Abstract

The main aim of this research study is to examine optical soliton phenomena in a (2+1)-dimensional Schrödinger class nonlinear model that degenerates from Biswas-Milovic equation (BME) using Riccati modified extended simple equation method (RMESEM). This model has particular relevance in the fiber optics domain. The proposed anstaz RMESEM uses a complex structured wave transformation to produce nonlinear ordinary differential equation (NODE) and constraint conditions for Kerr law nonlinearity form of the model. The resulting NODE is assumed to have a closed form solution that converts it into a system of nonlinear algebraic equations via substitution in order to determine fresh variety of optical soliton solutions. The final visualizations of the obtained optical soliton solutions in the form of 3D, contour, and 2D forms demonstrate that the model develops Hopf bifurcation, rogue and internal envelope solitons as a result of the elastic and inelastic collision of optical periodic solitons while the norms of the obtained optical soliton reveal dark and bright kink structures. Using phase portraits and time-series maps, we also study bifurcating and chaotic behavior, observing its presence in the perturbed dynamical system and obtaining favorable results indicating Hopf bifurcation and periodicity. We use a generalized trigonometric function to perturb the planner system for the first time in order carry out chaotic analysis. Furthermore, our results are analyzed and linked to the soliton dynamics in BME, demonstrating the effectiveness of the suggested method as an effective method of identifying novel soliton phenomena within such nonlinear settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nonlinear partial differential equations (NPDEs) and Fractional NPDEs (FNPDEs) have been utilized to model a variety of physical phenomena over the past few decades1,2,3. Many academics have expressed interest in NPDEs, and a wide range of discrete and continuous methods have been developed and applied to different theories, equations, models, and their solutions. Such methods include, extended Fan’s sub-ODE technique4, polynomial expansion method5, discrete tanh method6, Weierstrass elliptic function expansion method7, differential-difference Jacobi elliptic functions sub-ODE method8, Lie symmetry method9, exp-function technique10, F-expansion approach11, modified Kudryashov method12, extended trial equation method13, extended tanh function technique14, generalized three-wave method15, the soliton ansatz method16, Hirota bilinear technique17, the variational method18, modified simple equation approach19, the first integral method20, the sine-cosine method21, the generalised Kudryashov method22, the Riccatti-Bernoulli sub-ODE method23, the functional variable method24, the Jacobi elliptic function method25, the modified Khater method26, the RMESEM27,28,29, the \((G'/G)\)-expansion method30,31,32, the tanh-coth method33, the generalized Kudryashov auxiliary method34, extended direct algebraic method (EDAM)35,36,37,38 and several additional methods39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47.

Among the NPDEs, those pertaining to optics are particularly significant and of great study interest. In the past few decades, several aspects that serve as the basis for research on optical solitons such as physical models of optical solitons48, the emergence of some notions pertaining to these models, such as dispersion49, perturbation50, and refractive index51, into the literature and highlighting their significance, new findings as a consequence of recent investigations and studies, and their endorsement with laboratory experiments have been identified. These may also include optical fiber technology, which serves as the foundation for modern optical fiber-based communication and internet technologies as well as research on optical nonlinearity in opto-electronic devices that fall under this category52. Because of their limited mode area, fibers have a very long interaction length and high density. As a result, these nonlinearities can have significant consequences on fibers, which are frequently unanticipated, hard to detect, and involve very complicated circumstances. As is well known, the quality, efficiency, and speed of transmitting signals in optical fibers are influenced by three primary criteria. These include polarization mode dispersion (PMD)53, chromatic dispersion (CD) or group velocity dispersion (GVD)54, and the nonlinear effects55. The final one, nonlinear effects, includes the primary nonlinear phenomena that happen in single-mode fibers, including Raman scattering56, Kerr effect57, and58 Brillouin scattering. Numerous applications of this kind have made mathematicians interested in studying optics. This article focuses on the degenerated form of a prominent nonlinear model called BME with Kerr law nonlinearity. The BME equation, which was first presented in 201059, is one of the several models and equations that have been created and presented to investigate the propagation of optical solitons using nonlinear techniques based on the nonlinear Schrödinger equation (NLSE). Numerous investigations have been conducted on the BME equation, which has a special significance in the field of fiber optics60. The generalized form of BME is expressed as61,62,63:

where \({P}={P}(t,x,y)\) is a complex structured wave function that signifies optical field amplitude. Moreover, the general representation of evolution is represented by the first term in (1), followed by the term of general form of the group velocity dispersion term (GVD), the general form of the non-Kerr law nonlinearity is represented by third term which involves \(f(\Phi )\) that represents a real-valued algebraic function, \(({n}, \quad {n}\ge 1)\) is a parameter that generalizes the model from NLSE to BME while p, q, and \({\kappa }\) are real valued parameters. Moreover, (1) degenerates into the (2+1)-dimensional NLSE version of BME if \({n} = 1\). Assuming that \({n} = 1\), a crucial NLSE form for optical fibers hat is directly relevant to standard silica fibres and has a well-established experimental interpretation, we examine degenerated BME with Kerr law nonlinearity in this work.

Prior to this discovery, a number of previous researchers dealt with BME in different ways to get optical soliton solutions. For example, Altun et al. used Kudryashov’s approach61 to study dark, brilliant, and singular optical soliton solutions of BME with power, parabolic, and Kerr law nonlinearity. Ahmad discovered both dazzling and dark optical solitons for BME in magneto-optic waveguides based on Kudryashov’s law of refractive index64. Pinar used a pair of Kudryashov techniques to create and analyze optical solitons of BME with parabolic law and spatiotemporal dispersion65. Ozisik used the Kudryashov technique and the unified Riccati equation expansion methodology to study optical soliton events in the (2+1) and (3+1) forms of the BME66. Finally, Raza et al. concentrated the exact arrangement of the BME with Kerr law, power law, parabolic law and dual power law nonlinearity by Exp \((-\varphi (\varepsilon ))\)-expansion strategy67. They reported more exact travelling wave solutions in a brief shape to the BME condition which concedes physical centrality in applications. However, in the context of the intended model using RMESEM, the formation of Hopf bifurcation, rogue, and internal envelope solitons, as well as the elastic and inelastic collision of optical periodic solitons, have not been investigated and evaluated. This assertion highlights a notable gap in the body of current research. Our research fills this gap by offering a thorough model analysis and outlining the suggested RMESEM approach. The suggested anstaz RMESEM builds NODE and constraint relations for the model’s Kerr law nonlinearity form using a complex structured wave transformation. The resulting NODE is expected to have a close form solution that converts it into a system of nonlinear algebraic equations via substitution in order to identify fresh plethora of optical soliton solutions. The final visualizations of the obtained optical soliton solutions in the form of 3D, contour, and 2D forms demonstrate that the model develops Hopf bifurcation, rogue and internal envelope solitons as a result of the elastic and inelastic collision of optical periodic solitons while the norms |P| of the obtained optical soliton reveal dark and bright kink structures. Using phase portraits and time-series maps, we also examine chaotic and bifurcating behavior, finding that it exists in the perturbed dynamical system and obtaining positive results that show periodicity and Hopf bifurcation. We use a generalized trigonometric function to perturb the planner system for the first time in order carry out chaotic analysis. Additionally, our findings are analyzed and linked to the soliton dynamics in the aimed model, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed method as a way to find distinct soliton phenomena in such nonlinear settings.

