Abstract

Reliable identification of agricultural pests and beneficial insects is crucial for sustainable crop protection and ecological balance, yet most vision-based models remain black boxes and require high-dimensional features. This paper proposes an explainable hybrid insect-classification framework that combines convolutional neural network (CNN) feature extraction with a dual–XAI feature selection strategy. SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) and Permutation Feature Importance (PFI) are applied in parallel to rank handcrafted and CNN-derived features, and their intersection yields a compact, biologically meaningful subset for final classification. The selected features are evaluated using lightweight classifiers and a hybrid ensemble, enabling accurate inference under field variability. Experiments on a curated, balanced dataset of four classes (Colorado potato beetle, green peach aphid, seven-spot ladybird, and healthy leaves) collected under diverse lighting and background conditions achieve 96.7% overall accuracy, with precision, recall, and F1-scores all above 96%. Importantly, performance remains stable when reducing dimensionality, retaining \(\ge\)90% accuracy using only the top 11 hybrid-selected features. These results demonstrate that integrating SHAP and PFI improves both robustness and interpretability, supporting practical deployment for automated pest monitoring and precision agriculture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Accurate and timely identification of insect pests and beneficial insects plays a vital role in integrated pest management (IPM) and sustainable agriculture. Insect pests, if not immediately identified and controlled, can have devastating impacts on crop yields and food security 1,2. In contrast, beneficial insects such as pollinators and natural predators contribute significantly to ecosystem balance and crop productivity. Misclassification or late detection can result in misuse of agrochemicals, increased production costs, ecological imbalance, and decreased agricultural production 3,4. The Timely and accurate identification of insect pests and beneficial species is critical to implementing effective Integrated Pest Management (IPM) strategies in sustainable agriculture 1,5. Incorrect identification can result in either excessive pesticide application, harming pollinators and natural predators, or insufficient pest control, leading to severe crop losses. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization 6,7, global economic losses due to plant pests and diseases exceed $220 billion annually, with insect pests alone accounting for more than 31.8% of this figure. Among the most damaging insect pests in arable crops are the Colorado potato beetle CPB, (Leptinotarsa decemlineata) and the green peach aphid Myzus persicae. CPB larvae are known to completely defoliate potato plants, potentially reducing yields by more than 50% if not effectively managed8,9. Moreover, aphids such as M. persicae are efficient vectors of viral diseases like Potato Virus Y (PVY), with annual economic losses in Europe alone estimated at over €180 million10,11.

Traditionally, pest monitoring has relied on manual scouting and expert identification, followed by widespread use of synthetic pesticides. Although still common practice, this approach is not only labor-intensive and time-consuming but also contributes significantly to environmental degradation, pesticide resistance, and non-target species decline1,12. There is therefore a growing need for automated, intelligent detection systems capable of distinguishing between pest and beneficial insects efficiently and accurately. Recent developments in computer vision, sensor technologies, and machine learning (ML) have enabled the design of automated insect detection systems. Early systems relied on basic image processing methods–such as thresholding, morphological operations, and edge detection–to isolate and classify insect features13,14. For instance,1 introduced a multifractal-based segmentation technique for whiteflies, and9,15 employed Mahalanobis distance-based classification for pests on sticky traps. However, these methods are often unreliable under field conditions due to varying lighting, cluttered backgrounds, and occlusions, which limit their robustness and scalability4,16. Recent advancements in computer vision have significantly enhanced the ability to detect and classify insects in agricultural settings. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and deep learning architectures have demonstrated high accuracy in identifying and localizing insect pests across diverse crop types17,18. For instance, transformer-based models have shown superior performance in segmenting small insect regions within complex backgrounds2,19. Hybrid models combining CNNs with attention mechanisms, such as Vision Transformers (ViTs), have further improved classification accuracy and robustness20. Moreover, domain adaptation techniques have been successfully applied to bridge the gap between laboratory-controlled and real-world field images15. Researchers have also explored multi-modal fusion, integrating RGB and hyperspectral images to boost insect detection performance under varying environmental conditions21. Despite these advancements, challenges persist in segmenting small and occluded insects, motivating the exploration of ensemble and hybrid models that combine multiple feature types and classifiers6. These studies collectively highlight the growing promise of computer vision-based insect detection as a critical tool for precision pest management in sustainable agriculture.

Image processing forms the foundational stage in deep learning workflows, playing a crucial role in extracting informative visual features for downstream tasks such as object detection and classification. Recent advances in computer vision, including transformer-based architectures2,20, have further highlighted the importance of robust preprocessing techniques in ensuring that deep models can effectively learn representations from diverse and complex visual inputs. As agricultural and ecological datasets often present high variability in background, lighting, and object scales, effective image processing ensures the reliability of learned features across different conditions17. Typical preprocessing steps in deep learning pipelines include resizing images to standard dimensions, normalization to maintain consistent intensity ranges, and data augmentation to improve generalization18,22. Techniques such as histogram equalization and adaptive thresholding enhance contrast, while color space transformations (e.g., RGB to HSV) enable models to leverage color information for more accurate segmentation. For insect detection, these preprocessing steps ensure that small, low-contrast insect bodies are visible and distinguishable against complex plant backgrounds. Effective image processing directly impacts the semantic segmentation accuracy of deep learning models, particularly when dealing with small or occluded insect objects6. Models trained on preprocessed images achieve significantly higher precision and recall, as preprocessing reduces noise and highlights relevant regions of interest. Moreover, data augmentation techniques such as rotations, translations, and brightness adjustments expand the effective dataset size, helping the model to generalize better and avoid overfitting to specific capture conditions21. Given the complexity of real-world agricultural environments, dataset-specific preprocessing strategies are essential to maximize performance in deployment scenarios20. Factors such as varying illumination, crop type differences, and natural occlusions necessitate tailored preprocessing pipelines that adapt to the specific challenges of each dataset. Future work in insect detection should focus on robust preprocessing methods that consider these variations, bridging the gap between laboratory-controlled datasets and dynamic field conditions2. Such efforts are key to developing scalable, reliable pest-detection systems for precision agriculture.

To improve robustness, traditional ML techniques have been widely applied in pest detection systems. These models generally use manually extracted features such as shape descriptors, color histograms, texture (e.g., GLCM), and Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG) to represent the visual properties of insects. Algorithms such as Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forest (RF), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), and Naïve Bayes (NB) have demonstrated competitive performance, particularly in resource-constrained environments where lightweight computation is necessary4. For example,8 reported over 86% accuracy in aphid detection using HOG features with SVM, while5 achieved more than 91% accuracy using various classical ML classifiers trained on shape features. However, these classical approaches face challenges due to the presence of high-dimensional and often redundant features. Including irrelevant features can increase computational load, slow down model inference, and impair generalization performance23,24. Additionally, no universal feature set exists that performs optimally across all insect categories and conditions. Thus, effective feature selection is essential for maximizing classification accuracy while minimizing complexity and resource use. Although deep learning–particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs)–has become dominant in image classification tasks due to its ability to automatically learn features, such models require extensive labeled data and computational resources25. Their deployment on low-cost edge devices remains limited, especially in agricultural contexts with constrained infrastructure14,26. As a result, further exploration of classical ML models augmented by intelligent feature selection is warranted. Recent advancements in machine learning (ML) have significantly improved the detection and classification of insect species compared to traditional thresholding and rule-based image analysis methods15,27. Classical ML models, such as support vector machines (SVMs) and artificial neural networks (ANNs), have leveraged handcrafted features–such as shape descriptors, texture features, and color histograms–to distinguish insect classes in agricultural images18. For example, studies using SVM models with histogram of oriented gradients (HOG) and morphological descriptors have achieved classification accuracies above 85% for species like the Colorado potato beetle and green peach aphid21. More advanced ML strategies employ ensemble models and multi-layer classifiers, which integrate multiple base classifiers to enhance accuracy and robustness28. While these approaches rely heavily on precise feature extraction and preprocessing, deep learning models have shifted the focus toward automated feature learning from raw pixel data. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs), in particular, outperform classical methods by simultaneously learning both region-of-interest (ROI) segmentation and classification tasks29. This profound learning transition offers promising avenues for real-time pest monitoring in precision agriculture.

