Abstract

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is a neurological disorder affecting the functioning of central nervous system. It can lead to poor coordination, seizures and paralysis. Neuroimaging modalities such as Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Positron Emission Tomography (PET) can provide important information about AD and will continue to do so in the future as far as clinical manifestations of this disease are concerned. Information from neuroimaging modalities can be combined with deep learning (DL) approaches to diagnose AD in its early stages, reducing the burden on neuropathologists. In this study, we compared the performances of six data augmentation methods —ellipsoidal averaging, Laplacian of Gaussian (LoG), local Laplacian, local contrast, Prewitt-edge emphasising, and unsharp masking —on AD diagnosis. We studied three binary problems: AD-Normal Control (NC), AD-Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), and MCI-NC, and one multiclass (3-classes) classification problem: AD-MCI-NC. We also combined these data augmentation methods and tried a strided convolution architecture for these tasks. We find that Prewitt-edge emphasising augmentation yields the best performance for AD-MCI-NC and AD-MCI classification tasks. In contrast, local Laplacian augmentation performs the best for the MCI-NC classification task, while LoG augmentation yields the best results for the AD-NC classification task.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is a neuropsychological disorder that is associated with the loss of mental faculties especially in the elderly. It is an irreversible, progressive and most common form of dementia. As projected by Alzheimer’s Disease International, it’s numbers will rise to 152 million people in 2050 and estimated annual cost to $2 trillion in 2030. Early diagnosis of AD can help delay its progression1. These techniques offer the opportunity to diagnose AD early by detecting the changes in the brain in-vivo2. Machine Learning (ML) techniques have been successfully applied for the early detection of AD and can aid a neuropathologist in making a cost-effective decision. These techniques can remove inter- and intra-rater differences among observers and can be a time-efficient module to provide a scalable compensation for multiple diagnoses3.

Deep Learning (DL), a subtype of ML, allows feature extraction through non-linear transformations in an end-to-end fashion. It works by reducing the difference between ideal and current output through a loss function using backpropagation algorithm. The extracted features include shapes such as dots, lines, and object edges4. It can reduce overfitting and achieve generalization whilst providing more information from a reduced set of samples. These techniques can effectively diversify the datasets, increasing the performance of DL architectures on the underlying task.

Hadeer A. Helaly et al.1 proposed a deep learning model, based on a pre-trained VGG-19 model, named E2AD2C for multiclass classification between AD, early Mild Cognitive Impairment (EMCI), late MCI and Normal Control (NC) classes achieving an accuracy of 97%. Carol Y. Cheung et al.5 used retinal images to train a binary classifier based on the EfficientNet-b2 network, achieving an accuracy of 83.6%. Janani Venugopalan et al.6 proposed an approach that uses stacked denoising auto-encoders and 3D Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) to extract features from genetic, clinical, and imaging data for multiclass classification into NC, MCI, and AD classes, achieving an accuracy of 79%. Shangran Qiu et al.7 report a DL framework to identify NC, MCI, AD, and non-AD dementias utilising imaging and non-imaging datasets, achieving an accuracy of 55.8%. Sheng Liu et al.8 developed an approach to utilize 3D-CNNs achieving area under the curve (AUC) of 85.12% for NC identification, 62.45% for MCI identification, and 89.21% for AD identification tasks. Marwa El-Geneedy et al.9 proposed a DL pipeline utilising MRI images for a multiclass classification task between NC, very mild dementia, mild dementia, and moderate dementia classes, achieving an accuracy of 99.68%. Andrea Loddo et al.10 proposed an ensemble approach for binary (AD/non-AD) and multiclass Classification tasks achieved accuracies of 98.51% and 98.67% for both cases, respectively, using MRI and functional MRI image features.

