Abstract

The aim of this study was to determine the tolerance-enhancing effect of Lavandula stoechas L. (LSE) against prometryn herbicide using Allium cepa. Six treatment groups were established to assess whether LSE could mitigate prometryn-induced stress: control, LSE (200 and 400 mg/L), prometryn (6000 mg/L), and prometryn combined with LSE (200 and 400 mg/L). Alterations in physiological, genotoxic, biochemical, and root meristematic tissues of A. cepa were systematically evaluated. Prometryn exposure led to substantial physiological deterioration in A. cepa, as evidenced by reductions of 57% in rooting percentage, 83% in root elongation, and 69% in weight gain compared to the control group. Moreover, the mitotic index showed a significant reduction of 26%, while the frequency of chromosomal aberrations, micronuclei formation, and tail DNA percentage demonstrated a pronounced increase, indicating a major genotoxic effect induced by prometryn treatment. In the prometryn-treated group, the most prevalent chromosomal abnormalities included fragment, followed by sticky chromosomes, vagrant chromosomes, chromosomal bridges, unequal chromatin distribution, vacuolated nuclei, and reverse polarization. In the group treated with prometryn, malondialdehyde content increased by 2.7-fold, catalase and superoxide dismutase activities rose by 2.1-fold each, whereas chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b levels declined by 55.4% and 75.5%, respectively, compared to the control. Prometryn treatment also provoked structural changes in the root meristem, including epidermal cell damage, cortex cell damage, thickening of cortex cell walls, flattened cell nucleus, and thickening of conduction tissue. The interaction of prometryn with key macromolecules was further investigated through molecular docking to elucidate its toxicity mechanism. Conversely, co-application of increasing concentrations of LSE alongside prometryn significantly alleviated the physiological, biochemical, and cytogenetic alterations induced by prometryn toxicity. LC–MS/MS analysis revealed that rosmarinic acid, caffeic acid, p-coumaric acid, protocatechualdehyde, sesamol, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, salicylic acid, vanillin, gentisic acid, taxifolin, quercetin, rutin, naringenin, and syringaldehyde were identified as the predominant phenolic constituents. The findings indicate that LSE has a protective effect in A. cepa against prometryn-induced phytotoxicity, genotoxicity, and oxidative stress. This protective capacity is attributed to the potent antioxidant and antigenotoxic properties of LSE, which are likely associated with its rich phenolic composition. The results demonstrated that LSE alone did not exhibit any toxic effects at the tested concentrations, while co-treatment with prometryn significantly alleviated prometryn-induced physiological, cytogenetic, and biochemical alterations. These findings provide the first experimental evidence that LSE exerts a dose-dependent protective role against prometryn toxicity in A. cepa, likely due to its rich phenolic composition and antioxidant capacity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the context of current agricultural practices, herbicides are frequently used to manage the growth of weeds, often with the aim of increasing crop yields. In order to meet the growing need for agricultural products, agrochemicals are considered indispensable1. However, their use can also have detrimental effects on the environment. Although herbicides are intended to act selectively on specific plant species at certain doses, they may also harm non-target plants2. Despite the possibility that even relatively harmless pesticides may accumulate in living organisms over time and pose a carcinogenic, mutagenic, or teratogenic hazard, the toxic characteristics of most pesticides have not yet been adequately investigated.

Prometryn (2,4-bis(isopropylamino)-6-methylthio-s-triazine) is classified as a thiomethyl-s-triazine-type herbicide utilized for the management of annual grass, broad-leaved weeds, moss, aquatic weeds, large grasses, and harmful algae in the fields of cotton, wheat, vegetables, rice, and other crops. Its soil adsorption coefficient (400 Koc) makes it a relatively immobile compound in soil, resulting in its common occurrence as an environmental contaminant3. Prometryn functions by obstructing electron transport and ATP synthesis, suppressing CO2 fixation, impeding photosynthesis by affecting photosystem II, and promoting the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)4. Prometryn can be toxic to aquatic plants and phytoplankton as well as to animals and humans. For this reason, it has been listed as an endocrine-disrupting substance by Japan, the USA, and other countries; banned by the European Union; and restricted in the USA5. On the other hand, despite the known risks, this practice continues in other countries, such as China, the USA, New Zealand, Canada, and South Africa5.

