Abstract

Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK) is a severe eye infection that can cause severe vision loss, especially in contact lens wearers. Rapid and accurate diagnosis is crucial for achieving favorable outcomes. Traditional methods, such as culture, are slow and have variable sensitivity, while molecular techniques offer improved detection. This study evaluated nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) targeting the 18S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene for rapid AK diagnosis, comparing its performance to one-step PCR, culture, and in vivo confocal microscopy (IVCM). This study included 42 suspected AK patients who underwent IVCM and corneal scraping for culture, PCR, and nested PCR. AK diagnosis was confirmed based on clinical findings, risk factors, treatment response, and at least one positive diagnostic test. Out of 42 patients, 27 were positive for Acanthamoeba with at least one of the diagnostic methods. Based on the diagnosis of definite AK, the sensitivity of IVCM, culture, PCR, and nested PCR was 77.78%, 37.04%, 62.96%, and 96.3%, respectively. The specificity and positive predictive values were 100% for all the tests. The negative predictive values of IVCM, culture, PCR, and nested PCR were 71.43%, 46.88%, 60%, and 93.75%, respectively. Nested PCR results displayed the highest agreement with IVCM. In conclusion, nested PCR enhances AK detection compared to conventional methods, improving sensitivity in low corneal scrape quantities. Combining high-sensitivity tests increases diagnostic accuracy, and nested PCR with IVCM is the most effective approach. When IVCM is unavailable, nested PCR serves as a reliable diagnostic tool, especially when culture and one-step PCR yield negative results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK) is a vision-threatening infection caused by the opportunistic free-living amoeba Acanthamoeba, which is widely distributed throughout the environment1. The global annual incidence of AK has been estimated to be 2.9 cases per million individuals2. AK occurs predominantly in contact lens wearers with poor lens hygiene and increased water exposure3. Rarely, in non-contact lens wearers, AK can be caused by corneal trauma from exposure to contaminated water or soil. In the last decade, the prevalence of AK has been on the rise due to the increased use of contact lenses4.

AK can lead to severe vision loss if not diagnosed and treated promptly and correctly. Treatment with a combination of topical polyhexamethylene biguanide (PHMB) and hexamidine or propamidine is very effective when initiated at early stages of disease5,6. However, in the late stages, cysts resistant to medications may cause recurrence even after proper treatment. Moreover, the chronic nature of the disease requires long-term treatment, which can lead to compounded clinical outcomes and reduced visual acuity7,8.

Prompt diagnosis and treatment are crucial for achieving favorable clinical outcomes and preserving visual acuity9,10,11. However, diagnosing AK is challenging due to its symptoms overlapping with herpes simplex virus (HSV), fungal keratitis, Pseudomonas infections, and secondary bacterial superinfections12,13. Misdiagnosis, treatment delays, or corticosteroid use can facilitate amoebic penetration into the corneal stroma, leading to severe complications such as neuritis and even progressing to chorioretinitis14.

AK diagnosis is typically based on a combination of clinical manifestations, risk factors, treatment response, culture, and in vivo confocal microscopy (IVCM). Although culture remains the most common laboratory method, it requires up to 21 days of incubation, leading to delayed diagnosis. Its sensitivity is also low due to the limited number of amoebae and insufficient corneal scraping samples15,16. IVCM is a rapid, non-invasive diagnostic method that has been used to diagnose microbial keratitis in recent years. However, the low accessibility to IVCM, the requirement of a highly experienced operator, and the lack of standards for the interpretation of acquired images pose several challenges to IVCM. Additionally, this modality has low sensitivity at the beginning of the disease when cyst numbers are low, leading to misdiagnosis of the corneal and inflammatory cells with Acanthamoeba cysts17,18. In recent years, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methods have been increasingly used for AK diagnosis. Amplifying the 18S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene using JDP primers provides a robust diagnostic tool, as this gene is present in multiple copies within each cell19. However, the limited amount of corneal scraping and the low amoeba burden in the early stages of the disease may result in false-negative results20,21.

Nested PCR is a low-cost, highly sensitive method to detect low numbers of microorganisms. In this method, the specificity and sensitivity of detection are enhanced through two rounds of amplification by two separate primer sets, which eliminates the nonspecific amplification22. It is more advantageous than conventional PCR for detecting scarce DNA in a small sample size, such as a corneal scraping23. Accordingly, in the present study, we developed nested PCR as a complementary method for diagnosing AK in corneal scraping and compared it with conventional methods, including PCR, IVCM, and culture.

Methods

Study design and participants

This study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (code number: IR.TUMS.SPH.REC.1398.182). Written informed consent was obtained from the subjects after explaining the technique and the potential benefit of microbiological diagnosis.

The present study included 42 patients with keratitis referred to Farabi Eye Hospital between April 2018 and April 2021. All patients underwent a complete slit-lamp examination by an experienced cornea specialist, and relevant clinical history, examination findings, and demographic data were recorded in a standardized study form. Patients with clinical features suspicious for AK underwent IVCM to evaluate the presence of Acanthamoeba cysts in the epithelium and anterior stroma. Corneal scraping samples were then collected from all patients and transferred to the Department of Medical Parasitology and Mycology at Tehran University of Medical Sciences for culture and molecular testing. A definitive diagnosis of AK was established based on clinical findings, risk factors such as contact lens use or corneal trauma, resolution with anti-Acanthamoeba treatment, and a positive result from at least one diagnostic test (IVCM, culture, PCR, or nested PCR)20,21.

