Abstract

Accurate differentiation between actinic keratosis (AK) and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is crucial for effective treatment planning. While histopathology remains the gold standard, routine biopsy is often impractical for several reasons and dermoscopic evaluation is limited by overlapping features that lead to diagnostic uncertainty, even among experienced dermatologists. Artificial intelligence (AI), particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), has emerged as a powerful tool for automating image-based diagnosis in dermatology, achieving promising results in lesion classification. However, most of the existing models rely solely on raw images, overlooking the dermoscopic features that guide clinical reasoning. We developed a CNN-based model designed to classify AK versus cSCC in situ using dermoscopic images, integrating a dual-branch architecture that combines an EfficientNetB0 backbone for RGB inputs with a lightweight convolutional branch for two additional channels generated through targeted preprocessing to enhance vascular and keratinization patterns. Our dataset comprised 2,000 images, expanded through geometric and deep learning–based augmentation, exposing the model to nearly 200,000 training instances across epochs. Using repeated hold-out validation across 10 iterations, our best-performing model achieved an accuracy of 98.61%, sensitivity of 98.33%, specificity of 98.90%, precision of 98.90%, F1‑score of 98.61% and loss of 0.3120. These results surpass previously reported models for this task, demonstrating that incorporating clinically informed preprocessing significantly improves CNN performance. This approach represents a step toward clinically aligned AI systems capable of supporting dermatologists in differentiating between AK and cSCC with greater confidence and precision.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

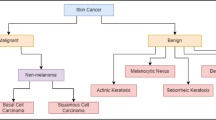

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is the second most common skin cancer in humans and represents a malignant neoplasm arising from epidermal keratinocytes1. Epidemiological studies report that cSCC has an annual incidence of around 700,000 cases in the United States and accounts for approximately 20% of non-melanoma skin cancers. Up to 60% of these tumors are thought to arise from pre-existing actinic keratoses (AKs), which are the most common premalignant skin lesions in dermatologic practice1,2,3. AKs (formerly known as solar keratoses and senile keratoses) are common cutaneous neoplasms resulting from the abnormal proliferation of atypical epidermal keratinocytes4. While most AKs remain stable or may regress spontaneously, the potential for malignant progression to cSCCs is increasingly recognized. Given this risk, accurate diagnosis is essential to distinguish AK from cSCC as the therapeutic approach varies significantly between the two. While AK can often be managed with topical treatments or cryotherapy, cSCC may require surgical excision or more aggressive interventions depending on its depth and differentiation5. Although histopathological examination remains the gold standard for confirming and differentiating these lesions, routine biopsy of every suspect area is neither practical nor desirable, particularly in patients with multiple lesions. In this context, even though new diagnostic imaging techniques such as dermoscopy are increasing the diagnostic accuracy as a key non-invasive diagnostic tool, capable of guiding clinical decision-making before biopsy6,7, the dermoscopic differentiation between AK and early cSCC remains challenging. Overlapping dermoscopic features often lead to diagnostic uncertainty and inconsistencies among clinicians. For instance, in a multicenter study, most dermatologists initially identified certain lesions as AK under dermoscopy; however, many of these cases also included differential diagnoses such as cSCC. If these cases are considered negative tests, the calculated sensitivity for dermoscopic AK diagnosis drops dramatically from approximately ~ 97% to 51.2%, underscoring the diagnostic uncertainty that persists even among experienced clinicians8. This limitation has fueled the exploration of artificial intelligence (AI)-based tools aimed at improving accuracy and standardization in the classification of such lesions.

