Abstract

Patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) with unhealthy alcohol use often experience agitation during mechanical ventilation, which can contribute to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The BACLOREA trial investigated whether high-dose baclofen could reduce agitation in these patients, but its long-term effects on PTSD symptoms remained unclear. This study aimed to assess whether baclofen administered during ICU stay to reduce the incidence of agitation could reduce the 5-year PTSD symptoms in adult patients with unhealthy alcohol use and improve long-term quality of life and psychological status. This observational follow-up study was conducted between September 2021 and February 2024 and included patients alive five years after participation in the BACLOREA trial, a randomized, placebo-controlled trial evaluating high-dose baclofen for the prevention of agitation-related events during mechanical ventilation in critically ill patients with unhealthy alcohol use. The primary outcome was the prevalence of PTSD symptoms measured using the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R), with a score ≥ 33 indicating PTSD symptoms. Secondary outcomes included the prevalence of PTSD symptoms using the PTSD Checklist Scale (PCL-S), the quality of life assessed through the SF-36, EQ-5D, and HADS scales. Among the 152 patients who survived five years after ICU admission, 94 (61.8%) completed the follow-up and were included in the BACLO-PTSD study. In this cohort, the 5-year prevalence of PTSD symptoms was 14.9%. For the primary outcome assessed with the IES-R, PTSD symptom prevalence was similar in the baclofen and placebo groups (13.0% vs. 16.7%, p = 0.62). Mean IES-R scores were 10.4 ± 12.5 in the baclofen group and 12.2 ± 13.5 in the placebo group (p = 0.49), while mean PCL-S scores were 25.4 ± 8.6 and 25.5 ± 7.0, respectively (p = 0.94). Quality of life and psychological status, assessed using the SF-36, EQ-5D, and HADS, were also comparable between groups. High-dose baclofen administered during mechanical ventilation did not reduce the 5-year prevalence of PTSD symptoms, nor did it impact quality of life or symptoms of anxiety and depression. Further research is needed to explore alternative strategies for preventing long-term psychological consequences in this population.

Trial registration : NCT05877807, 03 april 2023, retrospectively registered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alcohol is a global public health issue1, and its misuse presents significant challenges in hospital care, particularly in intensive care units (ICUs). At-risk drinking is independently associated with increased mortality in the ICU2 and represents a major risk factor for ICU-acquired infection3. Patients with unhealthy alcohol use admitted to the ICU often experience agitation and delirium linked to alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Managing these symptoms is complicated by the rapid development of tachyphylaxis, limiting the effectiveness of sedative therapies4. These difficulties in sedation increase the risk of complications such as unplanned extubations, accidental catheter removals, or falls.

In the BACLOREA trial5 we evaluated the use of high-dose baclofen, a gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) agonist, to manage alcohol-related agitation in critically ill patients. We found that in patients with unhealthy alcohol consumption requiring mechanical ventilation, high-dose baclofen treatment, compared with placebo, resulted in a 10% reduction in agitation-related events. However, this benefit came at the cost of prolonged sedation, extended mechanical ventilation, and longer ICU stays, raising concerns about the long-term impact of baclofen exposure. Survivors of ICU stay are at risk of developing post-intensive care syndrome (PICS) and cognitive impairment, the intensity of which is often associated with ICU length of stay6. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a component of PICS and a frequent complication among ICU survivors, with prevalence estimates ranging from 4 to 25%, depending on patient population and ICU experience7. PTSD is defined by exposure to a traumatic event involving the threat of death or serious injury, accompanied by intense fear, helplessness, or horror, and followed by symptoms of intrusion, avoidance, and hyperarousal8. Individuals with alcohol dependence are at greater risk of developing PTSD symptoms9,10, and the disorder can persist long after ICU discharge11. Additional risk factors include prolonged sedation, extended mechanical ventilation, and episodes of delirium12,13. Although PTSD symptoms typically develop within a month, some cases exhibit delayed onset, with about 60% of patients recovering within five years14. In addition, anxiety, depression, and PTSD symptoms frequently co-occur among ICU survivors and constitute key components of the post–intensive care syndrome15,16. The BACLO-PTSD study aimed to evaluate whether baclofen administered during ICU stay to prevent agitation could reduce the five-year prevalence of PTSD symptoms in adult patients with unhealthy alcohol use. Secondary objectives were to compare anxiety, depression, and health-related quality of life between groups at five years.

