Abstract

Cancer remains a major global health issue, causing numerous deaths annually. Standard treatments like chemotherapy and radiotherapy often exhibit cytotoxic characteristics, harming healthy cells and leading to significant side effects. In this context, anticancer peptides (ACPs) offer a promising strategy by specifically triggering apoptosis in cancer cells while protecting healthy tissues. However, the experimental screening process for new ACPs involves significant costs and requires considerable labor. To address these challenges, we propose an advanced computational framework: AttBiLSTM_DE, which combines an Attention-based Bidirectional LSTM architecture with Optimized Weighted Features for accurate ACP predictions. Firstly, we employed four NLP-based feature encoding techniques: One-Hot Encoding, Global Vectors (GloVe), fastText, and Word2Vec to convert peptide sequences into numerical representations. Additionally, k-mer embedding was used to help the model recognize important subsequence fragments within the sequences. Then, we also developed a stochastic Differential Evolution (DE) algorithm to construct hybrid features, optimize feature weights, and generate the most informative attributes. Finally, the weighted feature sets were analyzed with a Bidirectional LSTM model augmented by an attention mechanism. This bidirectional architecture effectively captures contextual dependencies from both preceding and succeeding peptide sequences, while the attention mechanism emphasizes the most pertinent aspects, thus enhancing the model’s prediction performance. Through extensive evaluation, our proposed AttBiLSTM_DE outperformed conventional attention-based deep learning models in predictive performance, achieving an accuracy of 95.85% and an AUC of 98.48%. These impressive results indicate that our AttBiLSTM_DE effectively predicts ACPs and is able to aid in further cancer treatment and drug development. Furthermore, we have developed an online web server to enable real-time prediction based on our proposed model, which is publicly accessible at: https://att-bi-lstm-de-acp.vercel.app/

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer is one of the deadliest diseases and a significant public health challenge, affecting millions of individuals worldwide1,2.In 2023, the WHO reported 20 million new cancer cases and 10 million related deaths, emphasizing the need for effective prevention, diagnostic, and treatment efforts3. According to predictions, by 20504, there could be 35.3 million cancer diagnoses and 20 million fatalities. This suggests a 76.6% rise in cancer incidence and nearly doubled fatality rate from 2022. This predicted increase emphasizes how urgently comprehensive public health policies, strong early detection initiatives, and creative therapy approaches are needed5,6.Cancer arises when abnormal cells multiply uncontrollably, often due to genetic defects7,8. Some mutations are inherited, but most are induced by lifestyle and environmental changes9. Remarkably, tobacco smoking still causes 22% of cancer deaths10,11. Other risk factors include obesity, improper diet, sedentary lifestyles, excessive alcohol consumption, and carcinogenic microbe infections12,13. It is essential to address these modifiable drivers to enhance patient outcomes and reduce cancer globally.

Traditional cancer treatments like surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation have played a crucial role in fighting cancer14,15,16, but they do have their downsides like methods may harm normal cells and cause serious side effects like infections and immunosuppression17,18. Chemotherapy and radiation can harm healthy cells, resulting in side effects like fatigue and nausea19,20,21. Some cancers may lose their effectiveness over time due to resistance to different treatments. Despite improved treatments, millions of people die from cancer every year22,23,24. The high death rate indicates that we need new and more effective treatments, even with existing ones.

In this context, anticancer peptides (ACPs)25 are a feasible cancer treatment alternative. ACPs, short amino acid sequences of 10 to 60, are generated from the biological immune system and can target and cause apoptosis in neoplastic cells while preserving non-malignant cells. This concentrated approach removes standard cancer treatment side effects and reduces cytotoxicity. They also generate cancer cell resistance less than typical pharmacological treatments26,27. They work by inducing apoptosis, damaging the membranes of cancer cells, preventing angiogenesis, and modifying immunological responses28. ACPs are essential in the battle against cancer because they provide hope for more patient-friendly and efficient treatments29,30.

Over the past decade, significant advancements have been made in the design and evaluation of peptide-based cancer therapies31,32,33. Discovering new anticancer peptides is crucial. Unfortunately, these peptides are rarely employed in medicine due to strict testing and approval requirements34. Lab testing for new ACPs is costly, time-consuming, and resource-intensive35. Bioinformatics, or computer-based technology, can speed up discoveries here. Advanced DL and ML methods have replaced traditional experimental methods. For example, Ruifen Cao et al.36 developed a dual-channel deep neural network to efficiently predict anticancer peptides. ACPs like brevinin were discovered through costly methods. Tyagi et al.37 introduced CancerPPD that listed 3,491 validated ACPs, and CancerPPD2.038 expanded this to over 6,500. Moving to the traditional ML, like Tyagi et al.39 designed AntiCP, which focuses on developing computational models to predict novel anticancer peptides using machine learning, specifically support vector machines, achieving around 91% accuracy, and including a web server for mutation prediction and virtual screening. Chen et al. produced iACP40, which used g-gap dipeptide encoding and SVM. It was better than previous tools in terms of both accuracy and stability. With these web servers, it was easy to quickly screen candidate peptides. AntiCP 2.041 was released, which used the composition of dipeptides and amino acids to improve design rules. Its best model, an Extra-Trees classifier on dipeptide characteristics, achieved an AUROC of 0.97 on training data. Vijayaku Mar and Lakshmi42 created ACPP, a prediction method that uses compositional information, centroidal, and distributional metrics of amino acids to forecast ACPs more accurately. Park et al.43 released MLACP 2.0 that uses a CNN-based meta-classifier that combines scores from 67 different baseline models using various peptide encodings. This approach surpasses earlier machine learning tools in performance. Other meta and pipeline methods, such as mACPpred (2019)44 and its updated version, mACPpred 2.0 (2024)45, also combined various classifiers and features. The latest version outperformed not just its predecessor but also other industry-leading tools by introducing 1D convolutional neural networks (1D-CNNs) and protein language embeddings within a layered DL framework.

Between 2019 and 2024, DL models, particularly CNNs, emerged as crucial tools for ACP prediction, effectively learning features from sequences in an automated manner. The ACP-MHCNN model, developed by Sajid Ahmed et al.46, is a multi-headed convolutional neural network that incorporates BPF, physicochemical, and evolutionary inputs, resulting in an accuracy enhancement of around 6% over previous models. In a similar vein, Chen et al.47 proposed xDeep-AcPEP in 2021 , utilized a CNN with multitask learning to forecast continuous potency values (IC50, EC50, etc.) across six cancer cell lines; the models attained a Pearson (\(\rho \approx 0.81\)) and offered residue-level interpretability through feature-importance mapping. Han et al.48 employed bidirectional LSTM layers, enhanced with attention mechanisms, on concatenated amino-acid property encodings- ACPred-BMF , achieving state-of-the-art performance. Liu et al.49 developed an ensemble of deep models, named AntiMF , utilizing “multi-view” CNNs to collect complimentary characteristics, hence enhancing performance beyond that of single-network models. Certain studies focus on data scarcity, which was mitigated through augmentation. For instance, Bhattarai et al.50 enhanced training samples using Gaussian oversampling and implemented AdaBoost, proposing ACP-ADA in 2022, which improved accuracy and MCC by approximately 5–9% compared to prior ml methods. Xiaofang et al. proposed pretrained transformer-based methods like ACP-DRL51 refine a BERT-like language model using Bi-LSTM classifiers; this deep representation learning eliminates human features and is on par with or better than existing predictors. The model is pre-trained on about 1.5 million in-domain unlabeled peptides. Likewise, Yue et al. integrate wavelet denoising, a cascade deep forest classifier, and embeddings from pretrained protein language models (ProtT5, ESM-2). They built PLMACPred52, employed SHAP analysis to identify important motifs, and performed significantly better than previous models. Furthermore, by experimentally validating 37 peptides, Yuan et al.53 developed a deep CNN and a large-scale peptide mining strategy—showed its effectiveness by concluding that one (tPep14) was effective in mice while exhibiting no toxicity. In summary, the discipline has evolved from traditional manual detection methods to scalable, data-driven approaches for ACP identification, leveraging ml and dl techniques. This progression highlights the importance of ensemble learning, transfer learning, and experimental validation to ensure applicability in real-world scenarios.54,55,56. A recent article indicates that mACPpred 2.045 achieved an accuracy of 85.7% on a standard independent dataset. Therefore, our goal is to present a new model that surpasses all of the performance indicators of that and the other studies that have already been done related to ACP prediction.

