Abstract

The present study investigates the flexural capacity of high-performance ductile concrete (HPDC) beams, with a focus on their reliability for large-scale applications. Due to the high fiber volume fraction in the HPDC mixture, a very low reinforcement ratio (almost negligible) was employed to address challenges related to fiber congestion in areas with heavy steel reinforcement. To compensate for this low ratio, various strengthening techniques were evaluated on ten large-scale HPDC beams, including differing configurations of carbon fiber-reinforced polymer (CFRP) sheets and post-tensioning methods. The primary parameters assessed included ultimate flexural capacity, ductility ratio, absorbed energy, stiffness, first cracking load, and maximum deflection, alongside reference specimens for comparative analysis. The results indicated that while the reference beam exhibited sufficient flexural capacity to meet the minimum requirements outlined in the design codes, it displayed an inappropriate cracking pattern and low absorbed energy. Conversely, the application of strengthening methods resulted in a significant enhancement of flexural capacity, a considerable reduction in the width of failure cracks, and an increase in the number of small cracks. Overall, the findings of this study demonstrate that HPDC beams, when reinforced with strengthening techniques, can effectively function as structural members even with minimal reinforcement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The use of ductile high-performance concrete (HPDC) is increasing in construction1,2. This concrete type, also referred to as ultra-high-performance ductile concrete (UHPDC)3 or ultra-high ductile concrete (UHDC)4,5, employs a low water-to-binder ratio and high fiber content. For this study, the term HPDC is adopted as the material’s compressive strength and plasticity are lower than that of ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC), as detailed in Table 1. While both HPDC and UHPC share a dense matrix design, HPDC is characterized by a compressive strength below 100 MPa and a significant, yet purposefully lower, tensile ductility of about 4% compared to UHPC. Thus, HPDC defines a practical sub-class of UHPC, optimized for high strength and measurable ductility without ultra-high performance extremes.

Extensive research has demonstrated that HPDC and HPC outperform conventional concrete in terms of flexural and impact performance2,6. Studies focused on beams have indicated that their flexural strength exceeds predictions made by existing codes7,8, with the ratio of tensile reinforcement identified as a crucial factor influencing ductility9 and cracking behavior10,11. Nonetheless, a fundamental question remains: how much can we rely on HPC concrete in reinforced concrete beams that have the minimum allowable reinforcement ratios, or potentially none at all? Determining this lower limit is vital for optimizing material usage and moving towards designs that require less rebar. While design frameworks12 and analytical techniques13 have been suggested, they have yet to effectively tackle this threshold. Additionally, recent research has called into question previous assumptions, revealing that increased fiber volumes do not invariably improve ductility14 and that UHPC can sometimes demonstrate lower ductility compared to conventional concrete, despite its fine cracking15, highlighting the urgent necessity of this study to establish the safe and effective limits of HPC usage.

The reduction or removal of longitudinal steel reinforcement in RC beams, achievable through HPDC with a high fiber volume16, provides significant benefits in project costs and constructability. Although HPDC has a higher initial material cost, it offsets expenses through reduced rebar requirements and lower installation costs. This allows for quicker construction timelines, as simpler beam cages are easier to assemble, improving concrete placement and consolidation while minimizing honeycombing and voids. The fiber matrix enhances durability and crack control, reducing permeability and maintenance costs linked to steel corrosion. This method emphasizes overall value rather than just initial costs, making it suitable for complex infrastructure projects where speed and resilience are essential. However, a key question remains: How reliable is using an HPDC beam as an independent RC member with a nearly negligible reinforcement ratio? This study considers high ductility concrete to prevent sudden collapse by absorbing loads, examining the effects of a very low longitudinal reinforcement ratio (=0.32%) with four 8 mm diameter bars, while also evaluating various strengthening techniques for DHP beams with low reinforcement ratios.

-

(1)

Is it possible to use HPDC due to its properties to create structural members with a very low reinforcement ratio (less than the minimum reinforcement ratio), which is almost negligible?

-

(2)

How efficient is the CFRP sheet strengthening method in enhancing the structural performance of the HPDC beam?

-

(3)

What is the optimum CFRP sheet strengthening method among single sheets, two layers, and U-shaped ones for strengthening HPDC beams?

-

(4)

The effect of using the post-tensioning technique along with the HPDC to enhance the flexural capacity and ductility of beams?

-

(5)

Determine the hybrid effect of CFRP sheets and post-tensioning technique in improving the flexural strength of the HPDC beam with a low reinforcement ratio.

To attain the primary aims, comprehensive experimental tests were performed in the present study containing ten large-scale HPDC beams with a very low reinforcement ratio of \(\:{\rho\:}_{s}\)=0.32%, which is significantly lower than the minimum value recommended by ACI 318. Various strengthening methods were applied to check the flexural capacity along with the failure pattern of HPDC beams, including single-layer CFRP, two-layer CFRP, and U-shaped CFRP strips. (for strengthening the bond performance between the CFRP and the concrete), a combination of CFRP strengthening methods and a hybrid CFRP/post-tensioning technique. Only U-shaped CFRP wrapping was taken into account for the HPDC beam, utilizing two-layer CFRP specimens to secure the extra CFRP layers and prevent debonding. In contrast, the one-layer system was deliberately simplified to examine its independent performance. Cracking patterns, crack width, number of cracks, and the debonding phenomenon were checked for all tested beams.

Experimental program

Materials & mixtures

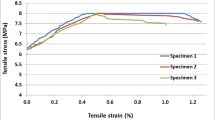

Ordinary Portland cement, ground granulated blast-furnace slag (GGBFS), and silica fume (SF) were used as binders for the HPDC mixture. The chemical composition of the powders used is mentioned in Table 2. The HPDC mixture has a water-to-binder (w/b) ratio of 0.19, a sand-to-binder (s/b) ratio of 0.50, and 2.0% micro steel fibers by volume of the mixture (Table 3). The straight steel fibers used had a length of 16 mm, an aspect ratio of 64, a tensile strength of 2720 MPa, and a modulus of elasticity of 210 GPa. Fiber was incorporated to enhance the tensile performance of the mixture; however, this addition posed a challenge by diminishing the mixture’s workability. A polycarboxylate superplasticizer (SP) was systematically added to all formulations to counteract this issue. This superplasticizer aims to ensure optimal fluidity, maintain viscosity, and promote effective dispersion of the fibers throughout the mix. The mixing process began with carefully combining silica sand, cement, and all other cementitious materials placed into the mixer. These components were blended for about five minutes, allowing the dry ingredients to achieve a uniform consistency. Following this, water and the superplasticizer were introduced into the mix, and the mixing was continued for an additional five to ten minutes, ensuring that the mixture developed a workable texture. To avoid any clumping of the fibers, they were gradually added during this blending phase. After the fibers were incorporated, mixing was sustained for another five minutes, guaranteeing a thoroughly mixed and homogenous combination, ready for further application. Regarding strengthening methods, two different materials of CFRP sheets and post-tensioning tendons were used in the experimental program. CFRP sheets had a thickness of 0.168 mm, a tensile strength of 4950 MPa, an elasticity modulus of 235 GPa, a break elongation of 1.9%, a fiber direction of 0° unidirectional, and a density of 1.80 g/cm3. Tendons used for the post-tensioning approach had a nominal diameter of 12.7 mm, a yield strength of 1531 MPa, an ultimate strength of 1927 MPa, and an elongation of 3.25%. As shown in the stress-strain curves of 8 mm reinforcement depicted in Fig. 1, longitudinal and stirrups had a yield strength of fy=386.3 MPa, an ultimate strength of fu=572.1 MPa, and an ultimate strain of 0.20.

