Abstract

Ergot alkaloids produced by the fungus Claviceps purpurea pose significant risks to agriculture and human health. This study systematically investigates the pathogenicity of C. purpurea, analyzing five strains for their proteomic profiles, which revealed genetic variability in size and GC content. We identified proteins localized in various cellular compartments, contributing to our understanding of essential cellular processes. A focus on potential drug targets led to the identification of Alpha-N-acetylglucosaminidase, a hydrolase with significant mass and functional relevance, despite not matching a UniProt entry. The 3D structure prediction confirmed its integrity, making it a suitable target for further analysis. Molecular docking identified ligands CID:51,535,944 and CID:145,242,255 with strong binding affinities to Alpha-N-acetylglucosaminidase, highlighting interactions with key residues like TRP138, ARG651. Molecular docking interactions were validated and showed consistency through MD simulation analyses with greater RMSD, RMSF and PL contacts. This research enhances our understanding of C. purpurea, offering insights into its genetic diversity and cellular mechanisms while identifying promising therapeutic targets. The findings contribute to strategies for mitigating the economic and health impacts of C. purpurea infections, paving the way for innovative interventions in sustainable agriculture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The varied group of mycotoxins known as ergot alkaloids, which are generated from indoles, have actions against bacteria, nematodes, insects, and mammals. Rather than accumulating a single route product, many fungi produce distinct, frequently distinctive profiles of ergot alkaloids. The inefficiencies in the system that cause some intermediates to accumulate or divert into shunts along the pathway are the cause of these ergot alkaloid profiles. It is possible that the inefficiency in creating certain ergot alkaloid profiles was chosen to accumulate a variety of ergot alkaloids, which could aid the fungus that is producing them in various ways1. Ergot alkaloids are generated by several fungi across two orders. Ergot alkaloids are produced by several fungi belonging to the Clavicipitaceae (order Hypocreales). These include several fungi that live as endophytic symbionts in grasses, such as several ergot fungi in the genus Claviceps2,3,4 and several fungi in the genera Epichloë and Neotyphodium5.

Fungi belonging to the Claviceps genus generate ergot, a disease that affects grains and grasses. Claviceps fusiformis in pearl millet (Africa, Asia), C. africana in sorghum (global), and Claviceps purpurea in temperate zones are of special significance. Young, typically unfertilized ovaries are infected by the fungi, which replace the seeds with dark mycelial lumps called sclerotia. Ergot has been known in Europe since the early Middle Ages in winter rye6. A diverse range of fungus create mycotoxins, which are metabolites of fungal toxin. The mycotoxins of greatest concern, such as aflatoxins, ochratoxins, and fumonisins, are produced by a number of species of Aspergillus, Penicillium, and Fusarium. But ergot alkaloids (EAs), a class of mycotoxins whose effects have been recognized since the Middle Ages, are produced by the plant pathogen Claviceps genus (ergotism)7. The most significant of the numerous Claviceps species is Claviceps purpurea, which is known to infect over 400 species of monocotyledonous plants, grasses, and commercially significant cereal grains like rye, wheat, triticale, barley, millet, and oat8.

Ergot is a disease that affects grasses and grains and is caused by fungi belonging to the Claviceps genus. Claviceps fusiformis in pearl millet (Africa, Asia), C. africana in sorghum (global), and C. purpurea in temperate regions are noteworthy species. When fungus infect young, usually unfertilized ovaries, they produce dark mycelial lumps called sclerotia in place of seeds. Ergot was first identified in winter rye in Europe in the early Middle Ages6. The Claviceps genus is notable for producing ergot alkaloids (EAs), a family of mycotoxins known to cause ergotism since the Middle Ages. Mycotoxins are metabolites of fungal toxins and are produced by a variety of fungus7. With its ability to infect more than 400 monocotyledonous plant species, including essential cereal grains like rye, wheat, triticale, barley, millet, and oat, C. purpurea is a particularly significant Claviceps species8.

Sensitive pasture and wild grasses are essential for the start of the life cycle of C. purpurea in the spring. Their feather-like stigmas, which are skilled at capturing ascospores, are the target of windborne ascospores9. Within a day, the first inoculum which consists of ascospores germinates and infects the ovary. The hyphae form a highly specialized host-pathogen connection akin to pollination dynamics as they selectively colonize the ovary when they reach the rachilla, the apex of the ovary axis10. A characteristic stroma is formed in the infected ovary: haploid, one-celled conidia that secrete a viscous “honeydew.” Insects are drawn to this sugary material, especially flies and moths. The main source of secondary inoculum that infects cereals is ergot-infected wild grasses in or close to fields. The window of opportunity for infection is extended by variables that delay pollination, such as cool, rainy weather, and resistance to C. purpurea usually appears a few days after fertilization. The infection process is repeated on cereals and is similar to that reported for pasture and wild grasses. Sclerotria can grow in multiples on a single head of rye and have a maximum length of 4–5 cm. The sclerotium protects the fungal mycelium from UV light, desiccation, and other environmental hazards. It is made up of a whitish mycelial tissue containing storage cells and an outer cortex that is darkly pigmented. Claviceps can live and overwinter thanks to these structures, called sclerotia10.

Considering the multifaceted challenges posed by the C. purpurea fungus and its potent mycotoxins, our study employs a comprehensive experimental design aimed at elucidating key aspects of its biology and pathogenicity. Through systematic data retrieval and the generation of a core proteome, we aim to identify conserved proteins and delve into the intriguing variability of ergot alkaloid profiles across strains. The identification of non-homologous proteins will contribute to understanding the unique adaptations of different isolates11. Furthermore, our investigation into the subcellular location and essentiality of these proteins aims to unravel the intricate host-pathogen interactions. As we progress to identify potential drug candidates, our study seeks to contribute novel insights into combating the economic and health impacts of C. purpurea. The subsequent steps, including 3D structure prediction, validation, and molecular docking analyses, will provide a deeper understanding of candidate proteins, offering a promising avenue for targeted therapeutic interventions12. Through these endeavors, we aspire to contribute to the development of resilient crops and effective strategies against the scourge of ergot fungus, addressing both current challenges and future uncertainties in agricultural sustainability. This comprehensive approach reflects our commitment to advancing scientific knowledge and fostering sustainable solutions in the face of evolving agricultural and environmental complexities.

