Abstract

Breast cancer remains a leading cause of mortality among women globally. Early diagnosis and precise classification are essential for treatment and improving survival rates. This research introduces a novel algorithm: the Parallel Enzyme Action Optimizer (PEAO). PEAO introduces three key innovations: a parallel strategy to enhance global exploration, a multi-strategy communication mechanism (optimal replacement, optimal mean replacement, and circular optimal replacement) to improve information exchange, and the Lévy flight strategy to avoid local optima. The proposed algorithm was applied to optimize the hyperparameters of a BiLSTM network for breast cancer diagnosis. Experimental results on the Breast Cancer Wisconsin Diagnostic (BCWD) and Wisconsin Breast Cancer (WBC) datasets demonstrate that the PEAO-BiLSTM model significantly improves classification accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score compared with recent meta-heuristic algorithms and other hyperparameter optimization methods. These results confirm that the proposed approach provides a robust and reliable diagnostic framework, contributing to the development of intelligent, data-driven systems for clinical decision support in breast cancer diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the deadliest malignant cancers in women worldwide1. According to statistics from the World Health Organization, its incidence rate has been rising year by year and shows a trend toward younger age groups2. Early detection and precise classification are crucial for improving cure rates, extending patient survival, and reducing treatment costs3. As AI technology continues to develop, ML-driven diagnostic tools have made significant progress in medical image analysis and tissue pathology identification. Among these, breast cancer classification has become a typical application of ML in the medical field4,5.

When classifying breast cancer cases, constructing a classification model with good performance is crucial, and hyperparameter configuration plays an essential role in determining how well the model performs6. Common ML models, such as Support Vector Machines (SVM), Decision Trees (DT), and Neural Networks (NN), exhibit performance that strongly relies on proper hyperparameter tuning7,8. In deep learning (DL), various hyperparameter combinations, like learning rate and batch size, can lead to significant differences in model prediction accuracy. Therefore, how to effectively optimize hyperparameters has become a bottleneck constraining the further development of intelligent diagnostic systems.

Currently, the main hyperparameter optimization methods, although simple to implement, are extremely inefficient in complex spaces9,10. Additionally, these methods cannot utilize search history information and are prone to getting trapped at suboptimal solutions. The meta-heuristic algorithms, with their group-based collaborative search mechanisms and global optimization capabilities, have been widely adopted for hyperparameter optimization tasks11,12,13. For example, Genetic Algorithm (GA), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), and Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) have demonstrated good results in image recognition and classification14,15,16. However, these algorithms still suffer from insufficient global search capabilities, a tendency to get trapped at suboptimal solutions, slow convergence speeds when handling complex search spaces, and poor stability. Therefore, designing an optimization method with stronger robustness, search capabilities, and stability has become an important research topic. This study aims to answer the following research question: How can an efficient meta-heuristic optimization algorithm be designed to achieve both strong global exploration and stable convergence for neural network hyperparameter optimization in breast cancer diagnosis?

In response to these issues, this research proposes a novel meta-heuristic algorithm: the Parallel Enzyme Action Optimizer (PEAO). This algorithm builds upon the traditional Enzyme Action Optimizer17 in several aspects, primarily in the following three areas: (1) a parallel strategy, which divides the population into multiple subpopulations, enabling them to search in parallel in independent spaces to enhance global exploration capabilities; (2) a multi-strategy communication mechanism: three communication strategies—optimal replacement, optimal mean replacement, and circular optimal replacement—are proposed and applied alternately to improve information sharing efficiency between individuals and population collaboration capabilities; (3) a Lévy flight strategy, which utilizes Lévy distributions to generate non-uniform long-range jumps, effectively escaping local optima traps. By applying PEAO to model hyperparameter optimization in breast cancer classification tasks and conducting experimental validation on multiple benchmark function sets and real-world datasets, the results demonstrate that PEAO not only outperforms various comparison algorithms in accuracy and classification performance but also exhibits significant advantages in stability and adaptability.

The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

-

(1)

We propose a novel bio-inspired optimization method, PEAO, which incorporates parallel strategies, multi-strategy communication mechanisms, and Lévy flight strategies to enhance population diversity and search balance;

-

(2)

We evaluated PEAO on the CEC2017 benchmark functions, demonstrating its superiority over several recent state-of-the-art algorithms;

-

(3)

We applied PEAO to optimize BiLSTM hyperparameters for breast cancer classification on the BCWD and WBC datasets, achieving higher accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 scores than other hyperparameter optimization methods;

-

(4)

Sensitivity analysis, ablation studies, and statistical analysis confirmed the robustness and stability of the proposed method.

The remaining chapters of this paper are organized as follows: Section “Related works” reviews relevant research on breast cancer classification and hyperparameter optimization. Section “Parallel enzyme action optimizer (PEAO)” presents a detailed discussion of the construction principles of the PEAO algorithm, including parallel strategy, multi-strategy communication mechanism, Lévy flight strategy, algorithm pseudocode, sensitivity analysis, and ablation analysis. Section “Performance analysis of PEAO” conducts systematic performance evaluation experiments, including comparative algorithm experiments, box plot analysis, convergence curve analysis, and exploration-exploitation analysis. Section “Application of PEAO in breast cancer classification” applies PEAO to actual breast cancer classification tasks, conducts experiments on the hyperparameter optimization process of the model, and verifies its classification performance on real medical datasets. Section “Conclusions and future work” summarizes the main work and research contributions, discusses the advantages and disadvantages of PEAO, and proposes future research.

Related works

Applications of ML and DL in breast cancer diagnosis

Breast cancer, a common and life-threatening type of tumor in women, holds significant strategic importance for improving patient survival rates, optimizing treatment plans, and reducing medical costs through early and precise diagnosis18,19. Recently, the application of AI, mainly including ML and DL, has achieved significant breakthroughs in critical stages of breast cancer diagnosis, such as medical image analysis and histopathological identification, greatly advancing the development of automated and intelligent diagnostic systems20,21,22,23,24,25. Among various breast cancer classification tasks, constructing high-performance predictive models remains the core objective.

Aswathy and Jagannath26 developed a SVM classification approach using integrated features for automatically identifying breast cancer from stained histopathological images. This method combines three types of biologically relevant and clinically effective image features. It uses k-means clustering to extract the nuclear region and then constructs a feature vector containing 15 features. To validate the classification performance, the authors conducted extensive experiments on two publicly available datasets, UCSB and BreakHis, and compared the results with those of mainstream classifiers. According to the results, SVM outperformed other models in multiple metrics, including accuracy, specificity, F1-score, and precision, with an accuracy rate of approximately 90% on both datasets.

Naseem et al.27 proposed an automated diagnosis and prognosis detection system for breast cancer using ML. The study integrated SVM, Logistic Regression, Naive Bayes, and DT to construct an ensemble model, feeding the prediction results from each classifier into an ANN for final decision-making, forming a “stacked” architecture. Experiments showed that the ensemble model (SVM + LR + NB + DT + ANN) achieved an accuracy of 98.83% on the diagnostic dataset, outperforming single algorithms such as SVM (98.10%) and ANN (98.24%). On the prognosis dataset, accuracy was improved to 88.33% by combining class weight balancing with upsampling.

Muduli et al.28 designed an automated breast cancer diagnosis method using a deep convolutional neural network (DCNN) for classifying images. The method consists of only five learnable layers, effectively mitigating overfitting by reducing the number of parameters and incorporating max pooling techniques, while enhancing model generalization through a comprehensive data augmentation strategy. Experiments on three public mammography datasets and two ultrasound datasets showed that the model achieved classification accuracy of 96.55%, 90.68%, 91.28%, and 100%, 89.73%, respectively, outperforming current mainstream pre-trained models and traditional CAD methods, while significantly reducing computational complexity and training time. The study validated the efficiency and robustness of CNN in multimodal breast cancer diagnosis.

Liu et al.29 proposed a DL-based automatic classification method for pathological images called AlexNet-BC. This method introduces data augmentation and transfer learning strategies based on the traditional AlexNet network and improves the classification accuracy of the model for breast pathological images at different magnification levels by fine-tuning the ImageNet pre-trained model. Experimental results demonstrate that this method achieves superior accuracy and generalization capabilities on three breast cancer pathological image datasets—BreaKHis, IDC, and UCSB—outperforming traditional models such as VGG-16, GoogleNet, and ResNet. This study provides a feasible high-performance solution for breast CAD systems.