AI has gained growing relevance in dermatology, especially in image-based diagnosis. Within AI, machine learning (ML) enables computers to learn patterns from data through mathematical procedures, while deep learning (DL) (a subtype of ML) uses multilayered neural networks to automatically extract and learn from hierarchical features9,10,11. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs), a type of DL algorithms, are especially suited for image analysis due to their ability to extract spatial features9. This architecture has demonstrated excellent performance across a variety of medical imaging tasks, and dermatology is no exception. For instance, Esteva et al. (2017) reported an AUC of approximately 0.96 for distinguishing keratinocyte carcinomas from benign seborrheic keratoses and malignant melanomas from benign nevi12,13. In the context of AK and cSCC, CNNs have also shown promising performance, successfully identifying these lesions in retrospective datasets with high sensitivity and specificity14. However, most current models are trained exclusively on raw dermoscopic or clinical images, without incorporating structured dermatologic knowledge or contextual clinical information. This image-only approach limits their generalizability and real-world applicability, particularly when confronted with lesion variability, comorbidities, or atypical presentations common in clinical practice. Moreover, while dermatologists rely on dermoscopic criteria to guide diagnosis, these features are rarely annotated or explicitly modeled in existing CNNs. Few studies have attempted to integrate patient metadata into the neural architecture, reporting improved performance15. Even fewer studies explore preprocessing techniques informed by dermoscopic features; most rely on basic data augmentation such as image rotation, flipping, or zooming, which may overlook critical visual cues16,17. This gap presents an opportunity: rather than developing yet another black-box model based solely on raw pixel data, our project proposes a dermatologically informed approach; incorporating structured dermoscopic features and using targeted data augmentation techniques to enrich the representation of clinically relevant visual patterns.

Given the clinical overlap and biological continuum between AK and cSCC, developing an AI model capable of distinguishing between them could significantly enhance early detection and decision-making in dermatology. Our study aims to develop a convolutional neural network trained specifically to classify AK versus cSCC lesions using dermoscopic images. Unlike previous studies that focus only on feeding raw images into CNNs, our approach introduces a structured preprocessing pipeline that highlights clinically relevant dermoscopic and histologic features. By integrating these features digitally before feeding them into the CNN, our model seeks not just to learn passively from data, but to mimic the reasoning process of dermatologists. This strategy aims to bridge the disconnect between algorithmic performance and diagnostic reasoning, making AI, more aligns with clinical dermatology, improving the model’s robustness and generalizability, especially in real-world settings with variable image quality. Ultimately, our model is designed not just to assist in classification, but to serve as a second-opinion tool that supports clinicians in distinguishing between AK and cSCC with greater confidence and precision.

Results and discussion

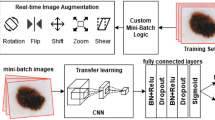

The experiments were conducted on a system with macOS Sequoia 15.0.1, equipped with an Apple M3 Pro processor (integrated CPU and GPU), 18 GB of unified RAM, and a 494 GB SSD. We used a dataset of 2,000 dermoscopic images of AK and cSCC, which was expanded through geometric and deep learning–based augmentation techniques to significantly increase the diversity of training inputs, exposing the model to approximately 200,000 training instances during optimization. We integrated preprocessing techniques to enhance vascular and keratinization features, generating additional channels to the input tensor that were input alongside the original RGB images into our multi-phase, dual-branch architecture. The model consisted of a pre-trained EfficientNetB0 backbone for the RGB channels and a lightweight convolutional branch for the extra channels, with features from both branches concatenated and classified via a dense head. Training was performed over three progressive phases, with the network optimized using the Adam optimizer (learning rate = 1e‑4 for initial phases and 1e‑5 for fine-tuning), categorical cross-entropy loss, Leaky ReLU activations, and early stopping with 10 epochs patience. Data was split 80% for training and 20% for testing. Model performance was evaluated by accuracy, sensitivity (also known as recall), specificity, precision, F1-score and loss, all calculated from the corresponding confusion matrices.

Performance through data enrichment

Table 1 shows the performance of the proposed CNN under different training configurations using an 80:20 train–test ratio applied through a random split (the actual counts may slightly vary due to shuffling and batching). Initially, we trained the model using only the original dataset, without any augmentation or preprocessing, to establish a baseline. The performance in this configuration was notably poor, indicating that the network struggled to generalize with the limited number of samples available. To address this limitation, we incorporated geometric and deep learning–based data augmentation techniques, which are later explained in the Methods section, significantly improving the model’s performance. Finally, we combined these augmentations with our proposed image preprocessing pipeline, enhancing vascular and keratinization features as additional input channels. Table 1 summarizes the results for these configurations. Notably, the largest performance gain (≈ 8% ± 0.5 across the evaluated metrics) was achieved with the introduction of data augmentation techniques. Subsequently, incorporating the two extra enhanced channels, further increased performance by ≈ 6%, leading to the highest overall results across all metrics.

