Abstract

Understanding the size, shape, branching angles, and morphological features of blood vessels in human tissue remains challenging. To address this, we propose a multi-view hybrid encoder U-Net for segmenting renal artery vessels. The encoder in this model adopts a hierarchical structure, consisting of an upper encoder and a lower encoder. The upper encoder includes a lightweight convolutional neural network (CNN). In contrast, the lower encoder incorporates either CNN or Transformer modules, forming a flexible hybrid encoding mechanism that enhances feature extraction and representation. The model processes two-dimensional images from three orthogonal views, keeping the original width and height of the input image to preserve spatial resolution. This design helps maintain fine details of high-resolution images, thereby aiding in the capture of subtle features. Experimental results show that the Mean Surface Dice value (MSD) of this method reaches 0.852, and the Dice similarity coefficient (DSC) reaches 0.939 on kidneys not used in training. These findings suggest that the proposed approach is effective for detailed renal artery segmentation, although further validation on diverse datasets and modalities is required to establish its generalizability fully.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human organs and tissues are complex three-dimensional structures of interacting, spatially organized, and specialized cellular and organotypic functional units arranged in a hierarchy. These spatial relationships, three-dimensional morphology, and interactions collectively provide the basis for biological function for an intact organ like the kidney. Researchers have employed the Vascular Common Coordinate Framework (VCCF)1 as a primary navigation system to map cells, spanning all scale levels and offering a unique approach to identify cell locations using capillary structures as addresses. However, the limited understanding of these vascular structures has led to suboptimal results for the VCCF. Thus, researchers need to develop a method that can automatically and accurately segment vascular arrangements, allowing them to use real-world tissue data to address these gaps and enhance their understanding of vascularization throughout the body.

In most situations, human expert annotators manually annotate vascular structures, which is a slow and labor-intensive process. Completing each new dataset can take more than six months, even with skilled expert annotation. Due to variations in human anatomical structures, machine learning methods for these manually annotated data cannot be easily generalized to new datasets. Furthermore, image quality will also vary as Computed Tomography (CT) technology evolves. For instance, kidney images obtained via Hierarchical Phase-Contrast Tomography (HiP-CT)2 imaging technology feature resolutions ranging from 1.4 μm to 50 μm. These factors result in the challenge that standard deep learning methods perform well on one kidney organ dataset but show significantly reduced predictive performance on another kidney organ dataset. These issues highlight the need for more robust segmentation methods that can generalize across patients and imaging resolutions.

To address these challenges, this study aims to develop a robust and efficient 3D renal vessel segmentation method for HiP-CT images, which is crucial for subsequent analysis of vascular morphology (e.g., size, shape, branching angles, and other morphological features). Unlike previous studies that rely on manual annotation or are limited by poor dataset generalization, our approach explicitly addresses the large inter-patient variability and significant performance degradation under multi-resolution imaging conditions.

The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows: (1) We implement a multi-view strategy for slicing, processing, training, and inference of HiP-CT datasets, enabling consistent 2D learning while preserving 3D contextual information. (2) We propose a hybrid encoder U-Net architecture explicitly designed for multi-view image learning, combining the strengths of convolutional and Transformer-like components for robust feature extraction. (3) We apply a wide range of data augmentation strategies, including intensity and geometric transformations, to improve the model’s robustness and generalization under diverse imaging conditions. (4) We introduce a Boundary DoU Loss (BDULoss) to the renal vessel segmentation task, significantly improving boundary precision and the segmentation accuracy of small and thin vessels, which are often underrepresented in medical imaging datasets.

Related work

In the realm of research concerning the segmentation of hybrid networks employing Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Transformers, a study has put forth a hybrid autoencoder architecture known as TransCNN-HAE3. This architecture integrates both Transformer and CNN technologies, specifically aimed at enhancing image restoration tasks. By effectively merging global and local features, the quality of image restoration experiences a significant improvement. Furthermore, researchers have introduced a Hybrid CNN-Transformer Network (HCTNet)4, which synergistically combines the local feature extraction proficiency of CNNs with the global context modeling capability inherent to Transformers, thereby augmenting the segmentation accuracy of lesions in breast ultrasound images. Additionally, several studies have presented CTH-Net5, which successfully attains high-precision segmentation of skin lesions by amalgamating the strengths of CNNs and Transformers. Moreover, a particular study has proposed a Convolutional Neural Network combined with Transformer (CTransNet)6. This model significantly enhances the global feature modeling capabilities and boosts the performance of medical image segmentation through the integration of the Transformer within the CNN architecture.

These examples illustrate that hybrid networks are particularly effective in balancing the strengths of CNNs and Transformers: CNNs excel at capturing fine local spatial details. At the same time, Transformers are powerful in modeling the global context. For our task, this balance is crucial, since renal blood vessels include many thin and elongated structures that require both local precision and global continuity. Therefore, hybrid architectures offer a promising direction for addressing our problem of robust and generalizable vessel segmentation across multi-resolution HiP-CT datasets.

