Abstract

Kinesins, which are motor proteins that primarily move along microtubules by hydrolyzing adenosine triphosphate (ATP), constitute a superfamily of proteins known as kinesin superfamily proteins (KIFs). These molecules play crucial roles not only in intracellular transport but also in cell division, cell survival, morphogenesis, and higher brain functions such as memory, learning, and neural network formation. We previously reported that KIF26A plays a key role in the development of the enteric nervous system of the colon. Here, we demonstrate that KIF26A plays a role in olfaction. Analysis of Kif26a−/− mice reveals that Kif26a is critical for the development of the neuronal layer in the main olfactory epithelium (MOE). At postnatal day 7, Kif26a−/− mice exhibit decreased thickness and disorganization of the MOE with disproportionate numbers of mature and immature olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs). Loss of KIF26A leads to increased apoptosis and accelerated precursor cell proliferation of OSNs. Additionally, in vitro experiments using primary cultures of neurons reveal that KIF26A deficiency impaired neurite outgrowth and disrupted nerve bundle formation in OSNs. Furthermore, Kif26a haploinsufficiency results in impaired olfactory responses. These findings suggest that KIF26A plays important roles in both olfactory epithelium development and olfactory function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Kinesin superfamily proteins (KIFs) are involved in the ATP-dependent intracellular transport of organelles, protein complexes, and mRNAs along the microtubule network. To date, 45 mammalian KIF genes have been identified and classified into 15 subfamilies. Through their role in transporting or interacting with signal transduction molecules, KIFs regulate critical biological processes, including developmental patterning (e.g., left–right asymmetry), neuronal survival and development, ciliary function, tumorigenesis, and regulation of microtubule dynamics1,2,3. We previously reported that KIF26A, which is an atypical KIF that lacks ATPase activity, plays a critical role in the development of the enteric nervous system of the colon by interacting with the Grb2/SHC complex and negatively regulating glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF)-Ret signaling4. This signaling cascade involves the binding of GDNF to the heteromeric GDNF family receptor alpha 1 (GFRα1)-Ret receptor complex, which in turn binds to and phosphorylates SHC. Then, phosphorylated SHC activates the Ras/ERK1/2 and phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K)/Akt signaling pathways via Grb2. However, when KIF26A binds to Grb2, it prevents the interaction between Grb2 and SHC and ultimately inactivates Ras and PI3K signaling.

The GDNF-Ret signaling pathway plays important roles in the olfactory epithelium (OE) and olfactory bulb (OB). GDNF and GFRα1 are prominently expressed in the OE and OB5,6,7,8,9. Adult Gfrα1+/− mutants exhibit decreased olfactory responses in behavioral tests9. These findings suggest that KIF26A may play a key role in the differentiation and function of olfactory neurons by modulating these critical signaling pathways.

Here, we report that Kif26a is expressed in the olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs) of the main olfactory epithelium (MOE), vomeronasal organ (VNO), and OB. Additionally, the survival, proliferation, and neurite outgrowth of Kif26a−/− OSNs are impaired, which may be the cause of disorganized MOE formation and reduced olfactory responses in Kif26a+/− mice. These results suggest that KIF26A is essential for olfaction because it regulates the development of OSNs.

Results

Kif26a is expressed in the MOE, VNO, and OB

KIF26A can interact with the Grb2/SHC complex to negatively regulate the GDNF–Ret signaling pathway during the development of the enteric nervous system of the colon4. GDNF-Ret signaling plays important roles in the development and function of the OE and OB9. To investigate the role of KIF26A in the OE and OB, in situ hybridization was performed on wild-type mouse brains using Kif26a sense and antisense riboprobes. Kif26a expression was detected broadly in the OE at embryonic day (E) 14.5 (Fig. 1a–c; Supplementary Fig. S1a,b) and P0 (Fig. 1d,e; Supplementary Fig. S1c,d) and became restricted to the MOE and VNO at P7 (Fig. 1f,g; Supplementary Fig. S1e,f) and at two weeks of age (Fig. 1h,i; Supplementary Fig. S1g,h). High-magnification images clearly revealed that Kif26a was specifically expressed in the OE and was expressed at lower levels in the respiratory epithelium (RE), nasal septum (SP), and ethmoidal turbinates (ET) (Fig. 1j–m). In situ hybridization also revealed that Kif26a was broadly expressed in the OB at E14.5 (Fig. 2a–c). By P0, Kif26a was highly expressed in the mitral cell layer and the glomerular layer (Fig. 2d–f). At P7, Kif26a was expressed in the olfactory nerve layer, the glomerular layer, the external plexiform layer, the mitral cell layer, and the granule cell layers (Fig. 2g–i).

Expression of Kif26a in the developing MOE and VNO. (a) Sagittal views of the mouse nasal cavity showing the two separate olfactory systems. (b–m) In situ hybridization of the nasal cavity using Kif26a-antisense (b,d,f,h,j,l) and sense (c,e,g,i,k,m) riboprobes, showing Kif26a expression at E14.5 (b,c), P0 (d,e), and P7 (f,g) and at two weeks of age (h,i). The boxes in (h,i) represent the regions in (j,k,l,m), respectively. MOE: main olfactory epithelium; VNO: vomeronasal organ; SP: nasal septum; ET: ethmoidal turbinates; OE: olfactory epithelium; RE: respiratory epithelium. Scale bars represent 160 μm (d–k) and 40 μm (b,c,l,m).

