Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted work-life balance (WLB), particularly among workers in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). This study aimed to classify patterns of WLB changes and identify associated factors using the Job Demands–Resources model as a theoretical framework. A cross-sectional survey was conducted among 503 SME employees in South Korea between July and September 2020. Latent class analysis identified WLB change patterns, and multinomial logistic regression compared factors across classes. Three latent classes were identified: stable (Class 1, 81.0%), worsened (Class 2, 11.4%), and improved (Class 3, 7.6%). Compared to Class 1, Class 2 was more likely to include individuals with higher economic status (OR = 2.163) and less likely to perceive strong organizational support (OR = 0.466). Compared to Class 1, Class 3 included more individuals with better psychosocial health and higher adherence to personal infection prevention (OR = 3.499). Compared to Class 3, individuals in Class 2 were more likely to have poorer psychosocial health (OR = 32.827), and less likely to report a supportive organizational environment (OR = 0.443). Workplace-level infection control scores were significantly higher in Class 3 than in other classes (p < .001). Distinct WLB patterns were observed among SME workers during COVID-19. Psychosocial health, economic status, infection prevention, and organizational support significantly influenced class membership. Identifying and supporting vulnerable groups during future public health crises is essential through targeted, workplace-level interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, the concept of Work-life balance (WLB) has gained increasing attention as an important aspect of occupational health and overall well-being. WLB can be defined as the equilibrium between one’s professional duties and personal activities, encompassing family, personal growth, and leisure1. It represents a state in which individuals are content with their lives, having achieved a sense of control by effectively distributing their time and both physical and psychological energy between their work and personal spheres2. The ability to maintain a good WLB within the limits of 24 h per day3 was significantly disrupted during the COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in substantial changes in daily routines and work environments. To achieve WLB, it is important to appropriately allocate time between the different areas of work and life, without over- or under-committing to any single area4. Ultimately, WLB involves finding a harmonious equilibrium between work and personal life, resulting in a state of high life satisfaction.

A poor WLB is associated with increased health problems5. The socio-psychological health of workers is influenced by several factors, such as job autonomy, working more than 53 h a week, and low support at work6. Additionally, workplace hazards, including exposure to low temperatures, contact with infectious materials, and musculoskeletal strain, can further deteriorate workers’ socio-psychological well-being7. Stress and anxiety can also impair socio-psychological health5, which may lead to a worsening of illnesses among workers and a rise in sickness absences8, ultimately affecting their WLB. Given these associations, disruptions caused by external stressors such as the COVID-19 pandemic could significantly influence workers’ WLB. These established associations suggest that disruptions caused by external stressors such as the COVID-19 pandemic could significantly influence workers’ WLB.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought about numerous changes in economic, family, and recreational activities. Governments have implemented social distancing measures, including mandatory mask-wearing and maintaining a distance of one meter between individuals, while urging active public participation. For instance, schools transitioned to virtual classes during the early stages of the pandemic in 20209, further compounding the emotional strain particularly for Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) employees who typically have limited support structures at work and fewer opportunities to utilize flexible working options10.

Flexible working is an arrangement that enables both employees and employers to select and modify their work hours and locations, aiming to enhance WLB and efficient human resource utilization11. Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the Ministry of Employment, Labour and Social Affairs in South Korea has advocated for variable working hours and the option for employees to work from home for part of the time12. Although flexible working arrangements were suggested prior to the pandemic13 and were previously associated with worker dissatisfaction14, research conducted after 2020 has indicated that such arrangements can have positive effects on mental health15,16. However, SMEs often faced challenges in adopting flexible working due to structural and resource limitations.

SMEs, which account for a large proportion of employment in many countries, including South Korea, often face resource constraints that limit their capacity to implement organizational changes such as flexible work arrangements17. Compared to large corporations, SME workers are more likely to experience job insecurity, insufficient support systems, and limited occupational health resources during crises18. These structural vulnerabilities may heighten the impact of external stressors, such as a pandemic, on workers’ psychosocial health and WLB. Therefore, it is crucial to investigate how COVID-19 affected WLB specifically among SME employees, who are often overlooked in crisis response research. This need is particularly salient in the South Korean context, where labor market characteristics pose distinct challenges to WLB. South Korea consistently ranks among the countries with the longest working hours in the OECD, averaging 1,927 h annually in 2020—significantly higher than the OECD average of 1,582 h19. The employment structure is dominated by SMEs and characterized by a substantial share of non-regular employment, which increases job insecurity and limits access to workplace benefits. Moreover, nearly half of middle-aged households are dual-earner families20, reflecting the increasing economic necessity for both partners to work and the heightened tension between occupational and family responsibilities.

To better understand how workplace changes during the COVID-19 pandemic have influenced employees’ WLB, this study applies the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model21. According to this model, WLB is shaped by the interaction between job demands—such as long working hours, psychosocial strain, economic pressure—and job resources, including flexible work arrangements, and personal preventive behaviors. In South Korea, where prolonged working hours are known to negatively impact worker health and well-being22, the buffering role of job resources becomes particularly critical during crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, which disrupted workers’ lifestyles, family dynamics, and working patterns23. However, the impact of the pandemic on WLB has not been uniform across individuals; it has varied depending on personal and occupational characteristics24.

