Abstract

β-cyano-L-alanine (BCA) and γ-glutamyl-β-cyano-L-alanine (GBCA) are the primary antinutritional compounds in Vicia sativa, a high-protein, drought-tolerant legume. While their neurotoxicity in monogastric animals has been reported, the molecular basis remains largely unknown. In this study, we optimised a rapid in vitro assay using retinoic acid-differentiated SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells to assess BCA and GBCA toxicity, and then applied Tandem mass tags (TMT)-mass spectrometry (MS)-based quantitative proteomics to identify dysregulated proteins. BCA treatment dysregulated the proteins involved in DNA damage, translation, and oxidative stress, many of which are associated with neurodegenerative diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease, as well as various cancers. In contrast, GBCA impacted the proteins linked to mitosis, cell cycle regulation, and apoptosis pathways. Interestingly, the absence of overlapping dysregulated proteins between BCA- and GBCA-treated cells suggested that the two toxins likely induce neurotoxicity via distinct mechanisms. These findings offer new insights into the molecular and cellular alterations caused by V. sativa toxins and their implications for animal feed safety.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The world population is rapidly increasing and is expected to reach nine billion by 20501. A population of this size will require a 60% increase in agricultural capacity to supply both sufficient caloric energy and nutritious high-quality protein2. Current global protein supply is reliant on the livestock industry, where the process of husbandry has low land use efficiency and significant greenhouse gas emissions3,4. To negate these challenges, plant protein sources from chickpea (Cicer arietinum), faba bean (Vicia faba), lentil (Lens culinaris), pea (Pisum sativum) and soybean (Glycine max) that are currently utilised are being proposed to partially fulfil the ever increasing protein requirements. Such leguminous crops are highly valued in agriculture for their capacity to fix atmospheric nitrogen into bioavailable forms, reducing the need for chemical nitrogen inputs. Integrating legumes in crop rotations also limits soil erosion, suppresses weed growth and increases soil organic matter. Research has focused on enhancing the adaptability and yield of these legumes within existing agricultural systems using diverse germplasm. More recently, efforts have expanded to identifying novel legume species capable of surviving in marginal agricultural environments. One key species under investigation is V. sativa (Common Vetch), which shows great potential as a human food crop5.

Common Vetch is an under-utilised leguminous crop that has the potential to be a prominent global pulse in fringe agricultural systems6. V. sativa is recognised for its superior drought tolerance compared to other legumes7, and its seeds contain high crude protein (24–32%) and low lipid content (1.5–2.7%)8,9. Despite the recognised agronomic benefits of Common Vetch towards reducing soil erosion, suppressing weed growth and increasing soil organic matter when used as a green manure, its adoption as a human food crop has been limited due to the presence of antinutritional elements in the seed, namely the dipeptide γ-glutamyl-β-cyano-L-alanine (GBCA, 2.6%) and the free amino acid β-cyano-L-alanine (BCA, 0.9%)10. Both compounds are acutely toxic to monogastric species8, and upon addition in animal feeds cause symptoms highly associated with neurotoxicity including hyperactivity, convulsions, tremors, rigidity, prostration, and in some studies, death in rats and chicks11,12,13. The excitotoxicity mechanism through which BCA acts is not clearly understood. In animal trials, pigs, and rats experienced neurotoxicity symptoms when eating a V. sativa supplemented diet, however HPLC analysis of brain tissue indicated presence of relatively low concentrations of BCA14. Notably, analysis investigating if BCA acts through release of cyanide ions observed no inhibition of NADH dehydrogenase (complex I) or cytochrome or oxidase (complex IV) activity15. These results suggested that the observed neurotoxicity may be indirectly caused by BCA inhibiting distinct metabolic pathways16. BCA has been shown to inhibit the action of cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE), an enzyme responsible for catalysing cystathionine into cysteine that is eventually metabolised into glutathione, which acts as a sink for excess cysteine12,17. Disruption of this pathway can cause accumulation of reactive oxygen species, free radicals, and heavy metals, leading to cell necrosis and, dependent on the locale, symptoms typical of neurotoxicity. In summary, the excitotoxicity mechanism through which BCA acts remains to be elucidated.

Currently, the exact concentrations of V. sativa toxins detrimental to human health and the precise mechanisms of BCA and GCBA neurotoxicity remain unknown. High profile commentaries such as ‘a mess of red pottage’ detailing the illegal substitution of de-hulled red lentils with physiologically similar but toxic V. sativa cultivar blanche fleur18, and the fears of potential health risks, spurred rapid development of HPLC and LC-MS/MS protocols that facilitated successful identification of adulterated lentil products19,20. While these assays provide quantitative measure for GBCA and BCA levels in the seed, they give no indication about the concentrations that would affect a biological system. To address this, laborious and costly feeding trials have been conducted to determine safe dietary inclusion levels of V. sativa grain for monogastric species such as pigs, layer hens, rabbits, and broiler chickens. These studies revealed that only relatively low inclusion levels (100–300 g/kg) are considered safe21,22. One alternative to animal trials is in vitro cell assays. In vitro cell assays are commonly used for drug discovery and metabolic studies as they generate significant biologically relevant information through analytical biochemical assays, reducing the reliance on animal testing23.

In the present study, we investigated the effects of BCA and GBCA on in vitro cultured neuronal cells derived from the routinely used SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cell line. We also examined the dysregulation of proteins associated with the specific toxicity mechanisms induced by BCA or GBCA treatment using qualitative and quantitative proteomic analysis via a tandem mass tag (TMT) approach. Additionally, we developed an in vitro cell assay for rapid detection of BCA and GBCA from Vetch seed extracts.

We aimed to develop a high throughput in vitro cell assay for rapid testing of BCA and GBCA toxins from Vetch seed extracts on neuronal cells and identify neuronal pathways that are affected by these two toxins. Deployment of the rapid assay would allow expeditious detection of a zero-toxin Common Vetch accessions and facilitate development of Vetch as a new sustainable food source for both humans and animals.

Materials and methods

Seeds of V. sativa (acc. Timok, Lov-2) were procured from S&W Seed Company (Longmont, CO, USA). 100 × 17 mm or 60 × 16 mm Nunc EasYDishes and Nunc Cell-Culture treated 12 well plates and Alamar Blue Cell Viability Reagent were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). γ-glutamyl-β-cyano-L-alanine was purified as described24, with purity assayed by NMR. Diethyl ethoxymethylenemalonate (DEEMM). Acetonitrile (HPLC grade), All-trans retinoic acid (RA), human brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and β-cyano-L-alanine were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle: Nutrient Mixture F-12 (HAM) 1:1 medium (DMEM/F-12), Penicillin-Streptomycin, GlutaMAX, and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were obtained from Gibco (Waltham, MA, USA).

SH-SY5Y neuronal cell differentiation

SH-SY5Y cells (ATCC, Virginia, USA) were maintained in DMEM: F12 complete medium supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (HI-FBS) and 1% penstrep. Cells were cultured in a humidified, 5% CO2, 37 °C incubator. SH-SY5Y were differentiated into neuronal cells as described25. In brief, cells were seeded in DMEM, 10% HI-FBS and 1% penstrep for 18 h before culturing in DMEM, 10% HI-FBS and 0.1% RA (10 mM) for five days, following three days in DMEM, 0.1% BDNF. Successful differentiation of SH-SY5Y cells into neurons was confirmed by western blotting using differentiation marker neurofilament (Fig. 1b).