Insect classification plays a pivotal role in sustainable agriculture, particularly in monitoring harmful pests such as the Colorado Potato Beetle (CPB) and aphids, and preserving beneficial species like ladybirds 21,30. Effective identification of these species is crucial for integrated pest management (IPM) strategies and reducing overreliance on pesticides 2. Although machine learning (ML) techniques have been increasingly employed for insect detection 1,4, most existing approaches suffer from two key limitations: (1) reliance on high-dimensional, non-informative features, and (2) the use of black-box models lacking interpretability 5,12, which impedes trust and real-world deployment. To address these challenges, we propose a novel hybrid feature selection strategy that leverages the strengths of two explainable AI (XAI) tools–SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) 31,32 and Permutation Feature Importance (PFI) 4. Our approach systematically identifies the most relevant and non-redundant features, enhancing both classification performance and interpretability. The selected feature subsets are evaluated using classical ML classifiers such as Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forests (RF), k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), and Naïve Bayes (NB), enabling low-latency inference suitable for resource-constrained field conditions 15. This work contributes not only a new hybrid-XAI methodology but also a practical solution toward deployable smart agricultural monitoring systems. To our knowledge, no prior work has fused SHAP and PFI for agricultural insect detection, nor has such an approach been assessed for its trade-offs in accuracy and efficiency on edge devices 23,33.

Research gap: Recent studies have achieved notable progress in agricultural insect recognition through (i) classical ML pipelines that combine handcrafted features (HOG, texture, color, shape) with lightweight classifiers, and (ii) deep CNN/transformer-based models that deliver high accuracy on controlled or benchmark datasets1,2,5. A few works have also begun to use XAI tools such as SHAP or LIME to provide post-hoc visual explanations of trained models31,32. Nevertheless, several critical challenges remain insufficiently addressed. First, most existing systems emphasize predictive accuracy while relying on high-dimensional or redundant feature spaces, and they rarely justify why particular features are selected; this limits transparency, increases computational cost, and weakens generalization under field variability. Second, robustness across real-world conditions–such as changing illumination, cluttered multi-crop backgrounds, partial occlusions, and camera-device diversity–remains a major bottleneck, particularly for models trained on narrow or laboratory-biased datasets4,13,33. Third, the literature is heavily skewed toward pest-only detection, with limited attention to beneficial insects and multi-species ecological interactions, which are essential for sustainable IPM and avoiding unintended harm to pollinators or predators8,34. Fourth, while XAI is increasingly used for interpretation, it is seldom integrated into the feature selection stage; to the best of our knowledge, no prior insect-classification work has fused complementary explainability tools (e.g., SHAP and PFI) into a hybrid, high-confidence selection mechanism, leaving the synergistic potential of dual-XAI selection unexplored. Finally, the field still lacks compact, interpretable, and edge-ready models that can maintain stable accuracy with minimal features and low latency on resource-constrained hardware. Collectively, these gaps underscore the need for robust, explainable, and computationally efficient insect classification frameworks that can identify both harmful and beneficial species across diverse field conditions.

Research objectives:This study aims to develop and evaluate a hybrid feature selection strategy that leverages two prominent explainable AI (XAI) tools–Permutation Feature Importance (PFI) and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP)–to identify the most relevant and non-redundant features for effective insect classification. The objective is to enhance the interpretability and performance of classical machine learning classifiers, such as Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forests (RF), k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), and Naïve Bayes (NB), particularly in distinguishing between harmful insects (e.g., Colorado potato beetles and aphids) and beneficial species (e.g., ladybirds). By systematically evaluating different feature subsets, this research investigates the impact of XAI-guided selection on classification accuracy and computational efficiency. Furthermore, the study aims to design a lightweight and efficient detection system suitable for deployment on low-cost hardware in real-world agricultural environments.

Research contributions:The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

-

1.

We introduce a dual-XAI hybrid feature selection strategy that integrates SHAP and Permutation Feature Importance (PFI) in parallel and selects features via their intersection, yielding a compact and highly reliable subset. To the best of our knowledge, this SHAP+PFI fusion has not been previously explored for agricultural insect classification.

-

2.

We demonstrate that the proposed dual-XAI selection improves both accuracy and stability under aggressive dimensionality reduction, retaining \(\ge 90\%\) accuracy using only the top-11 features, thereby validating robustness beyond conventional single-method selection.

-

3.

We benchmark the hybrid-XAI pipeline against standard filter, wrapper, and embedded methods across four lightweight classifiers (SVM, RF, KNN, NB) and a hybrid ensemble, providing a comprehensive trade-off analysis between interpretability, performance, and computational cost.

-

4.

We validate the framework on a real farm dataset containing both harmful pests (CPB, aphids) and a beneficial insect (ladybird), collected under diverse field lighting and background conditions, addressing a key realism gap in prior studies.

-

5.

We provide feature-level explanations aligned with entomological traits, enabling transparent decision support suitable for low-cost edge deployment in precision agriculture and integrated pest management.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews relevant literature on insect detection, machine learning, and feature selection. Section 3 describes the dataset, feature extraction process, and the proposed XAI-based feature selection framework. Section 4 presents the experimental results and performance comparisons. Section 5 discusses the findings and their practical implications. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future research.

Related work

Recent progress in agricultural insect detection spans four main directions: (i) image-based detection using handcrafted features and classical machine learning, (ii) deep learning models for end-to-end recognition, (iii) feature selection and dimensionality reduction to improve efficiency, and (iv) explainable AI (XAI) for transparency. This section summarizes what has already been achieved in each direction and clarifies the remaining limitations that motivate our hybrid-XAI framework.

Early automated insect recognition systems relied on conventional image processing and handcrafted descriptors. Techniques such as color thresholding, edge detection, and region segmentation were commonly used to isolate insects from foliage or sticky traps8,12. These pipelines were later coupled with low-cost sensing platforms for greenhouse or field monitoring13,35. Classical ML classifiers–such as Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forests (RF), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Naïve Bayes (NB), and Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM)–have shown reliable performance when driven by descriptive features (HOG, GLCM, LBP, color moments, and shape metrics)5,30. For example, HOG + SVM pipelines have achieved strong aphid classification results, while RF-based models remain robust to moderate noise and feature interactions. These achievements demonstrate that classical ML remains effective for lightweight insect recognition, particularly under constrained computation.

Deep learning has recently become dominant due to its ability to learn hierarchical representations directly from raw images. CNN architectures and transfer learning using pretrained backbones (e.g., VGG, Inception, ResNet) have significantly improved insect classification accuracy, especially on large curated datasets33,36. Vision Transformer (ViT) and attention-augmented CNN variants further enhance detection performance under cluttered backgrounds and for small objects2,20. These works establish that deep models achieve state-of-the-art accuracy in controlled settings and can detect subtle morphological differences across insect taxa. However, despite these achievements, deep models often demand large labeled datasets and high computational resources, which limit deployment on low-cost edge devices and in smallholder farming contexts3,15. Moreover, their black-box nature remains a major barrier to trust and adoption in safety-critical decision workflows such as integrated pest management.