Specimen preparation & test set-ups

Mechanical tests for concrete characterization

As shown in Fig. 2, different mechanical tests were conducted to characterize the HPDC mixture. For determining the stress-strain curve of the HPDC mixture, 150 × 300 mm cylinder samples were prepared (Fig. 2a). A splitting tensile test was also performed (Fig. 2b) based on the ASTM C49617. In the uniaxial tensile test context, dog-bone-shaped specimens were meticulously prepared, as depicted in Fig. 2c. After a curing period of 24 h, all specimens were carefully demolded and then immersed in water for an extensive curing period before undergoing testing. Following the guidelines provided by the Japan Society of Civil Engineers (JSCE)18, the specimens were designed with a thickness ranging between 13 and 30 mm, which adheres to the recommended dimensions for dog-bone-shaped tensile test samples. Accordingly, the thickness of the specimen was carefully established at 30 mm. To accurately measure the elongation occurring along the gauge length of the specimen, two linear variable differential transformers (LVDTs) with an impressive maximum capacity of 50 mm were employed. Concrete was meticulously poured into the mold to ensure optimal results, allowing the material to flow evenly from one side to the other. This approach facilitated a uniform distribution of steel fibers in a single direction. To enhance the precision of the measurements, the specimen was oriented vertically, and the testing apparatus was ingeniously designed with pin-fixed ends. This feature effectively eliminated secondary flexural stresses, guaranteeing that the loading remained centric during the test.

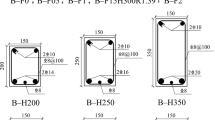

Large-scale specimen details

As shown in Fig. 3, ten large-scale HPDC beams have a constant geometry, reinforcement ratio, and HPDC mixture but varying strengthening methods. Large-scale HPDC beams were designed to prevent shear failure, following the guidelines provided by the JSCE18, to study their flexural capacity. For the shear reinforcement, 8 mm stirrups were used with a spacing of 100 mm, and to keep the shear reinforcements (stirrups) vertically in the shear zone, a very low longitudinal reinforcement ratio of =0.32% is considered, consisting of four 8 mm diameter reinforcing bars. The overall length of 2400 mm and section of 150 × 250 mm2 were considered for HPDC beams, which had a height-to-width ratio of around 1.67. The beam dimension (150 × 250) mm2 satisfies the minimum beam depth according to the (ACI 318) requirements for a simply supported beam. The identification of beam specimens is mentioned in Table 4. Along with reference HPDC beam “B1”, nine other beams were strengthened with various techniques, including (1) only CFRP sheets used for beams “B2-B4” with different CFRP layers and geometries. (B2- B4) configurations were designed per ACI 440.2R, targeting 50–100% flexural capacity increases while assessing debonding risks; (2) only post-tensioning method considering various 60% and 80% tendons considered for beams “B5-B6”; (3) hybrid CFRP sheets/post-tensioning technique for beams “B7-B10”. Combinations (B7- B10) explore synergistic effects, leveraging CFRP’s tensile strength and post-tensioning’s compressive prestressed.

CFRP strengthening preparation

As recommended by literature19,20,21, a specified procedure was followed to prepare CFRP strengthening of the HPDC beam, which is shown in Fig. 4. The process of preparing the HPDC beams for the application of CFRP sheets began with careful alignment and strategic marking of designated attachment locations on the surface of each beam. This meticulous planning was crucial to ensure that the CFRP sheets were positioned precisely, adhering strictly to the detailed specifications outlined in the experimental design. The first step involved polishing the marked areas to facilitate a robust adhesion between the CFRP sheets and the concrete. The concrete surface was meticulously smoothed using a grinder to achieve a uniform texture, which is crucial for effective bonding. Once polished, the surfaces were thoroughly cleaned to eliminate any dust and debris that could hinder the adhesive’s performance. To ensure optimal conditions, an air compressor was utilized to dry the surfaces completely, as even a hint of moisture could compromise the integrity of the adhesive bond. With the concrete surfaces prepared, the next task was to cut the CFRP sheets to precise dimensions that corresponded to the experimental design requirements. This step was crucial, as each sheet needed to match the specific size and shape dictated by the strengthening needs of the respective beam. The preparation of the epoxy adhesive followed, whereby it was carefully weighed and mixed according to the manufacturer’s precise ratio instructions. The mixing process was pivotal; achieving the right consistency was vital for obtaining the desired bonding strength. The adhesive was blended thoroughly to eliminate any potential inconsistencies that could weaken the bond. An even layer of the mixed epoxy adhesive was then applied to the prepared concrete surface, acting as the critical bonding interface between the concrete and the CFRP sheet. With care, each cut CFRP sheet was positioned onto this adhesive-coated surface, aligning it according to the established design specifications. The application was executed with precision, starting from one end of the sheet and progressing to the other, ensuring that it lay flat against the concrete. To achieve a strong and uniform bond, a leveling tool was utilized to apply firm pressure to the sheets, effectively squeezing out any air pockets and ensuring full contact with the concrete surface. A secondary layer of epoxy adhesive was subsequently applied over each CFRP sheet, penetrating and thoroughly impregnating the fabric, thereby reinforcing the bond and promoting structural integration with the concrete. In the final stages of the application process, any air bubbles trapped beneath the surface were eliminated by gently pressing down or using a roller, resulting in a flat and smooth finish. These application and impregnation steps were meticulously repeated for beams requiring multiple CFRP layers, such as beams B3, B7, B8, B9, and B10. Each layer was allowed to bond fully, with careful inspections conducted to ensure the absence of air pockets before proceeding to the next layer, thereby ensuring the overall effectiveness of the strengthening intervention.

Post-tensioning strengthening preparation

As illustrated in Fig. 5, specific steps were followed for the post-tensioning technique based on the literature22. In this study, one unbonded tendon was used for each beam. To simulate the in-service strengthening of concrete flexural members, a post-tensioning technique was employed. The pre-stressing was intentionally applied 28 days after casting to ensure the HPDC had fully matured, achieving its design compressive strength and minimizing the influence of time-dependent creep and shrinkage on pre-stress losses. Prior to application, the tendon cables were tested to determine their actual yield capacity (\(\:{f}_{py}\)). Steel anchor plates and end blocks were then installed at each end of the beam, precisely aligned to ensure an even distribution of the post-tensioning force. The tendons were positioned along the bottom face of the beam, approximately at one-third of the section’s height, corresponding to the region of maximum tensile stress. A calibrated hydraulic jack was used to apply the pre-stressing force in a controlled, incremental manner. The target stress levels in the tendons were set at 60% and 80% of their measured yield capacity. The selection of these levels is justified by common industry practice; for instance, ACI 318 − 19 permits initial tendon stresses up to \(\:0.70{f}_{pu}\) (approximately \(\:0.90{f}_{py}\)), making the \(\:0.80{f}_{py}\) level a high but permissible value to investigate maximum serviceability benefits. The \(\:0.60{f}_{py}\) level represents a more moderate, widely applicable stress level, allowing for a direct comparison of the efficiency of different prestressing intensities. After reaching the target force, the tendons were secured with nuts, and the beam was inspected for any signs of cracking or distress. This detailed procedure ensures the experiment is fully repeatable.