BCA and GBCA treatment of differentiated SH-SY5Y cells

SH-SY5Y cells were seeded at 5 × 103 cells per well in a 96-well Nunc plate and were differentiated as described above. The culture media was then replaced with 100 µL of DMEM: F12 complete medium, 0.1% BDNF, and 20–80 mM GBCA or BCA. Cells were cultured in a humidified, 5% CO2, 37 °C incubator for 48 h before cell viability was measured.

BCA and GBCA treatment for mouse primary neurons

Mouse primary neurons were isolated as previously described26 and were seeded at 2 × 106 cells in 1mL neurobasal A with 2% B27 supplement, 1% penstrep and 1% GlutaMAX (neural feed) per well, in a 12-well CoStar plate (Corning Inc, Corning, NY, USA). Cells were maintained with half media changes every three days. On the seventh day post-seeding, neurons were treated with 20–60 mM BCA or 20–80 mM GBCA in neural feed. Neurons were cultured in a humidified, 5% CO2, 37 °C incubator for 48 h before cell viability was measured.

Cell proliferation assay

To determine the cell proliferation rate, differentiated SH-SY5Y cells seeded in 96-well plates and mouse neurons cultured in 12-well plates were loaded into the live-cell imaging system IncuCyte S3 (Sartorius AG, Göttingen, Germany) and an average of four images per well, at 10× magnification, were recorded every 2 h for 48 h. The data were used to quantify the cell surface area coverage (confluence values) using the IncuCyte Confluence software (version 1.5) (Sartorius AG, Göttingen, Germany).

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was determined using Alamar Blue fluorescence assay (cat. DAL1025, Invitrogen). In brief, cells were incubated in 10% Alamar Blue in DMEM: F12 complete medium in dark at 37 °C for 12 h. Emitting fluorescence was measured at 590 nm. All data are the average of biological triplicates.

Assessment of V. sativa seed extract toxicity

V. sativa seed extract preparation

V. sativa seed extraction was performed using a modified method previously described27. V. sativa seed (Timok and Lov-2 cultivars) was ground using a coffee grinder (Breville BCG200, Alexandria, Australia). The ground seed was sifted through 200 μm nylon-mesh and 200 mg of the sifted seed flour were mixed with 1 mL of 30% ethanol at room temperature for 1 h. The supernatant was separated from the mixture by centrifugation at 11,500× g for 10 min and the pellet reextracted with 30% ethanol twice. A total of 3 mL supernatant was pooled. Seed extracts were placed into a 3 kDa molecular weight cut-off Amicon Ultra-0.5 Centrifugal Filter Unit (Millipore, Burtlington, MA, USA) and centrifuged at 11,500× g for 10 min to remove potential contaminants prior to freeze-drying. Samples were then freeze-dried using an Alpha 2–4 LD plus system (Martin Christ, Osterode am Harz, Germany) and stored at − 80 °C until further use.

Testing the effect of V. sativa seed extract on differentiated SH-SY5Y cells

Seed extract supplemented media was prepared by resuspending the freeze-dried seed extract to the original pooled volume (3 mL) using DMEM: F12 complete medium supplemented with 0.1% BDNF. The solution was filter-sterilised using 0.45 μm filter centrifuge tubes (Corning, Costar, Spin-X, Corning, NY, USA). The effect of seed extracts on the differentiated SH-SY5Y cells was tested as follows: SH-SY5Y cells were seeded at 5 × 103 cells per well in a 96-well Nunc plate and differentiated as described above. The cell culture media was then aspirated and replaced with 100 µL of the seed extract supplemented media. For a negative control, DMEM: F12 complete medium supplemented with 0.1% BDNF was used. GBCA (0–40 mM) supplemented DMEM: F12 complete medium with 0.1% BDNF was used in positive control samples. The cells were cultured in a humidified, 5% CO2, 37 °C incubator for 48 h before cell viability was measured.

Quantification of GBCA and BCA in seed extracts using HPLC-MS

The HPLC-MS system used in this study comprised a 1200 Infinity LC System (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) coupled to a 6230 time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies). Electrospray ionisation in positive ion mode was used and Agilent Mass Hunter Data Acquisition, Qualitative Analysis and Quantitative Analysis software was used for method development and data acquisition.

Briefly, the freeze-dried samples were resuspended to the original pooled volume (3 mL) using 1 M borate buffer pH 9.0. To 1 mL of the resuspended sample, 0.66 µL of DEEMM and 10 uL 25 mM L-2-aminobutyric acid (internal standard) were added and mixed. Samples were then derivatised at 50 °C for 50 min before centrifuged at 18,500× g for 30 s to pellet any large particles, if present. For each derivatised sample, 900 µL was transferred to LC-MS vials and the vials were loaded onto HPLC-MS sample loader. Samples (10 µL) were injected for separation with an InfinityLab Poroshell 120 EC-C18 column (2.1 × 150 mm, 4 μm, Agilent Technologies) protected by a 2.1 mm guard cartridge of the same material. Elution was carried out using 0.5% formic acid in MQ water (solvent A) and 0.5% formic acid in acetonitrile (solvent B) in a binary gradient; starting at 25% acetonitrile, increasing to 60% over 11 min, further increasing to 90% from 11 to 13 min which was maintained for 3 min; the initial conditions were recovered in 2 min. Column temperature and eluent flow were set at 22 °C and 0.3 mL/min, respectively.

Peak area of derivatised BCA m/z = 284.27) and GBCA (m/z = 413.38) and internal standard (m/z = 273.28) were identified using Agilent Mass Hunter Data Acquisition; Qualitative Analysis and Quantitative Analysis software. The BCA and GBCA peak area were normalised by peak area of internal standard (analyte/internal standard), before BCA and GBCA concentration in the samples were predicted using a standard curve.

Samples with known amount of BCA and GBCA (ranging from 15 to 500 µM) in 1 M borate buffer pH 9.0 were analysed by HPLC-MS and the resulted data were used to construct standard curves to predict the BCA and GBCA concentration in the seed extract samples.

LC-MS/MS analysis for proteomics

Sample preparation for TMT analysis

SH-SY5Y cells were seeded in triplicates (n = 3), at 960,000 cells per well in 30 × 100 mm Nunc dishes and differentiated as described above. The culture media was then replaced with 15 mL of DMEM: F12 complete medium supplemented with 0.1% BDNF (6 dishes as untreated control) and 50 mM GBCA (15 dishes) or 50 mM BCA (9 dishes) for 48 h. Media was aspirated and cells were washed twice with 1× PBS. 200 µL of cold Triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB) was added to each plate and cells scraped off with a cell lifter. Cells were pooled (Control, 2× dishes; GBCA, 5× dishes; BCA, 3× dishes per replicate) and transferred to 1.5 mL tubes. 50–75 µL of each sample was collected in separate tubes for protein assay. To the remaining lysed cells, 1/10 (v/v) of 10% sodium deoxycholate was added (1% final concentration). Cells were snap frozen and stored at −70 °C until TMT analyses.

All nine samples were processed for mass spectrometric analysis in the same batch using S-Traps28 as per manufacturer’s protocol (Protifi, USA). Briefly, as the volume of the samples were large and variable across the samples, the samples were dried using vacuum centrifugation, reconstituted in S-Trap Lysis buffer (50 mM TEAB, 5% SDS), sonicated for 30 s, boiled at 95 °C for 5 min, and then cooled to room temperature.