Methods

Study design

The BACLO-PTSD study (Clinical trial: NCT05877807) was designed as a multicenter observational cohort study, which represent the 5-year follow-up of the randomized BACLOREA clinical trial5. It was conducted across 18 ICUs in university and district hospitals throughout France. The BACLOREA trial was a phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial that evaluated high-dose baclofen versus placebo for the prevention of agitation-related events during mechanical ventilation in critically ill patients with unhealthy alcohol use. The present study specifically focuses on long-term psychological outcomes among survivors, including PTSD symptoms, quality of life, and symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee (Comité de Protection des Personnes Sud-Est III, N° 2021–019 B, approval date: September 22, 2021). Patients from the BACLOREA Trial responded to validated questionnaires to assess their PTSD symptoms17 (IES-R, PCL-S) and quality of life18 (EQ5D, SF36, HADS) five years after randomization. Written informed consent obtained from all patients to participate in the trial. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients alive five years after randomization in the BACLOREA trial were eligible for the BACLO-PTSD study. Patients who declined or were unable to complete self-administered questionnaires (e.g., due to cognitive decline) were excluded. The full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria from the original BACLOREA randomized trial is provided in Supplemental eMethods.

Outcomes

Outcomes were assessed within the interval between the 5th and 6th year after randomization in the BACLOREA study, which was defined as the 5-year follow-up.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome of the BACLO-PTSD study was to evaluate the prevalence PTSD symptoms using the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R)19. This scale assesses three key dimensions of PTSD: intrusive memories, avoidance, and hyperarousal. Experts in long-term outcomes research have recommended the IES-R as a core outcome measure for mental health following critical illness20, and it has been extensively validated in critically ill populations, demonstrating strong performance and suitability for ICU survivorship research17,21. The questionnaire comprises 22 items, each rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). The IES-R was used as a validated screening instrument for PTSD symptoms, with a score ≥ 33 indicating a clinically significant likelihood of PTSD symptoms. This threshold has high sensitivity and specificity22 and has been widely adopted in the literature23,24,25.

Secondary outcomes

-

Evaluation of the PTSD by the PTSD Checklist Scale (PCL-S)26: The PCL-S was included as a predefined secondary measure to assess concordance with the IES-R and to ensure comparability with previous studies in ICU survivors27. This questionnaire consists of 17 items addressing the core symptoms of PTSD. Scores range up to 85 points, with higher scores indicating more severe PTSD symptoms.

-

Evaluation of the quality of life using the questionnaire European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)28: This tool evaluates five dimensions: Mobility, Autonomy, Daily Activities, Pain/Discomfort, and Anxiety/Depression. Each dimension is rated from 1 (best outcome) to 3 (worst outcome).

-

Health assessment using the Short Form (SF-36)29: This questionnaire covers eight dimensions: physical activity, social relationships, physical pain, perceived general health, vitality, limitations due to mental or physical health, and mental health. Scores range from 0 (poor health) to 100 (optimal health).

-

Assessment of anxiety and depression with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)30: The HADS includes 14 items, each rated from 0 to 3. The maximum score for both anxiety and depression subscales is 21, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. We also dichotomized the anxiety and depression subscales using the validated cutoff of ≥ 8 to define clinically relevant symptoms of anxiety or depression31,32.

-

Patient habits assessment: Tobacco, alcohol, and drug consumption were evaluated five years after ICU admission.

Methodology for collecting questionnaires

Before sending information letters to participants, medical records and the French death registry were reviewed to confirm eligibility. Only living patients were contacted and received an information letter explaining the BACLOPTSD study. Participants had a two-week period to object to their inclusion in the study and notify the participating center if they declined to participate in telephone interviews.