Recent advances emphasize the utility of subtractive genomics for drug target discovery in diverse pathogens, as demonstrated in studies against Cronobacter sakazakii and Mycobacterium avium for neonatal infections and tuberculosis, respectively13. A 2025 review further highlights the evolution of this approach when combined with structure-based docking and multi-omics strategies using tools like BLAST, AutoDock Vina, and machine learning for target prioritization14. In the context of Claviceps purpurea, which poses both agronomic and toxicological threats, recent transcriptomic analysis of infected wheat revealed early induction of defence pathways including chitinases and receptor kinases in host tissues15. Additionally, genome sequencing of multiple C. purpurea isolates has unveiled structural genomic rearrangements impacting ergot alkaloid biosynthesis14. This updated context underscores the relevance and timeliness of our computational pipeline to identify fungal targets and design prospective inhibitors.

A schematic representation of the subtractive genomics approach: data retrieval, core proteome generation (OrthoFinder), human non-homologous protein filtering (BlastP), subcellular localization (Wolf PSORT), essential gene prediction (Geptop 2.0), druggability analysis (DrugBank + ARG-ANNOT), 3D modeling (SwissModel), validation (PROCHECK), docking (PyRx), and MD simulation (Desmond).

Materials and methods

The retrieval of data

Five strains of C. purpurea were recovered using National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), and they are as follows: GCA_018360975.1, GCA_018360845.1, GCA_029405325.1, GCA_029405515.1, and GCA_029405315.1. Three of the five strains’ proteomes were unavailable on NCBI. The following strains are among them: (LM72), (LM60), and (LM04) GCA_029405325.1, GCA_029405515.1, and GCA_029405315.1. The Augustus v3.4.516 tool was utilized to obtain the proteomes of these three genomes. Fusarium graminearum was the model organism employed in Augustus because it is more similar to C. purpurea in its status as a plant pathogen. Another fungal plant pathogen that targets wheat and barley is Fusarium graminearum17. The soft-masking feature was employed in Augustus. A full gene model was employed, and genes were predicted on both strands. Neither the projected sequence range nor any extrinsic information were provided.

Finding non-homologous proteins and creating a core proteome

OrthoFinder is a well-known orthology analysis program that finds orthologous groups in different species using a graph-based approach. It provides a trustworthy method of determining orthology by generating a similarity matrix and identifying orthologous groups using the Markov Cluster algorithm18. The OrthoFinder tool was used to identify orthologous proteins and generate core proteomes for five different strains of C. purpurea. To stop autoimmunity, the medication candidate must not be similar to human proteins. Following acquisition of the core proteome, the BlastP method was used to compare it to the host proteome database with a default p-value of 0.05. By comparing protein sequences to a protein database and evaluating sequence similarity, the program BlastP locates homologous proteins19. Therefore, only proteins with the least level of host identity were retrieved in order to avoid autoimmune reactions or high drug toxicity to host cells.

Subcellular localization and essentiality identification

The Wolf PSORT program was used to predict the subcellular localization of the proteins that OrthoFinder and BlastP studies had determined to be conserved and non-homologous to the host (human)20. According to Horton et al. (2007), Wolf Psort is a computational method that predicts the subcellular location of proteins and provides details on their cellular compartmentation20. The cytoplasmic proteins with the best statistical results were chosen for additional examination. Top and statistically significant proteins were included in the selection process, which was based on statistical factors such compartment, score, and rank. Following the identification of the subcellular locations of proteins using Wolf Psort, the web server Geptop 2.0 was used to predict the essential genes of the C. Purpurea strains21. Only the most important genes were chosen based on the essentiality score and class that Geptop 2.0 provided. Geptop 2.021 provides a platform for essential gene discovery across bacterial species by integrating orthology and phylogeny and comparing query protein sets with experimentally determined essential gene datasets from the DEG (Database of Essential Genes) database22.

Identification of drug candidates

The substantial increase in drug resistance and decline in antibiotic efficacy provide a number of difficulties in the treatment of infectious diseases. The pathogen’s entire proteome was analyzed using the ARGANNOT V6 (Antibiotic Resistance Gene-ANNOTation V6) tool23 to identify new resistance protein sequences. It is composed of protein sequences that have been demonstrated through experimentation to be resistant to a variety of antibiotic classes, including trimethoprim, fosfomycin, aminoglycosides, beta-lactamases, glycopeptides, sulfonamide, and rifampicin23. After that, the protein fasta sequences that had been shortlisted were BLASTp against the ARG-ANNOT V6 database’s resistance proteins using a threshold of 0.0000124. Similarly, several proteins from ARG-ANNOT were evaluated with BLASTp against the DrugBank database25 with an E-value of 10-e5 to determine their potential as therapeutic targets, which ultimately resulted in the discovery of additional targets. The proteins were analyzed using the FDA-approved custom drug target dataset. Proteins were considered good candidates for drug development if they shared ≥ 80% similarity with entries in the FDA-approved DrugBank database.

3D structure prediction & validation

The Swiss-Model tool, also referred to as the structure modeling server, was used to create the three-dimensional structure of the finalized and shortlisted protein26. The structural prediction was based on an already-predicted model, M1W3F7.1.A. Secondary structure was predicted by PSIPRED27 and for tertiary evaluation PROCHECK was utilized28. SAVES server was utilized to verify the 3D predicted structural analysis and verification. The 3D modelled structure was further refined and modified using the Galaxy Refine web service. Before employing molecular dynamics for structural reassembling and overall structural evaluation, the Galaxy Refine server reshapes the side chain29.

Ligand library preparation

A database of 3,000 naturally occurring drug-like inhibitors library from ChemDiv28 was downloaded in 2D sdf for screening against the selected receptor at the same predicted binding site. Inhouse built python script was used for ligand conversion to generate optimized 3D conformations of these 2D compounds. That python script used RDKit’s30 Chem and AllChem modules to support chemical structures and to run ETKDGv3 method. The ligand libraries were taken apart and used in smaller libraries in PyRx. Universal force field (UFF) and steepest descent (DS) were used to minimize the ligands.

