Abstract

Evaluating the effects of personalized strength training on isokinetic muscle strength and balance ability in fencers with chronic ankle instability (CAI), focusing on functional outcomes and rehabilitation efficacy. Twenty-one fencers with CAI were randomly assigned to three groups: a control group (CG, n = 7), a standardized strength training group (SG, n = 7), and a personalized strength training group (PG, n = 7). During the six-week intervention, training sessions were performed three times per week. Isokinetic muscle strength was assessed at 30°/s and 120°/s with concentric and eccentric ankle eversion. Balance ability was measured using the single-leg stance (with eyes open and closed) and Y-balance tests. Functional performance was evaluated using the Cumberland Ankle Instability Tool (CAIT). The personalized strength training group presented significant improvements in eccentric eversion peak torques at 30°/s (p < 0.001) and 120°/s (p = 0.004) and the dynamic control ratio (DCR) at 30°/s (p = 0.001) and 120°/s (p = 0.012). In terms of balance ability, this group demonstrated apparent improvements in the single-leg stance test with eyes closed (p = 0.000) and a trend toward improvement in dynamic balance in the Y-balance test. Additionally, this group showed a highly significant increase in CAIT scores (p < 0.001), indicating enhanced functional stability. By comparison, no evident improvements were observed in the control and standardized strength training groups. Personalized strength training is more effective than standardized programs in improving isokinetic muscle strength, balance ability, and functional stability in fencers with CAI. The findings suggest that incorporating personalized strength training into rehabilitation protocols can enhance recovery efficiency and injury prevention among athletes with CAI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic ankle instability (CAI) is prevalent among athletes, particularly those involved in sports that require rapid lateral movements, such as fencing. CAI is characterized by recurrent episodes of the ankle “giving way,” persistent discomfort, and impaired balance ability1. These symptoms often result from inadequate rehabilitation following an ankle sprain, leading to long-term functional deficits and an increased risk of re-injury2. In sports like fencing, where quick footwork and directional changes are integral to performance3, CAI can profoundly decrease athletic efficiency, impair performance, and elevate the risk of recurrent injuries.

Fencing imposes strict demands on the lower limbs due to its explosive and dynamic movements. Fencers constantly engage in sudden lunges, directional shifts, and repetitive weight-bearing motions4, all of which place considerable stress on the ankle joint and threaten long-term joint health. However, the prevalence of CAI among fencers is often underreported. Addressing CAI in fencers is essential to enhance their athletic performance and prevent joint injuries and further deterioration.

Strength training is a commonly used fundamental intervention for improving the stability and functional performance of athletes with CAI5. By strengthening neuromuscular control around the ankle joint, strengthtraining facilitates maintaining joint stability during dynamic movements. Numerous studies have demonstrated that strength exercises focusing on the muscles surrounding the ankle can efficiently promote balance ability, proprioception, and overall joint control 6,7,8,9. However, research addressing fencers with CAI remains limited. Traditional strength training programs often fail to account for the specific footwork and movement patterns inherent in fencing, potentially constraining their effectiveness for fencers with CAI.

Given the distinct features of fencing, it is hypothesized that strength training programs tailored to the biomechanics of fencing can significantly improve ankle stability. Exercises designed to simulate fencing-specific movements can better prepare athletes for the stresses encountered during competition10. Additionally, personalized strength training can address specific deficiencies of individuals in muscle strength, proprioception, and joint mobility, which may contribute to ankle injury. In other sports such as basketball and running, personalized training programs have been shown to yield superior improvements in joint stability and functional performance compared to standardized regimens, particularly when tailored to individual neuromuscular deficits or sport-specific demands11,12. However, this comparative approach remains underexplored in the context of fencing athletes with CAI.

Although previous studies have demonstrated that strength training improves neuromuscular control and joint stability in individuals with chronic ankle instability (CAI), most have focused on generalized or standardized training protocols without tailoring them to sport-specific demands. In particular, few studies have systematically compared the effects of personalized versus standardized strength training on CAI rehabilitation outcomes. Moreover, fencing athletes are rarely addressed in these studies, despite their unique footwork patterns and high lower limb demands. Therefore, this study bridges this gap by developing a fencing-specific personalized strength training program and evaluating its comparative efficacy against a standardized protocol. The novelty of this research lies in its dual focus on sport-specific personalization and comparative intervention design, offering new insights into optimizing rehabilitation strategies for athletes with CAI.