Previous research has rarely investigated the heterogeneous responses of SME employees to pandemic-induced disruptions in WLB. Thus, classifying these diverse responses is critical. This study aimed to classify patterns of changes in WLB due to COVID-19 using latent class analysis during the height of the pandemic in 2020, when social distancing policies posed significant challenges to workers. It also sought to identify the factors associated with each latent class based on the JD-R model. The specific objectives of the study were as follows: First, to classify latent classes of changes in WLB due to COVID-19 among workers during the pandemic. Second, to identify the factors influencing these changes according to the JD-R model.

Methods

Research design

This study employed a descriptive, cross-sectional survey design to examine changes in WLB among Korean workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. The analysis was guided by the JD-R model, which conceptualizes changes in WLB as outcomes influenced by the interaction of job demands and job resources (Fig. 1).

Participants and data collection

This study was conducted between July and September 2020 among employees at small and SMEs located in Gyeonggi Province, South Korea. For this study, SMEs were defined as workplaces with fewer than 400 employees, including small enterprises (≤ 50 employees) and medium-sized enterprises (51–400 employees), in accordance with the operational categorization used in Korean occupational health research. The sample included workers from three industry sectors: manufacturing (33.8%), services (45.9%), and construction (20.3%). Due to COVID-19 pandemic restrictions that limited direct access to workplaces, convenience sampling was employed as the most feasible recruitment strategy. The study’s purpose and objectives were communicated to the managers, who provided their consent. Additionally, workers from smaller-scale operations were recruited with the assistance of the Federation of Korean Trade Unions and the Small Workplace Healthcare Association within their operational areas in Gyeonggi Province. Data were collected using self-administered paper questionnaires distributed to participants at their workplaces. The survey was not nationally representative, reflecting the geographic and organizational limitations imposed by pandemic-related restrictions.

Using the G*Power program, we determined that an effect size of 0.15, a significance level of 0.05, a power of 0.95, and 10 predictors would require a sample size of 147. However, latent class analysis typically requires larger sample sizes, with a minimum of 300 participants recommended for stable class estimation25. Therefore, considering a potential 20% dropout rate, we initially surveyed 508 individuals. After excluding six respondents due to incomplete data, we analysed the data from 503 participants.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Eulji University (EU20-034). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The objectives of the study were clearly communicated to the participants, who were assured of their anonymity. A consent form was provided, which outlined their right to withdraw from the study at any point without consequence. To safeguard the participants’ privacy, a return envelope was included with the questionnaire, allowing them to seal their responses immediately upon completion. The researcher personally collected the completed questionnaires and provided a box of face masks to participants as a token of appreciation for their participation, which was considered particularly valuable during the COVID-19 pandemic when such protective equipment was essential. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Instruments

The measurement instruments in this study were organized according to the Job Demands–Resources (JD–R) model framework. Job demands refer to physical, psychological, or organizational aspects of work that require sustained effort, while job resources are aspects that help achieve work goals, reduce demands, or facilitate personal growth21.

Changes in WLB due to COVID-19

WLB was measured using an instrument developed by Kim and Park1. This tool comprises 9 questions addressing work-growth balance, 8 questions focused on work-leisure balance, 4 questions pertaining to overall WLB, and 8 questions related to work-family balance, culminating in a total of 29 questions. In this study, participants were asked to evaluate how their WLB had changed due to COVID-19 using a 7-point scale. The scale ranged from 1, indicating a “worse” change, to 7, signifying a “better” change, with higher scores denoting more favourable changes in WLB as a result of COVID-19. For the latent class analysis, we used the four subscale scores (work-growth balance, work-leisure balance, WLB in general, and work-family balance) as indicator variables rather than individual items. Each subscale score was calculated as the means of its constituent items.

Job demands

In this study, psychosocial well-being was conceptualized as an indicator reflecting the cumulative burden of job demands rather than as a demand itself. Poor psychosocial health signals insufficient personal resources to cope with existing demands, making it a relevant outcome measure within the JD–R framework. Workplace infection-prevention practices were regarded as organizational-level demands because they represent the extent to which workers must respond to and manage COVID-19-related risks in their work environments, adding to their cognitive and emotional load. Working hours were treated as traditional time-based demands that limit workers’ opportunities to recover and engage in personal or family activities.

Psychosocial well-being index (PWI)

Social-psychological well-being was assessed using the 18-item shortened version of the Psychosocial Well-being Index (PWI-SF), which was developed by Chang26 and has been validated for both validity and reliability. This instrument includes subscales that measure general health and vitality, social role performance and self-confidence, sleep disorders and depression, as well as depression and anxiety. It employs a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all true) to 3 (always true), where lower scores indicate better social and psychological health. The aggregate score of the 18 items was calculated and categorized into three groups: a healthy group (0 to 8 points), a potentially stressed group (9 to 26 points), and a high-risk group (27 points or more).

Workplace infection prevention practices for COVID-19

Workplace-level COVID-19 infection prevention practices were assessed using a 10-item instrument developed and validated by Jung and Choi27, which was originally designed for small-sized enterprises during the early COVID-19 pandemic and based on the Ministry of Employment and Labor’s workplace response guidelines. The items reflect preventive actions implemented in workplaces during the pandemic, including temperature monitoring at entry points, installation of protective barriers, maintaining physical distance among workers, provision of hand sanitizer, mandatory mask wearing, routine disinfection, restrictions on shared spaces, staggered lunch breaks, and discouragement of indoor smoking. Responses were rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“rarely implemented”) to 4 (“fully implemented”), with higher scores indicating a greater level of workplace adherence to COVID-19 prevention practices.