Molecular docking

The selected protein was processed to make it an ideal receptor for molecular docking prior to running the molecular docking simulation. UCSF ChimeraX31 version 2014.0901 was used to exclude add polar hydrogens, addition of charges, conversion of non-standard residues, and the web server DoGSiteScorer32 predicted the receptor’s active site. The PyRx tool33 was employed for docking. In order for the program to solely bind ligands in that particular active site throughout the process, the top predicted active site was chosen in PyRx as site specific docking protocol. Using binding affinity (kcal/mol) and RMSD values, top compounds were retrieved for further analyses. Additionally, 2D interaction and binding poses analyses for top hits were performed using the Discovery Studio v 2024 client and Pymol34,35.

ADME and toxicity profiling

To assess the pharmacokinetic profiles of the top selected ligand candidates, ADME (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion) properties were calculated using SwissADME36. Physicochemical parameters relevant to drug-likeness were extracted, including molecular weight (MW), logP (octanol-water partition coefficient), number of hydrogen bond donors (HBD), and hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA). These properties were evaluated based on Lipinski’s Rule of Five, which postulates that, for optimal oral bioavailability, a compound should have. So, ADME and toxicity profiling results were used to screening the top hits for drug-like and non-toxic candidates to subject them further into MD simulations.

MD simulation

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations were performed using Desmond37 for 100 ns to evaluate the stability of selected protein-ligand complexes. Following system preprocessing, optimization, and minimization, MD modeling was employed to assess complex stability. Energy minimization was conducted using the OPLS_2005 force field38, and the systems were solvated in a 10 Å periodic box with TIP3P water molecules39. To mimic physiological conditions, counterions and 0.15 M NaCl were added as needed to neutralize the systems. Simulations were conducted under the NPT ensemble at 300 K temperature and 1 atm pressure. Each system underwent a relaxation process prior to the production run. Trajectory data were saved at 40 ps intervals throughout the simulation for subsequent analysis.

Results

Data identification

The proteomes of five C. purpurea strains were obtained from the NCBI’s GenBank database40 (Table 1). Moreover, an overall workflow of the study is depicted in Fig. 1.

Genomic subtraction

To identify potential therapeutic targets in Claviceps purpurea, a systematic genomic subtraction pipeline was implemented. Starting with the complete set of proteins from five C. purpurea strains (as listed in Table 2), a core proteome of 6,249 conserved proteins was generated. Subsequent filtering against the human proteome revealed 575 non-homologous proteins, eliminating those likely to share homology with host proteins. Subcellular localization analysis via WoLFPsort further refined the dataset, with notable enrichment in mitochondria (482), cytoplasm (382), and peroxisomes (152) (Table 3), along with smaller fractions in the membrane, cytoskeleton, and vacuole compartments. Among these, cytoplasmic proteins were prioritized due to their accessibility and critical functional roles in pathogen survival. 69 proteins were predicted to be essential for fungal survival, highlighting their potential as critical intervention points. Further screening against resistance-associated protein databases identified 10 proteins associated with known resistance mechanisms. Finally, only one protein displayed high similarity and interactions with FDA-approved drug targets in the DrugBank database, indicating its druggability and relevance for downstream modeling and docking studies. That candidate protein was revealed to be Alpha-N-acetylglucosaminidase (NAGLU). Despite the absence of a direct UniProt match, structural and functional similarity to entry M1W3F7 suggested this hydrolase plays a pivotal role in the pathogen’s biology. Its distinctiveness from human homologs and druggable profile underscores its suitability as a novel therapeutic target against C. purpurea.

3D structure prediction & validation

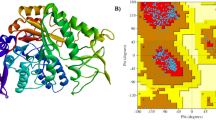

The predicted 3D structure by Swiss-Model is given in (Fig. 2A). The Ramachandran plot & its statistics obtained by PROCHECK shows that majority of the residues were in energetically favorable regions and the G-factor suggest that unusualness or out-of-ordinariness of various properties is with in an acceptable range with a 91.4%, but multiple residues were also falling in unfavorable regions. So, galaxy refine was used for a brief refinement of the predicted structure. It refined the structure, added missing residues, and produced a structure where the acceptable regions had 93.9% residues (Fig. 2B).

ADME and toxicity profiling

After the docking was completed, before going any further the ADME and toxicity criteria was used to screen the top compounds based on best ADME and toxicity values. It was done to select the top compounds showing stronger binding affinities before presenting them. As shown in Table 4, most compounds conformed to Lipinski’s Rule of Five, with molecular weights ranging between 382.45 and 478.54 Da. All ligands had acceptable logP values (< 5), indicating favorable lipophilicity and potential for membrane permeability. The number of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors also fell within the recommended limits for oral drug-likeness in most cases.

Molecular docking

Following the protein’s preparation as a receptor for the molecular docking process, DoGSiteScorer first predicted the active site for ligand binding. To guarantee that the best druglike compounds were selected from the results, extremely stringent criteria were put in place to choose the top hits following the docking process after ADME and toxicity screening. Statistics like RMSD values and the binding affinity (kcal/mol), were taken into account. A 3D visual of the receptor and top ligands bounded to it has been depicted in Fig. 3A. A stronger receptor-ligand complex is indicated by a lower binding affinity. CID:145,242,255 showed a greater and stronger binding affinity of −7.3 with the NAGLU receptor and key residues of this ligand interaction are TRP138, ARG651 (Fig. 3B). While CID:51,535,944 showed more stronger binding affinity of −7.6 and key residues of this ligand interaction are ASP98, LYS141, ASP142, GLU144, ARG651. In addition to the top two compounds, several other ligands demonstrated promising interactions. CID:135,981,986 (–7.2 kcal/mol) repeatedly formed hydrogen bonds with ARG651 and van der Waals interactions with TRP137 and GLN139, suggesting consistent anchoring near the catalytic groove. CID:46,883,788 (−7.0 kcal/mol) showed a diverse interaction network including pi-pi stacking with TRP138 and hydrogen bonding with PHE95 and ASP142. CID:129,011,098 and CID:11,004,289 both showed binding affinities of −6.8 kcal/mol and engaged in multiple hydrogen bonds and ionic interactions with core residues such as ARG651, ASP142, and LYS658. Even lower-ranked ligands like CID:102,370,900 and CID:46,887,866 maintained significant polar and non-polar interactions within the binding pocket, confirming their structural compatibility. These observations collectively highlight a consistent engagement of all top ligands with catalytically important residues, further validating the predicted binding site and reinforcing the druggability of the NAGLU receptor. Binding affinities (kcal/mol) and interacting residues of all the top ligands are given in Table 5. Then the top two ligands based on ADME, toxicity, and docking were subjected to MD simulations.

