Abstract

Neural networks demonstrate exceptional predictive performance across diverse classification tasks. However, their lack of interpretability restricts their widespread application. Consequently, in recent years, numerous researchers have focused on model explanation techniques to elucidate the internal mechanisms of these ‘black box’ models. Yet, prevailing explanation methods predominantly focus on elucidating individual features, thereby overlooking synergistic effects and interactions among multiple features, potentially hindering a comprehensive understanding of the model’s predictive behavior. Therefore, this study proposes a two-stage explanation method, known as Pseudo Datasets Perturbation Effect (PDPE). The fundamental concept is to discern feature importance by perturbing the data and observing its influence on prediction outcomes. Under structured data, this method identifies potential feature interactions while evaluating the relative significance of individual features and their interaction terms. Compared with the widely recognized SHAP Value method, our computer simulation studies within the context of neural networks approximating the linear association of logistic regression demonstrate that PDPE provides faster, more accurate explanations. PDPE helps users understand the significance of individual features and their interactions for model predictions. Additionally, using real-life data from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the analysis results also show the superior performance of the new approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) yield excellent predictions across various classification tasks1,2,3. However, their highly complex and nonlinear nature renders the decision-making process opaque, often likened to a “black box”. This lack of transparency poses significant limitations, especially in healthcare, which demands high security and accountability. Ignoring explainability can threaten the core ethics of medicine and patient safety4, and erroneous or biased predictions may directly harm patients5. Therefore, European regulations governing Medical AI require human assessment before taking action based on the model’s predictions6. Similarly, the U.S. AI Bill of Rights (Blueprint) emphasizes the principle of Notice and Explanation7. At the same time, the FDA’s AI/ML Discussion Paper notes the importance of maintaining appropriate transparency and clarity in the algorithm and its outputs for users within its Total Product Lifecycle (TPLC) approach8. In light of this, a new research domain has emerged: explainable artificial intelligence (Explainable AI; XAI). XAI aims to explain AI model predictions, facilitate model analysis9, identify data bias5,10, help clinicians make informed judgments when algorithmic outputs conflict with clinical experience, and offer insights for medical diagnoses11. By translating complex model results into comprehensible information, XAI also enables patients to understand the potential outcomes of different treatment options, serving as a key bridge for enhancing doctor–patient communication and shared decision-making4. Thus, XAI is crucial for advancing deep learning applications in sensitive areas, such as healthcare12,13,14,15,16.

Explanation methods for neural networks are categorized into interpretable models (model-based explanations) and post-hoc explanations. Interpretable models are transparent by design. Examples include Neural Additive Models (NAMs), which combine deep neural networks with Generalized Additive Models (GAMs), where each input feature is associated with a separate neural network, and the final prediction is a linear combination of these networks, clarifying the relationship between features and predictions17. Another example is Neural Local Smoother (NLS), which structures the neural network such that each input neuron has a corresponding output neuron, with output neurons reflecting input feature importance scores18. Interpretable generalized additive neural networks (IGANN) is a stagewise, GAM-based method: it starts from a linear baseline and, at each iteration, adds a single-hidden-layer base composed of one-dimensional, single-feature components to correct residual structure without introducing interactions. Input weights are randomly drawn and fixed, and only the new bases’ output weights are estimated via regularized linear least squares; the step’s contribution is added with step size s, earlier parameters remain frozen, and training stops by early stopping or preset maximum number of bases19. NeuralGAM proceeds via two nested iterations: the outer loop computes the adjusted response and sample weights under the current model; the inner loop then trains a separate network for each feature using weighted partial residuals and recenters the fitted functions. The process repeats until the functions converge, after which the outer loop checks whether the reduction in deviance is sufficient20. Although the above architecture improves interpretability, GAM-based additive models are vulnerable to non-identifiability when there is linear or nonlinear correlation among features, making the learned shape-function interpretations non-unique and unstable21. Moreover, models often face a trade-off between accuracy and interpretability. Constraining model architecture to enhance interpretability might hinder the ability to learn complex patterns, leading to suboptimal performance. Consequently, methods that provide explanations for already trained models, known as post-hoc explanations, have gained more attention in recent years. These approaches aim to elucidate the decision-making process of complex models without compromising their predictive accuracy.