Following this, the protein concentration was determined using the Bicinchoninic Acid assay according to the manufacturer’s protocol (ThermoFisher Scientific). An equal amount of each protein sample (100 µg) was aliquoted, and volumes normalised across all the samples using lysis buffer. Protein disulphide bridges were reduced by addition of DTT (final concentration 10 mM) at 60 °C for 30 min, and the left over DTT was quenched by alkylation by addition of Iodoacetamide (IAA, final concentration 25 mM) for 30 min in dark at ambient temperature. The pH of the samples was adjusted using aqueous phosphoric acid and diluted using S-Trap binding buffer (90% aqueous methanol containing a final concentration of 100 mM TEAB, pH 7.55). The sample mixture was transferred to a labelled S-Trap column and centrifuged at 4,000× g, after which the flowthrough was discarded. The column was washed twice using S-Trap binding buffer and proteins retained on the column were digested in the presence of 125 µL trypsin solution (1:20 trypsin to protein ratio, total 5 µg total trypsin in 50 mM TEAB) for 1 h at 47 °C.

Following digestion, peptides were eluted from the column after an addition of 50 mM TEAB and centrifugation. Remaining peptides were eluted from the column using a sequential centrifugation with addition of 0.2% aqueous formic acid followed by 50% aqueous acetonitrile containing 0.2% formic acid. Peptides were dried by vacuum centrifugation and then reconstituted in 200 mM HEPES (pH 8.8). Peptide concentration was determined using the Pierce quantitative colorimetric peptide assay (ThermoFisher Scientific).

Sample TMT labelling

Equal total peptide quantities from each of 10 samples (9 samples and a pool) were used for subsequent processing. To utilize the tenth channel in the 10-plex TMT experiment, a pooled reference sample was created by combining aliquots from eight individual samples. GBCA Toxin Replicate 3 was excluded from the pool due to insufficient sample volume. Ten samples were labelled in a 10-plex TMT (ThermoFisher Scientific) label batch. TMT labelling was performed as previously described29.

Briefly, each TMT label was redissolved using anhydrous acetonitrile and individual peptide samples were labelled with one of the individual TMT labels (total of ten labels) at room temperature for 1 h. To quench the excess TMT label in the sample, 5% hydroxylamine was added to each sample, vortexed briefly and then incubated at room temperature for 15 min. Before pooling the samples, a ‘label check’ experiment was performed to ensure equal amounts of total peptide were pooled from all samples. The label check was performed by mixing small, equal aliquots of each individually labelled TMT sample and the mixed sample was vacuum dried using a vacuum centrifuge.

Samples were reconstituted in 2% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid and analysed by LC-MS/MS. A normalisation factor was obtained from the label check experiment and the original TMT-labelled peptide samples were then pooled at an equal, 1:1 ratio across all individual samples in the respective set.

Offline high pH reversed phase (HpH) fractionation of TMT labelled peptides

The TMT labelled peptides were fractionated using HpH reversed phase chromatography as described29. Briefly, the pooled peptides were desalted using a reverse-phase C18 clean-up column (Sep-pak, MA, USA) and dried in a vacuum centrifuge. The peptide mixture was resuspended in loading buffer (5 mM ammonia solution, pH 10.5), then separated into a total of 96 fractions using an Agilent 1260 HPLC system equipped with a fraction collector. Peptides were separated over a 55 min linear gradient from 3 to 30% acetonitrile in 5 mM ammonia solution (pH 10.5) at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min on a C18 reverse phase column (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Finally, the 96 fractions were concatenated into 20 individual fractions, dried by vacuum centrifugation, then reconstituted in 0.1% formic acid for LC-MS/MS analysis.

Data dependent acquisition (DDA) LC-MS/MS

HpH fractionated, TMT labelled peptides were subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis on a Q-Exactive HF-X (ThermoFisher Scientific) mass spectrometer coupled with an UltiMate 3000 system (ThermoFisher Scientific). Briefly, each peptide fraction was injected onto the peptide trap (C18 PepMap 100, 5 μm, 100 Å, 300 μm × 5 mm, ThermoFisher Scientific) and washed with loading buffer (99.9% water, 0.1% formic acid) for 10 min. The peptide trap was then switched in line with the analytical nano-LC column (in house packed, Halo-C18, 160 Å, 2.7 μm, 100 μm x 30 cm). Peptides were eluted from the trap onto the nano-LC column and peptides were separated with a linear gradient of 5% mobile phase B (99.9% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid) to 30% mobile over 110 min at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min, followed by 85% B for 8 min.

The column eluent was directed into the ionisation source of the mass spectrometer operating in positive ion mode. Peptide precursors from 350 to 1850 m/z were scanned at 60 k resolution. The 10 most intense ions in the survey scan were fragmented by HCD using a normalised collision energy of 33 with a precursor isolation width of 0.8 m/z. Only precursors with charge state + 2 to + 5 were subjected to MS/MS analysis. The MS method had a minimum signal requirement value of 3000 ions for MS2 triggering, an AGC target value of 1 × 105 for MS2 and a maximum injection time of 85 ms. MS/MS scan resolution was set at 45,000 and dynamic exclusion was set to 30s.

Protein identification and quantitation

The raw data files were processed using Proteome Discoverer (Version 2.1.0.81, ThermoFisher Scientific). Proteomics data were mapped and identified using SequestHT and Mascot against peptide sequence database for the Homo sapiens (database containing reviewed and non-reviewed proteins, downloaded from UniProt). The parameters for the data processing were as follows: Enzyme: Trypsin; Maximum missed cleavages: 2; Precursor mass tolerance: 20 ppm; Fragment mass tolerance: 0.02 Da; Dynamic modifications: Oxidation (M), Deamidated (N, Q), Glu-> PyroGlu, Gln-> Pyro- Glu, Acetyl (Protein N-Terminus), and TMT6plex (K) and TMT6plex (N-term); Static Modification: Carbamidomethyl (C); FDR and result display filters: Protein, Peptide and PSM FDR < 1%, Master proteins only. The processed quantitative data were used for the subsequent analysis.

Differential expression analysis of proteomics data

Changes in protein abundance in response to BCA and GBCA toxicity were evaluated through pairwise comparisons across all sample groups. Proteins passing log₂ ±0.5-fold change and two-tailed t-tests a p-value below 0.05 were deemed as differentially expressed. The UniProtIDs of proteins were then matched to the H. sapiens Ensembl annotations (EnsDb.Hsapiens.v86) to facilitate the identification of significantly differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) using in-house R scripts.

Gene ontology (GO) and protein interaction network analysis

GO enrichment analyses were performed using EnrichGO in clusterProfiler v4.4.4 in R against H. sapiens Gene Ontology database org.Hs.eg.db acquired from Bioconductor30,31. The p-values were corrected using Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) method, where the significance cut-off was set to adjusted p-value < 0.05. The interaction network nodes and edges of significant Molecular Function (MF) GO were generated using cnetplotJam from the multienrichJam package (https://github.com/jmw86069/multienrichjam). The interactive networks were then visualised using Cytoscape R (Rcy3) v2.16.0 and igraph v1.3.2 (https://igraph.org/r/)32. We also performed KEGG analysis by taking DEPs from each of the comparisons along with their log2 fold change using the gseKEGG function in clusterProfiler v4.4.431,33. The pathways of interest were then visualised using pathview v.142.034.

