Abstract

Salinity and heavy metals significantly impact plant growth and development. However, mangroves demonstrate remarkable tolerance to these stresses. This study focuses on tracking superoxide dismutase (SOD), a key enzyme responsible for neutralizing superoxide anions. Gene expression analysis revealed that the genes encoding CuZnSOD (AmSOD1) and MnSOD are upregulated in Avicennia marina seedlings exposed to salt and lead stress. To investigate the protein-level expression of these isoforms, CuZnSOD and MnSOD (AmSOD2) from A. marina were heterologously expressed, purified, and used to produce specific antibodies in rabbits. These antibodies successfully distinguished between the two isoforms. Using 2D gel electrophoresis, western blotting combined with mass spectrometry, AmSOD1 was identified as two distinct spots with different molecular weights. Notably, the intensity of the high-molecular-weight spot increased in the leaves of A. marina seedlings during the early stages of salt and lead exposure, while the low-molecular-weight spot became more pronounced at later stages. AmSOD2 appeared as a single spot whose intensity increased at various time points in response to salt and lead, compared to controls. Protein extracts from the leaves displayed enhanced SOD activity under salt and lead stress. Additionally, Escherichia coli strains expressing AmSOD1 and AmSOD2 further confirmed the functional activity of these isoforms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Marine water pollution with various environmental pollutants has become one of the most critical global problems. Aquatic ecosystems are widely exposed to heavy metal pollution from elements such as lead, mercury, vanadium, and cobalt1,2. While some heavy metals are essential trace elements for living organisms, higher concentrations can cause severe poisoning due to their persistence, toxicity, non-biodegradable nature, oxidative stress, bio accumulative properties, and biomagnification along food chains3,4,5. Furthermore, the presence of heavy metals in water profoundly affects micro-animals, which are a primary food source for other animals. The accumulation and magnification of these metals in living organisms can lead to poisoning, destabilization of water ecosystems, significant threats to public health, and long-term impacts on entire ecosystems6,7,8.

Treating industrial wastewater often requires complex technologies that can be prohibitively expensive. Recently, phytoremediation has been investigated as a favorable method for treating soils contaminated with heavy metals9. This technology uses plants to purify pollutants from the environment and is effective, cost-efficient, and eco-friendly10.

Avicennia marina, which is known as grey mangrove, is classified in the plant family Acanthaceae11. A. marina can be regarded as compatible halophytes that grow in saline water conditions12,13. Although mangrove ecosystems receive pollutants from sources such as industrial activities, agricultural drainage, and urban runoff, they possess a great tolerance for heavy metal pollution14,15,16. Avicennian species are considered to have enhanced abilities for metal accumulation and tolerance in comparison to other mangrove species8,17.

Mangroves employ a range of strategies to cope with stress, such as specialized morphological and anatomical adaptations, efficient osmoregulation, optimized water usage, mechanisms for salt secretion and exclusion, salt accumulation, and regulation at the molecular level18,19,20. However, concerning both salt and heavy metals, it has been well documented that mangroves possess a strong antioxidant system and contain protein chelators that accumulate heavy metals21,22.

In response to salinity and the presence of heavy metals, the concentration of reactive oxygen species (ROS) increases in the plant cells. To maintain ROS balance, three antioxidant enzymes—superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GPX)—and a non-enzymatic component, glutathione (GSH), form the first line of antioxidant defense23,24,25,26,27,28,29. The enzyme SOD is a key enzyme that converts O2•− to H2O2, and the resulting H2O2 can be reduced by CAT, GPX, and GSH30.

In plants, SODs can be divided into three types based on their metal ions: copper/zinc-containing SOD (CuZnSOD), iron-containing SOD (FeSOD), and manganese-containing SOD (MnSOD)31. CuZnSODs are commonly found in the cytosol as well as the chloroplast. FeSODs, which are not present in animal cells, can be found in chloroplasts, and MnSODs can be found in mitochondria, chloroplasts, and peroxisomes32,33,34.

Despite the importance of understanding the molecular antioxidant mechanisms in A. marina, research efforts have so far been limited to mRNA expression analysis of genes encoding antioxidant enzymes. Consequently, gaps remain in our understanding of their expression at the protein level. In this study, we produced and purified recombinant forms of AmCuZnSOD (AmSOD1) and AmMnSOD (AmSOD2), enabling the production of specific primary antibodies for each isoform. Using western blot analysis and 2D gel electrophoresis, we examined the presence of AmSOD1 and AmSOD2 proteins in the leaves of seedlings grown in soil containing either lead or NaCl at different time points. For comparison, real-time PCR was performed to analyze gene expression in the same samples. Additionally, we conducted functional characterization using SOD assays and investigated the tolerance of engineered bacteria producing His-AmSOD1 and His-AmSOD2 in response to salt and lead as a toxic heavy metal.

Results

Production of antibody and evaluation of their specificity

SDS-PAGE of cell extracts from strains R-AmSOD1 and R-tAmSOD2 (without the N-terminal mitochondrial signal peptide) showed prominent polypeptide bands of 19 kDa and 26.8 kDa, respectively, corresponding to the expected theoretical molecular weights of His-AmSOD1 and His-tAmSOD2 (Fig. 1A). These bands were not observed in the control strain carrying the empty pET28a vector. Purification of the recombinant His-AmSOD1 and His-tAmSOD2 from the soluble fraction was performed using nickel affinity chromatography, yielding 6 mg/L and 30 mg/L of purified protein, respectively. The quality of the purification was evaluated by SDS-PAGE analysis. A single, clear band at the expected molecular weight of the target protein would indicate high purity and successful purification (Fig. 1B).

SDS-PAGE analysis, Purification and titration curve of produced antibodies. (A) Soluble protein extracted from R-tAmSOD2 (lane 1), and R-AmSOD1 (lane 2) and control strain (lane 3) after 4 h induction with IPTG. (B) SDS-PAGE analysis for confirmation of quality of His-AmSOD1 (lanes 1–4) and His-tAmSOD2 (lanes 5–8) after purification with affinity chromatography. (C) Titration curve of produced antibodies against recombinant and pure His-AmSOD1 and His-tAmSOD2 using ElISA. (D) Determination of specificity of produced antibody using western blotting.