Chattopadhyay et al.30 proposed a DL approach named MTRRE-Net to identify breast cancer using histopathological images. The approach reduces the gradient vanishing issue in networks by introducing a contrasting method that combines dual residual blocks with recurrent networks, while enhancing the ability to learn complex patterns through a multi-scale feature extraction strategy. The study was evaluated using the BreaKHis standard dataset, achieving high classification accuracy across different magnification levels through the integration of multi-scale feature learning, dual residual operations, and recurrent connections, significantly outperforming models such as GoogLeNet, DenseNet, and ResNet. Additionally, through 5-fold cross-validation, confusion matrices, and ROC curve analysis, the model’s generalization capability on small-scale datasets was validated.

Alshayeji et al.31 designed a breast cancer diagnosis system using a shallow artificial neural network for benign-malignant classification using the WBCD and the WDBC. The model consists of a single hidden layer, utilizing ReLU and Sigmoid activation functions, combined with the Adam optimizer, without the need for feature selection or optimization algorithms. Under five-fold cross-validation, the WBCD system achieved 99.85% accuracy, 100% sensitivity, and 99.72% specificity; the WDBC system reached 99.47% accuracy, 99.59% sensitivity, and 99.53% specificity, with AUC values of 99.86% and 99.56%, respectively. The model outperforms existing ANN methods combined with feature optimization on both WBCD and WDBC, validating the strong classification capability and efficiency of shallow ANNs in the original feature space.

However, whether it is a classic ML model or a more complex DL model, its classification performance is highly sensitive and heavily dependent on the configuration of model hyperparameters32,33. For example, different combinations of hyperparameters like the number of units in the hidden layer (NumHiddenUnits), maximum training epochs (MaxEpochs), and mini-batch size (MiniBatchSize) in the BiLSTM model can significantly impact the model’s convergence speed and final classification accuracy34,35. Therefore, how to efficiently and robustly optimize these critical hyperparameters has become a key bottleneck in improving the performance of breast cancer intelligent diagnosis systems and is currently a major focus of research.

Hyperparameter optimization in ML and DL

Yadav and Kumar36 proposed a DL method that combines hyperparameter optimization with a novel network architecture—the Fractional CNN (Frac-CNN) based on PSO—to enhance the performance of automatic detection of breast cancer. The method enhances the model’s ability to perceive nonlinear and complex patterns in mammography images by introducing a fractional-order activation function (Frac-ReLU), while utilizing the PSO algorithm for global optimization of key hyperparameters in the Frac-CNN, significantly improving the model’s accuracy and generalization ability. Experiments demonstrate that this method achieves an accuracy of 99.35% on the dataset, all outperforming traditional CNNs and other existing methods. This research highlights the immense potential of combining evolutionary algorithm optimization with novel CNN architectures in early breast cancer screening, offering new insights for developing robust, high-precision auxiliary diagnostic systems.

Thirumalaisamy et al.37 proposed a new framework, EACO-ResNet101, which integrates DL with meta-heuristic optimization to enhance the classification performance. This method is based on transfer learning principles, using a pre-trained ResNet101 network as the backbone structure. It employs an EACO to automatically optimize multiple key hyperparameters, thereby effectively improving the model’s performance. Experiments demonstrate that the proposed framework achieves outstanding performance on the CBIS-DDSM and MIAS breast cancer datasets, with accuracy of 98.63% and 99.15%, significantly outperforming the traditional ResNet101 model and other optimization methods.

Gonçalves et al.38 proposed a method combining GA and PSO for the optimization of hyperparameters and structure of CNNs to increase the accuracy of breast cancer detection in infrared images. The study optimized the fully connected layer structure and key hyperparameters of three commonly used pre-trained CNNs, including VGG16, ResNet50, and DenseNet201, to overcome the inefficiency and unstable performance issues associated with manual parameter tuning. Experiments were conducted using the DMR-IR infrared breast image database, and the proposed method was tested under two different data splitting strategies. The results indicated that the F1-score of the GA-optimized VGG16 model significantly improved from 0.66 to 0.92, and that of ResNet50 improved from 0.83 to 0.90, while PSO also achieved notable performance improvements. This study demonstrates the significant potential of meta-heuristic algorithms for CNN hyperparameter search, providing strong support for the development of efficient and automated breast cancer diagnostic systems.

Shankar et al.39 designed a method that uses the CSSA and deep transfer learning (CSSADTL-BCC). Addressing the issues of hyperparameter sensitivity and overfitting risks faced by existing DL models in breast cancer classification, the authors innovatively introduced the CSSA for hyperparameter optimization. This method achieves global search by simulating the foraging and anti-predation behaviors of a sparrow population, and integrates chaotic mapping to enhance local exploration capabilities, significantly improving the hyperparameter tuning efficiency of the stacked gated recurrent unit (SGRU) classifier. Experimental results indicate that the CSSA-optimized SGRU model reaches a classification accuracy of 98.61%, significantly outperforming mainstream DL models.

Hamza et al.40 proposed an IBES optimization and synergic DL-based breast cancer histopathology image classification model (IBESSDL-BCHI). To address the issue of hyperparameter sensitivity in NN models used for breast cancer classification, the authors innovatively designed an IBES by integrating an opposing learning mechanism (OBL) to improve the global exploration capability of traditional vulture search and adopted a three-stage position update strategy to optimize the hyperparameters of the synergic DL (SDL). The SDL model integrates multiple DCNN components with a collaborative network to enhance feature expression capabilities, while the IBES algorithm achieves efficient parameter tuning. Experimental validation on the BreakHis dataset demonstrates that the IBES-optimized SDL-LSTM framework achieves a maximum classification accuracy of 99.63% across five test sets, significantly outperforming mainstream DL models.

To clearly illustrate the strengths and weaknesses of existing approaches, Table 1 summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of previous studies.

In conclusion, previous studies have highlighted the tremendous potential of meta-heuristic algorithms in optimizing hyperparameters for breast cancer classification models and improving diagnostic performance. By automatically exploring complex hyperparameter spaces, these methods significantly outperform traditional grid and random search methods in effectiveness, achieving outstanding classification accuracy on multiple public datasets. However, current mainstream meta-heuristic algorithms still face challenges when applied to hyperparameter optimization for breast cancer classification, including limited global exploration capabilities, susceptibility to local optima, suboptimal convergence speeds, and room for improvement in stability. These limitations constrain the further improvement of intelligent diagnostic system performance and the reliability of practical deployment. Therefore, developing a new optimization algorithm with stronger robustness, superior global search capabilities, and higher stability is of important theoretical and practical relevance to advancing breast cancer precision classification technology. The parallel enzyme action optimizer (PEAO) is specifically designed to address these key challenges.

Parallel enzyme action optimizer (PEAO)

This section presents a comprehensive introduction to the PEAO. PEAO is an improved version of the Enzyme Action Optimizer (EAO). In PEAO, the substrate represents the solution in the algorithm, and it continuously reacts under the influence of the enzyme until the final solution is obtained. PEAO enhances the algorithm’s performance through a parallel strategy, a multi-strategy communication mechanism, and a Lévy flight strategy. In the parallel strategy, the overall population is partitioned into multiple independent groups, with each group conducting parallel search optimization, thereby enabling parallel processing of the search process. The multi-strategy communication mechanism includes three strategies: optimal replacement, optimal mean replacement, and circular optimal replacement. The Lévy flight strategy is a random walk mechanism based on the Lévy distribution, designed to enhance the search’s jumping ability and diversity.

Parallel communication strategy

In the meta-heuristic algorithm, there are two common parallel strategies: absolute parallelism and virtual parallelism. Absolute parallelism utilizes multiple processors to simultaneously process different individuals in the algorithm, achieving parallel processing through hardware. Virtual parallelism is logical parallelism that does not rely on hardware. Virtual parallelism divides the algorithm’s candidate solutions into multiple groups, with each group independently executing the algorithm’s search strategy and communicating between groups.

