Abstract

Virtual mechanical testing on image-based bone models (digital twins) provides subject-specific insights about the mechanical behavior of a bone during fracture healing. However, the established workflows for these tests are limited by reliance on commercial software and time-consuming manual procedures needed to create the digital twins. To overcome these barriers to clinical adoption and scalability, we have developed methods for user-independent and automated model generation. This study aimed to: (1) compare four competing methods for digital twin creation (two manual versus two automated approaches), (2) assess the influence of model-creation procedures and choice of material model (single- and dual-zone) on the virtual test results, and (3) evaluate the accuracy of the model-creation techniques through experimental validation of the results. Digital twins were generated from 59 CT scans (33 operated osteotomy fractures, 26 contralateral intact bones). Torsional rigidities were compared between modeling workflows and validated using postmortem physical mechanical test data. There were no significant differences in torsional rigidity between any of the four virtual testing groups and physical testing when a dual-zone material model was implemented for bone and callus. These results confirm that virtual mechanical testing is a reliable alternative to physical mechanical testing for assessing intact and healing long bones, with resilience to variations in digital twin creation methods. Automated model creation was substantially faster than the manual approaches, suggesting that automatic digital twin analysis is the pathway toward future clinical scalability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bone fractures impact are associated with substantial healthcare burdens1. Most fractures heal within a few months, but sometimes healing fails and a nonunion occurs. Failed fracture healing is a widespread problem; for instance, each year in the U.S., over 100,000 fractures go on to nonunion and require secondary surgery2. In the lower extremities, tibial fractures are particularly prone to nonunion, occurring at an average rate of 12% across all injury severity levels3,4,5,6,7,8,9. Tibial fractures also have high rates of delayed healing, with one in four patients not healed after five months9. Nonunion is a complex, multifactorial problem with vascular, biological, and mechanical risk factors4,6,7,9,10,11,12,13. Risk stratification scoring systems can help identify which patients are at risk for delayed healing and nonunion11, but currently, nonunion cannot be definitively predicted using only the information available at the time of surgery8,14,15.

A critical barrier to improving fracture care through better prevention and treatment of nonunion is the lack of widely available image-based mechanical biomarkers that can measure bone healing objectively and complement existing diagnostic criteria to detect nonunion early. To address this need, we previously developed a technique for virtual mechanical testing of tibial fracture healing using image-based finite element (FE) models. These models enable a quantitative, objective, and noninvasive calculation of the tibial torsional rigidity in sheep and humans. When used to measure fracture healing, virtual torsional rigidity (VTR) shows superior ability to predict bone biomechanics and time to union compared to callus morphometric measures and radiographic scores16,17,18,19. Our methods have been validated preclinically against postmortem physical tests18,19,20, are applicable to low-dose clinical CT scans21,22, and can detect differences in healing related to biological comorbidities23 or implant type24. However, the methods used to perform this analysis are both time- and resource-intensive, a major limitation to widespread clinical use.

Scaling the capacity for image-based measurement of bone healing requires automation of several steps in the process. The first step in virtual mechanical testing involves conversion of a bone CT scan to a high-fidelity digital twin – a surrogate model created from textural and structural information in the image of a physical bone with shape and material properties that mimic in vivo bone and callus. The second step is simulating the mechanical response of the digital twin to a mechanical load and reporting the results to yield reliable and clinically interpretable insights25. Our previously established methods for virtual mechanical testing of fracture healing have relied on the use of commercial software with a highly trained user to perform the image processing steps needed to build the digital twins and set up the models for mechanical analysis. Despite the promising results, the expensive software licenses, user-dependency, and labor-intensive nature of the procedures remain significant challenges. Future scalability for use in larger clinical studies or as a diagnostic test requires the development of a user-independent, high-throughput, automatic approach to FE model generation. However, the available manual and automated workflows vary markedly in their segmentation methods, meshing configurations, and level of user interaction, yet their effects on virtual torsional rigidity have not been rigorously evaluated. A systematic comparison is thus required to establish whether these methodological variations impact the virtual test results and to assess whether our automated pipelines perform comparably to our previously published manual workflows.

Accordingly, the objectives of this study were to (1) compare four competing methods for digital twin creation (two manual versus two automated approaches), (2) assess the influence of model-creation procedures and choice of material model on the virtual test results, and (3) evaluate the accuracy of the model-creation techniques through experimental validation of the results (Fig. 1). These techniques had been developed in our previous publications, but have never been compared head-to-head.

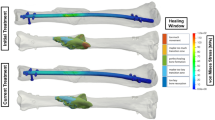

Study overview: digital twins of contralateral and operated ovine bones were created using (a) two methods for manual (software-assisted) model creation, and (b) two methods for automated model creation. (c) All models were subjected to virtual torsion testing. (d) The resulting torsional rigidities were compared to assess differences arising from: model creation workflows and tissue material properties models. Computational models were generated with different mesh types and further validated by comparison to experiments.