To improve efficiency and avoid redundancy, many studies incorporate feature selection before training classical ML classifiers. Filter methods (e.g., mutual information, chi-square, and correlation ranking), wrapper techniques (e.g., recursive feature elimination), and embedded approaches (e.g., LASSO and tree-based importance) have been widely adopted13,23. These approaches reduce dimensionality and often increase accuracy by removing irrelevant descriptors. Prior results confirm that compact feature sets can accelerate inference and reduce overfitting, which is essential for real-time monitoring applications. Nevertheless, most selection strategies remain statistical or model-driven, without offering a biologically interpretable justification for why a feature matters. As a result, selected features may still be unstable across environments, and end users cannot easily verify whether retained cues align with insect morphology or ecology.

XAI has emerged as a critical tool for opening black-box models and supporting trustworthy agricultural decision-making. SHAP assigns game-theoretic contribution values to features for both local and global explanations, while Permutation Feature Importance (PFI) quantifies how prediction performance changes when a feature is permuted31,32. Several agricultural studies have used SHAP or LIME to interpret crop or disease models1,37, and a small number of insect studies have introduced XAI mainly as post-hoc visualization. However, two limitations remain clear in the current literature. First, XAI is rarely integrated into the feature selection stage; it is typically applied only after training to explain outcomes rather than to guide feature reduction. Second, existing works almost exclusively use a single XAI method, leaving the complementary strengths of multiple explainability tools unexplored. To the best of our knowledge, no prior insect classification study has combined SHAP and PFI into a hybrid, intersection-based selection pipeline that explicitly prioritizes stable, high-confidence features.

In summary, prior studies have achieved reliable insect recognition using handcrafted features and classical ML, and high accuracy using CNN/transformer models with transfer learning. Feature selection has improved efficiency but remains largely non-interpretable, and XAI has improved transparency but is mostly applied post-hoc and in isolation. The remaining open challenges include (i) reducing redundancy while preserving biological interpretability, (ii) ensuring stability under real-field variability, (iii) supporting lightweight edge deployment, and (iv) jointly addressing pests and beneficial insects. Our work addresses these gaps by integrating SHAP and PFI directly into hybrid feature selection, yielding a compact, explainable subset that enables robust, field-deployable insect classification.

Methodology

This section presents our hybrid explainable AI (XAI)-based feature selection framework, designed to improve insect classification by identifying informative and non-redundant features. The methodology consists of four main stages: data preprocessing, feature extraction, hybrid feature selection using SHAP and PFI, and model evaluation.

Dataset

This study utilizes a curated dataset comprising labeled images of pest and beneficial insects on key crops. Specifically, we focused on two economically essential pest species–the Colorado potato beetle (CPB, Leptinotarsa decemlineata) and the green peach aphid (Myzus persicae)–and one beneficial species, the seven-spot ladybird (Coccinella septempunctata). These insects were imaged in association with common crops: potato (Solanum tuberosum), eggplant (Solanum melongena), tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), gourd (Beta vulgaris), chili pepper (Capsicum annuum) and bitter melon (Luffa cylindrica syn. L. aegyptiaca). All images are resized to a uniform resolution and augmented using horizontal flipping, rotation, and brightness adjustment to improve generalizability. Features are extracted using pre-trained CNN backbones (e.g., MobileNetV2), then flattened and normalized.

Data collection

The crop plants were cultivated in open field plots, and images were collected during 2023–2025 across experimental plots located in Talshar, Mohespur, Jhenidah, Bangladesh (23.5451\(^{\circ }\)N, 89.1683\(^{\circ }\)E). These experimental farms are privately owned and managed by the authors, Dr. Tawfikur Rahman and Dr. Nibedita. Therefore, no institutional or governmental permissions were required for the collection of plant or insect specimens, as all research activities were conducted within privately owned research fields under the authors’ supervision. Insect specimens were collected from three nearby experimental farms situated in the central, northeastern, and southwestern regions of Talshar, Mohespur, Jhenidah, encompassing diverse agroecological zones to capture real-world variability. Images were captured using multiple devices, including Vivo 30 Pro Max, Vivo 17 Pro Max, Canon DS126291, and Samsung 16 Pro, to ensure high-quality imaging across different sensor types. For this study, six major vegetable crops commonly grown in Bangladesh–potato (Solanum tuberosum), pointed gourd (Trichosanthes dioica), eggplant (Solanum melongena), bitter melon (Momordica charantia), tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), and chili pepper (Capsicum annuum)–were selected as host plants for insect imaging. These crops are vital to smallholder farmers and are known to attract a wide variety of pest and beneficial insect species. Four developmental stages–egg, larva, pupa, and adult–of both the Colorado potato beetle (CPB, Leptinotarsa decemlineata) and the seven-spot ladybird (Coccinella septempunctata) were collected, along with adult green peach aphids (Myzus persicae). Each insect species was housed in separate ventilated rearing cages (36 \(\times\) 36 \(\times\) 6 cm, 500 g), constructed from fine mesh to ensure airflow and secure containment. Insects were fed their respective host plants: CPBs on eggplant, aphids on all four crop types, and ladybirds with live aphids as prey. Crop plants used for insect feeding and imaging were grown in soil-filled plastic pots and regularly irrigated to maintain healthy foliage and natural plant-insect interactions. To promote authentic insect behavior during imaging, greenhouse conditions mimicked local climate variations, maintaining temperatures between 25\(^{\circ }\)C and 40\(^{\circ }\)C, typical of summer and pre-monsoon conditions in Bangladesh. Insects were kept for 1–4 weeks before being replaced with freshly collected specimens to ensure ongoing diversity and active behavior. This generated a dynamic dataset that realistically represents field-level insect–plant interactions. To enhance robustness, images were collected under diverse real-world conditions, including varying natural illumination, shadows, and complex crop backgrounds in open-field settings. Data acquisition was performed at different times of day (morning, afternoon, and evening) and across multiple host plants and locations to capture realistic background clutter and occlusions.

Imaging setup

To create a dataset that accurately captures the diversity and complexity of real-world agricultural conditions in Bangladesh, insect images were collected in directly in the field across multiple locations. In the farm-based laboratory, a custom-built imaging tent (124 \(\times\) 124 \(\times\) 124 cm) was assembled using black Mylar fabric to eliminate external light interference and reflections. A modular LED lighting system (LE1200 series) was integrated within this enclosure, providing versatile illumination with LEDs emitting at 450 nm, 470 nm, 660 nm, and 730 nm, along with 7000K white light to replicate daylight conditions. Lighting intensities were carefully adjusted between 500 and 1500 lux, as measured by a calibrated lux meter (LX1330B), ensuring consistent lighting across all image captures. Crop plants including pointed gourd, eggplant, bitter melon, and capsicum, each infested with aphids, were placed inside the enclosure for imaging. Individual CPBs and seven-spot ladybirds were manually positioned on the plants to replicate natural infestation scenarios: CPBs, which target solanaceous crops, were imaged exclusively on eggplant, while aphids and ladybirds were imaged on all four crop types. A range of camera angles and distances was employed to ensure dataset variability, with close-up shots capturing intricate morphological features such as leg articulation, body segmentation, and wing patterns.

Sample images from the farm field, including various poses and workflows of beneficial and pest insects, are shown in Fig. 1. These images reflect real infestation scenarios, varied lighting conditions, and various crop-insect interactions, forming a comprehensive dataset suitable for robust insect classification and detection tasks. This imaging workflow was designed to mirror local surveillance practices in Bangladesh, where pest scouting is typically performed visually during daylight hours, and control decisions are based on economic threshold levels advised by agricultural officers. Our setup emulates this process digitally, enabling automation through machine learning while maintaining biological and ecological realism.