Cell cycle analysis

SH-SY5Y cells were plated on 60 mm Nunc petri dishes (4 × 106 cells in 5 mL DMEM, 10% HI-FBS, 1% penstrep per dish) and cultured for 24 h in a humidified, 5% CO2, 37 °C incubator. The next day, the media was replaced with 3 mL fresh media supplemented with water, 25 mM BCA or GBCA (three replicates per treatment) and the cells were incubated for 24 h, after which the cells were harvested and fixed in 1 mL of 70% EtOH in 1× PBS at −20 °C for at least 16 h. The EtOH was replaced with 1 mL of 1× PBS (supplemented with 0.1 µg/µL RNase and 0.001 µg/µL of DAPI), incubated for 1 h at room temperature in dark and then analysed by BD LSRFortessa™ X-20 flow cytometry and FSC, SSC and V450/50 parameters for single cell population (10,000 events) for each sample were recorded using BD FACSDiva software. Quantitative distribution of cells in different phases of cell cycle was analysed using Watson’s model available in FlowJo software v10.8.1. Statistically significant difference (α = 0.01) among the treatments was analysed using Tukey’s HSD test available in SPSS software v28.0.1.0.

Statistical analysis

All assays utilised three biological replicates and the values are represented as mean ± SEM. Cell confluence and viability data were statistically analysed using two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons. All statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software 9.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, USA). p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

BCA and GBCA dosage response of differentiated SH-SY5Y cells

Initially, we observed after 48 h of either 50 mM BCA or GBCA treatment, differentiated SH-SY5Y cells appeared shrunken and exhibited shorter dendrites, compared to negative controls (Fig. 1a). The BCA-treated cells were much smaller than the GBCA-treated cells. This indicated that BCA and GBCA might induce cell toxicity at different concentrations.

Cell viability of differentiated SH-SY5Y cells is affected by BCA or GBCA treatment. (a) Cell morphology of control, 50 mM BCA or 50 mM GBCA treated differentiated SH-SY5Y cells after 48 h. Scale bar = 200 μm. (b) Validation of SH-SY5Y neuronal differentiation using western blotting for the differentiation marker Neurofilament H. β-Actin was used as a housekeeping protein loading control. *, a non-specific or degradation product. (c) Real-time cell viability (measured by cell confluence using IncuCyte S3 system) of differentiated SH-SY5Y cells treated with different concentrations of BCA or GBCA. (d) Relative cell viability after 48 h of control, BCA or GBCA treated differentiated SH-SY5Y cells as determined by Alamar Blue assay. Data shown as mean ± SEM of three biological replicates; ** p < 0.01.

Next, we determined BCA or GBCA dosage responses of differentiated SH-SY5Y cells by treating the cells with a range of toxin concentrations for 48 h. SH-SY5Y cell differentiation was first confirmed by western blotting for Neurofilament H marker (Fig. 1b), and cell proliferation was recorded by measuring cell confluence every 2 h during the treatment period. Cell viability was measured after 48 h using an Alamar Blue assay (Fig. 1c,d). We observed an initial reduction in cell confluence after replacing the media with fresh (controls) or toxin supplemented media (time point 0). The cell confluence was stabilised after 6 h and only slightly increased throughout the treatment period in the controls (Fig. 1c).

When treating the differentiated SH-SY5Y cells at BCA concentrations ranging from 20 to 40 mM, both cell confluence and cell viability were not significantly different to that of the control. However, at 50 mM BCA the cells showed a significant (two-way ANOVA, p < 0.01) reduction in cell confluence after 38 h of treatment. At 60 mM BCA, cell confluence was significantly reduced from the start of the treatment and remained lower throughout the treatment period. At 48 h, cell confluences of the 50 mM and 60 mM BCA treatments were significantly lower (51 ± 4.7% and 42 ± 5.5%, respectively) than the control (65 ± 6.3%). As expected, cell viability analysis at 48 h using the Alamar Blue assay showed toxicity effects of BCA at 50 and 60 mM. At 50 mM BCA, cell viability was reduced by about 50% and at 60 mM BCA, cell viability was reduced by 92% compared to the control. In summary, a clear toxicity effect of BCA on differentiated SH-SY5Y cells was observed at 50 mM.

Both the cell confluence and viability of differentiated SH-SY5Y cells treated with 20 mM GBCA were not significantly different compared to the control after 48 h, despite a reduction in cell confluence for the first 6 h of the treated sample (Fig. 1c,d). When the cells were treated with either 40, 60 or 80 mM GBCA, there was a significant reduction in the cell confluence at the start of the treatment and continued to be lower than the control throughout the treatment period. After 48 h, the cell confluences were 47 ± 5.1%, 38 ± 5.0% and 29 ± 2.7% for the 40, 60 and 80 mM GBCA treatments, respectively, which were significantly (two-way ANOVA, p < 0.01) lower compared to that of the control confluence of 60 ± 6.2%. As expected, cell viability analysis at 48 h using the Alamar Blue assay showed toxicity effects of GBCA started at 40 mM. Cell viability was reduced by about 30% in the 40 mM GBCA treatment, and by about 60 and 90% in the 60 and 80 mM treatments, respectively, compared to the control. In summary, the GBCA concentration above 40 mM linearly decreased the cell confluence and viability of differentiated SH-SY5Y cells.

The levels of BCA and GBCA molar concentration causing toxic effects in animals or humans are not well defined. A maximum brain concentration of ≈0.3 mM BCA in pigs fed vetch with no symptoms or mortality14. In chicks, diets containing ≈35% GBCA/100 g of seed resulted in complete mortality, with deaths beginning to occur at around 2 mM and becoming fully lethal by 13 mM. Given this variability and limited in vivo data, selection of 50 mM BCA and GBCA concentrations for in vitro quantitative TMT proteome analysis was based on our BCA and GBCA cell confluence and viability data (LD50) from differentiated SH-SY5Y cells treated for 48 h. We aimed to strike a balance between preserving cell survival while accurately assessing the impact of these compounds on the cell proteome with a view to determine cellular and molecular responses in differentiated SH-SY5Y neurons, serving to explore mechanisms of toxicity rather than assess dietary exposure risk.

BCA and GBCA dosage response of primary mouse neurons

To test whether BCA or GBCA affects primary mouse embryonic neurons similarly to that of differentiated SH-SY5Y cells, we treated primary mouse neurons with similar BCA or GBCA concentrations and analysed the cell viability after 48 h using Alamar Blue assay (Fig. 2). Interestingly, treating the cells with BCA at concentration from 20 to 60 mM did not show any statistically significant reduction in cell viability compared to that of the control. However, we observed the GBCA toxicity effect on primary mouse neuron cells started at as low as 20 mM (1.3 ± 0.46 × 104 RFU) with a 75% reduction in cell viability compared to that of the control (5.2 ± 0.07 × 104 RFU). We observed that primary mouse neurons are less sensitive to BCA but more sensitive to GBCA (toxicity effect started at 20 mM) when compared to differentiated SH-SY5Y cells, with the GBCA toxicity effect detectable at 40 mM (Figs. 1 and 2).