Repeated hold out

Hold-out validation is a common approach in machine learning, where the available dataset is randomly divided into two subsets: one for training the model and the other for evaluating its performance. While simple and intuitive, the reliability of the results from a single hold-out split can be influenced by how the data is partitioned, potentially leading to biased estimates. To obtain a more robust evaluation, in this study we employed a variant known as repeated hold-out. Specifically, the dataset was randomly split into training and testing sets ten times, with the model trained and evaluated independently on each split. After each iteration, performance metrics for the final model evaluated with repeated hold-out were recorded and subsequently averaged, obtaining an accuracy of 98.61%, sensitivity of 98.33%, specificity of 98.90%, precision of 98.90% and F1-score of 98.61%. Compared to the single‑split hold‑out evaluation (see third row of Table 1), the repeated hold‑out approach (see fourth row of Table 1) yielded highly consistent performance across multiple splits, confirming the model’s robustness and mitigating potential bias from a single partition. No fixed train–test split was used at any stage; each of the ten iterations employed an independent random 80:20 partition.

Confusion matrix results

To measure the model’s performance, we generated confusion matrices for each experimental model configuration. For every approach, the confusion matrix summarizes the number of correct and incorrect predictions for each class, with the X-axis representing predicted labels and the Y-axis indicating true labels (Fig. 1). For each matrix, we also calculated the percentage of correctly classified samples per class, providing a detailed perspective on performance. The custom CNN model with data augmentation and preprocessing demonstrated the best performance above all the other experimental model configurations. Out of 800 samples, the model made 789 correct predictions, corresponding to an accuracy of 98.71% for AK and 98.53% for cSCC.

We also generated a confusion matrix for the custom CNN model with data augmentation and preprocessing using the repeated hold out approach (Fig. 2). This confusion matrix showed the result of 10 iterations achieving 7889 correct predictions, corresponding to an accuracy of 98.32% for AK and 98.89% for cSCC.

State-of-the-art models

Despite the clear clinical relevance of differentiating AK from cSCC, studies specifically addressing this binary computational differentiation remain limited, underscoring the need for targeted research. Most existing approaches focus on broader multi-class skin lesion classification, where AK and cSCC are included among several diagnostic categories rather than as a binary task. Although these studies were not designed exclusively for the AK versus cSCC task, their reported overall metrics provide a useful benchmark for situating our model’s performance within the broader landscape of dermoscopic image analysis, as summarized in Table 2. Earlier models, such as Giotis et al. (2015)18, combined color and texture descriptors with physician-provided visual attributes and achieved an accuracy of 81%. Almansour et al. (2016)19 employed preprocessing techniques for texture and color feature extraction and support vector machines (SVM), achieving an accuracy of 90.32%, sensitivity of 93.97%, and specificity of 85.84%. Esteva et al. (2017)12 applied Google’s Inception V3 CNN to a large dataset of 129,450 images and achieved an accuracy of 72.1%, despite the extensive dataset size. Dorj et al. (2018)20 applied AlexNet with transfer learning, demonstrating notable performance achieving an accuracy of 94.2%, sensitivity of 97.83% and specificity of 90.74%. Ameri et al. (2020)21 also utilized AlexNet with transfer learning and achieved lower performance with accuracy of 84%, sensitivity of 81%, and specificity of 88%. Molina-Molina et al. (2020)22 integrated fractal signatures and DenseNet-201 deep features, reaching higher metrics with an accuracy of 97.35% and specificity of 97.85%, but lower sensitivity 66.45% in comparison to previous models. Shetty et al. (2022)23 conducted a large‑scale evaluation of multiple deep learning architectures, where their proposed CNN achieved the best performance with an accuracy of 94.00% and sensitivity of 85.00%; however, despite the breadth of their analysis, none of the evaluated techniques demonstrated outstanding results. Although Tahir et al. (2023)24 achieved high performance (accuracy of 94.17% and sensitivity of 93.76%), their results still did not surpass the top-performing approaches reported in earlier studies. Alenezi et al. (2023)25 developed an innovative model combining wavelet transforms and CNNs, reporting excellent accuracy of up to 96.91% and specificity of up to 98.8%, outperforming previous CNN-based studies. Wang et al. (2024)26 presented a sophisticated integration of deep learning, radiomics, and patient metadata, achieving the highest reported accuracy (97.8%), sensitivity (97.6%), and specificity (98.4%) among the studies reviewed in this state‑of‑the‑art analysis. However, this approach relies on a complex multi‑modal pipeline that extends beyond image analysis alone, integrating additional patient‑level data. Most recently, Nawaz et al. (2025)17 combined a CNN model and fuzzy k-means clustering, achieving accuracies of 95%. Overall, our model demonstrates exceptional performance, surpassing the metrics reported by previous approaches and achieving 98.63% accuracy, 98.72% sensitivity, 98.54% specificity, 98.47% precision and a 98.59% F1-score only using data augmentation and preprocessing techniques.