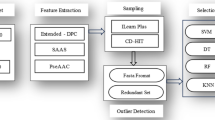

Recent advances in deep learning and biological sequence analysis have significantly improved the prediction of ACPs. However, many existing models rely on single encoding strategies, which limits their ability to capture both contextual and structural information from peptide sequences. To address these limitations, we present a novel predictive framework that develops an Attention-based BiLSTM model featuring optimized weighted attributes. This model accurately predicts anticancer peptides by integrating multi-scale feature representations, including One-hot encoding, fastText, and GloVe. A key innovation of our approach is the identification of the best feature extractor and the creation of a hybrid feature set. Additionally, we utilize a Logistic Regression-guided Differential Evolution (DE) algorithm to dynamically optimize feature weights before model training. This evolutionary weighting mechanism enables the model to automatically prioritize the most discriminative dimensions within a high-dimensional fused feature space, rather than treating all features uniformly. This study is the first to integrate DE-guided feature optimization with attention-enabled BiLSTM networks for ACP prediction, showcasing superior performance and interpretability compared to current leading models. We then carefully selected the optimal hybrid feature and input it into our proposed AttBiLSTM_DE model to accurately predict the ACPs. Finally, we evaluated our model using performance metrics that demonstrate its robustness and efficiency. The diagram in Fig. 1 illustrates the workflow of our complete model architecture.

A schematic diagram that illustrates our proposed framework. Each sub-block signifies the sequential steps undertaken throughout the entire pipeline. The left sub-blocks represent the processes of dataset preparation and feature extraction, while the right sub-blocks correspond to the selection and construction of the best classifier.

Materials and methods

Dataset description

The data set primarily used in this research was initially created and released by the authors of the paper45, which gathered it from 11 recognized anticancer peptide (ACP) prediction methods. The methods are ACP-DL, ACP-MLC57, ACPred, AntiCP 2.0, CpACpP, MLACP, MLACP 2.0, mACPpred, ACPred-Fuse58, ACPred-FL, and AMPfun58. We used this dataset and conducted preprocessing and experiments to ensure data quality and accurate predictions. Here, the ACPs are labeled as “positive” using ‘1’ and the non-ACPs are labeled as “negative” using ‘0’. Initially, sequences containing non-standard or ambiguous amino acids (Z, J, O, U, B, X) were excluded. Redundant sequences and those with extreme lengths (less than 5 or more than 50 amino acids) were also removed. To reduce sequence similarity and avoid bias in performance evaluation, CD-HIT59 clustering was applied with an 85% similarity threshold. This resulted in a refined dataset comprising 1,176 ACPs and 4,001 non-ACPs, from which 1,176 non-ACPs were randomly chosen for the training set to ensure balanced classes. The dataset used for the independent assessment of the model includes 610 ACPs and 2,760 non-ACPs. Further details about the training and independent test datasets are available in the article by Vinoth et al.45. To enhance our preprocessing efforts, we implemented sequence encoding techniques using the primary dataset. This step allowed us to convert raw data into a more structured format, facilitating better analysis and interpretation of the underlying patterns. More detailed information of our preprocessed datasets can be found in the supplementary file Figs. 1 and 2.

Sequence encoding

In this study, we applied four widely used encoding methods60,61—One-Hot Encoding, Word2Vec, FastText, and GloVe—to convert peptide sequences into vector representations. Furthermore, we employed k-mer-based segmentation methodologies in conjunction with these techniques, partitioning sequences into overlapping k-length subsequences (k-mers) to effectively capture local patterns. For instance, a protein sequence such as “ARNDC” can be split into overlapping segments according to the k-mer length. When using 3-mers, it generates: “ARN,” “RND,” and “NDC.” Likewise, with 2-mers, the sequence is transformed into: “AR,” “RN,” “ND,” and “DC.” We generated k-mer embeddings for 1-mer to 6-mer variants using four encoding methods to evaluate their effectiveness. This multi-scale segmentation enables models to capture both short and long contextual patterns in peptide sequences, enhancing the feature space. The input feature vector for our proposed model was created by combining various representations generated from One-Hot, fastText, and GloVe encodings. Specifically, the One-Hot encoding with a k-mer size of 3 resulted in a 15,942-dimensional feature vector for each sequence, considering a maximum sequence length of 1,176 and 20 amino acids. Additionally, both the fastText and GloVe embeddings contributed an extra 512-dimensional representation, which was obtained by averaging over 3-mer windows. Consequently, the initial fused feature vector contained a total of 16,966 dimensions.

One hot encoding

One-hot encoding62 is a crucial technique used to convert categorical variables into numerical vectors that ML algorithms can easily interpret. In the context of protein sequences, each of the 20 standard amino acids is represented by a unique binary vector of fixed length. In this representation, a single position in the vector is set to “1” to indicate the presence of a specific amino acid, while all other positions are filled with “0.” For instance, Alanine (“A”) might be encoded as [1, 0, 0, ..., 0], whereas Arginine (“R”) would be [0, 1, 0, ..., 0]. When applied to an entire protein sequence of length LLL, this process generates a two-dimensional binary matrix The one-hot encoded matrix for a protein sequence of length L can be represented as:

where each row corresponds to one amino acid and preserves the sequential order of residues.

Mathematically, for each amino acid \(a_i\) at position i in the sequence, the one-hot vector \(\textbf{v}_i \in \{0,1\}^{20}\) is defined as:

This ordered and sparse method of data representation offers a clear and unbiased way to encode information about amino acids. While one-hot encoding simplifies data by avoiding redundancy, it can create large, sparse matrices with long sequences. To address this, it is often combined with embedding methods, which create dense vectors that capture meaningful relationships.

Word2Vec

Word2Vec63 was developed by a team at Google, led by Tomas Mikolov , for the purpose of training word embeddings. This employs techniques such as skip-grams and continuous bag of words (CBOW) for its implementation. In the field of bioinformatics64,65,66 techniques have been adapted to analyze protein sequences by interpreting them as sentences comprised of “words,” where each word corresponds to a k-mer subsequence of amino acids. To measure the similarity between two words, it uses cosine similarity; the closer the angle, the more alike the meanings of the words. Among the two variants (Continuous Bag of Words -CBOW and Skip-Gram) of Word2Vec63,67, in our study, we employed the CBOW method (Fig. 2) to convert peptide sequences into a machine-readable format.

The CBOW model predicts a target word, like a k-mer or amino acid token, using a context window of surrounding words, which is useful in bioinformatics due to the contextual relationships found in peptides, similar to natural language. The CBOW model operates by maximizing the probability of accurately predicting a central word \(w_t\) based on the context of surrounding words \(\{ w_{t-c}, \ldots , w_{t-1}, w_{t+1}, \ldots , w_{t+c} \}\). The formal objective function associated with this model is defined as follows:

Where, T represents the overall count of words (or k-mers) in the sequence collection and c represents the dimension of the context window. To facilitate training, the softmax function is employed to compute the conditional probability:

Where, \(v_{\omega _t}\) represents the output vector corresponding to the target word \(w_t\), encapsulating its semantic meaning within the context, h denotes the average of the embeddings for the surrounding context words, serving as a crucial element in capturing the contextual nuances and W signifies the total number of distinct words present in the vocabulary, providing a framework within which the relationships between these words can be understood.

GloVe

The GloVe68 approach to word embedding in natural language processing was first introduced by Pennington and colleagues at Stanford. It uses a co-occurrence matrix69 to derive the semantic relationships between words. This matrix tracks the co-occurrence frequency of two words (k-mer fragments of amino acid sequences) within a specific context. Let \(x_{ij}\) be the count of how often word j appears near word i. The model aims to find vector representations \(w_i\) and \(w_j\) such that their dot product estimates the logarithm of their co-occurrence frequency:

Where \(w_i\) and \(w_j\) are word and context word vectors, \(b_i\) and \(\tilde{b}_j\) are bias terms, and \(f(X_{ij})\) is a weighting function to down-weight very frequent co-occurrences which is generally defined as equation: 6,

For instance, k-mer sequences (like “LKR” and “LKS”) are mapped to vectors that lie close in the multidimensional space. In our study, we applied GloVe on protein sequences to break down into overlapping k-mers (from 1-mer to 6-mer). These k-mers were treated as “words” and trained using a co-occurrence matrix. This matrix is built from the dataset of ACPs and non-ACPs. So, the embeddings effectively captured the relevant patterns and increased the performance of our deep learning classifier.

FastText

Word2Vec model developed by Facebook AI Research70 whose ability to generate embeddings for sub-word units allows for better handling of morphologically rich and rare sequences, thereby providing a more nuanced understanding of peptide characteristics. This approach enhances the understanding of biological sequences and helps identify patterns in rare or new k-mers. To clarify this concept, we utilized the sequence “ATCAG” as an illustrative example. This sequence can be represented through 3-grams as <AT, CAG, TAG, ATC, AT>, alongside the original sequence <ATCAG>. The embedding for the entire word (or k-mer) \(\omega\) is calculated by adding together the embeddings of its individual sub-words:

Where \(G\omega\) is the set of character n-grams composing the word \(\omega\) and \(\textbf{z}_g\) is the embedding vector for each n-gram g. This method boosts generalization for altered sequences, essential in anticancer peptide research due to the impact of minor amino acid changes. Hence, we used fastText on k-mer-encoded protein sequences to capture local amino acid patterns and learn effective embeddings from rare fragments.

