Abstract

Image security is vital in sectors such as healthcare, defence, finance, and personal data exchange, where breaches of image integrity can result in severe consequences. To address this challenge, we propose a novel image encryption framework. It combines a Fractal-Fibonacci diffusion process based on the Hilbert curve, recursive scrambling guided by chaotic sequences, and a new chaotic map entitled the Two Dimensional Cosine Power Sine Coupled Map (2D-CPSCM). These components enhance randomness and ensure maximum efficiency, resistance against cryptographic attacks. The proposed two-dimensional chaotic system exhibits positive Lyapunov exponents and superior statistical properties compared to traditional systems, as demonstrated by high sample entropy, permutation entropy, and Kolmogorov entropy, confirming its hyperchaotic behaviour. The encryption system has been evaluated using extensive simulations on benchmark images. The findings demonstrate strong key sensitivity, with an entropy of 7.9994, Number of Pixel Change Rate (NPCR) of 99.6%, Unified Average Changing Intensity (UACI) of 33.47%, and Number of Bit Change Rate (NBCR) of 50%. Additionally, Structural Similarity Index Metric (SSIM) and Visual Information Fidelity (VIF) values of 1 between input and decrypted images guarantee successful decryption, whereas low Peak Signal to Noise Ratio (PSNR), SSIM, and VIF between input and encrypted images reduce information leakage. The superior security, resilience, and robustness of the 2D-CPSCM based approach against statistical, noise, and cropping attacks highlights its potential for safe multimedia transmission and useful cryptographic applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, the rapid growth of digital communication has led to extensive sharing of information in the form of digital images. Many of these images contain sensitive data, especially in domains such as healthcare, defence, satellite imaging, and intelligent transportation systems. Protecting such information has become a high priority, as the increased transmission of digital images over communication channels raises the risk of unauthorized access. To address this concern, image encryption has emerged as a crucial solution for safeguarding image data. With the rising demand for secure communication, research in the field of image cryptography has become increasingly important. Recently, researchers have shown keen interest in the field of image cryptography by exploring a wide range of techniques, such as image hiding1, image steganography2, wavelet transforms3,4, DNA and RNA based methods5,6,7,8, image compression approaches9, neural networks10, and chaos theory11,12,13. Among the various approaches, chaotic based image encryption14 has gained significant attention due to the natural characteristics of chaotic maps, such as ergodicity, randomness, and high sensitivity to initial conditions. These properties make chaotic maps ideal for designing and implementing cryptographic algorithms for digital images. Chaotic systems are generally classified into one-dimensional and multi-dimensional categories. One-dimensional chaotic maps are simple to implement and require less computation however, they often suffer from drawbacks such as a limited key space and periodicity. In contrast, multi-dimensional chaotic systems provide a larger key space and exhibit higher randomness, but they are more complex to implement and demand greater computational resources.

Two-dimensional (2D) chaotic maps have emerged as efficient tools for image encryption due to their simplicity, strong ergodicity, and large key spaces. Early models such as the classical 2D Logistic Map15, 2D-SLMM16, 2D-LASM17, and 2D-SIMM18 improved dynamical complexity while maintaining low cost. Later variants including 2D-LSCM19, and 2D-LSMCL20 enhanced randomness and robustness, while cross 2D Hyperchaotic21 and 2D-CLSS22 further strengthened ergodicity and resistance to attacks. Recent contributions such as 2D-SPCM23, 2D Cosine-Sine24, 2D-CSIM25, 2D-TFCDM26, and 2D-ILM27 emphasize lightweight computation with high security, while Li et al.28 introduced the 2D-ECSLM to expand chaotic intervals and strengthen unpredictability. Collectively, these advancements reflect a consistent trend toward richer dynamics, expanded key space, and tighter integration with permutation diffusion frameworks for robust image encryption.

Chaotic map based image encryption has evolved significantly over the past few years, with researchers progressively addressing weaknesses in randomness, key space, and computational cost. Zheng et al.29 proposed the 2D logistic–sine chaotic map (2D-LSMM) combined with DNA coding, which improved randomness, complexity, and key space compared to traditional 1D maps. However, its parameters were constrained to [0,4], limiting flexibility. Teng et al.22 overcame this limitation by developing the 2D cross-logistic sine sine chaotic map (2D-CLSS), which offered higher structural complexity and improved chaotic performance. While effective, it still relied heavily on conventional scrambling and diffusion, leaving scope for innovation in adaptive mechanisms. Demla et al.30 designed a medical image encryption scheme using an improved cosine fractional chaotic map with DNA operations, demonstrating strong robustness through NPCR, UACI, and entropy metrics. The main drawback lies in its higher computational overhead due to DNA encoding. Similarly, Dua et al.31 combined wavelet transform with Lorenz and logistic maps for key generation, achieving high security, low complexity, and resilience against cropping attacks, though its reliance on standard chaotic maps may restrict novelty. Huang et al.27 proposed a 2D ICMIC logistic modulation with Latin square permutation, reducing sequence length requirements and improving efficiency, but the method lacked extensive cryptanalytic validation. Gao et al.32 integrated a 2D discrete hyperchaotic system with parallel compressive sensing, index scrambling, and diffusion under SHA-512-based key generation. While it enhanced efficiency, compressive sensing introduces reconstruction sensitivity that may affect robustness. Yang et al.33 introduced a double image encryption method using a fractional order chaotic system with 2D compressive sensing, Zigzag confusion, and discrete wavelet transform. The scheme improved robustness and security but incurred higher computational cost due to fractional-order dynamics.

