Abstract

Given the undeniable advantages of quantum computers, several methods have been proposed to create compact and versatile quantum systems. Among these methods, integrated quantum optics processors have garnered significant attention, leading to the proposal of various quantum-based optical devices. Since the advent of quantum computers, incoherence in qubit processes has posed a challenge, manifesting in numerous forms. This incoherence results in changes and distortions of system states during processing. While quantum optical systems have advantages over conventional technologies, they are not immune to this issue. In our research, we demonstrate that random imperfections in waveguide walls during manufacturing (etching) can be a major source of decoherence in quantum optical devices, potentially distorting quantum states over medium to long distances. We compare various semiconductor materials and fabrication technologies and find out that InP/InGaAsP, SiON, Si3N4, and silica are suitable materials for fabricating quantum waveguides. In contrast, the silicon-on-insulator (SOI) platform has quantum crosstalk lengths of only 1 mm and 180 microns for 50 and 30% coupling as the minimum and maximum threshold conditions, respectively. Using conventional fabrication methods could lead to short quantum crosstalk lengths and hinder quantum processing capabilities. Hence, precise methods must be employed to effectively fabricate waveguides using SOI technology. Based on the decoherence properties, this work determines the appropriate quantum-grade platforms for devices utilized in quantum processing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum processing has been proposed due to the demand for high-speed processing. Some characteristics of an ideal quantum processor are the ability to parallel and fast process, integration capability, and CMOS compatibility. It is tough to aggregate all these features in a chip. Moreover, electronic devices tend to be smaller and smaller; hence, the consideration of quantum mechanical effects is inevitable1. However, at these dimensions, the quantum mechanical behavior of atoms prevails, and hence, considering the quantum effects is crucial to designing the circuits. Although many efforts are underway using classical approaches to overcome these limitations, quantum algorithms must be processed by quantum-based devices for maximum efficiency2. Hence, the necessity of quantum computers is undeniable. The prominent advantage of the quantum computer compared to the conventional one is its speed in processing some algorithms. One of the most important of these is the algorithm that Shor presented in 19953. Five basic standards, presented as the fundamental requirements to realize the quantum computer, are as follows4. Hilbert Space control and manipulation, state preparation, state-specific quantum measurement, controlled unitary transformation, and low decoherence. Decoherence, the loss of quantum information due to unwanted interactions, is a significant obstacle to constructing quantum computers. It is very difficult to design a quantum system in which the effect of these interactions is minimized during the processing of quantum states and the coherence of the quantum states is maintained. Several algorithms have been proposed to correct the errors originating from these unwanted effects, including the famous algorithm proposed by Shor5. According to the accuracy threshold criterion, the decoherence must be at least 1 million times greater than the quantum switching time (time required for gate operations)4,6. This strict condition requires a powerful quantum system with very high coherence. Various other designs that have the so-called five standards have been proposed using electrons in atoms or ions7,8, photons9, cavity quantum electrodynamic10, atomic spin or magnetic resonance11,12, solid state13, and superconducting systems. Of all the systems presented, the photon-based quantum system technology is the most promising for the following reasons: low noise as a result of photons’ low interaction with the environment, easy manipulation, high-speed transition due to photon traveling speed, and most importantly, CMOS compatibility and well integration capability. Several optical quantum gates, such as the NOT gate14, Fredkin gate15, control NOT gate9 Conditional-phase switch16, have been proposed in recent years. There are many tools and facilities in quantum optics for quantum processing. It has been shown that any two-bit algebraic operation can be performed with a controlled-NOT (CN) gate between two qubits and a rotation around a single bit17. The entanglement enables quantum systems to perform different calculations in parallel18. Providing methods of entangled states in quantum optics-based systems is more diverse than in other systems. Atom-cavity systems, solid-state emitters, and spontaneous parametric down-conversion are utilized to generate entangled states. However, quantum processors based on quantum optics have a weak coherence level. The qubit can be implemented based on multiple degrees of freedom (DoFs), such as path, polarization, frequency, and transverse spatial modes, in photonic quantum circuits19,20,21,22,23. ññatial modes method is of increasing interest due to its compatibility with other quantum applications, such as implementing quantum interference21, on-chip transverse-mode entangled photon pair sources22, and 2-qubit quantum gates with mode encoding23. Since encoding qubits based on transverse spatial modes requires multimode devices, and many of the designed gates, such as the C-NOT and T-FLIF, induce multimode operations, our analysis in this paper essentially involves multimode waveguides. The present study investigates the modal crosstalk originating from the irregularities in the waveguide’s wall. Initially, we analytically examine the wall irregularities and demonstrate that they can induce coupling between modes in a multimode waveguide. Subsequently, we compare the analytical results with those obtained by the finite element method simulation. Furthermore, we calculate the wall coupling rate for a random wall shape using data from various manufacturing processes. Ultimately, by comparing multiple technologies and platforms, we demonstrate which one is most compatible with quantum applications.

