Abstract

This study aimed to evaluate the effects of orbitotomy on tuberculum sellae meningioma surgery using the supraorbital approach through a quantitative assessment of brain retraction and stratified effect by tumor size. An in-silico study was conducted using three-dimensional (3D) head models generated from the imaging data of 35 patients (70 hemispheres) without brain deformation, created with a surgical simulation software (GRID, Kompath Inc., Tokyo, Japan). A skull base tumor model was created by inserting virtual hemispherical tumors of varying diameters (20, 30, 40, and 50 mm) into the tuberculum sellae within the 3D model. Supraorbital craniotomy was performed on the skull base tumor model, and the distance of frontal lobe retraction required to access the tumor apex was measured with and without orbitotomy. Imaging data from 35 patients (70 hemispheres) revealed that orbitotomy statistically reduced frontal lobe retraction by 0.8 mm for 20 mm tumors, 1.55 mm for 30 mm tumors, 2.8 mm for 40 mm tumors, and 3.31 mm for 50 mm tumors (p < 0.01 for all findings). A comparison of the effects of orbitotomy according to tumor size showed the highest impact on tumors larger than 40 mm. This study quantified changes in brain retraction associated with adding orbitotomy for tumors of various sizes. These findings provide specific estimates for each tumor size, serving as a guideline for determining the indications for orbitotomy and contributing to optimizing skull base surgical approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The supraorbital approach is a craniotomy technique widely used to treat various diseases, including anterior skull base meningiomas and anterior circulation aneurysms1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. Its usefulness and safety are widely known, and in recent years, it has often been used in endoscopic procedures where a good surgical field can be secured8. In addition, orbitotomy may be performed when a broader approach to the anterior cranial fossa is required. Similar to the orbitozygomatic approach, studies have reported that adding an orbitotomy facilitates a caudal-to-cranial view and the access to lesions extending to the cranial side9. It has also been reported that adding an orbitotomy to the supraorbital approach increases the surgical working space for accessing common aneurysm sites10. Many skull base approaches have been developed to maximize the operative field, while minimizing brain retraction when reaching deep skull base lesions11. However, there are no concrete metrics quantifying the extent to which brain retraction is reduced by adding orbitotomy, as its indications are typically based on the judgment of experienced surgeons. Demonstrating the specific changes in brain retraction distance due to orbitotomy can provide a standardized guideline for its use. Evaluating the intraoperative deformation of soft tissues, such as the brain and nerves, is challenging as these structures degenerate during the preservation of cadaveric specimens9. Furthermore, preparing cadaveric specimens with lesions, such as skull base tumors and aneurysms is also difficult. For these reasons, previous reports examining the effect of the skull base approach have evaluated the angle and area of the operative field based on relatively solid structures, such as the skull and arteries, which are less prone to intraoperative deviation9,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. Nevertheless, no studies have directly evaluated how adding a skull base approach alters brain retraction9. One of the main goals of using a skull base approach is to minimize brain retraction when reaching deep lesions. Therefore, a quantitative evaluation of how brain retraction is reduced when using a skull base approach, such as orbitotomy, is required. Furthermore, stratifying this approach by lesion characteristics, such as tumor size, based on this quantitative evaluation may prove useful.

In recent years, virtual reality technology has been increasingly used in neurosurgery for clinical practices such as patient education21, surgeon training22,23, and surgical planning24. In addition, anatomical studies using virtual reality technology are emerging as viable alternatives to traditional cadaveric studies9,12,13,14,15,16,17. It has been previously reported that a three-dimensional (3D) head model can be created using simulation software based on head image data, and that a virtual craniotomy can be performed using the software to study surgical anatomy, in a manner similar to a cadaveric study9,16,17,25. However, even in these in-silico studies, no reports have examined brain deformation; only anatomical studies based on solid structures, such as the skull, have been conducted9,12,13,14,15,16,17. This was because of the limitations of conventional simulation software in representing soft tissue (e.g., brain and nerves) deformation9. However, remarkable progress has been made in surgical simulation software in recent years, making it possible to represent brain deformation25. With the development of virtual reality technology, estimated intraoperative brain retraction distances, which were previously challenging to measure, can now be quantitatively evaluated. This progress represents a significant milestone in anatomical research within the field of neurosurgery.

In this study, the effectiveness of orbitotomy using the supraorbital approach for tuberculum sellae meningioma surgery was evaluated based on a quantitative assessment of the brain retraction distance. This in-silico study is expected to facilitate a quantitative evaluation of intraoperative brain retraction, which has been difficult to assess in conventional cadaveric studies, and to establish new criteria for the indication of the supraorbital approach with orbitotomy.

