Abstract

Diabetes treatment requires reliable blood glucose monitoring to allow for appropriate adjustments and interventions. The conventional finger-prick test is associated with significant discomfort and poor compliance, highlighting the critical need for non-invasive, user-friendly solutions. This study proposes and validates an open-source, multi-wavelength spectroscopy system that combines visible (660 nm) and near-infrared (940 nm) wavelengths through six distinct transmission and reflection strategies. The system was validated through a rigorous three-phase process. Phase I established a preliminary regression model against a commercial meter using 500 controlled samples (\(R^2\) up to 0.8832). Phase II expanded this validation in 96 healthy volunteers, confirming high clinical acceptability (over 95% in Zone A, Clarke Error Grid) and a mean absolute error of 8.438 mg/dL relative to the commercial device. Critically, Phase III performed a definitive clinical validation, comparing our system and the commercial meter against the venous plasma glucose (VPG) gold standard. This analysis definitively established the clinical failure of all reflection-based strategies (resulting in Zone D errors), while confirming 100% clinical safety (Zones A/B) for all transmission modes. Notably, our multi-wavelength transmission (MT) strategy achieved 100% Zone A accuracy and demonstrated superior analytical precision (tighter ISO 15197:2015 compliance) than the ISO-compliant commercial benchmark when both were compared to the VPG. This work validates a transparent, open-source platform as a clinically reliable and accurate non-invasive alternative for intermittent glucose monitoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Blood glucose monitoring is crucial in managing diabetes and other metabolic disorders. Although conventional methods provide high accuracy, they often rely on invasive techniques that require frequent skin punctures, which leads to patient discomfort and an increased risk of infection1,2,3. These limitations have driven the development of non-invasive technologies aimed that aim to deliver accurate measurements while maintaining patient comfort and safety. Traditional glucose monitoring methods involve capillary blood sampling, which typically requires finger-pricking. Despite their high accuracy, these approaches introduce discomfort, trauma, and infection risks, rendering them unsuitable for continuous glucose monitoring (CGM)4,5,6,7,8. Although minimally invasive techniques, such as implantable biosensors and microneedles, have addressed some of these challenges, they still involve skin penetration and require periodic sensor replacement9.

To overcome these limitations, a plasmonic microwave Fano resonator with a high figure of merit (FoM) was developed for non-invasive glucose monitoring. Operating at resonance frequencies of 3.25 and 4.67 GHz, the sensor was fabricated on a Rogers 6010 substrate (\(\epsilon = 10.2\)) and optimized for detecting glucose variations in the interstitial fluid (ISF)10. Simulations utilizing a multilayered human tissue model (comprising skin, fat, and muscle) revealed strong electromagnetic field concentrations in the dermis and epidermis, where ISF levels were most prominent. The in vivo experiment comprised three phases: baseline glucose measurements at rest, glucose fluctuations induced by exercise, and rapid glucose variations following the consumption of 200 g of honey. The results indicated amplitude variations of up to 7 dB and a frequency shift of 30 MHz, with the primary resonance frequency (3.25 GHz) demonstrating a substantial sensitivity to glucose changes. The proposed sensor exhibited a five-fold improvement in sensitivity compared to conventional sensors, achieved a high quality factor (Q = 962), and enabled the accurate detection of glucose fluctuations. However, external factors such as skin sweat, sensor movement, body temperature, and tissue thickness have been identified as potential sources of measurement errors.

Beyond microwave sensing, terahertz (THz) spectroscopy and Raman scattering have also been investigated for non-invasive glucose monitoring. THz techniques exploit glucose absorption in the 0.1–2.5 THz range but face challenges related to low signal-to-noise ratios and spectral overlap with other biomolecules11. Similarly, Raman spectroscopy identifies specific vibrational modes of glucose but suffers from a weak voltage signal, necessitating enhancement techniques such as coherent anti-Stokes Raman Spectroscopy (CARS) and stimulated Raman Scattering (SRS) to improve sensitivity. Emerging photoacoustic and thermal infrared detection methods have further advanced non-invasive glucose monitoring. However, traditional thermal infrared approaches primarily measure glucose in the superficial skin layers, where interference from non-specific absorption signals, including skin lipids and hydration fluctuations, reduces the accuracy. To address these challenges, depth-gated mid-infrared photo-acoustic sensors (DIROS) provide depth-selective glucose localization in blood-rich skin capillaries while mitigating superficial skin interference. DIROS combines mid-IR photo-acoustic excitation with time-gated technology, enabling glucose signal isolation at depths exceeding 100 \(\mu\)m and achieving clinically relevant blood glucose detection. Compared to ISF-based methods, DIROS demonstrated superior performance in glucose tolerance tests on mice, achieving a root mean square error of cross-validation (RMSECV) of 34 mg/dL, substantially outperforming the 47 mg/dL observed for bulk ISF measurements. Despite these advancements, several limitations remain to be addressed. Current experiments have been conducted exclusively on mice, with human clinical trials hindered by regulatory constraints, such as EU MDR 2017/74512. Furthermore, physiological factors such as sweat, skin moisture, and variations in body temperature can affect the signal quality and measurement accuracy. Interference from laser oscillations and electronic noise, although partially mitigated by averaging multiple measurements, necessitates additional optical reference systems to enhance the stability. The current measurement and data processing time (1.5 seconds per spectrum) are unsuitable for real-time applications, and the measurement area is constrained to thin, minimally sweaty regions, such as the earlobes or nail beds. Although interference from lactate and albumin is considered negligible, high concentrations of other compounds, such as lipids and proteins, may affect the measurement results.

The non-invasive glucose monitoring device from DiaMonTech uses mid-infrared (Mid-IR) spectroscopy with quantum cascade lasers (QCLs) and the principle of photothermal deflection. Pulsed laser light (8–11 \(\upmu\)m) passes through the skin to excite glucose molecules in the interstitial fluid, causing a very small temperature change. This change is captured by a mirror system and a Pyrocam sensor to make sure the laser beam is focused correctly at the measurement point. The signal is then converted into optical data to estimate glucose levels. The system has been clinically tested on two platforms: D-Base and D-Pocket. Each measurement takes about 10 seconds, with more than 50 tests possible per charge. In trials involving 100 volunteers and 36 diabetic patients, 98.6% of the results fell within zones A and B of the Clarke error grid, and the mean Absolute Relative Difference (mARD) ranged from 10–20%, which is similar to that of early invasive devices. The main advantages are that it is non-invasive, painless, fast to operate, and can connect directly to a mobile app13.

An IoT-enabled wearable glucose monitoring (iGM) system, leveraging red and near-infrared (NIR) spectra, was developed and integrated with the AWS IoT Core for real-time data transmission4. The device employs an ESP32 IoT platform and a custom sensor array to measure glucose levels through light reflection and absorption at the wrist or earlobe. The experimental results demonstrated that the iGM device achieved 98.82 % accuracy after 10 hours of fasting and 98.04 % accuracy two hours post-meal, outperforming many traditional CGM systems. Cloud integration facilitates continuous monitoring, enabling timely interventions and enhancing the patient’s quality of life. Additional advantages include reduced infection risk, portability, and compatibility with open-source software, making it a scalable solution for both clinical and home settings. However, limitations remain, such as reliance on an Internet connection, which restricts real-time application in low-resource settings, and susceptibility to motion artifacts and environmental disturbances that may affect the measurement precision.

To address these challenges, a novel NIR-based sensor system (niGLUC-2.0v) was developed, employing a 940 nm wavelength and a 900–1700 nm detector for blood glucose monitoring at the fingertip and wrist5. The system was validated in 101 volunteers, including diabetic and non-diabetic volunteers. A machine learning-based data analysis framework incorporating ridge regression (RR) achieved superior accuracy, with a Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of 0.15 and Mean Squared Error (MSE) of 0.22 for the fingertip sensor, and an MAE of 0.06 and MSE of 0.006 for the wrist prototype. Bland–Altman analysis confirmed a strong agreement between the predicted and reference glucose levels, with 98 % of data points within ± 1.96 standard deviations. Additionally, 100 % of the data fell within Zone A of the Clarke Error Grid, indicating high clinical reliability. Despite these promising results, several challenges remain. Although correction algorithms mitigate the variations in skin pigmentation and ambient light, minor errors remain. The device’s sensitivity to positioning and motion artifacts necessitates further optimization for continuous and real-time monitoring of blood glucose levels. Nevertheless, niGLUC-2.0v provides a cost-effective ($87.35), portable, and accurate non-invasive glucose monitoring solution. Among the various non-invasive techniques, NIR spectroscopy remains the most promising due to its ability to penetrate tissues and target glucose-specific absorption wavelengths14. Advancing this field requires integrating optical measurement strategies with computational techniques to enhance their accuracy, robustness, and clinical applicability.

