Abstract

Pain therapies are prescribed to a significant proportion of the population but also associated with adverse drug reactions (ADRs). The prescription of pain therapies requires careful consideration of their safety profiles in the context of patient-specific characteristics, such as age-specific vulnerabilities, which are, however, still understudied so far. The aim of this study was to describe ADRs reported for drugs used in pain therapies and investigate age disparities. We conducted a descriptive comparative analysis of individual case safety reports (ICSRs) of drugs used in pain therapies from the global ADR database VigiBase between September 29, 1991, and December 31, 2022, from Switzerland. Comparisons were drawn between younger and older adults (18–74 years vs. 75 + years). Disproportionality (reporting odds ratio, ROR) of serious ADRs was assessed between age groups. A total of 17,228 ICSRs were analysed (58% female, 24% age 75 +). Across both age groups, the most frequently reported ADRs were related to the nervous system (23%), gastrointestinal system (20%), and general health and administration site conditions (20%). Serious ADRs were more common in the older population compared to younger adults (69% vs. 54%) with an ROR of 1.9. Fatal ADRs were also disproportionally higher in older adults (ROR 1.9). Hemorrhage was the most frequent fatal reaction. Commonly used pain therapies can lead to ADRs with a pronounced impact, especially in older adults. A deeper understanding of the safety profiles of these drugs should aid healthcare professionals in making more informed, safer treatment decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pain medication involves a variety of different pharmacological classes potentially added to non-pharmacological measures. Common pain medications include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and opioids for a variety of pain types, often complemented by adjuvant pain medication, antimigraine drugs or other specific products containing paracetamol and metamizole. Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) to pain medications range from common – usually less severe effects – to infrequent potentially serious outcomes. The potential of harm was recently elucidated especially for opioids in Switzerland1,2. However, non-opioids also pose serious and potentially life-threatening risks, including cardiovascular events, hepatic and renal disorders, gastrointestinal perforation, or blood disorders, such as agranulocytosis.

Pharmacological pain treatment considers factors such as the type and degree of pain, patient characteristics, comorbidities, concomitant medications, and patient preferences. The decision for a drug class and specific drugs within the classes involves an individual benefit-risk analysis to balance analgesic efficacy against potential adverse reactions and harms. This requires a deep and nuanced understanding of the safety profiles of pain medications in the context of patient-specific characteristics, particularly when treating populations who are more vulnerable to ADRs, such as older adults.

Pain medication is widely prescribed in Switzerland, with recent reports indicating an increase in their usage3,4,5. Even among young adults, at 20 years old, the prevalence of paracetamol use was at 23%6 and opioid analgesics had been used by 2.6%7.

This nationwide analysis aimed to elucidate ADRs associated with pain therapies in Switzerland and compared the seriousness and reaction types occurring in younger and older adults. By examining a comprehensive set of spontaneous reports of ADRs, this study aims to describe specific reactions of Swiss pain therapies and to identify potential age-related disparities in ADR distribution using Reporting Odds Ratios (RORs).

Methods

Study design

This is a descriptive analysis of pharmacovigilance data. We analysed individual case safety reports (ICSRs) of ADRs of pain medications reported in Switzerland between September 29, 1991, and December 31, 2022. Disproportionality between the reporting of serious ADRs in younger vs older adults was assessed using RORs.

Data source and variables

This study used data from the WHO pharmacovigilance database VigiBase8. VigiBase is a global database of ADRs. ADRs are reported spontaneously to national pharmacovigilance centres or drug manufacturers by healthcare professionals and non-healthcare professionals. The ADRs are then recorded as ICSRs including patient characteristics, the suspect drug and the experienced reaction. Medications in WHODrug are classified using the ATC system and clustered into Standardised Drug Groupings (SDG), to allow for grouping of medications with one or more properties in common, based on chemical structure, pharmacological effect or metabolic pathway9. Reactions are reported as MedDRA preferred terms (PTs). PTs are distinct descriptors for symptoms, diagnoses, or investigations. All PTs are categorised into overarching MedDRA System Organ Classes (SOC), which group the PTs by aetiology, manifestation site or purpose10. Each ICSR can report on multiple drugs and reactions and can therefore be categorised into multiple SDGs and SOCs.

