Abstract

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is a cornerstone treatment for coronary artery disease, yet accurate prediction of long-term mortality remains a critical challenge due to the complex interplay of risk factors. Existing prognostic models rely predominantly on structured clinical data, overlooking the rich, nuanced information embedded in diagnostic imaging and procedural narratives. To address this gap, we present a novel multimodal machine learning framework that integrates coronary angiography video, unstructured procedural text, and structured clinical variables to predict 5-year all-cause mortality. Utilizing a large real-world cohort of 10,353 patients, we extracted visual embeddings via CLIP, textual embeddings via BioBERT, and structured features to construct a unified patient representation. Our trimodal LightGBM model achieved an AUC-ROC of 0.814, significantly outperforming single- and dual-modality baselines (\(p<0.01\)). SHAP-based analysis revealed that unstructured data captured complementary prognostic signals, while structured variables provided concentrated predictive strength. This study demonstrates the prognostic value of integrating heterogeneous data sources and establishes a robust, explainable foundation for precision medicine in interventional cardiology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is a minimally invasive procedure used to relieve narrowing or blockage of the coronary arteries and restore blood flow, typically by inflating a balloon and deploying a stent in the affected artery1. In recent years, PCI has fundamentally transformed the management of coronary artery disease, reducing mortality and improving patient quality of life. However, despite these advances, the identification of patients at risk of mortality after PCI remains a significant clinical challenge2,3.

This challenge is magnified by the sheer scale of the procedure and the persistent risk of adverse outcomes. PCI represents the cornerstone of revascularization therapy, with millions of procedures performed globally each year4. However, large-scale registry data indicate that post-discharge mortality rates remain alarmingly high in high-risk subsets, underscoring that procedural success does not equate to long-term survival5.

This discrepancy requires a shift in focus from immediate outcomes to long-term prognosis. Clinical evidence suggests that late outcomes are increasingly driven by the progression of native atherosclerotic disease in non-culprit lesions rather than stent failure6. Consequently, the 5-year period serves as a pivotal window for evaluating the efficacy of secondary prevention, extending beyond the immediate post-procedural period. As highlighted in landmark follow-up studies like the SYNTAX trial, the divergence in clinical outcomes necessitates extended monitoring to capture the true prognostic trajectory7. Therefore, accurate prediction of 5-year all-cause mortality is essential to identify patients who require aggressive risk factor modification.

A fundamental limitation of current risk prediction approaches is their reliance on conventional risk scores or regression models8. However, these traditional methods often impose linear and additive assumptions, which can obscure complex, nonlinear relationships between risk factors and outcomes9,10,11.Consequently, these methods neglect the wealth of nuanced, prognostic information embedded within the angiographic images and the procedural reports. This represents a significant missed opportunity, as angiographic images capture complex anatomical details that are difficult to quantify manually, while procedural reports contain critical qualitative observations that extend beyond structured data fields. The increasing availability of these multimodal data presents an unprecedented opportunity to move beyond traditional risk factors and create more individualized risk profiles for long-term patient management12,13.

To address these limitations, we propose a multimodal machine learning (ML) framework that integrates (1) visual data from coronary angiography imaging, (2) unstructured procedural text reports, and (3) structured tabular clinical data to predict 5-year all-cause mortality after PCI. We chose tree-based ensemble algorithms for this task as they are ideally suited to the challenge. These techniques, such as LightGBM, are designed to learn high-order, nonlinear interactions from heterogeneous datasets without strong distributional assumptions. For instance, gradient-boosting trees have already demonstrated superior performance over traditional logistic regression for post-PCI mortality prediction by capturing complex threshold effects in clinical variables14. Furthermore, their outputs can be interpreted using post hoc explainability methods like SHAP, providing valuable insights into the model’s decision-making process15.

Our goal is to improve predictive performance of post-PCI mortality compared to single-modality models. We developed and evaluated four ML models (XGBoost, CatBoost, LightGBM and Random Forest) using a real–world cohort and analyzed feature contributions across modalities.

Related works

Traditionally, post-PCI risk assessment has relied on scoring systems such as the ACEF (Age, Creatinine, Ejection Fraction)16. While these scores provide a standardized baseline, they are inherently limited by their assumption of linear relationships between risk factors and outcomes. To address this, recent studies have applied machine learning (ML) to structured electronic health record (EHR) data. Liu et al.8 demonstrated the effectiveness of gradient-boosting algorithms in large clinical datasets, achieving robust predictive performance through the comprehensive engineering of structured data elements. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Zaka et al.17 further corroborated that ML models outperform conventional risk scores. However, the reviewed studies were predominantly limited by their exclusive reliance on structured data, failing to incorporate imaging or unstructured text data that are routinely available in clinical practice. This limitation represents a significant underuse of the rich phenotypic information present in modern healthcare settings.