Materials and methods

Study design and image data acquisition

In this study, we created a three-dimensional (3D) head model, including the brain, using surgical simulation software based on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans obtained at our institution. Furthermore, virtual tumor data were incorporated into the head model to create a skull base tumor model for performing in-silico anatomical studies.

The imaging data of patients who underwent surgical treatment at our institution between April 2022 and August 2024 was used in this study. Preoperative images were used and excluded if either CT or MRI was not performed, if brain deformities due to diseases such as tumors or hydrocephalus were evident, or if the data belonged to patients with a history of head surgery. Patients were also excluded if whole-brain balanced steady-state free precession MRI images, essential for accurately depicting the brain in the simulation software, were unavailable.

Virtual reality technology

In this study, GRID (ver. 1.1.8) (Kompath Inc., Tokyo, Japan), a commercial software specializing in neurosurgical simulations, was used (https://www.kompath.com/GRID/)25. The software can fuse image data from different modalities, such as CT and MRI, taken on the same patient to create 3D images. In addition, the software allows advanced surgical simulations, such as craniotomy, and exposure of lesions by retraction of soft tissues, such as the brain and vessels25.

Thin-slice (0.3 mm), whole-head CT, and whole-brain balanced steady-state free precession images (slice thickness, 0.6 mm) were used to create a 3D model. First, the CT and MRI images were aligned using the software (Fig. 1a). The alignment of CT and MRI images was performed automatically by the simulation software. When misalignment occurred, the authors manually corrected it by specifying multiple reference points to enhance precision. Next, a 3D model of the skull was created from the CT images, and a 3D model of the brain and eyeball was created from the MRI images (Fig. 1b); these were then fused together. Furthermore, a 3D model of the frontal lobe was created separately, as this software requires a detailed setting of the area to be deformed when deforming soft tissues. All 3D models were created using the surface-rendering method. The simulation software employs machine learning-based auto-segmentation to create 3D images of specific structures, such as the frontal lobe. The authors reviewed the auto-segmentation results, and when the depiction was inadequate, they manually adjusted the rendering area to improve accuracy (Fig. 1c). Finally, a skull base tumor model was created by inserting hemispherical virtual tumor data into the tuberculum sellae in the 3D model of the skull and brain (Fig. 1d). The virtual tumors were set to four sizes: 20, 30, 40, and 50 mm in diameter. All images presented in this manuscript were created using GRID.

Process of creating a skull base tumor model using the surgical simulation software. First, images obtained from computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are aligned on the software. The MRI and CT images are overlaid and misalignment at any location inspected (a). Next, the auto segmentation function is used to create three-dimensional (3D) models of the skull, eyeballs, brain, and frontal lobe; the areas used to create the 3D models in the MRI and CT images are shown in green, and any discrepancy in threshold settings is manually corrected (b and c). Finally, a hemispherical virtual tumor model is inserted from the tuberculum sellae to the planum sphenoidale in a 3D model to create a skull base tumor model (d).

Craniotomy and measurement

Supraorbital craniotomy was performed on the skull base tumor model using the same simulation software. The craniotomy was 2 × 3 cm in size, with the medial margin as the supraorbital foramen or notch and the inferior margin as the orbital rim (Fig. 2a). After the craniotomy, the intracranial side of the bony cross-section was slightly shaved to ensure the flattening of both the anterior cranial fossa and inferior side of the craniotomy margin. Additionally, a 2-cm wide section of the supraorbital wall was removed from the orbital rim during the orbitotomy (Fig. 2b). After the craniotomy, the frontal lobe was retracted until the tumor apex was exposed, as viewed from the inferior margin (Fig. 2c). The visual axis was defined as the angle from the inferior margin of the craniotomy to the tumor apex and was kept consistent across all simulations, in order to evaluate the brain retraction distance required to visualize the tumor apex. At the point where the surface of the frontal lobe borders the outer edge of the tumor, along a line drawn from the center of the craniotomy to the center of the tumor, we compared the data before and after frontal lobe retraction and measured the distance of retraction required to expose the tumor apex (Fig. 2d). For each tumor size, such distance was compared when using the supraorbital approach alone and the supraorbital approach with orbitotomy. This measurement was performed bilaterally.

Craniotomy and measurement on a skull base tumor model. A 2 × 3 cm supraorbital craniotomy is performed on the skull base tumor model (a), and a 2-cm wide section of the supraorbital wall is additionally removed from the orbital rim to perform an orbitotomy (b). The frontal lobe is retracted until the tip of the tumor is visible from the lower edge of the craniotomy (c), and the retraction distance of the frontal lobe required for tumor exposure is measured by comparing the data before retraction (d).

Asterisk (c): the tip of the tumor.