Within this optical domain, recent efforts have bifurcated into two distinct methodological approaches: static absorption spectroscopy and dynamic, pulsatile photoplethysmography (PPG)15,16. The latter PPG, which underpins emerging pre-commercial systems such as QuickGly15,17, isolates the time-varying, pulsatile component of the signal. This method, often using visible-light LEDs, analyzes the AC signal modulation caused by arterial blood volume changes to derive correlations with glucose15 and even HbA1c17,18. While this approach has shown high correlation in some studies and may inherently mitigate certain static confounders, it remains exceptionally vulnerable to motion artifacts and is highly dependent on complex, non-linear models to deconvolve the signal from factors such as SpO2 variation.

This study proposes and validates an open-source, multi-wavelength optical system combining visible (660 nm) and near-infrared (940 nm) spectroscopy. Six distinct measurement strategies were analyzed, encompassing both transmission and reflection modalities, to systematically identify a viable pathway for non-invasive sensing. The system’s performance is validated through a comprehensive three-phase methodology: (Phase I) an initial regression model screening using 500 samples benchmark against a commercial capillary meter; (Phase II) a larger-scale clinical validation in 96 healthy volunteers to establish broad clinical acceptability; and (Phase III) a definitive, intensive clinical trial comparing our strategies and the commercial meter in a analysis against the VPG gold standard. Finally, the complete hardware characterization, including Noise Equivalent Power (NEP) and long-term drift analysis, will define the fundamental limitations and robustness of the platform. This work aims to establish a transparent, rigorously validated, and accessible open-source benchmark for non-invasive, intermittent glucose spot-check monitoring.

In contrast, the this study building upon our prior work with open-source, multi-wavelength spectroscopy19,20 focuses on the first approach: static absorption spectroscopy. This method analyzes the total, non-pulsatile attenuation of light through a stable tissue volume. We posit that by rigorously validating a multi-modal (transmission and reflection) system against the venous plasma gold standard, we can establish a transparent, robust, and accessible open-source platform. This work addresses the critical need for a verifiable benchmark for intermittent, spot-check monitoring as a direct, non-invasive alternative to invasive finger-prick tests, thereby complementing, rather than competing with, the dynamic tracking goals of PPG-based systems.

The measurement of blood glucose by NIR spectroscopy relies on the principle of light absorption by glucose molecules within the NIR spectrum, which ranges from 600 nm to 2500 nm. In this region, glucose exhibited distinct absorption bands corresponding to vibrational overtones and combinations of the C-H, O-H, and C-O bonds. Among these, wavelengths around 940 nm are substantial due to their strong absorption by glucose, making them ideal for non-invasive glucose sensing. When light interacts with biological tissues, it is absorbed and scattered by glucose and other components such as water, hemoglobin, and lipids. Under ideal conditions with a homogeneous and non-scattering environment. The Beer-Lambert law shows the relationship between absorbance and glucose concentration as shown in (1).

where I0 is the incident light intensity (mW), I is the transmitted light intensity after passing through the tissue (mW), \(A\) is the absorbance, α is the molar absorption coefficient (L mol-1cm-1), \(c\) is the concentration of the absorbing glucose (mol L-1), and d is the optical path length (cm). Absorbance (A) is linearly proportional to glucose concentration (c) under ideal conditions, allowing for the estimation of glucose levels using measured light intensities. However, we acknowledge that biological tissue, such as a finger, is a highly scattering and heterogeneous medium, which makes the light path complex and makes it impossible to strictly apply the Beer-Lambert law directly. Therefore, this study uses a realistic approach. We assume that there exists a quasi-equivalent relationship between the measured voltage signal (from transmitted or reflected light) and the glucose concentration. The main goal is to construct and validate this empirical relationship using the method of reproducing the actual measurement data, rather than relying on an exact model. Factors such as scattering effects, relative source-detector distance, and biological variability are considered as source noises that will be partially modeled in the processing.

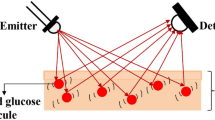

The NIR region presents challenges, including scattering effects from tissue heterogeneity, interference from overlapping water absorption and other biomolecules, and signal attenuation as tissue depth increases. Fig. 1 shows the system’s operating principle, which uses both the transmission and reflection measurement strategies to measure light-tissue interactions.

System architecture and working principles of the proposed non-invasive glucose monitoring device: (a) overall system architecture showing data collection, storage, and transmission to cloud platforms, (b) physical design of the glucose monitoring device with light source emitters and photo-detectors, and (c) operating principle using reflection and transmission measurement strategies for glucose monitoring.

The transmitted or reflected light from the fingertip is tuned to the glucose concentration in the blood because glucose molecules absorb specific wavelengths of light. This dual-mode method takes advantage of the optical characteristics of glucose to provide accurate, non-invasive blood glucose monitoring while allowing real-time data integration with cloud systems and overcoming the limitations of conventional invasive methods.

Methodology

Rationale for selecting a multi-frequency coherent light source

The proposed non-invasive method for blood glucose determination uses NIR radiation to detect the wavelengths characteristic of glucose absorption. As shown in Fig. 2(a), a wavelength of 940 nm, or a broader range from 920 nm to 980 nm, was selected because of its strong absorption by glucose molecules. This range enables the capture of signals directly correlated with glucose concentration levels21,22. Figure 2(b) shows the wavelength-dependent penetration depth of the NIR light through the skin. Light within the 600–1300 nm range achieves a penetration depth exceeding 3 mm, allowing sufficient interaction with blood glucose for signal acquisition19,20,23,24. This depth ensures that the radiation traverses sufficient tissue to yield glucose-dependent signal variations that are critical for accurate measurements.

However, as shown in Fig. 2(c), the energy conversion efficiency of sensors operating in the 920 nm to 980 nm wavelength range is less than 2.0 %25,26,27. Combining the glucose-specific 940 nm wavelength with the higher-efficiency 660 nm wavelength, which is strongly absorbed by hemoglobin, was assumed to provide a ratiometric correction for blood volume fluctuations, enhancing overall signal stability and reliability. This method enhances performance and ensures improved sensitivity and reliability for blood glucose quantification.

Hardware architecture

Figure 3 shows a non-invasive optical system designed for glucose measurements. The system uses a Light-Emitting Diode (LED) driven by a demultiplexer and a controlled current source to emit light through the user. The photodiode detects the transmitted or reflected light and converts it into a corresponding current signal. This signal was processed using a trans-impedance amplifier (TIA) to enhance the weak photocurrent and convert it into a voltage signal. Subsequently, a low-pass filter (LPF) removes the high-frequency noise, and a differential amplifier further amplifies the signal for an accurate analysis. The processed signal was then sent to a microcontroller that interpreted the data and displayed the results on an integrated display.

The booster circuit (Fig. 4(a)) uses a 3.7 V lithium-ion battery as input and boosts it to 7.0 V using the MT3608L converter. The output voltage is set via feedback resistors \(R_{8}\) and \(R_{6}\), as calculated by (2).

Power supply design for the proposed system: (a) booster circuit architecture using MT3608L for voltage regulation and (b) dual power supply circuit providing +5 V and −5 V outputs for stable operation. Figures (a) and (b) were created using EasyEDA (Standard) version 6.5.46 (https://easyeda.com).

The dual power circuit (Fig. 4(b)) takes 7.0 V input and generates isolated \(\pm 5\,\text {V}\) outputs using a DC-DC converter. Output voltages are determined by (3).