Suriya Murugan et al.11 proposed a DL architecture utilising 2D-CNN layers and MRI images for multiclass classification between very mild demented, mild demented, moderate demented, and non-demented subjects, achieving an accuracy of 95.23% on this task. Serkan Savaş12 compared the performances of 29 pre-trained models and found the accuracy of EfficientNetB0 model to be the highest at 92.98%. F M Javed Mehedi Shamrat et al.13 proposed a fine-tuned CNN architecture. They compared the performances of VGG16, MobileNetV2, AlexNet, ResNet50 and InceptionV3 architectures and found the performance of InceptionV3 architecture to be the best. They further modified the InceptionV3 architecture achieving an accuracy of 98.67% in identifying all five stages of AD and the NC class. Prasanalakshmi Balaji et al.14 proposed a hybrid DL approach combining CNN and Long Short Term Memory (LSTM) architectures and utilizing information from MRI and PET scans to achieve an accuracy of 98.5% in classifying cognitively normal controls from early MCI subjects. Pan et al. confirmed the recent finding that advanced, deep visual representation models are able to reproduce complex stimuli, indicating that highly flexible AI architectures can truly capture faint and fine details in biomedical imaging. This type of representation learning could potentially be applied to enhance the accuracy of FDG-PET-based diagnosis of Alzheimer’s15.

Zhu16 developed an AI classification model to identify memory impairment, which showed that AI was a versatile tool for identification of cognitive deficits. These same strategies could be useful in the development of PET-based diagnostic models for Alzheimer’s disease. Yin et al.17 presented an innovative feature fusion and temporal modelling framework for biomedical signal-based emotion recognition problems, proving the effectiveness of hybrid deep learning architectures. These fusion approaches are extendable to the improvement of tracer imaging analysis for early Alzheimer’s detection using PET signals.

Data augmentation is a less targeted area in the early diagnosis of AD using DL approaches. There is a need for further exploration of data augmentation techniques for small size datasets. Due to scarcity of samples in AD datasets because of high costs, data augmentation is of great interest in learning the features during training of DL architectures18.

In this article, we carried out experiments using PET scans. Six data augmentation methods are chosen: ellipsoidal averaging, Laplacian of Gaussian (LoG), local Laplacian, local contrast, Prewitt-edge emphasizing, and unsharp masking. We selected these techniques to improve the robustness of DL architectures, extract better features, reduce noise, focus on relevant structures, and enhance sensitivity to detect small variations in brain activity and structure.

This article is organised as follows: Dataset Description, which includes patient inclusion criteria and socioeconomic information; and the Methods section, which outlines all data augmentation strategies and deep learning architectures used for classification tasks. Results: Shows the result of an experiment and reflects possible interpretation in the Discussion segment. The conclusion section summarizes the main findings of the study.

Dataset description

Demographics of the subjects are summarized in Table 1. Values are expressed as mean (min-max), obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database website.

Methods

Data sources The data used in this study were downloaded from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database. ADNI is a long-term, multicenter study designed to develop and test methods for the early detection of Alzheimer’s disease. Established in 2004, the initiative compiles standardized, high-quality data from subjects at various research sites—cognitively normal individuals, those with MCI and patients diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

Data augmentation techniques

We chose six methods: ellipsoidal averaging, LoG, local Laplacian, local contrast, Prewitt- edge emphasizing, and unsharp masking; and studied their impact on the early diagnosis of AD using 3D PET scans. We considered only positive values. A description of these methods is provided next.

Ellipsoidal averaging

The 3D ellipsoidal averaging filter is a high-quality filter commonly utilized to enhance the smoothness of volumes. It relies on the insight that the affine mapping establishes a skewed 2D system around a source pixel. An ellipsoidal projection is subsequently calculated around this source pixel, which is utilized to filter the source image using a Gaussian whose inverse covariance matrix is represented by this ellipsoid. We used ‘fspecial3’ and ‘imfilter’ functions in MATLAB to implement the 3D ellipsoidal averaging filter.

Laplacian of Gaussian

The 3D LoG filter is commonly used to detect edges in volumes. It works by calculating the second derivative in the spatial domain. The LoG response can be zero, positive, or negative depending on its distance from the edge. The 2D LoG function that is centered on zero and with Gaussian standard deviation has the following mathematical form:

We used ‘fspecial3’ and ‘imfilter’ functions in MATLAB to implement the 3D LoG filter.