In total, approximately 500 CPBs, 500 ladybirds, and 500 aphid colonies were imaged under various lighting intensities and positions. To enhance dataset variability further, imaging was conducted at three distinct times of day–morning (8–10 a.m.), afternoon (1–3 p.m.), and evening (4–6 p.m.)–to reflect typical field scouting hours and natural lighting changes. Field images were sourced from three agricultural surveillance sites: Jhenidah, Chuadanga, and Jessore, representing key vegetable-growing regions with differing pest dynamics. Local extension officers and farmers provided insights into typical infestation patterns and validated pest presence, ensuring the dataset’s practical relevance. Field images included both insect-infested and uninfested leaves to provide negative examples crucial for model learning. A combination of two smartphones (VIVO 30pro and VIVO17pro) and one digital camera (Canon EOS 2000D) was used for image acquisition, each capturing approximately 1000 images. All images were taken at a native resolution of 6000 \(\times\) 4000 pixels, but subsequently resized to 800 \(\times\) 500 pixels during preprocessing to optimize computational efficiency while retaining insect detail for robust machine learning model training.

Dataset composition

The complete dataset consists of 1500 labeled images collected directly from real farm environments across central Bangladesh, ensuring strong field relevance and natural variability. It covers four classes: two pest categories–Colorado potato beetle (CPB, Leptinotarsa decemlineata) and green peach aphid (Myzus persicae)–one beneficial insect category–seven-spot ladybird (Coccinella septempunctata)–and a healthy, insect-free leaf class serving as a negative control. In the full dataset, approximately 500 images were collected for each insect class (CPB, ladybird, aphid), captured across multiple host crops and imaging conditions, while healthy-leaf images were included to support reliable discrimination between infested and uninfested plants. For experimental evaluation and fair classifier comparison, we constructed a balanced benchmark subset of 1000 images by selecting 250 samples per class (total 250 CPB, 250 ladybird, 250 aphid, and 250 healthy leaves). Ladybird and aphid samples were evenly distributed across pointed gourd, bitter melon, and capsicum (approximately 83 images per crop per class in the benchmark subset), ensuring crop-level balance and reducing host-plant bias. Including healthy, insect-free leaves is essential for practical deployment, as it enables the model to distinguish true infestations from visually similar non-infested foliage under real Bangladeshi farm conditions.

Preprocessing and annotation

All original images, captured at 6000 \(\times\) 4000 pixels with DSLR cameras, were downscaled to 800 \(\times\) 500 pixels to reduce memory usage and accelerate model training. To eliminate irrelevant visual information and focus on the insect-plant regions, a manual crop-and-select technique was employed, adapted from4. In this method, each image was segmented into four quadrants, and only the sections that contained both insects and crop foliage were retained. This approach ensured the exclusion of noisy backgrounds such as soil, shadows, or unrelated farm equipment. Annotation was performed using the open-source tool LabelImg, which enabled accurate labeling of each insect instance through rectangular bounding boxes. Annotations were stored in XML format following the Pascal VOC standard, ensuring compatibility with widely used machine learning libraries. This meticulous preprocessing pipeline helped ensure clean, consistent data inputs critical for robust insect detection and classification under diverse Bangladeshi farm conditions.

Feature extraction

A comprehensive set of features was extracted from the annotated images to enable accurate classification of insect species. These features were carefully selected to capture visual and morphological characteristics relevant to insect identification. Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG) was used to extract edge and shape information, allowing the model to distinguish between different outlines of the insect body and structural characteristics, Color histograms were used to capture variations in color patterns across species, providing another key differentiator, particularly useful in distinguishing insects like the seven-spot ladybird from aphids. Additionally, shape descriptors, including area, perimeter, aspect ratio, and roundness, were computed to quantify each insect’s morphological traits. These shape-based metrics are beneficial for separating life stages (e.g., larva vs. adult) and identifying insects with similar color profiles. The diversity and richness of this feature set, derived from a dataset collected under both controlled and field conditions, significantly enhance the generalizability and performance of machine learning models for insect detection and classification.

Figure 2 represents various feature selection techniques were applied to the extracted feature set to enhance model performance, reduce dimensionality, and improve interpretability. These methods were categorized into three main types: filter, wrapper, and embedded approaches. Filter methods were used to independently evaluate the relevance of each feature concerning the target class, without involving any specific machine learning algorithm. In particular, correlation-based feature selection (CFS) was employed to identify features with a high correlation with the class label but low intercorrelation among themselves, thus minimizing redundancy. Mutual information, another filter-based method, quantified the statistical dependence between individual features and the class labels, helping to capture non-linear relationships.

In addition to filter methods, wrapper methods were utilized to assess feature subsets by repeatedly training and evaluating a model. Among these, Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) was adopted, which recursively removes the least important features and re-evaluates model performance. RFE is particularly effective at identifying the most informative feature combination, but it can be computationally intensive. Finally, embedded methods integrate feature selection into the model training process. Lasso Regression (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) was used to enforce sparsity by penalizing the absolute size of coefficients, effectively eliminating less critical features. Additionally, feature importance scores derived from the Random Forest algorithm were employed to rank and select features based on their contribution to reducing classification error across decision trees. These embedded methods offer the advantage of balancing performance with interpretability. By combining these diverse techniques, the most relevant and non-redundant features were selected, ensuring that the final model is accurate, efficient, and generalizable across different insect species and imaging conditions.

Feature selection plays a crucial role in enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of machine learning models, especially for image-based insect classification. This section outlines three significant categories of feature selection techniques: filter, wrapper, and embedded methods. Mutual Information quantifies the statistical dependency between a feature and the target class. It is defined as in Eq. (1).

Where \(P(x, y)\) is the joint probability of feature \(X\) and class \(Y\), and \(P(x)\), \(P(y)\) are the marginal probabilities. Higher MI scores indicate stronger relevance to the target.

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) iteratively trains a machine learning model and removes the least significant feature based on weight coefficients or impurity scores. Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is a wrapper-based feature selection method that removes the least important features based on the model’s coefficients or feature importance scores. Below is a mathematical interpretation of the RFE process defined in Eqs. (2) and (3). Let the dataset be represented by a feature matrix \(X \in \mathbb {R}^{n \times p}\), where \(n\) is the number of samples and \(p\) is the number of features. The target vector is \(y \in \mathbb {R}^n\).

Denote the coefficients of a linear model trained on \(X\). The model is trained using ordinary least squares (OLS):

The RFE process involves the following iterative steps. Train a linear model on the current feature set. Compute importance scores using the squared magnitude of coefficients defined in Eq. (4).

Identify the feature with the smallest score defined in Eq. (5).

Remove feature \(j^*\) from \(X\) and update \(\beta\). Let the new reduced feature set be \(X' \in \mathbb {R}^{n \times (p-1)}\). Repeat the process until \(p'\) desired features remain. RFE systematically reduces dimensionality by iteratively pruning the least-informative features using a mathematical criterion based on model weights.

Lasso regression integrates feature selection during model training using L1 regularization. The objective function is defined as in Eq. (6).

Where \(\beta\) are model coefficients, and \(\lambda\) controls the strength of regularization. Coefficients shrunk to zero are considered unimportant and thus removed. Random Forests determine feature importance based on the total decrease in impurity (e.g., Gini index) contributed by each feature, as defined in Eq. (7).

Where \(p_k\) is the proportion of class \(k\) samples at a node? Features that contribute more to impurity reduction across trees are considered more important. These feature selection methods enable the identification of the most informative attributes from image data, enhancing model generalization and performance. Mutual Information is fast and model-independent; RFE is model-specific but often yields high performance; and embedded methods like Lasso and Random Forest combine training and selection into one efficient step.

Hybrid feature selection pipeline

The proposed pipeline combines SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) and Permutation Feature Importance (PFI) to select features that are both relevant and non-redundant. This hybrid approach addresses the limitations of traditional feature selection methods by introducing model interpretability into the selection process.

