Abstract

This research focuses on the problem of frost heave damage in trapezoidal concrete-lined canals in cold regions. Using the main canal of the Jingdian Irrigation District, China, as the engineering prototype, the control effect of the thickness of the sand-gravel replacement layer on the temperature field, moisture field, and frost heave deformation of the canal foundation was systematically analyzed through a combination of prototype monitoring experiments and numerical simulation. The optimal sand-gravel replacement thickness suitable for trapezoidal concrete-lined canals in cold regions is proposed. The results indicate that the sand-gravel cushion layer significantly inhibits water migration and frost heave development during the freezing process of the foundation soil by blocking the capillary water migration path and regulating the heat conduction characteristics. Increasing the replacement thickness can effectively delay the advancement rate of the freezing front, significantly reducing the frost heave deformation, normal frost heave force, and tangential freezing force of the canal, resulting in a more uniform distribution. With a gradient replacement scheme ranging from 30 cm at the top to 70 cm at the bottom of the canal, the peak normal frost heave force and tangential freezing force were reduced by 40.3% and 38.7%, respectively, and the maximum normal displacement decreased from 4.26 cm of the original foundation soil to 0.95 cm, meeting the specification requirements of 0.5 to 1.0 cm, thereby achieving the frost-heave mitigation goal in a cost-effective manner. The results provide a theoretical basis for the design and application of sand-gravel replacement canal foundations in cold regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Amid the implementation of China’s 14th Five-Year Plan for Western Region Development, numerous largescale water conservancy and transportation infrastructure programs have been rolled out in the arid and freezing western areas1,2. Due to the severe water shortage in these regions, the safety and stability of water conveyance structures are critical to ensuring regional water supply and promoting economic growth3. In cold and arid areas with extremely scarce water resources, agricultural irrigation faces great difficulties4. Canal irrigation has therefore become a core pillar for supporting the sustainable development of agriculture5,6,7. However, affected by seasonal frozen soil, the foundation of canals undergoes significant deformation during freeze–thaw cycles. Driven by frost heave and seepage, this deformation leads to structural cracks, bulges, and bank collapses in canals. These risks caused by freezing not only damage the structural stability and operational reliability of the projects over the long term but also form a key bottleneck. This bottleneck limits the efficiency of water allocation and slows down the socio-economic development of the regions. Canals act as essential infrastructure for water distribution and agricultural irrigation8, which is demonstrated by large-scale projects like China’s South-to-North Water Transfer Project and California’s State Water Project9,10. Damage to canals in the seasonal freeze regions is influenced by the environmental factors (precipitation, solar radiation7, evaporation, airflow11, etc.), the groundwater table and the form of canals (section form and lining structure1, etc.), and the properties of soil (permeability, water content, gradation, pore space, etc.)12. In winter, uneven frost heave occurs in the foundation soil due to these multiple factors13,14,15, which often damages the canal structure and its anti-seepage function16, posing a serious threat to the safe operation and water delivery efficiency of the canal. To address frost heave damage and reduce secondary water loss, extensive research has been conducted on frost heave prevention technologies for water conveyance canals in cold regions. These efforts not only have practical significance for the sustainable operation of agricultural irrigation systems but also promote the development of theories related to hydraulic infrastructure in cold regions.

In recent years, the academic community has achieved notable advancements in research on the mechanism of canal frost heave and technologies for its prevention and control. Wang et al.13,17,18 developed and analyzed canal frost heave models, clarifying the response characteristics and failure mechanisms of canals under frost heave effects. Wang et al.19, Li et al.20, and Liu et al.21 conducted in-depth analyses of the dynamic variations and distribution patterns of heat-displacement interactions between the two fields during the frost heave process. Li et al.22 revealed that the anti-frost heave mechanism of geotextile bags not only involves soil reinforcement but also effectively suppresses the upward movement of capillary water and film water. Through the study of the thermal-hydro-mechanical coupling model, Teng et al.23 found that the freezing process of foundation soil is unidirectional process from the surface to the bottom, while the melting process is bidirectional from the surface and the bottom to the center. Jiang and Tian24 discovered that the overall uplift of rigid flexible composite lined canals during the freezing period is caused by the vertical deformation of the canal bottom lining and the radial deformation of the slope slabs. The field test results of Guo et al.25,26 in the Hetao Irrigation District of Inner Mongolia showed that polystyrene boards could significantly delay the freezing process of foundation soil. Wang et al.27 pointed out that the increase in temperature and the melting of the contact segregated ice layer led to the loss of surface soil strength, which in turn causes canal slope instability and lining collapse. Guo et al.16 found that raising the groundwater level can reduce water migration within the soil, thereby minimizing the occurrence of frost heave. Li et al.28 combined experiments and numerical simulations to deeply analyze the mechanism of thermal-hydro-mechanical interaction of frozen soil. Xu et al.29 proposed a hydrothermal coupling transfer model and determined the optimal thickness of the insulation board. Following prototype testing and numerical simulation analysis over a freeze–thaw cycle, Li et al.30 found that the total water content at the freeze–thaw front driven by temperature gradients is high, with some frozen fronts containing unfrozen water and ice, resulting in significant tensile stresses and severe frost heave deformation. Despite substantial progress in research on the failure mechanism of canal frost heave and corresponding prevention measures both domestically and internationally, there remains a paucity of studies on hydrothermal variations, frost heave characteristics, and anti-frost heave effectiveness of canal foundation soil under different thicknesses of gradient sand-gravel replacement layers.