After dialysis, the purified His-AmSOD1 and His-tAmSOD2 were individually injected into rabbits. The sera were harvested, serially diluted, and added to wells coated with His-AmSOD1 and His-tAmSOD2. Using an HRP-secondary antibody and TMB as a substrate, a curve of absorbance at 405 nm versus the serial dilutions of the antibody was plotted (Fig. 1C). The curves showed that absorbance for the negative control was much lower than that in the main wells with immunized serum. However, as the dilution increased, the absorbance decreased as expected. In the antibody serial dilutions between 1:50 to 1:1000, the absorbance in wells with antibodies was almost three times that of the corresponding well in the negative control. This ratio was 1.7 at a dilution of 1:5000 and was almost similar at a dilution of 1:10000 (1:10000 is not shown in Fig. 1C). On the other hand, the absorbance in the wells with antibody added at dilutions less than 1:500 seemed to be saturated, as the absorbance in serial dilutions 1:50, 1:100, and 1:500 was almost similar. Therefore, the dilution of 1:1000 was selected for the western blot analysis of SODs in the plant samples.

The discrimination potential of the antibodies was evaluated by western blot (Fig. 1D) and Supplementary material (Fig. S1). Since different types of SOD isoforms have been documented in plants, it is crucial that each antibody distinguishes between the different isoforms. As shown in Fig. 1D, the serum from rabbits immunized with His-AmSOD1 detected His-AmSOD1 but not His-tAmSOD2. Conversely, the serum from rabbits immunized with His-tAmSOD2 detected His-tAmSOD2 but not His-AmSOD1. These results show that the produced antibodies are specific for AmSOD1 and AmSOD2.

Gene expression analysis of SOD isoforms

The expression of both genes AmSOD1 and AmSOD2 in the leaves of A. marina seedlings treated with NaCl was significantly higher than in the leaves of untreated plants (control) at various time points (6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h). While the expression of these genes in the control samples did not change over time, the expression of both genes increased up to 24 h in the treated samples (Fig. 2A). Then, the expression of AmSOD1 began to decrease until 72 h, whereas the expression of AmSOD2 decreased at 48 h compared to 24 h and then remained constant until 72 h. At 24 h, the expression of AmSOD1 was twice that of its corresponding control, while the expression of AmSOD2 was 2.5 times that of its corresponding control sample.

Real-Time PCR analysis of gene AmSOD1 and AmSOD2 in the leaves of A. marina in response to (A) NaCl, (B) Pb(NO3)2 (C) NaCl + Pb(NO3)2 in different time points after treatment (6, 12, 18, 24, 48 and 72 h). Expression level is shown as a value relative to that in control sample (plant with no metal treatments). Each histogram represents the mean ± standard deviation (SD) obtained from three independent biological replications. The statistical significance of the difference was determined by LSD test. Differences between treatments were considered significant when p ≤ 0.05.

In seedlings treated with Pb(NO3)2, the expression of AmSOD1 and AmSOD2 was significantly higher than in untreated seedlings at various time points (Fig. 2B). While the expression of these genes remained unchanged over time in the controls, the expression of AmSOD1 increased up to 48 h and then decreased until 72 h. However, the expression of AmSOD2 increased up to 24 h, then remained almost constant up to 48 h, and decreased at 72 h. At 24 h, the expression of AmSOD1 was twice that of its corresponding control, while the expression of AmSOD2 was 2.5-fold greater than that of its corresponding control sample.

In seedlings treated with both NaCl and Pb(NO3)2, the expression of genes encoding AmSOD1 and AmSOD2 increased up to 24 h and then remained constant up to 72 h. The expression of AmSOD1 increased in 2.3-fold that of its corresponding control at 24–72 h. This ratio was also 2.3-fold greater for AmSOD2 (Fig. 2C).

Protein appearance pattern in the seedlings in response to stress

In western blot analysis as shown in Fig. 3 and supplementary material (Figs. S2 and S3), AmSOD1 appeared in two bands in both control and treated plants. The intensity of the higher molecular weight (HMW) band was greater than that of the lower molecular weight (LMW) band in all samples. Additionally, the intensity of both HMW and LMW bands was significantly higher in treated plants compared to control samples.

While the intensity of the AmSOD1 HMW band in control samples remained almost constant over time (as determined by Image J), the intensity of the LMW band was low at 6 h, increased up to 12 h, and then decreased until 72 h. In comparison, AmSOD2 appeared in one band with very low intensity in control samples.

In seedlings treated with NaCl, the intensity of the AmSOD1 HMW band was almost similar to that in control at various time points (Fig. 3A). However, the intensity of the AmSOD1 LMW band was enhanced by 1.2–1.5 times that of the corresponding band in control at various time points. The intensity of AmSOD2 was significantly higher in treated plants compared to control, remaining constant over time in treated plants.

In seedlings treated with Pb(NO3)2, the intensity of the AmSOD1 HMW band was enhanced compared to the corresponding bands at various time points. The enhancement ratio between 6 and 24 h was twice the intensity of the corresponding bands in control samples, increasing to 2.4-fold at 48 and 72 h. The LMW band was low at 6 h, but in seedlings treated with Pb(NO3)2 for 6 h, the LMW band appeared sharply, doubling the intensity of the control. While the HMW band intensity remained constant over time, the LMW band intensity increased up to 72 h (Fig. 3B). The intensity ratios in seedlings treated with Pb(NO3)2 for 6–72 h ranged from 2 to 2.8 times those of the corresponding bands in control samples. The intensity of AmSOD2 was significantly higher in treated plants compared to control (about 2-fold), remaining constant over time in treated plants.

In plants treated with “NaCl + Pb(NO3)2”, the intensity of the AmSOD1 HMW band at 6 h was 1.2-fold that of the corresponding band in control, increasing to 3-fold by 72 h (Fig. 3C). The LMW band intensity between 6 and 24 h was almost similar to that in control samples, but increased by about 1.8-fold at 48 and 72 h compared to control. The intensity of the AmSOD2 band increased over time up to 72 h.

Due to the detection of two bands for AmSOD1 in western blot, AmSOD1 and AmSOD2 were analyzed in extracted proteins from the leaves of seedlings treated with NaCl for 48 h using 2D-gel electrophoresis. As shown in Fig. 4A and, spots 32 with MW (Da)/pI 15266.26/5.7 and spot 33 with 15200.34/ 5.5 were identified as the same isoform of Cu/ZnAmSOD1, Accession No. ACA50531). The spot 43 with MW (Da)/pI 221825.5/6.5 was identified an MnSOD (AmSOD1, Accession No. AAN15216). According to the amino acid sequence of AmSOD2 in NCBI, the theoretical MW (Da)/pI of the full protein is predicted as 25105.66/7.1. However, the approximate MW (Da)/pI of the protein in this spot on the 2D gel was 23000/6.0 which is more corresponds to truncated form of tAmSOD236, confirming that AmSOD2 lacks the transit peptide after targeting to the mitochondrion. In 2D western blot while of treated seedlings by NaCl for 48 h two spots 32 and 33 was detected by antibody produced against AmSOD1, However Spot 34 was the only spot that was appeared when the prepared antibody against AmSOD2 (Fig. 4B).