In PEAO, all solutions are divided into multiple groups, each of which is independent of the others and runs the same search strategy independently during the algorithm’s solution process. Different groups communicate with each other when the communication threshold is met, thereby strengthening cooperation between groups. The PEAO algorithm adopts a multi-strategy communication mechanism, using three different communication strategies: optimal replacement, optimal mean replacement, and circular optimal replacement.

Strategy 1: Optimal Replacement. In this strategy, each group marks the substrate with the worst within the group. The worst substrates are replaced by the global optimal solution, ensuring that each group moves toward the optimal solution. During the replacement process, the optimal substrates from all groups migrate into each group, guiding the position update of each group by replacing the worst substrates within them.

Strategy 2: Optimal Mean Replacement. In this strategy, each group marks the substrate with the best and the substrate with the worst within the group. The worst substrates are updated using the mean of the best substrates across all groups, ensuring that each group moves toward the optimal solution. In the replacement process, the average of the optimal substrates across all groups is transferred to each group, guiding the position update of each group by replacing the worst substrate within it.

Strategy 3: Circular Optimal Replacement. In this strategy, each group marks the substrate with the best and the substrate with the worst within the group. The worst substrate in each group is updated using the best substrate from the previous group, ensuring that each group moves toward the optimal solution. For example, the worst substrate in the second group is substituted with the best substrate from the first group, the worst substrate in the third group is substituted with the best substrate from the second group, and so on, until the worst substrate in the first group is substituted with the best substrate from the last group. During the replacement process, the optimal substrate from the previous group migrates to the next group, guiding the position update of the group by replacing the worst substrate in the next group.

Relying solely on Strategy 1, Strategy 2, or Strategy 3 operating independently cannot guarantee the full performance of PEAO. Therefore, to fully leverage the advantages of each of these three communication strategies, PEAO introduces an alternating usage mechanism, enabling the three communication strategies to be executed alternately according to rules during the algorithm’s operation, thereby enhancing overall optimization performance. Additionally, PEAO incorporates a periodic communication mechanism, enabling each group to exchange information within fixed iteration cycles to prevent getting stuck in local optima. In PEAO, the communication threshold for each group is set to 10, meaning that communication occurs once every 10 iterations.

Algorithm 1 provides the pseudocode for the communication strategy of PEAO. In Algorithm 1, the system first determines whether the communication threshold has been reached. If the condition is met, communication proceeds. A random integer between 1 and 3 (inclusive of 1 and 3) is generated and assigned to the variable Cs. Then, a decision is made: if the value of Cs is 1, Communication Strategy 1 is selected and executed; if the value of Cs is 2, Communication Strategy 2 is selected and executed; if the value of Cs is 3, Communication Strategy 3 is selected and executed. Regardless of the selected strategy, it is executed for each group, totaling k executions, where k represents the number of groups after grouping.

Mathematical model of PEAO

Before starting search optimization in PEAO, grouping is performed first. Assuming that the total number of substrates is N, they are divided into k groups, so that the number of substrates in each group is the rounded integer of N/k. The initialization formula for each group of substrates is shown in Eq. (1).

In Eq. (1), \({X}_{i}^{\left(0\right)}\) represents the initial location of the i-th substrate, where i ranges from 1 to N. LB and UB are the lower and upper bounds of the search region, and \({r}_{i}\) is a random value in [0,1]. In addition, each substrate is multidimensional, with the dimension set to \(dim\).

After initializing the substrates, all substrates are evaluated to obtain the fitness values for each substrate. The substrate with the minimum fitness value is defined as the best substrate, denoted as \({X}_{best}^{\left(0\right)}\), and \(f\left({X}_{best}^{\left(0\right)}\right)\) represents its fitness value.

At iteration t, two candidate positions are generated for each substrate \({X}_{i}^{(t-1)}\), and the formula for the first candidate position is shown in Eq. (2).

In Eq. (2), \({r}_{i}\) is a random value in [0,1] and \({AF}_{t}\) is an adaptive factor, which is calculated as shown in Eq. (3). In Eq. (3), T denotes the upper limit of iterations.

There are two methods for calculating the second candidate position: one uses a vector random factor, and the other uses a scalar random factor. The formula for calculating the second candidate position using a vector random factor is shown in Eq. (4).

In Eq. (4), \({sc}_{A}\) is a vector random factor with a dimension \(dim\) in the range [EC,1], EC is the enzyme concentration, set to 0.1. \(d\) is the distance between two different substrates p and q randomly selected from all substrates, calculated as shown in Eq. (5).

In Eq. (4), \(Levy\left(dim\right)\) is the Lévy stride with dimension \(dim\), which is calculated as shown in Eq. (6).

In Eq. (6), the parameters \(\mu\:\) and \(v\) are normal distribution random numbers with dimension \(dim\), \(\mu\:\sim N(0,\:{{\sigma\:}_{\mu\:}}^{2})\), \(v\sim N\left(\text{0,1}\right)\), \(\sigma _{\mu } = \left( {\frac{{\Gamma \left( {1 + \beta } \right) \cdot \sin \left( {\frac{{\pi \beta }}{2}} \right)}}{{\Gamma \left( {\frac{{1 + \beta }}{2}} \right) \cdot \beta \cdot 2^{{\frac{{\beta - 1}}{2}}} }}} \right)^{{\frac{1}{\beta }}}\), \(\beta\:=1.5\).

The calculation formula for the second candidate position using the scalar random factor is shown in Eq. (7).

In Eq. (7), \({sc}_{B}\) is a scalar random factor with dimension 1 in the range [EC,1], and \(Levy\left(1\right)\) is a Lévy stride with dimension 1. Subsequently, \({X}_{i,2,A}^{\left(t\right)}\) and \({X}_{i,2,B}^{\left(t\right)}\) are evaluated, where the smaller fitness value is denoted by \({X}_{i,2}^{\left(t\right)}\).

Then these \({X}_{i,1}^{\left(t\right)}\) and \({X}_{i,2}^{\left(t\right)}\) are evaluated, and the one with small fitness value among the two candidate positions is denoted by \({X}_{i,upd}^{\left(t\right)}\), which is computed as shown in Eq. (8).

Then \({X}_{i,upd}^{\left(t\right)}\) and \({X}_{i}^{\left(t-1\right)}\) will be evaluated, and the one with small fitness value will replace the location of the i-th substrate at the t-th iteration \({X}_{i}^{\left(t\right)}\), which is calculated as shown in Eq. (9).

Update the global best substrate after completing the above steps. The specific step is: if \(f\left({X}_{i}^{\left(t\right)}\right)<f\left({X}_{best}^{\left(t-1\right)}\right)\), then \({X}_{best}^{\left(t\right)}={X}_{i}^{\left(t\right)}\).

Finally, the communication strategy of the algorithm is executed. First, it determines whether the communication threshold has been reached. If so, communication between each group is performed, and one of three different communication strategies is selected and executed through the variable Cs.

To further clarify the biological inspiration of PEAO, the algorithm’s design closely follows the catalytic behavior of enzymes in biochemical reactions. In biological systems, enzymes act as catalysts that convert substrates into products through specific reaction pathways while maintaining high efficiency and selectivity. Analogously, in PEAO, each substrate represents a candidate solution in the optimization process, and the enzyme’s catalytic action corresponds to the iterative updating of solutions toward optimal states. The enzyme concentration controls the intensity of catalytic reactions, which in the algorithm regulates the adaptive search step and balances exploration and exploitation. The generation of candidate solutions through adaptive and Lévy-based updates mimics the random yet directed transformation of substrates under enzymatic influence. Furthermore, the parallel subpopulations simulate multiple enzyme systems operating in parallel metabolic pathways, while the multi-strategy communication mechanism imitates the exchange of intermediate products between enzymes to enhance cooperation and global efficiency. Through this mapping, the enzyme action metaphor is directly and coherently tied to the algorithmic operators, providing a solid biological foundation for the proposed bio-inspired optimizer.