Materials and methods

Animal data

The animal data consisted of \(\:{N}_{op}\) = 33 operated tibiae and \(\:{N}_{con}\) = 26 intact contralateral tibiae from skeletally mature Swiss alpine sheep (age 2–3 years), which were obtained from two previously completed research studies18,26. The first study included operated tibiae with 3 mm osteotomies stabilized by 6-hole titanium plates (broad straight veterinary 4.5/5.0 mm locking compression plate (LCP) with 5 mm bicortical screws; DePuy Synthes, West Chester, PA, USA). The second study had contralateral intact and operated tibiae with 3–17 mm osteotomies stabilized by 11- or 12-hole stainless steel plates (broad straight veterinary 3.5 mm locking compression plate (LCP) with 3.5 mm bicortical screws; DePuy Synthes). All animals with 3 mm osteotomies were maintained for 9 weeks post-op; animals with 17 mm osteotomies were maintained for 12 weeks. The animals were stunned using a captive bolt and exsanguinated, resulting in the death of the animal from cerebral anoxia26. Additional details about these studies can be found in our recent publication that aggregated the datasets27. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines and approved by the local governmental authorities of the canton of Zurich, Switzerland and conducted according to the Swiss laws of animal protection and welfare and approved by the local governmental veterinary authorities (license numbers ZH071/17 and ZH183/17).

After sacrifice, the implant was removed, and the tibial diaphysis was excised. µCT scanning was performed with tube voltage of 68 kVp, current of 1470µA, and an isotropic resolution of 60.7 μm (XtremeCT II; Scanco Medical AG, Brüttisellen, Switzerland). Each scanned bone segment, on average, consisted of 2481 axial images. These images were subsequently downsampled for easier processing and to be more representative of clinical imaging protocols. To facilitate the conversion of Hounsfield Units (\(\:HU\) [HU]) to quantitative radiodensity (\(\:{\rho\:}_{QCT}\) [mgHA/cm3]), a hydroxyapatite calibration phantom (Scanco KP70 phantom; QRM) was scanned under identical imaging settings.

Postmortem torsion tests were available for experimental validation of the digital twin predictions. Mechanical tests were performed on an E10000 test frame (Instron; Norwood, Massachusetts, USA). Samples were potted in Beracryl and mounted in a custom test fixture that rigidly fixed the distal end and rotated the proximal end. An axial preload of 5 N was applied, then an internal rotation at 5°/min to failure. A linear regression of the torque versus angle curve from 6 to 10 N-m was used to compute torsional stiffness (S). Experimental torsional rigidity (GJ [N-m2/°]) was computed by multiplying stiffness by the specimen gauge length. A representative torque-angle curve has been provided in Supplementary Appendix A.

Digital twin creation

Finite element models for virtual torsion tests were created using four methods: two workflows based on commercial software-assisted manual methods with tetrahedral meshing and two workflows based on our automated image processing algorithms with hexahedral meshing.

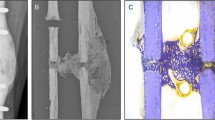

All manual (software-assisted) model creation procedures were performed in Mimics Innovation Suite (Materialise, Inc.; Leuven, Belgium). The µCT scans were first downsampled to an isotropic resolution of 400 μm. Two workflows for model creation were tested and compared. The first workflow – Manual Dual Segmentation (MDS) – is a method we previously developed and published18. The “dual segmentation” designation refers to the first step of segmentation in which preliminary masking is performed separately for callus (400–2500 HU) and cortical bone (2500–4000 HU), then the two zones are united in a Boolean operation to create one object. The second workflow – Manual Single Segmentation (MSS) – is a simpler approach in which the full radiodensity range (400–4000 HU) is captured in a single masking step25. The major distinction between the MDS and MSS methods is that MSS creates a surface layer of partial volumes on cortical bone surfaces that must be managed carefully at the material assignment stage to avoid over-prediction of bone mechanical properties20. A comparison of the MDS and MSS methods is illustrated in Fig. 2. Detailed step-by-step procedures for completing both workflows through the Mimics graphical user interface are documented in Supplementary Appendices B and C.

Comparison of the two manual segmentation methods: (a) Manual Single Segmentation (MSS) applies a single mask to create the bone object, resulting in a surface layer of partial-volume voxels (red dots) at cortical bone boundaries that require careful handling during material assignment. According to Inglis et al.20, using a dual-zone material model corrects the partial volume artifacts in cortical bone. (b) Manual Dual Segmentation (MDS) is a multi-step reconstruction with two masks, resulting in a separation of cortical bone without partial-volume surface effects.

Model geometries were adaptively meshed using linear tetrahedral (Tet4) or quadratic tetrahedral (Tet10) elements in 3-matic (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium). Our older method for the MDS workflow18 used 3-matic v.13.0, which only had the capability to generate Tet4 meshes. We previously performed a mesh independence study with this workflow and selected a maximum surface element edge length of 0.4 mm and maximum volumetric edge length of 0.875 mm18. Our newer method for the MSS workflow used 3-matic v.15.0, which introduced the capability to generate Tet10 meshes. We performed a mesh independence study with this workflow and selected a maximum element edge length of 1 mm for surfaces and volumes25. For both workflows, mesh convergence was documented based on achieving a difference less than 1% in the predicted virtual torsional rigidity (VTR) of the bone. Critically, the published MDS and MSS workflows have differences in segmentation procedures, mesh discretization, and element order (linear versus quadratic). Therefore, we have included an assessment of element order effects alone as a separate analysis in Supplementary Appendix D.