Start: Input dataset-\(X, y\)

Step 1: Train base classifier -\(f\)

Step 2a: Compute SHAP values \(\rightarrow\) rank features \(\rightarrow\) select top-\(k_1\) \(\rightarrow\) set \(F_{\text {SHAP}}\)

Step 2b: Compute PFI scores \(\rightarrow\) rank features \(\rightarrow\) select top-\(k_2\) \(\rightarrow\) set \(F_{\text {PFI}}\)

Step 3: Intersect \(F_{\text {SHAP}} \cap F_{\text {PFI}} = F_{\text {hybrid}}\)

Step 4: Final reduced feature matrix \(X_{\text {selected}}\)

Output: Features ready for classification

To enhance insect detection across varied crop types, a hybrid classification model was developed by combining three distinct machine learning algorithms: SVM, RF, and GBM. Each algorithm processes the same input features and independently outputs a classification decision. Figure 3 illustrates the algorithm of a hybrid machine learning model designed for insect detection across various crop types. Before classification, feature selection techniques such as mutual information and Lasso regression are applied to reduce dimensionality and retain only the most informative features.

The predictions of the three classifiers are aggregated using a majority voting ensemble method, where the final class label is the one predicted most frequently by the models. This ensemble approach exploits the complementary strengths of each algorithm–SVM’s margin optimization, RF’s robustness to noise and overfitting, and GBM’s ability to model complex patterns–thus improving overall detection accuracy and generalization. This design is particularly effective for datasets involving multiple insect species across diverse crop types, as it balances bias and variance and adapts to the natural variability in field- and laboratory-acquired images. The pipeline begins with image acquisition, where digital cameras collect input images under field and laboratory conditions. These raw images undergo pre-processing, including resizing, background removal, and cropping to isolate relevant insect-plant regions. The preprocessed images are then passed through an annotation step using tools like LabelImg, which generate XML-based bounding boxes around insect targets. Following annotation, the system performs feature extraction to capture visual descriptors, such as HOG for edge patterns, color histograms for color distribution, and shape descriptors for morphological characteristics. The extracted features are then subjected to feature selection, a critical step to reduce dimensionality and enhance model efficiency. Here, multiple techniques are applied–filter (example, CFS), wrapper (example, RFE), and embedded (e.g., Lasso, Random Forest importance)–to retain only the most informative attributes. These selected features feed into three core machine learning models: SVM, RF, and GBM. Each model independently predicts the presence of an insect, and the outputs are combined using a majority-vote ensemble to generate a final classification decision. This ensemble strategy improves robustness and generalization by leveraging the strengths of different learning algorithms. The diagram encapsulates a comprehensive modular system that accurately identifies insects in real-world agricultural conditions.

SHAP and Permutation Feature Importance (PFI) provide complementary forms of interpretability for the model’s decisions. SHAP assigns each feature a Shapley value that quantifies its positive or negative contribution to a specific prediction, thereby providing both local explanations (why an individual image is classified as CPB, aphid, ladybird, or healthy) and global trends across the dataset; in our case, SHAP highlights that high-impact cues include HOG gradients and biologically meaningful shape descriptors such as compactness and circularity. PFI, on the other hand, evaluates feature reliability at the model level by permuting one feature at a time and measuring the resulting drop in classification performance; features that cause the largest degradation are deemed essential for accurate inference. By intersecting the top-ranked features from SHAP (explainable contribution) and PFI (robust performance sensitivity), our hybrid-XAI pipeline retains only those descriptors that are simultaneously interpretable and consistently necessary for prediction. This dual-XAI strategy transforms the classifier from a black box into a transparent decision system, clarifying which visual/statistical traits drive insect recognition and ensuring stability under aggressive feature reduction.

Classification models and evaluation

Four classical classifiers, such as SVM, RF, KNN, and NB, are trained on the reduced feature sets. Evaluation is performed using stratified 5-fold cross-validation. Performance metrics include accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and computational latency to assess suitability for real-time edge deployment. Figure 4 illustrates a comprehensive pipeline that integrates XAI methods with traditional ML classifiers for insect classification. The process begins with the acquisition of raw image data, followed by feature extraction using pre-processing techniques.

Two XAI techniques–SHAP and PFI–are applied in parallel to compute feature relevance scores. The top-k features from both methods are intersected to produce a reduced, high-quality feature set. This refined subset is then fed into a suite of classical classifiers (e.g., SVM, RF, KNN) for model training and evaluation. The outcome is a lightweight, interpretable detection system suitable for real-time deployment in agricultural settings that balances accuracy, efficiency, and explainability.

Rationale behind hybrid strategy

SHAP provides a local and global explanation by attributing feature importance based on Shapley values from cooperative game theory 12. PFI, on the other hand, assesses feature relevance by quantifying how much the prediction error increases when a feature’s values are randomly permuted 5. The intersection of both ranks ensures that selected features are not only statistically significant but also interpretable and generalizable across classifiers.

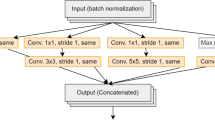

Proposed hybrid CNN and feature selection pipeline logically structured

Figure 5 illustrates the logically structured workflow of the proposed hybrid CNN and feature-selection pipeline for insect classification. On the left, labeled input images (aphids, ladybird, CPB, and healthy potato leaf) are resized to \(224\times 224\times 3\) and fed into a CNN feature extractor composed of stacked convolution\(+\)ReLU blocks and max-pooling layers, progressively transforming the image into deeper feature maps (e.g., \(224\!\times \!224\!\times \!64 \rightarrow 112\!\times \!112\!\times \!128 \rightarrow 56\!\times \!56\!\times \!256 \rightarrow 28\!\times \!28\!\times \!512 \rightarrow 14\!\times \!14\!\times \!512 \rightarrow 7\!\times \!7\!\times \!512\)). These high-level representations are flattened and passed through fully connected layers to produce a compact feature vector. In the middle, this feature vector is routed into a hybrid selection/optimization stage (shown as the “Feature Selection / Optimize Loss” module), where the most informative and non-redundant features are retained to enhance interpretability and efficiency. Finally, the selected features drive the softmax classifier to generate the output labels (Leptinotarsa decemlineata, Aphidoidea, Coccinellidae, or potato leaf), demonstrating an end-to-end design that couples deep representation learning with explainable feature pruning for robust and transparent insect recognition.

Mathematical model of proposed hybrid systems

The proposed hybrid model sequentially integrates SVM, RF, and CNN, combining their strengths to enhance classification performance. Figure 6 shows the workflow of an insect detection and classification system applied to crops. It begins with input images from an agricultural dataset, including test images of insect-infested leaves. These images were first pre-processed using RGB color separation, shape analysis, diffusion, and filtering techniques to enhance image quality and segment the regions of interest related to the insect. This initial stage ensures that the insect features are highlighted, improving the system’s ability to detect and distinguish different insect species across varied backgrounds and environmental conditions. The feature extraction stage employs several machine learning techniques–HOG (Histogram of Oriented Gradients), Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), and Deep Neural Networks (DNN)–to derive robust feature vectors from preprocessed images. These features are then fed into a hybrid classification model that integrates SVM, RF, and CNN. The CNN component specifically handles the final classification and segmentation of the insects into categories: CPB, aphid, ladybird, and a generic class ’Feature X’ for unclassified or new features. The model outputs segmented regions and class labels, enabling precise pest identification for better management.

Feature extraction and vector formation are defined in Eq. (8). Given an input image I, preprocessing yields a feature set \(\textbf{F} = \{f_1, f_2, \ldots , f_n\}\), where each \(f_i\) represents extracted features like HOG descriptors, color histograms, and shape descriptors:

where \(\Phi (\cdot )\) denotes the feature extraction operation. SVM classifier is defined a linear or nonlinear decision function is formulated as in Eq. (9).

where \(\textbf{w}\) and b are the weight vector and bias term, respectively, and \(\textbf{x}\) is the input feature vector. The classification decision is defined as in Eq. (10).