Selection of ICSRs

We included all reports from Switzerland between September 29, 1991 (date of the first report on drugs used in pain therapies in Vigibase), and December 31, 2022. All reports had to include at least one suspect drug used in pain therapies in accordance with the WHODrug11 SDG12. This SDG contains the subgroups adjuvant pain medications, analgesia producing opioids, antimigraine preparations, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs used in pain therapies, and other analgesic drugs used in pain therapies. A complete list of the substances included in the SDG is not publicly available. Reports with missing age or sex, age under 18 years, and pregnancy cases were excluded. Duplicate reports were identified using the vigiMatch™ algorithm, a statistical method for identifying multiple reports of the same case13.

Statistical analysis

ICSRs were analysed descriptively. ICSRs were stratified according to individuals’ age into “older adults” (75 years and older), and “younger adults” (18 to 74 years). We summarized ICSR characteristics, including sex, reporter, seriousness and seriousness criteria, and fatality. Seriousness and fatality were determined using the standardized ratings provided by VigiBase, which are assigned by the Uppsala Monitoring Centre according to ICH E2A guidelines14. This ensured that all reactions meeting serious or fatal criteria were captured in the analysis. Categorical variables were described in absolute numbers and percentage of all ICSRs. Continuous variables (age) were described with a mean and standard deviation, and a median and minimum and maximum value.

To determine the most relevant drugs and reactions, in each SDG subgroup, the top drugs for most frequently reported “suspect” drugs for the ADRs were analysed by age group: This included the 10 most frequently reported drugs for the subgroups of “analgesia producing opioids”, and “NSAIDs”, “adjuvant pain medications”, “antimigraine preparations”, for substances used in pain therapies.

The reported reactions of the top reported drugs per subgroup were examined based on the MedDRA PTs. To optimize the drug-reaction pairs, the MedDRA PTs were assigned a MedDRA Higher Level Term (HLT). In MedDRA each PT can be linked to multiple HLTs (1 to n). For this analysis, we assigned a single HLT for each preferred term (1 to 1) as follows: (1) The frequency for each HLT occurrence was calculated across the MedDRA database. (2) For PTs associated with multiple HLTs, the HLT with the highest occurrence was selected, and the others were discarded. The steps were repeated three times, ensuring that each PT was consistently associated with HLTs of equal frequency. In cases where multiple HLTs remained, the first HLT in alphabetical order was chosen to establish a one-to-one PT-HLT relationship. The procedure is visualized in Supplement Fig. 1.

The drug-reaction pairs were quantified for selected drugs in specific SDG, focusing on drugs frequently reported and those particularly relevant to Switzerland based on clinical experience. For the SDG “NSAIDs” the substances diclofenac, ibuprofen, mefenamic acid, and metamizole were selected. For “analgesia producing opioids” we chose morphine, oxycodone, and tramadol and for “other analgesia producing drugs” the reactions of gabapentin, pregabalin, and paracetamol were analysed.

The ROR for seriousness and seriousness criteria in older vs. younger adults was calculated as ROR = (nolder, serious*nyounger, non-serious)/(nyounger, serious*nolder, non-serious) with the respective confidence interval. The formula is visualized in the Supplement.

All analyses were conducted with R15 (version 4.2.3) and RStudio (version 2022.07.2). The flowchart was created with the R package flowchart16. The manuscript was prepared in accordance with the STROBE guideline and the READUS-PV guideline and checklist17,18.

Meeting presentations

This study was presented at the Swiss Society of General Internal Medicine’s Spring Congress; May 29–31, 2024; Basel, Switzerland; and at the International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology’s Annual Meeting; August 24–28, 2024; Berlin, Germany.

Results

Report characteristics

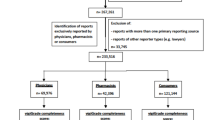

After removing duplicates (n = 1,243), cases with unknown age (n = 5,066) or sex (n = 182), age < 18 (n = 1,004), and pregnancy cases (n = 638), a total of 17,228 ICSRs from Switzerland with pain medications were analysed (Fig. 1).

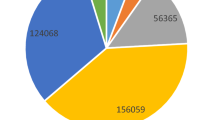

Table 1 summarizes the report characteristics. Overall, 58.4% were female, mean age was 58 years and 23.5% were 75 years or older. Of the 17,228 ICSRs, 4,731 (27.5%) involved on at least one SDG adjuvant pain medication, 3,919 (22.7%) included an antimigraine preparation, 5,784 (33.6%) reported an NSAID, 2,123 (12.3%) included an analgesic opioid, and 3,013 (17.5%) involved at least one drug from the SDG of “other drugs used in pain therapies”.