Our automated model creation procedures included two image processing algorithms, the Contour-Free Technique (CFT) and Snake-Reliant Technique (SRT), both of which were written in Python and are available to download at https://github.com/Dailey-Lab. The detailed development of these algorithms has been recently published27. Briefly, both techniques crop the raw µCT image and downsample it for greater efficiency due to the high resolution of the raw images. The downsampling procedure aggregated raw voxels into cubic finite elements, so the element size was controlled by the number of voxels encompassed by the element and the raw voxel resolution. Our previous mesh convergence analysis revealed that aggregating five elements (element size 303.5 μm) produced a converged solution27. The main difference between the CFT and SRT algorithms was in the approach used to isolate the bone object from the image background. Thresholding, floodfilling, and removal of improperly connected voxels were common between CFT and SRT. However, SRT imposed an additional geometrical constraint on bone segmentation at the outer boundary to promote smoothness.

Previously, we compared the performance of the contour-free and snake-reliant techniques and concluded that both are equally reliable with respect to physical validation test data, but CFT is faster overall, considering the computational costs of both model creation and solution. However, the models produced by the two techniques are different, with SRT being more analogous to the MDS manual technique and CFT being more analogous to the MSS manual technique. Therefore, data comparing both automated methods (CFT and SRT) to both manual methods (MDS and MSS) are included in this paper, with CFT in the main results and SRT in Supplementary Appendices E/F.

Material assignment

In all models, regardless of which manual or automated workflow was used, material properties were assigned to each element using an elementwise, density-based approach. First, the Hounsfield Units (\(\:HU\)) were calculated based on the pixel gray values (\(\:v\)) using a linear conversion provided in metadata of the µCT scans:

Hounsfield Units were then converted to bone mineral density (\(\:{\rho\:}_{\text{Q}\text{C}\text{T}}\)) using a linear conversion obtained from the phantom calibration:

Finally, because both contralateral cortical bones and operated bones with callus were evaluated in this study, we compared two previously published material assignment laws to calculate Young’s modulus: (1) a single-zone material law validated for ovine cortical bone18, and (2) a dual-zone material assignment law validated for ovine cortical bone and callus19. Both the single-zone and dual-zone material models can be represented as follows:

where \(\:E\) is in [MPa] and the cutoff threshold for soft versus hard tissue is \(\:{\rho\:}_{\text{c}\text{u}\text{t}}\) = 0 in the single-zone material model and \(\:{\rho\:}_{\text{c}\text{u}\text{t}}\) = 665 mgHA/cm3 for the dual-zone material model. This cutoff threshold was previously found to effectively distinguish between hard and soft callus in healing ovine tibiae19. Including a cutoff threshold also helps compensate for partial volume artifacts on the surfaces of cortical bones20.

Finite element analysis

Models created using manual workflows (MDS and MSS) were solved in Ansys (2020 R2; Ansys, Inc., Canonsburg, PA, USA). Models created using the automated workflows (CFT and SRT) were solved in Abaqus (2023; Dassault Systèmes, Waltham, MA, USA). Ansys simulations were set up manually through the graphical user interface of Ansys Workbench. Abaqus simulations were set up using the integrated Python scripting interface. For both solvers, the nodal positions, the nodal connectivity matrix, and material properties of elements were extracted and stored as input files compatible to each software. The output of each simulation was virtual torsional rigidity (VTR [\(\:\text{N}{\text{m}}^{2}/^\circ\:\)]):

where \(\:M\) is the computed moment reaction, L is the bone working length, and \(\:\varphi\:\) is the applied angle of twist.

The two solvers had slight differences in the workflow for applying boundary conditions for a virtual torsion test to calculate VTR. In Ansys, twisting about the long axis of the bone was achieved through remote points that were defined at the centroids of the distal and proximal faces of the bone. Nodes on each scoped end face were rigidly coupled to the corresponding remote points. The distal remote point was fully constrained in all degrees of freedom. The proximal remote point had a 1° twist about the longitudinal (z) axis, with zero displacements in the transverse plane (x and y directions). The moment reaction (M) was queried at the fixed distal surface. In Abaqus, the coordinates of the centers of the proximal bone end (\(\:{\mathbf{c}}_{\text{p}\text{r}\text{o}\text{x}}\)) and distal bone end (\(\:{\mathbf{c}}_{\text{d}\text{i}\text{s}}\)) were calculated as the average of the nodal positions on those surfaces. All nodes on the proximal surface were kinematically coupled to a reference point positioned at \(\:{\mathbf{c}}_{\text{p}\text{r}\text{o}\text{x}}\) in all degrees of freedom. The proximal reference point was twisted by \(\:\varphi\:\) = 1° and the distal end nodes were constrained at all degrees of freedom. From the solved model, the distal end nodal positions (\(\:{\mathbf{p}}_{\text{x}}\), \(\:{\mathbf{p}}_{\text{y}}\)) with respect to the center (\(\:{\mathbf{c}}_{\text{d}\text{i}\text{s}\text{t}}\)) along with the nodal reaction forces (\(\:{\mathbf{F}}_{\text{x}}\), \(\:{\mathbf{F}}_{\text{y}}\)) were extracted. These values were then used to calculate the moment reaction (\(\:M\)):