These results underscore the novelty and robustness of our approach, as our CNN leverages clinically informed preprocessing channels that enhance dermoscopic features, mimicking how dermatologists interpret lesions, achieving state‑of‑the‑art performance with only augmented and preprocessed images, in contrast to more complex multimodal pipelines reported in previous studies.

Limitations and perspectives

Although the model achieved strong results, some factors should be kept in mind when interpreting its performance. The dataset was limited in size and included only images of actinic keratosis and cSCC in situ, which may affect its generalizability to larger and more diverse clinical populations, particularly when encountering other histological subtypes such as invasive cSCC. Moreover, the model was evaluated exclusively on retrospective dermoscopic images, and its performance in prospective, multicenter clinical settings remains to be determined. In addition, the dermoscopic images were obtained from a public repository without uniform standards for acquisition parameters, introducing variability in image quality. Despite posing certain challenges, such variability may also improve robustness to real-world conditions, though confirming this would require a larger and more diverse dataset.

Another important consideration is the possibility of ‘Clever Hans’ behavior, in which a model may rely on spurious background cues or acquisition artifacts rather than exclusively on lesion-specific dermoscopic features. Although the preprocessing pipeline aimed to emphasize clinically meaningful information, this cannot be fully ruled out. Future work should incorporate explainability methods such as Grad-CAM to visualize salient regions and verify that predictions are grounded in biologically relevant patterns.

From a practical standpoint, while training required considerable computational resources, implementation could be carried out with much lighter hardware. Future work should focus on adapting pre-trained models into lightweight applications capable of running on low-power devices such as smartphones or basic laptops. By leveraging pre-trained weights, these tools could deliver real-time dermoscopic analysis and support rapid decision-making in settings where access to dermatologists or specialized imaging equipment is limited. For successful clinical integration, the model should be paired with intuitive interfaces and workflows designed for dermatology practice, such as applications that enable clinicians to capture dermoscopic images directly from a mobile device, define a region of interest, and receive immediate classification results.

In clinical use, this type of system could be especially useful in situations where performing multiple biopsies is not practical, such as in patients with numerous lesions or when a lesion appears benign but the clinician seeks additional confirmation. While dermatopathological examination remains the gold standard for diagnosis, the model could serve as a reliable second-opinion tool to help prioritize which lesions to sample, supporting more efficient and targeted diagnostic decisions.

Methods

Dataset compilation

This study utilized dermoscopic images of AK and cSCC in situ derived from a curated Kaggle subset built entirely from primary source images of the International Skin Imaging Collaboration (ISIC) Archive, an open-access dermatologic imaging repository. All images were provided in JPEG format in the RGB color space with an original resolution of 600 × 450 pixels and were subsequently rescaled to 500 × 500 pixels prior to model training. The dataset comprised a total of 2,000 dermoscopic images, with 1,000 images per class (AK and cSCC). The ISIC Archive is a widely recognized and curated resource in the dermatology and computer vision communities, with contributions from multiple international dermatology centers. It has been extensively used in research and international benchmarking challenges (e.g., ISIC Skin Lesion Analysis Challenges), ensuring the reliability and scientific utility of the images included in this study.