SOD forms in the protein extracted from A. marina seedlings leaves (No treatment) visualized on 2D gels. (A) Sections of 2D gels from 10 to 30 kDa and pI 4–7 are shown. The positions of SOD spots are indicated by arrows. (B) Identification of SOD by Western blotting in the A. marina seedlings treated with NaCL for 48 h. (C) Tracking AmSOD1 forms (HMW- and LMW-spots) on 2D-western blot of control (c) and treated seedlings with NaCL (N), Pb(NO3)2 (P) and NaCl + Pb(NO3)2 (N + P) after 6, 24 and 48 h.

HMW-AmSOD1 spot appeared in 2D-western blot analysis of control seedlings and those treated with NaCl, Pb(NO3)2, and a combination of NaCl and Pb(NO3)2 for 6 and 12 h. (Fig. 4B). However, no corresponding LMW-AmSOD1 spot was detected at these early time points. With prolonged treatment, both the HMW-AmSOD1 spot and an additional LMW-AmSOD1 spot were observed. This suggests a time-dependent modulation of AmSOD1 isoforms, which likely helps manage oxidative stress during extended exposure to salt and lead toxicity.

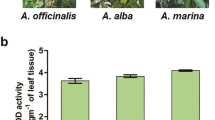

SOD assay in the seedlings treated with NaCl and Pb(NO3)2

The results of the SOD assay indicated that in the control plants, SOD activity remained constant over time (Fig. 5). However, in treated plants, SOD activity was enhanced compared to the control. After 6 h, the SOD activities in response to NaCl, Pb(NO3)2, and “NaCl + Pb(NO3)2” treatments were 1.4, 2.6, and 3.1 times the corresponding control sample, respectively. The activity in plants treated with NaCl and “NaCl + Pb(NO3)2” increased up to 24 h, with the ratio to the corresponding control reaching 1.87 for NaCl and 3.3 for “NaCl + Pb(NO3)2” After 24 h, the activity decreased significantly at 48 and 72 h. In the leaves of seedlings treated with Pb(NO3)2, the activity increased compared to the control. However, the amount of activity remained constant until 12 h, then significantly decreased at 24 h, and remained almost constant at 48 and 72 h.

Tolerance of bacteria expressing SODs

The cell densities of strains R-AmSOD1 and R-AmSOD2 as well as control decreased by increasing the concentration of NaCl. Whereas, the concentration of 500 mM NaCl inhibited completely the growth of control strain, the cell density of strain R-AmSOD1 and R-AmSOD2 were 0.8 and 0.48 respectively (Fig. 6A). Although the growth of R-AmSOD2 in the concentration of 550 mM was completely inhibited the same as control (OD600 = 0.18) but still the cell density of R-AmSOD2 was 0.3.

Determination of tolerance of strains R-AmSOD1 and R-AmSOD2 as well as control when the cells were exposed to various concentrations of (A) NaCl or (B) Pb(NO3)2. Each histogram represents the mean ± standard deviation (SD) obtained from three independent biological replications. The statistical significance of the difference was determined by LSD test. Differences between treatments were considered significant when p ≤ 0.05.

In the medium containing Pb(NO3)2, the growth of control strain was not affected by the presence of Pb(NO3)2 up to 4 mM (Fig. 6B). However, by increasing the concentration of Pb(NO3)2 the growth of control strain decreased. Whereas the cell density of control strain at concentrations of 8 mM reached to 0.2 this amount was 0.4 and 0.63 for R-AmSOD1 and AmSOD2, respectively.

Discussion

Differential expression of AmSOD1 and AmSOD2 under abiotic stress

The present study investigated the gene expression patterns of two superoxide dismutase (SOD) isoforms, AmSOD1 (encoding CuZnSOD) and AmSOD2 (encoding MnSOD), in A. marina seedlings under NaCl, Pb(NO3)2, and combined NaCl and Pb(NO3)2 treatments. Under NaCl treatment, both AmSOD1 and AmSOD2 exhibited a significant increase in expression, peaking at 24 h, with AmSOD1 and AmSOD2 showing 2- and 2.5-fold higher expression than their respective controls. This upregulation is consistent with the role of SODs as key antioxidants mitigating reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated during salt stress. Similar responses have been observed in other plant species. For instance, in cucumber (Cucumis sativus), multiple CuZnSOD and MnSOD genes were upregulated in response to salinity, with expression patterns varying across tissues and time points, suggesting a coordinated antioxidant response35. The peak expression at 24 h in A. marina, followed by a decline in AmSOD1 and stabilization in AmSOD2, may reflect a dynamic regulation where CuZnSOD responds more transiently, while MnSOD maintains a sustained response, possibly due to its mitochondrial localization, which is critical for ROS detoxification in organelles under prolonged stress. This is supported by studies on Alexandrium pacificum, where MnSOD expression remained elevated longer than CuZnSOD under heavy metal stress, indicating differential regulation based on subcellular roles36.

In response to Pb(NO3)2 treatment, AmSOD1 expression peaked at 48 h, while AmSOD2 peaked earlier at 24 h and then stabilized before declining at 72 h. The 2- and 2.5-fold increases in AmSOD1 and AmSOD2 expression, respectively, at 24 h suggest a rapid activation of the antioxidant defense system to counter Pb2+-induced oxidative stress. These findings align with previous research on Alexandrium pacificum, where Pb2+ exposure significantly upregulated ApCuZnSOD (≥ 6.5 times after 6 h) and ApMnSOD, correlating with increased ROS production36. The delayed peak in AmSOD1 expression compared to AmSOD2 in A. marina may indicate that cytosolic CuZnSOD plays a secondary role in Pb2+ stress response, following initial mitochondrial protection by MnSOD. This differential timing is consistent with studies on Cucumis sativus, where CuZnSODs and MnSODs exhibited distinct expression kinetics under heavy metal stress, reflecting their specific roles in cellular compartments35.