This study developed a specific strength training program targeting fencers with CAI and evaluated its effectiveness by comparing three groups of fencers with CAI: one undergoing a standardized strength training regimen, another receiving a fencing-specific strength training program, and a control group without intervention. The primary outcome measure included isokinetic strength test results, assessing the impact of the fencing-specific strength training program on ankle stability. Additionally, isokinetic strength testing was employed to quantify ankle evertor muscle performance, which is closely associated with joint stability in individuals with CAI. Although this study did not aim to validate isokinetic testing as a diagnostic tool, the results may contribute to the ongoing discussion regarding its utility in assessing ankle function in athletic populations. The findings provide valuable insights into injury prevention and performance optimization among athletes.

Materials and methods

Participants

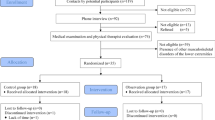

To estimate the appropriate sample size, a power analysis was conducted prior to the study using G*Power 3.1. The α level was set a priori at P = 0.05, and statistical power was set at 80%. An effect size of 0.25 was determined based on Cohen’s conventional criteria for a medium effect size (Cohen, 1988). The analysis indicated that a minimum of 21 participants would provide sufficient power. Twenty-one competitive fencers with CAI were recruited from the Beijing fencing team (see Table 1 for participant demographics). They are randomly assigned to three groups: a control group (CG, n = 7), a standardized strength training group (SG, n = 7), and a personalized strength training group (PG, n = 7) according to a computer-generated randomization list (Fig. 1). The inclusion criteria were as follows: having CAI defined by the International Ankle Consortium13, a history of at least one significant ankle sprain, and the first sprain occurring at least 12 months prior to the study. The initial injury must have resulted in clinical symptoms, such as pain and swelling, leading to at least one day of interrupted physical activity. Additionally, participants should have experienced at least two episodes of the ankle “giving way” or feeling unstable in the past six months, with the most recent sprain occurring more than three months before the study. They also should have a Cumberland Ankle Instability Tool (CAIT) score of less than 24, indicating CAI14. Exclusion criteria included a history of fractures or other medical conditions affecting lower limb function, any acute musculoskeletal injury to the lower limb joints within the past three months that compromised joint integrity or function and led to at least one day of interrupted physical activity, as well as any acute ankle sprain within the past six weeks. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Research Institute of Sports Science (Ethical Approval No. TKSLL202309), aligning with the ethical guidelines enumerated in the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants were fully informed of the potential risks and benefits of the study and provided written informed consent before engaging in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the legal guardians of all minor participants.

Study protocol

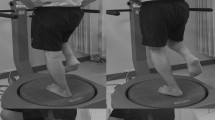

The study lasted six weeks. Separate training protocols for each group were conducted three times per week7. The CG group underwent a regular fencing training regimen without any additional strength interventions. The athletes in the control group trained for 8 h a day, six days a week, including fencing-specific training and physical training. In contrast, the SG group followed a standardized strength training protocol based on 7, which involved resistance exercises using a Thera-Band. The Thera-Band was secured to a heavy chair and stretched to 170% of its resting length during training. Participants in the SG group placed their feet in the band and performed both concentric and eccentric ankle eversion exercises. The resistance level was determined by the color of the Thera-Band, with blue, black, and silver corresponding to progressively higher resistance levels. Each set consisted of ten repetitions, and participants performed three to four sets per session. The resistance was progressively increased every two weeks according to the training plan outlined in Table 2.

The PG group used elastic bands for training, and used a portable spring scale to pull each athlete to 50%, 60% or 70% MVIC (Table 3) as the training load for ankle eversion. 50% MVIC was used for 20 times, 60% MVIC was used for 15 times, and 70% MVIC was used for 12 times, for a total of 3–4 sets. The athletes performed concentric and eccentric strength training for ankle eversion under this load. Elastic band strength training was performed 3 times a week, and the difficulty was advanced after every 6 times, with each training load advanced by 10%. The intervention training lasted for 6 weeks15, with a total of 18 interventions.

The study was conducted under standardized conditions. All participants were closely monitored throughout the study and were encouraged to report any discomfort or injuries during training. The training programs designed for the SG and PG groups provided progressive overload in a controlled manner, encompassing both concentric and eccentric muscle actions targeting ankle eversion strength. The effects of standardized and personalized training programs on improving ankle stability among fencers with CAI were compared and analyzed.