System organ classes (SOC)

Overall, the three most frequently affected SOCs were nervous system disorders (23.4%), gastrointestinal disorders (19.7%), and general disorders and administration site conditions (19.5%) with at least one reaction in the respective SOC (Supplement Table 3). In older adults, gastrointestinal disorders (23.4%), nervous system disorders (21.9%), and blood and lymphatic system disorders (16.2%) were most common. In younger adults, nervous system disorders (23.9%), general disorders and administration site conditions (20.6%), and gastrointestinal disorders (18.3%) were most frequent (see Supplement Table 3).

Figure 2 illustrates the top 8 most affected SOCs, stratified by age group and drug classes of NSAIDs and opioids, as clearly defined subgroups within the SDG category. For opioids, nervous system disorders (35.0%) were the most reported adverse reactions, while for NSAIDs gastrointestinal (29.3%) and blood and lymphatic disorders (23.5%) were predominant.

Drugs and reactions

The most frequently reported suspect drugs overall were acetylsalicylic acid, paracetamol, venlafaxine, diclofenac, and metamizole. The top reported drugs for each SDG subgroup are detailed in Supplement Table 2.

Table 2 presents drug-reaction pairs, i.e., the top reported drugs per SDG subcategory associated with the reactions coded as MedDRA HLTs, stratified by age group. The MedDRA PTs categorized in each HLT are listed in Supplement Table 4.

In younger and older adults, renal failure and impairments were frequently reported with NSAIDs including diclofenac, ibuprofen, and mefenamic acid. In younger adults, allergic conditions, and dermatologic reactions (rashes, eruptions and exanthems) were also common. For older adults, gastrointestinal haemorrhages were the most frequently reported reactions with these drugs. For metamizole, the most common reactions in both age groups were neutropenias, and other cytopenias and anaemias.

For analgesic opioids, such as morphine, oxycodone and tramadol, cortical dysfunctions – such as confusional state, agnosia, aphasia, and apraxia – were among the most frequently reported reactions in both age categories ranging from 2.8 to 8.8% by substance and age (Table 2). Neurological symptoms, including dizziness, respiratory depression, and disorientation, were also common, accounting for 2.8 to 5.0% of all reactions. Other frequently reported reactions included nausea and vomiting, especially in younger adults, as well as dyssomnias. Overdoses (intentional, prescribed, or not specified) were frequently reported in younger adults for morphine (2.8%) and tramadol (3.1%).

For gabapentinoids (gabapentin and pregabalin), frequently reported reactions were primarily neurological, including dyssomnias (2.2–6.7%), neurological signs and symptoms (3.1–5.2%), and cortical dysfunctions (2.2–5.9%). In older adults, “off label use” was the most commonly reported term associated with gabapentin (8.9%). For paracetamol, hepatocellular damage and hepatitis were the most frequently reported reactions in both age groups, comprising 7.8% of reactions in younger and 9.8% in older adults. Among older adults, renal failure and impairment were also frequently reported (2.4%), while in younger adults, poisoning and toxicity (7.5%) and overdoses (3.0%) were prominent with paracetamol.

Serious reactions and death

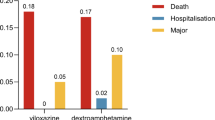

Overall, 57.7% of ICSRs were classified as serious, with a higher incidence in older adults (69.1%) than in younger adults (54.2%). Hospitalization was the most frequently reported seriousness criterion, occurring in 34.6% of all ICSRs (see Table 3).

Serious reactions were reported more frequently in older compared to younger adults, with an ROR of 1.9 (95% CI 1.8–2.0). Similarly, serious reactions resulting in death were more common in older adults compared to younger adults (ROR 1.9; 95% CI 1.6–2.2), as shown in Table 3.

To assess the robustness of our age-related findings, we conducted a post-hoc sensitivity analysis by recalculating the RORs using an alternative age cut-off of 65 years; the resulting RORs showed only minimal deviations from the original stratification, confirming that the observed age-related differences in adverse drug reaction reporting were consistent across both age group definitions (see Supplement Table 5).