(A) Binding site area with a transparent surface predicted by DoGSiteScorer is shown above in the Figure. (B) A complex with all of the ligands in the binding site of receptor is displayed drawn via PyMol v3.6. The 2D interactions of top 2 selected ligands for MD simulations drawn by Discovery studio client 2025 (CID: 145242255, CID: 51535944).

MD simulation

CID:51,535,944

MD simulation of 100 ns was used to examine the binding sites of the selected compounds against the receptor to verify the stability of the protein-ligand complexes. To investigate complicated deviations and general structural changes during the simulation, the RMSD of the carbon alpha (C) atoms was calculated. For CID:51,535,944, the RMSD began at approximately 3.0 Å and increased to 8.0 Å at approximately 40 ns, staying in this range till 100 ns exhibiting very stable RMSD. Moreover, the ligand atoms’ RMSD was lower than the protein atoms’ RMSD (Fig. 4A). Root-mean square fluctuations (RMSF) values have been used to quantify the fluctuations of the proteins when they are bound to the ligands. Comprehensive details on each protein residue’s mobility and flexibility during the simulation period are provided by RMSF values. Considering the predicted RMSF values during the simulation, most of the protein residues for CID:51,535,944 changed, although not by more than 2.0 Å indicating a stability in the overall protein’s structure in the presence of the ligand. Nonetheless, the RMSF values were higher in the loop regions, which were around 4.0 Å (Fig. 4B). The MD Simulation analysis revealed that the most important kinds of interactions between the ligands and the protein were ionic, hydrogen, and hydrophobic bonds. These interactions maintain and regulate the functional properties of the protein-ligand complex. With CID:51,535,944, residues ASN-25, ARG-26, GLY-30, HIS-93, ASP-98, ARG-99, and LYS-145 formed hydrogen bonds (Fig. 4C). Moreover, HIS-93 and ASP-98 showed consistent exposure and interaction to ligand atoms from docking to MD simulations (Fig. 4D).

(A) The RMSD of the complex CID:51,535,944 calculated in 100 ns simulation. (B) The RMSF of the residues in the presence of complex receptor and CID:51,535,944. (C) The interaction fraction between the receptor and the CID:51,535,944 ligand during MD simulation. (D) 2D profile of major interactions of the receptor’s residues during the MD simulations.

CID:145,242,225

For CID:145,242,225, the RMSD began at approximately 3.6 Å and decreased to 3.0 Å at around sometime like 20 ns, indicating that ligand is exploring another binding conformation. After 20ns ligand exhibited an RMSD of 3.0 Å till a longer time upto 80ns exhibiting a greater range of stability. After that, it was stable from 80ns to 100 ns around 4.2 Å. Moreover, the ligand atoms’ RMSD was lower than the protein atoms’ RMSD (Fig. 5A). Root-mean square fluctuations (RMSF) values have been used to quantify the fluctuations of the proteins when they are bound to the ligands. Comprehensive details on each protein residue’s mobility and flexibility during the simulation period are provided by RMSF values. Considering the predicted RMSF values during the simulation, most of the protein residues for CID:145,242,225 changed, although not by more than 3.0 Å indicating a stability in the overall protein’s structure in the presence of the ligand. Nonetheless, the RMSF values were higher in the loop regions, which were around 5.6 Å and more just like the ligand CID:145,242,225 (Fig. 5B). The MD Simulation analysis revealed that the most important kinds of interactions between the ligands and the protein were ionic, hydrogen, and hydrophobic bonds. These interactions maintain and regulate the functional properties of the protein-ligand complex. With CID:145,242,225, residues GLY-139, ASP-142, GLN-650, ARG-651, and LYS-658 formed hydrogen bonds (Fig. 5C). Moreover, TRP-137, ASP-142, and ALA-654 showed consistent exposure and interaction to ligand atoms from docking to MD simulations (Fig. 5D).

(A) The RMSD of the complex CID:145,242,225 calculated in 100 ns simulation. (B) The RMSF of the residues in the presence of complex receptor and CID:145,242,225. (C) The interaction fraction between the receptor and the CID:145,242,225 ligand during MD simulation. (D) 2D profile of major interactions of the receptor’s residues during the MD simulations.

Binding free energy calculations (MMGBSA)

The MM/GBSA binding free energy calculations provided deeper insight into the thermodynamic stability of the ligand-receptor complexes. The binding energy (ΔG_bind) of the CID:145,242,225 complex was slightly more favorable (−42.73 kcal/mol) compared to CID:51,535,944 (−38.14 kcal/mol), indicating that CID:145,242,225 may form a more stable and energetically favorable complex with the NAGLU receptor. Decomposing the energy terms revealed that lipophilic interactions (ΔG_lipo) were the dominant stabilizing force in both complexes, contributing − 30.86 kcal/mol for CID:145,242,225 and − 24.21 kcal/mol for CID:51,535,944. This suggests strong hydrophobic packing of both ligands within the binding pocket. Van der Waals (vdW) interactions were also significantly stabilizing, contributing − 39.82 kcal/mol and − 42.87 kcal/mol for CID:145,242,225 and CID:51,535,944, respectively, supporting shape complementarity between ligand and protein. Coulombic interactions were moderately favorable in both cases, particularly for CID:51,535,944 (−9.75 kcal/mol), reflecting strong polar interactions such as salt bridges or ion pairing. However, solvation energy (Solv_GB) partially offset these gains with positive values (29.74 to 34.57 kcal/mol), which is typical as desolvation opposes binding. Interestingly, the covalent energy term was slightly higher for CID:145,242,225 (7.05 kcal/mol), which may indicate internal strain or torsional penalties within the ligand conformation. This is supported by the strain energy, which was notably higher for CID:145,242,225 (14.03 kcal/mol) compared to CID:51,535,944 (6.69 kcal/mol), possibly indicating greater induced fit or conformational rearrangement upon binding (Fig. 6). In summary, while both ligands show strong binding affinity based on MM/GBSA calculations, CID:145,242,225 displayed the more favorable overall ΔG_bind, largely driven by lipophilic and van der Waals interactions. However, its higher internal strain suggests CID:51,535,944 may offer a slightly more stable and conformationally compatible interaction profile for further optimization.