The device’s hardware was engineered to operate in two measurement strategies: a single light source measurement strategy or a multi-wavelength measurement strategy that combines 660 nm and 940 nm. The LEDs used were VSMD66694 dual-color diodes, featuring peak wavelengths of 660 nm (red light) and 940 nm (infrared), selected for their high radiant power, reliability, and stable performance under challenging operational conditions. The output power of the two diode sources was regulated to ensure that the optical power did not exceed 0.39 mW. This adherence to safety standards meets the requirements of Class I laser, ensuring user protection from the potential hazards associated with laser exposure during operation. The LED control circuit is shown in Fig. 5 uses a 74HC4053 digital switch as a demultiplexer, providing a supply voltage of 5 V for each LED, and the current for each LED is calculated based on (4).

Signal acquisition block for glucose measurement: (a) schematic of LED control and (b) transimpedance amplifier, low-pass filter, multiplexer, and differential amplification circuits. Figures (a) and (b) were created using EasyEDA (Standard) version 6.5.46 (https://easyeda.com).

Figure 6 shows the relative power and current of the LED at 660 nm (Fig. 6(a)) and 940 nm (Fig. 6(b)), the black points show the measured values, and the red line shows the theoretical values. The experiments used a Tektronix DMM4050 to measure the current and a Thorlabs PM100D power meter to measure the optical power. To ensure the Class I laser standard, in the single-wavelength measurement strategy, the current was adjusted to 2.0 mA, and in the multi-wavelength measurement strategy, the current did not exceed 1.5 mA28. Based on two power–current curves, the system can be flexibly configured to operate in either single- or multi-wavelength modes while ensuring that the total optical output power of the entire system remains within the Class I laser safety limit.

The signal acquisition block shown in Fig. 5(b) shows the TIA circuit, a LPF, a multiplexer, and a differential amplifier. The current from the photodiode in each measurement strategy was converted to voltage through the TIA circuit with a conversion factor based on (5).

In the system, \(R_5\) was chosen as 100 \(k\Omega\), corresponding to 100,000 times amplification. To ensure that the signal was not affected by high-frequency noise during the measurement and conversion of current to voltage, a LPF circuit was used to remove high-frequency noise signals, and the output signal was accurate to improve the quality of the processed data. The low-pass stage \(R_{31}\) and \(C_{44}\) are followed by the integrator stage of \(R_{30}\), \(C_{43}\), and the opamp, thus creating multiple low-pass feedback. Moreover, the presence of positive feedback \(R_{29}\) should allow for Q control. In the design, the value of \(C_{43}\) (1 nF) is selected and calculate \(C_{44} = nC_{43}\), where n is the capacitance spread and meet the condition \(n \ge 4Q^2(1 + H_0)\). The resistance values were calculated based on the (6).

where \(H_0\) (1) is the DC-gain magnitude, Q (about 1.053) is the quality factor, and \(f_c\) (10 kHz) is the cutoff frequency. After the signal is processed, a multiplexer is used to select the signal from the reflected or transmitted measurement strategies and send it to a differential amplifier, which amplifies the voltage value to a suitable level for the microcontroller to process. When port S1 of the 74HC4053 is activated at a high level corresponding to SS1 (reflective measurement strategies) connected to different amplifiers, port S2 is activated at a high level corresponding to SS2 (transmissive measurement strategies) and connected to different amplifiers. The output voltage of the differential amplifier was calculated using (7).

where \(V_1, V_2\) are the input signals of U9 and U7 respectively, with \(V_1\) connected to the ground and \(V_2\) connected to the output of the multiplexer. The value is chosen to satisfy the condition \(R_{19}\) = \(R_{18}\), \(R_{13}\) = \(R_{7}\), and \(R_{14}\) = \(R_{16}\).

Figure 7 shows the control and data-storage blocks of the device. The microcontroller used in this system was an ESP32 Node MCU that supports both Wi-Fi and Bluetooth. It serves as the central controller for managing the LEDs and processing signals received from the signal-conditioning block of the circuit. When connected to Wi-Fi, the ESP32 transmits the measured data to a designated web server for remote access and monitoring. Simultaneously, the data were stored on a memory card to ensure data integrity and to prevent data loss during data collection.

Microcontroller-based control and data storage system for glucose monitoring. Workflow for data acquisition, display, and wireless transmission to cloud storage. Figure was created using EasyEDA (Standard) version 6.5.46 (https://easyeda.com).

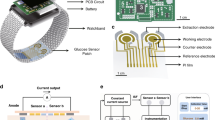

The proposed hardware design for the non-invasive glucose monitoring device incorporates a compact, multilayered PCB, as shown in Fig. 8. The PCB layout consists of two layers optimized for signal routing and electrical noise reduction. The top layer manages high-frequency analog and digital signal processing circuits, whereas the bottom layer is dedicated to power management, information communication modules, and grounding, ensuring a stable operation.

PCB layout design for the glucose monitoring device. Two-layered PCB with optimized signal routing, noise reduction, and power management. Figure was created using EasyEDA (Standard) version 6.5.46 (https://easyeda.com).

Design of the casing for the system

The outer casing of the system was designed with dimensions of 72\(\times\)44\(\times\)68 mm, which is suitable for clamping on the fingertip to continuously monitor glucose levels, as shown in Fig. 9. The compact and ergonomic design ensures user comfort during extended use while ensuring portability for daily activities. The housing material was selected as lightweight, medical-grade plastic to ensure durability, minimize weight, and meet the safety standards for skin contact. Ventilation slots are integrated to prevent internal components, including LEDs and photodiodes, from overheating.

The internal layout of the housing was designed to accommodate the light source components, including multi-wavelength LEDs (660 nm and 940 nm), photodiodes for both transmissive and reflective measurement strategies, and signal processing circuitry. The LEDs and detectors were precisely aligned to minimize the signal loss and optimize the light transmission through the tissue. A small compartment was integrated for power, ensuring a snug fit for the rechargeable lithium-ion battery and supporting its long-term use.

The outer casing of the proposed system: (a) orthographic projection views, and (b) exploded 3D view of the assembly. Figures (a) and (b) were created using AutoCAD 2023 (Autodesk Inc., San Rafael, CA, USA; https://www.autodesk.com/products/autocad/overview).

The housing included a clamping mechanism with a soft silicone pad to provide a stable and secure attachment to the fingertip while preventing discomfort to the wearer. The overall design prioritizes functional efficiency and user experience, ensuring that the device is suitable for continuous glucose monitoring.

Development of data analytic framework

The signal analysis framework is shown in Fig. 10, the signal obtained from the finger was converted into a voltage signal through the data acquisition block. The data were processed using a data analysis block. The proposed signal analysis method aims to quantify the physiological parameter glucose concentration in body fluids, such as blood, by correlating the measured signal intensities with glucose levels. Signal measurements across different wavelengths and measurement strategies were processed using computational techniques, including linear regression and the least-squares method. These measurement strategies assume a linear relationship between the measured voltage signal and the glucose concentration in the analyzed body fluid.

Figure 11 shows the measurement process of the proposed system. First, the system performed a power-supply test for the blocks. The system tests the light source emission strategies, including those for single or multiple wavelengths, as well as the reception strategies for reflection and transmission. The current signal obtained from the photodiode was converted into a voltage using a TIA circuit. This signal was converted into a digital signal using an analog-to-digital converter and fed into the prediction model.

Measurement process of the proposed non-invasive glucose monitoring system. The flowchart illustrates the complete operational sequence, from system power-up and selection of measurement strategies to signal acquisition and processing. The processed digital signal is fed into a predictive model to estimate the blood glucose value, which is then displayed and stored on an SD card or in cloud storage. The highlighted section (in red) shows a proposed feature for adaptive, user-specific calibration. This loop allows a user to input a reference value from a conventional invasive device, enabling the system to perform an error evaluation. Based on this new data point, the system is designed with the capability to retrain and update the predictive model, aiming to improve its personalized accuracy over time. It is important to note that this adaptive retraining feature represents a future implementation and was not utilized in the fixed-model validation performed in this study.

