Abstract

Rural areas worldwide face unprecedented challenges from rapid urbanization, necessitating transformative development pathways to rural revitalization. Here, we present a theoretical framework positioning new quality productivity (NQP)—a productivity paradigm driven by innovation—as a promising lever for rural revitalization. Using panel data from 282 cities in China spanning 2010–2021, we construct fixed effects models and two-stage least squares models to examine NQP’s causal impact on rural revitalization outcomes. Our analysis reveals that NQP significantly enhances rural revitalization with lasting effects. Moderating effect models demonstrate that NQP’s impact is more pronounced in economically developed eastern regions and under stronger government support. Spatial econometric models uncover substantial positive spillover effects extending to both geographically and economically proximate cities. These findings underscore the importance of tailoring NQP to local conditions, enhancing government guidance, and fostering cross-regional collaboration. Our study provides a systematic framework and robust evidence for the penetration of innovation-driven productivity into rural areas, offering actionable insights for public policies aimed at fostering sustainable rural development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rural decline has emerged as an indisputable global phenomenon accompanying urbanization, industrialization, and knowledge economy transitions. Countries including the United States, Canada, Southern Europe, Australia, China, and Japan have either experienced or are experiencing rural decline1,2. Agricultural-based and geographically remote rural areas are particularly vulnerable, inevitably experiencing depopulation, population aging3, economic recession, infrastructure deterioration2, food insecurity4, and ecological degradation5. Yet, rural areas remain indispensable for global sustainable development, harboring extensive biodiversity6, producing the vast majority of global food supplies7, and serving as crucial carbon sinks8. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have established a comprehensive framework calling for equitable poverty reduction (SDG 1), zero hunger (SDG 2), inclusive economic growth (SDG 8), and ecosystem restoration (SDG 15) to support rural revitalization. The OECD’s New Rural Development Paradigm emphasizes the need for innovation-driven approaches that integrate investment, infusion, and institutional capacity building to implement these sustainable rural development objectives9.

As a country experiencing the world’s largest and fastest urbanization process, China has seen over 280 million rural residents migrate to cities in the past two decades (National Bureau of Statistics10. This rapid transformation has intensified rural hollowing—characterized by population outflow, land abandonment, service contraction, cultural loss, and environmental degradation11,12,13—while widening urban-rural development gaps due to the dual urban-rural system14. Acknowledging that rural areas pose the greatest challenge to modernization, the nation has launched the rural revitalization strategy as a comprehensive national initiative that stands unparalleled globally in both scale and ambition.

Addressing rural challenges fundamentally requires transforming productivity as the foundation of all social and economic development15. Building upon Karl Marx’s view of technology shaping productivity and endogenous growth theory regarding endogenous factors such as knowledge accumulation and technological innovation as drivers of productivity enhancement, China has developed new quality productivity (NQP)—an innovation-driven advanced productivity characterized by high technology, high efficiency, and high quality16. This concept integrates global advanced concepts: NQP’s utilization of automation, digitalization, and intelligent equipment aligns with Industry 4.0 trends17, while its emphasis on efficiency enhancement and resource conservation resonates with green productivity’s focus on sustainable production capacity18 and sustainable productivity’s pursuit of human-ecological coordination19. While over 70% of productivity literature focuses on urban contexts, particularly industrial upgrading20, ecological resilience21, carbon emission reduction22, environmental innovation23, and corporate ESG performance24, rural areas have a more pressing need to transform their outdated productivity. Recent studies have proposed formation models for agricultural NQP25, identified rural NQP implementation challenges26, explored new approaches for NQP to promote rural green development27, and demonstrated productivity’s rural poverty effects28. Despite these important contributions, existing research often addresses specific rural aspects rather than providing systematic understanding and empirical examination of NQP’s role in comprehensive rural revitalization. Moreover, innovation activities such as patents and knowledge exhibit mobility and thus generate potential positive spatial spillover effects29,30. However, whether innovation-driven productivity enhancement exhibits spillover effects in rural areas through geographic and economic proximity—and their relative magnitudes—remains empirically unverified.

To fill these gaps, this study aims to reveal the impact of NQP on rural revitalization through both theoretical and empirical analysis. Theoretically, we incorporate the NQP system composed of three elemental components and the rural revitalization system oriented toward five overarching goals into a unified analytical framework, and systematically clarifies the logical mechanism of NQP’s impact on rural revitalization from a novel spatial perspective. Empirically, we analyze panel data from 282 cities in China from 2010 to 2021 using fixed effects models, two-stage least squares models, moderating effect models, and spatial econometric models to test NQP’s direct, moderating, and spillover effects on rural revitalization.

This study introduces three key innovations. First, it refines the analytical scale to the municipal level, constructing comprehensive indices of NQP and rural revitalization levels across 282 cities in China over a 12-year period to accurately capture local government support and enable precise spatial analysis. Second, using the number of new development zones as an instrumental variable, it rigorously tests the causal impact of NQP on rural revitalization. Third, by systematically examining the heterogeneity and spatial spillover effects inherent in this relationship, it provides evidence-based policy recommendations that acknowledge regional variations and cross-boundary influences crucial for sustainable rural development strategies.