Diagnostic tests

In-vivo confocal microscopy

IVCMs were performed at Farabi Eye Hospital according to a standard protocol, as previously described24. The affected cornea was anesthetized using 0.5% tetracaine eye drops. Volume scans of the corneal ulcer were obtained using the HRT III laser scanning in vivo confocal microscopy, IVCM (Heidelberg Engineering, GmBH, Dossenheim, Germany) with Rostock Corneal Module, RCM (63x magnification objective lens, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan), by a trained ophthalmologist. Scans were recorded at the center and margins of the ulcer, with progressively overlapping scans taken from the surface to the deepest region of the ulcer (10 images in total), following a standard procedure25.

Corneal scraping

After the IVCM imaging, corneal samples were obtained from the patients. At first, 0.5% tetracaine eye drops were applied, and then, the corneal scrapings were prepared from the leading edge of the corneal ulcers using a sterile spatula. Samples were immediately collected in 500 µL of sterile 1X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and, for further analysis, transported to the Protozoology Laboratory at the Department of Medical Parasitology and Mycology, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences. All samples were divided into two parts and subjected to culture and DNA extraction.

Culture of Acanthamoeba

The corneal scraping samples were cultured on 1% Non-Nutrient Agar (NNA) (Difco Agar Noble; Becton Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD) overlaid with Escherichia coli (E. coli). Mediums were incubated at 25–30 °C and monitored for growth over 21 days. After culturing, the plates were examined daily under a light microscope to observe Acanthamoeba trophozoites and cysts26.

DNA extraction

DNA was extracted from the corneal samples using a High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Roche, Germany). Acanthamoeba T4 genotype (MT820305.1), previously isolated from an AK patient, was designated as a positive control27. The strain was grown on NNA covering E. coli; afterward, the cysts were collected in 1 mL 1X PBS. After washing with PBS, 105 were subjected to DNA extraction as a positive control. The quantity of DNA was measured using a NanoDrop UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and DNA was stored at −20 °C until further use.

One-step PCR

The partial 18S ribosomal RNA sequence of Acanthamoeba was amplified by the primers JDP1 (5′-GGCCCAGATCGTTTACCGTGAA-3′) and JDP2 (5′-TCTCACAAGCTGCT AGGGGAGTCA-3′). The length of the amplicon varies between 423 and 551 bp, depending on the genotype28. Amplifications were performed in 25 µL containing 12.5 µL of Taq DNA Polymerase Master Mix (Amplicon, Denmark), 1 µL of each Forward and Reverse primers (10 µM), 17 µL of PCR-grade water, and 4 µL of template DNA. PCR amplification was carried out in a Peqlab peqSTAR, Thermal Cyclers (PEQ LAB, Germany) using the following thermal cycling conditions: the initial denaturing step of 5 min at 95 °C, followed by 35 cycles at 94 °C for 45 s, 60 °C for 45 s, 72 °C for 45 s, and final extension of 72 °C for 10 min. Acanthamoeba T4 genotype was used as a positive control, and a non-template control as a negative control. PCR amplifications were observed by electrophoresis of 4 µL PCR product aliquots in a 1.5% agarose gel containing safe stain, and amplicon bands were examined using the Vilber Lourmat Gel Documentation System (France).

Nested PCR

Nested PCR was conducted using two sets of outer and inner primers. The JDP1 and JDP2 were considered outer primers, as described earlier28. To increase the sensitivity of detection, the inner primers were designed based on the highest conserved region of the JDP sequence using Primer 3 version 0.4.0 (https://bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3-0.4.0/). The inner primers, including NJK1 (5′-CTGCCACCGAATACATTAGC-3′) and NJK2 (5′-AACGTCTCCTAATCGCTGGTC-3′), were used to amplify a product that ranged between 281 and 293 bp in size.

The second-step PCR reaction was performed using 2 µL of the first-step PCR product. The reaction contained 12.5 µL of Taq DNA Polymerase Master Mix (Amplicon, Denmark), 1 µL of each Forward and Reverse primers (10 µM), and the final volume was made up to 25 µL with sterile water. The PCR reaction conditions included preliminary denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min and 35 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s, followed by final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR products were visualized by gel electrophoresis.

The quality of corneal samples was assessed in each DNA extract by amplifying specific primers targeting the human beta-globin gene in an additional PCR reaction29. The primers, including bGlob-F GGGTTGGCCAATCTACTCCC and bGlob-R CTGTCTCCACATGCCCAGTT, were designed to amplify 288 bp. Reaction mixtures of 25 µL volume were prepared containing 12.5 µL of Taq DNA Polymerase Master Mix (Amplicon, Denmark), 1 µL of each primer (10 µM), 17 µL of PCR-grade water, and 4 µL of template DNA. PCR conditions consisted of an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min; 35 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 59 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s; and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The detection of human DNA confirmed the presence of corneal material in the scrapings; the absence of human DNA amplicons suggested the amount of DNA was too low and could lead to the misdetection of Acanthamoeba.

The limit of detection of one-step PCR and nested PCR

The limit of detection (LOD) of one-step PCR and nested PCR was evaluated using the DNA of 105 to 1 cysts/reaction of Acanthamoeba T4 genotype. To this end, after culturing of Acanthamoeba on NNA covered with E. coli, the cysts were collected in 1 mL 1X PBS and counted using a Neubauer chamber. A 10-fold serial dilution was prepared to obtain 105 to 1 cysts/reaction. DNA was extracted from each dilution and subjected to one-step PCR and nested PCR to determine LOD.

