Abstract

Herbicide-resistant grass weeds, including blackgrass (Alopecurus myosuroides Huds.) and silky windgrass (Apera spica‑venti (L.) P.Beauv), pose an escalating challenge to sustainable cereal production in Europe. This study examined temperature‑dependent germination dynamics of herbicide‑resistant (HR) and susceptible (S) biotypes of both species collected from Polish agroecosystems. Germination was tested under five temperatures: constant 5, 10, 15, and 20 °C, and alternating 15/5°C. Resistance groups were evaluated using the area under the germination curve (AUC), a cumulative measure that integrates both the speed and extent of germination. In both species, temperature strongly modulated germination dynamics. Multiple‑resistant blackgrass biotypes exhibited higher germination rates at certain temperatures, suggesting distinct physiological responses among resistance types rather than uniform adaptation across temperature ranges. Conversely, multiple-resistant silky windgrass biotypes (e.g., M1235) germinated vigorously at 5 °C. Still, they declined at warmer temperatures, achieving the highest AUC at 5 °C but the lowest at 20 °C (a difference exceeding 74 units), suggesting a temperature-specific shift in dormancy release or germination physiology. Susceptible groups germinated more slowly and consistently across temperatures. These contrasting thermal responses reveal that herbicide-resistant populations can exploit different temperature niches, potentially influencing their emergence timing and competitive ability in the field. Understanding these patterns is essential for developing climate-adapted, resistance-aware weed management strategies, including optimized sowing schedules and integrated, non-chemical control measures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Blackgrass (Alopecurus myosuroides Huds.) and silky windgrass (Apera spica-venti (L.) P. Beauv.) are the two most dominant monocotyledonous winter weeds in Poland. These species are major contributors to yield loss in key crops such as winter wheat and oilseed rape1,2. Both weed species exhibit similar biological traits, including autumn emergence, inflorescence development above the crop canopy, and pre-harvest seed shedding.

In Western Europe, blackgrass is one of the most economically damaging weeds in winter cereals. It displays high competitiveness, with economic thresholds ranging from 7.5 to 30 plants m⁻², depending on the cropping system and evaluation methods3,4,5. Moss5 highlighted that in high-risk systems—such as early sowing, minimal tillage, or heavy soils—even one plant per square meter may require herbicide treatment. Each blackgrass plant can produce 2–20 inflorescences, with approximately 100 grains per spikelet, and up to 80% of the population typically germinates in autumn (September–November)5,6,7. Previous studies have reported optimal germination between 15 and 25 °C8, which generally reflects conditions for non-dormant, after-ripened seed. Germination of blackgrass is strongly temperature-dependent and closely linked to the dormancy status of the seed. Recent research9 demonstrated that freshly harvested, dormant blackgrass seeds germinate only within a narrow temperature range (6–9 °C), while after-ripened, non-dormant seeds can germinate across a much broader thermal window up to 20–22 °C. Moreover, Holloway et al. (2025) demonstrated that the maternal environment and vernalization can significantly alter the dormancy depth in Alopecurus myosuroides via epigenetic regulation. These findings highlight the strong influence of environmental conditions on dormancy and further justify our decision to work with after-ripened, non-dormant seed batches, ensuring that observed differences in germination dynamics reflect biotypic variation rather than maternal or dormancy effects10. This temperature sensitivity explains the pronounced autumn emergence pattern of the species in temperate climates. In the present study, we therefore used fully after-ripened, non-dormant seed batches to focus on inherent biotypic differences in germination dynamics, independent of dormancy effects. Silky windgrass is particularly problematic in Central and Eastern Europe—including Poland, the Czech Republic, Lithuania, and Germany—especially on sandy soils11,12,13,14,15. It produces abundant seeds, with individual plants generating between 1,000 and 16,000 grains16,17. The economic threshold for silky windgrass in Poland is estimated at 5–20 plants m⁻² or 25–49 panicles m⁻²18,19.

Both species have evolved resistance to multiple herbicide modes of action. Blackgrass is among the top 15 most herbicide-resistant weeds globally, showing resistance to ACCase inhibitors (HRAC/WSSA group A/1), ALS inhibitors (B/2), PSII inhibitors (C1/5 and C2/7), microtubule assembly inhibitors (K1/3), VLCFA synthesis inhibitors (K3/15), and lipid synthesis inhibitors (N/8)20,21. Silky windgrass has also evolved resistance to ACCase, ALS, and PSII inhibitors20. In the UK, herbicide-resistant blackgrass is estimated to cause £400 million in annual losses and 800,000 tonnes of lost crop yield22. In Poland, its management costs exceed $300 per hectare, while preventive strategies can cost around $146 per hectare23.

