Abstract

The interplay between the non-Newtonian rheology of cement grout and fracture geometry exerts a critical influence on grout penetration efficiency and reinforcement performance in fractured rock masses. This study conducts a systematic investigation of the nonlinear flow behavior of cement grout in both tensile and shear fractures, utilizing theoretical analysis and numerical simulations across a range of fracture structures, apertures, and roughness levels. To capture the complex flow characteristics accurately, the Bingham–Papanastasiou model is employed as the rheological framework. Results reveal that fracture roughness intensifies flow field heterogeneity, particularly within shear fractures. Due to the influence of yield stress, grout exhibits more pronounced channelization compared to water. At high flow rates, the interaction between yield behavior and inertial forces induces notable nonlinear flow phenomena. In this regime, a modified Forchheimer equation offers superior predictive capability across fracture types. The evolution of grout flow is characterized by a three-stage process sequentially dominated by yield stress, viscous forces, and inertial forces. The critical Reynolds number (Rec) for both fracture types are identified, and the effects of fracture geometry on nonlinear flow are quantitatively evaluated via the non-Darcy coefficient. These findings contribute valuable theoretical insights into the mechanisms governing grout flow and inform the optimization of grouting design parameters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

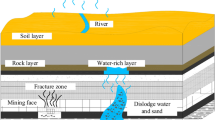

Driven by geological tectonics and engineering disturbances, rock masses commonly develop highly complex fracture networks1. Grouting with cementitious materials to fill these fractures has become one of the most widely applied and essential techniques for rock mass reinforcement and seepage control2,3. The penetration of cement grout within these fractures directly impacts the overall effectiveness of the grouting process4. Consequently, investigating the flow characteristics of the grout is crucial for achieving precise grouting, improving rock mass reinforcement, and optimizing grouting designs.

The flow characteristics of Newtonian fluids, such as groundwater, in fractured media have been extensively studied5. Pioneering experimental work by Lomiz6 and Snow7, based on the idealization of smooth parallel plates, led to the formulation of the well-established cubic law. Subsequent investigations by Louis8 confirmed the law’s validity under laminar conditions in single-fracture settings, and further research by Witherspoon et al.9 demonstrated its applicability across varying fracture apertures, both open and closed. However, at higher flow velocities, the linear relationship between flow rate and pressure gradient, as predicted by the cubic law, breaks down. Consequently, the nonlinear flow behavior of Newtonian fluids has emerged as a prominent area of research.10,11 The inherent roughness of fracture surfaces12 and asperity contact13 lead to nonlinear fluid flow. This complexity is amplified by the injection process, which initiates hydro-mechanical coupling and subsequently modifies the rock mass permeability14, thereby posing a significant challenge to the prediction of nonlinear flow dynamics. To characterize these nonlinear effects, the semi-empirical Forchheimer equation and the empirical Izbash equation are commonly employed, both of which have seen significant theoretical advancements in recent years15,16. Conversely, the study of non-Newtonian fluids flow within fractures has received comparatively less attention. Cement grout, a quintessential non-Newtonian fluid, exhibits complex rheological characteristics, including yield stress and shear-thinning phenomena17. These characteristics challenge conventional flow models, limiting their applicability and predictive accuracy in fractured media.

Cement grout exhibits a range of rheological behaviors—as power-law, Bingham, or Herschel–Bulkley fluid characteristics—depending on its water-to-cement ratio18,19. In practical engineering applications, stable cement grout is commonly idealized as a Bingham fluid, which initiates flow only when the applied shear stress exceeds its yield stress20. Early investigations into grout flow frequently employed simplified geometries, such as parallel circular disks or plates. Dai and Bird21 derived an analytical solution for the velocity profile of Bingham fluids undergoing radial flow between parallel circular disks, establishing a relationship between the height of the plug flow region and the radial penetration distance. Liu22 developed a grout penetration model for smooth, horizontal fracture surfaces based on experiments conducted in parallel-plate fracture systems. A major advancement was achieved by Gustafson and Stille23, who formulated the steady-state solution for Bingham fluid flow in one-dimensional parallel fractures, thereby defining the theoretical maximum penetration length—a milestone in the study of grout infiltration. Their later refined theory24 laid the theoretical groundwork for the real-time grouting control (RTGC) methodology25. However, these studies predominantly assume idealized smooth fracture surfaces26,27. In contrast, natural rock fractures are inherently rough and exhibit heterogeneous aperture distributions due to varying in situ stress conditions, which significantly influence grout flow behavior and diffusion patterns.

With continued progress in rock mechanics, techniques for quantifying fracture roughness have become increasingly refined28, facilitating their integration into grouting research. Early investigations employed simplified representations, such as random curves29 or predefined geometric forms30, to model rough fractures, offering initial insights into the influence of surface roughness on grout flow. To better replicate realistic fracture geometries, subsequent studies adopted Barton’s standard joint profiles to characterize rough surfaces and systematically explored grout propagation under such conditions31. The effects of both tensile and shear fractures on the resulting grout pressure field, velocity distribution, and grouting intake were later investigated32,33. Although these approaches utilized the joint roughness coefficient (JRC) to quantify surface irregularities, their two-dimensional scope limits the ability to fully capture three-dimensional morphological variations. To address this limitation, Li et al.34 applied 3D scanning toobtain detailed topographies of natural fractures, analyzing the impacts of roughness on grout flow rate and pressure loss, and proposed adjustments to the governing flow equations. However, these studies generally assumed laminar flow conditions, overlooking nonlinearities induced by inertial effects. In practical applications, such inertial effects are not always negligible. This is particularly relevant in grouting for high-level radioactive waste (HLW) repositories, where precise control over grout volume is vital to ensure long-term safety and sealing performance35,36,37. These demands underscore the importance of accurately elucidating the nonlinear flow mechanisms of grout in fracture media. Rodríguez de Castro and Radilla38 extended Darcy’s law, the weak inertia cubic law, and the full cubic law to natural rough fractures, proposing a simplified framework to predict the nonlinear relationship between pressure gradient and flow velocity in yield stress fluids. However, the applicability of this approach across diverse fracture geometries remains to be fully validated. Zou et al.39 investigated the nonlinear pressure-flow behavior of Bingham and Herschel–Bulkley fluids using 3D-scanned rough fractures and proposed an optimal grout permeability. Yet, their study lacked a comprehensive quantitative assessment of how fracture aperture and roughness affect nonlinear flow. Gao et al.40 and Li et al.41 explored shear-thinning behavior and nonlinear flow characteristics under specific regimes, though the latter focused solely on fractures with uniform apertures. The complex coupling between the non-Newtonian properties of grout and the geometric irregularities of rough fractures presents significant challenges for accurately characterizing flow behavior42. Research on nonlinear grout flow remains in its nascent stages, particularly with respect to understanding how different fracture structures influence the nonlinear dynamics of Bingham fluids.

In this study, rock fractures were categorized into tensile and shear types43 based on the matching conditions of their opposing surfaces, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Fracture geometries were generated using a modified successive random addition (SRA) algorithm, while fracture roughness was quantified through the fractal dimension. The Bingham–Papanastasiou rheological model was adopted to describe the rheological behavior of cement grout. The transition of grout flow from linear to nonlinear regimes was investigated under varying fracture morphologies, apertures, and roughness levels, and the influence of these parameters on flow nonlinearity was quantitatively assessed. A modified Forchheimer equation was developed to capture the nonlinear flow characteristics. Furthermore, for both fracture types, empirical correlations were established linking the non-Darcy coefficient to fracture aperture and roughness. Finally, based on the identified nonlinear flow behavior, grouting optimization strategies were proposed to enhance overall grouting efficiency.