To establish finite element solver independence and verify equivalence of the torsion boundary conditions in Ansys and Abaqus, a verification analysis was performed. Virtual torsions tests were carried out in both Ansys and Abaqus for one complete set of models created using the automatic CFT workflow. Results of this verification are presented in Supplementary Appendix G.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed in R (version 4.4.1)28 and Python (version 3.11.5). All analyses assumed a significance level of α = 0.05. Data normality of the torsional rigidities and their pairwise differences (error metrics between methods) was evaluated using Shapiro-Wilk tests. Due to the presence of some normality violations, summary descriptive statistics were reported as median and interquartile range (IQR), and all inferential procedures used non-parametric tests.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (\(\:{r}_{s}\)) was used to evaluate the strength of the monotonic association between sets of virtual torsional rigidity (VTR) measures. VTRs obtained from the manual and automatic model-creation methods (MSS/MDS/CFT/SRT) were compared with each other and with the ex vivo torsional rigidity measured in postmortem biomechanical testing (GJ). Correlation strength was qualitatively interpreted based on established standard guidelines29. Due to the presence of some normality violations, agreement between measures was evaluated using the mean absolute error (MAE) instead of root mean square error (RMSE)30,31.

Bland-Altman analyses32,33 were also carried out to mutually compare agreement between sets of measures by calculating the difference (\(\:\delta\:\)) for the average (\(\:\mu\:\)) of each pair of measurements, which gives insight about the variation of agreement over the entire range of measurements. The lower and upper limits of the agreement between each two measurement methods were calculated as the 5th and the 95th percentiles. The bias (\(\:{b}_{\delta\:}\)) was defined as the median of the differences between the two measurements. The range of differences (\(\:{r}_{\delta\:}\)) for each pair of measurement methods was calculated as the difference between the limits of agreement.

A Friedman test was used to compare the torsional rigidity produced by the four virtual test methods (MSS/MDS/CFT/SRT) to experimental torsional rigidity (GJ) for the contralateral and operated limbs with both material models. Prior to analysis, the normality of the residuals for each level of the within-subject factor was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and the assumption of sphericity was examined with Mauchly’s test. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons between methods were performed using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. The Holm correction was applied to adjust for multiple comparisons. Differences in torsional rigidity between contralateral and operated bones are expected clinically and are not the focus of this investigation, so no statistics for those comparisons were reported.

For the manual workflows, inter-operator reliability between two different trained operators was assessed using a two-way random effects ICC with absolute agreement (ICC(2,1)) following the methodology described in34,35,36. The reliability of the average of both operators’ measurements was also estimated using ICC(2,2) and to evaluate precision, 95% confidence intervals were computed. This analysis was performed on a subset of data (N = 18) from a single previously published animal experiment.

Results

Virtual torsion tests were carried out for all digital twins in the database (\(\:N\) = 59 contralateral and operated bones) including models made by both manual workflows and both automatic workflows. Summary descriptive statistics for VTR in all simulation groups are provided in Table 1.

Correlations between predicted VTR values were very strong when comparing the two manual workflows (MSS vs. MDS) and the two automated workflows (CFT vs. SRT) for both the single-zone and dual-zone material models (Fig. 3). Spearman’s correlations included data for contralateral and operated bones combined and all were strongly significant (p < 0.001) with \(\:{r}_{s}\) ≥ 0.982 and low mean absolute error (MAE ≤ 0.056).

Correlations between virtual torsional rigidity (VTR) values obtained by the two manual workflows (MSS vs. MDS) and the two automated workflows (CFT vs. SRT) for contralateral and operated bones using both material models: (a) single-zone material model validated for ovine cortical bone18 and (b) dual-zone validated for cortical bone and callus19. (OP: operated, CO: contralateral, MSS: Manual Single Segmentation, MDS: Manual Dual Segmentation, CFT: Contour-Free Technique, SRT: Snake-Reliant Technique, MAE: Mean Absolute Error)

Correlations between predicted VTR values from the manual and automated model-building workflows were also very strong (Fig. 4). Due to the extremely good agreement between the two automated workflows (CFT and SRT), only results from the computationally faster CFT are compared to the manual results in the main figures; SRT results are provided in Supplementary Appendix E. All Spearman’s correlations were strongly significant (p < 0.001) with \(\:{r}_{s}\) ≥ 0.921 and low mean absolute error (MAE ≤ 0.087). The companion Bland-Altman analysis (Fig. 5) showed that for all workflow comparisons, the range of difference values (variability of the agreement) between simulation methods was lower when using the single-zone material model (\(\:{r}_{\delta\:}\) ≤ 0.12) versus the dual-zone material model (\(\:{r}_{\delta\:}\) ≤ 0.23). Absolute bias between methods was low for both the single-zone material model (\(\:{b}_{\delta\:}\) ≤ 0.02) and the dual-zone material model (\(\:{b}_{\delta\:}\) ≤ 0.06).

Correlations between virtual torsional rigidity (VTR) values obtained by the CFT automated workflow and the two manual workflows (MDS and MSS) for contralateral and operated bones using both material models: (a) single-zone and (b) dual-zone. (OP: operated, CO: contralateral MSS: Manual Single Segmentation, MDS: Manual Dual Segmentation, CFT: Contour-Free Technique, SRT: Snake-Reliant Technique, MAE: Mean Absolute Error).