Integrated weed management (IWM), which incorporates non-chemical strategies, is essential for addressing the dual challenges of herbicide resistance and environmental sustainability. A thorough understanding of weed biology—especially germination behavior—is essential for effective control during early growth stages, when physical or mechanical methods are particularly successful. Therefore, understanding germination dynamics (such as germination rate, final germination, temperature range, and other factors) provides valuable insights into the optimal timing for applying each control method throughout the growing season. Additionally, assessing the competitive potential and growth patterns of resistant versus susceptible groups helps evaluate fitness and predict population dynamics1,24,25,26,27.

While numerous indices exist to quantify germination—such as final germination percentage (GP), mean germination time (MGT), and time to 50% germination (T₅₀)—dynamic measures that reflect cumulative progress over time are particularly valuable for comparing responses under environmental stress28. Integrative metrics that capture germination progress over time, such as germination dynamics, are especially useful when comparing biological responses of different biotypes exposed to factors like temperature or herbicidal pressure. Although time-to-event models are increasingly applied, the cumulative approach remains suitable for summarizing germination progress when the goal is to compare overall thermal responses across multiple resistance groups. One such metric is the area under the curve (AUC), adapted from disease progression studies (AUDPC), which characterizes the shape and timing of germination across time29,30. Traditional germination metrics, such as final germination percentage or mean germination time, provide valuable but static measures and fail to capture the cumulative dynamics of the process. In contrast, dynamic indicators such as the AUC enable simultaneous comparison of both the rate and extent of germination across treatments. Recent advances, however, indicate that germination data can also be effectively analyzed using time-to-event or survival models, which account for censoring environmental variability31,32. Together, these analytical approaches—AUC-based assessments and time-to-event modeling—offer complementary insights into how temperature and resistance interact to influence weed emergence dynamics.

The AUC is calculated using the trapezoidal rule applied to cumulative germination data. Unlike point-based indices, it captures the overall shape of the germination curve, integrating both early and delayed responses. This method is statistically robust and can be easily integrated into mixed models or nonlinear regression frameworks. As demonstrated in recent studies33,34,35, AUC has been successfully applied to assess germination and plant growth, phenology, and physiological stress responses. In our study, we employed the AUC approach to assess the germination dynamics of resistant and susceptible groups of biotypes of blackgrass and silky windgrass across a temperature gradient. This method enabled us to capture detailed germination profiles and quantitatively compare their performance under contrasting thermal conditions.

Results

Germination dynamics of resistance groups in Blackgrass

Temperature regimes significantly influenced the cumulative dynamics of germination, as reflected in AUC values for blackgrass resistance groups (Fig. 1). Detailed data are presented in Supplementary Table S1. AUC is a dimensionless, cumulative measure integrating both germination speed and completeness; thus, values can exceed 100 when germination is both rapid and extensive. The lowest cumulative germination dynamics, corresponding to low AUC values, were consistently observed at 5 °C, with minimal statistical differences among the resistance groups (ANOVA: F = 1.279; p = 0.2452), suggesting uniform suppression of germination dynamics at low temperatures. At 10 °C, variation among the resistance groups became statistically significant (F = 2.3413; p = 0.01276), with resistant groups M15 and M13 showing the highest AUC values (97.4 and 86.1, respectively), while germination dynamics of resistance group Sg5 were the lowest (AUC = 31.7). Tukey’s HSD confirmed significant differences between these resistance groups. Differences expanded at 15 °C (F = 4.5773; p = 8.52e-06**), with resistance groups M123 and M15 again of highest cumulative germination dynamics (AUC > 130). Resistance groups Sg2 and Sg3 recorded the lowest cumulative germination dynamics. Similar patterns were observed at 20 °C (F = 4.7527; p = 4.63e-06**), where resistance group M13 stood out (AUC = 163), confirming temperature-enhanced divergence of germination dynamics. Under alternating 5/15°C temperatures, resistance group M15 retained a marked germination dynamics (AUC = 133.2), statistically different from most single-resistance groups (F = 5.8303; p = 1.32e-07**).

Germination dynamics of blackgrass (Alopecurus myosuroides) biotypes expressed as area under the germination curve (AUC) across five temperatures (5 °C, 10 °C, 15 °C, 20 °C, and alternating 15/5°C). Bars represent mean ± SE (n = 4). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences among temperature treatments within each resistance group (Tukey’s HSD, p < 0.05). Resistance groups (axis X): S – susceptible; Sg – single-resistant; M – multiple-resistant; 1,2,3,5 – HRAC/WSSA groups.

Representative germination curves (Fig. 2) illustrate typical differences in cumulative germination between resistant and susceptible biotypes of blackgrass and silky windgrass under controlled conditions. Multiple-resistant groups reached higher cumulative germination earlier than single-resistant and susceptible ones, resulting in greater AUC values that integrate both the rate and final percentage of germination.