In this study, linear regression models considered the glucose concentration values in the fluid as \(x_i\) and the measured signal values as \(y_i\), with \(i=1,2,3,...,n\) representing the individual measurements. The dataset consists of paired values \((x_i, y_i)_i\) obtained from \(n\) measurements. The analysis method seeks to derive a function \(f(a_i, x_i)\) as shown in (8).

where \(a_i\) is the model parameter and \(b_i\) is a random error term with an expectation of 0. This formulation ensures that the regression approach minimizes the deviation between the observed and predicted signal values, enabling the calibration of glucose levels based on the measured signals, as shown in (9).

The least-squares method is employed to determine the parameters \(a_i\) such that the chi-squared (\(\chi ^2\)) value is minimized. Using differentiation, the least-squares optimization problem was formulated. Assuming that the function to be fitted is \(f(a_i, x_i) = \alpha + \beta x\), where \((a_1, a_2) = (\alpha , \beta )\), the objective function is expressed as shown in (10).

To find the optimal parameters \((\alpha , \beta )\), the system of equations derived from setting the partial derivatives of \(F(a)\) to zero is as in (11).

This system was solved to obtain the parameters \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\), which define the linear regression model. The prediction results were displayed on a screen and stored on an SD card or cloud storage.

If a value from an invasive device was entered, the system performed an error assessment and retrained the model using the added data. To evaluate the performance of the proposed model, the total error was minimized by comparing it with both linear and non-linear measurements.

The MAE \(e_M\) is shown in (12).

where \(V_{MD}\) is the minimal deviation value, \(V_M\) is the measured value, and \(n\) represents the number of measurements.

The mARD is shown in (13).

The RMSE is shown in (14).

where \(G_{\text {predicted}}\) is the physiological parameter concentration predicted by the linear regression model and \(G_{\text {reference}}\) is the concentration measured using an invasive device.

The estimation process involved multiple iterations, with 400 to 500 measurements taken per session. The final predicted concentration value \(V_G\) was calculated as the mean of all individual measurements, as shown in (15).

This iterative approach ensures improved reliability of the predicted physiological parameter concentration, providing a solid foundation for non-invasive sensing methodologies. The pseudocode for the process is shown in Algorithms 1 and 2, respectively.

Results

Ethics statement

The safeguards and protocols of this study were approved by the ethics committee of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City (IRB-VN01002/IRB00010293/FWA00023448). This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after they had been provided with a complete description of the study. They were asked if they had taken any medications at least 1 day before the test, and were not allowed to smoke, engage in strenuous physical activity, and eat or drink any food or drink for at least 2 hours before the study.

Device characterization and noise analysis

Noise equivalent power

The custom-built optical system’s noise equivalent power (NEP) was evaluated to establish its fundamental electronic sensitivity limit. The NEP was determined by measuring the system’s signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and the incident optical power (\(P_{\text {in}}\)) within the defined noise-equivalent bandwidth (\(\Delta f\)) of the system, calculated as \(NEP = P_{\text {in}} / (SNR \times \sqrt{\Delta f})\).

All measurements were conducted in a dark environment to eliminate ambient light. The system noise (\(V_n\)) was quantified as the RMS voltage (0.0001 V) of the output signal with the LEDs deactivated (dark state). The effective noise bandwidth (\(\Delta f\)) was 250 Hz, defined by the Nyquist frequency of the 500 Hz sampling rate. The signal voltage (\(V_s\)) and corresponding incident optical power (\(P_{\text {in}}\)), measured by a calibrated power meter (Thorlabs PM100D), were recorded for both channels.For the primary 940 nm sensing channel, an input power of 112.9 \(\mu\)W produced a signal of 1.1399 V, yielding a high SNR of 11,399. This corresponds to a calculated NEP of 626 pW/\(\sqrt{Hz}\). For the 660 nm reference channel, an input power of 130 \(\mu\)W generated a 0.7422 V signal (SNR = 7,422), resulting in an NEP of 1.11 nW/\(\sqrt{Hz}\) (Fig 12).

Raw time-series data (500 samples) used to determine the system's SNR and NEP. Red lines indicate the mean signal (Vs) or the RMS noise (Vn): (a) signal trace for the 660 nm channel, showing fluctuations around the mean signal (Vs) of 0.7422 V and (b) signal for the 940 nm channel, showing fluctuations around the mean signal (Vs) of 1.1399 V, and (c) the RMS noise (Vn = 0.0001 V) defines the system's sensitivity limit.

These NEP values confirm the high electronic sensitivity of the photodiode and transimpedance circuitry, indicating that the system’s electronic noise floor is sufficiently low. However, this analysis underscores a critical limitation: the primary challenge in non-invasive glucose sensing is not the electronic NEP but the physiological signal-to-noise ratio. The optical modulation induced by physiological glucose variations (optical power variation due to glucose, \(\Delta P_{\text {glucose}}\)) is orders of magnitude smaller than the total incident power (\(P_{\text {in}}\)) and is superimposed on a massive dynamic background dominated by physiological confounders (e.g., blood volume pulsation, temperature-induced perfusion changes, tissue scattering) and photon shot noise from the light source. Therefore, while our system’s electronic sensitivity is robust, its practical accuracy is fundamentally limited by the efficacy of the signal processing algorithms in isolating the true glucose signature from these dominant non-glycemic noise sources.

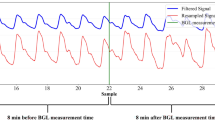

System stability and drift analysis

A long-term uniformity test was conducted to evaluate the operational stability of the device against thermal and power supply-induced drift. The fully charged device was affixed to a solid tissue-equivalent phantom. The assembly was placed in a light-isolated, temperature-controlled environment. The evaluation test consisted of two modes: intermittent and continuous. The intermittent mode conducted with the system was powered on every 30-second sampling intervals. The continuous mode conducted with the system was powered on continuously. Both tests ran uninterrupted until the battery was depletion. The phantom was fabricated from Acrylic epoxy resin (3:1) co-polymerized with SMOFlipid 20% (FRESENIUS Kabi, Lot 16TL2448) to mimic the bulk optical properties of a human tissue (absorption coefficient \(\mu _a = 0.308 \text { cm}^{-1}\), and reduced scattering coefficient \(\mu _s' = 51.45 \text { cm}^{-1}\)), as shown in Fig 13(a). Figure 13(b) shows the comparison of two operational modes: intermittent (black circles) and continuous (red circles). The continuous mode clearly exhibits a \(\approx\)23-minute thermal stabilization period (initial high-variance phase) not present in the intermittent mode. Both traces subsequently show a correlated monotonic signal decay, demonstrating power-supply-induced drift as the battery voltage decreases.

System stability and drift analysis using a tissue-simulating phantom: (a) The non-invasive monitoring device (top and bottom panels) and the solid optical phantom (middle panel), and (b) Time-series analysis of the transmission (MT) signal output, recorded from a 100% battery charge until depletion.

The stability test data (Fig. 13(b)) shows two critical sources of signal drift. The continuous mode exhibited a significant thermal stabilization period, maintaining a stable output (mean \(1.6911 \pm 0.0004 \text { V}\)) for the initial 23 minutes before a monotonic downward drift began. Both modes demonstrated a slow, continuous signal decay correlated with battery discharge. In intermittent mode, the signal drifted by −0.24% (from 1.6424 V to 1.6385 V) over its 64.5-minute operational life. After its thermal stabilization, the continuous mode exhibited a similar power-related drift of −0.21% (from 1.6896 V to 1.6860 V) over the subsequent 47.5 minutes.

Phase I: Establishing the relationship between signal and blood glucose concentration

In this phase, data were collected from Ho Chi Minh University of Technology volunteers to establish a correlation between the measured signal and blood glucose concentration. Before participation, all volunteers were thoroughly briefed on the study objectives and procedures and provided written informed consent. The dataset comprised 10 voltage signals per individual, obtained using a custom non-invasive device, along with a single blood glucose value measured with a commercial VivaChek Ino device (VivaChek BioTech (Hangzhou) Co., Ltd., Model VGM01, SN 311Z0021494) with test strips (VivaChek BioTech (Hangzhou) Co., Ltd., Model VGS01, LOT 245994). A total of 500 samples were collected from 50 volunteers, including 26 men and 24 women aged between 18 and 45 years (mean ± standard deviation age of 26.4 ± 7.6 years, thickness of fingertip of 10.2 ± 1.10 mm). The recorded blood glucose levels ranged from 75 to 174 mg/dL. The room temperature in the measurement area was maintained at 25\(^\circ\)C to ensure consistent optical measurements.