The reports for medications and ADRs most frequently associated with death are listed in Supplement Table 6. Acetylsalicylic acid was the most frequently reported suspect drug cases resulting in death, accounting for 33.5% of reports in older and 15.4% in younger adults. The most frequently associated reaction was hemorrhage. Additional drugs and reactions frequently reported in fatal serious cases are detailed in Supplement Table 6.

Discussion

This study provides the first comprehensive analysis of ICSRs of drugs used in pain therapies in Switzerland. Our analysis of 17,228 ICSRs revealed notable age-related differences in the nature and severity of reported reactions to drugs commonly used in pain therapy. Serious reactions were reported twice as often in older adults based on the ROR, with a higher incidence of serious adverse reactions leading to death and hospitalisations compared to younger adults.

The higher frequency of serious adverse events and hospitalisations in older adults is consistent with previous studies19,20. A systematic review by Bouvy et al. found that 5.8 to 28.2% of hospital admissions in older adults were due to ADRs (used not only for pain treatment), compared to 0.8 to 12.8% in the general adult population19. Similarly, in a surveillance study Budnitz et al. reported that older adults (65 years and older) were 2.4 times more likely to experience adverse drug events and 6.8 times more likely to require hospitalization20. Other studies have identified that the drug classes frequently involved in adverse reactions leading to hospitalisation include antithrombotic agents, diuretics, and antimicrobial agents as well as NSAIDs and central nervous system agents, such as opioid analgesics20,21,22,23. These findings underscore the heightened vulnerability of older adults, who often experience polypharmacy and frailty and are exposed to high risk drug classes24. In the present study, the median number of reported drugs per patient was higher in older adults (median 5 [range 1–35]) compared with younger adults (18–74 years; median 3 [range 1–42]). A larger proportion of older adults were reported with four or more medications (67.2% vs. 41.7%), highlighting the greater prevalence of polypharmacy in this group.

In our data, acetylsalicylic acid, ibuprofen, diclofenac, and metamizole were among the most frequently reported drugs, with acetylsalicylic acid being the leading suspect in serious fatal cases, reflecting its bleeding risks as an antithrombotic agent. While physicians might be reluctant to prescribe NSAIDs due to their poor risk–benefit balance in older adults25,26,27, they are often acquired over-the-counter (OTC). Sawyer et al. reported that 41% of community-dwelling older adults used OTC NSAIDs for pain relief28. However, Schmiedl et al. reported that only a small proportion (around 7%) of preventable ADRs leading to hospitalization were related to self-medication, with such cases occurring even less frequently among older adults, suggesting that OTC drugs contribute relatively little to serious, hospitalization-requiring ADRs29. While metamizole and paracetamol are recommended alternatives26,27, they were also frequently implicated in serious fatal reactions in our study. Metamizole has been withdrawn from the market in several countries, such as United Kingdom, France, Sweden, Norway, the United States, Canada, and Australia due to risks of agranulocytosis, and hepatotoxicity30,31. It is, however, frequently used in Switzerland where its use has further increased by 84% from 2014 to 201932,33. The European Medicines Agency and Swissmedic have recently issued recommendations to mitigate the risk of agranulocytosis through early detection. Metamizole product leaflets will subsequently be updated in the EU as well as in Switzerland34,35. Paracetamol-related fatalities, primarily due to overdose and liver injury, were noted in both younger and older adults, with additional risk of bone marrow depression and hypoplastic anaemias in older adults. Although paracetamol-induced liver injury is well-documented, little is known about factors that exacerbate this risk36,37. However, our group has linked increasing poisonings to the introduction of 1000 mg paracetamol tablets in Switzerland38. Lowering prescribed doses of paracetamol could reduce hepatotoxicity risks, while bone marrow depression and cytopenia remain rare but known side effect of paracetamol39.

For analgesic opioids, neurological symptoms were the most common reported adverse reactions in both younger and older adults. Younger adults reported more gastrointestinal symptoms, such as nausea and vomiting, and had higher rates of overdoses and substance use disorders, particularly with oxycodone. Notably, no differences were observed in the adverse reactions between the weak opioid tramadol and the stronger opioids like oxycodone and morphine. These findings align with pharmacovigilance reports from other countries like the Netherlands40 and France41. Particularly, central nervous system effects, such as dizziness or somnolence, are particularly concerning in older adults, as they increase the risk of falls, injuries, and fractures42,43.