Post-hoc explanation methods include gradient-based and perturbation-based approaches. Gradient-based methods utilize the parameters trained by the model to infer feature importance. For instance, Bach et al.22 proposed Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP), which backpropagates the activation value of the target class to highlight significant features. Sundararajan et al.23 introduced integrated gradients to address gradient saturation by calculating feature importance via gradient integrals. Montavon et al.24 proposed Deep Taylor Decomposition, which expands neuron activation values as polynomials for local approximation, thereby exploring feature contributions. However, these methods are primarily suited for Feedforward Neural Networks. They may not apply to Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), which limits their use in natural language processing (NLP) and time series prediction tasks.

Perturbation-based methods assess feature importance by altering the original data or masking input features and observing changes in predictions. These approaches are model-agnostic. Zeiler and Fergus25 introduced Occlusion Sensitivity, which examines changes in output when parts of an image are occluded, revealing crucial areas for classification. This method laid the foundation for subsequent XAI research. Later studies varied the perturbation types—random occlusion, noise addition, or specific transformations—and the perturbation area sizes26,27,28. However, the relative merits of these techniques are still debated. Among the numerous explanation methods, two of the most notable are Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME)29 and SHAP Values30. LIME approximates a complex model locally with a simpler one by randomly perturbing the data and fitting a linear model to the perturbed dataset. It then uses the estimated coefficients to explain the contribution of each feature to the prediction results29. However, it may fail with complex data structures or feature interactions. Based on the Shapley value from game theory, SHAP Values calculate feature importance by averaging the weighted marginal contributions across all combinations30. SHAP is integrated into many AutoML/AutoAI tools, but is computationally intensive. It also fails to account for interactions between multiple variables, which are crucial in complex models.

To address feature interaction identification in neural network models, Yang et al. proposed GAMI-Net31. This model consists of main-effect and pairwise-interaction modules, each modeled using neural networks. The main effect module generates output from a single input node, while the interaction module generates output from two input nodes. Although GAMI-Net captures complex relationships, it initially screens important main effects before considering interactions, potentially missing significant multi-feature contributions. Additionally, its three-stage training process—selecting main effects, screening interactions, and combining these for training—is computationally intensive.

Post-hoc explanation methods do not require extensive training. Neural Interaction Detection (NID) by Tsang et al.32 detects feature interactions by analyzing the weight matrix of the first hidden layer of a neural network. However, NID is limited to feedforward networks and may overlook more profound or cumulative interactions, failing to capture prediction patterns fully. Harris et al.33 proposed Joint Shapley Values, extending SHAP to evaluate the average contribution of feature sets. While this method accounts for multiple features, it requires significant computational resources. Additionally, it may incorrectly assess feature importance by treating negative contributions as positive ones, leading to inaccurate evaluations.

Based on the existing research literature, no current method effectively predicts joint effects and interactions among features across all models without missing potential feature importance, while remaining computationally efficient and accurately interpreting features. To address this gap, this study aims to develop a new two-stage method that is simpler, faster, and capable of correctly explaining the contributions of individual features and the joint and interaction effects between features. Building on a recent methodology34 that addresses continuous output features, this research further uses pseudo-datasets to examine interactions and tackle the dichotomous outcome features. Since SHAP has dominated the field of machine learning explanation methods in recent years, the new approach is compared with SHAP.

Materials and methods

Pseudo datasets perturbation effect (PDPE)

Logistic regression coefficients provide insights into both the magnitude and the direction of a feature’s effect on a dichotomous outcome. Hence, logit models have become one of the most popular explainable AI in machine learning research. Thus, this study utilizes logistic regression coefficients as a metric for explanation efficacy. Previous research has shown that neural networks are a generalization of logistic regression35. Theoretically, simplifying a neural network to a single neuron without hidden layers results in logistic regression. Consequently, we strive to optimize the neural network architecture during the modeling stage to closely approximate logistic regression outputs, providing empirical evidence of PDPE validity. In simulation studies, we focus on logistic regression coefficients to evaluate the accuracy of the neural network’s explanation method, PDPE.

Our approach employs a perturbation-based methodology within the realm of explainable AI classification, building upon a recent method for continuous output features with detailed mathematical derivations34. Similarly, the first step of PDPE involves optimizing hyperparameters and network parameters by fitting neural networks to the original dataset. The estimated results serve as the reference predictions, as illustrated in the analysis flow on the left side of Fig. 1. The next step is to measure how an input neuron impacts the predicted value when the input changes. Therefore, we generate a pseudo dataset based on the data types of the input features, as shown in the two analysis flows on the right side in Fig. 1. Lastly, this technique measures feature importance by systematically perturbing the input data and observing the resultant changes in prediction outcomes (the predicted value in Fig. 1).