Gao et al.34 presented a parallel encryption approach using the 2D logistic Rulkov neuron map (2D-LRNM) with cross channel interaction and block wise parallelism, which enhanced efficiency and task load balancing but required large memory resources for parallel processing. Xu et al.35 developed a 2D cubic–tent map (2D-CTM) with strong chaotic behaviour, employing bit-level scrambling, chaotic flipping, and 3D Hilbert diffusion, thereby enhancing security and reducing pixel correlation. However, the increased complexity might limit real-time deployment. Zheng et al.36 proposed the 2D iterative Gaussian sine chaotic map (2D-IGSCM) combined with a 3D Hill cipher, addressing weaknesses of the classical Hill cipher and achieving high security and efficiency, though cipher dependency on key scheduling could be a potential vulnerability. Wang et al.37 designed the 2D log logistic sine chaotic map (2D-LLSCM) with a non-linear log function, achieving an enlarged chaotic range and dynamic complexity. Its joint scrambling diffusion scheme improved resistance against attacks, though its non-linear design may complicate hardware implementation. Li et al.38 proposed the 2D exponential tangent cosine system (2D-ETCS), exhibiting hyperchaos, and introduced a cross permutation based color encryption method with multiple rounds of permutation, rotation, and masking. This significantly improved security but required multiple iterations, adding to computational load. Li et al.39 introduced the 2D cross Gaussian hyper chaotic map (2D-CGHM) with dynamic polyhedra permutation and arnold diffusion (DPPAD-IE), enabling encryption of arbitrary-sized images with strong pseudo randomness. Its main limitation lies in the added algorithmic complexity compared to lightweight schemes. Based on the literature survey, to overcome the shortcomings and drawbacks of previous algorithms, we proposed a new image encryption framework. The main contributions of this research article are summarized as follows

-

A new two-dimensional chaotic map, termed the 2D-Cosine Power Sine Coupled Map, is proposed. This map exhibits strong randomness and unpredictability, supported by high statistical values such as Lyapunov exponent, permutation entropy, and sample entropy.

-

A novel recursive scrambling method is introduced, which leverages chaotic sequences to enhance the randomness and unpredictability of image encryption.

-

A new diffusion process is developed by using a Fractal Fibonacci based approach, where the fractal structure is derived from the Hilbert curve. This mechanism effectively modifies the statistical relationship between adjacent pixels in the image.

The remaining sections of this paper describe the proposed chaotic map and its performance evaluation, the fundamental building blocks of the suggested encryption scheme, followed by a detailed analysis of its performance and security.

Proposed chaotic map

Talhaiui et.al proposes an one dimensional iterative chaotic map40 which delivers maximum lyapunov exponent and randomness as in Eq. (1).

The chaotic map has its limitation wherein, for small values of \(x_{n}\) and large values of the exponent \(\beta\), the term \({x_{n}^\beta }\) approaches zero, resulting in the argument of the cosine function becoming unbounded. This leads to severe numerical instability and chaotic behaviour that is difficult to control, especially in finite precision systems. To increase randomness and chaotic area a one dimensional improved discrete cosine fractional chaotic map (1D-IDCF)41 is proposed as defined in Eq. (2).

Though it increases chaotic area and delivers high Lyapunov exponent it has certain limitations are, when \(\alpha =3\) the chaotic system has a value zero , it kills chaos leading to fixed point and lost all sensitivity to initial conditions. If x(n) nearer to zero the trigonometric cosine power can become extremely large which causes undefined behaviour in floating point computation.

To avoid such scenarios we are proposing a two dimensional Cosine Power Sine Coupled Map (CPSCM) Eq. (3) to increase randomness and unpredictability by adding a sinusoidal chaotic function which erases the situation of \(\alpha =3\) and \(\eta\) to fraction of cosine power to eliminate the denominator to zero

where

The term \(\frac{\alpha }{\alpha + 1}\) is incorporated as a coupling coefficient to ensure that the additive sinusoidal interaction remains within a bounded range, satisfying \(\left| \frac{\alpha }{\alpha + 1} \cdot \sin (\pi x) \right| < 1\) for all \(x \in [0,1]\) and \(\alpha > 0\), thereby preserving the invariant domain of the map under modular arithmetic and enabling controlled modulation of chaotic intensity with respect to \(\alpha\). To avoid singularities and ensure numerical stability in the non-linear mapping, a small positive constant \(\eta > 0\) is added to the denominator in the expression \(f(x_n) = \alpha \cos \left( \frac{\alpha }{x_n^\beta + \eta } \right)\). This guarantees that the argument of the cosine function remains finite for all \(x_n \in (0,1]\), especially when \(x_n \rightarrow 0\) and \(\beta > 1\), thereby preserving the continuity and boundedness of the chaotic system.

The proposed two dimensional chaotic system parameters are within \(\alpha\), \(\beta\) and \(\eta \in [10^{-12},10^{-4}]\) to ensure bounded dynamics and maintain numerical stability.

Performance analysis of proposed chaotic map

This section describes about proposed chaotic system and its performance analysis by considering the characteristics of chaotic map like Lyapunov exponent (LE), Bifurcation diagram, Trajectory plots, key sensitivity, Sample Entropy (SE), Permutation Entropy (PE), Correlation Dimension (CD), Kolmogorov entropy (KE), Correlation analysis, 0-1 test , NIST randomness test.

Dynamic behaviour analysis

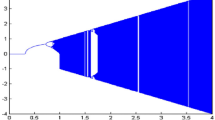

The dynamical behaviour of the proposed two-dimensional chaotic map was thoroughly examined to characterize its chaotic properties and evaluate its suitability for cryptographic applications. The bifurcation plot, shown in Fig. 1, illustrates how the system responds to variations in the control parameters \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\), revealing a wide chaotic range and rich unpredictable behaviour across the parameter space. Figure 2 presents the comparison of bifurcation diagrams of the proposed chaotic map with other existing chaotic maps presented in Table 1, where it exhibits a wider chaotic region compared to the others. Complementing this, trajectory plots Fig. 3 were used to visualize the evolution of the systems state sequences under fixed parameters. In the chaotic regime, the trajectories do not converge to periodic cycles but instead explore the entire phase space, forming an aperiodic attractor and highlighting the inherent randomness of the system. A key characteristic of chaos, the sensitivity to initial conditions, was analysed by generating sequences with slightly perturbed initial values, \((x_0, y_0) = (0.6, 0.6)\) and \((x_0, y_0) = (0.6 + 10^{-15}, 0.6 + 10^{-15})\), with \(\alpha = 2.5\) and \(\beta = 20\) over 50 iterations. As depicted in Fig. 4, even such a minimal variation leads to rapid divergence of trajectories, demonstrating high sensitivity, unpredictability, and strong chaotic characteristics.

