Abstract

The current research investigated the nutritional composition of wheat and corn bran hydrolysates and their impact on bread quality. For this purpose, in the 1st phase wheat and corn bran were subjected to hydrothermal treatment as a pretreatment (at 121 °C for 45 min) to obtain hydrolysates. In the 2nd phase wheat and corn bran hydrolysates was characterized for their chemical composition, antioxidant potential and functional quality. Wheat bran hydrolysates were richer in protein (11.63 ± 0.13%), ash (2.16 ± 0.04%), and nitrogen-free extract (57.66 ± 1.42%), whereas corn bran hydrolysates contained higher fat (5.47 ± 0.07%), fiber (11.79 ± 0.09%), and moisture (16.32 ± 0.15%). Both wheat and corn bran hydrolysates revealed strong antioxidant potential however, wheat bran hydrolysates were richer in phenolic and flavonoids, whereas corn bran hydrolysates showed higher radical scavenging and reducing power activities. In the 3rd phase, bread was prepared using wheat flour and wheat and corn bran hydrolysates in treatments T0, T1, and T2, and subsequently evaluated for structural, textural, and sensory attributes. Structural analysis using FTIR and SEM indicates the incorporation of bran hydrolysates altered the gluten matrix, by introducing diverse functional groups and modifying the bread’s microstructure. Textural analysis showed greater firmness in wheat bran hydrolysate bread (T1), which also received the highest sensory scores and overall acceptability. Thus, the results elucidated the potential of wheat and corn bran hydrolysates to improve the nutritional, structural, and sensory quality of bread for functional food applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A variety of cereals including wheat, corn, barley, oats and millet are grown globally and serve as staple foods due to their rich nutritional composition. Cereals supply the macronutrients which are proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates as well as the micronutrients which are vitamins, and minerals that make up the human diet1. Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.,) known as “King of Cereals” is one of the most extensively harvested crop which provides 20% of the world’s calories and protein and serves as the primary food source for 4.5 billion people in developing nations. However, corn is the most widely cultivated cereal globally, consumed directly and indirectly for food, animal feed, processed products and industrial application2. Cereal grains such as wheat (Triticum aestivum L.,) and corn (Zea mays L.) are not only staple food crops but also important sources of valuable by-products produced during milling. The milling industry provides cereal bran, germ, and screenings, which possess a rich nutritional profile and significant health benefits3,4. Among these, cereal bran consist of the pericarp, testa, and hyaline and aleurone layer. Wheat milling, one of the largest agro-industries in Pakistan and worldwide, separates the nutrient-dense bran from the starchy endosperm used for refined flour production. Corn is processed using wet and dry milling techniques. Dry milling yields maize bran, from the pericarp along with germ, while wet milling produces starch, oil, protein, and fiber-rich fractions5. Wheat and corn bran are rich in cellulose, hemicellulose, starch, proteins, oils, lignin, minerals and vitamins, making them promising functional ingredients6. Wheat bran contributes up to 25% of the grain weight and consists 55–60% non-starchy carbohydrates, 13–18% proteins, and significant minerals and bioactive compounds. Corn bran provides substantial amount of insoluble fiber (up to 86%) proteins, and phenolic compounds7. Nutritionally, bran fractions produced by milling are rich in fiber, minerals, vitamin B6, thiamine, folate and vitamin E and some phytochemicals, in particular antioxidants such as phenolic compounds. Epidemiological and experimental evidence suggests that dietary fiber helps reduce the risk of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and certain cancers8,9. Wheat and corn bran are valuable functional ingredients that can enhance dietary fiber content in bakery products. In general, bran is used for the biofortification for bread making and other bakery goods as a value addition or valorization of cereal byproducts10. However, the direct addition of raw bran to bakery products can negatively effects dough rheology, loaf volume, and sensory quality due to gluten network disruption and water redistribution. To overcome these challenges, various pretreatment methods such as hydrothermal processing, enzymatic hydrolysis, steam explosion, and acid/base treatments are employed11. These methods improve solubility, release of bioactive compounds, and enhance the structural and functional properties of bran, making it more suitable for use in health-promoting foods without compromising processing quality or consumer acceptability. In particular, hydrolysis improves the nutritional and technological qualities of cereal brans by transforming hemicellulose into soluble oligosaccharides, releasing phenolic compounds, and boosting antioxidant potential. This makes the brans more suitable for use in functional foods and nutraceuticals. Thus the present study aim to determine the nutritional composition of wheat and corn brans, develop their hydrolysates, evaluate the nutritional and antioxidant properties of the hydrolysates, and investigate their effects on bread structure, texture, color, and sensory attributes.