Neural networks are capable of complex nonlinear structures. In contrast, logistic regression applies to linear patterns, which is also the simplest structure in machine learning. Here, we focus on comparing logistic regression, SHAP, and PDPE in the simplest scenario to make PDPE’s superiority convincing. Using a complex data structure for logistic regression may not provide fair comparisons.

According to the insights of logistic regression, our perturbation method operates as follows: For continuous input features, the calculation of the importance score for a single feature is as follows: under the condition that all other features are adjusted, the probability change resulting from increasing the feature \({X}_{i}\) by one standard deviation. Regarding categorical inputs, the calculation involves comparing the predicted values when \({X}_{i}\) equals 1 and 0, with other variables held constant. The resulting predicted values obtained through these computations represent the relative importance of individual features in terms of their impact on predictive probability, noted as the ‘Main Effect’.

Unlike previous work34, which provided insights of a single input feature, this study aims to explain the joint and interaction effects between two inputs that simultaneously influence the prediction. If there is an interaction effect between \({X}_{1}\) and \({X}_{2}\) among K features, the logit model is \(\text{Logit}\left(\text{P}\right)={\beta }_{0}+{\beta }_{1}{X}_{1}+{\beta }_{2}{X}_{2}+{{\beta }_{i}X}_{1}{X}_{2}+\cdots +{\beta }_{k}{X}_{k}.\) The joint effect of \({X}_{1}\) and \({X}_{2}\) is assessed by testing \({\beta }_{1}={\beta }_{2}=0,\) while the test for interaction evaluates if \({\beta }_{i}=0.\) Similar to the concept of interaction in epidemiology36. The interaction effect could be estimated by the impact of the presence of \({X}_{1}\) and \({X}_{2}\) substracting (Eq. 1) that of \({X}_{1}\) alone and \({X}_{2}\) alone (Eq. 2).

Equations 1 serves as the joint effect of \({X}_{1}\) and \({X}_{2}.\) In contrast, Eq. 2 represent the sum of the individual effects of \({X}_{1}\) and \({X}_{2}.\) Therefore, we employ a two-stage methodology for neural networks that mimics Eqs. 1 and 2 in logit models. The joint effect of \({X}_{i}\) and \({X}_{j},\) subtracting the sum of their individual effects, could estimate the interaction effect in neural networks. Subsequnetly, we develop a statistical test for the interaction effect between the two input features as explainable AI in neural networks.

Given that the input features comprise a mix of continuous and categorical variables, we examine three scenarios of interaction in the simulation study. Firstly, when both features are continuous variables, we compute the change in probability resulting from incrementing both features by one standard deviation. Secondly, in cases where both features are categorical variables, we calculate the probability change when both features are set to 1 and when both are set to 0. Lastly, when one feature is continuous and the other categorical, we increase the continuous feature by 1 standard deviation and set the categorical feature to 1 to obtain the predicted probability (as shown in the three analysis flows on the right side of Fig. 2). The disparity between these probabilities represents the joint effect of the two inputs in neural networks with a concept similar to Eq. 1. Note that the sum of individual effects in neural networks, which assemble Eq. 2, is available in the steps that calculate the relative importance of each feature (\({X}_{1}, {X}_{2},\dots ,{X}_{k}\)) in Fig. 1.

The personal difference between the joint effect and the sum of individual effects leads to a statistical test, as illustrated in Fig. 3. P-values below 0.05 are considered a significant interaction effect.

Simulation study

Since logistic regression coefficients span the entire real number space, while the feature importance scores obtained by our method (PDPE) and the previous method (SHAP value) range between − 1 and 1, a standardized scale is necessary for comparative analysis. As a result, we normalize the importance score of each feature by dividing it by the sum of the absolute values of all feature importance scores. This normalization ensures that the relative sizes of the scores can be compared within the same range.

Simulated data

A larger sample size would result in smaller standard errors, but also increase the computational burden. Since sample size was not a concern in previous work34, we present simulation studies using 1,000 samples. The target variable, denoted as Y, is binary. The simulated dataset consists of 10 features, generated randomly from a multivariate normal distribution. Among these features, the first five \(({X}_{1}, {X}_{2}, {X}_{3}, {X}_{4}, {X}_{5})\) are continuous variables, and the remaining five are categorical variables represented as \({X}_{i}=\text{I}\left({X}_{i}\ge 0\right),\) where \(i\) ranges from 6 to 10.

