Abstract

Antimicrobial resistance poses global environmental and public health challenges, with hospital wastewater serving as a critical reservoir of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB). This study evaluated the diversity and abundance of ARGs, mobile genetic elements (MGEs), and microbial communities in wastewaters of 13 hospitals across Lebanon. 16 S rRNA gene sequencing showed the microbial compositions of wastewaters to be widely variable. Procrustes analysis revealed that these differences influenced wastewater ARG/MGE profiles. High throughput qPCR showed that genes associated with integrons, transposons, plasmids, and insertion sequences were highly prevalent, with 14 genes detected at ≥ 0.01 copies per 16 S rRNA gene copy. Genes conferring resistance to β-lactams, aminoglycosides, tetracyclines, and sulfonamides were the most abundant. Network analysis identified significant co-occurrence patterns among microbial communities, MGEs, and ARGs, highlighting the potential for horizontal gene transfer (HGT) facilitated by specific transposons and integrons associated with particular microbial hosts. Several physicochemical parameters of the wastewaters also showed strong correlations with ARGs, MGEs, and microbes, suggesting that water quality may influence resistance dissemination. These findings underscore the critical need for monitoring of factors influencing ARG dynamics in hospital systems to limit the spread of antimicrobial resistance from clinical settings into the environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has been described as a silent pandemic, emerging as one of the most critical public health challenges of the 21st century, causing millions of deaths annually and posing a significant economic threat1,2,3,4.

Studies have shown that the discharge of wastewater containing antibiotic residues, antibiotic resistant bacteria (ARB), antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), and mobile genetic elements (MGEs) is a significant contributor to the spread of AMR5,6. In particular, effluents originating from hospitals consist of a complex mixture of hazardous contaminants. Such contaminants include pharmaceutically active compounds, hormones, heavy metals, disinfectants, radioisotopes, X-ray contrast media, and pathogenic microbes, along with antibiotic residues and associated resistance genes7,8,9. Antibiotics administered to patients, once excreted, subsequently enter the hospital wastewater effluents, resulting in a heightened risk of transmitting antimicrobial resistance from the microbiota of hospitalized patients in clinical settings to downstream environments10,11.

Although recently developed and approved drugs have shown promise for the treatment of life-threatening infections caused by multidrug resistant (MDR) microorganisms, emerging resistance to these novel molecules has recently been reported12. This is in part due to the misuse of antibiotics, which has compromised their effectiveness, ultimately exacerbating the spread of drug-resistant infections5,13. Bacteria can acquire antibiotic resistance through two primary mechanisms: (1) spontaneous mutations of chromosomal genes (resulting in the production of ARGs) and (2) acquisition of ARGs from other strains of the same or different species via horizontal gene transfer (HGT). The latter has been shown to significantly contribute to the rapid spread of resistance. Exchange of genetic information between two organisms through HGT primarily involves conjugation via plasmids, transduction mediated by bacteriophages, and natural transformation facilitated by extracellular DNA released by dead ARB14,15. An acquired resistome through HGT involves MGEs such as plasmids, transposons, and integrons, which are responsible for transferring resistance16.

The spread of ARGs is strongly influenced by a range of socio-economic factors, including limited access to quality healthcare, inadequate wastewater treatment, weak regulatory governance, and overcrowded living conditions17,18. These challenges are particularly pronounced in developing countries such as Lebanon. Lebanon presents an interesting case in assessing ARG dissemination due to its unique demographic pressures as it hosts the highest number of refugees per capita and per square kilometer globally. Additionally, its large expatriate population with frequent returns for visits, far exceeds the number of residing citizens, leading to periodic surges in population density19,20. These dynamics have placed significant strain on the country’s already fragile healthcare and economic infrastructure21, potentially accelerating the spread of ARGs.

A recent review article discussing the status of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) in Lebanon highlighted the emergence of CRE pathogens in hospital isolates. These primarily included Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, with numerous reported cases over the years attributed to several factors, including the Syrian refugee crisis, water contamination, and antimicrobial misuse22. With respect to hospital wastewater specifically, other work has detected occurrence of NDM-1-producing Enterobacter cloacae, in addition to extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing isolates of E. coli and Klebsiella spp.23. Still, no studies to date have investigated the antibiotic resistome, mobilome, or microbiome of Lebanese hospital wastewaters using molecular methods on untreated effluent samples.

Globally, a wide range of work has investigated the occurrence of ARGs in hospital wastewater environments. Such studies have commonly utilized both quantitative methods (e.g., qPCR) and high-throughput methods (e.g., shotgun metagenomics)24,25,26. Published research using qPCR, in particular, has been valuable for determining potential co-occurrences of ARGs with MGEs and/or establishing correlations between ARGs and bacterial groups11,27,28. Other work has utilized qPCR to assess the impacts that on-site hospital wastewater treatment can have on ARG and bacterial removal rates29,30. Still, most studies that have employed microbial analysis in combination with qPCR for ARG detection have focused on a small number of hospital sampling sites (i.e., n ≤ 3), with only one such study assessing 10 or more hospitals’ wastewaters31. Such larger-scale campaigns are, however, valuable for gaining a more universal perspective on the state of antibiotic resistance spread within a region/country.

The present study is the first to comprehensively characterize the resistome (ARGs), mobilome (MGEs), and microbial community structure in hospital wastewaters across Lebanon, and to integrate this data with wastewater physicochemical properties. This combined approach provides novel insights into the co-occurrence patterns among ARGs, MGEs, and microbial communities, while also identifying potentially influencing wastewater effluent attributes.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and processing

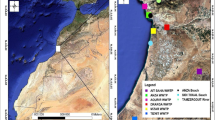

A total of 13 wastewater samples were collected from Lebanese hospitals in sterilized amber glass 1-L bottles (PP28, LBG, Labbox, Spain), and designated sample IDs as HWW1 through HWW13. Information regarding the sampled hospitals (including region, capacity, etc.) is provided in Table S1 of the supplementary information (SI). After collection, the samples were transported to the laboratory under aseptic conditions in refrigerated containers and processed within 12 h. The bottles were mixed to ensure sample homogeneity prior to any analysis or filtration-based concentration. A vacuum microfiltration system was used to filter 100 mL of each wastewater sample through a 0.22 μm mixed cellulose ester (MCE) membrane filter (Microlab Scientific) to be used for subsequent DNA extraction.

Total genomic DNA was extracted from the membrane filters using the DNeasy PowerWater Kit (QIAGEN, Germany) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA was eluted in 100 µL of TE buffer solution (Tris-EDTA, 1X Solution, pH 7.4, Sigma-Aldrich) and passed through the spin filter twice to maximize yield. Purity and quality of the extracted DNA were confirmed by measuring the A260:A280 ratio using a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). DNA samples were then stored at -20 °C until further analysis.

Methods for physicochemical characterization

The collected wastewater samples were initially tested and analyzed for several water quality parameters. pH was measured using a bench pH meter (WPA CD 500, UK), and electrical conductivity was measured using a conductivity meter (Sartorius-PT-20, USA). Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) was tested following the USEPA digestion method and measured using method 8000 of a Hach DR3900 spectrophotometer (HACH, USA). Total phosphorus (TP), total nitrogen (TN), total Kjeldahl nitrogen (TKN), ammonia-nitrogen (NH3-N), and sulfate were measured using the DR 3900 spectrophotometer according to methods 8190, 10,072, 10,242, 10,031, and 10,227, respectively.