Based on this, this research conducted experiments on replacing the canal foundation soil with a gradient sand-gravel cushion in the main canal of the Jingdian Irrigation District, obtaining temperature, moisture content, and frost heave deformation data of the base soil during the freeze–thaw cycle. Combined with numerical simulation, frost heave deformation of the canal and the stress distribution of the lining plate under different replacement thicknesses was analyzed. The optimal replacement thickness of the sand-gravel cushion suitable for the trapezoidal concrete-lined canal in cold regions is determined, providing a theoretical basis for the design and application of sand-gravel replacement for the lined canal in cold regions.

Research method

Project profile

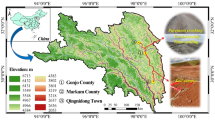

The test site is situated in the Jingdian Irrigation District of Gansu Province, China (37.361°N, 104.031°E). As displayed in Fig. 1, this area falls within a typical seasonally frozen soil zone and is characterized by rigorous regional climatic conditions. The mean annual temperature stands at 10 °C, with an extreme minimum temperature of -27.3 °C and a maximum freezing depth of roughly 99 cm. The actual area under irrigation covers around 93,333 hectares, while the total length of water conveyance canals reaches approximately 2422 km. Serving as a core water conveyance artery for the Jingtai and Minqin regions, this canal system plays an indispensable role in securing domestic water supplies for local residents and fulfilling agricultural irrigation demands.

The foundation soil of the canals in this area exhibits high frost susceptibility. Under the action of seasonal freeze–thaw cycles, the canal structure regularly undergoes notable frost heave deformation and thaw settlement. The resulting frost damage manifestations, including lining collapse, local cavitation, and water leakage losses, are illustrated in Fig. 2. These issues not only undermine the efficiency of water conveyance but also pose a severe risk to the operational safety of the project. The gradual deterioration of the canal structure induced by repeated freeze–thaw cycles has become a critical technical bottleneck that limits the sustainable operation of water conveyance projects in cold regions.

The map in Fig. 1 is based on the standard map, which is downloaded from the standard map service website of the Ministry of Natural Resources, and the review number is the GS (2016) No. 1600. No changes to the base image.

Research area map. (a) test site; (b) east–west oriented canal; (c) north–south oriented Canal. Maps were drawn by authors, using ArcGIS 10.8 (Environmental Systems Research Institute, USA. https://www.esri.com).

Prototype monitoring test scheme

In this field experiment, representative trapezoidal canals oriented north–south and east–west were chosen as the research subjects. Each of the two test canal segments had a length of 10 m. The thickness of the sand-gravel replacement layer was designed based on the variations in frost heave between the canal bottom and the slopes. After excavating the foundation to the designed elevation, compaction work was carried out on both the canal bottom and the slopes. Following this, well-graded sand-gravel with a fine content of less than 3% was laid and compacted, achieving a relative compaction density of ≥ 0.65. For the lining structure of the canal bottom and slopes, a 10 cm thick C20 precast concrete slab, a 3 cm thick M10 cement mortar layer, and a flexible composite geomembrane were adopted. Detailed schemes for the sand-gravel replacement are presented in Table 1.

The Schematic diagram of canal monitoring instrument layout and monitoring points is shown in Fig. 3, while the on-site arrangement of monitoring instruments and canal operation status in trapezoidal concrete-lined canals are shown in Fig. 4. The layout of monitoring instruments and monitoring points is illustrated in Fig. 3, while the on-site arrangement of monitoring instruments in trapezoidal concrete-lined canals and canal operation are presented in Fig. 4. Five measurement points (A to E) were established on each canal cross-section, with one DG0100 series frost heave meter installed at each point. Specifically, the frost heave meters were placed in the middle of the canal bottom and at every one-third position along the canal slopes, resulting in a total of 20 units. These meters were embedded at a depth of 2 m and labeled D1 to D5 for each cross-section.