Expression of Kif26a in the developing OB. In situ hybridization of the OB using Kif26a antisense (a,d,g) and sense (b,e,h) riboprobes, showing Kif26a expression at E14.5 (a,b), P0 (d,e) and P7 (g,h). Boxes in a, d and g show regions in c, f and i. LV: lateral ventricle; ONL: olfactory nerve layer; GL: glomerular layer; EPL: external plexiform layer; MCL: mitral cell layer; GCL: granule cell layer. Scale bars represent 40 μm (a–c,f,i) and 160 μm (d,e,g,h), respectively.

Cell types expressing Kif26a in the developing OE

The OE is a pseudostratified neuroepithelium that is composed of multiple cell types, including stem and precursor cells in the basal layer, immature and mature OSNs in the middle and upper layers, respectively, and supporting or sustentacular cells in the most apical layer10. To determine the specific cell types that express Kif26a in the wild-type background, OE sections from mice at P7 were hybridized with FITC-labeled Kif26a probes and double labeled with antibodies against GAP43 and OMP. GAP43 is a marker of developing and regenerating neurons, indicating immature OSNs. OMP is a well-established marker of mature OSNs. FITC-positive signals colocalized with OMP-positive cells in the OE (Supplementary Fig. S2g–l), whereas less colocalization was observed with GAP43-positive cells (Supplementary Fig. S2a–f). Kif26a is strongly expressed in OMP-positive mature OSNs, whereas its expression is lower in GAP43-positive immature OSNs. These results revealed differential expression of the Kif26a gene in immature and mature OSNs in the OE.

KIF26A is involved in the formation of the neuronal layer in the olfactory epithelium

To elucidate the function of KIF26A in the olfaction system, Kif26a-deficient mice were generated using the CRISPR/Cas9 system (Fig. 3a). Kif26a+/− mice were established in a C57BL/6 background, and the absence of Kif26a in Kif26a−/− mice was confirmed by genomic PCR, RT–PCR of the OB (Fig. 3b,c; Supplementary Fig. S3), and in situ hybridization of the OE in Kif26a+/+ and Kif26a−/− mice (Fig. 3d,e). Kif26a−/− mice died at approximately two weeks of age; therefore, analysis of the olfactory system was primarily conducted at P7, when the total size of the brain and the nasal cavity was smaller than that of wild-type samples (Supplementary Fig. S4a,b). Quantitative analysis revealed that the OB area in Kif26a−/- mice (3.26 ± 0.33 mm2) was significantly smaller than that in wild-type mice (4.39 ± 0.31 mm2) (Fig. S4c; p = 0.0305; two-tailed unpaired t test after confirmation of normality by the Shapiro–Wilk test). Hematoxylin–eosin staining revealed a reduction in the thickness of the neuronal layer in the MOE but not in the VNO, SP, RE, or ET of Kif26a−/− mice compared with that in wild-type mice at P7 (Fig. 4a–j). Quantitative analysis revealed that the MOE neuronal layer in Kif26a−/- mice (13.47 ± 0.29 μm) was significantly thinner than that in wild-type mice (27.50 ± 0.54 μm) (Fig. 4o; p = 0.006; two-tailed unpaired t test after confirmation of normality by the Shapiro–Wilk test). In addition, the thickness of the lamina propria (LP) was reduced in Kif26a−/- mice. In contrast, there was no significant difference in the thickness of the VNO or the olfactory nerve layer (ONL) of the OB between wild-type and Kif26a−/− mice (Fig. 4p; p = 0.615 and Fig. 4q; p = 0.1517, respectively; two-tailed unpaired t test after confirmation of normality by the Shapiro–Wilk test). To further examine the role of KIF26A in the neuronal layer of the OE, the expression of GAP43 and OMP was analyzed. Immunohistochemistry revealed disorganization of OMP-positive mature OSNs in the OE of Kif26a−/− mice compared with those in the OE of wild-type mice at P7. However, the basal localization of GAP43-positive OSNs and the apical localization of OMP-positive OSNs were generally preserved in both Kif26a−/− and wild-type mice, indicating that overall laminar organization was not lost in Kif26a−/− mice (Fig. 5a–h). Quantitative analysis revealed that the number of GAP43-positive immature OSNs was significantly lower in Kif26a−/− mice (315.8 ± 10.93 cells/field) than in wild-type mice (444.4 ± 12.33 cells/field) (Fig. 5i; p < 0.0001: two-tailed unpaired t test after confirmation of normality by the Shapiro–Wilk test), whereas the number of OMP-positive OSNs was significantly greater in Kif26a−/− mice (135 ± 7.42 cells/field) than in wild-type mice (76.30 ± 2.83 cells/field) (Fig. 5j; p < 0.0001: two-tailed unpaired t test after confirmation of normality by the Shapiro–Wilk test). No clear differences were observed in the OB between Kif26a−/− and wild-type mice (Supplementary Fig. S5). These results suggest that Kif26a deficiency specifically impairs the formation of the MOE.

Generation of Kif26a-deficient mice. (a) Kif26a−/− mice were generated by the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Exon 7 contains the p-loop ATP binding motif. The arrows represent the PCR primers (see the experimental procedures in Methods). (b–c) Representative results of PCR for genotyping (b) and RT–PCR (c) of the OB. (d–e) In situ hybridization of the OE using kif26a antisense riboprobes in wild-type (d) and kif26a−/− (e) mice at P0. Scale bars represent 160 μm.