Data augmentation

To improve model generalization and mitigate overfitting, we applied two complementary data augmentation strategies. First, we implemented geometric transformations, specifically horizontal flipping, which allowed us to double the size of the dataset to 4,000 images (2,000 per class) by generating mirrored versions of each image (Fig. 3). This technique preserves the intrinsic dermoscopic patterns while introducing spatial variability, a strategy shown to enhance robustness in image classification tasks23,27. Second, we employed a deep learning–based augmentation technique known as MixUp, which was implemented as part of our training pipeline to increase the diversity of samples seen by the model and reduce overfitting27,28. instead of only presenting the network with the original images, MixUp creates new “virtual” samples by combining two images and their labels. Specifically, two randomly selected samples \(\:({x}_{i},{y}_{i})\) and \(\:({x}_{j},{y}_{j})\) are linearly interpolated using a mixing factor \(\:\lambda\:\) sampled from a Beta distribution, resultin in \(\:\overline{x}=\lambda\:{x}_{i}+(1-\lambda\:){x}_{j}\) for the image and \(\:\overline{y}=\lambda\:{y}_{i}+(1-\lambda\:){y}_{j}\) for the label. This exposes the model to blended images and “soft” labels that represent a probabilistic combination of both classes, encouraging it to learn smoother and more generalizable decision boundaries. Rather than generating additional physical images on disk, MixUp produces interpolated samples on-the-fly during each training batch, meaning that the diversity of inputs grows dynamically with each epoch. For instance, in a dataset of 4,000 images with a batch size of 32, the model processes approximately 4,000 mixed-image pairs per epoch, exposing the network to nearly 200,000 interpolated Mix-up samples generated on-the-fly across 50 epochs, effectively expanding the training distribution even though no additional stored images were created.

Dermoscopy analysis

To integrate clinically relevant knowledge into our model, we conducted a targeted literature search to identify the dermoscopic hallmarks of AKs and cSCCs in situ (Table 3). Rather than relying exclusively on raw pixel data, we aimed to leverage high-quality images by integrating structured visual patterns commonly recognized in clinical dermoscopy. We defined a feature as “computationally tractable” if it presented a consistent, visually discernible pattern in dermoscopic images that could be enhanced through preprocessing, excluding findings without clear visual correlates. This approach ensured that the selected features were not only diagnostically meaningful but also compatible with image processing workflows, facilitating their integration into the neural network.

Among these, vascular architecture and keratinization patterns showed the strongest statistical significance in differentiating AK from cSCCs. These findings informed the design of our preprocessing pipeline, aimed at selectively enhancing these patterns to improve lesion differentiation.

Preprocessing for vascular architecture enhancement

To enhance vessel visibility, we focused on the green channel since vascular features exhibit higher contrast in this spectrum33,34. Using OpenCV, we extracted the green channel from the original RGB image and computed its inverted complement to increase the contrast of vascular structures relative to the surrounding tissue. We then applied Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) with a clip limit of 2.0 and an 8 × 8 tile grid, parameters that were iteratively optimized to enhance local contrast and improve vessel delineation. This combination of channel inversion and adaptive contrast enhancement selectively amplified vascular patterns while reducing background noise35 (Fig. 4). The resulting preprocessed image was integrated as an additional channel into the network’s input tensor, complementing the raw RGB data and providing the CNN with enriched information on vascular architecture.

Preprocessing for keratinization pattern enhancement

Keratinized regions, which appear as bright, scaly areas under dermoscopy, were enhanced using a morphological and luminance-based approach. Images were converted to the CIELAB (L*, a*, b*) color space, and the luminance (L*) channel was isolated to focus solely on brightness variations. allowed for more targeted processing of high-intensity keratinized regions, without interference from chromatic noise36. We then applied a morphological top‑hat transformation to the L* channel using a 25 × 25 elliptical structuring element. This operation subtracts a morphologically smoothed version of the image from the original, acting like a high‑pass filter that makes small, bright structures (such as keratin deposits) stand out while reducing background intensity37,38. To further refine these features, we implemented intensity clipping (0–255), normalization to the full dynamic range, and gamma correction (γ = 1.5), with all parameters iteratively adjusted to achieve optimal enhancement of bright keratinized regions while preserving background integrity. These sequential operations increased the visibility of keratin patterns without introducing artifacts (Fig. 5). The resulting luminance map was then incorporated as an additional input channel, providing the network with enhanced structural information specific to keratinization patterns.

