Abstract

Falls and injuries and their consequences impact people’s quality of life (QoL), especially in older people. This study assesses the level of falls, injuries, and QoL and examines the linkages of QoL with falls, and injuries among older people in India. The study used data from the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India, Wave-I (2017-18). Univariate, bivariate, and ordered logistic regression analyses were performed for analysis. The study reveals that 13% and 14% of older adults experienced major falls and injuries, with 40% experienced low and 30% each experienced medium, and high QoL. The results suggest that older people with no self-care had higher major falls (21.7%) and injuries (22.6%), while those who could not perform their usual activities had higher major falls (17.3%) and injuries (18.4%). Ordered logistic regression results showed that older people with minor and major falls were 30% and 39%, respectively, less likely to have higher QoL. Older people with injuries were 35% less likely to have higher QoL. This study’s findings suggest that falls and injuries were crucial factors in reducing the QoL of older people. The findings indicate the importance of improving the QoL of older people by reducing the risk of experiencing falls and injuries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global population is ageing rapidly, with the most significant increases in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) due to demographic changes and medical advances. Projections show that the number of older people aged 60 and above will double by 2050 from 1 billion in 2019 to 2.1 billion by 2050, with more than 80% of the population residing in LMICs1. According to the Indian population census 2011, India, which recorded more than one billion population, made it the second most populous country in the world but now India, with more than 1.4 billion population, is the most populous country in the world2. Among them, approximately 103 million adults who were aged above 60 years with 8.6% of the total population. Projections suggest that the share of older population (60 and above) will rise to 19.5% (319 million) by 20503.

Older adults in India face numerous health challenges, with falls being among the most significant. As defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), falls include slips or trips that result in an unintentional descent to the ground or a lower level4. Falls are the leading cause of injury, disability, and early death in adults over the age of 65. As the global population ages rapidly, preserving the health and independence of older adults is increasingly vital5. Over one-third of adults aged 65 and above fall each year, with more than half experience repeated falls, making falls a leading cause of death in developed countries6. Although, people of all ages can fall, but older adults have been found to be particularly at risk due to musculoskeletal changes and joint weakness that increase their risk of fractures7.

Falls and related injuries pose a major public health concerns among India’s older population, significantly affecting their quality of life (QoL). A systematic review reported that 65.6% of older adults with falls sustained injuries, including lower limb injuries (34.4%), cuts (38%), fractures (12.5%), and disabilities (11%)8. Data from Longitudinal Ageing Study of India (LASI) indicate that visual impairment is a key risk factor, which showed a 16% increased fall risk for those with low vision and 40% for those with blindness, with women being higher vulnerability9. Frailty also contributes notably, with frail individuals experiencing more falls (15.4% vs. 11.9%) and injuries (6.7% vs. 5.3%) as compared to their non-frail counterparts10.

Environmental factors such as poor lighting, unsafe public transport, and hazardous surroundings further elevate fall risks and limit social participation11,12. Falls and injuries pose a major socioeconomic challenge for older adults living alone, particularly those in single-family homes with poorer financial conditions and social support, which restrict their access to follow-up care13. In addition to injuries, falls often result in developed post-fall anxiety, reduced physical activity, and disrupted daily routines, increase social isolation, depression, and diminished well-being14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22.

Findings from several studies indicate that physiological and behavioural risk factors for falls include problems with gait, balance, strength, and vision, joint weakness, and excessive alcohol use23,24,25. The Centres for Disease Control and Prevention reports revealed that among older people, falls are one of the leading causes of death and disability; in this age group, falls cause 20% to 30% of injuries and 50% of injury-related hospitalizations26. Previous studies have reported the prevalence of falls among older adults in India to range from 26% to 37%, with a pooled prevalence of approximately 31% (95% CI: 23–39)27,28. Even when falls may not cause major injuries, they still affect older people’s mobility and functionality. Approximately one-third of persons aged 65 years and above have fallen at least once every year29,30,31. An Indian study also identified key risk factors for falls in this population, emphasizing the role of sociodemographic characteristics, environmental conditions, underlying health problems, and medical interventions8. Hospital stays for fall-related injuries often range from 4 to 15 days and are longer for cases involving fragility, hip fractures, or advanced age. Additionally, over 30% of older adults limit daily activities, and 30% to 55% report a fear of falling32. Falls and injuries in older adults reduce autonomy, increase dependency and fear, and lower QoL. Those who fall often have more comorbidities and require medical attention33.

Contrary to the need to maintain a balanced diet to strengthen bones and prevent trauma from injuries, the majority of older adults have inadequate nutrition34 In later life, older adults face challenges like multimorbidity, poor mental and functional health, insecurity, and social exclusion. Researchers increasingly advocate for prioritizing QoL over longevity through targeted funding and studies35. While all age groups are at risk of falls, older adults are more vulnerable due to musculoskeletal decline, leading to higher chances of fractures, increased healthcare needs, and post-fall syndrome that limits mobility and daily functioning. Numerous types of research have identified risk factors for falling; however, most of these studies looked at the older population in local areas rather than focusing primarily on older people who live alone36.

Recent studies also highlight that falls and fear of falling are directly related to health-related quality of life (HRQOL), especially among older people15,37. Other studies suggest that those with mobility issues and dependency with others for daily routine work are more prone to fall and tend to have lower HRQOL compared to independent older people38,39,40. Furthermore, studies suggest that HRQOL and falls are interconnected, with those experiencing falls often reporting reduced subjective well-being41,42,43.