In recent years, notable advancements have been achieved in the study of human organ and tissue segmentation utilizing deep learning methodologies. A series of researchers introduced TransUNet7, an early endeavor aimed at integrating Transformers with U-Net8 for the segmentation of 2D medical images. This technique harnesses Transformers to encode labeled image patches within the convolutional neural network (CNN) feature map into an input sequence that effectively captures the global context. Concurrently, the decoder performs upsampling of the encoded features and integrates them with the high-resolution CNN feature map to attain precise localization. For three-dimensional images, such as renal vascular images, the U-Net with Transformers (UNETR)9 represents a significant breakthrough that merges Transformer technology with 3D U-Net frameworks. This approach employs a Transformer as an encoder to assimilate the sequential representation of the input volume while adhering to the established “U-shaped” encoder-decoder network architecture, which is adept at capturing global multi-scale information. The multi-organ segmentation task demonstrated optimal performance across various authoritative datasets. Nonetheless, this approach exhibits limited detection capabilities for small objects, such as slender blood vessels, and the comprehensive 3D Transformer encoder demands substantial GPU memory, particularly for high-resolution inputs. In human organ vascular segmentation, researchers have proposed a tensor-based graph cut method specifically for vascular segmentation. This methodology was implemented on the renal artery, where each voxel is modeled as a second-order tensor, effectively encapsulating both intensity and geometric information, thereby constructing a more precise model for vascular segmentation10, significantly enhancing the segmentation accuracy of small blood vessels. However, this method lacks end-to-end learning capabilities and considerably relies on preliminary probability maps generated by a pre-trained deep network. The quality of the initial segmentation notably constrains the overall segmentation accuracy. Furthermore, some researchers have introduced a dense bias connection methodology and developed a dense bias network (DenseBiasNet)11, which achieved a Dice similarity coefficient (DSC) of 0.884. This method is contingent on a manually crafted definition of challenging regions and does not integrate with the Transformer/self-attention mechanism. Another noteworthy study is the Swin-UNet12, which is based on the Swin Transformer. This research employs a layered Swin Transformer and a shifted window as an encoder to extract contextual features. A symmetric Swin Transformer decoder, equipped with a block expansion layer, has been designed to perform upsampling operations and restore the spatial resolution of the feature map. However, this method cannot directly model the three-dimensional spatial continuity of volumetric data, such as 3D Computed Tomography Angiography (CTA) or Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA), as it lacks the capability for Z-axis modeling and only learns features from a singular view. Beyond these CT and MRI-based segmentation approaches, deep learning has also been successfully extended to 3D ultrasound imaging. For example, A deep learning approach for segmentation, classification, and visualization of 3D high-frequency ultrasound images of mouse embryos13 demonstrates the feasibility of employing neural networks for complex embryonic imaging tasks, further confirming the versatility and generalizability of deep learning-based segmentation techniques.

In studies focusing on kidney structure and blood vessel segmentation using deep learning, researchers introduced the Multi-window ensemble GAN (EnMcGAN)14. Analyzing data from 122 patients, this method achieved an average Dice coefficient of 84.6%, successfully segmenting the kidney, tumor, artery, vein, and other structures. However, its model is complex, requires substantial computing resources for training, and the segmentation accuracy for small blood vessels still needs enhancement. A hybrid deep neural network was also presented, integrating a traditional CNN U-Net with a graph convolutional network (Graph U-Net)15 for initial and fine segmentation, yielding an average DICE coefficient of around 92%. This approach also demands considerable computational power, and accuracy for very small or low-contrast blood vessels remains challenging. For kidney and tumor segmentation, researchers proposed a 2.5D multi-layer feature fusion attention U-Net (MFFAU-Net)16, incorporating 3D information into 2D slices, optimizing memory usage while managing model complexity. Although effective, this study was not explicitly designed for blood vessel segmentation. Moreover, other researchers developed a weakly supervised vascular segmentation method, utilizing physiological structure simulation and domain adaptation17. This method was validated on 3D microCT scans of rat kidneys and 2D retinal images, although findings were primarily based on synthetic data, raising concerns about performance discrepancies with real data. Lastly, researchers have devised a method that accurately estimates the dominant area of renal blood vessels, combining a spatially aware fully convolutional network, tensor graph cuts, and Voronoi diagrams18. Evaluating this approach on 27 renal CT cases revealed an average Dice coefficient of 95% for renal segmentation, with an 80% centerline overlap rate for renal artery segmentation. However, the high computational complexity may hinder the efficiency of the practical application.

The above studies show that significant progress has been made in studying 3D organ and tissue images of the human body. Although many methods for medical image segmentation using artificial intelligence have been proposed, achieving a high-precision, efficient, and low-computation segmentation method for 3D renal blood vessels in multi-view and high-resolution images is still challenging.