The remaining article is structured as follows: The applied RMESEM is introduced in Section 2, optical soliton solutions to the aimed model with the application of RMESEM are acquired and presented in Section 3. Results and graphical discussion are covered in Section 4, the chaotic and bifurcation analysis are presented in Section 5, Section 6 concludes our study while last section presents an appendix.

The working methodology of RMESEM

This section describes the RMESEM’s operational procedure to determine soliton solutions for complicated NPDEs. Consider the generic complex NPDE that is shown below27,28,29:

where A is the polynomial of P, \({P}={P}(t,x,y)\) is an unknown complex function, and the subscripts are partial derivatives of P with respect to x , y and t, respectively. The proposed RMESEM’s primary steps are as follows:

Step 1. A complex wave transformation of the form \({P}(t,x,y)=e^{ \xi i}\mathfrak {P}({\phi })\) where \(\xi =\xi (t,x,y)\) and \(\phi =\phi (t,x,y)\) are linear functions, is firstly performed. In this study, we configure the ensuing complex wave transformation61:

where \(\lambda , \mu\), and \(\omega\) are wave numbers, \(\vartheta\) is phase constant while \(\xi\) is a phase component. Equation (2) transforms into the subsequent NODE employing the wave transformation as referred above:

where B is a polynomial of \(\mathfrak {P}\) and its derivatives, and the primes are the ordinary derivatives of \(\mathfrak {P}\) with regard to \({\phi }\).

Step 2. In order to satisfy the homogeneous balance condition, Eq. (4) is sometimes integrated term by term.

Step 3. For Eq. (4), we then assume that the closed-form wave solution is written as follows:

where \({d}_\mathfrak {k} (\mathfrak {k}=0,...,\mathfrak {m}-1)\) and \({e}_j (j=0,...,\mathfrak {m})\) stand for the unidentified constants that must be found later, and \({\Pi }({\phi })\) satisfies the ensuing Riccati equation:

where \({\varpi },{\rho }\) and \({\varrho }\) are invariables.

Step 4. The balance number \(\mathfrak {m}\) given in Eq. (5) is calculated using the homogeneous balancing principle between the highest nonlinear term and the highest-order derivative term in Eq. (4).

Step 5. Equation (5) is substituted into Eq. (4), or the equation that arises from integrating Eq. (4) and combining the terms with the same powers of \({\Pi }({\phi })\) to obtain an expression in terms of \({\Pi }({\phi })\), using the value of \(\mathfrak {m}\) obtained in Step 4. An algebraic system of equations describing the parameters \({e}_j (j=0,...,\mathfrak {m})\) and \({d}_\mathfrak {k} (\mathfrak {k}=0,...,\mathfrak {m}-1)\) with other related parameters is created by comparing the coefficients on both sides of the expression.

Step 6. The algebraic system in Step 5 is solved using the algebraic program Maple to provide the values of \({e}_j (j=0,...,\mathfrak {m})\) and \({d}_\mathfrak {k} (\mathfrak {k}=0,...,\mathfrak {m}-1)\) with other relevant parameters.

Step 7. Soliton solutions to Eq. (2) are obtained by substituting the values of the parameters in Eq. (5) with the solutions of Eq. (6) displayed in Table 1.

The execution of RMESEM

In this section we employ the proposed RMESEM to construct optical soliton solutions for degenerated BME namely NLSE.

The governing equation under Kerr law nonlinearity

According to Kerr law nonlinearity, we substitute \(f(\Phi ) = \Phi\) and \(n=1\) in (1) which reduces it into the ensuing structure:

The first step in conducting this study is to apply the wave transformation given in (3) to (7). The following couple of NODEs appears from the real and imaginary parts when Eq. (7) is subjected to this wave transformation:

respectively. Since \(\mathfrak {P}(\phi )\ne 0\) and has the second derivative, thus the second part in (8) gives the following constraint condition:

With this constraint, the entire model reduced to the following governing NODE:

which has Kerr law nonlinearity under the constraint in (9). By demonstrating the homogeneous balancing principle between \(\mathfrak {P}^{3}(\phi )\) and \(\mathfrak {P}''(\phi )\), we arrive at \({\mathfrak {m}}=1\), stated in (5).

The construction of optical soliton solutions

When \({\mathfrak {m}}=1\) is entered into Eq. (5), the closed form solution for Eq. (10) is obtained as follows:

By putting (11) into (10) and collecting all terms with the same orders of \({\Pi }({\phi })\), we may create an expression in \({\Pi }({\phi })\). Setting all of the coefficients to zero simplifies the expression and yields a system of nonlinear algebraic equations. In the following three (3) distinct sets, Maple is used to solve the resultant system:

Set. 1

Set. 2

Set. 3

where \(\psi =\sqrt{-2\,{\frac{p \left( {\lambda }^{2}+{\mu }^{2} \right) }{q}}}\).

We get the following innovative families of optical soliton solutions for (7) by taking into account set 1 and applying Eqs. (11) & (3) with the corresponding solution of Eq. (6) shown in Table 1:

Family. 1.1: Considering \(\eta <0 \quad \varrho \ne 0\),

and

Family. 1.2: Considering \(\eta >0 \quad \varrho \ne 0\),

and

Family. 1.3: Considering \(\eta =0, \quad \rho \ne 0\),

Family. 1.4: Considering \(\rho =\sigma\), \(\varpi =\varsigma \sigma (\varsigma \ne 0)\) and \(\varrho =0\),

Family. 1.5: Considering \(\rho =\sigma\), \(\varrho =\varsigma \sigma (\varsigma \ne 0)\) and \(\varpi =0\),

In above solutions, \({\phi }=\lambda x+\mu y+2{p}(\lambda +\mu ) t \quad \text {and} \quad \xi =x+y+ t+\vartheta\).

We get the following innovative families of optical soliton solutions for (7) by taking into account set 2 and applying Eqs. (11) & (3) with the corresponding solution of Eq. (6) shown in Table 1:

Family. 2.1: Considering \(\eta <0 \quad \varrho \ne 0\),

and

Family. 2.2: Considering \(\eta >0 \quad \varrho \ne 0\),

and

Family. 2.3: Considering \(\eta =0, \quad \rho \ne 0\),

Family. 2.4: Considering \(\eta =0\), in case when \(\rho =\varrho =0\),

Family. 2.5: Considering \(\eta =0\), in case when \(\rho =\varpi =0\),

Family. 2.6: Considering \(\rho =\sigma\), \(\varpi =\varsigma \sigma (\varsigma \ne 0)\) and \(\varrho =0\),

Family. 2.7: Considering \(\rho =\sigma\), \(\varrho =\varsigma \sigma (\varsigma \ne 0)\) and \(\varpi =0\),

Family. 2.8: Considering \(\varpi =0\), \(\varrho \ne 0\) and \(\rho \ne 0\),

and

In above solutions, \({\phi }=\lambda x+\mu y+2{p}(\lambda +\mu ) t \quad \text {and} \quad \xi =x+y+ t+\vartheta\).