Hydrogen bonding

Hydrogen bond analysis conducted over the 100 ns molecular dynamics trajectory revealed that the both complexes consistently maintained 1 to 4 hydrogen bonds throughout most frames, with periodic surges of CID:145,242,225 reaching up to 6 and more hydrogen bonds, indicating stable yet flexible engagement with key residues within the receptor’s domains and substrate binding site. In comparison, the Receptor and CID:145,242,225 complex exhibited a denser and more sustained hydrogen bonding pattern, frequently maintaining 1 to 4 hydrogen bonds and occasionally peaking at 6 than CID:51,535,944, highlighting CID:145,242,225’s ability to form a robust and persistent interaction network within the active site of the receptor (Fig. 7). These observations confirm that CID:145,242,225 not only achieves high-affinity docking but also preserves continuous molecular recognition during dynamic simulations, a hallmark of high-performance inhibitors.

Radius of gyration

The radius of gyration (Rg) analysis was performed to evaluate the structural compactness and overall stability of the protein-ligand complexes throughout the simulation trajectory. For the CID:51,535,944, Rg values remained stable within a narrow range (27.5–28 Å), with minor to none fluctuations, indicating very consistent folding and compactness of the complex during the 100 ns simulation. Similarly, the CID:145,242,225 exhibited stable Rg values ranging between 27.75 and 28.25 Å, supporting the retention of structural integrity over time (Fig. 8). These findings align well with the observed hydrogen bonding patterns, where sustained interactions were maintained across the trajectory. The combined stability of both Rg and hydrogen bonding profiles supports the dynamic stability and conformational suitability of both ligands in binding to both target proteins under physiological conditions.

Radius of Gyration (Rg) plots of complexes over a 100 ns molecular dynamics simulation. The Rg values indicate the temporal compactness and structural stability of the protein-ligand complexes. Minor fluctuations throughout the trajectory suggest preserved folding and consistent conformational integrity upon ligand binding.

Solvent accessible surface area

The SASA profile of the CID:51,535,944 complex reveals a consistent solvent exposure throughout the 100 ns simulation period, with values ranging between ~ 31,500 − 32,500 Ų. These values suggest that the complex maintains a compact and solvent-stable conformation, with no significant structural expansion or collapse. The brief increase in SASA around 60 ns aligns with transient conformational changes likely associated with local side-chain rearrangements or loop movements, rather than global unfolding. The SASA trajectory for the CID:145,242,225 complex (Fig. 9) demonstrated an initial decrease in solvent exposure during the first 20 ns, stabilizing around ~ 31,500 Ų throughout the remainder of the 100 ns simulation. This suggests an early equilibration phase, followed by consistent compactness of the protein-ligand complex. No large deviations or erratic SASA spikes were observed, indicating the absence of significant structural unfolding or cavity collapse. These stable SASA values support a conformationally intact structure upon ligand binding. This overall stability in solvent exposure supports the findings from MD simulation analyses, Hbond analysis, and Rg analyses, reinforcing that both ligands do not disrupt receptor’s structural integrity in complex with them during the simulation.

Protein-ligand center-of-mass (CoM) distance analysis

The center-of-mass (CoM) trajectories were evaluated to quantify the persistence of ligand association within the binding cavity over the 100 ns simulation period. For the complex with CID:145,242,225, the CoM distance initiated near 20 Å, displaying only modest fluctuations (± 1.0 Å) throughout the trajectory and a gradual upward drift toward ~ 21 Å at the terminal frames (Fig. 10A). Such low-amplitude variation reflects a stable binding event wherein the ligand remains confined within the pocket without exhibiting any significant displacement or unbinding tendencies. The subtle drift observed toward the end of the trajectory is most plausibly attributed to intrinsic pocket breathing and local backbone flexibility rather than to loss of interaction, consistent with the stable hydrogen-bond occupancy and van der Waals interactions recorded during the simulation. In contrast, the complex formed with CID:51,535,944 maintained an initial CoM separation of approximately 26 Å, which remained largely constant up to frame 750, followed by a minor transient elevation near frame 950, after which the system stabilized again around the same distance until the end of the simulation (Fig. 10B). The absence of any sustained deviation or pronounced spikes beyond this range indicates that the ligand preserved a consistent spatial relationship with the protein throughout the simulation timeframe. Collectively, the CoM analyses confirm that both ligands retained strong and persistent interactions within their respective binding cavities, thereby corroborating the dynamic stability inferred from RMSD and MM/GBSA profiles.

Discussion

C. purpurea has a broad host range, encompassing over 400 distinct grass species, including grains and all forage grasses in temperate areas. Economically, the most important disease is rye (Secale cereale L.), a major crop in Germany, Scandinavia, Poland, Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine41. The biggest danger posed by ergot is not the yield drop, which occurs in commercial farming and typically ranges from 5% to 10%42, but rather the contamination of the harvest by poisonous alkaloids found in the sclerotia. All three primary categories of ergot alkaloids clavine alkaloids, D-lysergic acid and its derivatives, and ergopeptines are produced by C. purpurea; lysergic acid and its derivatives are not produced by C. africana43. Both humans and animals may experience serious health issues because of the alkaloids. Prior to the introduction of grain standards for ergot in the 19th century, sclerotia were ground up with rye grains and ingested because the majority of the flour was used for baking. The symptoms of chronic consumption are summed up as “ergotism.” The spread and heightened severity of the illness are influenced by various factors. Unused agricultural land harboring accumulated pathogenic elements of C. purpurea poses a specific risk. Despite contemporary plant-growing technologies minimizing soil tillage and other treatments, numerous concerns remain unanswered. Intensifying climate change, coupled with anthropogenic and technogenic influences, negatively impacts field biocenoses. Annually, C. purpurea infects 60% of winter grain crops in the Kirov region. Plants within rye biocenoses exhibit infection rates ranging from 0.2% to 5.0%44. Current grain production methods fall short of providing complete defense against ergot, and seed ingestion of sclerotia remains a challenge. Genetic research within the Secale sereale L. and C. purpurea system is intricate due to the pathogen’s unique biological characteristics and the complex process of infection loading required for donor resistance. Further constraints include the lack of data on the phenotypic and genetic makeup of populations within the genus Claviceps, as well as the absence of biochemical indicators of resistance. Notably, increased pollen production and fertility serve as significant biomarkers actively utilized in Germany. Researchers stress the importance of recurrent genotype testing for an accurate assessment of ergot resistance in S. sereale and C. purpurea, acknowledging the profound influence of the environment on pathogenesis45.