Schematic cumulative germination curves illustrating differences in germination dynamics between representative resistance groups of Alopecurus myosuroides (Alo) and Apera spica-venti (Ape) under controlled conditions. Curves reflect relative germination rates and cumulative germination percentages consistent with the observed AUC rankings in the experiment (higher AUC → faster or more complete germination). Nonlinear regression using a three-parameter log-logistic model (LL.3) was implemented in the drc package. The AUC (area under the curve) integrates both the speed and extent of germination over time, allowing comparison between resistant and susceptible groups. Abbreviations: M – multiple resistant, Sg – single resistant, S – susceptible, 1,2,3,5 – refer to HRAC/WSSA groups of herbicides.

Contrast analysis in Blackgrass resistance groups

The contrast estimates comparing multiple-resistant groups to the average of all single-resistant groups confirmed the temperature-dependent germination dynamics (Table 1). No significant differences were found at 5 °C. At 15 °C, contrasts revealed the strongest and most consistent differences, particularly for the groups M15, M13, M123, and M125 (p < 0.05). At 10 °C and 5/15°C, M15 consistently showed higher germination dynamics than the single-resistant group, supporting previous findings (Fig. 1). At 20 °C, some contrasts (e.g., groups M13 and M123) remained significant. However, the overall pattern was less pronounced than at 15 °C.

Germination dynamics of silky windgrass resistance groups

Silky windgrass also showed temperature-dependent variation of germination dynamics (Supplementary Table S2). The lowest germination dynamics (AUC values) at 5 °C were observed in the susceptible (S) and Sg1 resistance groups (AUC = 54 and 37.5, respectively), whereas the resistance group M1235 showed the highest germination dynamics (AUC = 163.6; p < 2.2e-16**). This group’s germination dynamics declined at 20 °C (AUC = 88.5; p = 0.004025*) (Fig. 2).

The most statistically significant differences in germination dynamics between the resistance groups of silky windgrass occurred at 5 °C and 10 °C, confirming temperature as a key differentiator. While differences in germination dynamics between the resistance groups at 15 °C bordered significance (p = 0.05678), those at 20 °C and alternating 5/15°C were significant (p < 0.005).

Germination dynamics of silky windgrass (Apera spica-venti) biotypes expressed as area under the germination curve (AUC) across five temperatures (5 °C, 10 °C, 15 °C, 20 °C, and alternating 15/5°C). Bars represent mean ± SE (n = 4). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences among temperature treatments within each resistance group (Tukey’s HSD, p < 0.05). Resistance groups (X-axis): S – susceptible; Sg – single-resistant; M – multiple-resistant; 1, 2, 3, 5 – HRAC/WSSA groups.

The greatest variation in germination dynamics was observed at 10 °C (Fig. 3). At this temperature, the group M125 showed the highest germination dynamics, but no significant differences were detected among M125, M1235, M13, M23, and Sg3. The susceptible group (S) showed the lowest germination dynamics. At 15 °C, the resistance group M125 also had the highest germination dynamics, while the lowest values were recorded for the groups: S, Sg1, Sg2, M12, M123, and M1235, though statistical separation among these groups was limited.

At 20 °C, significant differences in germination dynamics were found only between the groups M12, M23 (highest), and M1235 (lowest). Remarkably, the group M1235, which performed best at 5 °C, exhibited the lowest germination dynamics at 20 °C. The difference in germination dynamics for this group between the lowest and highest temperatures exceeded 74 units.

Contrast analysis in silky windgrass resistance groups

For group M1235, significant differences were observed compared with the average of single-resistant groups at both 5 °C and 20 °C (P < 0.01). At 15/5°C, significant differences emerged between S and Sg3, with S showing notably lower germination dynamics. Similar trends were found at 15 °C and 20 °C. Overall, the susceptible group of silky windgrass consistently exhibited the lowest germination dynamics (Table 2).

Heatmap of least-squares mean AUC values

Heatmap of least-squares mean AUC values (area under the germination curve) across five temperatures (5 °C, 10 °C, 15 °C, 20 °C, and 15/5°C) is presented in Fig. 4. Lighter shading corresponds to higher cumulative germination (AUC). Each cell represents the mean AUC for a given resistance group and temperature. Multiple-resistant groups (M13, M15, M1235) generally exhibited higher AUCs than single-resistant (Sg) and susceptible (S) groups, indicating pronounced temperature-dependent divergence in germination behavior. Collectively, these results demonstrate consistent temperature-dependent variation in cumulative germination performance between resistance groups, supporting subsequent discussion on ecological and adaptive implications.

Temperature-dependent divergence in germination dynamics of herbicide-resistant and susceptible biotypes of blackgrass (Alopecurus myosuroides) and silky windgrass (Apera spica-venti). Higher values (green shading) corresponds to higher cumulative germination (AUC). Abbreviations: Please see legend under Fig. 1.

Discussion

Germination is a multifaceted biological process shaped by both genetic traits and environmental cues. In our study, temperature influenced germination dynamics across blackgrass and silky windgrass resistance groups. This observation aligns with foundational findings that water, oxygen, light, temperature, and nitrate are pivotal regulators of germination, with temperature often acting as the principal driver in temperate climates36,37.