For each test section, 15 DY0100 series soil temperature and humidity meters were deployed. These meters were embedded at distinct depths along the axis of the frost heave meters, including the top of the cushion layer, the bottom of the cushion layer, and 1.5 m below the lining surface, and amounting to 60 units in total. The temperature and humidity meters were numbered T1 to T15. Data collection and uploading for monitoring commenced on November 1, 2020. The cloud-based data acquisition system collected data every two hours, and the monitoring period lasted for two years, covering two complete freeze–thaw cycles.

Numerical calculation method of sand-gravel replacement in trapezoidal canal

Due to the formation of the frozen soil layer of the canal, the coupling process between the three phases is very complicated, making accurate simulation of the entire frost heave process challenging. To facilitate practical application, the main characteristics of the freezing process were reasonably simplified and assumed when constructing the mechanical model31,32. The basic assumptions are as follows: (1) The frozen soil is a uniform, continuous, isotropic medium; (2) The phase transition temperature is 0 °C; (3) The latent heat of phase change is neglected to simplify the heat transfer calculation; (4)The influence of pore water pressure and salt content in the soil on the canal is neglected; (5) The model is a closed system; the canal foundation soil is saturated, water migration is not considered, and convection and radiation are ignored.

Based on the thermal-mechanical coupling frost heave theory for frozen soil, a frost heave model for lined canals with different sand-gravel replacement thicknesses was established, and numerical simulation was performed using ANSYS software (Version19.2).

Soil heat conduction equation and frozen soil constitutive equation

According to the basic assumptions, water migration was not considered in the simulation of the soil freezing process and the freezing process of the foundation soil during the entire freezing period was considered as steady-state heat transfer. Heat transfer was analyzed assuming a two-dimensional plane strain condition for the canal. According to the research of Nixon J.F., Taylor G.S. and Luthin J.N., convection and radiation can be ignored in the freezing and thawing process relative to heat conduction19. Then the plane two-dimensional heat conduction equation is:

where λx, λy represent the thermal conductivities in the x and y directions of the frozen soil, respectively. T represents temperature. A represents the frost heave area of the foundation soil. The temperature boundary condition is T( L, t) = TL, where L is the position of the freezing boundary and t represents time.

The constitutive equation of frozen soil is:

where E represents the elastic modulus of the material. ΔT represents the temperature difference. µ represents the Poisson ‘s ratio. α represents the coefficient of linear thermal expansion. εx, εy represent the normal strains. γxy represents the shear strain. σx, σy represent the normal stresses. τxy represents the shear stress.

Build finite element model

Based on the canal dimensions, eight numerical models simulating frost heave in concrete-lined canals with different replacement thicknesses were established. The constant temperature layer boundary was set at 3 m horizontally from the top edges of the canal and 12 m vertically downward from the canal bottom. The monitoring points from the prototype canal were used as calculation and analysis points in the numerical simulation. Table 2 lists the sand-gravel replacement simulation schemes. The specific canal section geometry and the finite element mesh are shown in Fig. 5.

Material parameter selection and boundary conditions

For the thermo-mechanical coupled calculation, material parameters were selected based on Reference33. The frost heave coefficient of the frozen soil was treated as a negative thermal expansion coefficient19, the Poisson ‘s ratio was 0.33, and the thermal conductivity was 2.04 W/(m·K), with the elastic modulus of frozen soil provided in Table 3. The elastic modulus of concrete was 2.6 × 104 MPa, the Poisson ‘s ratio was 0.167, the thermal conductivity was 1.54 W/(m·K), and the linear expansion coefficient was 1.1 × 10− 5. The elastic modulus of the unfrozen soil was 4.5 × 104 MPa, the Poisson ‘s ratio was 0.2, and the thermal conductivity was 0.78 W/(m·K). The thermal physical parameters and mechanical parameters of the sand-gravel were shown in Table 4. and 5.

Based on the principle of constant temperature layer, the lower temperature boundary of the model was set at 10 °C, and the upper temperature boundary was set based on the lowest measured surface temperatures of the canal. The applied temperatures were: shady slope: -6.3 °C, canal bottom: -5.56 °C, and sunny slope: -4.6 °C. The left and right boundaries were considered adiabatic. Horizontal displacement constraints were applied to the left and right boundaries of the model. The bottom boundary had fixed constraints (zero displacement), and the top boundary was free (no constraints).