Theoretical analysis and hypothesis development

The concept of productivity has undergone significant transformations over time, dating back to classical economics. Classical economists such as François Quesnay, Adam Smith, and David Ricardo conceptualized productivity as the capacity to generate material wealth, measurable through land yields and labor output31. Jean-Baptiste Say proposed the three-factor theory, attributing wealth or productivity growth to three core factors: labor, land, and capital32. Friedrich List emphasized that examining wealth is distinct from studying productivity, asserting that humans are the ultimate determinants of productivity33. Karl Marx critiqued and incorporated classical economic theories of productivity, emphasizing that productivity represents humanity’s capacity to transform nature within specific production relations, thereby establishing productivity as the material foundation for social development and historical evolution34. Marx’s productivity theory transcended the narrow understanding of classical economics by proposing that productivity comprises three elemental components—laborers, labor objects, and labor means—which continuously evolve with scientific and technological advancements. Modern economics employs quantitative methods to investigate how inputs transform into outputs and facilitate economic growth. Neoclassical growth theory incorporates technological progress as an exogenous variable in production functions, emphasizing how technological advancement and factor accumulation enhance productivity35. Endogenous growth theory highlights how intangible assets (knowledge capital, human capital) and activities such as innovation and R&D drive productivity improvements and economic growth, providing microeconomic explanations for innovation’s role in economic advancement36. In China, the official declaration that “science and technology constitute the primary productivity” has resonated with these viewpoints since 1980s23. As technological innovation progressed, the concept of NQP emerged, representing a fundamental transformation in productivity’s essence. The core of NQP lies in the process whereby new-type laborers utilize new-type labor means to act upon new-type labor objects22. New-type laborers, as the primary agents, possess high educational attainment and strong learning capabilities, enabling them to create and operate new-type labor means such as automation, digitalization, and intelligence equipment. New-type labor objects encompass both tangible materials and intangible entities like data and knowledge, facilitating the enhancement of NQP.

Globally, rural revitalization is recognized as closely linked to multiple SDGs. For instance, through improvements in rural infrastructure, provision of basic services, and job creation, rural revitalization contributes to equitable poverty reduction (SDG 1), zero hunger (SDG 2), inclusive economic growth (SDG 8), and ecosystem restoration (SDG 15)37. OECD’s Rural Well-being Framework emphasizes that rural development goals transcend conventional economic growth, incorporating social (health, education, social inclusion, service accessibility) and environmental dimensions (ecosystems, climate resilience, environmental quality) into citizens’ well-being38. Aligning with international frameworks, China’s Rural Revitalization Strategy Plan defines five overarching goals of rural revitalization. Thriving industry serves as the economic backbone of rural revitalization, aimed at enhancing agricultural modernization and promoting industrial integration39. Livable environment is the ecological cornerstone, fostering sustainable human-nature coordination40. Cultural prosperity embodies the spiritual essence, enriching education and advancing cultural heritage and innovation41. Effective governance is the institutional safeguard, building advanced legal and moral systems41. Prosperous living is the ultimate goal, increasing villagers’ income and well-being to reduce urban-rural disparities42.

Based on the three elemental components of NQP, this study systematically examines the theoretical logic of how NQP empowers rural revitalization from both direct relationship and spatial spillover perspectives, closely aligned with the rural revitalization system oriented toward five overarching goals. The analytical framework is illustrated in Fig. 1.

The overarching logic of NQP empowering rural revitalization lies in its provision of knowledge-based, skilled, and innovative new-type rural laborers; new-type labor means encompassing big data, artificial intelligence, automated manufacturing equipment, digital infrastructure, and green energy; and new-type labor objects including data information, technological boundary expansion, and green low-carbon transformation. Optimizing the integration, allocation, and synergy of these elements catalyzes the emergence of novel industries, business models, and paradigms, enabling agricultural boundary expansion and value chain extension, thereby advancing rural development toward intensification, precision, digitalization, integration, and greening43. Ultimately, it provides strong support for comprehensive rural revitalization.

Specifically, NQP influences rural revitalization in five dimensions. First, NQP promotes rural industrial development, achieving thriving industry. It directly advances agricultural mechanization and intelligence, fosters green ecological agriculture and specialized agriculture, breaks through agricultural boundaries, extends rural industrial chains, enhances added value in rural industrial development, upgrades the entire rural industrial chain, facilitates integrated development across primary, secondary, and tertiary sectors, and forms a modernized rural industrial development pattern44,45,46. Second, NQP drives rural green transformation, realizing a livable environment. Being inherently green productivity, it accelerates innovation and vigorously promotes advanced green technologies, facilitates agricultural green development, constructs efficient ecological green industrial clusters, promotes resource efficiency, cultivates rural green lifestyles, protects and improves the rural ecological environment, drives comprehensive rural green transformation, and depicts a new portrait of beautiful villages suitable for living and working27. Third, NQP builds rural talent support, achieving cultural prosperity. Through digital technologies such as the internet and cloud computing platforms, as well as new-type labor objects including knowledge and information, it strengthens agricultural science and technology education and cultivates highly skilled agricultural and rural talents. By promoting comprehensive upgrades of rural infrastructure, narrowing urban-rural disparities, and reconstructing rural social relationships, it attracts and motivates more talents to congregate in rural areas47. Simultaneously, through the datafication of cultural elements, NQP continuously enriches rural cultural connotations, promotes the inheritance and innovation of traditional rural culture, and facilitates the protection and promotion of distinctive local cultural resources29,30, providing new pathways for comprehensively enhancing civilized rural customs. Fourth, NQP improves rural governance systems, achieving effective governance. It provides artificial intelligence technologies such as big data, machine learning, and intelligent algorithms for constructing digital rural governance platforms, expanding rural governance content, methods, and means, achieving digitalization of rural governance work and intelligence of rural governance scenarios, enhancing rural governance efficacy48, forming new rural governance patterns, and effectively supporting the modernization of rural social governance. Fifth, NQP assists farmers in increasing income, realizing prosperous living. It provides new production tools and technologies, drives improvements in agricultural production efficiency and output, catalyzes new business forms and employment opportunities, enhances farmers’ labor skills and employability, promotes the transformation of new rural production relations, broadens farmers’ income sources, increases farmers’ economic benefits49, promotes common prosperity among farmers, and thus substantively realizes the ultimate goal of prosperous living.

Based on the above analysis, this study posits the following hypothesis:

H1. New quality productivity positively impacts rural revitalization.