Materials and methods

This study was conducted at Food Analysis Lab, Department of Food science, Government College University, Faisalabad (GCUF). Additionally, bread development was performed in the Food Processing Hall, Department of Food science, (GCUF).

Procurement of raw material

Wheat and corn bran were purchased from Ayub Agriculture Research Institute (AARI), Faisalabad. Other ingredients such as butter, sugar, salt, baking powder, and egg were also purchased from the local shops of Faisalabad and brought into the baking hall. The reagents and chemicals of analytical grade were obtained from the departmental laboratories and sourced from Sigma Aldrich. All raw ingredients were stored at room temperature in polythene bags to prevent moisture absorption and microbial contamination before further processing.

Proximate composition of wheat and corn bran

The proximate analysis of various wheat and oat bran was performed to determine the level of Nitrogen Free Extract (NFE), as well as moisture, ash, crude fat, crude protein, and crude fiber, agreeing to their corresponding methods as defined in AACC12.

Hydrothermal treatment

Wheat and corn bran hydrolysates were prepared by hydrothermal treatment, wherein bran samples were suspended in distilled water (8:1 g/g) and autoclaved at 121 °C under 15 psi for 45 min. The hydrolyzed slurry was filtered through muslin cloth followed by Whatman No.1 filter paper to obtain the liquid fraction. The filtrates were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C to remove insoluble residues, and the resulting supernatant containing the released hydrolysates was collected. Finally, the hydrolysates were spray dried (Model ESDTi, Department of Food Science and Technology, GCUF) under controlled conditions (inlet 200 °C; outlet 95 °C; feed rate 5mL/min; nozzle diameter 0.7 mm; compressed air pressure 8 psi bar) to obtain a stable powder which was stored in polythene bags for further analysis.

Chemical composition of wheat & corn hydrolysates

Wheat and corn bran hydrolysates were analyzed for their chemical composition by following the method given in the AACC12 named as Moisture (Method no. 44–5.02), Ash (Method no. 08–01), Fat (Method no. 30 − 25), Crude Protein (Method no. 46–10.01), Crude Fibber (Method no. 32–10.01). However, the following equation was used to determine and nitrogen-free extract (NFE):

Antioxidant activity

Diphenyl Picrylhydrazyl assay

The free radical scavenging potential of wheat and corn bran hydrolysates were determined using the diphenyl hydrazyl assay (DPPH) and by following the method given by Turkmen et al.13A 100 mg sample of wheat and corn bran hydrolysates was dispersed in 100mL of 99% ethanol and shaken at 300 rpm for 20 min using an IKA-WERKE shaker (Germany). For an assay 0.1 mL of the ethanolic extract was beaten with 3.9 mL of methanolic DPPH solution (0.025 g/L). The mixture was prepared in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. The absorbance was then measured at 517 nm using a spectrophotometer (IRMECO, U2020).The radical scavenging activity was expressed in mmol Trolox Equivalents per gram (mmol TE/g).All samples were analyzed in triplicate, and the results were reported as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). The scavenging activity was calculated using the following equation:

Where the sample absorbance value is As, and the blank absorbance value is A0.