Results

Variation characteristics of soil water and heat in canal foundation

During the soil freezing process, the intensity of frost heave is influenced by the initial moisture content of the soil layer and the extent of water vapor migration. Figures 6 and 7 illustrate variations in moisture content and temperature at the bottom of the cushion layer at each measuring point along east–west Section I and north–south Section III during two freeze–thaw cycles. As shown in Fig. 6, the moisture content at each measuring point in Section III remained between 35% and 45%, with only minor fluctuations and no distinct peaks or troughs. In contrast, the moisture content in Section I exhibited more pronounced variations, characterized by a gradual decrease in the early freezing stage, followed by a minimum value, and a subsequent increase during thawing. These patterns indicate clear directional differences in the moisture content of the foundation soil, with varying trends between the two canal alignments.

As seen in Fig. 7, the temperature trends in both canal sections were generally consistent; however, fluctuations were more evident in the upper slope areas compared with other regions. The soil temperature at the bottom of the cushion layer in the north–south canal remained higher than that in the east–west canal, likely due to asymmetric solar radiation exposure. A comparative analysis of soil temperature and moisture content during the freeze–thaw cycles revealed notable differences between the two slopes of the east–west canal. Prior to freezing, the shaded slope contained more moisture than the slope facing the sun, and moisture content increased from the upper slope toward the canal bottom. Thermally, the lower slope was warmer than the upper slope, the slope facing the sun was warmer than the shaded slope, and the canal bottom exhibited intermediate temperatures. As freezing progressed and temperatures declined, the moisture content at each measuring point in the cushion layer decreased, and the differences between points diminished. The moisture distribution during the thawing stage differed from that in the initial freezing stage, which can be attributed to moisture redistribution driven by temperature gradients and capillary action induced by ice crystal formation.

Figure 8 illustrates the distribution characteristics of canal temperature field at the time of maximum freezing depth. As shown in Fig. 8, the spatial distribution of the canal temperature field with sand-gravel replacement resembles that without replacement. Specifically, in the vicinity of the canal bottom and slope surfaces, soil temperature fluctuations are more pronounced, and the temperature gradient is markedly greater than in deeper soil layers. As soil depth increases, the temperature gradient progressively diminishes and the temperature field becomes increasingly stable, indicating that deeper soil layers are less susceptible to ambient thermal fluctuations.

As sand-gravel replacement thickness increased, the 0 °C isotherm shifted downward significantly, leading to greater frozen depths. However, the relationship between frozen depth increase and replacement thickness is nonlinear and exhibits a diminishing incremental effect, with each additional unit of thickness yielding progressively less frozen depth increase. This diminishing return is primarily attributed to the porous structure of the sand-gravel layer, which restricts soil moisture migration and alters the moisture field distribution, thereby modifying the latent heat transfer process during phase change. The well-graded sand-gravel layer, with its coarse particles and large pore spaces, primarily functions by blocking the capillary water migration path and regulating the heat conduction characteristics. This porous structure effectively breaks the capillary continuity, thereby inhibiting the water supply to the freezing front and limiting the formation of ice lenses. Simultaneously, it acts as a structural cushion that distributes frost heave stresses more uniformly, thereby reducing stress concentrations in the lining and restraining soil deformation. Freezing depth distribution exhibits significant spatial heterogeneity: depths along the canal slopes consistently exceed those at the canal bottom and decrease progressively downslope. Given the active phase transition zone above the 0 °C isotherm is the primary region for frost heave deformation, the findings suggest prioritizing enhanced replacement measures in this zone to maximize frost heave suppression efficacy.

Distribution characteristics of stress field of lining plate of canal

Figure 9 illustrates the distribution of normal frost heave force and tangential freezing force on the canal lining plate for different sand-gravel replacement thicknesses, as well as the normal and tangential stress cloud maps of the lining plate in Scheme 6. The distributions exhibit similar trends: both forces generally increased then decrease along the canal slope, with lower values at the canal bottom center and higher values at the ends (top and toe). Stress concentrations occurred at the slope toe and top due to bidirectional constraints between the slope lining and bottom lining plates. Notably, increasing the replacement thickness significantly reduced stress concentration at the slope toe. Without replacement, the peak normal frost heave force and tangential freezing force at the slope toe reached 3.715 MPa and 11.781 MPa, respectively. After implementing gradient replacement with sand-gravel at thickness of (20 to 50 cm, 30 to 70 cm, and 40 to 90 cm) for the slope (and corresponding bottom thicknesses), the normal frost heave force and tangential freezing force decreased to (2.799, 8.324) MPa, (2.220, 7.221) MPa, and (1.727, 6.045) MPa, respectively.