Recent advances in multimodal learning have shown considerable promise in various clinical domains. Lin et al.12 successfully integrated clinical parameters with imaging data for the prediction of short-term mortality in intensive care units, while Dipaola et al.13 combined clinical and textual data for the prediction of the outcome of COVID-19. Within the cardiovascular domain, a recent review by Yang et al.18 highlighted the potential of fusing cardiac imaging with EHRs to advance care. Specifically for post-PCI prognosis, Bhattacharya et al.19 demonstrated that a deep fusion model integrating ECG time-series and structured clinical data outperformed unimodal baselines in predicting 6-month adverse outcomes.

Despite these advancements, significant research gaps remain. First, existing post-PCI multimodal studies, such as Bhattacharya et al., are typically limited to dual-modal approaches (e.g., signal and tabular) and do not incorporate diagnostic angiography videos or procedural text reports. Second, the prediction horizons are often restricted to short-term endpoints, such as in-hospital or 6-month mortality, leaving the critical 5-year period for secondary prevention unexplored.

The present study addresses these limitations by developing a comprehensive trimodal framework that integrates angiographic images, procedural text reports, and structured clinical data to predict 5-year all-cause mortality after PCI. Unlike previous studies limited to short-term outcomes or partial data integration, our approach targets an extended prediction horizon that is clinically significant for late cardiovascular event management. By explicitly modeling the complementary contributions of each data modality and leveraging their synergistic predictive capacity, our approach represents a substantial advancement beyond existing single- or dual-modality methodologies, allowing for more precise and clinically relevant risk prediction in the post-PCI population.

Methods

Our multimodal approach combines visual, textual, and structured clinical data to predict 5-year all-cause mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention. Figure 1 illustrates the overall framework, detailing the data processing and integration pipeline for mortality prediction. The following subsections detail the data collection process and feature extraction methods for each modality.

Overview of the multimodal machine learning framework for predicting post-PCI mortality. The pipeline integrates three data modalities: (1) coronary angiographic images processed through CLIP visual encoder to generate 512-dimensional embeddings, (2) procedural text reports encoded using BioBERT to produce 768-dimensional representations, and (3) structured clinical data comprising 71 tabular features. Features from all modalities are concatenated into a unified 1351-dimensional vector and fed into gradient boosting models for mortality prediction.

Data collection

The patient selection process is illustrated in Fig. 2. We initially screened 25,000 patients who underwent coronary revascularization at Asan Medical Center between January 2003 and December 2018. To create the study cohort, we first excluded patients who underwent Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG) instead of PCI. Subsequently, to ensure a complete 5-year follow-up period for all subjects, we only included patients who received their intervention on or before December 31, 2014. After applying these criteria, a total of 10,353 patients were included in the final analysis. During this period, 1204 patients died while 9149 patients survived. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center (IRB No. 20230186). Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the study cohort, stratified by 5-year mortality.

For each patient, we obtained three complementary data modalities: (1) coronary angiographic images in DICOM format, with a mean of 15 imaging sequences per patient captured from multiple projections, (2) procedure reports dictated immediately after the intervention and stored as free text narratives, and (3) structured clinical data consisting of 71 routinely recorded variables.

Patient inclusion flowchart. From an initial cohort of 25,000 patients who underwent coronary revascularization at Asan Medical Center between January 2003 and December 2018, patients undergoing CABG were excluded, and only those with intervention before December 31, 2014 were included to ensure complete 5-year follow-up, resulting in 10,353 patients in the final analysis.

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics for the unstructured data modalities of the cohort. These statistics characterize coronary angiography videos by the number of frames before and after key-frame selection, and the reports by their length in both the word count and token count.

Multimodal feature extraction

We constructed a comprehensive feature set for each patient by extracting information from three distinct data modalities: visual angiographic data, textual procedural reports, and structured clinical data. The following sections detail the extraction methodology for each modality. To ensure optimal feature representation for each modality, we conducted preliminary experiments comparing various architectures. These comparisons, detailed in Supplementary Table S1, informed our final selection of feature extraction models.

Visual feature extraction

For each patient, we obtained coronary angiographic videos taken during PCI procedures. On average, 15 angiographic sequences (512 \(\times\) 512 px, 15 fps) per patient were captured, each sequence varying in length and capturing coronary arteries from different anatomical views under contrast injection.