Sequencing

To confirm the molecular results, eight amplicons, obtained with PCR and nested PCR, were selected randomly and sequenced with related forward primers on an automated sequencing platform. The sequences were aligned and compared with GenBank reference sequences using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST). At least 95% of the sequence must be identical to be considered the same genotype. Seven sequences from one-step PCR using JDP primers were characterized as T4 genotype, which was deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers PQ666791, PQ666792, PQ666793, MT820304, MT820305, PX326349, PX326350. The sequence of nested PCR amplicons was too short to determine the genotype, so for validation of the result, three sequences were deposited as Acanthamoeba sp. in the GenBank database under the accession numbers PQ661184-PQ661186.

Statistical analysis

In the absence of a single gold standard for the diagnosis of AK, in the present study, based on the study by Goh et al. (2017), the definition of “Definite AK” was considered as a reference standard to allow for the calculation of sensitivity and specificity. The “Definite AK” was diagnosed based on a positive result from one of the tests, including IVCM, cultures, PCR, and nested PCR, along with clinical manifestations and disease resolution following anti-Acanthamoeba therapy. The sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of each assay for the diagnosis of definite AK were calculated20.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS software version 26.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). Proportions were presented as percentages and mean ± standard deviation. Chi-square (χ2) and paired-sample t-tests were used to compare demographic, clinical data, and diagnosis test results in definite AK cases, with the significance level of P value < 0.05 for 2-tailed tests. The Cohen’s kappa coefficient (κ, lowercase Greek kappa) of agreement between the diagnostic tests was analyzed by GraphPad Prism 8.0 software, version 9. The k scores were interpreted as follows: 0–0.20.20 = no agreement; 0.21 to 0.39 = minimal agreement; 0.40 to 0.59 = weak agreement; 0.60 to 0.79 = moderate agreement; 0.80 to 0.90 = strong agreement; 0.91–1.00.91.00 = almost perfect agreement30.

Results

Patient demographics

Forty-two patients with clinical suspicion of Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK) were included in this study. The demographic and clinical characteristics of patients are summarized in Table 1. Out of these 42 patients, 27 (64.28%) were confirmed to have AK based on at least one positive diagnostic test, while 15 patients (35.71%) tested negative by all methods and were classified as non-AK. All AK-positive patients were also confirmed based on the expertise of clinicians, specific AK clinical manifestations, and response to anti-Acanthamoeba treatment.

In the AK group, the mean age of patients was 29.63 ± 8.78 years, ranging from 16 to 50 years. AK was more common in individuals younger than 40 (P < 0.05). The majority of AK patients were female (n = 21, 77.78%), while males accounted for 22.22% (n = 6) (P < 0.05).

AK was associated significantly with wearing contact lenses (P < 0.05). Among the AK group, 20 (74.07%) patients had a history of using contact lenses, of which 15 (55.6%) used soft lenses and 5 (18.51%) used hard lenses.

Regarding other risk factors of AK, 2 (7.4%) patients had a history of eye trauma, and 2 (7.4%) patients had been recently exposed to dust. Also, contact with contaminated freshwater and swimming in seawater were reported in two patients separately. Symptoms of keratitis developed in one patient (3.7%) after photorefractive keratectomy.

The majority of patients with clinically diagnosed AK presented with mildly reduced vision, severe eye pain, redness, and photophobia. Infiltration was reported in 10 (37.03%) patients (Fig. 1). Most patients (26 patients, 96.29%) suffered from unilateral keratitis, except for one (4.76%) patient who presented with bilateral eye involvement and a history of soft lens use (Table 1).

Diagnostic methods

IVCM images from the affected eyes of 42 patients were reviewed. The double-walled cysts with target-shaped, coffee-bean, and rod-shaped appearances were observed in 21 (77.78%) patients. The mean size of the cysts was 18.9 μm (range 10–39.6 μm). In IVCM-positive patients, trophozoites were observed as pear-shaped or irregularly wedge-shaped structures, some surrounded by a brilliant halo and some exhibiting fine pseudopodia-like extensions, with a mean size of 30.2 μm (range 19.2–55.6 μm). The other IVCM features of AK were keratoneuritis and the anterior stromal honeycomb pattern (Fig. 2). Among 27 AK patients, 10 (37%) were culture-positive, and the trophozoites and cysts were grown on non-nutritive agar medium (Fig. 3).

All the samples were positive for the human beta-globulin gene, demonstrating the good quality of corneal scrape samples. Regarding molecular diagnosis of AK, out of 27 samples, 17 (62.96%) were positive by one-step PCR. Figure 4A shows the agarose gel image of the PCR products (498 bp) of the 18S rRNA gene of Acanthamoeba amplified using JDP primers.

In the AK group, out of 27 samples, 26 (96.29%) were tested positive in the second round of nested PCR. As shown in Fig. 4B, a 293 bp PCR product corresponding to the 18S rRNA gene of Acanthamoeba was detected. All non-AK cases (n = 15) were negative with one-step PCR and nested PCR, indicating the specificity of primers.

The gel electrophoresis results of One-step PCR and nested PCR targeted 18S rRNA gene of Acanthamoeba in corneal samples of AK patients. (A) The PCR product of 498 bp using JDP primers. 1: positive control; 2–8 samples of AK patients; 9: Non-template control; (B) The nested PCR product of 293 bp using NJK primers, 1: positive control; 2–8 positive samples of AK patients; 9: Non-template control; M: 100 bp marker.