Potential synergistic effects of BCA with GBCA

Both BCA and GBCA are present in V. sativa seeds and may act synergistically to induce toxicity in cells. First, we measured the BCA and GBCA concentrations in the seed extracts of varieties Timok and Lov-2 by LC-MS, and then calculated their molar ratios. Timok seeds contained 1 mM BCA and 4.2 mM GBCA and Lov-2 seeds 1.1 mM BCA and 4.2 mM GBCA, showing 1:4 ratio in the seeds of both varieties. In subsequent neural toxicity experiments using purified BCA and GBCA, we used a 1:4 BCA: GBCA ratio.

We tested the synergistic effect of different concentrations of purified BCA and GBCA (1:4 ratio) on differentiated SH-SY5Y cells recording cell confluence every 6 h for a total of 72 h of treatment. The highest concentration of 10 mM BCA/40 mM GBCA (−34 ± 10.0%, p = 0.0297) resulted in a significant decline in cell confluence 60 h of treatment compared to 10 mM BCA (13 ± 4.42%) or 40 mM GBCA alone (−21.6 ± 3.71%) (Fig. 3). Conversely lower BCA/GBCA concentration of 2.5 mM BCA/10 mM GBCA (20 ± 10.9%, p > 0.05 and 5 mM BCA/20 mM GBCA (−4.4 ± 3.08%, p > 0.05) showed no significant difference in cell confluence compared to the individual compounds alone (2.5 mM BCA (26.5 ± 9.34%), 5mM BCA (12.4 ± 3.2%), 10 mM GBCA (11 ± 2.28%), or 20 mM GBCA (2.5 ± 3.53%). No consistent synergistic relationship between BCA and GBCA at any concentration of the 1:4 ratio was observed, indicating an additive relationship between them. This suggests that any combined disruptive effects on cell confluence arise from the individual toxic effects of each compound rather than any additional interactions between them.

Real-time cell viability of differentiated SH-SY5Y cells cultured in the absence or presence of different concentrations of BCA, GBCA or combination of BCA and GBCA (1:4 BCA: GBCA). Cell viability was determined using an IncuCyte S3 system. Data shown as mean ± SEM of triplicate biological replicates.

Identification of differentially expressed proteins in BCA and GBCA treated differentiated SH-SY5Y cells

TMT quantitative proteomics was performed to identify DEPs in differentiated SH-SY5Y cells treated with GBCA or BCA. A total of 6,827 proteins were quantified across the control, BCA and GBCA treated samples (see Supplementary information online). For further analysis, a log2 fold change ratio of 0.5 and p < 0.05 was used. Among the quantified proteins, 26 were significantly upregulated and 73 downregulated in BCA-treated cells compared to control. In contrast, 76 proteins were significantly upregulated, and 86 proteins were significantly downregulated in GBCA-treated cells compared to the control (Fig. 4a,b).

Protein expression profiling using a TMT quantitative proteomics approach. (a) Unsupervised hierarchical clustering analysis of 99 differentially expressed proteins in differentiated SH-SY5Y cells treated with 50 mM BCA (left) and 162 differentially expressed proteins in cells treated with 50 mM GBCA (right) for 48 h. Colour key indicates the log2 expression level. (b) Volcano plots of log2 fold change (x-axis) against log p-value (y-axis) of all 6,827 quantified proteins. Up- and down-regulated proteins are coloured green and red, respectively.

BCA and GBCA toxicity impact different biological pathways

Following identification of significantly dysregulated proteins, we performed enrichment analysis of gene ontology (GO) functional annotation terms utilising the GO categories of cellular composition (CC), molecular function (MF), and biological process (BP). To detect significantly enriched biological functional categories, we performed GO enrichment analysis and ranked terms by enrichment score (− log10 adjusted p value < 0.05). Whereas 21 molecular function (MF), 31 cellular components (CC), and 103 biological processes (BP) GO terms for the differential expressed proteins were identified in BCA treated cells, 24 MF, 64 CC, and 194 BP GO terms were enriched in the differentially expressed proteins in GBCA treated cells. The top 10 significantly enriched MF, CC, and BP GO terms for both treatments are presented (Fig. 5a, b). DEPs showed starkly different enrichment across all GO categories between the BCA and GBCA treatments. The BCA vs. control data showed functional enrichment of processes such as rRNA binding, DNA replication and other ribosome-related terms (Fig. 5a). However, the GBCA vs. control showed enrichment of microtubule binding, tubulin binding and chromosome segregation processes (Fig. 5b).

GO enrichment analysis for the top 10 significantly enriched molecular function (MF), cellular component (CC), and biological process (BP) terms for differentiated SH-SY5Y cells treated with (a) 50 mM BCA or (b) 50 mM GBCA. The y-axis denotes the categories of GO terms. The x-axis denotes the total protein count.

We performed protein network analysis (see methods) to understand the impact of BCA and GBCA on the molecular pathways (Fig. 6). In the BCA vs. control comparison, the top eight enriched molecular functions were derived from 20 proteins; interestingly all of which were upregulated. The key enriched networks were shown to be related to helicase activity, DNA binding and ribosome. For the GBCA vs. control, 30 DEPs were linked to the top eight enriched molecular functions protein-protein interaction networks including tubulin binding, kinase activity, P-type transporter activity and exopeptidase activity.

Our KEGG pathway analysis outcomes were consistent with the annotated associations for the DEPs as observed in GO enrichment analysis. The perturbations shown in each independent pathway reflect the impact of BCA and GBCA. As expected from the set of DEPs, the KEGG pathways for both GBCA and BCA did not overlap using the over-representation analysis (ORA) approach (Supplementary Fig. 1a-d) indicating that the two compounds acted on completely different pathways. For example, the neurological pathway entry came up using BCA vs. control DEPs but not GBCA vs. control DEPs. However, we observed that a part of neurodegeneration pathway from the BCA vs. control DEPs was associated with apoptosis (Supplementary Fig. 1b), also the main affected KEGG pathway that emerged from the GBCA vs. control DEPs.

Effect of BCA and GBCA on SH-SY5Y cell cycle

GO enrichment analysis for DEPs in BCA or GBCA treated compared to untreated differentiated SH-SY5Y cells indicated that differential expression of proteins associated with different cellular processes may be contributing to the BCA- and GBCA-mediated toxicity. We specifically observed in Fig. 5b, enrichment of cell division related processes in the GBCA treated cells. To validate this observation, we parsed undifferentiated SH-SY5Y cells treated with 25 mM GBCA for 24 h using flow cytometry to investigate changes in cell cycle pattern. We also analysed 25 mM BCA treated cells to determine if this had any covert effects on the cell division.

The cell cycle analysis showed no significant change in G0-G1 cell population (65.03 ± 1.88%) in BCA treated than the untreated cells (61.87 ± 1.99%) (Fig. 7a,b). However, we observed a small but non-significant increase in number of cells in the S phase of BCA treated (31.20 ± 0.46%) than untreated (26.63 ± 0.63%) cells, and a reduced number of cells that entered G2-M phase (5.09 ± 0.41%) in BCA treated than the control (26.63 ± 0.63%) cells. In addition, the analysis suggested that GBCA treatment significantly altered the cell cycle profile as we observed a significant increase in G0-G1 cells in GBCA treated (77.63 ± 0.32%) compared to the untreated cells (61.67 ± 1.99%). Finally, we observed a decrease in the number of cells in S (23.53 ± 0.20%) and G2-M phase (4.49 ± 0.29%) in GBCA treated than the control cells (26.63 ± 0.63% and 8.53 ± 0.56%, respectively).