To quantitatively measure this divergence, the Lyapunov exponents (LEs) of the system were computed. LEs quantify how fast two initially close trajectories diverge, and a positive LE indicates chaos. For an n-dimensional system, the i-th Lyapunov exponent is calculated as Eq. (4)

where \(\lambda _i(J_k)\) is Jacobian matrix \(J_k\) eigenvalues at iteration k. The Jacobian matrix of the system is defined in Eq. (5)

and the eigenvalues satisfy the characteristic equation in Eq. (6)

For hyperchaotic systems, having more than two positive Lyapunov exponents further confirms strong chaotic behaviour.

Lyapunov exponent numerical calculation

The partial derivative calculations of the proposed 2D-CPSCM are

considering

Similarly,

Hence the Jacobian is simplified to

Evaluating at the representative point \((x_n, y_n) = (0.131, 0.124)\) with parameters \(\alpha = 3\), \(\beta = 2\), and \(\eta = 0.0001\):

Thus,

To find the the eigenvalues , the characteristic equation

the characteristic equation now as

The corresponding eigenvalues are \(\lambda _1 \approx 879.28,\; \lambda _2 \approx 825.77.\).

The local Lyapunov exponents (LE) for the proposed chaotic map is given by

Thus, \(LE_1 = \ln (879.28) = 6.779,\; LE_2 = \ln (825.77) = 6.716.\)

As both \(LE_1\) and \(LE_2\) are positive, at \((x_n, y_n) = (0.131, 0.124)\) confirms the hyper chaotic nature of the proposed chaotic map.

The calculated LEs of the proposed map Fig. 5a, b are positive, which confirms the high divergence and unpredictability observed in the phase trajectories and initial sensitivity analysis. Together, these analyses confirm that the proposed chaotic map exhibits robust, aperiodic, and highly unpredictable behaviour, making it suitable for secure cryptographic applications where both randomness and sensitivity are critical. Furthermore, Fig. 5c, d present a comparative analysis between the proposed chaotic map and several existing two-dimensional maps, namely the 2D Cosine–Sine Map (CSM) 24, 2D-CSIM 25, 2D-TFCDM 26, 2D-ILM 27, and 2D-CTM 35. The evaluation is carried out for both x and y sequences under variations in the control parameters of each chaotic system while maintaining the same initial conditions \((x_0, y_0) = (0.131, 0.124)\). The results clearly indicate that the proposed two-dimensional chaotic map achieves higher Lyapunov exponent values compared to the other benchmark maps, thereby confirming its superior chaotic behaviour.

Fixed point stability analysis

For a dynamical system a fixed point42 is a point where the next state output is equal to the current output i,e \(x_{n+1}=x_n\). If a point \(x^*\) is said to be equilibrium point of a chaotic map then \(x^*=f(x^*)\). For the proposed two dimensional chaotic map assume \(S(x^*,y^*)\) be fixed point then it satisfies \(x_{n+1}=x*\) and \(y_{n+1}=y*\), from Eq.3

where

A fixed point \((x^*,y^*)\) satisfies the nonlinear system

The stability analysis of each fixed point like S(X,Y) of the proposed chaotic system is determined by by deriving Jacobian matrix Eq. (20)

The corresponding characteristic polynomial of \(J\) is

The corresponding eigenvalues are determined by finding the roots for equation

where \(\operatorname {Trace}(J)=J_{11}+J_{22}\) and \(\det (J)=J_{11}J_{22}-J_{12}J_{21}\).

The stability classification the proposed map of infinite fixed points is depends on the magnitude of eigenvalues \(\lambda _1\) and \(\lambda _2\) of Eq. (22) as

-

1.

If both eigenvalues are\(|\lambda _1|<1\) and \(|\lambda _2|<1\) then S(X,Y) is stable fixed point ,

-

2.

The eigenvalues\(|\lambda _1|>1\) or \(|\lambda _2|>1\), then S(X,Y) unstable fixed point ,

-

3.

If \(|\lambda _1|<1\) and \(\lambda _2=-1\) (or vice versa) then the fixed point S(X,Y) is called as period-doubling bifurcation point (PBP),

-

4.

If \(|\lambda _{1,2}|=1\) with \(\operatorname {Re}(\lambda _{1,2})<1\) then the fixed point S(X,Y) is Neimark–Sacker bifurcation point (NBP).

To analyse the fixed point behaviour of the proposed chaotic map in the \(x\text {-}y\) phase plane, the system parameters are set as \((\alpha , \beta , \eta ) = (1.5, 40, 10^{-8})\) and \((2.5, 20, 10^{-8})\). The corresponding phase attractors are shown in the Fig. 6, where red filled circles denote unstable fixed points with eigenvalues \(|\lambda | > 1\), and dense tiny coloured dots represent chaotic trajectories around them. To determine the attractor type, trajectories are generated with slight perturbation in the unstable fixed points, all converging to the same chaotic region without specific initial conditions. The existence of multiple unstable fixed points with bounded chaotic trajectories confirms that the system exhibits self excited chaotic attractors, as the trajectories originate directly from the neighbourhood of the unstable fixed points.

Complexity and randomness measures

The complexity and randomness of the proposed two-dimensional chaotic map were evaluated using Sample Entropy (SE), Permutation Entropy (PE), and Kolmogorov Entropy (KE) to assess the unpredictability and information richness of the generated sequences. Sample Entropy measures the irregularity and intricacy of time series sequences by counting the number of identical patterns within a acceptable threshold. For a time series \(\{y_1, y_2, \ldots , y_n\}\), the SE is defined as Eq. (23)

where E and F are the counts of vector pairs satisfying the inequalities \(G[Y_{r+1}(i),Y_{r+1}(j)] < d\) and \(G[Y_r(i),Y_r(j)] < d\), respectively, with \(G[\cdot ]\) representing the Chebyshev distance between vectors \(Y_r(i) = \{y_i, y_{i+1}, \ldots , y_{i+r-1}\}\). For the proposed system, the embedding dimension \(r=2\) and threshold \(d=0.2 \times \text {STD}\), where STD is the standard deviation of the series. Figure 7 demonstrates that the SE values of the proposed map for x and y sequences are significantly higher than those of benchmark chaotic maps, indicating strong aperiodicity and pseudo-randomness.