Construction of grouting model for rough fractures

Generation of rough fracture surfaces

The Beishan Underground Research Laboratory (URL), China’s first underground facility dedicated to HLW repository research (Fig. 2a), imposes exceptionally stringent requirements for grouting and sealing in ramp fractures44. Conventional experimental approaches for obtaining realistic rough fracture geometries and conducting grout flow studies are often limited by high equipment costs and the difficulty of accurately capturing detailed fluid flow behavior. To overcome these challenges, this study develops numerical models based on fractal dimension to investigate grout flow mechanisms. Previous studies indicate28,45 that while natural rock fracture surfaces exhibit fractal characteristics, their geometry is not strictly self-similar but instead displays self-affine properties. As a result, fractional Brownian motion (fBm) can be effectively employed to model such rough surfaces. Common techniques for generating fBm include the Weierstrass–Mandelbrot function, the SRA method, and Fourier approaches46. Due to its superior computational efficiency, the SRA method is widely used to represent natural fracture geometries and is therefore adopted in the present study to generate rough surfaces with fractal properties.

In the context of fBm, the surface height fluctuations of a rough fracture are represented by a continuous, single-valued function Z(x,y) defined over two spatial variables. The increment of this function, Z(x + hx,y + hy) − Z(x,y), follows a zero-mean Gaussian distribution47. This statistical property, indicative of the self-affine nature of the surface, satisfies the following relationship:

Here, \(\left\langle \cdot \right\rangle\) denotes the mathematical expectation; H represents the Hurst exponent (ranging from 0 to 1), with higher values corresponding to smoother fracture surfaces; r is a constant; and \(\sigma^{2}\) denotes the variance.

The conventional SRA algorithm often produces Gaussian fractal surfaces with inadequate scaling and correlation characteristics. To address this limitation, Liu et al.48 proposed a modified SRA algorithm better suited for simulating rough fracture morphologies. The fundamental steps are as follows:

-

1.

A square domain is defined, and initial coordinates are assigned to its four corners, where the elevation values follow a zero-mean Gaussian distribution with a variance of \(\sigma_{0}^{2}\). In this study, the initial variance is set to 1.

-

2.

Using linear interpolation, the coordinates and elevation of the square’s center point and the midpoints of its four edges are determined. Subsequently, a random perturbation drawn from a Gaussian distribution \(N(0,\sigma_{1}^{2} )\) is added to the elevation of each newly generated point.

$$\sigma_{1}^{2} = \frac{{\sigma_{0}^{2} }}{{2^{2H} }}\left(1 - \frac{{2^{2H} }}{4}\right)$$(3) -

3.

Following step (2), four new squares are formed. For each square, the coordinates and elevation of the center point and the midpoints of the four edges are obtained through linear interpolation of the corresponding corner points. A random value sampled from a Gaussian distribution \(N(0,\sigma_{2}^{2} )\) is then added to the elevation of each interpolated point.

$$\sigma_{2}^{2} = \frac{{\sigma_{1}^{2} }}{{\left(2^{2H}\right)^{2} }}\left(1 - \frac{{2^{2H} }}{4} \right)$$(4) -

4.

Repeat step (3). After n iterations, this process yields a rough surface with dimensions 2n × 2n and (2n+1)2 nodes.

$$\sigma_{n}^{2} = \frac{{\sigma_{n - 1}^{2} }}{{2^{2H} }} = \frac{{\sigma_{0}^{2} }}{{\left(2^{2H}\right)^{2n} }}\left(1 - \frac{{2^{2H} }}{4}\right)$$(5) -

5.

A random perturbation drawn from a specified distribution \(N(0,\sigma_{j}^{2} )\) is added to the elevation of all generated points.

$$\sigma_{j}^{2} = \frac{{\sigma_{j - 1}^{2} }}{{2^{2H} }} = \frac{{\sigma_{0}^{2} }}{{\left(2^{2H}\right)^{j} }}\left(1 - \frac{{2^{2H} }}{4}\right)$$(6)where \(j = n + 1,n + 2, \cdots NM\), until \(\frac{{\sigma_{NM} }}{{\sigma_{0} }}\) is small enough to be neglected.

The relationship between the Hurst exponent H and the fractal dimension D is expressed as49:

The fractal dimension D serves as a quantitative parameter for characterizing the roughness of fracture surfaces, reflecting their geometric complexity and irregularity. A higher value of D corresponds to a rougher surface morphology. For natural fractures, the fractal dimension typically falls within the range of 2–2.550.

Construction of different types of fractures

Based on mechanical origin, rock fractures are categorized as either tensile or shear types. Tensile fractures are characterized by a high degree of surface matching between the opposing fracture faces and relatively uniform apertures along the direction of propagation. In contrast, shear fractures exhibit low surface congruence due to displacement induced by shearing, leading to significant heterogeneity in aperture distribution. To model fracture roughness, a modified SRA algorithm was implemented in MATLAB with a generation order of n = 7, producing rough surfaces with varying fractal dimensions. The resulting point cloud datasets were subsequently imported into COMSOL Multiphysics for numerical simulations. For tensile fracture models, two identically rough surfaces were generated using a mirror-image approach, and the target aperture was controlled by vertically displacing one surface relative to the other. In shear fracture models, initial mean apertures were first defined, followed by the application of shear displacement to one surface along a specified direction to replicate realistic shear-induced geometries. To isolate the effects of roughness and aperture on fluid flow, surface contact was not considered; that is, no physical contact zones were assumed between fracture surfaces. After shear displacement, fine adjustments of the relative vertical positions were conducted to ensure that the average aperture of the fracture model aligned with the target value. This methodology enables precise construction and parametric control of diverse fracture geometries. The generated fracture models are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Numerical simulation and nonlinear analysis methods

Governing equations

Fluid flow within complex fractures is generally considered to be steady, incompressible, isothermal, and laminar39,51. The flow behavior adheres to the principles of mass and momentum conservation and is governed by the Navier–Stokes equations, which consist of the continuity equation and the momentum equation. These equations are expressed as follows:

where ρ denotes the fluid density, t represents time, P is the pressure, u is the velocity vector, g denotes gravitational acceleration, τ is the shear stress tensor, and F corresponds to the body force per unit volume.

Cement grout used in rock mass grouting behaves as a non-Newtonian fluid. Over the past decades, the Bingham rheological model has been extensively adopted for the theoretical characterization of grout flow behavior. Its tensorial formulation is given as follows:

where μg denotes the plastic viscosity, τ0 represents the yield stress, τij is the shear stress tensor, and \({\mathop {\gamma_{ij} }\limits^{.} }\) is the shear rate tensor, defined as follows:

As shown in Eq. (12), the ideal Bingham model is discontinuous at a shear rate of zero, resulting in numerical instability. To address this, Papanastasiou and Boudouvis52 proposed a modified Bingham model. By introducing an exponential term, this model ensures a continuous variation of shear stress between the yield and non-yield regions.

This equation represents the Bingham–Papanastasiou model, where m is the regularization parameter. A larger value of m results in the Bingham–Papanastasiou model more closely approximating the ideal Bingham model.

