Abstract

Hyperglycaemia, glycaemic variability and hypoglycaemia, are associated with adverse outcomes in the critically ill. In the cardiac surgical population, the relationship between these metrics and outcomes is poorly defined. We aimed to characterise the relationships between acute dysglycaemia, chronic hyperglycaemia and outcomes in a cardiac surgical population. Using the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV v1.0 (MIMIC IV-v1.0) database, we compiled a dataset of cardiac surgical patients from 2008 to 2019. Multivariable analysis was performed to assess the independent effect of glucose metrics on mortality while controlling for confounders. Prior hyperglycaemia was assessed by measurement of glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) pre-operatively. Of the 9132 patients included in the analysis, 27% had known diabetes and the prevalence of unrecognised diabetes was 11%. The mean, cumulative dose of hyperglycaemia and coefficient of variation of blood glucose level all increased significantly (P<0.001) with greater pre-operative HbA1c. Acute hyperglycaemia was strongly associated with mortality (OR 5.88, 95% CI, 3.03 to 10.6), although this effect was diminished by exposure to chronic hyperglycaemia (HbA1c ≥6.5%). Hypoglycaemia was strongly associated with mortality irrespective of premorbid glycaemic control. The findings indicate that chronic pre-operative hyperglycaemia attenuates the association between acute hyperglycaemia, glycaemic variability and mortality in the cardiac surgical population, but does not modify the mortality risk associated with hypoglycaemia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Perioperative dysglycaemia, including hyperglycaemia, increased glycaemic variability and hypoglycaemia are associated with harm in critically ill patients. Hyperglycaemia occurs frequently post cardiac surgery, even in patients not known to have diabetes or glucose intolerance, so-called stress induced hyperglycaemia (SIH)1,2. Observational data from the general Intensive Care Unit (ICU) population3, and in patients post cardiac surgery1, indicate that in patients without diabetes, markedly elevated blood glucose concentrations are associated with adverse outcomes. To avoid the detrimental effects of hyperglycaemia, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) Practice Guidelines recommend maintaining serum glucose levels ≤ 180 mg/dL (10 mmol/L)4 which is consistent with targets advised for the general ICU population5. However, observational studies in the general ICU population have consistently reported that the association between death and hyperglycaemia is attenuated or lost in patients with pre-existing diabetes and chronic hyperglycaemia3,6,7. However, a significant limitation of these studies is that cardiac surgical patients were excluded, or not reported as distinct subgroups.

The cardiac surgical population is discrete from the general ICU population, with a unique combination of physiological stressors impacting glucose metabolism. In comparison this group has an increased prevalence of poorly controlled type 2 diabetes and a reported incidence of SIH as high as 80%8,9. Moreover, the mortality rate post cardiac surgery is less than one-fifth of that observed in the general ICU population3,10.Therefore, this group may display alternative interactions between acute and chronic hyperglycaemia, and mortality.

Divergent evidence suggests the association between increased glycaemic variability and death may be attenuated or conversely magnified by chronic hyperglycaemia in the cardiac surgical population. Further investigation is needed to resolve this paradox and describe the relationship across the spectrum of glycaemic control. Observational studies report a moderately strong association between worse outcomes and increased glycaemic variability post coronary artery by-pass grafting (CABG) in patients both with and without diabetes11,12, but not post isolated cardiac valvular surgery13. Chronic hyperglycaemia has been reported to attenuate the association between death and glycaemic variability in a general ICU population14, whereas the opposite effect has been reported in a retrospective observational study of 1461 patients undergoing cardiac surgery11.

The historic standard of care for stress hyperglycaemia – intravenous insulin – inherently introduces the risk of iatrogenic hypoglycaemia. In the general ICU population, moderate hypoglycaemia occurs in almost half of the patients requiring intravenous insulin15. The risk of severe hypoglycaemia is greatest in those with pre-existing diabetes and chronic hyperglycaemia and is associated with up to a three-fold greater mortality in this cohort16. Up to one fifth of patients experience an episode of hypoglycaemia post cardiac surgery which is independently associated with morbidity and mortality8. However, the relationship between chronic hyperglycaemia, hypoglycaemia, and the association with mortality has not been reported in a cardiac surgical population.