Processing every frame from these sequences would result in prohibitively high computational costs. Previous studies on large-scale video analysis have proposed key frame extraction as an effective strategy to reduce redundancy and improve efficiency in processing high-volume visual data20. So we used an internal model to automatically identify key frames that best represent each major coronary artery. The selector assigns a vessel-visibility score to each frame and retains only those with clearly opacified coronary anatomy, reducing the frame count by approximately 90 % while preserving diagnostic information.

The selected representative frames were fed into the CLIP (Contrastive Language Image Pretraining) model21 with a Vision Transformer backbone (ViT-B/32). CLIP is a model trained on hundreds of millions of image-text pairs and produces a 512-dimensional representation for an input image. Each representative angiographic frame was fed through CLIP’s image encoder to obtain a corresponding 512-dimensional feature vector.

Since patients had varying numbers of representative frames corresponding to their individual coronary anatomy and procedural complexity, we needed a standardized approach to create features at the patient level. For patients with multiple representative frames, we compute the element-wise average of their frame embeddings to yield a single consolidated visual feature vector per patient. This averaging approach condenses the rich visual information of the coronary anatomy into a compact numerical form suitable for machine learning.

Textual feature extraction

Following each PCI procedure, interventional cardiologists write reports documenting coronary anatomy, descriptions of lesions, devices used, and any complications or notable events. We collect PCI reports for each patient as unstructured text data. These reports contain valuable contextual information, such as descriptions of complex bifurcation lesion or no-reflow phenomenon, that may not be fully captured by structured variables.

We preprocessed each report with a multi-step preprocessing pipeline based on standard practices in clinical natural language processing22. The initial step involved the removal of irrelevance sections, where we used a rule-based approach with regular expressions to programmatically delete report headers containing metadata such as operator names, as well as patient identifiers to ensure de-indentification. Subsequently, we performed medical terminology normalization. This included abbreviation resolution, for which we developed a custom dictionary to expand common cardiovascular abbreviations to their full terms (e.g., [SPSVERBc1SPS] was converted to [SPSVERBc2SPS]). It also involved the standardization of vessel and condition synonyms, where a manually curated mapping file was used to convert lexical variations of the same clinical concept to a single, canonical term (e.g., both [SPSVERBc3SPS] and [SPSVERBc4SPS] were mapped to [SPSVERBc3SPS]). Finally, the normalized text was converted to lowercase to ensure consistency before being passed to the BioBERT encoder.

Cleaned reports were encoded into a fixed-length numerical representation using BioBERT23, a BERT-based transformer model specifically pre-trained in the biomedical and clinical literature. We used the frozen BioBERT base model to generate a 768-dimensional document embedding. This frozen-embedding strategy is consistent with prior work showing robust performance of BioBERT on cardiovascular note classification without task-specific tuning24. We took the output vector corresponding to the !‘blockMath?‘CLS!‘/blockMath?‘ token from the final layer of BioBERT as an aggregate representation of the entire report. This approach effectively captures the semantic content and clinical context of each procedure note.

Structured feature extraction

We extracted 71 structured clinical features for each patient from a registry within our institution. All variables represent the patient’s baseline status, defined as data recorded at the time of the index PCI procedure or during the index hospitalization. These features include demographics of the patient (age, sex, body mass index), laboratory values and vital signs (serum creatinine, left ventricular ejection fraction), cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes status, smoking status, hyperlipidemia), medical history and comorbidities (history of myocardial infarction, previous stroke, previous PCI or CABG, heart failure, chronic kidney disease, COPD), and angiographic findings such as the number of vessels with significant stenosis.

Standard preprocessing was applied to the tabular data prior to modeling. The level of missingness was overall low. A detailed summary of the missing values for all variables before imputation is provided in the Supplementary Table 1. Missing values in continuous variables were imputed using the median values, while categorical variables were imputed with the mode values. Continuous features were normalized using min–max scaling to a range of 0–1 and categorical features were encoded one-hot as appropriate. The final tabular feature vector comprised 71 dimensions per patient.

Multimodal feature fusion

After extracting feature vectors from each modality, we concatenated the vectors into a single unified representation per patient. Specifically, we join the 512-dimensional visual, 768-dimensional text and 71-dimensional tabular feature vectors end-to-end, resulting in a combined feature vector of 1351 dimensions for each patient. This early fusion approach enables uniform treatment of all modalities within a single feature space suitable for machine learning classification. We selected gradient-boosting tree models for classification due to their demonstrated effectiveness in structured data and robustness to mixed feature types without extensive preprocessing requirements. Four ensemble tree algorithms were trained and compared: XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost, and Random Forest. These algorithms naturally accommodate both numerical and categorical features, while maintaining robustness to varying feature scales.