Feature optimization using differential evolution (DE)

Each sequence’s single-view features capture valuable distinguishing characteristics; however, accurate ML-based ACPs prediction relies on integrating these features into a weighted representation71. Although the conventional practice of concatenating features (“+”) is straightforward, it does not necessarily guarantee strong discriminative performance and may diminish the relative significance of individual base sequences. To address these challenges, we use Feature Weight Optimization along with Differential Evolution (DE)72. This method is great for conducting a global search, achieving fast convergence, and tackling complex, non-linear optimization issues. In this study, we utilize three distinct feature-encoded representations for peptide sequences: GloVe, FastText, and One-Hot Encoded vectors. Each sample is represented by a feature vector from the three encodings. The final dataset combines the three metrics: \(D_{\text {GloVe}} \in \mathbb {R}^{n \times m_1}\), \(D_{\text {FastText}} \in \mathbb {R}^{n \times m_2}\) and \(D_{\text {OneHotEncode}} \in \mathbb {R}^{n \times m_3}\). The combined dataset is:

Where,

Then the features were normalized using Min-Max scaling, which ensures equal contribution of all features during optimization:

To enhance classification accuracy, we applied the DE algorithm, a population-based, derivative-free optimization method suited for continuous feature spaces. The steps are as follows:

-

1.

Initialization In this step, DE initializes feature weights using a population size (NP) of 70. Each individual is a weight vector \(w_i = [\omega _1, \omega _2, \dots , \omega _m]\) with values between 0 and 1, representing the importance of each feature. The algorithm uses a mutation factor (F) of 0.5, a crossover rate (CR) of 0.7, and runs for 100 generations.

-

2.

Fitness Evaluation Each individual vector wi in the DE population contains one weight per feature dimension. When these weights are applied to the feature vectors in dataset \(X\), they create \(X\omega\) through element-wise multiplication, as described in Equation 11. This enables selective amplification or attenuation of individual features based on their relevance to the prediction task.

$$\begin{aligned} X_w = X \, o \, w_i \end{aligned}$$(11)Where, o is element-wise multiplication. The weighted dataset is then trained with a Logistic Regression73 model.

$$\begin{aligned} f(x) = \sigma (w^T x + b) \end{aligned}$$(12)$$\begin{aligned} \sigma (z) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-z}} \end{aligned}$$(13) -

3.

DE Operations (i) Mutation: Create a mutant vector using three distinct individuals

$$\begin{aligned} v_i = w_{i_1} + F \cdot (w_{r_2} - w_{r_3}) \end{aligned}$$(14)(ii) Crossover: Create a trial vector \(u_i\) from mutant \(v_i\) and target \(w_i\)

$$\begin{aligned} u_{i,j} = {\left\{ \begin{array}{ll} v_{i,j}, & \text {if } \text {rand}_j \le CR \text { or } j = j_{\text {rand}} \\ w_{i,j}, & \text {otherwise} \end{array}\right. } \end{aligned}$$(15)(iii) Selection:

$$\begin{aligned} w_j^{\text {new}} = {\left\{ \begin{array}{ll} u_i, & \text {if } f(u_i) > f(w_i) \\ w_i, & \text {otherwise} \end{array}\right. } \end{aligned}$$(16) -

4.

Termination: After going through 100 generations, the Differential Evolution (DE) algorithm discovers the weight vector \(w^*\) that provides the best classification accuracy when tested against the validation subset. This vector effectively represents how important each feature is in the model’s predictions. Detailed information is in the supplementary file Fig. 10.

Once the optimal vector \(w^*\) is obtained, it’s applied to the fused feature matrix to create the final weighted input \(Xw^*\). This representation is used in training the AttBiLSTM model, enhancing discriminability and reducing redundancy.

After finishing the DE procedure, the final results are produced. Here, we developed a new composite feature, expressed as H7(One-hot encoding+ GloVe + fastText), which is derived by combining the One-hot encoding, GloVe, and fastText features using weighted sequential fusion.

Weights optimization of AttBiLSTM using differenetial evolution

The Differential Evolution (DE) optimization process was modified to directly optimize the weights of the proposed Attention-based Bidirectional LSTM (AttBiLSTM) model. In this approach, DE utilizes the validation accuracy of the AttBiLSTM as its fitness function, ensuring that the optimization aligns with the final prediction architecture. To start, the trained AttBiLSTM model’s weights were flattened and encoded as continuous vectors. A DE population was then initialized with random perturbations around the base model weights. Candidate solutions were evolved over 100 generations using standard DE mutation and crossover strategies. During the fitness evaluation, each candidate solution was projected into the model, and a forward pass was conducted on the validation set to compute its accuracy. The candidate with the highest validation accuracy was selected to update the model parameters. Finally, the optimized weights obtained through DE were further fine-tuned using backpropagation for an additional 100 training epochs.

Proposed model architecture

We present a novel deep learning architecture that integrates a BiLSTM network with an enhanced attention mechanism, aiming to improve the extraction of insights from anticancer peptides. The fundamental goal of this architecture is to generate dense, sequence-aware embeddings that prioritize biologically relevant regions of peptide sequences. The model is composed of an input embedding layer, followed by a BiLSTM layer that captures temporal dependencies. An attention mechanism is then used to focus on relevant parts of the peptide sequences, ending in a classification layer that interprets the learned representations for subsequent tasks. The architecture of the planned AttBiLSTM_DE network is described in detail.

The BiLSTM framework

BiLSTM74 captures important information by considering context from both directions. Many sequence-based problems can be enhanced by recognizing the context surrounding a particular token. BiLSTM networks address this by integrating two LSTM networks: one that processes the sequence in a forward direction, reads the sequence from \(t = \tau _0\) to \(t = \tau _1\) (equ 17) and another that processes it in a backward direction, reads the sequence from \(t = \tau _1\) to \(t = \tau _0\) (equ 18 ). This approach allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the data. At each timestep, the outputs of the forward and backward LSTM units are combined (equ 19) to capture bidirectional dependencies. This way, the model can understand both what happened before (on the left) and what will happen next (on the right) for each part of the sequence75. The mechanism, in a nutshell, is as follows-

The BiLSTM network undergoes a forward pass to calculate activations and store states, followed by a backward pass using BPTT for gradient computation. Weights are updated to minimize the loss function, allowing the model to learn more comprehensive features from peptide or protein sequences. The overall workflow of this process is as follows-

A. Forward Pass:

-

1.

Resets all activations to zero prior to inputting data.

-

2.

Iterate from time \(\tau _0\) to \(\tau _1\) : (i) Feed each input \(x_t\) into both the forward and backward LSTM cells. (ii) Update the input gate, forget gate, cell state, and output gate by using the standard LSTM equations:

$$\begin{aligned} i_t = \sigma (W_i x_t + U_i h_{t-1} + b_i) \end{aligned}$$(20)$$\begin{aligned} f_t = \sigma (W_f x_t + U_f h_{t-1} + b_f) \end{aligned}$$(21)$$\begin{aligned} o_t = \sigma (W_o x_t + U_o h_{t-1} + b_o) \end{aligned}$$(22)$$\begin{aligned} \tilde{c}_t = \tanh (W_c x_t + U_c h_{t-1} + b_c) \end{aligned}$$(23)$$\begin{aligned} c_t = f_t \odot c_{t-1} + i_t \odot \tilde{c}_t \end{aligned}$$(24)$$\begin{aligned} h_t = o_t \odot \tanh (c_t) \end{aligned}$$(25)Where, \(i_t\) is the input gate, \(f_t\) is the Forget Gate, \(o_t\) is the Output Gate, \(\tilde{c}_t\) is the Cell Candidate, \(c_t\) is the Cell-State update, and \(h_t\) is the Hidden State.

-

3.

Store all hidden states \(h_t\) and output predictions at each timestep

B. Backward Pass (BPTT - Backpropagation Through Time):

-

1.

Reset all partial derivatives to zero.

-

2.

Starting at time \(\tau _1\), calculate the discrepancy between forecasted and actual labels using cross-entropy loss.

$$\begin{aligned} L = - \sum _{t} y_t \log (\hat{y}_t) \end{aligned}$$(26)Where \(y_t\) is the true label, and \(\hat{y}_t\) is the softmax output.

-

3.

Backpropagate the error through the unfolded network using BPTT, calculating gradients for each gate and parameter.