There are three distinct scenarios based on the relationship between X and Y. In scenario one, we assume no relationship between Y and X; hence, Y is independently generated according to the Binomial distribution. The second scenario assumes a relationship defined as: \(Y=f\left({\varvec{X}}\right)=I(sigmoid({X}_{1}-0.6{X}_{2}+0.4{X}_{3}+0.7{X}_{6}+0.1{X}_{7}-0.8{X}_{8}+\varepsilon )>0.5).\) The third scenario incorporates a \(-0.4\) interaction effect between \({\text{X}}_{1}\) and \({\text{X}}_{2}.\) Specifically, the relationship is defined as: \(Y=\text{I}(\text{sigmoid}\left({\text{X}}_{1}+0.7{\text{X}}_{2}-0.2{\text{X}}_{7}-0.4{\text{X}}_{1}{\text{X}}_{2}+\varepsilon \right)>0.5).\) Furthermore, uncertainty exists in real-world data with a random error \(\varepsilon \sim N(\text{0,1}).\)

In each scenario, we considered two cases based on the relationship between the input features. The first case assumes independence, implying a covariance matrix equivalent to the identity matrix. Conversely, the second situation introduces correlations among the input features, characterized by the following covariance matrix:

We employed six distinct sets of simulation data, and to ensure the stability of our estimates, we repeated the execution 100 times.

Real-world datasets

The real-world dataset is obtained through Kaggle, the Diabetes Dataset, which originates from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The study population consists of Indian women aged 21 years or older.

The explanatory variables within this dataset include: Pregnancies, Glucose, BloodPressure, SkinThickness, Insulin, BMI, DiabetesPedigreeFunction, and Age. The output feature is whether the participant has diabetes.

Given the presence of some anomalous data points, such as diastolic blood pressure being recorded as 0 and BMI as 0, we replaced these values with the sample mean. Supplementary Table 1 provides detailed information regarding the distribution of the corrected data.

Hyper parameters and parameters

In simulations, we trained a fully connected feed-forward neural network with a single hidden layer of 2 neurons. Optimization used resilient backpropagation without weight backtracking, with cross-entropy as the objective. All units employed the sigmoid activation, which smoothly maps each unit’s weighted input to (0,1). Training stops when the absolute partial derivatives of the loss fall below 0.05 or when the maximum step count of 100,000,000 is reached. A learning rate of 0.0001 was specified. For reproducibility, we set the random seed to 'set.seed(3)' before initializing the model. For the real-data analysis, we put the learning rate to 0.003, the threshold to 0.01, and reduced the maximum step count to 100,000; all other settings were identical to those in the simulation.

To compute SHAP values, we used the ‘iml’ package’s model-agnostic Shapley method on a per-instance basis. The technique treats an instance’s feature values as cooperating players. It fairly apportions the difference between the instance’s prediction and the dataset’s average prediction across features, estimating contributions via Monte Carlo sampling of feature coalitions (using 100 samples by default).

All simulations and real-data analyses were conducted on a workstation equipped with a 12th-Generation Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-12500H processor and 32 GB of DDR5-4800 SODIMM memory.

Results

This study used R (version 4.3.2) and the ‘MASS’ and ‘sigmoid’ packages to generate simulation data. The neural network model was constructed using the ‘neuralnet’ package. In contrast, functions from the ‘caret’ and ‘pROC’ packages were employed to evaluate the predictive accuracy of both the neural network and logistic regression models. SHAP values were calculated using the ‘iml’ package. Finally, the ‘ggplot2’ package facilitated the visual presentation of the research findings.

Simulation study

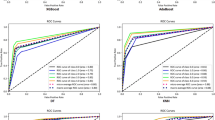

In Scenario 1, where Y and X exhibit no correlation, two distinct scenarios are illustrated in Tables 1, 2 and Figs. 4, 5. Table 1 and Fig. 4 illustrate the case where the X variables are independent, whereas Table 2 and Fig. 5 depict a scenario with correlations among the input features. Both figures consistently demonstrate estimated values hovering around zero, aligning precisely with our predetermined hypothesis: that X lacks predictive utility for Y. Further detailed numerical findings are presented in Supplementary Table 2. Notably, both Figs. 4 and 5, as well as Supplementary Table 2, underscore a significant observation: when features are perturbed by 1 standard deviation, the resulting impact on logistic regression and neural network predictions remains remarkably similar. This observation suggests that our neural network model can closely approximate the logistic regression model. The simulation results indicate that PDPE’s explanation is robust and valid.