Flexural test

As shown in Fig. 6, to accurately monitor the deflection of the HPDC beam, linear variable differential transformers (LVDTs) were employed as displacement sensors. These sensors offer a high measurement precision of 0.01 mm, making them ideal for assessing crack widths. One LVDT was strategically placed at the mid-span of the beam to capture its central deflection, while the other two sensors were installed at the supporting positions to monitor the beam’s behavior under load at its critical supports. This configuration allows for a comprehensive analysis of the beam’s structural integrity and potential failure points. Regarding the large-scale flexural test, the rate of the universal machine was around 0.1 mm/min.

Analyzing approach

As schematically illustrated in Fig. 7, various parameters were extracted from the experimental load-displacement curve to compare the mechanical and ductility characteristics. The initial stiffness of the HPDC beam was measured using the slope of a line connected until the displacement corresponded to 70% of the maximum force 0.70. The ductility index was calculated using the ratio of /, where and correspond to the initial and final displacement linked to 85% of the maximum force \(\:{0.85F}_{max}\). To check the performance of HPDC beams tested in the present study, various flexural capacity models proposed by standards18,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30 were employed in the present study, which is summarized in Table 5 in four categories of bare beam with no strengthening method, single-layer CFRP strengthening, multi-layers CFRP strengthening, and post-tensioning. As outlined in Table 5, most existing models for fiber-reinforced concrete members provide a model for predicting the flexural strength considering the contribution of both the matrix and the fibers to the flexural capacity.

Experimental results

Characterization of HPDC

Following 28 days of water curing, the compressive stress-strain curves for the HPDC cylindrical specimens measuring 150 × 300 mm are displayed in Fig. 8. After three repetitions, compressive strengths at 28 days were 65.6, 64.7, and 55.2 MPa obtained from the cylindrical specimens. Based on the initial stiffness of the elastic region of curves, the elastic modulus of 25.11, 21.88, and 24.00 GPa were obtained for HPDC specimens. The literature obtained a similar compressive strength range for HPC with no coarse aggregate content31,32,33. Uniaxial stress-strain curves of HPDC mixtures at 28 days are shown in Fig. 9a. Direct tensile strengths of 7.94, 8.15, and 8.24 MPa were found, corresponding to the tensile capacity of 0.3–0.6%. The uniaxial tensile-to-uniaxial compressive strength ratio is around 0.12–0.13 for the HPDC mixture tested in the present study. The splitting tensile results for HPDC mixtures were 10.88, 9.0, and 10.50 MPa. This shows that the splitting tensile-to-uniaxial compressive strength ratio ranges from 0.14 to 0.17. A comparison between the strain capacity of the property HPDC mixture and the mixture presented in the previous investigation, which has a volume fraction of steel fibers of around 2.0%, is shown in Fig. 9b. The analysis shows that in the field of DHPC mixture, the present HPDC mixture performs appropriately.

Flexural capacity of HPDC beams

Moistened burlap (hessian) was applied for the curing process of the large-scale beams over a period of 28 days. Following this period, the samples were kept in the laboratory for testing until they reached 90 days. Bending tests were performed after the 90-day. A summary of results for HPDC beams after the flexural test is mentioned in Table 6, including first cracking load (\(\:{P}_{cr}\)), ultimate load (\(\:{P}_{u}\)), debonding load (\(\:{P}_{de}\)), maximum deflection (\(\:{U}_{m}\)), initial stiffness (\(\:\theta\:\)), ductility ratio, absorbed energy, and failure type. Generally, two different failure modes were observed for HPDC beams, including “flexural” and “flexural + debonding”. The load-displacement curve for the reference HPDC beam, illustrated in Fig. 10, demonstrates the strain-hardening phenomenon due to fiber bridging, and this phenomenon cannot be attributed to the steel reinforcement, as it is about half the minimum steel reinforcement. Initially, the beam exhibits an impressive flexural capacity of approximately 10.96 kN.m. As the load grows and approaches its peak, rather than experiencing an instant collapse, the beam permits a gradual transfer of force, even while the bending at the bottom intensifies markedly. This behavior signals the activation of the internal micro steel fibers embedded within the concrete. These micro steel fibers play a crucial role in enhancing the beam’s performance. They act as reinforcements that bridge the cracks developing in the concrete during loading, effectively redistributing the stresses more uniformly across the structure. This bridging action is vital as it helps maintain a robust load capacity, contributing to the extended plateau observed after the peak load is reached. Even when the concrete matrix begins to crack, the fibers continue to support the load, which slows the reduction in load capacity, ultimately enhancing the overall ductility and toughness of the beam. Additionally, the micro steel fibers are essential in managing the formation and spread of cracks, which is particularly important during the strain-hardening phase. This resilience is crucial for the beam’s performance under cyclic or prolonged loading scenarios. Furthermore, this mechanism facilitates improved load redistribution, meaning that the presence of steel fibers enables the beam to tolerate localized failures without experiencing an abrupt and catastrophic decline in its load-bearing capabilities, especially in the critical post-peak phase. As mentioned in Table 6, although the experimental results of the “B1” beam confirm the ductility behavior, some concerns still exist regarding the flexural capacity of the reference HPDC beam with a very low reinforcement ratio. Accordingly, the following subsections separately examine the effects of using strengthening techniques to improve the flexural capacity and determine how much these techniques can have side effects on beams’ ductility behavior.