C. Weight Update:

After the gradients for the whole sequence have been gathered using gradient descent or an optimizer to update all weight metrics:

where \(\theta\) are the model parameters, and \(\eta\) is the learning rate (Fig. 3).

Attention mechanism

Traditional BiLSTM models can lose important information in longer sequences76,77,78. Attention mechanisms improve BiLSTM by enabling targeted focus, enhancing interpretability, and alleviating memory demands, which aids the model in honing in on pertinent sections while making predictions79. Integrating the attention mechanism with a BiLSTM model improves detection by dynamically weighting the importance of sequence elements. The BiLSTM captures contextual relationships from both preceding and succeeding positions, while the attention mechanism improves comprehension by emphasizing key biological factors, enhancing the model’s accuracy in recognizing anticancer peptides. The Scaled Dot-Product Attention80 employed in our model can be explained as follows: For a given query Q, key K, and value V, the attention mechanism calculates a weighted sum of the values, with the weights being influenced by the similarity between the query and the keys.

Where, \(Q = K = V = X\). Since we utilize self-attention within our model, all components originate from the identical input \(X \in \mathbb {R}^{T \times d}\), \(d_k\): dimensionality of the key vectors, and T: sequence length. Figure 4 illustrates the attention mechanism concept more clearly.

Architecture of AttBiLSTM_DE

Our architecture integrates BiLSTM networks with self-attention mechanisms. The model includes three stacked BiLSTM layers, where self-attention is applied only after the first two BiLSTM layers to improve feature discriminability and contextual understanding. The architecture begins with an InputLayer of shape (None, 1, 16454), representing the hybrid feature vector extracted from the peptide sequences. After DE-based dimensionality selection, the number of features(16,966) was optimized down to 16,454 then fed into a high-capacity BiLSTM layer containing 512 units, which outputs a tensor of shape (None, 1, 512) and encompasses 34,224,128 trainable parameters. A Dropout layer with a rate of 0.3 mitigates overfitting without changing the output shape, followed by a Batch Normalization layer with 2,048 parameters to stabilize learning and enhance generalization. An Attention mechanism is then applied, producing an output of 512 features at 1 time step with no trainable parameters. The outputs of the batch-normalized BiLSTM and attention mechanism are concatenated, resulting in a tensor with 1024 features at 1 time step. The concatenated tensor is passed through a second BiLSTM layer with 256 units, producing an output of shape (None, 1, 256) and containing 1,180,672 parameters. This layer is followed by a Dropout layer (rate 0.3), Batch Normalization (1,024 parameters), and an Attention mechanism with no trainable parameters. The batch-normalized BiLSTM output and attention output are concatenated to produce a tensor with 512 features. The third BiLSTM layer reduces dimensionality to 128 features (None, 128) with 295,424 parameters, followed by a Dropout layer (0.3) and Batch Normalization (512 parameters). The output is then passed through a series of Dense layers: the first Dense layer reduces it to 64 features with 8,256 parameters and a subsequent Dropout layer (0.3), followed by a Dense layer producing 32 features with 2,080 parameters, and Batch Normalization (128 parameters). Finally, a Dense output layer generates a single prediction with 33 parameters. The architecture contains a total of 36,777,473 parameters, of which 36,775,553 are trainable and 1,920 are non-trainable. The model is compiled using the Adam optimizer81 and employs binary cross-entropy82 as the loss function. Accuracy is used as the main evaluation metric. ELU (Exponential Linear Unit)83 activation is applied in the fully connected layers for smoother and faster convergence, and Dropout is consistently applied after each BiLSTM and Dense layer to prevent overfitting. Training was performed using TensorFlow84 on Google Colab(free version). Despite the high parameter count, the model was trained using a batch size of 16 over 100 epochs, with each epoch completing in approximately 140 seconds. These results demonstrate the practicality and accessibility of our approach for researchers with limited computational resources. To reduce the risk of overfitting caused by high model complexity and a large number of parameters, we implemented several regularization strategies. These include dropout layers with rates of 0.3 after the final BiLSTM module and 0.4 after the first dense layer. Additionally, we applied L2 weight regularization with a coefficient of 0.01 in the first dense layer. The dropout and L2 regularization settings were chosen to ensure convergence without overfitting. The values were confirmed by observing the loss and accuracy curves for the training and validation sets, showcasing consistent convergence and efficient complexity control. Early stopping was not necessary.

Detailed model configuration, training, preprocessing, and architecture tables are provided in Fig. 13, Tables 01 and 02 in the supplementary file.

Rationale for model complexity

The proposed AttBiLSTM_DE model reflects a careful approach to understanding the intricate relationships in peptide sequences. Its architectural complexity arises from the need to effectively capture both the sequential patterns and the contextual dependencies that are key to analyzing these biological structures. The model takes in a high-dimensional input space with 16,454 features, which integrates various representation methods like One-Hot, GloVe, and fastText. Each of these methods highlights different characteristics of peptide structures and their physicochemical properties. To manage this complexity and avoid issues like overfitting, we utilize a feature weighting strategy based on Differential Evolution (DE). This process helps to evaluate and assign importance to each feature, while also downplaying less useful or redundant information. The AttBiLSTM framework itself combines the strengths of bidirectional modeling with a detailed attention mechanism, allowing it to effectively learn the nuanced relationships between sequence patterns and their potential anticancer activities. While the model is ambitious, with over 36 million trainable parameters, we’ve implemented strict measures like dropout, batch normalization, and L2 regularization to ensure stable learning, even when working with a smaller dataset. This careful balance of complexity and power enables the model to perform effectively without falling into the trap of overfitting, a fact confirmed by thorough cross-validation and independent testing.

Results and discussion

Evaluation metrics

Evaluation metrics serve as essential parameters for assessing a model’s performance. Relying solely on accuracy or just a few metrics can lead to an incomplete understanding of a model’s effectiveness. To provide a thorough evaluation of our proposed classification model, we utilized a diverse set of metrics: Accuracy, Precision, Recall (Sensitivity), Specificity, F1-score, AUC, and MCC. By incorporating these various metrics, we can achieve a more balanced and comprehensive view of the model’s performance. The detailed description of the metrics is given as follows:

AUC measures a model’s ability to distinguish between classes. It indicates how effectively it ranks positive instances higher than negative ones for accurate classifications. True Positives (TP) are instances where the model correctly identifies the positive class, while True Negatives (TN) are instances where the model accurately predicts the negative class. On the other hand, False Positives (FP) occur when the model mistakenly predicts a positive outcome despite the actual result being negative, and False Negatives (FN) arise when the model incorrectly identifies a negative outcome when the true result is positive.

k-mer Embedding encodes more accurate motifs information

In order to identify the optimal k-mer length for our AttBiLSTM_DE model, we conducted a series of experiments examining k values from 1 to 6. This exploration involved four widely recognized feature encoding techniques: One-Hot Encoding, Word2Vec, GloVe, and fastText. For each unique combination of encoding method and k-mer length, we thoroughly assessed the model’s performance on the original dataset. We utilized a range of performance metrics to ensure a comprehensive evaluation. This method helped us grasp how various configurations impacted the model’s effectiveness.

The findings presented in Table 1 demonstrate that the One-Hot Encoding approach with a k-mer length of 3 yields the best performance metrics compared to all other encoding methods assessed. Specifically, it achieves an AUC score of 87.66%, indicating a strong ability to distinguish between different classes. Additionally, this method reports an accuracy rate of 83.29%, a MCC of 66.66%, and an F1-score of 81.85%. These metrics collectively underscore the robustness of One-Hot Encoding with 3-mers in effectively capturing the discriminative patterns inherent in the motif data.

On the other hand, when the length of the k-mers exceeds 3, there is a significant reduction in performance for all encoding strategies considered in this research. The decline indicates that longer k-mers, though capable of representing complex patterns, may add excessive noise and lead to data sparsity. This can hinder the learning process and affect the model’s predictive accuracy. It emphasizes the need to optimize k-mer lengths to balance complexity and clarity in motif detection.

Among the different techniques for creating word embeddings, GloVe and Word2Vec using 3-mer (three-letter groups) perform reasonably well. For example, GloVe with 3-mer has an AUC score of 84.47% and an F1-score of 77.56%. Word2Vec with 3-mer does even better, with an AUC of 87.17% and an F1-score of 79.17%. However, they are still not as good as the One-Hot technique in important measurements like MCC and accuracy.

On the other hand, the 4-mer to 6-mer embeddings generally do not perform as well, especially with fastText and GloVe. FastText does well with the 3-mer, achieving an F1-score of 78.28%. However, when using longer groups of letters (like 6-mers), its performance drops sharply, with the F1-score falling to 44.68%. This suggests that fastText’s method of using smaller letter groups does not work as effectively for longer patterns in biological sequences. The table 04 in the supplementary file shows the best performance kmers.