However, most of the prior research originates from higher-income countries (HICs) with only some studies from LMICs and Indian community-based studies only included a small number of subjects or perhaps only a particular community. Therefore, the research on the link between HRQOL with fall and injuries among older persons requires an India-level study with representative samples. In order to obtain a more thorough and integrated understanding of falls and injuries and their contributing factors in the older population, HRQOL was measured using the Euro-QOL five-dimension questionnaire (EQ-5D), the visual analog scale (VAS), and chronic disease. With this backdrop, the present study assesses the level of falls, injuries, and QoL and examines the linkages of QoL with falls, and injuries among older people in India.

Methods and materials

Data source

This study uses data came from the first Wave of Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI). In order to examine the health, economic, and social factors that influence population aging, LASI conducted a comprehensive nationwide survey in 2017-18. The LASI, Wave-1 covered a panel sample of 72,250 individuals age 45 and above and their spouses, including 31,464 elderly persons age 60 and above and 6749 oldest-old persons age 75 and above from 35 states and union territories (UTs) of India (excluding Sikkim). LASI used a multistage stratified area probability cluster sampling methodology to arrive at the final units of observation. This included older individuals aged 45 and up and their spouses of any age.

The survey employed a four-stage sampling design in urban areas and a three-stage sample design in rural areas. Choosing Primary Sampling Units (PSUs) and sub-districts (Tehsils/Talukas) was the first step in each state or UT. The second step was choosing villages in rural areas and wards in urban areas within the selected PSUs. In the third round, households were selected from designated communities in rural areas. On the other hand, sampling in metropolitan areas requires an extra step. In the third stage, a Census Enumeration Block (CEB) was chosen randomly in each urban area. Households from this CEB were selected in the fourth stage.

For the present study, a sample of 31,464 individuals aged 60 and above years was used to ensure a robust and representative analysis of health and QoL outcomes among the older adults.

Methods

Outcome variables

The outcome variable for this study is a health-related quality of life (HRQOL), which is interchangeably used as a quality of life (QoL). HRQOL is defined as a multidimensional construct encompassing the perceived impact of health status or diseases on an individual’s physical, mental, and social functioning. This indicator serves as a comprehensive indicator of the extent to which health influences overall well-being and daily life activities44,45. We assessed the HRQOL of each subject based on their responses to the Euro-QOL five dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaire, which may suffice to compute HRQOL based on EQ-5D, a generic measure of HRQOL. The EQ-5D comprises five dimensions (mobility, self-care/activities of daily living (ADL), usual activities/instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), pain, and depression-CES), and each dimension is categorized into two levels of indicating presence or absence (no and yes)46. The EQ-5D questionnaire is currently available in two formats: EQ-5D-3 L and EQ-5D-5 L, where “L” denotes the number of response levels used to assess health status across five dimensions. The present study employed the EQ-5D instrument with two levels of health status measurement across all five dimensions47. The five health dimensions captured in the LASI dataset are described below.

The first dimension of EQ-5D measurement is defined as mobility. Respondents were asked mobility-related nine questions in LASI such as walking 100 yards, sitting for two hours or longer, rising from a chair after sitting for a long time, climbing one flight of stairs without stopping, stooping, kneeling, or crouching, reaching or extending arms above shoulder level (either arm), pushing or pulling heavy objects, lifting or carrying weights over five kilograms, such as a heavy grocery bag, picking up a coin from a table, etc. All mobility-related conditions were recoded as 1 “yes” (having difficulty) and 0 “No” (no difficulty).

The second dimension of EQ-5D is described as self-care/ADL. ADLs are widely accepted as a core measure of self-care, particularly in ageing research and clinical practice. ADLs were measured using the Kartz Index of Independence, which encompass basic tasks such as bathing, dressing, eating, toileting, getting in or out of bed and mobility functions that are essential for maintaining independence and well-being in older adults. Each item (ht401-ht406) was coded independent = 1 and dependent = 0, summed to a score of 0–6 (6 = full independence; 0 = complete dependence). The composite was dichotomized as ADL limitation (0–2) vs. no limitation (3–6), with missing values set to missing. The Katz Index is widely applied in geriatric and epidemiological studies to assess functional ability and disability48. Impairments in ADL reflect diminished functional capacity and are predictive of adverse outcomes, including hospitalization, institutionalization, and mortality. A recent study continue to validate the use of ADL as a robust indicator of functional health or self-care49. ADL difficulty was categorized as “no” (0–2 = 0)” or “yes” (3–6 = 1).

For the third dimension of EQ-5D “no” and “yes” were used to code difficulty in instrumental activities of daily living (IADL). IADLs are not always related to a person’s basic functioning but allows them to live independently in a community. IADLs serves as a critical measure of usual activities in older adults, as they encompass tasks essential for independent living within the community if they were experiencing any issues that would persist for longer than three months, such as cooking a hot meal, going grocery shopping, making a phone call, taking medication, cleaning or gardening, handling money (paying bills and keeping track of expenses), or navigating unfamiliar areas or locating an address. Unlike basic ADLs, IADLs reflect an individual’s ability to interact with their environment and maintain social roles, making them highly relevant to assessing usual daily functioning. Limitations in IADLs are often early indicators of cognitive or physical decline and are strongly associated with reduced QoL and increased care needs50.