For gabapentin, the most frequently reported ADR in younger adults was off-label use. While approved in Switzerland for the treatment of epileptic seizures and neuropathic pain, gabapentin is used off-label for conditions like restless leg syndrome, hot flushes in perimenopause, and spasticity in patients with multiple sclerosis44. Additionally, gabapentinoids are sometimes prescribed for chronic nociceptive pain to reduce reliance on NSAIDs or opioids. Between 2013 and 2018, gabapentinoid claims in Switzerland increased by 46%45. However, these medications, especially pregabalin, carry a risk of non-medical use for recreational purposes, with reports of poisoning and non-medical use rising between 2010 and 202046,47. Non-medical use seems especially prevalent and increasing in refugees, migrants, and incarcerated people, both in Switzerland and elsewhere48,49,50,51. In our study, central nervous ADRs such as cortical dysfunction, neurological signs and symptoms were most frequently associated with the use of gabapentinoids. As with opioid analgesics, these ADRs lead to an increased risk in secondary injuries, especially in older adults who combined opioids and gabapentinoids52,53.

This study has notable strengths, including its large dataset, encompassing 17,228 ICSRs and providing a comprehensive picture of ADR of drugs used in pain therapies across the country. Furthermore, by including a wide range of drugs used for pain management, both primary analgesic agents and also adjuvants, the study offers valuable insights into the safety profile of commonly prescribed drugs and therefore reflecting real-life use. Additionally, the real-life context of the data enhances its relevance, capturing a broad spectrum of patients’ characteristics and treatment practices. Distinguishing between older and younger adults provided important insights into a population that, while often in need of effective pain treatment, is more vulnerable to adverse outcomes.

The limitations of this study are inherent to the pharmacovigilance data set. Pharmacovigilance data relies on spontaneous reporting of adverse reactions, which means that an estimation of absolute incidences of adverse reactions is not possible. To account for this, we limited the analysis to descriptive and relative reporting patterns. All adverse events in this study were extracted from VigiBase, where they are coded using MedDRA terms. While the WHO definition of an ADR specifies reactions occurring at normal therapeutic doses for an indication, MedDRA terms also encompass events related to off-label use and overdoses. Consequently, our analysis reflects the database-reported terms without additional classification, and readers should interpret “ADRs” in this context as encompassing all spontaneously reported adverse drug events. We intentionally restricted our analysis to Swiss data to ensure methodological consistency, reporting comparability, and contextually appropriate interpretation within our national healthcare setting. This approach may limit the generalizability of the findings to other countries with different reporting systems and healthcare contexts. In our analysis we used RORs to calculate relative frequencies of reporting to be able to compare older and younger adults, assuming the age and the likelihood of reporting a reaction are independent. Nonetheless, RORs can merely provide a signal of a disproportionality and do not provide evidence of a causal harmful or protective effect. To investigate the differences between older and younger adults, this study distinguished two age categories, 18–74 and 75 years and older. However, future studies could investigate one or several more age categories to distinguish between young, middle aged and geriatric patients, as these could have systematic differences in both characteristics and treatment choices. The potential for underreporting of ADRs is a known issue of pharmacovigilance systems, which may result in an incomplete representation of the true incidence of adverse events. While the reporting of serious adverse reactions is mandatory under the Swiss Therapeutic Products Act54, non-serious reports are filed voluntarily and thus more rarely due to limited resources. Additionally, data on drug indications were often missing, leading to a lack of context of the drug’s use or the type of pain. This is particularly problematic for drugs with multiple indications, such as acetylsalicylic acid. However, we assumed that most adverse reactions, such as gastrointestinal ulcers and bleeding, would occur irrespective of the indication, although duration and dose might play an important role. Information on the duration and dosage of drug use, which might also vary by the indication, was frequently lacking, limiting the ability to assess the impact of these factors on adverse outcomes. The database did not contain information on whether the reported drugs were prescribed or purchased OTC, preventing us from distinguishing between these categories. This may influence ADR reporting patterns, particularly for medications available both by prescription and OTC. While the study provides nationwide data, it lacks detailed geographical information, which could offer insights into cantonal or language regional variations in prescribing and adverse event patterns. Similarly, given the study period spanning more than 30 years, it is likely that clinical guidelines, treatment restrictions, prescribing habits, and ADR reporting have evolved over time. While this does not impact the validity of the reported adverse reactions per se, it warrants caution when interpreting relative frequencies across drugs with differing or evolving patterns. Lastly, while this study highlights the vulnerability of older adults to serious ADRs, it does not account for other factors with a higher among older adults. Comorbidities and associated polypharmacy may have contributed to the observed differences in ADR profiles through increased susceptibility to drug–drug and drug–disease interactions, which could not be accounted for in this analysis.