The therapeutic use of plant extracts and pure bioactive chemicals from medicinal plants for the healing and treatment of diseases and disorders has a long historical background stretching back over centuries. Plant extracts contain bioactive molecules that offer a wide range of physiological roles. Lavandula stoechas L. (Lamiaceae) (Karabaş otu, Spanish lavender, French lavender, or topped lavender) is an aromatic medicinal plant native to the Mediterranean region6. The plant has been traditionally used for many years in the treatment of various medicinal conditions, including kidney diseases, digestive disorders, diabetes mellitus, cough, hyperlipidemia, asthma, headache, and flu7. The plant is also referred to as the "broom of the brain" for its traditional use in the treatment of epilepsy, migraine, and memory-related health issues8. The plant is rich in diverse bioactive constituents, including luteolin, camphor, erythrodiol, oleanolic acid, eucalyptol, lavanol, fenchone, longipene-2-ene, lupeol, myrtenol, pinocarvil acetate, terpineol, vergatic acid, ursolic acid, vitexin, β-sitosterol, α-amyrin, and a range of aromatic compounds9. Furthermore, L. stoechas has demonstrated a range of pharmacological properties, including anti-epileptic, antispasmodic, antibacterial, antifungal, sedative, anti-leishmaniasis, anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetic, and cytotoxic effects10.

Higher plants are considered to be excellent biological indicators of pollution sources and can be used to assess both acute and chronic exposure to pollutants11. Allium cepa L. is a widely used, recognized test organism and model plant for determining the toxicity of hazardous chemical compounds and environmental pollutants in laboratory settings12. The Allium test offers a high degree of correlation with other test systems and serves as a guiding framework for challenging experiments on humans and animals13.

This study was conducted with the objective of revealing the acute toxic effects of prometryn herbicide and the tolerance-enhancing effect of L. stoechas extract (LSE) against this chemical using A. cepa. The purpose of the study was to investigate alterations in the physiological, genotoxic, biochemical, and structural characteristics of root meristem tissue in A. cepa. Furthermore, in order to enhance comprehension of the mechanisms of action, the phenolic content of LSE was ascertained by the LC/MS–MS method, and the interaction of proteins vital for prometryn cell division was investigated by the molecular docking method.

Materials and methods

Materials

The A. cepa bulbs utilized in the experimental procedures were procured from a store specializing in agricultural products in Giresun, Türkiye. The L. stoechas used in the study was obtained from Aşçı Baharatları (Ordu, Turkey) and consisted of 100% pure L. stoechas flowers. As the toxic agent, Prometryn (CAS No: 7287-19-6) from the Merck firm (Darmstadt, Germany) was applied. The remaining chemicals utilized in the experimental process were of analytical grade.

For preparation of aqueous L. stoechas extract, 10 g of plant material was mixed with 100 mL of distilled water and incubated in a shaker at room temperature for 24 h. The mixture was then filtered to remove residual solids, and the filtrate was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. After centrifugation, the water was evaporated, and the pellet obtained was used for subsequent analyses.

Experimental plan

The dosage of prometryn selected for the study was determined in accordance with the findings of Karaismailoglu14. Although, 2000–3000 mg/L is the standard agricultural dose of prometryn we used 6000 mg/L to investigate its acute toxicity under controlled laboratory conditions. Therefore, using 6000 mg/L (approximately double the routine dose) enabled us to simulate overuse, or accumulation and better assess potential acute toxic effects on non-target organisms. The concentrations of L. stoechas extract (200 and 400 mg/L) were chosen based on preliminary solubility tests, representing the maximum concentrations fully soluble in water at room temperature without precipitation. These doses also correspond to levels that did not affect the germination percentage of A. cepa in preliminary trials. Six experimental groups were established from fifty healthy A. cepa bulbs, one of which was designated as the control group and administered with tap water, while the remaining five groups were administered with 200 mg/L LSE (LSE-I), 400 mg/L LSE (LSE-II), 6000 mg/L prometryn (PMT), 6000 mg/L prometryn + 200 mg/L LSE (PMTLSE-I), and 6000 mg/L prometryn + 400 mg/L LSE (PMTLSE-II), respectively. The A. cepa bulbs were rooted in beakers so that their basal plates were in contact with the respective treatment solutions. During the experiment, all fifty bulbs were evaluated for their rooting capacity, while ten randomly selected bulbs were subjected to further analyses. And the groups were harvested after 72 h of rooting in the respective solutions in the dark and at a temperature of 23 ± 2 °C. An additional set of 10 bulbs per group, independent of the germination experiment, was maintained under identical conditions for 6 days to obtain samples for chlorophyll analyses.