The fourth dimension of EQ-5D is the pain, which was coded as “no” and “yes.” Pain-related questions were asked to the respondent in LASI, “Are you often troubled with pain”?

Furthermore, the fifth dimension of the EQ-5D measurable variable is depression. Depression-related questions were asked of the respondents to measure the depression symptoms by using the CES-D (Centre for Epidemiological Studies-Depression) scale51. A total of 10 questions were included in this study to assess depression, covering aspects such as trouble concentrating, feeling depressed, fatigue, fearfulness, loneliness, irritability, the sense that everything requires effort, hopelessness, happiness, and overall life satisfaction. These items were converted into binary outcome variables, combined to yield a total score ranging from 0 to 10. Based on the scoring, a total score of 0 to 3 was classified as “not depressed,” while a score of 4 to 10 was categorized as “depressed.”

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was employed to derive a composite variable by using all five dimensions with binary nature variables, with scores ranging from 0 to 0.79. Using the ‘xtile’ command, this variable was categorized into three groups based on their weighted score ranges. These categories were subsequently recoded as low QoL, medium QoL, and high QoL.

Exposure variable

Falls and injuries were assessed as exposure variables using a set of three questions designed to determine the extent and nature of the fall experienced by the individual. Have you fallen in the last two years? “Participants were asked at the start.” “How many times have you fallen in the last two years?” and “Did you injure yourself sufficiently in that fall (or any of those falls) to require medical treatment?” The falls were categorized into three categories no falls, minor falls, and major falls. Injuries were defined as falls that required medical attention. “In the past two years, have you sustained any major injuries?” with a “yes” or “no” response. Moreover, the survey included causes of fall injuries based on the question, “What was the cause of that injury?” Accidents in traffic, being struck by a person or object, fire, flames, burns, electric shock, drowning, poisoning, animal attack or bite, fall, and other responses.

Independent variable

The independent variables of this study were age group, sex, place of residence, level of education, marital status, regions, castes, living arrangement, work status, and monthly per capita expenditure (MPCE) quintile and multimorbidity. Multimorbidity was categorized into three categories. If an individual has no morbidity defined as “No morbidity,” individuals with 1 morbidity defined as “1 morbidity” and individuals with 2 or more morbidity categorised as “2 or more morbidity”.

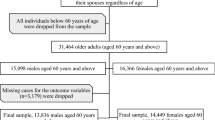

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

This study used the secondary data from the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI), Wave-I (2017-18). The dataset is nationally representative and include information on individuals aged 45 years and above.

Inclusion criteria

In the study sample, we included older people age 60 and above with 31,464 sample of older people out of 72,250 people in India excluding Sikkim, have complete information on variables related to falls, injuries, QoL and other socio-demographic characteristics.

Exclusion criteria

In this study individuals younger than 60 years were excluded, resulting in a total sample of 40,786 older people excluded.

Sample size of the study

After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 31,464 samples of older people were included in the final analysis. Since the study is based on secondary data, no additional sample size calculation was required; instead, we used the available sample from the Individual dataset after cleaning and filtering.

Statistical analysis

The study participants’ general characteristics and distribution were determined using descriptive analysis. The QoL is the outcome of our interest. Furthermore, bivariate analysis has been used to see level of the QoL, falls, and injuries with socioeconomic characteristics of women. The Chi-square test was used to determine if there is a significant association between the socio-demographic characteristics and the QoL. The p-value is a measure to determine whether the relationship between the socio-demographic characteristics and QoL is statistically significant. The principal component analysis (PCA) was used to create the health-related quality of life (HRQOL) index and make a score to create a variable with QoL.

The findings were also carved out using ordered logistic regression analysis. The QoL were categorized as “Low QoL,” “Medium QoL,” and “High QoL.” The ordered logistic regression model is a regression model for a response variable with an ordinal value. The model is based on the response variable’s “cumulative probability.”

An ordered logistic regression model can be written as follows:

Where \(\:{\beta\:}_{0}\:\)is the intercept, \(\:{{\upbeta\:}}_{1},\:{{\upbeta\:}}_{2},\dots\:.\dots\:\dots\:,{{\upbeta\:}}_{k}\:\)are the regression coefficients indicating the relative effect of a particular explanatory variable on the outcome, \(\:{\text{x}}_{1},\:{\text{x}}_{2},\dots\:.\dots\:\dots\:,{\text{x}}_{k}\), were the control variables52. A confidence interval (CI) is a range of values, derived from sample data, that is used to estimate an unknown population parameter, with a specified level of confidence (e.g., 95%), indicating the degree of uncertainty or precision of the estimate.

In Table 5, Model I presented the null model, which indicated the association between QoL and falls. Model II presented the adjusted odds ratio for the QoL of older adults after controlling for all the selected independent variables related to falls. Subsequently, Model III presented the null model assessing the relationship between QoL and injuries among the elderly, while Model IV showed the adjusted odds ratio for QoL after accounting for all selected independent variables associated with injuries. The statistical package STATA for Windows version 14.153 was used for all statistical analyses. The proper individual-level sampling weights were used to make the results representative.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of older people aged 60 and above in India

Table 1 shows that around one-third (30%) of the older persons were aged 60–64 years, followed by 65–69 years (29%). The proportion of females was 53% of the total older population. Approximately 71% of older people resided in rural areas. Over half (56.5%) of the older people were illiterate, and only 14% of older people had more than ten years of schooling. Over two-thirds (62%) of older people were married, and 36% were widowed. Majority (82%) of older people were Hindus. Most older people were from the Southern region (28%), followed by the Eastern region (22%). Regarding the caste, 45% belonged to other backward classes (OBCs) and 19% to scheduled caste, and only 8% were from scheduled tribes.