The combined NaCl and Pb(NO3)2 treatment resulted in a sustained 2.3-fold upregulation of both AmSOD1 and AmSOD2 from 24 to 72 h, suggesting a synergistic effect of these stressors on SOD gene expression. This sustained response contrasts with the transient peaks observed under individual treatments, indicating that combined stresses may overwhelm the antioxidant system, necessitating prolonged SOD activity. Similar synergistic effects have been reported in the marine polychaete Perinereis nuntia, where combined metal exposures led to sustained SOD expression compared to single-metal treatments37. The consistent expression levels of AmSOD1 and AmSOD2 under combined stress suggest that A. marina employs a robust antioxidant strategy to cope with multiple stressors, a critical adaptation for its survival in saline and metal-contaminated mangrove environments.

Phylogenetic analyses from previous studies provide context for the evolutionary conservation of SOD isoforms. In Alexandrium pacificum, ApMnSOD clustered with green algae and plants, while ApCuZnSOD was more closely related to dinoflagellates, indicating divergent evolutionary paths for these isoforms36. Similarly, in cucumber, MnSOD (was localized to mitochondria, consistent with AmSOD2’s role, while CuZnSODs were cytosolic or chloroplast35. These findings suggest that the differential expression patterns observed in A. marina may be linked to conserved structural and functional roles of SODs across species, with MnSOD primarily protecting mitochondria and CuZnSOD addressing.

Antibody specificity and Stress-Induced modulation of AmSOD isoforms

The successful production and purification of recombinant His-AmSOD1 and His-tAmSOD2, with yields of 6 mg/L and 30 mg/L respectively, align with reports on recombinant protein expression in E. coli using nickel affinity chromatography38. The high specificity of the antibodies raised against His-AmSOD1 and His-tAmSOD2 is critical, as cross-reactivity among SOD isoforms has been noted in earlier studies39.

The detection of two AmSOD1 bands (HMW and LMW) in western blot analysis suggests post-translational modifications or alternative isoforms, as reported in Arabidopsis under oxidative stress40. Their study attributed HMW bands to glycosylated Cu/Zn-SOD forms, which may explain the stable HMW band intensity in our control and treated samples. The enhanced intensity of the AmSOD1 LMW band under NaCl and Pb(NO3)2 stress, particularly at later time points, aligns with increased expression of low-molecular-weight SOD isoforms in rice under heavy metal stress41. This suggests that the LMW AmSOD1 isoform may enhance antioxidant capacity, possibly through improved catalytic efficiency or altered localization42.

The significant upregulation of AmSOD2 under NaCl and Pb(NO3)2 stress, with a consistent 2-fold increase compared to controls, contrasts with transient MnSOD induction reported in wheat43. Our results indicate stable AmSOD2 expression over 72 h, suggesting a sustained role in Amaranthus seedlings. The MW/pI shift of AmSOD2 to 23,000/6.0, consistent with the truncated form36, supports findings that post-translational cleavage enhances SOD stability in mitochondria44.

The time-dependent appearance of the LMW-AmSOD1 spot in 2D-western blot analysis under prolonged stress suggests dynamic regulation of AmSOD1 isoforms, similar to alternative splicing or proteolytic processing observed in Glycine max under salt stress45. The amplified AmSOD1 HMW expression (up to 3-fold at 72 h) under combined NaCl and Pb(NO3)2 stress indicates synergistic effects on ROS production, contrasting with suppressed SOD expression under combined stressors in other species46.

Our findings highlight isoform-specific responses of AmSOD1 and AmSOD2 to salt and heavy metal stress, supported by highly specific antibodies. Compared to prior studies, our work underscores sustained mitochondrial SOD expression and dynamic AmSOD1 isoform regulation, providing a foundation for further research into their roles in plant stress tolerance. Future studies should investigate the molecular mechanisms driving differential AmSOD1 isoform regulation and their interactions with other antioxidant enzymes under combined stress.

SOD activity under salt and heavy metal stress

Elevated SOD activity in A. marina seedlings under NaCl, Pb(NO3)2, and combined NaCl + Pb(NO3)2 stress aligns with a 1.5-fold SOD increase in Oryza sativa under salt stress47. Stronger activity under combined stressors, peaking at 24 h, exceeds a 2-fold increase in Triticum aestivum48, suggesting robust ROS scavenging in Amaranthus. Activity decline after 24 h, despite sustained AmSOD2 expression in earlier western blot data49, contrasts with prolonged SOD activity in Glycine max50, indicating possible post-translational regulation. Stable Pb(NO3)2-induced activity until 12 h, followed by a decline, aligns with heavy metal responses in Zea mays51 but suggests longer residual activity in A. marina.

Bacterial tolerance conferred by AmSOD isoforms

Enhanced tolerance of E. coli strains expressing R-AmSOD1 and R-AmSOD2 to NaCl and Pb(NO3)2 stress aligns with improved salt tolerance in SOD-overexpressing bacteria52. Superior cell density of R-AmSOD1 under high NaCl concentrations, compared to R-AmSOD2, suggests greater stability of the Cu/Zn-SOD structure under ionic stress, consistent with findings in E. coli expressing plant Cu/Zn-SODs. In contrast, R-AmSOD2’s higher tolerance to Pb(NO3)2 mirrors enhanced heavy metal resistance in MnSOD-overexpressing bacteria53, likely due to its mitochondrial role in ROS detoxification.

Conclusion

This study highlights the crucial role of superoxide dismutase (SOD) isoforms in the oxidative stress response of A. marina seedlings under salinity and heavy metal stress. The upregulation of CuZnSOD and MnSOD genes in response to salt and lead, as revealed by gene expression analysis, underscores their importance in mitigating the damaging effects of reactive oxygen species (ROS). The identification and characterization of protein-level responses through western blotting and mass spectrometry provide deeper insights into the dynamic behavior of SOD isoforms during stress exposure.

The dual-spot appearance of AmSOD1, with its high-molecular-weight (HMW) and low-molecular-weight (LMW) forms, suggests post-translational modifications or complex formation, likely reflecting adaptive mechanisms to stress. The early predominance of the HMW spot, followed by the later appearance of the LMW spot, indicates a time-dependent modulation of SOD activity designed to manage oxidative damage during prolonged exposure to salt and lead stress. Similarly, the increased intensity of the single-spot AmSOD2 at various time points highlights its consistent role in maintaining ROS homeostasis. However, further analysis, involving more advanced MS techniques, will be required to explain the appearance of AmSOD1 in two spots.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

Seedlings of A. marina was prepared by the Hormozgan Province Agricultural Jihad Organization, located in Bandar Abbas, Iran Iran (GPS coordinates: 27.1832° N, 56.2666° E). Seedlings with eight leaves were transplanted into sand-filled trays in a greenhouse maintained at 35 ± 2 °C under a 14 h/10 h light/dark photoperiod for one month, with daily watering. For treatment with lead and NaCl the seedlings were watered by [250 mM NaCl, 0 mg/L Pb(NO3)2], [0 mM NaCl, 250 mg/L Pb(NO3)2], and [250 mM NaCl, 250 mg/L Pb(NO3)2. Control seedlings were treated with water without any additional treatment. Two milligrams of leaves were harvested from each treatment after 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h of treatment.