Statistical analysis

For both the supraorbital approach and the supraorbital approach with orbitotomy, the distance of frontal lobe retraction for each tumor size was statistically compared using a one-way analysis of variance and Tukey’s post-hoc test, as these tests are suitable for comparing means across multiple groups with normally distributed data. In addition, for each tumor size, the difference in distance was compared using the paired t-test for normally distributed data and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for non-normally distributed data. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess data normality, which guided the choice of appropriate statistical tests. Furthermore, whether the effects of orbitotomy differed according to tumor size was examined using the Kruskal–Wallis and Mann–Whitney U tests (p-values were adjusted by applying the Bonferroni correction). EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), a graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, version 4.2.3), was employed for statistical analyses in this study26. The statistical analysis methods and results of this study were reviewed and validated by a biostatistics expert who was independent of the study team. All results were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Ethical consideration

The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Fukuoka University, Fukuoka, Japan (approval number: U24-06-015). This retrospective imaging-based simulation study utilized only existing patient data. Since no human-derived samples were used and there were no invasive procedures or interventions involving study participants, the Institutional Review Board of Fukuoka University waived the requirement for written informed consent. Instead, the opt-out method was employed to ensure that participants had the opportunity to decline participation. To uphold ethical standards, study-related information was publicly disclosed on the institution’s website, allowing potential participants to make an informed decision about their involvement. This process was designed to enhance transparency and protect participant autonomy. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments.

Results

Patient characteristics of skull base tumor model

Of the 1333 patients who underwent surgery during the study period, imaging data from 35 patients (21 women, 14 men; median age, 69 years; interquartile range, 54.5–72 years) met the inclusion criteria for this study (Fig. 3). The majority of the patients were excluded based on the predefined exclusion criteria, primarily the absence of whole-brain balanced steady-state free precession MRI images. This limitation was attributed to the absence of standardized criteria for MRI sequence selection during preoperative imaging evaluation. Seventy left and right hemispheres were studied using a skull base tumor model generated from patient images. Data were originally collected to image internal carotid artery occlusions in 12 patients, unruptured cerebral aneurysms in 10 patients (all small), hemifacial spasms in 5 patients, trigeminal neuralgia in 4 patients, dural arteriovenous fistulas in 3 patients, and Parkinson’s disease in 1 patient.

Distance of frontal lobe Retraction according to tumor size

In the supraorbital approach, the average distances of frontal lobe retraction required to expose the tumor apex were as follows: 10.59 mm (standard deviation [SD], 1.04 mm) for a tumor size of 20 mm, 14.53 mm (SD, 1.69 mm) for 30 mm, 15.66 mm (SD, 2.1 mm) for 40 mm, and 15.13 mm (SD, 2.17 mm) for 50 mm (Fig. 4a). The distance of frontal lobe retraction increased with an increasing tumor size, up to 40 mm, while no difference was observed between 30 and 50 mm or between 40 and 50 mm (20 vs. 30 mm, p < 0.01; 20 vs. 40 mm, p < 0.01; 20 vs. 50 mm, p < 0.01; 30 vs. 40 mm, p < 0.01; 30 vs. 50 mm, p = 0.20; 40 vs. 50 mm, p = 0.32) (Fig. 4a) (Table 1). In contrast, the average distances of frontal lobe retraction required to expose the tumor apex in the supraorbital approach with orbitotomy were as follows: 9.72 mm (SD, 1.19 mm) for a tumor size of 20 mm, 12.97 mm (SD, 1.79 mm) for tumors of 30 mm, 12.86 mm (SD, 2.1 mm) for tumors of 40 mm, and 11.82 mm (SD, 1.93 mm) for tumors of 50 mm (Fig. 4b). Significant differences in frontal lobe retraction distance were seen between all tumor sizes, apart from tumors of 30 vs. 40 mm (20 vs. 30 mm, p < 0.01; 20 vs. 40 mm, p < 0.01; 20 vs. 50 mm, p < 0.01; 30 vs. 40 mm, p = 0.98; 30 vs. 50 mm, p < 0.01; 40 vs. 50 mm, p < 0.01) (Fig. 4b) (Table 1).

Bar graphs showing the distance of frontal lobe retraction required to expose the tumor apex for each tumor diameter in the supraorbital approach (a) and the supraorbital approach with orbitotomy (b) In the supraorbital approach, the retraction distance increased proportionally with tumor size up to a diameter of 40 mm (a). Conversely, in the supraorbital approach with orbitotomy, the retraction distance increased proportionally with tumor diameter up to 30 mm. However, it did not increase further for larger tumors. Notably, the 50 mm tumors had lesser retraction distance compared with that for 30 mm and 40 mm tumors (b).

Asterisk: p < 0.01.