It is evident from the findings presented in both Tables 1 and 2 that the feature importance scores derived from PDPE and SHAP Value are close to zero. The results align with the estimated coefficients of the logistic regression, which also approximate zero. Such consistency aligns seamlessly with our predefined hypothesis: since Y and X are independent, each feature holds negligible predictive power. Furthermore, our approach enables the extraction of the combined effect of the two variables. Given the proximity of each feature’s importance to zero in predicting the outcome in Scenario 1, the overall comprehensive effect similarly tends towards zero, as evidenced in Supplementary Table 3. Based on the simulations, we conclude that PDPE’s feature importance score estimates are more accurate than SHAP’s, as they are generally smaller and closer to zero.

For scenarios involving the association between Y and X (Scenario 2), we explore two distinct situations. Scenario 2–1 represents the scenario where components of X are independent (Table 3 and Fig. 6), while Scenario 2–2 depicts a correlated X (Table 4 and Fig. 7). From Figs. 6 and 7 and Supplementary Table 4, neural networks and logistic regression exhibit similar changes in predictive probabilities. This implies that the PDPE predictions closely resemble those of logistic regression, and regression coefficients can be utilized as a measure of explanatory effect in neural networks.

In terms of explanatory power, we employed logistic regression coefficients alongside individual feature importance scores derived from neural networks using explanation methods such as PDPE and SHAP Value. Upon standardization and conversion to a unified scale, we noted remarkable consistency between the feature importance scores obtained through our PDPE method and those from logistic regression. The rankings of importance align closely, as do the determinations of whether a feature contributes positively or negatively to the predicted outcome. Furthermore, we observed that SHAP Value tends to assign disproportionately large contributions to the most important features. However, SHAP struggles to identify the directional impact of features on prediction outcomes accurately and exhibits significant disparities in importance rankings compared to logistic regression. We highlighted the SHAP discrepancies in red in Tables 3 and 4. It is worth noting that SHAP values can yield incorrect feature importance directions in simple linear associations. Apart from the consistency in the top-ranked feature, the order of the second to fifth most important features differs. Detailed comparisons are provided in Tables 3 and 4 and Figs. 8, 9, 10, 11. Additionally, PDPE could assess the joint impact of simultaneous changes in two variables on prediction outcomes, thereby elucidating their combined effect, as outlined in Supplementary Table 5. Based on these findings, it becomes apparent that when Y is a function of X, our approach outperforms others.

In the final simulation scenario (Scenario 3), we adopt a two-stage approach to investigate potential interactions and their relative importance (Tables 5, 6, Figs. 12, 13, 14). The first step is to assess the joint effect of the two features and the cumulative impact of their individual effects. If there is a significant difference in the test results, it will be included as a potential interaction term. Table 5 indicates the possibility of an interaction between \({X}_{1}\) and \({X}_{2},\) consistent with our predefined scenario. Subsequently, in step 2, we incorporate this potential interaction term into the model and compute the feature importance score.

The second step follows the same procedure as in the first two scenarios. Initially, we confirm that the predicted changes induced by feature perturbation in both the neural network and logistic regression models are highly similar. Figures 12 and 13 demonstrate that the output variations in both models closely resemble each other, suggesting that the neural network closely approximates logistic regression when assessing the interaction term. Therefore, we use the regression coefficient as the standard for explaining the interaction effect.

In terms of explanatory power, upon standardization, examination of Table 6 and Fig. 14 reveals a close alignment between the results from PDPE and logistic regression. Their directional judgments also exhibit consistency. However, SHAP Value fails to accurately identify negative contributions to the predictive outcomes for features \({X}_{7}\) and the interaction term \({X}_{1}{X}_{2}.\) Similar findings are also shown in Table 7 and Fig. 15, where SHAP becomes challenging to ascertain the importance of the interaction term \({X}_{1}{X}_{2}.\) We highlighted the SHAP discrepancies due to interactions in red in Tables 6 and 7. Therefore, PDPE offers a superior explanation of feature importance compared to SHAP Value, and it aligns well with the equations established in the simulation settings.

The execution time required to employ the XAI method is shown in Table 8. PDPE requires significantly less computation time compared to SHAP. This finding suggests that PDPE is an efficient approach.