Local laplacian

Local Laplacian is a type of filter that uses the amplitude of edges and smoothing of details with a Laplacian to control the dynamic range of an image. It can be deployed to increase the local contrast of a coloured image, to perform edge-aware noise reduction, as well as to smooth image details. We used ‘locallapfilt’ function in MATLAB to implement 3D Local Laplacian filter. We set to 0.4, and to 0.5.

Local contrast

Local contrast can be used to increase or decrease the local contrast of an image. It works by controlling the desired smoothing as well as intensity of strong edges. We used ‘localcontrast’ function in MATLAB to implement 3D Local contrast filter. We set ‘edgeThreshold’ to 0.4, and ‘amount’ to 0.5.

Prewitt-edge emphasizing

The Prewitt operator can be used to detect edges in both horizontal and vertical directions in an image using first-order derivatives. It is a separable filter because it’s kernels can be decomposed by averaging and differentiation operations. We used ‘fspecial3’ and ‘imfilter’ functions in MATLAB to implement the 3D Prewitt-edge emphasizing filter.

Unsharp masking

Sharpness is the difference in color between two or more colors. A strong transition from black to white is achieved quickly. It appears hazy as black gradually changes to grey and then to white. An image is sharpened by removing a blurry (unsharp) version of itself. This method is known as unsharp masking. We used ‘imsharpen’ function in MATLAB to implement the 3D unsharp masking operation.

Deep learning architectures

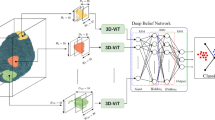

Figure 1 shows the generic architecture that we used throughout experiments. We input a 3D volume of size 79 × 95 × 69, normalised using a zero-centre normalisation procedure that subtracts the mean calculated from each channel.

In addition, we also performed experiments using the strided convolution architecture given in Fig. 2, without augmentation for this task. We used 10 filters in the convolutional 3D layer.

A convolution layer is then used to extract the features in the input volume. We used a small kernel of size 3 × 3 × 3 to combine local features effectively. To further optimize the network, we apply weight and bias L2 regularization in order to reduce overfitting. A batch normalization layer is then used to mitigate internal covariance shift by normalizing the observations across channels independently. After that, we used Exponential Linear Unit (ELU) activation layer which the following equation can describe:

After that, we used the max-pooling operation to reduce the size of the feature maps by selecting the maximum value in a neighbourhood of pixels. We ensure that pooling regions do not overlap by keeping stride equal to the corresponding pool size of 2 in all dimensions.

We then applied fully connected or dense layers to capture global patterns followed by a softmax layer that works by applying exponential function to each element of the input and further normalizing these values according to the following equation:

Finally, we applied classification layer that works by computing the cross-entropy loss for classification given by the following equation:

In Eq. 4, ‘N’ is the number of samples, ‘K’ is the number of classes, wi is the weight for class ‘i’, ‘tni’ indicates that sample ‘n’ belongs to class ‘i’, while ‘yni’ is the output for sample ‘n’ for class ‘i’.

We used 100 neurons in Fully-Connected (FC) layer 1, 30 neurons in FC layer 2 and two (binary classification) or three (multiclass classification) neurons in FC layer 3. We shuffle the training set after every epoch during training. We used ‘Adam’ as an optimiser, set the initial learning rate to 0.001, and trained the model for 50 epochs with a mini-batch size of 2. We also periodically dropped the learning rate after every 10 epochs by multiplying it by a factor of 0.1.

AD-NC binary classification tasks

For the AD-NC classification task without augmentation, we employed 10 filters in the convolutional 3D layer. For tasks involving augmentation, such as unsharp masking, Prewitt-edge emphasising, local Laplacian, local contrast, LoG, and ellipsoidal averaging, we utilised 15 filters in the convolutional 3D layer. We also performed experiments combining Prewitt-edge emphasizing augmentation and LoG augmentation schemes for this task. We used 15 filters in the convolutional 3D layer.