Total organic carbon (TOC) was calculated as the difference between total carbon (TC) and inorganic carbon (IC) measured with the TOC-L/SSM5000A analyzer (Shimadzu, Japan). For TOC analysis, 1 mL of homogenous samples was weighed in a ceramic boat, covered with ceramic fiber, then transferred into the Solid Sample Module (SSM-5000 A) at an oxidizing furnace temperature of 900 °C for determination of TC content. The IC content was transformed to CO2 at a temperature of 200 °C using concentrated phosphoric acid. The SSM was equipped with purified oxygen at 200 kPa and the carrier gas flow was set at 0.5 L/min.

Microbial community characterization

DNA extracted from all samples was sent to Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) for 16 S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing using the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 sequencing platform. PCR amplification of the V3-V4 region of the 16 S rRNA gene was performed using the primer set 341 F (5ʹ-CCTAYGGGRBGCASCAG-3ʹ) and 806R (5ʹ-GGACTACNNGGGTATCTAAT-3ʹ), resulting in a 470 bp fragment, followed by library preparation to generate 250 bp paired-end raw reads.

The Galaxy Mothur Toolset was employed for bioinformatics data processing and analysis, with the Silva 132 reference database used for alignment and the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) 16 S rRNA training set No. 19 utilized for classification32. The VSEARCH algorithm was applied to filter chimeric sequences. Sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs). Alpha diversity parameters were calculated using Mothur. The dataset was subsampled to an even depth across the samples, using the lowest number of sequence reads detected. The representative sequences obtained were compared with all 16 S rRNA sequences available from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) using the nucleotide Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST). A similarity of ≥ 97% was considered the threshold for identification at the species level.

ARG and MGE assessment by high-throughput quantitative PCR (HT-qPCR)

To assess abundances of ARGs and MGEs, DNA samples were sent for high-throughput quantification at the Resistomap Oy Laboratory (Helsinki, Finland) using the SmartChip™ Real-Time PCR system (Takara Bio, CA, USA). A total of 96 validated primer sets targeting major classes of ARGs and MGEs were employed. These included 79 resistance genes that confer resistance to sulfonamides (2), quinolones (2), aminoglycosides (12), phenicol (8), macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B (MLSB) (8), multidrug resistance (MDR) (9), tetracyclines (9), β-lactams (18), vancomycin (2), trimethoprim (3), colistin, and others. Additionally, 16 primer sets targeted genes representing MGEs including integrons, plasmids, transposons, and insertion sequences. The 16 S rRNA gene was also quantified as a basis for determining normalized gene abundances. The primer sequences selected for this study were based on those previously developed33. Detailed information regarding primer sets used is provided in Tables S2 and S3 of the SI.

Amplification for each primer set was conducted in triplicate using the conditions described by Wang et al. (2014)34. This involved an initial enzyme activation step at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 ℃ for 30 s and annealing at 60 ℃ for 30 s. To ensure reaction specificity and prevent false positives, particularly for low-abundance genes, no-template control (NTC) was included to monitor potential contamination. Additionally, melting curve analysis and PCR efficiency assessment were performed on all the samples for each primer set. Amplicons with non-specific melting curves and multiple peaks, as indicated by the slope of melting profile, were considered false positives. Reactions with amplification efficiency outside the range of 1.8 to 2.2 were excluded from further analysis. To ensure reproducible detection, a threshold cycle (Ct) of 27 was used as the detection limit, and only amplifications observed in all replicates were considered positive35. The mean Ct of three technical replicates for each qPCR reaction was used to calculate the ΔCt values. Genes quantified in only one of the three technical replicates were excluded from the analysis. These quality-control measures collectively ensured reliable detection and high reproducibility of qPCR. The 2−ΔCt method was used to calculate abundances of detected genes relative to the 16 S rRNA gene in each sample. The results are expressed as gene copies per 16 S rRNA gene36.

Statistical analysis and data visualization

Heatmaps were generated using the “ComplexHeatmap” (v2.21.1) package in RStudio (version 2024.09.0-375). Spearman correlations between microbes and genetic elements were calculated using the “Hmisc” package (v5.1-3) in RStudio. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients (ρ) were also calculated to determine correlations between measured water quality parameters and different bacterial groups, ARGs, and MGEs. Values of individual variables were ranked, and the Spearman coefficient was calculated using the Correlation function in Microsoft Excel. It should be noted that Spearman’s correlation provides insight into potential associations rather than direct functional relationships.

The association between the hospital wastewater microbiome and the resistome-mobilome was examined using Procrustes analysis performed on Bray-Curtis distance matrices created from both the microbial matrix and the normalized abundance matrix of ARG-MGEs. Principal coordinates analyses (PCoA) of both matrices were conducted and utilized for the Procrustes analysis. The first two PCoA axes of each matrix were used to calculate the symmetric Procrustes correlation coefficients, the measure of fit (sum of squared distances), the p-value, and the Procrustes residuals. The Procrustes correlations were visualized using “ggplot2” (v3.5.1). Microbiome and resistome clustering were also performed on PCoA coordinates using the k-means function from the “stats” package (v4.4.2). The optimal number of clusters was determined using the elbow method. A Permutational Analysis of Variance (PERMANOVA) was conducted using the adonis2 function with 999 permutations to assess the significance of both clusters and geographic regions. PERMANOVA and Procrustes analysis were conducted using the “vegan” package (v2.6-10) in RStudio. Network analysis was performed to investigate the co-occurrence patterns of genetic elements (ARGs and MGEs) and microbes. The correlation network was visualized using the interactive platform Gephi (0.10.1)37 under the Fruchterman-Reingold layout algorithm38.

Results and discussion

Water quality-associated parameters

The physicochemical characterization of the hospital wastewater samples is presented in Table 1. Sample HWW7 had the highest values for multiple parameters (TP 97.6 mg/L, TN 224 mg/L, COD 1137 mg/L, NH3-N 175.6 mg/L, and TOC 614.3 mg/L). Organic matter content in terms of COD varied widely across samples (between 14 and 1137 mg/L), with the Bekaa region having the highest average values at 437 ± 188 mg COD/L. These findings fall within a range of values similar to those previously reported for hospital wastewaters39,40. Sample conductivity ranged between 2.1 and 1928 µS/cm, representing the largest variability among all parameters. Overall, differences in physicochemical parameters between samples did not appear to be definitively affected by a hospital’s region or size.

Spearman coefficients calculated between parameters showed that TP, TN, TKN, sulfate, and NH3-N were all positively and significantly correlated for all 13 samples (Table S4). This was exemplified by the simultaneously highest and lowest measured parameters in HWW7 and HWW13, respectively. COD was also correlated with TN, NH3-N, and TOC. These observations confirm that hospital wastewater nutrient components such as TP, TN, TKN, and NH3-N exhibit more closely associated fluctuation patterns compared to sulfate or TOC. Ammonium and phosphorus concentrations in hospital wastewaters have been shown to have the most direct role in shaping their associated microbial communities41.