Real-world datasets

In the diabetes dataset, we constructed a simplified neural network model to approximate logistic regression and applied PDPE to identify potential interaction terms. We randomly split the data into a training set (90%) and a testing set (10%). The trained network achieved 80.03% training accuracy (sensitivity 70.12%, specificity 85.33%) and 75.32% testing accuracy (sensitivity 70.37%, specificity 78.00%), indicating no apparent overfitting. The XAI outcomes are presented in Supplementary Table 6. Of the 28 two-variable combinations, 20 showed potential interactions. However, because incorporating non-existent interaction terms into logistic regression can yield inaccurate estimates, and given our preference for using regression coefficients as the benchmark for interpretation, caution is warranted to avoid erroneous conclusions. Therefore, we initially fitted a logistic regression model with each feature and these 20 potential interaction terms. We then selected interaction terms with p-values < 0.05 for inclusion in subsequent analyses, as shown in Supplementary Table 7. Notably, ' Pregnancies*Age’, 'Insulin*Diabetes Pedigree Function’ emerged as interaction terms slated for incorporation into the model.

Moving to the second stage, we initially verify that the neural network model closely approximates the logistic regression model. As illustrated in Table 9, the influence of perturbed characteristics on the output results of both models aligns closely, validating the use of logistic regression coefficients as the standard for explanation. Subsequently, we estimate the relative importance of features. Figure 16 demonstrates that PDPE yields estimates closer to those of logistic regression than SHAP Value, with consistent feature importance rankings. In summary, PDPE offers a more accurate explanation compared to SHAP Value.

Discussion

In this research, we employ a novel method, PDPE, a two-stage neural network explanation method that uses a perturbation approach to identify crucial features that influence model decisions. For continuous features, we evaluate feature importance by perturbing each feature by one standard deviation and observing the resulting changes in model output. For categorical features, we measure the difference in prediction probabilities when the observed feature is set to 1 versus 0, treating this difference as the feature’s importance score. Subsequently, these scores are normalized by the sum of absolute values to derive the relative importance of each feature. Since our approach is independent of model parameters and model-agnostic, PDPE can be used not only in feedforward neural networks but also in RNNs, SVMs, and other tree-based methods.

Based on computer simulations of neural networks approximating the linear association of logistic regression and real-world data analysis, we observed that PDPE provides a more precise explanation of neural network models than the widely used SHAP Value method under structured data. The comparisons under a much more complex nonlinear architecture remain an area for future research.

We observed that SHAP struggles to identify the direction of feature effects and can assign the wrong direction compared to logistic regression. We highlighted SHAP discrepancies in red in Tables 3 and 4 and noted the issue due to interactions in Tables 6 and 7. Detailed mathematical derivations and computer simulation studies are needed to address this phenomenon.

Moreover, PDPE demonstrates shorter execution times. Notably, PDPE effectively identifies potential feature interactions, enabling the computation of both joint and interaction effects. The research findings indicate that PDPE provides superior predictive performance for neural networks, offering more accurate, efficient, and advanced model explanations.

In this study, we observed that SHAP Values failed to produce accurate feature importance rankings in both simulation studies and real-world data analysis. This raises a significant question: Can the relative feature importance derived from XAI methods be applied for feature selection? In a further literature review, Fryer et al. (2021) discussed the application of Shapley value in feature selection in detail37. They highlighted limitations, noting that the Shapley value, as an average over all feature combinations, doesn’t accurately reflect performance within specific feature sets, making it unsuitable for evaluating feature performance in final models. Moreover, when two features exhibit high correlation and contribute equally to the target variable, from the perspective of the Shapley value, both features will have identical attribution values. High feature similarity implies redundancy, rendering feature selection based solely on Shapley values unsuitable. Additionally, Shapley value’s exclusive focus on positive feature impacts neglects negative impacts, rendering it inadequate for model explanation. Since SHAP Value relies on Shapley values for feature contribution calculations, interpretation biases in model results may arise, warranting cautious application of this method.

Limitations

In this study, we use logistic regression as the gold standard for explaining effects, thereby simplifying the neural network architecture to approximate it. However, oversimplifying the neural network may lead to an inability to fit the training data and to failure to converge to a stable solution during model training when hyperparameters or parameters are not optimized. Consequently, the program may encounter training failures when “threshold = 0.01 and learning rate = 0.0003”. To address this issue, we increase the maximum number of training steps and limit the number of simulations to 100 iterations to prevent neural network non-convergence. We also discovered an alternative solution to the convergence issue by replacing “threshold = 0.05” and “learning rate = 0.0001”. Therefore, researchers should be aware of the potential problems in neural networks.

