Abstract

Wearable devices are becoming a cornerstone for personalized and long-term health monitoring, enabling early intervention and data-driven medical decisions. In this work, we present e-Glass, a state-of-the-art smart wearable device that enables unobtrusive real-time electroencephalography (EEG) monitoring. Our evaluation shows that e-Glass adheres to the established international guidelines for clinical EEG recordings. Moreover, the acquired data presents a Pearson’s correlation of 0.93 relative to recordings obtained from the Biopac research-grade EEG system . The proposed EEG acquisition device concept is evaluated in two application domains: epileptic seizure detection and cognitive workload monitoring (CWM). First, we present a lightweight edge machine-learning scheme, designed specifically for e-Glass, achieving overall sensitivity of 64% (100% sensitivity in 11 out of 24 subjects) and 2.35 false-alarms per day, when tested on 982.9 hours of EEG data from the CHB-MIT dataset. Similarly, an CWM strategy with e-Glass reaches an accuracy of 74.5% on unseen data. These results demonstrate that e-Glass is capable of unobtrusive and real-time subject monitoring in outpatient conditions, not only in epileptic seizure detection but also in monitoring the subject’s cognitive state.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The United Nations projects that one in six people will be over 65 years old by 2050, most of them living in low- and middle-income countries1. As the population ages, the burden on national health systems is expected to increase, requiring smart solutions to help bend the cost curve of the current hospital-centered treatment structure. Among existing candidates, wearable devices are expected to contribute by providing continuous and personalized clinical data to enable early intervention and data-driven medical decisions2. By leveraging edge Machine Learning (edge-ML) and Internet-of-Things (IoT), wearables are the cornerstone to monitor, detect, and predict health conditions in real time3, e.g., in epileptic seizure detection4,5,6,7,8.

Epilepsy is a brain disorder characterized by recurrent seizures that shows a prevalence of 4 to 8 per 1000 population, placing it as the fourth most common neurological disorder worldwide9. In this use case, wearable-based epilepsy monitoring is considered an essential tool for patient management, providing real-time seizure tracking and alerts to patients and caregivers, which could prevent, for example, Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy (SUDEP)10. Currently, People With Epilepsy (PWE) can choose from a few validated solutions on the market: Epi-Care, Empatica, and Nightwatch11. These devices are validated for generalized tonic–clonic seizures (GTCS), which are characterized by strong movements, reaching reasonable performance metrics using only accelerometers and/or a few peripheral biosignals. However, GTCS represent less than 15% of all seizures faced by PWE12. Therefore, we require the use of electroencephalography (EEG) to tackle other seizure types, as brain activity monitoring is the golden standard to diagnose and monitor PWE12.

Existing commercially-available wireless EEG acquisition systems are, in general, cumbersome and stigmatizing, rendering them unacceptable to PWE13. As such, the development of wearable EEG faces several challenges. First, PWE requires inconspicuous form factors to avoid discrimination14. Second, they also require devices presenting low false-alarm rates (FAR) and high sensitivity to consider its adoption and long-term engagement11. The state-of-the-art (SoA) algorithms for subject monitoring rely on many EEG channels (i.e., a minimum of 18 channels), which are not available on wearable EEG devices7,15,16. To compensate for the reduced number of EEG channels of wearable EEG, we would require specialized and complex ML algorithms. However, the target devices are built on resource-constrained platforms (e.g., reduced memory, processing capacity, and battery size), to ensure portability, wearability/comfort, and unobtrusiveness.

To tackle the ML-based detection challenge, in our previous work, we pioneered the usage of only four EEG electrodes over the frontotemporal lobes to detect epileptic seizures that would fit a smart glasses form factor4,17,18. The eyeglasses form factor is also preferred for the AttentivU platform19, which targets attention and engagement feedback using one bipolar EEG channel over TP9 and TP10 scalp positions20. The work in21 presents a smart glasses for wearable healthcare and Human-Machine Interfaces (HMIs) combining EEG and electrooculography (EOG). More recently, the work in22 introduced GAPses, a smart glasses also integrating EEG and EOG data processing on a RISC-V processor (GAP9, Greenwaves Technologies) to tackle Steady-State Visual Evoked Potential, Motor Movement classification, and EEG-based biometrics (BrainMetrics). Although these platforms are versatile, they do not directly target epileptic seizure detection.

In this work, we present e-Glass, a state-of-the-art smart wearable system for real-time EEG monitoring targeting epilepsy. The e-Glass design concept, presented in Figure 1a, is meant for achieving an inconspicuous and unobtrusive wearable EEG by design, which are two essential characteristics to address the social stigma and discrimination problems. Moreover, e-Glass can deliver high performance on seizure detection for PWE using only a few EEG electrodes thanks to a tailored ML-based data processing framework optimized for resource-scarce devices 4,7,17. Finally, e-Glass real-time EEG processing can also be used for cognitive workload (CW) monitoring (CWM)23. Our main contributions are as follows:

-

we present a state-of-the-art wearable platform for unobtrusive EEG acquisition and processing in real-time, namely e-Glass, targeting personalized monitoring of PWE. Moreover, we present a lightweight edge-ML scheme tailored for e-Glass, which has limited resources (compute, memory, and energy).

-

we perform the electrical characterization of e-Glass’ hardware and assess the system’s EEG acquisition capability. e-Glass prototype presents as low as 0.16 \(\mu\) \(V_{RMS}\) of input-referred noise (IRN) and 18.41 noise-free bits (NFB), adhering to the guidelines for digital recording of clinical EEG of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology (IFCN)24. Moreover, e-Glass acquired signals reaches up to 0.93 of average Pearson’s correlation with the data from a research-grade EEG equipment, demonstrating similar band-power and alpha-wave synchronization during experimental tests.