Deng et al.53 demonstrated through combined laboratory experiments and numerical validation that a value of m = 100 provides satisfactory accuracy in grouting calculations. Similarly, in studies investigating slurry flow through rough fractures, m = 100 has been shown to ensure reliable computational performance34,39. The Bingham–Papanastasiou model eliminates the need to explicitly define a yield surface, thus enabling more efficient numerical computations. As a result, this approximation (with m = 100) has been widely adopted in the numerical simulation of yield stress fluids in engineering applications. In this study, the Bingham–Papanastasiou model (with m = 100) was employed to characterize the Bingham fluid, and the governing equations (Eqs. 8–13) were solved using the finite element software COMSOL multiphysics.

Simulation parameters

Regarding the grout performance for HLW repositories, Kronlöf54 proposed target indicators: a plastic viscosity not exceeding 50 mPa s and a yield stress below 5 Pa. In the present study, the upper limits of these material properties were adopted for the simulations. Establishing appropriate boundary conditions is crucial for efficiently solving the Navier–Stokes equations. For grout flow within the fracture, the inlet boundary was set to a constant velocity, ranging from 0.01 to 10 m/s. This range is intended to cover various flow conditions encountered in engineering applications. The outlet boundary of the model was defined as an atmospheric pressure condition. The effect of flow inertia was investigated by varying the inlet velocity. The remaining fracture surfaces were treated as impermeable and no-slip boundaries (i.e., n·u = 0 m/s). The fracture aperture was characterized by the geometric mean aperture, e, which ranged from 0.5 to 2.0 mm. The fracture had a width of 50 mm and a length of 100 mm. The key parameters involved in the simulations are listed in Table 1. A schematic diagram of the numerical simulation model is presented in Fig. 3.

Verification of rheological model and mesh independence

For a given pressure gradient and no-slip boundary conditions, a steady analytical solution exists for the flow of Bingham fluid between smooth parallel plates. Integrating Eq. (10) yields the cross-sectional velocity distribution:

where b is the half-aperture; and h0 is half the plug flow height, resulting from the yield stress. Integrating this velocity profile across the aperture yields the exact solution for the flow rate, known as the Buckingham equation55:

To assess the accuracy of the numerical computations based on the Bingham–Papanastasiou rheological model, the simulated results were compared with corresponding analytical solutions. The computed velocity profiles and flow rates are presented in Fig. 4. The numerical model effectively captured the dynamic evolution of the plug region in the yield stress fluid, with the plug height exhibiting a decreasing trend as the flow velocity increased. Moreover, the relative error between the numerically predicted flow rates and the analytical solutions remained consistently within 5%. This level of agreement satisfies the accuracy requirements for engineering applications, thereby confirming the reliability of the model in simulating the flow behavior of complex yield stress fluids.

When modeling the flow of non-Newtonian fluids within rough fractures, the mesh size of the computational domain plays a pivotal role in determining both solution stability and computational efficiency. Given that tensile and shear fractures exhibit distinct geometric features leading to different flow behaviors, a mesh independence study was conducted separately for each fracture type. The test utilized a fracture aperture of 1 mm and a fractal dimension of 2.5. Simulations were performed at inlet velocities of 0.01, 0.1, 1, 5, and 10 m/s. The GMRES solver was applied with a residual tolerance of 0.01 and a maximum iteration limit of 1000.

The mesh consisted of fluid dynamics-adapted unstructured tetrahedral elements, incorporating 5 boundary layers. Five mesh resolutions were evaluated: Coarser (Mesh 1), Coarse (Mesh 2), Normal (Mesh 3), Fine (Mesh 4), and Finer (Mesh 5). Using Mesh 5 as the reference, the relative deviation of computational results for each mesh resolution was calculated, as illustrated in Figs. 5 and 6. It was observed that finer mesh resolutions significantly reduced the overall discrepancy in simulation outcomes for both fracture types. Specifically, Mesh 4 yielded a relative deviation of less than 2% compared to the reference mesh, while requiring only one-quarter of the computation time. Notably, further refinement would increase the total element count to over 10 million, exceeding the available memory capacity. Considering the balance between computational accuracy and cost, Mesh 4 was selected as the optimal meshing strategy for the rough fracture models employed in this study. For the model with a 0.5 mm aperture, the minimum element size was 0.17 mm, yielding approximately 1.54 million elements. For the 2 mm aperture model, the minimum element size was 0.19 mm, with a total of approximately 2.22 million elements.

Nonlinear flow analysis

At high flow rates, the Forchheimer equation is commonly applied to characterize the nonlinear flow behavior of Newtonian fluids15:

where eh denotes the hydraulic aperture, w is the fracture width, ρ represents the fluid density, β is the non-Darcy inertia coefficient, A is the linear coefficient, and B is the nonlinear coefficient accounting for inertial effects.

Given that grout behaves as a yield stress fluid, a yield stress term must be incorporated to modify the Forchheimer equation. The second term in Eq. (17) is jointly influenced by yield stress and pressure gradient. Considering that the yield stress of grout typically remains below 100 Pa, while practical injection pressures often exceed 1 MPa, the contribution of this term is negligible. Therefore, it can be treated as a higher-order infinitesimal and omitted without compromising accuracy56. To delineate the applicability limits of this simplification, the conditions under which the term can be neglected were evaluated by comparing the relative error in flow rate Q between the full and reduced models. The yield stress range used in the analysis was 0.5–100 Pa, encompassing typical water-cement ratios from 0.4:1 to 10:1 commonly encountered in engineering applications57.

As illustrated in Fig. 7, when the pressure gradient approaches the critical threshold of a Bingham fluid—beyond which flow initiates—the relative error in flow rate Q increases markedly, indicating that this term cannot be neglected under such conditions. However, with increasing pressure gradient, the error associated with this term rapidly diminishes. Once the pressure gradient exceeds 2.76 times the critical value, the error reduces to below 5%. Given that pressure gradients in grouting applications are generally much higher than the critical threshold, this higher-order terms has typically been omitted in previous studies58,59. Accordingly, by neglecting this term and combining with Eq. (18), a modified Fochheimer equation that incorporates the effect of yield stress can be derived:

The Reynolds number (Re) is a dimensionless quantity defined as the ratio of fluid inertial forces to viscous forces. It is an important indicator for determining the flow regime. Its expression is as follows5,15:

The Bingham number (Bn), a dimensionless parameter defined as the ratio of yield stress to viscous forces, serves as a key indicator for characterizing the flow regime of yield stress fluids. It is expressed as follows60:

For yield stress fluids, the nonlinear influence factor is defined as E41. When E exceeds 10%, the flow is considered to exhibit nonlinear behavior:

Normalized transmissivity (Ta/T0) serves as another indicator for quantifying flow characteristics. For Newtonian fluids (C = 0), the ratio of apparent transmissivity to intrinsic transmissivity is expressed as10:

where Ta denotes the apparent transmissivity, T0 is the intrinsic transmissivity, and A is the coefficient in the Forchheimer equation. For yield stress fluids, to better characterize flow behavior, the following normalized transmissivity is proposed based on Eqs. (22) and (23a):

In this study, all calculations involving normalized transmissivity were performed using Eq. (24).