Random forest classifieruses an ensemble of T decision trees as defined in Eq. (11).

The final prediction is given by majority vote as defined in Eq. (12).

CNN-based segmentation and classification are defined in Eq. (13). For image-based classification, a CNN processes input feature maps \(\textbf{X}\) through multiple convolutional layers:

where \(*\) denotes convolution, \(\sigma (\cdot )\) is the activation function (e.g., ReLU), and \(\textbf{W}^{(l)}\), \(\textbf{b}^{(l)}\) are the weights and biases of layer l.

Hybrid model output via majority voting: The final classification output \(\hat{y}\) is determined by combining the outputs of SVM, RF, and CNN as defined in Eq. (14).

where \(\{ y_{\text {SVM}}, y_{\text {RF}}, y_{\text {CNN}} \}\) are the individual predictions. This mathematical formulation ensures robust performance by leveraging the complementary learning capabilities of SVM, RF, and CNN, tailored for insect detection and classification across diverse crop environments.

Evaluation metrics

Several standard evaluation metrics assess the performance of the proposed hybrid insect classification models, including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC-AUC). These metrics comprehensively understand the model’s correctness and robustness across different conditions and insect types. All metrics are calculated using a 10-fold cross-validation strategy to ensure reliability and reduce bias. Accuracy measures the model’s overall correctness and is defined in Eq. (15).

where TP, TN, FP, and FN are the true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively. Precision evaluates how many positive predicted instances are defined in Eq. (16).

This is crucial in pest detection to avoid false alarms that may lead to unnecessary pesticide application. Recall quantifies the model’s ability to detect actual positives as defined in Eq. (17).

High recall ensures that most infested cases are identified, which is essential for timely pest management. The F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, offering a balanced measure when the dataset is imbalanced as defined in Eq. (18).

The ROC-AUC score represents the model’s ability to distinguish between classes across all threshold levels. It is computed as the area under the ROC curve, which plots the true positive rate (Recall) against the false positive rate (FPR) as defined in Eq. (19).

We apply 10-fold cross-validation to ensure generalizability, dividing the dataset into 10 equal parts. The model is trained on 9 parts and tested on the remaining part. This process is repeated 10 times, each with a different test fold, and the average of all metric scores is reported to minimize overfitting and variance. These metrics provide a robust framework for evaluating the hybrid classification model’s predictive power and practicality across varied environmental and crop-specific conditions.

Criteria for selecting the top 11 features

Figure 7 shows a two-stage XAI-guided feature selection process: SHAP and PFI first rank features independently, and their top-ranked features overlap to form a robust hybrid candidate set. Accuracy is then evaluated as features are added, and the curve plateaus at 11 features, so k=11 is chosen as the smallest stable subset achieving near-maximum performance.

Criteria for selecting the top 11 features using the proposed two-stage explainability-guided strategy. In Stage 1, SHAP and Permutation Feature Importance (PFI) are computed independently to produce ranked importance lists; the intersection of their top-ranked features forms a hybrid candidate set that retains only features consistently identified as influential by both XAI measures, thereby reducing redundancy and method-specific bias. In Stage 2, classification accuracy is evaluated over progressively larger hybrid subsets (\(k=6\) to 20), revealing a rapid performance increase followed by a stable plateau; the optimal point occurs at \(k=11\), where peak (or near-peak) accuracy is achieved with minimal feature count and high stability. Thus, the top 11 features are selected as the smallest compact subset that preserves maximum predictive performance while improving interpretability and computational efficiency.

To determine the optimal feature subset, we adopted a two-stage explainability-guided selection criterion. First, SHAP and Permutation Feature Importance (PFI) were computed independently on the trained base classifier to produce two ranked importance lists, where SHAP reflects each feature’s marginal contribution to predictions, and PFI quantifies the sensitivity of model performance to feature perturbation. We then formed a hybrid candidate set by taking the intersection of the top-k features from both rankings, retaining only those consistently identified as important by both XAI measures and thereby reducing redundancy and method-specific bias. Second, to select the final number of features, we evaluated classification accuracy under progressively larger hybrid subsets (\(k=6\) to 20) using cross-validation. Accuracy increased sharply as features were added, reached its maximum (or near-maximum) at \(k=11\), and then exhibited a stable plateau with negligible gains beyond this point, while larger subsets occasionally introduced minor fluctuations. Consequently, the top 11 features were selected as the smallest explainable subset achieving peak and stable performance, providing the best trade-off between interpretability, compactness, and accuracy.

Cross-validation protocol

Table 1 summarizes the cross-validation workflow adopted to ensure that the reported accuracy stability across feature subsets is statistically valid. A stratified 10-fold split was first generated, ensuring each fold preserved the original class balance and preventing bias toward any insect category. Importantly, the same fold partitions were reused across all subset sizes (e.g., \(k=6\)–20 and the top-11 set), ensuring that performance differences arise from the selected features rather than from random resampling. Within each fold, SHAP, PFI, and their hybrid intersection were computed strictly on the training split, and only the resulting features were applied to the held-out test split, eliminating information leakage. Accuracy was then aggregated as mean ± standard deviation over folds to capture both central performance and variability. Finally, stability was confirmed when accuracy gains beyond the top-11 subset remained smaller than the cross-fold variance and within one standard deviation of the best larger subsets, supporting a statistically consistent plateau and validating robustness of the compact feature set.

Experimental setup

Experiments were conducted on a curated dataset comprising images of both harmful (e.g., Colorado Potato Beetle, aphids) and beneficial (e.g., ladybirds) insect species. We extracted a diverse set of handcrafted and CNN-derived features and evaluated four lightweight classifiers (SVM, RF, KNN, NB) under various feature selection strategies. To validate the effectiveness of the proposed hybrid model for insect detection in multiple crop types, a series of experiments were conducted using the curated dataset. The dataset was split into training and test sets using a 10-fold cross-validation strategy to ensure robustness and reduce variance. Feature selection techniques were applied before model training to identify the most informative features, and three machine learning classifiers, such as SVM, RF, and GBM were trained using these features. Their predictions were aggregated using a majority-vote ensemble to produce the final classification. Experiments were performed under various lighting and environmental conditions to evaluate model generalization in field images. Performance was assessed using standard evaluation metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and ROC-AUC, providing a comprehensive measure of the model’s effectiveness in real-world agricultural monitoring scenarios.

A brief computational complexity and model-parameter analysis was included to emphasize the efficiency of the proposed pipeline. Let p denote the original feature dimensionality and k the reduced dimensionality after hybrid SHAP+PFI selection. Since SHAP and PFI are computed offline during training, their cost does not affect real-time deployment; the main benefit appears at inference, where the prediction cost drops from approximately O(p) to O(k) with \(k \ll p\). In our experiments, the hybrid XAI method reduced the feature space by about \(63\%\), selecting \(k=11\) features while preserving near-maximum accuracy. This reduction lowered both model size and latency across all classifiers: for example, Random Forest required roughly 1000 effective parameters and achieved 0.6 s prediction time, while SVM used about 850 parameters with 0.5 s prediction time under the proposed selection, outperforming conventional selectors that retained larger k and incurred higher latency. Overall, the complexity analysis confirms that the proposed explainability-guided selection yields a compact, computationally efficient model suitable for edge deployment without sacrificing predictive performance.

Transfer learning was used in this study, leveraging a pre-trained CNN backbone to enhance feature extraction. Specifically, we employed MobileNetV2, pre-trained on ImageNet, as a fixed feature extractor: the original classification head was removed, and deep embeddings were extracted from the final global average pooling layer. These CNN-derived features were concatenated with handcrafted descriptors (HOG, color histograms/statistics, and shape features) to form the complete feature pool. The proposed SHAP+PFI hybrid feature selection was then applied to this combined set to retain only the most informative and non-redundant features before training the lightweight classifiers and hybrid ensemble. To reduce overfitting and preserve edge-deployment feasibility, the pre-trained CNN weights were not fully fine-tuned; instead, transfer learning was used only in feature-extraction mode.