During our investigation, a thorough exploration of existing literature revealed a notable gap in genomic subtraction studies specifically focused on Rye and C. purpurea. Despite an exhaustive review of numerous studies, no comparable research elucidating the intricate genomic interactions between Rye and C. purpurea was identified. The scarcity of such studies emphasizes the pioneering nature of our research, positioning it as a distinctive contribution to the field. This gap in the literature underscores the significance of our work, as it not only provides novel insights into the biology and pathogenicity of C. purpurea but also addresses a critical knowledge void in the current scientific discourse. We anticipate that our research will serve as a foundational reference for future investigations in this underexplored intersection of genomics, plant pathology, and fungal biology.

Although direct subtractive genomics analyses between Secale cereale and C. purpurea remain limited in the current literature, several computational and transcriptomic investigations offer valuable comparative insights. For instance, Mahmood et al. (2020) employed a de novo transcriptome assembly approach in rye hybrids inoculated with C. purpurea, revealing key differentially expressed genes associated with defense pathways, including hormonal signaling and secondary metabolite biosynthesis46. Their work underpins the molecular defense framework in rye and indirectly supports the biological relevance of proteins identified through our subtraction-based proteomic strategy. Furthermore, Oeser et al. (2017) performed RNA-Seq analysis to examine the dynamic gene expression during rye-Claviceps infection. Their dual-host-pathogen profiling revealed how C. purpurea modulates host gene networks, particularly those linked to immunity, stress signaling, and metabolism, aligning with our focus on essential cytoplasmic proteins as candidate intervention points47. From a host perspective, Miedaner et al. (2008) examined genetic variation for ergot resistance across winter rye populations, confirming the existence of heritable resistance traits48. These findings underscore the importance of integrating pathogen-side drug target discovery, such as ours, with host-resistance breeding strategies for holistic disease management. Together, these studies validate the significance of computational pipelines in unraveling molecular targets in both host and pathogen systems. Our study not only complements this growing body of work but also adds a unique dimension by using subtractive genomics to pinpoint actionable fungal targets, particularly in under-explored plant-pathogen systems such as rye and C. purpurea.

The comprehensive analysis of C. purpurea strains undertaken in this study has shed light on key aspects of its biology and pathogenicity. The identification and comparison of proteomes from five distinct strains provided valuable insights into the genomic diversity of C. purpurea. Core protein identification ensures conserved functionality across strains, maximizing the utility of a single drug across multiple pathogen genotypes. The prediction of subcellular locations and essentiality of proteins using Wolf Psort and Geptop 2.0, respectively, contributed to our understanding of the functional roles of specific proteins within C. purpurea. The predominance of cytoplasmic proteins, along with the identification of proteins in membrane, mitochondria, peroxisome, cytoskeleton, and vacuole, suggests the multifaceted nature of the fungus’s cellular activities. Subcellular localization, particularly the selection of cytoplasmic proteins, enhances the likelihood of successful drug interaction, as these targets are more exposed and readily accessible to small molecules. The correlation between subcellular localization and essentiality is critical for unraveling the dynamics of host-pathogen interactions and potential targets for intervention. In the pursuit of drug targets, the identification of essential cytoplasmic proteins resistant to multiple antibiotics highlights potential candidates for therapeutic intervention. Essentiality analysis ensures that only functionally indispensable proteins are retained, increasing the probability that inhibiting the selected targets will halt pathogen survival. This multi-layered filtration enhances specificity, minimizes host cross-reactivity, and lays a strong foundation for successful structure-based drug design.

The subsequent analyses through DrugBank and ARGANNOT V6 databases led to the identification of an NAGLU protein as a promising drug target. The involvement of this protein in hydrolase activity suggests its potential role in the virulence or survival mechanisms of C. purpurea. This finding provides a foundation for further exploration and development of targeted therapies to combat the impact of ergot fungus. The 3D structure prediction and validation steps ensured the reliability of the chosen drug target. The analysis of the predicted structure, as represented by the Ramachandran plot and PROCHECK, indicated a structurally sound protein model. The refinement and validation through Galaxy Refine and SAVES server further strengthened the confidence in the predicted structure’s accuracy. These steps are crucial in ensuring the reliability of subsequent molecular docking analyses. Using ChemDiv’s natural library of compounds, filtration based on docking scores, ADME/Toxicity profiles, and key residue interactions was done, allowing objective prioritization of only the top-ranked ligands for further structural analysis and MD simulation.

Molecular docking simulations allowed the identification of two potential ligands, CID:51,535,944 and CID:145,242,255, exhibiting strong interactions with the NAGLU receptor. The formation of hydrogen bonds and other interactions with key residues underscores the potential efficacy of these ligands as inhibitors. The identification of NAGLU as a drug target offers a dual benefit. For agriculture, developing inhibitors against this protein could lead to treatments that protect rye crops from ergot infection, enhancing food security. Rather than selecting ligands arbitrarily, our study employed a systematic filtering process starting from 3,000 ChemDiv compounds and narrowing down candidates based on docking energy, receptor-ligand interaction stability, and pharmacokinetic properties.

To further validate the docking outcomes, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were conducted for 100 ns to evaluate the conformational stability of the ligand-bound complexes. The root mean square deviation (RMSD) profiles for CID:51,535,944 and CID:145,242,225 stabilized within 2.0–3.5.0.5 Å and 4.9–5.9 Å, respectively after the initial equilibration phase, confirming the structural integrity of the receptor-ligand assemblies. Notably, the RMSD of the ligands remained consistently lower than the protein backbone, indicating minimal displacement and strong binding conformity over time, which mechanistically supports the docking-based binding affinity observations. These findings affirm that the ligands do not destabilize the receptor, reinforcing their viability as small-molecule inhibitors targeting NAGLU in C. purpurea. The RMSF analyses revealed that the majority of the amino acid residues exhibited fluctuations below 3.0 Å for CID:51,535,944 and CID:145,242,225, particularly in structured α-helices and β-sheets. As expected, enhanced flexibility was observed in loop regions, reaching up maximum to 3.0 Å for both complexes, which may aid in adaptive binding conformations without compromising complex stability. This differential mobility supports the notion that the ligand interaction is dynamically tolerated within the receptor’s functional core, aligning with the static docking poses predicted earlier. These stability patterns bolster the pharmacological potential of the ligands under near-physiological dynamic conditions, indicating their promise in ergot suppression. These results were further supported by MM/GBSA binding energy calculations, which showed that CID:145,242,225 had a more favorable binding free energy (−42.73 kcal/mol), while CID:51,535,944 exhibited lower strain and slightly better conformational stability upon binding.