Ferric reducing antioxidant assay

The Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) assay was carried out by following the method given by Waleed et al.14 with slight modifications. For the analysis, 100 mg of wheat and corn bran hydrolysates extract was mixed with 100 µL of the ferric-TPTZ reagent (2,4,6-tripyridyl-s-triazine) reagent prepared by mixing 300 mmol/L acetate buffer (pH 3.6), 10 mmol L−1 TPTZ in 40 mmol L−1 HCl and 20 mmol/L FeCl3 with 10:1:1 and measured at 593 nm using UV-Vis spectrophotometer. FeSO4·7H2O was used as a standard and calibration curve was prepared with six concentrations between 1 and 1000 µmol g−1 and antioxidant power assessed through FRAP was expressed as µmol Fe2+ equiv/g−1.

2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) assay

The ABTS assay was used to determine antioxidant activity, and the results were expressed as Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity (TEAC) per 100 g of dry matter. The assay was performed according to the methodology described by Chen et al.15 ,using Trolox as the standard. All analyses were carried out in Triplicates.

Total phenolic content

According to Hussain et al.16, the total phenolic content (TPC) of wheat and corn bran hydrolysates was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu method, with Gallic acid as the standard. 100 mg of extract was oxidized the reagent, followed by neutralization with sodium carbonate and dilution to 10mL. After 2 h of incubation, absorbance was measured at 760 nm using a spectrophotometer (IRMECO, U2020). The results were expressed as milligrams of Gallic acid equivalents per gram of material (mg GAE/g).

Total flavonoid content

The total flavonoid content (TFC) of wheat and corn bran hydrolysate samples was determined using the spectrophotometric method described by Chandra et al.17, with some modifications. Absorbance was measured at 415 nm, and the results were expressed as rutin equivalents (µg RE/g DM).

Product development

The usual recipe provided in AACC12 was used to prepare the bread. Butter, salt, baking powder, yeast, ghee, water, and flour, was used as common ingredients in bread preparation. Add the yeast, water, and a little amount of sugar or honey in a sizable basin or stand mixer. Rest for 05 to 10 min, or until foaming and bubbling. Wheat and corn bran hydrolysates, as given in Table 1, were added and mixed homogeneously in a laboratory mixer bowl for 10 min at the specified ratios. After the homogenous mixing, a resting period of 10 to 15 min was applied. Allowed to rise in a warm environment for approximately 1–1/2 hours with the cover of a dish towel or plastic wrap on top. Then, placed each ball into a long log and then into loaf pans that have been oiled. Baking was accomplished at 350 °F for 30 to 33 min followed by cooling at room temperature. After cooling, the bread was packed in propylene bags.

Structural analysis

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

Bread samples (T0, T1, and T2) were analyzed using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) (Shimadzu 8400) to determine their functional components based on absorbance spectra, which ranged from 4000 to 400 cm−1. FTIR employs continuous infrared radiation coupled with a computer-based system to detect the functional groups in bread samples. The resulting spectra were used to identify functional moieties derived from chemical structures, molecular bonding, and functional groups18.

Scanning electron microscope

The morphological characterization of bread samples (T0, T1 and T2) were performed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Emcraft CubeSeries, South Korea) at the Department of Physics, (GCUF) following the methodology of Medina-Jaramillo et al.19 Samples were mounted on aluminum stubs, coated with a thin layer of gold to enhance conductivity, and examined at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV. High-resolution images were obtained to analyze the surface morphology.

Textural analysis of bread

The textural of bread samples was evaluated using a modified compression test as described by Zhang et al.19 Each sample underwent a double compression cycle to 50% of its original height to determine crumb hardness and structural stability. The force required to fracture the samples was recorded, and the average hardness values were calculated according to AACC12 Method 74-09.01.

Color analysis

The color of bread was determined using a colorimeter (ST-CP60, Stalwart, China) by following the method of Bouaziz et al.20 The instrument was calibrated with a standard white tile (L* = 93.5, a* = 1.0, and b* = 0.8) prior to measurement. Color values were recorded in International Commission on Illumination Lab coordinates (CIE), where L* (L = 0 gives black and L = 100 gives white) a* (-a = greenness and + a = redness) and b* (-b = blueness and + b = yellowness). Measurements were taken at three different positions on each bread slice at room temperature.