Results

Tensile fracture

Fluid flow analysis

Figure 8 illustrates the computed distributions of pressure, velocity, and streamlines within the tensile fracture. To enhance the visualization of local three-dimensional velocity characteristics, the velocity field is represented using 15 × 15 cross-sectional planes. Under conditions of a 0.5 mm fracture aperture and an inlet velocity of 0.01 m/s, the flow regime approximates laminar behavior, with streamlines appearing predominantly parallel and linear. As the fractal dimension of fracture roughness increases from 2.1 to 2.5, spatial heterogeneity in the velocity field becomes more pronounced, although the overall flow pattern remains largely stable. Simultaneously, while the macroscopic pressure exhibits a consistent decline from the inlet to outlet, localized pressure fluctuations are intensified by the increased roughness. With larger fracture apertures, both the complexity and heterogeneity of the flow field are further amplified. Notably, under high roughness conditions (D = 2.5), significant non-uniformities in pressure and velocity emerge, and streamlines transition to a more chaotic and tortuous configuration.

To quantitatively characterize the microscopic flow field and the distribution of grout velocity within fractures, as well as to detail velocity variations along the fracture path, flow tortuosity is employed as an analytical metric. Among the various existing definitions of tortuosity, the formulation proposed by Zhang et al. is adopted in this study61:

where \(\overline{{\left| {\varvec{U}} \right|}}\) and \(\overline{{U_{x} }}\) represent the average values of velocity magnitude and x-component velocity, respectively.

Figure 9 illustrates the flow tortuosity within tensile fractures under varying roughness and aperture conditions. The results demonstrate that fracture aperture plays a dominant role in influencing flow tortuosity, which increases with decreasing aperture and increasing roughness. For apertures ranging from 0.5 to 1 mm, tortuosity initially decreases and then increases markedly, a trend consistent with previous observations for Newtonian fluids61. At lower velocities, where viscous forces prevail, increasing velocity diminishes viscous effects and promotes the formation of preferential flow channels, thereby reducing tortuosity. However, as velocity continues to rise, inertial forces become predominant, leading to an increase in tortuosity. Similar behavior was reported by Zou et al.39 in studies involving yield stress fluids, and this study confirms the same trend for fractures with apertures between 0.5 and 1 mm. For apertures exceeding 1 mm, tortuosity exhibits a prolonged plateau following an initial decline, with only a gradual increase observed at significantly higher velocities. This behavior is attributed to the higher viscosity and yield stress of grout compared to water, which enhances its resistance to inertial stress and results in a more pronounced channelization effect in larger fractures.

Pressure gradient and flow rate

Figure 10 presents the relationship between the slurry pressure gradient and flow rate in tensile fractures, considering variations in fracture aperture and fractal dimension. The pressure gradient increases with both fracture roughness and flow rate. For small-aperture fractures (e ≤ 1 mm) under low flow rates, numerical results closely match the analytical predictions of Eq. (17), where the pressure gradient exhibits an approximately linear dependence on flow rate. At this stage, the influence of fracture roughness on the pressure gradient is negligible. However, as the flow rate increases, the pressure gradient curve gradually develops an upward curvature, indicating the onset of nonlinear flow behavior. In contrast, wider fracture apertures enhance the flow capacity and reduce the overall magnitude of the pressure gradient, while inertial effects become increasingly significant. Consequently, the pressure gradient exhibits a distinct nonlinear, quadratic trend, with fracture roughness exerting a more pronounced effect. Under these conditions, numerical results deviate considerably from the analytical predictions of Eq. (17), primarily because that equation neglects inertial contributions arising from fracture geometry and flow boundary conditions. Calculations based on Eq. (19), shown as dash-dotted lines in Fig. 8, account for the combined effects of fluid yield stress, fracture geometry, and flow characteristics, producing results that agree well with the observed pressure gradient trends. This consistency confirms that the modified Forchheimer equation effectively captures the nonlinear flow behavior of Bingham fluids. Therefore, neglecting nonlinear fluid dynamics under conditions of large apertures and high flow rates would lead to a substantial underestimation of the pressure gradient.

Figure 11 compares pressure gradient versus flow rate for water in fractures with 0.5 mm and 1 mm apertures. Under identical boundary conditions, water exhibits stronger nonlinear flow effects than slurry, with its pressure gradient deviating markedly from the cubic law as flow rate increases. Fracture roughness significantly impacts water flow, with pressure gradients rising sharply as fractal dimension increases. At low flow rates, slurry in small aperture fractures displays solid-like behavior due to its yield stress, resisting inertial effects from fracture geometry. Consequently, slurry pressure gradients exceed those of water by one to two orders of magnitude under comparable conditions. However, slurry’s higher viscosity and yield strength result in less pronounced nonlinear flow characteristics compared to water.

Normalized transmissivity

The nonlinearity in fluid flow is primarily attributed to inertial losses. To quantitatively characterize the transition from linear to nonlinear flow regimes, this study introduces normalized transmissivity (Ta/T0) for analysis. The Re at which Ta/T0 drops below 0.9 is defined as the critical Reynolds number (Rec), following the criterion proposed by Zimmerman et al.10. The relationship between Ta/T0, Re, and Bn is illustrated in Fig. 12, which reveals distinct flow regime transitions. At low Re < 1, where viscous and inertial forces have minimal influence, yield stress dominates, and the fluid behaves as a solid, with normalized transmissivity approximately constant. When Bn falls below 1, viscous forces begin to dominate, and the Ta/T0 curve starts to decline. Once Ta/T0 drops below 0.9, the curve decreases rapidly, as inertial forces govern flow, and nonlinear flow characteristics dominate. Rec is closely correlated with fracture roughness, generally decreasing as roughness increases, consistent with the findings of Li et al.41 However, this effect varies significantly between low roughness (fractal dimension D < 2.3), and high roughness regimes. For instance, in a fracture with an average aperture of 0.5 mm, an increase in the fractal dimension D from 2.2 to 2.3 results in an 81.7 decrease in Rec. In contrast, when D increases from 2.4 to 2.5, Rec decreases by only 16, indicating a stronger influence of roughness in low roughness regimes.

Analysis of flow characteristics based on the Forchheimer model

The non-Darcy coefficient β is introduced to modify the conventional linear flow model. Its magnitude quantifies the extent of Forchheimer flow development and characterizes the nonlinear effects induced by fracture geometry and fluid properties. Based on the simulation results, Fig. 13 illustrates the influence of fracture aperture and roughness on β. According to the observed data trends, D and e were selected as independent variables, while m1 to m5 were employed as fitting parameters, resulting in Eq. (26). The obtained coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.9617) indicates an excellent level of agreement between the fitted and simulated results.

As illustrated in Fig. 12, β exhibits a distinct correlation with the geometric characteristics of the fracture, particularly aperture and surface roughness. With increasing surface roughness, the tortuosity of internal flow pathways becomes more pronounced, leading to greater inertial energy losses during fluid transport. This enhances the nonlinear flow behavior, reflected by an increase in the β value. In contrast, as the fracture aperture widens, the flow channel becomes more open, and the relative influence of wall roughness on the main flow region diminishes, resulting in a decreasing trend in β.