Permutation Entropy (PE) further quantifies the unpredictability of the system by evaluating the probability distribution of ordinal patterns in the sequences. The normalized PE is computed as Eq. (24)

where \(p(x_i)\) denotes the probability of each ordinal pattern. The proposed map achieves an average PE of 0.852, near to the theoretical maximum of 1, which is higher and more stable than other contemporary two-dimensional chaotic systems Fig. 8. This indicates enhanced randomness and unpredictability, reinforcing its suitability for secure encryption.

Kolmogorov Entropy (KE) complements SE and PE by quantifying the rate of information generation within the system. Mathematically, KE is expressed as Eq. (25)

where the n-dimensional phase space is partitioned into boxes \((i_0, i_1, \ldots , i_n)\) of size \(\varepsilon\), \(\tau\) is the temporal delay, and \(p(i_1, \ldots , i_n)\) is the joint probability of the trajectory occupying the corresponding boxes. A positive KE reflects high unpredictability, and Fig. 9 illustrates KE variations with \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\). The proposed chaotic map achieves an average KE of 7.3159, confirming both high unpredictability and stable chaotic behaviour. Collectively, SE, PE, and KE analyses demonstrate that the proposed system generates complex, highly unpredictable sequences suitable for robust cryptographic applications.

Correlation and statistical analysis

To further evaluate the statistical properties and complexity of the proposed two-dimensional chaotic map, autocorrelation, cross-correlation, and correlation dimension analyses were performed. Autocorrelation quantifies the similarity of a time series with itself at different lags, while cross-correlation measures the similarity between two distinct sequences as a function of displacement \(\tau\). Mathematically, these are defined as Eq. (26)

where \(r_{xx}\) and \(r_{xy}\) denote the autocorrelation and cross-correlation, respectively, N is the number of points in each series, and \(\mu _x\) and \(\mu _y\) are the mean values of x(t) and y(t). Figure 10a and b illustrate the autocorrelation of the x and y sequences, showing a prominent spike at lag 0 and near-zero values at other lags, confirming the absence of significant self-similarity and the generation of aperiodic sequences. The cross-correlation between the two sequences, depicted in Fig. 10c, exhibits a near-zero zigzag pattern, indicating that x and y are highly uncorrelated and statistically independent.

The correlation dimension (CD) provides a quantitative measure of the attractor’s fractal complexity in the phase space. It is calculated through the integral of correlation \(C_e(r)\) as Eq. (27)

Higher CD values correspond to more complex and irregular behavior, indicating that the time series spans a higher-dimensional phase space. The three-dimensional visualization of CD, shown in Fig. 11, confirms that the proposed chaotic map exhibits rich and diverse dynamics. Collectively, autocorrelation, cross-correlation, and correlation dimension analyses validate that the sequences generated by the proposed system are statistically independent, aperiodic, and highly complex, reinforcing their suitability for cryptographic applications.

Chaos validation and randomness testing

To further validate the chaotic nature and cryptographic suitability of the proposed two-dimensional map, both the 0-1 test and NIST statistical test suite were employed. The 0-1 test provides a sensitive measure of chaos directly from time series data, without requiring phase space reconstruction. For a sequence u(n), the auxiliary variables p(n) and q(n) are defined as Eq. (28)

where c is a constant in the interval \((0, 2\pi )\). This leads to Eq. (29)

and the mean square displacement is calculated as Eq. (30)

The asymptotic growth rate is Eq. (31)

indicates chaos when K approaches 1, and regular dynamics when K is close to 0. For the proposed map, with \(\alpha = 2.5\), \(\beta = 20\), and initial values \((x_0, y_0) = (0.131, 0.124)\), the 0-1 test results Fig. 12 show (p, q) trajectories resembling Brownian motion, and the K values for x and y sequences are 0.9077 and 0.9081, respectively, confirming hyperchaotic behaviour.

In addition, the NIST statistical test suite was employed to rigorously evaluate the randomness and unpredictability of the generated sequences. This suite consists of 15 subtests examining different aspects of statistical randomness, with outcomes expressed as p-values. Sequences are considered random if the p-values exceed 0.01. As summarized in Table 2, all p-values for the proposed chaotic map sequences surpass this threshold, confirming strong randomness, unpredictability, and suitability for cryptographic applications. Collectively, the 0-1 test and NIST results validate that the proposed map exhibits robust chaotic dynamics and produces highly unpredictable sequences.

Furthermore, the comparative analysis of the proposed chaotic map with other systems, in terms of statistical measures reported in Table 3, indicates that the proposed two-dimensional chaotic map delivers superior values for LE, Asymptotic growth rates (\(K_1,K_2\)), CD and KE, while achieving approximately equal performance for the remaining metrics. These results confirm the effectiveness and competitiveness of the proposed chaotic system.

Proposed encryption scheme

This section presents the proposed encryption algorithm, outlining its fundamental building blocks and their integration in transforming an input image into a highly randomized encrypted image. The overall process is illustrated in the flowchart shown in Fig. 13.

Self adaptive prime modulo based Hashing algorithm

The proposed self-adaptive prime-modulo block hashing method partitions an image into dynamically assigned hash blocks and iteratively refines their distribution using a feedback-driven mechanism. Given an input image I of size \(m \times n\), it is first converted to grayscale, flattened into a one-dimensional sequence, and the number of hash blocks is defined as \(B = \min (m,n)\). To ensure uniform and collision-resistant mapping, the smallest prime \(q \ge mn\) is selected as the modular space. This process starts with two secret seeds \(r_{\text {ini}}\) and \(s_{\text {ini}}\) are converted into integer keys r and s as Eq. (32)

which control the initial pixel-to-block allocation through the hash function defined by Eq. (33)

where i is the pixel index in the flattened sequence. Each pixel is assigned to a block h(i), and after all pixels are distributed, block statistics such as the total sum \(S_{\text {total}} = \sum _{b=1}^{B} \sum _{x \in \mathscr {B}_b} x\) and cumulative standard deviation \(\sigma _{\text {total}} = \sum _{b=1}^{B} \sigma (\mathscr {B}_b)\) are computed. These statistics are fed back to update the hash keys across rounds using Eq. (34)

which introduces adaptivity and ensures that even minor variations in the image propagate across multiple iterations. After a predefined number of rounds, this feedback mechanism yields a highly irregular and content dependent block structure that enhances confusion and diffusion properties, making it well suited for cryptographic applications such as chaotic initialization, DNA based diffusion, or permutation driven image encryption. The step wise implementation of this procedure is summarized in Algorithm 1.