Microbial community profiles

Bacillota, Pseudomonadota, Bacteroidota, Campylobacterota, and Actinomycetota were the most dominant phyla in the hospital wastewater samples; this is reflective of previous findings42,43. A total of 90 microbial groups with relative abundances of over 1% in at least one sample were identified at the genus or species level. Common gut-associated microbes and potentially pathogenic genera, including Arcobacter, Enterococcus, Acinetobacter, Escherichia, and Aeromonas, were dominant in most samples (Figure S1).

Nonetheless, each of the hospital wastewaters assessed in this study exhibited a relatively distinct microbial composition, with notable differences in dominant groups and their relative abundance levels (Fig. 1). Arcobacter aquimarinus and Acinetobacter johnsonii were only dominant in HWW1 (respective relative abundances of 16.7% and 9.7%). Likewise, Megamonas funiformis was only predominant in HWW2 (58.7%) and Aeromonas veronii in HWW10 (25.2%). Aliarcobacter cryaerophilus was also highly abundant in both HWW1 and HWW10 (21.7% and 22.3%, respectively). Segatella copri and Leyella stercorea were most abundant in HWW7, HWW11, and HWW13, all of which are located in the North region. Particularly, Leyella stercorea was nearly three times higher in HWW7 and coincided with the highest recorded values of several physicochemical parameters (Table 1). Also, Parabacteroides chartae, unclassified Azonexaceae, and unclassified Rhodocyclales were exclusively significantly detected in HWW8 (8.6%, 11.9% and 11.7%, respectively). This is indicative of HWW8’s especially unique microbial profile. Incidentally, this was the only governmental hospital (Table S1), suggesting that patient type and medical treatment administered play an important role in shaping the microbial communities of discharged wastewater.

Alpha diversity indices were calculated to assess community richness and diversity (Table S6). This analysis showed the highest overall diversity (Shannon Index, H’) in samples HWW6 (Beirut, H’ = 4.95) and HWW9 (Mount Lebanon, H’ = 4.81), followed by similar values in the Bekaa and North region samples (average H’ of 3.65 ± 0.65 and 3.64 ± 0.47, respectively). HWW6, the only hospital located in the capital (Beirut), had a significantly higher richness value (2395) as compared to other samples. Richness was shown to significantly correlate with certain microbial groups, such as Arcobacter aquimarinus (ρ = -0.596, Table S5), indicating that other opportunistic pathogens may also be influenced in such samples. These trends suggest a certain level of geographic influence on microbial community structure; with urban hospitals (Beirut and Mount Lebanon) likely treating a more heterogeneous patient population compared to the North region, other selective pressures in the North may have had a greater influence (Table S1).

Assessment of ARGs and MGEs

Among the 95 targeted genes (excluding the 16 S rRNA gene), the total number detected per hospital wastewater sample ranged from 86 to 89 (shown in Table S7). The primary mechanisms of antibiotic resistance were antibiotic deactivation and cellular protection (mechanisms shown in Table S2). In contrast, ARGs associated with efflux pumps contributed the least to resistance in the hospital wastewaters. 62 of the analyzed genes (48 ARGs and 14 MGEs) were detected at a normalized abundance greater than 0.01 gene copies per 16 S rRNA gene copy in at least one sample (Fig. 2). Numerical values of normalized abundance of genes in all wastewater samples are provided in Supplementary Material 1.

Heatmap of normalized abundances of ARGs and MGEs (log-scale) detected using high-throughput qPCR in all samples. Genes are categorized by class, and only those with a normalized abundance of ≥ 0.01 in at least one sample are displayed. The abundances of all detected ARGs and MGEs are available in the (Supplementary Material 1).

Absolute abundances of both ARGs and MGEs were highest in HWW10, with a total of 7.44 × 1010 copies/100 mL, and lowest in HWW13 (Supplementary Material 2, Figure S2A). Calculated Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients indicated that classes including phenicol, quinolone, tetracycline, and trimethoprim were significantly positively correlated with each of TP, TN, TKN, and NH3-N (Table S5). Similarly, HWW7, having the highest measured concentrations of several physicochemical parameters, also had the highest overall abundance of tetracycline-associated ARGs (Figure S2B). These observations align with previous research work that also indicated that the phosphorus and nitrogen compounds in raw hospital wastewater have played an important role in shaping the ARG profiles41.

The heatmap showing normalized ARG abundances per 16 S rRNA gene (Fig. 2) revealed that the ARGs detected at the highest concentrations in the hospital wastewaters confer resistance to a majority of clinically important antibiotic classes, including the MLSB, β-lactams, aminoglycosides, tetracyclines, and sulfonamides, among others44. Such antibiotics are known to be extensively administered to hospitalized patients, which inevitably contributes to heightened levels of their associated resistance genes44,45,46. Conversely, ARGs associated with phenicol and trimethoprim had the lowest normalized abundance among all samples.

Figure 2 shows that genes encoding for integrons, along with the plasmid replication initiation protein repA, were consistently prevalent as MGEs in all samples (normalized abundance values ranging from 0.07 to 1). Interestingly, these gene types were also positively correlated with each of TN and TKN (Table S5). A high abundance of the repA gene indicates an increased likelihood of resistance transfer through plasmids. Class 1 and class 3 integrons (intI1 and intI3) have been frequently and extensively reported in wastewaters36,47,48 and are recognized as universal biomarkers for anthropogenic pollution49. Both of these integrons often carry multiple resistance genes and are commonly mobile on plasmids and transposons; this ultimately compounds the threat of their associated ARGs50. Exemplifying this, several samples displayed a high normalized abundance of the quaternary ammonium compound resistance gene protein (qacEdelta1), reaching up to 0.31 copies per 16 S rRNA. This gene is commonly embedded in class 1 integrons51, which likely explains its co-occurrence with intI1 in samples HWW5, HWW8, and HWW10.

The normalized abundance of intI2 was consistently low across all samples, ranging from 4.92 × 10− 5 to 5.54 × 10− 3 (Supplementary Material 1). Similar results were also recently reported by others52. The integron integrase encoded for by intI2 is inactive, resulting in a non-functional protein53,54.

The transposase-coding gene tnpA_1, commonly associated with the insertion sequence IS26 that plays an important role in the dissemination of resistance in Gram-negative bacteria55,56, exhibited especially high normalized abundances in many instances (reaching up to 0.36). Other MGEs, including the insertion sequences IS6100 and IS613, as well as other transposase-coding genes, were also prevalent among samples (values ranging from 0.02 to 0.31). Coincidentally, tnpA_1, tnpA_3, tnpA_6, and tnpA_7 transposase-coding genes were all positively correlated with the total phosphorus measured in the wastewater samples.