Sensory evaluation

The trained panel of the Department of Food science evaluated the sensory qualities of bread using a nine-point hedonic scale in accordance with the methods given by Javed et al.21.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted in triplicate, and results were expressed as Mean ± Standard deviation. Analysis of variance (One-way ANOVA) was performed using Statistix 8.1 to determine statistical significance at p ≤ 0.05. Tuckey’s test was further applied to evaluate the effects of wheat and corn bran hydrolysates on bread.

Results and discussion

This research was conducted at the Food Analysis Lab, Department of Food Science, Government College University, Faisalabad. Wheat and corn bran hydrolysates, are rich in bioactive compounds, proteins, and fibers. These are of growing interest for their ability to enhance the nutritional, functional, and sensory qualities of food. The study aimed to evaluate the effects of incorporating these hydrolysates into bread formulations, focusing on their impact on chemical composition, structural characteristics, textural properties and sensory attributes.

Chemical composition of wheat & corn Bran

The physicochemical properties of food products have great importance because these are responsible for the final quality of the product. Physical and chemical changes in each constituent and ingredient results from processing operations and often leads to physical, chemical, sensory, and nutritional changes in the food22. To evaluate the general composition and nutritional quality of any component intended for use in food product development, chemical assay is a crucial requirement. For this purpose, proximate composition of wheat and corn bran was determined according to the standard procedures as outlined by the American Association of Cereal Chemists (AACC)12. Mean results for moisture, ash, protein, fat, fiber and NFE present in wheat and corn bran are shown in Table 2. Moisture content plays a critical role in determining the freshness, stability, and storage quality of wheat and corn bran. Higher moisture content increase the risk of microbial growth, while excessively low levels may reduce protein quality. In our current research moisture content present in wheat and corn bran was 11.05 ± 0.24% and 10.76 ± 0.12 respectively. However, protein, ash, fat, fiber and NFE content in wheat and corn bran were (12.34 ± 0.33, 13.31 ± 0.15%), (3.14 ± 0.05, 2.45 ± 0.07%), (3.92 ± 0.12, 6.86 ± 0.10%), (23.17 ± 0.28, 15.07 ± 0.21%) and (46.38 ± 1.15, 51.55 ± 0.41%) respectively. Wheat and corn bran are rich sources of essential nutrients that contribute to their nutritional and functional value. Protein is a major component influencing nutritionally quality, functionality, and baking properties. However, crude fiber is abundant in bran which constitute indigestible components like lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose23. They support digestive health and help regulate blood glucose and cholesterol levels. Variations in these components are influenced by genetic differences, environmental conditions, and processing methods. The proximate composition of corn bran was previously determined by Afangide et al.24 and the results of the present study were found to be consistent with their findings. Thus, the results of this study showed the nutritional significance of wheat and corn bran. Although regarded as a waste wheat and corn brans are rich in crude protein, fiber, and carbohydrates. These components enhance their value as a functional ingredients in food and feed applications.

Chemical composition of wheat & corn Bran hydrolysates

In our current research chemical composition of wheat and corn bran was probed and the mean results for moisture, ash fat, fiber and NFE are shown in Table 3. The proximate composition of wheat and corn bran hydrolysates showed notable differences in their nutritional profile. Corn bran hydrolysates showed greater moisture (16.32 ± 0.15%), fat (5.47 ± 0.07%) and fiber (11.79 ± 0.09%) while wheat bran hydrolysates showed higher amount of protein (11.63 ± 0.13%), ash (2.16 ± 0.04%), and NFE content (57.66 ± 1.24%). These variations presents the influence of raw material composition, and processing conditions. Moreover, factors such as crop variety, temperature, and soil minerals further effect the quality and composition of the resulting hydrolysates.