In conclusion, this comprehensive study underscores the substantial risk of ADRs associated with commonly used pain medications, especially observed among older individuals compared to younger ones. In addition to age-related physiological changes, differences in comorbidity burden and polypharmacy play a significant role in shaping ADR risk profiles, underscoring the importance of individualized medication review and careful management of drug interactions in older patients. Reactions leading to hospitalisation or death in older adults were reported twice as frequently as in younger adults. The results of this real-world drug safety study emphasize the importance of individualized pain management, considering patients’ characteristics and substance risk profiles, while carefully balancing the benefit-risk profile of different medications to minimize adverse effects.

Data availability

As data is licensed by the UMC it is not available for sharing. The code used for analysis can be shared upon reasonable request to Lucia Gasparovic ([lucia.gasparovic@pharma.ethz.ch] (mailto:lucia.gasparovic@pharma.ethz.ch)).

References

Hooijman, M. F., Martinez-De la Torre, A., Weiler, S. & Burden, A. M. Opioid sales and opioid-related poisonings in Switzerland: A descriptive population-based time-series analysis. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 20, 100437 (2022).

Burgstaller, J. M. et al. Increased risk of adverse events in non-cancer patients with chronic and high-dose opioid use—A health insurance claims analysis. PLoS ONE 15, e0238285 (2020).

Wertli, M. M. et al. Changes over time in prescription practices of pain medications in Switzerland between 2006 and 2013: an analysis of insurance claims. BMC Health Serv. Res. 17, 167 (2017).

Müller, D., Scholz, S. M., Thalmann, N. F., Trippolini, M. A. & Wertli, M. M. Increased use and large variation in strong opioids and metamizole (dipyrone) for minor and major musculoskeletal injuries between 2008 and 2018: an analysis of a representative sample of Swiss workers. J. Occup. Rehabil. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-023-10115- (2023).

Scholz, S. M., Thalmann, N. F., Müller, D., Trippolini, M. A. & Wertli, M. M. Factors influencing pain medication and opioid use in patients with musculoskeletal injuries: a retrospective insurance claims database study. Sci. Rep. 14, 1978 (2024).

Johnson-Ferguson, L. et al. Higher paracetamol levels are associated with elevated glucocorticoid concentrations in hair: findings from a large cohort of young adults. Arch. Toxicol. 98, 2261–2268 (2024).

Janousch, C. et al. Words versus strands: reliability and stability of concordance rates of self-reported and hair-analyzed substance use of young adults over time. Eur. Addict. Res. https://doi.org/10.1159/000541713 (2024).

Uppsala Monitoring Centre. About VigiBase. https://who-umc.org/vigibase/.

Lagerlund, O., Strese, S., Fladvad, M. & Lindquist, M. WHODrug: a global, validated and updated dictionary for medicinal information. Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 54, 1116–1122 (2020).

MedDRA Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities. Introductory Guide MedDRA Version 27.0. (2024).

Uppsala Monitoring Centre. WHODrug portfolio. https://who-umc.org/whodrug/.

Uppsala Monitoring Centre. WHODrug Standardised Drug Groupings (SDGs). https://who-umc.org/whodrug/whodrug-standardised-drug-groupings-sdgs/.

Tregunno, P. M., Fink, D. B., Fernandez-Fernandez, C., Lázaro-Bengoa, E. & Norén, G. N. Performance of probabilistic method to detect duplicate individual case safety reports. Drug Saf. 37, 249–258 (2014).

International Conference On Harmonisation. E2A: Clinical Safety Data Management: Definitions and Standards for Expedited Reporting. In: International Conference On Harmonisation Of Technical Requirements For Registration Of Pharmaceuticals For Human Use (Brill | Nijhoff). https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004163300.i-1081.897. (1994).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2022).