To ensure hygiene and measurement consistency, each volunteer’s fingers were disinfected with alcohol before the data collection. A fresh set of needles and test strips was used for each sample. The participant’s finger was pricked, and a drop of blood was placed on the test strip of the invasive blood glucose measurement device. Immediately after recording the values, the site was disinfected, and hemostatic measures were applied. The volunteers were then instructed to insert each of their 10 fingers into the non-invasive device one at a time. Data acquisition commenced 2.0 seconds after finger insertion into the proposed system, during which 100 data points were recorded per measurement. Specifically, each measurement required approximately 0.2 seconds to collect 100 samples at 2 ms intervals, corresponding to a sampling frequency of 500 Hz. The averaged result was then used to determine the final voltage value.

To validate the prediction model, the relationship between the reference blood glucose values and the proposed system was analyzed using the least-squares method, as illustrated in Fig. 14. The X-axis represents the blood glucose values measured by the VivaChek Ino device, while the Y-axis represents the voltage signal from the non-invasive device. The red line indicates the predicted values obtained using the regression model. Initial findings from the six measurement strategies revealed distinct trends: reflection-based measurement strategies exhibited an increase in voltage with increasing blood glucose levels, whereas transmission-based measurement strategies showed a decrease in voltage with increasing blood glucose concentrations.

Correlation between blood glucose concentration and signal voltage from the proposed system. The red regression line demonstrates the relationship between invasive glucose reference values and non-invasive voltage signals: (a) from SR1, (b) from SR2, (c) from MR, (d) from ST1, (e) from ST2, and (f) from MT.

The performance results, summarized in Table 1, reveal two key observations in Phase I. The reflection-based strategies SR1 (reflection at 660 nm), SR2 (reflection at 940 nm), and MR (reflection using combined wavelengths of 660 nm and 940 nm) exhibited lower prediction accuracy, with coefficient of determination (\(R^2\)) values of 0.5261, 0.6417, and 0.7072, respectively. In contrast, the transmission-based strategies ST1 (transmission at 660 nm), ST2 (transmission at 940 nm), and MT (transmission using combined wavelengths of 660 nm and 940 nm) demonstrated higher efficiencies, with \(R^2\) values of 0.7204, 0.8269, and 0.8832, respectively. Furthermore, strategies using combined light sources outperformed the single-wavelength strategies in terms of efficiency.

Phase II: Validate the feasibility of the blood glucose monitoring device

During the validation phase of the proposed non-invasive blood glucose sensing method, experiments were conducted on a cohort of 96 volunteers, including 46 men and 50 women aged between 18 and 50 years (mean ± standard deviation age of 25.1 ± 8.3 years, thickness of fingertip of 10.05 ± 1.02 mm), with no history of blood sugar-related diseases. The study was randomized, and the values were mostly distributed within the normal glucose range. Before participation, all volunteers received comprehensive information regarding the study’s objectives, experimental procedures, and safety measures, including adherence to Class I laser safety standards for the light source. To ensure accuracy, blood glucose measurements were obtained simultaneously using the proposed system and a commercially available VivaChek Ino device. The proposed method incorporated six distinct measurement strategies to assess performance and reliability under various conditions, as outlined in Table 1.

To maintain hygiene and measurement integrity, each volunteer’s fingers were disinfected with alcohol before collecting the data. A fresh set of needles and test strips was used for each sample. The participant’s finger was pricked, and a drop of blood was placed on the test strip of the invasive device. Upon recording the blood glucose value, the test site was disinfected, and hemostatic measures were applied. Volunteers were then instructed to insert one finger at a time into the non-invasive device, where measurements commenced 2.0 seconds after insertion. The room temperature in the measurement area was maintained at 25\(^\circ\)C to ensure consistent optical measurements. For each measurement, a total of 100 data points were recorded to determine the blood glucose value. The recorded blood glucose levels ranged from 79 to 149 mg/dL, as illustrated in Fig. 15(a).

The performances of the six proposed strategies (SR1, SR2, MR, ST1, ST2, and MT) were compared with that of the VivaChek Ino device with mean glucose concentrations of 110.760 mg/dL (s.d. = 15.767 mg/dL) in Table 2, which was used as a reference for blood glucose measurement. A box-plot analysis, as shown in Fig. 15(b) shows the distribution, median, and variability of the glucose values obtained using each method. Among the proposed measurement strategies, MT and ST2 showed the narrowest IQR and the closest median glucose values to VivaChek Ino, indicating a higher accuracy than the reference. Strategies SR1, SR2, and MR showed wider distributions, with some outliers and larger deviations from the VivaChek Ino median, indicating a reduced accuracy. SR1 and SR2 showed peak glucose values, indicating higher sensitivity to noise or variations in the experimental conditions.

The sample size was determined by practical feasibility and post-hoc power analysis, consistent with trials of non-invasive glucose monitoring. Phase I used 500 samples from 50 volunteers (10 per individual) to establish signal-glucose relationships, aligning with prior NIR studies5. Phase II recruited 96 volunteers (aged 18–50) for clinical validation. The minimum sample size was calculated as (16)29

where \(n\) is the sample size; \(Z_{1 - \frac{\alpha }{2}}\) is the critical value from the standard normal distribution corresponding to the significance level \(\alpha\), which reflects the desired confidence level; \(\sigma\) is standard deviation; and \(d\) is margin of error or precision. In this study, a confidence level of 95 % was selected, corresponding to \(Z\) = 1.96. The standard deviation \(\sigma\) of blood sugar was assumed to be 6.5 mg/dL, and \(d\) was set at 2 mg/dL. Applying the sample size calculation (15), the minimum sample size was determined to be 41 samples.

Quantitative evaluations using the MAE, mARD, and RMSE metrics are presented in Table 2. Paired t-tests (two-tailed, alpha = 0.01) were conducted to compare glucose values from each strategy against VivaChek Ino reference values (n = 96). The normality of the differences was confirmed using the Shapiro-Wilk test (p > 0.05 for all strategies), justifying the use of paired t-tests.

Among the proposed measurement strategies, MT and ST2 achieved the lowest MAE (8.438 and 8.542, respectively), indicating the smallest absolute error compared to the reference. These measurement strategies also demonstrated the lowest mARD (8.004 and 8.030, respectively) and RMSE (9.601 and 9.622, respectively), indicating a good agreement and reduced variability in glucose measurements. For the MT strategy, the mean difference from VivaChek Ino was 2.750 mg/dL (s.d.of the differences = 9.247 mg/dL, p = 0.005), indicating a statistically significant difference (p < 0.01). SR1, SR2, and MR showed higher MAE (20.521, 19.573, and 15.354, respectively) and RMSE (24.768, 24.337, and 18.593, respectively) values, indicating a greater absolute deviation from the reference. These measurement strategies also showed higher mARD values exceeding 0.10 and a wider distribution with more outliers, reducing the precision and reliability of the measurements. These strategies also showed wider distributions (s.d. = 24.509 mg/dL, 27.235 mg/dL, and 21.886 mg/dL, respectively, compared to 15.824 mg/dL for ST2 and 15.898 mg/dL for MT), suggesting reduced precision and reliability.

The Bland-Altman limits of the agreement plots showing these correlations are shown in Fig. 16. The SR1, SR2, and MR measurement strategies can perform relatively wide limits of agreement (LoAs), as shown in Figs. 16(a), (b), and (c), showing a higher variability and reduced agreement with VivaChek Ino. These measurement strategies show differences in that the mean (bias) is close to zero, indicating no systematic bias; however, a large LoA reflects minimal non-minimal light reflection in the precision of the exact measurement. Value outliers may indicate errors in the measurement strategies. The ST1, ST2, and MT measurement strategies are shown in Figs. 16(d), (e), and (f), which show narrower LoAs, indicating improved precision and better agreement compared to those of VivaChek Ino. The mean differences between these measurement strategies (−1.854, −2.104, and −2.750, respectively) were small, confirming their minimal nature in glucose measurements. MT is a suitable non-invasive glucose measurement method because of the reduced variability and fewer outliers observed in these measurement strategies, making it more suitable for various applications.