Antioxidant activity of wheat & corn Bran hydrolysates

Antioxidants play a vital role in protecting food quality by preventing oxidative lipid degradation and scavenging free radicals. Their activity is mainly attributed to phenolic compounds, including flavonoids, which neutralize reactive oxygen species25. The antioxidant capacity is commonly evaluated using assays such as DPPH, FRAP, and ABTS. These methods collectively provide discernment into the antioxidant potential of bran-based products. In our current research the antioxidant activity of wheat and corn bran hydrolysates was significantly enhanced after hydrothermal treatment as shown in Table 4. The mean results showed an increase content of TPC (812.63 ± 2.26 mg GAE/g) and TFC (205.19 ± 1.89 mg RE/g) in wheat bran hydrolysates as compared to corn bran hydrolysates where TPC and TFC were 3.25 ± 0.05 mg GAE/g and 163.08 ± 1.45 mg RE/g respectively. However, corn bran hydrolysates showed the highest values for DPPH (77.62 ± 0.24 mg GAE/g) and FRAP (63.32 ± 1.20 µmol Fe2+ equiv/g), while wheat bran hydrolysates indicate a higher ABTS capacity (63.48 ± 0.15 µmol TEAC/100). These results indicate that hydrothermal treatment altered the bran structure and promoted the release of bioactive compounds. This confirms the potential of bran hydrolysates as valuable natural antioxidant sources for functional food applications. Previously, Wang et al.26 probed the antioxidant potential of corn protein hydrolysates and the results were in line with our current findings. Similarly, Similarly, Zhu et al.27 evaluated the antioxidant and free radical scavenging activities of wheat germ protein hydrolysates (WGPH) and similar results were obtained.

Product development

Bread was prepared by incorporating powdered wheat and corn bran hydrolysates at 10% substitution levels. Three treatments were formulated: T0 (100% wheat flour, control), T1 (90% wheat flour + 10% wheat bran hydrolysates), and T2 (90% wheat flour + 10% corn bran hydrolysates). The breads were then evaluated for structural analysis, texture, color, and sensory attributes.

Structural analysis of bread

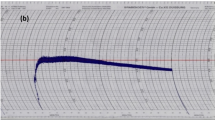

Fourier-transform infrared microscopy (FTIR)

The FTIR spectra of bread samples (T0, T1 and T2) was recorded in the wavenumber range of 4000 to 400 cm−1 using a Vertex 70 ATR-FTIR spectrometer with a resolution of 4 cm−1. The obtained spectra are shown in Figs. 1 and 2, and 3 for T0, T1 and T2 respectively. The IR spectra give distinct bonds indicating the particular functional groups. In the control sample T0 peaks were observed at 3278 cm−1 (O-H stretching), 2922 –2853 cm−1 (C-H stretching of alkanes), and 1742 cm−1 (C₌O stretching) which showed the presence of native polysaccharides, protein, and lipid composition of wheat flour as illustrated in Fig. 1. For T1, a similar broad O-H band was appeared at 3278–3378 cm−1 as shown in Fig. 2, but with higher intensity, indicates enhanced hydrogen bonding due to the release of polysaccharides and phenolic compounds. The peak at 1634–1418 cm−1 indicated the aromatic C = C and N–O stretching and confirmed the presence of phenolic structures. However, carbohydrate-associated peaks were observed at 1100–1000 cm−1 and showed polysaccharide dominance. In T2, a reduced transmittance in the O–H region at 1200–900 cm−1, along with enhanced C–O stretching bands was observed which indicates a greater contribution of carbohydrate-rich compounds from corn bran. Moreover, in T2 sharper bands at 1653 cm−1 were displayed, attributed to amide I with C = O stretching, and stronger protein to carbohydrate interactions were indicated as shown in Fig. 3. Minor peaks around 690–810 cm−1 in all samples were observed, corresponding to C–H bending and possible traces of halo compounds. Thus, relative to the control (T0), both T1 and T2 revealed significant structural alterations, with T1 exhibiting more intense phenolic-associated absorptions, whereas T2 displayed stronger polysaccharide-related vibrations. These results affirm that the incorporation of bran hydrolysates through hydrothermal processing enriched the bread matrix with diverse functional groups, potentially improving its nutritional value and antioxidant capacity. These results align with the findings of Ikram et al.28, who reported similar FTIR patterns in bread samples.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM)