Sulfonamide resistance genes sul1 and sul2 were found to be highly prevalent across all samples (respective average normalized abundances of 0.46 and 0.23). Notably, the Guiana extended-spectrum β-lactamase gene (blaGES) was found in high abundance in five of the thirteen hospitals (0.16–0.74 copies per 16 S rRNA), four of which fall in the North region. Additional high-prevalence ARGs identified in the majority of wastewater samples included β-lactams (blaOXA10, cfxA, and blaTEM), tetracyclines (tet(O), tet(G), tet(Q), and tet(X)), aminoglycosides (aac(3)-iid_iia, aac6-aph2, spcN, aacA/aphD, aadA1, strB, and aph(3’’)-ia), MLSB (ermF, mphA, ereA, and ermB), multidrug (copA), vancomycin (vanA), and bacitracin resistance (bacA).

In the context of Lebanon, recent work has also reported high abundances of transposase genes in co-occurrence with a diverse range of ARGs in estuaries and rivers across the country57. It remains to be seen, though, whether certain combinations/ratios of physicochemical markers (such as TP, TN, and NH3-N) might in the future be utilizable as indicators of elevated waterborne risk associated with antibiotic resistance and its mobility.

Analysis of clinically relevant ARGs

According to the WHO AWaRe (Access, Watch and Reserve) classification58, the Reserve group of antibiotics include those that are designated as a last-resort option for treating infections caused by MDR organisms. From the genes targeted in this study, genes conferring resistance to Reserve group antibiotics were identified using the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD)59. Specific examples are mcr1 and mcr2 (colistin resistance), tet(X) (tigecycline resistance), and tet(M), tet(36), tet(W), tet(Q), tet(S), and tet(O) (minocycline resistance). The absolute copy numbers of these ARGs varied significantly across samples (Supplementary Material 2), with the highest levels observed in HWW1 (Bekaa), HWW7, HWW10, and HWW11 (the latter three located in the North region), potentially indicating the presence of localized resistance reservoirs.

Absolute abundances of the mcr1 gene ranged from 4.81 × 105 to 6.4 × 107 copies/100 mL; in contrast, mcr2 was only sporadically detected in three of the samples (ranging from 4.09 × 104 to 3.22 × 105 copies/100 mL). The mcr1 gene was first reported in Lebanon in an E. coli strain isolated from human clinical samples in 201960. One year later, another variant, mcr-8.1, was identified in a K. pneumoniae isolate obtained from a urine sample in Lebanon61. In general, elevated levels of these ARGs in specific hospital wastewaters underscores the potential for heightened risk of dissemination to the environment under specific circumstances and/or in specific regions.

The semi-synthetic lipoglycopeptide antibiotics dalbavancin and telavancin, both classified as Reserve group antibiotics, are considered ineffective against vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) that carry the vanA gene62. vanA was detected at high concentrations in certain samples, reaching 6.03 × 108 copies/100 mL in HWW10, and was also found to be correlated with both TN (\(\:\rho\:\)=0.61) and TKN (\(\:\rho\:\)=0.621). A nationwide surveillance study conducted across 16 tertiary care centers in Lebanon from 2011 to 2013 reported a prevalence of 1% for VRE based on antimicrobial susceptibility profiles63. However, the incidence of VRE infections increased to 5.9% in 201864, and it still appears to be frequently detected in Lebanese hospitals currently65. The release of vanA from hospitals through their wastewaters raises specific concerns, especially given that vancomycin is the last-resort antibiotic for treating infections caused by Gram-positive bacteria such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus66.

Other concerns associated with proliferation of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) are often attributable to the genes responsible for production of carbapenemase. Different \(\:{\upbeta\:}\)-lactamase classes (A, B, C, and D) are known to produce different carbapenemases (e.g. Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase – KPC, metallo-β-lactamases – MBLs, New-Delhi-metallo-β-lactamases – NDM, and oxacillinase (OXA)-48-like β-lactamases)67,68. Among these, blaKPC, blaNDM, and blaOXA−48 were consistently detected in all 13 hospital wastewater samples, with highest measured absolute abundances of 1.04 × 108, 4.25 × 107, and 1.17 × 108 copies/100 mL, respectively. Except for blaKPC, they were also found to be positively correlated with each of TP, TN, TKN, and NH3-N (Table S5). The first report of an NDM-1-producing K. pneumoniae in Lebanon was associated with an Iraqi expatriate in 201269,70. Three variants of NDM (NDM-1, NDM-4, and NDM-6) have since been identified in CRE, E. cloacae, E. coli, and K. pneumoniae, isolated from pathological specimens obtained from hospitalized patients in Lebanon. Of these, some E. coli isolates were found to co-harbor blaNDM−4 and mcr-1 genes71. Given their significance as last-resort antibiotics, novel variants of carbapenems such as meropenem-vaborbactam and imipenem-cilastatin are being considered for treatment of CRE infections, but research on implementation of such alternatives is ongoing67,72.

Correlation analysis between the Microbiome and resistome-mobilome

Clusters observed in Bray-Curtis-based PCoA plots were identified and related to variations in both the microbiome and resistome-mobilome of all hospital wastewater samples (Fig. 3-B). While alpha diversity patterns suggested potential regional variation, beta diversity analyses showed that geographic region alone had no significant effect on either (P > 0.05). However, nested PERMANOVA (regions within clusters) revealed statistically significant effects of regional variation on microbial community composition (R² = 0.97, P = 0.001) and resistome-mobilome profiles (R² = 0.85, P = 0.006), indicating localized geographic structuring within clusters. The previously noted higher ARG levels in certain North region hospitals reflect hospital-level variation rather than a broad regional differences. This region-based clustering was evident in the PCoA plots, which showed the grouping of Northern hospitals HWW7, HWW11, and HWW13 based on their microbiome, as well as HWW5, HWW8, and HWW10 based on their resistome-mobilome. Further, samples representing hospitals in the Beirut, Bekaa, and Mount Lebanon regions all showed notable similarity based on their microbiome PCoA, with the only exception being HWW1, which was clustered with HWW8 and HWW10 from the Northern region).

Procrustes analysis was conducted to elucidate the extent to which microbial community composition influenced the resistome-mobilome (Fig. 3-A). A significant correlation between the resistome-mobilome and the microbiome was observed (Procrustes sum of squares: M2 = 0.4665, Correlation: ρ = 0.7304, Significance: P = 0.002, Permutation: free, Number of permutations: 999). These findings highlight the influence of the microbial community on the resistome-mobilome in hospital wastewaters in Lebanon. Given that Procrustes analysis only provides the overall correlation between ARGs, MGEs, and the microbial communities, a Spearman’s correlation analysis was performed to identify specific relationships.

(A) Procrustes analysis of correlations between the microbiome and the resistome-mobilome. Arrows are shown between microbiome and resistome-mobilome coordinates for each HWW sample. Red triangles represent microbiome and blue squares represent resistome-mobilome. (B) Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) of microbiome and resistome-mobilome composition based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrices. Points represent samples, colored by statistically significant k-means clusters (k = 3) and shaped by geographic region, with dashed ellipses indicating 95% confidence intervals (for cluster with ≥ 3 samples). R² values and P-values from PERMANOVA are shown on respective plots. Axis labels indicate the percentage of variance.