Effects of orbitotomy according to tumor size

Our results clarify that the supraorbital approach with orbitotomy reduced the distance of frontal lobe retraction required compared to the supraorbital approach alone. More specifically, when comparing the supraorbital approach alone and the addition of orbitotomy, a median difference in frontal lobe retraction of 0.8 mm was observed between the two for tumors of 20 mm (p < 0.01). A mean difference of 1.55 mm was observed for tumors of 30 mm (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.37–1.74 mm, p < 0.01), a mean difference of 2.8 mm for tumors of 40 mm (95% CI, 2.55–3.04 mm, p < 0.01), and a mean difference of 3.31 mm for tumors of 50 mm (95% CI, 2.99–3.63 mm, p < 0.01). As the difference between the supraorbital approach and the supraorbital approach with orbitotomy was non-normally distributed when the tumor size was 20 mm (tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test, p < 0.01), the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was performed. For all other tumor sizes, a paired t-test was conducted instead, as the differences were normally distributed (tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test, 30 mm: p = 0.17, 40 mm: p = 0.32, 50 mm: p = 0.38). The effect sizes for the comparison between the supraorbital approach alone and the additional orbitotomy group were large across all tumor sizes (20 mm: r = 0.87, 30 mm: d = 2.00, 40 mm: d = 2.74, 50 mm: d = 2.49). The effect size for the 20 mm group was calculated using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (r), while those for the other groups were calculated using Cohen’s d. As these metrics are derived from different statistical models, their numerical values are not directly comparable. Although 35 patients were included in the analysis, each hemisphere was evaluated separately, resulting in a total of 70 hemispheres. As the simulation assessed each side independently in terms of approach angle and frontal lobe retraction, each hemisphere was treated as an independent observation. The sample size was sufficient in all groups to achieve a statistical power of 80% with a significance level of less than 0.05.

Next, we examined whether the effects of orbitotomy varied with tumor size using the Kruskal–Wallis test and found significant differences (p < 0.01). While a pairwise comparison using the Mann–Whitney U test showed no difference between the 40 and 50 mm tumors (p = 0.18), for all other tumor sizes, the effects of orbitotomy increased as the tumor size increased (20 vs. 30 mm, p < 0.01; 20 vs. 40 mm, p < 0.01; 20 vs. 50 mm, p < 0.01; 30 vs. 40 mm, p < 0.01; 30 vs. 50 mm, p < 0.01) (p-values were adjusted by using the Bonferroni correction) (Fig. 5) (Table 1).

Box plot showing the change in the distance of frontal lobe retraction with the addition of orbitotomy according to each tumor size. The effect of orbitotomy on reducing retraction distance increased proportionally with tumor size up to a diameter of 40 mm. However, no significant difference was observed in the effect between tumor sizes of 40 mm and 50 mm.

Asterisk: p < 0.01.

The complete dataset used for the statistical analyses in this study has been provided as Supplementary Material.

Discussion

In this study, the effects of orbitotomy using the supraorbital approach were quantitatively evaluated based on the retraction distance of the frontal lobe. No studies have quantitatively evaluated the intraoperative brain retraction distance; furthermore, no reports have shown that its effect varies according to tumor size. Although a previous cadaveric study evaluated the effect of orbitotomy while taking frontal lobe retraction into account, it was limited to common aneurysm sites10, and its impact on skull base tumors has not been examined, likely reflecting the practical difficulty of obtaining cadaveric specimens harboring such tumors.

This study demonstrated that a novel anatomical research method using virtual reality technology enables a quantitative estimation of intraoperative brain deformities under simulated conditions, which was not previously feasible with cadaveric studies9. Since the primary objective of skull base approaches is to reduce brain retraction and expand the surgical field11, the findings of this study are expected to establish foundational criteria for new indications in skull base surgery.

Frontal lobe Retraction distance according to tumor size

Usually, the distance of brain retraction required to expose the tumor apex increases in proportion to the tumor size. However, in this study, the distance of frontal lobe retraction in the supraorbital approach was proportional to the tumor size up to 40 mm; no proportional relationship was observed at 50 mm (Fig. 4a). Moreover, when the tumor size was 20–30 mm, such distance was almost consistent with the height of the tumor at the midline (10 and 15 mm, respectively). In contrast, at 40 and 50 mm, the retraction distance was smaller than the height of the tumor at the midline (20 and 25 mm, respectively) (Fig. 4a). This occurs because, as the tumor grows, its apex shifts laterally from the midline when viewed from the inferior margin of the craniotomy (Fig. 6). This study showed that the retraction distance of the frontal lobe is not uniformly proportional to the tumor size, as the tangential direction of the visual axis toward the apex of the tumor varies with tumor size. A previous study examined the effects of orbitotomy in the supraorbital approach based on a specific height point in the midline of the sphenoid plane9. However, it is important to consider that the location of the tumor apex to be surgically exposed may vary depending on tumor size since skull base tumors do not usually grow unidirectionally but omnidirectionally, becoming hemispherical, as in this study. To our knowledge, this is the first anatomical study to consider the morphology of skull base tumors. The results of this study are likely to provide a closer approximation of real-life surgery than previous anatomical studies using virtual reality technology. However, due to technical limitations, this study could not simulate factors affecting frontal lobe elevation, such as tumor hardness or dissection of the Sylvian fissure. Further investigations are warranted to explore the extent to which these factors influence surgical outcomes.