Companion to Fig. 4: Bland-Altman analysis of mutual agreement between VTR values from automated CFT and manual MDS and MSS workflows. (OP: operated, CO: contralateral, per.: percentile, MSS: Manual Single Segmentation, MDS: Manual Dual Segmentation, CFT: Contour-Free Technique, SRT: Snake-Reliant Technique, VTR: Virtual Torsional Rigidity)

All workflows for virtual mechanical testing were also compared to the experimental ground truth for ex vivo torsional rigidity. Correlation analyses are shown in Fig. 6 and accompanying Bland-Altman plots are shown in Fig. 7. Data for CFT is presented in the main figures; SRT results for experimental validation are provided in Supplementary Appendix F. All correlations between virtual and physical mechanical tests were statistically significant (p < 0.001) and moderately strong to strong, but they were lower in strength with higher errors compared to correlations between VTR values produced by different simulation workflows (Figs. 4 and 5). For all simulations workflows, the dual-zone material model produced better agreement between virtual and physical tests compared to the single-zone model, as indicated by lower errors and less bias. With the dual-zone material model, all manual and automated workflows demonstrated similar levels of agreement with the experimental GJ data.

The four tested methods for model preparation were also compared to each other in terms of overall efficiency, considering both model preparation time and FE solution time. Detailed time breakdowns are provided in Supplementary Appendix H. The fastest method tested was the automated contour-free technique (CFT), which took an average of 9.4 min per model to process the images, create the FE model, and solve the model. The faster of the two manual methods was MSS, which took an average of 27 min per model to process, create, and solve.

Correlations between virtual torsional rigidity (VTR) values obtained by the automated (CFT) and manual (MDS/MSS) workflows with experimental torsional rigidity (GJ) for (a) single-zone and (b) dual-zone material model. The EXP vs. CFT panel in (b) is adapted from Ariyanfar et al.27. (OP: operated, CO: contralateral, EXP: experiment, MSS: Manual Single Segmentation, MDS: Manual Dual Segmentation, CFT: Contour-Free Technique, MAE: Mean Absolute Error)

Companion to Fig. 6: Bland-Altman analysis of agreement between computational and experimental torsional rigidity values. (OP: operated, CO: contralateral, EXP: experiment, per.: percentile, MSS: Manual Single Segmentation, MDS: Manual Dual Segmentation, CFT: Contour-Free Technique, VTR: Virtual Torsional Rigidity)

Boxplots showing between-groups comparisons of the four virtual test methods and experiments are given in Fig. 8. For the contralateral bones, both the single-zone and dual-zone material models produced accurate representations of torsional rigidity. The Shapiro–Wilk tests on the residual were significant (p < 0.05) in both material models, indicating that the residuals deviated from normality. Mauchly’s test indicated that the assumption of sphericity was violated for the within-subject factor for both material models (\(\:W\le\:0.00026,\:p<0.001\)). Given these findings, all subsequent analyses used non-parametric methods. The Friedman test revealed significant effects of torsional rigidity assessment methods for both material models (\(\:{\chi\:}^{2}\left(4\right)=26.38,\:p<0.001\) for single-zone; \(\:{\chi\:}^{2}\left(4\right)=42.80,\:p<0.001\) for dual-zone). Holm-adjusted Wilcoxon post-hoc tests showed no significant differences between any of the simulation methods and the experiments (EXP). Some of the pairwise comparisons between simulation methods were significant (see Fig. 8) despite the mean differences being small (≤ 0.057 for single-zone; ≤ 0.111 for dual-zone). The corresponding rank-biserial effect sizes were mostly small to moderate, indicating minimal practical impact.

In contrast, for the operated bones, the choice of material model did matter. The residual normality checks again indicated non-normal distributions in all cases (p < 0.05). Based on Mauchly’s test results, in both single-zone and dual-zone material models, the assumption of sphericity was violated for the within-subject factor (\(\:W<0.001,\:p<0.001\)). The Friedman tests showed significant effects of torsional rigidity assessment method for both material models (\(\:{\chi\:}^{2}\left(4\right)=112.6,\:p<0.001\) for single-zone; \(\:{\chi\:}^{2}\left(4\right)=33.4,\:p<0.001\) for dual-zone). With the single-zone material model, post-hoc Wilcoxon tests with Holm corrections revealed that the experimental values (EXP) significantly differed from the four virtual simulation methods (adjusted \(\:p\:<\:0.001\); mean differences ≥ 0.357) with large effect sizes (r ≥ 0.715). Some pairwise comparisons between the four simulation methods (CFT, SRT, MDS, MSS) were also statistically significant, but again the mean differences were all small (≤ 0.074) compared to the differences to the experiments. For operated bones with the dual-zone material model, the overall Friedman test was also significant, but none of the pairwise comparisons with experiments (EXP) reached significance. Some pairwise comparisons between simulation methods were significant after Holm correction, but as with the single-zone material model, the mean differences were all small (≤ 0.089), and effect sized ranged from small to moderate.

The ICC analysis for inter-operator comparison demonstrated excellent agreement between the two operators. For single measurements, the ICC(2,1) was 0.95 (95% CI: 0.88–0.98; p < 0.001). When the average of the two operators’ measurements was considered, reliability increased to ICC(2,2) = 0.98 (95% CI: 0.94–0.99).