Real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the leaves of A. marina using the High Pure RNA Isolation Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Penzberg, Germany). The extracted RNA was treated with RNase-Free DNase (Thermo fisher Scientific, USA) to remove the DNA contamination. The first strand of cDNA was synthesized using AMV reverse transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), oligo-dT primer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and extracted total RNA as template according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. For PCR reaction, the specific primers were designed using software Invitrogen Oligo PerfectTM Designer (http://tools.invitrogen.com/content.cfm). The sequences of forward and reverse primers for the gene AmSOD1 were 5´GGTGCTCCAGAAGATGAGGT3´ and 5´TCCGCCCTTTCCAAGATC AT3´, respectively and the sequence of forward and reverse primers for the gene AmSOD2 were 5´ATCTTGCTCCTGTCCGTGAA3´ and 5´GTGGATCCTGGTTTGCAGTG3´, respectively.

Real-time PCR was performed as described previously with slight changes54,55. Reactions were performed with an initial 15 min denaturation at 95 °C followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 S, 57 °C for 30 S, 72 °C for 30 S, followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The expression levels were calculated by 2^(−ΔΔCt) method55 with A. marina actin gene (CD777208.1) as reference gene. Calculation was based on two technical and three biological replicates.

Production and purification of recombinant proteins

The genes encoding AmSOD1 and AmSOD2 were previously cloned into the pET28a vector between the EcoRI and HindIII sites and transformed into E. coli Rosetta (DE3), resulting in the strains R-AmSOD1 and R-AmSOD2 34,36. In this study, the transgenic strains R-AmSOD1 and R-AmSOD2 were cultured in a growth medium. Protein expression was induced with IPTG, and proteins were extracted from harvested cells as previously described34,36. To confirm protein expression, the extracted proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE37 and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 38.

Purification was performs as described previously49,54 using His-Trap HP column (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) pre-equilibrated with loading buffer (10 mM imidazole, 500 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0). The purified fractions were combined and placed into 12 kDa molecular weight cutoff cellulose dialysis tubes (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Munich, Germany). They were dialyzed overnight at 4 °C against 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) to eliminate imidazole and other salts. Protein concentrations were measured using the Beer-Lambert method by assessing UV absorbance at 205 nm, with an extinction coefficient of 31.

Animal immunization against AmSOD1 and AmSOD2

Purified recombinant His-AmSOD1 and His-tAmSOD2 were diluted in PBS buffer to a concentration of 0.8 mg/ml and used as the antigen. The antigens were individually injected into female rabbits as follow. The first injection was performed subcutaneously using 2 ml antigen mixed with 2 ml complete Freund’s adjuvant (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Munich, Germany). The second immunization was conducted subcutaneously using 1.5 ml antigen mixed with equal volume of incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Munich, Germany) two weeks later. The third injection was administrated as similar as the second immunization at one week interval and finally, the immunization was completed four weeks later by intramuscular injection of 2 ml antigen. Upon completion of the immunization process, 700 µL of blood was collected from the ear vein, and serum was separated by centrifugation and stored at −20 °C until use. The serum from a rabbit that was not immunized with antigen was used as a control in the ELISA experiments.

Titration assay

For the titration assay of each antibody, each purified antigen was diluted in coating buffer (0.05 M bicarbonate, pH 9.6) to a final concentration of 5 µg/ml. A total of 100 µL of the antigen was added to each well of a 96-well ELISA plate, and the plate was incubated overnight at 4 °C. Following the incubation, the wells were washed three times with 0.01 M PBS with 0.05% Tween-20 (PBS-T pH 7.5). To block non-specific binding, 100 µL of blocking buffer (5% skimmed milk in PBS) was added to each well, and the plate was incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The wells were washed three times with PBS-T in continue. The serum was serially diluted in blocking buffer to concentrations of 1:100, 1:500, 1:1000, 1:5000, and 1:10000. A total of 100 µL of each serum dilution was added to the appropriate wells in triplicate. The plate was incubated for 2 h at room temperature to allow antibody binding to the antigen. The wells were then washed three times with PBS-T to remove unbound antibodies. The HRP-conjugated secondary antibody was diluted 1:5000 in blocking buffer. A total of 100 µL of the diluted secondary antibody was added to each well, and the plate was incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The wells were washed three times with PBS-T to remove unbound secondary antibody. To each well, 100 µL of TMB substrate solution was added. The plate was incubated in the dark for 15 min at room temperature for color development. The enzymatic reaction was stopped by addition of 50 µL of 1 M H2SO4 to each well. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader. In addition, the coated plates with addition of various dilution of unimmunized serum named was used as negative control.

Determining the specificity of antibodies using Western blotting

To evaluation of specificity of produced antibodies, the purified AmSOD1 and AmSOD2 were run onto SDS-PAGE. Western blotting was performed as described previously56 with slightly changes. Proteins were transferred from SDS-PAGE to a PVDF membrane (Roche Diagnostics, Penzberg, Germany). The blots were blocked overnight in blocking buffer containing 5% (w/v) skimmed milk in TBST (10 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20). Each immunized serum for His-AmSOD1 and His-tAmSOD2 was diluted 1:1000 in TBST. The antigen–antibody interaction was performed at room temperature for 1 h. Following this, the blots were washed three times for 10 min each with TBST, then once for 15 min with TBS (containing 10 mM NaCl, 25 Tris–HCl, pH 7.5). Subsequently, the blots were incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (GenScript), diluted 1:2000 in TBST, as the secondary antibody. The membranes were washed again as previously described. Finally, the immunoblots were developed using 0.5 mg mL− 1 diaminobenzidine in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7) containing 0.22% H2O2.