Model training was performed to predict the binary outcome of mortality after PCI. Among the algorithms, LightGBM shows the best performance in preliminary experiments, so we selected it as our primary model for further analysis. LightGBM is a gradient-boosting framework that optimizes tree growth and handles large feature sets efficiently. It also provides measures of feature importance, which we leveraged for model interpretation. Our LightGBM was trained with a learning rate of 0.05, 31 leaves per tree, 500 boosting rounds, and early stopping after 50 rounds without AUROC improvement. To effectively address the inherent class imbalance in our mortality prediction task, we utilized cost-sensitive learning within LightGBM by setting the scale pos weight parameter.

To ensure reliability of our performance estimates, we performed 5-fold cross-validation on the training data. The training set was stratified by outcome to preserve class balance in each fold. The model was trained from scratch for each combination of folds and we verified consistency across folds.

Experiment results

Evaluation metrics

We evaluated the performance of the model using a combination of discrimination, calibration, and clinical utility metrics. For discrimination, we primarily report the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC-ROC) and the macro averaged F1 score. AUC-ROC summarizes the model’s ability to distinguish between survivors and non-survivors across all possible thresholds, and is robust to class imbalance25. Given the positive-class prevalence of 11.6%, we also report the area under the precision–recall curve (PR-AUC), which is more informative for imbalanced datasets26.

Macro F1 is the harmonic mean of precision and recall computed per class and averaged equally across classes, ensuring that performance on the minority class (death) is not overshadowed by the majority class (survivors). This choice prioritizes sensitivity to clinically critical but rare adverse outcomes.

In addition to discrimination, we evaluated probability calibration using the Brier score, expected calibration error (ECE)27, and reliability diagrams. Well-calibrated probabilities are essential if predicted risks are to be used in clinical decision making.

Finally, we assessed the net clinical benefit using the Decision Curve Analysis (DCA)28, which compares utility of the model to the ’treat all’ and ’treat none’ strategies in a range of clinically relevant risk thresholds (5–20%). This combination of metrics allows for a comprehensive evaluation of both statistical performance and practical utility.

Model selection

To Select the best performing model and ensure a robust evaluation, we conducted a 5-fold cross validation for all classifiers. For a fair comparison, we included a baseline model based on the ACEF score16(age, creatinine, and ejection fraction), traditionally used to stratify patients into qualitive risk categories such as low, intermediate, and high risk. We calculated the continuous ACEF score for each patient and fitted a logistic regression model using this score as the sole predictor. This baseline and all machine learning models were evaluated using identical data splits. Table 3 shows the performance of four models in the test set, all using identical fused input features.

The results demonstrate that the gradient-boosted tree models substantially outperformed the Random Forest and ACEF score baselines. Among the evaluated models, LightGBM achieved the best performance across all primary metrics, with a mean AUC-ROC of 0.790, PR-AUC of 0.462, and F1-macro of 0.674. Therefore, LightGBM was selected for all subsequent analyzes.

Performance on imbalanced data and clinical relevance

Our dataset exhibits a notable class imbalance, with a 5-year post-PCI mortality prevalence of 13.2%. In such scenarios, macro F1-score might not fully capture the model’s ability to identify the minority class effectively. To provide a more granular understanding of our model’s performance on the minority class, we assessed its F1-score and precision specifically for this group. A hypothetical random classifier, given the 13.2% prevalence, would theoretically yield a minority class F1-score of 0.126 and a precision of 0.127.

In contrast, our LightGBM model significantly outperformed this random baseline, achieving a minority class F1-score of 0.385 and a precision of 0.410, as detailed in Table 4. This outcome represents a substantial threefold improvement in discriminative power for the minority class compared to random chance, clearly indicating a performance well beyond arbitrary prediction. Furthermore, the model exhibited a high specificity of 92.0%, which is essential for reliably identifying survivors and minimizing false positives, thereby reducing potential alarm fatigue in clinical settings. While the recall for the minority class was 36.3%, the precision of 41.0% is particularly meaningful. It implies that patients identified as high-risk by our model have a substantially elevated probability of actual mortality, representing a 3.2-fold lift over the baseline prevalence. This level of precision robustly supports the implementation of targeted secondary prevention strategies for individuals flagged as high-risk, enhancing the clinical utility and effectiveness of our risk stratification model.

Subgroup analysis for robustness and precision

To explicitly evaluate our model’s robustness and its capacity to provide actionable insights within these challenging cohorts, we stratified the study population. We first established a No Complex History group, encompassing patients without any prior PCI, CABG, or stroke. This group, representing a more general PCI population, served as our baseline for assessing fundamental prognostic signal capture.