Physiological analyses

At the end of the 3rd day, physiological changes in A. cepa bulbs were determined by rooting percentage, root length, and bulb weight. The rooting ratio was calculated as the percentage of all bulbs with an mean root length of at least 1 cm; only these onions were included in the calculation. For each bulb, germination was considered 2% when at least 10 adventitious (primary) roots, each reaching ≥ 1 cm in length, were developed. If 5–9 roots of ≥ 1 cm length were present, it was scored as 1%, and if 0–4 roots developed, it was scored as 0%. Due to this categorical scoring system, the maximum possible germination value may be less than 100% depending on the distribution of individual bulb scores. Root elongation (cm) was assessed as the mean of the measurements taken from the freshly developed adventitious roots using a ruler. Weight gain (g) was calculated as the difference in onion weight before and after the experiment, measured using an electronic precision balance with a precision of 0.01 g.

Genotoxicity analyses

To evaluate the genotoxic effects of prometryn and the protective potential of L. stoechas extract, common cytogenetic parameters were analyzed in A. cepa root meristem cells. In this study, the following cytogenetic parameters were used and evaluated: MNs, a small extranuclear bodies composed of whole or fragmented chromosomes that fail to be incorporated into daughter nuclei during cell division and used as markers of genotoxic damage; MI, calculated as the percentage of dividing cells among the total number of observed cells as indicators of cell proliferation and mitotic activity; and CA, structural or numerical abnormalities such as fragments, bridges, and vagrant chromosomes as signs of genotoxic stress and chromosomal instability. Changes in MN, MI, and CA parameters in A. cepa root tips were induced by prometryn and were determined using a squash preparation technique with 1% acetocarmine stain, as previously described by Staykova et al.15. After 24 h of staining, root tip preparations were screened under a research microscope (Irmeco IM-450 TI) at X400 magnification. All images were obtained directly from research microscope without digital modification. Only uniform adjustments of brightness and contrast were applied equally across entire images to enhance visualization, without altering or removing any structural details. The mean of the values obtained from ten preparations was used to determine the results for each group (n = 10). The calculation of MI and CAs was conducted on a total of 1000 cells, with 100 cells from each of 10 slides being analyzed. The MI calculation was performed on a further 10,000 cells, with 1000 cells from each of the 10 slides being analyzed.

Biochemical analyses

The approach proposed by Ünyayar et al.16 was applied to determine the magnitude of the alterations in MDA levels in response to prometryn administration. Freshly extracted A. cepa root tips, weighing 0.5 g, were then mechanically homogenized in 1 mL of a 5% trichloroacetic solution. The homogenate was taken and subjected to a centrifugation process at 12,000 g for a duration of 10 min. Then, a mixture of thiobarbituric acid (0.5%), trichloroacetic acid (20%), and supernatant was combined, and this reaction mixture was first incubated at 96 °C for 30 min and then cooled to stop the reaction. The level of malondialdehyde (MDA) was then determined by measuring the degree of absorption of the optical density of the final mixture obtained by centrifugation of the mixture at 10,000 g for 5 min at a wavelength of 532 nm.

A 0.5 g of root tissue was then subjected to homogenization in 5 mL ice-cold 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) using a cold mortar to obtain the extracts required for determining the activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) enzymes, as was previously described by Zou et al.17. The homogenate was centrifuged for 20 min at 10,500 g, and the supernatant was taken out for analyses.

The activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD), an enzyme that plays a role in antioxidant defense, was assessed using the technique established by Beauchamp and Fridovich18. The method involves the mixing of 1.5 mL of 0.05 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.8), 0.3 mL of 130 mM methionine, 0.3 mL of 750 μM nitroblue tetrazolium chloride (NBT), 0.3 mL of 0.1 mM EDTA-Na2, 0.3 mL of 20 μM riboflavin, 0.01 mL of 4% insoluble polyvinylpyrrolidone, and 0.28 mL of deionized water with 0.01 mL of enzyme extract in a glass tube to create the reaction medium. The reaction medium was first exposed to the light of two 15 W fluorescent lamps for 10 min. This initial step was followed by stopping the medium in the dark for 15 min, after which the SOD activity was calculated using the absorbance measured at 560 nm. One unit (U) of SOD activity was defined as the amount of enzyme causing 50% inhibition of NBT reduction under the assay conditions, and SOD activity was expressed as U/mg protein.

