Abstract

This study investigates whether Ginkgetin(GK) reverses cisplatin(DDP) resistance in cervical cancer cells by modulating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling axis to induce ferroptosis, and preliminarily elucidates its underlying mechanisms. DDP-resistant cervical cancer cell line HeLa/DDP was used for in vitro experiments. Cell proliferation was assessed by CCK-8 assay; migration and invasion capabilities were evaluated via wound healing and Transwell assays; colony formation assays measured proliferative capacity. Molecular docking analyzed the binding affinity of GK to Nrf2, HO-1, and GPX4 proteins. Intracellular ROS and Fe2+ levels were detected using fluorescent probes. Ferroptosis-related indicators including GSH, MDA, SOD, and CAT were measured by biochemical detection. Western blot analyzed expression of key proteins. Mechanistic validation employed the Nrf2 activator sulforaphane (SFN) and ferroptosis inhibitor ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1). An in vivo subcutaneous xenograft mouse model was established to observe the reversal effect of GK on DDP-resistant tumors, combined with histopathological and immunohistochemical analyses of tissue morphology and protein expression. GK significantly inhibited the proliferation of HeLa/DDP cells and enhanced their sensitivity to DDP. Combined treatment of GK and DDP notably suppressed proliferation, migration, invasion, and colony formation abilities of HeLa/DDP cells. Molecular docking revealed strong binding affinity between GK and Nrf2. Combination treatment markedly increased ROS and Fe2+ levels, reduced antioxidant capacity (GSH, SOD, CAT), induced lipid peroxidation with upregulated ACSL4 expression, and downregulated Nrf2, HO-1, and GPX4 expression. Transmission electron microscopy demonstrated characteristic mitochondrial morphological changes of ferroptosis. In vivo, co-treatment significantly reduced tumor volume of DDP-resistant xenografts, enhanced DDP’s antitumor efficacy, improved histopathological structures, and modulated related protein expression. GK induces ferroptosis by inhibiting the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway, thereby reversing DDP resistance in cervical cancer cells. These findings provide a potential novel therapeutic strategy for clinical management of cervical cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

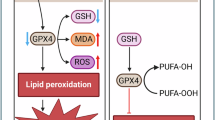

Cervical cancer remains one of the most prevalent malignancies among women worldwide with high incidence and mortality rates, posing a severe threat to female health1. In 2022, approximately 660,000 new cases and 350,000 deaths occurred globally, with over 80% arising in developing countries. China alone accounted for about 106,000 new cases and 59,000 deaths annually, making it the country with the second largest cervical cancer burden after India2. Although DDP-based chemotherapy remains the cornerstone for cervical cancer treatment, the incidence of DDP resistance substantially increases in recurrent or metastatic patients during prolonged treatment cycles, representing a critical barrier to clinical efficacy3. Therefore, elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying DDP resistance and identifying effective reversal strategies have become focal points in cervical cancer research. Ferroptosis is a recently characterized form of regulated cell death defined by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation4. It has been demonstrated to play a crucial role in tumorigenesis, progression, and chemoresistance5. Unlike classical apoptosis and necrosis, ferroptosis results from disturbances in intracellular iron metabolism and redox homeostasis, leading to accumulation of lipid peroxides and subsequent cell death6. Tumor cells can evade ferroptosis through activation of antioxidant defense systems, enhanced DNA repair, and ROS clearance, thereby acquiring chemotherapeutic resistance7. Induction of ferroptosis has thus emerged as a promising strategy to overcome chemoresistance. The Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway is pivotal in orchestrating cellular oxidative stress responses and maintaining iron homeostasis8. Nrf2 activates downstream antioxidant genes such as HO-1 and GPX4 to scavenge ROS and reduce lipid peroxidation, enhancing cell resilience against oxidative insults9. However, sustained Nrf2 activation is closely associated with chemoresistance in tumors10. Reports show that high Nrf2 expression decreases tumor cell sensitivity to ferroptosis, whereas inhibition of Nrf2 signaling induces ferroptosis and reverses drug resistance9. Hence, targeting the Nrf2/HO-1 axis to regulate ferroptosis is an emerging area of anticancer drug development. GK, a natural flavonoid derived from Ginkgo biloba leaves, exhibits potent anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antitumor effects11. Increasing evidence suggests GK enhances chemotherapeutic sensitivity through multiple mechanisms, notably reversing DDP resistance in various tumors including non-small cell lung cancer, colorectal cancer, and ovarian cancer12,13,14. Its mechanisms may involve modulation of iron metabolism, induction of ROS accumulation, and interference with the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway15. Nonetheless, systematic studies clarifying whether GK regulates ferroptosis via Nrf2/HO-1 signaling to reverse DDP resistance in cervical cancer are lacking. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the effects and molecular mechanisms of GK on Nrf2/HO-1-mediated ferroptosis in reversing DDP resistance in cervical cancer, using both cellular and animal models. The findings are expected to provide theoretical support and experimental groundwork for developing GK as a novel therapeutic agent against cervical cancer chemoresistance.