A schematic diagram illustrating how the intraoperative visual axis changes depending on tumor size and whether orbitotomy is performed. For small tumors, the visual axis is directed from above, looking downward, requiring exposure of the area near the midline as the tumor apex during surgery. In this case, the effects of orbitotomy are minimal. In contrast, for large tumors, the visual axis is directed from below, looking upward, so the area outside the midline becomes the tumor tip that should be exposed, making the effects of orbitotomy more pronounced. Asterisk: tumor apex on the midline; black arrow: visual axis toward the tumor apex in the supraorbital approach; red arrow: visual axis toward the tumor apex in the supraorbital approach with orbitotomy; black dotted line: retraction distance of the frontal lobe in the supraorbital approach; red dotted line: retraction distance of the frontal lobe in the supraorbital approach with orbitotomy.

Differences in the effectiveness of orbitotomy according to tumor size

The results of this study showed that the effects of orbitotomy using the supraorbital approach increased with tumor size, reaching a maximum effect for tumors 40 mm or larger (Fig. 5). In addition, these effects were seen for tumors of 20 mm, although to a lesser extent (0.8 mm). Our results are consistent with previous reports suggesting that the addition of orbitotomy to the supraorbital approach effectively expands the operative field, particularly when looking upward from the caudal side. This concordance supports the validity of our findings9. Owing to the orbital bulge, the tuberculum sellae is usually located on the caudal side of the orbital rim. Therefore, when the tumor is small, looking up from the caudal side when exposing the tumor apex using the supraorbital approach is less needed, and orbitotomy is presumably less effective (Fig. 6). However, when the tumor size is large, the angle of the visual axis looking up from the caudal side becomes steeper with orbitotomy, causing the apex of the tumor exposed during surgery to shift further laterally, which enhances the effect of reducing the retraction distance (Fig. 6).

This study showed, for the first time, the effects of orbitotomy according to tumor size using the supraorbital approach. Furthermore, this is the first report of a quantitative evaluation of the effects of orbitotomy based on the brain retraction distance. As reports of increased postoperative complications with the addition of orbitotomy exist in the literature, careful consideration is required in its application27. The study’s findings indicate that the effectiveness of orbitotomy is maximized for tumors measuring ≥ 40 mm, suggesting that orbitotomy should be considered in such cases. However, the lack of comparisons with clinical data, such as postoperative complications, highlights the need for further research to validate these findings and establish more comprehensive guidelines.

In addition, although this study evaluated the effect of orbitotomy for tuberculum sellae meningiomas based on brain retraction distance, it should be noted that the endoscopic endonasal approach generally allows access to the tumor without brain retraction. Nevertheless, the endoscopic endonasal approach carries inherent risks, such as postoperative cerebrospinal fluid leakage and pituitary gland injury, and complete resection can be challenging in cases with lateral extension beyond the internal carotid artery. In clinical practice, the choice of surgical approach should be carefully tailored to each individual case, and the findings of this study are expected to serve as one of the factors to consider when determining the optimal approach for each patient.

Risk of brain retraction injury

Several reports have documented brain retraction injury; however, the degree of brain retraction at which the contusion occurs has not been explored11. Although some studies have previously stratified the risk of brain retraction injury through a quantitative evaluation of pressure, these reports are based on animal experimental data, and risk evaluation in actual surgery is still insufficient11,28,29,30,31. The novel research method developed in this study enables the estimation of the intraoperative brain retraction distance. While the clinically acceptable limits of brain retraction distance remain unclear, applying the method developed in this study to actual surgical cases is expected to help determine the retraction distance at which brain retraction injury occurs, a subject that remains a topic for future research (Fig. 7). Additionally, factors such as tumor adhesion to the brain and vessels and tumor stiffness may also contribute to brain retraction injury. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that this method allows for quantitative preoperative prediction of retraction distance. As research on the relationship between retraction distance and brain retraction injury accumulates in the future, it is expected that the findings of this study will contribute to the establishment of quantitative criteria for the skull base approach, ultimately improving clinical outcomes. Furthermore, investigating how reduced brain retraction influences long-term patient recovery and neurological function is expected to highlight the clinical relevance of orbitotomy further. This is an important direction for future research.