Entropy based key generation

This section describes the generation of control parameters for the proposed chaotic system based on the blocks generated from self adaptive prime modulo based hashing algorithm. In this step each block entropy is calculated and concatenated into a one dimensional vector to apply to SHA-256 hash algorithm, and convert this 256 bit hash value into 512 bit binary number and group onto 64 groups and calculate the control parameters.

The generation of image-dependent chaotic keys is performed in five sequential steps as described below.

Step 1: The input image is initially partitioned into B non-overlapping pixel blocks using self adaptive block hashing algorithm 1 and the Shannon entropy of each block is computed as Eq. (35)

where \(p_i^{(b)}\) is i-th intensity in block \(\mathscr {B}_b\) probability. The resulting entropy vector is Eq. (36)

Step 2: The entropy vector E is fed to SHA-256 algorithm producing a 256-bit digest. The digest is represented as a 512-bit binary sequence, which is further divided into 64 consecutive 8-bit segments as Eq. (37)

Step 3: Each 8-bit group \(K_i\) is converted into its decimal representation using Eq. (38)

Step 4: To mix entropy across different positions, four aggregate integers are obtained using XOR folding as Eq. (39)

where \(\oplus\) denotes bitwise XOR.

Step 5: Finally, the XOR-folded integers are mapped to the initial conditions and control parameters of the chaotic system as Eq. (40)

The tuple \((x_0, y_0, \alpha , \beta )\) serves as the final chaotic key, which generates the chaotic sequences of length \(m \times n\), and is modified according to Eqs. (41) and (42) for the usage of subsequent encryption stages. Here consider \(\eta = 10^{-8}\) as constant for generation of chaotic sequences.

where \(\lfloor .\rfloor\) indicates floor operation.

Recursive chaotic based block scrambling

Traditional image scrambling methods such as row column shuffling, zigzag scanning, Arnold cat maps, and global chaotic permutations offer basic obfuscation but suffer from limited key space, predictable structures under chosen plaintext attacks, weak entropy diffusion, and low resistance to local statistical analysis. To overcome these shortcomings, we propose a Recursive Chaotic Scrambling scheme that leverages fractal inspired quadtree decomposition and chaotic key driven geometric transformations for multi-scale disruption of spatial dependencies.

Given an input image block \(\textbf{I} \in \mathbb {Z}^{N \times N}\), the algorithm recursively partitions it into four sub blocks \(\{\textbf{Q}_1,\textbf{Q}_2,\textbf{Q}_3,\textbf{Q}_4\}\) at each recursion level \(\ell\), where a chaotic key vector \(\textbf{x}\) from Eq. (41) assigns a transformation index \(k = \textbf{x}[4(\ell -1)+i],~i\in \{1,2,3,4\}\). Each partitioned sub block then undergoes a reversible operation horizontal/vertical flip, \(90^\circ\)/\(180^\circ\) rotation, or transposition while \(k=1\) leaves the block unchanged. After local transformation, the blocks are recursively processed up to a maximum depth L and recombined to form the scrambled output \(\textbf{O}\). This whole process is explained in Algorithm 2.

This hierarchical strategy breaks coarse structures in early levels and fine pixel correlations in deeper levels, yielding multilevel permutation with high sensitivity to initial keys. The combined use of flips, rotations, and transpositions enhances permutation entropy, enlarges the key space, and provides high resistance to statistical and differential attacks, while remaining lightweight and fully reversible for seamless integration with subsequent diffusion stages in secure image encryption.

Fractal Fibonacci fusion diffusion

The proposed Fractal Fibonacci Fusion Diffusion scheme enhances image encryption by combining fractal-space traversal with Fibonacci inspired recursive diffusion. First, the input scrambled image \(O \in \mathbb {Z}^{M \times N}\) is linearized into a one-dimensional sequence P using a Hilbert space filling curve of order \(\log _2 N\) as shown in Fig. 14, which preserves local neighbourhood relations while introducing a fractal mapping that disperses spatial correlations.

Unlike raster scans and zig-zag scans, the Hilbert traversal ensures that 2D neighbours remain close in 1D, enabling local perturbations to propagate globally during diffusion. The chaotic sequence y from Eq. (42) generated from the key dependent system. The diffusion follows the Fibonacci inspired recursion, where the first two pixels are updated as Eq. (43)

and each subsequent pixel for \(i \ge 3\) is computed as Eq. (44)

This recursive fusion ensures that every pixel depends on its two predecessors and the chaotic input, amplifying sensitivity to both plaintext and keys. Finally, the diffused 1D sequence is remapped to 2D using the inverse Hilbert curve, yielding the final diffused image \(C_{\text {cipher}}\) as described in Algorithm 3. By jointly leveraging fractal space filling traversal, Fibonacci style dependency, and chaotic modulation, this lightweight diffusion achieves high entropy, strong nonlinearity, and robust resistance against statistical and differential attacks.

Simulation and security analysis

This section presents the simulation results and security analysis of the proposed encryption algorithm, implemented using MATLAB 2023a. For evaluation, we considered ten different grayscale images from diverse categories, including Chemical Plant, Golden Gate, Couple, Boat, Baboon, Pentagon, and Male from the SIPI database43, Brain Tumour44, Chest CT Scan45, and Berry from the RSSCN7 dataset46. These images collectively represent a wide range of content, including natural, medical, aerial, and remote sensing images.

Visual evaluation

Visual evaluation illustrates the input, encrypted, and reconstructed images. An effective encryption scheme should produce an encrypted image with no recognizable information and a decrypted image closely resembling the original. Figure 15 shows the histogram analysis: the input image exhibits distinct peaks representing data distribution, the encrypted image histogram is flat and uniform, resembling noise, and the decrypted image histogram closely matches the original. These results confirm the proposed scheme’s effectiveness in obscuring visual information while preserving recoverability.