Influence of CFRP strengthening

The effect of CFRP strengthening methods bonded to the tension face of HPDC beams on the flexural behavior compared to the reference beam is illustrated in Fig. 10. The stress distribution along with the length of bonded CFRP laminate increased at the ends of the beam (ACI 440.2R-17), which caused CFRP delamination, so using U-shaped wraps around the beam reduces peeling or debonding risks compared to flat CFRP sheets. Moreover, using U-shaped CFRP improves shear strengthening, crack control, and beam ductility These techniques include a single layer of CFRP sheet, two layers of CFRP sheets, and a combination of “two-layer sheets + U-shaped wraps.” As mentioned in Table 6, debonding failure was also observed in these CFRP-strengthened HPDC beams compared to the only flexural failure of the reference beam. Accordingly, the debonding load (\(\:{P}_{de}\)) was also defined for them. The addition of a single-layer CFRP sheet changed the load-displacement curve of the HPDC beam, which improved the maximum loading capacity of the beam but simultaneously reduced the maximum displacement or strain-hardening plateau length. Additionally, the initial stiffness of HPDC beams was enhanced by using a single-layer CFRP sheet. As mentioned in Table 6, using a single-layer CFRP sheet resulted in 55.1% and 88.0% improvements in the first cracking load and maximum load, respectively. However, a -48.1% reduction was observed for the maximum displacement of the HPDC beam. The ductility ratio was reduced due to the use of a single-layer CFRP sheet. This could be attributed to the high stiffness and limited elongation capacity of the CFRP. The load transfers between the CFRP and the HPDC beam, along with stress concentration at the interfacial zone, alter the main strain-hardening behavior of the HPDC mixtures, leading to restricted elongation before rupture. The CFRP reached its tensile capacity just as the beam reached its maximum load, resulting in a sudden rupture. Additionally, the use of CFRP for strengthening decreased the potential for plastic hinge formation. As indicated in Table 6, the mode of failure changed from purely flexural to debonding. In this case, the CFRP sheet did not fail by rupture; instead, it debonded from the concrete surface under higher loads. Debonding typically occurs suddenly and in a brittle manner, which reduces both the load-carrying capacity and ductility of the structure. In this scenario, the interfacial strength between the CFRP and concrete is subjected to high shear and tensile stresses. If the bond strength between the CFRP and concrete is inadequate to transfer these forces effectively, debonding will occur.

Figure 10 shows the result of the multi-layer CFRP-strengthened beam. Compared to the single-layer CFRP one, using two layers not only improved the ultimate flexural load but also observed a sudden drop in the load-carrying capacity of the beam (due to the debonding of the CFRP laminates), followed by a strain-hardening domain with very low flexural load. As mentioned in Table 6, a similar failure mode was observed compared to the single-layer, while a very high debonding load was recorded for the multi-layer CFRP. This increase might be attributed to the better stress distribution across several CFRP layers, which delays interfacial debonding. Additionally, possible interlayer delamination between CFRP plies can be another reason for this observation, which helps redistribute stresses and extends load capacity. Furthermore, enhanced composite action owing to the thicker CFRP system can be another reason. Based on experimental results, using multi-layer CFRP resulted in enhancements of 25.7% and 39.0% in maximum load and debonding load, respectively, while no considerable difference was observed for cracking load (approximately 4.8%) and initial beam stiffness (4.6%). A sudden drop in the load-carrying capacity of the HPDC beam strengthened with multi-layer CFRP made it challenging to consider the post-peak strain-hardening phenomenon observed in this beam. Based on the ductility ratio, multi-layer CFRP generated 51.4% and 21.9% reductions compared to the reference HPDC beam and single-layer CFRP one, respectively. A supplementary U-shaped CFRP wrapping was used for the HPDC beam containing a two-layer CFRP, denoted as a “B4” beam. Results show that the synergic effect of “two-layer CFRP + U-shaped wrapping” significantly enhanced the flexural capacity and alleviated the load-carrying drop issue observed for “B3” before. As mentioned in Table 6, 17.5%, 18.4%, and 43.1% developments were observed for ultimate load, debonding load, and initial beam stiffness, respectively as compared with two-layer CFRP ones, while no improvement was observed for the first cracking load (Fig. 10). Also, the combination CFRP method could not change the failure mode. The observed disappearance of the large debonding zone in Beam 4 (with U-shaped CFRP wrapping) as compared to Beam 3 (with only two-layer CFRP sheets) can be due to the improved confinement. The U-shaped CFRP wrapping offers supplementary confinement, enhancing the bond between the CFRP sheets and the concrete substrate. This confinement reduces stress concentrations at the ends of the CFRP sheets, thus diminishing the risk of debonding. Additionally, synergistic application of U-shaped wrapping and CFRP sheets permits for better redistribution of stresses along the beam. This alleviates localized stress peaks that typically lead to debonding in beams with only CFRP sheets.

Influence of post-tensioning

Figure 11 shows the effect of the post-tensioning technique on the load-displacement curve of the HPDC beam. Generally, experimental observation showed that 60% and 80% post-tensioning techniques considerably enhanced the flexural capacity of HPDC beams, so that first cracking loads improved by 76.2% and 111.7% for 60% and 80% post-tensioning, respectively. As summarized in Table 6, the ultimate flexural load was improved by around 156.9% and 203.5% for 60% and 80% post-tensioning, respectively. An improvement in initial stiffness was also obtained for post-tensioned HPDC beams by 89.1% and 122.7% for 60% and 80% post-tensioning, respectively. Compared to the CFRP strengthening results shown in Fig. 10, it can be deduced from Fig. 11 that HPDC beams strengthened with post-tensioning have a considerably notable strain-hardening capacity. This observation was confirmed by comparing the ductility ratio, where comparable and slightly higher (16.3%) enhancement was found for the post-tensioning technique. As mentioned in Table 6, the “flexural” failure mode was observed for the HPDC beam containing post-tensioned tendons. Regarding post-tensioned tendons-contained HPDC beams, an initial compressive force is applied to the concrete. This compression counteracts the tensile stresses that develop in the beam under loading. By reducing the tensile stress required to initiate cracking in the concrete, the beam achieves greater initial stiffness. As a result, the concrete remains in compression for a longer period during loading, which delays cracking and helps maintain stiffness over an extended range of loads. Moreover, the post-tensioned tendons provide an additional compressive force, which enhances the overall moment-resisting capacity of the beam. In this case, the transition from the elastic phase to plastic deformation is delayed, and a strain-hardening effect occurs. The tendons contribute to a prolonged plastic phase, resulting in a strain-hardening plateau, as they take on extra stress when the concrete section softens.

The effect of a hybrid using two-layer CFRP sheets and post-tensioning on the flexural capacity of the HPDC beam is shown in Fig. 12. Compared to bare HPDC beams, using this hybrid strengthening system caused 83.4% and 98.5% improvements in the first cracking load of 60% and 80% post-tensioning, respectively. As summarized in Table 6, regarding maximum flexural load, using this hybrid technique resulted in 288.0% and 256.9% enhancements in 60% and 80% post-tensioning, respectively, showing that even 60% is enough, as no difference was observed for both 60% and 80% post-tensioning percentages. Although the “debonding” failure mode was observed for this hybrid system, which contained 60% post-tensioning, the “flexural” failure was dominant at 80%. Moreover, the load-displacement curve of this hybrid system shows that using CFRP sheets caused sudden loading drops for both post-tensioning percentages, which can be due to the local debonding of CFRP after reaching its tensile capacity (Fig. 12). This mechanism changes the appropriate strain-hardening mechanism of HPDC strengthened with only the post-tensioning technique (Fig. 11). As mentioned in Table 6, the debonding load of a hybrid system containing. Comparing Figs. 10, 11 and 12 shows that this hybrid system had higher flexural load improvement (51.02–64.2%) compared to only two-layer CFRP and only 60% post-tensioning, respectively. This improvement range is around 17.6-51.08% for a hybrid system containing 80% post-tensioning. However, the hybrid system causes a significant reduction in HPDC beam ductility. For instance, 60% post-tensioned hybrid system had 50.8% and 15.1% reductions in ductility compared to only 60% post-tensioning and only two-layers CFRP, respectively. A similar trend was observed for the 80% post-tensioned hybrid system (Table 6).