Working hours

Working hours were categorized into three ranges: 40 h or less, 40 to 51 h, and 52 h or more per week. These categories were based on the legal standard working hours in South Korea (40 h per week), with 52 h representing the upper legal limit including overtime.

Job resources

Personal infection-prevention behaviors were classified as personal resources because they reflect proactive coping strategies that individuals employ to regain a sense of control and reduce pandemic-related stress. Flexible work arrangements were conceptualized as organizational resources, as they enhance autonomy and adaptability, allowing workers to manage competing work and personal responsibilities more effectively. Subjective economic status was included as a personal resource, representing a psychological and material buffer that mitigates the impact of economic insecurity during crisis periods.

Factors related to a flexible work system

Flexible working was assessed using an instrument developed by Kim28, which was based on prior research. This study categorized sub-factors for facilitating a flexible work system into four groups: institutional factors (such as diversity of types and maintenance of regulations and procedures), organizational environment factors (including manager’s willingness and colleagues’ perceptions), work content factors (appropriate work and workload), and human resource management factors (non-monetary benefits and personnel disadvantages). Participants responded to a total of eight questions on a 5-point scale, where 1 indicated “not at all,” 2 “not,” 3 “moderate,” 4 “yes,” and 5 “very much so.” Two negatively worded items were reverse-scored to calculate the overall mean, with higher scores indicating a more effective flexible working system. Cronbach’s α in this study was 0.716.

Personal infection prevention behaviors for COVID-19

Individual-level infection prevention behaviors related to COVID-19 were assessed using a 10-item scale developed based on the Ministry of Employment and Labor’s guidelines, with input from three occupational health nurses. The items included behaviors such as canceling or postponing social gatherings, reducing use of public transportation and visits to shopping centers, avoiding enclosed public spaces such as karaoke rooms and cinemas, minimizing visits to crowded places, taking extra care with cleanliness and hygiene, washing hands frequently, refraining from physical contact such as handshakes, and maintaining social distancing during meals. Each item was rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“rarely practiced”) to 4 (“practiced very well”), with higher scores indicating a higher level of personal adherence to infection prevention behaviors.

Subjective economic status

Subjective economic status was assessed using a 5-point Likert scale, where participants rated their perceived household economic condition from 1 (“very low”) to 5 (“very high”). For analysis, responses were recoded into two groups: “low” (scores 1 to 2) and “above average” (scores 3 to 5), as relatively few participants rated their status as “high” (scores 4 or 5). This recording allowed for meaningful group comparison while maintaining sufficient sample size in each category.

Control variables

Demographic and occupational characteristics

Control variables included participants’ gender, age, and marital status. Occupational characteristics included industry type (manufacturing, services, and construction), business size (small: ≤50 employees; medium: 51–400 employees), work schedule (daytime vs. shift work), employment type (regular vs. non-regular employment), and position level (staff vs. supervisor or above).

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using Mplus 8.5 and SPSS 26.0 in accordance with the study objectives. First, descriptive statistics (frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation) were calculated to summarize the sociodemographic, occupational, and psychological characteristics of the participants.

Second, latent class analysis (LCA) was conducted to classify patterns of changes in WLB due to COVID-19. Model selection was based on a combination of fit indices including the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), sample size-adjusted BIC (saBIC), entropy, the Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (LMR), and the bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT). Lower AIC and BIC values suggest better model fit, while higher entropy values (closer to 1) indicate clearer classification quality. Significant p-values from LMR and BLRT confirm whether a model with k latent classes significantly improves upon a model with k-1 classes29,30. Third, chi-square tests and one-way ANOVA were used to examine differences in participants’ characteristics across the identified latent classes. For ANOVA analyzes that showed significant differences, Scheffé’s post-hoc test was conducted to identify which specific latent classes differed from each other. The Scheffé method was selected because it is conservative and appropriate when comparing groups of unequal sample sizes, as was the case with our three latent classes. Finally, multinomial logistic regression was performed to identify factors associated with each latent class. Only variables that showed statistically significant differences in the prior analysis were included in the final regression model.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

The mean age was 49.2 years, and 68.2% were male. Most participants were living with a spouse (74.4%) and worked daytime hours (91.8%). Non-regular employment accounted for 58.1%. In terms of industry, 45.9% worked in services, 33.8% in manufacturing, and 20.3% in construction. 53.3% worked fewer than 40 h per week.

The majority (86.9%) were in the potential stress group on the Psychosocial Well-being Index. The average scores for workplace and personal infection prevention were 3.0 and 3.3, respectively. Among flexible work factors, human resource management scored the highest. Work-life balance scores across domains averaged 3.9 out of 7 (Table 1).

Latent classes of work-life balance changes during the COVID-19 pandemic

Latent classes related to changes in WLB during COVID-19 were identified using latent class analysis (Table 2). As the number of classes increased from one to four, the AIC, BIC, and aBIC values decreased steadily, indicating improved model fit. Although Model 4 had the lowest fit indices, the elbow point was observed at the three-class model. Additionally, the three-class model demonstrated adequate entropy (0.874) and significant values for both the LMR (p =.0092) and BLRT (p <.001), supporting the appropriateness of this model. Given the model fit, parsimony, and interpretability, the three-class model was selected as the final model.