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) produces highly magnified images to examine the size, shape, composition, and surface features of materials. In this study, SEM was used to observe the microstructure of breads containing hydrolyzed wheat and corn bran at 1, 3, and 5 μm. The control bread (T0) showed a well-developed porous gluten network essential for softness. T1 exhibited a finer structure with a rough surface, whereas T2 showed a rough texture with small holes and bran clusters that disrupted the gluten network, potentially modified the overall texture as shown in Fig. 4. These results align with previous findings of Lai et al.29 which showed that wheat bran modifies gluten distribution and surface roughness through fiber–starch interactions. Li et al.30 further suggested that wheat bran hydrolysate particles, while disrupting the network, can also enhance gluten aggregation.

Textural analysis of bread

Texture is a crucial determinant of bread quality and acceptability. The hardness of bread samples was evaluated using a texture analyzer (Mod. TA.XT.Plus, Stable Micro Systems, UK). Measurements were taken in triplicates after storage at room temperature, excluding the first and last three slices of bread. The mean results showed that the hardness of the control bread (T0) was 147.12 ± 0.13 N, while for T1 and T2 were 230.87 ± 0.20 N and 218.52 ± 0.28 N, respectively as shown in Table 5. However, wheat bran hydrolysates produced bread (T1) with a firm texture, whereas corn bran hydrolysates resulted in moderate hardness in bread (T2) with improved stability.

Color analysis of bread

Bread color is another quality attribute that strongly influences consumer acceptability and product appeal. In baking, color analysis of crust and crumb serves as an essential quality control measures since it reflects both visual attractiveness and baking efficiency31. In the current research, the effect of wheat and corn bran hydrolysates on bread color was evaluated and the values of L* a* and b* of bread are shown in Table 6. The mean results of T0 samples for L* a* and b* values were 65.32 ± 0.07, 8.08 ± 0.03, and 30.81 ± 0.05 respectively. Bread with wheat bran hydrolysates (T1) showed that mean values of L* were 63.45 ± 0.02, a* 8.45 ± 0.04, and b*33.92 ± 0.02. However, in corn bran hydrolysate bread (T2) L* a* and b* values were 72.85 ± 0.05, 8.24 ± 0.07, and 20.45 ± 0.07 respectively. These findings are consistent with the results of Singh et al.32 who reported comparable L* a* and b* values for bread made with wheat bran. The results of current research showed that bread color is influenced by hydrothermal treatment which modifies pigment interactions and subsequently impacts the sensory attributes and overall consumer acceptability of the bread.

Sensory evaluation

Sensory evaluation is a scientific method in which trained judges evaluate the food product on the basis of color, flavor, appearance, texture, taste, and overall acceptability by using their senses such as hearing, sight, smell, taste, and touch. Judges donated the score according to the 9-point hedonic scale. The mean results of sensory evaluation of bread prepared with wheat and corn bran hydrolysates are presented in Table 7. The control bread T0 showed the lowest scores for all sensory attributes. The mean values for colour, flavor, taste, texture and overall acceptability for T0 were 7.80 ± 0.13, 7.62 ± 0.26, 7.60 ± 0.33, 7.49 ± 0.68 and 7.46 ± 0.15. T1 showed that the mean values for colour 8.20 ± 0.13, flavor 8.63 ± 0.12, taste 8.34 ± 0.14, texture 8.37 ± 0.11, and overall acceptability were 8.58 ± 0.25. These results indicate that the addition of wheat bran hydrolysates enhanced the sensory appeal of bread, with higher flavor and taste scores likely due to the release of bioactive compounds and flavor precursors during hydrolysis. However, the mean values for colour, flavor, taste, texture and overall acceptability for T2 were 7.99 ± 0.12, 7.95 ± 0.15, 8.29 ± 0.23, 8.33 ± 0.17 and 8.18 ± 0.40 respectively. In a previous study, Khan et al.33 determined the sensorial properties of chapatti prepared with whole wheat flour and the results were in line with our current findings.