We get the following innovative families of optical soliton solutions for (7) by taking into account set 3 and applying Eqs. (11) & (3) with the corresponding solution of Eq. (6) shown in Table 1:

Family. 3.1: Considering \(\eta <0 \quad \varrho \ne 0\),

and

Family. 3.2: Considering \(\eta >0 \quad \varrho \ne 0\),

and

Family. 3.3: Considering \(\eta =0, \quad \rho \ne 0\),

Family. 3.4: Considering \(\eta =0\), in case when \(\rho =\varrho =0\),

Family. 3.5: Considering \(\eta =0\), in case when \(\rho =\varpi =0\),

Family. 3.6: Considering \(\rho =\sigma\), \(\varpi =\varsigma \sigma (\varsigma \ne 0)\) and \(\varrho =0\),

Family. 3.7: Considering \(\rho =\sigma\), \(\varrho =\varsigma \sigma (\varsigma \ne 0)\) and \(\varpi =0\),

Family. 3.8: Considering \(\varpi =0\), \(\varrho \ne 0\) and \(\rho \ne 0\),

and

In above solutions, \({\phi }=\lambda x+\mu y+2{p}(\lambda +\mu ) t \quad \text {and} \quad \xi =x+y+ t+\vartheta\).

Discussion and graphs

This section displays the various optical soliton patterns discovered in the examined degenerated form of BME called NLSE. We were able to get and examine these waveforms in 2D, contour, and 3D graphs using the RMESEM and the Maple program. When the model is transformed into a NODE using a wave transformation, solutions in exponential, hyperbolic, trigonometric, and rational form are generated. The model creates Hopf bifurcation, rogue, and internal envelope solitons as a result of the elastic and inelastic collision of optical periodic solitons, as the shown graphs demonstrate. The findings of this work are highly important to fiber optics, where an understanding of wave behavior is crucial.

Optical periodic solitons are solitons that maintain a waveform of recurrent oscillations throughout time and space. The development of optical periodic solitons is due to the balance between the dispersion p and the nonlinear effects q, n of the BME. Furthermore, we found that the nonlinearity of the Kerr law causes these optical periodic solitons to collide with each other, whereas rogue waves are created by elastic collisions (maintaining their shape after collision) and internal envelope solitons are created by inelastic interactions (energy distribution). The Hopf Bifurcation in 2D graphs is the transition from a stable point of stability to a limit cycle oscillation due to a change in a parameter. This is a hallmark of nonlinear complex systems, where energy redistribution results in persistent oscillating patterns instead of continuous soliton profiles. Hopf bifurcation states that the nonlinear dynamics of the system are changing due to a crucial balance between dispersion and nonlinearity. This bifurcation is strongly tied to the presence of higher-order nonlinear variables in the BME, which introduce dynamical feedback processes. An internal envelope soliton is produced when optical periodic solitons meet inelastically, trapping energy inside an envelope. Nonlinear interactions within a wave packet produce localized structures known as internal envelope solitons. They appear as a soliton inside a larger wave envelope. The dispersion p and the higher-level nonlinear term \(q |{P}|^{2} {P}\) help to gradually stabilize this structure. These kinds of structures are frequently seen in non-Kerr optical media and Bose-Einstein condensates. Rogue waves are large, unexpected waveforms that momentarily emerge from a train of apparently regular waves. They have amplitudes that are noticeably larger than those of the surrounding waves and are limited in both space and time. Associated with this phenomenon is modulation instability (MI), which is a characteristic of the non-Kerr law nonlinearity of the model. The emergence of rogue waves after elastic collisions suggests the nonlinear energy concentrating mechanism in BME because the BME contains a higher-level nonlinearity term \(q |{P}|^{2} {P}\), which can modulate energy distribution and cause rogue wave emergence in situations where solitons focus the energy they produce locally. Lastly, for norms |P| of the obtained optical soliton reveal dark and bright kink structures. The dark soliton has a dip while the bright is localized soliton which shows peak. These solitons show the intensities of the obtained optical solitons.