The ROC curves for our AttBiLSTM_DE models, which use different k-mer lengths ranging from 1-mer to 6-mer, are illustrated in Fig. 5. The models utilize four distinct feature extraction methods: One-Hot encoding, Word2Vec, GloVe, and fastText. In each subfigure (Fig. 5A–D), we present the comparative ROC curves for these different embedding techniques, allowing for a clearer evaluation of their performance.

In a striking display of performance, the Word2Vec-based models (Fig. 5B) reached their peak at the 3-mer configuration, boasting an impressive AUC of 87.17%. However, as we ventured into 4-mers and longer sequences, there was a significant decline in effectiveness. This clearly underscores just how crucial the choice of k-mer length is for the success of this method. Likewise, the GloVe and fastText models (Fig. 5C,D) displayed moderate AUC values with shorter k-mers (1–3), whereas the use of longer k-mers (4–6) led to a decline in classification performance, indicating that excessive fragmentation of sequences obscures significant patterns.

Fig. 6E–H present bar plots that showcase the distribution of evaluation metrics for each feature extractor across six different k-mer configurations. The One-Hot encoding method (Figs. 5A, 6E) consistently exceeded the performance of others, reaching a peak at 3-mer with an AUC of 87.66%, an F1-score of 81.85%, and an MCC of 66.66%. The Word2Vec method (Figs. 5B, 6F) reached its highest F1-score at 3-mer (79.17%) and displayed the greatest sensitivity at 1-mer (91.76%), although it showed lower specificity. Models based on GloVe (Figs. 5C, 6G) provided similar performance at lower k-mer values but shows performance drop sharply beyond 3-mer, with an AUC of only 59.21% at 4-mer. In contrast, fastText (Figs. 5D, 6H) produced reasonable outcomes at 3-mer (F1-score = 78.28%), but its performance significantly declined at larger k values, with both MCC and F1-score falling below 20% at 6-mer. These bar plots clearly illustrate the dominance of the 3-mer configuration across all embedding techniques, with One-Hot encoding emerging as the most reliable and consistently high-performing method for ACP classification using AttBiLSTM_DE. The visual results in Figs. 6 and 5 show that using 3-mer encoding leads to the best performance across all the different embedding strategies. Additionally, it appears that One-Hot encoding outperforms as the most reliable and effective way to represent data for ACP classification when using AttBiLSTM_DE.

Effects of different feature combinations

In this section of our study, we methodically evaluated the influence of various combinations of feature encoding techniques on the performance of the proposed AttBiLSTM_DE model for ACP identification. Our findings demonstrate a clear relationship between these encoding methods and the model’s effectiveness. We assessed various single-feature encoding methods, such as One-Hot, Word2Vec, GloVe, and fastText, as well as hybrid feature encodings that combine these techniques (for instance, One-Hot + Word2Vec, One-Hot + GloVe, etc.) to enhance the representation of peptide sequences.

Table 2 (and table 03 in supplementary file) compares the performance of various encoding methods. One-Hot Encoding achieves the best AUC (87.66%) and F1-score (81.85%). Word2Vec provides a strong F1-score of 79.17%. GloVe offers good precision at 85.21% and specificity at 88.52%, but it has lower sensitivity at 71.18%. On the other hand, fastText demonstrates high sensitivity at 85.88%, albeit with lower specificity at 68.85% and an AUC of 85.36%. We also explored two state-of-the-art pre-trained protein language models, ESM and ProtT5, along with the traditional feature extractors. These models rely on transformer-based architectures and have been trained on extensive datasets of protein sequences. This makes them particularly effective for sequences-based task, like anticancer peptide prediction. Both ESM and ProtT5 showed moderate performance compared to classic feature extractors.While ProtT5 slightly outperformed ESM in terms of MCC and F1-score. However, neither of them outperformed GloVe or One-Hot encoding. To boost the performance of our model, we decided to experiment with hybrid feature sets by mixing various encoding methods. This approach led to significant improvements. To identify the most informative and complementary combinations, we employed DE as an optimization strategy to create weighted feature sets. This method enabled us to assign optimal weights to each feature representation in the hybrid set, effectively balancing their contributions and minimizing redundancy. As a result, the DE-guided combinations significantly enhanced the model’s discriminative power, leading to improved performance in ACP prediction. This optimization process not only helped identify the most informative feature combinations but also enhanced the model’s discriminative ability by reducing feature redundancy and noise, ultimately resulting in better ACP prediction performance.

The combination we identified as H7, which includes One-Hot encoding, GloVe, and fastText, turned out to be the standout performer. It achieved impressive results across nearly all metrics, with an AUC of 94.74%, an accuracy of 86.86%, an MCC of 74.25%, and an F1-score of 86.58%. H6, which combined One-Hot encoding with GloVe and Word2Vec, scored 84.79%, while H5, using One-Hot with fastText, scored 83.33%. These results underscore the benefits of integrating multiple semantic features.

The findings are visually depicted in Fig. 7, which features a bar chart (Fig. 7A) for metric-based comparisons and a heatmap (Fig. 7B) illustrating the performance distribution across various feature encoders. The bar chart emphasizes the significant difference in performance between single encoders and hybrid encoders, while the heatmap facilitates a quick evaluation of which combinations excelled across particular metrics. Therefore, after carefully analyzing the performance of all feature extraction strategies, we found that while some excelled in specific areas, they lacked overall balance. In contrast, H7 (One-Hot + GloVe + fastText) consistently produced reliable results across all metrics. Hence, we selected H7 as the final approach for our AttBiLSTM_DE model to ensure robust performance. More visualization results can be found at Figs. 03-09 in the supplementary file.

Effects of selected feature on independent dataset

After successfully assessing the training dataset of the four feature extractors, pre-trained protein language models(ESM and ProtT5), and the combinations, we finally select the hybrid feature extractor (One-Hot + GloVe + fastText) as our final dataset. Therefore, we applied our AttBiLSTM_DE model to an independent dataset using only the single 4-feature extractor, 3-mer, since it consistently yielded better results compared to most other extractors as well as the hybrid dataset we considered.

The following table 3 illustrates the results for the independent set. From the table, we see the effectiveness of various feature encoding methods—specifically One-Hot Encoding, Word2Vec, GloVe, fastText,

and a combined approach (One-Hot + GloVe + fastText)—utilizing our proposed AttBiLSTM_DE model. Notably, GloVe emerged as the standout method among the individual encodings, achieving the highest results across all metrics, particularly excelling in MCC (77.85%), Sensitivity (85.71%), and F1-score (83.02%). Furthermore, One-Hot Encoding demonstrated strong performance, particularly in Specificity (96.54%) and Accuracy (91.69%). Word2Vec and fastText demonstrated commendable Precision scores, achieving 100.00% and 95.45%, respectively. However, both the extractor exhibited lower Sensitivity levels, at 54.55%, which signifies a higher efficacy in identifying true negatives rather than true positives. Besides, both ESM and ProtT5 showed good performance, achieving AUC values over 93%. However, they still lagged behind traditional methods, such as GloVe and the hybrid approach. More importantly, both models had lower Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) and F1-scores.

The combined encoding method (One-Hot + GloVe + fastText) proved to be the most effective overall, surpassing all individual techniques with exceptional metrics—AUC of 98.48%(see in the Fig. 8 the ROC curve), Accuracy of 95.85%, MCC of 88.00%, and F1-score of 90.54%. This finding highlights the significant performance enhancements achievable through the integration of complementary features, suggesting that collaborative approaches can lead to improved outcomes in model performance. H7 achieves a high specificity of 98.46% on the independent test set. High specificity indicates that the model effectively avoids false positives, which is biologically significant in ACP prediction: non-anticancer peptides are accurately identified, minimizing the risk of incorrectly classifying a non-ACP as an ACP. This level of precision is particularly important for downstream experimental validation, where false positives could lead to unnecessary laboratory testing.

Line plots and bar plots for the comparison of the existing attention-based deep learning architectures. AttBiLSTM_DE(Attention-based BiLSTM with Optimized Weighted Feature) is the Proposed Model. (A) Line Plot For Training Dataset, (B) Line Plot For Independent Dataset, (C) Bar Plot For Training Dataset, and (D) Bar Plot For Independent Dataset.