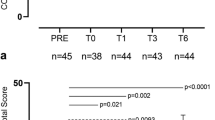

Figure 2 illustrates the mean scores for each WLB domain across the three latent classes. Class 1, representing the majority (80.1%), showed relatively stable scores across all domains, indicating no significant perceived change in WLB. Class 2 (11.4%) consistently reported lower scores, reflecting a worsened WLB, particularly in the domains of work-growth and work-leisure. In contrast, Class 3 (8.5%) demonstrated higher scores in all areas, indicating an overall improvement in WLB during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Differences in participant characteristics by latent classes of work-life balance changes during COVID-19

According to latent class, there were statistically significant differences in several key variables. Psychosocial well-being significantly differed across classes (p <.001), with Class 3 (improved WLB) having the highest proportion of healthy individuals, while Class 2 (worsened WLB) had the highest proportion of high-risk individuals.

Workplace infection prevention practices scores were significantly higher in Class 3 than in Classes 1 and 2 (p <.001). Similarly, personal infection prevention behaviors were significantly higher in Class 3 compared to Classes 1 and 2 (p <.001). Among flexible work arrangement factors, institutional factors (p =.003), organizational environmental factors (p <.001), and work content factors (p =.002) showed significant differences across classes. Organizational environmental factors were particularly lower in Class 2 compared to Classes 1 and 3, while work content factors were highest in Class 3 compared to Classes 1 and 2 (Table 3).

Factors associated with latent classes of work-life balance changes

To identify factors associated with each latent class, a multinomial logistic regression analysis was conducted (Table 4). The reference group was set to Class 1 (no change in WLB) and Class 3 (improved WLB), respectively. Among control variables, marital status was included in the final model, as it showed a trend toward significance (p <.10) in the bivariate analysis.

When comparing Class 2 (worsened) to Class 1 (no change), participants with a higher subjective economic level were more likely to belong to Class 2 (OR = 2.163, 95% CI = 1.042–4.487). Meanwhile, those with higher scores in organizational environmental factors were more likely to be in Class 1 than in Class 2 (OR = 0.466, 95% CI = 0.244–0.890).

When comparing Class 3 (improved) to Class 1 (no change), participants in the potential risk group for psychosocial well-being were less likely to be in Class 3 (OR = 0.055, 95% CI = 0.008–0.394), as were those in the high-risk group (OR = 0.100, 95% CI = 0.025–0.392). In contrast, individuals with higher personal infection prevention behaviors were more likely to belong to Class 3 (OR = 3.499, 95% CI = 1.370–8.934).

When comparing Class 2 (worsened) to Class 3 (improved), participants in the potential risk group for psychosocial well-being were more likely to belong to Class 2 (OR = 32.827, 95% CI = 1.918–561.898), whereas those with higher scores in organizational environmental factors were more likely to be in Class 3 than in Class 2 (OR = 0.443, 95% CI = 0.205–0.958).

Discussion

Three distinct latent classes of changes in WLB were identified among workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: no change, worsened, and improved. These classes were derived based on patterns observed across four domains (work-growth, work-leisure, work-family, and overall WLB).

Our study revealed significant differences in psychosocial well-being across the three latent classes. Class 2, representing workers who experienced worsened WLB, had the highest proportion of individuals in the high-risk group for psychosocial well-being. In contrast, Class 3, characterized by improved WLB, had the highest proportion of psychologically healthy individuals. While the cross-sectional nature of our study prevents determination of causality, these findings align with previous research by Kim31, who found that emotional states such as depression and anxiety can undermine WLB by inducing job stress. The COVID-19 pandemic intensified this relationship through unprecedented social distancing measures that disrupted traditional social support networks. This aligns with32, who noted that reduced social interaction during the pandemic often led to increased psychological distress, particularly among individuals lacking adequate social support systems. The relationship between psychosocial health and WLB changes also reflects the challenges of adapting to new work arrangements during crisis periods. Flexible work arrangements, which were increasingly implemented during the pandemic, may not have benefited all workers equally. Cheng et al.33 found that telecommuting was associated with heightened loneliness due to diminished colleague interaction, potentially exacerbating existing psychological vulnerabilities. Similarly, Kaduk et al.13 demonstrated that teleworking can have negative consequences for workers who face heightened family conflict and stress, particularly when such arrangements are imposed involuntarily rather than chosen. Our findings suggest that the pandemic’s impact on WLB was not uniform but varied significantly based on individuals’ psychological resources. Workers with stronger psychological health appeared better equipped to adapt to pandemic-related changes, potentially even finding opportunities for improved WLB. In contrast, those with poorer psychosocial health faced greater challenges in maintaining work-life equilibrium amid the crisis. This underscores the importance of psychological support systems during public health emergencies, particularly for vulnerable workers in SMEs who may have limited access to formal mental health resources.