We conducted this large retrospective observational study in a post-cardiac surgery population to characterize the interaction between metrics of acute dysglycaemia, chronic hyperglycaemia (predominantly in patients with type 2 diabetes) and outcome. Specifically, we aimed to explore if 1) chronic hyperglycaemia attenuates the association between acute hyperglycaemia and mortality, 2) chronic hyperglycaemia attenuates the association between increased glycaemic variability and mortality, 3) chronic hyperglycaemia impacts the association between hypoglycaemia and mortality.

Methods

Ethics

Access to the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV v1.0 (MIMIC IV-v1.0) database for research purposes was approved by the institutional review boards of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Cambridge, MA, USA) (number 2001-P-001699/14) and the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (number 0403000206). The study received exempt status by the Institutional Review Board at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and all data points were de-identified in accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA).

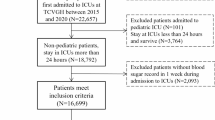

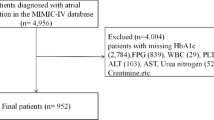

Study population

The MIMIC-IV database is a sequential, longitudinal, single-centre database comprising deidentified information relating to patients admitted to critical care units at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center17. The dataset includes over 70,000 critically ill patients admitted between 2008 and 2019, and includes comprehensive data on patient demographics, physiological parameters, laboratory results, and clinical outcomes, with a significant subset (12.5%) admitted post cardiac surgery. Criteria for inclusion were any index adult patient (age ≥18 years) who had procedural codes corresponding to one of the following: coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), valvular surgery or a combined graft and valve procedure. Excluded patients were those without a recorded glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), those with blood glucose levels (BGLs) in keeping with a diabetic emergency, a history of type 1 diabetes and those requiring other types of cardiac surgery. The following data were extracted; age, gender, body mass index (BMI), admission type, the first 24-h Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, co-morbidities (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), congestive heart failure (CCF), myocardial infarction (MI)), HbA1c, and all blood glucose measurements during the ICU admission. Diabetes was diagnosed as a patient with a current ICD-10-CM code for diabetes, those with prior insulin use or those with an HbA1c level ≥ 6.5% (48 mmol/mol) in the three months prior to their operation.

Primary outcome and glycaemic metrics

The primary outcome was hospital mortality. The relationships between glucose metrics and mortality were stratified by HbA1c bands of HbA1c <6.5% (48 mmol/mol), HbA1c 6.5–7.9% (48–63 mmol/mol), and HbA1c ≥ 8.0% (64 mmol/mol)18. Hyperglycaemia was analysed according to exposure to a time-weighted average dose, described subsequently as a cumulative hyperglycaemia dose. The cumulative hyperglycaemia dose was defined as cumulative Area Under the Curve of BGL values above 10mmol/L, divided by the ICU length of stay. This yields values in the natural units originally used to express blood glucose values (mmol/L)19. Glycaemic variability was analysed as the coefficient of variation (standard deviation/mean x 100%)14. Hypoglycaemia was defined as a blood glucose level of less than or equal to 3.89mmol/L.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are reported as median [interquartile range (IQR)] or mean (standard deviation(SD) and compared using Wilcoxon rank sum or Fischer’s exact test, as appropriate. Categorical variables are reported as percentages and compared using the Chi-squared test. Multivariable analysis was performed to assess the independent effect of different glucose metrics on mortality while controlling for confounders defined a priori as age, gender, admission type, BMI, T2DM, SOFA score, valvular surgery, CABG surgery, COPD and CKD. Group-by-continuous interaction effects between acute glycaemic metrics, glycaemia and mortality were assessed using marginal model predictive plots with 95% confidence interval bands. A P value of 0.05 was used for significance. All analyses were performed using R studio20.