Materials and methods

-

1.

Cell Lines and Reagents The DDP-resistant cervical cancer cell line HeLa/DDP was obtained from Jiangxi Zhonghong Boyuan Company and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37℃ with 5% CO2. Prior to the experiments, the HeLa/DDP cell line was authenticated by STR profiling and routinely tested for mycoplasma contamination using the MycoAlert Mycoplasma Detection Kit (LT07-318, Lonza). GK was purchased from Selleck Chemicals. DDP, Nrf2 agonist sulforaphane (SFN), and ferroptosis inhibitor ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1) were procured from Maclin Biochemical Technology. Drugs were dissolved in DMSO and diluted to appropriate concentrations for experimental use.

-

2.

Cell Proliferation Assay (CCK-8) HeLa/DDP cells were seeded into 96-well plates and treated with various regimens. After 48 h incubation, 10 µL CCK-8 reagent was added per well and incubated for additional 2 h. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader. The half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) was calculated, and drug interaction was assessed by combination index (CI), where CI < 1 indicates synergy, CI = 1 additive effect, and CI > 1 antagonism.

-

3.

Wound Healing Assay Exponentially growing HeLa/DDP cells were seeded in 6-well plates and scratched with a sterile pipette tip when reaching 90% confluence. After washing with PBS to remove debris, culture medium supplemented with respective drugs but free of serum was added. Migration was monitored and photographed at 48 h, and wound closure rate calculated.

-

4.

Transwell Invasion Assay Cells (2 × 105 per well) were seeded in the upper chamber precoated with Matrigel. Drug-containing medium was added in the lower chamber. After 48 h incubation, non-invading cells were removed, and invaded cells fixed with methanol, stained with crystal violet, and counted under microscope.

-

5.

Colony Formation Assay Cells were plated at 500 cells per well in 6-well plates. Following 48 h drug treatment, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and stained with 0.5% crystal violet for 20 min. Colonies were counted to assess proliferation.

-

6.

Molecular Docking Molecular docking of GK with Nrf2, HO-1, and GPX4 proteins was performed using AutoDock Vina software. Binding sites, hydrogen bonds, and minimum binding energies were analyzed to predict target affinity.

-

7.

Ferroptosis-Related Marker Detection ROS levels were detected by DCFH-DA fluorescent probe staining; nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst and visualized under fluorescence microscopy. Intracellular Fe2+ was measured using FerroOrange probe with Hoechst counterstaining. Antioxidant indices (GSH, MDA, SOD, CAT) were determined following kit instructions.

-

8.

Western Blot Analysis Total protein was extracted and quantified by BCA assay. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto PVDF membranes. After blocking for 1 h, membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against Nrf2, HO-1, GPX4, and ACSL4, followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Bands were visualized by ECL and quantified using ImageJ software. In this study, we used the cutting gel because we incubated multiple proteins on a single membrane. Therefore, cut gels were adopted to obtain satisfactory lanes. However, all the samples were from the same experiment, and WB analysis was conducted simultaneously. The strips used in the article can all be found corresponding to those on the uncut membranes in the supplementary materials.