Our methods

To develop an efficient and flexible method for renal vascular segmentation, this study focuses on four key components: (1) Multi-view Slice Generation and Volume Normalization: Slices at the original resolution on the XY-plane are first extracted from the complete 3D kidney volume of each patient to construct the whole 3D volume dataset. Before extracting 2D slices, each 3D volume is normalized using a percentile-based approach19, where intensity values are scaled according to the 10th and 99.8th percentiles. Values exceeding these percentiles are linearly scaled by a small factor (α = 0.01) to preserve extreme intensity information while maintaining numerical stability. Following normalization, the volumes are decomposed into 2D slices along the XY, XZ, and YZ orthogonal planes. The multi-view image slices are then shuffled to capture diverse spatial representations, enhancing the model’s ability to learn comprehensive segmentation features. (2) Preprocessing and Augmentation: Preprocessing techniques tailored to multi-view image data are investigated, and suitable image augmentation methods are applied to improve segmentation performance and model robustness. (3) Hybrid Model Architecture: An effective hybrid model combining a Transformer and a convolutional neural network (CNN) module is constructed. The CNN layers are utilized to extract local features. At the same time, the Transformer modules are employed to capture global contextual information, enabling the model to integrate both local and global representations synergistically. (4) Optimization Strategy: Various learning strategies are explored, leading to the adoption of a hybrid loss function and several novel optimization techniques to maximize model performance. The overall pipeline of the proposed method is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Dataset

The dataset utilized in this study is extracted from the “Hacking the Human Vasculature in 3D” competition hosted on the Kaggle platform20. This dataset includes high-resolution 3D kidney images and corresponding 3D segmentation masks of the renal vasculature for three distinct kidney samples. The kidney images were obtained using Hierarchical Phase-Contrast Tomography (HiP-CT), an advanced imaging technique capable of capturing ex vivo organ data at resolutions ranging from 1.4 μm to 50 μm. The training data consists of TIFF (Tagged Image File Format) scans derived from the three kidney datasets, where each image corresponds to a 2D slice of the 3D volume. These slices are sequentially organized along the Z-axis and are numerically arranged from top to bottom. The training labels contain the blood vessel segmentation masks of the images in TIFF format. The three kidneys are designated as Kidney_1, Kidney_2, and Kidney_3. Our training was conducted on Kidney_1, while the validation was performed on Kidney_3. The 3D volumes of Kidney_1 and Kidney_3 have a spatial resolution of 916 × 1303 × 2279, corresponding to the X, Y, and Z axes, respectively. The resolution of Kidney_1 was binned at 50 μm per voxel2. The entire 3D arterial tree has been densely segmented, starting from the glomerulus and extending up to two generations. Beamline BM052 was employed. For Kidney_3, a portion of the kidney (500 slices) was binned with BM05 at a resolution of 50.16 μm per voxel, utilizing dense segmentation.

Preprocessing

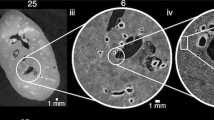

For Kidney_1, the 3D volume comprises 2,279 slices, indexed from 0 to 2,278 along the Z-axis. To enhance the model’s ability to capture essential features, reduce the influence of outliers, standardize the data scale, and improve training stability and efficiency, percentile-based normalization19 was first applied to the 3D volume. After normalization, the volume was divided into 2D slices in the XY, XZ, and YZ orthogonal directions. The obtained three-view slices are then shuffled, and 2D image augmentation is performed. Finally, the batched 2D slices are fed into our segmentation model. To better illustrate the slicing and segmentation process from three orthogonal views, Fig. 2 presents the slice visualization of Kidney_1 along the XY, XZ, and YZ axes.

A slice display of Kidney_1 from three views (a) The image set includes the 1400th slice along the Z-axis, the corresponding segmentation mask, and the overlay of the slice with its mask. (b) The image set consists of the 1000th slice along the Y-axis, the corresponding segmentation mask, and the slice overlay with its mask. (c) The image set includes the 700th slice along the X-axis, the corresponding segmentation mask, and the slice overlay with its mask.

Data augmentation

This study utilizes data from three kidneys: Kidney_1 is densely segmented, Kidney_2 is sparsely segmented, and Kidney_3 contains 500 slices with dense segmentation. Overall, the amount of annotated data is relatively limited. Data augmentation techniques are employed to tackle the challenges posed by data scarcity in training deep learning models. These methods effectively expand the scale and improve the quality of the training dataset, thereby contributing to the development of a more robust and generalizable model21. To evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed method, we conducted comparative experiments divided into two groups: one group employed a light data augmentation strategy. At the same time, the other adopted a heavy data augmentation strategy. This setup allows for a systematic assessment of the impact of augmentation intensity on model performance. The light data augmentation strategy is referred to as LAug. The heavy data augmentation strategy is referred to as HAug. LAug employs three image augmentation techniques, including basic strategies such as horizontal and vertical flipping as well as 90-degree rotation. HAug encompasses the methods of LAug and adds ShiftScaleRotate, RandomResizedCrop, and RandomBrightnessContrast. These augmentations are implemented using the albumentations package22. The specific settings of each augmentation strategy are detailed in Table 1.