In this study, poorer social and psychological health negatively affected changes in WLB due to COVID-19. The potential-risk group and high-risk group experienced more adverse changes in WLB compared to the healthy group. This aligns with previous research indicating that emotional states such as depression and anxiety, common in at-risk or high-risk individuals, can undermine WLB by inducing job stress31. Similarly, telecommuting, a type of flexible work, has been linked to increased loneliness due to diminished interaction with colleagues33. The findings suggest that flexible work arrangements may not benefit workers with poor social and psychological health. This is consistent with evidence that teleworking can have negative consequences for workers who face heightened family conflict and stress13. The reduced social interaction and economic losses associated with social distancing can prompt a re-evaluation of life’s motivations, meaning, and values, potentially leading to negative psychological effects32. These findings reflect the job demands-resources model, where poor psychological health can function as an additional demand that reduces workers’ capacity to maintain work-life equilibrium. The health of these workers should be closely monitored when flexible work arrangements are introduced in the workplace. Moreover, previous studies have indicated that negative effects can arise when flexible work arrangements are imposed involuntarily13, suggesting that adjustments may be necessary to accommodate workers who have negative opinions about such arrangements.

The present study found significant differences across latent classes in three key dimensions of flexible work arrangements. Class 3 (improved WLB) consistently demonstrated the highest scores in institutional factors, organizational environmental factors, and work content factors, followed by Class 1 (stable WLB), while Class 2 (worsened WLB) showed the lowest scores. Flexible work arrangements have been identified as a positive factor influencing changes in WLB due to COVID-19, echoing findings from previous studies that highlight the benefits of such arrangements for WLB34. In Korea, the adoption of flexible work arrangements has lagged behind that of major developed countries, with companies pointing to challenges in managing time and attendance, as well as human resources, as reasons for their hesitation35. Large organizations are typically more adept at adopting and effectively implementing the latest solutions than SMEs36, making flexible working arrangements more feasible for them compared to smaller businesses37. However, the forced implementation of flexible working arrangements during the COVID-19 pandemic appears to have had a favorable impact on WLB even within SMEs. Our findings indicate that specific organizational characteristics—including company size, industry type, and nature of tasks—significantly influence the feasibility of flexible working arrangements. Many tasks within SMEs are thus not easily adaptable to such arrangements. Jobs that require face-to-face interaction, such as those in the service and skilled trades sectors, as well as blue-collar roles where telecommuting is not an option, were identified as the most challenging to perform flexibly38. Peschl et al.39 proposed that a practical tool should be developed to identify opportunities for flexibility, including mobile and time-flexible work, specifically for SMEs. This would facilitate discussions between employers and workers, works councils, and job applicants. Within the JD-R framework, flexible work arrangements appear to function as important resources that can buffer against the demands imposed by the pandemic. Interestingly, human resource management factors—which primarily concern potential personnel disadvantages associated with using flexible work arrangements—did not significantly differ across the three classes. This finding likely reflects the broader policy context in South Korea during the pandemic, when the government actively encouraged flexible work arrangements as part of its COVID-19 response strategy40. To encourage the adoption of flexible working in SMEs, it is necessary to develop tools and support systems that address labor costs and cater to the diverse needs of workers, encompassing aspects such as work growth, work-family balance, and overall work-life integration.

Subjective economic status was also found to influence WLB changes. This aligns with previous research indicating that the COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately affects lower economic groups, with those at the lower end of the economic spectrum experiencing a heightened sense of crisis and a more significant psychological impact from the pandemic41. While the COVID-19 pandemic has led to increased stress at home for many workers42 and concerns over potential declines in economic status43, this study suggests that individuals in lower economic groups may be particularly vulnerable. From a JD-R perspective, lower economic status appears to function as an additional demand that further strains workers’ ability to maintain work-life balance. Lacking access to flexible working arrangements, these workers may have faced more severe impacts from COVID-1944. The findings of this study reveal the importance of implementing targeted support measures for economically vulnerable workers during public health crises. Without appropriate protections, these workers may experience cascading negative effects on their WLB, further exacerbating existing socioeconomic disparities. These findings highlight the need for policy responses specifically tailored to the South Korean SME context, including equitable access to flexible work arrangements and additional social support for lower-income workers in SMEs.

The present study revealed that individuals with higher personal infection prevention behaviors were more likely to belong to Class 3, representing improved WLB during the COVID-19 pandemic. Those who maintained strong personal prevention practices may have experienced less anxiety about potential infection, allowing them to focus better on both work responsibilities and personal life. While the cross-sectional nature of this study prevents determining causality, the significant association between these variables is noteworthy. Personal infection prevention behaviors appear to function as effective coping strategies during the pandemic45. Previous research has shown that maintaining preventive health behaviors can reduce psychological distress during public health crises46. The reduction in face-to-face contact and increased time spent at home likely contributed to this effect47. This alternative pathway, where reduced social activities due to prevention behaviors created additional time and opportunity for life enrichment, cannot be excluded as a potential mechanism through which prevention behaviors contributed to improved WLB. This finding is particularly relevant for the South Korean work context, extending this understanding by linking such behaviors to improved WLB, particularly for SME employees who may have had fewer organizational resources for coping with the pandemic compared to those in larger corporations. The relationship between personal prevention behaviors and improved WLB also highlights the importance of individual resilience during crisis periods48. When faced with disruptive events like the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals who actively engage in preventive health behaviors appear better positioned to constructively adapt their work and life routines, potentially avoiding deterioration in their WLB.