According to the first law of geography, all phenomena exhibit spatial dependence, with proximate entities having stronger connections50. NQP transcends the geographic constraints of traditional productivity, fostering inter-regional economic exchange and cooperation, optimizing resource allocation and sharing, and generating positive spillover effects on rural revitalization in adjacent areas through the following processes. First, agglomeration effects. The development of NQP forms advantageous industrial clusters in specific regions by concentrating new quality talents, social capital, and innovative resources51, thereby creating spatial agglomeration effects. This agglomeration not only achieves efficient resource utilization and coordinated industrial development, promoting local rural revitalization, but also enhances rural revitalization in adjacent areas through the sharing of infrastructure and services. Second, diffusion effects. The development and application of NQP diffuse spatially through multiple channels, whereby advanced productivity can spread from one region to adjacent regions through technology transfer, knowledge dissemination, and talent mobility. With the deepening advancement of digital rural construction, internet platforms and new media play increasingly prominent roles, accelerating the speed of knowledge and technology dissemination and expanding the scope of influence52. Therefore, the enhancement of NQP not only promotes local rural revitalization but also enhances rural revitalization in adjacent areas through diffusion effects.

Besides geographical connections, economically adjacent regions have similar economic development foundations, face similar economic development pressures, and exhibit high coordination and complementarity in the development of NQP. The promotion of successful experiences and mutual learning and imitation further drive rural development in adjacent areas, forming spillover effects of economic connections through the following processes. First, demonstration effects. The successful application and promotion of NQP achieving significant results in a certain region can provide replicable modes for adjacent regions. Through demonstration effects, adjacent regions can rapidly learn and replicate these successful experiences, reducing trial-and-error costs and accelerating the joint development of rural revitalization driven by NQP53. Second, peer effects. Under similar policy constraints, there exists intense competition among economically adjacent regions54. When rural revitalization levels in one region significantly improve due to vigorous development of NQP, neighboring regions often increase their emphasis on developing NQP to maintain competitiveness, actively learning and imitating these advanced practices, and promptly adjusting their own measures for developing NQP. Therefore, the enhancement of NQP often triggers a following phenomenon among adjacent regions, incentivizing surrounding areas to jointly develop NQP to empower rural revitalization.

Based on the above analysis, this study develops the following hypothesis:

H2. The impact of new quality productivity on rural revitalization has positive spatial spillover effects.

Research design

Sample selection and data sources

This study utilizes panel data from 282 cities in China from 2010 to 2021 as the research sample. Statistical data is sourced from the China Economic and Social Big Data Research Platform (https://data.cnki.net/), Index of Regional Innovation and Entrepreneurship in China (https://doi.org/10.18170/DVN/NJIVQB), and Digital Financial Inclusion Database (https://idf.pku.edu.cn/zsbz/index.htm). Missing data is processed through interpolation methods, while value variables (such as GDP) are deflated using the Consumer Price Index (CPI) with 2010 as the base period.

Variable measurement

-

1.

Dependent variable.

The dependent variable in this study is rural revitalization (RR). We select five dimensions—thriving industry, livable environment, cultural prosperity, effective governance, and prosperous living—to measure rural revitalization, as shown in Table 1. These dimensions not only represent China’s five overarching goals55,56 but also align with the requirements of SDGs 1, 2, 8, and 1537, as well as the economic, social, and environmental dimensions of OECD’s Rural Well-being Framework38. The range standardization method is employed to eliminate dimensional effects, the entropy weight method is used to determine the weights of evaluation indicators, and weighted averaging is applied to calculate the municipal rural revitalization levels.

Table 1 Rural revitalization evaluation indicator system. -

2.

Core explanatory variable.

The core explanatory variable is new quality productivity (NQP). Although approaches for measuring agricultural NQP have been proposed25, the dependent variable under investigation—rural revitalization—is not limited to agriculture but also encompasses secondary, and tertiary sectors. Therefore, grounded in Marx’s productivity theory34 and the definition of NQP22,57, we measure municipal NQP levels from three elemental components: new-type laborers, new-type labor objects, and new-type labor means, as shown in Table 2. This measurement system also incorporates endogenous growth theory’s emphasis on human capital and innovation, Industry 4.0’s focus on infrastructure, digitalization, and intelligentization, and green productivity and sustainable productivity’s emphasis on energy efficiency and environmental sustainability.

Table 2 New quality productivity evaluation indicator system. -

3.

Control variables.

To control for other factors affecting rural revitalization, with reference to existing research58,59, the following control variables are included in the model: (i) Economic scale (ES), measured by regional GDP; (ii) Population scale (PS), measured by regional permanent resident population; (iii) Industrial structure (IS), measured by the proportion of tertiary industry value added to regional GDP; (iv) Government support (GS), measured by the proportion of government fiscal expenditure to regional GDP; (v) Opening up (OU), measured by the annual actual utilized foreign investment. To mitigate the influence of extreme values and satisfy classical linear model assumptions such as homoscedasticity and normality, natural logarithmic transformations are applied to the above variables.

Research models

-

1.

Benchmark regression model.

To analyze the direct impact of NQP on rural revitalization, the following two-way fixed effect (TWFE) model is constructed:

$$R{R_{it}}=\alpha +{\beta _0}NQ{P_{it}}+{\beta _1}Control{s_{it}}+{\mu _i}+{\delta _t}+{\varepsilon _{it}},$$(1)where \(R{R_{it}}\) represents the rural revitalization level of city i in year t, \(NQ{P_{it}}\) represents the NQP level of city i in year t, \(Control{s_{it}}\) represents the control variables for city i in year t, \({\mu _i}\) represents individual fixed effects, \({\delta _t}\) represents time fixed effects, \({\varepsilon _{it}}\) represents the random disturbance term, \(\alpha\) is the intercept, and \({\beta _0}\) and \({\beta _1}\) represent the regression coefficients of the core explanatory variable and control variables, respectively.

-

2.

Spatial econometric model.