Pseudocode of PEAO

Algorithm 2 presents the pseudocode of PEAO. It begins by initializing parameters, including N, T, the dimension \(dim\), the variable boundaries LB/UB, and the number of groups k, and generates initial substrates (solutions) for each group, evaluating the fitness values of all substrates. Then, the iteration process begins. In each iteration, the dynamically adjusted adaptive factor \({\text{A}\text{F}}_{\text{t}}\) is first calculated to control the perturbation intensity of the subsequent update process. Next, the substrates within each group are updated: The first candidate solution \({X}_{i,1}^{\left(t\right)}\) is generated using Eq. (2), while the second candidate solutions \({X}_{i,2,A}^{\left(t\right)}\) and \({X}_{i,2,B}^{\left(t\right)}\) are generated using Eqs. (4) and (7), respectively, and the better solution \({X}_{i,2}^{\left(t\right)}\) is retained. Then, the advantages of \({X}_{i,1}^{\left(t\right)}\) and \({X}_{i,2}^{\left(t\right)}\) are combined using Eq. (8) to generate a new solution \({X}_{i,upd}^{\left(t\right)}\). Finally, compare \({X}_{i,upd}^{\left(t\right)}\) with the previous generation solution \({X}_{i}^{\left(t-1\right)}\) using Eq. (9), and keep the one with better fitness as the current solution \({X}_{i}^{\left(t\right)}\). Subsequently, enter the communication phase, where a communication strategy is randomly selected every 10 generations and executed across all groups to enhance global search capabilities and avoid local optima.

Figure 1 presents the overall flowchart of the proposed PEAO algorithm. This diagram highlights its core steps: parameter initialization, substrates initialization (grouped), evaluate initial substrates, update substrates within each group, evaluate updated substrates, communication between groups, determine the maximum iteration, and obtain the optimal substrate.

Sensitivity analysis

In PEAO, the number of groups k is an important parameter that directly affects the scale of group division and communication efficiency. To verify the impact of k settings on algorithm performance, this section designs experiments to conduct a sensitivity analysis on different k values. Specifically, under the premise that other parameters remain unchanged, different group numbers k are set, and the algorithm is run on multiple test functions.

We will select the CEC202241 as the test function for this experiment. CEC2022 contains 1 unimodal function, 4 basic functions, 3 hybrid functions, and 4 composition functions. Figure 2 shows the 3D visualization of CEC2022, with each subfigure corresponding to the 3D image of the test functions F1 to F12 in CEC2022.

To examine how different k values affect the algorithm, tests were conducted with k values of 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10. The corresponding algorithm names are PEAO-k2, PEAO-k4, PEAO-k6, PEAO-k8, and PEAO-k10. Other algorithm parameters were set as follows: N was set to 50, T was set to 1000, and LB and UB were set to −100 and 100.

Additionally, each algorithm was executed 30 times separately, and the fitness value of the best solution from each run was recorded. To thoroughly assess how the algorithms perform, the evaluation was based on the following metrics: Best, Mean and STD. Among these, Best represents the optimal fitness value obtained from the 30 runs, Mean represents the average fitness value, and STD measures the stability of the algorithm, that is, the degree of fluctuation in the fitness values.

After running the code, the experimental results of PEAO-k2, PEAO-k4, PEAO-k6, PEAO-k8, and PEAO-k10 in 10 dimensions at CEC2022 are presented in Table 2.

Table 2 presents the outcomes of the PEAO algorithm tested on 12 functions in the CEC2022 when the number of groups k is set to 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10, including Best, Mean, and STD. Overall, PEAO maintains high stability and convergence accuracy in most test functions.

On the unimodal function F1, the Best and Mean values for all algorithms are 3.0000E + 02, and the STD is close to zero (STD is 0 for k = 2), indicating that PEAO is insensitive to the number of groups in unimodal problems and converges stably to the global optimum. For the basic functions F2 to F5, there are small differences between algorithms in terms of Best and Mean, but there are slight differences in STD, especially between F2 and F4. As the k increases (k = 8 or 10), STD also increases significantly. This suggests that when there are too many groups, the reduced size of subgroups may weaken local search capabilities, leading to increased performance fluctuations. For the hybrid functions F6 to F8, PEAO exhibits more pronounced sensitivity. As the k increases, the Mean shows an overall upward trend. For example, in F6, the Mean gradually increases from 1.8019E + 03 to 1.8188E + 03, and the STD also increases significantly, indicating that PEAO requires higher group collaborative search capabilities when dealing with structurally complex and highly nested functions, and an appropriate number of groups is more beneficial for the stability of the algorithm. In the composition functions F9 to F12, PEAO demonstrates overall excellent performance, particularly on F9, where the STD of all algorithms is 0 or extremely small, indicating that the algorithm possesses strong global search capabilities when handling such functions. However, there were some performance fluctuations in F11 and F12. For example, in F11, the STD was close to 0 when k = 4, but it significantly increased when k = 2, k = 6, k = 8, and k = 10, indicating that the number of groups still has a certain impact on such complex composite functions.

In summary, PEAO demonstrates high robustness and stability on unimodal and partially basic functions; for hybrid and composition functions, setting the number of groups k appropriately is particularly critical. Smaller k values (k = 2 or k = 4) allow for a more efficient balance between search efficiency and diversity, rendering them appropriate for most optimization problems. Excessively large values of k may reduce local search capabilities, thereby affecting overall convergence performance. Therefore, it is recommended to prioritize moderate group sizes in practical applications.

Ablation analysis

To evaluate the individual and combined contributions of PEAO’s three core components (parallel strategy, multi-strategy communication mechanism, and Lévy flight strategy), we conducted an ablation experiment. It is important to note that the multi-strategy communication mechanism was designed based on the premise of the parallel strategy; therefore, there are no standalone PEAO-M or PEAO-ML variants. We constructed the following five algorithm variants for comparison with the complete PEAO: PEAO-P (enabling only the parallel strategy), PEAO-L (enabling only the Lévy flight strategy), PEAO-PM (combining the parallel strategy and multi-strategy communication mechanism), PEAO-PL (combining the parallel strategy and Lévy flight strategy), and PEAO (the complete algorithm incorporating all three components).

Experiments were conducted on 12 functions (10-dimensional) from the CEC2022 test set. Each variant was run independently 30 times, recording its best fitness value (Best), mean (Mean), and standard deviation (STD). Results are summarized in Table 3.

Results indicate that the complete PEAO algorithm achieved optimal or highly competitive performance on nearly all test functions, particularly excelling in stability (STD). For instance, on functions F1, F5, and F9, PEAO exhibited zero standard deviation, demonstrating perfect consistency in locating global optima. In contrast, variants lacking one or more components (PEAO-P or PEAO-L) exhibit higher volatility and occasionally deliver inferior average performance on certain complex multi-modal and mixed functions (F4, F7, F8).

The combination of all three components in PEAO ensures a robust balance between exploration (facilitated by parallel strategies and Lévy flights) and exploitation (enhanced by multi-strategy communication mechanisms). This synergy enables PEAO to effectively avoid local optima while maintaining rapid and stable convergence, thereby validating the necessity and complementary roles of each proposed component.

Performance analysis of PEAO

This section will describe in detail the experimental performance analysis of PEAO, including experimental setup, benchmark function description, experimental results and analysis, box plot analysis, convergence curve analysis, and exploration and exploitation analysis.

Experimental setup of performance

To comprehensively evaluate the PEAO, this section selects nine mainstream meta-heuristic algorithms for comparative analysis, including Enzyme Action Optimizer (EAO)17, Horned Lizard Optimization Algorithm (HLOA)42, Parrot Optimizer (PO)43, Fick’s Law Algorithm (FLA)44, African Vultures Optimization Algorithm (AVOA)45, Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO)46, Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA)47, Sine Cosine Algorithm (SCA)48, and Moth-Flame Optimization (MFO)49. The parameter settings of the nine selected comparison algorithms are provided in Table 4. Additionally, the other parameters for all algorithms are set as follows: the total number of individuals (solutions) is set to 50, the maximum number of iterations is set to 1000, and the UB and LB are set to −100 and 100.

To ensure a fair comparison, each algorithm was run independently 30 times, and the fitness value of the best solution found in each run was recorded. To thoroughly evaluate how well the algorithms perform, the following metrics were applied: Best, Mean, and STD. The Best metric represents the optimal fitness value obtained across the 30 runs, the Mean metric represents the average fitness value, and the STD metric measures algorithm stability, that is, the degree of fluctuation in fitness values.