Segmentation model

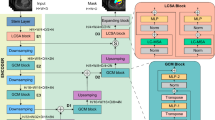

Compared to currently popular segmentation models, our proposed segmentation model has several advantages: (1) The input image scale is consistent with the original scale, ensuring that the segmentation model maintains high accuracy, especially in preserving the details of small arterial vascular structures and preventing any oversight or misjudgment. (2) Our model is designed to learn image features from three different views, and to address the varying scales of these images, we have developed a scale-adaptive training method that effectively resolves this issue. (3) The model can learn from multiple views of the 3D volume, allowing it to capture arterial information from various angles accurately. This multi-view learning approach enhances the model’s ability to understand and segment complex anatomical structures precisely. (4) The model encoder incorporates a hybrid architecture of CNNs and Transformers (ViTNets). By combining convolutional layers with Transformer modules, we extract local details through convolutional layers while capturing global features via Transformer modules, resulting in a synergistic effect of both global and local features. Our segmentation model is based on the improved U-Net structure, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

The proposed model maintains consistency between the input image size and the output mask, ensuring the width and height remain unchanged. The encoder architecture consists of two layers, into which the input tensor is fed simultaneously in both the upper and lower encoders. The upper encoder comprises two relatively shallow convolutional neural network (CNN) layers. This design is intentionally balanced to strike a balance between GPU memory usage and computational efficiency, as deeper CNN layers would be infeasible to train on Tesla T4 GPUs due to the high-resolution 3D HiP-CT volumes. The lower encoder includes either Transformer layers or CNN layers to facilitate a comparative analysis of their respective advantages. The decoder features five skip connections, with two coming from CNN layers and three from Transformer layers. These skip connections help recover low-level spatial information, thereby enhancing the precision of fine-grained segmentation7. The channels in the model’s decoder are set to [512, 256, 128, 64, 32].

Loss function

In this study, a combination of two loss functions is employed. One of them is SoftBCEWithLogitsLoss23, which integrates the strengths of traditional BCEWithLogitsLoss while incorporating label-smoothing techniques (e.g., applying Softmax or Sigmoid-based smoothing). This loss function is particularly well-suited for classification tasks involving imbalanced data or requiring fine-grained segmentation, as it enhances the model’s ability to distinguish between difficult categories. Given that the proportion of renal arteries relative to the entire kidney volume is extremely small, the ground truth labels for vessels are significantly imbalanced compared to the background, making the use of such a tailored loss function especially critical.

Given a model output x and a target label y, the BCEWithLogitsLoss is defined as follows:

where σ(x) is the Sigmoid function:

Substituting the Sigmoid function into the loss function, we get:

The other loss function used is the Boundary Difference over Union Loss (BDULoss)24, which is specifically designed to enhance boundary accuracy in medical image segmentation tasks. Traditional loss functions, such as Dice loss or Intersection over Union (IoU) loss, often struggle to effectively capture blurred or ambiguous boundaries. BDULoss addresses this issue by calculating discrepancies in boundary regions and integrating IoU metrics to optimize both region-level and boundary-level segmentation accuracy jointly. This makes it particularly effective for refining fine anatomical structures and subtle boundary delineations in medical images. In our study, the renal artery has many subtle boundaries, as shown in Fig. 2. This loss function is one factor contributing to our model’s improved performance. Given P as the predicted segmentation region and G as the ground truth segmentation region, the Boundary DoU Loss is defined as:

where ∪ denotes set union, ∩ denotes set intersection, and α ∈ [0,1) is a hyperparameter controlling the influence of the intersection region in the computation. Minimizing LDoU encourages the different regions (G ∪ P - G ∩ P) to be small (i.e., reducing false positives and false negatives) while giving controlled weight to the agreement area G ∩ P.

Finally, the total loss function is defined as:

Where W1 represents the weight of BCEWithLogitsLoss and W2 indicates the weight of BDULoss within the total loss function. After extensive experimental validation, we set W1 to 0.4 and W2 to 0.6.

Experiments

Experimental configuration

In this section, several training configurations are described. The same training strategy is employed in all experiments to compare the performance of different methods. The experiments were conducted on two Tesla T4 GPUs, utilizing the open-source Hugging Face Timm25 and Segmentation_models_pytorch packages26. Our segmentation models are trained on images at their original resolution without scaling. Since some transformer-based vision models require the input image’s width and height to be divisible by 32, the first stage of our proposed model involves cropping the input tensor’s width and height by the boundaries to ensure both dimensions are divisible by 32. As the boundary cropping is minimal, this guarantees that the resolution remains unchanged and that cropping does not affect the segmentation labels. At the end of the model, the output tensor is padded with zeros in width and height, ensuring that the final output tensor matches the original image’s dimensions. For the learning rate scheduler, we utilize “cosine annealing. " Typically, this learning rate scheduler with a restart mechanism is referred to as warm restart stochastic gradient descent (SGDR)27. The training optimizer employed is AdamW28. Next, the learning rate scheduler is configured as follows: (1) Use an initial learning rate of 0.0001. (2) The minimum learning rate is 0.000005. (3) The cycle length (T_max) for learning rate reduction is 1.

The training set comprises 4,494 multi-view slices generated from the HiP-CT kidney datasets (details in the Dataset section) . Each experiment is trained for a maximum of 30 epochs. Model checkpoints are selected based on the highest Mean Surface Dice (MSD) score observed on the validation set, ensuring precise boundary delineation and avoiding overfitting. The experiments were conducted on two Tesla T4 GPUs with a batch size of 1 per GPU (effective batch size of 2).