-

9.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) Cells were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, dehydrated, embedded, and sectioned for TEM observation. Mitochondrial morphological changes indicative of ferroptosis were evaluated.

-

10.

Construction of Nude Mouse Xenograft Model Healthy female BALB/c nude mice (SPF grade, 4–6 weeks old, body weight 16–20 g) were used. Each mouse received a subcutaneous injection of HeLa/DDP cells (5 × 106 cells per mouse). After successful modeling (tumor volume reached 100 mm2), mice were randomly divided into groups and administered intraperitoneal injections for 14 days as follows: GK (20 mg/kg, every 2 days), a dosage regimen established based on findings from previous studies28 and further validated through our preliminary experiments; DDP (5 mg/kg, every 3 days); SFN (5 mg/kg, every 2 days); and Fer-1 (5 mg/kg, daily). Tumor volume was measured every 2–3 days. Forty-eight hours after the last administration, mice were euthanized; tumor and kidney tissues were collected for HE staining, immunohistochemistry analysis, and Western blot detection. All animal experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of Qinghai Red Cross Hospital (KY-2024-38) and conducted in accordance with the 2010/63/EU Directive on animal protection. This study adhered to the ARRIVE guidelines. No accidental deaths occurred during the experiment. At the experimental endpoint (14 days after drug administration), all mice were deeply anesthetized via inhalation of 5% isoflurane in an induction chamber until the loss of pedal reflex. Subsequently, euthanasia was immediately performed by cervical dislocation while under deep anesthesia to ensure a painless death, followed by the rapid collection of tumors and major organs for further analysis.

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp) and GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software). Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). For comparisons between two independent groups, independent samples t-test was used. For comparisons among three or more groups, one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc correction was applied (Figs. 1A,E,H, 2B,D,F, 4B,D,E,F,G,H,L,J, 5B,D,E,F,G,H,L,J, 6B,D,E,F,G,H,L,J, 7B and 8B). The significance threshold for post hoc tests was adjusted by Bonferroni correction as P < 0.05/n (where n is the number of pairwise comparisons). Statistical significance for single comparisons was set at P < 0.05.

Results

GK suppresses HeLa/DDP cell proliferation and enhances DDP sensitivity

CCK-8 assay showed GK significantly inhibited proliferation of HeLa/DDP cells in a dose-dependent manner. When GK concentration ≥ 5 µM, cell proliferation was markedly suppressed (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1A,B). Calculated GK IC50: 8.925 µM; IC10: 4.021 µM; IC5: 2.181 µM; IC2.5: 1.01 µM. CCK-8 assay comparing DDP effects on HeLa/DDP versus HeLa cells indicated HeLa/DDP cells exhibited resistance: at 5 µM DDP, significant proliferation differences were noted (Fig. 1C,D). Calculated DDP IC50: HeLa cells 3.876 µM; HeLa/DDP cells 16.66 µM; resistance index: 4.298. IC10 concentration was used to exclude GK cytotoxicity in subsequent combination tests, setting GK concentration ≤ 4.021 µM. Combined GK and various DDP concentrations were tested; GK 4 µM plus DDP 16 µM showed lowest combination index (CI), indicating strongest synergy (Fig. 1E–G). GK 4 µM with different DDP doses enhanced inhibition of HeLa/DDP proliferation; IC50 calculated as 7.866 µM with reversal fold of 2.118.

GK enhances DDP inhibition of HeLa/DDP proliferation: (A,B) bar graphs and dose-response curves showing GK effects; (C,D) DDP effects on HeLa/DDP and HeLa cells; (E–G) heatmaps, line plots, and scatter plots of combination index; (H,I) bar and dose-effect showing GK plus DDP effects. n = 6 independent experiments.

GK enhances DDP suppression of HeLa/DDP cell migration, invasion, and colony formation

Wound healing assay demonstrated significantly reduced migration in GK plus DDP group versus control or monotherapy (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2A,B). Colony formation assay showed significant reduction in proliferation in combined treatment group (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2C,D). Transwell assay indicated decreased invasion ability with GK plus DDP compared to others (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2E,F).