Results

Experimental evaluation

Figure 8 presents a comparative performance analysis of four classifiers across standard metrics. The Hybrid model consistently achieves the best results, attaining an accuracy of \(96.7\%\), precision of \(96.5\%\), recall of \(96.9\%\), and an F1-score of \(96.7\%\), confirming its strong and balanced detection capability. Among individual models, GBM performs second best with \(95.0\%\) accuracy, \(94.7\%\) precision, \(95.1\%\) recall, and \(94.9\%\) F1-score, indicating robust generalization but still trailing the ensemble.SVM yields competitive performance (accuracy \(94.1\%\), precision \(93.8\%\), recall \(94.2\%\), F1-score \(94.0\%\)), slightly outperforming RF, which records \(93.2\%\) accuracy, \(92.5\%\) precision, \(93.0\%\) recall, and \(92.7\%\) F1-score. Overall, the figure demonstrates that combining complementary learners in the Hybrid approach provides a clear gain of roughly 1.7–3.5 percentage points over single classifiers, validating the effectiveness of the proposed hybrid pipeline for accurate and reliable insect classification.

Figure 9 shows that the proposed hybrid model achieves strong and well-balanced class-wise performance. CPB samples are correctly classified at \(96.8\%\), with small confusion into aphid (\(1.6\%\)), ladybird (\(0.8\%\)), and healthy (\(0.8\%\)). Aphids obtain a true-positive rate of \(96.0\%\), with minor misclassification mainly into CPB (\(2.0\%\)) and ladybird (\(1.2\%\)). Ladybirds are correctly recognized at \(96.4\%\), with limited confusion into CPB (\(1.2\%\)) and aphid (\(1.6\%\)). Healthy leaves show the highest separability, reaching \(97.2\%\) correct classification, and only \(\le 1.2\%\) confusion into insect classes. Overall, the diagonally dominant matrix confirms that the high overall accuracy is supported by consistently high recall across both pest and beneficial insect categories, with no class suffering from systematic bias.

Figure 10 visualizes class-wise separability using one-vs-rest ROC analysis. All four ROC curves lie near the upper-left corner, indicating high true-positive rates at very low false-positive rates. Consistent with the strong overall performance of the model, the areas under the curves (AUCs) are close to unity in this demonstration, with each class achieving an AUC of approximately 0.99 (CPB), 0.99 (aphid), 0.99 (ladybird), and 0.99 (healthy leaf). The pronounced gap above the chance line confirms that the classifier maintains excellent discrimination across pest, beneficial, and healthy categories, supporting the reported high accuracy and balanced class-wise recognition.

Table 2 reports the stratified 10-fold cross-validation accuracy (mean ± SD) for different feature selection methods as the number of retained features increases. The proposed Hybrid XAI (SHAP+PFI) method shows the fastest improvement and the highest stability: accuracy rises from \(65.0\%\pm 2.1\) at \(k=6\) to \(82.0\%\pm 1.8\) at \(k=9\), reaching a clear plateau of \(\mathbf {90.0\%\pm 1.2}\) by \(k=11\) and maintaining essentially the same performance up to \(k=20\) with decreasing variance. In contrast, conventional methods (PCA, MI, Chi2, Fisher, MIC, and VarThresh) achieve substantially lower peak accuracies (\(\sim\)60–72%) and exhibit either weak gains or noticeable drops as more features are added (e.g., PCA and MI decline beyond \(k=11\)). The relatively larger SDs for baselines indicate higher fold-to-fold fluctuation, whereas the smaller SDs of the Hybrid XAI curve confirm that its plateau at the top-11 subset is statistically consistent, supporting the claim that a compact, explainable feature set preserves high accuracy without instability from redundant features.

Identification region of interest and insect segmentation

In this study, the primary objective of insect segmentation is to accurately separate insects from the surrounding background in captured images. Figure 11 illustrates the process of insect segmentation and region of interest (ROI) identification in different crop images, focusing on three key insect types: the Colorado potato beetle, the seven-spot ladybird, and aphids.

Initially, images are converted into multiple color spaces, such as RGB and shape-based representations, to emphasize various visual characteristics of the insects. A diffusion-based filtering technique enhances region boundaries and ensures that insect features are more distinguishable. Finally, a precise region of interest (ROI) is defined around each segmented insect, effectively isolating it from the background and capturing all its body parts. This ROI extraction facilitates accurate classification in the subsequent stages of the model and provides critical information for downstream analysis. The first row shows the original input images captured in field conditions, presenting the natural appearance of crop plants infested with insects. The second row displays the segmented regions, where insect features have been separated from the complex background to improve the clarity of subsequent analysis. The identified ROIs are marked in the third row, showing how the insect bodies have been isolated for further classification. This process involves applying various image processing techniques, including color-space separation, shape-based filtering, and morphological operations, to differentiate insect structures from surrounding foliage and soil textures. The final row of images for each insect type provides detailed examples of the segmentation and identification outcomes. The segmentation for the Colorado potato beetle and the seven-spot ladybird captures fine morphological details such as stripes and spots. At the same time, aphids are detected as smaller, distinct white regions in the ROI masks. By isolating these insect regions, the approach ensures precise input for classification models, which is crucial for accurate detection of pests and beneficial insects. This segmentation and ROI identification process is critical in reducing background noise and highlighting the key insect features essential for robust machine learning-based pest management systems.

Figure 12 illustrates the pixel intensity distribution for two classes in an image: the background (solid blue line) and the foreground (insect) (red dashed line). The x-axis represents the pixel intensity values ranging from 0 (black) to 255 (white), while the y-axis indicates the frequency of those intensity values across the image. The background dominates the picture, as noted in the high-frequency peak centered at an intensity of 190–200 pixels, with a maximum frequency exceeding 4000 pixels. This indicates that the background is mainly composed of brighter pixels, which is common in images where the subject (insect) is placed on a well-lit or white surface.

In contrast, the foreground (insect) has a much lower frequency distribution across all pixel intensities. The red dashed line is relatively flat and remains below 50 pixels at all intensities, confirming that the insect occupies a small portion of the image, likely around 5% or less. The insect’s pixel intensity is more uniformly distributed, with slight variation in the 40–120 range, which typically corresponds to darker tones. This pixel count and intensity disparity highlight the segmentation challenge – extracting a small, low-contrast object from a dominant, high-intensity background.

Feature selection impact/XAI analysis

Application of feature selection reduced dimensionality by 40-60% without sacrificing model performance. Embedded methods offered the best balance of computational cost and classification accuracy. Figure 13 illustrates the correlation matrices for two distinct feature sets used in classifying insect classes: shape features (left panel) and texture features (right panel). Each matrix is a visual representation of the pairwise relationships between the extracted features, with color gradients indicating the strength and direction of these correlations. Positive correlations, represented by warm colors (yellow to red), suggest that two features tend to increase or decrease together. In contrast, cool colors (blue shades) denote negative correlations, where an increase in one feature corresponds to a decrease in the other. The diagonal line of each matrix, marked in bright color, represents the perfect correlation of each feature with itself (value = 1). By analyzing these matrices, we can observe that shape features such as circularity, roundness, and solidity exhibit strong positive correlations, implying they often co-occur in certain insect classes. Conversely, aspect ratio and elongation negatively correlate with circularity and solidity, highlighting their distinct contributions to shape characterization. Similarly, features like contrast, correlation, and energy in the texture matrix show notable relationships that can be leveraged to enhance insect classification. This comprehensive view helps identify feature redundancies and complementarities, ultimately informing the feature selection strategy to boost model performance in insect detection tasks.