Protein extraction from leaves and Western blot analysis

The leaves of A. marina were removed from storage at −80 °C, and 250 mg of plant leaves were ground into a fine powder in a pre-cooled mortar and pestle in the presence of liquid nitrogen. The powdered tissue was transferred into a 2 mL tube. 0.8 mL of phenol saturated with Tris (pH 8.0) with an equal volume of ice-cold SDS buffer (30% sucrose, 2% SDS, 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and 5% β-mercaptoethanol) was added to the powder. The mixture was vortexed for 30 s and incubated on ice for 5 min. The mixture was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 3 min at 4 °C, and the upper layer containing the phenol phase was transferred into a new tube. A 5-fold volume of pre-cooled precipitation buffer (0.1 M ammonium acetate in methanol) was added to the phenol phase, mixed, and incubated at −20 °C overnight. The protein pellet was harvested by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C, and the upper phase was removed. The harvested pellet was rinsed twice with 0.1 M ammonium acetate in methanol and twice with 80% chilled acetone, and it was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min each time. The pellet was dried at room temperature and stored at −20 °C until use.

The dried pellet was resuspended in 500 µL of buffer containing 60 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0) and 2% SDS. Protein concentration was then determined using the BCA assay with BSA as the standard. For SDS-PAGE and Western blotting, 12 µL of protein (6 µg) was mixed with 3 µL of 5× SDS loading buffer and loaded onto a 12% SDS-PAGE gel. Western blotting was performed as described in the previous section. However, the membranes were cut horizontally prior to antibody hybridization in order to probe for multiple targets of different molecular weights from the same blot. Each membrane section was incubated with the relevant primary and secondary antibodies separately.

2D-gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry

Aliquots containing 100 mg of protein extracts from treated leaves were precipitated using TCA in acetone and then redissolved in a reswelling buffer consisting of 7 M urea, 2 M thiourea, 2% (v/v) CHAPS, 0.5% (v/v) IPG ampholytes (pH 4–7, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), 1.2% (v/v) Destreak reagent (hydroxyethyl disulfide), and a small amount of bromophenol blue. The first-dimension isoelectric focusing was performed with 18-cm linear IPG strips (pI 4–7, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) using an IPGphor system (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden). Following this, the IPG strips were equilibrated according to the protocol outlined in57 and subjected to second-dimension electrophoresis on Excel SDS XL (18 × 24 cm) gradient gels 12–14% (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) using the Multiphor II system (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden). The gels were stained with either silver nitrate58 or colloidal Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-25059.

For identification, spots cut out from Coomassie-stained gels were in-gel digested with trypsin (Promega) as described57. Peptides were micro-purified60 and eluted directly onto the MALDI target in 5 mg/mL a-cyano-hydroxy-cinnamic acid in 70% acetonitrile and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. An Ultraflex II MALDI-TOF-TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker-Daltonics) was used in positive ion reflector mode and spectra were analyzed using FlexAnalysis software (Bruker-Daltonics). Peptide mass data were searched against the NCBI nonredundant database using Biotools (Bruker Daltonics) software and Mascot (Matrix Science) with the following parameters: monoisotopic mass tolerance, 80 ppm; allowed missed cleavages, 1; allowed modifications, arbamidomethylation of Cys (global) and oxidation of Met (partial).

SOD assay in the extracted proteins from the leaves

The leaves of the plant were removed from storage at −80 °C, and 100 mg of plant leaves were ground into a powder in a pre-cooled mortar and pestle in the presence of liquid nitrogen. The powdered sample was transferred into a 1.5 mL tube, and 500 µL of cold extraction buffer (1 M sucrose, 0.2 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, and 0.056 M β-mercaptoethanol) was added. The mixture was homogenized. The samples were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant, which contained the protein, was transferred to a new tube and centrifuged again. After centrifugation, the supernatant was transferred to a new tube as the final protein sample. The protein sample was stored at −20 °C. The concentration of protein was determined by Bradford assay and BSA as standard61.

After extracting protein from the leaves, SOD activity was determined using a commercially available kit, Cayman’s Superoxide dismutase assay kit (Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Tetrazolium salt was utilized to detect superoxide radicals generated by xanthine oxidase and hypoxanthine, which react to form a yellow formazan dye. Briefly, hypoxanthine and xanthine oxidase were used to generate free radicals, which in turn react with tetrazolium salt to form a formazan dye with absorbance at 440–460 nm. One unit of SOD activity is defined as the amount that causes a 50% inhibition of the rate of tetrazolium reduction under the assay conditions62. The obtained units were normalized by dividing by the amount of soluble protein extracted from the leaves.

Tolerance of the engineered strain to different stress conditions

Cell growth and survival studies were conducted under various abiotic stress conditions, adapting previously established methods with modifications63. The experiments aimed to evaluate the impact of introducing His-AmSOD1 and His-tAmSOD2 on the stress tolerance of E. coli cells. Initially, single colonies from both recombinant and control E. coli strains were cultured in 10 mL of LB medium containing antibiotics and incubated at 37 °C with shaking at 200 rpm for 16 h. These precultures were then used to inoculate fresh 50 mL LB cultures (supplemented with antibiotics) at an initial OD600 of 0.08. The cultures were grown under the same conditions until OD600 reached 0.4, at which point recombinant SOD isoform expression was induced by adding 0.1 mM IPTG. Following induction, the cultures were incubated at 37 °C and 200 rpm for an additional 4 h. After induction, the cultures were diluted into fresh LB medium containing kanamycin (50 µg/mL) to an initial OD600 of 0.05. These were then distributed into 24-well plates (1 mL per well) supplemented with 0.1 mM IPTG. The cells were subjected to different stress treatments: (i) NaCl, 0, 100, 200, 300, 400, 450, 500, 550, 600, 650 mM; (ii) Ethanol, 0, 1, 2, 2.5, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8% (v/v); and (iii) H2O2, 0, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 4, 5, 6, 6.5, 7, 7.5, 8, 8.5, 9, 9.5, 10 mM and (iv) Pb(NO3)2. 3H2O, 0, 1, 1.5,2. 2.5, 3, 3.5, 4, 4.5, 5, 5.5, 6, 6.5, 7, 7.5 and 8 mM.

The growth and viability of the recombinant strains (R-AmSOD1 and R-AmSOD2) were assessed under these stress conditions and compared with the control strain. Growth in each well was measured after 16 h by recording the absorbance at OD600 using a microplate reader. All experiments were conducted independently in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

All data in this work are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) from three independent biological replications. The statistical significance of the difference was determined by LSD test. Differences between treatments were considered significant when p ≤ 0.05.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AmSOD1:

-

A. marina CuZnSOD

- AmSOD2:

-

A. marina MnSOD

- IPTG:

-

Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- HMW:

-

Higher Molecular Weight

- LMW:

-

Lower Molecular Weight

References

Jaishankar, M., Tseten, T., Anbalagan, N., Mathew, B. B. & Beeregowda, K. N. Toxicity, mechanism and health effects of some heavy metals. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 7, 60 (2014).