Another type of hybrid system, containing “two-layer CFRP + U-shaped CFRP wrapping + post-tensioning,” was considered in the present study, as depicted in Fig. 13. Local CFRP debonding caused a sudden drop in the load-displacement curves, resulting in a limited ductility ratio. Similar to the first hybrid system (Fig. 12), this system also showed that using a changing post-tensioning percentage has no considerable impact on the flexural capacity of the “two-layers CFRP + U-shaped CFRP wrapping + post-tensioning” system (Fig. 13). This observation is different from the results illustrated in Fig. 11 for only the post-tensioning strengthening method, where changing post-tensioning percentage resulted in a notable improvement on the flexural load of the HPDC beam. As mentioned in Table 6, using 60% post-tensioning in this hybrid system resulted in a “flexural” failure mode, while debonding was also dominant at 80%. The general deboning phenomenon observed in strengthened-HPDC beams is illustrated in Fig. 14. The observations depicted in Fig. 13 highlight notable sudden drops and discontinuities in strain hardening within this hybrid system, which may indicate localized failures or instabilities in the reinforced HPDC beam. Such sudden load drops are frequently linked to debonding issues. As the applied load increases, stress concentrations can develop at specific points within the bond that adheres the CFRP to the concrete, leading to partial debonding. This phenomenon results in a temporary decrease in stiffness, visible as a sharp drop in the load-displacement curve. In the context of the two-layer CFRP configuration, it is essential to consider that the bond between the CFRP layers themselves or between the CFRP and the concrete may harbor localized weaknesses that contribute to this observed behavior. Furthermore, the presence of micro-cracking at the interface where the concrete meets the CFRP—driven by the high strain demands and varying stiffness characteristics of the two materials—might serve as an additional explanation for these sudden load drops. To counteract these issues, U-shaped CFRP strips are commonly employed. These strips anchor the sheets securely, thereby enhancing the bond performance between the CFRP and the concrete. However, debonding can still occur if the bond strength or anchorage fails to meet the required standards under a substantial load, which is clearly observed in Fig. 13. A comparison of Figs. 12 and 13 reveal that the U-shaped CFRP strips have effectively mitigated the sudden drops or the aforementioned debonding phenomenon. Moreover, in addition to the CFRP/concrete debonding, it is crucial to entertain the possibility of differential slip or debonding between the CFRP layers, as this can also lead to abrupt changes in the overall structural stiffness. Another critical observation is that although the ductility ratio is still the primary concern of these hybrid-strengthened HPDC beams, significant improvements were observed in flexural capacity even with this very low reinforcement ratio. In this case, the hybrid system with 60% post-tensioning had 138.2%, 412.2%, and 89.7% improvements on the first cracking load, maximum flexural load, and initial stiffness of the HPDC beam, respectively (Table 6). For the hybrid system with 80% post-tensioning, flexural enhancements were in the range of 93.6-386.3% compared to the reference HPDC beam. However, 69.6% and 65.3% reductions were observed for the ductility ratio of hybrid systems, containing 60% and 80% post-tensioning, respectively. Comparing flexural parameters of “B7” and “B9” beams shows that using additional U-shaped CFRP strips to the hybrid strengthening system with 60% post-tensioning resulted in 29.9% and 32.0% higher first cracking load and ultimate flexural load, respectively (Fig. 13). Similarly, U-shaped CFRP strips had promising influence on structural performance of the hybrid strengthening system with 80% post-tensioning, where 25.3–36.3% flexural developments were observed. However, U-shaped CFRP strips could not have a positive impact on the ductility ratio, so 21.9% to 26.3% reductions were found. Comparing results depicted in Figs. 12 and 13 shows an unexpected trend where HPDC beam with 60% post-tensioning + two CFRP layers had a slightly higher flexural capacity than the beam with 80% + two CFRP layers, despite the experimental results presented in Fig. 11 showing the opposite trend in HPDC beams without CFRP. This observation can be assigned to some interacting parameters. It may be due to an internal change in failure mode and load-sharing behavior of HPDC beams after utilizing CFRP sheets, since CFRP causes cracking restrictions and shifts the failure mode toward CFRP rupture or debonding rather than concrete crushing. The findings may also be due to the changing role of post-tensioning in the presence of CFRP sheets, so that higher post-tensioning (80%) might result in premature concrete compression failure before the CFRP capacity, whereas 60% post-tensioning permits better operation of the CFRP. Moreover, 80% of post-tensioning beams might have approached an over-reinforced state, where unnecessary post-tensioning force shifts the neutral axis too high, resulting in brittle concrete crushing before the CFRP fully initiates. However, 60% post-tensioning beam strikes a well stability, allowing the CFRP to contribute more before failure.

In this study, Digital Image Correlation (DIC) analysis was utilized instead of conventional strain gauges to monitor strain concentrations in reinforced concrete beams subjected to flexural loading. This choice of method was influenced by DIC’s ability to provide full-field, non-contact measurement of surface deformation, rather than relying on discrete, point-specific data from strain gauges. DIC method provides a complete strain map, enabling the accurate identification and quantification of strain concentrations at sites where cracks initiate and throughout the failure process. The results of DIC analysis are shown in Fig. 15. Regarding CFRP strengthening methods, the observation showed that strain concentration in B3 is higher than B2 beam, which are illustrated in Fig. 15a,b. The enhanced strain concentrations identified in the DIC maps for the beam featuring two CFRP layers, in contrast to the one with a single layer, are a direct consequence of the beam’s augmented load capacity and stiffness. A normalized comparison between all strengthened HPDC beams was performed and presented in Fig. 16, compared to the reference HPDC beam “B1”. The addition of the second layer lowers the beam’s neutral axis further, which positions the outermost CFRP fibers at a greater distance from it. This geometric alteration, along with the CFRP’s exceptional load-bearing capability, results in the two-layer laminate encountering higher local strain for the same applied load. As a result, at flexural cracks where stress becomes more intense, the DIC system detects these increased strain concentrations, illustrating that the extra layer plays a more significant role in counteracting the tensile forces, thus providing a more effective strengthening impact despite the higher localized strain values. Moreoever, as shown in Fig. 15c,d, there was probably no significant difference in strain concentration between the beams post-tensioned to 60% and 80%. The lack of a notable difference in strain concentration for the 60% and 80% post-tensioned beams can be explained by the primary influence of pre-compression on crack behavior. Post-tensioning generates a compressive stress that must be overcome before the concrete can experience tension and subsequently crack. Although the 80% beam had a greater initial pre-compression, both levels were likely adequate to prevent the development of numerous fine cracks under the service load levels you examined. Since the strain concentrations you recorded are mainly localized peaks at specific crack sites, the comparable crack pattern (in terms of quantity and width) in both beams would lead to similar strain concentration values. The increased post-tensioning force mainly improved load-carrying capacity and stiffness, delaying cracking rather than altering the fundamental mechanism of strain localization at the cracks that did form, which is precisely what the DIC method captures. However, as depicted in Fig. 15e,f, for hybrid strengthening beams, the DIC observation showed that “two CFRP + 60% post-tensioning” had higher numbers of strain concentration locations as compared to the HPDC beam with “two CFRP + 80% post-tensioning”, despite their comparable ductility and energy absorption (Fig. 16). This may be due to a fundamental distinction in how damage progresses and cracks are distributed. The reduced post-tensioning force in the 60% HPDC beam leads to a lower initial compressive stress field. As loading occurs, this facilitates a larger number of finer cracks to form and spread strain more evenly across the tension face before a few dominant cracks localize the failure. The DIC maps reveal this distributed micro-cracking through an increased number of strain concentrations. Conversely, the elevated 80% post-tensioning force results in a more robust “locking in” of compression, which more effectively reduces widespread cracking; however, once the higher pre-compression is surpassed, it causes strain to be concentrated intensely at fewer, more critical crack locations. The fact that both HPDC beams demonstrated similar overall performance (ductility and energy) suggests that the 60% beam reached its capacity via a more distributed, finely cracked mechanism, while the 80% beam attained the same outcome through a method characterized by fewer, but more severe, localized cracks. Additionally, the general normalized comparison analysis presented in Fig. 16 showed that the hybrid strengthening system applied to HPDC beams “B7-B10” caused the highest ultimate load, absorbed energy, and first cracking load. However, HPDC beams “B6” and “B8” had the highest initial stiffness among other HPDC beams, showing that using the higher post-tensioning technique (80%) can affect the initial stiffness. Regarding ductility ratio, the highest value belongs to the “B6”, where only 80% of the post-tensioning technique was applied.

