

- ANOVA:

-

One-way analysis of variance

- AST:

-

Aspartate aminotransferase

- AUC:

-

Area under curve

- aHCC:

-

Advanced hepatocellular carcinoma

- cDNA:

-

Complementary deoxyribo nucleic acid

- CH:

-

Chronic hepatitis

- CHOL:

-

Cholangiocarcinoma

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CLICK:

-

CLuster Identication via Connectivity Kernels

- DFS:

-

Disease-free survival

- DN:

-

Dysplastic nodule

- early HCC:

-

Early staged hepatocellular carcinoma

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FGA:

-

Fibrinogen alpha chain

- FGB:

-

Fibrinogen beta chain

- FGG:

-

Fibrinogen gamma chain

- GAPDH:

-

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GSEA:

-

Gene set enrichment analysis

- HBV:

-

Hepatitis B virus

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HCCDB 2.0:

-

Hepatocellular Carcinoma Expression DataBase 2.0

- HCV:

-

Hepatitis C virus

- HMBS:

-

Hydroxymethylbilane synthase

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- INR:

-

International normalized ratio

- LC:

-

Liver cirrhosis

- LIHC:

-

Liver hepatocellular carcinoma

- MDSC:

-

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells

- MSigDB:

-

Molecular Signatures Database

- mUICC:

-

Modified Union for International Cancer Control

- NAFLD:

-

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- NL:

-

Normal liver

- NT:

-

Non-tumor

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- P:

-

Patient

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- PIVKA-II:

-

Prothrombin-induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II

- qRT-PCR:

-

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- RNA-seq:

-

RNA-sequencing

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristics

- scRNA-seq:

-

Single-cell RNA-sequencing

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- T:

-

Tumor tissue

- TCGA:

-

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- TIMER 2.0:

-

Tumor Immune Estimation Resource 2.0

- TPM:

-

Transcripts per million

- TSG:

-

Tumor suppressor gene

- UMAP:

-

Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection

References

Llovet, J. M. et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 7, 6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-020-00240-3 (2021).

Huang, D. Q., Mathurin, P., Cortez-Pinto, H. & Loomba, R. Global epidemiology of alcohol-associated cirrhosis and HCC: trends, projections and risk factors. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 20, 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-022-00688-6 (2023).

Sanyal, A. J., Yoon, S. K. & Lencioni, R. The etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma and consequences for treatment. Oncologist 15 (Suppl 4), 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2010-S4-14 (2010).

Kang, I. et al. Hepatitis B virus X protein promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by regulating SOCS1. BMB Rep. 55, 220–225. https://doi.org/10.5483/BMBRep.2022.55.5.157 (2022).

Rumgay, H. et al. Global burden of primary liver cancer in 2020 and predictions to 2040. J. Hepatol. 77, 1598–1606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2022.08.021 (2022).

Viggiani, V. et al. Protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II (PIVKA-II) specifically increased in Italian hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 51, 1257–1262. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365521.2016.1183705 (2016).

Simurda, T. et al. Genetic variants in the FGB and FGG genes mapping in the beta and gamma nodules of the fibrinogen molecule in congenital quantitative fibrinogen disorders associated with a thrombotic phenotype. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 2563. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21134616 (2020).

Kattula, S., Byrnes, J. R. & Wolberg, A. S. Fibrinogen and fibrin in hemostasis and thrombosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc Biol. 37, e13–e21. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.308564 (2017).

Mosesson, M. W. Fibrinogen and fibrin structure and functions. J. Thromb. Haemost. 3, 1894–1904. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01365.x (2005).

Perez, R. L. & Roman, J. Fibrin enhances the expression of IL-1 beta by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Implications in pulmonary inflammation. J. Immunol. 154, 1879–1887 (1995).

Hsieh, J. Y. et al. Differential regulation of macrophage inflammatory activation by fibrin and fibrinogen. Acta Biomater. 47, 14–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2016.09.024 (2017).

Litvinov, R. I. Fibrin opens the gate for leukocytes in the endothelium. Thromb. Res. 162, 101–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2017.12.006 (2018).

Ny, L. et al. The plasminogen receptor, Plg-R(KT), plays a role in inflammation and fibrinolysis during cutaneous wound healing in mice. Cell. Death Dis. 11, 1054. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-020-03230-1 (2020).

Zhang, Y. & Xiao, G. Prognostic significance of the ratio of fibrinogen and albumin in human malignancies: a meta-analysis. Cancer Manag Res. 11, 3381–3393. https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S198419 (2019).

Dong, W. et al. Proteomic analysis of small extracellular vesicles from the plasma of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Surg. Oncol. 20, 387. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-022-02849-y (2022).

Zhao, L. et al. Serum-Derived Exosomal proteins as potential candidate biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma. ACS Omega. 6, 827–835. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.0c05408 (2021).

Wu, X. et al. Fibrinogen and tumors. Front. Oncol. 14, 1393599. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2024.1393599 (2024).

Kim, H. S. et al. Tumor endothelial Cells-Associated integrin Alpha-6 as a promising biomarker for early detection and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 15, 2563. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15164156 (2023).

Shen, Q. et al. Barrier to autointegration factor 1, procollagen-lysine, 2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase 3, and splicing factor 3b subunit 4 as early-stage cancer decision markers and drivers of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 67, 1360–1377. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29606 (2018).

Eun, J. W. et al. Cancer-associated fibroblast-derived secreted phosphoprotein 1 contributes to resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma to Sorafenib and lenvatinib. Cancer Commun. (Lond). 43, 455–479. https://doi.org/10.1002/cac2.12414 (2023).