Gulati, R., Kour, A. & Sharma, P. Ecological impact of heavy metals on aquatic environment with reference to fish and human health. J. Appl. Nat. Sci. 14, 1471 (2022).

Briffa, J., Sinagra, E. & Blundell, R. Heavy metal pollution in the environment and their toxicological effects on humans. Heliyon 6, e04691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04691 (2020).

Mitra, S. et al. Impact of heavy metals on the environment and human health: Novel therapeutic insights to counter the toxicity. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 34, 101865. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksus.2022.101865 (2022).

Singh, V. et al. Toxic heavy metal ions contamination in water and their sustainable reduction by eco-friendly methods: Isotherms, thermodynamics and kinetics study. Sci. Rep. 14, 7595. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-58061-3 (2024).

Afzal, A. & Mahreen, N. Emerging insights into the impacts of heavy metals exposure on health, reproductive and productive performance of livestock. Front. Pharmacol. 15 https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2024.1375137 (2024).

Saravanan, P. et al. Comprehensive review on toxic heavy metals in the aquatic system: Sources, identification, treatment strategies, and health risk assessment. Environ. Res. 119440 (2024). (2024).

Zhang, L. D. et al. Inventory of cadmium-transporter genes in the root of Mangrove plant Avicennia marina under cadmium stress. J. Hazard. Mater. 459, 132321 (2023).

Sarwar, N. et al. Phytoremediation strategies for soils contaminated with heavy metals: Modifications and future perspectives. Chemosphere 171, 710–721 (2017).

Greipsson, S. Phytoremediation Nat. Educ. 3 (2011).

Krauss, K. W., McKee, K. L. & Feller, I. C. How Mangrove forests adjust to rising sea level. Front. Ecol. Environ. 5, 161–167 (2007).

Cheeseman, J., Herendeen, L., Cheeseman, A. & Clough, B. Photosynthesis and photoprotection in mangroves under field conditions. Plant. Cell. Environ. 20, 579–588 (1997).

Li, J. et al. Integrative analysis of transcriptome and metabolome reveal the differential tolerance mechanisms to low and high salinity in the roots of facultative halophyte avicennia Marina. Tree Physiol. 44, 43–160. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/tpae082 (2010). (2024).

Sarker, S., Masud-Ul‐Alam, M., Hossain, M. S., Rahman Chowdhury, S. & Sharifuzzaman, S. A review of bioturbation and sediment organic geochemistry in mangroves. Geol. J. 56, 2439–2450 (2021).

Wińska-Krysiak, M., Koropacka, K. B. & Gawronski, S. Determination of the tolerance of sunflower to lead-induced stress. J. Elementol. 20, 491–502. https://doi.org/10.5601/jelem.2014.19.4.721 (2015).

Ye, F., Huang, X., Zhang, D., Tian, L. & Zeng, Y. Distribution of heavy metals in sediments of the Pearl river Estuary, Southern china: Implications for sources and historical changes. J. Environ. Sci. 24, 579–588 (2012).

Jian, L., Chongling, Y., Daolin, D., Haoliang, L. & Jingchun, L. Accumulation and speciation of cd in Avicennia marina tissues. Int. J. Phytorem. 19, 1000–1006 (2017).

Fitzgerald, M. A., Orlovich, D. A. & Allaway, W. G. Evidence that abaxial leaf glands are the sites of salt secretion in leaves of the Mangrove Avicennia marina (Forsk.) Vierh. New. Phytol. 120, 1–7 (1992).

Parida, A. K. & Jha, B. Salt tolerance mechanisms in mangroves: A review. Trees 24, 199–217 (2010).

Waisel, Y., Eshel, A. & Agami, M. Salt balance of leaves of the Mangrove Avicennia marina. Physiol. Plant. 67, 67–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3054.1986.tb01264.x (2006).

Mishra, S. et al. Lead detoxification by coontail (Ceratophyllum demersum L.) involves induction of phytochelatins and antioxidant system in response to its accumulation. Chemosphere 65, 1027–1039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.03.033 (2006).

Peters, E. C., Gassman, N. J., Firman, J. C., Richmond, R. H. & Power, E. A. Ecotoxicology of tropical marine ecosystems. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 16, 12–40 (1997).

Jabeen, U., Abbasi, A. & Salim, A. Predicting the functionally distinct residues in the heme, cation, and substrate-binding sites of peroxidase from stress-tolerant Mangrove specie, Avicennia Marina. Cell. Stress Chaperones. 585–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12192-011-0269-3 (2011).

Asada, K. Production and scavenging of reactive oxygen species in chloroplasts and their functions. Plant. Physiol. 141, 391–396. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.106.082040 (2006).

Bowler, C. et al. Manganese superoxide dismutase can reduce cellular damage mediated by oxygen radicals in Transgenic plants. EMBO J. 10, 1723–1732. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07696.x (1991).

Wingsle, G. & HÄLlgren, J. E. Influence of SO2 and NO2 exposure on glutathione, superoxide dismutase and glutathione reductase activities in Scots pine needles. J. Exp. Bot. 44, 463–470. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/44.2.463 (1993).

Zhang, L. et al. Expressed sequence tags from a NaCl-treated Suaeda Salsa cDNA library. Gene 267, 193–200 (2001).

Jabeen, U., Abbasi, A. & Salim, A. Predicting the functionally distinct residues in the heme, cation, and substrate-binding sites of peroxidase from stress-tolerant Mangrove specie, Avicennia marina. Cell. Stress Chaperones. 16, 585–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12192-011-0269-3 (2011).

Jabeen, U., Abbasi, A. & Salim, A. Predicting the functionally distinct residues in the heme, cation, and substrate-binding sites of peroxidase from stress-tolerant Mangrove specie, Avicennia marina. Cell. Stress Chaperones. 16, 585–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12192-011-0269-3 (2011).

Halliwell, B. & Gutteridge, J. M. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine (Oxford University Press, 2015).

Zhao, H., Zhang, R., Yan, X. & Fan, K. Superoxide dismutase nanozymes: An emerging star for anti-oxidation. J. Mater. Chem. 9, 6939–6957 (2021).

Alscher, R. G., Erturk, N. & Heath, L. S. Role of superoxide dismutases (SODs) in controlling oxidative stress in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 53, 1331–1341. https://doi.org/10.1093/jexbot/53.372.1331 (2002).