Defective development of the neuronal layer of the MOE in Kif26a−/− mice. (a–f) HE-stained MOE sections from Kif26a−/− mice at P7 showing reduced thickness of the neuronal layer (b,d,f) compared with those from wild-type mice (a,c,e). The boxes in (a,b) represent the regions in (c,d), respectively. The boxes in (c,d) represent the regions in (e,f), respectively. (g–j) HE-stained sections of the VNO from wild-type (g) and Kif26a−/− mice (h) at P7. The boxes in g and h represent the regions in (i,j), respectively. VNO morphology was unaffected in Kif26a−/− mice. (k–n) HE-stained OB sections from wild-type (k,m) and Kif26a−/− mice (l,n). The boxes in (k,l) represent the regions in (m,n), respectively. (o) Quantification revealed that the thickness of the neuronal layer of the MOE significantly differed between wild-type and Kif26a−/− mice. (p) VNO thickness did not significantly differ between wild-type and Kif26a−/− mice. (q) ONL thickness was not significantly different between wild-type and Kif26a−/− mice. MOE: main olfactory epithelium; VNO: vomeronasal organ; SP: nasal septum; ET: ethmoidal turbinates; OE: olfactory epithelium; RE: respiratory epithelium. DK: cilia/dendritic knobs; SC: supporting cells; ORN: olfactory receptor neurons; BC: basal cells; LP: lamina propria; ONL: olfactory nerve layer; GL: glomerular layer; EPL: external plexiform layer; MCL: mitral cell layer; GCL: granule cell layer; ONL: olfactory nerve layer. The scale bars represent 160 μm (a–d,k,l), 20 μm (e,f,i,j), and 80 μm (g,h,m,n).

Disorganization of the OE in Kif26a−/− mice. (a–h) Expression of GAP43 (green) and OMP (red) in the OE at P7. Compared with wild-type mice (a–d), Kif26a−/− mice (e–h) showed disorganization. (i) The number of GAP43-positive immature OSNs was significantly lower in Kif26a−/− mice than in wild-type mice. (j) The number of OMP-positive mature OSNs was significantly greater in Kif26a−/− mice than in wild-type mice. DAPI was used for nuclear staining. The scale bars represent 20 μm.

KIF26A is involved in the survival, proliferation, and neurite outgrowth of OSNs in the MOE

The results described above suggest that the loss of KIF26A leads to a reduced number of GAP43-positive immature OSNs and an increased number of OMP-positive neurons, accompanied by thinning and disorganization of the MOE. To investigate whether these phenotypes are accompanied by changes in apoptosis or proliferation, we conducted immunohistochemical analysis of MOE sections from mice at P7. The percentage of cleaved caspase-3–positive cells among β-tubulin III–positive neurons was significantly greater in Kif26a−/− mice (4.77 ± 0.566%) than in wild-type mice (1.13 ± 0.182%) (Fig. 6a–f, 6m; p < 0.0001: two-tailed unpaired t test after confirmation of normality by the Shapiro–Wilk test). Cleaved caspase-3-positive cells were distributed mainly in the basal layer. Furthermore, a BrdU incorporation assay at P1 revealed that the proportion of BrdU-labeled cells among β-tubulin III-positive neurons was significantly greater in the MOE of Kif26a−/− mice (7.146 ± 0.411%) than in the MOE of wild-type mice (1.507 ± 0. 205%) (Fig. 6g–l,n; p < 0.0001: two-tailed unpaired t test after confirmation of normality by the Shapiro–Wilk test). These BrdU-labeled cells appeared to be localized in the apical layer of the MOE. Together, these findings suggest that KIF26A deficiency leads to increased apoptosis of OSNs as well as increased proliferation of OSNs in the MOE.

Increased number of cleaved caspase-3-positive and BrdU-positive cells in the MOE of Kif26a−/− mice. (a–f) Distribution of cleaved caspase-3 (green) among β-tubulin III (red)-positive cells in the OE of Kif26a−/− (d–f) and wild-type (a–c) mice at P7. White arrowheads indicate cells positive for both cleaved caspase-3 and β-tubulin III. (g–l) BrdU incorporation assay in the OE at P1, showing BrdU (red)- and β-tubulin III (green)-positive cells in the OE of Kif26a−/− (j–l) and wild-type (g–i) mice. White arrowheads indicate cells positive for both BrdU and β-tubulin III. The inset shows a high-magnification view of a representative double-labeled cell (l). (m) Quantitative analysis revealed a significant increase in the proportion of cleaved caspase-3-positive apoptotic cells among β-tubulin III-positive cells in Kif26a−/− mice compared with that in wild-type control mice. (n) Quantitative analysis revealed a significant increase in the proportion of BrdU-positive cells among β-tubulin III-positive cells in Kif26a−/− mice compared with that in wild-type control mice. The scale bars represent 20 μm.

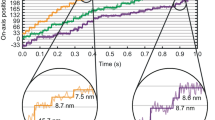

To gain further insight into the role of KIF26A in OSN maturation, we compared the behavior of primary cultures of neurons dissociated from Kif26a−/− and wild-type neonates under both low- (Fig. 7a,b) and high-density (Fig. 7d,e) conditions. Each individual neuron of OSNs can extend processes without contacting each other under low-density conditions, while high-density culture can result in the formation of networks through interactions between cells, the promotion of differentiation, and the expression of functions. Quantitative analysis revealed that axon length on DIV3 in Kif26a−/− neurons (73.10 ± 9.93 μm) under the low-density condition was significantly shorter than that in wild-type neurons (181.92 ± 15.58 μm) (Fig. 7c; p = 0.005; two-tailed unpaired t test after confirmation of normality by the Shapiro–Wilk test). Additionally, on DIV10 under the high-density condition, compared with wild-type neurons, Kif26a−/− neurons exhibited shorter, crooked, irregular, and more disorganized neurites (Fig. 7f,g), indicating impaired neurite outgrowth. While coordinated growth of neurites resulted in a bundle-like appearance under high-density conditions in wild-type neurons, knockout neurons exhibited impaired neurite growth and disrupted nerve bundle formation in Kif26a−/− mice. These results suggest that KIF26A is involved in the survival, proliferation, and neurite outgrowth of OSNs in the MOE.