Increasing the number of simulations will enable a more comprehensive evaluation of the explanation method’s effectiveness and robustness. However, our computing resources are very limited to a regular personal computer (PC). On the other hand, our approach does not require intensive computational requirements and can be easily implemented by any researcher. More importantly, current estimates are sufficient to declare a statistical decision in most situations. Take Table 3 as an example: the first row indicates that the SHAP feature importance (0.5058 (0.4979, 0.5137)) is statistically significantly different from that of LR (0.2609 (0.2579, 0.2640)), since the two confidence intervals do not overlap. Note that the comparisons between 100 and 500 repetitions are very close, as displayed in Supplementary Tables 78–9 and Supplementary Figs. 1, 2.

Regarding the Bonferroni correction for the multiple testing issue when searching for potential interactions. We deliberately refrain from applying multiplicity corrections in the first stage of PDPE to avoid discarding potentially relevant interactions. In the second stage, we fit the model and estimate effects with our XAI procedure. In both simulations and the real-data analysis, the resulting estimates closely match the logistic regression gold standard (see Figs. 12, 13, 14, 15, 16; Tables 6, 7, and 9).

In the issue of benchmarking against logistic regression as the “Gold Standard, our rationale is that if the simplest scenario does not provide superior performance, it is unnecessary to examine complex scenarios when no one is guaranteed to outperform in infinite settings and situations. Therefore, more advanced computer simulation studies on complex situations are crucial for future research.

Furthermore, our method is currently restricted to structured data, potentially limiting its application to data formats such as images, text, and speech. Hence, future research could explore leveraging the principles of PDPE to integrate alternative explanation methods and extend them to unstructured data. For instance, replacing the weighted value calculation component in commonly used image analysis methods, such as Grad-CAM38, Grad-CAM++39, and other CAM40 methods, with our approach. This involves integrating the feature map from the last convolutional layer and applying linear weights to produce a visual explanation.

Lastly, we normalize the feature importance scores using z-score, as recommended for machine learning approaches41. Different transformations of the original scales require further investigation.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Code availability

An R Code (Example of PDPE Method for Diabetes Dataset.R) that implements the proposed approach is included as supplementary materials.

References

Liu, C.-M. et al. Artificial intelligence-enabled model for early detection of left ventricular hypertrophy and mortality prediction in young to middle-aged adults. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 15(8), e008360 (2022).

Qiu, S. et al. Multimodal deep learning for Alzheimer’s disease dementia assessment. Nat. Commun. 13(1), 3404 (2022).

Tang, S. et al. Machine learning-enabled multimodal fusion of intra-atrial and body surface signals in prediction of atrial fibrillation ablation outcomes. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 15(8), e010850 (2022).

Amann, J. et al. Explainability for artificial intelligence in healthcare: a multidisciplinary perspective. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 20(1), 310 (2020).

Lu, S.-C. et al. On the importance of interpretable machine learning predictions to inform clinical decision making in oncology. Front. Oncol. 13, 1129380 (2023).

Schneeberger, D., K. Stöger, and A. Holzinger. The European legal framework for medical AI. In International Cross-Domain Conference for Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction. Springer (2020).

The White House, O. Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights: Making Automated Systems Work for the American People. (2022). Available from: https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/ostp/ai-bill-of-rights/.

FDA. Proposed regulatory framework for modifications to artificial intelligence/machine learning (AI/ML)-based Software as a Medical Device(SaMD). (2020). https://www.fda.gov/files/medical%20devices/published/US-FDA-Artificial-Intelligence-and-Machine-Learning-Discussion-Paper.pdf.

Tjoa, E. & Guan, C. A survey on explainable artificial intelligence (xai): Toward medical Xai. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 32(11), 4793–4813 (2020).

Yoon, C. H., Torrance, R. & Scheinerman, N. Machine learning in medicine: should the pursuit of enhanced interpretability be abandoned?. J. Med. Ethics 48(9), 581–585 (2022).

Liu, S. et al. Leveraging explainable artificial intelligence to optimize clinical decision support. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 31(4), 968–974 (2024).

Budhkar, A., et al. Demystifying the black box: A survey on explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) in bioinformatics. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. (2025).

Hildt, E. What is the role of explainability in medical artificial intelligence? A case-based approach. Bioengineering 12(4), 375 (2025).

Houssein, E. H. et al. Explainable artificial intelligence for medical imaging systems using deep learning: A comprehensive review. Clust. Comput. 28(7), 469 (2025).

Noor, A. A. et al. Unveiling explainable AI in healthcare: Current trends, challenges, and future directions. Wiley Interdiscipl. Rev. Data Mining Knowl. Discov. 15(2), e70018 (2025).