Results

Within the study period, 9132 patients met inclusion criteria. There were 2608 females (29%) and the study population had a mean (SD) age of 67.4 (11.0) years, a mean BMI of 29.7 (5.8) kg/m2, a mean SOFA score of 5.5 (2.8), and a median [IQR] HbA1c of 5.9 (3.8–14.6.8.6) %. A total of 4698 (52%) patients were admitted for CABG surgery, 2299 (25 %) for valvular surgery, and 2168 (24%) for a combined procedure, of which 5132 (54 %) were admitted electively.

Stress-induced hyperglycaemia, unrecognised diabetes and clinical characteristics associated with chronic glycaemia

A total of 4613 patients (50%) had SIH, and 3659 (40%) experienced multiple episodes of hyperglycaemia. In patients without diabetes and those who had a HbA1c < 6.5%, the incidence of SIH was 17%. While 2502 (27%) patients had recognised diabetes, the prevalence of unrecognised diabetes (HbA1c ≥ 6.5% in the absence of a prior ICD-10 diagnosis) was 11%. The median (IQR) HbA1c for those with recognised diabetes was 6.9 (6.3–7.8.3.8)%. Baseline characteristics and outcome stratified by HbA1c level are presented in Table 1. Patients with a HbA1c ≥8% were younger with a higher BMI and were more likely to have chronic kidney disease, less likely to have an elective admission, and more likely to have CABG surgery.

Glucose metrics, acute glycaemia and chronic glycaemia

Domains of dysglycaemia are presented in Table 2. The median [IQR] number of blood glucose measurements increased with greater pre-operative HbA1c (< 6.5%, 28 [22 - 43]; 6.5 - 7.9%, 33 [24–55]; ≥ 8.0%, 38 [25–61]; P < 0.001. The mean blood glucose level, cumulative dose of hyperglycaemia, the number of hyperglycaemia events and coefficient of variation of blood glucose all increased significantly with greater pre-operative HbA1c. The number of hypoglycaemic events was less (P<0.001) in patients with an HbA1c < 6.5% compared to those with greater HbA1c.

Relationship between premorbid glycaemia, acute glycaemia and outcome

Of the patients with an HbA1c recorded, 108 (1.14%) died during the index hospital admission. Premorbid glycaemia was not independently associated with hospital mortality (P = 0.13). However, there were significant interaction effects between premorbid glycaemia, acute glycaemia, and hospital mortality (Table 3).

There was a significant interaction effect (P<0.001), such that cumulative dose of hyperglycaemia was strongly associated with increased hospital mortality in individuals without diabetes (OR 3.30, 95% CI, 1.69 to 5.88) and those with pre-morbid glycaemic control HbA1c < 6.5% (OR 5.88, 95% CI, 3.03 to 10.6). The cumulative dose of hyperglycaemia was not associated with mortality in patients with diabetes and an HbA1c >6.5% (OR 0.98, 95%CI 0.44 to 1.92). These interaction effects remained significant when adjusted for covariates (Supplementary, Table1). The number of hyperglycaemic events was associated with a modest increase in hospital mortality across all HbA1c subgroups (HbA1c <6.5%: OR 1.04, 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.05, HbA1c 6.5% - 7.9%: OR 1.04, 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.04, HbA1c ≥ 8.0%: OR 1.03, 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.05). This interaction effect was no longer significant for those with HbA1c >6.5% in the adjusted analysis (Supplementary, Table1). The number of hypoglycaemic episodes was strongly associated with hospital mortality across all HbA1c subgroups (HbA1c <6.5%: OR 1.19, 95% CI, 1.14 to 1.23, HbA1c 6.5% - 7.9%: OR 1.08, 95%CI, 1.04 to 1.12, HbA1c ≥ 8.0%: OR 1.09, 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.17) and this remained significant in the adjusted analyses, with the exception of the HbA1c ≥ 8.0% subgroup (Supplementary, Table1). Increasing glycaemic variability was strongly associated with hospital mortality, except in those with poor glycaemic control (HbA1c <6.5%: OR 1.09, 95% CI, 1.07 to 1.10, HbA1c 6.5% - 7.9%: OR 1.07, 95%CI, 1.03 to 1.11, HbA1c ≥ 8.0%: OR 0.99, 95% CI, 0.90 to 1.09). This interaction only remained significant for those with HbA1c <6.5% after adjusting for covariates (Supplementary, Table1).