Evaluation metrics

During the experiment, we continuously evaluated the model’s performance using four key metrics: Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC)29, False Positive Rate (FPR), Recall, and Mean Surface Dice (MSD)30. The Mean Surface Dice (MSD) metric, calculated with zero tolerance, is critical to our model’s superiority. Let S1 and S2 represent the surface of the segmentation result and the surface of the ground truth, respectively. The surface distances of S1 and S2 are defined as follows:

where:

S1 and S2 denote the surfaces of the segmentation result and the ground truth, respectively.

d(p, S2) denotes the shortest surface distance from point p to S2.

τ is the tolerance threshold determining whether surface points are considered a match (for example, 1 mm, 2 mm, etc.).

The numerator counts the matched points within the threshold τ, while the denominator represents the total number of surface points.

The two terms in the equation evaluate the matching conditions of S1 and S2 separately, and their average produces the final MSD score.

Experimental results

As discussed in the Segmentation model section, a key advantage of the proposed model is its hybrid architecture, which effectively integrates CNNs and Transformers. The model incorporates five skip connections to enhance finer segmentation details by recovering low-level spatial information7. The following subsections present quantitative comparisons, ablation studies, competition benchmark results, and qualitative analyses.

Quantitative comparison of encoder architectures

The experimental results in Table 2 were obtained after 30 training epochs, using the best MSD as the evaluation criterion. All loss functions are based on the proposed hybrid loss function, and the data augmentation strategy follows the HAug method described in the Data augmentation section. The results demonstrate that the proposed method achieves superior performance in renal artery segmentation.

Ablation study

To evaluate the contribution of each component in our framework, we conducted ablation experiments focusing on the data augmentation strategy and the Boundary DoU Loss (BDULoss).

Effect of data augmentation

Table 3 reports the performance when replacing the proposed HAug with LAug. Compared to Table 2, the performance of all models declines, confirming that HAug provides more effective regularization and robustness. In particular, models with CNN-Transformer hybrid backbones exhibit a more pronounced performance drop, indicating that HAug is especially beneficial for enhancing generalization in architectures with stronger representational capacity.

Effect of BDULoss

Table 4 presents results obtained by removing BDULoss from the hybrid loss function (using only SoftBCEWithLogitsLoss). The performance degradation across all models highlights the critical role of BDULoss in refining boundary precision. By penalizing discrepancies along object boundaries, BDULoss helps the model achieve better alignment with anatomical structures. This indicates that BDULoss is a key contributor to the improved Mean Surface Dice, especially in challenging cases with fine vascular boundaries.

Comparison with kaggle competition and nnU-Net baseline

To comprehensively evaluate the proposed method, we compared it with the top five teams in the Kaggle competition as well as the widely adopted nnU-Net42. The Kaggle leaderboard reports two metrics: the Public Leaderboard (LB) score, based on a subset of the test data, and the Private LB score, which determines the final competition ranking. The official evaluation metric of the competition is Mean Surface Dice (MSD). The results in Table 5 demonstrate that our method achieves competitive performance compared to ensemble-based solutions, while maintaining a single-model framework with strong generalization ability.

The Public Test set consists of a continuous 3D part of a whole human kidney imaged with HiP-CT, originally scanned at 25.14 μm/voxel and binned to 50.28 μm/voxel (bin × 2) before segmentation. The Private Test set, in contrast, consists of another continuous 3D part of a whole human kidney, originally scanned at 15.77 μm/voxel and binned to 63.08 μm/voxel (bin × 4). These differences in resolution and binning settings make the Private Test significantly more challenging, highlighting the importance of robustness and generalization in segmentation methods.

As shown in Table 5, the top-ranked teams on Kaggle performed well; however, some teams experienced significant performance gaps between the public and private leaderboards. Our best approach achieved an MSD of 0.879 on the public leaderboard and 0.675 on the private leaderboard, respectively, ultimately ranking 8th and winning the gold medal. Compared to the nnU-Net baseline (MSD of 0.459 on private LB), our approach achieved significant improvement, demonstrating the effectiveness of our proposed hybrid encoder and multi-view learning strategy. While falling short of the top five on private LB, our single-model framework achieved a narrow performance gap between public and private LB, highlighting its strong generalization and computational efficiency. Some top-ranked solutions relied on ensemble strategies and heavy post-processing, or experienced significant performance gaps between public and private LB.

According to the Kaggle competition rules, each team was allowed to submit only two results, and the best was selected as the final official score. Our 8th-place result (Gold Medal) corresponds to the official Private Leaderboard score. However, we note that in our internal experiments, the proposed method achieved higher MSD scores (0.709) than the official submission, indicating the potential of our method beyond the reported ranking.

Qualitative analysis

To provide a clearer understanding of segmentation performance, the 2D slices of Kidney_3 were reconstructed into a 3D volume. Figure 4 displays a comparison between the predicted segmentation results and the ground truth labels from the axial, coronal, and sagittal views. The visualization highlights the consistency and accuracy of the proposed method across different anatomical planes, demonstrating significantly fewer false positives while maintaining high overall accuracy.