Isokinetic strength test

Isokinetic strength testing was conducted using the ISOMED 2000 system, a validated assessment tool for muscular strength and endurance at constant angular velocities. Prior to testing, all participants completed a thorough warm-up, focusing on the lower limbs and ankle joints through movements in multiple planes to minimize injury risk. During the test, participants were seated with their hips flexed at 80° (with 0° representing the neutral position). Ankle varus/valgus: valgus 20°~varus 25°, full range 45°. Their thighs were stabilized with accessories. The lower legs were positioned horizontally. The knee joints were secured at the distal femur to restrict movement and maintain consistent testing conditions. The feet were fastened to the footplate of the device16.Testing was performed 3 days after the 6-week training intervention to prevent athlete fatigue and avoid training time.

The subjects should first performed a thorough warm-up, especially the activities activation of the lower limbs, elastic band resistance strength training activation in all ankle directions. Then, the participants finished 2–3 practice trials to familiarize themselves with the procedure. Test the concentric and eccentric strength of ankle inversion and eversion at 30°/s and 120°/s angular velocity. 5 tests were completed at 30°/s angular velocity and 15 tests were completed at 120°/s angular velocity. Peak torque is used for analysis. Verbal encouragement was provided throughout the test to maximize effort, which was in line with research showing that such encouragement enhances performance outcomes17. The test would be immediately halted in cases of any reported discomfort or pain to avoid exacerbating any underlying conditions.

Static balance test

Static balance was assessed using the FreeMed® pressure plate system (Sensor Medica, Italy), which provides precise measurements of plantar pressure distribution and balance metrics (with a sampling frequency of 400 Hz and a resolution of 2.5 dpi). The participants were required to maintain a single-leg stance on the center of the pressure plate while gazing straight ahead by hands on hips. Data were collected for 30 s under two conditions: eyes open and closed. First, participants balanced on one leg with the other elevated and then switched the legs after completing the one-side trial. This approach can evaluate both visual and proprioceptive contributions to balance control18. During the analysis, Sphere Length (mm) was calculated to represent the total displacement of the center of pressure (COP) throughout the trial, reflecting the overall amount of postural sway. Ellipse Area (mm²) was defined as the 95% confidence ellipse that encompasses the COP trajectory, indicating the spatial extent of sway. In both cases, higher values indicate poorer balance performance, whereas lower values suggest better postural stability.

Dynamic balance test

Dynamic balance was examined using the Y-Balance Test, a well-established tool for assessing lower extremity reach distances in three directions: anterior, posteromedial, and posterolateral19. Prior to testing, the limb length from the anterior superior iliac spine to the medial malleolus of participants was measured. Limb length was measured from the anterior superior iliac spine to the medial malleolus to normalize the reach distances in each direction. This normalization accounts for individual anthropometric differences and allows for more accurate comparisons of dynamic balance performance. Each participant stood on the central platform with one foot while using the opposite one to push the indicator board as far as possible in designated directions. For test validity, participants were required to maintain consistent contact with the board and return to the starting position in a controlled manner19. The trial was repeated in each direction, recording the farthest distance in that direction for subsequent analysis.

Maximal voluntary isometric contraction (MVIC) test

The MVIC test of the ankle evertor muscles was assessed using the Hoggan microFET2 portable dynamometer. Its accuracy in measuring isometric force has been validated. Participants were positioned supine on a treatment table with their legs extended. The dynamometer was placed against the lateral aspect of their feet. Then, participants were instructed to evert one ankle with maximal force for five seconds under the resistance of the tester. The medial ankle was manually secured to prevent compensatory movements. The trial was repeated three times, recording the highest force for analysis.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS (version 26.0, IBM Corporation). Descriptive statistics were presented as means and standard deviations (SD), with a significance level of P < 0.05 and a highly significant level of P < 0.01. A 2 × 3 repeated measures ANOVA was employed to assess intervention effects. The first independent variable (within subjects) was time (pre-test vs. post-test), and the second one (between subjects) was the intervention type (no intervention, standardized strength training, and personalized strength training). Dependent variables included isokinetic ankle eversion strength, static and dynamic balance measures, CAIT scores, and other related performance metrics.