Co-occurrence patterns of ARGs and MGEs

MGEs such as transposons and integrons commonly carry ARGs (one or multiple) that are highly prone to horizontal transfer between cells50,73. Due to this, previous works have extensively demonstrated that MGEs and ARGs are commonly co-occurring in various environmental settings74,75. To visualize specific relationships in the hospital wastewaters of this study, a heatmap showing the Spearman correlation coefficients between MGEs and ARGs in all samples was generated (Fig. 4). This analysis showed numerous significant correlations. intI1 was found to influence the most resistance genes (20 positive interactions), followed by the insertion sequence IS6100 (16 positive interactions). Transposons also co-occurred with several ARGs (e.g., aadA1, tet(M), tet(Q)) across multiple classes of antibiotics75,76.

MGEs such as intI1, IS6100, tnpA_1, tnpA_2, and tnpA_3 were significantly linked to a common array of ARGs, including sul1, qacEdelta1, cmlA, blaKPC, blaOXA10, and blaOXA1/blaOXA3044,55,56,77,78. The multidrug resistance gene copA was highly correlated to intI1 and intI3, while both tolC_1 and tolC_2 were significantly associated with IncI1_repI1, suggesting a potential plasmid-mediated dissemination of drug efflux-associated resistance79. Transposase encoding genes tnpA_6 and tnpA_7 displayed significant correlation with the MLSB resistance gene ermB, which has been previously reported80,81. More alarmingly, several MGEs showed significant positive correlations with clinically important ARGs such as vanA and vanB. Vancomycin resistance genes were found to co-occur with intI1, intI3, and IncI1_repI1, suggesting a considerable role for plasmids in the HGT of these ARGs. IncI1, one of the two most common plasmid types associated with the dissemination of antimicrobial resistance genes encoding for third-generation cephalosporins, was significantly correlated with aph(3’’)-ia, floR, and blaCTX−M, as has been previously reported82. Tetracycline resistance genes that are linked to resistance to Reserve group antibiotics, such as tet(Q), tet(M), tet(X), and tet(W) also showed significant positive correlations with tnpA_1, tnpA_5, Tp614, IS613, and repA.

Notable correlations were also observed among the MGEs themselves (Table S8), which may suggest simultaneous transfer of different types of MGEs. Transposition typically occurs when a transposase enzyme recognizes an insertion sequence in the same cell, and integrons are mobilized when present on plasmids or transposons. For instance, intI1 significantly correlated with repA (\(\:\rho\:\)=0.643), tnpA_2 (\(\:\rho\:\)=0.797), and tnpA_3 (\(\:\rho\:\)=0.731). intI1 is commonly located on a plasmid that contains repA, which is necessary for the plasmid replication process73,83. Further, tnpA_1 and tnpA_2, both of which are associated with insertion sequences of the IS6 group, were shown to correlate with IS6100 (belonging to the same family)55,56,84. Abundances of transposons were also previously found to be correlated with occurrence of class 1 integrons74. Overall, the high abundance of MGEs in this study, and their co-occurrence with a wide range of ARGs, underscores the critical need to improve understanding of MGE dynamics so as to limit the dissemination of antibiotic resistance through HGT.

Heatmap showing Spearman correlation coefficients between the normalized abundances of ARGs and MGEs in all hospital wastewater samples. The color gradient within the rectangular box indicates the strength of the Spearman correlation coefficient. Asterisks represent statistical significance correlations (* \(\:\rho\:\) ≥ 0.55, P < 0.05; ** \(\:\rho\:\) ≥ 0.68, P < 0.01).

Network analysis of relationships between microbial communities and ARGs/MGEs

The co-occurrence patterns between microbial genera and genetic elements (ARGs and MGEs) in samples were also examined by network analysis (Fig. 5). The network consisted of 91 nodes (representing 45 microbial taxa and 46 ARGs/MGEs) and 150 edges built from significant positive correlations (ρ > 0.55 and P < 0.05) and a modularity of 0.585. The phylum Pseudomonadota showed the highest number of positive interactions with resistance genes (72). Unclassified Rhodocyclales and Thauera phenylacetica were strongly associated with shared MGEs and ARGs, such as intI1, tnpA_2, tnpA_3, IS6100, qacEdelta1, and blaOXA1/blaOXA30, all of which were correlated (Fig. 4)85,86. These findings suggest that these genetic elements are co-transferred within the same bacterial groups in the wastewater.

Several potentially pathogenic genera, including Arcobacter, Enterococcus, Acinetobacter, Clostridium, Pseudomonas, Escherichia, Klebsiella, Enterobacter, and Aeromonas (among others, Table S9), demonstrated multiple associations with ARGs and MGEs (Figure S3 and Fig. 5), suggesting that these bacteria may serve as significant vectors for waterborne antibiotic resistance arising from clinical settings. Acinetobacter johnsonii was found to be correlated with the floR gene (conferring florfenicol resistance). The presence of the floR gene in Acinetobacter spp. of human origin has been recently reported87. A. johnsonii was also significantly correlated to the MDR gene acrA88.

E. coli were positively associated with genes encoding for multidrug efflux system proteins (acrA and mdtL)89 and MLSB resistance gene (ermX). Some resistance genes were shared among opportunistic pathogens belonging to the phylum Bacillota, such as ermX in Clostridium saudiense, Streptococcus pasteurianus, and Lactobacillus delbrueckii. This finding suggests the presence of common resistance mechanisms among these closely related taxa. In addition, both tet(W) and ermX were significantly linked with genera within Bacillota (including Blautia, Dialister, Mediterraneibacter, Anaerobutyricum, Streptococcus, and Dorea)41 (Figure S3). These gut microbiome-associated groups were found to co-occur in several hospital wastewater samples (Fig. 1).

Aliarcobacter cryaerophilus (Campylobacterota) was found to be a potential host for ARGs associated with phenicol ( catB3 and cmlA…) and vanA90.

Within the Bacteroidota phylum, genera belonging to the Prevotellaceae family, along with Leyella, Segatella, and Massiliprevotella, were positively correlated with common ARGs (tet(Q), ermF, and cfxA) and MGEs (Tp614)91. Similarly, Parabacteroides chartae and Bacteroides graminisolvens were both significantly correlated to tnpA_2 and IS6100, as well as to ARGs associated with these MGEs such as cmlA, qacEdelta1, sul1, blaVEB, and blaOXA1/blaOXA30.

vanA and vanB were found to be associated with multiple Gram-negative microbial genera (an exception being Enterococcus malodoratus) (Figure S3). These ARGs and Gram-negative microbes co-occurred with several MGEs, particularly intI1, IS6100, tnpA_2, and tnpA_3. Such findings suggest a potential for HGT of vancomycin resistance beyond their common enterococcal hosts. Although Gram-negative bacteria are intrinsically resistant to vancomycin, recently developed vancomycin conjugates have demonstrated promising efficacy through disruption of the membrane structure and integrity, enhancing cell permeability92,93. Alarmingly, these results suggest that Gram-negative bacteria harboring vanA and vanB genes could already have the potential to be resistant to these conjugates once clinically approved.

Beyond this, correlations observed in this analysis between mcr2 and Agathobacter rectalis (as well as between several tet genes and other non-pathogenic gut microbes) (Figure S3), raises concerns regarding the potential of clinically-influenced wastewater to serve as a reservoir for the rapid dissemination of resistance to Reserve antibiotics into downstream environments94.