In-depth analysis of protein-ligand contacts throughout the simulation highlighted persistent hydrogen bonds and ionic interactions with catalytically and structurally relevant residues given in Sect. 5.3.1 and 3.5.2. These interactions were consistently maintained across simulation frames, reflecting strong and specific ligand anchoring within the active site. The Rg and SASA trajectories remained steady with only minor fluctuations affirming that ligand binding preserves protein structural integrity without triggering collapse or expansion. Together, these interlinked MD analyses construct a compelling narrative of structural stability, functional integrity, and consistent ligand engagement, thereby strengthening the mechanistic basis of our study.

The prevalence of stable non-covalent contacts under dynamic conditions confirms and extends the docking results, providing a more robust structural rationale for ligand efficacy. Although this study primarily aims to contribute to the development of crop-protective agents targeting C. purpurea, the dual role of the identified protein in ergot alkaloid biosynthesis suggests potential for broader applications. By disrupting this protein’s function in the fungus, agricultural fungicides could reduce ergot infections in rye, thereby improving crop yield and food safety.

While our computational approach provides a strong foundation for identifying druggable targets and potential inhibitors, experimental validation remains critical. Future work will focus on cloning and expressing the NAGLU protein for in vitro enzyme inhibition assays with the top-scoring ligands. Additionally, bioassays will be performed to evaluate the antifungal efficacy of these compounds in C. purpurea-infected rye under controlled conditions. These steps will confirm the inhibitory activity, assess phytotoxicity, and support the development of practical applications such as foliar fungicides or seed treatments. Additionally, mutagenesis and protein expression studies could help characterize the biological role of this enzyme in ergot alkaloid biosynthesis and pathogenicity. While our computational pipeline offers a robust framework for identifying druggable targets, it is limited by the accuracy of predicted protein structures and the lack of host-pathogen interaction modeling at the systems biology level. Expanding this work to include transcriptomic and metabolomic data from infected rye could offer deeper insights into the dynamic molecular interactions driving ergot pathogenesis and resistance.

Conclusion

This study employed a comprehensive in silico subtractive genomics and structure-based drug discovery pipeline to identify promising drug targets in Claviceps purpurea, the causative agent of ergot disease in rye. Through rigorous genomic filtering, we prioritized Alpha-N-acetylglucosaminidase (NAGLU) a non-homologous, cytoplasmic, and essential protein as a viable therapeutic target. A virtual screening of 3,000 natural compounds from the ChemDiv database yielded several high-affinity ligands, with CID:51,535,944 and CID:145,242,255 exhibiting the strongest binding affinities of −7.6 kcal/mol and − 7.3 kcal/mol, respectively. These lead compounds formed stable hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions with key active-site residues such as ARG651, GLU144, and TRP138. The results via 100 ns molecular dynamics simulations confirmed sustained binding within the active site, with minimal RMSD and RMSF fluctuations, stable hydrogen bonding patterns, and consistent engagement with catalytically relevant residues. These findings reinforce the therapeutic potential of the identified ligands and highlight NAGLU as a viable target for developing antifungal agents or agricultural fungicides. Future in vitro and in vivo validation will be critical to confirm the efficacy, safety, and practical applicability of these candidate molecules.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript information files.

Abbreviations

- ADME:

-

Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion

- ARG-ANNOT:

-

Antibiotic Resistance Gene-ANNOTation

- DEG:

-

Database of Essential Genes

- EAs:

-

Ergot Alkaloids

- HBD:

-

Hydrogen Bond Donor

- HBA:

-

Hydrogen Bond Acceptor

- MD Simulations:

-

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

- NAGLU:

-

Alpha-N-acetylglucosaminidase

- OPLS:

-

Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulations

- RMSD:

-

Root mean square deviation

- RMSF:

-

Root mean square fluctuations

- Rg:

-

Radius of Gyration

- SASA:

-

Solvent Accessible Surface Area

References

Panaccione, D. G. Origins and significance of ergot alkaloid diversity in fungi. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 251, 9–17 (2005).

Gröcer, D. & Floss, H. G. Biochemistry of ergot alkaloids—achievements and challenges. Alkaloids Chem. Biol. 50, 171–218 (1998).

Tudzynski, P., Correia, T. & Keller, U. Biotechnology and genetics of ergot alkaloids. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 57, 593–605 (2001).

Flieger, M., Wurst, M. & Shelby, R. Ergot alkaloids—sources, structures and analytical methods. Folia Microbiol. (Praha). 42, 3–30 (1997).

Panaccione, D. G. & Schardl, C. L. Molecular genetics of ergot alkaloid biosynthesis. In Clavicipitalean Fungi (eds White, J. F. et al.) 384–406 (CRC, 2003).

Miedaner, T. & Geiger, H. H. Biology, genetics, and management of ergot (Claviceps spp.) in rye, sorghum, and Pearl millet. Toxins (Basel). 7, 659–678 (2015).

Richard, J. L. et al. Mycotoxins: risks in plant, animal and human systems. CAST. Task Force Rep. 139, 101–103 (2003).

Haarmann, T., Rolke, Y., Giesbert, S. & Tudzynski, P. Ergot: from witchcraft to biotechnology. Mol. Plant. Pathol. 10, 563–577 (2009).

Mantle, P. G., Shaw, S. & Doling, D. A. Role of weed grasses in the etiology of ergot disease in wheat. Ann. Appl. Biol. 86, 339–351 (1977).

Tenberge, K. B. in Biology and Life Strategy of the Ergot Fungi. 40–71 (eds Ergot) (CRC, 1999).

Alhaidhal, B. A., Alsulais, F. M., Mothana, R. A. & Alanzi, A. R. In Silico discovery of druggable targets in citrobacter Koseri using echinoderm metabolites and molecular dynamics simulation. Sci. Rep. 14, 26776 (2024).