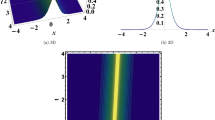

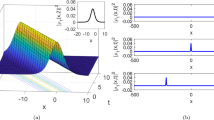

We visually depicted real, imaginary and absolutes of a set of optical solitons. Overall, the profiles of real and imaginary plots show the collision of optical periodic and other solitons while the profiles of norm |P| showed their colliding intensity. These figures have been generated by choosing particular values for the specified and constraint-related parameters that were obtained via the model and solution procedure, and by giving the free parameters random values. The dynamic behavior of the resulting soliton solutions under different parametric selections, such as the generation of envelope solitons, rogue waves, and bifurcating structures, may be observed and verified using this method. Instead of being restricted to preset parameter sets, a wider investigation of solution features is made possible by employing the application of arbitrary values inside a physically feasible range. Moreover, in Figs. 1, a. 3D, b. contour and c. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Re({P}_{1,3}(t,x,y))\), d. 3D, e. contour and f. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Im({P}_{1,3}(t,x,y))\) whereas g. 3D, h. contour and i. 2D depict the intensity profiles \(|{P}_{1,3}(t,x,y)|\) of \({P}_{1,3}(t,x,y)\) given in (17) at \(\varpi = 1, \rho = 1, \varrho = 2, \lambda = 0.0025, \mu = 0.0035, p = 0.005, \vartheta = 0.5, t = 1, e_{0} = 1\). Moreover, the Hopf bifurcations in 2D are shown for \(y=0\). Overall, the real and imaginary parts reveal the formation of internal envelope due to the inelastic collisions of optical solitons. In Fig. 2, a. 3D, b. contour and c. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Re({P}_{1,6}(t,x,y))\), d. 3D, e. contour and f. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Im({P}_{1,6}(t,x,y))\) whereas g. 3D, h. contour and i. 2D depict the intensity profiles \(|{P}_{1,6}(t,x,y)|\) of \({P}_{1,6}(t,x,y)\) given in (20) at \(\varpi = 2\), \(\rho = 5\), \(\varrho = 2\), \(\lambda = 0.005\), \(\mu = 0.001\), \(\vartheta = 1, t = 0\), \(e_{0} = 2\). Moreover, the 2D profiles are shown for \(x=1\). Overall, the real and imaginary parts reveal the elastic collisions of optical periodic solitons. In Fig. 3, a. 3D, b. contour and c. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Re({P}_{1,9}(t,x,y))\), d. 3D, e. contour and f. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Im({P}_{1,9}(t,x,y))\) whereas g. 3D, h. contour and i. 2D depict the intensity profiles \(|{P}_{1,9}(t,x,y)|\) of \({P}_{1,9}(t,x,y)\) given in (23) at \(\varpi = 5, \rho = 10, \varrho = 5, \lambda = 0.004, \mu = 0.0025, p = 0.15, \vartheta = 2, t = 10, e_{0} = 5\). Moreover, the 2D profiles are shown for \(y=0\). Overall, the real and imaginary parts reveal the formation of internal envelope due to the inelastic collisions of optical solitons. In Fig. 4, a. 3D, b. contour and c. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Re({P}_{2,5}(t,x,y))\), d. 3D, e. contour and f. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Im({P}_{2,5}(t,x,y))\) whereas g. 3D, h. contour and i. 2D depict the intensity profiles \(|{P}_{2,5}(t,x,y)|\) of \({P}_{2,5}(t,x,y)\) given in (30) at \(\varpi = 4, \rho = 5, \varrho = 1, \lambda = 0.001, \mu = 0.002, p = 0.075, \vartheta = 1, t = 10, e_{1} = 2\). Moreover, the Hopf bifurcations in 2D are shown for \(y=0\). Overall, the real and imaginary parts reveal the elastic collisions of optical periodic solitons. In Fig. 5, a. 3D, b. contour and c. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Re({P}_{2,8}(t,x,y))\), d. 3D, e. contour and f. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Im({P}_{2,8}(t,x,y))\) whereas g. 3D, h. contour and i. 2D depict the intensity profiles \(|{P}_{2,8}(t,x,y)|\) of \({P}_{2,8}(t,x,y)\) given in (33) at \(\varpi = 8, \rho = 10, \varrho = 2, \lambda = 0.035, \mu = 0.065, p = 0.015, \vartheta = 5, t = 20, e_{1} = 5\). Moreover, the 2D dynamics are shown for \(x=1\). Overall, the real and imaginary parts reveal the formation of internal envelope due to the elastic collisions of optical periodic solitons. In Fig. 6, a. 3D, b. contour and c. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Re({P}_{2,12}(t,x,y))\), d. 3D, e. contour and f. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Im({P}_{2,12}(t,x,y))\) whereas g. 3D, h. contour and i. 2D depict the intensity profiles \(|{P}_{2,12}(t,x,y)|\) of \({P}_{2,12}(t,x,y)\) given in (37) at \(\varsigma = 2, \sigma = 5, \varpi = \varsigma \sigma , \rho = \sigma , \varrho = 0, \lambda = 0.0025, \mu = 0.0015, p = 0.935, \vartheta = 1, t = 50, e_{1} = 1\). Moreover, the 2D profiles are shown for \(y=1\). Overall, the real and imaginary parts reveal the elastic collisions of optical periodic solitons. In Fig. 7, a. 3D, b. contour and c. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Re({P}_{3,4}(t,x,y))\), d. 3D, e. contour and f. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Im({P}_{3,4}(t,x,y))\) whereas g. 3D, h. contour and i. 2D depict the intensity profiles \(|{P}_{3,4}(t,x,y)|\) of \({P}_{3,4}(t,x,y)\) given in (44) at \(\varpi = 2\), \(\rho = 2\), \(\varrho = 1\), \(\lambda = 0.0065\), \(\vartheta = 5\), \(t = 100\), \(d_{0} = 2\), \(e_{0} = 1\), \(p = 0.005\), \(q = 1\), \(\mu = 0.002\). Moreover, the Hopf bifurcations in 2D are shown for \(y=0.5\). Overall, the real and imaginary parts reveal the inelastic collisions of optical periodic solitons. In Fig. 8, a. 3D, b. contour and c. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Re({P}_{3,6}(t,x,y))\), d. 3D, e. contour and f. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Im({P}_{3,6}(t,x,y))\) whereas g. 3D, h. contour and i. 2D depict the intensity profiles \(|{P}_{3,6}(t,x,y)|\) of \({P}_{3,6}(t,x,y)\) given in (46) at \(\varpi = 5, \rho = 6, \varrho = 1, \lambda = 0.00775, p = 0.0155, \vartheta = 10, t = 5, \mu = 0.001, q = 1\). Moreover, the Hopf bifurcations in 2D are shown for \(y=1\). Overall, the real and imaginary parts reveal the formation of rogue wave due to the elastic collisions of optical periodic solitons. Finally in Fig. 9, a. 3D, b. contour and c. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Re({P}_{3,15}(t,x,y))\), d. 3D, e. contour and f. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Im({P}_{3,15}(t,x,y))\) whereas g. 3D, h. contour and i. 2D depict the intensity profiles \(|{P}_{3,15}(t,x,y)|\) of \({P}_{3,15}(t,x,y)\) given in (55) at \(\varpi = 0, \rho = 10, \varrho = 1, \lambda = 0.0085, p = 0.0025, \vartheta = 5, t = 10, q = 2, \mu = 0.002, s_2 = 1\). Moreover, the Hopf bifurcations in 2D are shown for \(y=5\). Overall, the real and imaginary parts reveal the formation of rogue wave due to the elastic collisions of optical periodic solitons.

In this figure, a. 3D, b. contour and c. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Re({P}_{1,3}(t,x,y))\), d. 3D, e. contour and f. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Im({P}_{1,3}(t,x,y))\) whereas g. 3D, h. contour and i. 2D depict the bright shaped intensity profiles \(|{P}_{1,3}(t,x,y)|\) of \({P}_{1,3}(t,x,y)\) given in (17) at \(\varpi = 1, \rho = 1, \varrho = 2, \lambda = 0.0025, \mu = 0.0035, p = 0.005, \vartheta = 0.5, t = 1, e_{0} = 1\). Moreover, the 2D plots are shown for \(y=0\).

In this figure, a. 3D, b. contour and c. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Re({P}_{1,6}(t,x,y))\), d. 3D, e. contour and f. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Im({P}_{1,6}(t,x,y))\) whereas g. 3D, h. contour and i. 2D depict the singular dark-bright shaped intensity profiles \(|{P}_{1,6}(t,x,y)|\) of \({P}_{1,6}(t,x,y)\) given in (20) at \(\varpi = 2, \rho = 5, \varrho = 2, \lambda = 0.005, \mu = 0.001, p = 0.002, \vartheta = 1, t = 0, e_{0} = 2\). Moreover, the 2D profiles are shown for \(x=1\).

In this figure, a. 3D, b. contour and c. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Re({P}_{1,9}(t,x,y))\), d. 3D, e. contour and f. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Im({P}_{1,9}(t,x,y))\) whereas g. 3D, h. contour and i. 2D depict the bright shaped intensity profiles \(|{P}_{1,9}(t,x,y)|\) of \({P}_{1,9}(t,x,y)\) given in (23) at \(\varpi = 5, \rho = 10, \varrho = 5, \lambda = 0.004, \mu = 0.0025, p = 0.15, \vartheta = 2, t = 10, e_{0} = 5\). Moreover, the 2D profiles are shown for \(y=0\).

In this figure, a. 3D, b. contour and c. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Re({P}_{2,5}(t,x,y))\), d. 3D, e. contour and f. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Im({P}_{2,5}(t,x,y))\) whereas g. 3D, h. contour and i. 2D depict the dark v-shaped intensity profiles \(|{P}_{2,5}(t,x,y)|\) of \({P}_{2,5}(t,x,y)\) given in (30) at \(\varpi = 4, \rho = 5, \varrho = 1, \lambda = 0.001, \mu = 0.002, p = 0.075, \vartheta = 1, t = 10, e_{1} = 2\). Moreover, the Hopf bifurcations in 2D are shown for \(y=0\).

In this figure, a. 3D, b. contour and c. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Re({P}_{2,8}(t,x,y))\), d. 3D, e. contour and f. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Im({P}_{2,8}(t,x,y))\) whereas g. 3D, h. contour and i. 2D depict the bright shaped intensity profiles \(|{P}_{2,8}(t,x,y)|\) of \({P}_{2,8}(t,x,y)\) given in (33) at \(\varpi = 8, \rho = 10, \varrho = 2, \lambda = 0.035, \mu = 0.065, p = 0.015, \vartheta = 5, t = 20, e_{1} = 5\). Moreover, the 2D dynamics are shown for \(x=1\).