Based on the benchmark regression model, considering the spatial interaction effects between NQP and rural revitalization, a spatial weight matrix is introduced to construct the Spatial Durbin Model (SDM):

$$\begin{aligned} R{R_{it}} & =\alpha +\rho WR{R_{it}}+{\beta _0}NQ{P_{it}}+{\theta _0}WNQ{P_{it}} \hfill \\ & \quad +{\beta _1}Control{s_{it}}+{\theta _1}WControl{s_{it}}+{\mu _i}+{\delta _t}+{\varepsilon _{it}}, \hfill \\ \end{aligned}$$(2)where \(\rho\) is the spatial autoregressive coefficient, W is the spatial weight matrix, and \({\theta _0}\) and \({\theta _1}\) represent the lagged coefficient for the core explanatory variable and control variables, respectively. Other variables are consistent with the benchmark regression model.

Empirical findings

Descriptive statistics and trend analysis

Descriptive statistics of the main variables are presented in Table 3. As shown in Table 3, the mean, minimum, and maximum values of NQP levels are 0.0508, 0.0054, and 0.7624, respectively. The average, minimum, and maximum values of rural revitalization levels are 0.3493, 0.0043, and 0.9403, respectively. These statistics indicate substantial disparities in both NQP and rural revitalization levels across cities.

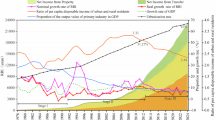

To analyze the spatiotemporal trends and characteristics of NQP and rural revitalization levels, we plot the annual overall means and regional means for all cities, as illustrated in Fig. 2. From a temporal perspective, both NQP and rural revitalization levels have consistently improved. The average NQP level increases from 0.0241 in 2010 to 0.0853 in 2021, while the average rural revitalization level rises from 0.2831 in 2010 to 0.4122 in 2021. Spatially, both NQP and rural revitalization levels exhibit a distribution pattern characterized by higher values in the east and lower values in the west.

Benchmark regression analysis

Prior to conducting regression analysis, a VIF test is performed to examine potential multicollinearity in the model. The test results show VIF values less than 10, indicating no significant multicollinearity issues, thus permitting regression analysis. A Hausman test is conducted on the fixed effects and random effects models, yielding a P-value of 0.0000, which rejects the null hypothesis that there is no significant difference between the coefficient estimates of the two models. Therefore, the fixed effects model is selected for benchmark regression analysis, with both individual and time effects controlled to eliminate the influence of heterogeneity across cities and time series fluctuations on the estimation results. A modified Wald test is employed to determine whether heteroscedasticity exists among error terms across different individuals. The results show a P-value of 0.0000, indicating the presence of heteroscedasticity in the model; consequently, robust standard errors are adopted to address this issue.

The test results of the fixed effects model with robust standard errors as the benchmark regression model are presented in Fig. 3(1). The results indicate that the estimated coefficient of NQP is 0.2038 and significantly positive at the 1% level, demonstrating that NQP has a significant positive impact on rural revitalization. Specifically, a 1% increase in NQP corresponds to a 0.2038 unit improvement in rural revitalization, validating H1. Further regression analysis reveals that NQP has a highly significant positive influence on all five goals of rural revitalization. A 1% increase in NQP corresponds to improvements of 0.1971, 0.2115, 0.2116, 0.1763, and 0.2223 units in thriving industry, livable environment, cultural prosperity, effective governance, and prosperous living, respectively. This indicates that NQP effectively enhances the added value of rural industrial development, promotes the integration of socioeconomic and ecological benefits, activates rural talent and culture, constructs a new pattern of rural governance, and facilitates the common prosperity of farmers’ spiritual life, thereby comprehensively advancing rural revitalization.

Robustness test

To further ensure the robustness of the regression results, four methods of robustness testing are employed: (i) One-period lag: Considering the potential time-lagged effect of NQP on rural revitalization, NQP is processed with a one-period lag and used as the new core explanatory variable. (ii) Excluding samples from municipalities directly under the central government: Given the special administrative status and economic characteristics of municipalities, tests are reconducted after excluding the four municipalities directly under the central government to examine the universality of NQP’s effect on rural revitalization. (iii) Replacing variables: To eliminate the influence of different weighting methods, the average weighting method is used instead of the entropy weighting method to recalculate NQP and rural revitalization levels, replacing the core explanatory and explained variables in the benchmark regression model. (iv) Winsorization: To eliminate the influence of extreme values, winsorization is performed on the top and bottom 10% of observations for NQP and rural revitalization.

The results of the robustness tests are presented in Fig. 3(2–5). The findings demonstrate that the direction of NQP’s effect on rural revitalization is consistent with the benchmark regression results, with differences only in coefficient magnitude and significance level, thus confirming the robustness of the benchmark regression results. The coefficient of one-period lagged NQP is larger and remains significant, confirming its persistent effect on rural revitalization. This aligns with Bosworth et al.’s60 findings that social innovations in European rural areas yield positive outcomes only after prolonged periods. However, unlike their emphasis on short-term invisibility due to social controversies, our evidence reveals benefits in both short and long terms—likely attributable to China’s top-down administrative system with performance-based governance enabling rapid policy execution. After excluding special samples and extreme values, the coefficient of NQP increases, indicating that the effect of NQP on rural revitalization is more pronounced under more general circumstances.

Endogeneity test

To address potential endogeneity issues arising from omitted variables and bidirectional causality, we employ the number of new development zones as an instrumental variable for endogeneity testing. New development zones, established by national or provincial governments, encompass economic and technological development zones, high-tech industrial parks, and bonded zones tasked with significant national or regional development and strategic objectives12,13. The number of new development zones is selected as the instrumental variable for the following reasons: First, these zones serve as critical platforms for attracting high-caliber talent, fostering technological innovation, and advancing the digital economy, making them closely correlated with NQP and satisfying the relevance condition for an instrumental variable. Second, the establishment of new development zones is driven by government planning, exhibiting policy-driven exogeneity. Their designation and approval are strictly confined to urban development boundaries 61, excluding vast rural areas outside these boundaries. Consequently, we argue that new development zones only affect rural revitalization through NQP, thereby satisfying the exogeneity requirement for an instrumental variable.