Benchmark function description

Thirty functions from the CEC201750 were selected for this experiment. The CEC2017 dataset contains 3 unimodal functions, 7 simple multimodal functions, 10 hybrid functions, and 10 composition functions. Figure 3 shows the 3D visualization of F1 to F15 in CEC2017, and Fig. 4 shows the 3D visualization of F16 to F30 in CEC2017. Each subfigure corresponds to the 3D image of the test functions F1 to F30 in CEC2017.

Table 5 shows information on the 30 benchmark functions, including their constraint intervals and theoretical optimal values for each function.

Experimental results and analysis of performance

After running the code, the results of PEAO, EAO, HLOA, PO, FLA, AVOA, HHO, WOA, SCA, and MFO in 10 dimensions at CEC2017 are presented in Table 6.

Table 6 presents a comparison of the performance of PEAO and other algorithms on the CEC2017. Through quantitative evaluation using Best, Mean, and STD metrics, PEAO demonstrates notable strengths in convergence, stability, and adaptability to complex problems.

Overall, PEAO demonstrated superior performance in most of the 30 functions. Specifically, PEAO achieved the best Best values on 24 functions (F1–F4, F6–F9, F11–F24, F27–F28), the best Mean values on 21 functions (F1–F5, F6–F9, F11, F13, F17–F20, F22–F23, F25–F29). This indicates that PEAO not only possesses strong optimal solution search capabilities but also demonstrates outstanding performance in terms of global search stability and result consistency. Additionally, PEAO achieved the theoretical optimal value for the Best metric on 18 functions (F1–F4, F6, F9, F11–F20, F22).

First, in the three unimodal functions F1 to F3, both PEAO and EAO achieve the theoretical optimal value, with Best and Mean values of 100, 200 and 300, and STD approaching 0. This indicates that, in terms of convergence speed and local search capability, PEAO and EAO are consistent, both capable of quickly and accurately locating the global optimal solution. In contrast, algorithms such as HLOA, PO, and FLA generally exhibit numerical overflow or high deviation phenomena.

In these simple multimodal functions from F4 to F10, PEAO demonstrates stronger search capabilities. Taking F6 as an example, PEAO has a Mean of 6.0000E + 02 and a STD of only 8.4444E−14. In contrast, FLA has an STD of 5.4890E−02, and HLOA reaches as high as 1.9600E + 01, indicating that PEAO can effectively escape local extrema in multi-peak environments. Additionally, for F7, a typical periodic multi-peak function, PEAO’s STD is 3.5114E + 00, far lower than HLOA’s 9.5751E + 01 and PO’s 1.7352E + 01, further validating PEAO’s robust advantage in balancing exploration and exploitation.

In hybrid functions F11–F20, the advantages of PEAO are particularly evident. Such functions typically feature complex nested function structures and multiple local extrema, placing higher demands on the search strategy and global guidance capabilities of optimization algorithms. Taking F13 as an example, PEAO has a Mean of 1.3038E + 03 and a STD of only 2.7245E + 00, while HLOA has a Mean of 1.6785E + 08 and a STD as high as 1.8231E + 08, indicating that its search path is extremely unstable and prone to being misled or trapped in unfavorable search regions. Algorithms such as MFO and SCA also exhibit extremely high volatility on this type of function. For instance, SCA has a Mean of 4.4002E + 04 and a STD of 3.0561E + 04 on F13, indicating that its search process is severely unstable. The reason PEAO maintains good performance is due to the combination of its parallel communication mechanism and Lévy flight strategy, which gives it stronger adaptability in terms of diversity and overall coordination in swarm search.

The composition functions F21–F30 are typically random rotations and superpositions of multiple basic functions, requiring extremely high robustness and global adaptability of the algorithm. In typical functions such as F23, F26, F27, and F28, PEAO also demonstrates superior stability and accuracy compared to other algorithms. For example, in F26, PEAO’s Best and Mean values are both 2.9000E + 03, with STD approaching zero; whereas WOA’s Mean value in this function is 3.4201E + 03, with STD as high as 5.1318E + 02, indicating extremely unstable performance. Similarly, in the high-dimensional composite function F29, PEAO’s STD is 6.6564E + 00, far lower than SCA (2.2163E + 01) and MFO (6.2099E + 01), further validating its exceptional interference resistance in complex search spaces.

It is worth noting that compared to EAO, PEAO achieves significant performance improvements in most test functions, particularly in hybrid and composition functions. This result fully validates the effectiveness of the parallel strategy, multi-strategy communication mechanism (optimal replacement, optimal mean replacement, and circular optimal replacement), and Lévy flight strategy introduced by PEAO in boosting the algorithm’s capacity for wide-range exploration and enhancing solution diversity. Additionally, the periodic communication mechanism effectively prevents getting stuck in suboptimal regions, further improving solution quality and convergence stability.

Furthermore, to verify the statistical significance of PEAO’s performance advantages over other comparison algorithms, we conducted a Wilcoxon signed-rank test on the average results of PEAO versus EAO, HLOA, PO, FLA, AVOA, HHO, WOA, SCA, and MFO across the CEC2017 test function set comprising 30 functions in 10 dimensions. Table 7 presents the p-values from the test results.

The results indicate that the p-values between PEAO and all comparison algorithms are significantly below the 0.05 significance level, with the smallest p-value reaching 1.51E−06 (in comparison with the PO algorithm). This indicates that the PEAO algorithm is statistically significantly superior to all comparison algorithms, including EAO, HLOA, PO, FLA, AVOA, HHO, WOA, SCA, and MFO. This conclusion strongly confirms the significant improvement in optimization performance achieved by the PEAO algorithm. Its advantages are not only reflected in the average results but also demonstrate high reliability and stability in statistical significance.

Overall, PEAO demonstrates exceptional search capability and adaptability in unimodal, simple multimodal, hybrid, and composition functions, with its advantages becoming increasingly evident as problem complexity increases. Compared to other classical optimization algorithms, PEAO possesses stronger optimal value approximation capability, lower solution volatility, and higher convergence consistency, making it a novel intelligent optimization method that combines stability and high performance.

Box plot analysis

According to the results presented in Table 6, box plots of STD for 10 algorithms on 30 functions were plotted. Figure 5 shows the box plots of STD obtained by PEAO and nine comparative meta-heuristic algorithms on 30 test functions in CEC2017. The horizontal axis represents the 10 algorithms, and the vertical axis represents STD (logarithmic scale).

Figure 5 shows that, overall, the box plots of the PEAO and EAO have lower box positions and shorter box lengths, indicating that their data are concentrated within a smaller range, with the lower quartile and upper quartile being relatively close. The median line is also relatively low, indicating that the standard deviation values of most data points are small. This suggests that the PEAO and EAO algorithms exhibit low variability and good stability in multiple experiments or applications. Additionally, the median of PEAO is lower than that of all other algorithms.

The box plot of the HLOA algorithm has distinct features, with a high box height, indicating a high degree of dispersion. Additionally, there are outliers significantly distant from the box, suggesting that the algorithm encounters extreme values when calculating the standard deviation, leading to inconsistent or less reliable outcomes. The box plots of the PO, FLA, AVOA, HHO, WOA, SCA, and MFO algorithms exhibit similar characteristics. The box position and length are relatively moderate, indicating that the data dispersion is at an intermediate level, neither as highly dispersed as the HLOA algorithm nor as highly concentrated as the PEAO and EAO algorithms. From the median line position and box range, the algorithm results exhibit fluctuations, but the overall fluctuation amplitude is within an acceptable range, and there are no obvious outliers or only a few outliers.

In summary, the results in Fig. 5 clearly demonstrate that PEAO maintains its optimization capabilities while exhibiting excellent solution stability and overall robustness. Compared to EAO and other classical meta-heuristic algorithms, PEAO has smaller STD values and lower variability across multiple functions, demonstrating stronger consistency and adaptability.

To make the results more understandable to readers from the medical community, it is worth noting that a narrower box and a lower median value in the box plot indicate greater stability and consistency across multiple independent runs. In the context of medical diagnosis, such stability implies that the algorithm can produce more reliable and reproducible results under different random initializations or data partitions, which is essential for ensuring the robustness of clinical decision-making systems.

Convergence curve analysis

To better evaluate the convergence ability of PEAO, this section illustrates the convergence curves of PEAO alongside nine other algorithms on four representative functions (F1, F8, F12, and F28), as shown in Fig. 6. These functions can comprehensively reflect the optimization performance of the algorithm under different problem complexities.