Mode coupling in the slab waveguide due to imperfection

Since any practical waveguide can be approximated as a slab waveguide using effective index theory, we have employed the dual-mode slab waveguide to avoid further complexity. Figure 1a demonstrates an ideal slab waveguide with the core thickness (2d) equal to 1 μm, and the RI for core and cladding are ncore=1.9963 and nclad=1.44, respectively. As shown in Fig. 1c, this dimension is chosen so that the waveguide is two-mode and \(\:{{\upbeta\:}}_{0\:}\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\:{{\upbeta\:}}_{1}\) are equal to 7.7601 × 106 and 6.7628 × 106 [1/m], respectively, for the wavelength of 1.55 μm. This waveguide is excited by a transverse electric (TE) field so that two-mode propagation occurs. The electric field for a single-mode waveguide is described by Eq. (1):

In which \(\:{C}_{in}\) is a complex number representing the amplitude, \(\:E\left(x\right),\:\)is the mode profile, and β is the wave number. The expansion of a weighted aggregate of ideal normal modes can represent the propagated wave within the multi-mode waveguide24,25,26,27. Equation (2) demonstrates the wavefunction within a two-mode waveguide, depicted in (Fig. 1b), through the superposition of normal modes, \(\:{E}_{0}\left(x\right)\) and \(\:{E}_{1}\left(x\right)\), with the respective amplitude, C0, and C1, calculated by Eq. (3).

(a) 3-dimensional view of slab waveguide (b) TE Mode propagation through waveguide (c) The dispersion curve for the waveguide. The waveguide is designed so that at 1.55 μm, indicated by the vertical red line, the wave propagates with two normal modes. The 3D figure was created by Blender ver. 2.93 (https://download.blender.org/release/).

The electric field distribution in the slab waveguide is a solution of Eq. (4), where n is the position-dependent refractive index, and k is the vacuum wave vector.

\(\:{n}^{2}(x,z)\) can be considered as an aggregate of two individual parts in which \(\:{n}_{0}^{2}\:\)is the invariant part of the refractive index and \(\:{\varDelta\:n}^{2}\left(x,z\right),\:\) describes the effects of imperfection on the change in the refractive index25.

Substituting Eq. (2) in Eq. (5) and using normal mode orthogonality leads to Eq. (6), where P is the incident power per unit length, and \(\:{C}_{m}\) and \(\:{C}_{n},\) are complex coefficients introduced in Eq. (3)27,28:

These coefficients are constant without any coupling. The coupling caused by any imperfection, such as wall imperfections or longitudinal inhomogeneities in the refractive index, leads to energy transfer between two modes and consequently changes the coefficients along the waveguide length. Considering C0 and C1 slowly varying amplitudes, Eq. (6) for two modes that can be coupled is written as Eq. (7), where the coupling coefficient, κ01, is given by:

Introducing \(\:\varDelta\:P\:\)as the power loss of the incident mode due to mode conversion and neglecting trivial backward wave coupling due to significant phase mismatch, \(\:{\beta\:}_{0}+{\beta\:}_{1}\), the relative power loss, \(\:\frac{\varDelta\:P}{P}\), is given by25:

The modal analysis of the slab waveguide with a thickness of 2d yields two types of modes, even and odd, as expressed by Eq. (9), in which κ and γ are given by Eqs. (10), and k0 is the free space wave vector25. :

\(\:\gamma\:=\sqrt{{\beta\:}^{2}-{{k}_{0}}^{2}{n}_{clad}^{2}}\)