SH-SY5Y cells displayed cell cycle shift after 24 h treatment with BCA or GBCA. (a) Cell cycle analysis of control, BCA or GBCA treated cells using flow cytometry (a representative result from three replicates). (b) Percentage of cells at different phases of cell cycle of control, BCA or GBCA treated cells. Data shown as mean ± SEM of three biological replicates, *p-value < 0.01, ns = not significant.

Utilisation of V. sativa seed extracts for neurotoxicity assessment

We assessed the capability of the in vitro SH-SY5Y-based assay on more complex seed matrices by applying filtered and unfiltered extracts of V. sativa cultivars Lov-2 and Timok to differentiated cells for 72 h. To benchmark these against pure compound treatments, cell viability results from GBCA-treated cells are shown in Fig. 8a, whilst those from the seed extracts are shown in Fig. 8b. To ensure the concentrations of GBCA standards used in the cell viability assay reflected the seed extract samples, we quantified GBCA in V. sativa crude extracts using HPLC-MS to be 4.17 mM for Lov-2 and 4.34 mM for Timok, falling within the range of the purified GBCA standard curve. Filtration (3 kDa) of both Lov-2 (5.2 ± 0.56 × 104 nm, p = 0.0211) and Timok (6.5 ± 0.727 × 104 nm, p ≤ 0.0002) extracts before treatment caused a significant increase in cell viability compared to the unfiltered Lov-2 (2.9 ± 0.389 × 104 nm) and Timok (2.1 ± 0.245 × 104 nm) extracts. Furthermore, a comparison was undertaken between the cell viability of filtered V. sativa extracts and the cell viability standard curve established from GBCA-treated cells (y = −9.994ln(x) + 115.82, R² = 0.8356). This analysis provided the average estimated GBCA concentrations in Lov-2 (7.24 ± 1.1 mM) and Timok (5.15 ± 1.10 mM) seed extracts, which were consistent with those determined through HPLC-MS quantification.

Relative cell viability of differentiated SH-SY5Y cells treated with (a) varying concentrations of GBCA or (b) unfiltered or 3 kDa filtered seed extracts from either ground V. sativa cultivar Lov-2 or Timok. Relative cell viability was determined at 72 h after the treatment using Alamar Blue assay (fluorescence emission from live cells was measured at 590 nm). GBCA concentration in Lov-2 and Timok seed extracts were estimated 4.17 mM and 4.34 mM, respectively, using LC-MS. Data shown as mean ± SEM of three biological replicates, **p-value < 0.01.

Discussion

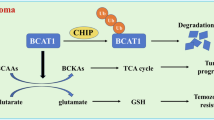

BCA and GBCA are the two most potent antinutritional compounds present in the seeds of the underutilised legume V. sativa. Animals have been shown to exhibit typical neurotoxicity symptoms when fed on V. sativa seed supplemented diets or after intravenous application of pure BCA or GBCA11,13,35,36. Evidence for the metabolic mechanisms underlying these neurotoxic affects is sparse. To investigate their mechanisms, we first developed a BCA and GBCA in vitro neurotoxicity assay using retinoic acid differentiated SH-SY5Y cells and then used this assay to determine their cellular effects by assaying the proteome of SH-SY5Y-derived neurons using TMT-based quantitative proteomics approach. Our data showed many significantly DEPs related to DNA helicase, DNA binding activity and the ribosome were impacted in BCA treated cells, whilst a significant number of DEPs related to tubulin binding, kinase activity, P-type transporter activity and exopeptidase activity were affected in the GBCA treated cells. The dysregulation of these critical cellular pathways may indicate perturbations by BCA or GBCA individually or together that have previously shown to cause neurotoxicity11,13,15,35.

BCA is a cyanide containing, non-protein amino acid whose toxicity is thought not to stem from energy depletion by the release of free cyanide15, but instead by inhibition of CSE causing accumulation of free radicals and subsequent apoptosis by oxidative stress12. Oxidative stress is commonly associated with DNA damage phenotypes37,38. In the current study, many DEPs associated with DNA damage were upregulated in BCA treated SH-SY5Y-derived neurons, which may not be solely due to BCA-mediated CSE inhibition. The mini-chromosome maintenance (MCM) family (MCM2,3,5,6,7) of proteins involved in DNA helicase activity were all significantly upregulated39. BCA-mediated oxidative stress can cause genomic instability through the action of cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) as observed in many cancers40,41,42. Single stranded DNA binding proteins such as TDP1 (responsible for DNA repair following oxidative damage)43, MSH2 (engaged in DNA mismatch repair)44, SMC4 (responsible for replication damage repair) and RFC5 (necessary for slowing of DNA synthesis when DNA is damaged during replication) were significantly upregulated45,46. The higher proportion of DEPs associated with DNA repair may indicate a failed cell cycle checkpoint response (G2/M checkpoint), an effect indicated by subtle changes to distribution of cells in different phases in the BCA treated undifferentiated SH-SY5Y cells. BCA treatment impeded cell cycle progression at the S to G2–M transition, increasing the proportion of cells in S phase. Such S phase arrest can trigger apoptosis if DNA repair fails47,48. This mechanism may contribute to, but unlikely to be the sole cause of, BCA-induced neurotoxicity, as the increase in S phase cells was not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

We also observed upregulation of several ribosomal proteins, including large subunits RPL15 and RPL18A and small subunit RPS16, in BCA-treated cells. These proteins, which support transcription, translation, and cell proliferation, are known to be upregulated during oxidative stress to maintain ribosomal integrity and protein synthesis49,50. This aligns with our GO enrichment analysis, which identified enhanced regulation of translation fidelity following BCA exposure (Fig. 5a).

In contrast to BCA, GBCA seems to disturb the cell cycle regulation of differentiated SH-SY5Y cells. Although we observed strong Neurofilament H differentiation marker expression (Fig. 1b), a small proportion of undifferentiated dividing cells may have contributed to the identification of mitosis-related DEPs in GBCA treated samples. Many DEPs were related to the maintenance of mitosis and the cell cycle as suggested by the GO and network analysis (Fig. 7). The increase in G0-G1 cell population after GBCA treatment suggests that both the cell transition between G0-G1 phase to S phase and the G2-M phase are impeded, which is consistent with the GO enrichment terms including microtubule binding, spindle organisation, condensed chromosome, chromosome segregation, and microtubule cytoskeleton organisation involved in mitosis. Specifically, nine proteins were found to be significantly upregulated, while five were significantly downregulated compared to the control (Fig. 4b), with network analysis indicating interactions along these pathways (Fig. 6). The observed dysregulation is predicted to initiate mitotic arrest and partial activation of apoptosis via p53 induction51.