The limit of detection (LOD)

The limit of detection (LOD) of one-step PCR and nested PCR was determined using 105 to 1 cysts of Acanthamoeba. As shown in Fig. 5, the detection limit of one-step PCR was 10 cysts, whereas nested PCR was able to detect DNA from a single cyst/reaction, demonstrating its higher analytical sensitivity.

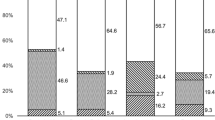

Sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of tests for the diagnosis of AK

Definite (confirmed) AK was considered the reference standard for calculating the specificity and sensitivity of diagnostic tests, according to the previous study20. The “Definite AK” was diagnosed based on a positive result with one of the tests, including IVCM, cultures, PCR, and nested PCR, in combination with clinical manifestation and disease resolution with anti-Acanthamoeba therapy. Among 42 patients, 27 were confirmed to have AK, while the remaining 15 patients tested negative for all methods and were classified as non-AK. As shown in Table 2, among 27 confirmed AK cases, the number of positive results was 21 for IVCM, 10 for culture, 17 for one-step PCR, and 26 for nested PCR.

All culture-positive results (n = 10) were positive with IVCM, PCR, and nested PCR techniques. Nested PCR and PCR were positive in 17 samples, while nested PCR was positive in 9 samples with negative PCR. IVCM was negative in 6 samples that were positive by nested PCR. Out of 27 cases of definite AK, nested PCR was positive in 26 patients. It failed to diagnose one AK case, which was confirmed via IVCM.

The sensitivity of IVCM, culture, PCR, and nested PCR tests in diagnosing AK cases was 77.78%, 37.04%, 62.96%, and 96.3%, respectively. The specificity was 100% in all tests, and all non-AK cases were negative (Tables 2 and 3). Since none of the tests detected any false positives, the positive predictive values for all the tests were 100%. The negative predictive values of IVCM, culture, PCR, and nested PCR were 71.43% (50.04%−86.19%), 46.88% (30.87%−63.55%), 60% (40.74%−76.6%), and 93.75% (71.67%−99.68%), respectively. Overall, nested PCR demonstrated the highest sensitivity and negative predictive value among all the tests, whereas culture had the lowest, owing to its low detection rate in AK cases.

In the present study, the agreement of nested PCR with other diagnostic tests was assessed using Cohen’s kappa statistic. As shown in Table 3, the kappa values for nested PCR with IVCM, culture, and PCR were 0.66, 0.32, and 0.59, respectively. The results indicated the highest agreement of nested PCR with IVCM, and the lowest with culture.

Discussion

The diagnosis of AK, especially in the early stage of the disease, can present a significant challenge due to mixed or atypical clinical presentations31. Accordingly, in recent years, several attempts have been made to advance and develop accessible, rapid, and sensitive techniques for diagnosing microbial keratitis. In the present study, we designed nested PCR targeting Acanthamoeba and compared its performance to conventional techniques for diagnosing suspected cases of AK. Our study included 42 patients, 27 (64.28%) diagnosed with AK based on their clinical appearances and positivity in at least one diagnostic method. In our sample demographic, women were predominantly affected by AK, and AK incidence was significantly higher in those under 40 years, with a mean age of 29 years, which was similar to previous studies from the UK, Austria, New Zealand, and Australia32,33. Contact lenses, especially soft lenses, were the primary risk factor in AK patients. This is in agreement with several studies that have reported the prevalence of AK in young individuals and women with a history of wearing contact lenses20,34,35,36. Indeed, 80 to 96% of AK cases were associated with a history of using contact lenses37. Other predisposing factors reported in the non-contact lens wearers were trauma, exposure to dust, contaminated freshwater, seawater, and photorefractive keratectomy, which have also been reported in the literature38.

Our results demonstrated that 27 (64.28%) patients were positive with at least one diagnostic method. In descending order, the highest positive rate and specificity belonged to nested PCR, IVCM, PCR, and microbial culture, respectively. All methods were negative in non-AK patients, suggesting 100% specificity for each test. The positive predictive values for all the tests were 100% because there were no false positive reports. In descending order, the highest negative predictive values correspond to nested PCR, IVCM, PCR, and culture, respectively.

IVCM is a non-invasive method for rapidly diagnosing microbial agents in the patient’s cornea. It enables visualization of the entire cornea and deeper stromal layer inaccessible by superficial corneal scrapes. Several studies have demonstrated the high sensitivity of IVCM for diagnosing AK20,25,39. Tu et al. demonstrated that IVCM had a sensitivity of 90.6% to 92.9% and a specificity of 77.3% to 100%40. In another survey, IVCM showed a sensitivity of 88.2% and specificity of 98.2% for the diagnosis of AK39. Likewise, our results demonstrated that IVCM has a sensitivity and specificity of 77.78% and 100%, respectively. The positive and negative predictive values of IVCM were 100% and 71.43%, respectively, with 4 AK cases reported as false negatives. Several studies stated that the sensitivity and specificity of IVCM are strongly dependent on the trained and experienced operator and the higher resolution of the HRT III imaging system. In line with this, Hasu et al. analyzed 62 AK patients by IVCM, revealing that the sensitivity can range from 27.9% to 55.8%, and specificity can range from 42.1% to 84.2% depending on the experience of the operator in diagnosing microbial keratitis25. Furthermore, some disadvantages were reported, such as its high cost, low accessibility, need for a highly experienced operator, and lack of a standard for interpreting the images41. In addition, in some cases, false positive diagnoses can arise due to the similar morphology of Acanthamoeba cysts with corneal and inflammatory cells or the similarity of trophozoites to leukocytes and keratocytes in IVCM images25. False negatives can also result from inadequate imaging of all the layers of the cornea, as some patients can only tolerate IVCM imaging for a short time. Moreover, superficial plaques of ulcers can produce high refractivity in the IVCM image and reduce the contrast, making microbial detection difficult39. Additionally, IVCM seems to have lower sensitivity at the beginning of the disease when the number of amoebae and cysts is low41. Despite these drawbacks, IVCM is suggested as a superior method, unaffected by previous antibiotic therapy or sampling difficulties.