Defects in neurite outgrowth in Kif26a−/− OSNs. (a,b) Representative OSNs dissociated from the olfactory epithelium at P5 and cultured until DIV3 under low-density conditions. Neurons were labeled with an antibody against the neuronal marker anti-β-tubulin III. Compared with shorter Kif26a−/− OSNs, wild-type OSNs (a) exhibit a bipolar morphology with short, thick dendrites and long, thin axonal processes (b). (c) Quantitative analysis revealed significantly longer axon lengths in cultured wild-type OSNs than in Kif26a−/− OSNs on DIV3. (d,e) Representative OSNs dissociated from wild-type (d) and Kif26a−/− (e) olfactory epithelium at P5 and cultured until DIV3 under high-density conditions. (f,g) Representative OSNs dissociated from wild-type (d) and Kif26a−/− (e) olfactory epithelium at P5 and cultured until DIV10 under high-density conditions. The scale bars represent 50 μm.

Impaired olfactory responses in Kif26a +/− mice

Kif26a−/− mice exhibit an abnormal OE that is characterized by increased apoptosis, enhanced proliferation, and impaired neurite outgrowth of OSN progenitors in the MOE. Therefore, the olfaction of these mice was examined. Behavioral testing was conducted on Kif26a+/− and wild-type mice at 8 weeks of age because Kif26a−/− mice die within two weeks after birth. Two tests were performed to analyze the olfaction of the mice: a buried food test and an innate olfactory preference test. First, the buried food test, which relies on an animal’s natural tendency to use olfactory cues for foraging, was used to confirm the ability of the mice to smell volatile odors. The main parameter is the latency to uncover a small piece of chow, cookie, or other palatable food that is hidden beneath a layer of cage bedding within a limited amount of time11. In the buried food test, compared with wild-type mice (157.67 ± 16.46 s), Kif26a+/− mice exhibited a significantly longer latency to locate the hidden food (224.42 ± 15.53 s) (Fig. 8a; p = 0.0074: two-tailed unpaired t test after confirmation of normality by the Shapiro–Wilk test). For a more specific assessment of olfactory function, an innate olfactory preference test was conducted. This test relies on an animal’s tendency to investigate novel smells and is used to test whether the animal can detect and differentiate different odors. In the innate olfactory preference test, Kif26a+/− mice spent significantly less time investigating attractive odors such as coconut (13.70 ± 1.05 s) than wild-type mice did (19.08 ± 0.96 s, p = 0.019; two-tailed unpaired t test after confirmation of normality by the Shapiro–Wilk test). Kif26a+/− mice also spent significantly less time investigating female urine (13.55 ± 1.95 s) than wild-type mice did (21.90 ± 2.28 s, p < 0.001: two-tailed unpaired t test after confirmation of normality by the Shapiro–Wilk test). Conversely, Kif26a+/− mice spent significantly more time investigating aversive odors such as 2-MB (median 5.16 s, IQR 6.91–3.50) than wild-type mice did (median 2.91 s, IQR 3.81–1.84, p < 0.05: two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test). Kif26a+/− mice also spent significantly more time investigating predator odor TMT (median 2.75 s, IQR 3.94–1.41) than wild-type mice did (median 0.62 s, IQR 1.0–0.23, p < 0.05: two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test). There were no significant differences in the time spent investigating odors such as DW (p = 0.896: two-tailed unpaired t test after confirmation of normality by the Shapiro–Wilk test), vanillin (p = 0.908: two-tailed unpaired t test after confirmation of normality by the Shapiro–Wilk test) or eugenol (p = 0.291: two-tailed unpaired t test after confirmation of normality by the Shapiro–Wilk test), which do not trigger innate olfactory responses in mice (Fig. 8b). These results collectively suggest that KIF26A is essential for sensing and discriminating olfactory functions.

Kif26a+/− mice exhibit impaired olfactory responses. (a) Buried food test. Compared with wild-type mice, adult Kif26a+/− mice presented longer latencies. (b) Innate olfactory preference test. Compared with wild-type mice, Kif26a+/− mice spent less time investigating attractive odors, such as coconut and female urine. Moreover, compared with wild-type mice, Kif26a+/− mice spent more time investigating aversive odors, such as 2-MB and TMT.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated the roles of KIF26A in the development and function of the OE. Kif26a is expressed in the MOE, VNO and OB (Fig. 1). The loss of KIF26A results in defective development of the neuronal layer, specifically in the MOE. Quantitative analysis revealed that the thickness of the MOE significantly differed between Kif26a−/− and wild-type mice, whereas that of the VNO and ONL was not significantly different (Fig. 4o–q). An explanation for the apparent regional differences in Kif26a−/− olfactory structure and function may be the independent developmental programs of the OE, VNO and OB. The thickness of the MOE and the number of GAP43-positive immature OSNs in the MOE were reduced in Kif26a−/− mice at P7. In contrast, KIF26A deficiency also led to an increased number and disorganization of OMP-positive mature OSNs at P7. Our data also suggest that KIF26A deficiency is further associated with increased apoptosis and accelerated proliferation of immature OSNs in the OE. The distribution of BrdU-positive OSNs appeared to be apical, suggesting that the accelerated proliferation of OMP-positive cells may result in an increased number of these cells in the spatially disorganized MOE of Kif26a−/− mice. Alternatively, it is also possible that enhanced proliferation of basal cells, rather than OMP-positive cells, followed by migration of the newly generated cells toward the apical layer, contributes to this observation. Future studies employing the colabeling of BrdU with GAP43 or OMP will be needed to elucidate these potential mechanisms. Moreover, cleaved caspase-3-positive OSNs were localized mainly in the basal layer, suggesting that apoptotic cell death of GAP43-positive cells may lead to a reduced number of these cells (Fig. 5). A recent study suggested that KIF26A plays critical roles in regulating the migration, dendritic and axonal development, and apoptosis of neurons12. Primary culture of Kif26a−/− OSNs revealed impaired neurite outgrowth and disorganization in vitro, including impaired nerve bundle formation. These findings may correspond to the disorganization of axon bundles observed in vivo (Fig. 5) and suggest that KIF26A plays a cell-autonomous role in promoting neurite outgrowth and proper axonal organization of OSNs. Finally, behavioral analyses revealed that KIF26A haploinsufficiency leads to impaired olfactory responses. These findings suggest that KIF26A plays important roles in the development and function of the OE and olfactory system (Fig. 8).