Compared with the non-replacement scheme (Scheme 1), reductions in normal frost heave force were 24.6%, 40.3%, and 53.5%, and reductions in tangential freezing force were 29.3%, 38.7%, and 48.7% for the respective replacement schemes listed above. This demonstrates that sand-gravel replacement significantly alleviated the stress at the slope toe. Although a slight increase in normal stress occurred at the canal bottom, the overall stress distribution of the lining plate became more uniform after replacement. The reduction in normal frost heave force exceeds that of tangential freezing force. This phenomenon can be attributed to the dual-phase anti-frost heave mechanism of the sand-gravel replacement. Firstly, the coarse-grained, porous structure of the replacement layer effectively blocks capillary water migration paths, which fundamentally suppresses ice lens formation and the development of normal frost heave forces by limiting water supply to the freezing front. Secondly, the compacted sand-gravel acts as a structural cushion that distributes frost heave stresses more uniformly and provides mechanical restraint against soil deformation, thereby effectively mitigating stress concentrations, particularly for the normal stress at the slope toe. From Scheme 1 to Scheme 4, stress reduction was relatively significant, whereas beyond Scheme 6, the rate of stress reduction gradually slowed. This pattern indicates that as the replacement thickness increased, the stress gradually decreased and the stress reduction effect tended to stabilize. Evidently, the gradient sand-gravel replacement method demonstrated remarkable effectiveness in reducing frost heave stresses and enhancing frost heave resistance.

Variation law of frost heave displacement of lining plate of canal

Figure 10 illustrates the frost heave displacement of the lining slabs at each measuring point in Section II (east–west oriented) and Section IV (north–south oriented) throughout a single freeze–thaw cycle. As the ambient temperature declined, the temperature of the foundation soil also decreased, which in turn led to an increase in the frost heave displacement of the lining slabs—with the displacement reaching its peak during the freezing period. However, the time at which the displacement peak appears varies for each measuring point, and the measuring points in the second section show longer peak durations. When temperatures rose and the soil thawed, frost heave displacement decreased. At the end of the freeze–thaw cycle, the middle of section II’s canal bottom and the upper right slope of section IV exhibited lower displacement than at the start, indicating thaw settlement. Conversely, other measuring points showed increased displacement, confirming the occurrence of residual frost heave.

For Section II, the peak displacement was the largest at the lower part of the left slope, followed by the canal bottom, and the smallest at the upper part of the right slope. This uneven distribution of displacement is attributed to the difference in solar radiation exposure between the two slopes of the east–west oriented canal. In comparison, the measuring points in Section IV showed more consistent trends in displacement, with only slight differences in their peak values. These findings provide critical insights into the freeze–thaw behaviors of canals.

To clarify how varying sand-gravel replacement thickness affects the distribution and magnitude of normal displacement in lining plates, a comparative analysis was conducted on the normal displacement cloud maps of lining plates under different schemes. Figure 11 illustrates the cloud map of normal displacement of lining plates under different schemes. The maximum normal displacement under the non-replacement scheme (Scheme 1) was significantly higher than in replacement schemes, indicating greater susceptibility to freeze–thaw expansion in canals without replacement. Following sand-gravel replacement, the maximum normal frost heave displacement of the lining plate occurred in the middle-to-lower section of the canal slope, above the slope toe. This area generally exhibited larger displacement values than the slope top and toe.

As the replacement thickness increases, the position of the maximum displacement on the canal slope shifted downward, indicating that sand-gravel replacement measures significantly enhanced the frost resistance of the canal slope. Moreover, increasing the replacement thickness not only reduced the peak normal displacement of the lining plate but also improved the displacement distribution uniformity. This effectively mitigated stress concentration at the slope toe and other critical areas. These results validate sand-gravel replacement as an effective anti-frost heave measure, providing theoretical and technical support for optimizing canal replacement designs.

Figure 12 illustrates the comparison of normal displacement of lining plate between different simulation schemes and on-site monitoring (Sections III and IV). Slight discrepancies exist between simulation and measurement results, with field frost heave displacements marginally exceeding simulated values (maximum deviation: 3.3%). This difference stems from the omission of water migration effects in the simulation. Nevertheless, results remain within acceptable accuracy thresholds, confirming the reliability of the numerical methodology.