Marginal models predicted a greater probability of in-hospital death in those with excellent chronic glycaemic control (HbA1c <6.5%) with increasing cumulative dose hyperglycaemia (P < 0.001), more frequent hyperglycaemia episodes (P < 0.001), and increasing glycaemic variability (P = 0.025) (Supplementary, Figure 1A-C). More frequent hypoglycaemic events were associated with an increased probability of in-hospital death independent of chronic glycaemic control (Supplementary, Figure 1D).

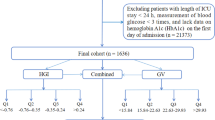

Marginal model predictions (with 95% confidence bands) for in-hospital death for pre-defined chronic glycaemia sub-groups: well controlled (HbA1c <6.5%), adequately controlled (HbA1c 6.5% - 7.9%), and poorly controlled (HbA1c ≥ 8.0%), for (A) Cumulative dose hyperglycaemia (B) Number of Hyperglycaemic events (C) Number of Hypoglycaemic events (D) Glycaemic variability (coefficient of variation).

Discussion

We aimed to show whether chronic hyperglycaemia affected the association between acute hyperglycaemia and death in the cardiac surgical population. In our single-centre retrospective study of cardiac surgical patients, the observations that SIH occurred in 50% of the population and that almost 40% of patients presenting for cardiac surgery had type 2 diabetes - about twice that observed in the general ICU population – are consistent with previous studies3,21. Chronic hyperglycaemia was not independently associated with increased hospital mortality. In contrast, the cumulative dose of hyperglycaemia, number of hyperglycaemic episodes and glycaemic variability were all associated with increased mortality in patients without diabetes and in those with good pre-operative glycaemic control, while no associations were evident in patients with diabetes and chronic pre-operative hyperglycaemia. Hypoglycaemia was strongly predictive of increased hospital mortality irrespective of premorbid glycaemic control.

Interpretation of previous studies examining the effect of chronic glycaemia on outcomes in the critically ill is compromised by their binary classification of diabetes. This dichotomous approach obviates the assessment of glycaemic control as a continuum and classifies patients with unrecognised diabetes incorrectly. By stratifying glycaemic control by pre-operative HbA1c, our study adds to the now persuasive evidence that the relationship between acute dysglycaemia and mortality is modulated by the degree of chronic hyperglycaemia14,18,22. The apparent protective effect of chronic hyperglycaemia may be due to adaptive changes in intracellular signalling. Chronic hyperglycaemia may create a conditioning effect through downregulation of glucose transporters that protects susceptible tissues from glucose toxicity during critical illness2. Supporting this concept, in a cohort study of over 4000 cardiac surgical patients, Greco et al found that patients without diabetes had worse outcomes with increasing glycaemia, while in those with insulin treated diabetes, improved outcomes were observed at higher glucose ranges1. Likewise, in critically ill individuals with coronary heart disease, Chen et al observed that those with poor chronic glycaemic control had a decreased association between acute hyperglycaemia and mortality23. This raises the provocative and somewhat paradoxical implication that antecedent poor glycaemic control may be protective.