Further, Streptococcus minor, unclassified Actinomycetaceae, and Propionibacteriaceae were also linked to ermB and tnpA_6, suggesting that tnpA_6 may play a role in the mobilization and dissemination of ermB within these bacterial hosts (Figure S3)95,96. These findings indicate that specific microbial genera found in hospital wastewaters can harbor multiple ARGs and MGEs that increase the risk of ARG dissemination into non-clinical environments.

Co-occurrence network analysis of the ARGs-MGEs and microbial taxa present at a normalized abundance of ≥ 2% in at least one hospital wastewater sample (Figs. 2 and S1). Node colors differentiate ARGs, MGEs, and phyla types. Node size is proportional to the number of connections (degree). Edges represent strong and statistically significant positive correlations (Spearman’s ρ > 0.55 and P < 0.05), with edge width proportional to correlation strength.

Conclusion

Hospital wastewater is known to serve as a unique reservoir for antibiotic resistant bacteria and their associated resistance genes. Given the wide range of potential influences on MGE-mediated HGT of ARGs in such environments, acute challenges with understanding (and ultimately limiting) the spread of resistance remain. The work presented here utilized a unique combination of high-throughput qPCR, molecular-based microbial community profiling, and physicochemical water quality characterization to gain globally-relevant insight into trends in ARG co-occurrence with a wide range of significant factors. This study is also the first comprehensive assessment of the antibiotic resistome, mobilome, and microbiome of hospital wastewaters in Lebanon.

Specific relationships between ARGs, MGEs, bacterial groups, and wastewater characteristics were identified in this work. The 13 hospital wastewaters surveyed were found to have widely varying microbial communities, which directly influenced their associated resistomes. ARGs conferring resistance to WHO-classified Reserve group antibiotics were prevalent and appeared to be influenced by hospital region and wastewater characteristics that included nitrogen and phosphorus content. MGEs were widespread across all samples; genes encoding for class 1 and class 3 integrons, as well as specific transposase encoding genes and insertion sequences, showed very high 16 S rRNA gene-normalized abundances. Many of the dominant MGEs and ARGs correlated with individual bacterial groups and physicochemical characteristics, suggesting that tailored water quality parameter-based treatment approaches for hospital wastewaters could be effective at reducing HGT-based spread of ARGs from hospitals. Future research should focus on expanding surveillance to include emerging resistance genes, particularly those that confer resistance to Reserve antibiotics. Additionally, research evaluating the effectiveness of wastewater treatment technologies in reducing the load of ARGs, MGEs, and associated microbial hosts in hospital effluents is needed.

Data availability

All sequences obtained in this study have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under the BioProject accession number PRJNA1179688.

References

WHO. Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 (2019).

Kumar, S. Antimicrobial resistance: A top ten global public health threat. EClinicalMedicine 41, 101221 (2021).

Murray, C. J. et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 399, 629–655 (2022).

Jonas, O. B., Irwin, A., Berthe, F. C. J., Le Gall, F. G. & Marquez, P. V. Drug-resistant infections: a threat to our economic future (Vol. 2): final report (English). HNP/Agriculture Global Antimicrobial Resistance Initiative. Washington, DC: World Bank Group http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/323311493396993758/final-report (2017).

Endale, H., Mathewos, M. & Abdeta, D. Potential causes of spread of antimicrobial resistance and preventive measures in one health perspective-A review. Infect. Drug Resist. 7515–7545 (2023).

Sambaza, S. S. & Naicker, N. Contribution of wastewater to antimicrobial resistance: A review Article. J. Global Antimicrob. Resist. 34, 23–29 (2023).

Bhandari, G. et al. A review on hospital wastewater treatment technologies: current management practices and future prospects. J. Water Process. Eng. 56, 104516 (2023).

Majumder, A., Gupta, A. K., Ghosal, P. S. & Varma, M. A review on hospital wastewater treatment: A special emphasis on occurrence and removal of pharmaceutically active compounds, resistant microorganisms, and SARS-CoV-2. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9, 104812 (2021).

Khan, M. T. et al. Hospital wastewater as a source of environmental contamination: an overview of management practices, environmental risks, and treatment processes. J. Water Process. Eng. 41, 101990 (2021).

Salazar, C. et al. Human microbiota drives hospital-associated antimicrobial resistance dissemination in the urban environment and mirrors patient case rates. Microbiome 10, 208 (2022).

Wang, Q., Wang, P. & Yang, Q. Occurrence and diversity of antibiotic resistance in untreated hospital wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 621, 990–999 (2018).

Gaibani, P. et al. Resistance to ceftazidime/avibactam, meropenem/vaborbactam and imipenem/relebactam in gram-negative MDR bacilli: molecular mechanisms and susceptibility testing. Antibiotics 11, 628 (2022).

Salam, M. A. et al. Antimicrobial resistance: a growing serious threat for global public health. Healthcare vol. 11 (1946) (MDPI, 2023).

Li, W. & Zhang, G. Detection and various environmental factors of antibiotic resistance gene horizontal transfer. Environ. Res. 212, 113267 (2022).

Zhao, K., Li, C. & Li, F. Research progress on the origin, fate, impacts and harm of microplastics and antibiotic resistance genes in wastewater treatment plants. Sci. Rep. 14, (2024).

Tokuda, M. & Shintani, M. Microbial evolution through horizontal gene transfer by mobile genetic elements. Microb. Biotechnol. e14408 (2024).

Allel, K. et al. Trends and socioeconomic, demographic, and environmental factors associated with antimicrobial resistance: a longitudinal analysis in 39 hospitals in Chile 2008–2017. Lancet Reg. Health–Am. 21, (2023).

Collignon, P., Beggs, J. J., Walsh, T. R., Gandra, S. & Laxminarayan, R. Anthropological and socioeconomic factors contributing to global antimicrobial resistance: a univariate and multivariable analysis. Lancet Planet. Health. 2, e398–e405 (2018).

Ammar, W. et al. Health system resilience: Lebanon and the Syrian refugee crisis. J. Global Health. 6, 020704 (2016).

UNHCR & Lebanon, U. N. H. C. R. Fact sheet. Global Focus https://reporting.unhcr.org/lebanon-factsheet-9008 (2024).

Bou Sanayeh, E. & El Chamieh, C. The fragile healthcare system in lebanon: sounding the alarm about its possible collapse. Health Econ. Rev. 13, 21 (2023).

Fadlallah, M., Salman, A. & Salem-Sokhn, E. Updates on the status of Carbapenem-Resistant enterobacterales in Lebanon. Int. J. Microbiol. 2023, 1–10 (2023).

Daoud, Z. et al. Multidrug-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Lebanese hospital wastewater: implication in the one health concept. Microb. Drug Resist. 24, 166–174 (2018).

Hassoun-Kheir, N. et al. Comparison of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and antibiotic resistance genes abundance in hospital and community wastewater: A systematic review. Sci. Total Environ. 743, 140804 (2020).