Workplace-level infection prevention practices emerged as another significant factor in the univariate analysis, with scores being significantly higher in Class 3 (improved WLB) than in other classes. This finding initially suggested the important role of organizational support in fostering positive WLB outcomes during crisis situations. Workplaces that implemented comprehensive prevention measures appeared to provide emotional security to workers, potentially contributing to improved WLB49. However, in the multinomial logistic regression analysis, workplace infection prevention practices did not emerge as a statistically significant predictor of latent class membership. This indicates that while workplace prevention measures may have a positive influence, their effect was likely overshadowed by other more influential factors identified in this study. This result has important implications for pandemic workplace management in South Korean SMEs, suggesting that workplace infection prevention measures should be considered as basic requirements during pandemic situations rather than distinguishing factors for improving WLB.

Despite extensive literature suggesting that working hours significantly impact WLB50, the present study found no significant differences in working hours across the three latent classes of WLB changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. This unexpected finding contrasts with previous research and warrants careful consideration, particularly given South Korea’s notably long working hours culture19. The absence of a significant relationship between working hours and WLB changes may reflect the complex dynamics at play during the pandemic’s economic disruption. These extended working hours have become a significant social concern in South Korea, as they contribute to employee burnout51. To enhance workers’ quality of life, the government has reduced the maximum workweek from 60 to 52 h and has implemented initiatives to encourage a shift from a work-centred to a life-centred approach52. The culture of long working hours reflects the work-centric mentality prevalent in South Korea and has been linked to a range of health issues, including increased mortality and cardiovascular disease22. The absence of a significant relationship between working hours and WLB changes may reflect the complex dynamics at play during the pandemic’s economic disruption. This unexpected finding likely reflects the unique economic context of the pandemic, where traditional relationships between working hours and WLB were disrupted by broader concerns. Many occupations that typically involved long working hours experienced significant reductions in work time due to social distancing measures and economic slowdowns. Despite this reduction in working hours, the lack of impact on WLB may reflect that workers’ concerns about economic security and livelihood superseded potential benefits from reduced working time. The psychological burden of financial uncertainty likely outweighed the positive effects of shorter working hours for many employees, particularly those in SMEs who may have had fewer financial reserves or institutional protections. While many industries saw reduced working hours, others—such as delivery services, healthcare, and essential retail—experienced intensified workloads and extended hours23. The current study did not specifically include these occupational groups that faced increased working hours during the pandemic. Future research should examine WLB changes in these sectors that experienced contrasting patterns of working hours during public health crises, as they may reveal different relationships between working time and WLB under emergency conditions.

The limitations of this study are as follows. First, the cross-sectional design of this study limits the ability to infer causal relationships among factors associated with WLB changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Longitudinal data would be required to establish temporal precedence and causal pathways between job demands, job resources, and WLB outcomes. Second, data were collected through convenience sampling during the pandemic, which may limit the representativeness of the sample. Participants were recruited through managerial consent and trade union networks, potentially overrepresenting workers from enterprises with stronger labor–management communication or greater organizational support. Workers in more precarious or informal SME settings may therefore be underrepresented, limiting the generalizability of the findings to the broader SME population in South Korea. Third, changes in WLB were assessed retrospectively based on participants’ subjective perceptions rather than longitudinal measurements. While this approach captures self-referenced perceptions of change, it may be influenced by recall bias or current contextual factors. Future studies employing prospective designs would allow a more accurate assessment of temporal changes in WLB. Fourth, the data were collected during a specific phase of the pandemic (July–September 2020), when strict social distancing measures were enforced. Findings may not generalize to later stages when workplace practices, vaccination availability, and policy environments evolved. Additionally, stratified analyses by demographic characteristics were not conducted due to small sample sizes in certain latent classes; future research with larger samples could explore subgroup variations. Finally, although the sample included workers from manufacturing, service, and construction sectors, it was geographically limited to Gyeonggi Province. Regional variations in pandemic severity, policy implementation, and economic conditions may limit the applicability of these findings to other regions or countries.

Nevertheless, this study offers several significant contributions to the field of occupational health and WLB. First, it is one of the few relatively large-scale studies conducted during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, capturing the immediate impacts of the crisis on workers in SMEs. Second, by applying latent class analysis, it provides a nuanced understanding of heterogeneous WLB trajectories—moving beyond average effects to identify distinct response patterns. Third, the study applies the Job Demands–Resources model to identify both risk factors (e.g., poor psychosocial health, limited organizational support) and protective factors (e.g., personal infection prevention behaviors, flexible work environments) associated with these trajectories. Finally, the findings highlight that even within structurally vulnerable employment contexts, such as SMEs, positive adaptation is possible when adequate personal and organizational resources are present. These insights offer valuable implications for targeted policy and workplace interventions to protect workers’ well-being during future public health emergencies.

Conclusions

This study identified three distinct trajectories of WLB (WLB) changes among SME workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: stable, worsened, and improved. Psychosocial health, subjective economic status, organizational environment, and infection prevention behaviors were found to significantly influence class membership. While flexible work arrangements contributed to improved WLB for some, their effectiveness was moderated by workers’ psychosocial status and workplace support. These findings highlight that maintaining or enhancing WLB during public health crises requires more than offering flexible schedules—it necessitates a comprehensive approach that addresses both individual vulnerabilities and organizational capacity. Given that SMEs may face structural limitations in adopting flexible work practices, targeted support from experts or public institutions is essential to help them build resilient and health-supportive work environments.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Kim, C. W. & Park, C. Y. A study on the development of a ‘work-life balance’ scale. J. Leis Stud. 5, 53–69. https://doi.org/10.22879/slos.2008.5.3.53 (2008).