Molecular docking of GK with target proteins

Molecular docking results reveal high binding affinities of GK with Nrf2, HO-1, and GPX4 (Table 1; Fig. 3), with strongest binding to Nrf2, suggesting Nrf2 may be the treatment target for reversing DDP resistance in cervical cancer.

GK cooperates with DDP to regulate Nrf2/HO-1 pathway and induce ferroptosis

Fluorescent probe assays showed significantly elevated ROS and Fe2+ levels in GK + DDP group versus control or monotherapy (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4A–D). Antioxidant markers GSH, SOD, and CAT significantly decreased, while MDA increased (Fig. 4E–H), indicating oxidative stress. Western blot showed decreased Nrf2, HO-1, GPX4 and increased ACSL4 expression in combination group (Fig. 4I,J). Transmission electron microscopy revealed ferroptosis features in mitochondria of GK + DDP group: reduced or absent cristae, vacuolization, increased membrane density, partial outer membrane rupture (Fig. 4K). The CCK-8 results showed that the cell activity in the combined group was significantly reduced (Fig. 4L).

SFN inhibits GK + DDP-Induced ferroptosis via Nrf2/HO-1 pathway

Compared to GK + DDP group, control, SFN, and GK + DDP + SFN groups exhibited significantly reduced ROS and Fe2+ levels (P < 0.001) (Fig. 5A–D). Elevated GSH, SOD, CAT, and decreased MDA levels were observed in these groups (Fig. 5E–H). WB showed increased Nrf2, HO-1, GPX4 and decreased ACSL4 expressions (Fig. 5I,J). TEM showed mitochondria with normal elongated or oval morphology, abundant cristae, and intact outer membrane in these groups. The CCK-8 results showed that the cell activity significantly increased after the use of SFN (Fig. 5L).

Fer-1 inhibits GK + DDP-induced ferroptosis in HeLa/DDP cells

Fer-1 treatment groups also showed significantly lower ROS and Fe2+ levels than GK + DDP group (P < 0.001) (Fig. 6A–D). GSH, SOD, CAT were significantly increased and MDA decreased (Fig. 6E–H). WB showed higher GPX4 and lower ACSL4 expressions (Fig. 6I,J). TEM revealed normal mitochondria morphology in these groups. The CCK-8 results showed that the cell activity significantly increased after the use of Fer-1 (Fig. 6L).

In vivo experiments confirm GK regulation of Nrf2/HO-1-mediated ferroptosis reverses DDP resistance

Cervical cancer DDP-resistant nude mouse subcutaneous xenograft model was established; drug intervention started on day 15. After 14 days, tumor volumes in GK + DDP group were significantly smaller than control, GK, or DDP groups (P < 0.05); SFN, Fer-1, GK + DDP + SFN, and GK + DDP + Fer-1 groups showed larger tumor volumes compared to GK + DDP group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 7A,B).

WB results showed significantly lower, Nrf2, HO-1, GPX4 and higher ACSL4 in GK + DDP group versus control or monotherapy ; increased expression of these proteins except ACSL4 was observed in control, SFN, GK + DDP + SFN groups compared to GK + DDP; similar results in Fer-1 groups (Fig. 8A,B).

The immunohistochemistry (IHC) indicate that compared with the control and single-drug groups, the combination of ginkgetin (GK) with DDP (DDP) significantly reduced the expression of Ki67, Nrf2, HO-1, and GPX4, while ACSL4 expression was significantly increased. Compared with the GK + DDP group, the control, SFN, GK + DDP + SFN, Fer-1, and GK + DDP + Fer-1 groups showed significantly increased expression of Ki67, Nrf2, HO-1, and GPX4, and significantly decreased ACSL4 expression (see Fig. 9). Hematoxylin & eosin (HE) staining of tumor tissues showed that compared with control and single-drug groups, the GK + DDP group exhibited multifocal large necrotic areas with nuclear pyknosis and karyolysis; normal tumor tissue morphology was restored after SFN and Fer-1 treatment (see Fig. 10). HE staining of kidney tissues showed intact structural integrity across all groups, with uniform cell sizes, tightly arranged renal tubules, intact basement membranes, and no evident necrosis or inflammatory infiltration (see Fig. 11).