Multi-phase model development and dual-branch integration

Through an iterative process aimed at maximizing performance while maintaining computational efficiency, we designed a multi-phase, dual-branch DL architecture39. Our approach began with a pretrained EfficientNetB0 backbone, initialized with ImageNet weights and used as a feature extractor with its convolutional layers frozen during the initial training phase to preserve pre‑learned representations and stabilize training before fine‑tuning40.

In the first phase, the base EfficientNetB0 model was trained solely on the original RGB images to establish strong initial representations. The extracted global feature vectors were passed through a fully connected dense layer of 256 neurons initialized with the He normal method, followed by Leaky ReLU activation (α = 0.1) and a dropout layer (rate = 0.5) to mitigate overfitting by reducing co‑adaptation of neurons, thereby enhancing generalization. A final Softmax output layer produced the two‑class probability distribution (AK vs. cSCC)39,41,42. The network was trained using the Adam optimizer (learning rate = 1e‑4) with categorical cross‑entropy loss, implemented through Keras43. Performance was evaluated using accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, precision, F1‑score, and loss as key metrics, all derived from confusion matrices incorporating true positives (TP), true negatives (TN), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN)9. The categorical cross‑entropy function quantified the divergence between predicted and true class distributions at each training step, guiding parameter updates through backpropagation to iteratively minimize errors and improve model performance.

In the second phase, we extended the architecture to integrate additional dermoscopic information. Two extra image channels were incorporated, resulting in a five-channel input tensor. These additional channels were generated through preprocessing techniques specifically designed to enhance vascular and keratinization patterns. To accommodate this, we constructed a dual-branch model: the first branch retained the original EfficientNetB0 as the feature extractor for the RGB channels (3-channel tensor), while the second branch consisted of a lightweight CNN dedicated to processing the two additional channels. Features from both branches were then concatenated and projected into a shared embedding space, passed through a dense classification head, again utilizing He normal initialization, Leaky ReLU activation, and dropout. During this phase, only the new convolutional branch and the final classification head were trained, while the EfficientNetB0 backbone remained frozen to retain previously learned visual features.

Finally, in the third phase, we selectively unfroze the last layers of the EfficientNetB0 backbone to allow joint optimization of both the base and extended branches, with a learning rate of 1e-5 to stabilize convergence. This progressive training regimen combined transfer learning, data augmentation, and dermoscopically informed preprocessing techniques to facilitate robust integration of both classic and augmented dermoscopic features, thereby maximizing the model’s performance while mitigating risks of overfitting.

Conclusions

The proposed model presents an efficient CNN-based approach for distinguishing actinic keratosis from cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in situ using dermoscopic images. Conventional dermoscopic diagnosis can be limited by overlapping visual features and interobserver variability, even among experienced clinicians. Our model integrates clinically informed preprocessing techniques, specifically enhancing vascular and keratinization patterns into a dual-branch architecture, enabling the network to mimic key aspects of dermatological reasoning. Performance improved markedly through the progressive incorporation of data augmentation and targeted preprocessing, achieving an accuracy of 98.61%, sensitivity of 98.33%, specificity of 98.90%, precision of 98.90% and F1-score of 98.61%. While histopathological examination remains the gold standard for diagnosis, this approach offers a reliable second opinion tool to support lesion prioritization for biopsy, especially in scenarios where extensive sampling is impractical. Future work will focus on expanding the dataset to include other histological subtypes such as invasive cSCC, standardizing image acquisition, and validating the model prospectively across multiple centers. We aim to integrate the pre-trained model into lightweight, user-friendly applications capable of real-time analysis on low-power devices, facilitating adoption in both specialized dermatology clinics and resource-limited settings.

Data availability

The dermoscopic images analyzed in this study originate from the International Skin Imaging Collaboration (ISIC) Archive (https://www.isic-archive.com/) and were accessed through a curated Kaggle subset built entirely from primary ISIC source images (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/ayaanmustafa/augmented-skincancer-isic).

References

Que, S. K. T., Zwald, F. O. & Schmults, C. D. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 78, 237–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.059 (2018).

Review of Dermatology (Elsevier, 2024).