The activity of the CAT enzyme, another significant antioxidant enzyme, was determined through the preparation of a solution that was composed of 1.5 mL of 200 mM monosodium phosphate buffer, 1.0 mL of distilled water, and 0.3 mL of 0.1 M H2O2, by the method proposed by Beers and Sizer19. The speed of the reaction, which was initiated by the addition of 0.2 mL of enzyme extract to this solution, was determined by spectrophotometric measurement of the absorbance at 240 nm over time.

The impact of prometryn on the chlorophyll content of the fresh leaves of A. cepa was analyzed after a 6-day rooting period. In order to prepare the extract for the purpose of chlorophyll analyses, 0.2 g of fresh leaf sample was placed in 5 mL of 80% acetone. The solution was then stored in the dark at + 4 °C20. Subsequent to the end of this period, the samples were crushed and filtered to ensure complete extraction of chlorophyll from the tissues. The filtrate was then added to 5 mL (80%) acetone, and the solution was centrifuged at 1000 g. The green chlorophyll solution located at the very upper end of the tube was measured spectrophotometrically, first at 645 nm and then at 663 nm. The equations proposed by Witham et al.21 were utilized in order to calculate the levels of chlorophyll a and b in fresh tissue.

All biochemical analyses were carried out on ten independent samples (n = 10), with each procedure fully replicated.

Meristem tissue structure analyses

The alterations in the meristem structure of A. cepa root in response to prometryn treatment were studied in the cross-section of roots22. According to this method, the cross-section of A. cepa roots was obtained near the apex with a sharp razor blade. These samples were then transferred to microscope slides, stained with an aqueous solution of methylene blue (1%), and covered with coverslips. Photography of the samples was conducted using a light microscope (Irmeco IM-450 TI model) at × 400 magnification. Subsequent image analysis was then performed on the digital images. All anatomical damages were compared with the control group. From each bulb, 10 root cross-sections were obtained, resulting in 100 sections per group. 0–5 damage: (−) No damage; 6–25 damage: ( +) minor damage; 26–50 damage: (+ +) Moderate damage; 51 or more damage: (+ + +) Severe damage.

Molecular docking analysis

In order to examine possible interactions between prometryn and selected targets, molecular docking studies were conducted on tubulins, DNA topoisomerases, glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferases, and protochlorophyllide reductases. The Protein Data Bank provided the following 3D structures: tubulin (alpha-1B chain and tubulin beta chain) (PDB ID: 6RZB)23, DNA topoisomerase I (PDB ID: 1K4T) and II (PDB ID: 5GWK)24,25, glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase (PDB ID: 2ZSL)26, and protochlorophyllide reductase (PDB ID: 6R48)27. The 3D structure of the prometryn molecule (PubChem CID: 4929) was retrieved from the PubChem database. The preparation of the structure for molecular docking was undertaken by determining the active sites of the proteins, the removal of water molecules and ligands, and the addition of polar hydrogen atoms. Protein energy minimization was performed with Gromos 43B1 with the Swiss-PdbViewer28 (v.4.1.0) program, while energy minimization of the 3D structure of prometryn was performed with the uff-force field with Open Babel v.2.4.0 software29. The allocation of Kollman charges was made to the receptor molecules, while Gasteiger charges were assigned to prometryn. The molecular docking procedure was performed with the grid box containing the active sites of proteins. Subsequently, docking was carried out using Autodock 4.2.6 software30 that employs the Lamarckian genetic algorithm. The Biovia Discovery Studio 2020 Client was used to perform the docking analysis and 3D visualizations.

Determination of phenolic compounds in L. stoechas

Phenolic constituents of L. stoechas were profiled using liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS). A 1 g of dried plant material was extracted in a solvent mixture consisting of methanol and dichloromethane (4:1, v/v). The extract was subsequently passed through a 0.45 μm sterile syringe filter to remove particulate matter prior to analysis. Chromatographic separation was achieved on a Thermo Scientific LC–MS/MS system fitted with a Hypersil ODS column (4.6 × 250 mm). The mobile phase system consisted of two eluents: solvent A (ultrapure water containing 0.1% formic acid) and solvent B (methanol). The gradient elution protocol was programmed as follows: isocratic at 0% B from 0 to 1 min; linear increase to 95% B from 1 to 22 min; held at 95% B until 25 min; followed by a ramp to 100% B by 30 min. The total runtime, including re-equilibration, was set at 34 min. All instrumental analyses were performed at the Central Research Laboratory (HUBTUAM) of Hitit University under standardized operating conditions.