Bland-Altman plot showing the difference between the glucose concentration of the VivaChek Ino device and the glucose concentration measured with the proposed system. For the graph, the black line represents the mean difference of 0 between the compared glucose concentrations, the blue line represents the actual mean difference between the glucose concentrations from the measurement strategies, and the dashed line represents the 95 % limits of agreement with mean difference ± 1.96 SD. The closer the blue line is to the black line, the higher the agreement between the two measurement strategies: (a–c) reflection measurement strategies (SR1, SR2, MR) showing wider limits of agreement and (d–f) transmission measurement strategies (ST1, ST2, MT) demonstrating narrower limits of agreement and minimal bias.

The Clarke Error Grid analysis is shown in Fig. 17 was used to assess the accuracy. This analysis classified measurements into clinically relevant Zones (A–E), with Zones A and B representing clinically acceptable measurements and Zones C, D, and E indicating potentially harmful errors. In all measurement strategies, most data points fell within Zone A, indicating high accuracy and clinical acceptability compared with the VivaChek Ino. Measurement strategies: SR1, SR2, and MR showed a larger proportion of points in Zone B and no individual points in Zones C and D, indicating reduced accuracy and the possibility of clinically substantial errors in some cases. Of these, MR showed a slightly better accuracy than SR1 and SR2. The ST1, ST2, and MT measurement strategies exhibited good performance, with more than 90 % of the data points falling in Zone A and the remaining points falling in Zone B.

The distribution of the measurement samples was widespread across the relevant Zones (A, B, and C), as shown in Fig. 18. Most samples from measurement strategies ST1, ST2, and MT were concentrated in Zone A, with more than 90 % of the measurements falling within the analyzed accuracy range. These measurement strategies also showed that the samples fell within the 10 % and 5 % error thresholds in Zone A (Fig. 18), indicating high precision and close agreement with the VivaChek Ino device. Furthermore, these measurement strategies showed a minimal distribution in Zone B and could exclude up to no samples in Zone C. The measurement strategies SR1, SR2, and MR exhibited lower performance, with approximately 60–70 % of the samples falling within Zone A and a large proportion falling within Zone B. The inset further illustrates that fewer samples from these measurement strategies fall within the 5 % and 10 % error thresholds, indicating reduced accuracy and reliability. MT provides the most reliable and clinically acceptable results. This method shows potential for practical application in non-invasive glucose monitoring, whereas ST1, ST2, and MR require further optimization to minimize errors and improve reliability.

Figure 19 shows the system accuracy plots, which show the difference between measured and reference glucose values (y-axis, in mg/dL) against the reference glucose concentration (x-axis, in mg/dL). Dashed lines indicate the ISO 15197:2013/EN ISO 15197:2015 accuracy boundaries: for glucose levels <100 mg/dL, the acceptable difference is ± 15 mg/dL, and for levels \(\ge\)100 mg/dL, the acceptable difference is ± 15 %30,31. The data points within these boundaries indicate compliance with the relevant standards. The plots show a general clustering of points around the zero-difference line with varying degrees of spread. Measurement strategies ST1, ST2, and MT exhibited fewer outliers beyond the accuracy boundaries than SR1, SR2, and MR, suggesting better performance. MT had the best consensus among the tested measurement strategies.

For glucose concentrations < 100 mg/dL, the ISO 15197:2013/EN ISO 15197:2015 standard requires that \(\ge\)95 % of measurements fall within ± 15 mg/dL of the reference value, as shown in Table 3. The results show that measurement strategies ST2, and MT achieved 100 % compliance (19/19 measurements within ± 15 mg/dL), while ST1, MR, SR2, and SR1 were low, with 94.7 % (18/19), 63.2 % (12/19), 47.4 % (9/19), and 21.1 % (4/19) of measurements meeting the criterion, respectively. At tighter thresholds (± 5 mg/dL), MT and ST1 had the lowest accuracy at 5.3 % (1/19), whereas ST2 and SR2 performed better at 21.1 % (4/19).

For glucose concentrations \(\ge\) 100 mg/dL, the ISO 15197:2013/EN ISO 15197:2015 standard requires that \(\ge\) 95 % of measurements fall within ± 15 % of the reference value, as shown in Table 4. Measurement strategies ST1, ST2, and MT excelled, with 94.8 % (73/77), 96.1 % (74/77), and 98.7 % (76/77) of measurements within ± 15 %, respectively, with ST1 and ST2 achieving 100 % compliance at ± 20 %. In contrast, MR, SR1, and SR2 showed lower compliance at 61.0 % (47/77), 49.4 % (38/77), and 50.6 % (39/77) within ± 15 %, respectively. At the ± 5 % threshold, MT again outperformed others at 44.2 % (34/77), while SR1 and SR2 lagged at 19.5 % (15/77).

The analysis showed variability in the accuracy of the proposed system. Measurement strategies ST1, ST2, and MT met or closely approached the ISO 15197:2013/EN ISO 15197:2015 requirement, showing good performance across the tested concentrations. These measurement strategies showed tighter clustering in the system accuracy plots with fewer outliers, indicating greater reliability for clinical use. Conversely, measurement strategies SR1, SR2, and MR failed to meet the ISO standard, as a substantial proportion of measurements fell outside the acceptable limits for glucose levels <100 mg/dL.

Phase III: Gold standard clinical validation protocol

To benchmark the device’s analytical accuracy against the definitive clinical reference, we conducted an intensive validation protocol at two sites University Medical Center Ho Chi Minh City and Military Hospital 175. We recruited three (N=3) volunteers (1 female, aged 24 years; 2 males, aged 40–41 years) of our research group. This small, intensively-monitored cohort was intentionally selected to ensure strict adherence to a standardized dietary regimen, facilitating the controlled induction and tracking of post-prandial glycemic excursions. The HbA1c Premier HB9210 analyzer measured glycated hemoglobin at both centers, while plasma glucose quantification used the DxC 700 AU system at the University Medical Center Ho Chi Minh City and the AU 5822 system at Military Hospital 175. Baseline HbA1c measurements confirmed that all participants were non-diabetic (range 5.0% – 5.9%), thereby minimizing the potential confounding effects of underlying metabolic disorders.

The protocol involved five dynamic sampling points throughout the day, aligned with metabolic state changes: 07:00 (fasting), 08:00 (post-prandial), 11:00 (pre-prandial), 12:00 (post-prandial), and 16:00. At each time point, a precise tri-way measurement was performed simultaneously: (i) venous blood was drawn for gold-standard laboratory analysis (Venous Plasma Glucose, VPG), (ii) capillary blood was measured using an ISO 15197:2015-compliant device (VivaChek), and (iii) noninvasive optical data were acquired using the proposed device on 10 fingertips (N = 150, corresponding to 3 volunteers, 10 fingers and measured at 5 different times). This experimental design enabled a direct comparison of our non-invasive method and the commercial capillary meter against the definitive gold-standard reference.

The Phase III validation provided a rigorous, comparison of our six proposed strategies and a commercial, ISO-compliant meter (VivaChek) against the definitive VPG gold standard. The results, summarized in Fig. 20, Fig. 21 and Fig. 22 delineate a clear performance hierarchy, establish the clinical non-viability of reflection-based sensing, and confirm the superior accuracy of MT approach. Each figure represents an individual volunteer. Within each panel, data is evaluated using two standard clinical accuracy metrics: the CEG, which assesses clinical safety, and the ISO 15197:2015 System Accuracy plot, which plots the analytical error against the VPG reference within the ±15%/±15 mg/dL acceptance boundaries.

Figure 20 compares the proposed measurement strategies with the VivaChek device against the VPG gold standard in a healthy 40-year-old male volunteer (HbA1c = 5.6%) at the University Medical Center Ho Chi Minh City. VivaChek (Fig. 20a) shows all data points in the Clarke Zone A and achieves 100% compliance with the ISO 15197:2015 accuracy requirement of ±15%/±15 mg/dL, confirming clinical reliability. The reflective strategies (Fig. 20b) record a larger number of points in Zone B than Zone A, with 38–42% of points meeting the ISO 15197:2015 criteria, demonstrating limited analytical accuracy despite achieving acceptable clinical classification. The transmission strategies (Fig 20c) recorded more points in Zone A than Zone B and achieved 78–90% compliance with ISO 15197:2015 criteria. Among the strategies, MT provided the highest analytical accuracy of the evaluated methods (up to 90%).