-

we tackle the seizure detection problem, proposing a data processing framework tailored for ML-based EEG processing in resource-scarce devices as e-Glass. Testing this framework on all available data of the CHB-MIT dataset15 (982.9 hours of data), it reaches an overall sensitivity of 64% (100% sensitivity in 11 out of 24 subjects) and 2.35 false-alarms per day, considering only two bipolar EEG channels (i.e., F7T7 and F8T8). e-Glass can run up to 28.5 hours of operation on a single battery charge (225 \(mA\cdot h\) battery) when executing the proposed seizure detection scheme.

-

we explore a solution for real-time CWM on wearable devices composed of an ML design methodology and a data processing strategy, both validated on an experimental dataset. The proposed solution reaches an accuracy of 74.5% and a 74.0% geometric mean of sensitivity and specificity on unseen data.

(a) Proposed e-Glass system (parts: 1- main board, 2- Electrode snap connector, 3- battery casing, 4- bias electrodes); (b) hardware block diagram for e-Glass’ main board; (c) firmware state diagram, in which the main state displays four main threads used by e-Glass’ RTOS; (d) edge-ML scheme representing the data flow and processing within e-Glass.

In the following sections, first, we present the e-Glass system, describing hardware, firmware, and the ML-based data processing scheme adopted for its applications. Next, we extensively evaluate e-Glass, in terms of electrical characterization and EEG acquisition capabilities, as well as its performance in the context of epileptic seizure detection and cognitive workload monitoring application domains. Finally, we detail the methodology adopted for evaluating the device and conclude this work.

e-Glass

e-Glass is a state-of-the-art wearable device that builds on the conventional eyeglasses design, a widely-accepted form-factor of wearable technology, to allow unobtrusive real-time brain electrical activity monitoring (i.e., EEG). By integrating this capability into an everyday accessory, we aim to mitigate the social stigma and discrimination often associated with using bulky commercial EEG equipment13,14. Figure 1 depicts e-Glass system, its hardware and firmware main blocks, followed by the ML scheme used to process EEG onboard in real time. In the following, we describe each system component in detail.

e-Glass system and hardware architecture

The e-Glass hardware is embedded within the temples of the eyeglasses to maintain the appearance of a conventional wearable device. Figure 1 presents (a) the e-Glass system along with its detailed hardware architecture in the form of (b) a system block diagram. Four main parts are marked within Figure 1a: (1) the device’s main electronic board for data acquisition, processing, and communication; (2) a snap connector for the EEG electrodes; (3) the casing for the rechargeable ion-lithium battery; (4) EEG bias electrodes, to be discussed later. The e-Glass hardware is structured into four main subsystems: signal acquisition, data processing unit, communication interface, and onboard memory. Besides, we employ energy-efficient components, prioritizing subsystems capable of standalone operation and generating interrupt signals to the microcontroller whenever an intervention is needed.

e-Glass is designed based on ADS1299 front-end25 to provide four EEG channels using a referential electrode montage. We adopt the scalp positions F7, T7, F8, and T8, according to the 10–20 International Electrode System20, which were investigate previously for seizure detection4. The reference electrode is placed over the left mastoid bone. Additionally, the system incorporates an active bias electrode to drive a body point with a voltage potential within the system’s power rails and boost the common-mode rejection ratio (CMRR). The bias electrode is required to increase the systems CMRR, which can provide at least 13 dB gain26.

Concerning electrodes, e-Glass is designed to use soft-dry electrodes. This type of electrodes offer advantages in outpatient settings, requiring no conductive gel and minimal skin preparation. However, their use introduces challenges related to increased susceptibility to noise due to impedance mismatches. To address this issue, voltage followers are placed close to each electrode, implementing the concept of active electrodes within e-Glass27. This approach significantly increases the circuit’s input impedance as seen by each electrode, thereby reducing the voltage divider effect between the skin-electrode interface and the circuit input impedance. Furthermore, active electrodes enable on-site current amplification, enhancing signal strength and lowering cabling impedance, effectively mitigating noise caused by capacitive coupling.

e-Glass firmware architecture

The e-Glass firmware is built on the ARM CMSIS (Cortex Microcontroller Software Interface Standard) Real-Time Operating System (CMSIS-RTOS)28, utilizing STMicroelectronics low-level (LL) drivers and hardware abstraction layers (HAL)29. The adoption of an RTOS offers several advantages, including (1) deterministic behavior, ensuring predictable execution times and resource access during critical tasks; (2) an event-driven architecture that optimizes system responsiveness; (3) sophisticated scheduling algorithms that enable efficient task parallelism; and (4) robust, ready-to-use application programming interfaces (APIs) for memory management and self-monitoring, facilitating debugging and system reliability.

Figure 1c illustrates a simplified representation of the e-Glass firmware operation. As previously mentioned, an event-driven architecture was adopted to enhance energy efficiency, leveraging queues, mail queues, and semaphores to synchronize data transfers and task execution. Additionally, microcontroller external events are managed through interrupt service routines (ISRs), as shown on the right side of the super-state.

The four primary tasks within the e-Glass RTOS structure are encapsulated within the super-state labelled CMSIS-RTOS. Additional tasks were implemented to manage data communication via USB and Flash memory access. The main tasks are as follows:

-

SysMgnt – responsible for monitoring and controlling the basic functionalities of e-Glass, including push buttons, battery management, and system status;

-

DataMgmt – manages all data-related events, including Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) communication and signal acquisition (e.g., EEG and accelerometer data);

-

DataProc – executes real-time data processing routines for user monitoring;

-

Idle – a default RTOS task that uses the CPU when no other task is ready for execution.

Shared resources among tasks are synchronized using the HPmail and LPmail mail queues and the LPsemaphEvt semaphore. For instance, DataMgmt remains blocked while awaiting a HPmail message from an ISR (e.g., BLE or EEG front-end). These messages are stored in a FIFO queue, ensuring timely data processing. To prevent data loss or communication failures, DataMgmt is assigned the highest priority. For real-time processing, DataMgmt generates a LPmail for DataProc, then yields execution to trigger a context switch. It also sends LPmail messages to SysMgnt for BLE-based system adjustments or user requests. When all tasks are blocked, the Idle task runs. To reduce power consumption, the RTOS Idle hook enables tickless operation, suspending periodic tick interrupts until an event or task transition occurs. Upon resumption, the RTOS tick count is adjusted using the real-time clock count.