Conclusion

This study showed that the wheat and corn bran hydrolysates exhibit improved biochemical and functional properties making them valuable functional food ingredients. Moreover, FTIR and SEM analyses revealed structural modifications in the gluten matrix, while sensory evaluation indicated greater acceptability for wheat bran hydrolysate bread. Overall, the findings suggest that wheat and corn bran hydrolysates can be effectively utilized to develop antioxidant and nutrient rich bakery products, thereby supporting consumer health and promoting sustainable bran utilization.

Data availability

Although adequate data are presented in tables and figures, the authors declare that additional data will be made available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Refrences

Reddy, M. P. et al. Chemistry of Macro-and micronutrients. In Colored Cereals 96–118 (CRC, 2025).

Tanklevska, N., Petrenko, V., Karnaushenko, А. & Melnykova, К. World corn market: Analysis, trends and prospects of its deep processing (2020).

Saleh, A. S., Wang, P., Wang, N., Yang, S. & Xiao, Z. Technologies for enhancement of bioactive components and potential health benefits of cereal and cereal-based foods: research advances and application challenges. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 59(2), 207–227 (2019).

Lu, S. et al. Optimizing irrigation in arid irrigated farmlands based on soil water movement processes: knowledge from water isotope data. Geoderma 460, 117440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2025.117440 (2025).

Akin, M. et al. Valorization and functionalization of cereal-based industry by-products for nutraceuticals. Nutraceutics agri-food by-products 173–222 (2025).

Deepak, T. S. & Jayadeep, P. A. Prospects of maize (corn) wet milling by-products as a source of functional food ingredients and nutraceuticals. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 60(1), 109–120 (2022).

Hussain, M. et al. Biochemical properties of maize Bran with special reference to different phenolic acids. Int. J. Food Prop. 24(1), 1468–1478 (2021).

Waddell, I. S. & Orfila, C. Dietary fiber in the prevention of obesity and obesity-related chronic diseases: from epidemiological evidence to potential molecular mechanisms. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 63(27), 8752–8767 (2023).

Xin, W. et al. Genome-Wide association studies identify OsNLP6 as a key regulator of nitrogen use efficiency in rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.70296 (2025).

Tufail, T. et al. A retrospective on the innovative sustainable valorization of cereal Bran in the context of circular bioeconomy innovations. Sustainability 14(21), 14597 (2022).

Das, N., Jena, P. K., Padhi, D., Kumar Mohanty, M. & Sahoo, G. A comprehensive review of characterization, pretreatment and its applications on different lignocellulosic biomass for bioethanol production. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 13(2), 1503–1527 (2023).

American Association of Cereal Chemists. Approved Methods Committee. Approved Methods of the American Association of Cereal Chemists Vol. 1 (American Association of Cereal Chemists, 2000).

Turkmen, F. U., Takci, H. A. M. & Sekeroglu, N. Total phenolic and flavonoid contents, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of traditional unripe grape products. Indian J. Pharm. Educ. Res. 51(3s2), s489–s493 (2017).

Waleed, M. et al. Structural and nutritional properties of psyllium husk arabinoxylans with special reference to their antioxidant potential. Int. J. Food Prop. 25(1), 2505–2513 (2022).

Chen, X., Sun, K., Zhuang, K. & Ding, W. Comparison and optimization of different extraction methods of bound phenolics from Jizi439 black wheat Bran. Foods 11(10), 1478 (2022).

Hussain, M., Saeed, F., Niaz, B., Imran, A. & Tufail, T. Biochemical and structural characterization of ferulated arabinoxylans extracted from nixtamalized and Non-Nixtamalized maize Bran. Foods 11(21), 3374 (2022).

Chandra, S. et al. Assessment of total phenolic and flavonoid content, antioxidant properties, and yield of aeroponically and conventionally grown leafy vegetables and fruit crops: A comparative study. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2014(1), 253875 (2014).