Regarding health behaviours, 60% of the older people never smoked and 85% of older people never consumed alcohol. Over two-thirds (61%) of the older people lived with a spouse, and one-third (33%) lived with others. Furthermore, 31% of the older people were currently working. Regarding self-rated health status, 45% of older people rated their health as fair, and 24% rated their health as poor. About 22% of older people were from poorer/poorest wealth status, 21% to the middle, 19% to the richer, and 16.5% to the richest. In the case of multimorbidity, 29% of older people had only one disease, and 24% had multimorbidity. Over three-fourths (83%) of the older people reported no fall, and 13% reported a major fall. About 14% of older people reported injuries. According to HRQOL factors, such as ADLs (self-care), mobility, IADLs (usual activities), pain, and depression, majority of older people (92%) reported self-care, more than two-thirds (65%) reported no mobility, 22% reported could not do activities, and 40% reported pain. The majority of the older people (70%) were not depressed. QoL measures showed that about 40% of older people had low QoL, and 30% each had a medium and high QoL.

The sociodemographic differential in falls and injuries among older people in India

Results of Table 2 display that prevalence of falls and injuries tend to increase with age. Serologically, females had higher prevalence of falls (14.4%) than males (10.7%) of whom reported major falls, and they also had higher prevalence of injuries (15.6%). East region people had a higher major fall (17.4%) followed by Central region people (14%) who had a major fall. Similarly, East (19.5%) and Central (14.7%) region people had higher injuries than other region people. While lowest major falls (4.9%) and injuries (6,4%) were found in people from the North-east region. For the type of wealth quintile, the major falls reported (16.9%) were the richest, but the minor falls were low (2.9%), and along with that (15.7%) was the injuries. Furthermore, regarding the number of chronic diseases reported, major falls (16.6%) was two kinds of morbidity, and the reported (16.5%) was injuries.

Distribution of falls and injuries by factors associated with health-related QoL among older people

The results of Table 3 specify that those elderly who could not do self-care (ADLs) by themselves found higher percentages of elderly with minor falls (5.8%), major falls (21.7%), and injuries (22.6%). After that, it was observed that those elderly who could not do their usual activities (IADLs) by themselves had higher percentages of older people with minor falls (5.1%), major falls (17.3%), and injuries (18.4%). Results showed that older people with a high QoL reported the lowest prevalence of minor falls (2.6%), major falls (7.5%), and injuries (7.9%). The results showed that as the QoL of the elderly increased, the level of minor falls, major falls, and injuries declined.

Distribution of QoL with sociodemographic characteristics of older people

Results of Table 4 indicate that all characteristics of older people were found to be statistically significant. The results reveal that people aged 75 + years had the highest percentage with low QoL, and 33% and 37% of older people aged 60–64 had a higher percentage of medium and high QoL, respectively. In the case of sex of the elderly, it was observed that the highest percentage (47%) of women had low QoL, whereas about 31% of men had a low QoL, and 32% and 37% of males had medium and high levels of QoL, respectively, whereas about 29% and 24% of females had medium and high levels of QoL. The results showed that people with higher levels of education had higher percentage of medium and high QoL. More than 44% of people with more than 10 years of level of education had higher percentage of QoL About 35% of older adults with current marital status had high level of QoL Region showed an interesting result, people from the North region (38%) had high QoL, people from North-east region (35%) had medium level of QoL and east region (46%) people had the lowest level of low QoL. Moreover, the results of living arrangements show that the majority (49.6%) of elderly living with others but not spouses or children had a low QoL, whereas 32% and around 35% of elderly living with spouses had medium and high QoL, respectively. Those women who had reported major falls (51.2%) and minor falls (51.1%) were found to have the lowest QoL, while older people with major falls had the highest level of medium QoL, and those elderly who reported no falls were found to have the highest level (32.5%) of high QoL. At the end of this result, it was found that older people with no morbidity had the highest level (37%) of high QoL, whereas older people with one morbidity had the highest level (32%) of medium QoL, and women with 2 + morbidity had the lowest level (52%) of low QoL.

Association of falls and injuries with QoL among older people aged 60 and above

Table 5 results for Models I and III showed the unadjusted odds ratio for falls and injuries, respectively. The Model, I result for falls showed that older people with minor falls were found 45% less likely to have higher QoL as compared to older people with no falls, and older people with major falls were found to be 47% less likely to have higher QoL as compared to those older people with no falls. Afterward, after controlling other sociodemographic and health factors, Model II results showed that older people with minor falls were 30% less likely to have higher QoL than older people with no falls. Furthermore, older people with major falls were 39% less likely to have higher QoL.

Following that, in model III result, which is a crude result for injury, revealed that older people with injuries were 46% less likely to have higher QoL than those without injuries. In addition, after controlling for all other variables, Model IV revealed that older people with injuries were 35% less likely to have higher QoL than those without injuries.