In the function F1 shown in Fig. 6a, PEAO converges rapidly to the theoretical optimal value (100) in the early stages of iteration and remains stable in subsequent iterations. In contrast, while EAO also converges quickly, its initial descent rate is slightly lower than that of PEAO. In the function F8 shown in Fig. 6b, PEAO’s convergence speed is significantly superior to most comparison algorithms, ultimately achieving the lowest objective function value. This indicates that PEAO is highly capable of avoiding local optima when dealing with multi-peak functions. In the function F12 shown in Fig. 6c, both PEAO and EAO converge rapidly to the global optimum, demonstrating excellent local search capabilities. Among them, PEAO reaches the optimal value at a slightly faster rate, significantly outperforming other algorithms. Figure 6d illustrates the convergence behavior on function F28, where PEAO demonstrates exceptional adaptability, rapidly reducing the objective value within a limited number of iterations and ultimately stabilizing without noticeable oscillation trends.

In summary, the convergence trends of the four representative functions indicate that PEAO not only has excellent initial convergence speed but also maintains stable improvement in the later optimization stage, demonstrating good global search and local development capabilities.

For readers from the medical field, the convergence curves can be interpreted as an indicator of how efficiently and reliably the algorithm reaches optimal model configurations. A faster and smoother convergence means that the model parameters can be optimized more quickly and consistently, which contributes to improving the timeliness and reliability of computer-aided diagnosis in clinical practice.

Exploration and exploitation analysis

In the meta-heuristic algorithm, how well exploration and exploitation are balanced plays a significant role in affecting the algorithm’s overall performance. This section uses visualization to show how PEAO dynamically adjusts the weights of exploration and exploitation during the optimization process to verify its balancing capabilities.

To quantify the ratio of exploration to exploitation in algorithmic optimization, a diversity metric will be employed. First, the diversity of all solutions in a particular dimension is calculated using Eq. (10). In Eq. (10), \({Diversity}_{j}\) denotes the diversity of all solutions in dimension j, \(median\left({x}_{ij}\right)\) represents the median value of the i-th solution in dimension j, and N denotes the number of solutions.

Then, calculate the diversity index for this iteration using Eq. (11). In Eq. (11), Diversity represents the diversity of all solutions in all dimensions for this iteration, and D represents the dimension of the problem.

After calculating diversity in each iteration, the percentages of exploration and exploitation in each iteration are calculated based on diversity, as shown in Eqs. (12) and (13). In Eqs. (12) and (13), \(Exploration\) represents the exploration percentage of the algorithm, \(Exploitation\) represents the exploitation percentage of the algorithm, and \({Diversity}_{max}\) represents the maximum value of the current diversity.

Based on the above calculation method, F1, F8, F12 and F28 from CEC2017 were selected as representatives to plot the percentage change in exploration and exploitation of PEAO in the iteration process, as shown in Fig. 7.

Percentage change in exploration and exploitation on some functions of CEC2017, where (a) is percentage change in exploration and exploitation on F1, (b) is percentage change in exploration and exploitation on F8, (c) is percentage change in exploration and exploitation on F12, and (d) is percentage change in exploration and exploitation on F28.

In function F1 shown in Fig. 7a, the exploration ratio decreases rapidly, and the exploitation ratio increases rapidly in the early stage of PEAO, indicating that the algorithm quickly locates the global optimal region. After approximately 200 iterations, the exploitation ratio stabilizes at nearly 100%, while the exploration ratio approaches 0%. In function F8 shown in Fig. 7b, during the initial stage, the exploration ratio is greater than the exploitation ratio, as the algorithm broadly searches the solution space to identify potential optimal regions. After approximately 400 iterations, the exploration ratio is approximately 0%, while the exploitation ratio is approximately 100%. In function F12 shown in Fig. 7c, the exploration ratio is high in the initial stage and then gradually decreases, while the exploitation ratio is low and then gradually increases. After approximately 400 iterations, the exploration ratio is approximately 0%, and the exploitation ratio is approximately 100%. In function F28 shown in Fig. 7d, the exploration ratio decreases rapidly in the initial stage, while the exploitation ratio increases rapidly. After approximately 200 iterations, the exploration ratio is approximately 0%, and the exploitation ratio is approximately 100%.

In summary, PEAO quickly shifts to exploitation in single-peak problems and avoids getting stuck in local optima in multi-peak and complex problems by maintaining its exploration capabilities. The Lévy flight strategy enhances the jumpiness of exploration, while the parallel strategy and multi-strategy communication mechanism improve development efficiency through sub-group collaboration. The combination of these three strategies achieves an efficient balance across global and local search, and between exploration and exploitation.

Runtime analysis

To evaluate the runtime performance of the proposed algorithm, a runtime analysis was conducted on 10-dimensional problems of the CEC2022 benchmark set. The experimental conditions were set as follows: population size (N = 50) and maximum number of iterations (T = 1000). Table 8 presents the runtime results (in seconds) of PEAO, EAO, and other comparative algorithms on 12 test functions (F1–F12). The other comparative algorithms include the Horned Lizard Optimization Algorithm (HLOA), Henry Gas Solubility Optimization (HGSO)51, and Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO)52.

The experimental results indicate that the PEAO algorithm exhibits increased runtime compared to the original EAO algorithm. This increase in runtime is a direct consequence of PEAO incorporating three primary mechanisms: the Parallel Strategy, the Multi-Strategy Communication Mechanism, and the Lévy Flight Strategy. The stacking of these strategies results in PEAO incurring a higher per-evaluation cost than the original EAO.

Compared to other benchmark algorithms, PEAO exhibits moderate computational complexity. EAO demonstrates the shortest runtime, while GMO requires the longest due to its more intricate population management mechanism. HGSO’s runtime closely matches that of PEAO, both reflecting the computational overhead associated with their complex evolutionary mechanisms.

In summary, although the PEAO algorithm incurs increased runtime compared to the original EAO, the computational cost is fully justified by its significant performance improvements, making it a highly practical solution.

Application of PEAO in breast cancer classification

This section offers a comprehensive explanation of the application of PEAO to breast cancer classification, including the experimental setup, dataset description, experimental results, and analysis.

Experimental setup of classification

To validate PEAO’s optimization capabilities in real-world problems, we applied PEAO to the critical medical diagnosis task of breast cancer classification. Traditional ML models are highly dependent on hyperparameter settings, which have a decisive impact on model performance. PEAO is an optimization algorithm applied to fine-tune the hyperparameters of ML models.

BiLSTM is an improved type of RNN that is suitable for processing data with sequential features or time-series data and is particularly suitable for context-dependent tasks. BiLSTM is an extension of the standard LSTM. The standard LSTM can only process time-series data sequentially from front to back (forward), meaning it can only use “past” information to predict current or future outcomes. In contrast, BiLSTM introduces a “backward” LSTM that simultaneously processes sequence data from back to front, enabling it to utilize both “past” and “future” information.

To verify the performance of PEAO more comprehensively, nine mainstream meta-heuristic algorithms were selected for comparative analysis, including EAO, HLOA, PO, FLA, AVOA, HHO, WOA, SCA, and MFO. The parameter configurations of the nine selected comparative algorithms are the same as presented in Table 4.

In this experiment, the algorithm was used to optimize the three hyperparameters of the BiLSTM. These three hyperparameters are: NumHiddenUnits (number of hidden neurons), MaxEpochs (maximum number of training epochs), and MiniBatchSize (batch size per iteration). NumHiddenUnits determines the dimension of the hidden state vector in each LSTM layer, directly affecting the model’s expressive capability. A larger number of neurons may improve the model’s capacity to learn patterns but can also cause overfitting or increase training time. MaxEpochs indicates the number of complete iterations the model performs across the entire training set. A higher number of epochs aids model convergence but may also cause overfitting or waste computational resources. MiniBatchSize determines how many samples are processed in each update of the model’s weights. An appropriate batch size helps improve the stability and convergence speed of model training. Therefore, the dimension settings for all algorithms are set to 3.

Additionally, the other parameter configurations for PEAO and the nine other algorithms are as follows: the total population (solution) size is set to 20, the T is set to 50, the UB is set to [256, 200, 256], and the LB is set to [32, 50, 32]. Furthermore, the fitness function for all algorithms was set to the complement of the accuracy of BiLSTM on the test set.