Together these data provide a compelling argument for modifying glycaemic targets according to premorbid glycaemic control, allowing for a more liberal approach in those with chronic hyperglycaemia. This inference has been explored in the critically ill population and to a lesser extent the cardiac surgical population. The recent LUCID study was a multi-centre, open-labelled, parallel group randomised trial, comparing liberal (180–252mg/dL) to conventional (108-180mg/dL) glucose targets in critically ill patients with type 2 diabetes24. Of the 419 recruited patients, 185 (44%) had chronic hyperglycaemia (HbA1c ≥ 7%). While the liberal approach to blood glucose targets reduced incident hypoglycaemia and glycaemic variability it failed to improve patient-centred outcomes. Similarly, in a sequential period study Kar et al. compared liberal and conventional glucose targets in 83 critically ill patients with a HbA1c ≥ 7%25. There was a trend toward fewer episodes of moderate to severe hypoglycaemia with the liberal approach, without evidence of increased risk of infection25. Recently, a randomized control trial by Gunst, demonstrated a possible trend towards favourable outcomes from liberal glucose control in its large cardiac surgical subgroup who had similarly high rates of diabetes of nearly 45%21. Due to a lack of stratification of patients by HbA1c, the association between outcomes and chronic glycaemic control in this group remain unknown. More frequent episodes of severe hypoglycaemia in those randomized to tight control (HR 1.52, 95% CI, 0.97 to 2.39) may account for the difference in outcomes. Similarly, studies by Lazar26 and Desai27, in which the cohort was not stratified according to HbA1c, also demonstrated that a liberal approach to glycaemic control reduces the incidence of hypoglycaemia in cardiac surgical populations. Coupled with our findings that hypoglycaemic episodes were more common in those with a HbA1c ≥ 6.5%, and the recognised strong association between hypoglycaemia and mortality, a strategy utilising liberal targets that mitigates hypoglycaemia is intuitively appealing for cardiac surgical patients with pre-operative chronic hyperglycaemia. In the absence of continuous glucose monitoring devices, with hypoglycaemia alarms, as a standard-of-care, a liberal glycaemia target strategy presents a pragmatic option.

The evidence for harm from acute glycaemia in individuals not exposed to chronic hyperglycaemia makes a strong argument for personalising targets. The CONTROLLING study, a prospective randomised trial in 2075 general ICU patients was the first to compare conventional glycaemic control to a strategy of personalized glucose targets based on chronic glycaemia28. The study was stopped prematurely after interim-analyses indicated futility, with no difference in 90-day mortality between control and intervention groups (32.9% v 30.5%). Hypoglycaemia, of any severity, occurred twice as frequently in those randomised to personalised glucose targets, with a majority related to insulin administration. Less than one-third of the study population had diabetes, and those randomised to individualised treatment had reasonable glycaemic control with a median [IQR] HbA1c of 6.9 [6.4–8.2.4.2]28. However, the study was limited by its modest treatment separation between groups, and a lack of external validity to the cardiac surgical population.