After the objection period, a research staff member from Nantes University Hospital conducted telephone interviews with participants. These interviews collected patients’ self-assessments, with the research staff blinded to the randomization group. All data were recorded on anonymized Case Report Forms (CRFs) and analyzed in a blinded manner to ensure unbiased results.

Participants whose responses indicated symptoms of PTSD were referred to their personal general practitioner for appropriate follow-up care.

Statistical analysis

The baseline characteristics of the patients were described and compared between the two groups using Student’s t-test for continuous variables and Chi-2 and Fisher’s exact tests categorical variables, as appropriate. The primary endpoint (IES-R ≥ 33) was compared between the two groups using the Chi-2 test, and a quantitative score was also presented and compared using the student’s t-test. Secondary endpoints were compared between the groups using Student’s tests (PCL-S score, HADS anxiety and depression score, and SF36 scores), Chi-2 tests (EQ-5D items). In addition, we reported effect-size estimates with 95% confidence intervals. For binary outcomes (e.g., dichotomized IES-R), we present both the absolute percentage difference and unadjusted odds ratio (OR). For continuous outcomes (e.g., mean IES-R and PCL-S scores), we report the mean difference (MD) between groups. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS® software version 9.4.

Results

Study population

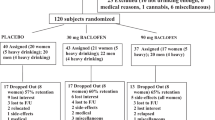

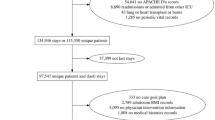

At the end of the BACLOREA trial, 231 patients were alive. Five years after randomization, 152 patients remained alive and were eligible for inclusion in the BACLO-PTSD study (see Fig. 1 for causes of death). Among them, 94 patients were included in the study (61.8%). A total of 39 patients (25.7%) declined the five-year follow-up, nine (5.9%) had severe cognitive impairment and could not respond to the questionnaires, nine (5.9%) were lost to follow-up, and one was deprived of their rights (i.e., in jail). The characteristics of the 94 patients included are presented in Table 1. These patients were predominantly male (80.2%) and were mostly admitted to the ICU for medical reasons (76.3%). The main reasons for hospitalization at the time of inclusion in the BACLOREA study were acute respiratory failure (32.9%), sepsis (15.8%) and trauma (13.2%). We compared baseline characteristics of the 94 included patients with those who died within five years (n = 75) and those who were alive but not included (n = 58) (Supplementary Table S1). Patients who died within five years were significantly older, had higher SAPS II scores, and more frequent comorbidities such as cirrhosis or chronic respiratory disease. Non-included survivors were more often female, with comparable baseline severity scores.

Primary outcome

Across the entire study population (n = 94), the five-year prevalence of PTSD symptoms was 14.9%. PTSD symptoms were reported in six patients (13%) in the baclofen group compared to eight patients (16.7%) in the placebo group (p = 0.62, Table 2). The mean IES-R score was 10.41 (± 12.53) in the baclofen group and 12.25 (± 13.50) in the placebo group (p = 0.49, Table 2and Supplemental Fig. 1).

Secondary outcomes

PTSD symptoms were also assessed using the PCL-S scale, confirming the absence of significant difference between the two groups. The mean PCL-S score was 25.4 (SD ± 8.6) in the baclofen group and 25.5 (SD ± 7.0) in the placebo group (p = 0.94, Table 2 and Supplemental Fig. 2).

No significant differences were observed between the two groups in any SF-36 dimensions (Table 2). The lowest scores were reported for physical limitations, with a mean score of 59.7 (SD ± 46.9) in the baclofen group and 58.8 (SD ± 48.5) in the placebo group (p = 0.92). A detailed comparison of the SF-36 dimensions between the two groups is provided in Supplemental Fig. 3. Similarly, no differences were found across the five dimensions of the EQ-5D scale. The mean (± SD) EQ-5D utility index was 0.86 ± 0.20 in the baclofen group and 0.85 ± 0.16 in the placebo group (p = 0.88). Sixty-seven patients (71.2%) reported no mobility limitations, and seventy-eight (83%) reported no anxiety or depressive symptoms (Table 2). Moderate pain was reported by 30–40% of patients.