As shown in Fig. 12, along the lining plate, normal displacement at the slope top was relatively low, peaked in the mid-lower section of the canal slope, decreased thereafter, and peaked again at the canal bottom. Although stress concentration occurred at the canal slope toe, normal frost heave displacement there was relatively small. This phenomenon is primarily attributed to bidirectional restraint exerted by the lining plate on the frost heave of the foundation soil at the slope toe. The peak displacement at the canal mid-bottom arises from the constraint exerted by the slope plates at both ends of the bottom plate.

Analysis of different schemes showed that from Scheme 1 to Scheme 4, normal displacement of the lining plate fluctuated significantly, with distinct peaks. In contrast, from Scheme 5 to Scheme 8, normal displacement stabilized and its distribution became more uniform. As replacement thickness increased, normal displacement gradually decreased, indicating that sand-gravel replacement effectively mitigated lining plate displacement caused by foundation soil frost heave.

To clarify the impact of the thickness of the replacement layer on the frost heave effect, based on the numerical model, the displacement values at positions corresponding to the monitoring points in the prototype test were selected for comparative analysis. Figure 13 shows the trend lines of the normal displacement of the lining plate at five measuring points under different schemes. As the thickness of the replacement layer increased, the normal displacement of the lining plate decreased, with the rate of decrease gradually slowing. Displacement differences between measurement points under the same scheme gradually decreased, tending towards uniformity. The maximum frost heave displacement of schemes 2 to 8 was reduced by 31.2%, 45.3%, 62.4%, 72.5%, 78.4%, 81.8%, and 85%, respectively. Comparison of the frost heave reduction rates under different schemes reveals that as the replacement thickness increased, the frost heave reduction rate gradually improved, indicating that the increase in replacement thickness has a significant effect on reducing frost heave.

When the replacement thickness reached a gradient change from 30 cm at the canal top to 70 cm at the canal bottom (Scheme 6), the frost heave reduction rate plateaued, revealing a critical thickness threshold. Beyond this value, additional thickness yields diminishing returns as effectiveness stabilizes. Design optimization should therefore target this critical range to balance frost heave resistance with economic efficiency, avoiding unnecessary material costs. When the replacement thickness gradients from 30 cm at the canal top to 70 cm at the canal bottom, the maximum frost heave displacement was 0.95 cm, meeting the allowable frost heave displacement requirements (0.5–1.0 cm) specified in the code for trapezoidal concrete-lined canals.

Comprehensive analysis of the canal’s hydrothermal characteristics, lining plate stress distribution, and frost heave behavior demonstrates that sand-gravel replacement effectively reduces both frost heave displacement and stress in canal linings. This technique promotes more uniform deformation and stress distribution while significantly enhancing frost heave resistance. Based on the frost heave reduction rate pattern, optimal engineering design recommends implementing a gradient sand-gravel replacement layer measuring 30 cm at the canal top to 70 cm at the canal bottom. This design achieves the optimal balance between economic efficiency and structural safety.

Discussion

This study explored the hydrothermal coupling and frost heave characteristics of cold-region lined canal foundations with gradient sand-gravel replacement via prototype monitoring and numerical simulation. The gradient replacement scheme with 30 cm at the top to 70 cm at the bottom reduced peak normal frost heave force by 40.3% and maximum displacement to 0.95 cm. This displacement meets the specification requirements of 0.5 to 1.0 cm, achieving a balance between anti-frost heave performance and engineering economy. The research findings offer theoretical support and practical guidance for the anti-frost heave design of sand-gravel replacement for trapezoidal concrete-lined canals in cold regions.

However, this study has certain limitations. The numerical model neglected latent heat of phase change and water migration and the foundation soil was simplified to a saturated state. Field monitoring data have validated the reliability of this simplified model. On-site monitoring lacked ambient wind speed records, and long-term durability of the sand-gravel layer under repeated freeze–thaw cycles remains unstudied. Future work should integrate water migration and unsaturated soil effects and extend field monitoring to address these gaps.

Conclusions

The gradient sand-gravel replacement measure could effectively optimize the distribution of temperature and moisture fields within the canal foundation. As the thickness of the replacement increased, the 0℃ isotherm gradually shifted downward, indicating an increase in freezing depth. The sand-gravel effectively suppressed water migration, progressively slowing the rate of freezing depth increase. Therefore, the gradient sand-gravel replacement significantly slowed the freezing rate of the foundation soil.

Increasing the replacement thickness significantly reduced the maximum frost heave displacement, normal frost heave force, and tangential freezing force of the canal lining. It also promoted more uniform stress and displacement distribution, minimizing stress concentration. Sand-gravel replacement substantially enhanced the canal’s frost resistance, effectively mitigating the risk of frost-heave-induced structural damage.