Multiple-resistant blackgrass groups (e.g., M13, M15, M123) exhibited higher germination dynamics across temperatures ranging from 10 to 20 °C. These patterns suggest potential physiological differences among resistance groups rather than direct evidence of adaptive advantages or absence of fitness costs. Further field studies are required to determine whether differences in germination dynamics translate into measurable fitness outcomes. The exceptional performance of the M15 population under alternating temperatures (AUC = 133.2 at 15/5°C) may reflect greater ecological plasticity38,39 or differences in residual dormancy among seed batches. Although all seeds were after-ripened under controlled conditions to ensure nondormancy, subtle population-specific variation in dormancy release cannot be fully excluded.

Statistical contrasts confirmed that M15 and M123 significantly outperformed single-resistant and susceptible groups at 10, 15, and 15/5°C. These findings underscore the potential for early-season dominance by certain multiple-resistant biotypes, which may enhance their persistence under herbicide selection pressure.

Silky windgrass exhibited more complex germination dynamics. Notably, the M1235 group germinated vigorously at 5 °C (AUC = 163.6), outperforming all other groups. However, its germination dynamics declined substantially at 20 °C (AUC = 88.5), indicating a temperature-specific trade-off. This behavior may provide a competitive advantage during early autumn sowing but reduce fitness during warmer late-autumn or spring emergence periods40.

Such temperature-specific responses likely reflect a balance between dormancy regulation and germination efficiency. Resistance-linked alleles could indirectly influence these traits through pleiotropy, as suggested in previous studies38,39. For example, M1235’s higher germination dynamics at low temperatures may be linked to reduced dormancy thresholds but at the cost of performance in warmer conditions—a hypothesis worth exploring in future fitness cost studies41.

In general, the susceptible biotypes showed lower germination dynamics, particularly in blackgrass at 15–20 °C and across all temperatures in silky windgrass. This supports the concept that herbicide resistance can be associated with traits that increase weed competitiveness under specific environmental conditions1.

From a management perspective, our findings highlight the need for resistance-informed, climate-adapted control strategies. For instance, delaying sowing or increasing crop competitiveness may help suppress early-emerging blackgrass biotypes like M15, while strategies targeting cold-adapted silky windgrass biotypes (e.g., M1235) may require modifications to pre-sowing practices. Collectively, these insights emphasize the importance of understanding the ecological and physiological traits associated with herbicide resistance. Such knowledge can speed the development of integrated weed management programs that exploit temperature-driven weaknesses in germination of resistant populations.

Germination timing is a critical fitness trait for annual weeds. Early germinating individuals typically outcompete crops for resources and may escape pre-emergent herbicide applications42,43. Our findings suggest that certain resistant groups of both species, particularly those with multiple resistance, may possess enhanced germination dynamics contributing to their persistence and spread. This is particularly concerning given the challenges in controlling blackgrass with existing chemicals.

Given the observed germination dynamics, non-chemical weed management strategies should be tailored with a strong understanding of local resistance and thermal conditions. Cultural practices such as delayed sowing, rotational tillage, or competitive crop varieties might exploit the ecological weaknesses of susceptible biotypes or limit the establishment of highly fit resistant ones.

Our findings show that, while all resistance groups responded to temperature, the magnitude and direction of their responses varied significantly. For example, the unexpectedly high germination dynamics of the silky bentgrass M1235 group at 5 °C may reflect a reduced dormancy threshold or altered thermal requirement—traits that could confer a selective advantage in early autumn sowing. This group diminished germination dynamics at higher temperatures, further supporting the idea of a temperature-specific fitness trade-off, potentially tied to pleiotropic effects of resistance alleles.

It is suggested that the ecological success of herbicide-resistant weeds often depends on whether the resistance mechanism carries a fitness cost44. Our findings demonstrate that ACCase-resistant biotypes germinate with lower dynamics at suboptimal temperatures, a potential manifestation of this fitness cost. In contrast, P450-based resistance did not reduce germination dynamics. It is consistent with the notion that some non-target-site resistance mechanisms may evolve without associated fitness penalties, allowing them to spread rapidly in agroecosystems.

Accurate quantification of fitness-related traits, including germination rate, time to 50% of germination (tG₅₀), and environmental responsiveness, is essential for elucidating the evolutionary dynamics of herbicide resistance. Our results support the inclusion of these traits in resistance-monitoring frameworks to inform proactive, predictive weed management. We recommend integrated strategies tailored to biotype-specific emergence patterns, such as: (i) Adjusting sowing dates to avoid peak emergence periods, (ii) Implementing tillage practices targeting shallowly buried seeds, (iii) Applying pre-sowing light exposure or alternating temperature treatments, (iv) Aligning herbicide applications with germination profiles.