AD-MCI binary classification tasks

We used 10 filters in the convolutional 3D layer while for tasks involving unsharp masking augmentation, Prewitt- edge emphasizing augmentation, local Laplacian augmentation, local contrast.

We employed augmentation methods, including LoG augmentation and ellipsoidal averaging augmentation, and utilised 15 filters in the convolutional 3D layer. We also performed experiments combining Prewitt-edge emphasizing augmentation and LoG augmentation schemes for this task. We used 15 filters in the convolutional 3D layer.

MCI-NC binary classification tasks

We employed 10 filters in the convolutional 3D layer. For tasks involving augmentation, such as unsharp masking, Prewitt-edge emphasising, local Laplacian, local contrast, LoG, and ellipsoidal averaging, we utilised 15 filters in the convolutional 3D layer. We also performed experiments combining Prewitt-edge emphasizing augmentation and LoG augmentation schemes for this task. We used 15 filters in the convolutional 3D layer. In addition, we also performed experiments combining LoG, Local Laplacian, and Prewitt- edge emphasizing augmentation techniques for this task. We used 20 filters in the convolutional 3D layer.

AD-MCI-NC multiclass classification tasks

We employed 10 filters in the convolutional 3D layer. For tasks involving augmentation, such as unsharp masking, Prewitt-edge emphasising, local Laplacian, local contrast, LoG, and ellipsoidal averaging, we utilised 15 filters in the convolutional 3D layer. We also performed experiments combining Prewitt-edge emphasizing augmentation and LoG augmentation schemes for this task. We used 15 filters in the convolutional 3D layer.

Results

We deployed 5-fold Cross-Validation (CV) approach in our experiments. We used sensitivity (SEN), specificity (SPEC), F-measure, precision and balanced accuracy as performance metrics for the methods in Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5. In Table 5, we defined these metrics for each class.

For binary classification tasks, their definitions are given as follows:

For multiclass classification, true positive (TP), true negative (TN), false positive (FP) and false negative (FN) are defined with the help of confusion matrix given in Fig. 3 as follows:

Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5 present the results for this study.

Table 3 shows the performance metrics of different data augmentation techniques on a classification model.

Table 4 presents the results for the MCI-NC binary classification task, evaluating various augmentation techniques.

In Table 5, we present the results in the following format: AD, MCI, NC. For example, for no augmentation method, SEN for AD class is 0.7340, SEN for MCI class is 0.3711, while SEN for NC class is 0.6275.

Discussion

In Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5, it can be seen that augmentation may help in achieving better outcomes. The performance of the Prewitt-edge emphasising augmentation scheme for AD-MCI and AD-MCI-NC classification tasks is quite strong. Similarly, LoG augmentation shows excellent performance for AD-MCI and AD-NC classification tasks, whereas Local Laplacian augmentation performs well for the MCI-NC classification task. Furthermore, it can be noted that combining augmentation techniques may not result in better performances. The modified architecture, which uses strided convolution instead of maxpooling layers, does not perform as well as augmentation techniques without strided convolution. For MCI-NC classification task, we found the performance of local Laplacian augmentation to be the best. For both AD-MCI-NC and AD-MCI classification tasks, we found the performance of Prewitt-edge emphasizing augmentation to be the best. Finally, for AD-NC classification task, we found the performance of LoG augmentation to be the best. The differences in performance can be tied to the specific nature of the changes in brain structures at different stages of AD. Local Laplacian augmentation enhances both the edges and fine details in a PET scan, allowing the DL model to focus on regional variations in brain structures that are indicative of disease progression, especially occurring in the MCI stage. LoG augmentation emphasises rapid intensity changes, such as boundaries between different brain regions, making it easy for DL models to detect early changes in AD, especially in critical areas like the hippocampus. Thus, it could be a suitable candidate for NC to AD related progression detection. Prewitt-edge emphasising augmentation highlights transitions between different brain structures, revealing early signs of atrophy. AD typically affects specific brain regions like the hippocampus, and edge emphasizing ensures that these regions can be accurately detected and classified by DL models.