When the replacement thickness reached a gradient change from 30 cm at the canal top to 70 cm at the canal bottom, the frost heave reduction effect plateaued, exhibiting diminishing returns. Compared with the pre-replacement state, the maximum normal displacement, normal frost heave force, and tangential freezing force were reduced by 78.4%, 40.3%, and 38.7%, respectively. The maximum normal displacement of the lining plate was 0.95 cm, complying with the specification requirements. This design not only effectively achieves the project’s anti-frost heave objectives but also considers engineering economy, making it the optimal replacement thickness for trapezoidal concrete-lined canals in cold regions.

Data availability

Some or all data, models, or code that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ge, J. et al. Mechanical modeling for precast trapezoidal Canal under the influence of bi-directional Frost heave and field experimental verification. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 232, 104434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2025.104434 (2025).

Shi, L., Li, S., Wang, C., Yang, J. & Zhao, Y. Heat-moisture-deformation coupled processes of a Canal with a berm in seasonally frozen regions. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 207, 103773. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2023.103773 (2023).

Duan, K., Zhang, G. & Sun, H. Construction practice of water conveyance tunnel among complex geotechnical conditions: A case study. Sci. Rep. 13, 15037 (2023). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-023-42192-0

Li, Z., Liu, S., Wang, L. & Zhang, C. Experimental study on the effect of Frost heave prevention using soilbags. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 85, 109–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2012.08.008 (2013).

Ge, J. et al. Elastic foundation beam unified model for ice and Frost damage concrete Canal of water delivery under ice cover. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 36, 90–98 (2020).

Xiao, M. et al. Elastic frozen soil foundation beam model for trapezoidal Canal lined with concrete precast slabs in cold regions. J. Hydraul Eng. 54, 244–253 (2023).

Jiang, H., Liu, Q., Wang, Z., Gong, J. & Li, L. Frost heave modelling of the Sunny-Shady slope effect with Moisture-Heat-mechanical coupling considering solar radiation. Sol. Energy. 233, 292–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2022.01.040 (2022).

Cai, Z., Zhang, C., Zhu, X., Huang, Y. & Wang, Y. Improvement of capacity and safety protection technology for long-distance water delivery projects in cold regions. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 44, 1239–1254 (2022).

Grigg, N. S. Large-scale water development in the united states: TVA and the California state water project. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 39, 70–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2021.1969224 (2021).

Kong, L., Quan, J., Yang, Q., Song, P. & Zhu, J. Automatic control of the middle route project for South-to-North water transfer based on linear model predictive control algorithm. Water 11, 1873–1873. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11091873 (2019).

Tan, X. et al. Study on the influence of airflow on the temperature of the surrounding rock in a cold region tunnel and its application to insulation layer design. Appl. Therm. Eng. 67, 320–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2014.03.016 (2014).

Liu, H. et al. U. J. Study on the hydrothermal coupling characteristics of polyurethane insulation boards slope protection structure incorporating phase change effect. Sci. Rep. 11, 18195 (2021). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-97561-4.pdf

Wang, Z., Liu, S., Wang, Y., Liu, Q. & Ge, J. Size effect on Frost heave damage for lining trapezoidal Canal with arc-bottom in cold regions. J. Hydraul Eng. 49, 803–813 (2018).

Masters, I., Pao, W. K. & Lewis, R. W. Coupling temperature to a double-porosity model of deformable porous media. Int. J. Numer. Meth Eng. 49, 421–438. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0207(20000930)49:3%3C421::aid-nme48%3E3.3.co;2-y (2000).

Mu, S. & Ladanyi, B. Modelling of coupled heat, moisture and stress field in freezing soil. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 14, 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-232X(87)90016-4 (1987).

Guo, F., Li, G. & Cheng, M. An analysis of the influences of groundwater level changes on the Frost heave and mechanical properties of trapezoidal channels. Water Policy. 22, 1163–1181. https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2020.039 (2020).

Wang, Z. Establishment and application of mechanics models of Frost heaving damage of concrete lining trapezoidal open Canal. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 20, 24–29 (2004).

Wang, Z., Li, J., Chen, T., Guo, L. & Yao, R. Mechanics models of frost-heaving damage of concrete lining trapezoidal Canal with arc-bottom. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 24, 18–23 (2008).

Wang, Z., Liu, X., Chen, L. & Li, J. Computer simulation of Frost heave for concrete lining Canal with different longitudinal joints. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 25, 1–7 (2009).

Li, S., Wang, Z., Gao, L., Liu, Q. & Sun, G. Numerical simulation of Canal Frost heaving considering nonlinear contact between concrete lining board and soil. J. Hydraul Eng. 45, 497–503 (2014).