A two-stage least squares (2SLS) approach with the instrumental variable is employed to test for endogeneity, with regression results presented in Table 4. The results show that in the first-stage regression (Column 1), the coefficient of the number of new development zones is significantly positive at the 1% level, confirming the instrument’s relevance. The Kleibergen-Paap rk LM statistic of 44.8750 rejects the null hypothesis of under-identification at the 1% significance level, and the Cragg-Donald Wald F statistic exceeds the Stock-Yogo critical value for weak instrument identification at the 10% significance level, rejecting the null hypothesis of a weak instrument. These tests collectively validate the appropriateness of the chosen instrumental variable. In the second-stage regression (Column 2), the coefficient of NQP is significantly positive at the 1% level, reaffirming that NQP promotes rural revitalization, consistent with the benchmark regression results.

Moderating effect analysis

China’s vast territory encompasses rural areas with significant differences in economic development levels, industrial structures, and resource endowments across geographic regions, necessitating further examination of the differential impacts of NQP on rural revitalization across regions to provide references for developing location-specific development policies. To this end, based on the China Industrial Economy Statistical Yearbook, we construct a geographical region (GR) classification variable, dividing 282 cities into eastern, central, and western regions (as shown in Fig. 4). We add the interaction term between NQP and GR to the benchmark regression model to test the moderating effect, with regression results shown in column (1) of Table 5. The results show that the coefficients of the interaction terms between NQP and GR are 0.3283 and − 0.1126, respectively, both significant at the 1% level. This indicates that NQP promotes rural revitalization in China’s eastern, central, and western regions, but this positive effect gradually weakens from the eastern to the central and western regions. This may be because, compared to the central and western regions, the eastern region has a higher level of economic development, accumulation of capital, technology, and talent, stronger scientific and technological innovation capabilities, well-developed infrastructure, and a higher degree of marketization. These factors help NQP to be more quickly and effectively promoted and applied in rural areas, translating into actual rural revitalization outcomes. Therefore, the effect of NQP in promoting rural revitalization is more significant in the eastern region.

Due to the combined influence of central government support policies, local government autonomy, fiscal revenue, and leadership decision-making, there are significant differences in government support (GS) across regions. To examine the impact of NQP on rural revitalization under different levels of government support, we add the interaction term between NQP and GS to the baseline regression model to test the moderating effect, with regression results shown in column (2) of Table 5. The results show that the coefficient of the interaction term between NQP and GS is significantly positive at the 5% level, indicating that government support plays a positive moderating role between NQP and rural revitalization. In other words, in cities with higher levels of government support, NQP can better exert its promoting effect on rural revitalization. This is because government support has a leverage and guiding role in the application of NQP in rural revitalization. Governments can mobilize fiscal, human, and land resources, implement financial support, tax incentives, financial assistance, and other policy instruments to create a favorable external environment for the development of NQP, provide the necessary funds and resources for NQP, guide enterprises and research institutions in collaborative innovation, introduce high-level rural talent, and subsequently attract follow-up social capital, bringing together the strengths of government, market, and society to jointly promote the establishment of NQP in rural areas and drive comprehensive rural revitalization.

To comprehensively understand the combined impact of geographical region and government support, we incorporate both interaction terms into the model simultaneously to test the moderating effects, with regression results shown in column (3) of Table 5. The results show that when considering both geographical region and government support simultaneously, the moderating effect of geographical region remains significantly negative at the 1% level, and the moderating effect of government support remains significantly positive at the 5% level. This further validates the establishment of the moderating effects and highlights the importance of the synergistic effects of regional endowment orientation and increased government support.

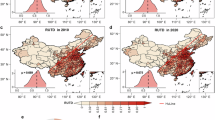

Spatial spillover effect analysis

We first use the Moran’s I index62 to test the spatial autocorrelation of rural revitalization. Results show significantly positive global Moran’s I indices across all years. Figure 5 reveals cities concentrated in first and third quadrants, indicating high-high and low-low spatial clustering patterns. This confirms significant positive spatial autocorrelation, justifying spatial econometric modeling. The clustering suggests regional development imbalance, with potential for high-level regions to drive neighboring areas’ development. The declining trend in global Moran’s I from 2010 to 2021 indicates gradually reducing regional disparities.

Following63, we then conduct LM, LR, and Wald tests for spatial model selection. LM-Error (1484.80) and LM-Lag (1679.30) statistics are significant at 1%, with robust tests also rejecting spatial independence. Significant LR and Wald tests (p < 0.01) reject model degeneracy, confirming the spatial Durbin model as optimal. Hausman and LR tests (p < 0.01) favor two-way fixed effects over alternatives. Therefore, we adopt the spatial Durbin model with two-way fixed effects.

Using four spatial weight matrices, we apply the spatial Durbin model with two-way fixed effects to test NQP’s spatial spillover effects on rural revitalization. Parameters are estimated via bias-corrected maximum likelihood proposed by64, with results in Table 6. The significantly positive spatial lag coefficients of NQP indicate positive spillover effects through both geographic and economic proximity. Therefore, NQP enhancement not only promotes local rural revitalization but also drives neighboring regions’ rural revitalization, confirming H2.

We further decompose the spatial Durbin model effects into direct, indirect, and total effects (Table 6). Results show significantly positive direct effects (p < 0.01), indicating local NQP promotes local rural revitalization. Significantly positive indirect effects confirm that local NQP enhances rural revitalization in neighboring regions, demonstrating positive spatial spillover effects and validating H2. These findings reveal NQP’s dual impact on both local and regional rural development.

Under geographic proximity, direct effects exceed indirect effects, suggesting NQP more significantly enhances local rural revitalization than neighboring regions. This occurs because NQP development requires local policy support, resource investment, infrastructure, and organizational coordination, concentrating new talents, social capital, and innovation locally. Although NQP spreads to proximate cities through technology transfer, knowledge dissemination, and talent mobility, neighboring impacts remain limited due to policy scope constraints, economic foundation differences, and local protectionism. Therefore, NQP more effectively promotes rural revitalization within local administrative jurisdictions than in geographically proximate cities.