Shear fracture

Fluid flow analysis

Figure 14 illustrates the distributions of velocity, pressure, and streamlines within shear fractures. Due to variations in aperture, the flow fields within shear fractures exhibit greater heterogeneity and complexity compared to tensile fractures. In small-aperture shear fractures, pronounced non-uniformity in velocity distribution is observed even under minimal roughness conditions. By contrast, tensile fractures display noticeable velocity heterogeneity only at high roughness levels (e.g., D = 2.5). At low roughness, the fluid preferentially flows along dominant pathways, and streamlines exhibit distinct bypassing behavior. As roughness increases, this bypassing phenomenon gradually diminishes, likely because enhanced geometric complexity disrupts the formation of macroscopic preferential channels. Under low roughness, the fluid can form large-scale, concentrated bypassing paths through dominant flow zones; however, as the internal fracture structure becomes more intricate, these preferential channels are suppressed, and the fluid is forced to traverse the entire fracture in a more uniformly tortuous manner. With increasing fracture aperture, the flow channels expand substantially, and the disturbance induced by surface roughness shows a clear attenuation trend. Under large-aperture conditions, fluid motion is no longer confined to localized preferential pathways but transitions into a more uniform and diffuse flow throughout the fracture space.

Figure 15 presents the flow tortuosity results for shear fractures. Similar to tensile fractures, flow tortuosity gradually decreases with increasing fracture aperture. Under larger aperture conditions, the channelization of fluid flow becomes particularly evident, indicating that a wider aperture promotes the development of more unobstructed flow pathways. Due to the non-uniformity distribution of fracture apertures, small-aperture fractures (e = 0.5 mm) exhibit a distinct trend characterized by an initial decrease in tortuosity, followed by a sharp rise and subsequent stabilization. This behavior suggests that even minor variations in aperture can substantially influence the flow characteristics within narrow fractures. Zou et al.39 reported that in shear fractures containing contact zones, the presence of these zones induces pronounced preferential and bypass flow pathways. Such complex flow patterns lead to stronger fluctuations in tortuosity, with the increasing trend persisting over a wider range of flow conditions.

Pressure gradient and flow rate

Figure 16 illustrates the relationship between grout pressure gradient and flow rate in shear fractures under different fracture apertures and fractal dimensions. As the fractal dimension increases, indicating greater surface roughness, and the fracture aperture enlarges, the nonlinear characteristics of the pressure gradient-flow rate curves become increasingly evident. This behavior implies that at higher roughness and larger apertures, flow within shear fractures deviates more substantially from linear behavior, resulting in a greater discrepancy between the pressure gradient curves and the analytical solution. The dotted lines in Fig. 16 represent the data fittings obtained using the modified Forchheimer equation. The strong agreement between the fitted and simulated results confirms that the equation effectively captures the nonlinear relationship between pressure gradient and flow rate. Notably, when the fracture aperture reaches e = 2.0 mm, the influence of surface roughness exhibits a clear grouping behavior: curves corresponding to fractal dimensions of 2.1–2.2 are distinctly separated from those of 2.3–2.5. This separation may be attributed to the increased heterogeneity of the internal fracture geometry induced by higher roughness, which intensifies flow field complexity and enhances energy dissipation mechanisms.

Normalized transmissivity

Figure 17 illustrates the relationship between the normalized transmissivity (Ta/T0), Re, and Bn for shear fractures. Similar to tensile fractures, the variation trend can be divided into three distinct regimes. In the plateau regime (Bn > 1), flow behavior is predominantly governed by the fluid yield stress, while inertial and viscous effects remain minimal; consequently, Ta/T0 stays approximately constant at around 1.0, forming a stable plateau. In the transition regime (0.1 < Bn < 1), as Re increases and Bn decreases, the influence of yield stress gradually weakens, viscous effects become dominant, and Ta/T0 exhibits a progressive decline. In the nonlinear regime (Ta/T0 < 0.9) inertial forces prevail, the flow displays pronounced nonlinear characteristics, and the normalized transmissivity drops sharply. Compared with tensile fractures, the Rec for shear fractures is consistently lower, not exceeding 150 in any examined case. This behavior primarily results from the greater spatial heterogeneity and higher flow path tortuosity inherent to shear-induced fractures, which enhance inertial losses and trigger earlier transitions to nonlinear flow. No clear correlation is observed between fracture aperture and Rec, likely due to the combined effects of multiple interrelated factors—including fracture geometry, spatial heterogeneity, fluid yield stress, and viscosity—which collectively induce fluctuations in Rec, consistent with the findings of Li et al.41.

Analysis of flow characteristics based on the Forchheimer model

Equation (26) was employed to fit the data in order to evaluate the influence of fracture geometric characteristics on the non-Darcy coefficient β. The fitting results are presented in Fig. 18, yielding a high coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.9650), which demonstrates the excellent performance of the proposed correlation. This equation is applicable to both tensile and shear fractures. The variation trend of β in shear fractures is consistent with that observed in tensile fractures, showing an increase with decreasing fracture aperture and increasing surface roughness. However, the overall magnitude of β in shear fractures is notably higher, indicating stronger nonlinear flow effects. This distinction primarily arises from the greater heterogeneity of the flow pathways in shear fractures, which intensifies energy dissipation during fluid movement. The enhanced spatial irregularity amplifies inertial contributions and leads to larger β value. Consequently, the elevated heterogeneity inherent to shear fractures reinforces the influence of geometric complexity on nonlinear flow behavior.

Discussion

A comparative study of two fractures

Regarding on grout flow in rock fractures has historically relied on simplified representations, such as the smooth parallel-plate model27 or Darcy’s law under the assumption of a linear flow regime62. However, these approaches neglect the intrinsic roughness and irregularities of natural fractures, as well as the nonlinear effects that emerge under high-velocity flow conditions. Although later studies began to incorporate fracture roughness4,39, they were generally confined to a single structural type. Consequently, a systematic comparative investigation has been lacking regarding how fractures with distinct geological origins—and thus differing structural morphologies—affect the nonlinear flow behavior of grout. In this study, fracture geometries with varying spatial configurations were generated using a modified SRA algorithm, while the cement grout was modeled based on the Bingham–Papanastasiou rheological framework. Building upon these foundations, the nonlinear flow characteristics were quantified through a modified Forchheimer equation, enabling a comprehensive and comparative analysis of grout flow behavior within two representative types of fracture structures.

The distributions of pressure, velocity, and streamlines in both types of rough fractures exhibit pronounced complexity and heterogeneity. With increasing surface roughness, the internal flow field becomes increasingly intricate. In shear fractures, streamlines reveal distinct bypass flows and fluid diversion along preferential pathways, primarily driven by spatial heterogeneity, which channels the grout through more connected regions. In contrast, tensile fractures maintain a relatively uniform aperture, offering a more homogeneous flow environment. Although increasing flow rate and roughness introduce moderate curvature to the streamlines, no significant bypass flow or diversion is observed. Consistent with the findings of Li et al.41, grout streamlines under high flow conditions do not show evident flow diversion. However, Gao et al.40 reported streamline bypass near fracture contact points, accompanied by vortex formation at elevated flow rates.

Due to aperture non-uniformity, shear fractures exhibit greater flow path tortuosity, particularly prominent at a 0.5 mm aperture. When the aperture exceeds 1 mm, the tortuosity of the velocity field in both fracture types initially decreases with increasing flow rate, then stabilizes, and subsequently increases gradually. This behavior is attributed to the yield stress of the grout, which enhances resistance to inertial effects. As a result, grout displays a more pronounced channeling behavior than Newtonian fluids61.