Culture of corneal scraping was previously recognized as the gold standard; however, several studies have reported the low sensitivity of the culture technique. In a study by Tu et al., culture showed a sensitivity of 52.8% and a specificity of 100%40. Moreover, it was reported that corneal culture is less reliable, with a sensitivity of 33.33% and a specificity of 100%20. Similarly, in the present study, culture was positive in 10 of 27 (37%) AK cases and exhibited a sensitivity and specificity of 37.04% (21.53%−55.77%) and 100% (79.61%−100%), respectively. Although the positive predictive value was 100%, the negative predictive value was 46.88%, leading to 17 false negative results. The non-viable or low number of amoebae and inadequate corneal scrape samples could be reasons for these false negative results. Moreover, in the late stage, due to amoeba penetration into the deeper corneal layers, the number of amoebae on the corneal surface reduces, resulting in false negative results7. Furthermore, antibiotic therapy and topical use of anesthetics, such as tetracaine 10%, can reduce amoeba viability, resulting in false negative culture findings42. Although culture is a simple, cheap, and accessible technique, its low sensitivity and prolonged incubation often delay diagnosis and treatment43. These results highlight that the microbial culture method alone cannot be used as a gold standard for AK diagnosis.

Molecular methods such as PCR have recently been introduced as a complementary test for the rapid diagnosis of AK. The 18S rRNA gene is an ideal target for diagnosis and genotyping due to the high copy number and nucleotide variation. JDP primers targeting the partial sequences of the 18S rRNA gene produce varying amplicon sizes (423 to 551 bp) based on the Acanthamoeba genotype44. Several studies have reported variable sensitivities for one-step PCR, ranging from 77% to 88%45,46. In another study, PCR sensitivity and specificity were 71.43% and 100%, respectively20. In the present study, PCR was positive in 17 of 27 (62.96%) AK patients. The negative predictive value was 60% due to 10 false negative results. The PCR results depend on the quality and quantity of corneal scraping, the number of amoebae in the specimen, and the stage of the disease. Moreover, false negative PCR results could be due to the inhibitory effect of topical agents applied before corneal scrapings47. Although PCR is more rapid and sensitive than microbial culture, false-negative results are still high.

In the current study, we designed inner primers (NJK) for nested PCR based on the highly conserved region of 18S rRNA sequences in the GenBank. Our result demonstrated that nested PCR was positive in 26 out of 27 (96.29%) definite AK and negative in all non-AK cases. Nested PCR reported a false negative result in just one AK case, possibly due to the small quantity of corneal scrape and Acanthamoeba DNA. Several documents confirmed the high sensitivity of nested PCR compared to one-step PCR in detecting scarce quantities of DNA in a small sample size23,48. In nested PCR, the sensitivity increases by re-amplifying the target sequence of a template previously enriched in the first PCR. Since the second set of primers amplifies regions internal to the regions of the first PCR, nonspecific sequences amplified in the first PCR are not re-amplified in the second PCR49. Moreover, the shorter amplification products used in nested PCR contribute to an increase in the successful amplification of DNA50. Likewise, nested PCR was more sensitive than one-step PCR in the present study. Seventeen definite AK samples were positive with both methods, and 9 negative samples with one-step PCR were correctly detected as positive by nested PCR. Dhivya et al. designed a semi-nested PCR (snPCR) to diagnose AK. PCR was applied for the first run, and A1 Forward primer and JDP2 Reverse primer were used for the second PCR. The snPCR amplicon was 120–160 bp at the 3’ end of the JDP region of 18S rRNA. They demonstrated that out of the 35 corneal scrapings, 11 were positive by the smear and/or culture and snPCR, and only three were positive by the PCR. The clinical sensitivity of the snPCR and PCR was 100% and 27%, respectively, when compared with the gold standard, smear, and/or culture51. Recently, Hsu et al. established a new nested PCR that was highly sensitive for genotyping. The free-living amoeba (FLA) primers amplified 1000 bp of 18S rRNA were used in outer PCR, and JDP primers produced the 450 bp fragment, which was applied for inner PCR. The nested PCR efficiently enhances the sensitivity of Acanthamoeba detection in water samples, which have a demonstrable dilutional effect and were underestimated by the PCR method52. Although the FLA primers contribute to obtaining a full sequence of the JDP region, which is appropriate for genotyping, using such a long sequence in the clinical setting has not been recommended. Bøggild et al. demonstrated that PCR using Nelson primers, which target a 229 bp region of 18S rRNA, had higher sensitivity (90%) compared to JDP primers amplifying a 490 bp fragment (65%)53. Similarly, in another study, PCR with Nelson primers exhibited a sensitivity of 90%, whereas JDP primers led to 81%51. These findings support the concept that amplification of shorter amplicons provides higher sensitivity than longer ones, which is valuable for detecting low-abundance DNA and fragmented DNA obtained from cysts or tissue samples54. In terms of genotyping, although using a shorter amplicon in nested PCR exhibited higher sensitivity for diagnosis, it failed to characterize the genotype. In contrast, using JDP primers is more appropriate for genotyping, as also revealed in the present study.