In this figure, a. 3D, b. contour and c. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Re({P}_{2,12}(t,x,y))\), d. 3D, e. contour and f. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Im({P}_{2,12}(t,x,y))\) whereas g. 3D, h. contour and i. 2D depict the dark-bright shaped intensity profiles \(|{P}_{2,12}(t,x,y)|\) of \({P}_{2,12}(t,x,y)\) given in (37) at \(\varsigma = 2, \sigma = 5, \varpi = \varsigma \sigma , \rho = \sigma , \varrho = 0, \lambda = 0.0025, \mu = 0.0015, p = 0.935, \vartheta = 1, t = 50, e_{1} = 1\). Moreover, the 2D profiles are shown for \(y=1\).

In this figure, a. 3D, b. contour and c. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Re({P}_{3,4}(t,x,y))\), d. 3D, e. contour and f. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Im({P}_{3,4}(t,x,y))\) whereas g. 3D, h. contour and i. 2D depict the dark shaped intensity profiles \(|{P}_{3,4}(t,x,y)|\) of \({P}_{3,4}(t,x,y)\) given in (44) at \(\varpi = 2, \rho = 2, \varrho = 1, \lambda = 0.0065, \vartheta = 5, t = 100, d_{0} = 2, e_{0} = 1, p = 0.005, q = 1, \mu = 0.002\). Moreover, the Hopf bifurcations in 2D are shown for \(y=0.5\).

In this figure, a. 3D, b. contour and c. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Re({P}_{3,6}(t,x,y))\), d. 3D, e. contour and f. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Im({P}_{3,6}(t,x,y))\) whereas g. 3D, h. contour and i. 2D depict the kink shaped intensity profiles \(|{P}_{3,6}(t,x,y)|\) of \({P}_{3,6}(t,x,y)\) given in (46) at \(\varpi = 5, \rho = 6, \varrho = 1, \lambda = 0.00775, p = 0.0155, \vartheta = 10, t = 5, \mu = 0.001, q = 1\). Moreover, the Hopf bifurcations in 2D are shown for \(y=1\).

In this figure, a. 3D, b. contour and c. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Re({P}_{3,15}(t,x,y))\), d. 3D, e. contour and f. 2D depict the dynamics of \(Im({P}_{3,15}(t,x,y))\) whereas g. 3D, h. contour and i. 2D depict the kink shaped intensity profiles \(|{P}_{3,15}(t,x,y)|\) of \({P}_{3,15}(t,x,y)\) given in (55) at \(\varpi = 0, \rho = 10, \varrho = 1, \lambda = 0.0085, p = 0.0025, \vartheta = 5, t = 10, q = 2, \mu = 0.002, s_2 = 1\). Moreover, the Hopf bifurcations in 2D are shown for \(y=5\).

Phase portraits and chaotic analysis of the governing system

In order to illustrate the chaotic and periodic analysis of the dynamical system, this portion presents phase portraits utilizing bifurcation analysis and time-series analysis.

Phase portraits and hopf bifurcation analysis

We study the emergent dynamical system of the model using the notions of bifurcation theory. The planar dynamical system of Eq. (10) is shown as follows:

while, the perturbed dynamical system that is obtained from planner system (56) perturbed with generalized sine function \(\sin _m(\delta \phi )\)37 is expressed as follows:

where degree and frequency of the applied external force are represented by the parameters \(l_0\) and \(\delta\), respectively. Moreover, in above systems

The planner system exhibits the following Hamiltonian under a specific integral:

For (56), we study the bifurcations of phase portraits in the parameterized space represented by \(K_1\) and \(K_2\) in the presence of the Hamiltonian constant. The dynamical system analysis along the Z-axis identifies three equilibrium points: \((M_0, 0)\), \((M_1, 0)\), and \((M_2, 0)\), where \(M_1\) and \(M_2\) are stated as:

Additionally, based on the Jacobian matrix:

The system’s Jacobian is:

At an equilibrium point \((M_i,0)\), the eigenvalues \(\lambda\) satisfy:

which governs the type of equilibrium (center, saddle etc.). Since the linearized dynamics dominate near an equilibrium, thus we discuss the Lyapunov exponents analytically at all equilibria from the eigenvalues of Jacobian matrix represented by (63) as:

-

If \(K_1- 3K_2Z_i^2<0\), eigenvalues are purely imaginary implies both exponents are zero (i.e. neutrally stable periodic orbit) and the equilibrium point is center.

-

If \(K_1- 3K_2Z_i^2>0\), eigenvalues are real implies Lyapunov exponents are those real parts i.e. \(\lambda _1= -\sqrt{ K_1- 3K_2Z_i^2}\) and \(\lambda _2= \sqrt{ K_1- 3K_2Z_i^2}\) and the equilibrium point is saddle.

-

If \(K_1- 3K_2Z_i^2=0\), we get degenerated equilibrium which needs higher dimension analysis.

We now evaluate the Hopf bifurcation at all equilibria using the eigenvalues of the Jacobean matrix.

1. At \((M_0,0)\): At (0, 0), (63) yields:

Thus we conclude:

-

If \(K_1<0\) then the eigenvalue is pure imaginary \(\rightarrow \quad (0,0)\) is the centre which implies possibility of a Hopf bifurcation candidate.

-

If \(K_1>0\) then the eigenvalues are real of opposite signs \(\rightarrow \quad (M_0,0)\) is the saddle and implies instability.

As Hopf bifurcation occurs when the real part of a pair of complex conjugate eigenvalues crosses zero, thus, we conclude that when we increase \(K_1\) through zero, the real part changes from imaginary to real which implies a Hopf bifurcation may occur at \(K_1=0\) (with \(K_2>0\) to ensure bounded cubic nonlinearity).

2. Non-zero Equilibria \((M_i,0), \ \ i=1,2\): At these equilibria, eigenvalues satisfy:

Thus we conclude:

-

If \(K_1>0\) then the eigenvalue is pure imaginary \(\rightarrow \quad (M_i,0)\) is the centre which implies possibility of a Hopf bifurcation candidate.

-

If \(K_1<0\) then the eigenvalues are real of opposite signs \(\rightarrow \quad (M_i,0)\) is the saddle and implies instability.

Thus, we conclude that when we decrease \(K_1\) through zero, the real part changes from imaginary to real which implies a Hopf bifurcation may occur at \(K_1=0\).

Phase portrait of (56) for \(\kappa = 1, {p} = 2, {q} = 2, \lambda = 1, \mu = 3\) with initial conditions \(Z(0)=0,W(0)=0.5\).