Satorra, P., Carmezim, J., Pallarés, N. & Tebé, C. Flowchart: Tidy Flowchart Generator. (2024).

von Elm, E. et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 370, 1453–1457 (2007).

Fusaroli, M. et al. The reporting of a disproportionality analysis for drug safety signal detection using individual case safety reports in pharmacovigilance (READUS-PV): development and statement. Drug Saf. 47, 575–584 (2024).

Bouvy, J. C., De Bruin, M. L. & Koopmanschap, M. A. Epidemiology of adverse drug reactions in Europe: a review of recent observational studies. Drug Saf. 38, 437–453 (2015).

Budnitz, D. S. et al. National surveillance of emergency department visits for outpatient adverse drug events. JAMA 296, 1858–1866 (2006).

Howard, R. L. et al. Which drugs cause preventable admissions to hospital? A systematic review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 63, 136–147 (2007).

Pedrós, C. et al. Prevalence, risk factors and main features of adverse drug reactions leading to hospital admission. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 70, 361–367 (2014).

Chen, Y. C. et al. Comparing characteristics of adverse drug events between older and younger adults presenting to a Taiwan emergency department. Medicine (Baltimore) 94, e547 (2015).

Goetschi, A. N., Verloo, H., Wernli, B., Wertli, M. M. & Meyer-Massetti, C. Prescribing pattern insights from a longitudinal study of older adult inpatients with polypharmacy and chronic non-cancer pain. Eur. J. Pain 28, 1645–1655 (2024).

By the 2023 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2023 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 71, 2052–2081 (2023).

Mann, N.-K. et al. Potentially in the inadequate medications elderly: PRISCUS 2.0. Dtsch. Ärztebl. Int. 120, 3–10 (2023).

Pazan, F. et al. The FORTA (Fit fOR The Aged) list 2021: fourth version of a validated clinical aid for improved pharmacotherapy in older adults. Drugs Aging 39, 245–247 (2022).

Sawyer, P., Bodner, E. V., Ritchie, C. S. & Allman, R. M. Pain and pain medication use in community-dwelling older adults. Am. J. Geriatr. Pharmacother. 4, 316–324 (2006).

Schmiedl, S. et al. Preventable ADRs leading to hospitalization — results of a long-term prospective safety study with 6,427 ADR cases focusing on elderly patients. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 17, 125–137 (2018).

Cascorbi, I. The uncertainties of metamizole use. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 109, 1373–1375 (2021).

European Medicines Agency (EMA). Metamizole - direct healthcare professional communication (DHPC). https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/dhpc/metamizole (2020).

Helsana. Helsana-Arzneimittelreport. https://reports.helsana.ch/arzneimittel2023/. (2023).

Gut, S. et al. Use of metamizole and other non-opioid analgesics in Switzerland between 2014 and 2019: an observational study using a large health insurance claims database. Swiss Med. Wkly. 154, 3535–3535 (2024).

European Medicines Agency (EMA). EMA recommends measures to minimise serious outcomes of known side effect with painkiller metamizole. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/ema-recommends-measures-minimise-serious-outcomes-known-side-effect-painkiller-metamizole (2024).

Swissmedic. DHPC – Novalgin®, Metamizol Spirig HC®, Minalgin®, Novaminsulfon Sintetica®, Metamizol-Mepha® (metamizolum). https://www.swissmedic.ch/swissmedic/de/home/humanarzneimittel/marktueberwachung/healthcare-professional-communications/dhpc-metamizolum.html (2025).

Caparrotta, T. M., Antoine, D. J. & Dear, J. W. Are some people at increased risk of paracetamol-induced liver injury? A critical review of the literature. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 74, 147–160 (2018).

BMJ Best Practice. Paracetamol overdose in adults - Symptoms, diagnosis and treatment. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/3000110.

Martinez-De La Torre, A. et al. National poison center calls before vs after availability of high-dose acetaminophen (paracetamol) tablets in Switzerland. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e2022897 (2020).

Dafalgan Dolo Fachinformation. https://compendium.ch/product/17776-dafalgan-tabl-500-mg/mpro.