On the other hand, despite the high sensitivity of nested PCR, false negative results may still occur, especially in samples with PCR inhibitors, insufficient scraping, or low copy numbers of the DNA. Consequently, in the present study, the limit of detection (LOD) of molecular assays was also evaluated. The LOD of one-step PCR was 10 cysts per reaction, whereas that of nested-PCR was one cyst per reaction, indicating a higher sensitivity of nested PCR52. Regarding the specificity of molecular assays, all non-AK samples were negative, resulting in 100% specificity. It should also be noted that although nested PCR offers several benefits, such as speed, cost-effectiveness, portability, and efficiency, there is also the risk of environmental contamination and false positive results, which could be avoided by separating pre- and post-amplification areas22.

Overall, in the current study, nested PCR showed the highest positivity rate (96.29%) compared to PCR (62.96%), culture (37%), and IVCM (77.8%). Nested PCR exhibited the highest sensitivity among laboratory diagnosis tests and identified 26 out of 27 definite AK cases. The one false negative nested PCR result was identified as positive by IVCM, suggesting an advantage of using at least two diagnostic methods. Nested PCR displayed the highest agreement (Kappa = 0.667) with IVCM. Out of 27 AK, 21 (77.8%) were positive with both methods, and 6 samples were uniquely diagnosed as positive by nested PCR. Nested PCR was more sensitive than one-step PCR, and 9 samples that were negative with PCR were detected by nested PCR. The agreement between these methods was lower (Kappa = 0.590). The culture method displayed the lowest agreement with nested PCR (Kappa = 0.323) due to low sensitivity in detecting definite AK.

Here, nested PCR contributes to improving the sensitivity in the diagnosis of definite AK, suggesting the superiority of nested PCR in detecting low-abundance DNA in low quantities of corneal scrapes. On the other hand, IVCM, as a non-invasive method, is fundamental in diagnosing Acanthamoeba cysts in the cornea. However, in the early stage of AK, nested PCR could be more useful when patients have atypical symptoms and IVCM is false negative due to Acanthamoeba not appearing in its cyst form. Given the high sensitivity of nested PCR, it can be offered as a complementary tool for confirming the diagnosis of AK, particularly in the early stages, atypical clinical presentations, low organism load, and false-negative imaging results.

As highlighted in recent reviews, no single diagnostic test is considered entirely reliable on its own, and a multimodal approach combining clinical examination and treatment response is recommended31. Nested PCR is a highly sensitive and rapid tool for detecting Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK); nevertheless, it cannot cover all diagnostic features. Its sensitivity may be affected by PCR inhibitors present in corneal scrapes, particularly in patients who have been pretreated with antibiotics or corticosteroid eye drops. Although two-step amplification of nested PCR can partially mitigate the impact of inhibitors, high concentrations may still reduce its sensitivity55. Consequently, the results of molecular methods should be interpreted with caution in pretreated patients. Therefore, nested PCR can be considered as an adjunctive diagnostic tool, complementing clinical examination and other laboratory tests.

One of the limitations of the present study is the small sample size, which is reflected in the low incidence of Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK). Also, our analysis focused exclusively on confirmed AK cases to ensure reliability; as a result, the coinfection or polymicrobial keratitis cases were excluded from the present study. Further studies with large sample sizes, including coinfection keratitis, could provide more insight into the performance of molecular methods in AK diagnosis. Furthermore, although nested PCR is highly sensitive, its performance may be affected by PCR inhibitors such as prior topical treatments, highlighting the need to explore their effect on nested PCR performance in future studies.

Conclusion

Nested PCR is a reliable and efficient diagnostic tool for AK, offering superior sensitivity compared to conventional methods. Its combination with IVCM provides the most effective diagnostic approach, ensuring higher detection rates. Given its affordability and suitability for resource-limited settings, nested PCR serves as a valuable complementary method, particularly when IVCM is unavailable and other diagnostic tests, such as culture and one-step PCR, fail to confirm the diagnosis. Its high specificity and predictive value further establish it as a robust alternative for improving early and accurate detection of AK.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript. Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the GenBank database with accession numbers PQ666791, PQ666792, PQ666793, MT820304, MT820305, PX326349, PX326350, and PQ661184-PQ661186.

References

de Lacerda, A. G. & Lira, M. Acanthamoeba keratitis: a review of biology, pathophysiology and epidemiology. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 41, 116–135 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. The global epidemiology and clinical diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Journal Infect. Public. Health. 16(6), 841–52 (2023).

Hajialilo, E., Niyyati, M., Solaymani, M. & Rezaeian, M. Pathogenic free-living amoebae isolated from contact lenses of keratitis patients. Iran. J. Parasitol. 10, 541 (2015).

Szentmáry, N. et al. Acanthamoeba keratitis–Clinical signs, differential diagnosis and treatment. J. Curr. Ophthalmol. 31, 16–23 (2019).

Dart, J. K. G. et al. The orphan drug for Acanthamoeba keratitis (ODAK) trial: PHMB 0.08% (Polihexanide) and placebo versus PHMB 0.02% and Propamidine 0.1. Ophthalmology 131, 277–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2023.09.031 (2024).

Latifi, A. et al. Comparing cytotoxicity and efficacy of miltefosine and standard antimicrobial agents against Acanthamoeba trophozoites and cyst forms: an in vitro study. Acta Trop. 247, 107009 (2023).