Remark 1

The phase portrait for (56) in Fig. 10 represents an eight-like homoclinic loop with two centers at \((M_1,0)=(\sqrt{2},0)\) and \((M_2,0)=(-\sqrt{2},0)\) and with a saddle point (0, 0). The phase portrait for (56) in Fig. 11 represents a closed loop with center at (0, 0). The phase portrait for (56) in Fig. 12 represents an eight like homoclinic loop with two centers at \((M_1,0)=(\sqrt{2},0)\) and \((M_2,0)=(-\sqrt{2},0)\) and with a saddle point (0, 0). The phase portrait for (56) in Fig. 13 represents an oval-like limit cycle with center at (0, 0). Finally, the phase portrait for (56) in Fig. 14 represents an eight-like homoclinic loop with two centers at \((M_1,0)=(\sqrt{2},0)\) and \((M_2,0)=(-\sqrt{2},0)\) and with a saddle point (0, 0). The system seems to be acting periodically based on the closed loops and limit cycles centered at the equilibrium point (0, 0) in the phase portrait of (56) in Figs. 11 and 13. This might be interpreted as a dynamic, organized development resulting from energy exchange and the interplay of several solitonic modes. Similarly, closed eight-like homoclinic orbits with centers at \((M_1,0)\) and \((M_2,0)\) in the lobes and with saddle point at (0, 0) are seen in the phase portrait of (56) in Figs. 10, 12 and 14. These phase portraits do not imply chaos as they imply periodic motion inside lobes (represented by closed orbits around each center) which are separated by the homoclinic separatrix. The existence of restricted or constrained periodic motion is indicated by closed loops in the phase portraits. This indicates the presence of persistent soliton cycles, which means that the energy of waves is caught in a repeated motion without dissipating, rather than decaying or growing forever. Instead, the system shifts in a predictable manner. Nonlinear Hamiltonian systems, that preserve energy over time, often exhibit this behavior.

Chaotic analysis

Throughout this investigation, we have used (57) to examine the chaotic dynamics in the governing system. Using the Gillion transformation, we apply a perturbation term to the planar dynamical system created by converting (10) in order to disrupt the system’s periodic motion and get useful findings of chaotic behavior. To understand this phenomena, a number of techniques from the corpus of current research are employed, including the Lyapunov exponent, time series, Poincaré map, and phase portrait approaches, to show that the model underlying the perturbed dynamical system exhibits chaotic or periodic behavior. The presence of chaotic/periodic dynamics in the perturbed nonlinear system is shown by time-series maps presented by Figs. 15, 16, 17, 18,19 with different initial conditions and with additional suitable parameter values.

The a. fractal-periodic and b. periodic patterns in perturbed system (57) for \(\kappa = 1, {p} = 2, {q} = 2, \lambda = 1, \mu = 3, l_0 = 2, \delta = 2 \pi , m=3\) with initial conditions \(Z(0)=0,W(0)=0.5\).

The a. quasi-periodic and b. quasi-periodic patterns in perturbed system (57) for \(\kappa = -5, {p} = 1, {q} = 1, \lambda = 5, \mu = 1, l_0 = 5, \delta = \pi , m=2\) with initial conditions \(Z(0)=0.1,W(0)=0.1\).

The a. quasi-periodic and b. periodic patterns in perturbed system (57) for \(\kappa = 1, p = 1, q = 1, \lambda = 1, \mu = 0, l_0 = 0, \delta = \pi , m=4\) with initial conditions \(Z(0)=0.1,W(0)=0\).

The a. quasi-periodic and b. quasi-periodic patterns in perturbed system (57) for \(\kappa = 1, p = 1, q = 1, \lambda = 1, \mu = 0, l_0 = 0, \delta = \pi , m=7\) with initial conditions \(Z(0)=1.2,W(0)=0\).

The a. quasi-periodic and b. periodic patterns in perturbed system (57) for \(\kappa = 1, p = 1, q = 1, \lambda = 1, \mu = 0, l_0 = 0, \delta = \pi , m=10\) with initial conditions \(Z(0)=0,W(0)=1\).

Remark 2

The periodic, quasi-periodic and fractal-periodic oscillations in the time-series plots represented by Figs. 15, 19 for different parameters values and initial conditions are probably due to the complex temporal and spatial growth of the produced periodic solitons. The periodicity of the curve may represent this underlying structure, as periodic solitons show oscillating behavior in both space and time. In Hamiltonian analysis, periodic oscillations show that, despite the system’s complexity and nonlinearity, it exhibits predictable, recurring patterns as opposed to completely chaotic behavior. The quasi-periodic and fractal-periodic cycles in Hamiltonian analysis on the other hand, indicate that the framework is in a state of transition between chaos and order. however, based on the overall time-series plots, the overall system of (57) is periodic but possesses weak chaoticness as revealed by fractal structures.

Conclusion

To summarize, the objective of this work was to investigate optical soliton phenomena in a (2+1)-dimensional Schrödinger class nonlinear model that degenerates from BME, which has particular significance in the fiber optics field. By using a complex structured wave transformation, the proposed anstaz namely RMESEM developed NODE and constraint relations for Kerr law nonlinearity form of the model. The resulting NODE was expected to have a close form solution that converted it into a system of nonlinear algebraic equations via substitution in order to identify fresh plethora of optical soliton solutions. The final visualizations of the obtained optical soliton solutions in the form of 3D, contour, and 2D forms demonstrated that the model develops Hopf bifurcation, rogue and internal envelope solitons as a result of the elastic and inelastic collision of optical periodic solitons while the norms |P| of the obtained optical soliton revealed dark and bright kink structures. Additionally, using phase portraits and time-series maps, we examined bifurcating and chaotic behavior, noting its existence in the dynamical system that was disrupted and obtained positive results that indicated periodicity and Hopf bifurcation. We used a generalized trigonometric function to perturb the planner system for the first time in order carry out chaotic analysis. Additionally, our findings were examined and connected to the soliton dynamics in NLSE, proving that the proposed approach is a successful way to find new soliton phenomena in these nonlinear settings. It should be highlighted, nonetheless, that the suggested approach fails if the largest nonlinear component and the greatest derivative terms do not balance homogeneously. In this case, the technique is unable to balance the nonlinear term with dispersion, which prevents the generation of solitons. Notwithstanding this limitation, the present investigation demonstrates that the methodology employed in this work is highly dependable and successful for nonlinear problems across a range of scientific domains. Finally, the current study aims to carry out a more thorough examination of the stability analysis of solitons in both integer and fractional orders within the parameters of the proposed model in the future.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sano, O. Partial Differential Equations (World Scientific, 2023).

Liu, P. & Lou, S. Applications of symmetries to nonlinear partial differential equations. Symmetry 2024(16), 1591 (2024).

Alibrahim, B., Habib, A. & Habib, M. Developing a brain inspired multilobar neural networks architecture for rapidly and accurately estimating concrete compressive strength. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 1989 (2025).

Fendzi-Donfack, E. & Kenfack-Jiotsa, A. Extended Fan’s sub-ODE technique and its application to a fractional nonlinear coupled network including multicomponents–LC blocks. Chaos, Solitons Fractals 177, 114266 (2023).

Fendzi-Donfack, E. et al. Nuclei discovered new practical insights via optimized soliton-like pulse analysis in a space fractional-time beta-derivatives equations. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 8440 (2025).

Donfack, E. F., Nguenang, J. P. & Nana, L. On the traveling waves in nonlinear electrical transmission lines with intrinsic fractional-order using discrete tanh method. Chaos, Solitons Fractals 131, 109486 (2020).

Fendzi-Donfack, E., Nguenang, J. P. & Nana, L. On the soliton solutions for an intrinsic fractional discrete nonlinear electrical transmission line. Nonlinear Dyn. 104, 691–704 (2021).

Fendzi-Donfack, E., Baduidana, M., Fotsa-Ngaffo, F. & Kenfack-Jiotsa, A. Construction of abundant solitons in a coupled nonlinear pendulum lattice through two discrete distinct techniques. Results Phys. 52, 106783 (2023).