Discussion of observations

Failure patterns of HPDC beams are shown in Fig. 17. Generally, it is clearly depicted that various strengthening techniques can affect the crack width, number of cracks, and failure pattern. Cracking results observed in Fig. 17 were precisely extracted and analyzed to compare the results illustrated in Fig. 18. Experimental observations revealed that although using strengthening techniques causes a slight reduction in the number of cracks at the first crack load, it considerably increased the number of cracks at the ultimate and failure loads (Fig. 18a). The highest number of cracks was observed in the “B7” and “B8” beams, where two CFRP layers and post-tensioning tendons were used and bonded at the HPDC tensile zone. It is worth mentioning that, as Fig. 17, almost no large crack widths were observed for HPDC beams of “B7-B10”, despite the disappointing observation of the reference beam “B1”. The crack width measurements of beams at different stages of loading are illustrated in Fig. 18b, where it is clearly demonstrated that using strengthening methods, especially “B7-B10”, can solve the high-risk condition of the reference HPDC beam with a very low reinforcement ratio.

To precisely study the effectiveness of using such strengthened HPDC beams, a comparison between the present study results and an NC beam with structural concrete strength (25 MPa) was also performed in the present study, summarized in Table 7. Based on the analysis, the reinforcement percentage of the NC beam should be improved by the range of 50.53% to 853.40% to have a comparable flexural capacity. Simply put, the number of 8 mm longitudinal reinforcement should be increased by a range of 3 bars for the flexural capacity comparable with the reference HPDC beams, to 21 bars to achieve a similar flexural capacity of “B9” beams. Accordingly, the proposed strengthened HPDC beams contain a very low reinforcement ratio of 0.32 and were able to show much more bending behavior than the same beam with NC. Still, the amount of reinforcement is much higher. As shown in Fig. 19, to have a comparable flexural capacity obtained in the present experimental study, an NC beam should have 0.45% reinforcement for “B1” to 3.14% for “B9”, showing a high percentage of the reinforcement ratio required. However, the proposed structure in the present study could reach this high-level flexural capacity with a very low reinforcement ratio. This promising result indicates that an HPDC mixture can be utilized as a structural element, provided that specific considerations outlined in concrete design codes are followed to control the ductility ratio. This study demonstrates that HPDC beams with a 0.32% reinforcement ratio achieve flexural capacities 24–412% above ACI 318 − 19 predictions, leveraging fibers and strengthening to rival NC beams with 0.45–3.14% reinforcement (Table 7).

As summarized in Table 5, various flexural models are included in design codes to predict the flexural capacity of HPDC beams. The performance of these models in predicting the flexural capacity of HPDC beams was examined in the present section. As shown in Fig. 20a, the comparative analysis of the various models reveals that the model of RILEM TC 162-TDF (2003) precisely predicts the flexural capacity of HPDC beam with almost no deviation, followed by fib Model Code (2010) with 4.5% deviation and JSCE-SF4 (2002) model with 10.9% deviation. As mentioned in Table 5, empirical factors based on fiber orientation and fiber bond strength (\(\:{\lambda\:}_{f}\)), fiber volume fraction (\(\:{V}_{f}\)), tensile strength of fibers (\(\:{f}_{f}\)), and the aspect ratio of fibers (\(\:{l}_{f}/{d}_{f}\)) are the primary parameters used in these predictive models. Regarding single-layer CFRP strengthening, Fig. 20b illustrates the performance of various models in predicting the flexural behavior of the “B2” beam. The comparison analysis indicates that most models within the codes overestimate the flexural capacity of this beam type, suggesting that a new model is required for HPDC beams with single-layer CFRP strengthening. A similar trend was observed for the two-layer CFRP-strengthened HPDC beam (B3), where the fib Bulletin 14 and ACI 440 models significantly overestimated the flexural capacity of beam B3 (Fig. 20c). The performance of the ACI 318R-1923 predictive model for post-tensioned HPDC beams (B5 & B6) at 60% and 80% is depicted in Fig. 20d. The results indicate that this ACI equation slightly overestimates the flexural performance of HPDC beams with post-tensioning tendons, with deviations of 8.16% and 13.5% observed for the 60% and 80% configurations, respectively. Consequently, there is a need to develop new equations within the design codes for HPDC beams. It is important to note that the proposed equations for these design codes were derived from an extensive experimental database. Therefore, further comprehensive experimental work is necessary in future studies to establish a new model for HPDC beams.

Conclusions

This study implemented a comprehensive experimental program to investigate HPDC beams’ flexural capacity with a very low reinforcement ratio. The research focused on evaluating these beams with and without applying various strengthening techniques. A total of ten large-scale HPDC beams were constructed, each subjected to different strengthening approaches, including single-layer CFRP, double-layer CFRP, U-shaped CFRP strips, and varying percentages of post-tensioning at 60% and 80%. Additionally, hybrid methods combining CFRP with post-tensioning were also employed. The study meticulously examined various flexural parameters derived from the load-displacement curves, which characterize the beams’ responses under loading. Furthermore, it investigated critical aspects, such as cracking patterns and modes of failure, which are essential in understanding the structural integrity and performance of the beams. Ultimately, based on the experimental findings, several vital observations were drawn, offering valuable insights into the effectiveness of the applied strengthening methods and their impact on the flexural capacity of HPDC beams, as follows:

-

Using HPDC, even with a very low reinforcement ratio, not only has no negative effect as a structural concrete on the behavior of RC beams, but compared to the current regulations and flexural models, it has shown very good structural behavior, which shows the high potential of this so that HPDC can be used as structural concrete. For example, the flexural strength of this concrete is 24.5% higher compared to ACI 318 − 19, 13.6% higher than the ACI 544.1R regulation, 30.9% higher than the JSCE (2007), and 4.5% higher than fib model code 2010.