Kim, C. W., Park, C. Y., Sohn, Y. M. & Jang, H. The conceptual Understanding on ‘work-life balance’ and its effectiveness. J. Leis Stud. 2, 29–48 (2005).

Choi, H. & Shin, J. W. The politics of working time flexibilization and time sovereignty: the case of the German ‘working time account’. Korea Soc. Policy Rev. 29, 147–175. https://doi.org/10.17000/kspr.29.3.202209.147 (2022).

Noh, H. J. A categorization of time guarantee in work-life balance. Health Soc. Welf. Rev. 43, 192–214. https://doi.org/10.15709/hswr.2023.43.2.192 (2023).

Lunau, T., Bambra, C., Eikemo, T. A., van der Wel, K. A. & Dragano, N. A balancing act? Work-life balance, health and well-being in European welfare States. Eur. J. Public. Health. 24, 422–427. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cku010 (2014).

Yang, J. W., Suh, C., Lee, C. K. & Son, B. C. The work-life balance and psychosocial well-being of South Korean workers. Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 30, 38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40557-018-0250-z (2018).

Russo, M., Lucifora, C., Pucciarelli, F. & Piccoli, B. Work hazards and workers’ mental health: an investigation based on the fifth European working conditions survey. Med. Lav. 110, 115–129. https://doi.org/10.23749/mdl.v110i2.7640 (2019).

Antai, D., Oke, A., Braithwaite, P. & Anthony, D. S. A ‘balanced’ life: work-life balance and sickness absence in four nordic countries. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 6, 205–222. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijoem.2015.667 (2015).

Lee, M. & Murphy, C. T. Tinkering in the time of COVID: lessons from educators’ efforts to facilitate playful tinkering through online learning. Educ. 3–13. 50, 127–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2022.2069350 (2022).

Calvano, C. et al. Families in the COVID-19 pandemic: parental stress, parent mental health and the occurrence of adverse childhood experiences—results of a representative survey in Germany. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 31, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01739-0 (2022).

Kuk, M. A. Flexible work arrangements and gender politics of working time: focusing on part-time work. Womens Stud. Rev. 30, 3–34. https://doi.org/10.18341/wsr.2013.30.1.3 (2013).

Ministry of Employment and Labor. Workplace Response Guidance for Preventing and Controlling the Spread of Coronavirus (COVID-19) 6th edn. (2020). https://www.moel.go.kr/local/incheonbukbu/news/notice/noticeView.do?bbs_seq=20200200950

Kaduk, A., Genadek, K., Kelly, E. L. & Moen, P. Involuntary vs. voluntary flexible work: insights for scholars and stakeholders. Community Work Fam. 22, 412–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2019.1616532 (2019).

Bohle, P., Willaby, H., Quinlan, M. & McNamara, M. Flexible work in call centres: working hours, work-life conflict & health. Appl. Ergon. 42, 219–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2010.06.007 (2011).

Senthanar, S., Varatharajan, S. & Bigelow, P. Flexible work arrangements and health in white-collar urban professionals. New. Solut. 30, 294–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/1048291120976642 (2021).

Shiri, R. et al. The effect of employee-oriented flexible work on mental health: a systematic review. Healthcare 10, 883. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10050883 (2022).

Kotey, B. & Sharma, B. Predictors of flexible working arrangement provision in small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 27, 2753–2770. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1102160 (2016).

Elia, G. & Del Vecchio, P. Business continuity management and organizational resilience: a small and medium enterprises (SMEs) perspective. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 31, 670–682. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.12470 (2023).

Statistics Korea. Average Annual Working Hours per Worker (OECD Member Countries). (2024). https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=101&tblId=DT_2KAA314_OECD

Hwang, N. A. Study of the Living Conditions and Welfare Needs of the New Middle-aged. Policy Report 2020-03 (Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs, 2020).

Bakker, A. B. & Demerouti, E. Job demands–resources theory: taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 22, 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000056 (2017).

Kim, S. & Jung, Y. Effect of long working hours on cardiovascular disease in South Korean workers: a longitudinal study. Asia Pac. J. Public. Health. 33, 213–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/1010539520979927 (2021).

Clemente-Suárez, V. J., Dalamitros, A. A., Beltran-Velasco, A. I., Mielgo-Ayuso, J. & Tornero-Aguilera, J. F. Social and Psychophysiological consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic: an extensive literature review. Front. Psychol. 11, 580225. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.580225 (2020).

Kotini-Shah, P. et al. Work–life balance and productivity among academic faculty during the COVID-19 pandemic: A latent class analysis. J. Womens Health. 31, 321–330. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2021.0277 (2022).

Wurpts, I. C. & Geiser, C. Is adding more indicators to a latent class analysis beneficial or detrimental? Results of a Monte-Carlo study. Front. Psychol. 5, 920. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00920 (2014).

Chang, S. J. Stress. In Standardization of health statistics data collection and measurement (ed. The Korean Society for Preventive Medicine) 99–143 (Gyechuk Munhwasa, 2000).

Jung, M. H. & Choi, E. H. Factors associated with workplace infection prevention behaviors among workers in small-sized enterprises: during the early COVID-19 pandemic. Korean J. Occup. Health. 6, 173–184. https://doi.org/10.35861/KJOH.2024.6.3.173 (2024).

Kim, M. J. A Study of the Factors for Invigoration of Flexible Work Arrangements in Public Sector. Master’s thesis, University of Seoul (2017).