Visual comparison of segmentation results for Kidney_3 from three orthogonal views. Subfigures (a–c) correspond to the axial (XY), coronal (XZ), and sagittal (YZ) views, respectively. In each row, columns (1), (2), and (3) represent: (1) the ground truth overlaid with the kidney organ, (2) the predicted result overlaid with the kidney organ, and (3) the overlay of ground truth and predicted result with the kidney organ removed. This visualization highlights the consistency and accuracy of the proposed method across different anatomical planes.

In the qualitative comparison shown in the third column of Fig. 4, the orange regions represent correctly predicted areas (true positives), green regions indicate false positives, and red regions denote false negatives. The results demonstrate that our segmentation method yields significantly fewer false positives while achieving high accuracy and consistency.

Discussion and conclusion

In this study, we propose a hybrid encoder U-Net model, designed so that the width and height of the input tensor match those of the output tensor. This configuration allows the model to process three-view images of varying dimensions during training, contributing to improved segmentation performance of renal artery vessels. To assess the effectiveness of our method, we compared two data augmentation strategies: heavy data augmentation and light data augmentation. Experimental results show that the heavy data augmentation strategy improves MSD by 0.5%–2% compared to the light data augmentation strategy. Furthermore, incorporating BDULoss into the loss function provides an additional 0.8%–5.9% improvement in MSD. Our best method achieves 85.2% and 93.9% in MSD and DSC, respectively. Moreover, the resolution of the training images is 50 μm, while that of the validation images is 50.16 μm. In the Kaggle competition, the evaluation includes a Public Leaderboard (PB) test, where the test image resolution is 50.28 μm. On the PB test set, our method achieves an MSD of 86.9%, suggesting its ability to generalize across images with slightly differing resolutions. The proposed models vary from 79 M to 244 M parameters and are trained with a batch size of 2. Under the experimental configuration described in the Experimental configuration section, each training epoch required approximately 820–900 s on two NVIDIA Tesla T4 GPUs, resulting in a total training time of about 7.4 h for 30 epochs. For inference, a single 3D CT volume (whole kidney) required approximately 13 min, which includes slicing along the three orthogonal axes, 2D segmentation, and multi-view fusion with 8 Test-Time Augmentation (TTA) predictions. These results indicate that the proposed model is relatively efficient in terms of computational and memory cost, showing potential for practical applications, though the inference pipeline remains more complex than single-channel 3D models.

Based on the analysis provided, the proposed hybrid encoder U-Net with five skip connections contributes to improved renal artery segmentation performance. A comparison of the results in Tables 2 and 3 reveals that an effective data augmentation strategy reduces false positives from background areas and non-vascular tissues. Moreover, incorporating the BDULoss function into the loss framework improves the detection of renal arteries, tiny branches, and low-contrast regions, resulting in fewer missed detections. However, as discussed in the previous section, the resolution differences among the three datasets we evaluated are relatively minor. When our best-performing model is applied to the Kaggle Private Leaderboard (LB) test set, which has a voxel resolution of 63.08 μm, the score drops significantly to 71.0%. This indicates that substantial variations in image resolution, such as those obtained through Hierarchical Phase-Contrast Tomography (HiP-CT), may considerably degrade performance. Therefore, further improvements are necessary to enhance robustness in managing significant resolution disparities.

Our experiments identified the following limitations of this method: (1) The proposed method was trained and validated on the HiP-CT dataset. While it generalizes to different voxel bins, its performance on other modalities (e.g., MRI, ultrasound) remains untested. Moreover, performance degrades significantly when the voxel bins between the test and training sets differ more substantially. (2) The current inference pipeline requires multi-view slicing and fusion, which, while effective, incurs higher processing complexity and computational cost compared to single-channel 3D models. (3) Imaging small vessels near the resolution limit remains challenging, and further improvements may require higher-resolution imaging or specialized loss functions focused on fine structures. (4) Although we compared our model against top-ranked Kaggle teams and nnU-Net, broader benchmarking on diverse medical imaging datasets is still needed to validate the generalizability of the proposed method comprehensively. Furthermore, as shown in Table 5, while our single-model framework achieved competitive results, it did not outperform ensemble-based solutions adopted by some top teams, indicating room for further improvement in model accuracy.

Additionally, HiP-CT studies have indicated that the newly developed BM18 beamline at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF), which was completed in 2022, provides volume resolutions significantly higher than those currently available for human organs. This emerging scanning technology presents new challenges to our approach. Moving forward, we will continue to investigate advancements in this field and refine our method to better address the complexities introduced by high-resolution imaging technologies.

Data availability

The dataset used in this study is publicly available from the Kaggle competition “SenNet + HOA - 3D Human Vasculature Construction”, accessible at: https://www.kaggle.com/competitions/blood-vessel-segmentation/data. All experiments were conducted solely on this dataset and strictly adhered to the competition’s data usage terms.

Code availability

The source code used in this study has been made publicly available at: https://github.com/ynhuhu/Hacking-the-Human-Vasculature-in-3D.