Liu, X., Wang, Z., Yan, C. & Li, J. Exploration on anti-frost heave mechanism of lining Canal with double films based on computer simulation. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 27, 29–35 (2011).

Li, Z., He, Y., Sheng, J. & Li, Y. A model-based experiment on the prevention of Frost heave in canals using soil-bags. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. 04, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.4172/2169-0022.1000189 (2015).

Teng, R., Gu, X., Xia, X. & Zhang, Q. Numerical simulation of Frost heave deformation of concrete-lined Canal considering thermal-hydro-mechanical coupling effect. Water 15, 1412. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15071412 (2023).

Jiang, H. & Tian, Y. Test for Frost heaving damage mechanism of rigid-soften composite trapezoidal Canal in seasonally frozen ground region. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 31, 145–151 (2015).

Guo, F., Li, G. & Cheng, M. A study of the insulating and Anti-Frost heave effects of polystyrene boards under molded bag concrete conditions. Water Policy. 23, 1030–1043. https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2021.127 (2021).

Guo, F. et al. A study of the insulation mechanism and anti-frost heave effects of polystyrene boards in seasonal frozen soil. Water 10, 979. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10080979 (2018).

Wang, Y., Wang, Z., Liu, Q. & Xiao, M. Experimental investigations on Frost damage of canals caused by interaction be-tween frozen soils and linings in cold regions. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 40, 1799–1808 (2018).

Li, S., Zhang, M., Pei, W. & Lai, Y. Experimental and numerical simulations on heat-water-mechanics interaction mechanism in a freezing soil. Appl. Therm. Eng. 132, 209–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2017.12.061 (2018).

Xu, J. et al. Frost heave of irrigation canals in seasonal frozen regions. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2019, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/2367635 (2019).

Li, S., Zhang, M., Tian, Y., Pei, W. & Zhong, H. Experimental and numerical investigations on Frost damage mechanism of a Canal in cold regions. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 116, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2015.03.013 (2015).

Zhang, D. & Guo, X. Effects of thermal insulation and anti-frost heaving in composite lining structures for a Canal in colmatage frozen soil. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 36, 122–129 (2020).

Zhu, Z. W., Ning, J. G. & Ma, W. Constitutive model and numerical analysis for the coupled problem of water, temperature and stress fields in the process of soil freeze–thaw. Eng. Mech. 24, 138–144 (2007).

Wang, W., Wang, Z., Li, S. & Sun, G. Numerical simulation of anti-frozen heave by replace-filling measures for lined Canal in seasonal frozen soil region. Agric. Res. Arid Areas. 31, 83–89 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The writers are thankful for the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 513798128),the National Key Laboratory of Water Disaster Prevention “the Belt and Road” Water and Sustainable Development Science and Technology Foundation (No. 2023nkms06), the Gansu Province Water Conservancy Science Experimental Research and Technology Promotion Project (No. 24GSLK019, 24GSLK024, 25GSLK053, and 25GSLK059), the Lanzhou University of Technology 2025 Young Teachers’ Interdisciplinary Research Cultivation Project (No. 062516), and the Lanzhou Science and Technology Plan Project (Science and Technology Support Special)(No. 2024-3-84).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 513798128),the National Key Laboratory of Water Disaster Prevention “the Belt and Road” Water and Sustainable Development Science and Technology Foundation (No. 2023nkms06), the Gansu Province Water Conservancy Science Experimental Research and Technology Promotion Project (No. 24GSLK019, 24GSLK024, 25GSLK053, and 25GSLK059), the Lanzhou University of Technology 2025 Young Teachers’ Interdisciplinary Research Cultivation Project (No. 062516), and the Lanzhou Science and Technology Plan Project (Science and Technology Support Special) (No. 2024-3-84).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to this work. Conceptualization, X.F. and F.Y.; methodology, X.F.; software, F.Y.; validation, L.W., G.L., and X.W.; formal analysis, F.Y.; investigation, G.L.; resources, X.F.; data curation, G.L. and F.Y.; writing-original draft preparation, F.Y.; writing-review and editing, X.F., J.W., and F.Y.; visualization, X.F. and F.Y.; supervision, X.F. and J.W.; project administration, X.F. and C.P.; funding acquisition, X.F., C.P., and J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, X., Ye, F., Pang, C. et al. Study on hydrothermal coupling and frost heave characteristics of trapezoidal concrete-lined canals with gradient sand-gravel replacement in cold regions. Sci Rep 15, 43974 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27749-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27749-5