Alanzi, A. R., Alhaidhal, B. A. & Aloatibi, R. M. Identification of SIRT3 modulating compounds in deep-sea fungi metabolites: insights from molecular Docking and MD simulations. PLoS One. 20, e0323107 (2025).

Ahammad, I. et al. Subtractive genomics study for the identification of therapeutic targets against cronobacter sakazakii: A threat to infants. Heliyon 10, e30332 (2024).

Yu, L. et al. Efficient genome editing in claviceps purpurea using a CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoprotein method. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 7, 664–670 (2022).

Tente, E. et al. Reprogramming of the wheat transcriptome in response to infection with claviceps purpurea, the causal agent of ergot. BMC Plant. Biol. 21, 316 (2021).

Stanke, M. et al. AUGUSTUS: Ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W435–W439 (2006).

Imboden, L., Afton, D. & Trail, F. Surface interactions of fusarium graminearum on barley. Mol. Plant. Pathol. 19, 1332–1342 (2018).

Emms, D. M. & Kelly, S. OrthoFinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 20, 1–14 (2019).

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410 (1990).

Horton, P. et al. WoLF PSORT: protein localization predictor. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W585–W587 (2007).

Wen, Q-F. et al. Geptop 2.0: an updated, more precise, and faster Geptop server for identification of prokaryotic essential genes. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1236 (2019).

Zhang, R., Ou, H. & Zhang, C. DEG: a database of essential genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, D271–D272 (2004).

Solanki, V. & Tiwari, V. Subtractive proteomics to identify novel drug targets and reverse vaccinology for the development of chimeric vaccine against acinetobacter baumannii. Sci. Rep. 8, 9044 (2018).

Gupta, S. K. et al. ARG-ANNOT, a new bioinformatic tool to discover antibiotic resistance genes in bacterial genomes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 212–220 (2014).

Wishart, D. S. et al. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the drugbank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, D1074–D1082 (2018).

Schwede, T., Kopp, J., Guex, N. & Peitsch, M. C. SWISS-MODEL: an automated protein homology-modeling server. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3381–3385 (2003).

McGuffin, L. J., Bryson, K. & Jones, D. T. The PSIPRED protein structure prediction server. Bioinformatics 16, 404–405 (2000).

Pan, Y., Huang, N., Cho, S. & Mackerell, A. D. Consideration of molecular weight during compound selection in virtual target-based database screening. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 43, 267–272 (2003).

Heo, L., Park, H. & Seok, C. GalaxyRefine: protein structure refinement driven by side-chain repacking. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, W384–W388 (2013).

Bento, A. P. et al. An open source chemical structure curation pipeline using RDKit. J. Cheminform. 12, 51 (2020).

Meng, E. C. et al. UCSF chimerax: tools for structure Building and analysis. Protein Sci. 32, e4792 (2023).

Volkamer, A., Kuhn, D., Rippmann, F. & Rarey, M. DoGSiteScorer: a web server for automatic binding site prediction, analysis and druggability assessment. Bioinformatics 28, 2074–2075 (2012).

Dallakyan, S. & Olson, A. J. Small-molecule library screening by Docking with pyrx. In Chemical Biology (eds Hempel, J. E., Williams, C. H. & Hong, C. C.) 243–250 (Methods and Protocols, Springer, 2014).

DeLano, W. L. Pymol: an open-source molecular graphics tool. CCP4 Newsl. Protein Crystallogr. 40, 82–92 (2002).

Studio, D. Discovery studio. Accelrys [21]. 420, 1–9 (2008).

Lipinski, C. A. Lead-and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov Today Technol. 1, 337–341 (2004).

Chow, E. et al. Desmond performance on a cluster of multicore processors. Simulation 1, 1–14 (2008).

Shivakumar, D., Harder, E., Damm, W., Friesner, R. A. & Sherman, W. Improving the prediction of absolute solvation free energies using the next generation OPLS force field. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 8, 2553–2558 (2012).

Price, D. J. & Brooks, C. L. III A modified TIP3P water potential for simulation with Ewald summation. J. Chem. Phys. 121, 10096–10103 (2004).

Benson, D., Lipman, D. J. & Ostell, J. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 21, 2963 (1993).

Geiger, H. H. & Miedaner, T. Rye breeding. Cereals 3, 157–181 (2009).

Carlson, M. P. Ergot of Small Grain Cereals and Grasses and its Health Effects on Humans and Livestock. (2011).

Hulvová, H., Galuszka, P., Frébortová, J. & Frébort, I. Parasitic fungus claviceps as a source for biotechnological production of ergot alkaloids. Biotechnol. Adv. 31, 79–89 (2013).

Sheshegova, T. K. et al. A resistance of Rye varieties to ergot and ergot alkaloid content in claviceps purpurea sclerotia on the Kirov region environments. Mikologiya i Fitopatologiya. 53(3), 177–182 (2019).

Mirdita, V. & Miedaner, T. Resistance to ergot in self-incompatible germplasm resources of winter Rye. J. Phytopathol. 157, 350–355 (2009).

Mahmood, K. et al. De Novo transcriptome assembly, functional annotation, and expression profiling of Rye (Secale cereale L.) hybrids inoculated with ergot (Claviceps purpurea). Sci. Rep. 10, 13475 (2020).

Oeser, B. et al. Cross-talk of the biotrophic pathogen claviceps purpurea and its host secale cereale. BMC Genom. 18, 1–19 (2017).

Mirdita, V., Dhillon, B. S., Geiger, H. H. & Miedaner, T. Genetic variation for resistance to ergot (Claviceps purpurea [Fr.] Tul.) among full-sib families of five populations of winter Rye (Secale cereale L). Theor. Appl. Genet. 118, 85–90 (2008).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their appreciation to the Ongoing Research Funding program (ORF-Ctr-2025-8), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A. – Conceptualization; M.A – Data curation; J.A. - Methodology; A.A & M.A. – Supervision; A.A. & J.A. - Writing – Original Draft. All authors have reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alanzi, A.R., Alqahtani, M.J. & Alqahtani, J.H. Computational identification of potential antifungal targets against Claviceps purpurea via MD simulation and MM/GBSA. Sci Rep 15, 43848 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30566-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30566-5