Khalique, C. M. & Biswas, A. A Lie symmetry approach to nonlinear Schrodinger’s equation with non-Kerr law nonlinearity. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 14(12), 4033–4040 (2009).

He, J. H. & Wu, X. H. Exp-function method for nonlinear wave equations. Chaos, Solitons Fractals 30(3), 700–708 (2006).

Zhang, J. L., Wang, M. L., Wang, Y. M. & Fang, Z. D. The improved F-expansion method and its applications. Phys. Lett. A 350(1–2), 103–109 (2006).

Ryabov, P. N., Sinelshchikov, D. I. & Kochanov, M. B. Application of the Kudryashov method for finding exact solutions of the high order nonlinear evolution equations. Appl. Math. Comput. 218(7), 3965–3972 (2011).

Ekici, M. et al. Optical solitons with anti-cubic nonlinearity by extended trial equation method. Optik 136, 368–373 (2017).

Fan, E. Extended tanh-function method and its applications to nonlinear equations. Phys. Lett. A 277(4–5), 212–218 (2000).

Abdou, M. A. & Abulwafa, E. M. The three-wave method and its applications. Nonlinear Sci. Lett. A 1(4), 373–378 (2010).

Zayed, E. M. E. & Al-Nowehy, A. G. The Modified Simple Equation Method, the Exp-Function Method, and the Method of Soliton Ansatz for Solving the Long-Short Wave Resonance Equations. Z. Naturforschung A 71(2), 103–112 (2016).

Yokus, A. & Isah, M. A. Dynamical behaviors of different wave structures to the Korteweg-de Vries equation with the Hirota bilinear technique. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. Appl. 622, 128819 (2023).

Sasaki, Y. An objective analysis based on the variational method. J. Meteorol. Soc. Japan. Ser. II 36(3), 77–88 (1958).

Younis, M. A new approach for the exact solutions of nonlinear equations of fractional order via modified simple equation method. Appl. Math. 5(13), 1927–1932 (2014).

Feng, Z. The first-integral method to study the Burgers–Korteweg–de Vries equation. J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 35(2), 343 (2002).

Wazwaz, A. M. A sine-cosine method for handling nonlinear wave equations. Math. Comput. Model. 40, 499–508 (2004).

Sirisubtawee, S., Koonprasert, S. & Sungnul, S. New exact solutions of the conformable space-time Sharma–Tasso–Olver equation using two reliable methods. Symmetry 12(4), 644 (2020).

Albosaily, S., Mohammed, W. W., Aiyashi, M. A. & Abdelrahman, M. A. Exact solutions of the (2+ 1)-dimensional stochastic chiral nonlinear Schrödinger equation. Symmetry 12(11), 1874 (2020).

Eslami, M., Rezazadeh, H., Rezazadeh, M. & Mosavi, S. S. Exact solutions to the space-time fractional Schrödinger–Hirota equation and the space-time modified KDV-Zakharov–Kuznetsov equation. Opt. Quantum Electron. 49, 1–15 (2017).

Raza, N. & Zubair, A. Bright, dark and dark-singular soliton solutions of nonlinear Schrödinger’s equation with spatio-temporal dispersion. J. Modern Opt. 65(17), 1975–1982 (2018).

Ali, R. et al. The analytical study of soliton dynamics in fractional coupled Higgs system using the generalized Khater method. Opt. Quantum Electron. 56, 1067 (2024).

Xiao, Y., Barak, S., Hleili, M. & Shah, K. Exploring the dynamical behaviour of optical solitons in integrable Kairat-II and Kairat-X equations. Phys. Scr. 99(9), 095261 (2024).

Yan, Z., Li, J., Barak, S., Haque, S. & Mlaiki, N. Delving into quasi-periodic type optical solitons in fully nonlinear complex structured perturbed Gerdjikov–Ivanov equation. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 8818 (2025).

Al-Sawalha, M. M., Noor, S., Alqudah, M., Aldhabani, M. S. & Shah, R. Formation of Optical Fractals by Chaotic Solitons in Coupled Nonlinear Helmholtz Equations. Fractal Fract. 8(10), 594 (2024).

Ali, R. & Tag Eldin, Sayed M. A comparative analysis of generalized and extended (G’/G)-expansion methods for travelling wave solutions of fractional Maccaris system with complex structure. Alex. Eng. J. 79, 508–530 (2023).

Khan, H., Baleanu, D., Kumam, P. & Al-Zaidy, J. F. Families of travelling waves solutions for fractional-order extended shallow water wave equations, using an innovative analytical method. IEEE Access 7, 107523–107532 (2019).

Khan, H., Barak, S., Kumam, P. & Arif, M. Analytical solutions of fractional Klein-Gordon and gas dynamics equations, via the (G’/G)-expansion method. Symmetry 11(4), 566 (2019).

Wazwaz, A. M. The tanh-coth method for solitons and kink solutions for nonlinear parabolic equations. Appl. Math. Comput. 188(2), 1467–1475 (2007).

Ali, R., Alam, M. M. & Barak, S. Exploring chaotic behavior of optical solitons in complex structured Conformable Perturbed Radhakrishnan-Kundu-Lakshmanan Model. Phys. Scr. 99(9), 095209 (2024).

Ali, R., Kumar, D., Akgul, A. & Altalbe, A. On the periodic soliton solutions for fractional Schrödinger equations. Fractals 32(07n08), 2440033 (2024).

Ali, R. et al. Exploring propagating soliton solutions for the fractional Kudryashov–Sinelshchikov equation in a mixture of liquid–gas bubbles under the consideration of heat transfer and viscosity. Fractal Fract. 7, 773 (2023).

Bilal, M., Iqbal, J., Ali, R., Awwad, F. A. & Ismail, E. A. A. Exploring families of solitary wave solutions for the fractional coupled Higgs system using modified extended direct algebraic method. Fractal Fract. 7(9), 653 (2023).

Alhejaili, W. et al. Unearthing the existence of intermode soliton-like solutions within integrable quintic Kundu–Eckhaus equation. Rend. Lincei. Sci. Fisiche Nat. 36(1), 233–255 (2025).

Noor, S., Alshehry, A. S., Shafee, A. & Shah, R. Families of propagating soliton solutions for (3+ 1)-fractional Wazwaz–BenjaminBona–Mahony equation through a novel modification of modified extended direct algebraic method. Phys. Scr. 99(4), 045230 (2024).

Ganie, A. H., Yasmin, H., Alderremy, A. A., Shah, R. & Aly, S. An efficient semi-analytical techniques for the fractional-order system of Drinfeld–Sokolov–Wilson equation. Phys. Scr. 99(1), 015253 (2024).

Noor, S., Alyousef, H. A., Shafee, A., Shah, R. & El-Tantawy, S. A. A novel analytical technique for analyzing the (3+ 1)-dimensional fractional Calogero–Bogoyavlenskii–Schiff equation: investigating solitary/shock waves and many others physical phenomena. Phys. Scr. 99(6), 065257 (2024).

Alam, N., Ma, W. X., Ullah, M. S., Seadawy, A. R. & Akter, M. Exploration of soliton structures in the Hirota–Maccari system with stability analysis. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 39(11), 2450481 (2025).

Ganie, A. H., Rahaman, M. S., Aladsani, F. A. & Ullah, M. S. Bifurcation, chaos, and soliton analysis of the Manakov equation. Nonlinear Dyn. 113(9), 9807–21 (2025).