Lorenzo-Morales, J., Khan, N. A. & Walochnik, J. An update on Acanthamoeba keratitis: diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment. Parasite 22, 10. https://doi.org/10.1051/parasite/2015010 (2015).

Behnia, M. et al. In vitro activity of pentamidine isethionate against trophozoite and cyst of Acanthamoeba. Iran. J. Parasitol. 16, 560 (2021).

Shah, Y. S. et al. Delayed diagnoses of Acanthamoeba keratitis at a tertiary care medical centre. Acta Ophthalmol. 99, 916–921. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.14792 (2021).

Shareef, O. et al. A novel artificial intelligence model for diagnosing Acanthamoeba keratitis through confocal microscopy. Ocul. Surf. 34, 159–164 (2024).

Soleimani, M. et al. Clinical characteristics, predisposing factors, and management of Moraxella keratitis in a tertiary eye hospital. J. Ophthalmic Inflamm. Infect. 14, 36 (2024).

Cabrera-Aguas, M., Khoo, P. & Watson, S. L. Infectious keratitis: A review. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 50, 543–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/ceo.14113 (2022).

Soleimani, M., Tabatabaei, S. A., Bahadorifar, S., Mohammadi, A. & Asadigandomani, H. Unveiling the landscape of post-keratoplasty keratitis: a comprehensive epidemiological analysis in a tertiary center. Int. Ophthalmol. 44, 230 (2024).

Dart, J. K., Saw, V. P. & Kilvington, S. Acanthamoeba keratitis: diagnosis and treatment update 2009. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 148, 487–499e482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2009.06.009 (2009).

Yera, H. et al. PCR and culture for diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 105, 1302–1306 (2021).

Somani, S. N., Ronquillo, Y. & Moshirfar, M. Acanthamoeba keratitis. (2019).

Wang, Y. E. et al. Role of in vivo confocal microscopy in the diagnosis of infectious keratitis. Int. Ophthalmol. 39, 2865–2874. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10792-019-01134-4 (2019).

Wang, Y. E. et al. Reduction of Acanthamoeba cyst density associated with treatment detected by in vivo confocal microscopy in Acanthamoeba keratitis. Cornea 38, 463–468. https://doi.org/10.1097/ico.0000000000001857 (2019).

Karsenti, N. et al. Development and validation of a real-time PCR assay for the detection of clinical Acanthamoebae. BMC Res. Notes 10, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-017-2666-x (2017).

Goh, J. W. et al. Comparison of in vivo confocal microscopy, PCR and culture of corneal scrapes in the diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Cornea 37, 480–485 (2018).

Hoffman, J. J. et al. Comparison of culture, confocal microscopy and PCR in routine hospital use for microbial keratitis diagnosis. Eye (Lond). 36, 2172–2178. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-021-01812-7 (2022).

Yang, S. & Rothman, R. E. PCR-based diagnostics for infectious diseases: uses, limitations, and future applications in acute-care settings. Lancet Infect. Dis. 4, 337–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(04)01044-8 (2004).

Badiee, P., Nejabat, M., Alborzi, A., Keshavarz, F. & Shakiba, E. Comparative study of gram stain, potassium hydroxide smear, culture and nested PCR in the diagnosis of fungal keratitis. Ophthalmic Res. 44, 251–256. https://doi.org/10.1159/000313988 (2010).

Tabatabaei, S. A. et al. The use of in vivo confocal microscopy to track treatment success in fungal keratitis and to differentiate between fusarium and Aspergillus keratitis. Int. Ophthalmol. 40, 483–491. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10792-019-01209-2 (2020).

Hau, S. C. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of microbial keratitis with in vivo scanning laser confocal microscopy. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 94, 982–987. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.2009.175083 (2010).

Latifi, A. et al. Chitosan nanoparticles improve the effectivity of miltefosine against Acanthamoeba. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 18, e0011976. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0011976 (2024).

Soleimani, M. et al. Management of refractory Acanthamoeba keratitis, two cases. Parasitol. Res. 120, 1121–1124 (2021).

Schroeder, J. M. et al. Use of subgenic 18S ribosomal DNA PCR and sequencing for genus and genotype identification of Acanthamoebae from humans with keratitis and from sewage sludge. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39, 1903–1911. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.39.5.1903-1911.2001 (2001).

Maubon, D. et al. A one-step multiplex PCR for Acanthamoeba keratitis diagnosis and quality samples control. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 53, 2866–2872. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.11-8587 (2012).

McHugh, M. L. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochemia Med. 22, 276–282 (2012).

Azzopardi, M. et al. Diagnosis of Acanthamoeba Keratitis: Past, Present and Future. Diagnostics (Basel) 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13162655 (2023).

Radford, C. F., Minassian, D. C. & Dart, J. K. Acanthamoeba keratitis in England and wales: incidence, outcome, and risk factors. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 86, 536–542. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.86.5.536 (2002).

Butler, T. K. et al. Six-year review of Acanthamoeba keratitis in new South Wales, australia: 1997–2002. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 33, 41–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-9071.2004.00911.x (2005).

Kanavi, M. R., Javadi, M., Yazdani, S. & Mirdehghanm, S. Sensitivity and specificity of confocal scan in the diagnosis of infectious keratitis. Cornea 26, 782–786 (2007).

Kowalski, R. P., Melan, M. A., Karenchak, L. M. & Mammen, A. Comparison of validated polymerase chain reaction and culture isolation for the routine detection of Acanthamoeba from ocular samples. Eye Contact Lens. 41, 341–343 (2015).