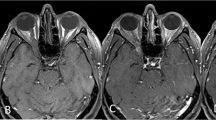

Estimation of brain retraction distance in a case of tuberculum sellae meningioma resected via the supraorbital approach (a, b). To expose the tumor apex, retraction of the frontal lobe was required (c). Using simulation software, we retrospectively replicated the surgical procedure (d, e) and measured the frontal lobe retraction distance using the method developed in this study, calculating it to be 7.2 mm (f). This figure demonstrates the use of simulation software to estimate intraoperative brain retraction distance by referencing actual surgical videos and replicating frontal lobe retraction maneuvers.

ON: optic nerve.

Usefulness and future challenges of virtual reality technology in anatomical research

Virtual reality technology has been previously used in several anatomical studies9,12,13,14,15,16,17. However, owing to technical limitations, reports examining soft tissue deformations, such as the brain retraction distance, are lacking9. Additionally, as the brain tissue degenerates during the donation preservation process, intraoperative brain deformation is challenging to verify, even in cadaveric studies9. Finally, securing multiple cadavers with skull base tumors of uniform size and morphology is challenging, making it difficult to quantitatively evaluate the effects of orbitotomy according to tumor size in cadaver studies. These issues were addressed in this study and made possible by the developments of virtual reality technology.

One of the main advantages of anatomical studies using virtual reality technology is the availability of large amounts of imaging data, which are difficult to obtain with cadaveric studies9. Another advantage, as demonstrated in this study, is the ability to create multiple skull base tumor models with uniform tumor size and morphology and to align different conditions. This approach will enable more rigorous anatomical studies and thorough reassessment of the indications for skull base surgery, which have traditionally been based solely on the surgeon’s experience.

In contrast, using virtual reality technology in anatomical research presents certain issues that need to be resolved. Notably, this study does not strictly reproduce the actual surgical procedure; further investigation is warranted regarding the common technique of dissecting the tumor from the brain by debulking tumors and pulling the apex into the cavity. In actual surgery, tumor debulking is often easier, particularly in the case of soft tumors, which may require less frontal lobe elevation than indicated by this study’s results. In addition, the enhanced visualization provided by endoscopic assistance was not evaluated in this study and remains an important subject for future investigation. Furthermore, this study is an in-silico analysis, and its relevance to clinical outcomes, such as complications, warrants further exploration in future research.

Despite these challenges, this study represents a significant advancement in anatomical research in neurosurgery. We successfully estimated the extent of brain deformation during surgery by employing a novel methodology—an achievement that had been difficult to realize until now. Considering tumor size and morphology, we calculated theoretical values for frontal lobe elevation distances using actual clinical data. This study does not perfectly replicate actual surgical conditions; however, it provides a concrete measure of frontal lobe elevation distances during surgery, which had previously lacked any reference point. This achievement is expected to provide a valuable guideline when selecting a craniotomy approach. In this study, the absence of defined MRI sequence selection criteria for preoperative evaluation limited the availability of usable patient data. Hence, establishing such criteria and prospectively collecting patient data is expected to enable the inclusion of a larger and more diverse patient population, offering more comprehensive insights. In addition, comparing the supraorbital approach augmented by orbitotomy with other craniotomy techniques, such as the pterional and orbitozygomatic approaches, may further clarify its unique advantages and characteristics. This is an important direction for future research.

Limitations

One limitation of this study is that it did not consider the presence of vessels and cranial nerves when measuring the distance of frontal lobe retraction. This is owing to the inability to represent brain deformations that consider physical properties in the simulation software used in this study. Therefore, the approach used in this study does not fully recreate an actual surgery scenario. Nevertheless, the supraorbital approach involves a limited number of vessels and cranial nerves, and a sufficient arachnoid incision can increase frontal lobe mobility. Therefore, it is inferred that the findings of this study closely approximate those of actual surgery. In addition, integrating vessels and cranial nerves into simulations by retrospectively mimicking the surgical field with reference to actual surgical videos may enable a more detailed investigation of brain deformation (Fig. 7). This is a promising direction for future research.

Another limitation of this study is that the results are based solely on estimated values derived from computer simulations. Due to technical constraints, validation through comparisons with cadaveric studies or actual surgical cases has not been performed, and therefore caution is required when referring to these findings in the selection of surgical approaches. Although future technological advances might make it possible to validate the simulation results by comparing them with actual surgical cases, no such studies have been reported to date, and further research is warranted.