In this No Complex History group, with a 5-year mortality of 12.17%, our model maintained a robust AUC of 0.738 (Precision 0.397), indicating its effectiveness in identifying subtle prognostic patterns from multimodal data even in the absence of overt high-risk clinical history. Furthermore, the model demonstrated an enhanced ability to precisely identify mortality risk within specific high-risk subgroups, as detailed in Table 5. For instance, in patients with a history of CABG, where the 5-year mortality rate was notably high at 28.95%, the model achieved a precision of 0.654. Similarly, for patients with a history of stroke, the precision was 0.504, both significantly higher than the baseline. This enhanced precision in complex clinical profiles underscores the model’s reliability in identifying those who require aggressive intervention, translating directly into improved long-term patient management strategies.

Ablation performance by modality

We evaluated the incremental value of each modality by training LightGBM classifiers on (i) one modality at a time, (ii) every pairwise combination, and (iii) all three modalities. Table 6 summarizes the discrimination achieved when LightGBM is supplied with each modality alone, every bimodal pair, or all three data sources. The metrics are calculated in the held-out fold-1 test split, 95 % confidence intervals are derived from 500 bootstrap resamples.

Combining all three modalities showed the strongest overall performance, with a AUC-ROC of 0.814, a PR-AUC of 0.472 and the highest F1macro. DeLong tests confirmed that this trimodal AUC-ROC was significantly higher than any single or bimodal alternative (\(P < 0.01\) versus the tabular-only model). Adding angiographic images (Tabular + Visual) or procedural reports (Tabular + Text) to the structured baseline increased AUC-ROC by 0.021 and 0.013, respectively, and increased PR-AUC to approximately 0.46, demonstrating that unstructured inputs provide complementary prognostic signal. In contrast, removing tabular variables (Visual + Text) caused a marked decline in all metrics (AUC-ROC 0.708), underscoring the indispensable role of conventional clinical risk factors.

Feature attribution analysis by modality

To quantify the relative contribution of each modality (visual, textual, and tabular) when used jointly in our multimodal classification model, we computed feature importance using SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values, following a group aggregation approach similar to that used in prior multimodal explainability research29. we first summed the absolute SHAP values of all features belonging to a given modality to obtain the raw sum contribution, which reflects the total influence of that modality on the model predictions. We then computed a mean normalized contribution by dividing the raw SHAP sum of each modality by its feature dimension (512 for visual, 768 for textual, 71 for tabular), thereby mitigating the dimension bias that arises when modalities have widely differing feature counts. Table 7 shows that the raw sum analysis indicates that the textual modality accounts for the highest proportion of variance in the model output (48.91%), followed by visual (27.98%) and tabular (23.11%). However, after dimension normalization, tabular features emerge as the most influential (73.33%), with textual (14.35%) and visual (12.32%) contributing more modestly. This divergence highlights the importance of correcting for feature dimensionality when comparing modalities, while high-dimensional embeddings (e.g., text and visual) can dominate in raw aggregation, per-feature normalization reveals that each tabular variable carries strong predictive weight.

These findings complement our earlier ablation results, where the full trimodal model outperformed any single-modality or bimodal configuration. Together, they suggest that all three modalities provide unique and complementary prognostic information: textual and visual embeddings add aggregate signal, while tabular variables deliver concentrated per-feature importance that is critical for accurate risk stratification.

Important predictors and clinical factors

We further examined which specific features were the most influential in the final multimodal model, focusing on the tabular modality due to its inherent interpretability. Using SHAP values for the LightGBM model, we rank features by their average impact on the output of the model. The main contributors included several clinical risk factors and patient characteristics. Figure 3 highlights the features of the tabular data by their importance in SHAP. The highest ranking predictors were height (Ht.), ejection fraction (EF), and female sex (Sex\(\vphantom{0}_F\)). Creatinine ranked fourth, while age was seventh. Other variables in the top ten included hyperlipidemia status, the extent of coronary disease, smoking status, diabetes status, and body mass index (BMI).

Notably, EF, creatinine, and age correspond to the well-established ACEF risk score widely used by interventional cardiologists to estimate rapid mortality risk. Their prominence in our SHAP analysis is consistent with established clinical evidence that impaired cardiac function, renal dysfunction, and advanced age are strong predictors of post-PCI mortality.

SHAP summary plot ranking tabular features in the multimodal model. Top features include Ht. (Height), EF (Ejection Fraction), and Sex_F; other important predictors include Creatinine, EXT_DISEASE_1VD, and Age. Colors denote feature value (blue: low, magenta: high); positive SHAP values increase predicted risk.