Medina-Jaramillo, C., Gomez-Delgado, E. & López-Córdoba, A. Improvement of the ultrasound-assisted extraction of polyphenols from Welsh onion (Allium fistulosum) leaves using response surface methodology. Foods 11(16), 2425 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Effects of wheat oligopeptide on the baking and retrogradation properties of bread rolls: evaluation of crumb Hardness, moisture Content, and starch crystallization. Foods 13(3), 397 (2024).

Bouaziz, F., Ben Abdeddayem, A., Koubaa, M., Ghorbel, E., Chaabouni, E. & R., &, S Date seeds as a natural source of dietary fibers to improve texture and sensory properties of wheat bread. Foods 9(6), 737 (2020).

Javed, M., Ahmed, W., Shahbaz, H. M., Rashid, S. & Javed, H. TechnoFunctional Assay and Quality Assessment of Yogurt Supplemented with Basil Seed Gum Powder 65 (Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology, 2022).

Sethi, S., Joshi, A., Arora, B. & Chauhan, O. P. Chemical composition of foods. In Advances in Food Chemistry: Food components, Processing and Preservation (1–37). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore. (2022).

Liu, Y., Zhang, H., Yi, C., Quan, K. & Lin, B. Chemical composition, structure, physicochemical and functional properties of rice Bran dietary fiber modified by cellulase treatment. Food Chem. 342, 128352 (2021).

Afangide, C. S., Orukotan, A. A. & Ado, S. A. Proximate composition of corn Bran as a potential substrate for the production of Xylanase using Aspergillus Niger. J. Adv. Microbiol. 12(3), 1–4 (2018).

Hajam, Y. A., Lone, R. & Kumar, R. Role of plant phenolics against reactive oxygen species (ROS) induced oxidative stress and biochemical alterations. In Plant Phenolics in Abiotic Stress Management (125–147). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore. (2023).

Wang, X. J. et al. Purification and evaluation of a novel antioxidant peptide from corn protein hydrolysate. Process Biochem. 49(9), 1562–1569 (2014).

Zhu, K., Zhou, H. & Qian, H. Antioxidant and free radical-scavenging activities of wheat germ protein hydrolysates (WGPH) prepared with alcalase. Process Biochem. 41(6), 1296–1302 (2006).

Ikram, A., Saeed, F., Arshad, M. U., Afzaal, M. & Anjum, F. M. Structural and nutritional portrayal of rye-supplemented bread using fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and scanning electron microscopy. Food Sci. Nutr. 9(11), 6314–6321 (2021).

Lai, S. et al. Micronization effects on structural, functional, and antioxidant properties of wheat Bran. Foods 12(1), 98 (2022).

Li, C. et al. Enhancing gluten network formation and Bread-Making performance of wheat flour using wheat Bran aqueous extract. Foods 13(10), 1479 (2024).

Olakanmi, S. J., Jayas, D. S. & Paliwal, J. Applications of imaging systems for the assessment of quality characteristics of bread and other baked goods: A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 22(3), 1817–1838 (2023).

Singh, M., Liu, S. X. & Vaughn, S. F. Effect of corn Bran as dietary fiber addition on baking and sensory quality. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 1(4), 348–352 (2012).

Khan, M. A. et al. Effect of yeast on functional and rheological characteristics of whole wheat flour and its effect on quality of Chapati. J. Food Sci. Technol. 60(9), 2385–2392 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hamna Zafar1, Farhan Saeed1, Bushra Niaz1, Amara Rasheed1, Shokhjakhon Akhmedov2, Ilmira Jumaniyazova3, Faiyaz Ahmed4, Muhammad Afzaal1, Fakhar Islam1,5, Abdela Befa Kinki-all the authos have take part equally.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zafar, H., Saeed, F., Niaz, B. et al. Biochemical and structural attributes of wheat & corn bran hydrolysates in relation to their end use-quality. Sci Rep 16, 836 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30461-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30461-z