To minimize average current consumption, e-Glass leverages the low-power modes of the ARM Cortex-M4. The strategy prioritizes keeping the microcontroller in power-save mode, activating tickless operation whenever possible30. The system operates at its maximum core clock (i.e., 80 MHz) to efficiently execute tasks. When a task enters the blocked state, another task may run, if available; otherwise, the Idle task triggers low-power mode. Additionally, unused peripherals are clock-gated, while active peripherals alternate between running and low-power states to further reduce consumption.

The available ISRs, shown in light pink, include timing resources, external chip interrupts, and the user button interface. e-Glass utilises two timing sources: one for the CMSIS, based on a microcontroller hardware timer, and an RTC for the system-wide timestamping. External interrupts handle EEG front-end signals and accelerometer data availability. The signal acquisition subsystem stores all generated data in a circular buffer. When a data batch is ready, a HPmail is sent to the DataMgmt task. Similarly, the BLE ISR feeds a FIFO buffer and triggers a HPmail upon receiving a message.

e-Glass edge-ML

The hardware restrictions inherent in resource-constrained wearable devices increase the challenge of monitoring subjects in real-time and in outpatient settings, on a long-term basis. Nevertheless, current microcontroller architectures include advanced features such as single instruction multiple data (SIMD) and accelerators, larger RAM and Flash memory, and ultra-low-power modes, enabling the execution of tailored digital signal processing algorithms. Such characteristics foster the adoption of the edge computing paradigm and embedded ML to tackle the battery lifetime problem, thanks to the much lower power consumption of computation over communication23,31,32.

Leveraging the hardware and firmware features of e-Glass, we implemented real-time processing algorithms to support the basic application flow described in Figure 1c. We utilise the CMSIS-DSP library28, optimised for ARM microcontrollers, for algorithm implementation. However, to address CMSIS-DSP’s functional limitations, we supplement it with a cross-compiled GNU Scientific Library (GSL) for data processing. The basic building blocks include:

-

Data pre-processing: (1) sample-wise average removal to tackle high amplitude baseline wander and artifacts, to reduce signal overshooting when (2) band-pass filtering the data using an infinite impulse response (IIR) filter; (2) a lightweight artifact removal algorithm tailored for microcontroller-based systems with just a few EEG channels23; (3) GSL’s Discrete wavelet transform (DWT) to enhance time-frequency EEG features.

-

Feature extraction: classical features in EEG-based applications on time domain – line length, mean amplitude, mean, variance, standard deviation, and Hjorth parameters33,34, EEG power distribution per EEG band15, and EEG complexity estimations based on Shannon, Tsallis, Rényi, Sample, and Permutation entropy as defined in35.

-

ML model inference: Random Forest (RF) based inference, leveraging the power of ensemble models to achieve high accuracy with low data overfitting36.

Each edge ML block can be used independently or combined to achieve a custom application according to the accuracy requirements and the energy budget. An e-Glass application is expected to employ at least the filtering module, feature extraction algorithms, and an ML model to infer the subject’s condition regarding epilepsy monitoring or CW.

Results and discussion

In this section, first, we detail the results for the e-Glass electrical characterization in terms of input-referred noise level and other important parameters with regard to a guideline for digital recording of clinical EEG of the IFCN24. Second, we present the experimental results of e-Glass EEG acquisition in comparison with Biopac BN-EEG2 (Biopac Systems, Inc.), a commercial research-grade equipment. Lastly, we discuss the main results for two forecasting applications – seizure detection and cognitive workload monitoring (CWM).

e-Glass’ hardware electrical characterization

Excessive circuit noise can degrade the performance of analog-to-digital converters (ADC), particularly in low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) applications like EEG acquisition. Key ADC parameters are critical for achieving low-noise data acquisition. The ADS1299 datasheet provides figures for input-referred noise (IRN), dynamic range (DR), noise-free bits (NFB), and effective number of bits (ENOB) across different sampling rates and input gains. Moreover, the IFCN has proposed a set of guidelines for digital recording of clinical EEG, which indicates: 1) minimum sampling frequency (Fs) of 200 samples/s; 2) minimum resolution of 0.5 \(\mu\)V; 3) input impedance of 100 M\(\Omega\) or more; 4) CMRR of at least 110 dB for each channel measured at the amplifier input; 5) IRN of less than 1.5 \(\mu\)V peak-to-peak at any frequency from 0.5–100 Hz24.

Table 1 compares IFCN guidelines and e-Glass electrical characteristics obtained by the IRN measurement and CMRR determination. The use of the ADS1299 front-end, designed explicitly for EEG acquisition, allows e-Glass system to outperform the IFCN guidelines. The minimum sampling frequency of ADS1299 is already greater than the required value while providing the lowest acquisition noise. Regarding input impedance, the input voltage follower has a maximum input bias current of 1 pA. As the input resistance is measured by the input-current change over input-voltage change, e-Glass’ input impedance is expected to be superior to 1 G\(\Omega\). Moreover, the oversampling and filtering mechanisms available in \(\delta\) \(\sigma\) analog-to-digital converters (ADC), as in ADS1299, explain the substantially inferior IRN of e-Glass at a specific frequency (i.e., 50 Hz in the assessed data) concerning IFCN. Finally, ADS1299 guarantee at least 110 dB of CMRR at the amplifier imput, as required by the IFCN standard. However, we also assessed e-Glass’ open-loop CMRR, measuring it at the EEG electrode snap connector, which achieves 89.1 dB already considering the degradation caused by input protection and filtering. Nonetheless, this value shall increase dynamically by at least 13 dB boosted by the BIAS circuit26. Therefore, e-Glass would present at least 102 dB of CMRR, which is considered satisfactory as the target frequency band is 30 Hz or less.