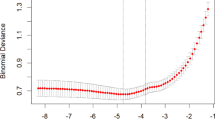

Model calibration and decision-curve analysis

Figure 4 compares the reliability of the uncalibrated raw probabilities with those obtained after the Platt scaling. Platt calibration reduced the Brier score from 0.099 to 0.078 and the 10-bin expected calibration error (ECE) from 0.107 to 0.041. The calibration slope improved from 0.70 to 0.93 and the intercept from –1.37 to –0.60, indicating attenuation of overall overprediction and better alignment of predicted and observed risks while preserving discrimination (AUROC unchanged at 0.814).

Across risk thresholds of 5 to 20 %, the Platt scaled model provided a greater net benefit than the raw model and both default strategies (treat-all, treat-none) (Fig. 5). For example, at a threshold 10 %, the Platt scaled model achieves a net benefit of 0.055, while treating all patients yields a negative benefit (–0.006) and treating none yields zero. Thus, using the calibrated model would avoid unnecessary follow-up in low-risk patients while capturing more true events among those at high risk.

Discussion

In this study, we developed a multimodal machine learning model that integrates angiographic images, procedural text reports, and structured clinical variables to predict 5-year all-cause mortality after PCI. The trimodal LightGBM model achieved the highest discrimination among all tested configurations (AUC-ROC 0.814, PR-AUC 0.472, macro-F1 0.682), significantly outperforming any single-modality or bimodal alternative. These results confirm that each modality provides complementary prognostic information, and that their integration yields the most accurate long-term risk prediction.

The use of a binary classification framework to first establish the foundational evidence that our specific multimodal approach, integrating dynamic angiographic video, procedural text, and structured data, is superior for long-term PCI prognosis. By simplifying the prediction task to a fixed 5-year endpoint, our ablation study shows that the trimodal model significantly outperforms all unimodal and bimodal configurations. Having demonstrated the value of this data fusion, the simpler framework facilitated an interpretable analysis via SHAP. This allowed us to move beyond prediction to explanation, revealing for the first time a key mechanism of how these heterogeneous data sources contribute to risk.

The modality level SHAP analysis offers further insight into the model’s decision-making. When absolute SHAP values were summed without adjustment, the textual modality appeared to contribute the largest share (48.91%), followed by visual (27.98%) and tabular (23.11%) features. However, after normalizing by feature dimensionality, the tabular modality accounted for 73.33% of the contribution, suggesting strong predictive value per variable despite its lower aggregate dimensionality. This divergence underscores the importance of correcting for dimension bias when comparing heterogeneous feature sets, as high-dimensional embeddings can otherwise appear disproportionately influential.

Feature-level interpretation of the tabular modality further supports the clinical credibility of the model. The top predictors–height, ejection fraction, and female sex–were accompanied by creatinine and age, which together form the ACEF risk score widely used in interventional cardiology. This alignment with established prognostic markers, while also integrating novel signals from unstructured modalities, strengthens confidence in the model’s validity.

Theoretical and practical implications

The design of our proposed framework offers significant implications for computational, mathematical, and biological theories in cardiovascular medicine.

From a computational and mathematical perspective, our findings demonstrate the efficacy of a modular fusion strategy in clinical settings. While end-to-end deep learning is a powerful paradigm, our results validate a resource-efficient theory of fusion that high-performance risk stratification can be achieved by decoupling feature extraction via pre-trained semantic alignment from classification. Mathematically, this approach leverages the specific strength of gradient boosting in optimizing decision boundaries within heterogeneous feature spaces. This suggests that for datasets of this magnitude, utilizing distinct, pre-trained semantic manifolds followed by a robust tabular classifier serves as a highly effective alternative to the complexity and potential overfitting risks associated with training massive end-to-end multimodal networks from scratch.

From a biological perspective, the superior performance of our trimodal model reinforces the theory of systemic atherosclerosis. This theoretical framework posits that post-PCI mortality is not determined solely by the local stented lesion (visual modality) or immediate procedural success (textual modality), but by the complex interplay of diffuse vascular burden and systemic metabolic risk factors (tabular modality). Our model provides empirical evidence for this theory, demonstrating that prognostic signals are distributed across diverse biological phenotypes rather than isolated in a single data type. This supports a holistic definition of high-risk patients, shifting the focus from localized pathology to a systemic understanding of disease progression.

Beyond these theoretical contributions, this framework is designed as a practical Clinical Decision Support System (CDSS) capable of benefiting human healthcare in real-time. Regarding its real-time deployment strategy, the proposed system is designed to be lightweight and modular, facilitating seamless integration into existing Electronic Medical Record (EMR) workflows. Unlike computationally expensive generative models, our discriminative framework allows the system to automatically retrieve stored angiographic videos, procedural notes, and tabular laboratory results upon a patient’s discharge to generate a risk score within seconds, without requiring manual data entry or dedicated GPU clusters.