-

Although the strain-hardening phenomenon observed in the HPDC beam caused a proper ductility ratio, the width of the crack at failure load (more than 10 mm) was the main concern of this beam with a low reinforcement ratio, which made it essential to use some strengthening techniques.

-

Using a single-layer CFRP sheet improved the beam’s maximum loading capacity but simultaneously reduced the maximum displacement or strain-hardening plateau length. In this case, 55.1% and 88% improvements were observed for the first cracking load and maximum load, respectively. However, the ductility ratio was reduced due to using a single-layer CFRP sheet.

-

Using two layers of CFRP instead of a single layer not only improved the ultimate flexural load but also resulted in a sudden drop in load-carrying capacity, followed by a strain-hardening phase characterized by very low flexural loads. Multi-layer CFRP exhibited high debonding loads. Furthermore, using multi-layer CFRP led to enhancements of 20.45% in maximum load and 39% in debonding load. In contrast, there was no significant difference in cracking load (approximately 4.8%) or initial beam stiffness (4.6%). The sudden drop in the load-carrying capacity of the HPDC beam strengthened with multi-layer CFRP made it challenging to analyze the post-peak strain-hardening phenomenon observed in this beam.

-

Considering 60% and 80% post-tensioning techniques dramatically improves the flexural strength of HPDC beams compared with the reference beam (B1). The loads at which these beams first crack increase by 76.2% with 60% post-tensioning and 111.7% with 80% post-tensioning. Regarding maximum load, the improvements are around 156.9% for 60% post-tensioning and 203.5% for 80% post-tensioning. The initial stiffness of post-tensioned HPDC beams also goes up. It improves by 89.1% with 60% post-tensioning and by 122.7% with 80% post-tensioning. Compared to CFRP strengthening methods, post-tensioning shows a much better ability to handle stress without breaking. These gains are confirmed by looking at the ductility ratio.

-

Using U-shaped CFRP strips could approximately control the local debonding effect of CFRP layers by reducing the load drops in load-displacement curves and enhancing the flexural capacity of HPDC beams. U-shaped CFRP strips anchor the sheets securely, strengthening the bond performance between the CFRP and the concrete.

-

The incorporation of hybrid-strengthened HPDC beams resulted in significant flexural capacity improvements with a low reinforcement ratio. Specifically, the hybrid system with 60% post-tensioning showed increases of 138.2% for the first cracking load, 412.2% for the maximum flexural load, and 89.7% for initial stiffness. HPDC Beams B7 and B9 exhibited the highest ultimate load, while beams B6 and B8 demonstrated superior initial stiffness due to the 80% post-tensioning technique. Beam B6 also had the highest ductility ratio among the group.

This study pioneers the systematic evaluation of HPDC beams with minimal reinforcement, offering a pathway to reduce steel usage and enhance sustainability in structural design. It is important to note that a moderate ductile HPDC mixture was chosen for this research, and therefore, further experimental studies are necessary to evaluate the possibilities of other generations of HPDC, including ultra-high ductile versions that incorporate different types of fibers, such as PVA and PE, to investigate whether these ductile cementitious composites can be utilized as structural concrete with or without reinforcement techniques. Also, using glass fiber reinforced polymer bars (GFRP) instead of steel rebar will eliminate future maintenance due to reinforcement corrosion. The concrete design standards should also include specific models for these ductile concrete elements. Moreover, to thoroughly assess the sustainability of the hybrid strengthening approach established in the present research, further studies should build on these structural insights with a life-cycle assessment (LCA). Conducting a comparative evaluation of embodied carbon between the HPDC system and conventional strengthening techniques is crucial for assessing their environmental impacts and confirming their benefits from a comprehensive, eco-friendly engineering perspective.

Data availability

Some or all data, models, or code that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- \(a\) :

-

Depth of the compression stress block

- \({a}_{f}\) :

-

CFRP-related stress block in the tension zone

- \({a}_{f.i}\) :

-

Stress block depth in the i-th CFRP layer

- \({A}_{ECC}\) :

-

Effective area of ECC

- \({A}_{f}\) :

-

Cross-sectional area of CFRP layers

- \({A}_{f.i}\) :

-

Area of the i-th layer of CFRP

- \({A}_{p}\) :

-

Cross-sectional area of post-tensioned tendons

- \(b\) :

-

Section width

- \({C}_{ECC}\) :

-

Strain in the ECC at the extreme fiber

- \(d\) :

-

Effective depth of beam

- \({d}_{f}\) :

-

Fiber diameter

- \({d}_{i}\) :

-

Distance of the compression fiber to the i-th CFRP layer

- DIC:

-

Digital image correlation

- \({E}_{f}\) :

-

Modulus of elasticity of CFRP

- \({e}_{p}\) :

-

Eccentricity of the post-tensioned tendons

- \({E}_{CFRP.i}\) :

-

Modulus of elasticity of the i-th CFRP layer

- \(\theta\) :

-

Initial stiffness of HPDC beams

- \({f}_{c. ECC}\) :

-

Compressive strength of ECC matrix

- \({f}_{t. ECC}\) :

-

Tensile strength of ECC matrix

- \({f}_{f}\) :

-

Tensile strength of fibers

- \({f}_{fe}\) :

-

Effective stress in CFRP at failure

- \({f}_{fd.i}\) :

-

Design stress of the i-th layer of CFRP

- \({f}_{fu}\) :

-

Ultimate tensile strength of CFRP

- \({f}_{p. effective}\) :

-

Effective stress in post-tensioned tendons

- \({f}_{py}\) :

-

Yielding tensile strength of the tendons

- \({f}_{pu}\) :

-

Ultimate tensile strength of the tendons

- \({h}_{f}\) :

-

The effective height of the CFRP layer

- \(k\) :

-

Interaction factor to consider ECC and CFRP

- \({l}_{f}\) :

-

Fiber length

- \({\lambda }_{f}\) :

-

Empirical factor based on fiber orientation and fiber bond strength

- \({M}_{0}\) :

-

Flexural capacity of plain concrete

- \({M}_{f}\) :

-

Flexural capacity of fiber-reinforced concrete

- \({M}_{n}\) :

-

Flexural capacity of strengthened beams

- \({M}_{PT}\) :

-

Contribution of post-tensioning in flexural strength

- \(n\) :

-

Number of CFRP layers

- NC:

-

Normal concrete

- \({P}_{cr}\) :

-

First cracking load

- \({P}_{u}\) :

-

Ultimate laod

- \({P}_{de}\) :

-

Debonding laod

- \({t}_{CFRP}\) :