Interestingly, we observed that differentiated SH-SY5Y cells were sensitive to both BCA and GBCA, however, the mouse primary embryonic neurons were sensitive to GBCA (Fig. 2). The reason for this difference is not clear, although the neurotoxicity of compounds can vary significantly between tested cell types52,53. That differences in the effect of BCA and GBCA could be due to the variation in physiological state of in vitro differentiated SH-SY5Y human cells (a proportion of which may still be cycling) vs. highly homogeneous postmitotic mouse neurons cannot be ruled out. Together, these differences in BCA and GBCA sensitivity across differing cell types should be considered when planning future animal trials for assessment of V. sativa toxicity. However, we reason that due to the lower prevalence of BCA (1 mM) compared to GBCA (4.5 mM) in the raw vetch seeds and lack of observed synergistic toxicity effects between BCA and GBCA at those same ratios upon SH-SY5Y-derived cells, it is unlikely that this would affect future testing towards V. sativa as an animal food source (see Fig. 3).

Toxins can interfere with numerous cellular pathways by directly binding to metabolites or proteins, altering their structure or function, and causing excitotoxicity, inflammation, and oxidative stress54. They may also directly or indirectly influence gene expression and gene function. Several studies have shown that toxic compounds can disrupt cell membranes, damage DNA, denature proteins, and impair cellular metabolism, ultimately leading to cell death54. While the precise mechanisms underlying the effects of BCA or GBCA on cellular structures and functions remain to be fully characterized, the observed dysregulation of proteins involved in DNA replication, DNA repair, and microtubule organisation suggests that both compounds disturb pathways essential for cellular homeostasis. Further research is required to identify the specific pathways impacted by BCA or GBCA that contribute to the observed neuronal toxicity.

Overall, our study employed TMT-based quantitative proteomics to, for the first time, use an in vitro toxicity testing model that we developed to elucidate the proteins and pathways whose dysregulation could explain the BCA- and GBCA-mediated effects in differentiated SH-SY5Y cells. Our analysis revealed that BCA primarily affected helicase activity, DNA binding, and ribosomal function, while GBCA influenced pathways related to tubulin binding, kinase activity, P-type transporter activity, and exopeptidase activity. Notably, BCA-mediated upregulation of MCM family proteins and single-stranded DNA binding proteins (TDP1, MSH2, SMC4, and RFC5) may be due to heightened oxidative stress, which is consistent with previously reported CSE inhibition and the accumulation of reactive oxygen species, ultimately triggering apoptosis. While further studies are needed to fully elucidate the mechanisms of BCA and GBCA toxicity, our identification of DEPs linked to excitotoxicity pathways and neurotoxicity symptoms is a promising step forward. The new insights will help to explain the neuronal cell death observed in monogastric animals exposed to these toxins. Moreover, the identified DEPs provide candidate biomarkers that could be used in future screening pipelines to develop zero-toxin V. sativa for safer animal and human consumption.

Data availability

The raw TMT proteome data used was deposited in PRIDE with the dataset identifier PXD067726 and are publicly accessible at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pride/. All the other data generated or analysed during this study are included in the text of this article. Code used for the proteomics data analysis are available on https://github.com/BioinfoHub-PeiQinNg/Proteomics_GBCA_analysis.

Abbreviations

- BCA:

-

β-cyano-L-alanine

- GBCA:

-

γ-glutamyl-β-cyano-L-alanine

- V. sativa :

-

Vicia sativa

- HPLC:

-

High-performance liquid chromatography

- LC-MS/MS:

-

Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry

- SH-SY5Y:

-

Human neuroblastoma cell line

- DMEM/F-12:

-

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium/nutrient mixture F-12

- FBS:

-

Fetal bovine serum

- HI-FBS:

-

Heat inactivated fetal bovine serum

- RA:

-

All-trans retinoic acid

- BDNF:

-

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- PBS:

-

Phosphate buffered saline

- TMT:

-

Tandem mass tag

- DEPs:

-

Differentially expressed proteins

References

Roberts, L. 9 Billion?. Science 333, 540–543 (2011).

FAO. The Future of Food and Agriculture, Alternative Pathways to 2050. (2018).

Alexander, P. et al. Drivers for global agricultural land use change: the nexus of diet, population, yield and bioenergy. Glob. Environ. Change. 35, 138–147 (2015).

Johnson, K. A. & Johnson, D. E. Methane emissions from cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 73, 2483–2492 (1995).

Nguyen, V., Riley, S., Nagel, S., Fisk, I. & Searle, I. R. Common vetch: A drought Tolerant, high protein neglected leguminous crop with potential as a sustainable food source. Front. Plant Sci. 11, 1–7 (2020).

F.A.O. 11 Most Important Pulses FAO. (1994).

Enopala, J. T., González, F. J. & De La Barrera, E. Physiological responses of the green manure, vicia sativa, to drought. Bot. Sci. 90, 305–311 (2012).

Valentine, S. C. & Bartsch, B. D. Production and composition of milk by dairy cows fed common Vetch or lupin grain as protein supplements to a silage and pasture-based diet in early lactation. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 36, 633–636 (1996).

Mao, Z., Fu, H., Nan, Z. & Wan, C. Fatty acid, amino acid, and mineral composition of four common Vetch seeds on Qinghai-Tibetan plateau. Food Chem. 171, 13–18 (2015).

Tate, M. E., Rathjen, J., Delaere, I. & Enneking, D. Covert trade in toxic Vetch continues. Nature 400, 207 (1999).

Ressler, C. Isolation and identification from common Vetch the neurotoxin a possible factor in neurolathyrism. J. Biol. Chem. 237, 733–736 (1962).

Pfeffer, M. & Ressler, C. β-Cyanoalanine, an inhibitor of rat liver cystathionase. Biochem. Pharmacol. 16, 2299–2308 (1967).

Ressler, C., Tatake, J. G., Kaizer, E. & Putnam, D. H. Neurotoxins in a Vetch food: stability to cooking and removal of γ-Glutamyl-β-cyanoalanine and β-Cyanoalanine and acute toxicity from common Vetch (Vicia sativa L.) legumes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 45, 189–194 (2002).

Rathjen, J. M. The Potential for Vicia Sativa L. As a Grain Legume for South Australia. (University of Adelaide, 1997).

Roy, D. N., Sabri, M. I., Kayton, R. J. & Spencer, P. S. β-cyano-L-alanine toxicity: evidence for the involvement of an excitotoxic mechanism. Nat. Toxins. 4, 247–253 (1996).

Enneking, D. The Toxicity of Vicia Species and their Utilisation as Grain Legumes. (University of Adelaide, 1994).

Lambein, F., Kuo, Y. & Ikegami, F. Kusama-eguchi, K. Grain legumes and human health. Genetics 1, 422–432 (2008).

Tate, M. E. & Enneking, D. A mess of red pottage. Nature 359, 357–358 (1992).

Ghasemi, N., Secen, H., Yılmaz, H., Binici, B. & Goren, A. C. Determination of neurotoxic agents as markers of common Vetch adulteration in lentil by LC-MS/MS. Food Chem. 221, 2005–2009 (2017).

Thavarajah, P., Thavarajah, D., Premakumara, G. A. S. & Vandenberg, A. Detection of common Vetch (Vicia sativa L.) in lentil (Lens culinaris L.) using unique chemical fingerprint markers. Food Chem. 135, 2203–2206 (2012).

Huang, Y. F., Gao, X. L., Nan, Z. B. & Zhang, Z. X. Potential value of the common Vetch (Vicia sativa L.) as an animal feedstuff: a review. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 101, 807–823 (2017).

May, J. E., Xu, J., Morse, H. R., Avent, N. D. & Donaldson, C. Toxicity testing: the search for an in vitro alternative to animal testing. Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 66, 160–165 (2009).