The results of the controlling factors were also statistically significant for falls and injuries. The results of models II and model IV showed that as older people age increases, the chances of having higher QoL decreases significantly among those older people who have fallen and been injured. Regarding the sex of the elderly, the results showed that older females were 31% and 32% less likely to have higher QoL than elderly males. Older people who lived in urban areas and had good education were more likely to be able to lead a good life. The results showed that urban people were 1.25 times more likely to have higher QoL than rural people. The education level showed that older people with more than 10 years of schooling were 2.44 times more likely to have higher QoL than illiterate people. The region-wise results suggest that people from the east region were 46% less likely to have falls and injuries than the north region people whereas south region people were only 19% less likely to have falls and injuries than the north region. Those living with a spouse had a 1.17 times higher likelihood of QoL than older people living alone. Furthermore, as older people’s wealth status increases, the chances of having higher QoL rise significantly. The higher the morbidity, the lower the possibility of having higher QoL. Results for cut1 represents the threshold boundary between the first and second categories (e.g., low vs. medium/high), and cut2 represent the threshold boundary between the second and third categories (e.g., low/medium vs. high).

Discussion

This study examined the linkage of quality of life (QoL) with falls, and injuries among older people in India. This study identified the key factors associated with falls and injuries among older people in India. The findings suggest that sex, living arrangement, place of residence, work status, multimorbidity, and QoL were significantly related to falls and injuries. The study’s findings show that more than half of the respondents were older women. More than 70% of older people were residing in rural areas and more than 50% of older people were illiterate, and more than two-thirds of older people lived with their spouses. Over 50% of older people were suffering from either one or multimorbidity; 29% with single morbidity, and 24% with multimorbidity. About 13% had experienced falls and 14% experienced injuries.

There are five stages in the human life cycle: childhood, adolescence, youth, adulthood, and old age. Old age is the last stage of human life. At this stage, the health is naturally more declines. So, this research aimed to examine the relationship between QoL, falls, and injuries among older people in India. QoL has become the most critical issue in recent times. Several background characteristics directly impact the QoL54,55. With increasing age of people, the chances of falls and injuries also increases, causing the lower QoL. This study findings showed that older people with major falls were 39% less likely to have a better QoL than those without falls. Similar studies from Taiwan, Norway, and Germany indicate that due to falls, older people lose their QoL56,57 and some studies from India report the same pattern58,59. Besides these, one of the medical studies from Soudi Arabia also revealed that falls was the negative contributors for the QoL of the older persons60. Likewise, in the case of injuries, findings also indicate that older people with injuries were 35% less likely to have a better QoL than older people with no injuries; some similar studies from Korea, North India, and the United Kingdom suggest that the QoL of older people diminished and make them more vulnerable in the society elderly to those elderly with injuries22,61,62. Together, these findings highlight the significant negative impact of falls and injuries on the QoL of older people in India.

Furthermore, older people aged 75 and above who experience of falls and injuries were 49% less likely to have a better QoL than those 60–64 years old in India. This finding showed that with increasing age, different health issues arise, such as illness, diseases, etc. which caused low QoL in later life63,64. Female respondents were more likely to report poorer QoL, reflecting gender disparities in Indian society65. Urban residents had a 25% higher likelihood of better QoL than rural residents. In urban areas, people can efficiently access services, facilities, and basic amenities66. In contrast, community-based studies from urban slum and urban Puducherry in India suggest that lack of physical activity and burden of multimorbidity reflect in their life as poor QoL67,68.

Higher education levels were linked to a better QoL, with those educated for over ten years experiencing 2.4 times higher QoL than illiterate individuals. Education raises awareness and empowers both individuals and society, contributing to improved well-being69. Married older people had a better QoL than widowed or single individuals, possibly due to mutual support in later life70 Economic status also played a role: those with higher monthly per capita expenditure enjoyed better QoL, reflecting greater access to resources and services41,42,43,44,48,66,72.

Morbidity remains a key factor directly reducing QoL71. Older people with one morbidity were 36% less likely to have better QoL, and those with two or more were 62% less likely than those without any morbidity. As morbidities increase, they strain physical, mental, and financial well-being, leading to a decline in QoL72. These findings align with findings from other Indian studies, which reported that higher age, female gender, rural residence, widowerhood, lower education level, Scheduled Tribe, Muslims, rich household wealth status, east and south region, and multimorbidity condition were associated with poorer HRQOL47. The recent studies from rural areas of India indicates that age, lower economic status, divorce, multimorbidity conditions, female gender, and physically inactive are linked to poor QoL73,74,75,76.

A Key limitation of the study is its cross-sectional design, which restrict the causal inference. Additionally, reliance on self-reported data for health outcomes may introduce reporting bias. Despite these limitations, the study addresses a critical research gap in understanding the QoL-related to falls and injuries in India and offers findings that are generalizable at the national level. India’s older adults should be provided with improved QoL through nationwide fall prevention programs, enhanced healthcare access, safe living environments, and strengthened social support systems. Awareness campaigns on fall risks and prevention strategies should be promoted, with regular monitoring for effectiveness.

Conclusions

The findings of this study revealed that various factors significantly influence the QoL among older adults concerning falls and injuries. Major falls were associated with a notable decline in QoL, particularly among those with advancing age, unmarried status, and multiple morbidities, all of which showed a significant negative correlation. In contrast, higher education, better living arrangements, urban residence, and greater monthly per capita expenditure were positively associated with improved QoL. These results highlight the importance of identifying and addressing factors that adversely affect QoL, enabling older adults to lead healthier and more fulfilling lives. Additionally, adopting safety measures and enhancing social participation were found to support better QoL outcomes. To reduce fall-related risks and improve overall well-being, both older individuals and their families should be educated on preventive strategies, and targeted interventions should be implemented.