Finally, excessive circuit noise can degrade the performance of ADC. Table 2 shows the results for IRN measurement along with other key ADC performance parameters as dynamic range (DR), noise-free bits (NFB), and effective number of bits (ENOB). In its datasheet, ADS1299 presents IRN values obtained as an average of the measurement of various demonstration boards but disconsider external input circuitry, which adds noise (e.g., Johnson–Nyquist noise). The e-Glass measurement is taken from the electrode snap connector input, in a more conservative approach. Thus, the slightest higher IRN obtained indicates the quality o e-Glass hardware design.

e-Glass’ EEG acquisition assessment

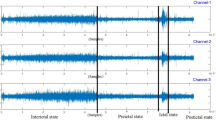

In addition to bench tests, we assess e-Glass capacity to acquire brain activity based on a comparative analysis against Biopac’s BN-EEG2, a commercial research equipment37,38,39. First, Fig. 2 presents short EEG example acquired from Sub. 12 simultaneously by e-Glass and BN-EEG2. A distinct alpha wave (i.e, EEG synchronization around 10 Hz) is visible following eye closure, which is an indicative of brain activity acquisition40. Second, we obtain the power spectrum density (PSD) from spontaneous EEG recorded during the eyes-closed part of Task 1 (Session 1) of the experimental setup. As presented in Figure 3, alpha-band (i.e. [8–12]Hz) energy synchronization can be observed in most of the subjects (e.g., Sub 4, Sub 8, Sub 12). Moreover, a visual assessment shows a strong correlation between e-Glass and BN-EEG2 data’s PSD. In some cases, e-Glass signals exhibit greater energy in the lower frequency range (0.5–3 Hz), likely due to electrode-skin impedance mismatches common on systems using dry electrodes41. The Bland-Altaman scatterplot42 in Fig. 4 allows for assessing the agreement between the two methods of EEG acquisition, focusing on the PSD differences. We observe a small mean bias between measurements for all subjects and small differences in PSD (the majority of data points are within the 95% confidence interval).

Finally, Table 3 presents Pearson’s correlation coefficients obtained after applying the Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) on 1 minute of EEG data to account for the difference in sampling frequency between systems. e-Glass signals showed a high correlation with Biopac’s for most subjects, reaching an average correlation of 0.93 on the F7 electrode during eyes open task. The high correlation obtained indicates that e-Glass system can produce an equivalent measurement of a subject brain activity to a commercial research-grade device. Notably, the lower correlation observed for the F7 signal during the eyes-closed state in Subject 10 is attributed to a high-amplitude blinking artifact, as confirmed by visual inspection of the data.

Application results

Table 4 summarizes the performance metrics for seizure detection obtained using Times-Slice Cross-Validation (TSCV) scheme. Using data from 18 EEG channels (i.e., full-cap), our approach achieves an average sensitivity of 80%, correctly identifying 99 out of 132 tested seizures. However, as discussed before, such a solution is certainly not acceptable to PWE, due to the stigma associated with the EEG caps/hats. When limited to e-Glass electrodes, sensitivity decreases to 64%, as expected, given that some subjects (e.g., CHB17 and CHB21) lack ictal activity in the frontotemporal lobes. Nevertheless, the proposed method achieves 100% sensitivity in eleven subjects, demonstrating its potential for PWE monitoring based on wearable devices.

Moreover, achieved FAR of 2.35/day and 1.81/day, for the e-Glass and the full-cap solution, respectively, are close to the target of one false alarm per day even considering the low EEG-channel count of e-Glass43. These results are on par with the work in44, a similar SoA work that reached average sensitivity of 65.27% combining seizure and artifact detection to reduce FAR, but showing up to 24 false alarms per day, compared to e-Glass with only 2.35 false alarms per day. Even when compared with a work which employs convolution networks to detect seizures using a minimum of 18 EEG channels, e-Glass’s average F1 and sensitivity (i.e., 59% and 64%, respectively) is on par with the F1 of 59% and sensitivity of 58.3% presented in16, but achieving much lower FAR than this work’s 0.5/h (i.e., 12/day).

In addition to seizure detection, we also evaluate e-glass in the context of CWM. Similarly to seizure detection results, our proposed approach for CWM using four monopolar EEG channels shows only a 6.2% lower geometric mean (Gmean) of sensitivity and specificity in the test set opposed to the full-cap solution (Table 5). Moreover, the we propose an RF model optimization that reduces Flash memory requirements by 5.7x with respect to the full-cap one. Similar differences are observed for the other performance scores. Although the full-cap provides slightly higher scores, such a solution would not fit the user’s desire for an inconspicuous wearable EEG device13,14. Finally, our results are on par with the SoA. For example, the study in45 achieved an accuracy of 77% for the same dataset, but using only the full-cap solution, and the work in46 achieves accuracy of 80.2% with the need of using four peripheral biosignals, both works targeting cumbersome systems. Therefore, our proposed solution based on e-Glass achieves satisfactory results, on an low EEG-channel’s count device, toward enabling awareness of the operators’ cognitive states on HMI.

Finally, our proposed edge-ML methodology has a very low latency, taking 26.45 ms to process each seizure detection inference and 56.4 ms on the CWM one. This leaves the CPU idle for up to 97% of the time, which allows us to reduce the e-Glass average current consumption to approximately 7.8 mA (ADS1299 always on draws around 4.6 mA), leading to up to 28.5 hours of operation on a single battery charge (225 \(mA\cdot h\) battery). Regarding RAM memory, the CLF algorithm demands up to 4774 bytes on the seizure detection application, while the CWM one uses up to 8256 bytes due to extra signal storage for the artifact removal algorithm.