For the macroscopic flow field, at higher flow rates, both types of rough fractures deviate significantly from the analytical solution based on the smooth parallel plate assumption, primarily because the analytical solution neglects fracture surface roughness and nonlinear fluid effects at high flow rates. To better describe the nonlinear relationship, this study employed the modified Forchheimer equation to fit the relationship between pressure gradient and flow rate, demonstrating strong agreement. Under conditions of smaller aperture and lower flow rates, the numerical results for both fracture types are closer to the analytical solution, and the influence of roughness is less pronounced. Notably, at a 0.5 mm aperture, the numerical results for tensile fractures show high consistency with the analytical solution. In contrast, the nonlinear flow behavior of water is more significant, and the influence of roughness is more evident, consistent with the findings of Zou et al.39. Due to their greater geometric complexity and pore structure non-uniformity, shear fractures exhibit higher flow resistance, manifested as a higher pressure gradient. For example, at a 0.5 mm aperture, roughness of 2.5, and inlet velocity of 10 m/s, the pressure gradient in shear fractures is approximately 12% higher than in tensile fractures.

A comprehensive assessment of the grout’s nonlinear behavior was performed using normalized transmissivity, Re, and Bn. Results indicate that grout flow in both fracture types progresses through three distinct regimes. When Bn > 1, the system is in the plateau regime (Ta/T0 ≈ 1), characterized by low Re, where yield stress governs the flow, and the grout exhibits solid-like behavior. When 0.1 < Bn < 1, the system transitions to a regime dominated by viscous forces, and the flow begins to exhibit nonlinear characteristics. Under conditions of greater roughness and aperture, increasing Re narrowers the transitional range and accelerates the onset of nonlinear flow in shear fractures. When Bn is much less than 0.1 (in the high Re stage), inertial forces dominate the motion, and the flow is in the nonlinear regime. The critical Re ranges from 39.1 to 272.7 for tensile fractures, and from 30.2 to 148.1 for shear fractures.

The results reveal that slurry flow in both types of fractures exhibits three distinct regimes. When Bn > 1, the flow remains in a plateau regime, characterized by low Re, where yield stress governs the fluid motion. The applied shear stress is insufficient to overcome the internal yield stress, causing the slurry to behave in a solid-like manner with extremely low mobility. Macroscopically, this is reflected by the normalized permeability remaining at a very low plateau value. When 0.1 < Bn < 1, the flow transitions into a regime dominated by viscous forces, where fluidity improves significantly. In this stage, fracture geometry plays a critical role: increasing roughness and aperture reduce the suppressing effect of yield stress on the flow. Notably, shear fractures exhibit a shorter transitional period and evolve more rapidly toward nonlinear flow. When Bn ≪ 0.1, the flow enters a high-Re regime dominated by inertial forces, and the behavior becomes nonlinear. The influence of yield stress becomes negligible, and the energy dissipation mechanism shifts from viscous dissipation to inertia-dominated losses. The Rec for tensile fractures ranges from 39.1 to 272.7, while that for shear fractures ranges from 30.2 to 148.1. The lower Rec in shear fractures is attributed to the mismatched walls, which form a complex flow network consisting of local constrictions and relatively open regions. This geometry forces the slurry to undergo drastic local variations in velocity vectors, even at low flow rates. These disturbances accelerate the onset and evolution of inertial effects, leading to an earlier transition into the nonlinear regime, which is macroscopically manifested as a reduced Rec.

The relationship between critical Re and fracture aperture shows some variability. In tensile fractures, a larger aperture corresponds to a smaller critical Re, a phenomenon also observed in other studies41. This could be due to the multi-factor coupling of rheological parameters and fracture geometry. Research by Zhu63 indicates that, compared to Newtonian fluids, Bingham fluids tend to flow preferentially in fractures with larger apertures. This is because the yield stress effects can be more easily counteracted, allowing Bingham fluids to exhibit characteristics more similar to those of Newtonian fluids in larger fractures.

For the non-Darcy coefficient, the influence of fracture geometry on nonlinear flow becomes more pronounced as roughness increases and aperture decreases. The values obtained from shear fractures are slightly higher than those from tensile fractures, which is attributed to the non-uniformity of their apertures. Due to the surface mismatch between the upper and lower walls of shear fractures, the overall tortuosity of flow paths increases, and more importantly, complex local flow fields are generated. When the fluid passes through these heterogeneous spaces, composed of narrow throats and cavities, it undergoes frequent and abrupt changes in direction and velocity, resulting in stronger secondary flows and the formation of local vortex structures. These complex flow patterns significantly intensify kinetic energy dissipation, which is macroscopically manifested as greater inertial pressure loss; hence, β values are higher. Therefore, β not only reflects the roughness of the fracture but also characterizes the complex flow structures induced by spatial heterogeneity. However, due to the presence of yield stress, although β increases in fractures with smaller apertures, the flow can still remain relatively stable, as observed in both fracture types.

The engineering implication of rock grouting

In rock mass grouting, cement grout behaves as a typical Bingham fluid, and its nonlinear flow characteristics play a crucial role in guiding refined grouting applications, such as those required for HLW repositories. The dimensionless analysis framework established in this study, based on the Re and the Bn, provides semi-quantitative guidance for grouting engineering design. During the design phase, the anticipated injection rate can be used to preliminarily estimate the corresponding Re and Bn values, thus enabling a pre-assessment of the grout’s flow regime. For small-aperture fractures, particularly tensile fractures, the flow typically resides in a plateau region where Bn > 1, allowing nonlinear effects to be neglected. For fractures with apertures exceeding 1 mm, nonlinear characteristics are also insignificant under low-Re conditions. However, when the pre-calculated Re value approaches the critical range (39.1–272.7 for tensile fractures and 30.2–148.1 for shear fractures), and Bn is substantially less than 0.1, the flow is expected to enter a strongly nonlinear regime. On this basis, targeted pressure control strategies can be developed for engineering practice. In the predicted linear regime, conventional pressure design based on the cubic law is applicable. In contrast, once nonlinear flow is anticipated, the additional pressure losses induced by inertia must be fully considered, and a rational upper limit of injection pressure should be established to prevent efficiency loss due to excessive pressurization. Furthermore, maintaining flow within a high-efficiency region can be achieved by optimizing the grout mix to adjust Bn or by controlling the injection rate to regulate Re. The proposed Re–Bn dual-parameter design methodology allows precise control of injection parameters, preventing ineffective pressure increase, and ultimately enhances both grouting efficiency and reinforcement performance.

Limitations

The pronounced disparity in magnitude between fracture aperture and grout propagation length gives rise to a significant scale effect. For rough fractures with apertures below 0.2 mm, the associated computational cost becomes a critical bottleneck, limiting the feasibility of detailed investigations4. In this study, the modeled domain spans 50 mm × 100 mm, which remains considerably smaller than typical engineering scale. Although dimensionless parameters such as Re and Bn were utilized to facilitate analysis, and the scaling laws derived from the small-scale model offer partial guidance for large-scale applications, direct extrapolation of these quantitative results to meter-scale engineering systems requires considerable caution. Moreover, the present study does not incorporate fracture contact. In natural fractures, shear displacement is often accompanied by dilation and localized contact, resulting in preferential flow channels. These contact zones significantly enhance the tortuosity and heterogeneity of flow paths, forcing grout to traverse narrower and more convoluted routes. It is foreseeable that accounting for contact effects would yield a higher non-Darcy coefficient β and a lower Rec than those estimated in this study. Consequently, the extent of nonlinear effects in real shear fractures may be underestimated to some degree. Future work should focus on the role of fracture contact in grout transport to achieve more realistic assessments of its influence.