In addition to the nine meta-heuristic algorithms under comparison, Bayesian Optimization (BO) and Random Search (RS)—commonly used hyperparameter optimization methods—were also employed for comparison. The parameter settings for BO and RS are as follows.

For BO, the optimization objective function was defined as the complement of accuracy, consistent with the meta-heuristic algorithms. The search ranges for the three hyperparameters—NumHiddenUnits, MaxEpochs, and MiniBatchSize—were also set to the same intervals as those used in the meta-heuristic algorithms, namely [32, 256], [50, 200], and [32, 256], respectively. In addition, the maximum number of objective function evaluations for BO was set to 50, identical to the maximum number of iterations in the meta-heuristic algorithms, and the remaining settings followed MATLAB’s default settings.

For RS, the optimization objective function was also defined as the complement of accuracy. The search spaces for the three hyperparameters—NumHiddenUnits, MaxEpochs, and MiniBatchSize—were also set as discrete sets: {32, 64, 128, 256}, {50, 100, 150, 200}, and {32, 64, 128, 256}, respectively. Furthermore, the number of iterations for RS was also set to 50, consistent with the maximum number of iterations in the meta-heuristic algorithms, and all other configurations were kept as MATLAB’s default settings.

To comprehensively evaluate each algorithm’s ability to optimize hyperparameters, we will use four evaluation metrics: accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. Their formulas are as follows:

Dataset description

BCWD dataset description

The Breast Cancer Wisconsin Diagnostic (BCWD) dataset53 was selected as the dataset for this experiment. This dataset is a breast cancer dataset provided by the University of Wisconsin and is widely recognized as a benchmark dataset in breast cancer classification research.

The features in BCWD are calculated based on the digital images of fine needle aspiration (FNA) samples from breast lumps, describing the characteristics of the cell nuclei present in the images. There are 569 rows of data and 32 columns of features. Among the 32 features are id and diagnosis (including malignant and benign), as well as the mean, standard error, and worst value of 10 real-valued features. The first 5 rows of BCWD data are shown in Table 9.

To better visualize the numerical distribution of each feature in the BCWD, a feature distribution plot was created, as shown in Fig. 8. Each subplot in Fig. 8 corresponds to a feature (excluding id and diagnosis), where the x-axis shows the feature values and the y-axis indicates the probability density. We used normalized histograms combined with kernel density estimation to illustrate the distribution trends of feature values, enabling a clearer revelation of whether each feature exhibits skewed distribution, multimodality, outliers, and other data characteristics. As observed in the figure, most features exhibit right-skewed distributions (with longer right tails), indicating that the majority of samples are concentrated in the low-value range.

WBC dataset description

The Wisconsin Breast Cancer (WBC) dataset54 was selected as the dataset for this experiment. This dataset is a breast cancer dataset provided by the University of Wisconsin and is widely recognized as a benchmark dataset in breast cancer classification research.

This dataset contains 699 rows of data and 11 feature columns. These 11 features include id and class (distinguishing malignant and benign), along with 9 cellular attributes. Table 10 displays the first 5 rows of the WBC dataset.

To better visualize the numerical distribution of each feature in the WBC, we created a feature distribution plot, as shown in Fig. 9. Each subplot in Fig. 9 corresponds to a feature (excluding id and class), where the x-axis represents the feature value and the y-axis represents the probability density. The figure reveals that the vast majority of features exhibit a right-skewed distribution, meaning a large number of samples cluster around smaller values, while a smaller number of samples take larger values.

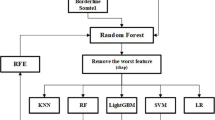

Data preprocessing

To ensure the quality and consistency of data input into the BiLSTM model, we implemented a comprehensive data preprocessing workflow. The stages of this workflow, as shown in Fig. 10, clearly illustrate the sequential processing steps applied to both the BCWD and WBC datasets before model training.

First is data cleaning. The datasets were inspected for missing and inconsistent values. No missing values were found in the BCWD dataset. Missing values were identified in the WBC dataset and imputed using the median of the data.

Next is normalization. All numerical features were transformed using the Z-score standardization method into a distribution with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. This normalization method enhances the stability and convergence speed of model training.

Finally, feature reshaping was performed. Input data was reshaped to conform to the BiLSTM model’s input format. The 30 features in the BCWD dataset were converted into a 30 × 1 sequence format to meet the BiLSTM architecture’s input requirements. Similarly, the 9 features in the WBC dataset were converted into a 9 × 1 sequence format to meet the BiLSTM architecture’s input requirements.

Experimental results and analysis of classification

Experimental results and analysis on the BCWD dataset

After optimization using the PEAO, EAO, HLOA, PO, FLA, AVOA, HHO, WOA, SCA, and MFO algorithms, as well as the hyperparameter optimization methods BO and RS, the optimized results of the BiLSTM hyperparameters—NumHiddenUnits, MaxEpochs, and MiniBatchSize—are presented in Table 11.

As shown in Table 11, different algorithms yield varying results in hyperparameter optimization. The PEAO algorithm selects a relatively large value of 240 for NumHiddenUnits, indicating its preference for constructing NN structures with stronger expressive capabilities. Additionally, the algorithm sets MaxEpochs to 200, one of the highest values among all algorithms, indicating a tendency to thoroughly train the model during the search process to enhance fitting accuracy. Regarding MiniBatchSize, PEAO selects a moderately large value of 155, effectively balancing training efficiency and convergence stability. This parameter configuration reflects PEAO’s ability to strike a good balance between global search and local fine-tuning.

In contrast, EAO’s optimal solution for NumHiddenUnits is 73, the smallest among all algorithms, indicating its preference for a simple model structure; however, its MiniBatchSize reaches 221, which is significantly large, potentially improving training efficiency but affecting the model’s update frequency and generalization ability. SCA’s hyperparameter combination is somewhat unique, with MaxEpochs set to 60 and MiniBatchSize to 63, both of which are the lowest values, indicating a preference for small-scale models that train quickly. However, this may lead to underfitting or insufficient training of the model. In contrast, HHO uses larger values for both NumHiddenUnits and MaxEpochs, reflecting its higher demand for model complexity and training time. This may help improve the model’s nonlinear modeling capabilities but also carries the risk of overfitting.

To validate how well the optimized hyperparameters of the aforementioned twelve algorithms on BiLSTM, we reapplied the optimized hyperparameter values to the BiLSTM model and compared the four evaluation metrics of the model on the test set. The model names corresponding to the BiLSTM models using different algorithms are PEAO-BiLSTM, EAO-BiLSTM, HLOA-BiLSTM, PO-BiLSTM, FLA-BiLSTM, AVOA-BiLSTM, HHO-BiLSTM, WOA-BiLSTM, SCA-BiLSTM, MFO-BiLSTM, BO-BiLSTM, and RS-BiLSTM. All models were trained with a training-to-test ratio of 7:3. The results of these models and the results of the BiLSTM model without hyperparameter optimization are presented in Table 12.

As shown in Table 12, PEAO-BiLSTM performed the best across all evaluation metrics, achieving an accuracy of 99.12%, a precision rate of 100.00%, a recall rate of 97.62%, and an F1-score of 98.80%. This indicates that the hyperparameter combinations optimized by PEAO achieve excellent classification performance in the BiLSTM model, enabling more accurate identification of benign and malignant breast cancer samples with extremely low misclassification rates. In contrast, while EAO-BiLSTM, as the predecessor of PEAO, also demonstrates relatively superior performance across various metrics (e.g., an F1-score of 96.77%), it still lags behind PEAO in certain aspects. Traditional algorithms such as WOA-BiLSTM and the unoptimized BiLSTM model exhibit relatively lower performance, with the BiLSTM model achieving an F1-score of 94.40%, significantly lower than that of PEAO-BiLSTM. This comparison validates the role of hyperparameter optimization in enhancing the performance of DL models, while also demonstrating that PEAO possesses stronger capabilities and stability in searching for optimal hyperparameters.