Results

All the participants completed this study, and the data obtained from them were used in the analysis. All the data were normally distributed. There was no significant difference in the demographic characteristics, the outcomes of strength and power, and performance between groups (p > 0.05). Tables 3, 4 and 5; Fig. 2 presents the descriptive statistics of all tests, results of repeated ANOVA for pre-and post-training fitness testing, and corresponding ESs.

Isokinetic strength test results

As shown in Table s1, repeated measures ANOVA indicated no significant differences in the 30°/s concentric eversion peak torque in the main effects of time, intervention type, and their interaction. However, the 30°/s eccentric eversion peak torque presented a significant main effect of time (F(1,18) = 8.795, p = 0.008, η²p = 0.328) and a significant time × intervention interaction (F(2,18) = 10.668, p = 0.001, η²p = 0.542). Simple effect analysis (Table 4) revealed that the personalized strength training group had a highly significant improvement after training (p < 0.001), while no significant differences were observed in the control and standardized strength training groups.

Regarding the 120°/s concentric eversion peak torque, neither the main effect of time, the main effect of the intervention, nor the time × intervention interaction was significant. In contrast, the 120°/s eccentric eversion peak torque exhibited a significant time × intervention interaction (F(2,18) = 4.425, p = 0.027, η²p = 0.330). Simple effect analysis showed a significant improvement in the personalized strength training group after training (p = 0.004, p < 0.01), whereas no significant differences were observed in the control and standardized strength training groups.

Under a dynamic control ratio (DCR) at 30°/s, there was a significant time × intervention interaction (F(2,18) = 7.626, p = 0.004, η²p = 0.459). Simple effect analysis demonstrated a significant improvement in the personalized strength training group post-tests (p = 0.001, p < 0.01), while no significant differences were found in the control and standardized strength training groups. In terms of the DCR at 120°/s, although no significant main effects or interaction effects were observed, simple effect analysis showed a significant improvement in the personalized strength training group after training (p = 0.012, p < 0.05).

Balance test results

For the single-leg stance test with eyes open, no significant time × intervention interaction effects were found for the following variables: sphere length, ellipse area, and average speed (see Table S2). Similarly, no significant main effect of time or intervention was observed for these parameters. However, there was a significant main effect of intervention on the average X coordinate (F(2,18) = 4.097, p = 0.034, η2p= 0.313) and a significant time × intervention interaction effect on the average Y coordinate (F(2,18) = 4.652, p = 0.024, η2p = 0.341). Simple effect analysis (Table 5) revealed a significant improvement in the average Y coordinate only in the control group from pre- to post-test (p = 0.035).

For the single-leg stance test with eyes closed, significant main effects of time were observed for sphere length (F(1,18) = 19.413, p = 0.000, η2p= 0.519) and ellipse area (F(1,18) = 4.812, p = 0.042, η2p= 0.211), indicating an overall improvement in postural control across groups. However, no significant main effect of intervention was found. A significant time × intervention interaction was found only for the average X coordinate (F(2,18) = 3.759, p = 0.043, η2p = 0.295). Simple effect analysis (Table S2) showed a highly significant improvement in the personalized training group (p = 0.005), and a significant difference between the control and standardized groups at post-test (p = 0.038).

Regarding the Y-balance test, no significant interaction effects or main effects were found in any of the three reach directions (anterior, posteromedial, and posterolateral) (see Table S3). Simple effect analysis (Table 6) indicates that neither training group showed statistically significant improvement in dynamic balance over time compared to the control group.

CAIT results

As shown in Table s4, repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of time (F(1,18) = 7.571, p = 0.013, η2p = 0.296) but no significant main effect of intervention. However, a significant time × intervention interaction was detected (F(2,18) = 13.945, p = 0.000, η2p = 0.608). Simple effect analysis (Table 7) demonstrated a highly significant improvement in CAIT scores in the personalized strength training group after training (p = 0.000, p < 0.001). Additionally, post-test results indicated significant differences between the personalized strength training group and the control group (p = 0.005, p < 0.01).

Discussion

The findings of this study imply that personalized strength training significantly improves ankle stability in fencers with CAI, while standardized strength training offers less pronounced benefits. The results of the isokinetic strength test revealed that the personalized strength training group exhibited significant improvements in both eccentric and concentric eversion peak torques at various speeds, particularly at 30°/s and 120°/s, verifying the efficacy of tailored strength training. Conversely, no significant improvements were observed in the control and standardized strength training groups, underscoring the importance of customizing rehabilitation programs to address the biomechanical demands of specific sports like fencing.