Son, J. A. et al. Circulating small extracellular vesicle-derived splicing factor 3b subunit 4 as a non-invasive diagnostic biomarker of early hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 42, 288. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-023-02867-y (2023).

Ahn, H. R. et al. Hypomethylation-mediated upregulation of the WASF2 promoter region correlates with poor clinical outcomes in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 41, 158. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-022-02365-7 (2022).

Kim, H. S. et al. ADAR1-dependent miR-3144-3p editing simultaneously induces MSI2 expression and suppresses SLC38A4 expression in liver cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 55, 95–107. https://doi.org/10.1038/s12276-022-00916-8 (2023).

Ma, L. et al. Single-cell atlas of tumor cell evolution in response to therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J. Hepatol. 75, 1397–1408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2021.06.028 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Identification of a tumour immune barrier in the HCC microenvironment that determines the efficacy of immunotherapy. J. Hepatol. 78, 770–782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2023.01.011 (2023).

Li, T. et al. TIMER2.0 for analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, W509–W514. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa407 (2020).

Li, T. et al. A web server for comprehensive analysis of Tumor-Infiltrating immune cells. Cancer Res. 77, e108–e110. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0307 (2017).

Li, B. et al. Comprehensive analyses of tumor immunity: implications for cancer immunotherapy. Genome Biol. 17, 174. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-016-1028-7 (2016).

Pieters, M. & Wolberg, A. S. Fibrinogen and fibrin: an illustrated review. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost. 3, 161–172. https://doi.org/10.1002/rth2.12191 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Orphan nuclear receptor errgamma is a key regulator of human fibrinogen gene expression. PLoS One. 12, e0182141. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182141 (2017).

Fish, R. J. & Neerman-Arbez, M. Fibrinogen gene regulation. Thromb. Haemost. 108, 419–426. https://doi.org/10.1160/TH12-04-0273 (2012).

Zhou, Z., Xu, M. J. & Gao, B. Hepatocytes: a key cell type for innate immunity. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 13, 301–315. https://doi.org/10.1038/cmi.2015.97 (2016).

Duan, H. O. & Simpson-Haidaris, P. J. Functional analysis of Interleukin 6 response elements (IL-6REs) on the human gamma-fibrinogen promoter: binding of hepatic Stat3 correlates negatively with transactivation potential of type II IL-6REs. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 41270–41281. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M304210200 (2003).

Duan, H. O. & Simpson-Haidaris, P. J. Cell type-specific differential induction of the human gamma-fibrinogen promoter by interleukin-6. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 12451–12457. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M600294200 (2006).

Ferrin, G. et al. Plasma protein biomarkers of hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV-infected alcoholic patients with cirrhosis. PLoS One. 10, e0118527. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118527 (2015).

Zhang, Y., Chen, X., Cao, Y. & Yang, Z. C8B in complement and coagulation cascades signaling pathway is a predictor for survival in HBV-Related hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Cancer Manag Res. 13, 3503–3515. https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S302917 (2021).

Li, M. et al. Down-regulation of RBP4 indicates a poor prognosis and correlates with immune cell infiltration in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biosci. Rep. 41, 236. https://doi.org/10.1042/BSR20210328 (2021).

Kinoshita, A. et al. Elevated plasma fibrinogen levels are associated with a poor prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology 85, 269–277. https://doi.org/10.1159/000355502 (2013).

Liu, Z. et al. Fibrinogen and D-dimer levels elevate in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: high pretreatment fibrinogen levels predict poor outcomes. Hepatol. Res. 47, 1108–1117. https://doi.org/10.1111/hepr.12848 (2017).

Huang, G. et al. Prognostic value of plasma fibrinogen in hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Cancer Manag Res. 10, 5027–5041. https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S175780 (2018).

Zhu, W. L., Fan, B. L., Liu, D. L. & Zhu, W. X. Abnormal expression of fibrinogen gamma (FGG) and plasma level of fibrinogen in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 29, 2531–2534 (2009).

Han, X. et al. FGA influences invasion and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma through the PI3K/AKT pathway. Aging (Albany NY). 16, 12806–12819. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.206011 (2024).

Qian, X. et al. Preoperative fibrinogen is associated with the clinical survival of primary liver cancer patients and promotes hepatoma metastasis via the PTEN/AKT/mTOR pathway. Heliyon 9, e16696. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e16696 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The biospecimens for this study were provided by the Ajou University Human Bio-Resource Bank, a member of the Korea Biobank Network, which is supported by the Ministry of Health and Welfare.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute, funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (HR21C1003 and RS-2023-KH136690), the Bio and Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation, funded by the Korean government (Ministry of Science and ICT) (NRF-2022R1A2C2092422 and RS-2023-00210847), and the National IT Industry Promotion Agency (S0252-21-1001) grant. This work was also supported by the intramural research fund of Ajou University Medical Center (M2019C046000069).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JWE, SSK, SHJ and HSK made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the present study. HSK, JYC, MK and SHJ performed the in vitro experiments. GOB, WP and JEH acquired and analyzed the data. MGY, J-YJ, SSK and JWE interpreted all the datasets in the present study. HSK, JYC, HJC and JWE drafted the initial manuscript and critically revised it for important intellectual content. JYC, SSK and JWE confirmed the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

All experiments were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ajou University Hospital (AJOUIRB-KSP-2019-417, AJOUIRB-EX-2022-389 and AJOUIRB-EX-2024-332). Informed consent was waived due to patients’ anonymous data by the Institutional Review Board of Ajou University Hospital.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, H.S., Choi, J.Y., Jang, S.H. et al. Fibrinogen alpha and beta chains as non-invasive predictors of hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Sci Rep 15, 42459 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26639-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26639-0