Figure 21 compares the proposed measurement strategies with the VivaChek device against the VPG gold standard in a healthy 24-year-old female volunteer (HbA1c = 5.0%) at the University Medical Center Ho Chi Minh City. VivaChek (Fig. 21a) shows all data points in the Clarke Zone A and achieves 100% compliance with the ISO 15197:2015 accuracy requirement of ±15%/±15 mg/dL, confirming clinical reliability. The reflective strategies (Fig. 21b) record a larger number of points in Zone B than Zone A, with 26–38% of points meeting the ISO 15197:2015 criteria, demonstrating limited analytical accuracy despite achieving acceptable clinical classification. The transmission strategies (Fig 21c) recorded more points in Zone A than Zone B and achieved 84–96% compliance with ISO 15197:2015 criteria. Among the strategies, MT provided the highest analytical accuracy of the evaluated methods (up to 96%).

Figure 22 compares the proposed measurement strategies with the VivaChek device against the VPG gold standard in a healthy 41-year-old male volunteer (HbA1c = 5.22 %) at Military Hospital 175. VivaChek (Fig. 22a) shows all data points in Clarke Zone A and achieves 100 % compliance with the ISO 15197:2015 accuracy requirement of ±15 %/±15 mg/dL, confirming clinical reliability. The reflective strategies (Fig. 22b) record more points in Zone B than Zone A, with 28–34 % of points meeting the ISO 15197:2015 criteria. A small number of points fall in Zone D shows limited analytical accuracy and potential clinical risk despite an overall acceptable clinical classification. The transmission strategies (Fig. 22c) show more points in Zone A than Zone B and achieve 80–90 % compliance with ISO 15197:2015 criteria, with no points observed in Zone D. Among the strategies, MT provides th e highest analytical accuracy of the evaluated methods (up to 90 %).

The benchmark device (VivaChek), while placing 100% of its measurements (N=15, 3 volunteers, 10 fingers, and measured at one time) within the clinically acceptable CEG Zones A and B, with all data points meeting the ±15%/±15 mg/dL standard of the ISO 15197:2015 criteria (Fig. 20a, Fig. 21a, and Fig. 22a). The reflection-based strategies (SR1, SR2, and MR) failed. As shown in Fig. 20b, Fig. 21b, and Fig. 22b, these methods produced numerous measurements in Zone D. This constitutes a clinically dangerous failure, incorrectly reporting hypoglycemia as normoglycemia and vice-versa, confirming their unsuitability for clinical use. In contrast, all three transmission-based strategies (Fig. 20c, Fig. 21c, and Fig. 22c) demonstrated clinical safety, placing 100% of all measurements exclusively within Zones A and B. Notably, the MT strategy achieved the highest possible safety rating, with 100% of all data points falling within Zone A and demonstrated superior analytical precision (tighter ISO 15197:2015 compliance) than the commercial VivaChek benchmark. The ISO 15197:2015 analysis reveals that the MT strategy’s analytical precision met and agreement the commercial benchmark. The MT data points exhibit a tighter cluster around the zero-error line compared to the more broadly scattered VivaChek measurements. Visually, the MT strategy produced fewer excursions beyond the ±15%/±15 mg/dL acceptance boundaries, demonstrating superior analytical agreement with the VPG gold standard.

Discussion

This study presents a multi-stage validation culminating in a critical comparison against the VPG gold standard. While preliminary phases benchmarked against a commercial capillary meter showed promise, the definitive findings emerge from Phase III (Fig. 20, Fig. 21, Fig. 22). This analysis unequivocally established a performance hierarchy among our proposed strategies. All reflection-based modalities (SR1, SR2, MR) failed, producing clinically dangerous Zone D errors on the CEG, rendering them unsuitable for clinical application due to likely superficial signal contamination and insufficient tissue penetration.

In contrast, all transmission strategies (ST1, ST2, MT) demonstrated perfect clinical safety (100% Zones A/B). Crucially, our MT strategy achieved 100% Zone A accuracy and, when benchmarked against VPG, exhibited superior analytical precision (tighter ISO 15197:2015 compliance) compared to the established, ISO-compliant commercial meter (VivaChek). This superior performance strongly suggests that the 660 nm channel, despite lower glucose specificity, provides an essential ratiometric correction, likely mitigating dynamic non-glycemic confounders such as fluctuations in tissue perfusion, blood volume, or scattering that would otherwise corrupt the primary 940 nm glucose signal.

However, realizing robust non-invasive optical sensing faces fundamental hardware challenges, which we characterized directly. NEP analysis confirmed high electronic sensitivity (626 pW/\(\sqrt{Hz}\) at 940 nm), indicating the system’s electronic noise floor is not the bottleneck. The core limitation lies in the extremely low physiological SNR, where the minuscule glucose-induced optical modulation is buried within a massive background of physiological and photon shot noise. Furthermore, long-term uniformity testing on a tissue phantom (Fig. 13) revealed critical stability issues: a significant (\(\approx\)23-minute) thermal warm-up requirement for continuous operation and, more importantly, a power-supply-induced signal drift (\(\approx\)0.21–0.24.21.24%) correlated with battery depletion. This drift artifact, being on the same order of magnitude as the expected glucose signal, represents a major confounder that mandates the incorporation of precision ratiometric referencing or high-grade power regulation in future iterations.

Beyond hardware, clinical limitations persist. The pivotal Phase III validation, although intensive, relied on only three volunteers. Our broader Phase II study (N=96), although demonstrating general feasibility, was limited to a healthy cohort within a narrow normoglycemic range (79–149 mg/dL). Consequently, the device’s performance across the full clinical spectrum in hypoglycemic (<70 mg/dL) and hyperglycemic (>180 mg/dL) states critical for diabetes management–requires rigorous evaluation in large, scale trials involving diverse diabetic populations (Type 1 and Type 2).

The modularity of this open-source platform invites future extensions, such as non-invasive HbA1c monitoring. As discussed, this would necessitate a hardware shift to the Short-Wave Infrared (SWIR) range (1500–1800 nm) and the use of an InGaAs detector, targeting subtle glycation-induced spectral changes32,33. While technically feasible, this adaptation faces even greater challenges in terms of physiological SNR and requires overcoming the profound logistical hurdles of calibration against a static, three-month average.

In conclusion, by validating against the gold standard and transparently characterizing hardware limitations, we establish an open-source, multi-wavelength transmission system that demonstrably outperforms a commercial invasive benchmark in analytical accuracy. This work provides a critical, verifiable foundation and a clear technological pathway toward clinically reliable, non-invasive glucose monitoring that is accessible.

Conclusion

We have developed and validated an open-source, multi-wavelength (660/940 nm) spectroscopic system, establishing a new benchmark for non-invasive glucose monitoring. While the majority of prior studies have relied on benchmarking against error-prone capillary meters, we presented a definitive, clinical validation (Phase III) comparing our device and an ISO-compliant commercial meter against the VPG gold standard.

This analysis established a clear and unequivocal performance hierarchy. All reflection-based strategies failed, producing clinically dangerous (Zone D, Clarke Error Grid) measurements. In stark contrast, our multi-wavelength transmission (MT) strategy achieved clinical safety (100% Zone A). Critically, the MT strategy also demonstrated superior analytical precision and tighter compliance with ISO 15197:2013 than the established, invasive commercial benchmark when both were directly compared to the VPG reference.

By providing a hardware characterization (NEP, drift analysis) and distinguishing our static absorption approach from dynamic PPG-based systems, we deliver a transparent, accessible, and gold-standard-validated platform. This work successfully demonstrates that a non-invasive optical method can, in fact, achieve analytical accuracy superior to current invasive standards, providing a robust open-source foundation for the next generation of diabetes technology.