Discussion

DDP resistance in cervical cancer is a major factor affecting chemotherapy efficacy16. Traditional mechanisms of resistance focus on drug efflux, DNA damage repair, and apoptosis inhibition; however, these pathways have complex regulatory networks, limiting targeted intervention efficacy17. Recently, ferroptosis—a type of iron-dependent cell death characterized by lipid peroxidation accumulation—has become a research focus in tumor drug resistance18. Due to unique cancer cell metabolism, high levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and specific mutations, some cancer types are more prone to ferroptosis19. Ferroptosis-related oxidative stress pathways and chemotherapy drugs induce high ROS production, which can trigger cellular stress and damage via oxidative stress mechanisms, disrupting redox homeostasis and leading to tumor cell death20. However, chronic high ROS levels in tumor cells can alter metabolic pathways, enhance antioxidant systems, and produce more antioxidant enzymes, increasing resistance to chemotherapy and resulting in drug resistance21. Therefore, ferroptosis is closely related to tumor drug resistance. Recent studies have demonstrated notable anticancer potential of GK in various tumor models22. For example, GK inhibits breast cancer growth by regulating the miRNA-122-5p/GALNT10 axis23. GK induces G2-phase arrest in HCT116 colon cancer cells through the modulation of b-Myb and miRNA34a expression24. In cervical cancer, GK inhibits HeLa cell proliferation via activation of the p38/NF-κB pathway, demonstrating good anticancer activity25. This study found that GK significantly inhibited proliferation, migration, and invasion of HeLa/DDP cells while enhancing the cytotoxicity of DDP, suggesting its role in reversing drug resistance. IC50 and combination index (CI) analyses via CCK-8 assays confirmed a synergistic antitumor effect between GK and DDP. Evidence confirms GK can induce ferroptosis in multiple tumor cells to exert anticancer effects26. GK can induce ferroptosis in HCT-116 cells, and GK enhances the antitumor effect of fluorouracil (5-FU) by inducing ferroptosis in the HCT-116 colon cancer xenograft model27. Additionally, GK synergizes with DDP to increase cytotoxicity in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells, elevating unstable iron pools and lipid peroxidation, enhancing mitochondrial membrane potential loss and apoptosis induced by DDP, confirming that GK promotes DDP-induced anticancer effects via ferroptosis induction28. This study observed that combined GK and DDP treatment markedly increased intracellular ROS and Fe2+ levels, decreased antioxidant markers GSH, SOD, and CAT, induced lipid peroxidation, upregulated lipid remodeling enzyme ACSL4 expression, and exhibited typical ferroptosis mitochondrial morphology by transmission electron microscopy (mitochondrial shrinkage, reduced cristae), consistent with ferroptosis phenotypes originally defined by Dixon et al. ACSL4 plays a key role in determining ferroptosis sensitivity by catalyzing incorporation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (e.g., AA, AdA) into membrane phospholipids, a prerequisite for lipid peroxidation29. The significant upregulation of ACSL4 here suggests GK + DDP induces ferroptosis by enhancing membrane lipid oxidation capacity. Many drug-resistant cancer cells show Nrf2 activation, leading to upregulation of protective genes that reduce ferroptosis and promote tumor progression by shielding cancer cells from chemotherapy-induced killing30. Thus, regulating Nrf2 expression influences sensitivity to ferroptosis. For instance, high Nrf2 in head and neck cancer cells reduces ferroptosis and causes chemoresistance; Nrf2 knockdown restores ferroptosis and reverses resistance31. In NSCLC, GK inhibits the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, increasing ferroptosis and DDP sensitivity28. This study demonstrated that GK + DDP treatment significantly inhibited Nrf2, HO-1, and GPX4 protein expression, suggesting it overcomes ferroptosis inhibition by downregulating Nrf2 activity. Molecular docking showed high affinity between GK and Nrf2, potentially interfering with its stability or nuclear translocation, thereby suppressing its transcriptional activity. Further, treatment with Nrf2 agonist SFN and ferroptosis inhibitor Fer-1 partially reversed GK + DDP-induced ROS elevation, decreased antioxidant capacity, and ACSL4 upregulation, confirming the specific role of the Nrf2/HO-1 axis in GK + DDP-induced ferroptosis. Animal experiments showed GK + DDP markedly inhibited HeLa/DDP xenograft growth and consistent protein changes and ACSL4 upregulation in tissues, indicating in vivo reversal of resistance by ferroptosis induction without evident toxicity, suggesting good biocompatibility. Nevertheless, this study has limitations. Although protein expression and molecular docking suggest Nrf2 as a target, direct actions were not confirmed by Nrf2 gene silencing, CRISPR knockout, or nuclear translocation blockade; future studies should establish stable knockdown cell lines for mechanism verification. Also, GK effects on other ferroptosis-related pathways such as xCT system, FTH1, and ALOX15 were unexplored, limiting comprehensive network understanding. Moreover, although animal experiments preliminarily indicated low toxicity, long-term safety and pharmacokinetics require further systematic study. In conclusion, this study systematically verified that GK induces ferroptosis and reverses cervical cancer DDP resistance by inhibiting the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway.