The coupling coefficient between the first two modes (Eq. (7)) can be written using Eq. (9) as:

Wall imperfection-induced coupling

The incident mode retains its power during propagation in the ideal waveguide; however, any inhomogeneity in the refractive index or roughness in the waveguide wall can cause power mode conversion. Figure 2 shows a slab waveguide in which the interface between the core and cladding regions deviates slightly from being straight. The roughnesses of up and down interfaces are expressed by f(z) and h(z) herein and are considered tiny compared to the thickness of the waveguide. Therefore, the modes can be regarded as unchanged, and the perturbation method can be utilized to analyze the wave propagation. Moreover, the roughness-induced loss is neglected herein because the roughness is tiny. The frequency spectrum of f(z) and h(z) can be determined using the Fourier transform. As shown in Fig. 2, a frequency component corresponding to \(\:{\beta\:}_{0}-{\beta\:}_{1}\) is necessary for power exchange between modes.

Dielectric slab waveguide with distorted core-cladding interface. f(z)-d is an arbitrary function that describes the random variations of the upper core-cladding boundary of the waveguide. The frequency spectrum of this function includes the frequency corresponding to \(\:{\beta\:}_{0}-{\beta\:}_{1}\), which provides a phase-matching condition. This frequency causes coupling between the TE0 and TE1 modes. This waveguide is equivalent to a waveguide with a sinusoidal wall with a period of 2π/(\(\:{\beta\:}_{0}-{\beta\:}_{1}\)) frequency. The 3D figure was created by Blender ver. 2.93 (https://download.blender.org/release/).

Wave propagation in such a waveguide is similar to that in a waveguide with a sinusoidal wall with a period of \(\:2\pi\:/({\beta\:}_{0}-{\beta\:}_{1})\) frequency. For arbitrary core-cladding interface shapes, the coupling coefficient is obtained using Eq. (12), where L is the perturbation length27.

The wall imperfection is assumed to be sinusoidal, as given by Eqs. (13), in which the maximum value of the roughness is 1% of the core thickness (2d).

\(\:f\left(z\right)=0.01*d*\text{s}\text{i}\text{n}\left(\left({\beta\:}_{0}-{\beta\:}_{1}\right)*z\right)\) +d

There is no coupling between modes for θ = 0; however, the coupling occurs for θ = π. For a waveguide without imperfections in refractive index and geometry, the modes are orthogonal; hence, there is no coupling between them. This orthogonality is expressed by a zero-overlap integral given by Eq. (14)28,29.

Figure 3a shows the shape of modes, \(\:{E}_{1}\left(x\right)\) and \(\:{E}_{2}\left(x\right)\) and their product \(\:{E}_{1}\left(x\right)\)*\(\:{E}_{2}\left(x\right)\). Any imperfection that disrupts the geometrical symmetry results in a nonzero overlap integral and coupling between modes. For imperfections expressed by Eq. (13), theta = pi leads to antisymmetric disruption, demonstrated in (Fig. 33); therefore, the coupling between the first two modes occurs, as seen in (Fig. 3d). Nevertheless, theta = 0 (Fig. 33) cannot cause coupling, depicted in (Fig. 3e), because it does not break symmetry.

(a) Shape of the modes \(\:{E}_{1}\left(x\right)\) and \(\:{E}_{2}\left(x\right)\) and their product \(\:{E}_{1}\left(x\right)\)*\(\:{E}_{2}\left(x\right),\) in the ideal slab waveguide. (b) The waveguide with the antisymmetric sinusoidal walls has a nonzero overlap integral. (c) The waveguide has symmetric sinusoidal walls with zero overlap integral. (d) Finite element simulation of the waveguide depicted in (b). (e) Finite element simulation of the waveguide depicted in (c).

The alteration of mode amplitudes is obtained using the finite element method (FEM) and is depicted in (Fig. 4a). The results obtained by coupled mode equations (Eq. (7)), given in (Fig. 4b), confirm the simulation results.