Shuai, X. et al. Ranking the risk of antibiotic resistance genes by metagenomic and multifactorial analysis in hospital wastewater systems. J. Hazard. Mater. 468, 133790 (2024).

Zhang, S., Huang, J., Zhao, Z., Cao, Y. & Li, B. Hospital wastewater as a reservoir for antibiotic resistance genes: a meta-analysis. Front. public. Health. 8, 574968 (2020).

Hutinel, M., Larsson, D. J. & Flach, C. F. Antibiotic resistance genes of emerging concern in municipal and hospital wastewater from a major Swedish City. Sci. Total Environ. 812, 151433 (2022).

Khan, F. A., Söderquist, B. & Jass, J. Prevalence and diversity of antibiotic resistance genes in Swedish aquatic environments impacted by household and hospital wastewater. Front. Microbiol. 10, 688 (2019).

Paulus, G. K. et al. The impact of on-site hospital wastewater treatment on the downstream communal wastewater system in terms of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes. Int. J. Hyg. Environ Health. 222, 635–644 (2019).

Yao, S. et al. Occurrence and removal of antibiotics, antibiotic resistance genes, and bacterial communities in hospital wastewater. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 28, 57321–57333 (2021).

Lamba, M., Graham, D. W. & Ahammad, S. Hospital wastewater releases of carbapenem-resistance pathogens and genes in urban India. Environmental Science Technology. 51, 13906–13912 (2017).

Wang, Q. & Cole, J. R. Updated RDP taxonomy and RDP classifier for more accurate taxonomic classification. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 13, e01063–e01023 (2024).

Stedtfeld, R. D. et al. Primer set 2.0 for highly parallel qPCR array targeting antibiotic resistance genes and mobile genetic elements. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 94, fiy130 (2018).

Wang, F. H. et al. High throughput profiling of antibiotic resistance genes in urban park soils with reclaimed water irrigation. Environmental Science Technology. 48, 9079–9085 (2014).

Majlander, J. et al. Routine wastewater-based monitoring of antibiotic resistance in two Finnish hospitals: focus on carbapenem resistance genes and genes associated with bacteria causing hospital-acquired infections. J. Hosp. Infect. 117, 157–164 (2021).

Tavares, R. D., Fidalgo, C., Rodrigues, E. T., Tacão, M. & Henriques, I. Integron-associated genes are reliable indicators of antibiotic resistance in wastewater despite treatment-and seasonality-driven fluctuations. Water Res. 258, 121784 (2024).

Bastian, M., Heymann, S. & Jacomy, M. Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. 3 361–362 (2009).

Fruchterman, T. M. & Reingold, E. M. Graph drawing by force-directed placement. Software: Pract. Exp. 21, 1129–1164 (1991).

Fatimazahra, S., Latifa, M., Laila, S. & Monsif, K. Review of hospital effluents: special emphasis on characterization, impact, and treatment of pollutants and antibiotic resistance. Environ. Monit. Assess. 195, 393 (2023).

Hocaoglu, S. M., Celebi, M. D., Basturk, I. & Partal, R. Treatment-based hospital wastewater characterization and fractionation of pollutants. J. Water Process. Eng. 43, 102205 (2021).

Knight, M. E. et al. National-scale antimicrobial resistance surveillance in wastewater: A comparative analysis of HT qPCR and metagenomic approaches. Water Res. 121989 (2024).

Kang, Y., Wang, J. & Li, Z. Meta-analysis addressing the characterization of antibiotic resistome in global hospital wastewater. J. Hazard. Mater. 466, 133577 (2024).

Xu, C. et al. Antibiotic resistance genes risks in relation to host pathogenicity and mobility in a typical hospital wastewater treatment process. Environ. Res. 259, 119554 (2024).

Bian, J. et al. Unveiling the dynamics of antibiotic resistome, bacterial communities, and metals from the feces of patients in a typical hospital wastewater treatment system. Sci. Total Environ. 858, 159907 (2023).

Anugulruengkitt, S. et al. Point prevalence survey of antibiotic use among hospitalized patients across 41 hospitals in Thailand. JAC-Antimicrobial Resist. 5, dlac140 (2023).

He, D. et al. Deciphering the removal of antibiotics and the antibiotic resistome from typical hospital wastewater treatment systems. Sci. Total Environ. 926, 171806 (2024).

Mazhar, S. H. et al. Co-selection of antibiotic resistance genes, and mobile genetic elements in the presence of heavy metals in poultry farm environments. Sci. Total Environ. 755, 142702 (2021).

Siri, Y. et al. Antibiotic resistance genes and crassphage in hospital wastewater and a Canal receiving the treatment effluent. Environ. Pollut. 361, 124771 (2024).

Gillings, M. R. et al. Using the class 1 integron-integrase gene as a proxy for anthropogenic pollution. ISME J. 9, 1269–1279 (2015).

Deng, Y. et al. Resistance integrons: class 1, 2 and 3 integrons. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 14, 45 (2015).

Domingues, S., da Silva, G. J. & Nielsen, K. M. Integrons: vehicles and pathways for horizontal dissemination in bacteria. Mob. Genetic Elem. 2, 211–223 (2012).

Jankowski, P. et al. Metagenomic community composition and resistome analysis in a full-scale cold climate wastewater treatment plant. Environ. Microbiome. 17, 3 (2022).

Gillings, M. R. & Integrons Past, Present, and future. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 78, 257–277 (2014).

Hansson, K., Sundström, L., Pelletier, A. & Roy, P. H. IntI2 integron integrase in Tn 7. J. Bacteriol. 184, 1712–1721 (2002).

Muziasari, W. I. et al. The resistome of farmed fish feces contributes to the enrichment of antibiotic resistance genes in sediments below Baltic sea fish farms. Front. Microbiol. 7, 2137 (2017).

Partridge, S. R., Kwong, S. M., Firth, N. & Jensen, S. O. Mobile genetic elements associated with antimicrobial resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 31, 10–1128 (2018).

Hobeika, W. et al. Resistome diversity and dissemination of WHO priority antibiotic resistant pathogens in Lebanese estuaries. Antibiotics 11, 306 (2022).

WHO. World Health Organization. WHO Access, Watch, Reserve (AWaRe) classification of antibiotics for evaluation and monitoring of use. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MHP-HPS-EML-2023.04 (2023).

Alcock, B. P. et al. CARD 2023: expanded curation, support for machine learning, and resistome prediction at the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D690–D699 (2023).

Al-Mir, H. et al. Emergence of clinical mcr-1-positive Escherichia coli in Lebanon. J. Global Antimicrob. Resist. 19, 83–84 (2019).

Salloum, T. et al. First report of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mcr-8.1 gene from a clinical Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate from Lebanon. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 9, 94 (2020).

Leone, S. et al. Pharmacotherapies for multidrug-resistant gram-positive infections: current options and beyond. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 25, 1027–1037 (2024).

Chamoun, K. et al. Surveillance of antimicrobial resistance in Lebanese hospitals: retrospective nationwide compiled data. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 46, 64–70 (2016).

Moussally, M. et al. Prevalence of antibiotic-resistant organisms among hospitalized patients at a tertiary care center in Lebanon, 2010–2018. J. Infect. Public Health. 14, 12–16 (2021).