The MOE is the primary olfactory organ in mammals and is responsible for detecting odor molecules13,14. Our results indicate that KIF26A participates in the development of the MOE. The loss of KIF26A results in a reduced thickness of the neuronal layer, accompanied by a decrease in the number of immature OSNs. Increased apoptosis in the MOE of Kif26a−/− mice may contribute to this thinning, potentially triggering compensatory mechanisms such as accelerated cell proliferation, increased numbers of mature OSNs, and mature OSN disorganization. These findings are consistent with the known regenerative capacity of the OE, which continuously replenishes its neurons15. Through comprehensive gene expression analysis of Ac3−/− mice, Wang et al. provided evidence that the MAPK signaling pathway is important for cell proliferation and apoptosis in the MOE and that a critical olfactory signaling molecule is disrupted in these mice. On the basis of these findings, KIF26A may contribute to MOE development by regulating the GDNF–GFRα1–Ret–SHC–Grb2 signaling complex to activate Ras/ERK1/2, as previously shown in the development of the enteric nervous system4. Kif26a−/− OSNs also exhibit impaired axon outgrowth and disorganization in primary culture. Our previous study demonstrated that KIF26A binds to microtubules and that the microtubules of the enteric nervous system are less stable in the growth cones of Kif26a−/− mice than in those of wild-type mice4. Further studies of KIF26A will reveal the mechanisms underlying OSN development.

In the olfactory nervous system, two members of the neurotrophic family of GDNF, namely, GDNF and neurturin, play distinct physiological roles. GDNF and Ret are broadly expressed in both immature and mature OSNs, whereas neurturin is selectively expressed in a subpopulation of OSNs in specific zones of the olfactory nerve. The expression of GDNF family receptors is also different: mature OSNs and their axons preferentially express GFRα1, whereas progenitors and immature neurons preferentially express GFRα2. In the OB, GDNF is highly expressed in mitral and tufted cells, as well as in periglomerular cells, with distribution patterns generally resembling those of Ret8. GFRα1 is critical for the development and function of the main olfactory system9, and there are several phenotypic similarities in the OE and olfactory function between GFRα1 and Kif26a mutant mice. Mutant mice lacking either KIF26A or GFRα1 show diminished responses in behavioral olfactory tests. Moreover, the loss of GFRα1 leads to a thinner OE with fewer OSNs and increased numbers of dividing precursor cells at P0. In GFRα1−/− mice, immature OSN axon bundles are enlarged, and the number of associated olfactory ensheathing cells is increased, suggesting that GFRα1 is involved in the maturation and migration of OSNs8. Neuron-specific activation of Ras/ERK1/2 in the MOE may rescue the phenotypes observed in Kif26a−/− and GFRα1−/− mice, which would help elucidate the key signal transduction pathways that are required for MOE function. Our results also revealed impaired neurite outgrowth in Kif26a−/− OSNs in vitro. These findings suggest that KIF26A may induce the differentiation or regeneration of olfactory neurons in vitro, which has potential implications for regenerative medicine16.

We have also reported that Kif26a−/− mice exhibit intense and prolonged nociceptive responses and that KIF26A directly interacts with focal adhesion kinase (FAK) to antagonize its function in integrin–Src family kinase–FAK signaling pathways17. Integrin signaling contributes to the development and function of olfactory neurons by regulating axonal extension and connection from the OE to the OB as well as axonal branch stability18,19. However, several transcriptomic studies suggest that integrin signaling is unlikely to play a direct role in OE development and differentiation20,21,22,23.

This study has several limitations, including the fact that Kif26a−/− mice died at approximately two weeks of age. We previously reported that Kif26a−/− mice exhibit impaired development of the enteric nervous system, leading to megacolon and postnatal growth retardation, which likely contribute to their early lethality4. In the present study, Kif26a−/− mice did not display any specific signs of lethality induced by severe olfactory dysfunction, such as failure to suckle. Therefore, the neonatal death observed in this study is most plausibly attributable to systemic abnormalities, particularly intestinal dysfunction, rather than to olfactory impairment. Behavioral testing was performed on heterozygous mice for the reasons mentioned above, whereas histological and molecular analyses were focused on wild-type and homozygous knockout mice. Although examining the morphology of the MOE in Kif26a−/− mice would further strengthen the link between structure and function, given that KIF26A expression is not completely absent in Kif26a+/− mice and that heterozygotes exhibit only subtle behavioral alterations, the behavioral phenotypes likely reflect a partial reduction in KIF26A-dependent signaling rather than gross anatomical defects. We therefore believe that the current functional data adequately capture the mild nature of the heterozygous phenotype.