While this study focused on temperature-driven germination responses across different resistance types under controlled conditions, other ecological factors (e.g., light quality, soil moisture, and seed burial depth) were held constant and thus not evaluated. These environmental variables are likely to interact with thermal cues, influencing emergence timing and competitive ability in the field. To better understand these interactions, future research should include field validation of AUC-based laboratory findings, dormancy profiling across a broader range of biotypes, and genomic exploration of thermal germination thresholds under variable environmental conditions.

Methods

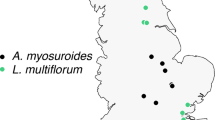

Plant material

Seeds of blackgrass and silky windgrass were collected from winter cereal fields across Poland between 2019 and 2021. The biotypes representing susceptible (S), single-resistant (Sg), and multiple-resistant (M) groups were collected from arable fields across Poland. A total of 31 blackgrass and 38 silky windgrass biotypes were tested, representing diverse regions and cropping histories. Herbicide resistance was confirmed through dose–response bioassays, and resistance profiles were categorized following HRAC/WSSA guidelines. Experiments were carried out in seven collaborating laboratories, each testing subsets of biotypes under identical experimental conditions and protocols.

Resistance classification and bioassay

Resistance status was confirmed via dose-response bioassays conducted under controlled glasshouse conditions using seven herbicide doses (0.5–32 times the recommended field rate) and a water-sprayed control45. Herbicides representing various HRAC/WSSA groups were tested (Table 3). Aboveground fresh biomass of weeds was measured to fit logarithmic dose–response curves and to calculate the ED₅₀, i.e., the dose causing a 50% reduction in plant fresh biomass, using the drc package in R46,47. The bioassay protocol followed standardized procedures previously described in related studies conducted within this research framework48,49.

Commercially available herbicides containing fenoxaprop-P, pinoxaden, pyroxulam, pendimethalin, and chlorotoluron were used in the dose–response bioassays (characterized in Table 3). The biotype characteristics, including their resistance classification, are summarized in Tables 4 and 5.

The aim of this study was not to reclassify resistance levels but to analyze germination dynamics across already-characterized resistance groups. Resistance classification was therefore based solely on bioassay results. As molecular analyses (genotyping) were beyond the scope of the present study, the specific target-site or non-target-site resistance mechanisms were not determined.

Biotypes were classified as susceptible when ED₅₀ values were within ca. 0.25–0.5 times the field dose. Tables 4 and 5 summarize the characteristics of selected blackgrass and silky windgrass biotypes, categorized by resistance type, used in the germination assays.

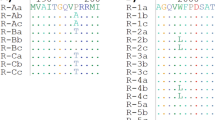

Based on the dose-response experiments, the following types of resistance were confirmed for the tested biotypes, i.e., single: Sg1 – to fenoxaprop-P or pinoxaden; Sg2 - to piroxulam; Sg3 - to pendimethaline; Sg5 - to chlorotoluron, and multiple: M12; M13; M15; M23; M123; M125 or M1235, to the tested herbicides from corresponding HRAC/WSSA groups. Tables 2 and 3 present characteristics of blackgrass and silky windgrass biotypes chosen for the germination experiments.

Germination experiments

All seed batches were after-ripened under controlled laboratory conditions to minimize dormancy-related effects. Seeds were stored dry in paper envelopes at room temperature (20 ± 2 °C) and 50–55% relative humidity for 6 months, then pre-chilled at 4 °C for 48 h to synchronize germination onset, ensure uniform imbibition, and minimize residual dormancy variation. This procedure followed established protocols confirming effective dormancy release in blackgrass and silky windgrass after dry storage9,32. Although this approach ensured high germination potential, minor population-specific differences in dormancy release cannot be completely excluded.

Two independent germination experiments were conducted in parallel in seven collaborating laboratories for blackgrass and silky windgrass biotypes. Before incubation, seeds were surface-sterilized in 1% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) for 5 min and rinsed three times with sterile distilled water. Preliminary germination tests confirmed nondormancy (> 90% germination at 20 °C under constant light), indicating that after-ripening effectively released seed dormancy.

After pre-chilling, seeds (25 per dish) were placed on two layers of moistened Whatman filter paper in 9 cm sterile glass Petri dishes, using 5 mL of distilled water per dish to maintain constant humidity. Dishes were sealed with parafilm to prevent desiccation and arranged in a completely randomized design. Germination tests were conducted in controlled climate chambers (Friocell EVO 707, MMM Medcenter Einrichtungen GmbH, Munich, DE) under five temperatures: 5 °C, 10 °C, 15 °C, 20 °C (constant), and 15/5°C (alternating day/night). Incubation was carried out in darkness. Each treatment (biotype × temperature) was replicated three times (three Petri dishes), and the entire experiment was repeated twice independently to confirm reproducibility.

A seed was considered germinated when the radicle protruded at least 1 mm, and germination was recorded daily for 21 days. This protocol followed standardized seed testing practices consistent with ISTA50 and commonly used approaches for weed seed dormancy and germination assessment31,51. Although this procedure ensured high germination potential across all populations, minor population-specific differences in dormancy release cannot be completely excluded.