Mostafa, M. & Ullah, M. S. Soliton outcomes and dynamical properties of the fractional Phi-4 equation. AIP Adv. 15(1), 015105 (2025).

Ullah, M. S., Ali, M. Z. & Roshid, H. O. Stability analysis, model expansion method, and diverse chaos-detecting tools for the DSKP model. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 13658 (2025).

Rahaman, M. S., Islam, M. N. & Ullah, M. S. Bifurcation, chaos, modulation instability, and soliton analysis of the Schrödinger equation with cubic nonlinearity. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 11689 (2025).

Usman, T., Hossain, I., Ullah, M. S. & Hasan, M. M. Soliton, multistability, and chaotic dynamics of the higher-order nonlinear Schrödinger equation. Chaos Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 35(4), 043141 (2025).

Kivshar, Y. S. & Luther-Davies, B. Dark optical solitons: physics and applications. Phys. Rep. 298(2–3), 81–197 (1998).

Biswas, A. Dispersion-managed solitons in optical fibres. J. Opt. A: Pure Appl. Opt. 4(1), 84 (2001).

Orr, B. J. & Ward, J. F. Perturbation theory of the non-linear optical polarization of an isolated system. Mol. Phys. 20(3), 513–526 (1971).

Biswas, A. Optical soliton cooling with polynomial law of nonlinear refractive index. J. Opt. 49(4), 580–583 (2020).

Segev, M. Optical spatial solitons. Opt. Quantum Electron. 30, 503–533 (1998).

Wai, P. K. A. & Menyak, C. R. Polarization mode dispersion, decorrelation, and diffusion in optical fibers with randomly varying birefringence. J. Lightw. Technol. 14(2), 148–157 (1996).

Sucu, N., Ekici, M. & Biswas, A. Stationary optical solitons with nonlinear chromatic dispersion and generalized temporal evolution by extended trial function approach. Chaos, Solitons Fract. 147, 110971 (2021).

Singh, S. & Singh, N. Nonlinear effects in optical fibers: origin, management and applications. Prog. Electromagn. Res. 73, 249–275 (2007).

Muanenda, Y., Oton, C. J. & Di Pasquale, F. Application of Raman and Brillouin scattering phenomena in distributed optical fiber sensing. Front. Phys. 7, 155 (2019).

Secer, A. Stochastic optical solitons with multiplicative white noise via Itô calculus. Optik 268, 169831 (2022).

Alahbabi, M. N., Cho, Y. T., Newson, T. P., Wait, P. C. & Hartog, A. H. Influence of modulation instability on distributed optical fiber sensors based on spontaneous Brillouin scattering. J. Opt. Soc. America B 21(6), 1156–1160 (2004).

Biswas, A. & Milovic, D. Bright and dark solitons of the generalized nonlinear Schrödingers equation. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 15(6), 1473–1484 (2010).

Manafian, J. On the complex structures of the Biswas–Milovic equation for power, parabolic and dual parabolic law nonlinearities. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 130(12), 255 (2015).

Altun, S., Ozisik, M., Secer, A. & Bayram, M. Optical solitons for Biswas–Milovic equation using the new Kudryashovs scheme. Optik 270, 170045 (2022).

Hossain, M. N., Alsharif, F., Miah, M. M. & Kanan, M. Abundant new optical soliton solutions to the Biswas–Milovic equation with sensitivity analysis for optimization. Mathematics 12(10), 1585 (2024).

Ozisik, M. Novel (2+ 1) and (3+ 1) forms of the Biswas–Milovic equation and optical soliton solutions via two efficient techniques. Optik 269, 169798 (2022).

Arnous, A. H. Optical solitons with Biswas–Milovic equation in magneto-optic waveguide having Kudryashovs law of refractive index. Optik 247, 167987 (2021).

Albayrak, P. Optical solitons of Biswas–Milovic model having spatio-temporal dispersion and parabolic law via a couple of Kudryashovs schemes. Optik 279, 170761 (2023).

Ozisik, M. Novel (2+ 1) and (3+ 1) forms of the Biswas–Milovic equation and optical soliton solutions via two efficient techniques. Optik 269, 169798 (2022).

Raza, N., Abdullah, M. & Butt, A. R. Analytical soliton solutions of Biswas–Milovic equation in Kerr and non-Kerr law media. Optik 157, 993–1002 (2018).

Navickas, Z., Marcinkevicius, R., Telksniene, I., Telksnys, T. & Ragulskis, M. Structural stability of the hepatitis C model with the proliferation of infected and uninfected hepatocytes. Math. Comput. Model. Dyn. Syst. 30(1), 51–72 (2024).

Fan, E. Extended tanh-function method and its applications to nonlinear equations. Phys. Lett. A 277(4–5), 212–218 (2000).

Zhang, J. L., Wang, M. L., Wang, Y. M. & Fang, Z. D. The improved F-expansion method and its applications. Phys. Lett. A 350(1–2), 103–109 (2006).

Khan, H., Shah, R., Gomez-Aguilar, J. F., Baleanu, D. & Kumam, P. Travelling waves solution for fractional-order biological population model. Math. Model. Nat. Phenom. 16, 32 (2021).

Funding

This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, the Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia (Grant No. KFU254223).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.A and S.N.; methodology, R.S.; software, H.Y.; validation, M.M.A.; formal analysis, S.N..; investigation, R.S.; resources, R.S.; data curation, H.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.A; writing—review and editing, R.S.; visualization, H.Y.; supervision, S.N.; project administration, H.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Numerous analytical methods are based on the Riccati equation. Since the Riccati equation has solitary solutions, these methods may be used to the study of soliton phenomena in nonlinear models68. Inspired by such applications of the Riccati hypothesis, the current study used the Riccati equation with RMESEM to produce and evaluate soliton dynamics in the NLSE degenerated from BME27. Since it produced a large number of optical soliton solutions in five families–the exponential, periodic, hyperbolic, rational and rational-hyperbolic families of solutions–this adjustment proved beneficial for the selected model. We have been able to tie the phenomena in the targeted framework to underlying theories and the solutions provided have greatly improved our understanding of soliton dynamics. Moreover, limiting our strategy’s solutions results in specific solutions for other approaches. An analogy is given in the subsection that follows:

Comparison with other analytical methods

The outcomes of our approach are comparable to those of several other analytical techniques. For example,

Axiom 1: The following arises after \({e}_1=0\) is configured in (11):

This displays the closed form solution for the F-expansion, EDAM, and tan-function methods. Consequently, our results may also provide the solutions generated by the EDAM, F-expansion approach and tan-function technique attaining \({e}_1=0\).

Axiom 2: Similarly, when \({d}_0=0\) is established in (11), the solution structure that follows:

emerged. This is the series-form solution that emerged by using the (G’/G)-expansion method in combination with the Riccati equation.

The results of our study may thus provide a wider range of solutions generated by the (G’/G)-expansion technique71, the F-expansion method70, the tan-function method69, and EDAM36.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al-sawalha, M.M., Noor, S., Shah, R. et al. Chaotic analysis, hopf bifurcation and collision of optical periodic solitons in (2+1)-dimensional degenerated Biswas–Milovic equation with Kerr law of nonlinearity. Sci Rep 15, 44322 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30009-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30009-1