Conclusion

GK enhances DDP sensitivity by inhibiting the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway, promoting intracellular ROS and Fe2+ accumulation, weakening antioxidant capacity, and inducing ferroptosis in DDP-resistant cervical cancer cells. This mechanism was validated both in vitro and in vivo, indicating potential of GK as an adjuvant chemotherapy agent for treating drug-resistant cervical cancer. Future research should further elucidate molecular mechanisms and evaluate clinical application value.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Yuan, Y. et al. HPV post-infection microenvironment and cervical cancer. Cancer Lett. 497, 243–254 (2021).

Perkins, R. B. et al. Cervical cancer screening: A review. JAMA. 330(6), 547–558 (2023).

Abu-Rustum, N. R. et al. NCCN Guidelines® insights: cervical Cancer, version 1.2024. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 21 (12), 1224–1233 (2023).

Jiang, X., Stockwell, B. R. & Conrad, M. Ferroptosis: mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22 (4), 266–282. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-020-00324-8 (2021).

Aldea, M. et al. Overcoming resistance to tumor-targeted and immune-targeted therapies. Cancer Discov. 11 (4), 874–899 (2021).

Lei, G., Zhuang, L. & Gan, B. The roles of ferroptosis in cancer: tumor suppression, tumor microenvironment, and therapeutic interventions. Cancer Cell. 42 (4), 513–534 (2024).

Romani, A. M. P. Cisplatin in cancer treatment. Biochem. Pharmacol. 206, 115323 (2022).

Tonelli, C., Chio, I. I. C. & Tuveson, D. A. Transcriptional regulation by Nrf2. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 29 (17), 1727–1745 (2018).

He, F., Ru, X. & Wen, T. NRF2, a transcription factor for stress response and beyond. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21 (13), 4777 (2020).

Lin, L. et al. Nrf2 signaling pathway: current status and potential therapeutic targetable role in human cancers. Front. Oncol. 13, 1184079 (2023).

Adnan, M. et al. Ginkgetin: A natural biflavone with versatile pharmacological activities. Food Chem. Toxicol. 145, 111642 (2020).

Ren, Y. et al. Ginkgetin induces apoptosis in 786-O cell line via suppression of JAK2-STAT3 pathway. Iran. J. Basic. Med. Sci. 19 (11), 1245–1250 (2016).

Wu, L. et al. Ginkgetin suppresses ovarian cancer growth through Inhibition of JAK2/STAT3 and MAPKs signaling pathways. Phytomedicine. 116, 154846 (2023).

Wang, H. J. et al. TFEB promotes Ginkgetin-induced ferroptosis via TRIM25 mediated GPX4 lysosomal degradation in EGFR wide-type lung adenocarcinoma. Theranostics. 15 (7), 2991–3012 (2025).