Entropy-based analysis

Entropy-based analysis evaluates image randomness via Global Information Entropy (GIE) and Local Information Entropy (LIE). GIE measures overall image entropy, while LIE computes the average GIE of randomly selected non-overlapping blocks. GIE is calculated as Eq. (45)

where L is the maximum intensity level and \(p(x_i)\) the probability of intensity \(x_i\). LIE is given by Eq. (46)

with k randomly selected blocks \(B_i\), each containing \(T_B\) pixels. For our analysis, \(k=30\) and \(T_B=1936\). At a \(5\%\) significance level, an image passes if LIE lies within \((7.9019,\,7.9030)\). As summarized in Table 4, the input image exhibits lower GIE than the encrypted image, and its LIE falls outside the interval, whereas encrypted images meet the LIE criterion. This confirms that the proposed encryption ensures strong global and local randomness.

Pixel level statistical analysis

This section evaluates the proposed encryption scheme visually and statistically using histogram variance analysis and the Chi-square test. Histogram analysis shows pixel distribution, the original image exhibits peaks revealing information, while the encrypted image is uniform, preventing data leakage. The Chi-square statistic is computed as Eq. (47)

Here \(o(i)\) is observed and \(e(i)\)is expected frequency of pixel intensity i. The variance of histogram is calculated by Eq. (48)

Here \(f_i\) and \(f_j\) are the histogram frequencies at gray levels i and j. Table 5 reports variance and Chi-square results for original and encrypted images. The encrypted images show significantly lower variance and \(\chi ^2\) values, satisfying \(\chi ^2 < 293.2478\), indicating a uniform pixel distribution. These results confirm strong randomness in the encrypted images, enhancing the security of the proposed scheme.

Statistical analysis

The proposed encryption algorithm is further evaluated using statistical metrics, Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), and Visual Information Fidelity (VIF), which quantify distortion during encryption and reconstruction quality during decryption. These are defined as in Eq. (49)

Table 6 presents the results. PSNR, SSIM, and VIF values are very low between the original and encrypted images, confirming strong security, and very high between the original and decrypted images (PSNR \(\rightarrow \infty\), SSIM and VIF \(\approx 1\)), indicating near perfect reconstruction. This demonstrates that the proposed scheme ensures both confidentiality and faithful image recovery.

Correlation between adjacent pixels analysis

Original images exhibit high correlation between adjacent pixels in horizontal, vertical, and diagonal directions, making them vulnerable to statistical attacks. Reducing this correlation is essential for security. The correlation coefficient (CC) between adjacent pixels \(u_i\) and \(v_i\) is computed using Eq. (50)

where \(\bar{u}\) and \(\bar{v}\) are the mean values. Figure 16 shows that original image pixels cluster closely, indicating strong correlation, whereas encrypted image pixels are widely scattered in all three directions. Table 7 confirms that correlation coefficients for encrypted images are near zero, demonstrating minimal adjacent-pixel dependency and enhanced security.

Differential attack analysis

Differential Attack analysis is well known attack test to measure the vulnerability of crypto system. In this analysis two images with slightly differentiate in the features are subjected to undergo encryption process to get two cipher images known as \(E_1\) and \(E_2\). The ability to withstand differential attack of the proposed crypto algorithm is measured by calculating how many number of pixels are differed between two cipher images \(E_1\) and \(E_2\). This difference of pixels are quantified by two statistical metrics known as Number of Pixel Change Rate(NPCR) and Unified Average Changing Intensity(UACI) are calculated using Eqs. (51) and (52) respectively

Table 8 presents the statistical results of differential attack analysis by measuring NPCR and UACI. From the table, it is evident that the average values of NPCR exceed \(99.6\%\) and UACI exceed \(33.4\%\), which indicates that the proposed algorithm exhibits strong randomness and a high resistance to differential attacks.

Additionally, we compared the statistical values of the Baboon image derived using the proposed encryption algorithm with those from previous algorithms. The results, summarized in Table 9, demonstrate that the proposed algorithm achieves superior performance.

Robustness analysis

To evaluate robustness against transmission errors and attacks41, noise and data loss were simulated on encrypted images. Noise of varying types and densities was added, and portions of encrypted images were cropped, followed by decryption. Figure 17 shows that decrypted images remain recognizable despite noise, with PSNR values in Table 10 decreasing as noise density increases, reflecting reduced resemblance. Similarly, Fig. 18 illustrates that even with cropped portions, decrypted images preserve recognizable content, with PSNR values reported in Table 11. These outcomes confirm the proposed encryption approach resilience against noise and partial data loss.

Key sensitivity and space analysis

Key sensitivity was evaluated using the Berry test image, where encryption and decryption were performed with both the original key and slightly modified keys. As shown in Fig. 19, successful decryption occurs only with the exact key, while even minimal key variations produce unrecognizable outputs, confirming strong key sensitivity. Quantitatively, robustness is measured using the Number of Bit Change Rate (NBCR), defined as Eq. (53)

where Ham(.) denotes the Hamming distance between two matrices \(b_1\) and \(b_2\), and \(length\) represents the total number of bits. Figure 20 illustrates the total number of bit changes between two encrypted images \(E_1\) and \(E_2\), as well as two decrypted images \(D_1\) and \(D_2\), obtained using keys \(key_1\) and \(key_2\), respectively. For each round, the NBCR is approximately 50%, indicating that the proposed encryption algorithm is robust against small key variations, which in turn ensures high randomness in the resulting images.

In addition, the key space analysis and its comparison are summarized in Table 12. Considering the seven parameters random initial seeds(\(r_{ini},s_{ini}\)), \(\alpha\), \(\beta\), \(\eta\), and the initial values(\(x_0,y_0\)) of the chaotic map represented in double-precision floating-point format with approximately \(10^{-15}\) resolution, the total key space is approximately \(2^{348}\). This value is significantly greater than \(2^{100}\), making it suitable for cryptographic applications.