Gustafsson, M., Matos, C., Joaquim, J., Scholl, J. & van Hunsel, F. Adverse drug reactions to opioids: a study in a national pharmacovigilance database. Drug Saf. 46, 1133–1148 (2023).

Caré, W. et al. Trends in adverse drug reactions related to oral weak opioid analgesics in therapeutic use in adults: A 10-year French vigilances retrospective study. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 37, 1205–1217 (2023).

Yue, Q. et al. An updated analysis of opioids increasing the risk of fractures. PLoS ONE 15, e0220216 (2020).

Yoshikawa, A. et al. Opioid use and the risk of falls, fall injuries and fractures among older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 75, 1989–1995 (2020).

Kestner, R.-I., Graebner, K. T. & Luderer, M. Missbrauchsrisiko und Abhängigkeitspotenzial von Gabapentinoiden. Hess. Ärztebl. 1, (2024).

Wertli, M. M., Held, U., Signorell, A., Blozik, E. & Burgstaller, J. M. Analyse der Entwicklung der Verschreibungspraxis von Schmerz- und Schlafmedikamenten zwischen 2013 und 2018 in der Schweiz. (2020).

Tox Info Suisse. Jahresbericht. https://www.toxinfo.ch/customer/files/878/9211581_Tox_JB-2020_DE_Web.pdf. (2020).

Hofmann, M. & Besson, M. Gabapentinoids: The rise of a new misuse epidemics?. Psychiatry Res. 305, 114193 (2021).

Reye, B. Angstblocker in der Schweiz auf dem Vormarsch – Psychiater warnt. Tages-Anzeiger (2024).

Servais, L., Huberland, V. & Richelle, L. Misuse of Pregabalin: a qualitative study from a patient’s perspective. BMC Public Health 23, 1339 (2023).

Novotny, M. et al. Pregabalin use in forensic hospitals and prisons in German speaking countries—a survey study of physicians. Front. Public Health 11, 1309654 (2024).

Chappuy, M. et al. Gabapentinoid use in French most precarious populations: Insight from Lyon Permanent Access to Healthcare (PASS) units, 2016–1Q2021. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 36, 448–452 (2022).

Painter, J. T. et al. The effect of concurrent use of opioids and gabapentin on fall risk in older adults. J. Pain Palliat. Care Pharmacother. 0, 1–7 (2024).

Leung, M. T. Y. et al. Gabapentinoids and risk of hip fracture. JAMA Netw. Open 7, e2444488 (2024).

The Federal Assembly of the Swiss Confederation. Ther. Prod. Act. (2002).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Uppsala Monitoring Centre (UMC), which provided and gave permission to use the data analysed in the present study. VigiBase® the WHO global database of individual case safety reports (ICSRs) is the source of the information; the information comes from a variety of sources, and the probability that the suspected adverse effect is drug-related is not the same in all cases; the information does not represent the opinion of the UMC or the World Health Organization.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.G. and S.W. conceptualized the study. S.W. supervised the project. L.G. performed the data analysis, curated the data, and prepared the figures and tables. L.G. and S.W. wrote the original draft of the manuscript. S.N.J., B.B.Q., T.S., O.S., A.M.B. and S.M. reviewed and edited the manuscript and provided scientific and clinical input. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Prof. Weiler is a member of the Human Medicines Expert Committee of Swissmedic. The views expressed in this article are the personal views of the authors and may not be understood or quoted as being made on behalf of or reflecting the position of an agency or a committee or working party. While the authors used data from VigiBase®, the World Health Organization (WHO) global database of individual case report forms, as a source of information, the conclusions do not represent the opinion of the Uppsala Monitoring Centre (UMC) or the World Health Organization. The remaining authors have no competing interests to declare.

Ethical approval and informed consent

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. VigiBase®, the WHO global database of individual case safety reports (ICSRs), is the source of the information; the information comes from a variety of sources, and the probability that the suspected adverse effect is drug related is not the same in all cases; the information does not represent the opinion of the Uppsala Monitoring Centre (UMC) or the World Health Organization (WHO). According to WHO policy and UMC guidelines, reports sent from the WHO Programme for International Drug Monitoring member countries to VigiBase® are anonymized. Identifiable data are not available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gasparovic, L., Burden, A.M., Senn, O. et al. Age disparities in adverse reactions of drugs used in pain therapies in Switzerland. Sci Rep 15, 45301 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28959-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28959-7