Conclusions

This study’s findings demonstrate the effects of orbitotomy in the supraorbital approach, as measured by the distance of frontal lobe retraction. Owing to the morphology of the tumor and anterior cranial fossa, surgery using the supraorbital approach resulted in the greatest frontal lobe retraction distance to expose the tumor apex when the tuberculum sellae meningioma was 40 mm. In addition, the effects of orbitotomy are greatest when the tumor size is 40 mm or larger, which is considered one of the criteria for indicating orbitotomy. The novel research method established in this study takes advantage of virtual reality technology, enabling the quantitative evaluation of brain tissue deformation, which is difficult to assess in conventional cadaveric studies. These findings have practical implications for preoperative planning by providing surgeons with objective data to guide the selection of the most appropriate surgical approach. In addition, the simulation framework developed in this study holds significant potential for advancing surgical training by replicating diverse clinical scenarios, thereby enhancing surgeon preparedness and improving patient outcomes.

Data availability

The dataset used for the statistical analysis in this study has been included as Supplementary Material. However, the original data of the three-dimensional models used in this study are not publicly available due to privacy protection concerns but can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Reisch, R. & Perneczky, A. Ten-year experience with the supraorbital subfrontal approach through an eyebrow skin incision. Neurosurgery 57, 242–255. https://doi.org/10.1227/01.neu.0000178353.42777.2c (2005). discussion 242–255.

Peng, Y., Fan, J., Li, Y., Qiu, M. & Qi, S. The supraorbital keyhole approach to the suprasellar and supra-intrasellar Rathke cleft cysts under pure endoscopic visualization. World Neurosurg. 92, 120–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2016.04.121 (2016).

van Lindert, E., Perneczky, A., Fries, G. & Pierangeli, E. The supraorbital keyhole approach to supratentorial aneurysms: Concept and technique. Surg. Neurol. 49, 481–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0090-3019(96)00539-3 (1998). discussion 489–490.

Thaher, F. et al. Supraorbital keyhole approach to the skull base: evaluation of complications related to CSF fistulas and opened frontal sinus. J. Neurol. Surg. Cent. Eur. Neurosurg. 76, 433–437. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1389368 (2015).

Aljuboori, Z. et al. Orbitofrontal approach for the fenestration of a symptomatic sellar arachnoid cyst. Surg. Neurol. Int. 11, 10. https://doi.org/10.25259/SNI_541_2019 (2020).

Cuellar-Hernandez, J. J. et al. Intrasellar cysticercosis cyst treated with a transciliary supraorbital keyhole approach - a case report. Surg. Neurol. Int. 11, 436. https://doi.org/10.25259/SNI_755_2020 (2020).

Romani, R. et al. Lateral supraorbital approach applied to olfactory groove meningiomas: experience with 66 consecutive patients. Neurosurgery 65, 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1227/01.NEU.0000346266.69493.88 (2009). discussion 52 – 33.

Yamashiro, K. et al. A case of Sellar arachnoid cyst operated using the endoscopic supraorbital keyhole approach. Neurosurg. Pract. 4. https://doi.org/10.1227/neuprac.0000000000000069 (2023).

Tai, A. X., Sack, K. D., Herur-Raman, A. & Jean, W. C. The benefits of limited orbitotomy on the supraorbital approach: An anatomic and morphometric study in virtual reality. Oper. Neurosurg. (Hagerstown). 18, 542–550. https://doi.org/10.1093/ons/opz201 (2020).

Cavalcanti, D. D. et al. Quantitative anatomic study of the transciliary supraorbital approach: Benefits of additional orbital osteotomy? Neurosurgery 66, 205–210. https://doi.org/10.1227/01.NEU.0000369948.37233.70 (2010).

Roca, E. & Ramorino, G. Brain Retraction injury: systematic literature review. Neurosurg. Rev. 46, 257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-023-02160-8 (2023).

Ha, W. et al. Anatomical study of suboccipital vertebral arteries and surrounding bony structures using virtual reality technology. Med. Sci. Monit. 20, 802–806. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.890840 (2014).

Qian, Z. H., Feng, X., Li, Y. & Tang, K. Virtual reality model of the Three-Dimensional anatomy of the cavernous sinus based on a cadaveric image and dissection. J. Craniofac. Surg. 29, 163–166. https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0000000000004046 (2018).

Saez-Alegre, M. et al. The TIGR triangle of the pineal region: a virtual reality anatomic study. Acta Neurochir. (Wien). 165, 4083–4091. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-023-05880-4 (2023).

Serrano, L. E. et al. Comprehensive anatomic assessment of ipsilateral pterional versus contralateral subfrontal approaches to the internal carotid ophthalmic segment: A cadaveric study and Three-Dimensional simulation. World Neurosurg. 128, e261–e275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.04.134 (2019).