Comparison of strength improvements

In the isokinetic strength test, the personalized training group demonstrated highly significant improvements in eccentric eversion strength at 30°/s (p < 0.001). This is crucial for preventing lateral ankle sprains, which commonly occur during rapid movements such as lunges and directional changes in fencing. These findings align with previous research, suggesting that eccentric strength is pivotal in stabilizing the ankle during dynamic movements20. Despite the fact that both the control and standardized strength training groups also underwent strength exercises, the lack of significant improvements in the two groups indicates that generic training programs may be inadequate for athletes with CAI, particularly in sports that impose high demands on the lower limbs.

The DCR results further validate these findings. At both 30°/s and 120°/s, significant improvements were noted in the personalized strength training group. This suggests that personalized strength training not only enhances isokinetic muscle strength but also improves neuromuscular control. Reinforced neuromuscular control is particularly beneficial for maintaining joint stability during complex movements and preventing the “giving way” phenomenon commonly reported among athletes with CAI21.

These findings are generally consistent with prior studies on CAI rehabilitation, but with some notable distinctions. Hall et al. (2015) implemented a six-week standardized strength training protocol and reported moderate increases in eccentric eversion torque in individuals with CAI, but the magnitude of improvement was relatively limited due to uniform loading schemes and a lack of sport specificity15. Similarly, Wright et al. (2017) observed functional improvements following combined strength and balance training, yet the effect sizes for eccentric strength changes were modest and not significantly superior to control conditions12. Compared to these studies, our intervention led to more substantial gains in eccentric strength, particularly at slower velocities (30°/s), which may be attributed to the personalized nature of the program.

Specifically, our use of progressive loading based on percentage MVIC, combined with sport-specific movement patterns reflective of fencing footwork and ankle mechanics, may have provided a more targeted neuromuscular stimulus. The greater training specificity and individualization likely enhanced muscle recruitment efficiency and neuromuscular adaptation. Therefore, the superior performance outcomes observed in the personalized strength group underscore the importance of tailoring rehabilitation not only to the general condition (CAI) but also to the sport-specific biomechanical context of the athlete. While isokinetic strength testing provided detailed information about the improvements in ankle evertor torque and DCR, it was not intended as a diagnostic method for identifying CAI in this study. Future studies may explore its potential utility as a supportive assessment tool when combined with functional or subjective measures like the CAIT.

Balance and functional outcomes

The results of the single-leg stance and Y-balance tests showed that personalized strength training positively impacted the balance ability of fencers with CAI. Particularly, in the single-leg stance with eyes closed, an exercise that heavily relies on proprioception, the personalized strength training group exhibited significant improvements in balance. The remarkable reduction in sphere length and ellipse area in the personalized strength training group represents improved postural control, which is contributed to the enhanced proprioceptive from the targeted training. This improvement is critical, as proprioceptive deficits are a hallmark of CAI and can induce re-injury22.

Furthermore, although the Y-balance test results did not reach statistical significance in any direction, a slight improvement was observed in the personalized strength training group. Several possible reasons may explain the lack of statistical significance. First, the short intervention duration (six weeks) may not have been sufficient to elicit measurable changes in dynamic balance, particularly in highly trained athletes who already possess a relatively high baseline level of balance ability. Second, the Y-balance test is a complex assessment involving not only ankle stability but also coordination across the hip, knee, and trunk. Since our intervention focused specifically on ankle eversion strength, the transfer effects to global dynamic balance performance may have been limited. Finally, the small sample size (n = 7 per group) could reduce the statistical power to detect moderate improvements23. Nevertheless, the directional trends in the personalized strength group are consistent with previous studies suggesting that combining proprioceptive and strength training may positively influence dynamic stability over longer durations or with sport-specific balance tasks.

CAIT score and functional improvement

The CAIT scores provided strong evidence of functional improvement in the personalized strength training group24. Post-training scores showed a significant increase in this group compared to both the control and standardized strength training groups (p < 0.01). This improvement implies a substantial reduction in the perception of ankle instability and an enhancement in functional performance, which is critical for athletes in sports requiring high levels of agility and stability, such as fencing.