Vermunt, J. K. & Magidson, J. Latent class cluster analysis. In Applied Latent Class Analysis (eds Hagenaars, J. & McCutcheon, A.) 89–106 (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

Kim, S. Y. & Hong, S. H. Identifying and predicting trajectories of latent classes in adolescents’ suicidal ideation. Stud. Korean Youth. 23, 251–275 (2012). https://www.dbpia.co.kr/journal/articleDetail?nodeId=NODE01793747

Kim, J. G. Effect of Police officer’s work-life balance on depression and anxiety. J. Korean Soc. Priv. Secur. 20, 57–82. https://doi.org/10.56603/jksps.2021.20.4.57 (2021).

Williams, S. N., Armitage, C. J., Tampe, T. & Dienes, K. Public perceptions and experiences of social distancing and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic: a UK-based focus group study. BMJ Open. 10, e039334. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039334 (2020).

Cheng, J., Sun, X., Zhong, Y. & Li, K. Flexible work arrangements and employees’ knowledge sharing in post-pandemic era: the roles of workplace loneliness and task interdependence. Behav. Sci. 13, 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13020168 (2023).

Bjärntoft, S., Hallman, D. M., Mathiassen, S. E., Larsson, J. & Jahncke, H. Occupational and individual determinants of work-life balance among office workers with flexible work arrangements. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 17, 1418. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041418 (2020).

Park, S. J. Flexible work schedule as a strategy realizing work-life balance in local governments. Korean Local. Gov. Rev. 14, 49–75 (2012).

Kardas, J. S. Job crafting and work–life balance in a mature organization. Sustainability 15, 16089. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152216089 (2023).

Ryu, H. U. The impact of the implementation of flexible working hour systems on the labor costs of SMEs. J. SME Policy. 8, 147–184 (2023).

Jee, S. H. Use and change of the flexible work system of regular and non-regular workers as viewed by the supplementary survey of the economically active population survey. Labor Rev. 66–76 (2021).

Peschl, A., Altun, U. & Conrad, R. W. Developing an analysis tool to identify potentials for mobile, time-flexible work in production: results from the MofAPro research project. Work 72, 1521–1534. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-211263 (2022).

Wolf, M. P. COVID-19 and remote work inequality: evidence from South Korea. Labor Hist. 63, 406–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/0023656x.2022.2111549 (2022).

Kimhi, S., Marciano, H., Eshel, Y. & Adini, B. Resilience and demographic characteristics predicting distress during the COVID-19 crisis. Soc. Sci. Med. 265, 113389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113389 (2020).

Quinn, E. L., Stover, B., Otten, J. J. & Seixas, N. Early care and education workers’ experience and stress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 2670. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052670 (2022).

Heinen, A., Varghese, S., Krayem, A. & Molodynski, A. Understanding health anxiety in the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 68, 1756–1763. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207640211057794 (2022).

Brussevich, M. Who bears the Brunt of lockdown policies? Evidence from tele-workability measures across countries. IMF Econ. Rev. 70, 560–589. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41308-022-00165-9 (2022).

Tokson, M., Rahrig, H. & Green, J. D. Disease-preventive behaviors and subjective well-being in the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychol. 11, 265. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01316-x (2023).

Gómez-Salgado, J. et al. Use of preventive measures, beliefs and information received about COVID-19 and their effects on mental health, in two stages of the pandemic in Colombia. Ann. Med. 54, 2246–2258. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2022.2109057 (2022).

Vázquez-Martínez, U. J., Morales-Mediano, J. & Leal-Rodríguez, A. L. The impact of the COVID-19 crisis on consumer purchasing motivation and behavior. Eur. Res. Manag Bus. Econ. 27, 100166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iedeen.2021.100166 (2021).

Ihm, J. & Lee, C. Communication networks and individual resilience for individual well-being during a time of crisis. Health Commun. 38, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2022.2141041 (2022).

Pacheco, T. et al. Job security and the promotion of workers’ wellbeing in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic: a study with Canadian workers one to two weeks after the initiation of social distancing measures. Int. J. Wellbeing. 10, 58–76. https://doi.org/10.5502/IJW.V10I3.1321 (2020).

Mullens, F. & Laurijssen, I. An organizational working time reduction and its impact on three domains of mental well-being of employees: a panel study. BMC Public. Health. 24, 526. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19161-x (2024).

Go, B. C. & Bang, J. H. Died after working 62 hours… "The last time I saw him was when he was packing his duvet." The Hankyoreh (2023). https://www.hani.co.kr/arti/society/society_general/1083281.html

Lee, J. M. & Hong, G. H. A study on the effects of the 52-hour workweek policy on wages, employment and employment type. J. Korean Econ. Stud. 39, 35–65. https://doi.org/10.46665/jkes.2021.09.39.3.35 (2021).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. NRF-2020R1C1C1013808).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.S.L. and E.H.C. conceived the ideas; S.S.L. and E.H.C. collected the data; S.S.L. and E.H.C. analysed the data; S.S.L. and E.H.C wrote the draft; E.H.C. and S.M.C revised the article; and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, SS., Cho, Sm. & Choi, EH. Latent class patterns of work-life balance changes among Korean SME workers during COVID-19 based on organizational support and psychosocial health. Sci Rep 16, 119 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29001-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29001-6