Methods

To validate the e-Glass system, we developed a prototype based on an adjustable 3D design, to be able to fit to various head sizes among the subjects (Fig. 5a). This prototype incorporates a piston mechanism for electrode housing with a built-in spring to increase electrode-skin pressure and dampen small vibrations to improve EEG signal to noise ratio. In the following paragraphs, we present the methodology adopted to perform the electrical characterization of e-Glass’ hardware and the experimental setup to assess the system’s EEG acquisition capability. The latter has been executed in comparison with a commercial equipment from Biopac Inc, for which EEG has been acquired with both systems at the same time and close electrode positions as displayed in Fig. 5b. Lastly, we also present two foreseeing applications for e-Glass device and describe the ML strategy we adopt to evaluate them.

e-Glass prototype: hardware design and validation

Figure 5a presents e-Glass 3D design including: (1) e-Glass’ main electronic board for data acquisition, processing, and communication; (2) four EEG channels, including active electrodes and the proposed piston-like electrode housing; (3) ion-lithium battery casing; (4) bias electrodes; (5) reference electrodes; (6) the piston-like electrode housing and the SoftPulse soft-dry electrodes from Dätwyler Holding Inc..

All components in the e-Glass electronic board are off-the-shelf, industry-grade, ensuring suitability for medical applications. For instance, the ADS1299 is leveraged on the prototype to reach a compact EEG front-end offering up to 22 nV/bit resolution and <1 \(\mu \hbox {V}_{RMS}\) IRN. Moreover, while simultaneously acquiring data from four channels, ADS1299 consumes only 22mW (4.6mA) in active mode. Second, for data processing, the e-Glass prototype employs an STM32L476 microcontroller, featuring an ultra-low-power ARM 32-bit Cortex-M4 architecture with 1 MB Flash and 128 KB RAM. Running at up to 80 MHz, it achieves 1.25 DMIPS/MHz (Dhrystone 2.1 benchmark). The microcontroller supports nine power modes and clock-gating to optimize energy efficiency, consuming just 1.4 \(\upmu\)A in Stop2 mode while retaining data and RTC functionality. Third, e-Glass includes two communication interfaces: 1) Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) via the STMicroelectronics BlueNRG-MS chip and 2) USB 2.0. BLE enables data exchange with a proprietary app for internet connectivity and status monitoring. Since e-Glass processes data in real time, BLE throughput requirements are minimized, though it can stream data at higher energy costs–drawing 8.2 mA during transmission (0 dBm) and only 2.4 \(\upmu\)A in Sleep mode. Additionally, the system features a 64 Mbit external Flash memory for data logging, consuming 3.5 mA at peak during write cycles.

Electrical characterization

To validate the e-Glass noise performance, a minimum of 10,000 consecutive samples are acquired with the EEG channels short-circuited externally to the ADS1299 EEG front end (Fig. 6). As the ADS1299 is powered by a single supply, the channel inputs and reference are shorted to a known voltage within the power rail (i.e., 1.5 V from the battery). The root-mean-square (RMS) value of the IRN is estimated from the average power of the acquired samples, as defined in (1). The peak-to-peak value of the IRN is estimated by multiplying its RMS by 6.625.

Once we obtained the IRN, the dynamic range (DR), noise-free bits (NFB), and effective number of bits (ENOB) are calculated using Equations (2),(3), and (4)47. Voltage followers at the active electrodes, input protection and filters have their noise contributions accounted for during measurement. The system is configured for maximum input gain (24 V/V) and lowest sampling frequency (250 Hz), aligning with its target operation.

Following a similar experimental approach, the system’s CMRR is evaluated by replacing the battery with a sinusoidal signal, generated using a LeCroy WaveStation (2012). CMRR is measured at 50 Hz by applying a sin wave of 100 \(mV_P\), with an offset of 2.5 \(V_{DC}\) as e-Glass’ ADS1299 is powered by a single supply. To guarantee correct input amplitude (\(V_{IN_{P}}\)), we used a Tektronix TDS 2024B oscilloscope to calibrate the testing signal. At least 2 minutes of data are used for the IRN estimation using the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT). The CMRR is then calculated using (5):

EEG acquisition and processing

Twelve healthy volunteers participated in an EEG acquisition study using e-Glass alongside a Biopac BN-EEG2 module (Biopac Systems, Inc). The study was divided into two experimental sessions, as presented in Fig. 7a, lasting for approximately one hour. Each volunteer undertook two data acquisition sessions of 10 minutes each, separated by a resting time of 5 minutes. Each session presented two tasks: 1) spontaneous EEG acquisition, including eyes open/closed changes, and 2) subject movement (i.e., sitting/standing) to elicit movement artifacts. The experiments followed the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by La commission cantonale d’éthique de la recherche sur l’être humain (CER-VD), Vaud - CH, under project ID 2022-01338. Furthermore, as per48, this sample size is considered appropriate for a pilot study assessing e-Glass reliability in EEG acquisition.

On the day of the experiment, each volunteer received a briefing on the experimental steps and signed an informed consent form. We then prepared each volunteer for the data acquisition by placing both the e-Glass system and the Biopac BN-EEG2, as shown in Fig. 7b. BN-EEG2 uses commercial Ag/AgCl EEG cup electrodes with EEG paste, while e-Glass electrodes were cleaned with alcohol to remove fat. Both systems’ electrodes were placed side by side for simultaneous signal acquisition. Since BN-EEG2 has only two EEG channels, we recorded e-Glass’ F7 and T7 signals for comparison. A synchronization trigger was coupled to both systems to allow posterior off-line data processing synchronization. In the case of e-Glass, the trigger signal was acquired using one of its analog inputs. An optocoupler was used to isolate the trigger circuit, avoiding unwanted conducted-noise coupling to e-Glass acquired signals.