Trials of liberal or individualised glucose control in the general ICU population may not be generalizable to the demographically distinct cardiac surgical population. We add to the evidence demonstrating a protective effect of chronic hyperglycaemia in attenuating the mortality risk associated with acute dysglycaemia. Given the lack of effect seen in large trials in the general ICU population with five-fold greater mortality rates, conventional randomized controlled trials with frequentist statistical analysis may not be appropriate to determine superiority of individualised glycaemic targets in the cardiac surgical population. Future study designs may improve their ability to show treatment effects by using glycaemia bundles-of-care, incorporating continuous glucose monitoring devices, hypoglycaemia alarms, and algorithm-driven insulin dosing. Such an approach would provide a higher degree of granularity on the time-weighted effects of hyperglycaemia, moderate, and severe hypoglycaemia, on outcomes.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study in a cardiac surgical population that demonstrates interactions between acute and chronic glycaemia and outcomes, by stratifying patients according to HbA1c. The large study population allowed assessment of these interactions despite the low mortality post cardiac surgery. Use of cumulative dose of hyperglycaemia allowed precision in describing the association between acute hyperglycaemia, chronic glycaemia and outcome by describing a time-weighted dose interaction. Importantly, this approach allowed separation of the assessment of the discrete interaction effects of the harm from hyperglycaemia independent of the known harms of hypoglycaemia. Furthermore, this index offers advantages over the Stress Hyperglycaemia Ratio (SHR) and Glycaemic Gap (GG), by not only capturing the admission blood glucose, which may not be elevated following elective cardiac surgery, but also incident hyperglycaemic episodes throughout the ICU admission, which the SHR and GG fail to address. The study is also strengthened by identifying those with diabetes precisely, using coding and admission HbA1c, a population demonstrated to be greater than one-third of those undergoing cardiac surgery. There are however limitations, the single-centre, retrospective design introduces bias and limits the generalisability of results. Variable frequency of intermittent blood glucose sampling measurements may have introduced inconsistencies in glucose metrics data. The use of coding likely appropriately excluded those with type 1 diabetes, but assumes all remaining patients had type 2 diabetes possibly misclassifying a small portion with pancreatic insufficiency. Our dataset does not record the use of, or the likely cessation of, medications commonly prescribed in this cohort, and which are of potential relevance on peri-operative mortality, including sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors and glucagon-like-peptide-1 receptor agonists, beta-agonists and other catecholamines, or corticosteroids. Furthermore, glucose metrics outside the ICU were not included in our dataset and our analyses do not account for this.

Conclusion

Chronic hyperglycaemia in the cardiac surgical population attenuates mortality risk associated with acute hyperglycaemia and glycaemic variability. The risks from hypoglycaemia are shared by patients independent of chronic glycaemic control.

Data availability

The dataset for this study was derived from the MIMIC-IV database. The data supporting the study findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- CABG:

-

Coronary artery bypass grafting

- SIH:

-

stress-induced hyperglycaemia

References

Greco, G. et al. Diabetes and the association of postoperative hyperglycemia with clinical and economic outcomes in cardiac surgery. Diabet. Care 39(3), 408–17 (2016).

Dungan, K. M., Braithwaite, S. S. & Preiser, J. C. Stress hyperglycaemia. Lancet 373(9677), 1798–807 (2009).

Plummer, M. P. et al. Dysglycaemia in the critically ill and the interaction of chronic and acute glycaemia with mortality. Intensiv. Care Med. 40(7), 973–80 (2014).

Lazar, H. L. et al. The society of thoracic surgeons practice guideline series: Blood glucose management during adult cardiac surgery. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 87(2), 663–9 (2009).

ElSayed, N. A. et al. 16 diabetes care in the hospital: Standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 46(Suppl 1), S267–S278 (2023).

Egi, M. et al. The interaction of chronic and acute glycemia with mortality in critically ill patients with diabetes. Crit. Care Med. 39(1), 105–11 (2011).

Lee, T. F. et al. Relative hyperglycemia is an independent determinant of in-hospital mortality in patients with critical illness. Crit. Care Med. 48(2), e115–e122 (2020).

Johnston, L. E. et al. Postoperative hypoglycemia is associated with worse outcomes after cardiac operations. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 103(2), 526–532 (2017).

Bayfield, N. G. R. et al. Conventional glycaemic control may not be beneficial in diabetic patients following cardiac surgery. Heart Lung Circ. 31(12), 1692–1698 (2022).

Chan, P. G. et al. Operative mortality in adult cardiac surgery: Is the currently utilized definition justified?. J. Thorac. Dis. 13(10), 5582–5591 (2021).

Subramaniam, B. et al. Increased glycemic variability in patients with elevated preoperative HbA1C predicts adverse outcomes following coronary artery bypass grafting surgery. Anesth. Analg. 118(2), 277–287 (2014).

Ogawa, S. et al. Continuous postoperative insulin infusion reduces deep sternal wound infection in patients with diabetes undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting using bilateral internal mammary artery grafts: A propensity-matched analysis. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 49(2), 420–6 (2016).