Data availability

This study utilizes a secondary data source of data that is freely available by using the given link by registration and login to request the data set for use. [https://www.iipsdata.ac.in/datacatalog\_detail/5](https:/www.iipsdata.ac.in/datacatalog_detail/5). The data request form can be easily downloaded by given link ([*LASI Wave 1 Data Request form (iipsindia.ac.in)](https:/iipsindia.ac.in/sites/default/files/LASI_DataRequestForm_0.pdf)).

Abbreviations

- HRQOL:

-

Health-related Quality of Life

- QoL:

-

Quality of Life

- MPCE:

-

Mean Per Capita Expenditure

- ADL:

-

Activities of Daily Living

- IADL:

-

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

- CESD-scale:

-

Centre for Epidemiological Studies-Depression-scale

- EQ-5D:

-

Euro-QOL five dimensions questionnaire

- VAS:

-

Visual Analog Scale

- MPCE:

-

Monthly Per Capita Expenditure

References

Scott M. Planning for Age-Friendly Cities: Edited by Mark Scott. Planning Theory & Practice. (2021). 27;22(3):457 – 92 https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2021.1930423

World Population Prospects - Population Division. - United Nations. https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/

IIPS, N. & MoHFW, H. S. USC. Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI) Wave 1, 2017–18, India Report. International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai: International Institute for Population Sciences, National Programme for Health Care of Elderly, MoHFW, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health and the University of Southern California. Accessed from: (2020). https://www.iipsindia.ac.in/sites/default/files/LASI_India_Report_2020_compressed.pdf

World Health Organization & Fall Fact Sheets (2021). Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/falls

World Health Organization. Ageing, Life Course Unit. WHO Global Report on Falls Prevention in Older Age (World Health Organization, 2008).

Tinetti, M. E. & Kumar, C. The patient who falls: It’s always a trade-off. Jama. (2010). 20;303(3):258 – 66 https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.2024

Liu, M. & So, H. Effects of Tai Chi exercise program on physical fitness, fall related perception and health status in institutionalized elders. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing. 2008 1;38(4):620-8. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2008.38.4.620

Biswas, I., Adebusoye, B. & Chattopadhyay, K. Health consequences of Falls among older adults in India: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Geriatrics. (2023). 18;8(2):43 https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics8020043

Singh, R. R. & Maurya, P. Visual impairment and falls among older adults and elderly: evidence from longitudinal study of ageing in India. BMC public health. (2022). 12;22(1):2324 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14697-2

Thakkar, S. & Srivastava, S. Cross-sectional associations of physical frailty with fall, multiple falls and fall-injury among older Indian adults: findings from LASI, 2018. PLoS One. 17 (8), e0272669. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0272669 (2022).

Patil, D. S., Bailey, A., George, S., Ashok, L. & Ettema, D. Perceptions of safety during everyday travel shaping older adults’ mobility in Bengaluru, India. BMC public health. (2024). 19;24(1):1940 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19455-0

Ravindran, R. M. & Kutty, V. R. Risk factors for fall-related injuries leading to hospitalization among community-dwelling older persons: a hospital-based case-control study in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India. Asia Pac. J. Public. Health. 28 (1_suppl), 70S–6S. https://doi.org/10.1177/1010539515611229 (2016).

Choi, K. W. & Lee, I. S. Fall risk in low-income elderly people in one urban area. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing. (2010). 1;40(4):589 – 98 https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2010.40.4.589

Murphy, S. L., Williams, C. S. & Gill, T. M. Characteristics associated with fear of falling and activity restriction in community-living older persons. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 50 (3), 516–520. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50119.x (2002).

Suzuki, M., Ohyama, N., Yamada, K. & Kanamori, M. The relationship between fear of falling, activities of daily living and quality of life among elderly individuals. Nurs. Health Sci. 4 (4), 155–161. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1442-2018.2002.00123.x (2002).

Gill, T. M., Murphy, T. E., Gahbauer, E. A. & Allore, H. G. Association of injurious falls with disability outcomes and nursing home admissions in community-living older persons. American journal of epidemiology. (2013). 1;178(3):418 – 25 https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kws554

Öztürk, Z. A., Özdemir, S., Türkbeyler, I. H. & Demir, Z. Quality of life and fall risk in frail hospitalized elderly patients. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 47 (5), 1377–1383. https://doi.org/10.3906/sag-1610-107 (2017).

Vieira, E. R., Palmer, R. C. & Chaves, P. H. Prevention of falls in older people living in the community. Bmj https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i1419 (2016). 28;353.