The acquired signals are filtered between 1 and 30 Hz using a fourth-order Butterworth filter. Then, we divide the acquired data per experimental task using the trigger signal for synchronization. The spontaneous EEG is visually inspected for artifacts and used for validating e-Glass’s acquisition. First, we assess e-Glass’ data quality in the time domain by using Pearson’s correlation, which requires a sampling-frequency correction using the DTW method. The correlation is calculated over a 60-second window obtained from the Session 1 eyes open/closed task 1. Second, we apply Welch’s Periodogram to estimate the PSD from the 3-minute spontaneous EEG recorded during the eyes-closed phase of Session 1 (Task 1). The PSD is estimated considering 4-second EEG epochs. The results are plotted for visual inspection. In addition, we use the Bland-Altman method to assess spectral differences between equipment measurements42.

e-Glass applications

Long-term EEG monitoring has the potential to provide key clinical information for personalized epilepsy treatment43 and can provide important markers to estimate cognitive workload (CW)49. Hence, in the following paragraph, we present methods used to evaluate the EEG-based epilepsy detection and CWM applications envisioned for e-Glass in4,7,23. For epilepsy detection, we report sensitivity (Sens), precision (Prec), F1-score, and FAR/day, as the data is very imbalanced. In addition to sensitivity, for CWM, we report specificity (Spec), accuracy (Acc), and Gmean of sensitivity and specificity as the data is balanced in this case. These scores are defined as follows:

where Tp, Tn, Fp, and Fn stand for true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively. \(total\_time\) corresponds to the total amount of hours of data in the test set. All ML training/testing is done offline in both applications, using MATLAB and python routines.

Furthermore, we employ tools for code execution profiling and energy consumption estimation in order to assess memory requirements and battery lifetime in both applications. First, we use the RTOS tracing utility to account for thread execution time. Second, we combine the use of FreeRTOS tools with a manual account of dynamically allocated memory to estimate RAM. Last, we use the Otii Arc Pro50 commercial acquisition system to measure the average current consumption of e-Glass while executing the target ML-based application.

Epilepsy detection

We employ the CHB-MIT Scalp15 dataset to develop and evaluate an ML methodology for seizure detection. This dataset contains scalp EEG recordings from 24 pediatric patients, acquired using a bipolar montage at a sampling rate of 256 Hz. It includes a total of 198 annotated seizure events across 982.9 hours of data.

This application is evaluated in two scenarios: (1) using the data of all electrodes available for all subjects (i.e., 18 channels) and (2) using only the e-Glass channels (i.e., F7T7 and F8T8). We pre-process the EEG signals using a zero-phase, 4th-order Butterworth band-pass filter between [1, 20] Hz. The filtered data is divided into windows of \(4\,s\) with a \(0.5\,s\) step (87.5\(\%\) overlapping) before extracting 56 classical literature features per EEG window, per EEG channel, as described in7.

For model evaluation, we employ a TSCV approach7, ensuring that all available data is used in the training and testing tasks. To ensure sufficient training data, we require a minimum of 5 hours of EEG recordings for the first model in the TSCV procedure, with at least one seizure event included. We post-process the results using the Bayesian approach described in7 before evaluating performance using the SZcore framework51, providing seizure detection metrics at the event level.

Cognitive workload monitoring

CWM can enhance human-machine interaction (HMI) by supporting task execution assistance, considering the operator’s cognitive state. To assess CWM solution tailored for e-Glass, we employ the in-house dataset described in46, which contains data of 24 volunteers (27.7 ± 4.8 years old) acquired while executing a simulated search and rescue (SAR) mission. Once more, the application is evaluated in two scenarios: (1) using the data of all electrodes available for all subjects and (2) using only the e-Glass channels (i.e., F7, T7, F8, and T8). The experimental setup is described in detail in23. In this case, besides bandpass filtering the data, we also employ the artifact removal technique developed for e-Glass system. We evaluate various data processing optimizations and achieve the best results considering: (1) EEG data windows of 56 s with 60% overlap, (2) a 200-tree RF model, and (3) only 18 features after running a 30-fold recursive feature elimination on cross-validation (RFECV).

Conclusion

Real-time brain activity monitoring using wearable technologies enables continuous and non-invasive tracking of EEG in everyday environments on a personalized and long-term basis, supporting a wide range of health applications, from epileptic seizure detection to cognitive workload monitoring.

In this article, we present a state-of-the-art smart wearable system for unobtrusive EEG acquisition and processing in real-time, namely e-Glass, targeting personalized monitoring of neurological disorders. e-Glass tests shows it adhere to the guidelines for digital recording of clinical EEG of the IFCN24, have presented 1.07 \(\mu\) \(V_P\) of IRN, 18.41 noise-free bits (NFB), hight input impedance and CMRR. Moreover, in a pilot study in healthy subjects, e-Glass’ acquired data showed high correlation with the data from a research-grade EEG system (up to 0.93 in average Pearson’s correlation). We assessed two possible applications for e-Glass, the seizure detection and cognitive workload monitoring problem. The epilepsy data processing framework we tailored for ML-based EEG processing in resource-scarce devices as e-Glass reached 100% sensitivity in 11 out of 24 subjects, with average sensitivity and FAR of 63.8% and 2.35/day considering only two bipolar EEG channels (i.e., F7T7, F8T8). e-Glass can run the seizure detection ML algorithm for up to 28.5 hours on a single battery charge, which is on par with the desire of PWE for these type of devices.

On a more versatile application, we demonstrated that e-Glass may also be used for real-time CWM, having reached an accuracy of 74.5% and a 74.0% geometric mean of sensitivity and specificity on unseen data when validated on a in-house dataset. Thus, e-Glass may be used to enhance HMI by bringing the operator’s cognitive state information into consideration during work hours. Overall, e-Glass offers a state-of-the-art wearable platform for real-time EEG monitoring based applications as epilepsy detection and CWM.

Data availability

The seizure data used in this work is from a public database (CHB-MIT scalp EEG database), which could be accessed and downloaded via https://physionet.org/content/chbmit/1.0.0/. The dataset used for CWM was generated by Dr. Fabio Dell’Agnola, Dr. Ping-Keng Jao, Dr. Ricardo Chavarriaga, and Prof. José del R. Millán on the project no. PB2017-00295 (Swiss CER-VD ethical committee), and could be available through Prof. Millán’s authorization under reasonable request. Similarly, the e-Glass acquired data could also be available under reasonable request to the work’s corresponding author.

References

World Health Organization. Ageing and health. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health. [Accessed 15-Oct-2025].

Wall, C., Hetherington, V. & Godfrey, A. Beyond the clinic: the rise of wearables and smartphones in decentralising healthcare. npj Digital Medicine 6, 219, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-023-00971-z (2023).