From these results, it is clear that the methods that utilized information present in the derivatives are the better performing ones. The Prewitt operator is a discrete differentiation operator that gives the direction of largest possible increase from high to low intensity. At regions of constant image intensity, it gives a zero vector. LoG can be used for blob detection. It uses a Gaussian kernel to return positive responses for dark blobs and negative responses for bright ones. It’s responses are covariant with affine transformations in the image domain. Laplacian of an image utilizes information in the second derivatives. It crosses zero at edge. LoG combines Gaussian filtering with Laplacian for the detection of an edge. This approach has the advantage of isolating noise points and small structures, particularly those in the brain, which can be filtered out effectively. This is especially true when the image contrast across the edge is combined with the slope of the zero crossing.

While traditional approaches for feature description may require the expertise of a designer, DL systems are end-to-end systems that extract features in the absence of such expertise. We deployed Convolutional Neural Networks in the present study because of their ability to partition the feature space using nonlinear boundaries for classes. They can learn classification boundaries in their feature spaces despite their limitations given a carefully selected training set. It is recognized that neuropsychiatric symptoms such as agitation and aggression, have a strong link with cognitive impairment connected with AD. Changes in amygdala, frontal cortex, hippocampus, occipital cortex and other brain areas trigger neuroinflammation and neuronal dysfunction during early stages of AD and can be captured effectively by a PET scan19. DL models can be deployed to represent these changes effectively by processing PET scans which can contribute to the identification of vital factors leading the way for personalized treatments.

Table 6 provides a comparison of the proposed method to existing techniques available in the literature for different Alzheimer’s disease classifications using PET data. Our results demonstrate that our method is consistently better than previous approaches in different classification scenarios, obtaining the best accuracy for AD–NC, AD–MCI, MCI–NC and AD–MCI-NS task.

As seen in Table 6, our LoG- based augmentation approach produces better results for AD-NC binary classification task in comparison to box filtering approach which could be due to the fact that LoG identify changes in image intensity effectively preserving edges while reducing noise sensitivity while box filtering blurs an image by averaging out the neighborhood pixels defined by the kernel.

For the AD-MCI binary classification task, our approach, which emphasises augmentation based on Prewitt-edge features, outperforms the architecture-based approach in Ahsan et al.21. Combined with the fact that the architecture in the present study has not employed dropout before softmax, which essentially rules out the possibility of dropping such useful features, and the powerful horizontal and vertical edge detection by Prewitt-edge emphasising filtering method, better performance in the recognition of continuum defined by AD and MCI can be achieved.

For the MCI-NC binary classification task, our approach based on Local Laplacian augmentation has outperformed other approaches, especially those based on median filtering augmentation. This could be due to the fact that our approach uses the Laplacian pyramid effectively, decomposing an image into different frequency bands and locally enhancing details near each pixel. In contrast, the median filtering approach has the potential to blur fine details and reduce effectiveness against Gaussian noise, thus effectively reducing accuracy in this task. This superiority may be attributed to the blurring effect of Gaussian filtering, which reduces high-frequency components and fine details, potentially hindering the performance of deep learning architectures in this context.

New AI-based healthcare research has offered methodologies that can be applied to improve the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease with PET. Pan et al.23 found that combining decision-level fusion across multiple data domains can greatly enhance the classification accuracy of cognitive state, which may provide new guidance for incorporating multimodal PET biomarkers. Luan et al. For the detection of early-stage disease, PET scan images have suboptimal spatial resolution that can be improved with the recently emerging deep learning method for super-resolution imaging by Zhu et al.24. Zhan et al. Based on their results25, Taskar and his team recommended that the choice of the algorithm design can highly affect the precision in brain analysis as well, suggesting to use computational techniques optimized for PET data processing. Li et al. Using machine learning on physiological data for the diagnosis of age-related diseases, AI models show their promise in non-invasive assessments as well in neurodegenerative conditions26. Wang et al.27 emphasised the convergence of novel therapy with validated clinical treatment strategies, and integrations into multi-disciplinary team approaches as advancing peri-diagnosis AI-enhanced PET reading would greatly improve early diagnostic endeavour and patient guidance.