Furthermore, both results indicate that the coupling length, which represents the length at which the electromagnetic energy is completely transferred from one mode to another, is 325 μm. Two other core-cladding interface profiles are assumed herein: square and saw tooth. As seen from Fig. 5a, b, the square wall shape’s deviation amplitude is considered 7.5 nm. The period of change in the z-direction is similar to the previous one; the change in the up and down interfaces has a 180 ° phase difference. The coupling process is illustrated in (Fig. 5c, d) for the analytic and simulation results, respectively. Moreover, the 2-dimensional simulation results are presented in (Fig. 5e), where the transformation from the first mode to the second and vice versa is visible.

(a) and (b) are the core-cladding interface with a square shape at the up and down boundaries. The maximum value of roughness is 7.5 nm (c), the variation of probabilities obtained by coupled mode equations. (d) The variation of probabilities obtained by FEM. (e) 2 d 2-dimensional view of wave propagation.

Figure 6a, b show the deviation amplitude of 25 nm for the saw tooth. The period of change in the z direction equals the square shape with a 180° phase difference between the up and down interfaces. The results obtained using coupled-mode equations and FEM simulation are demonstrated in (Fig. 6c, d), respectively. Similar to the previous figure, the mode transformation can be seen in (Fig. 6e).

(a) and (b) are the core-cladding interface with a saw tooth shape at the up and down boundaries. The maximum value of roughness is 25 nm (c), as shown by the variation of probabilities obtained from coupled mode equations. (d) The variation of probabilities obtained by FEM. (e) 2-dimensional view of wave propagation.

The coupling length increases with the increasing value of interface roughness—the more roughness, the larger the coupling coefficient and, consequently, the smaller the coupling length (Eq. (15))29.

The sinusoidal core-cladding interface is used to investigate the effect of imperfection on the coupling length. The sinusoidal alteration, with a maximum of 5 nm, depicted in (Fig. 7a), causes the coupling shown in (Fig. 7b), which represents a coupling length of 330 μm. However, considering the maximum sinusoidal alteration of 15 nm, shown in (Fig. 7c), results in the coupling depicted in (Fig. 7d). As is expected, the increasing roughness in the core-cladding interface increases the coupling between modes and consequently decreases the coupling length to 113 μm. The functions f(z) and h(z) are generally random, depending on various parameters such as fabrication technology; hence, solving the coupled mode equations is complicated in this case. For this reason, the statistical evaluation is required to investigate mode coupling. Therefore, the average of random amplitudes is utilized instead of the exact value of amplitudes, which are not accessible. To this end, the ensemble average of \(\:〈{\left|{C}_{n}\left(z\right)\right|}^{2}〉\), defined as average mode power, is used to investigate the energy transfer between modes28. Changes in average power can be expressed by:

Investigation of the effect of roughness amplitude in mode coupling. (a) The sinusoidal core-cladding interface with a maximum roughness of 5 nm (b) illustrates the probability of amplitude alteration due to imperfection coupling, as shown in (a). The coupling length is 330 μm (c), the sinusoidal core-cladding interface with the maximum roughness of 15 nm (d), and probability amplitudes alteration due to coupling for imperfection depicted in (c). The coupling length is 113 μm.

Utilizing the coupled mode equations given by Eq. (7), the coupled equations representing the power transfer between modes are obtained as23:

Where R(x) is the autocorrelation function of f(z) and \(\:{\kappa\:}_{01}\) is obtained by Eq. (11) and given by:

One of the most widely used statistical properties for the stationary random process is its autocorrelation function, and according to the definition, it is written as follows:

u is the displacement in the z-direction. The correlation function measures the correlation between two adjacent points on the walls, separated by 1 m. Various reports have been presented that announce this function has a Gaussian distribution30,31,32,33:

Where \(\:\sigma\:\) and D are the variance and correlation length of f(z), respectively. Table 1 reports typical values of and D of the devotion function f(z) for different waveguides. In Fig. 8, different autocorrelation values are plotted versus u. A dashed line demonstrates the average of these functions. The values of D and sigma are 56 nm and 6 nm, respectively30.

The function \(\left\langle {\left. {\left| {F\left( {\Delta \beta _{{10}} } \right)} \right|^{2} } \right\rangle } \right. ,\) that appeared in Eq. 8 calculates the power spectrum of the correlation function by taking the Fourier transform of \(\:R\left(u\right)\).