Under economic proximity, indirect effects exceed direct effects, indicating NQP generates greater impact on economically proximate regions than locally. Economically similar cities share comparable economic foundations, policy environments, and governance levels, enabling easy replication of successful NQP experiences through mutual learning. More importantly, facing intense competition and development pressures, economically proximate cities propose attractive incentive policies for talent, investment, and innovation, facilitating cross-regional resource flow and optimal allocation. This accelerates NQP diffusion to broader rural areas, making local NQP development significantly drive rural revitalization in economically proximate regions.

Under economic-geographic proximity, indirect effects exceed direct effects, with coefficients closer to economic proximity results, suggesting economic proximity dominates in combined effects. Geographic proximity spillovers rely mainly on spontaneous, unorganized NQP flows, while economic proximity spillovers stem from proactive government learning and collaborative innovation through policy supply and cooperative promotion, enabling location-specific rural revitalization with greater effectiveness. Importantly, economic-geographic proximity shows the most significant indirect effect coefficient among four models, indicating dual proximity effects significantly enhance NQP spillovers. Close economic ties and favorable geographical conditions jointly promote NQP diffusion, emphasizing both geographical and economic regional connections. This implies localities should focus not only on local NQP development but also emphasize collaboration with adjacent regions to achieve more extensive rural revitalization effects.

Conclusions and policy implications

This study clarifies the theoretical impact mechanism of NQP on rural revitalization from a novel spatial perspective. Using panel data from 282 cities in China between 2010 and 2021, we conduct empirical tests to examine the direct, moderating, and spatial spillover effects of NQP on rural revitalization. The main contributions are as follows:

First, we construct comprehensive municipal-level indices for both NQP and rural revitalization across 282 Chinese cities. Our analysis reveals consistent upward trends in both metrics from 2010 to 2021 alongside persistent spatial disparities characterized by higher values in eastern regions and lower values in western regions, providing a finer scale. Second, employing instrumental variable estimation with new development zones, we establish robust causal evidence that NQP significantly enhances rural revitalization with lasting effects, moving beyond correlational analysis in prior studies. Third, we identify critical heterogeneities: NQP’s impact diminishes from eastern to western regions, while government support amplifies NQP’s beneficial effects, highlighting the importance of leveraging regional endowments and strengthening government support. Fourth, spatial econometric analysis uncovers substantial positive spillover effects whereby NQP improvements benefit both local and neighboring cities, empirically verifying innovation diffusion mechanisms and their relative magnitudes across proximity types.

Based on the findings, we propose three key policy recommendations:

First, tailor NQP development to local conditions with accelerated rural penetration. Policymakers must extend support beyond urban centers through comprehensive reforms in land institutions and management systems to enhance resource allocation efficiency. Regions with well-developed resource endowments should lead NQP innovation, while moderately developed areas should strengthen infrastructure and talent cultivation. Resource-constrained regions require preferential policies—including financial subsidies, technical training, and talent incentives—to guide skilled professionals and agricultural technologies toward rural service, narrowing development disparities.

Second, strengthen government’s guiding and service roles in NQP advancement. Beyond financial investment in rural infrastructure, governments should provide information services and market guidance to reduce information asymmetry. Deepening institutional reforms can stimulate factor vitality and accelerate new production relations formation, using NQP as an engine for high-quality rural modernization.

Third, establish cross-regional collaborative mechanisms to maximize NQP’s spillover effects. Given spatial interdependencies, policies should facilitate resource sharing and experience exchange across cities, promoting circulation of human capital, technology, and data. Leveraging urban agglomerations and economic belts through coordination frameworks can fully activate NQP’s spatial spillover potential, achieving broader rural revitalization.

The research outcomes also hold potential insights for countries at different development stages. In advanced economies, the NQP’s innovation-driven mechanism can complement rural digitalization and green transition agendas. In emerging economies, this provides a pathway to narrow urban–rural divides by mobilizing technology, talent, and institutional reforms. In low-income regions, NQP principles can guide targeted investments in human capital and infrastructure.

However, several limitations warrant acknowledgment. First, our analysis is confined to China’s institutional context, potentially limiting generalizability to different political-economic systems. Second, relying on macro-level statistical data due to availability constraints, our analysis does not involve micro-level factors such as farmers’ subjective well-being and underlying mechanisms. Future research should extend this framework under varying institutional arrangements. Additionally, mixed-methods approaches incorporating field surveys and qualitative case studies would provide deeper insights into micro-level mechanisms.

Data availability

All data sources are cited in the main text and can be accessed through their respective publishing organizations. The data is also available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Camarero, L. & Oliva, J. Thinking in rural gap: mobility and social inequalities. Palgrave Commun. 5, 95. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0306-x (2019).

Li, Y., Westlund, H. & Liu, Y. Why some rural areas decline while some others not: an overview of rural evolution in the world. J. Rural Stud. 68, 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.03.003 (2019).

Cohen, S. A. & Greaney, M. L. Aging in rural communities. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 10, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40471-022-00313-9 (2023).

Lloyd, J. L. From farms to food deserts: food insecurity and older rural Americans. Generations 43, 24–32 (2019).

Xie, H., Sun, Q. & Song, W. Exploring the ecological effects of rural land use changes: A bibliometric overview. Land 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/land13030303 (2024).

Chen, S. & Zhang, Y. Research progress on biodiversity in the rural landscape. Biodivers. Sci. 29, 1411–1424. https://doi.org/10.17520/BIODS.2021135 (2021).

FAO. Rural Development Report 2021 [WWW Document]. https://www.fao.org/family-farming/detail/en/c/1444259/ (Accessed 13 Mar 25) (2021).