Tai, A. X., Herur-Raman, A. & Jean, W. C. The benefits of progressive occipital condylectomy in enhancing the Far lateral approach to the foramen magnum. World Neurosurg. 134, e144–e152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2019.09.152 (2020).

Tai, A. X., Srivastava, A., Herur-Raman, A., Cheng Wong, P. J. & Jean, W. C. Progressive orbitotomy and graduated expansion of the supraorbital keyhole: A comparison with alternative minimally invasive approaches to the paraclinoid region. World Neurosurg. 146, e1335–e1344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2020.11.173 (2021).

Cheng, C. M. & Dogan, A. Quantitative measurement of the surgical freedom for anterior communicating artery complex-a comparative study between the frontotemporal pterional and supraorbital craniotomy; a laboratory study. Acta Neurochir. (Wien). 161, 2513–2519. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-019-04097-8 (2019).

Yagmurlu, K. et al. Quantitative anatomical analysis and clinical experience with mini-pterional and mini-orbitozygomatic approaches for intracranial aneurysm surgery. J. Neurosurg. 127, 646–659. https://doi.org/10.3171/2016.6.JNS16306 (2017).

da Silva, S. A. et al. Pterional, Pretemporal, and orbitozygomatic approaches: Anatomic and comparative study. World Neurosurg. 121, e398–e403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2018.09.120 (2019).

Westarp, E. et al. Virtual reality for patient informed consent in skull base tumors and intracranial vascular pathologies: A pilot study. Acta Neurochir. (Wien). 166, 455. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-024-06355-w (2024).

Joseph, F. J., Vanluchene, H. E. R. & Bervini, D. Simulation training approaches in intracranial aneurysm surgery-a systematic review. Neurosurg. Rev. 46, 101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-023-01995-5 (2023).

Roh, T. H. et al. Virtual dissection of the real brain: integration of photographic 3D models into virtual reality and its effect on neurosurgical resident education. Neurosurg. Focus. 51, E16. https://doi.org/10.3171/2021.5.FOCUS21193 (2021).

Guo, J., Zhang, P., Zhang, K. & Yang, X. How I do it: preoperative simulation and augmented reality assisted surgical resection of glioblastoma in broca’s area. Acta Neurochir. (Wien). 166, 481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-024-06368-5 (2024).

Kin, T. Virtual reality surgical simulations using fusion three-dimensional images. No Shinkei Geka. 52, 240–247. https://doi.org/10.11477/mf.1436204907 (2024).

Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transpl. 48, 452–458. https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2012.244 (2013).

Pivazyan, G. et al. Clinical outcomes and complications of eyelid versus eyebrow approaches to supraorbital craniotomy: Systematic review and indirect meta-analysis. Neurosurg. Focus. 56, E13. https://doi.org/10.3171/2024.1.FOCUS23878 (2024).

Thiex, R., Hans, F. J., Krings, T., Sellhaus, B. & Gilsbach, J. M. Technical pitfalls in a porcine brain retraction model: The impact of brain spatula on the retracted brain tissue in a porcine model: A feasibility study and its technical pitfalls. Neuroradiology 47, 765–773. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00234-005-1426-0 (2005).

Hongo, K., Kobayashi, S., Yokoh, A. & Sugita, K. Monitoring Retraction pressure on the brain: An experimental and clinical study. J. Neurosurg. 66, 270–275. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1987.66.2.0270 (1987).

Gelb, A. W., Karlik, S., Wu, X. & Lownie, S. Brain Retractor edema during induced hypotension: The effect of the rate of return of blood pressure. Neurosurgery 27, 901–906. https://doi.org/10.1227/00006123-199012000-00007 (1990).

Rosenorn, J. & Diemer, N. The risk of cerebral damage during graded brain retractor pressure in the rat. J. Neurosurg. 63, 608–611. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1985.63.4.0608 (1985).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Editage (www. editage.com) for their English language editing of our manuscript. We are also deeply grateful to Professor Hisatomi Arima, Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, Fukuoka University, for his expert review and constructive suggestions regarding the statistical analysis of this study.

Funding

This research was conducted with a Grant from The Clinical Research Promotion Foundation (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: KY. Data collection: KY. Data Analysis: KY. Article Writing: KY. Article Revision: all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial interests to disclose. Dr. Kei Yamashiro is a member of the Editorial Board of Scientific Reports, but had no involvement in the peer-review or editorial decision-making process for this manuscript.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Fukuoka University, Fukuoka, Japan (approval number: U24-06-015).

Consent to participate

In the present study, the opt-out method was used to recruit participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yamashiro, K., Fukumoto, H., Kobayashi, H. et al. Virtual reality based quantitative evaluation of the effect of orbitotomy on frontal lobe retraction during tuberculum sellae meningioma surgery. Sci Rep 16, 30 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28722-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28722-y