Data availability

Data on the schematic, case design, and algorithm are available at GITHUB: https://github.com/HoangNhutHuynh/Blood_glucose

References

Bode, B. et al. Alarms based on real-time sensor glucose values alert patients to hypo-and hyperglycemia: the guardian continuous monitoring system. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 6, 105–113 (2004).

Christiansen, M. P. et al. A prospective multicenter evaluation of the accuracy of a novel implanted continuous glucose sensor: PRECISE II. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 20, 197–206 (2018).

Hathout, E. et al. Home use of the GlucoWatch G2 biographer in children with diabetes. Pediatrics 115, 662–666 (2005).

K. M., A. et al. Internet of Things enabled open source assisted real-time blood glucose monitoring framework. Sci. Rep. 14, 6151 (2024).

Rajeswari, S. V. K. R. & Vijayakumar, P. Development of sensor system and data analytic framework for non-invasive blood glucose prediction. Sci. Rep. 14, 9206 (2024).

Anas, M. N., Nurun, N. K., Norali, A. N., Normahira, M. Non-invasive blood glucose measurement. In: 2012 IEEE-EMBS Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Sciences, 503–507 (2012).

Tang, L., Chang, S. J., Chen, C.-J. & Liu, J.-T. Non-invasive blood glucose monitoring technology: a review. Sensors 20, 6925 (2020).

Amaral, C. F., Brischwein, M. & Wolf, B. Multiparameter techniques for non-invasive measurement of blood glucose. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 140, 12–16 (2009).

Sharma, S., Huang, Z., Rogers, M., Boutelle, M. & Cass, A. E. G. Evaluation of a minimally invasive glucose biosensor for continuous tissue monitoring. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 408, 8427–8435 (2016).

Soltanian, F. et al. On-body non-invasive glucose monitoring sensor based on high figure of merit (FoM) surface plasmonic microwave resonator. Sci. Rep. 13, 17527 (2023).

Uluç, N. et al. Non-invasive measurements of blood glucose levels by time-gating mid-infrared optoacoustic signals. Nat. Metab. 6, 678–686 (2024).

Clemens, N. The European medical device regulation 2017/745/EU: changes and impact on stakeholders. J. Clin. Res. Best Pract. 14, 1–7 (2018).

Lubinski, T., Plotka, B., Janik, S., Canini, L. & Mantele, W. Evaluation of a novel noninvasive blood glucose monitor based on mid-infrared quantum cascade laser technology and photothermal detection. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 15, 6–10 (2021).

Darwich, M. A. et al. Non-invasive IR-based measurement of human blood glucose. Eng. Proc. 35, 27 (2023).

Satter, S., Turja, M. S., Kwon, T.-H. & Kim, K.-D. EMD-based noninvasive blood glucose estimation from PPG signals using machine learning algorithms. Appl. Sci. 14, 1406. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14041406 (2024).

Hossain, S., Haque, C. A. & Kim, K.-D. Quantitative analysis of different multi-wavelength PPG devices and methods for noninvasive in vivo estimation of glycated hemoglobin. Appl. Sci. 11, 6867. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11156867 (2021).

Satter, S., Kwon, T.-H. & Kim, K.-D. A comparative analysis of various machine learning algorithms to improve the accuracy of HbA1c estimation using wrist PPG data. Sensors 23, 7231. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23167231 (2023).

Kwon, T.-H., Hossain, S., Turja, M. S. & Kim, K.-D. Design and validation of a Monte Carlo method for the implementation of noninvasive wearable devices for HbA1c estimation considering the skin effect. Micromachines 15, 1067. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi15091067 (2024).

Nguyen, A. T. P. et al. Investigation Transillumination Mode at 660 and 780 nm for Non-Invasive Blood Glucose Monitoring Device. In: 2023 IEEE 5th Eurasia Conference on Biomedical Engineering, Healthcare and Sustainability (ECBIOS), 50–53 (IEEE, 2023).

Tran, T. T., Thi, M. N. N., Truong, V. P., Truong, M. N. & Tran, T. N. Investigation of the Glucose Molar Absorptivity Concerning Sugar Concentration from Visible to Mid-Infrared (450–1550 nm). In: International Conference on the Development of Biomedical Engineering in Vietnam, 676–688 (Springer, 2022).

Yadav, J., Rani, A., Singh, V. & Murari, B. M. Prospects and limitations of non-invasive blood glucose monitoring using near-infrared spectroscopy. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 18, 214–227 (2015).

Jain, P., Maddila, R. & Joshi, A. M. A precise non-invasive blood glucose measurement system using NIR spectroscopy and Huber’s regression model. Opt. Quantum Electron. 51, 51 (2019).

Avci, P. et al. Low-level laser (light) therapy (LLLT) in skin: stimulating, healing, restoring. In: Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery, vol. 32, 41 (NIH Public Access, 2013).

Santos, F. P., Carvalhos, C. A. & Figueiredo-Dias, M. New Insights into Photobiomodulation of the Vaginal Microbiome-A Critical Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 13507 (2023).

Tereshchenko, O. E. et al. Solar energy converters based on multi-junction photoemission solar cells. Sci. Rep. 7, 16154 (2017).

Biesiadzinski, T., Lorenzon, W., Schubnell, M., Tarlé, G. & Weaverdyck, C. NIR detector nonlinearity and quantum efficiency. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 126, 243–249 (2014).

Hicks, C., Kalatsky, M., Metzler, R. A. & Goushcha, A. O. Quantum efficiency of silicon photodiodes in the near-infrared spectral range. Appl. Opt. 42, 4415–4422 (2003).

The new edition of the international laser product safety standard IEC 60825-1. Laser 43, 2882 (2017).

Sadiq, I. Z., Usman, A., Muhammad, A. & Ahmad, K. H. Sample size calculation in biomedical, clinical and biological sciences research. J. Umm Al-Qura Univ. Appl. Sci. 1–9 (2024).

Jendrike, N., Baumstark, A., Kamecke, U., Haug, C. & Freckmann, G. ISO 15197:2013 evaluation of a blood glucose monitoring system’s measurement accuracy. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 11, 1275–1276 (2017).

Breitenbeck, N. & Brown, A. Accuracy assessment of a blood glucose monitoring system for self-testing with three test strip lots following ISO 15197:2013/EN ISO 15197:2015. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 11, 854–855 (2017).

Jain, G., Joshi, A. M. & Kumar, M. R. Non-invasive measurement of HbA1c using spectroscopic method. In Data Science and Applications (ICDSA 2024), edited by Nanda, S. J., Yadav, R. P., Gandomi, A. H. & Saraswat, M., Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol. 1237, (Springer, Singapore, 2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-96-1185-0_21.

Mallya, M. et al. Absorption spectroscopy for the estimation of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) for the diagnosis and management of diabetes mellitus: a pilot study. Photomed. Laser Surg. 31, 219–224. https://doi.org/10.1089/pho.2012.3421 (2013).

Funding

This work was supported by Vietnam National University Ho Chi Minh City (VNU-HCM) under Grant VL2024-20-01 (old number B2024-20-17). We acknowledge Ho Chi Minh City University of Technology (HCMUT), VNU-HCM for supporting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.D.T. Tran and T.N. Tran contributed to conceptualization and methodology. A.T.P. Nguyen, T.V. Huynh, T.H. Tran, N.A.D. Nguyen, M.H. Phan, H.V. Nguyen Thi, A.T.L. Le, T.T. Nguyen, and D.V. Thanh participated in data curation, hardware design, and sample collection, with M.H. Phan, H.V. Nguyen Thi, A.T.L. Le, T.T. Nguyen, and D.V. Thanh specifically overseeing sample collection from volunteers. H.N. Huynh, T.V. Huynh, and T.H. Tran were responsible for writing the original draft and handling review and editing. T.N. Tran and H.D.T. Tran provided the supervision and resources. H.N. Huynh and A.T.P. Nguyen conducted algorithm development, formal analysis, and validation. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The safeguards and protocols of this study were approved by the ethics committee of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City No: IRB-VN01002/IRB00010293/FWA00023448.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nguyen, A.T.P., Huynh, T.V., Huynh, H.N. et al. The open-source multi-wavelength non-invasive blood glucose sensing system. Sci Rep 15, 45731 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28673-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28673-4