Reproducibility and robustness analysis using K-fold cross-validation

We conducted a reproducibility experiment using three different random seeds and five-fold cross-validation to test our ACP prediction model. The results were encouraging, showing that the model consistently performs well, no matter how we partition the data or initialize the conditions. In fact, as highlighted in Table 4, we found that the model achieved an impressive average accuracy of 94.07% with a small variation of just ± 0.40. Additionally, it recorded an AUC of 96.69% and an F1-score of 82.68%, both with low standard deviations across different runs. These results suggest that the model is quite robust—it doesn’t seem to be affected by random changes or variations in the folds, which adds to its reliability. In contrast, When the model was trained and evaluated using just one random split instead of cross-validation, it really showed its potential. It achieved an impressive accuracy of 98.48%, an AUC of 95.85%, precision of 88.00%, recall of 87.01%, specificity of 98.46%, an F1-score of 94.37%, and an MCC of 90.54%. These results highlight how well the model can discriminate between different classes in this single evaluation. However, while these impressive numbers reflect its strong performance, the cross-validation results are also important as they demonstrate the model’s reliability and ability to generalize across various random setups. Therefore, the consistent performance we observed across different test setups shows that our model is both reliable and strong. It effectively tells apart anticancer peptides from non-anticancer sequences, even when faced with a variety of experimental conditions.

Comparison of existing attention-based models

In this section, we compare our proposed architecture with several existing attention-based models, such as AttXGBoost, AttDenseFusion, AttGRU, and AttMLP. Table 5 shows the performance of six different models—AttXGBoost, AttDenseFusion, AttGRU, AttMLP, AttBiLSTM, and AttBiLSTM_DE—on both the training dataset and an independent test dataset. Here, AttBiLSTM_DE refers to the attention-based model that uses Differential Evolution for concatenating the hybrid feature extractor.

In our evaluation, the AttBiLSTM_DE model demonstrated exceptional performance, attaining the highest scores across nearly all categories. It reached impressive numbers with an AUC of 94.74%, Accuracy of 86.86%, MCC of 74.25%, and an F1-score of 86.58%. The regular AttBiLSTM also performed admirably and closely followed behind. In contrast, models like AttXGBoost and AttMLP displayed lower sensitivity and MCC, indicating they struggled more to accurately identify positive cases. However, the overall results were very promising. In the evaluation using an independent dataset, which assesses the model’s effectiveness on novel data, AttBiLSTM_DE demonstrated the most favourable performance. The model achieved an AUC of 98.48%, an accuracy of 95.85%, and an F1-score of 90.54%, demonstrating its reliability and strong generalization capabilities. Other models, notably AttMLP and AttDenseFusion, also exhibited commendable performance; however, they did not reach the performance levels established by AttBiLSTM_DE. We visualized the models to better compare their behaviour on both training and independent datasets. The confusion matrix and the per class evolution metrics of our proposed AttBiLSTM_DE model for both train and independent dataset are visualized at Fig. 11 in the supplementary file.

ROC Curves Ploting the True Positive Rate (TPR) against the False Positive Rate (FPR) for the Comparison of the Existing Attention-Based Deep Learning Architectures. AttBiLSTM_DE(Attention-based BiLSTM with Optimized Weighted Feature) is the Proposed Model. (A) ROC Curve For Training Dataset, (B) ROC Curve For Independent Dataset.

The ROC curve in Fig. 11 shows how well each model differentiates between positive and negative classes. The AttBiLSTM_DE curve is closest to the top-left corner, indicating it has the highest true positive rate and lowest false positive rate, confirming its superior performance. Figure 10C,D displays a bar plot of key performance metrics, such as accuracy and F1-score, for all models. This clearly shows that AttBiLSTM_DE consistently outperforms the others across most metrics on both datasets. The line plot (Fig. 10A,B) shows that the AttBiLSTM_DE model outperforms the others in terms of metrics like the MCC and F1-score. This suggests it’s well-balanced in terms of both precision and recall. When looking at the ROC curve for the training dataset, it’s clear that AttBiLSTM_DE effectively learns data patterns, achieving a high AUC score. The ROC curve for the independent dataset further demonstrates that the model can generalize effectively to new data. The heatmap (in Fig. 9A) for the training dataset visualizes strong classification metrics for AttBiLSTM_DE, while the heatmap (Fig. 9B) for the independent dataset reaffirms its impressive performance on unseen data, particularly in areas like F1, Precision, and MCC. Overall, our summary visualization highlights AttBiLSTM_DE as the standout model among its peers.

To enhance the visualization of how different models perform, we employed an average ranking method (Fig. 12) across various evaluation metrics, such as AUC, Accuracy, MCC, Sensitivity, Specificity, Precision, and F1-Score. Each model received an individual rank for every metric, and our model ranked the highest for its best performance. We then computed the average of these ranks for each model across all metrics. A lower average rank indicates superior overall performance. This approach offers a well-rounded comparison by taking into account all aspects of performance and is widely utilized in machine learning literature85. We also evaluate the performance of our proposed approach by making predictions on different sequences, those results are visualized in the Fig. 12 and Tables 5, 6 in the supplementary file.

Using attention in a BiLSTM architecture offers significant advantages for predicting amino acid properties compared to other models like GRU, AttDenseFusion, XGBoost, or MLP86. The BiLSTM can capture relationships in the data from both directions, which lets the model understand how amino acids upstream and downstream affect the function of peptides—something traditional models like GRU or MLP can’t really do87. What sets the attention mechanism in BiLSTM apart is its ability to focus on important positions in the sequence while learning from the contextual information dynamically. This means the model not only becomes more accurate but also more interpretable, which is essential in biological contexts. Moreover, BiLSTM combined with attention is great at handling different types of features, whether they’re encoded in One-Hot, GloVe, or fastText formats87. This versatility allows it to capture complex relationships within sequences effectively, making it a stronger choice for peptide classification tasks compared to other attention-based models.

Comparison of our proposed model with existing works

We conducted a thorough evaluation of AttBiLSTM_DE along with other publicly available predictors for ACP using a separate dataset. The predictors we examined include mACPpred2.045, mACPpred44, MLACP2.043, ACPred-BMF(Main), ACPred-BMF(Alternate)88, ACPred31, AMPfun89, AntiCP2.0(Main)41, AntiCP2.0 (Alternate), CancerGram90, and iDACP91 shows that, our proposed model, AttBiLSTM_DE, demonstrably surpasses all existing methods across a comprehensive range of metrics, achieving the highest performance figures in global metrics, including an accuracy (ACC) of 95.85%, a Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC) of 88.00%, an area under the curve (AUC) of 98.48%, and an F1-score of 90.54%. These results indicate a superior overall predictiv capability when compared to alternative models for predicting ACP. The nearest competitors, mACPpred2.0 and MLACP2.0, report ACCs of 85.70% and 83.80%, MCCs of 59.70% and 55.70%, and AUCs of 88.70% and 89.30%, respectively. However, they remain significantly inferior in terms of F1-score and overall accuracy. This substantial performance enhancement underscores the robustness and reliability of our proposed approach (Table 6).

Ablation study on training set and independent set

Ablation study is a technique used to determine how different components of a model affect its performance by systematically removing or altering parts and observing the changes. Ablation studies are essential for assessing the effectiveness of different model components. They identify impactful elements, reduce unnecessary complexity, and provide a scientific basis for model design by analyzing each part’s contribution.

In our research, we performed an ablation study on the training dataset to assess the impact of various elements of the AttBiLSTM_DE model. In particular, we evaluated the model by omitting specific combinations of features or architectural components to see how the performance varied. Table 7 demonstrates how changes to components like feature fusion layers or attention modules influence the model’s performance. The baseline model (A0) really outshines the others when we look at various metrics such as AUC, accuracy, sensitivity, and F1-score.It is noteworthy that when we started removing key components like attention mechanisms, LSTM layers, or bidirectionality in models A1 through A8, the performance declined significantly. This observation clearly shows the critical role of each component of the model for achieving high accuracy and overall effectiveness. It’s a great reminder of how every element in our approach contributes to success.

To enhance our understanding of the ablation results, we incorporated a Heatmap (Fig. 13). This visualization uses colour coding to depict performance across various ablation settings, with darker shades representing better performance. This allows for a straightforward comparison of each configuration. Additionally, we included a box plot (Fig. 14) to illustrate the distribution of performance metrics such as Accuracy and F1 across different ablation setups. This plot further reinforces the consistent stability and superior performance of the complete AttBiLSTM_DE model compared to its ablated versions. We also conducted an ablation study on the independent dataset to assess how model changes impact generalizability. The baseline model (A0) consistently achieved the highest performance, confirming its robust design. Removing key components reduces the model’s performance, indicating their importance for accurate classification. So, overall, our model gives very efficient and robust performance for classifying ACPs and non-ACPs.

Case study

Anticancer peptides (ACPs) are effective therapeutic agents with high selectivity and low toxicity towards cancer cells. Identifying ACPs from protein sequences is crucial for drug discovery but is often costly and time-consuming. This study aims to predict ACPs using integrated deep learning and feature embedding methods.