From an information point of view, the length that coupling causes the probability amplitudes to be equal is defined as quantum crosstalk length because, in that situation, the transmitted quantum information cannot be extracted from the perturbed one that was received. Let’s assume the first mode probability amplitude is 1 and the second one is zero, which denotes the transmission of the ground state. This state is transformed into a superposition of the ground (first mode) and excited states (second mode) due to coupling between these states. If the share of the excited state in the superposition is below 50%, it can be inferred from the received data that the transmitted one because the probability amplitudes are obtained in output measurement. Both probability amplitudes for the ground state and the second state are equal in 50% coupling and hence cannot be recognized that the transmitted state is the ground state. Therefore, the length that the weight of both modes in superposition comes to 0.5 is the quantum crosstalk length. This factor is especially important in quantum processing and the realization of Qubits. To derive the quantum crosstalk length, Eq. (21) are first utilized to obtain the power related to each mode depicted in (Fig. 9a). It is observed that the quantum crosstalk length is 650 μm. Furthermore, the finite element method is used to end absolute value squaed, close angle bracket and open angle bracket absolute value cap C sub 1he calculation of \(\left\langle {\left. {\left| {C_{0} } \right|^{2} } \right\rangle } \right.\) and \(\left\langle {\left. {\left| {C_{1} } \right|^{2} } \right\rangle } \right.\) are required. 1 million different randomness are applied to Eq. (12) to obtain the coupling coefficient and consequently the complex amplitudes are calculated using Eq. (7). The results are demonstrated in (Fig. 9b).

Table 1 presents the values of σ and D in some CMOS-compatible platforms. Furthermore, the results for InP/InGaAsP platform, which is not CMOS-compatible, are also presented in Table 1 for comparison. The core thickness, d, is determined so that all waveguides are two-mode at 1.55 μm. It is reminded that the current research is based on two-mode waveguides at a wavelength of 1.55 micrometers.

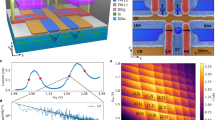

Therefore, it can be expected that the thickness of the waveguide core in each manufacturing technology will have different values due to the difference in the refractive index of the core. The quantum crosstalk length exceeds 50 mm in the SOI, silica, and Si3N4 platforms, which is acceptable for optical waveguides used in quantum technologies. The atomic force microscopy (AFM) image of the waveguides produced on the SOI platform shows that the deviation from the roughness criterion of the waveguide walls is a maximum of 2 nm, which is described by a correlation length of 50 nm with a Gaussian distribution, as given in Eq. (20)23. The SOI-based waveguides can be fabricated using three methods: conventional fabrication, oxidation smoothing, and anisotropic etching, with the values of σ and D listed in (Table 1)18. As shown in Fig. 10, among these three methods, the traditional method has the shortest quantum crosstalk length, approximately 1 mm. It should be noted that if we restrict the maximum power coupling more strictly, the quantum crosstalk length becomes shorter and more reliable. For example, when the probability amplitudes of the first and second modes are 0.6 and 0.4, respectively, the length of the amplitudes becomes 0.5, which is shorter than in the previous case. In Table 2, we have examined the challenge of how the quantum crosstalk length values change if the maximum allowed energy transfer is 30 and 40%. Under these conditions, in the case of SOI with the traditional method, the quantum crosstalk length decreases by about 70 and 80% for 30 and 40% coupling, respectively. The silicon nitride platform’s quantum crosstalk length decreases to 7 and 13.9 mm. The quantum crosstalk lengths of 400 and 700 μm are obtained for silica in 30 and 40% coupling, respectively. However, since the SION and indium phosphide exhibit considerable quantum crosstalk lengths at 50% coupling, despite decreases in coupling of 30 and 40%, the quantum crosstalk length remains larger than 50 mm.

Figure 11a illustrates the quantum crosstalk lengths of different platforms in comparison with one another. Contrary to the InP/InGaAsP and SiON waveguides (Fig. 11b), depicts the quantum crosstalk length in SOI, silica, and Si3N4 waveguides are suitable for quantum applications.

Comparison of quantum crosstalk length in waveguides produced by different technologies. (a) Among the three low crosstalk length technologies — SOI, Si3N4, and Silica —the SOI waveguide has the lowest quantum crosstalk length. (b) SiON and InP/InGaAsP have quantum crosstalk lengths exceeding 50 microns.