Statistical analysis

The normality of data from the experiment was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests. For statistical analysis, SPSS Statistics 23 (IBM SPSS) software was employed. The evaluation involved one-way ANOVA and Duncan’s multiple range tests. Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and statistical significance was established at a value of p < 0.05.

Results and discussion

The effects of the prometryn herbicide and LSE on the rooting ratio, root elongation, and weight gain of A. cepa bulbs are presented in Table 1. The LSE-I and LSE-II groups treated with LSE exhibited no statistical difference from the control group, which received tap water treatment. These results indicated that 200 mg/L and 400 mg/L LSE did not cause any physiological toxicity in A. cepa (Table 1). Although the results of the present study differ from those reported by Çelik and Aslantürk31, the variation is likely due to the substantially higher LSE concentrations (40,000–120,000 mg/L) used in their experiment compared to the low, non-toxic doses tested here. Prometryn exposure markedly inhibited root growth and biomass accumulation in A. cepa, consistent with its strong phytotoxicity (Table 1). Prometryn, an environmental risk and a widely used herbicide in agricultural areas, has been demonstrated to exert deleterious effects on the growth of non-target plants, including soybeans32 and beans2. Furthermore, the results of our study are in agreement with the study of Çakir et al.33, which showed that prometryn decreased weight gain, germination percentage, and final root length in A. cepa due to its negative effects on RNA synthesis, photosynthesis, lipid synthesis, protein synthesis, and electron transport system, as well as causing oxidative stress. In contrast, the application of LSE in combination with prometryn in the PMTLSE-I and PMTLSE-II groups resulted in higher rooting ratio, root elongation, and weight gain than the PMT- alone group (p < 0.05) (Table 1). In the PMTLSE-II group, which received a higher dose of LSE, a more pronounced improvement in growth indicators was observed. However, the observed improvement did not attain the magnitude seen in the control group. Despite extensive research, no prior study has been found demonstrating a mitigative effect of LSE against pesticide-induced growth retardation in A. cepa. Nonetheless, various studies have reported that plant extracts such as Cornus mas34, Melissa officinalis35, and Ginkgo biloba36 can reduce the adverse effects of pesticides on the growth of A. cepa. Moreover, Yalçın and Çavuşoğlu37 showed that Momordica charantia extract alleviated glyphosate-induced growth inhibition in A. cepa. These findings collectively suggest that the bioactive compounds present in herbal extracts -such as those in L. stoechas- may counteract the negative impacts of pesticides on cell division and plant metabolism through their antioxidant properties.

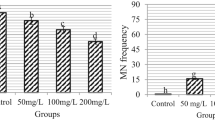

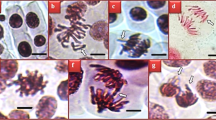

The impacts of prometryn and LSE treatments on genotoxicity indicators are demonstrated in Fig. 1 and Table 2. The highest MI score and the lowest number of MNs (Fig. 1f) and CAs were found in the control, LSE-I (200 mg/L LSE), and LSE-II (200 mg/L LSE) groups, and there was no statistical difference between these groups. In these groups, mitotic normal interphase (Fig. 1a), prophase (Fig. 1b), metaphase (Fig. 1c), anaphase (Fig. 1d), and telophase were observed. The findings of the present study indicate that the tested concentrations of LSE did not exhibit genotoxic effects in A. cepa. In contrast to the LSE treatments, exposure to prometryn at a concentration of 6000 mg/L resulted in a statistically significant reduction in MI and a concomitant increase in the frequencies of MN and CAs in the PMT group (p < 0.05). In contrast to LSE treatments, exposure to prometryn at a concentration of 6000 mg/L led to a 26% reduction in the MI in the PMT group, accompanied by an increase in the frequencies of MN (62.5) and CAs. Application of prometryn also led to the formation of various chromosomal aberrations in root tip meristem cells, with the most frequently observed types being fragments (Fig. 1g), followed by sticky chromosomes (Fig. 1h), vagrant chromosomes (Fig. 1i), chromosomal bridges (Fig. 1j), unequal distribution of chromatin (Fig. 1k), vacuolated nucleus (Fig. 1l), and reverse polarization (Fig. 1m). The genotoxic effects of prometryn were previously reported in the study by Đikić et al.38, in which prometryn caused DNA damage in mouse leukocytes. The findings of this study are consistent with those reported by Karaismailoglu14 and Çakir et al.33, who similarly demonstrated that prometryn exposure led to a reduction in MI and a rise in MN frequency as well as CAs in A. cepa. The genotoxic effects observed in A. cepa may be attributed to prometryn-induced oxidative stress and its direct interaction with DNA, which can lead to disruptions in essential physiological and biochemical pathways, including RNA and protein synthesis33. Parlak39 noted that pesticide-induced toxicity leads to the generation of ROS, which cause mutations in genetic material and consequently impair functions of protein.