References

Galis, Z. S. Chapter 37 - the vasculome provides a body-wide cellular positioning system and functional barometer: the vasculature as common coordinate frame (VCCF) concept. In (ed Galis, Z. S.) The Vasculome (453–460). Academic. (2022).

Walsh, C. L. et al. Imaging intact human organs with local resolution of cellular structures using hierarchical phase-contrast tomography. Nat. Methods. 18 (12), 1532–1541 (2021).

Xu, Q. et al. TransCNN-HAE: Transformer-CNN Hybrid AutoEncoder for Blind Image Inpainting. Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia (ACM MM 2022), 6122–6131. (2022).

Wang, J., Zhang, H. & Wang, Y. HCTNet: A hybrid CNN-Transformer network for breast ultrasound image segmentation. Med. Image. Anal. 85, 102753 (2023).

Chen, Q., Li, X. & Huang, Z. CTH-Net: A CNN and transformer hybrid network for skin lesion segmentation. Comput. Biol. Med. 169, 107643 (2024).

Luo, W., Zhang, Z. & Lin, H. CTransNet: convolutional neural network combined with transformer for medical image segmentation. Comput. Inform. 42 (2), 392–408 (2023).

Chen, J. et al. TransUNet: Transformers Make Strong Encoders for Medical Image Segmentation. ArXiv, (2021). abs/2102.04306.

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI). (2015).

Hatamizadeh, A. et al. UNETR: Transformers for 3D medical image segmentation. Proc. IEEE/CVF Winter Conf. Appl. Comput. Vis. (WACV). 574, 584 (2022).

Wang, C. et al. Tensor-cut: A tensor-based graph-cut blood vessel segmentation method and its application to renal artery segmentation. Med. Image. Anal. 60, 101623 (2020).

He, Y. et al. Dense biased networks with deep priori anatomy and hard region adaptation: Semi-supervised learning for fine renal artery segmentation. Med. Image. Anal. 63, 101722 (2020).

Cao, H. et al. Swin-Unet: Unet-Like pure transformer for medical image segmentation. In: (eds Karlinsky, L., Michaeli, T. & Nishino, K.) Computer Vision – ECCV 2022 Workshops. ECCV 2022. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 13803. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-25066-8_9. (2023).

Qiu, Z. et al. A deep learning approach for segmentation, classification, and visualization of 3-D high-frequency ultrasound images of mouse embryos. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 68 (7), 2460–2471 (2021).

Zhang, Y., Wu, J., Qiao, L., Li, S. & Ma, J. EnMcGAN: Multi-window ensemble GAN for renal multi-structure segmentation. ArXiv Preprint arXiv :210604130. (2021).

Gao, Y., Zhang, L. & Wang, K. Graph Convolution based cross-network multi-scale feature fusion for deep vessel segmentation. ArXiv Preprint arXiv :230102393. (2023).

Fu, Y. et al. 2.5D MFFAU-Net for accurate and efficient kidney tumor segmentation. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 23 (1), 189 (2023).

Ding, W. et al. Extremely weakly-supervised blood vessel segmentation with physiologically based synthesis and domain adaptation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2023 (pp. 198–208). (2023).

Hayashi, M., Kitasaka, T. & Mori, K. Precise Estimation of renal vascular dominant regions using spatially aware FCNs, tensor-cut and Voronoi diagrams. (2019). arXiv preprint arXiv:1908.01543.

Liu, X. et al. Deep learning for medical image analysis: Preprocessing and normalization, NeuroImage, 211, 116562. (2020).

Jain, Y. et al. Ryan Holbrook, and Addison Howard. SenNet + HOA - Hacking the Human Vasculature in 3D (Kaggle, 2023). https://kaggle.com/competitions/blood-vessel-segmentation

Shorten, C. & Khoshgoftaar, T. M. A survey on image data augmentation for deep learning. J. Big Data. 6, 60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-019-0197-0 (2019).

Buslaev, A. et al. Albumentations: fast and flexible image augmentations. Information 11 (2), 125 (2020).

Chen, L. C., Papandreou, G., Kokkinos, I., Murphy, K. & Yuille, A. L. DeepLabV3+: Encoder-Decoder with Atrous Separable Convolution for Semantic Image Segmentation. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). (2018).

Sun, F., Luo, Z. & Li, S. Boundary Difference Over Union Loss For Medical Image Segmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.00220. (2023).

Wightman, R. PyTorch image models [GitHub repository]. GitHub. (2019). https://github.com/rwightman/pytorch-image-models

Iakubovskii, P. Segmentation models PyTorch. GitHub repository. (2019). Retrieved from https://github.com/qubvel/segmentation_models.pytorch

Loshchilov, I. & Hutter, F. SGDR: Stochastic gradient descent with warm restarts. arXiv. (2017). https://arxiv.org/abs/1608.03983

Loshchilov, I. & Hutter, F. Decoupled weight decay regularization. arXiv. (2019). https://arxiv.org/abs/1711.05101

Taha, A. A. & Hanbury, A. Metrics for evaluating 3D medical image segmentation: Analysis, selection, and tool. BMC Med. Imaging. 15 (1), 29 (2015).