Statistical analysis

Preliminary analyses revealed no significant inter-laboratory variation. Therefore, the biotypes for each weed species were grouped by the resistance type into the resistance groups for further analyses. Germination dynamics were assessed using the area under the germination curve (AUC) following the trapezoidal rule52:

n is the number of observations, y is the percentage of germinated seeds, and t is the time in days.

This approach, adapted from the area under the disease progress curve, is based on traditional germination metrics, such as final germination percentage or mean germination time, which provide valuable but static measures and fail to capture the cumulative dynamics of the process. In contrast, dynamic indicators such as the AUC enable simultaneous comparison of both the rate and extent of germination across treatments. Recent advances, however, indicate that germination data can also be effectively analyzed using time-to-event or survival models, which account for censoring and environmental variability31,32. Together, these analytical approaches—AUC-based assessments and time-to-event modeling—offer complementary insights into how temperature and resistance interact to influence the weed emergence dynamics curve (AUDPC), which integrates both the speed and extent of germination over time.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Type II sums of squares was used to evaluate the effect of resistance type (resistance group) on AUC, accounting for laboratory blocking. Residuals were assessed for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.

Due to the unbalanced factorial design, least squares means (LS means) were calculated to evaluate main effects and linear contrasts53. LS means were adjusted for unbalanced data as per54. Directed linear contrasts comparing individual test biotypes against a defined control group were computed based on LS means53. Pairwise comparisons were performed using Tukey’s HSD55. All analyses were conducted at α = 0.05 using R (version 4.2.2), employing the lsmeans and multcomp packages.

Ethical compliance and plant material Documentation

The plant material used in this study was collected from winter cereal fields across Poland, with permission obtained from landowners or managing agricultural institutions. All participating institutions listed in the author affiliations are licensed and authorized to conduct research on wild plant material, including seed collection, following Polish and European Union legislation. Plant species (Alopecurus myosuroides and Apera spica-venti) were taxonomically identified by the authors listed in the manuscript based on weed morphological characteristics and field knowledge.

Voucher specimens for the collected weed biotypes have been deposited in the seed bank of the Institute of Plant Protection – National Research Institute in Poznań, Poland, and are available under ID number: [ALOMY-01 – ALOMY-31] for biotypes of Alopecurus myosuroides (given in Table 4 of the manuscript) and [APESV-01 – APESV-38] for biotypes of Apera spica-venti (given in Table 5 of the manuscript).

All research activities related to plant collection and experimentation complied with institutional, national, and international regulations, including the IUCN Policy Statement on Research Involving Species at Risk of Extinction and the Convention on the Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)56,57.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wenda-Piesik, A. et al. Intra- and interspecies competition of Blackgrass and wheat in the context of herbicidal resistance and environmental conditions in Poland. Sci. Rep. 12, 8720 (2022).

Domaradzki, K., Rola, H. & Jezierska-Domaradzka, A. Changes in floristic composition of segetal weed community in the long-term winter wheat monoculture. Pamietnik Pulawski Pol. https://agris.fao.org/search/en/providers/122651/records/647248b453aa8c896304e935 (2006).

Doyle, C. J., Cousens, R. & Moss, S. R. A model of the economics of controlling alopecurus myosuroides Huds. In winter wheat. Crop Prot. 5, 143–150 (1986).

Zwerger, P. Integrated weed management in developed nations. https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/19972303058 (1996).

Moss, S. R. Black-grass (Alopecurus myosuroides): everything you really wanted to know about black-grass but didn’t know who to ask (Rothamsted Technical Publication). RRA Newsletter https://repository.rothamsted.ac.uk/item/8q627/black-grass-alopecurus-myosuroides-everything-you-really-wanted-to-know-about-black-grass-but-didn-t-know-who-to-ask-rothamsted-technical-publication (2010).

Chavvel, B., Munier-Jolain, N. M., Grandgirard, D. & Gueritaine, G. Effect of vernalization on the development and growth of alopecurus myosuroides. Weed Res. 42, 166–175 (2002).

Maréchal, P. Y., Henriet, F., Vancutsem, F. & Bodson, B. Ecological review of black-grass (Alopecurus myosuroides Huds.) propagation abilities in relationship with herbicide resistance. Biotechnol Agron. Société Environ 16, 103–113 (2012).

Sauerborn, J. & Koch, W. An investigation of the germination of six tropical arable weeds. Weed Res. 28(1), 47-52 (1988).

Holloway, T. et al. Mechanisms of seed persistence in Blackgrass (Alopecurus myosuroides Huds). Weed Res. 64 (3), 237–250 (2024).

Holloway, T. E. et al. Vernalization enforces seed dormancy in the agricultural weed alopecurus myosuroides (Huds). Seed Sci. Res. 35 (2), 126–133 (2025).