Conclusions

This study uses a modified SRA algorithm to generate tensile and shear fracture models. It employs the Bingham–Papanastasiou rheological model to simulate the viscoplastic flow of cement slurry. Steady-state flow fields were solved using COMSOL Multiphysics. The effects of fracture structure, aperture, and roughness on the slurry’s nonlinear flow characteristics were investigated. The key findings of this study are as follows:

-

1.

Rough fractures significantly enhance the spatial heterogeneity of the slurry’s pressure field, velocity field, and streamline distributions, with this effect being more pronounced in shear fractures. Due to the slurry’s yield stress, the channeling phenomenon of Bingham fluids is stronger than that of Newtonian fluids.

-

2.

At high flow rates, the coupled effects of yield stress and inertial forces result in nonlinear flow characteristics in both tensile and shear fractures. Compared to Newtonian fluids, slurry with yield stress exhibit less pronounced nonlinear behavior in small aperture fractures; as fracture aperture increases, the constraint of yield stress weakens, and nonlinear effects become more significant. The modified Forchheimer equation effectively fits the flow data for both fracture types, demonstrating strong applicability.

-

3.

A dimensionless framework using normalized transmissivity, Bn, and Re reveals three flow regimes. When Bn > 1, a plateau regime occurs. When 0.1 < Bn < 1, a transition regime follows, shorter in shear than in tensile fractures. When Bn << 0.1 at high Re, a nonlinear regime prevails. Rec values range from 39.1 to 272.7 for tensile fractures and from 30.2 to 148.1 for shear fractures.

-

4.

The non-Darcy coefficient quantitatively reflects the impact of fracture geometry on inertial effects. Smaller apertures and higher surface roughness increase the coefficient, with shear fractures exhibiting higher values than tensile fractures under identical conditions.

-

5.

The Re–Bn dual-parameter framework developed in this study offers a predictive tool for engineering design, guiding pressure control strategies by anticipating the flow regime from estimated Re and Bn values. While conventional cubic-law methods suffice for the linear regime, the nonlinear regime necessitates fully incorporating the additional pressure loss from inertial effects. This allows for precise control over injection parameters to avoid ineffective pressurization, ultimately optimizing both grouting efficiency and reinforcement performance.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Chaoshang, S. et al. Overburden failure characteristics and fracture evolution rule under repeated mining with multiple key strata control. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 28029. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14068-y (2025).

Li, S., Liu, R., Zhang, Q. & Zhang, X. Protection against water or mud inrush in tunnels by grouting: A review. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 8(5), 753–766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2016.05.002 (2016).

Du, X. et al. A state-of-the-art review on the study of the diffusion mechanism of fissure grouting. Appl. Sci. 14(6), 2540. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14062540 (2024).

Duan, H. et al. Analysis of grout radial propagation in water-saturated rough-walled rock fractures. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 190, 106101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2025.106101 (2025).

Zimmerman, R. W. & Bodvarsson, G. S. Hydraulic conductivity of rock fractures. Transp. Porous Media 23(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00145263 (1996).

Lomiz, G. M. Flow in Fractured Rock (Gesenergoizdat, 1951).

Snow, D. T. A Parallel Plate Model of Fractured Permeable Media (University of California, 1965).

Louis, C. Rock Hydraulics (Springer, 1974).

Witherspoon, P. A., Wang, J. S. Y., Iwai, K. & Gale, J. E. Validity of cubic law for fluid flow in a deformable rock fracture. Water Resour Res. 16(6), 1016–1024. https://doi.org/10.1029/WR016i006p01016 (1980).

Zimmerman, R. W., Al-Yaarubi, A., Pain, C. C. & Grattoni, C. A. Non-linear regimes of fluid flow in rock fractures. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 41(3), 384–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2003.12.045 (2004).

Edirisinghe, E. A. A. V. & Perera, M. S. A. Review on the impact of fluid inertia effect on hydraulic fracturing and controlling factors in porous and fractured media. Acta Geotech. 19(12), 7923–7965. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-024-02389-7 (2024).

Zhou, X. et al. Effects of geometrical feature on Forchheimer-flow behavior through rough-walled rock fractures. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 43(11), 2075–2083. https://doi.org/10.11779/CJGE202111014 (2021).

Wang, Z., Zhou, C., Wang, F., Li, C. & Xie, H. Channeling flow and anomalous transport due to the complex void structure of rock fractures. J. Hydrol. 601, 126624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2021.126624 (2021).

Teng, T. et al. Water injection softening modeling of hard roof and application in Buertai coal mine. Environ. Earth Sci. 84(2), 54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-024-12068-1 (2025).

Chen, Y., Zhou, J., Hu, S., Hu, R. & Zhou, C. Evaluation of Forchheimer equation coefficients for non-Darcy flow in deformable rough-walled fractures. J. Hydrol. 529, 993–1006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2015.09.021 (2015).

Gao, M., Zhu, X., Zhang, C., Li, Y. & Oh, J. A new theoretical model for the nonlinear flow in a rough rock fracture under shear. Comput. Geotech. 165, 105851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2023.105851 (2024).

Gao, H., Qing, L., Ma, G. & Zhang, D. Numerical investigation on grout spread and grouting parameter analysis in fracture with flowing water. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 221, 211401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoen.2022.211401 (2023).

Ruan, W. Research on diffusion of grouting and basic properties of grouts. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 1, 69–73 (2005).

Lavrov, A. Non-Newtonian Fluid Flow in Rough-Walled Fractures: A Brief Review (OnePetro, 2013). Accessed 25 Aug 2024.

Zhao, W., Ren, Z., Zhang, J., Li, Y. & Zhang, X. Characteristics of binary low-pH grouting material containing superfine cement and silica fume. Bull. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 42(4), 1156–1165. https://doi.org/10.16552/j.cnki.issn1001-1625.20230302.003 (2023).

Dai, G. & Byron, B. R. Radial flow of a Bingham fluid between two fixed circular disks. J. Non-Newton Fluid Mech. 8(3), 349–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-0257(81)80031-6 (1981).

Liu, J. Proceedings of the China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research, Vol. 8, 8 (1982).

Gustafson, G. & Stille, H. Prediction of groutability from grout properties and hydrogeological data. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 11(3), 325–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/0886-7798(96)00027-2 (1996).

Gustafson, G. & Stille, H. Stop criteria for cement grouting. Felsbau Z. Geomech. Ingenieurgeol. Bauwes Bergbau 25(3), 62–68 (2005).

Rafi, J. & Stille, H. A method for determining grouting pressure and stop criteria to control grout spread distance and fracture dilation. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 112, 103885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2021.103885 (2021).

El Tani, M. Grouting rock fractures with cement grout. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 45(4), 547–561. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-012-0235-0 (2012).

Zou, L., Håkansson, U. & Cvetkovic, V. Critical analysis of Bingham fluid radial flow in smooth fractures with application to rock grouting. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2019.12.021 (2020).

Xie, H. Fractal geometry and its application to soil and rock materials. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 14(1), 14–24 (1992).

Mu, W., Li, L., Yang, T., Yu, G. & Han, Y. Numerical investigation on a grouting mechanism with slurry-rock coupling and shear displacement in a single rough fracture. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 78(8), 6159–6177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-019-01535-w (2019).