Tripathy, N. K., Jagnoor, J., Patro, B. K., Dhillon, M. S. & Kumar, R. Epidemiology of falls among older adults: A cross sectional study from Chandigarh, India. Injury. (2015). 1;46(9):1801-5 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2015.04.037

Jia, H. et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and burden of disease for falls and balance or walking problems among older adults in the US. Preventive medicine. (2019). 1;126:105737 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.05.025

Van Dijk, P. T., Meulenberg, O. G., Van de Sande, H. J. & Habbema, J. D. Falls in dementia patients. The Gerontologist. (1993). 1;33(2):200-4 https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/33.2.200

Jagnoor, J. et al. Mortality and health-related quality of life following injuries and associated factors: a cohort study in Chandigarh, North India. Injury prevention. (2020). 1;26(4):315 – 23 https://doi.org/10.1136/injuryprev-2019-043143

Moylan, K. C. & Binder, E. F. Falls in older adults: risk assessment, management and prevention. The American journal of medicine. (2007). 1;120(6):493-e1 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.07.022

Lord, S. R., Smith, S. T. & Menant, J. C. Vision and falls in older people: risk factors and intervention strategies. Clinics in geriatric medicine. (2010). 1;26(4):569 – 81 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2010.06.002

Public Health Agency of Canada. Division of Aging, Seniors. Report on seniors’ falls in Canada (Division of Aging and Seniors, Public Health Agency of Canada, 2005).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Fatalities and injuries from falls among older adults—United States, 1993–2003 and 2001–2005. MMWR: Morbidity Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 55 (45), 1221–1224 (2006). PMID: 17108890.

Kaur, R. et al. Burden of falls among elderly persons in india: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Natl. Med. J. India. 33 (4), 195–200 (2020).

Joseph, A., Kumar, D. & Bagavandas, M. A review of epidemiology of fall among elderly in India. Indian journal of community medicine. 1;44(2):166-8. (2019).

Talbot, L. A., Musiol, R. J., Witham, E. K. & Metter, E. J. Falls in young, middle-aged and older community dwelling adults: perceived cause, environmental factors and injury. BMC public. Health. 5, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-5-86 (2005).

Ruchinskas, R. Clinical prediction of falls in the elderly. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. (2003). 1;82(4):273-8 https://doi.org/10.1097/01.PHM.0000056990.35007.C8

Graafmans, W. C. et al. Falls in the elderly: a prospective study of risk factors and risk profiles. American journal of epidemiology. (1996). 1;143(11):1129-36 https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008690

Mane, A. B., Sanjana, T., Patil, P. R. & Sriniwas, T. Prevalence and correlates of fear of falling among elderly population in urban area of Karnataka, India. J. mid-life Health. 5 (3), 150. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-7800.141224 (2014).

Bhoomika, V., Chandrappa, M. & Reddy, M. M. Prevalence of fall and associated risk factors among the elderly living in a rural area of Kolar. Journal of family medicine and primary care. (2022). 1;11(7):3956-60 https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1580_21

Woolf, A. D. & Åkesson, K. Preventing fractures in elderly people. bmj. (2003). 10;327(7406):89–95 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7406.89

Brown, G. C. Living too long: the current focus of medical research on increasing the quantity, rather than the quality, of life is damaging our health and harming the economy. EMBO Rep. 16 (2), 137–141. https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.201439518 (2015).

Roe, B. et al. Older people and falls: health status, quality of life, lifestyle, care networks, prevention and views on service use following a recent fall. J. Clin. Nurs. 18 (16), 2261–2272. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02747.x (2009).

McLean, D. & Lord, S. Falling in older people at home: transfer limitations and environmental risk factors. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 43 (1), 13–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.1996.tb01832.x (1996).

Ruthazer, R. & Lipsitz, L. A. Antidepressants and falls among elderly people in long-term care. Am. J. Public Health. 83 (5), 746–749. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.83.5.746 (1993).

La Grow, S., Yeung, P., Towers, A., Alpass, F. & Stephens, C. The impact of mobility on quality of life among older persons. J. Aging Health. 25 (5), 723–736 (2013).

Bally, E. L. et al. Factors associated with health-related quality of life among community-dwelling older adults: the APPCARE study. Sci. Rep. 21 (1), 14351 (2024).

Stenhagen, M., Ekström, H., Nordell, E. & Elmståhl, S. Accidental falls, health-related quality of life and life satisfaction: a prospective study of the general elderly population. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 1 (1), 95–100 (2014).

Bjerk, M., Brovold, T., Skelton, D. A. & Bergland, A. Associations between health-related quality of life, physical function and fear of falling in older fallers receiving home care. BMC Geriatr. 18 (1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0945-6 (2018).

Korenhof, S. et al. The association of fear of falling and physical and mental health-Related quality of life (HRQoL) among community-dwelling older persons; a cross-sectional study of urban health centres Europe (UHCE). BMC Geriatr. 13 (1), 291 (2023).

Group, T. E. EuroQol-a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 16 (3), 199–208 (1990).

Hays, R. D. & Morales, L. S. The RAND-36 measure of health-related quality of life. Annals of medicine. 1;33(5):350-7. (2001).

Herdman, M. et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual. Life Res. 20, 1727–1736 (2011).

Ahamad, V. & Bhagat, R. B. Differences in health related quality of life among older migrants and nonmigrants in India. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 4042 (2025).

Katz, S., Ford, A. B., Moskowitz, R. W., Jackson, B. A. & Jaffe, M. W. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA 185 (12), 914–919 (1963).

Stuck, A. E. et al. Risk factors for functional status decline in community-living elderly people: a systematic literature review. Soc. Sci. Med. 48 (4), 445–469 (1999).

Njegovan, V., Man-Son-Hing, M., Mitchell, S. L. & Molnar, F. J. The hierarchy of functional loss associated with cognitive decline in older persons. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 56 (10), M638–M643. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/56.10.M638 (2001).

Andresen, E. M., Malmgren, J. A., Carter, W. B. & Patrick, D. L. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of. Prev. Med. 10, 77–84 (1994).

Ryan, T. P. Modern Regression Methods (Wiley, 2008).