Time complexity analysis

The proposed algorithm consists of four linear components block hashing, entropy-based key generation, chaotic sequence generation, and Fibonacci diffusion each with complexity O(MN). In addition, recursive scrambling and Hilbert traversal introduce two quasi-linear terms, each \(O(MN \log M)\), due to hierarchical recursion and fractal path computation. Thus, the overall complexity is \(4O(MN) + 2O(MN \log M) \approx O(MN \log M)\), where the logarithmic factor dominates. This quasi-linear cost is only slightly higher than purely linear schemes, but it significantly improves security by enhancing permutation strength and diffusion robustness, making the trade-off both efficient and defensible. Further, Table 13 presents encryption and decryption times (seconds) for different image sizes, \((256 \times 256)\) and \((512 \times 512)\). It also presents time complexity and compares it with existing algorithms. Our proposed algorithm took 1.2455 s (encryption) and 1.3255 s (decryption) for \((256 \times 256)\) images and 6.045 s (encryption) and 6.241 s (decryption) for \((512 \times 512)\) images. This time complexity for encryption is slightly higher when compared to existing algorithms due to recursive scrambling but within acceptable bounds considering the stronger diffusion.

Conclusion

This study introduced a novel image encryption framework that integrates chaotic-based recursive scrambling with a Fractal–Fibonacci diffusion mechanism derived from the Hilbert curve. At its core lies a new two-dimensional chaotic system, the 2D-CPSCM, which exhibits positive LEs, confirming its hyperchaotic nature. The proposed system outperforms existing chaotic maps in statistical measures, including SE, PE and KE. Comprehensive experiments on multiple benchmark images demonstrate the robustness of the scheme, achieving strong performance in entropy, CC, NPCR, UACI, and NBCR metrics. In addition, its resistance to noise and cropping attacks further validates the resilience of the approach. Although the algorithm introduces higher computational complexity, this trade-off is justified by the enhanced security, improved randomness, and strong resistance to cryptographic attacks, making the proposed approach is suitable for secure multimedia communication. noise and cropping attack tests further validate the resilience of the scheme. Although the complexity of the algorithm increases, this trade-off is justified by the enhanced security and improved randomness in the encrypted images.

Data availability

The corresponding author can provide the data validating the study’s conclusions upon reasonable request.

References

Guan, Z. et al. Deepmih: Deep invertible network for multiple image hiding. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 45, 372–390 (2022).

Li, Q., Ma, B., Wang, X., Wang, C. & Gao, S. Image steganography in color conversion. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 71, 106–110 (2023).

Hazzazi, M. M. et al. Enhancing image security via chaotic maps, Fibonacci, Tribonacci transformations, and dwt diffusion: A robust data encryption approach. Sci. Rep. 14, 12277 (2024).

Anand, A. & Singh, A. K. Hybrid nature-inspired optimization and encryption-based watermarking for e-healthcare. IEEE Trans. Computat. Soc. Syst. 10, 2033–2040 (2022).

Feng, S., Zhao, M., Liu, Z. & Li, Y. A novel image encryption algorithm based on new one-dimensional chaos and DNA coding. Multimed. Tools Appl. 83, 84275–84297 (2024).

Allawi, S. T. & Alshibani, D. R. Color image encryption using LFSR, DNA, and 3d chaotic maps. Int. J. Electric. Comput. Eng. Syst. 13, 885–893 (2022).

Zhou, S., Wei, Y., Zhang, Y., Iu, H.H.-C. & Zhang, H. Image encryption algorithm based on the dynamic RNA computing and a new chaotic map. Integration 101, 102336 (2025).

Belete, B. A., Gelmecha, D. J. & Singh, R. S. Secure image transmission in wireless sensor networks using DNA coding and memcapacitor-based hyperchaotic system for encryption and decryption. Iran J. Comput. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42044-025-00328-7 (2025).

Yang, Y., Cheng, M., Ding, Y. & Zhang, W. A visually meaningful image encryption scheme based on lossless compression Spiht coding. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 16, 2387–2401 (2023).

Lai, Q., Yang, L., Hu, G., Guan, Z.-H. & Iu, H.H.-C. Constructing multiscroll memristive neural network with local activity memristor and application in image encryption. IEEE Trans. Cybernet. 54, 4039–4048 (2024).

Feng, W. et al. Exploiting newly designed fractional-order 3d Lorenz chaotic system and 2d discrete polynomial hyper-chaotic map for high-performance multi-image encryption. Fract. Fract. 7, 887 (2023).

Wang, Y., Chen, L., Yu, K. & Fu, T. A secure Spatio-temporal chaotic pseudorandom generator for image encryption. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 34, 8509–8521 (2024).

Huang, L. & Gao, H. Multi-image encryption algorithm based on novel spatiotemporal chaotic system and fractal geometry. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 71, 3726–3739 (2024).

Belete, B. A., Gelmecha, D. J. & Singh, R. S. Image encryption algorithm based on a memcapacitor-based hyperchaotic system and DNA coding. Secur. Privacy 7, e432. https://doi.org/10.1002/spy2.432 (2024).

Wu, Y., Yang, G., Jin, H. & Noonan, J. P. Image encryption using the two-dimensional logistic chaotic map. J. Electron. Imaging 21, 013014–013014 (2012).

Hua, Z., Zhou, Y., Pun, C.-M. & Chen, C. P. 2d sine logistic modulation map for image encryption. Inf. Sci. 297, 80–94 (2015).

Hua, Z. & Zhou, Y. Image encryption using 2d logistic-adjusted-sine map. Inf. Sci. 339, 237–253 (2016).

Liu, W., Sun, K. & Zhu, C. A fast image encryption algorithm based on chaotic map. Opt. Lasers Eng. 84, 26–36 (2016).

Hua, Z., Jin, F., Xu, B. & Huang, H. 2d logistic-sine-coupling map for image encryption. Signal Process. 149, 148–161 (2018).

Zhu, H., Zhao, Y. & Song, Y. 2d logistic-modulated-sine-coupling-logistic chaotic map for image encryption. IEEE Access 7, 14081–14098 (2019).

Teng, L., Wang, X., Yang, F. & Xian, Y. Color image encryption based on cross 2d hyperchaotic map using combined cycle shift scrambling and selecting diffusion. Nonlinear Dyn. 105, 1859–1876 (2021).