In summary, we demonstrated that KIF26A plays critical roles in the development of the MOE by regulating cell survival, proliferation, and neurite outgrowth—processes that are indispensable for proper olfactory responses in mice. Because other kinesin family members, such as KIF1A, KIF1C, KIF3C, KIF5A, KIF5C, KIF13B, and KIF21B, have also been identified as candidate regulators of the MOE24, further investigation of these proteins may help elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the regulation of olfaction in mice.

Methods

Animals

The Animal Care and Use Committee of Jichi Medical University approved all the animal experiments (17036–01), which complied with the ARRIVE guidelines. All the experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Mice were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane (induction at 3–4% and maintenance at 1–2% in oxygen) delivered via a calibrated vaporizer (NARCOBIT-E; Natsume, Tokyo, Japan) before perfusion fixation. Euthanasia was performed by cervical dislocation. To generate Kif26a knockout mice, the px330 plasmid (42,230; Addgene, Watertown, MA, USA) was used as a CRISPR expression vector25. The left (ACACCTGCCCTAATCCCCGC) and right (TTGGAAGATATGGGTGTACG) 20-nt sequences were inserted into px330. On the basis of the EGxxFP system26, the cleavage activity of the pX330-kif26a vector was verified in cultured cells. Left and right pX330-Kif26a vectors were injected into the pronuclei of one-cell embryos. Three types of mixed anesthetic agents (0.2 mg/kg medetomidine, 4.0 mg/kg midazolam, and 2.5 mg/kg butorphanol) were administered subcutaneously to pseudopregnant female mice, into which the injected embryos were subsequently transferred according to standard protocols27. F0 mice were genotyped for the presence of the Kif26a exon 7 deletion mutation via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the following primer pair: 5′-TGTGGACTGTCTGCCTGAATGTG-3′ and 5′-TCTCCTTGCGTTCGTCAATAAG-3′. The Kif26a+/− mice analyzed in this study were maintained in the C57BL/6 background after backcrossing for more than eight generations. Mice for the analyses and for breeding to generate Kif26a+/+, Kif26a+/−, and Kif26a−/− genotypes were obtained from Japan SLC (Hamamatsu, Japan) and weighed approximately 0.25–0.35 g for wild-type mice at E14.5; 1.3–1.6 g for both wild-type and knockout mice at P0; 2.5–3.0 g for wild-type and 2.0–2.5 g for knockout mice at P5; and 3.0–4.0 g for wild-type and 2.0–3.0 g for knockout mice at P7. At 8 weeks of age, both wild-type and heterozygous knockout mice weighed 23–27 g, with an average of 25 g.

Immunohistochemistry and quantification by morphometric analysis

Immunohistochemistry was performed on paraffin-embedded and frozen sections as previously described4 using the primary and secondary antibodies listed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. DAPI mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) was used for nuclear staining. Immunofluorescence images were obtained using an FV1200 microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) in confocal mode. As shown in Fig. 4, the sections were stained with hematoxylin–eosin (HE). Data collected from three independent experiments were quantified unless otherwise indicated. To analyze the thickness of the neuronal layers of the MOE and VNO (Fig. 4o,p), data were obtained from 20 randomly selected sections of three pairs of wild-type and Kif26a−/− mice. To analyze the axon length of cultured wild-type and Kif26a−/− OSNs on day in vitro 3 (DIV3) (Fig. 7c), 30 neurons from three pairs of wild-type and Kif26a−/− mice were examined in each experiment. Cell numbers and axon lengths were analyzed using NIH ImageJ 1.54p (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

5′-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation study

BrdU (B5002; Sigma–Aldrich) was intraperitoneally administered at 180 μg/g body weight to the mice at postnatal day (P) 0. The mice were sacrificed within 24 h, and coronal sections were prepared. The sections were incubated with 0.2 N HCl at 37 °C for 30 min for denaturation and then neutralized with 0.1 M borate buffer (pH 8.8) at room temperature for 10 min. After blocking with 10% normal goat serum in PBS supplemented with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 30 min, the sections were double-stained with antibodies against BrdU (6326; Abcam) and GAP43 (300–143; Novus Biologicals) at 4 °C overnight, followed by incubation with the corresponding Alexa Fluor™-labeled secondary antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 1 h. Images were acquired using an FV1200 confocal microscope (Olympus Corporation).

In situ hybridization

In situ hybridization was performed as previously described4. Briefly, the tissues were deparaffinized following dehydration, embedding, and sectioning. The sections were subsequently washed with 5 × SSC for 15 min at room temperature and hybridized with digoxigenin-labeled RNA probes. Fluorescence hybridization was performed as described previously28. Briefly, the sections were hybridized with FITC-labeled Kif26a sense and antisense probes, and after hybridization and washing, the sections were incubated with POD-conjugated anti-FITC antibody (11,426,346,910; Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). The Kif26a signal was amplified via DNP-TSA tyramide (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). For double immunostaining, the sections were incubated with goat polyclonal anti-DNP antibody (A150-117A; Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX, USA) and anti-GAP43 (NB300-143; Novus Biologicals) or anti-OMP (019-22,291; FUJIFILM Wako) antibodies, followed by incubation with secondary antibodies. The signals were detected using an FV1200 confocal microscope (Olympus Corporation).