Figure 11 provides a visual comparison of each model from Table 12, showing their performance in accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score using a bar chart. Each sub-chart corresponds to an evaluation metric, and each bar represents a model. As shown in the figure, the PEAO-BiLSTM model achieves the highest values across all four metrics, particularly with a precision rate of 100%, significantly outperforming other models and demonstrating its exceptional ability to identify positive samples. In contrast, the bar charts for HHO-BiLSTM, WOA-BiLSTM, and the original BiLSTM models are generally lower, indicating deficiencies in their optimization capabilities or model generalization. Overall, Fig. 11 vividly illustrates the clear benefits of PEAO in hyperparameter tuning tasks, further supporting its effectiveness and usefulness in boosting the performance of DL models.

Experimental results and analysis on the WBC dataset

After optimization using the PEAO, EAO, HLOA, PO, FLA, AVOA, HHO, WOA, SCA, and MFO algorithms, as well as the hyperparameter optimization methods BO and RS, the optimized results of the BiLSTM hyperparameters—NumHiddenUnits, MaxEpochs, and MiniBatchSize—are presented in Table 13.

As shown in Table 13, the hyperparameters identified for BiLSTM across different optimization algorithms on the WBC dataset exhibit significant variation, reflecting distinct search strategies and convergence behaviors among the algorithms. The proposed PEAO yields the configuration: NumHiddenUnits = 130, MaxEpochs = 123, MiniBatchSize = 215. This configuration indicates that PEAO tends to select moderately large model capacities while controlling the number of training epochs within a reasonable range. It also employs a larger batch size to enhance training stability and convergence speed per epoch.

Regarding NumHiddenUnits, some algorithms favor extremely large network structures. While this may improve expressive power, it also increases the risk of overfitting and computational overhead. Regarding MaxEpochs, PEAO’s 123 occupies a middle ground—lower than algorithms requiring more iterations to converge, yet higher than the minimum values. This indicates PEAO achieves convergence without overfitting. Regarding MiniBatchSize, PEAO’s selected value of 215 represents a large batch size (close to MFO’s 218). This typically yields smoother gradient estimates and faster training per iteration, provided hardware supports this batch size.

To validate how well the optimized hyperparameters of the aforementioned twelve algorithms on BiLSTM, we reapplied the optimized hyperparameter values to the BiLSTM model and compared the four evaluation metrics of the model on the test set. The model names corresponding to the BiLSTM models using different algorithms are PEAO-BiLSTM, EAO-BiLSTM, HLOA-BiLSTM, PO-BiLSTM, FLA-BiLSTM, AVOA-BiLSTM, HHO-BiLSTM, WOA-BiLSTM, SCA-BiLSTM, MFO-BiLSTM, BO-BiLSTM, and RS-BiLSTM. All models were trained with a training-to-test ratio of 7:3. The results of these models and the results of the BiLSTM model without hyperparameter optimization are presented in Table 14.

Table 14 demonstrates that all BiLSTM models incorporating meta-heuristic algorithms for hyperparameter optimization outperform unoptimized BiLSTM models in classification performance on the WBC dataset, indicating that hyperparameter optimization significantly enhances model performance. Among these, the proposed PEAO-BiLSTM achieved the best results across all four evaluation metrics: 98.56% (Accuracy), 97.26% (Precision), 98.61% (Recall), and 97.93% (F1-score). These values substantially exceed those of other optimization algorithms and the unoptimized model, validating the effectiveness and stability of PEAO in hyperparameter optimization.

In contrast, models optimized by other algorithms also improved performance to some extent, but remained below the overall PEAO-BiLSTM. For instance, EAO-BiLSTM achieved an accuracy of 97.61%, 0.95% lower than PEAO-BiLSTM; while HLOA-BiLSTM achieved a recall rate of 94.44%, 4.17% lower than PEAO-BiLSTM. These results indicate that the PEAO algorithm more efficiently balances global exploration and local exploitation within the search space, thereby identifying superior hyperparameter combinations.

Furthermore, the overall trend shows that the unoptimized BiLSTM model performed at the lowest level across all four metrics, exhibiting a significant gap compared to the optimal model. This further underscores the significance of meta-heuristic algorithms in hyperparameter tuning for deep learning models, demonstrating their ability to effectively enhance classification performance and generalization capabilities.

In summary, PEAO’s superior performance on the WBC dataset not only validates its efficiency in continuous optimization problems but also highlights its potential application in hyperparameter optimization for deep neural networks. It provides a more robust and accurate solution for breast cancer classification tasks.

Conclusions and future work

In the medical intelligent diagnosis task of breast cancer classification, model performance largely relies on how well the hyperparameters are configured. Traditional hyperparameter approaches lack efficiency, easily fall into local optima, and face difficulties in achieving global optimization within complex search spaces. To this end, this work presents a novel meta-heuristic algorithm, the PEAO, which aims to increase the efficiency and stability of hyperparameter optimization in breast cancer classification tasks. Based on the original EAO, PEAO introduces three key mechanisms: (1) Parallel strategy: dividing the population into multiple subpopulations for parallel search in independent spaces to enhance global exploration capabilities; (2) Multi-strategy communication mechanism: proposing and alternately applying three strategies—optimal replacement, optimal mean replacement, and circular optimal replacement—to dynamically switch between them within a fixed cycle, thereby improving information sharing efficiency and collaborative capabilities among subpopulations; (3) Introduction of the Lévy flight strategy: Utilizes the Lévy distribution to generate non-uniform long-distance jumps, effectively escaping local optima traps.

Through sensitivity analysis conducted at CEC2022, it was verified that moderate subgroup sizes yield optimal performance. Through ablation analysis conducted at CEC2022, it was verified that all three PEAO strategies positively contributed to enhancing the algorithm’s global search capability and convergence performance. In the CEC2017 benchmark test, compared with nine mainstream meta-heuristic algorithms, PEAO obtained the Best in 24 of the 30 functions, the best Mean in 19 functions, and the best STD in 18 functions, demonstrating superior robustness and stability. Box plot analysis, convergence curve analysis, exploration and development analysis, and runtime analysis further corroborate PEAO’s outstanding performance.

In practical applications, PEAO was applied to tune the main hyperparameters (NumHiddenUnits, MaxEpochs, MiniBatchSize) of the BiLSTM on the WDBC breast cancer dataset and the WBC breast cancer dataset, significantly improving classification performance. The optimized PEAO-BiLSTM model outperforms the baseline BiLSTM and models generated by eleven comparison optimizers in terms of accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, fully validating its practical value in medical intelligence.

In summary, the advantages of PEAO lie in its strong global search capability, high convergence stability, and robust ability to escape local optima. The parallel strategy allows multiple subpopulations to independently explore different regions of the search space, effectively preventing premature convergence to local optima. The multi-strategy communication mechanism, which includes best replacement, mean-best replacement, and cyclic-best replacement, enhances the efficiency of information exchange and cooperation among subpopulations, resulting in more consistent convergence performance on complex optimization problems. In addition, the introduction of the Lévy flight strategy enables random long-distance jumps, maintaining a good balance between exploration and exploitation in high-dimensional spaces. Nevertheless, PEAO also exhibits certain limitations, such as longer runtime and higher computational complexity. Compared with the original EAO, the runtime of PEAO increases mainly due to the integration of the parallel strategy, multi-strategy communication mechanism, and Lévy flight mechanism, which collectively add to the computational overhead per iteration.

In practice, this intelligent diagnostic system, based on efficient hyperparameter optimization, reduces reliance on expert experience and lowers the technical barriers and costs for deploying AI models in regions with scarce medical resources or small-scale healthcare institutions (tiny industries, such as local hospitals and primary clinics). Furthermore, as a universal optimization framework, PEAO can be applied to other practical problems such as manufacturing quality inspection, production scheduling optimization for small enterprises, and energy consumption prediction, offering low-cost, high-efficiency intelligent optimization solutions for resource-constrained industries.

Future work may explore the following directions: first, extending PEAO to a multi-objective optimization framework that simultaneously considers multiple conflicting performance criteria (e.g., accuracy, training time, and model complexity) to improve overall balance and robustness; second, applying PEAO to hyperparameter optimization challenges in other critical fields beyond the medical and health sector; third, incorporating explainable AI (XAI) components to interpret the decision-making process of the optimized model, thereby enhancing its transparency and clinical acceptability for medical diagnosis.

Data availability