Our approach to predicting ACPs has some notable improvements compared to previous leading models. For instance, the recent mACPpred 2.044 made strides using a stacked deep learning framework and various descriptors, including NLP-based embeddings to enhance its predictive capabilities. Meanwhile, ACPred-BMF88 utilized Bi-LSTM architectures combined with interpretable features like BPF, Quanc, and Qualc, along with SHAP for analyzing feature importance. Our model apart in the sence of how we blend modern embedding techniques, like fastText and GloVe, with one-hot encoding to create a hybrid representation. The study explored various sequence-based embeddings such as fastText, GloVe, Word2Vec, One-Hot, Prot5, and ESM, ultimately identifying fastText, GloVe, and One-Hot as the best hybrid features. These features were used to train an Attention-BiLSTM (AttBiLSTM) model, optimized with Differential Evolution for hyperparameters. The model’s robustness was evaluated through 5-fold cross-validation across three random seeds, with performance metrics reported as mean ± standard deviation. On an independent test set, the AttBiLSTM_DE demonstrated high accuracy, AUC, and MCC, effectively discriminating between ACPs and non-ACPs.

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed Logistic Regression guided DE strategy, we conducted a comparative analysis against an alternative DE approach guided directly by the AttBiLSTM model. As shown in Table 5, both methods achieved comparable and high AUC values, 98.48% for LR-guided and 98.39% for AttBiLSTM guided, demonstrating strong classification performance. While the AttBiLSTM guided version achieved a slightly higher accuracy, 96.44%, the LR-guided DE strategy showed higher precision 94.37% and F1-score 90.54%, suggesting better reliability in correctly identifying positive samples which is an important aspect in biological sequence prediction where false positives are particularly costly. This advantage is attributed to Logistic Regression’s sensitivity to linear feature boundaries, enabling it to act as a robust surrogate in guiding feature weight optimization during DE. Overall, the comparison confirms that while both strategies are effective, the LR-guided DE retains a practical edge in key performance metrics, supporting its use as the preferred optimization approach in our framework.

In the Fig. 15, the PR-AUC (0.9619) 15A and ROC-AUC (0.9804) 15B scores on the independent test set indicate that the model exhibits strong discriminatory power and a low false-positive bias despite significant class imbalance. Additionally, the decision curve analysis 15C reveals that the model consistently provides a greater net benefit compared to the “treat-all” or “treat-none” approaches across clinically important probability thresholds, highlighting not just statistical reliability but also practical decision-making value in identifying ACP.

For biological interpretation, we analyzed several top sequences predicted by our model from Supplementary File Table 6. These sequences were selected based on their highest predicted probability scores for ACP activity. For instance, the peptide DSHAKRHHGYKRKFHEKHHSHRGYRSNYLYDN has a prediction score of 0.9986 for ACP activity, indicating a high-confidence classification. The attention layers identify the most informative features from One-hot, GloVe, and fastText embeddings, demonstrating that the model focuses on biologically relevant sequence properties, such as k-mer patterns and amino acid composition. In contrast, the peptide RGIRGSSAARPSGRRRDPAGRTTETGFNIFTQHD has a prediction score of 0.0072, indicating that it is likely not an ACP, with only a 0.72% chance of being one. To further evaluate the real-world applicability and biological relevance of the proposed model, we conducted a case study using experimentally validated ACPs and ACP small molecule conjugates. Specifically, we assessed the model’s predictive performance on LTX-315, a synthetic cationic peptide with well documented anticancer and immunomodulatory activity in preclinical studies and ongoing clinical trials. The peptide sequence KKWWKWWKW-FKRKR was encoded using the selected hybrid feature representation (FastText + GloVe + One-hot) and evaluated using the proposed AttBiLSTM_DE model. The model successfully assigned a high prediction score (97.98%)to this peptide, in alignment with its known anticancer potential. Furthermore, although NTP-38592 and FXY-393 are peptide–small molecule conjugates rather than standalone peptide sequences, they are based on LTX-315 and share similar biological mechanisms. Their inclusion underscores the model’s potential utility in predicting anticancer activity not only in pure peptides but also in hybrid peptide-based therapeutics.

Data availability

The datasets for this research can be directly accessed from our web application site at: https://att-bi-lstm-de-acp.vercel.app/dataset.

References

Lin, H.-Y. & Park, J. Y. Epidemiology of cancer. in Anesthesia for Oncological Surgery 11–16 (Springer, 2024).

Luigjes-Huizer, Y. L. et al. What is the prevalence of fear of cancer recurrence in cancer survivors and patients? A systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Psychooncology 31(6), 879–892 (2022).

Chhikara, B. S. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: The trends projection analysis. Chem. Biol. Lett. 10(1), 451–451 (2023).

Bizuayehu, H. M. et al. Global disparities of cancer and its projected burden in 2050. JAMA Netw. Open 7(11), e2443198–e2443198 (2024).

Ott, J. J., Ullrich, A. & Miller, A. B. The importance of early symptom recognition in the context of early detection and cancer survival. Eur. J. Cancer 45(16), 2743–2748 (2009).

Crosby, D. et al. Early detection of cancer. Science 375(6586), eaay9040 (2022).

Brown, J. S. et al. Updating the definition of cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. 21(11), 1142–1147 (2023).

Finley, L. W. What is cancer metabolism?. Cell 186(8), 1670–1688 (2023).

Pérez-Moreno, P., Riquelme, I., García, P., Brebi, P. & Roa, J. C. Environmental and lifestyle risk factors in the carcinogenesis of gallbladder cancer. J. Pers. Med. 12(2), 234 (2022).

Leiter, A., Veluswamy, R. R. & Wisnivesky, J. P. The global burden of lung cancer: Current status and future trends. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 20(9), 624–639 (2023).

Hikisz, P. & Jacenik, D. The tobacco smoke component, acrolein, as a major culprit in lung diseases and respiratory cancers: Molecular mechanisms of acrolein cytotoxic activity. Cells 12(6), 879 (2023).

Jardim, S. R., de Souza, L. M. P. & de Souza, H. S. P. The rise of gastrointestinal cancers as a global phenomenon: Unhealthy behavior or progress?. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20(4), 3640 (2023).

Xiaogang, H. et al. The role of nutrition in harnessing the immune system: A potential approach to prevent cancer. Med. Oncol. 39(12), 245 (2022).

Azad, H. et al. G-acp: A machine learning approach to the prediction of therapeutic peptides for gastric cancer. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2014, 1–14 (2024).

Kaur, R., Bhardwaj, A. & Gupta, S. Cancer treatment therapies: Traditional to modern approaches to combat cancers. Mol. Biol. Rep. 50(11), 9663–9676 (2023).

Shewach, D. S. & Kuchta, R. D. Introduction to Cancer Chemotherapeutics (2009).

Berger, L. et al. Major complications after intraoperative radiotherapy with low-energy x-rays in early breast cancer. Strahlenther. Onkol. 200(4), 276–286 (2024).

Timmons, P. B. & Hewage, C. M. Ennavia is a novel method which employs neural networks for antiviral and anti-coronavirus activity prediction for therapeutic peptides. Brief. Bioinform. 22(6), bbab258 (2021).

Hodgson, K. D., Hutchinson, A. D., Wilson, C. J. & Nettelbeck, T. A meta-analysis of the effects of chemotherapy on cognition in patients with cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 39(3), 297–304 (2013).

Silveira, F. M. et al. Impact of chemotherapy treatment on the quality of life of patients with cancer. Acta Paulista Enfermagem 34, eaPE00583 (2021).

Sharma, A., Jasrotia, S. & Kumar, A. Effects of chemotherapy on the immune system: implications for cancer treatment and patient outcomes. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 397(5), 2551–2566 (2024).

Khan, S. U., Fatima, K., Aisha, S. & Malik, F. Unveiling the mechanisms and challenges of cancer drug resistance. Cell Commun. Signal. 22(1), 109 (2024).

Eslami, M. et al. Overcoming chemotherapy resistance in metastatic cancer: A comprehensive review. Biomedicines 12(1), 183 (2024).

Mengistu, B. A. et al. Comprehensive review of drug resistance in mammalian cancer stem cells: Implications for cancer therapy. Cancer Cell Int. 24(1), 406 (2024).

Maeda, H. & Khatami, M. Analyses of repeated failures in cancer therapy for solid tumors: Poor tumor-selective drug delivery, low therapeutic efficacy and unsustainable costs. Clin. Transl. Med. 7, 1–20 (2018).

Turánek, J., Škrabalová, M. & Knötigová, P. Antimicrobial and anticancer peptides. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 11, 128–135 (2015).

Xie, M., Liu, D. & Yang, Y. Anti-cancer peptides: Classification, mechanism of action, reconstruction and modification. Open Biol. 10(7), 200004 (2020).