Kanematsu, S., Okayasu, M. & Ueno, S. Atypical cytosol-localized Fe-superoxide dismutase in the moss pogonatum inflexum. Bull. Minamikyushu Univ. 3, 31 (2013).

Sen Raychaudhuri, S. & Deng, X. W. The role of superoxide dismutase in combating oxidative stress in higher plants. Bot. Rev. 66, 89–98 (2000).

Zhou, Y., Zhang, Y. & Wang, Y. Differential expression of superoxide dismutase isoforms in cucumber (Cucumis sativus) under salinity stress. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 115, 1–10 (2017).

Kim, H., Lee, J. & Park, J. Expression patterns of superoxide dismutase isoforms in alexandrium Pacificum under heavy metal stress. Mar. Environ. Res. 174, 105–112 (2022).

Won, E. J., Lee, J. H. & Kim, S. Y. Synergistic effects of combined metal exposures on superoxide dismutase expression in Perinereis Nuntia. Aquat. Toxicol. 210, 1–9 (2019).

Smith, J., Davis, R. & Wilson, T. Efficient purification of His-tagged proteins in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr Purif. 142, 34–40 (2018).

Lee, S., Kim, J. & Park, H. Challenges in antibody specificity for plant superoxide dismutase isoforms. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 1123–1130 (2015).

Garcia, R., Lopez, M. & Perez, J. Post-translational modifications of Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase in Arabidopsis under oxidative stress. Plant. Sci. 280, 78–85 (2019).

Zhang, H., Yang, L. & Wu, T. Low-molecular-weight superoxide dismutase isoforms in rice under heavy metal stress. J. Plant. Physiol. 258, 153–162 (2021).

Wang, Z., Liu, Q. & Zhao, X. Subcellular localization of superoxide dismutase isoforms under heavy metal stress. Plant. Cell. Rep. 41, 1345–1355 (2022).

Li, X., Zhang, Y. & Chen, Q. Transient induction of Mn superoxide dismutase in wheat under abiotic stress. Plant. Mol. Biol. 102, 89–98 (2020).

Chen, L., Wang, Y. & Zhang, H. Post-translational modifications of mitochondrial superoxide dismutases under stress conditions. Plant. Physiol. 170, 456–465 (2016).

Patel, M., Sharma, V. & Rao, P. Alternative splicing of superoxide dismutases in Glycine max under salt stress. Front. Plant. Sci. 14, 567–576 (2023).

Gupta, A., Singh, R. & Kumar, S. Combined stress effects on superoxide dismutase expression in plants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 165, 101–110 (2019).

Kumar, P., Sharma, V. & Rao, K. Antioxidant enzyme responses to salt stress in Oryza sativa. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 50, 321–329 (2012).

Sharma, A., Kumar, S. & Singh, R. Synergistic effects of combined stressors on antioxidant enzymes in Triticum aestivum. J. Plant. Physiol. 236, 78–86 (2019).

Abedi, H. & Shahpiri, A. Functional characterization of a manganese superoxide dismutase from Avicennia marina: Insights into its role in salt, hydrogen peroxide, and heavy metal tolerance. Sci. Rep. 14 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50851-5 (2024).

Patel, M., Sharma, V. & Rao, P. Prolonged salt stress enhances superoxide dismutase activity in Glycine max. Front. Plant. Sci. 12, 689–698 (2021).

Gupta, R., Singh, B. & Sharma, S. Heavy metal-induced superoxide dismutase activity in Zea mays. Environ. Exp. Bot. 70, 145–152 (2010).

Wang, Z., Liu, Q. & Zhao, X. Superoxide dismutase overexpression improves salt tolerance in Escherichia coli. J. Biotechnol. 230, 56–63 (2016).

Singh, R., Kumar, P. & Gupta, A. Mn superoxide dismutase overexpression enhances heavy metal tolerance in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 118, 1456–1465 (2021).

Fesharaki-Esfahani, M., Shahpiri, A. & Kazemi-Nasab, A. A highly efficient, thermo stable and broad pH adaptable copper-zinc super oxide dismutase (AmSOD1) mediates hydrogen peroxide tolerance in Avicennia Marina. Phytochemistry 187, 112766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2021.112766 (2021).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2–∆∆CT Method. Methods 25, 402–408, (2001). https://doi.org/10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Shahpiri, A., Talaei, N. & Finnie, C. Spatio-temporal appearance of α‐amylase and limit dextrinase in barley aleurone layer in response to gibberellic acid, abscisic acid and Salicylic acid. J. Sci. Food Agric. 95, 141–147 (2015).

Finnie, C., Melchior, S., Roepstorff, P. & Svensson, B. Proteome analysis of grain filling and seed maturation in barley. Plant. Physiol. 129, 1308–1319 (2002).

Heukeshoven, J. & Dernick, R. Improved silver staining procedure for fast staining in phastsystem development Unit. I. Staining of sodium Dodecyl sulfate gels. Electrophoresis 9, 28–32 (1988).

Candiano, G. et al. Blue silver: A very sensitive colloidal coomassie G-250 staining for proteome analysis. Electrophoresis 25, 1327–1333. https://doi.org/10.1002/elps.200305844 (2004).

Gobom, J., Nordhoff, E., Mirgorodskaya, E., Ekman, R. & Roepstorff, P. Sample purification and preparation technique based on nano-scale reversed‐phase columns for the sensitive analysis of complex peptide mixtures by matrix‐assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. J. Mass. Spectrom. 34, 105–116 (1999).

Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3 (1976).

Ukeda, H., Kawana, D., Maeda, S. & Sawamura, M. Spectrophotometric assay for superoxide dismutase based on the reduction of highly water-soluble tetrazolium salts by Xanthine-Xanthine oxidase. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 63, 485–488. https://doi.org/10.1271/bbb.63.485 (1999).

Gallo, G. et al. A hyperthermoactive-Cas9 editing tool reveals the role of a unique arsenite methyltransferase in the arsenic resistance system of thermus thermophilus HB27. mBio 12, e02813–02821 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MM: Validation, Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft. MZ: Investigation, Validation. MS: Validation, Investigation, Methodology. As: Validation, Data Curation, Writing – review and editing, Investigation, writing original draft, performed all the experiments in the lab and provided the data, table and figures; AS analyzed data and wrote the manuscript; AS: Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mahdavian, M., Shahpiri, A., Shamsara, M. et al. Tracking copper-zinc and manganese superoxide dismutase in Avicennia marina reveals time-dependent expression of SOD isoforms in response to salt and lead stress. Sci Rep 15, 42608 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26794-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-26794-4