Frank, S. et al. Enhanced agricultural carbon sinks provide benefits for farmers and the climate. Nat. Food. 5, 742–753. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-024-01039-1 (2024).

OECD. A New Rural Development Paradigm for the 21st Century: A Toolkit for Developing Countries (Development Centre Studies, OECD Publishing, 2016).

National Bureau of Statistics. Statistical Bulletin of the National Economic and Social Development of the People’s Republic of China for the Year 2024 [WWW Document]. https://www.gov.cn/lianbo/bumen/202502/content_7008605.htm (Accessed 13 Mar 25) (2025).

Gao, X. et al. Understanding rural housing abandonment in China’s rapid urbanization. Habitat Int. 67, 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2017.06.009 (2017).

Zhang, Q. et al. Understanding the role of land attachment in the emergence of Hollow villages based on the agent-based complex system framework. Land. Use Policy. 150, 107441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2024.107441 (2025a).

Zhang, Y., Wang, K., Li, F., Gong, Y. Y. & So, S. L. Place-based policy, industrial coagglomeration, and urban carbon productivity: evidence from the establishment of China’s National New Zones (NNZs). Sustain. (Switzerland) 17, 3085. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073085 (2025b).

Chen, B. & Lin, Y. Development Development strategy, urbanization and the urban-rural income gap in China. Social Sci. China. 35, 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/02529203.2013.875651 (2014).

Edwards, J. Marx on social structure, ideology, and historical transformation. In Transformation and the History of Philosophy. 223–237. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003056409-20 (2023).

Xi, J. Accelerate the Development of New Quality Productivity to Solidly Promote High-Quality Development [WWW Document]. URL https://www.gov.cn/yaowen/liebiao/202402/content_6929446.htm (Accessed 14 Mar 25) (2024).

Castelo-Branco, I., Amaro-Henriques, M., Cruz-Jesus, F. & Oliveira, T. Assessing the industry 4.0 European divide through the country/industry dichotomy. Comput. Ind. Eng. 176, 108925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2022.108925 (2023).

Hou, C. Analysis of the factors promoting urban green productivity using a system dynamics simulation. Sci. Rep. 15, 27928. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13699-5 (2025).

Yue, S., Shen, Y. & Yuan, J. Sustainable total factor productivity growth for 55 states: an application of the new Malmquist index considering ecological footprint and human development index. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 146, 475–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.03.035 (2019).

Jin, M. & Jiang, X. Research on coupling coordination level between new-quality productivity and industrial structure upgrading in the Yangtze river economic belt urban area. Sustainability 17, 5201. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17115201 (2025).

Yang, L., Xu, Y., Zhu, J. & Sun, K. Spatiotemporal evolution and influencing factors of the coupling coordination of urban ecological resilience and new quality productivity at the provincial scale in China. Land 13, 1998. https://doi.org/10.3390/land13121998 (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. Study on the coordinated development degree of new quality productivity and manufacturing carbon emission efficiency in provincial regions of China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-024-05321-x (2024).

Yue, S., Bajuri, N. H., Khatib, S. F. A. & Lee, Y. New quality productivity and environmental innovation: the hostile moderating roles of managerial empowerment and board centralization. J. Environ. Manage. 370, 122423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.122423 (2024).

Chu, H., Niu, X., Li, M. & Wei, L. Research on the impact of new quality productivity on enterprise ESG performance. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance. 99, 104009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2025.104009 (2025).

Luo, W., Zuo, S., Tang, S. & Li, C. The formation of new quality productivity of agriculture under the perspectives of digitalization and innovation: A dynamic qualitative comparative analysis based on the Technology-Organization-Environment. Framew. Sustain. 17, 597. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17020597 (2025).

Li, F. & Jiang, C. The realistic dilemmas, logical approaches and practical paths of new⁃quality productivity empowering rural revitalization. J. Nanjing Agricultural Univ. (Social Sci. Ed.) https://doi.org/10.19714/j.cnki.1671-7465.20241226.001 (2024).

Wang, Y., Qu, L., Cui, X., Yang, Y. & Zhou, L. New quality productivity and rural green development: new industrial morphology cultivation and new path exploration. J. Agricultural Resour. Environ. 41, 991–996. https://doi.org/10.13254/j.jare.2024.0391 (2024).

Ullah, I., Dagar, V., Tanin, T. I., Rehman, A. & Zeeshan, M. Agricultural productivity and rural poverty in China: the impact of land reforms. J. Clean. Prod. 475, 143723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.143723 (2024).

Wang, M., Luo, Z., Fang, Y. & Yang, X. Digital technology mediated rural studies: perspectives from social and cultural geography. Progress Geogr. 41, 499–509. (2022).

Wang, S., Shi, X., Wang, T. & Hong, J. Nonlinear spatial innovation spillovers and regional open innovation: evidence from China. R&D Manag. 52, 854–876. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12527 (2022b).

Kurz, H. D. Technical progress, capital accumulation and income distribution in classical economics: Adam Smith, David Ricardo and Karl Marx. Eur. J. Hist. Econ. Thought. 17, 1183–1222. https://doi.org/10.1080/09672567.2010.522242 (2010).

Bai, B. & Bai, R. Deficiencies of the three-factor theory of value: external deficiencies of the modern factor theory of value. World Rev. Political Econ. 13, 60–96. https://doi.org/10.13169/worlrevipoliecon.13.1.0060 (2022).

List, F. National System of Political Economy (JB Lippincott & Company, 1856).

Marx, K. Capital A Critique of Political Economy (Forgotten Books, 1901).

Solow, R. M. A contribution to the theory of economic growth. Q. J. Econ. 70, 65–94 (1956).

Romer, P. M. Increasing returns and long-run growth. J. Polit. Econ. 94, 1002–1037 (1986).

Cai, M., Ouyang, B. & Quayson, M. Navigating the nexus between rural revitalization and sustainable development: A bibliometric analyses of current status, progress, and prospects. Sustain. (Switzerland). 16, 1005. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031005 (2024).