Teng, L., Wang, X. & Xian, Y. Image encryption algorithm based on a 2d-CLSS hyperchaotic map using simultaneous permutation and diffusion. Inf. Sci. 605, 71–85 (2022).

Tang, J. et al. Novel asymmetrical color image encryption using 2d sine-power coupling map. Nonlinear Dyn. 112, 11547–11569 (2024).

Dhingra, D. & Dua, M. Medical video encryption using novel 2d cosine-sine map and dynamic DNA coding. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 62, 237–255 (2024).

Tang, J., Zhang, Z. & Huang, T. Two-dimensional cosine-sine interleaved chaotic system for secure communication. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 71, 2479–2483 (2023).

Patel, S., Thanikaiselvan, V. & Rearajan, A. Secured quantum image communication using new two dimensional chaotic map based encryption methods. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 63, 49 (2024).

Huang, X., Tang, J. & Zhang, Z. Efficient and secure image encryption algorithm using 2d LIM map and latin square matrix. Nonlinear Dyn. 112, 22463–22483 (2024).

Li, L. A self-reversible image encryption algorithm utilizing a novel chaotic map. Nonlinear Dyn. 113, 7351–7383 (2025).

Zheng, J. & Liu, L. Novel image encryption by combining dynamic DNA sequence encryption and the improved 2d logistic sine map. IET Image Proc. 14, 2310–2320 (2020).

Demla, K. & Anand, A. Miewc: Medical image encryption using wavelet transform and multiple chaotic maps. Secur. Privacy 7, e369 (2024).

Dua, S., Kumar, A., Dua, M. & Dhingra, D. Icfcm-mie: Improved cosine fractional chaotic map based medical image encryption. Multimed. Tools Appl. 83, 52035–52060 (2024).

Gao, Y., Liu, J. & Chen, S. Image encryption algorithms based on two-dimensional discrete hyperchaotic systems and parallel compressive sensing. Multimed. Tools Appl. 83, 57139–57161 (2024).

Yang, Y.-G. et al. A new visually meaningful double-image encryption algorithm combining 2d compressive sensing with fractional-order chaotic system. Multimed. Tools Appl. 83, 3621–3655 (2024).

Gao, S. et al. A parallel color image encryption algorithm based on a 2d logistic-Rulkov neuron map. IEEE Internet of Things Journal (2025).

Xu, X.-L., Song, X.-G., Liu, S.-H., Zhou, N.-R. & Wang, M.-M. New 2d hyperchaotic cubic-tent map and improved 3d Hilbert diffusion for image encryption. Appl. Intell. 55, 590 (2025).

Zheng, Y., Huang, Q., Cai, S., Xiong, X. & Huang, L. Image encryption based on novel hill cipher variant and 2d-IGSCM hyper-chaotic map. Nonlinear Dyn. 113, 2811–2829 (2025).

Wang, M.-M., Song, X.-G., Liu, S.-H., Zhao, X.-Q. & Zhou, N.-R. A novel 2d log-logistic-sine chaotic map for image encryption. Nonlinear Dyn. 113, 2867–2896 (2025).

Li, Z., Zhang, S., Tan, W. & Wu, X. Enhanced secure color image encryption using a novel hyperchaotic 2d-etcs model and cross-permutation. Nonlinear Dyn. 113, 18833–18855 (2025).

Li, Q. et al. Dppad-ie: Dynamic polyhedra permutating and arnold diffusing medical image encryption using 2d cross gaussian hyperchaotic map. IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics (2025).

Talhaoui, M. Z., Wang, X. & Talhaoui, A. A new one-dimensional chaotic map and its application in a novel permutation-less image encryption scheme. Vis. Comput. 37, 1757–1768 (2021).

Kumar, M. & Ch, D. Enhancing image security through a fusion of chaotic map and multi-level scrambling techniques. SIViP 19, 235 (2025).

Bao, H. et al. Grid homogeneous coexisting hyperchaos and hardware encryption for 2-d HNN-like map. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 71, 4145–4155. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSI.2024.3423805 (2024).

University of Southern California, Signal and Image Processing Institute. Usc-sipi image database. http://sipi.usc.edu/database/ (1977). Accessed: 25 August 2025.

Dubail, T. Brain tumors 256\(\times\)256. Dataset on Kaggle (2023). Accessed: 25 August 2025.

Hany, M. Chest ct-scan images dataset. Dataset on Kaggle (2023). Accessed: 25 August 2025.

Zou, T., Ni, J., Gao, Y. & Chen, Z. Rsscn7: A remote sensing image dataset for scene classification. http://www.lmars.whu.edu.cn/xia/AID/AID.html (2015). Accessed: 25 August 2025.

Bayari, P. V. B., Sangwan, Y., Bhatnagar, G. & Chattopadhyay, C. A novel chaotic map and its application to secure transmission of multimodal images. IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems (2025).

Kumar, S. & Sharma, D. A chaotic based image encryption scheme using elliptic curve cryptography and genetic algorithm. Artif. Intell. Rev. 57, 87 (2024).

Bao, H. et al. Grid homogeneous coexisting hyperchaos and hardware encryption for 2-d hnn-like map (Regular Papers, IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems I, 2024).

Liu, X., Sun, K. & Wang, H. A novel image encryption scheme based on 2d silm and improved permutation-confusion-diffusion operations. Multimed. Tools Appl. 82, 23179–23205 (2023).

Zhang, H., Hu, H. & Ding, W. Image encryption algorithm based on Hilbert sorting vector and new spatiotemporal chaotic system. Opt. Laser Technol. 167, 109655 (2023).

Lone, M. A. & Qureshi, S. Encryption scheme for RGB images using chaos and affine hill cipher technique. Nonlinear Dyn. 111, 5919–5939 (2023).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Vellore Institute of Technology- AP University. Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Maram Kumar: Conceptualization, Simulated the experiments, Performed the analysis, Wrote the original draft; Deepak Ch: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, validation, review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kumar, M., Ch, D. 2D-Cosine power sine coupled map with fractal-Fibonacci fusion for hyperchaotic image encryption. Sci Rep 16, 3562 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33552-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33552-z