The HADS scale, assessing anxiety and depression, showed no significant differences between the baclofen and placebo groups for anxiety (2.8 ± 2.9 vs. 2.7 ± 2.5, p = 0.86) or depression (1.9 ± 2.7 vs. 1.6 ± 1.9, p = 0.55) (Table 2 and Supplemental Fig. 4). Additional patient characteristics at five years post-randomization are presented in Table 3. No significant differences were found between groups in terms of alcohol abuse, drug use, or professional activity.

Discussion

Our study is the first to report the role of baclofen on long-term outcomes of unhealthy alcohol consumers five years after ICU hospitalization. Administration of high-dose baclofen during mechanical ventilation in the ICU did not significantly reduce the occurrence of PTSD symptoms. Additionally, there were no differences between the groups in terms of long-term quality of life.

Stressors, such as mechanical ventilation, delirium, or drug side effects, contribute to the onset of PTSD symptoms, which can persist for many years. For instance, a study examining cognitive and psychosocial outcomes found that delirium during ICU stay was independently associated with cognitive function at ICU discharge and PTSD symptoms at 12 months33. Adequate prevention and management of agitation could be one way to reduce the incidence of PTSD symptoms after ICU discharge34,35. This was the hypothesis of the present study. The BACLOREA study5 demonstrated that the use of a GABA agonist (i.e., baclofen, a GABA-B agonist molecule) during mechanical ventilation reduced agitation in the ICU among unhealthy alcohol users. Therefore, it was important to investigate the long-term effects of baclofen. The BACLO-PTSD study suggests that the use of baclofen does not decrease the prevalence of PTSD symptoms despite the increase in the duration of invasive mechanical ventilation and length of stay in the ICU.

The BACLO-PTSD study is a multimodal assessment of the outcome of alcohol-dependent patients five years after ICU admission. It provides long-term data on survival, quality of life, and psychological health. The study shows that more than half of these patients died within five years, confirming the high mortality rate and the extreme vulnerability of patients with unhealthy alcohol use at ICU admission36, comparable to the five-year mortality observed in patients admitted for sepsis37. Among survivors, physical limitations, pain, and psychological symptoms were frequent, while overall quality of life remained impaired. By combining mortality, functional status, and mental health, this study gives a comprehensive picture of the long-term burden faced by this high-risk population after critical illness. In our study, the incidence of PTSD symptoms was 14.9% across all patients. This result is consistent with existing data, which reported an approximate PTSD symptoms incidence of 19% more than one year after ICU hospitalization38. However, there are very few data on the long-term incidence of PTSD symptoms (i.e., five years after ICU admission)39. The strength of our study lies, therefore, in the very long-term follow-up of fragile patients after hospitalization in intensive care.

Although the number of patients per group was limited, the consistent findings across both IES-R and PCL-S assessments support the reliability of our results. The study was underpowered to highlight a difference between groups, but there was a trend indicating a lower incidence of PTSD symptoms (IES-R score equal of higher than 33) in patients treated with baclofen compared with placebo (13% vs. 16.7%, respectively). The absence of differences between groups in quality-of-life scales (SF-36, EQ-5D, and HADS) at five years suggests that no major long-term impact of baclofen exposure was detectable in this cohort. However, this finding should be interpreted with caution, as a single assessment at this timepoint cannot definitively rule out the possibility of long-term side effects.