Canali, S., Schiaffonati, V. & Aliverti, A. Challenges and recommendations for wearable devices in digital health: Data quality, interoperability, health equity, fairness. PLOS Digit. Heal. 1, e0000104. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pdig.0000104 (2022).

Sopic, D., Aminifar, A. & Atienza, D. e-Glass: A Wearable System for Real-Time Detection of Epileptic Seizures. In 2018 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), 1–5, https://doi.org/10.1109/ISCAS.2018.8351728 (IEEE, Florence, Italy, 2018).

Forooghifar, F., Aminifar, A. & Atienza, D. Resource-aware distributed epilepsy monitoring using self-awareness from edge to cloud. IEEE transactions on biomedical circuits and systems 13, 1338–1350 (2019).

Baghersalimi, S., Teijeiro, T., Atienza, D. & Aminifar, A. Personalized real-time federated learning for epileptic seizure detection. IEEE journal of biomedical and health informatics 26, 898–909 (2021).

Zanetti, R., Pale, U., Teijeiro, T. & Atienza, D. Approximate zero-crossing: a new interpretable, highly discriminative and low-complexity feature for EEG and iEEG seizure detection. J. Neural Eng. 19, 066018. https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-2552/aca1e4 (2022).

Amirshahi, A., Thomas, A., Aminifar, A., Rosing, T. & Atienza, D. M2d2: Maximum-mean-discrepancy decoder for temporal localization of epileptic brain activities. IEEE J. Biomed. Heal. Informatics 27, 202–214 (2022).

World Health Organization. Neurological disorders : public health challenges (2006).

Beniczky, S., Lhatoo, S., Sperling, M. & Ryvlin, P. Artificial intelligence, digital technology, and mobile health in epilepsy, https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.18435 (2025).

Hadady, L., Robinson, T., Bruno, E., Richardson, M. P. & Beniczky, S. Users’ perspectives and preferences on using wearables in epilepsy: A critical review. Epilepsia n/a, https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.18280. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/epi.18280.

Tatum, W. et al. Clinical utility of EEG in diagnosing and monitoring epilepsy in adults. Clin Neurophysiol. 129, 1056–1082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2018.01.019 (2018).

Hoppe, C. et al. Novel techniques for automated seizure registration: Patients’ wants and needs. Epilepsy Behav. 52, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.08.006 (2015).

Bruno, E. et al. Wearable technology in epilepsy: The views of patients, caregivers, and healthcare professionals. Epilepsy & Behav. 85, 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.05.044 (2018).

Shoeb, A. & Guttag, J. Application of machine learning to epileptic seizure detection. In Proc. 27th ICML, 975–982 (Haifa, Israel, 2010).

Gómez, C. et al. Automatic seizure detection based on imaged-EEG signals through fully convolutional networks. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-78784-3 (2020).

Zanetti, R., Aminifar, A. & Atienza, D. Robust Epileptic Seizure Detection on Wearable Systems with Reduced False-Alarm Rate. In 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), 4248–4251, https://doi.org/10.1109/EMBC44109.2020.9175339 (IEEE, 2020).

Aminifar, A., Sopic, D., Atienza Alonso, D. & Zanetti, R. A Wearable System For Real-Time Detection of Epileptic Seizures (Patent EPO - EP3755219, Granted 30.05.2025).

Kosmyna, N. AttentivU: A Wearable Pair of EEG and EOG Glasses for Real-Time Physiological Processing (Conference Presentation). In Optical Architectures for Displays and Sensing in Augmented, Virtual, and Mixed Reality (AR, VR, MR), 107, https://doi.org/10.1117/12.2566398 (SPIE, San Francisco, United States, 2020).

Klem, G. H., Lüders, H. O., Jasper, H. H. & Elger, C. The ten-twenty electrode system of the International Federation. The International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. Electroencephalogr. clinical neurophysiology. Suppl. 52, 3–6 (1999).

Lee, J. H. et al. 3D Printed, Customizable, and Multifunctional Smart Electronic Eyeglasses for Wearable Healthcare Systems and Human-Machine Interfaces. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 21424–21432. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.0c03110 (2020).

Frey, S. et al. GAPses: Versatile Smart Glasses for Comfortable and Fully-Dry Acquisition and Parallel Ultra-Low-Power Processing of EEG and EOG. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 19, 616–628. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBCAS.2024.3478798 (2025).

Zanetti, R., Arza, A., Aminifar, A. & Atienza, D. Real-Time EEG-Based Cognitive Workload Monitoring on Wearable Devices. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 69, 265–277. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2021.3092206 (2022).

Nuwer, M. R. et al. IFCN standards for digital recording of clinical EEG. International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. Electroencephalogr. clinical neurophysiology 106, 259–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0013-4694(97)00106-5 (1998).

Texas Instruments. ADS1299 Datasheet. https://www.ti.com/lit/ds/symlink/ads1299.pdf (2017). [Accessed 12-Oct-2025].

Acharya, V. Improving Common-Mode Rejection Using the Right-Leg Drive Amplifier. Tech. Rep., Texas Instruments (2011). Issue: July.

Guermandi, M., Cardu, R., Franchi Scarselli, E. & Guerrieri, R. Active Electrode IC for EEG and Electrical Impedance Tomography With Continuous Monitoring of Contact Impedance. IEEE Transactions on Biomed. Circuits Syst. 9, 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBCAS.2014.2311836 (2015).

CMSIS DSP Software Library. https://arm-software.github.io/CMSIS_5/DSP/html/index.html. [Accessed 12-Oct-2025].

STMicroelectronics. Um1725 - introduction description of stm32f4 hal and low-layer drivers (2023).

Braojos Lopez, R., Beretta, I., Ansaloni, G. & Atienza Alonso, D. Hardware/Software Approach for Code Synchronization in Low-Power Multi-Core Sensor Nodes (2014).

Surrel, G., Aminifar, A., Rincón, F., Murali, S. & Atienza, D. Online Obstructive Sleep Apnea Detection on Medical Wearable Sensors. IEEE Transactions on Biomed. Circuits Syst. 1–12 (2018).