Massa, D. et al. Development of a Geo-Referenced database for weed mapping and analysis of agronomic factors affecting herbicide resistance in Apera spica-venti L. Beauv (Silky Windgrass) Agronomy. 3, 13–27 (2013).

Auskalniene, O. & Zadorozhnyi, V. Apera spica-venti (L.) P. Beauv. Resistance to herbicides in Lithuania and Ukraine. Quar Plant. Prot. 50–52. https://doi.org/10.36495/2312-0614.2020.2-3.50-52 (2020).

Hamouzová, K., Košnarová, P., Salava, J., Soukup, J. & Hamouz, P. Mechanisms of resistance to acetolactate synthase-inhibiting herbicides in populations of Apera spica-venti from the Czech Republic. Pest Manag Sci. 70, 541–548 (2014).

AgroAtlas - Weeds - Apera spica-venti (L). Beauv. Silky Bentgrass, Wind-Grass. https://agroatlas.ru/en/content/weeds/Apera_spica-venti/index.html

Adamczewski, K., Kaczmarek, S., Kierzek, R. & Matysiak, K. Significant increase of weed resistance to herbicides in Poland. J Plant. Prot. Res 59(2), 139–150 (2019).

Bitarafan, Z. & Andreasen, C. Seed production and retention at maturity of Blackgrass (Alopecurus myosuroides) and silky windgrass (Apera spica-venti) at wheat harvest. Weed Sci. 68, 151–156 (2020).

Babineau, M., Mathiassen, S. K., Kristensen, M. & Kudsk, P. Fitness of ALS-Inhibitors herbicide resistant population of loose silky bentgrass (Apera spica-venti). Front Plant. Sci 8, 1660 (2017).

Wozniak, A. The influence of agricultural practices on yield and weed infestation of winter triticale. Agron Sci 77(3), 159–171 (2022).

Adamczewski, K. & Matysiak, K. Zmiennosc Biologiczna Apera species i Jej Wrazliwosc Na herbicydy. Prog Plant. Prot. 47, 341–349 (2007).

Heap, I. The International Herbicide-Resistant Weed Database. https://weedscience.org/Home.aspx (2025).

Ghazali, Z., Keshtkar, E., AghaAlikhani, M. & Kudsk, P. Germinability and seed biochemical properties of susceptible and non–target site herbicide-resistant Blackgrass (Alopecurus myosuroides) subpopulations exposed to abiotic stresses. Weed Sci. 68, 157–167 (2020).

Herbicide resistant weed could cost UK. £1 billion a year | Rothamsted Research. https://www.rothamsted.ac.uk/news/herbicide-resistant-weed-could-cost-uk-ps1-billion-year

Orson, J. H. The cost to the farmer of herbicide resistance. Weed Technol. 13, 607–611 (1999).

Vila-Aiub, M. M., Neve, P., Steadman, K. J. & Powles, S. B. Ecological fitness of a multiple herbicide-resistant lolium rigidum population: dynamics of seed germination and seedling emergence of resistant and susceptible phenotypes. J. Appl. Ecol. 42, 288–298 (2005).

Damalas, C. A. & Koutroubas, S. D. Herbicide resistance evolution, fitness cost, and the fear of the superweeds. Plant. Sci. 339, 111934 (2024).

Synowiec, A. et al. Environmental factors effects on winter wheat competition with herbicide-resistant or susceptible silky bentgrass (Apera spica-venti L.) in Poland. Agronomy 11, 871 (2021).

Vila-Aiub, M. M., Neve, P. & Powles, S. B. Fitness costs associated with evolved herbicide resistance alleles in plants. New. Phytol. 184, 751–767 (2009).

Ranal, M. A. & Santana, D. G. de. How and why to measure the germination process? Braz J. Bot. 29, 1–11 (2006).

Campbell, C. L. & Madden, L. V. Introduction To Plant Disease Epidemiology (Wiley, 1990). https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=1799831- References - Scientific Research Publishing.

The `germinationmetrics` Package. A Brief Introduction. https://aravind-j.github.io/germinationmetrics/articles/Introduction.html

Onofri, A., Piepho, H. P. & Kozak, M. Analysing censored data in agricultural research: A review with examples and software tips. Ann. Appl. Biol. 174, 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/aab.12477 (2019).

Jensen, S. M., Wolkis, D., Keshtkar, E., Streibig, J. C. & Ritz, C. Improved two-step analysis of germination data from complex experimental designs. Seed Sci. Res. 30, 194–198. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0960258520000331 (2020).

Loeza-Corte, J., Díaz-López, E., Brena, I. & Campos-Pastelín, J. Orlando-Guerrero, I. Trapezoidal rule as a non-destructive method for determining leaf area duration in soybean. Ing. Agric. Biosist. 6, 5–14 (2014).

Simko, I. IdeTo: spreadsheets for calculation and analysis of area under the disease progress over time data. PhytoFrontiers™ 1, 244–247 (2021).