Boxplots comparing model-predicted torsional rigidity from all four model-building workflows to experimental torsional rigidity for contralateral and operated bones using both material models: (a) single-zone and (b) dual-zone. (MSS: Manual Single Segmentation, MDS: Manual Dual Segmentation, CFT: Contour-Free Technique, STR: Snake-Reliant Technique, EXP: experiment)

Discussion

The novelty of this study is in the comprehensive comparison of several variations for manual and automated techniques for virtual mechanical testing of contralateral and operated bones, and the demonstration that all steps of digital twin preparation can be completely automated. The two manual workflows were both previously published as general methods, but they each have important distinctions, so we have added step-by-step procedures in the Supplemental Digital Content to enable others to implement the same methods precisely. Both manual methods are dependent upon the availability of software licenses for image processing in Mimics, and on the ability of a trained user to follow the protocol for the manual operations. These limitations of software availability, manual slowness, and user training requirements motivated us to develop the automated model creation workflows using our own open-source codes27. In this work, we extended the automation to include setting up and running simulations in Abaqus using its Application Programming Interface (API), which we had not explored previously. The manual and automated techniques were mutually compared to each other for the first time in this study.

The comparisons between methods revealed that minor variations in model creation and setup had relatively small effects on the calculated rigidities of the bones. Specifically, the virtual torsional rigidity (VTR) predicted by all four computational workflows tested (MDS, MSS, CFT, and SRT) had similar agreement to experimental ground truth. In fact, all error and agreement metrics were lower for the comparisons between the four model-building workflows than for the comparisons between virtual tests and experiments. For the contralateral bones, none of the workflows differed significantly from the experimental torsional rigidity values under either the single-zone or dual-zone material models, indicating consistent agreement between models and experiments across all methods. For the operated bones, however, the results depended on the material model. With the single-zone material model, all workflows significantly overestimated torsional rigidity relative to the experimental measurements, despite showing only small differences among themselves. In contrast, with the dual-zone material model, none of the workflows differed significantly from the experimental values, and the mean differences were very small.

Together, these findings indicate that all four workflows show comparable performance and introduce only minor model-building variability. For operated bones, however, the agreement with experimental torsional rigidity is influenced primarily by the material model rather than the workflow itself.

The inter-operator reliability analysis demonstrated that, when performed by experienced users, manual model creation can produce consistent and reproducible results. According to established thresholds37,38, our values of ICC ≥ 0.95 represent excellent reliability, indicating minimal variability attributable to operator differences. The narrow confidence intervals further support the robustness of the measurement approach. These results suggest that differences observed between animal reflect true physiologic variations rather than measurement inconsistencies.

The results also underscored the importance of the dual-zone material model for avoiding systematic overprediction of torsional rigidity in operated limbs. The use of the dual-zone material model did augment some differences in the digital twins, as demonstrated by slightly larger limits of agreement and bias metrics in Bland-Altman analysis compared to the single-zone material model (Fig. 5). However, the dual-zone material model showed only minor variability across workflows and better agreement with experimental results, whereas the single-zone model exhibited significantly poorer correspondence with experimental validation (Fig. 8). The single-zone model exaggerated the deviation between experimental and virtual torsional rigidity in the operated bones, whereas the dual-zone model produced statistically consistent and comparable rigidity values across all methods and in both operated and contralateral specimens.

Despite notable differences in segmentation and meshing procedures, the manual and automated methods yielded VTR predictions that were closely aligned. While some pairwise comparisons were statistically significant, the corresponding mean differences and effect sizes were small, demonstrating that the workflows were in strong practical agreement despite statistically detectable differences. This was true even for the two manual workflows (MDS and MSS) that had both image segmentation and model discretization differences due to the Mimics software capabilities at the time each method was developed. The additional analysis included in Supplementary Appendix C demonstrated that element type was likely the source of the small, but significant difference between the MSS (Tet10) and MDS (Tet4) workflows with the dual-zone material model. The overall good agreement between results from all methods suggests that the decision about which approach to adopt can be based on time efficiency as a primary consideration. In that case, the recommended automated approach is CFT and the recommended manual approach is MSS.

This study has several limitations. Reliance on commercial software was not completely removed. The focus of this paper was on the procedures involved in model preparation, for which we showed that automation was viable and reliable. However, all the mechanical simulations were still carried out either in Abaqus or Ansys because these solvers are widely used in industry. Future work could explore the use of FEBio39 or other open-source software as free alternatives. In clinical translation, the image acquisition will be at lower resolution and lower dose than scans we have used here. The implication of this is that downsampling procedures would not be used on clinical scans. Furthermore, the thresholds used to segment bone and detect the ROI for analysis may need to be adjusted. Introduction of adaptive thresholding could help address these limitations. Adaptive thresholding could also assist in separating cortical bone and callus to measure callus structure and composition. Separating callus from bone is challenging because the extent of cortical bone resorption varies substantially throughout the callus40, leading to detection of false callus inside the cortical bone when a fixed threshold is used41. Our imaging was also performed ex vivo with implants removed, so no metal artifact correction algorithms were required. With manual dual segmentation, we previously documented the need to correct the callus mask to correctly split the old/new tissue boundaries when callus analysis is needed in addition to virtual mechanical testing18.