These results underscore the importance of tailored strength training in rehabilitative programs for CAI. While generalized strength training may offer some benefits, it fails to address the specific biomechanical challenges and proprioceptive needs of athletes in high-demand sports. The significant interaction effects observed in this study emphasize that a one-size-fits-all approach is insufficient, and training programs should be tailored to the distinctive demands of sports and individuals.

Notably, the post-training CAIT score in the personalized training group (24.71 ± 1.80) exceeded the commonly accepted clinical threshold of 24 for diagnosing chronic ankle instability, as recommended by the International Ankle Consortium13. This suggests a clinically meaningful improvement in perceived ankle stability and a potential resolution of functional symptoms.

Limitations and future research

First, the sample size is relatively small, which may limit the generalizability of this study. Second, while isokinetic strength testing and balance assessments provide valuable insights into neuromuscular control and functional stability, evaluation of other factors, such as joint range of motion and muscle endurance, was lacking. Future research should incorporate these additional parameters and investigate their effects on mitigating the risk of recurrent ankle sprains.

Moreover, long-term follow-up studies are essential to assess whether personalized strength training has sustained impacts on protecting against ankle re-injury. Additionally, a crucial direction in future research is the effect of including sport-specific drills, such as fencing footwork exercises, on enhancing functional outcomes of rehabilitation programs.

In addition to these limitations, several potential confounding factors should be considered. Although training was conducted under standardized supervision, subtle differences in supervision quality and participant adherence may have influenced training intensity or consistency. Furthermore, although participants were all competitive fencers with CAI, Table 1 shows noticeable variation in training experience (ranging from 6.0 to 7.4 years), which may affect baseline neuromuscular capacity and adaptability. Future studies should consider stratifying participants based on training age or pre-intervention performance to further reduce variability and clarify intervention effects.

Conclusion

This study explored the effectiveness of personalized strength training in improving isokinetic muscle strength, balance ability, and functional performance among fencers with CAI. Personalized interventions that account for the specific biomechanical demands of fencing and the individual deficits of athletes were demonstrated to be more effective than standardized programs in enhancing ankle stability. These findings suggest that personalized strength training should be incorporated into rehabilitation and injury prevention programs as a key component for athletes with CAI, particularly those engaged in high-risk sports like fencing.

Future research should expand on these findings by exploring longer intervention durations, larger and more diverse athlete samples, and the integration of sport-specific drills such as fencing footwork into training protocols. In practice, strength and conditioning professionals may consider adopting load-calibrated, individualized training strategies that combine eccentric strength development with proprioceptive stimulation to maximize functional recovery and minimize reinjury risks. Establishing standardized guidelines for implementing personalized rehabilitation in different sports contexts will be an important step toward translating these findings into broader clinical and athletic settings.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

References

Miklovic, T. M., Donovan, L., Protzuk, O. A., Kang, M. S. & Feger, M. A. Acute lateral ankle sprain to chronic ankle instability: a pathway of dysfunction. Physician Sportsmed. 2018/01/02 (1), 116–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913847.2018.1409604 (2018).

Biz, C. et al. Is Kinesio taping effective for sport performance and ankle function of athletes with chronic ankle instability (CAI)? A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina 58 (5). https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58050620 (2022).

Plantard, P., Sorel, A., Bideau, N. & Pontonnier, C. Motion adaptation in fencing lunges: a pilot study. Comput. Methods Biomech. BioMed. Eng. 20 (sup1), S161–S162. https://doi.org/10.1080/10255842.2017.1382912 (2017).

Chen, T. L. W. et al. Biomechanics of fencing sport: A scoping review. PLOS ONE. 12 (2), e0171578. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0171578 (2017).

Hall, E. A., Docherty, C. L., Simon, J., Kingma, J. J. & Klossner, J. C. Strength-training protocols to improve deficits in participants with chronic ankle instability: a randomized controlled trial. J.Athl.Train. 50 (1), 36–44. https://doi.org/10.4085/1062-6050-49.3.71 (2015).

Smith, B. I., Docherty, C. L., Simon, J., Klossner, J. & Schrader, J. Ankle strength and force sense after a progressive, 6-week strength-training program in people with functional ankle instability. J. Athl. Train. 47 (3), 282–288. https://doi.org/10.4085/1062-6050-47.3.06 (2012).

Docherty, C. L., Moore, J. H. & Arnold, B. L. Effects of strength training on strength development and joint position sense in functionally unstable ankles. J. Athl. Train 33 (4), 310–314 (1998).