Nikolov, S. et al. Deep learning to achieve clinically applicable segmentation of head and neck anatomy for radiotherapy. Nat. Mach. Intell. 3 (6), 476–485 (2021).

Tan, M. & Le, Q. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), 6105–6114. (2019).

Lee, Y. et al. An energy and scale efficient neural network architecture for object detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.09730. (2019). Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/1904.09730

Hu, J., Shen, L., Sun, G., Vision & Recognition, P. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer and (CVPR), 7132–7141. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2018.00745

Liu, Z. et al. A ConvNet for the 2020s. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 11976–11986. (2022). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.01818

Brock, A., De, S., Smith, S. L. & Simonyan, K. High-performance large-scale image recognition without normalization. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR). (2021). Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2102.06171

Pan, Z., Xu, Y., Fu, J. & Deng, Z. TinyViT: Fast pretraining distillation for small vision transformers. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS). (2022). Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2207.10666

Vasudevan, S., Bhargava, P., Singh, M. & Others FastViT: A fast hybrid vision transformer using structural reparameterization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.14189. (2023). Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.14189

Girdhar, R., Singh, M., Joulin, A. & Misra, I. Hiera: A hierarchical vision transformer without the bells-and-whistles. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.00989. (2023). Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.00989

Liu, Z. et al. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 10012–10022. (2021). Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2103.14030

Yue, X., Zhao, X., Niu, S. & Others NextViT: Next generation vision transformer for efficient deployment in realistic industrial scenarios. arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.05501. (2022). Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2207.05501

Chen, S., Hu, Q., Pan, X. & Others CoaT: Co-scale conv-attentional image transformers. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS). (2021). Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2104.06399

Isensee, F., Jaeger, P. F., Kohl, S. A. A., Petersen, J. & Maier-Hein, K. H. nnU-Net: A self-configuring method for deep learning-based biomedical image segmentation. Nat. Methods. 18 (2), 203–211 (2021).

Clevert 1st Place Solution (code updated). Kaggle. Retrieved September 12, 2025, from (2024)., February 13 https://www.kaggle.com/competitions/blood-vessel-segmentation/writeups/clevert-1st-place-solution-code-updated

Lin, T. Y., Goyal, P., Girshick, R., He, K. & Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2999–3007. (2017).

Ryo 2nd Place Solution. Kaggle. Retrieved September 12, 2025, from (2024)., February 13 https://www.kaggle.com/competitions/blood-vessel-segmentation/writeups/ryo-2nd-place-solution

Tu, Z. et al. MaxViT: Multi-Axis Vision Transformer. Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 459–479. (2022).

ForcewithMe. 3rd Place Solution: Refine from Sparse to Dense. Kaggle. Retrieved September 12, 2025, from (2024)., February 13 https://www.kaggle.com/competitions/blood-vessel-segmentation/writeups/forcewithme-3rd-place-solution-refine-from-sparse-

Krashenyi, I. 4th Place Solution: Boundary DoU Loss is all you need! Kaggle. Retrieved September 12, 2025, from (2024)., February 13 https://www.kaggle.com/competitions/blood-vessel-segmentation/writeups/igor-krashenyi-4th-place-solution-boundary-dou-los

Tan, M. & Le, Q. EfficientNetV2: smaller models and faster training. Proc. 38th Int. Conf. Mach. Learn. 139, 10096–10106 (2021).

Han, D., Kim, J. & Kim, J. Deep pyramidal residual networks. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 6307–6315. (2017).

Panshin, I. 5th Place Solution: 3D Interpolation is all you need (updated with code). Kaggle. Retrieved September 12, 2025, from (2024)., February 13 https://www.kaggle.com/competitions/blood-vessel-segmentation/writeups/ivan-panshin-5th-place-solution-3d-interpolation-i

Kaggle Blood Vessel Segmentation Leaderboard. Retrieved September 12, from (2025). https://www.kaggle.com/competitions/blood-vessel-segmentation/leaderboard

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Key Project of the College of Engineering and Technology, Chengdu University of Technology (Project No.: C122024001).The authors would like to thank the Intelligent Technology Application Research Center and the Department of Electronic Information and Computer Engineering, College of Engineering and Technology, Chengdu University of Technology for their valuable support and cooperation during this research.

Funding

This work was supported by the Key Project of the Research Fund of Chengdu University of Technology, College of Engineering and Technology (Grant No. C122024001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Nan Yan, Linyuan Tang, and Ye Tao contributed equally to this work. Nan Yan led the project, including conceptual design, methodology development, and overall supervision. Linyuan Tang was responsible for model implementation, data preprocessing, and experimental analysis. Ye Tao contributed to algorithm development, evaluation metrics, and result interpretation.Jun Yao, Zhilin Guo, Meng Liu, and Jingwen Wang contributed to visualization, manuscript revision, and literature review. They also provided constructive suggestions during model optimization and experimental validation.All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, N., Tang, L., Tao, Y. et al. Multi-view hybrid encoder U-Net for 3D renal vascular medical image segmentation. Sci Rep 15, 44887 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28601-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28601-6