Sopic, D., Aminifar, A., Aminifar, A. & Atienza, D. Real-Time Event-Driven Classification Technique for Early Detection and Prevention of Myocardial Infarction on Wearable Systems. IEEE Transactions on Biomed. Circuits Syst. 12, 982–992. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBCAS.2018.2848477 (2018).

Burrello, A., Benatti, S., Schindler, K., Benini, L. & Rahimi, A. An Ensemble of Hyperdimensional Classifiers: Hardware-Friendly Short-Latency Seizure Detection With Automatic iEEG Electrode Selection. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 25, 935–946. https://doi.org/10.1109/JBHI.2020.3022211 (2021).

Jenke, R., Peer, A. & Buss, M. Feature extraction and selection for emotion recognition from EEG. IEEE Transactions on Affect. Comput. 5, 327–339. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAFFC.2014.2339834 (2014).

Acharya, U. R., Fujita, H., Sudarshan, V. K., Bhat, S. & Koh, J. E. W. Application of entropies for automated diagnosis of epilepsy using EEG signals: A review. Knowledge-Based Syst. 88, 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2015.08.004 (2015).

Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010933404324 (2001).

Badcock, N. A. et al. Validation of the Emotiv EPOC®EEG gaming system for measuring research quality auditory ERPs. PeerJ 1, e38, https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.38 (2013). Publisher: PeerJ Inc.

Kam, J. W. Y. et al. Systematic comparison between a wireless EEG system with dry electrodes and a wired EEG system with wet electrodes. NeuroImage 184, 119–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.09.012 (2019).

von Luhmann, A., Wabnitz, H., Sander, T. & Muller, K.-R. M3BA: A Mobile, Modular, Multimodal Biosignal Acquisition Architecture for Miniaturized EEG-NIRS-Based Hybrid BCI and Monitoring. IEEE Transactions on Biomed. Eng. 64, 1199–1210. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2016.2594127 (2017).

Benedek, M., Bergner, S., Könen, T., Fink, A. & Neubauer, A. C. EEG alpha synchronization is related to top-down processing in convergent and divergent thinking. Neuropsychologia 49, 3505–3511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.09.04 (2011).

Li, G., Wang, S. & Duan, Y. Y. Towards gel-free electrodes: A systematic study of electrode-skin impedance. Sensors Actuators B: Chem. 241, 1244–1255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2016.10.005 (2017).

Martin Bland, J. & Altman, D. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. The Lancet 327, 307–310, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(86)90837-8 (1986). Originally published as Volume 1, Issue 8476.

Hubbard, I., Beniczky, S. & Ryvlin, P. The Challenging Path to Developing a Mobile Health Device for Epilepsy: The Current Landscape and Where We Go From Here. Front. Neurol. 12, 740743. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.740743 (2021).

Ingolfsson, T. M. et al. Minimizing artifact-induced false-alarms for seizure detection in wearable EEG devices with gradient-boosted tree classifiers. Sci. Reports 14, 2980. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-52551-0 (2024).

Jao, P. K. et al. EEG Correlates of Difficulty Levels in Dynamical Transitions of Simulated Flying and Mapping Tasks. IEEE Transactions on Human-Machine Syst. 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1109/THMS.2020.3038339 (2020).

Dell’Agnola, F., Momeni, N., Arza, A. & Atienza, D. Cognitive workload monitoring in virtual reality based rescue missions with drones. In 12th International Conference on Virtual, Augmented and Mixed Reality, 397–409 (Copenhagen, 2020).

Baker, B. A Glossary of Analog-to-Digital Specifications and Performance Characteristics. Tech. Rep., (Texas Instruments, 2011). Issue: August 2006.

Julious, S. A. Sample size of 12 per group rule of thumb for a pilot study. Pharm. Stat. 4, 287–291. https://doi.org/10.1002/pst.185 (2005).

Borghini, G., Astolfi, L., Vecchiato, G., Mattia, D. & Babiloni, F. Measuring neurophysiological signals in aircraft pilots and car drivers for the assessment of mental workload, fatigue and drowsiness. Neurosci. & Biobehav. Rev. 44, 58–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.10.003 (2014).

Qoitech. Otii Arc Pro. https://www.qoitech.com/otii-arc-pro/. [Accessed 12-Oct-2025].

Dan, J. et al. SzCORE: A Seizure Community Open-source Research Evaluation framework for the validation of EEG-based automated seizure detection algorithms (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work has been partially supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie (grant agreement No. 754354), the e-Glass project (EPFL Enable project No. 6.1828), the Swiss NSF: “Edge-Companions: Hardware/Software Co-Optimization Toward Energy-Minimal Health Monitoring at the Edge” (grant no. 10.002.812), the Swedish Research Council, and the Wallenberg AI, Autonomous Systems and Software Program. This research was partially conducted by ACCESS – AI Chip Center for Emerging Smart Systems, supported by the InnoHK initiative of the Innovation and Technology Commission of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. We thank Prof. MD Philippe Ryvlin for the many discussions on wearable-based seizure detection and support on the e-Glass project. Finally, we also thank Dr. Jérôme Thevenot for his support in obtaining the ethical committee approval needed for this project’s data acquisition and for designing e-Glass’ latest 3D frame.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.Z. conceived and conducted the experiments, executed the data analysis, and wrote the original draft. A.A. was responsible for the project conceptualization, methodology proposal, and writing/reviewing the original draft. D.A. conceptualized the project, being responsible for supervision, resources, and final manuscript review. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare having a patent on a wearable system for real-time detection of epileptic seizures (Patent EPO - EP3755219, Granted 30.05.2025). The patent is authored by: Aminifar, Amir; Sopic, Dionisije; Atienza Alonso, David; and Zanetti, Renato.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zanetti, R., Aminifar, A. & Atienza, D. EEG glasses for real-time brain electrical activity monitoring. Sci Rep 15, 43574 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29893-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29893-4