With the rapidly increasing interest in the applications of computational modeling and simulation in medicine, competing definitions for digital twins have emerged. In this study, the surrogate models from which we have generated instantaneous (single-timepoint) mechanical biomarkers served as simplified, image-based representative of the bone. Thus our use of the term digital twins is aligned with European organizations and agencies42. The definition of digital twins adopted by the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine43 emphasizes a bidirectional flow of information that can be updated based on new information. To achieve this in clinical practice, we envision that virtual mechanical test of fracture healing could be used diagnostically as feedback to guide clinical treatment, especially where serial imaging has been performed to look for healing progression in a patient at risk of nonunion. There is also potential for image-based digital twins to be used prognostically by coupling them with a mechanoregulatory model44,45 to predict the future progression of healing. These future applications would require new datasets to enable robust clinical validation.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that virtual mechanical testing of contralateral and operated long bones is a reliable surrogate for physical mechanical testing and is robust to differences in methods used to create the digital twins from imaging. The choice between any of the manual and automated techniques we have described is therefore at the discretion of the researcher, but the overall fastest approach would be to adopt automated digital twin creation.

Data availability

The raw data from which this study was derived was shared with the investigators by permission from the sponsors and is not publicly available. Computer codes for the automated digital twin creation workflows have been shared and are free to download from our lab GitHub. Detailed step-by-step instructions for the manual digital twin creation workflows have been shared in the supplementary material with this manuscript.

References

Wu, A. M. et al. Global, regional, and National burden of bone fractures in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis from the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2, e580–e592 (2021).

Hak, D. J. et al. Delayed union and nonunions: Epidemiology, clinical issues, and financial aspects. Injury 45, S3–S7 (2014).

Antonova, E., Le, T. K., Burge, R. & Mershon, J. Tibia shaft fractures: costly burden of nonunions. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 14, 42 (2013).

Zura, R. et al. Epidemiology of fracture nonunion in 18 human bones. JAMA Surg. 151, e162775 (2016).

Randomized Trial of Reamed. Unreamed intramedullary nailing of tibial shaft fractures. JBJS 90, 2567 (2008).

Fong, K. et al. Predictors of nonunion and reoperation in patients with fractures of the tibia: an observational study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 14, 103 (2013).

Metsemakers, W. J. et al. Individual risk factors for deep infection and compromised fracture healing after intramedullary nailing of tibial shaft fractures: A single centre experience of 480 patients. Injury 46, 740–745 (2015).

Massari, L. et al. Can Clinical and Surgical Parameters Be Combined to Predict How Long It Will Take a Tibia Fracture to Heal? A Prospective Multicentre Observational Study: The FRACTING Study. BioMed. Res. Inter. 1809091 (2018).

Dailey, H. L., Wu, K. A., Wu, P. S., McQueen, M. M. & Court-Brown, C. M. Tibial fracture nonunion and time to healing after reamed intramedullary nailing: risk factors based on a Single-Center review of 1003 patients. J. Orthop. Trauma. 32, e263 (2018).

Drosos, G. I., Bishay, M., Karnezis, I. A. & Alegakis, A. K. Factors affecting fracture healing after intramedullary nailing of the tibial diaphysis for closed and grade I open fractures. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 88, 227–231 (2006).

O’Halloran, K. et al. Will my tibial fracture heal? Predicting nonunion at the time of definitive fixation based on commonly available variables. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res.. 474, 1385 (2016).

Malik, M. H. A., Harwood, P., Diggle, P. & Khan, S. A. Factors affecting rates of infection and nonunion in intramedullary nailing. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br.. 86-B, 556–560 (2004).

Westgeest, J. et al. Factors associated with development of nonunion or delayed healing after an open long bone fracture: A prospective cohort study of 736 subjects. J. Orthop. Trauma. 30, 149 (2016).

Zura, R. et al. An inception cohort analysis to predict nonunion in tibia and 17 other fracture locations. Injury 48, 1194–1203 (2017).

Slobogean, G. P. Can a Tibia Shaft Nonunion Be Predicted at Initial Fixation? Applying the Nonunion Risk Determination (NURD) Score to the SPRINT Trial Database.

Dailey, H. L., Kersh, M. E., Collins, C. J. & Troy, K. L. Mechanical biomarkers in bone using Image-Based finite element analysis. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 21, 266–277 (2023).

Schwarzenberg, P., Darwiche, S., Yoon, R. S. & Dailey, H. L. Imaging modalities to assess fracture healing. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 18, 169–179 (2020).

Schwarzenberg, P. et al. Virtual mechanical tests out-perform morphometric measures for assessment of mechanical stability of fracture healing in vivo. J. Orthop. Res. 39, 727–738 (2021).

Inglis, B. et al. Biomechanical duality of fracture healing captured using virtual mechanical testing and validated in ovine bones. Sci. Rep. 12, 2492 (2022).

Inglis, B., Grumbles, D. & Dailey, H. L. Dual-zone material assignment method for correcting partial volume effects in image-based bone models. Comput. Methods Biomech. BioMed. Eng. 26, 1431–1442 (2023).