Conclusion

This study compared and contrasted six data augmentation methods: ellipsoidal averaging, LoG, local Laplacian, local contrast, Prewitt-edge emphasizing, and unsharp masking. We used PET neuroimaging modality scans from ADNI database for the early diagnosis of AD. Furthermore, we considered three binary classification problems: AD-NC, AD-MCI, and MCI-NC, as well as one multiclass classification problem, AD-MCI-NC. We also combined data augmentation methods and tried a modified strided convolution architecture for all these tasks. We found the performances of Prewitt-edge emphasizing, LoG and local Laplacian augmentation methods to be the best. In the future, we plan to study the impact of other data augmentation methods, such as Sobel-edge emphasising, superpixel over-segmentation, numerical gradient, directional gradient, GANs, etc., on the early diagnosis of AD using novel DL architectures.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database. Due to restrictions outlined in the ADNI Data Use Agreement, the datasets are not publicly available but can be accessed by qualified researchers upon request through the ADNI website: https://adni.loni.usc.edu/data-samples/access-data/.

References

Helaly, H. A., Badawy, M. & Haikal, A. Y. Deep learning approach for early detection of alzheimer’s disease. Cogn. Comput. 14, 1711–1727. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12559-021-09946-2 (2022).

Lisa Mosconi, M. et al. Early detection of alzheimer’s disease using neuroimaging, experimental Gerontology, 42, issues 1–2, 2007, Pages 129–138, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2006.05.016

Shunsuke Koga, A., Ikeda, D. W. & Dickson Deep learning-based model for diagnosing alzheimer’s disease and tauopathies. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. https://doi.org/10.1111/nan.12759 (2021).

Zhou, Q., Wang, J., Yu, X., Wang, S. & Zhang, Y. A survey of deep learning for alzheimer’s disease. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 5, 611–668. https://doi.org/10.3390/make5020035 (2023).

Carol, Y. et al. A deep learning model for detection of Alzheimer’s disease based on retinal photographs: a retrospective, multicentre case-control study, The Lancet, Volume 4, Issue 11, e806-e815, 2022. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/landig/article/PIIS2589-7500(22)00169- 8/fulltext?sm_guid = MTYzNzUwfDExMzQwMTI1fC0xfGRjYW1wYmVsbEBicmlnaHRmb2 N1cy5vcmd8MTAyNzk4OHx8MHwwfDU1MDY4NjE2fDgzN3wwfDB8fDExNDM3OA2.

Janani Venugopalan, L., Tong, H. R. H., May, D. & Wan Multimodal deep learning models for early detection of Alzheimer’s disease stage, Scientific Reports volume 11, Article number: 3254 (2021).

Qiu, S. et al. Multimodal deep learning for alzheimer’s disease dementia assessment. Nat. Commun. 13, 3404. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467 (2022).

Liu, S. et al. Generalizable deep learning model for early alzheimer’s disease detection from structural MRIs. Sci. Rep. 12, 17106. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-20674-x (2022).

Marwa, E. L. G. & Moustafa, H. E. D. Fahmi Khalifa et al. An MRI-based deep learning approach for accurate detection of alzheimer’s disease. Alexandria Eng. J. 63, 211–221. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1110016822005191 (2023).

Loddo, A., Ruberto, C. D. & Sara Buttau, & Deep learning based pipelines for Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis: A comparative study and a novel deep-ensemble method. Comput. Biol. Med. 141, 105032. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S001048252100826X (2022).

Murugan, S. et al. DEMNET: A deep learning model for early diagnosis of alzheimer diseases and dementia from MR images. IEEE Access. 9, 90319–90329. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3090474 (2021).

Savaş, S. Detecting the stages of alzheimer’s disease with pre-trained deep learning architectures. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 47, 2201–2218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-021-06131-3 (2022).