OECD. Rural Well-being: Geography of Opportunities (OECD Publishing, 2020).

Tian, Y., Liu, Q., Ye, Y., Zhang, Z. & Khanal, R. How the rural digital economy drives rural industrial revitalization—case study of China’s 30 provinces. Sustain. (Switzerland). 15, 6923. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086923 (2023).

Huang, G. A look at rural ecological revitalization. Chi J. Eco-Agri. 27, 190–197. https://doi.org/10.13930/j.cnki.cjea.180820 (2019).

Geng, Y., Liu, L. & Chen, L. Rural revitalization of China: A new framework, measurement and forecastrural revitalization of China: A new framework, measurement and forecast. Socioecon Plann. Sci. 89, 101696. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2023.101696 (2023).

Xu, X. & Wang, Y. Measurement, regional difference and dynamic evolution of rural revitalization level in China. J. Quant. Technological Econ. 39, 64–83 (2022).

Tang, Y. Promoting Comprehensive Rural Revitalization Through New Quality Productivity (Liaoning Daily, 2024).

Hu, Y., Yu, H. & Chen, Q. Digitalization driving High-Quality converged development of rural primary, secondary, and tertiary industries: mechanisms, effects, and paths. Sustain. (Switzerland). 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511708 (2023).

Thangamani, R., Sathya, D., Kamalam, G. K. & Lyer, G. N. AI green revolution: reshaping agriculture’s future. In Signals and Communication Technology, 421–461. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-51195-0_19 (2024).

Yuan, W., Zhang, L. & Chen, T. Research development context and prospect of rural industry revitalization in China. J. Chin. Agricultural Mechanization. 46, 299–306 and 337. https://doi.org/10.13733/j.jcam.issn.2095-5553.2025.01.043 (2025).

Cheng, C., Gao, Q., Ju, K. & Ma, Y. How digital skills affect farmers’ agricultural entrepreneurship? An explanation from factor availability. J. Innov. Knowl. 9 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2024.100477 (2024).

Androniceanu, A. The new trends of digital transformation and artificial intelligence in public administration. Administratie Si Manage. Public. 2023, 147–155. https://doi.org/10.24818/amp/2023.40-09 (2023).

Elisabeth, C. Revolutionizing farming: exploring the complex relationship between agricultural machinery, technology progress, and farmers’ income in developing nations. AgBioForum. 24, 236–246 (2022).

Tobler, W. R. A computer movie simulating urban growth in the Detroit region. Econ. Geogr. 46, 234. https://doi.org/10.2307/143141 (1970).

Liu, S., Guo, R. & Wu, L. Empowering the construction of a modern industrial system with new quality productivity: internal logic, key issues, and practical pathways. Soc. Sci. Xinjiang. (2024).

Chen, Y. Mechanism innovation for the integrated development of digital economy and rural industry. Issues Agricultural Econ. 81–91. (2021).

Jiang, C. The agricultural new quality productive forces: Connotations, development priorities, constraints and policy recommendations for the development. J. Nanjing Agricultural Univ. (Social Sci. Edition). 24, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.19714/j.cnki.1671-7465.20240429.001 (2024).

Yu, J., Zhou, L. A. & Zhu, G. Strategic interaction in political competition: evidence from spatial effects across Chinese cities. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 57, 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2015.12.003 (2016).

Li, G. & Zhang, X. The spatial–temporal characteristics and driving forces of the coupled and coordinated development between new urbanization and rural revitalization. Sustain. (Switzerland). 15, 16487. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316487 (2023).

Zhao, Q., Bao, H. X. H. & Yao, S. Unpacking the effects of rural homestead development rights reform on rural revitalization in China. J. Rural Stud. 108, 103265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2024.103265 (2024).

Yao, L., Li, A. & Yan, E. Research on digital infrastructure construction empowering new quality productivity. Sci. Rep. 15, 6645. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90811-9 (2025).

Liang, S. & Chen, C. Rural industrial revitalization and farmers’ common prosperity: theoretical clues and empirical evidence. Rural Econ. 82–92. (2024).

Tian, Y., Ye, Y., Huang, J. & Liu, Q. The internal mechanism and empirical test of rural industrial revitalization driven by digital economy: based on the mediating effect of urban and rural integration development. Issues Agric. Econ. 84–96. https://doi.org/10.13246/j.cnki.iae.2022.10.003 (2022).

Bosworth, G. et al. Identifying social innovations in European local rural development initiatives. Innov. : Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 29, 442–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2016.1176555 (2016).

Ministry of Natural Resources. Circular on Effectively Managing Urban Development Boundaries. (2023).

Moran, P. A. Notes on continuous stochastic phenomena. Biometrika 37, 17–23 (1950).

Elhorst, J. P. Matlab software for spatial panels. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 37, 389–405 (2014).

Lee, L. & Yu, J. Estimation of spatial autoregressive panel data models with fixed effects. J. Econ. 154, 165–185 (2010).

Funding

This study has been supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant number 21AZD041) and the Outstanding Innovative Talents Cultivation Funded Programs 2024 of Renmin University of China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JH.Z. conceptualized the study, developed the methodology, conducted the formal analysis, curated the data, wrote the original draft, and prepared visualizations. WL.K. contributed to the methodology, software development, and validation. XB.W. conducted the investigation, contributed to validation, and participated in reviewing and editing the manuscript. ZF.Z. acquired funding, managed the project, supervised the research, and contributed to reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This study does not involve human participants, medical procedures, or any form of experimentation covered under the Helsinki Declaration. As such, our institution has determined that ethical approval is not required for this study.

Informed consent

This research relied exclusively on publicly available statistical yearbooks and databases. No primary data is collected directly from human participants. As such, individual informed consent is not required for this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, JH., Kong, WL., Wang, XB. et al. Unleashing new quality productivity for rural revitalization: a spatial panel data analysis of 282 cities in China. Sci Rep 16, 114 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29419-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29419-y