Thompson, A. K., Kelley, B. F., Prokop, L. J., Murad, M. H. & Baum, C. L. Risk factors for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma recurrence, metastasis, and disease-specific death: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 152, 419–428. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.4994 (2016).

Li, Y., Wang, J., Xiao, W., Liu, J. & Zha, X. Risk factors for actinic keratoses: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Indian J. Dermatol. 67, 92. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijd.ijd_859_21 (2022).

Li, Z. et al. From actinic keratosis to cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: the key pathogenesis and treatments. Front. Immunol. 16, 1518633. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1518633 (2025).

Casari, A., Chester, J. & Pellacani, G. Actinic keratosis and Non-Invasive diagnostic techniques: an update. Biomedicines 6, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines6010008 (2018).

Combalia, A. & Carrera, C. Squamous cell carcinoma: an update on diagnosis and treatment. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 10, e2020066. https://doi.org/10.5826/dpc.1003a66 (2020).

Valdés-Morales, K. L., Peralta-Pedrero, M. L., Jurado-Santa Cruz, F. & Morales-Sanchez, M. A. Diagnostic accuracy of dermoscopy of actinic keratosis: A systematic review. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. e20200121. https://doi.org/10.5826/dpc.1004a121 (2020).

Ramos-Briceño, D. A., Flammia-D’Aleo, A., Fernández-López, G., Carrión-Nessi, F. S. & Forero-Peña, D. A. Deep learning-based malaria parasite detection: convolutional neural networks model for accurate species identification of plasmodium falciparum and plasmodium Vivax. Sci. Rep. 15, 3746. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87979-5 (2025).

Sidey-Gibbons, J. A. M. & Sidey-Gibbons, C. J. Machine learning in medicine: a practical introduction. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 19, 64. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0681-4 (2019).

Obermeyer, Z. & Emanuel, E. J. Predicting the Future - Big Data, machine Learning, and clinical medicine. N Engl. J. Med. 375, 1216–1219. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1606181 (2016).

Esteva, A. et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature 542, 115–118. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21056 (2017).

Puri, P. et al. Deep learning for dermatologists: part II. Current applications. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 87, 1352–1360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.053 (2022).

Primiero, C. A. et al. A protocol for annotation of total body photography for machine learning to analyze skin phenotype and lesion classification. Front. Med. 11, 1380984. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1380984 (2024).

Höhn, J. et al. Integrating patient data into skin cancer classification using convolutional neural networks: systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e20708. https://doi.org/10.2196/20708 (2021).

López-Labraca, J., González-Díaz, I., Díaz-de-María, F. & Fueyo-Casado, A. An interpretable CNN-based CAD system for skin lesion diagnosis. Artif. Intell. Med. 132, 102370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artmed.2022.102370 (2022).

Nawaz, K. et al. Skin cancer detection using dermoscopic images with convolutional neural network. Sci. Rep. 15, 7252. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91446-6 (2025).

Giotis, I. et al. MED-NODE: A computer-assisted melanoma diagnosis system using non-dermoscopic images. Expert Syst. Appl. 42, 6578–6585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2015.04.034 (2015).

Almansour, E. & Jaffar, M. A. Classification of dermoscopic skin cancer images using color and hybrid texture features. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Netw. Secur. 16, 135–139 (2016).

Dorj, U. O., Lee, K. K., Choi, J. Y. & Lee, M. The skin cancer classification using deep convolutional neural network. Multimed Tools Appl. 77, 9909–9924. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-018-5714-1 (2018).

Ameri, A. A. Deep learning approach to skin cancer detection in dermoscopy images. J. Biomed. Phys. Eng. 10, 801–806. https://doi.org/10.31661/jbpe.v0i0.2004-1107 (2020).

Molina-Molina, E. O., Solorza-Calderón, S. & Álvarez-Borrego, J. Classification of dermoscopy skin lesion Color-Images using Fractal-Deep learning features. Appl. Sci. 10, 5954. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10175954 (2020).

Shetty, B. et al. Skin lesion classification of dermoscopic images using machine learning and convolutional neural network. Sci. Rep. 12, 18134. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-22644-9 (2022).