Primary OSN culture

Primary cultures of murine dissociated OSNs from the MOE were prepared as previously described17,29. Briefly, OSNs were isolated from mice at P5 and dissociated using collagenase, followed by treatment with 0.25% trypsin (25-300-062; Gibco/Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, MA, USA) for 15 min at 37 °C. After digestion, the tissues were triturated using a Pasteur pipette (0.3–0.5 mm tip) and centrifuged at 200×g at 4 °C, after which the supernatants were discarded. The pellets containing OSNs were subsequently resuspended in Neurobasal-A medium (Gibco/Thermo Fisher Scientific) (Waltham, MA, USA). The cells were counted and plated at a density of 5 × 104 cells/cm2 for low-density cultures and 5 × 105 cells/cm2 for high-density cultures onto poly-L-lysine (P-2636; Sigma–Aldrich)- and laminin (23,017–015; Invitrogen/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA)-coated dishes (628,770; Greiner Bio-One, Kremsmünster, Austria). The cultures were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The culture medium consisted of neurobasal-A supplemented with 5% horse serum, 2% B27 supplement (17,504–044; Gibco), 0.5 mM L-glutamine (G7513; Sigma–Aldrich), 100 mg/ml streptomycin sulfate, and 100 units/ml penicillin G sodium (15,070–063; Gibco). Cells at DIV3 and DIV10 were subjected to staining to identify immature and mature OSNs, respectively. After immunostaining, the cells were fixed and observed using a confocal laser scanning microscope (FV1200; Olympus Corporation). More than 20 neurons were analyzed per experiment, and the data are expressed as the means ± SEM from three independent experiments.

Behavioral tests

Twelve pairs of Kif26a+/+ and Kif26a+/− male mice (8 weeks of age) were exposed to a uniform-sized palatable food stimulus (Teddy Grahams; Nabisco/Mondelez International, East Hanover, NJ, USA) to become familiar with the odor on three consecutive days prior to testing. After 16 h of food deprivation, the mice were placed in the test cage. After a 5-min acclimation period, each mouse was transferred to a clean, empty cage. The food stimulus was randomly buried 1 cm beneath the bedding. Each mouse was returned to the test cage, and the latency to locate the buried stimulus was recorded. For the innate olfactory preference test, which was conducted to more specifically assess olfactory function, mice were transferred to a test cage, and a cotton-tipped wooden applicator scented with either distilled water or a test odorant was introduced. A stopwatch was used to record the cumulative time spent sniffing the tip during a 3-min trial. Sniffing was scored when the mouse was oriented toward the cotton tip with its nose positioned within 2 cm of the tip. After each trial, the lid of the cage was removed, and the applicator was quickly replaced with a new one. Odorant concentrations were as follows: distilled water (20 μL), coconut (20 μL), urine from female mice (20 μL), vanillin (64 μM, 20 μL), eugenol (128 μM, 20 μL), 2-methylbutyric acid (2-MB; 8.7 M, 20 μL), and trimethyl-thiazoline (TMT; 7.65 M, 20 μL). Urine from female mice was pooled from 10 noncagemate individuals and likely contained a mixture of samples from females at various stages of the estrous cycle. Other odorants (Sigma) were dissolved in distilled water. The results are presented as the mean latency ± SEM, and statistical comparisons between genotypes were conducted using unpaired t tests (Fig. 8b).

Experimental design

This study investigated the role of KIF26A in the development and function of the main olfactory system in mice using both homozygous (Kif26a−/−) and heterozygous (Kif26a+/−) knockout models generated by CRISPR/Cas9 in the C57BL/6 background. Analyses were performed primarily at postnatal day 7 (P7) for morphological and molecular assessments, as Kif26a−/− mice died at approximately two weeks of age. Behavioral assays were conducted on 8-week-old Kif26a+/− mice and their wild-type littermates to evaluate olfactory function. For histological and molecular analyses, at least three animals per group (sex-matched) were used, and multiple Sects. (3–5) per animal were examined to ensure representativeness. For immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization, at least 3 biological replicates and 2–3 technical replicates per assay were performed. For the BrdU incorporation and apoptosis assays, 3–4 mice per group were used, and 4–6 fields per section were analyzed. Primary neuron cultures were prepared from P5 wild-type and Kif26a−/− pups (2–3 litters per genotype). Neurite outgrowth was assessed under both low- and high-density culture conditions using 3–4 independent cultures per genotype. For behavioral testing (buried food test and innate olfactory preference test), a total of 12 male mice per genotype were used. All the behavioral tests were performed during the light cycle, and the investigators were blinded to the genotype. Sample sizes were chosen on the basis of previous studies to ensure statistical power while minimizing animal use. No animals were excluded from the analysis. Both within-subject (odor type in behavioral tests) and between-subject (genotype) factors were considered in the experimental design.

Statistical analysis

All the statistical analyses and graph generation were performed using SPSS version 26 and GraphPad Prism version 10. Data normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. For normally distributed data, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t tests were applied (Figs. 4o–q, 5i–j, 6m–n, 7c, and 8a). For the innate olfactory preference tests, the data were also tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. When the data followed a normal distribution, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t tests were used to compare wild-type and Kif26a+/− mice for water, coconut, mouse urine, vanillin, and eugenol. For data that did not meet normality assumptions (2-MB and TMT), two-tailed Mann–Whitney U tests were applied. Each odor stimulus was analyzed separately. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM for normally distributed variables and median (IQR) for nonnormally distributed variables. In all the graphs, the asterisks indicate statistically significant p values ≤ 0.05.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Hirokawa, N. & Noda, Y. Intracellular transport and kinesin superfamily proteins, KIFs: structure, function, and dynamics. Physiol. Rev. 88, 1089–1118 (2008).

Hirokawa, N., Noda, Y., Tanaka, Y. & Niwa, S. Kinesin superfamily motor proteins and intracellular transport. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 682–696 (2009).

Hirokawa, N. & Tanaka, Y. Kinesin superfamily proteins (KIFs): Various functions and their relevance for important phenomena in life and diseases. Exp. Cell Res. 334, 16–25 (2015).