Wright, C. J., Linens, S. W. & Cain, M. S. A randomized controlled trial comparing rehabilitation efficacy in chronic ankle instability. J. Sport Rehabil.. 26 (4), 238–249. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsr.2015-0189 (2017).

Kim, K. J. et al. Which treatment is more effective for functional ankle instability: strengthening or combined muscle strengthening and proprioceptive exercises? J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 26 (3), 385–388. https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.26.385 (2014).

Bocharov, M., Korobeynikov, G., Kryventsova, I., Klymenchenko, V. & Vypasniak, I. The individualization of the educational and training process in fencing in the context of improving efficiency and health of young athletes of different ages. Pedagogy Health (2024).

Kim, K. J. et al. Which treatment is more effective for functional ankle instability: strengthening or combined muscle strengthening and proprioceptive exercises? J. Phys. Therapy Sci. 26 (3), 385–388 (2014).

Wright, C. J., Linens, S. W. & Cain, M. S. A randomized controlled trial comparing rehabilitation efficacy in chronic ankle instability. J. Sport Rehabil.. 26 (4), 238–249. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsr.2015-0189 (2017).

Gribble, P. A. et al. Selection criteria for patients with chronic ankle instability in controlled research: A position statement of the international ankle consortium. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Therapy. 43 (8), 585–591. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2013.0303 (2013). 2013/08/01.

Li, Y. et al. Applicability of cutoff scores of Chinese Cumberland ankle instability tool and foot and ankle ability measure as inclusion criteria for study of chronic ankle instability in Chinese individuals. Phys. Ther. Sport 48, 116–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ptsp.2020.12.021 (2021).

Hall, E. A., Docherty, C. L., Simon, J., Kingma, J. J. & Klossner, J. C. Strength-training protocols to improve deficits in participants with chronic ankle instability: a randomized controlled trial. J. Athlete Train.. 50 (1), 36–44. https://doi.org/10.4085/1062-6050-49.3.71 (2015).

David, P., Halimi, M., Mora, I., Doutrellot, P-L. & Petitjean, M. Dec. Isokinetic Testing of Evertor and Invertor Muscles in Patients With Chronic Ankle Instability. J. Appl. Biomech.. 01 2013;29(6):696–704. (2013). https://doi.org/10.1123/jab.29.6.696

Midgley, A. W., Marchant, D. C. & Levy, A. R. A call to action towards an evidence-based approach to using verbal encouragement during maximal exercise testing. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging. 38 (4), 547–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpf.12454 (2018).

Hazime, F. A. et al. Postural control under visual and proprioceptive perturbations during double and single limb stances: insights for balance training. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther.. 16 (2), 224–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2011.02.003 (2012).

Plisky, P. J. et al. The reliability of an instrumented device for measuring components of the star excursion balance test. N. Am. J. Sports Phys. Ther.. 4 (2), 92–99 (2009).

Park, D-J., Kim, B-J., Kim, Y-H. & Park, S-Y. A three-week intervention emphasized diagonal eccentric contraction on balance and joint position sense and ankle strength in subjects with ankle instability: A randomized controlled trial. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. (2020).

Donovan, L. & Hertel, J. A New Paradigm for Rehabilitation of Patients with Chronic Ankle Instability. Phys. Sportsmed.. https://doi.org/10.3810/psm.2012.11.1987 (2012).

Alghadir, A. H., Iqbal, Z. A., Iqbal, A., Ahmed, H. & Ramteke, S. U. Effect of chronic ankle sprain on Pain, range of Motion, Proprioception, and balance among athletes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 17 (15). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155318 (2020).

Alahmari, K. A. et al. Combined effects of strengthening and proprioceptive training on Stability, Balance, and proprioception among subjects with chronic ankle instability in different age groups: evaluation of clinical outcome measures. Indian J. Orthop. 55 (1), 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43465-020-00192-6 (2021).

Guo, Y. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of balance training in patients with chronic ankle instability. Systematic Rev.13(1):64. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-024-02455-x (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Liping Liao, Lingzhi He and JianWu Xu wrote the main manuscript text and Wantong Zhao , Meng Liu prepared Figs. 1 and 2. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liao, L., He, L., Zhao, W. et al. Effects of personalized strength training on isokinetic muscle strength and balance ability among fencers with chronic ankle instability. Sci Rep 16, 15 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29291-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29291-w