Hu, S. et al. Research progress of Nrf2 and ferroptosis in tumor drug resistance. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi. 26 (10), 765–773 (2023).

Kyrgiou, M. & Moscicki, A. B. Vaginal microbiome and cervical cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 86 (Pt 3), 189–198 (2022).

Singh, N. et al. MDC1 depletion promotes cisplatin induced cell death in cervical cancer cells. BMC Res. Notes. 13 (1), 146 (2020).

Zhang, C. et al. Ferroptosis in cancer therapy: a novel approach to reversing drug resistance. Mol. Cancer. 21 (1), 47 (2022).

Chen, X. et al. Broadening horizons: the role of ferroptosis in cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 18 (5), 280–296 (2021).

Cui, Q. et al. Modulating ROS to overcome multidrug resistance in cancer. Drug Resist. Updat. 41, 1–25 (2018).

Chun, K. S., Kim, D. H. & Surh, Y. J. Role of reductive versus oxidative stress in tumor progression and anticancer drug resistance. Cells 10 (4), 758 (2021).

Cao, J. et al. Ginkgetin inhibits growth of breast carcinoma via regulating MAPKs pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 96, 450–458 (2017).

Alu, A. et al. Ginkgo Biloba derivative Ginkgetin inhibits breast cancer growth by regulating the miRNA-122-5p/GALNT10 axis. Chin. Med. J. (Engl). 137 (19), 2387–2389 (2024).

Lee, Y. J. et al. Ginkgetin induces G2-phase arrest in HCT116 colon cancer cells through the modulation of b-Myb and miRNA34a expression. Int. J. Oncol. 51 (4), 1331–1342 (2017).

Cheng, J., Li, Y. & Kong, J. Ginkgetin inhibits proliferation of HeLa cells via activation of p38/NF-κB pathway. Cell. Mol. Biol. (Noisy-le-grand). 65 (4), 79–82 (2019).

Xiong, B. et al. Ginkgetin from Ginkgo biloba: mechanistic insights into anticancer efficacy. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 15 (1), 50 (2025).

Zhang, S. et al. Ginkgo biflavones cause p53 wild-type dependent cell death in a transcription-independent manner of p53. J. Nat. Prod. 86 (2), 346–356 (2023).

Lou, J. S. et al. Ginkgetin derived from Ginkgo Biloba leaves enhances the therapeutic effect of cisplatin via ferroptosis-mediated disruption of the Nrf2/HO-1 axis in EGFR wild-type non-small-cell lung cancer. Phytomedicine. 80, 153370 (2021).

Mortensen, M. S., Ruiz, J. & Watts, J. L. Polyunsaturated fatty acids drive lipid peroxidation during ferroptosis. Cells 12 (5), 804 (2023).

Jaramillo, M. C. & Zhang, D. D. The emerging role of the Nrf2-Keap1 signaling pathway in cancer. Genes Dev. 27 (20), 2179–2191 (2013).

Roh, J. L. et al. Nrf2 Inhibition reverses the resistance of cisplatin-resistant head and neck cancer cells to artesunate-induced ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 11, 254–262 (2017).

Acknowledgements

Thanks for funding from the Basic Research Program of Qinghai Provincial Science and Technology Department and Qinghai Province obstetrics and gynecology disease clinical medical research center.

Funding

This research was supported by Basic Research Program of Department of Science and Technology of Qinghai Province(2025-ZJ-726) and Qinghai Province obstetrics and gynecology disease clinical medical research center(2024-SF-L03).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.W.: Data curation, investigation, methodology, project administration, validation, visualization, writing-review and editing. Y.L.: Conceptualization, visualization, writing-original draft, data curation, investigation, methodology, formal analysis. Y.B. and L.W.: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, writing-review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

The studies involving animals were approved by Ethics Committee of Qinghai Red Cross Hospital(KY-2024-38). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, F., Liu, Y., Wang, L. et al. Ginkgetin reverses cisplatin resistance in cervical cancer by regulating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway to induce ferroptosis. Sci Rep 16, 1542 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33111-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33111-6