The deployment of this tool translates into two tangible benefits for healthcare. First, it enables precision secondary prevention. By accurately identifying patients with a high 5-year mortality risk who might otherwise be overlooked by traditional scores, clinicians are empowered to initiate targeted interventions, such as personalized lipid-lowering therapies or prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy, specifically for this high-risk subgroup. Second, the model facilitates significant resource optimization. With its high specificity, the model reliably identifies low-risk patients who can safely undergo standard, less intensive follow-up protocols, thereby reducing unnecessary hospital visits and associated healthcare costs. Ultimately, this transforms the model from a mere binary classifier into an active agent for life-saving intervention and efficient allocation of valuable healthcare resources.

Limitations and future works

Our study has several important limitations. First, the study was conducted at a single tertiary center, which may limit generalizability due to center-specific practices and patient characteristics. While the dataset is large and clinically heterogeneous, external validation on multi-center cohorts will be necessary to confirm robustness. Second, our binary classification approach is a simplification of the underlying time-to-event problem and does not capture the temporal dynamics of risk.Third, although SHAP based group aggregation is a widely used and theoretically grounded method for attributing importance to modalities, it remains a correlational measure and does not prove causal influence; future work could incorporate counterfactual or perturbation-based approaches to complement SHAP. Fourth, our fusion strategy used early concatenation with gradient-boosted trees. While effective, this approach may not fully capture cross-modal interactions. transformer based or attention-driven fusion architectures could be explored to model richer dependencies. Finally, although we report group level feature importance, case level interpretability remains limited. developing clinically interpretable, patient-specific explanations will be essential for adoption.

In summary, this work demonstrates that integrating complementary information from structured clinical variables, angiographic imaging, and procedural text substantially improves long-term mortality prediction after PCI. The findings are consistent with prior multimodal explainability research and highlight both the aggregate value of high-dimensional unstructured data and the concentrated per-variable importance of structured clinical features. By addressing the noted limitations in future studies particularly through external validation, applying this validated multimodal framework to survival models, exploring advanced fusion strategies, and enhancing interpretability, this approach could form the basis of a robust, explainable decision support tool for interventional cardiology.

Conclusion

We presented a multimodal machine learning approach that integrates coronary angiography images, procedural text reports, and structured clinical data to predict the risk of mortality after PCI. By fusing data sources, we achieved significantly higher discrimination than any single- or dual-modality configuration.

Beyond improved accuracy, the modality-level SHAP analysis and feature-level interpretation provide clinically relevant insights, revealing that unstructured imaging and text data capture aggregate prognostic signals, while structured clinical variables deliver concentrated per feature predictive value. These findings highlight the potential of explainable multimodal AI to augment, rather than replace, existing clinical risk scores.

Future work will focus on external multi-center validation to confirm generalizability, the exploration of advanced fusion architectures to better capture cross-modal interactions, and the development of patient-specific explanations to enhance clinical trust and adoption. Ultimately, the proposed approach could be integrated into routine post-PCI care pathways, enabling data-driven, individualized risk stratification and supporting timely interventions to improve long-term patient outcomes.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the sensitive nature of the health information and the requirement for Institutional Review Board (IRB) supervision but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Balla, S. & Nair, C.K. Percutaneous coronary intervention, in StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing, 2023, accessed 19 March (2025). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556123/

Brennan, J. M. et al. Predicting in-hospital mortality in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Am. Heart J. 241, 20–29 (2021).

Peterson, E. D. et al. Contemporary mortality risk prediction for percutaneous coronary intervention: Results from 588,398 procedures in the national cardiovascular data registry. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 55(18), 1923–1932 (2010).

Virani, S. S. et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2021 update: A report from the american heart association. Circulation 143(8), 254–743 (2021).

Yeh, R. W. et al. Population trends in percutaneous coronary intervention, 2011 through 2014. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 65(20), 2274–2275 (2015).

Stone, G. W. et al. A prospective natural-history study of coronary atherosclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 364(3), 226–235 (2011).

Mohr, F. W. et al. Coronary artery bypass graft surgery versus percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with three-vessel disease and left main coronary artery disease: 5-year follow-up of the randomised, clinical syntax trial. The Lancet 381(9867), 629–638 (2013).

Liu, S. et al. Machine learning-based long-term outcome prediction in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Cardiovasc. Diagnosis Therapy 11(3), 736–743. https://doi.org/10.21037/cdt-21-37 (2021).

Sun, Y. Q. et al. Body mass index and all cause mortality in hunt and UK biobank studies: Linear and non-linear mendelian randomisation analyses. BMJ 364, 1042. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l1042 (2019).