Heaselgrave, W., Hamad, A., Coles, S. & Hau, S. In vitro evaluation of the inhibitory effect of topical ophthalmic agents on Acanthamoeba viability. Translational Vis. Sci. Technol. 8, 17. https://doi.org/10.1167/tvst.8.5.17 (2019).

Höllhumer, R., Keay, L. & Watson, S. L. Acanthamoeba keratitis in australia: demographics, associated factors, presentation and outcomes: a 15-year case review. Eye (London England). 34, 725–732. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-019-0589-6 (2020).

Lipshiz, I., Man, O., Varssano, D., Lazar, M. & Loewenstein, A. Laser in situ keratomileusis following Acanthamoeba keratitis. J. Refractive Surg. (Thorofare N J. : 1995). 16, S251–252. https://doi.org/10.3928/1081-597x-20000302-11 (2000).

Chidambaram, J. D. et al. Prospective study of the diagnostic accuracy of the in vivo laser scanning confocal microscope for severe microbial keratitis. Ophthalmology 123, 2285–2293 (2016).

Tu, E. Y. et al. The relative value of confocal microscopy and superficial corneal scrapings in the diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Cornea 27, 764–772 (2008).

Kumar, R. L., Cruzat, A. & Hamrah, P. Current state of in vivo confocal microscopy in management of microbial keratitis. Semin. Ophthalmol. 25, 166–170. https://doi.org/10.3109/08820538.2010.518516 (2010).

Heaselgrave, W., Hamad, A., Coles, S. & Hau, S. In vitro evaluation of the inhibitory effect of topical ophthalmic agents on Acanthamoeba viability. Translational Vis. Sci. Technol. 8, 17–17 (2019).

Bharathi, M. J. et al. Microbiological diagnosis of infective keratitis: comparative evaluation of direct microscopy and culture results. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 90, 1271–1276 (2006).

Lehmann, O. J. et al. Polymerase chain reaction analysis of corneal epithelial and tear samples in the diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 39, 1261–1265 (1998).

Mathers, W. D. et al. Confirmation of confocal microscopy diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis using polymerase chain reaction analysis. Arch. Ophthalmol. 118, 178–183 (2000).

Yera, H. et al. Comparison of PCR, microscopic examination and culture for the early diagnosis and characterization of Acanthamoeba isolates from ocular infections. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Diseases: Official Publication Eur. Soc. Clin. Microbiol. 26, 221–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-007-0268-6 (2007).

Thompson, P. P., Kowalski, R. P., Shanks, R. M. & Gordon, Y. J. Validation of real-time PCR for laboratory diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46, 3232–3236 (2008).

Bao, J. et al. Development of a nested PCR assay for specific detection of Metschnikowia bicuspidata infecting eriocheir sinensis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 12, 930585. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2022.930585 (2022).

Green, M. R. & Sambrook, J. Nested Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). Cold Spring Harbor protocols (2019). https://doi.org/10.1101/pdb.prot095182 (2019).

Cowley, J. A. et al. TaqMan real-time and conventional nested PCR tests specific to yellow head virus genotype 7 (YHV7) identified in giant tiger shrimp in Australia. J. Virol. Methods. 273, 113689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jviromet.2019.113689 (2019).

Dhivya, S. et al. Comparison of a novel semi-nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with a uniplex PCR for the detection of Acanthamoeba genome in corneal scrapings. Parasitol. Res. 100, 1303–1309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-006-0413-7 (2007).

Hsu, T. K. et al. Efficient nested-PCR-based method development for detection and genotype identification of Acanthamoeba from a small volume of aquatic environmental sample. Sci. Rep. 11, 21740 (2021).

Boggild, A. K., Martin, D. S., Lee, T. Y., Yu, B. & Low, D. E. Laboratory diagnosis of amoebic keratitis: comparison of four diagnostic methods for different types of clinical specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47, 1314–1318 (2009).

Wai, H. A. et al. Short amplicon reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction detects aberrant splicing in genes with low expression in blood missed by ribonucleic acid sequencing analysis for clinical diagnosis. Hum. Mutat. 43, 963–970 (2022).

Schrader, C., Schielke, A., Ellerbroek, L. & Johne, R. PCR inhibitors - occurrence, properties and removal. J. Appl. Microbiol. 113, 1014–1026. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2012.05384.x (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their appreciation to Mrs. Fatemeh Tarighi, Mrs Samimi, Dr. Behnaz Akhoundi, and Ms Zahra Kakooei for their cooperation.

Funding

The study was supported by the Center for Research of Endemic Parasites of Iran (CREPI), Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Grant Number: 98-02-160-42948).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.K.: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation. A.L.: Writing –original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. M.M.: Formal analysis, Data curation. M.A.: Methodology, Data curation. A.M.: Methodology, Data curation. H.A.: Methodology, Data curation. M.R.: Supervision. N.A.: Data curation. M.K.: Methodology. K.P.: Writing – review & editing. S.I.: Methodology. F.G.: Formal analysis, E.K.: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Supervision. M.S.: Validation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

Approvals for this study were obtained from the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (code number: IR.TUMS.SPH.REC.1398.182). Samples were collected upon informing patients about the scope of this study and signing the informed consent form.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khaksar, S., Latifi, A., Mohebali, M. et al. Nested PCR as a superior diagnostic method for Acanthamoeba keratitis compared to conventional techniques. Sci Rep 16, 3502 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32716-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32716-1