Talská, R., Machalová, J., Smýkal, P. & Hron, K. A comparison of seed germination coefficients using functional regression. Appl. Plant. Sci. 8, e11366 (2020).

Chachalis, D. & Reddy, K. N. Factors affecting Campsis radicans seed germination and seedling emergence. Weed Sci. 48, 212–216 (2000).

Taylorson, R. B. Environmental and chemical manipulation of weed seed dormancy. Rev. Weed Sci. 3, 135-154 (1987).

Menchari, Y., Chauvel, B., Darmency, H. & Délye, C. Fitness costs associated with three mutant acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase alleles endowing herbicide resistance in black-grass alopecurus myosuroides. J. Appl. Ecol. 45, 939–947 (2008).

Délye, C., Menchari, Y., Michel, S. & Cadet, É. Corre, V. A new insight into arable weed adaptive evolution: mutations endowing herbicide resistance also affect germination dynamics and seedling emergence. Ann. Bot. 111, 681–691 (2013). Le.

Darmency, H., Colbach, N. & Le Corre, V. Relationship between weed dormancy and herbicide rotations: implications in resistance evolution. Pest Manag Sci. 73, 1994–1999 (2017).

Thompson, C. R., Thill, D. C. & Shafii, B. Germination characteristics of Sulfonylurea-Resistant and -Susceptible Kochia (Kochia scoparia). Weed Sci. 42, 50–56 (1994).

Mortimer, A. M. Phenological adaptation in weeds—an evolutionary response to the use of herbicides? Pestic Sci. 51, 299–304 (1997).

Colbach, N., Chauvel, B., Dürr, C. & Richard, G. Effect of environmental conditions on alopecurus myosuroides germination. I. Effect of temperature and light. Weed Res. 42, 210–221 (2002).

Powles, S. B. & Yu, Q. Evolution in action: plants resistant to herbicides. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 61, 317–347 (2010).

Burgos, N. R. et al. Review: confirmation of resistance to herbicides and evaluation of resistance levels. Weed Sci. 61, 4–20 (2013).

Knezevic, S. Z., Streibig, J. C., Ritz, C. & Utilizing R software package for Dose-Response studies: the concept and data analysis. Weed Technol. 21, 840–848 (2007).

Team, R. D. C. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. No Title https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1370294721063650048 (2010).

Stankiewicz-Kosyl, M., Haliniarz, M., Wrochna, M., Synowiec, A., Wenda-Piesik, A.,Tendziagolska, E., … Marcinkowska, K. Herbicide resistance of Centaurea cyanus L.in Poland in the context of its management. Agronomy, 11(10), 1954 (2021).

Stankiewicz-Kosyl, M. & Haliniarz, M. Diversified germination strategies of Centaurea Cyanus populations resistant to ALS inhibitors. Plant Prot. Sci. 59 (4), 379 (2023).

International Seed Testing Association. International Rules for Seed Testing, 2018 Edition (ISTA, 2018).

Bürger, J., Malyshev, A. V., Colbach, N. & Correction Populations of arable weed species show intra-specific variability in germination base temperature but not in early growth rate. Plos One. 19 (7), e0307861 (2024).

Shaner, G. The effect of nitrogen fertilization on the expression of Slow-Mildewing resistance in Knox wheat. Phytopathology 77, 1051 (1977).

Lenth, R. V. Least-squares means: the R package Lsmeans. J. Stat. Softw. 69, 1–33 (2016).

Milliken, G. & Johnson, D. Analysis of Messy Data-Volume 1: Designed Experiments. (2009).

Graves, S. & Dorai-Raj, H. P. P. And L. S. With Help from S (Visualizations of Paired Comparisons, 2024).

IUCN EICAT Categories And Criteria: First Edition, https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/49101 (2020).

Sheikh, P. A. & Corn, M. L. The convention on international trade in endangered species of wild fauna and flora (CITES), Reports, RL32751, Energy & Natural Resources; Environmental Policy (2016). https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/RL32751

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the University of Agriculture in Kraków (subsidy for research activities 010011-D011) and the Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences (“Innovative Scientist” grant N060/0010/20) for contributing to the costs of this publication.

Funding

The National Centre for Research and Development funded this research, contract number: BIOSTRATEG 3/347445/1/NCBR/2017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have contributed to carrying out this research.

K.M.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Writing – Original Draft, Review and Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. A.S.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Writing – Original Draft, Review and Editing. A.Ł.: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft, Visualization. A.W.-P.: Investigation, Resources, Writing – Original Draft, Review and Editing. D.G.-C., M.H., K.M.-K., K.D., C.P., and E.P.: Investigation, Resources.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Marcinkowska, K., Synowiec, A., Łacka, A. et al. Temperature-dependent germination dynamics of herbicide-resistant and susceptible blackgrass (Alopecurus myosuroides) and silky windgrass (Apera spica-venti) from Poland. Sci Rep 16, 1267 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30986-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30986-3