-

Thickness of a single CFRP layer

- \({U}_{m}\) :

-

Maximum deflection

- \({V}_{f}\) :

-

Fiber volume fraction

- \({\tau }_{f}\) :

-

Bond strength between fibers and matrix

- \({\sigma }_{b}\) :

-

Bridging stress provided by fibers

- \({l}_{f}/{d}_{f}\) :

-

Aspect ratio of fibers

- \({\varepsilon }_{f}\) :

-

Effective strain in CFRP at failure

- \({\varepsilon }_{fd}\) :

-

Debonding strain

- \({\epsilon }_{CFRP}\) :

-

Effective strain in CFRP layers

- \({\epsilon }_{ECC}\) :

-

Strain in the ECC at the extreme compression fiber

- \(\zeta\) :

-

Crack-bridging factor for ECC

- \(\eta\) :

-

Coefficient regarding % of post-tensioning

References

Voo, Y. l. and S.J. Foster. Characteristics of ultra-high performance ‘ductile’concrete and its impact on sustainable construction. IES J. Part A Civil Struct.Eng. 3 (3), 168–187. (2010).

Lavanaya Prabha, S. et al. Study on structural behaviour of ductile High-Performance concrete under impact and penetration loads. J. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 23 (6), 2380–2388 (2022).

Nematollahi, B. et al. A review on ultra high performance ‘ductile’concrete (uhpdc) technology. Int. J. Civil Struct. Eng. 2 (3), 1003–1018 (2012).

Dong, F. et al. in-plane shear behavior of masonry panels strengthened with ultra-high ductile concrete (uhdc). Eng. Struct. 252, p113609 (2022).

Liao et al. Experimental study of reinforced uhdc-uhpc panels under close-in blast loading. J. Building Eng. 46, 103498 (2022).

Liao Q., X. Xie, and J. Yu, Numerical investigation on dynamic performance of reinforced ultra-high ductile concrete–ultra‐high performance concrete panel under explosion. Struct. Concrete 23 (6), 3601–3615. (2022).

Kumar. Investigation on the flexural behaviour of high-performance reinforced concrete beams using sandstone aggregates. Build. Environ. 42 (7), 2622–2629 (2007).

Zaki S.I., I.M. Metwally, and S.A. El-betar. Flexural behavior of reinforced high-performance concrete beams made with steel slag coarse aggregate. Int. Sch. Res. Notices 2011 (1), 374807. (2011).

Yun et al. Experimental research on the ductility of high performance concrete beams. Appl. Mech. Mater. 166, 1316–1320 (2012).

Yang C. Joh, and B.-S. Kim. Structural behavior of ultra high performance concrete beams subjected to bending. Eng. Struct. 32 (11), 3478–3487 (2010).

Said et al. Experimental and analytical investigation of high performance concrete beams reinforced with hybrid bars and Polyvinyl alcohol fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 259, 120395 (2020).

El-helou, R. G. and B. A. Graybeal. Flexural behavior And design of ultrahigh-performance concrete beams. J. Struct. Eng., 2022. 148 (4), 04022013. (2022).

Solhmirzaei R., H. Salehi, and V. Kodur. Predicting flexural capacity of ultrahigh-performance concrete beams: machine learning–based approach. J. Struct. Eng. 148 (5), 04022031. (2022).

Saqif M., Y.-S. Tai, and S. El-tawil. Experimental and computational evaluation of the ductility of uhpc beams with low steel-reinforcement ratios. J. Struct. Eng. 148 (7), 04022077. (2022).

saqif et al. strength, ductility, and collapse response of Uhpc waffle slabs. J. Struct. Eng. 149 (7), 04023090 (2023).

Hamad and M. Dehestani. Flexural strengthening of ductile high-performance concrete beam with low reinforcement ratio using glass fibre-reinforced polymer sheets. Proc. Inst. Civil Eng. Struct. Build., 178(10): pp. 970–990. (2025).

ASTM c496. In Standard test method for splitting tensile strength of cylindrical concrete specimens. 266–269. (ASTM standards, 2002).

JSCE, Standard Specifications for Concrete Structures, in Standard Specifications for Concrete Structures (Japanese society for civil engineering (jsce), 2010).

Ashour A., S. El-refaie, and S. Garrity. Flexural strengthening of rc continuous beams using cfrp laminates. Cement Concrete Compos. 26 (7), 765–775. (2004).

attari s. amziane, and m. chemrouk, flexural strengthening of concrete beams using cfrp, Gfrp and hybrid Frp sheets. Constr. Build. Mater. 37, 746–757 (2012).

Zhu, Y. et al. Flexural strengthening of reinforced concrete beams or slabs using Ultra-High performance concrete (UHPC): A state of the Art review. Eng. Struct. 205, 110035 (2020).

El meski F. and M. Harajli. Evaluation of the flexural response of cfrp-strengthened unbonded posttensioned members. J. Compos. Constr. 19 (3), 04014052 (2015).

ACI, Committee 318. In Building code requirements for structural concrete and commentary 48331. ((American concrete institute, 2019).

ACI Committee 544.1r-96. In State-of-the-Art report on Fiber Reinforced Concrete. (American concrete institute, 1996).

CEB-FIP, Fib Model Code for Concrete Structures 2010. In International Federation for Structural Concrete (Ernst & Sohn, 2013).

RILEM, test and design methods for steel fibre reinforced concrete - final recommendation. In tc162-tdf. Materials and Structures. 560–567. (2003).

JSCE jsce-sf4: recommendations for design and construction of high-performance fiber reinforced cement composites with multiple fine cracks. In sf4. (Japan society of civil engineers, 2002).

Fib-bulletin-14, fib tg 9.3 frpebr., in externally bonded frp reinforcement for rc structures. fe ́de ́ration internacionale du be ́ton (fib), task group 9.3 frp. 130. (2001).

ACI, guide for the design and construction of externally bonded frp systems for strengthening concrete structures. In committee 440.2r-17. (American concrete institute, 2017).

CSA, design and construction of buildings components with fiber-reinforced polymers. In csa s806-12. (Canadian standards association (csa), 2012).

Xu et al. Effects of coarse aggregate and steel fibre contents on mechanical properties of high performance concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 206, 97–110 (2019).

Shanmugam s. Gopalan, Effect of fibers on strength and elastic properties of Bagasse Ash blended Hpc composites. J. Test. Eval. 48 (2), 922–937 (2020).

Mostofinejad D., H. Bahmani, and J. Afshar. Prediction of mechanical properties of high-performance concrete (hpc) reinforced with steel fibers. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civil Eng. 47 (4), 1971–1993. (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the concrete and structural laboratories of Babol Noshirvani University of Technology in Iran for their support in our experiments. .

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wisam Hamad: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Visualization, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing—original draft, Writing – review & editing. Seyed Sina Mousavi : Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Validation. Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Mehdi Dehestani : Supervision, Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Data curation, Validation, Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hamad, W., Mousavi, S.S. & Dehestani, M. Rebar free high performance ductile concrete beams powered by CFRP and post-tensioning. Sci Rep 16, 3637 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33679-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33679-z