Schwarzenberg, P., Maher, M. M., Harty, J. A. & Dailey, H. L. Virtual structural analysis of tibial fracture healing from low-dose clinical CT scans. J. Biomech. 83, 49–56 (2019).

Dailey, H. L. et al. Virtual Mechanical Testing Based on Low-Dose Computed Tomography Scans for Tibial Fracture: A Pilot Study of Prediction of Time to Union and Comparison with Subjective Outcomes Scoring. JBJS 101, 1193 (2019).

Schwarzenberg, P., Mccarthy, A., Harty, J. A. & Dailey, H. L. and and Clinical application of virtual mechanical testing measures slow fracture healing in patients with comorbidities. (2021).

Dailey, H. L. et al. Pilot study of micromotion nailing for mechanical stimulation of tibial fracture healing. Bone Joint Open. 2, 825–833 (2021).

Bahrami, M., Frew, K., Hughes, J. & Dailey, H. L. Reliable and streamlined model setup for digital twin assessment of fracture healing. J. Biomech. 180, 112492 (2025).

Darwiche, S. E. et al. Combined electric and magnetic field therapy for bone repair and regeneration: an investigation in a 3-mm and an augmented 17-mm tibia osteotomy model in sheep. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 18, 454 (2023).

Ariyanfar, A. et al. Fast automated creation of digital twins for virtual mechanical testing of ovine fractured tibiae. Comput. Biol. Med. 192, 110268 (2025).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (2024).

Schober, P., Boer, C. & Schwarte, L. A. Correlation coefficients: appropriate use and interpretation. Anesth. Analgesia. 126, 1763 (2018).

Chai, T. & Draxler, R. R. Root mean square error (RMSE) or mean absolute error (MAE)? – Arguments against avoiding RMSE in the literature. Geosci. Model Dev. 7, 1247–1250 (2014).

Hodson, T. O. Root-mean-square error (RMSE) or mean absolute error (MAE): when to use them or not. Geosci. Model Dev. 15, 5481–5487 (2022).

Measuring agreement in method comparison studies - J Martin Bland, Douglas, G. & Altman https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/096228029900800204 (1999).

Giavarina, D. Understanding Bland Altman analysis. Biochem. Med. 25, 141–151 (2015).

Koo, T. K. & Li, M. Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J. Chiropr. Med. 15, 155–163 (2016).

Shrout, P. E. & Fleiss, J. L. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol. Bull. 86, 420–428 (1979).

McGraw, K. O. & Wong, S. P. Forming inferences about some intraclass correlation coefficients. Psychol. Methods. 1, 30–46 (1996).

Mondal, D., Vanbelle, S., Cassese, A. & Candel, M. J. Review of sample size determination methods for the intraclass correlation coefficient in the one-way analysis of variance model. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 33, 532–553 (2024).

Walter, S. D., Eliasziw, M. & Donner, A. Sample size and optimal designs for reliability studies. Stat. Med. 17, 101–110 (1998).

Maas, S. A., Ellis, B. J., Ateshian, G. A. & Weiss, J. A. FEBio: finite elements for biomechanics. J. Biomech. Eng. 134, 011005 (2012).

Ren, T., Klein, K., von Rechenberg, B., Darwiche, S. & Dailey, H. L. Image-based radiodensity profilometry measures early remodeling at the bone-callus interface in sheep. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 21, 615–626 (2022).

Ariyanfar, A. & Dailey, H. L. Klein,Karina, von Rechenberg, Brigitte, Darwiche, Salimand Adaptive image segmentation reveals substantial cortical bone remodelling during early fracture repair. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. Imagi. Vis. 12, 2345165 (2024).

Viceconti, M., De Vos, M., Mellone, S. & Geris, L. Position paper from the digital twins in healthcare to the virtual human twin: A Moon-Shot project for digital health research. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 28, 491–501 (2024).

Foundational Research Gaps and Future Directions for Digital Twins. (National Academies, Washington, D.C., https://doi.org/10.17226/26894 (2024).

Ren, T. & Dailey, H. L. Mechanoregulation modeling of bone healing in realistic fracture geometries. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 19, 2307–2322 (2020).

Schwarzenberg, P. et al. Domain-independent simulation of physiologically relevant callus shape in mechanoregulated models of fracture healing. J. Biomech. 118, 110300 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Beat Lechmann (Johnson & Johnson Family of Companies) and Stefano Brianza (Biomech Innovations AG) for agreeing to grant access to the ovine studies data for our analyses.

Funding

This material is based in part upon work supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) under Grant No. CMMI-1943287. The preclinical studies from which this data was obtained were funded by the Johnson & Johnson Family of Companies and Biomech Innovations. Portions of this research were conducted on Lehigh University’s Research Computing infrastructure partially supported by NSF Award 2019035. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding sources including the National Science Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MB carried out all manual workflows; AA carried out all automated workflows. MB and AA jointly performed statistical analysis, visualization, figure creation, and writing (equal contribution). KK, BvR, and SD were responsible for all animal procedures, husbandry, and analysis/curation of data arising therefrom. HLD conceptualized and supervised the project, acquired funding, and co-wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bahrami, M., Ariyanfar, A., Klein, K. et al. Automated and manual model creation workflows are equally reliable for virtual mechanical testing of ovine bone and fracture healing. Sci Rep 15, 45050 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32307-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32307-0