Our study has limitations. First, PTSD symptoms were assessed only once, at five years after ICU admission. This design does not allow us to capture the temporal trajectories of PTSD symptoms, including cases that may have resolved within the first year or new cases that may have developed later. Prior studies have shown that PTSD symptoms are frequent in the early months after ICU discharge, with pooled estimates of 20–25% within the first three months, and around 15–20% at 12 months38. In patients with alcohol misuse, psychological difficulties have also been reported as early as three months after ICU discharge40. Moreover, symptoms reported at five years may also be influenced by unrelated traumatic events during the follow-up period. For these reasons, the absence of repeated assessments limits our ability to distinguish the specific long-term impact of baclofen exposure during ICU from other factors. Future studies should include serial follow-up assessments (e.g., at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years) to better characterize trajectories of psychological outcomes after ICU. Second, the primary outcome was missing for 58 (38%) of the 152 patients who were alive at five years. Patients with PTSD symptoms may be less likely to be willing to participate in follow-up and/or respond to extensive questionnaires37, which could have led to an underestimation of the incidence of PTSD symptoms. Third, a link between long-term PTSD symptoms and cognitive dysfunction has recently been established. Considering that patients with unhealthy alcohol use could experience a more rapid cognitive decline than the general population41, a parallel evaluation of cognitive function could provide interesting insights in this population42. Fourth, while long-term data collection is indispensable for critically ill patients, it presents significant limitations, particularly in the context of psychological outcomes. After a five-year period, discerning whether the observed effects stem from the initial trauma or subsequent life events becomes increasingly complex. Future studies using mixed or interview-based qualitative approaches could help explore the underlying mechanisms and patient experiences contributing to long-term psychological disorders after ICU discharge. Fifth, self-reported PTSD symptoms may be subject to recall bias. In particular, based on their current psychological state, patients may underreport or overreport their symptoms of PTSD43. Sixth, the probability of highlighting a difference in PTSD symptoms in the long term after a relatively short-term treatment period with baclofen in the ICU (up to 15 days) was relatively low a priori. However, prevention of PTSD symptoms relies on the prevention of each stressor event in the ICU, including delirium and agitation. The high rate of PTSD symptoms five years after ICU hospitalization underscores the importance of continuing research on the prevention of associated factors during hospitalization. Finally, as expected, five-year survivors were younger and less severely ill than those who died during follow-up. However, among survivors at five years, the similar baseline severity and comorbidity profiles between included and non-included patients suggest that our findings remain reasonably representative of long-term ICU survivors with unhealthy alcohol use.

Conclusion

The use of high-dose baclofen during mechanical ventilation to prevent ICU agitation did not reduce PTSD symptom prevalence at five years, nor did it affect quality of life or symptoms of anxiety and depression. Further research is needed to explore alternative strategies to prevent long-term psychological consequences in this vulnerable population.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- EQ-5D:

-

European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions

- GABA:

-

Gamma-aminobutyrique acid

- HADS:

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IES-R:

-

Impact of Event Scale Revised

- NIAAA:

-

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

- PTSD:

-

Post traumatic stress disorder

- PCL-S:

-

PTSD Checklist Scale

- SF-36:

-

Short Form 36

References

Bryazka, D. et al. Population-level risks of alcohol consumption by amount, geography, age, sex, and year: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2020. Lancet 400(10347), 185–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00847-9 (2022).

Gacouin, A. et al. At-risk drinking is independently associated with ICU and one-year mortality in critically ill nontrauma patients*. Crit. Care Med. 42(4), 860–867. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000000041 (2014).

Gacouin, A. et al. At-risk drinkers are at higher risk to acquire a bacterial infection during an intensive care unit stay than abstinent or moderate drinkers. Crit. Care Med. 36(6), 1735–1741. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e318174dd75 (2008).

Stewart, D., Kinsella, J., McPeake, J., Quasim, T. & Puxty, A. The influence of alcohol abuse on agitation, delirium and sedative requirements of patients admitted to a general intensive care unit. J. Intensive Care. Soc. 20(3), 208–215. https://doi.org/10.1177/1751143718787748 (2019).

Vourc’h, M. et al. Effect of high-dose baclofen on agitation-related events among patients with unhealthy alcohol use receiving mechanical ventilation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 325(8), 732–741. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.0658 (2021).

Pandharipande, P. P. et al. Long-Term Cognitive Impairment after Critical Illness. N. Engl. J. Med. 369(14), 1306–1316. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1301372 (2013).