An, W. F. & Tolliday, N. Cell-Based assays for High-Throughput screening. Mol. Biotechnol. 45, 180–186 (2010).

Tschiersch, B. Occurrence of γ-glutamyl-β-cyanoalanine. Tetrahedron Lett. 5, 747–749 (1964).

Shipley, M. M., Mangold, C. A. & Szpara, M. L. Differentiation of the SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cell line. J. Visual. Exp. 2016, 53193 (2016).

Kaech, S. & Banker, G. Culturing hippocampal neurons. Nat. Protoc. 1, 2406–2415 (2006).

Megías, C., Cortés-Giraldo, I., Girón-Calle, J., Vioque, J. & Alaiz, M. etermination of β -Cyano-L-alanine, γ -Glutamyl- β -cyano-L-alanine, and Common Free Amino Acids in Vicia sativa (Fabaceae) Seeds by Reversed-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography. J. Analyt. Methods Chem. 2014, 1–5 (2014).

HaileMariam, M. et al. S-Trap, an ultrafast Sample-Preparation approach for shotgun proteomics. J. Proteome Res. 17, 2917–2924 (2018).

Kumar, R. et al. Endogenous protein interactomes resolved through immunoprecipitation-coupled quantitative proteomics in cell lines. STAR. Protocols. 3, 101693 (2022).

Yu, G., Wang, L. G., Han, Y. & He, Q. Y. ClusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS: J. Integr. Biology. 16, 284–287 (2012).

Wu, T. et al. ClusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innov. 2, 100141 (2021).

Gustavsen, J. A., Pai, S., Isserlin, R., Demchak, B. & Pico, A. R. RCy3: network biology using cytoscape from within R. F1000Research 8, 1774 (2019).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Matsuura, Y. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, D672–D677 (2025).

Ulgen, E., Ozisik, O. & Sezerman, O. U. PathfindR: an R package for comprehensive identification of enriched pathways in omics data through active subnetworks. Front. Genet. 10, 858 (2019).

Ressler, C., Nelson, J. & Pfeffer, M. Metabolism of beta-cyanoalanine. Biochem. Pharmacol. 16, 2309–2319 (1967).

Sadeghi, G., Tabeidian, S. A. & Toghyani, M. Effect of processing on the nutritional value of common Vetch (Vicia sativa) seed as a feed ingredient for broilers. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 20, 498–505 (2011).

Barzilai, A. & Yamamoto, K. I. DNA damage responses to oxidative stress. DNA Repair. 3, 1109–1115 (2004).

Davies, K. The broad spectrum of responses to oxidants in proliferating cells: A new paradigm for oxidative stress. IUBMB Life. 48, 41–47 (1999).

Labib, K., Tercero, J. A. & Diffley, J. F. X. Uninterrupted MCM2-7 Function Required for DNA Replication Fork Progression. Science https://doi.org/10.1126/science.288.5471.1643 (1979).

Tanaka, S., Tak, Y. S. & Araki, H. The role of CDK in the initiation step of DNA replication in eukaryotes. Cell Div. 2, 16 (2007).

Zhou, J. et al. Expression and Prognostic Value of MCM Family Genes in Osteosarcoma. Front. Mol. Biosci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2021.668402 (2021).

Das, M., Singh, S., Pradhan, S. & Narayan, G. MCM paradox: abundance of eukaryotic replicative helicases and genomic integrity. Mol. Biology Int. 2014, 1–11 (2014).

Pommier, Y. et al. Tyrosyl-DNA-phosphodiesterases (TDP1 and TDP2). DNA Repair. 19, 114–129 (2014).

Edelbrock, M. A., Kaliyaperumal, S. & Williams, K. J. Structural, molecular and cellular functions of MSH2 and MSH6 during DNA mismatch repair, damage signaling and other noncanonical activities. Mutat. Res. Fund. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 743–744, 53–66 (2013).

Wang, Y. & Wu, Z. The Clinical Significance and Transcription Regulation of a DNA Damage Repair Gene, SMC4, in Low-Grade Glioma via Integrated Bioinformatic Analysis. Front. Oncol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.761693 (2021).

Sugimoto, K., Ando, S., Shimomura, T. & Matsumoto, K. Rfc5, a replication factor C component, is required for regulation of Rad53 protein kinase in the yeast checkpoint pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 5905–5914 (1997).

Xu, Z. et al. Sophoridine induces apoptosis and S phase arrest via ROS-dependent JNK and ERK activation in human pancreatic cancer cells. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-017-0590-5 (2017).

Kruman, I. I. Why do neurons enter the cell cycle? Cell. Cycle. 3, 767–771 (2004).

Smagin, D. A. et al. Dysfunction in ribosomal gene expression in the hypothalamus and hippocampus following chronic social defeat stress in male mice as revealed by RNA-Seq. Neural Plast. 2016, 1–6 (2016).

Saha, A. et al. Genome-Wide identification and comprehensive expression profiling of ribosomal protein small subunit (RPS) genes and their comparative analysis with the large subunit (RPL) genes in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 1553 (2017).

Orth, J. D., Loewer, A., Lahav, G. & Mitchison, T. J. Prolonged mitotic arrest triggers partial activation of apoptosis, resulting in DNA damage and p53 induction. Mol. Biol. Cell. 23, 567–576 (2012).

Popova, D., Karlsson, J. & Jacobsson, S. O. P. Comparison of neurons derived from mouse P19, rat PC12 and human SH-SY5Y cells in the assessment of chemical- and toxin-induced neurotoxicity. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 18, 42 (2017).

Heusinkveld, H. J. & Westerink, R. H. S. Comparison of different in vitro cell models for the assessment of pesticide-induced dopaminergic neurotoxicity. Toxicol. In Vitro. 45, 81–88 (2017).

Lehman-McKeeman, L. D. & Armstrong, L. E. Biochemical and Molecular Basis of Toxicity. In: Haschek and Rousseaux’s Handbook of Toxicologic Pathology. 15–49 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-821044-4.00021-2 (Elsevier, 2022).

Acknowledgements

Some of the research described herein was undertaken at the Australian Proteome Analysis Facility (APAF) funded under the Australian Government’s National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy (NCRIS).

Funding

This work was supported by an Australian Research Council (ARC) grant LP200200957 awarded to I.S, J.G. and R.S., a South Australian Grains and Industry Trust (SAGIT) grant UA720 awarded to I.S., a Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) grant BB/V018108/1 awarded to IF and Research Training Program scholarships (RTPS) from the University of Adelaide awarded to S.R., R.B., and PQ.N.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.R., R.B., T.R., and R.K. generated the and analysed the results and prepared Figs. 1, 2 and 3. S.R., PQ.N. and K.K. generated and analysed the results, and prepared Figs. 4, 5 and 6. V.N. and R.K. generated and analysed the results and prepared Figs. 7 and 8. I.F., J.G., R.K., and I.S. analysed all the data. S.R., R.K. and I.S. wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Riley, S., Nguyen, V., Bhattacharjee, R. et al. TMT-based quantitative proteomic assessment of Vicia sativa induced neurotoxicity by β-cyano-L-alanine and γ-glutamyl-β-cyano-L-alanine in SH-SY5Y cells. Sci Rep 16, 510 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30121-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30121-2