Zhou, R., Niwa, S., Homma, N., Takei, Y. & Hirokawa, N. KIF26A is an unconventional kinesin and regulates GDNF-Ret signaling in enteric neuronal development. Cell 139, 802–813 (2009).

Choi-Lundberg, D. L. & Bohn, M. C. Ontogeny and distribution of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) mRNA in rat. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 85, 80–88 (1995).

Nosrat, C. A., Tomac, A., Hoffer, B. J. & Olson, L. Cellular and developmental patterns of expression of Ret and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor receptor alpha mRNAs. Exp. Brain Res. 115, 410–422 (1997).

Trupp, M., Belluardo, N., Funakoshi, H. & Ibanez, C. F. Complementary and overlapping expression of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), c-ret proto-oncogene, and GDNF receptor-alpha indicates multiple mechanisms of trophic actions in the adult rat CNS. J. Neurosci. 17, 3554–3567 (1997).

Maroldt, H., Kaplinovsky, T. & Cunningham, M. Immunohistochemical expression of two members of the GDNF family of growth factors and their receptors in the olfactory system. J. Neurocytol. 34, 241–255 (2005).

Marks, C., Belluscio, L. & Ibanez, C. F. Critical role of GFRalpha1 in the development and function of the main olfactory system. J. Neurosci. 32, 17306–17320 (2012).

Treloar, H. B., Ray, A., Dinglasan, L. A., Schachner, M. & Greer, C. A. Tenascin-C is an inhibitory boundary molecule in the developing olfactory bulb. J. Neurosci. 29, 9405–9416 (2009).

Yang, M. & Crawley, J. N. Simple behavioral assessment of mouse olfaction. Curr Protoc Neurosci. Chapter 8:Unit 8.24 (2009).

Qian, X. et al. Loss of non-motor kinesin KIF26A causes congenital brain malformations via dysregulated neuronal migration and axonal growth as well as apoptosis. Dev. Cell. 57, 2381-2396.e13 (2022).

Wang, Z., Nudelman, A. & Storm, D. R. Are pheromones detected through the main olfactory epithelium? Mol. Neurobiol. 35, 317–323 (2007).

Koike, K. et al. Danger perception and stress response through an olfactory sensor for the bacterial metabolite hydrogen sulfide. Neuron 109, 2469–2484 (2021).

Shetty, R. S. et al. Transcriptional changes during neuronal death and replacement in the olfactory epithelium. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 30, 583–600 (2005).

Sipione, R. et al. Axonal regrowth of olfactory sensory neurons in vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 12863 (2023).

Wang, L. et al. The atypical kinesin KIF26A facilitates termination of nociceptive responses by sequestering focal adhesion kinase. Cell Rep. 24, 2894–2907 (2018).

Billuart, P., Winter, C. G., Maresh, A., Zhao, X. & Luo, L. Regulating axon branch stability: the role of p190 RhoGAP in repressing a retraction signaling pathway. Cell 107, 195–207 (2001).

Wang, L. et al. The SRC homology 2 domain protein Shep1 plays an important role in the penetration of olfactory sensory axons into the forebrain. J. Neurosci. 30, 13201–13210 (2010).

Rimbault, M., Robin, S., Vaysse, A. & Galibert, F. RNA profiles of rat olfactory epithelia: Individual and age related variations. BMC Genom. 10, 572 (2009).

Fischl, A. M., Heron, P. M., Stromberg, A. J. & McClintock, T. S. Activity-dependent genes in mouse olfactory sensory neurons. Chem. Sens. 39, 439–449 (2014).

Sammeta, N., Yu, T. T., Bose, S. C. & McClintock, T. S. Mouse olfactory sensory neurons express 10,000 genes. J. Comp. Neurol. 502, 1138–1156 (2007).

Nickell, M. D., Breheny, P., Stromberg, A. J. & McClintock, T. S. Genomics of mature and immature olfactory sensory neurons. J. Comp. Neurol. 520, 2608–2629 (2012).

Wang, Z. et al. Gene expression profiles of main olfactory epithelium in adenylyl cyclase 3 knockout mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 28320–28333 (2015).

Cong, L. et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 339, 819–823 (2013).

Mashiko, D. et al. Generation of mutant mice by pronuclear injection of circular plasmid expressing Cas9 and single guided RNA. Sci Rep. 3, 3355 (2013).

Gordon, J. W. & Ruddle, F. H. Integration and stable germ line transmission of genes injected into mouse pronuclei. Science 214, 1244–1246 (1981).

Watakabe, A., Komatsu, Y., Ohsawa, S. & Yamamori, T. Fluorescent in situ hybridization technique for cell type identification and characterization in the central nervous system. Methods 52, 367–374 (2010).

Micholt, E. et al. Primary culture of embryonic rat olfactory receptor neurons. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. Anim. 48, 650–659 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Nobutaka Hirokawa and Dr. Yosuke Tanaka for their intellectual assistance and Dr. Yoshiharu Kido, Ms. Hiromi Morita and Mr. Shun-ichi Kunii for their technical assistance. We also thank American Journal Experts for the editing of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Scholarship Fund Young/Women Researchers to R.Z. and JSPS KAKENHI (grant number 23K07995) to W.N.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RZ and YN designed the research; RZ and SM performed the research; MT, SM, HM, and ST contributed unpublished reagents/analytic tools; RZ analyzed the data; and RZ and WN wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, R., Nishimura, W., Takahashi, M. et al. KIF26A regulates the development and function of the main olfactory epithelium in mice. Sci Rep 16, 945 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30412-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30412-8