Shamrat, F. M. J. M. et al. AlzheimerNet: an effective deep learning based proposition for alzheimer’s disease stages classification from functional brain changes in magnetic resonance images. IEEE Access. 11, 16376–16395. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3244952 (2023). https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/10043854

Balaji,; Chaurasia, M. A., Bilfaqih, S. M., Muniasamy, A. & Alsid, L. E. G. Hybridized deep learning approach for detecting alzheimer’s disease. Biomedicines 11, 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11010149 (2023).

Pan, H., Li, Z., Fu, Y., Qin, X. & Hu, J. Reconstructing visual stimulus representation from EEG signals based on deep visual representation model. IEEE Trans. Human-Machine Syst. 54 (6), 711–722. https://doi.org/10.1109/THMS.2024.3407875 (2024).

Zhu Computational intelligence-based classification system for the diagnosis of memory impairment in psychoactive substance users. J. Cloud Comput. 13 (1), 119. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13677-024-00675-z (2024).

Kaitlin, M. et al. Amidst an amygdala renaissance in Alzheimer’s disease, March, 147, Issue 3, Pages 816–829, (2024). https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awad411

Jia, H. et al. Assessing the potential of data augmentation in EEG functional connectivity for early detection of alzheimer’s disease. Cogn. Comput. 16, 229–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12559-023-10188-7 (2024).

Naomi, K. et al. June. Clinicopathologic heterogeneity and glial activation patterns in alzheimer disease, JAMA Neurology, Volume 81, Number 6 (2024).

Tufail, A. B. et al. Classification of initial stages of alzheimer’s disease through pet neuroimaging modality and deep learning: quantifying the impact of image filtering approaches. Mathematics 9, 3101. https://doi.org/10.3390/math9233101 (2021).

Tufail, A. B. et al. On disharmony in batch normalization and dropout methods for early categorization of alzheimer’s disease. Sustainability 14, 14695. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214695 (2022).

Tufail, A. B. et al. Early-stage alzheimer’s disease categorization using PET neuroimaging modality and convolutional neural networks in the 2d and 3d domains. Sensors 22, 4609. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22124609 (2022).

Pan, H., Tong, S., Song, H. & Chu, X. A miner mental state evaluation scheme with decision level fusion based on multidomain Eeg information. IEEE Trans. Human-Machine Syst. 55 (2), 289–299. https://doi.org/10.1109/THMS.2025.3538162 (2025).

Luan, S., Yu, X., Lei, S., Ma, C., Wang, X., Xue, X., … Zhu, B. (2023). Deep learning for fast super-resolution ultrasound microvessel imaging. Physics in Medicine & Biology,68(24), 245023. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6560/ad0a5a.

Zhan, X. et al. Differences between two maximal principal strain rate calculation schemes in traumatic brain analysis with in-vivo and in-silico datasets. J. Biomech. 179, 112456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2024.112456 (2025).

Li, N. et al. Exploration of a machine learning approach for diagnosing sarcopenia among Chinese community-dwelling older adults using sEMG-based data. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 21 (1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-024-01369-y (2024).

Wang, L., Ren, N., Tang, Z., Wang, R. & He, Z. Integration of continuous lumbar drainage and third-generation EGFR-TKI in managing leptomeningeal metastasis-induced life-threatening intracranial hypertension: a case report. Front. Oncol. 15, 1581754. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2025.1581754 (2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A. and A.B.T. conceptualized the study and designed the methodology. T.A. and A.S.K. contributed to data acquisition and preprocessing. M.S. and A.M.I. performed the data augmentation experiments and statistical analyses. M.A. and A.B.T. implemented the deep learning models and conducted comparative evaluations. A.S.K. and M.S. prepared Figs. 1, 2 and 3. M.A. and A.B.T. wrote the main manuscript text, while T.A., A.S.K., and A.M.I. provided critical revisions. T.M.G. performed the manuscript revisions, proofreading, and contributed to the analysis. All authors reviewed, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Athar, M., Tufail, A.B., Alyas, T. et al. Early diagnosis of alzheimer’s disease using PET imaging and deep learning with comparative data augmentation techniques. Sci Rep 16, 660 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28866-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28866-x