Abi Frem, J., Ghanem, M., Doumat, G. & Kanafani, Z. A. Clinical manifestations, characteristics, and outcome of infections caused by vancomycin-resistant enterococci at a tertiary care center in lebanon: A case-case-control study. J. Infect. Public Health. 16, 741–745 (2023).

Purja, S., Kim, M., Elghanam, Y., Shim, H. J. & Kim, E. Efficacy and safety of Vancomycin compared with those of alternative treatments for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections: an umbrella review. J. Evid. Based Med. (2024).

Bassetti, M. et al. Meropenem–Vaborbactam for treatment of Carbapenem-Resistant enterobacterales: A narrative review of clinical practice evidence. Infect. Dis. Ther. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-025-01146-x (2025).

Hall, B. G. & Barlow, M. Revised ambler classification of β-lactamases. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 55, 1050–1051 (2005).

Baroud, M. et al. Underlying mechanisms of carbapenem resistance in extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli isolates at a tertiary care centre in lebanon: role of OXA-48 and NDM-1 carbapenemases. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 41, 75–79 (2013).

El-Herte, R. I. et al. Detection of carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae producing NDM-1 in Lebanon. J. Infect. Developing Ctries. 6, 457–461 (2012).

Al-Bayssari, C. et al. Carbapenem and colistin-resistant bacteria in North lebanon: coexistence of mcr-1 and NDM-4 genes in Escherichia coli. J. Infect. Developing Ctries. 15, 934–342 (2021).

Portsmouth, S. et al. Cefiderocol versus imipenem-cilastatin for the treatment of complicated urinary tract infections caused by Gram-negative uropathogens: a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 18, 1319–1328 (2018).

Popa, L. I., Barbu, I. C. & Chifiriuc, M. C. Mobile genetic elements involved in the horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes. Romanian Arch. Microbiol. Immunol. 77, (2018).

Ouyang, W. Y., Huang, F. Y., Zhao, Y., Li, H. & Su, J. Q. Increased levels of antibiotic resistance in urban stream of Jiulongjiang River, China. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 99, 5697–5707 (2015).

Qian, X. et al. Diversity, abundance, and persistence of antibiotic resistance genes in various types of animal manure following industrial composting. J. Hazard. Mater. 344, 716–722 (2018).

Zhang, B. et al. Distribution of antibiotic resistance genes in karst river and its ecological risk. Water Res. 203, 117507 (2021).

Li, W., Ma, J., Sun, X., Liu, M. & Wang, H. Antimicrobial resistance and molecular characterization of gene cassettes from class 1 integrons in Escherichia coli strains. Microb. Drug Resist. 28, 413–418 (2022).

Chen, F. et al. Uncovering the hidden threat: the widespread presence of chromosome-borne accessory genetic elements and novel antibiotic resistance genetic environments in Aeromonas. Virulence 14, 2271688 (2023).

Krishnamoorthy, G., Tikhonova, E. B., Dhamdhere, G. & Zgurskaya, H. I. On the role of TolC in multidrug efflux: the function and assembly of AcrAB–TolC tolerate significant depletion of intracellular TolC protein. Mol. Microbiol. 87, 982–997 (2013).

Guo, M. T., Yuan, Q. B. & Yang, J. Ultraviolet reduction of erythromycin and Tetracycline resistant heterotrophic bacteria and their resistance genes in municipal wastewater. Chemosphere 93, 2864–2868 (2013).

Wang, L. & Chai, B. Fate of antibiotic resistance genes and changes in bacterial community with increasing breeding scale of layer manure. Front. Microbiol. 13, 857046 (2022).

Foley, S., Kaldhone, P., Ricke, S. & Han, J. Incompatibility group I1 (IncI1) plasmids: their genetics. Biol. Public. Health Relevance 1, (2021).

Frost, L. S., Leplae, R., Summers, A. O. & Toussaint, A. Mobile genetic elements: the agents of open source evolution. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 722–732 (2005).

Zhu, Y. G. et al. Diverse and abundant antibiotic resistance genes in Chinese swine farms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, 3435–3440 (2013).

Zhang, Y. et al. Prevalence of antibiotics, antibiotic resistance genes, and their associations in municipal wastewater treatment plants along the Yangtze river basin, China. Environ. Pollut. 348, 123800 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Mobile genetic elements affect the dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) of clinical importance in the environment. Environ. Res. 243, 117801 (2024).

Tan, B. S. Y. et al. Detection of florfenicol resistance in opportunistic acinetobacter spp. Infections in rural Thailand. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1368813 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Involvement of functional metabolism promotes the enrichment of antibiotic resistome in drinking water: based on the PICRUSt2 functional prediction. J. Environ. Manage. 356, 120544 (2024).

Radi, M. S. et al. Understanding functional redundancy and promiscuity of multidrug transporters in E. coli under lipophilic cation stress. Membranes 12, 1264 (2022).

Ferreira, S., Queiroz, J. A., Oleastro, M. & Domingues, F. C. Insights in the pathogenesis and resistance of arcobacter: a review. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 42, 364–383 (2016).

Lin, Z. J. et al. Behavior of antibiotic resistance genes in a wastewater treatment plant with different upgrading processes. Sci. Total Environ. 771, 144814 (2021).

Chosy, M. B. et al. Vancomycin-Polyguanidino dendrimer conjugates inhibit growth of Antibiotic-Resistant Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative bacteria and eradicate Biofilm-Associated S. aureus. ACS Infect. Dis. 10, 384–397 (2024).

Rahn, H. P. et al. Biguanide-Vancomycin conjugates are effective Broad-Spectrum antibiotics against actively growing and Biofilm-Associated Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative ESKAPE pathogens and mycobacteria. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 22541–22552 (2024).

Zhu, L. et al. Landscape of genes in hospital wastewater breaking through the defense line of last-resort antibiotics. Water Res. 209, 117907 (2022).

Akdoğan Kittana, F. N. et al. Erythromycin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae: phenotypes, genotypes, transposons and Pneumococcal vaccine coverage rates. J. Med. Microbiol. 68, 874–881 (2019).

Fatoba, D. O., Amoako, D. G., Akebe, A. L. K., Ismail, A. & Essack, S. Y. Genomic analysis of antibiotic-resistant Enterococcus spp. Reveals novel enterococci strains and the spread of plasmid-borne tet (M), tet (L) and erm (B) genes from chicken litter to agricultural soil in South Africa. J. Environ. Manage. 302, 114101 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Litani River Authority for their assistance in collecting wastewater samples from the Bekaa Region.Icons used in the graphical abstract were obtained from BioRender.com.

Funding

This study was funded by the President Intramural Research Fund (PIRF) of the Lebanese American University (Grant Number: PIRF- I0065).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.G. Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. L.R. Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—review and editing. J.A. Conceptualization. M.H. Validation, Writing—review and editing. M.W. Resources, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Conceptualization, Validation, Writing—review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Greige, S., Ramadan, L., Al-Alam, J. et al. A quantitative characterization of antibiotic resistance and its influencing factors in hospital wastewaters across Lebanon. Sci Rep 16, 2108 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31879-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31879-1