Räz, T., Pahud-De-Mortanges, A. & Reyes, M. Explainable AI in medicine: Challenges of integrating XAI into the future clinical routine. Front. Radiol. 5, 1627169 (2025).

Agarwal, R. et al. Neural additive models: Interpretable machine learning with neural nets. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 34, 4699–4711 (2021).

Coscrato, V. et al. NLS: An accurate and yet easy-to-interpret prediction method. Neural Netw. 162, 117–130 (2023).

Kraus, M. et al. Interpretable generalized additive neural networks. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 317(2), 303–316 (2024).

Ortega-Fernandez, I., Sestelo, M. & Villanueva, N. M. Explainable generalized additive neural networks with independent neural network training. Stat. Comput. 34(1), 6 (2024).

Zhang, X., J. Martinelli, and S. John, Challenges in interpretability of additive models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.10169 (2025).

Bach, S. et al. On pixel-wise explanations for non-linear classifier decisions by layer-wise relevance propagation. PLoS ONE 10(7), e0130140 (2015).

Sundararajan, M., A. Taly, and Q. Yan. Axiomatic attribution for deep networks. In International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR (2017).

Montavon, G. et al. Explaining nonlinear classification decisions with deep Taylor decomposition. Pattern Recogn. 65, 211–222 (2017).

Zeiler, M.D. and R. Fergus. Visualizing and understanding convolutional networks. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, September 6–12, 2014, Proceedings, Part I 13. Springer. (2014)

Fong, R.C. and A. Vedaldi. Interpretable explanations of black boxes by meaningful perturbation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision. (2017).

Petsiuk, V., A. Das, and K. Saenko, Rise: Randomized input sampling for explanation of black-box models. arXiv preprint arXiv:1806.07421. (2018).

Fong, R., M. Patrick, and A. Vedaldi. Understanding deep networks via extremal perturbations and smooth masks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision. (2019).

Ribeiro, M.T., Singh, S., Guestrin, C. “Why should i trust you?" Explaining the predictions of any classifier. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. (2016).

Lundberg, S. M. & Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30, 44698 (2017).

Yang, Z., Zhang, A. & Sudjianto, A. GAMI-Net: An explainable neural network based on generalized additive models with structured interactions. Pattern Recogn. 120, 108192 (2021).

Tsang, M., D. Cheng, and Y. Liu, Detecting statistical interactions from neural network weights. arXiv preprint arXiv:1705.04977, 2017.

Harris, C., R. Pymar, and C. Rowat, Joint Shapley values: a measure of joint feature importance. arXiv preprint arXiv:2107.11357, 2021.

Chu, Y.-C., Chen, Y.-H. & Guo, C.-Y. Pseudo datasets explain artificial neural networks. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal. 20(2), 1263–1304 (2025).

Dreiseitl, S. & Ohno-Machado, L. Logistic regression and artificial neural network classification models: A methodology review. J. Biomed. Inform. 35(5–6), 352–359 (2002).

VanderWeele, T. J. & Knol, M. J. A tutorial on interaction. Epidemiol. Methods 3(1), 33–72 (2014).

Fryer, D., Strümke, I. & Nguyen, H. Shapley values for feature selection: The good, the bad, and the axioms. IEEE Access 9, 144352–144360 (2021).

Selvaraju, R.R., et al. Grad-cam: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision. (2017).

Chattopadhay, A., et al. Grad-cam++: Generalized gradient-based visual explanations for deep convolutional networks. In 2018 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV). IEEE (2018).

Zhou, B., et al. Learning deep features for discriminative localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. (2016).

Singh, D. & Singh, B. Investigating the impact of data normalization on classification performance. Appl. Soft Comput. 97, 105524 (2020).

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

The National Science and Technology Council supports this work. Grant ID: 112–2118-M-A49-003.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HYY conducted the analysis and prepared the first draft, partial revision questions. YHC edits the manuscript and provides critical comments. HMC provided Funding support for HYY, jointly supervised the project. CYG proposed the research methodology, supervised the project, finalized the manuscript, revisions, and letters. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Our study did not require ethical board approval because It is a computer simulation study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable. It is a computer simulation study.

Consent to participate

Not applicable. It is a computer simulation study with open-source datasets.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this article’s subject matter or materials.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, HY., Chen, YH., Cheng, HM. et al. Pseudo datasets estimate feature attribution in artificial neural networks. Sci Rep 15, 45157 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28840-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28840-7