Tahir, M. et al. DSCC_Net: Multi-Classification deep learning models for diagnosing of skin cancer using dermoscopic images. Cancers 15, 2179. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15072179 (2023).

Alenezi, F., Armghan, A. & Polat, K. Wavelet transform based deep residual neural network and ReLU based extreme learning machine for skin lesion classification. Expert Syst. Appl. 213, 119064. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2022.119064 (2023).

Wang, Z. et al. Radiomic and deep learning analysis of dermoscopic images for skin lesion pattern decoding. Sci. Rep. 14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70231-x (2024).

Shorten, C. & Khoshgoftaar, T. M. A survey on image data augmentation for deep learning. J. Big Data 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-019-0197-0 (2019).

Zhang, H., Cisse, M. & Dauphin, Y. N. & Lopez-Paz, D. mixup: beyond empirical risk minimization. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.1710.09412 (2017).

Bolognia, J. L. Dermatology—E-Book: 2-Volume Set (Elsevier, 2024).

Álvarez-Salafranca, M. & Zaballos, P. [Translated article] dermoscopy of squamous cell carcinoma: from actinic keratosis to invasive forms. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 115, T883–T895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2024.03.037 (2024).

El-Ammari, S. et al. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: Clinico-Dermoscopic and histological correlation: about 72 cases. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. e2024042. https://doi.org/10.5826/dpc.1401a42 (2024).

Zalaudek, I. et al. Dermoscopy of facial nonpigmented actinic keratosis: dermoscopy of facial nonpigmented AK. Br. J. Dermatol. 155, 951–956. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07426.x (2006).

Jalili, J., Hejazi, M., Elyasi, A., Ebrahimi, S. M. & Esfahani, M. Automatic multi resolution-based vascular tree extraction in fundus photography (2019).

Jakovels, D., Kuzmina, I., Berzina, A., Valeine, L. & Spigulis, J. Noncontact monitoring of vascular lesion phototherapy efficiency by RGB multispectral imaging. J. Biomed. Opt. 18, 126019. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.jbo.18.12.126019 (2013).

Halloum, K. & Ez-Zahraouy, H. Enhancing medical image classification through transfer learning and CLAHE optimization. Curr. Med. Imaging Rev. 21. https://doi.org/10.2174/0115734056342623241119061744 (2025).

Hanlon, K. L., Wei, G., Correa-Selm, L. & Grichnik, J. M. Dermoscopy and skin imaging light sources: a comparison and review of spectral power distribution and color consistency. J. Biomed. Opt. 27, 080902. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JBO.27.8.080902 (2022).

Hassanpour, H., Samadiani, N. & Mahdi Salehi, S. M. Using morphological transforms to enhance the contrast of medical images. Egypt. J. Radiol. Nucl. Med. 46, 481–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrnm.2015.01.004 (2015).

Moradzadeh, S. & Mehrdad, V. Improvement of medical images with multi-objective genetic algorithm and adaptive morphological transformations. Sci. Rep. 15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10245-1 (2025).

Lian, W., Lindblad, J., Micke, P. & Sladoje, N. Isolated channel vision transformers: from single-channel pretraining to multi-channel finetuning. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2503.09826 (2025).

Tan, M. & Le, Q. V. EfficientNet: rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.1905.11946 (2019).

Srivastava, N. et al. A simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 15, 1929–1958 (2024).

Kulathunga, N. et al. Effects of the nonlinearity in activation functions on the performance of deep learning models. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2010.07359 (2020).

Abadi, M. et al. TensorFlow: A system for large-scale machine learning. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.1605.08695 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Margarita Oliver, dermatologist and dermatopathologist at the Jose María Vargas School of Medicine, for her kind feedback during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DARB conceived the original idea, designed the methodology, and performed the data analysis. He also carried out the validation of results and managed the overall project administration. JPC and AL provided supervision and guidance throughout the study. DARB drafted the initial manuscript, which was subsequently developed and refined by DARB, JPC, and AL. DARB, JPC, AL and MGW, contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ramos-Briceño, D.A., Pinto-Cuberos, J., Linfante, A. et al. Dermoscopically informed deep learning model for classification of actinic keratosis and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Sci Rep 16, 1381 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31259-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31259-9