Zare-Zardini, H. et al. From defense to offense: Antimicrobial peptides as promising therapeutics for cancer. Front. Oncol. 14, 1463088 (2024).

Kabir, M. et al. Intelligent computational method for discrimination of anticancer peptides by incorporating sequential and evolutionary profiles information. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 182, 158–165 (2018).

Tripathi, A. K. & Vishwanatha, J. K. Role of anti-cancer peptides as immunomodulatory agents: Potential and design strategy. Pharmaceutics 14(12), 2686 (2022).

Schaduangrat, N., Nantasenamat, C., Prachayasittikul, V. & Shoombuatong, W. Acpred: A computational tool for the prediction and analysis of anticancer peptides. Molecules 24(10), 1973 (2019).

Nhàn, N. T. T., Yamada, T. & Yamada, K. H. Peptide-based agents for cancer treatment: Current applications and future directions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(16), 12931 (2023).

Araste, F. et al. Peptide-based targeted therapeutics: Focus on cancer treatment. J. Control. Release 292, 141–162 (2018).

Hilchie, A., Hoskin, D. & Power Coombs, M. Anticancer activities of natural and synthetic peptides. Antimicrob. Peptides 1117, 131–147 (2019).

Ramazi, S., Mohammadi, N., Allahverdi, A., Khalili, E. & Abdolmaleki, P. A review on antimicrobial peptides databases and the computational tools. Database 2022, bac011 (2022).

Cao, R., Wang, M., Bin, Y. & Zheng, C. Dlff-acp: Prediction of acps based on deep learning and multi-view features fusion. PeerJ 9, e11906 (2021).

Tyagi, A. et al. Cancerppd: A database of anticancer peptides and proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 43(D1), D837–D843 (2015).

Chauhan, M., Gupta, A., Tomer, R. & Raghava, G. P. Cancerppd2: An updated repository of anticancer peptides and proteins. Database 2025, baaf030 (2025).

Tyagi, A. et al. In silico models for designing and discovering novel anticancer peptides. Sci. Rep. 3(1), 2984 (2013).

Chen, W., Ding, H., Feng, P., Lin, H. & Chou, K.-C. iacp: A sequence-based tool for identifying anticancer peptides. Oncotarget 7(13), 16895 (2016).

Agrawal, P., Bhagat, D., Mahalwal, M., Sharma, N. & Raghava, G. P. Anticp 2.0: An updated model for predicting anticancer peptides. Brief. Bioinform. 22(3), bbaa153 (2021).

Vijayakumar, S. & Ptv, L. Acpp: A web server for prediction and design of anti-cancer peptides. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 21, 99–106 (2015).

Park, H. W. et al. Mlacp 2.0: An updated machine learning tool for anticancer peptide prediction. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 20, 4473–4480 (2022).

Boopathi, V. et al. macppred: A support vector machine-based meta-predictor for identification of anticancer peptides. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20(8), 1964 (2019).

Sangaraju, V. K., Pham, N. T., Wei, L., Yu, X. & Manavalan, B. macppred 2.0: Stacked deep learning for anticancer peptide prediction with integrated spatial and probabilistic feature representations. J. Mol. Biol. 436(17), 168687 (2024).

Ahmed, S. et al. Acp-mhcnn: An accurate multi-headed deep-convolutional neural network to predict anticancer peptides. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 23676 (2021).

Chen, J., Cheong, H. H. & Siu, S. W. xdeep-acpep: Deep learning method for anticancer peptide activity prediction based on convolutional neural network and multitask learning. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 61(8), 3789–3803 (2021).

Han, B., Zhao, N., Zeng, C., Mu, Z. & Gong, X. Acpred-bmf: Bidirectional lstm with multiple feature representations for explainable anticancer peptide prediction. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 21915 (2022).

Liu, J., Li, M. & Chen, X. Antimf: A deep learning framework for predicting anticancer peptides based on multi-view feature extraction. Methods 207, 38–43 (2022).

Bhattarai, S., Kim, K.-S., Tayara, H. & Chong, K. T. Acp-ada: A boosting method with data augmentation for improved prediction of anticancer peptides. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(20), 12194 (2022).

Xu, X. et al. Acp-drl: An anticancer peptides recognition method based on deep representation learning. Front. Genet. 15, 1376486 (2024).

Arif, M., Musleh, S., Fida, H. & Alam, T. Plmacpred prediction of anticancer peptides based on protein language model and wavelet denoising transformation. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 16992 (2024).

Yue, J. et al. Discovery of anticancer peptides from natural and generated sequences using deep learning. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 290, 138880 (2025).

Yuan, Q., Chen, K., Yu, Y., Le, N. Q. K. & Chua, M. C. H. Prediction of anticancer peptides based on an ensemble model of deep learning and machine learning using ordinal positional encoding. Brief. Bioinform. 24(1), bbac630 (2023).

Liang, X. et al. Large-scale comparative review and assessment of computational methods for anti-cancer peptide identification. Brief. Bioinform. 22(4), bbaa312 (2021).

Liu, M. et al. Acppfel: Explainable deep ensemble learning for anticancer peptides prediction based on feature optimization. Front. Genet. 15, 1352504 (2024).

Deng, H. et al. Acp-mlc: A two-level prediction engine for identification of anticancer peptides and multi-label classification of their functional types. Comput. Biol. Med. 158, 106844 (2023).

Rao, B., Zhou, C., Zhang, G., Su, R. & Wei, L. Acpred-fuse: Fusing multi-view information improves the prediction of anticancer peptides. Brief. Bioinform. 21(5), 1846–1855 (2020).

Fu, L., Niu, B., Zhu, Z., Wu, S. & Li, W. Cd-hit: Accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 28(23), 3150–3152 (2012).

Kösesoy, İ, Gök, M. & Öz, C. A new sequence based encoding for prediction of host-pathogen protein interactions. Comput. Biol. Chem. 78, 170–177 (2019).

Jie, L., Jiahao, C., Xueqin, Z., Yue, Z. & Jiajun, L. One-hot encoding and convolutional neural network based anomaly detection. J. Tsinghua Univ. (Sci. Technol.) 59(7), 523–529 (2019).

Veltri, D., Kamath, U. & Shehu, A. Deep learning improves antimicrobial peptide recognition. Bioinformatics 34(16), 2740–2747 (2018).

Mikolov, T., Chen, K., Corrado, G. & Dean, J. Efficient estimation of word representations in vector space. arXiv preprint arXiv:1301.3781 (2013).

Manica, M., Mathis, R., Cadow, J. & Rodríguez Martínez, M. Context-specific interaction networks from vector representation of words. Nat. Mach. Intell. 1(4), 181–190 (2019).

Ren, R., Yin, C. & Yau, S.S.-T. kmer2vec: A novel method for comparing dna sequences by word2vec embedding. J. Comput. Biol. 29(9), 1001–1021 (2022).

Ho, Q.-T. et al. Using word embedding technique to efficiently represent protein sequences for identifying substrate specificities of transporters. Anal. Biochem. 577, 73–81 (2019).

Mikolov, T., Sutskever, I., Chen, K., Corrado, G. S. & Dean, J. Distributed representations of words and phrases and their compositionality. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 26, 1–9 (2013).

Pennington, J., Socher, R. & Manning, C. D. Glove: Global vectors for word representation. in Proceedings of the 2014 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing (EMNLP) 1532–1543 (2014).

Asgari, E. & Mofrad, M. R. Continuous distributed representation of biological sequences for deep proteomics and genomics. PLoS ONE 10(11), e0141287 (2015).

Bojanowski, P., Grave, E., Joulin, A. & Mikolov, T. Enriching word vectors with subword information. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 5, 135–146 (2017).

Zou, Q., Zeng, J., Cao, L. & Ji, R. A novel features ranking metric with application to scalable visual and bioinformatics data classification. Neurocomputing 173, 346–354 (2016).

Storn, R. & Price, K. Differential evolution-a simple and efficient heuristic for global optimization over continuous spaces. J. Global Optim. 11, 341–359 (1997).

Kleinbaum, D. G., Dietz, K., Gail, M., Klein, M. & Klein, M. Logistic Regression (Springer, 2002).

Schuster, M. & Paliwal, K. K. Bidirectional recurrent neural networks. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 45(11), 2673–2681 (1997).

Graves, A. & Schmidhuber, J. Framewise phoneme classification with bidirectional lstm and other neural network architectures. Neural Netw. 18(5–6), 602–610 (2005).

Bahdanau, D., Cho, K. & Bengio, Y. Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate, arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.0473 (2014).

Luo, L. et al. An attention-based bilstm-crf approach to document-level chemical named entity recognition. Bioinformatics 34(8), 1381–1388 (2018).