StataCorp, L. P. StataCorp Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. StataCorp LP (College Station, TX, 2015).

Talarska, D. et al. Determinants of quality of life and the need for support for the elderly with good physical and mental functioning. Med. Sci. Monitor: Int. Med. J. Experimental Clin. Res. 19, 24:1604 (2018).

Rajput, M., Kumar, S. & Ranjan, R. Determinants of quality of life of geriatric population in rural block of Haryana. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care. 1;11(9):5103-9. (2022).

Tsai, Y. J., Sun, W. J., Yang, Y. C., Chou, P. & Wang, J. D. Associations of falls with quality of life and correlated factors in community-dwelling older adults: a two-wave cohort study. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-966827/v1

Thiem, U. et al. Falls and EQ-5D rated quality of life in community-dwelling seniors with concurrent chronic diseases: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 12 (1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-12-2 (2014).

Mishra, N., Mishra, A. K. & Bidija, M. A study on correlation between depression, fear of fall and quality of life in elderly individuals. Int. J. Res. Med. Sci. 5 (4), 1456–1460 (2017).

Prasad, J. D. et al. Quality-of-life among elderly with untreated fracture of neck of femur: a community based study from Southern India. J. Family Med. Prim. Care. 2 (3), 270–273 (2013).

Vennu, V. & Bindawas, S. M. Relationship between falls, knee osteoarthritis, and health-related quality of life: data from the osteoarthritis initiative study. Clin. Interv. Aging. 8, 793–800 (2014).

Kwak, Y. & Ahn, J. W. Health-related quality of life in older women with injuries: a nationwide study. Front. public. Health. 11, 1149534. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1149534 (2023).

Lyons, R. A. et al. Measuring the population burden of injuries—implications for global and National estimates: a multi-centre prospective UK longitudinal study. PLoS Med. 8 (12), e1001140. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001140 (2011).

Nagarkar, A. & Kulkarni, S. Association between daily activities and fall in older adults: an analysis of longitudinal ageing study in India (2017–18). BMC Geriatr. 22 (1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-02879-x (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Successful ageing is associated with falls among older adults in india: a large population based across-sectional study based on LASI. BMC Public. Health. 24, 1682. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19181-7 (2024).

Vahtera, J. et al. Sex differences in health effects of family death or illness: are women more vulnerable than men? Psychosom. Med. 68 (2), 283–291. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000203238.71171.8d (2006).

Shucksmith, M., Cameron, S., Merridew, T. & Pichler, F. Urban–rural differences in quality of life across the European union. Reg. Stud. 43 (10), 1275–1289. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400802378750 (2009).

Yogesh, M., Makwana, N., Trivedi, N. & Damor, N. Multimorbidity, health Literacy, and quality of life among older adults in an urban slum in india: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public. Health. 9 (1), 1833 (2024).

Majumdar, A. & Pavithra, G. Quality of life (QOL) and its associated factors using WHOQOL-BREF among elderly in urban Puducherry, India. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research: JCDR. 12;8(1):54. (2014).

Veenhoven, R. The four qualities of life. Ordering concepts and measures of the good life. Underst. Hum. well-being. 1, 74–100 (2006).

Wang, H., Kindig, D. A. & Mullahy, J. Variation in Chinese population health related quality of life: results from a EuroQol study in Beijing, China. Qual. Life Res. 14 (1), 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-004-0612-6 (2005).

Muhammad, T. & Rashid, M. Prevalence and correlates of pain and associated depression among community-dwelling older adults: Cross‐sectional findings from LASI, 2017–2018. Depress. Anxiety. 39 (2), 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23239 (2022).

Arokiasamy, P. & Uttamacharya, Jain, K. Multimorbidity, functional limitations, and self-rated health among older adults in india: cross-sectional analysis of LASI pilot survey, 2010. Sage Open. 5 (1), 2158244015571640. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015571640 (2015).

Singh, A., Palaniyandi, S., Palaniyandi, A. & Gupta, V. Health related quality of life among rural elderly using WHOQOL-BREF in the most backward district of India. J. Family Med. Prim. Care. 11 (3), 1162–1168 (2022).

Muralidhar, M. K. et al. Morbidities among elderly in a rural community of coastal karnataka: a cross-sectional survey. J. Indian Acad. Geriatics. 10, 29–33 (2014).

Rao, R., Yankannavar, B. & Naik, B. Quality of life and its associated factors among the elderly community dwellers in rural bihar–a community-based cross-sectional study from Eastern India. Natl. J. Community Med. 15 (07), 533–540 (2024).

Himanshu, H., Arokiasamy, P. & Selvamani, Y. Association Between Multimorbidity and Quality of Life Among Older Adults in Community-Dwelling of Uttar Pradesh, India.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to LASI- IIPS for making the data available for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K.P. has contributed to conceptualization, investigation, and data curation, as well as writing the original draft of the manuscript. S.K.P. has helped with the analysis and chosen the methodology used in the manuscript. S.K.P. also supervised, validated, and contributed to writing & reviewing, and editing the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Due to the fact that it is secondary data, the first wave of the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India is freely accessible on the IIPS website. Ethics clearance is not required. Report experiments involving the use of human embryonic stem cells, human embryos and gametes, and related materials were not required for the manuscripts. Every method was used in accordance with the applicable rules and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pal, A.K., Pal, S.K. Linkages of quality of life with falls and injuries among older people in India. Sci Rep 15, 45240 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29486-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29486-1