Jones, C. et al. Precipitants of post-traumatic stress disorder following intensive care: a hypothesis generating study of diversity in care. Intensive Care Med. 33(6), 978–985. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-007-0600-8 (2007).

Friedman, M. J., Resick, P. A., Bryant, R. A. & Brewin, C. R. Considering PTSD for DSM-5. Depress Anxiety 28(9), 750–769. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20767 (2011).

Lee, D. J., Liverant, G. I., Lowmaster, S. E., Gradus, J. L. & Sloan, D. M. PTSD and reasons for living: Associations with depressive symptoms and alcohol use. Psychiatry Res. 219(3), 550–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.06.016 (2014).

Balachandran, T., Cohen, G., Le Foll, B., Rehm, J. & Hassan, A. N. The effect of pre-existing alcohol use disorder on the risk of developing posttraumatic stress disorder: results from a longitudinal national representative sample. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 46(2), 232–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/00952990.2019.1690495 (2020).

Griffiths, J., Fortune, G., Barber, V. & Young, J. D. The prevalence of post traumatic stress disorder in survivors of ICU treatment: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 33(9), 1506–1518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-007-0730-z (2007).

Taylor, A. K., Fothergill, C., Chew-Graham, C. A., Patel, S. & Krige, A. Identification of post-traumatic stress disorder following ICU. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 69(680), 154–155. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp19X701765 (2019).

Wade, D., Hardy, R., Howell, D. & Mythen, M. Identifying clinical and acute psychological risk factors for PTSD after critical care: a systematic review. Minerva Anestesiol. 79(8), 944–963 (2013).

Burki, T. K. Post-traumatic stress in the intensive care unit. Lancet Respir. Med. 7(10), 843–844. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30203-6 (2019).

Needham, D. M. et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: Report from a stakeholdersʼ conference*. Crit Care Med. 40(2), 502–509. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232da75 (2012).

Bienvenu, O. J. et al. Cooccurrence of and Remission From General Anxiety, Depression, and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms After Acute Lung Injury: A 2-Year Longitudinal Study. Crit Care Med. 43(3), 642–653. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000000752 (2015).

Hosey, M. M. et al. The IES-R remains a core outcome measure for PTSD in critical illness survivorship research. Crit. Care. 23(1), 362. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-019-2630-3 (2019).

Hodgson, C. L. et al. The impact of disability in survivors of critical illness. Intensive Care Med. 43(7), 992–1001. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-017-4830-0 (2017).

Weiss, D.S., Marmar, C.R. The impact of event scale—revised. Assess Psychol Trauma PTSD. Published online. 399–411. (1997).

Dinglas, V. D., Faraone, L. N. & Needham, D. M. Understanding patient-important outcomes after critical illness: a synthesis of recent qualitative, empirical, and consensus-related studies. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care. 24(5), 401–409. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCC.0000000000000533 (2018).

Bienvenu, O. J., Williams, J. B., Yang, A., Hopkins, R. O. & Needham, D. M. Posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors of acute lung injury: evaluating the Impact of Event Scale-Revised. Chest 144(1), 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.12-0908 (2013).

Creamer, M., Bell, R. & Failla, S. Psychometric properties of the Impact of Event Scale—Revised. Behav. Res. Ther. 41(12), 1489–1496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.010 (2003).

Saida, I. B., Zghidi, M., Fathallah, S. & Boussarsar, M. Post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and depression in North African intensive care unit survivors: a prospective observational study. Acute Crit. Care. 40(3), 402–412. https://doi.org/10.4266/acc.000150 (2025).

Tang, S. T. et al. Course and predictors of posttraumatic stress-related symptoms among family members of deceased ICU patients during the first year of bereavement. Crit. Care Lond. Engl. 25(1), 282. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-021-03719-x (2021).

Renzi, E. et al. The other side of COVID-19: A cross-sectional study on mental health in a sample of Italian nurses during the second wave. Front. Psychiatry. 14, 1083693. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1083693 (2023).