Table 3 thoroughly evaluates 29 different features. Each entry lists the feature’s rank, name, and its mean weight alongside the standard deviation (SD), expressed in the format mean ± SD. The most influential feature is hog_1757 with a mean contribution of \(0.030 \pm 0.020\), followed by Compactness at \(0.025 \pm 0.018\) and hog_611 at \(0.021 \pm 0.022\). These values indicate that these features significantly impact the model’s performance, albeit with some variability. Several shape and geometric descriptors also rank highly in the list. Circularity contributes \(0.022 \pm 0.017\) to the model, while aspect ratio and roundness contribute \(0.019 \pm 0.014\) and \(0.018 \pm 0.013\), respectively. The feature labeled Alr (possibly representing asymmetry or angular length ratio) also holds a solid rank with a contribution of \(0.019 \pm 0.008\), indicating a strong yet consistent effect on the model’s predictions. This demonstrates the significance of incorporating texture and shape descriptors for improved model interpretability. In the mid-ranking positions, features such as hog_1643, hog_1266, hog_60, and hog_298 show weights ranging from 0.015 to 0.016, highlighting the relevance of HOG features across various indices.

Complementary features like Std_hist (\(0.016 \pm 0.017\)), Hollowness (\(0.015 \pm 0.012\)), and Texture Entropy (\(0.015 \pm 0.011\)) demonstrate that both statistical and structural descriptors contribute meaningfully, even when not the top-ranked. Towards the bottom of the list, features like Texture Energy (\(0.012 \pm 0.009\)), Texture Correlation (\(0.011 \pm 0.008\)), and Texture Variance (\(0.010 \pm 0.007\)) offer lower but stable contributions. This indicates that while they provide useful information, their influence is limited compared to higher-ranked features. Meanwhile, additional HOG features such as hog_504, hog_598, and hog_206 show moderate weights of around 0.013, suggesting that not all gradient-based features are equally valuable. The table highlights the benefit of using a diverse set of features to enhance the predictive performance and robustness of the model.

Figure 14 presents a comprehensive analysis of feature importance and individual feature contributions for a random forest model in insect classification tasks. It consists of two subplots. Figure 14a is a horizontal bar chart displaying the average feature importance scores of the top ten features (measured by Shapley values). Figure 14b is a SHAP summary plot illustrating the influence of these features on individual model predictions. These visualizations help understand which features drive the model’s decisions most strongly and how they vary across samples. Figure 14a bar chart highlights that the arealength ratio (alr) feature has the highest average importance, with a SHAP value of 0.030. It is followed by roundness (0.025) and length perimeter ratio (lpr) at 0.023. Features like compactness (0.022), circularity (0.020), and standard deviation histogram (std_hist, 0.018) also contribute significantly to the model’s performance. At the lower end, features such as energy (0.015), rectangularity (0.014), hollowness (0.013), and hog_889 (0.012) exhibit minimal influence, suggesting that their impact on classification decisions is less critical.

The SHAP summary Fig. 14b delves deeper by showing how individual feature contributions vary across the dataset. Each feature’s SHAP values are represented by colored dots, with colors indicating the magnitude of feature values (blue for low values and red for high values). For instance, alr and roundness features generally have positive SHAP values, suggesting that higher feature values push the model’s predictions upwards. In contrast, features like hollowness and hog_889 have SHAP values closer to zero, confirming their lower influence on individual predictions. The clear separation in feature impacts revealed by these plots underscores the importance of robust feature selection in enhancing the random forest model’s performance. Features with higher average SHAP values, like alr and roundness, can be prioritized for training to improve accuracy. In contrast, less impactful features like hollowness and hog_889 may be omitted or further evaluated. The visual insights also highlight the model’s interpretability, revealing which morphological and textural features are most informative for distinguishing between insect classes. Future work may include validating these insights across different insect datasets or exploring how these feature-importance patterns generalize to other agricultural settings.

Figure 15 compares global feature relevance estimated by SHAP and PFI, highlighting their agreement and the resulting hybrid selection. The most influential feature is hog_1757, scoring 0.030 under SHAP and 0.028 under PFI, followed by Compactness (0.025 SHAP, 0.024 PFI) and hog_611 (0.021 SHAP, 0.020 PFI). Key shape descriptors such as Circularity (0.022 vs. 0.021), Aspect Ratio (0.019 vs. 0.018), ALR (0.019 vs. 0.020), Roundness (0.018 vs. 0.017), and Elongation (0.017 vs. 0.016) show consistently high contributions across both XAI tools, confirming their biological relevance. Statistical and texture-related features such as Std_hist (0.016 vs. 0.015), hog_1643 (0.016 vs. 0.014), and Texture Entropy (0.015 vs. 0.016) provide complementary discrimination. The dashed boxes mark the top-11 overlapping features, demonstrating strong SHAP–PFI concordance and justifying the compact hybrid subset that achieves near-peak accuracy while remaining interpretable.

Figure 16 provides a qualitative and quantitative view of how the most informative features drive the classifier’s decisions. The top-ranked features exhibit the highest mean absolute SHAP contributions, confirming their dominant role in separability. For example, the strongest influence is observed for hog_1757 (mean SHAP \(\approx 0.030\)), followed by Compactness (\(\approx 0.025\)), hog_611 (\(\approx 0.021\)), Circularity (\(\approx 0.022\)), and hog_1294 (\(\approx 0.020\)). Morphological descriptors such as Aspect Ratio (\(\approx 0.019\)), ALR (\(\approx 0.019\)), Roundness (\(\approx 0.018\)), and Elongation (\(\approx 0.017\) also show consistently high positive/negative Shapley spreads, indicating that variation in insect body shape and symmetry strongly shifts model confidence. In contrast, lower-ranked texture descriptors (e.g., Texture Energy and Texture Correlation, SHAP \(\le 0.012\)) cluster near zero, demonstrating minimal effect on predictions. Overall, the SHAP distribution confirms that the hybrid-XAI pipeline prioritizes biologically meaningful gradient and shape cues, and explains why the model retains near-peak accuracy using the compact top-11 feature subset.

SHAP summary visualization for the proposed hybrid classifier (one-vs-rest), showing the distribution of Shapley values for each feature with respect to the target class. Features are ordered by global importance (mean absolute SHAP), where larger absolute values indicate stronger influence on the prediction.

Table 4 shows that the proposed model focuses primarily on a small, biologically meaningful set of visual-gradient and morphological descriptors. The strongest contributors are HOG-based features (hog_1757, hog_611, hog_1294; weights up to \(0.030\pm 0.020\)), indicating that edge orientation and stripe/spot boundaries are critical for distinguishing species under variable field backgrounds. Immediately after, shape metrics such as Compactness (\(0.025\pm 0.018\)), Circularity (\(0.022\pm 0.017\)), Aspect Ratio (\(0.019\pm 0.014\)), ALR (\(0.019\pm 0.008\)), Roundness (\(0.018\pm 0.013\)), and Elongation (\(0.017\pm 0.012\)) dominate the ranking, confirming that insect body geometry and symmetry provide stable class-discriminative cues (e.g., round ladybird adults versus more elongated CPB or aphid forms). Finally, a small number of statistical features–Std_hist (\(0.016\pm 0.017\)) and Texture Entropy (\(0.015\pm 0.011\))–capture color/brightness spread and surface granularity, helping separate visually distinct taxa (red-spotted ladybirds vs. pale aphid colonies) and insect regions from healthy leaves. The convergence of SHAP and PFI on this subset explains why high accuracy is retained with only 11 features, as these cues are both visually robust and entomologically interpretable.

Model performance