Conclusion

Various undesirable random processes can disrupt the quantum information processing in integrated photonics. In this research, the nonidealities of the core-cladding interface in optical waveguides, as one of the sources of disruption, were investigated. Initially, the shape of the core-cladding interface was considered sinusoidal, square, and sawtooth, and their effects on mode coupling were investigated. Secondly, the imperfection in the core-cladding interface was supposed to occur due to a random process. Investigating random phenomena requires statistical analysis; hence, the average power coupling equations were utilized instead of the conventional coupled-mode equations. Five popular platforms, including silicon-on-insulator (SOI), silicon nitride, silica, SION, and indium phosphide, were considered herein to determine their quantum crosstalk length as a criterion for the maximum length of the optical waveguide usable for quantum photonic devices. Furthermore, the quantum crosstalk length was obtained for three fabrication methods in the SOI platform. The SOI platform, implemented using conventional fabrication technology, represents a minimum quantum crosstalk length of 1 mm. Oxidation smoothing in SOI results in the best quantum crosstalk length of 50 mm. Similarly, the SION and InP platforms also represent the quantum crosstalk length of 50 mm.

Data availability

All data generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

O’Brien, J. L., Furusawa, A. & Vučković, J. Photonic Quantum Technol. Nat. Photonics. 3 (12), 687–695, (2009).

Radack, D. J. & Zolper, J. C. A future of integrated electronics: moving off the roadmap. In Proceedings of the IEEE. vol. 96 (2), pp. 198–200, (2008).

Shor, P. W. Algorithms for quantum computation: discrete logarithms and factoring. In Proceedings 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science. pp. 124–134. ( IEEE, 1994).

DiVincenzo, D. P. & Loss, D. Quantum information is physical. Superlattices Microstruct. 23 (3–4), 419–432 (1998).

Shor, P. W. Scheme for reducing decoherence in quantum computer memory. Phys. Rev. A. 52 (4), R2493 (1995).

Preskill, J. Reliable quantum computers. Proceedings of the royal society of London. Ser. A: Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 454, (1998) 385–410, (1969).

Cirac, J. I. & Zoller, P. Quantum computations with cold trapped ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74 (20), 4091 (1995).

Jaksch, D. et al. Fast quantum gates for neutral atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85 (10), 2208 (2000).

D’Ariano, G., Macchiavello, C. & Maccone, L. Quantum computations with polarized photons. Fortschritte der Physik: Progress of Phys. 48 (5-7), pp. 573–577, (2000).

Turchette, Q. A., Hood, C. J., Lange, W., Mabuchi, H. & Kimble, H. J. Measurement of conditional phase shifts for quantum logic. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75 (25), 4710 (1995).

Gershenfeld, N. A. & Chuang, I. L. Bulk spin-resonance quantum computation. Science 275 (5298), pp. 350–356, (1997).

Jones, J. A., Mosca, M. & Hansen, R. H. Implementation of a quantum search algorithm on a quantum computer. Nature 393 (6683), 344–346 (1998).

Kane, B. E. A silicon-based nuclear spin quantum computer. Nature 393 (6681), 133–137 (1998).

Fu, J. Quantum computations with optical waveguide modes. In Quantum Information and Computation 5105, pp. 225–233. (SPIE, 2003).

Milburn, G. J. Quantum optical Fredkin gate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 62 (18), 2124 (1989).

Resch, K. J., Lundeen, J. S. & Steinberg, A. M. Conditional-phase switch at the single-photon level. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89 (3), 037904 (2002).

Sleator, T. & Weinfurter, H. Realizable universal quantum logic gates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74 (20), 4087 (1995).

Jozsa, R. Entanglement and quantum computation. arXiv (1997).

Defienne, H. et al. Two-photon quantum walk in a multimode fiber. Sci. Adv. 2 (1), 1–6 (2016).

Feng, L. T. et al. On-chip coherent conversion of photonic quantum entanglement between different degrees of freedom. Nat. Commun. 7 (1), 11985 (2016).

Mohanty, A. et al. Quantum interference between transverse Spatial waveguide modes. Nat. Commun. 8 (1), 14010 (2017).

Feng, L. T. et al. On-chip transverse-mode entangle photon pair source. NPJ Quant. Inf. 5 (1), 2 (2019).