Ventureyra, V. A. G., Yao, S. N., Cottraux, J., Note, I. & De Mey-Guillard, C. The validation of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist Scale in posttraumatic stress disorder and nonclinical subjects. Psychother Psychosom. 71(1), 47–53. https://doi.org/10.1159/000049343 (2002).

Elliott, R., McKinley, S., Fien, M. & Elliott, D. Posttraumatic stress symptoms in intensive care patients: An exploration of associated factors. Rehabil. Psychol. 61(2), 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1037/rep0000074 (2016).

Group TE. EuroQol - a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 16(3), 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9 (1990).

Ware, J. E. & Sherbourne, C. D. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med. Care 30(6), 473–483 (1992).

Zigmond, A. S. & Snaith, R. P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 67(6), 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x (1983).

Rabiee, A. et al. Depressive Symptoms After Critical Illness: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit. Care Med. 44(9), 1744–1753. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000001811 (2016).

Bjelland, I., Dahl, A. A., Haug, T. T. & Neckelmann, D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J. Psychosom. Res. 52(2), 69–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3 (2002).

Bulic, D. et al. Cognitive and psychosocial outcomes of mechanically ventilated intensive care patients with and without delirium. Ann. Intensive Care 10(1), 104. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-020-00723-2 (2020).

Roberts, M. B. et al. Early Interventions for the Prevention of Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms in Survivors of Critical Illness: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Crit. Care Med. 46(8), 1328–1333. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000003222 (2018).

Bienvenu, O. J. & Gerstenblith, T. A. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Phenomena After Critical Illness. Crit. Care Clin. 33(3), 649–658. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccc.2017.03.006 (2017).

McPeake, J. M. et al. Do alcohol use disorders impact on long term outcomes from intensive care?. Crit. Care 19(1), 185. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-015-0909-6 (2015).

Cuthbertson, B. H. et al. Mortality and quality of life in the five years after severe sepsis. Crit. Care 17(2), R70. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc12616 (2013).

Righy, C. et al. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in adult critical care survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Lond Engl. 23(1), 213. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-019-2489-3 (2019).

Jackson, J. C. et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder and post-traumatic stress symptoms following critical illness in medical intensive care unit patients: assessing the magnitude of the problem. Crit. Care Lond. Engl. 11(1), R27. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc5707 (2007).

Clark, B. J. et al. The Experience of Patients with Alcohol Misuse after Surviving a Critical Illness. A Qualitative Study. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 14(7), 1154–1161. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201611-854OC (2017).

Yen, F. S., Wang, S. I., Lin, S. Y., Chao, Y. H. & Wei, J. C. C. The impact of heavy alcohol consumption on cognitive impairment in young old and middle old persons. J. Transl. Med. 20(1), 155. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-022-03353-3 (2022).

Brück, E., Schandl, A., Bottai, M. & Sackey, P. The impact of sepsis, delirium, and psychological distress on self-rated cognitive function in ICU survivors-a prospective cohort study. J. Intensive Care 6, 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-017-0272-6 (2018).

Nakanishi, N. et al. Post-intensive care syndrome follow-up system after hospital discharge: a narrative review. J. Intensive Care 12(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-023-00716-w (2024).

Funding

Institutional fundings.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

MB, KA and MV designed the study. MB, MV and YRV contributed to screening and enrolling eligible patients. MB, KA and MV performed data analysis. CV performed statistical analysis MB & MV wrote the main version of the manuscript. MB, KA & MV supervised statistical analysis and data interpretation. All authors contributed to the analysis or interpretation of the data, reviewed and critically revised the manuscript, approved the final draft, and are accountable for the accuracy and integrity of this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee (Comité de Protection des Personnes Sud-Est III, N° 2021–019 B, approval date: September 22, 2021). All patients received oral and written information prior to enrollment and provided consent to participate in the BACLO-PTSD study. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bouras, M., Asehnoune, K., Robert-Valli, Y. et al. Effect of high-dose baclofen on post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms five years after hospitalization among critically ill patients with unhealthy alcohol use. Sci Rep 16, 1088 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27423-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27423-w