Aune, D. et al. Bmi and all cause mortality: Systematic review and non-linear dose-response meta-analysis of 230 cohort studies with 374 million deaths among 303 million participants. BMJ 353, 2156. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i2156 (2016).

Chen, J., Wu, K., Lin, Y., Huang, M. & Xie, S. Association of triglyceride glucose index with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the general population. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22(1), 320. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-023-02054-5 (2023).

Lin, J. et al. Development and validation of multimodal models to predict the 30-day mortality of icu patients based on clinical parameters and chest x-rays. J. Imaging Inform. Med. 37(4), 1312–1322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10278-024-01066-1 (2024).

Dipaola, F. et al. Multimodal deep learning for covid-19 prognosis prediction in the emergency department: a bi-centric study. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 10868. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-37512-3 (2023).

Hosseini, K. et al. Machine learning prediction of one-year mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention in acute coronary syndrome patients. Int. J. Cardiol. 409, 132191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2024.132191 (2024).

Liu, T., Krentz, A. J., Lu, L. & Curcin, V. Machine learning based prediction models for cardiovascular disease risk using electronic health records data: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Heart J. Digital Health 6(1), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjdh/ztae080 (2024).

Wykrzykowska, J. J. et al. Value of the age, creatinine, and ejection fraction (ACEF) score in assessing risk in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions in the ‘all-comers’ leaders trial. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 4(1), 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.110.958389 (2011).

Zaka, A. et al. Machine-learning approaches for risk prediction after percutaneous coronary intervention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Heart J. Digit. Health 6(1), 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjdh/ztae074 (2024).

Yang, C. et al. Utilizing multimodal artificial intelligence to advance cardiovascular care. Precis. Clin. Med. 8(3), 016 (2025).

Bhattacharya, M. et al. Multi-modal fusion model for predicting adverse cardiovascular outcome post percutaneous coronary intervention. Physiol. Meas. 43(10), 105001 (2022).

Karpathy, A., Toderici, G., Shetty, S., Leung, T., Sukthankar, R. & Fei-Fei, L. Large-scale video classification with convolutional neural networks, in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 1725–1732 (2014).

Radford, A., Kim, J. W., Hallacy, C., Ramesh, A., Goh, G., Agarwal, S. et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.00020 (2021).

Meystre, S. M., Savova, G. K., Kipper-Schuler, K. C. & Hurdle, J. F. Extracting information from textual documents in the electronic health record: A review of recent research. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 15(4), 458–469 (2008).

Lee, J. et al. Biobert: A pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics 36(4), 1234–1240. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btz682 (2020).

Alsentzer, E., Murphy, J. R., Boag, W., Weng, W.-H., Jindi, D., Naumann, T. & McDermott, M. Publicly available clinical BERT embeddings improve radiology report classification, in Proceedings of the 2nd Clinical Natural Language Processing Workshop 133–140 (2019). https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/W19-1917 . https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31269046/

Fawcett, T. An introduction to roc analysis. Pattern Recogn. Lett. 27(8), 861–874 (2006).

Saito, T. & Rehmsmeier, M. The precision-recall plot is more informative than the roc plot when evaluating binary classifiers on imbalanced datasets. PLoS ONE 10(3), 0118432 (2015).

Naeini, M. P., Cooper, G. F. & Hauskrecht, M. Obtaining well calibrated probabilities .using bayesian binning, in Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 29 (2015)

Vickers, A. J. & Elkin, E. B. Decision curve analysis: A novel method for evaluating prediction models. Med. Decis. Making 26(6), 565–574 (2006).

Nguyen, D.A., Jose, S., Nguyen, K. & Medjaher, K. Explainable multimodal learning .for predictive maintenance of steam generators, in Proceedings of the 4th Asia Pacific Conference of the Prognostics and Health Management Society, Tokyo, Japan 01–08 (2023).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea(NRF) grant funded by the Korea government(MSIT) (RS-2024-00392315). This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI23C0896). This work was supported by Institute of Information & communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korea government(MSIT) (RS-2022-00143911, AI Excellence Global Innovative Leader Education Program).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.K. conceived the study, curated the data, developed the methodology, performed the formal analysis, and drafted the manuscript. J.S. contributed to data curation, validation, and critical revision of the manuscript. Y.K. provided clinical supervision, domain expertise, and project administration. T.J. and J.A. jointly supervised the study, contributed to the conceptualization, interpretation of results, and critical manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center (IRB No. 20230186). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, B., Suh, J., Kim, YH. et al. Multimodal machine learning for 5-year mortality prediction after percutaneous coronary intervention. Sci Rep 16, 2887 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32734-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-32734-z