Bardia, A. et al. The association between preoperative hemoglobin A1C and postoperative glycemic variability on 30-day major adverse outcomes following isolated cardiac valvular surgery. Anesth. Analg. 124(1), 16–22 (2017).

Plummer, M. P. et al. Prior exposure to hyperglycaemia attenuates the relationship between glycaemic variability during critical illness and mortality. Crit. Care Resusc. 18(3), 189–97 (2016).

Investigators, N.-S.S. et al. Hypoglycemia and risk of death in critically ill patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 367(12), 1108–18 (2012).

Deane, A. M. & Horowitz, M. Dysglycaemia in the critically ill - significance and management. Diabet. Obes. Metab. 15(9), 792–801 (2013).

Johnson, A. E. et al. MIMIC-III, a freely accessible critical care database. Sci. Data 3, 160035 (2016).

Krinsley, J. S. et al. The interaction of acute and chronic glycemia on the relationship of hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia, and glucose variability to mortality in the critically Ill. Crit. Care Med. 48(12), 1744–1751 (2020).

Palmer, E. et al. The association between supraphysiologic arterial oxygen levels and mortality in critically Ill patients. A multicenter observational cohort study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 200(11), 1373–1380 (2019).

Posit Team, RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R Posit Software Boston, MA (2023).

Gunst, J. et al. Tight blood-glucose control without early parenteral nutrition in the ICU. N. Engl. J. Med. 389(13), 1180–1190 (2023).

Egi, M. et al. Pre-morbid glycemic control modifies the interaction between acute hypoglycemia and mortality. Intensiv. Care Med. 42(4), 562–571 (2016).

Chen, X. et al. Stress hyperglycemia ratio association with all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with coronary heart disease: An analysis of the MIMIC-IV database. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 29110 (2024).

Poole, A. P. et al. The effect of a liberal approach to glucose control in critically Ill patients with type 2 diabetes: A multicenter, parallel-group, open-label randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 206(7), 874–882 (2022).

Kar, P. et al. Liberal glycemic control in critically Ill patients with type 2 diabetes: An exploratory study. Crit. Care Med. 44(9), 1695–703 (2016).

Lazar, H. L. et al. Effects of aggressive versus moderate glycemic control on clinical outcomes in diabetic coronary artery bypass graft patients. Ann. Surg. 254(3), 458–63 (2011).

Desai, S. P. et al. Strict versus liberal target range for perioperative glucose in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting: A prospective randomized controlled trial. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 143(2), 318–25 (2012).

Bohe, J. et al. Individualised versus conventional glucose control in critically-ill patients: The CONTROLING study-a randomized clinical trial. Intensiv. Care Med. 47(11), 1271–1283 (2021).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jenny Shi – conceptualisation, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing – original draft Mark Plummer – conceptualisation, methodology, writing – original draft, review and editing, validation, supervision Luke Perry – writing – review and editing Alex Karamesinis - writing – review and editing Jake V Hinton - writing – review and editing Calvin M Fletcher - writing – review and editing Jahan C Penny-Dimri - writing – review and editing Dhruvesh M. Ramson - writing – review and editing Zhengyang Liu - writing – review and editing Reny Segal - writing – review and editing Julian A. Smith - writing – review and editing Michael Horowitz – conceptualisation, validation, supervision, writing – review and editing Ary Serpa Neto - conceptualisation, software, validation, supervision, writing – review and editing Aniket Nadkarni – conceptualisation, writing – original, review and editing, supervision, project administration

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Institutional review board approval

This research was approved by the institutional review boards of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Cambridge, MA, USA) (2001-P-001699/14) and the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (0403000206)

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, J., Plummer, M., Perry, L. et al. Dysglycaemia and the interaction of chronic and acute glycaemia with mortality post cardiac surgery. Sci Rep 15, 43235 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27328-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27328-8