Feng, L. T., Zhang, M., Xiong, X. et al. Transverse mode-encoded quantum gate on a silicon photonic chip. Phys.Rev. Lett. 128 (6), 060501 (2022).

Fu, J., Si, Z., Tang, S. & Deng, J. Classical simulation of quantum entanglement using optical transverse modes in multimode waveguides. Phys. Rev. A—Atomic Mol. Opt. Phys. 70 (4), 042313 (2004).

Marcuse, D. Mode conversion caused by surface imperfections of a dielectric slab waveguide. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 48 (10), 3187–3215 (1969).

Marcuse, D. Theory of Dielectric Optical Waveguides (Elsevier, 2013).

Marcuse, D. Derivation of coupled power equations. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 51 (1), 229–237 (1972).

Yariv, A. & Nakamura, M. Periodic structures for integrated optics. IEE J. Quantum Electron. 13 (4), 233–253 (1977).

Nishihara, H. Optical integrated circuits. Rev. Laser Eng. 8 (4), 632–643 (1980).

Melati, D., Melloni, A. & Morichetti, F. Real photonic waveguides: guiding light through imperfections. Adv. Opt. Photon. 6 (2), 156–224, (2014).

Ogilvy, J. & Foster, J. Rough surfaces: Gaussian or exponential statistics? J. Phys. D 22 (9), 1243 (1989).

Lacey, J. & Payne, F. Radiation loss from planar waveguides with random wall imperfections. IEE Proc. J. (Optoelectronics) 137 (4), 282–289, (1990).

Payne, F. P. & Lacey, J. P. A theoretical analysis of scattering loss from planar optical waveguides. Opt. Quant. Electron. 26, 977–986 (1994).

Krivoshlykov, S. G. Quantum-theoretical Formalism for Inhomogeneous graded-index Waveguides (No Title), (1994).

Lee, K. K., Lim, D. R., Kimerling, L. C., Shin, J. & Cerrina, F. Fabrication of ultralow-loss Si/SiO 2 waveguides by roughness reduction, optics letters. 26 (23), 1888–1890, (2001).

Vlasov, Y. A. & McNab, S. J. Losses in single-mode silicon-on-insulator strip waveguides and bends. Opt. Express. 12 (8), 1622–1631 (2004).

Xia, F., Sekaric, L. & Vlasov, Y. Ultracompact optical buffers on a silicon chip. Nat. Photonics. 1 (1), 65–71 (2007).

Barwicz, T. & Haus, H. A. Three-dimensional analysis of scattering losses due to sidewall roughness in micro photonic waveguides. J. Lightwave Technol. 23 (9), 2719 (2005).

Bauters, J. F. et al. Ultra-low-loss high-aspect-ratio Si 3 N 4 waveguides. Opt. Express. 19(4), 3163–3174 (2011).

Kim, B., Lee, B. T. & Han, J. G. Surface roughness of silicon oxynitride etching in C2F6 inductively coupled plasma. Solid State Electron. 51 (3), 366–370 (2007).

Zhao, W., Bae, J., Adesida, I. & Jang, J. Effect of mask thickness on the nanoscale sidewall roughness and optical scattering losses of deep-etched InP∕ InGaAsP high mesa waveguides. J. Vacuum Sci. Technol. B: Microelectron. Nanometer. Struct. Process. Meas. Phenomena 23 (5), 2041–2045, (2005).

Jang, J. et al. Direct measurement of nanoscale sidewall roughness of optical waveguides using an atomic force microscope. Appl. Phys. Lett. 83 (20), 4116–4118 (2003).

Li, L., Abe, T. & Esashi, M. Smooth surface glass etching by deep reactive ion etching with SF 6 and Xe gases. J. Vacuum Sci. Technol. B: Microelectr. Nanometer. Struct. Process. Meas. Phenomena 21 (6), 2545–2549, (2003).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the University of Tabriz (No. 1277).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E. A. wrote the paper and simulated the results. H.A. simulated the results and wrote the paper, and A.R.supervised the project, proposed the basic idea, and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Azough, E., Ahmadi, H. & Rostami, A. Effect of waveguide wall roughness on quantum signal transmission. Sci Rep 16, 2090 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31901-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31901-6