Ding, W., Duan, C. & Zhang, Q. Experimental and numerical study on a grouting diffusion model of a single rough fracture in rock mass. Appl Sci. 10(20), 7041. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10207041 (2020).

Zhengzheng, C. et al. Diffusion evolution rules of grouting slurry in mining-induced cracks in overlying strata. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-025-04445-4 (2025).

Wang, Y., Yang, P., Li, Z. T., Wu, S. J. & Zhao, Z. X. Experimental-numerical investigation on grout diffusion and washout in rough rock fractures under flowing water. Comput. Geotech. 126, 103717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2020.103717 (2020).

Wang, X., Zhang, L., Li, Z., Wang, H. & Li, X. Grouting characteristic in rock fractures with different structural properties: Apparatus design and experimental study. Phys. Fluids 36(9), 093114. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0225481 (2024).

Li, B., Tang, M., Wang, Y. & Zou, L. Analysis of Herschel–Bulkley fluids flow through rough-walled rock fractures. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 162, 106636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2025.106636 (2025).

Hollmen, K. R20 Programme: The Development of Grouting Technique. Stop Criteria and Field Tests (Posiva Oy, 2008).

Hernqvist, L. et al. Analyses of the grouting results for a section of the APSE tunnel at Äspö Hard Rock Laboratory. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 46(3), 439–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2008.02.003 (2009).

Tsuji, M. Post-grouting experiences for reducing groundwater inflow at 500 m depth of the Mizunami Underground Research Laboratory, Japan. Procedia Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2017.05.216 (2017).

RodríguezdeCastro, A. R. & Radilla, G. Flow of yield stress and Carreau fluids through rough-walled rock fractures: Prediction and experiments. Water Resour. Res. 53(7), 6197–6217. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017WR020520 (2017).

Zou, L., Tang, M. & Li, B. Bingham and Herschel–Bulkley fluids flow regimes in rough-walled rock fractures. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 180, 105832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2024.105832 (2024).

Gao, H., Ma, G., Qing, L. & Zhang, D. Effect of shear-thinning rheology on transition of nonlinear flow behavior in rock fracture. Comput. Geotech. 175, 106653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2024.106653 (2024).

Li, K., Wang, Z., Liu, J. & Li, W. Unidirectional and radial nonlinear flow of grout in rough fractures: Flow models and nonlinear characteristics. Comput. Geotech. 179, 106997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2024.106997 (2025).

Lavrov, A. Flow of non-Newtonian fluids in single fractures and fracture networks: Current status, challenges, and knowledge gaps. Eng. Geol. 321, 107166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2023.107166 (2023).

Einstein, H. H. Fractures: Tension and shear. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 54(7), 3389–3408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-020-02243-8 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Geological disposal of high level radioactive waste in China: Progress and breakthrough during 2019–2024. At. Energy Sci. Technol. 58(S2), 217–230. https://doi.org/10.7538/yzk.2024.youxian.0439 (2024).

Brown, S. R. & Scholz, C. H. Broad bandwidth study of the topography of natural rock surfaces. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 90(B14), 12575–12582. https://doi.org/10.1029/JB090iB14p12575 (1985).

Liu, R., He, M., Huang, N., Jiang, Y. & Yu, L. Three-dimensional double-rough-walled modeling of fluid flow through self-affine shear fractures. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 12(1), 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2019.09.002 (2020).

Molz, F. J., Liu, H. H. & Szulga, J. Fractional Brownian motion and fractional Gaussian noise in subsurface hydrology: A review, presentation of fundamental properties, and extensions. Water Resour. Res. 33(10), 2273–2286. https://doi.org/10.1029/97WR01982 (1997).

Liu, H., Bodvarsson, G. S., Lu, S. & Molz, F. J. A corrected and generalized successive random additions algorithm for simulating fractional Levy motions. Math. Geol. 36(3), 361–378. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:MATG.0000028442.71929.26 (2004).

Odling, N. E. Natural fracture profiles, fractal dimension and joint roughness coefficients. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 27(3), 135–153. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01020307 (1994).

Brown, S. R. Fluid flow through rock joints: The effect of surface roughness. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 92(B2), 1337–1347. https://doi.org/10.1029/JB092iB02p01337 (1987).

Zimmerman, R. W. & Paluszny, A. Fluid Flow in Fractured Rocks (Wiley, 2024).

Papanastasiou, T. C. & Boudouvis, A. G. Flows of viscoplastic materials: Models and computations. Comput. Struct. 64(1), 677–694. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0045-7949(96)00167-8 (1997).

Deng, S. et al. Simulation of grouting process in rock masses under a dam foundation characterized by a 3D fracture network. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 51(6), 1801–1822. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-018-1436-y (2018).

Kronlöf, A. Injection Grout for Deep Repositories—Low-pH Cementitious Grout for Larger Fractures: Testing Technical Performance of Materials (Posiva Oy, 2005).

Saeidi, O., Stille, H. & Torabi, S. R. Numerical and analytical analyses of the effects of different joint and grout properties on the rock mass groutability. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 38, 11–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2013.05.005 (2013).

Wasp, E. J., Kenny, J. P. & Gandhi, R. L. Solid–Liquid Flow: Slurry Pipeline Transportation (1977). https://www.osti.gov/etdeweb/biblio/6938902. Accessed 4 Nov 2025.

Xia, K., Zhao, C. & Liu, J. Technical Specification for Cement Grouting of Hydraulic Structures (2020).

Li, S. et al. Research on advantage-fracture grouting mechanism and controlled grouting method in water-rich fault zone. Rock Soil Mech. 35(3), 744–752. https://doi.org/10.16285/j.rsm.2014.03.030 (2014).

Lu, Q., Yang, Z., Yang, Z. & Yu, R. Penetration grouting mechanism of Binham fluid considering diffusion paths. Rock Soil Mech. 43(2), 385–394. https://doi.org/10.16285/j.rsm.2021.1224 (2022).

Frigaard, I. A. & Ryan, D. P. Flow of a visco-plastic fluid in a channel of slowly varying width. J. Non-Newton Fluid Mech. 123(1), 67–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnnfm.2004.06.011 (2004).

Zhang, M., Prodanović, M., Mirabolghasemi, M. & Zhao, J. 3D microscale flow simulation of shear-thinning fluids in a rough fracture. Transp. Porous Media 128(1), 243–269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11242-019-01243-9 (2019).

Yang, Q. et al. Grouting anchor cable active advanced support technology for mining roadways. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 16178. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-43483-2 (2023).

Zhu, J. Impact of yield stress and fractal characteristics on the flow of Bingham fluid through fracture network. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 195, 107637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2020.107637 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by the China Atomic Energy Authority (CAEA) through the Geological Disposal Program.

Funding

This project is funded by the China Atomic Energy Authority’s scientific research project “Research on Key Technologies for Deep Rock Excavation in Underground Research Laboratories” (FZ2105).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xifeng Li: Conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, software, validation, writing-original draft. Weiquan Zhao: Funding acquisition, investigation, supervision, writing—review and editing. Jinjie Zhang: Project administration, supervision, writing—review and editing. Yahui Ma Methodology, software. Liang Chen: Resources, supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., Zhao, W., Zhang, J. et al. Nonlinear flow characteristics of cement grout in fractures with varying geometries. Sci Rep 16, 982 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30580-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30580-7