Chromosomal damages in A. cepa root meristem caused by prometryn herbicide. Normal interphase (a), normal prophase (b), normal metaphase (c), normal anaphase (d), normal telophase (e), micronucleus (f), fragment (g), sticky chromosome (h), vagrant chromosome (i), bridge (j), unequal distribution of chromatin (k), vacuolated nucleus (l), Reverse polarization (m). Bar = 10 µm.

The co-administration of LSE extract with prometryn resulted in a notable dose-dependent increase in MI values and a decrease in MN and CA values. In the PMTLSE-II group, where the most significant differences were observed as a result of higher doses of LSE, MI increased by 15% and MN decreased by 27% compared to the PMT group. Furthermore, the administration of LSE concomitantly with prometryn led to a statistically significant reduction in all CA types (p < 0.05). The reduction of changes in genotoxic markers suggests that LSE enhances the tolerance of A. cepa to prometryn-induced genotoxicity. When the literature was examined, no study was found on the protective effect of L. stoechas and its extracts, which have many medicinal uses, against genotoxicity in A. cepa. In contrast to the findings of this study, genotoxic effects associated with LSE have been reported in previous studies conducted by Çelik and Aslantürk31 in A. cepa test and by Çelik and Aslantürk40 in human peripheral lymphocyte cells. However, it is important to emphasize that the doses of LSE used in these studies were extremely higher than those used in the present investigation. This difference in dosage may explain the observed differences in genotoxic results. On the other hand, the findings of this study are consistent with prior research demonstrating that plant extracts rich in antioxidants and bioactive compounds can effectively mitigate pesticide-induced genotoxicity. For instance, studies utilizing the A. cepa model have shown the protective effects of various plant-derived substances: Macar et al.41 reported that M. charantia extract conferred anti-genotoxic protection against metaldehyde; Yirmibeş et al.42 similarly found that Camellia sinensis extract alleviated paraquat-induced genotoxicity; and Topatan43 demonstrated the protective role of Achillea millefolium extract against etoxazole-induced genotoxic damage. Plant extracts may exert their antigenotoxic effects not only through the free radical scavenging properties of the polyphenolic compounds they contain but also by induction or inhibition of specific detoxification and repair enzyme44. The overall biological activity of the extract is likely the result of synergistic interactions among various phenolic constituents, rather than the action of a single compound45.

Table 3 summarizes the changes in MDA, chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b levels, SOD, and CAT activities caused by LSE, prometryn, and prometryn applied in a mixture with LSE. In terms of all biochemical parameters, the LSE-I and LSE-II groups treated with LSE exhibited similar mean values with the control group (Table 3). These findings demonstrated that the administered doses of LSE did not induce any adverse effects on membranes, oxidative balance, or pigment content. On the other hand, the PMT group exposed to prometryn herbicide exhibited a significant increase in MDA content and a drastic decrease in pigment levels in comparison to the control group (p < 0.05). The mean values of SOD and CAT activity in this group were also remarkably higher than those recorded in the control group (Table 3). Prometryn triggered oxidative stress, as evidenced by elevated MDA and antioxidant enzyme activities and reduced chlorophyll pigments. It has already been shown that prometryn increases the level of MDA and causes an acceleration of the SOD and CAT enzyme activities in the root meristem cells of A. cepa33. In line with the findings of the present study, Jiang and Yang46 reported that prometryn exposure in Triticum aestivum induced oxidative stress, as evidenced by a reduction in chlorophyll content and an increase in antioxidant enzyme activities, including SOD and CAT. Min et al.47 stated that prometryn exposure triggered ROS production, according to a study conducted with Danio rerio, another bioindicator. Boulahia et al.2 reported that the growth, photosynthetic pigments, and photosynthetic products of Phaseolus vulgaris seedlings grown in soil contaminated with prometryn significantly decreased, while MDA and antioxidant enzyme activities increased. The researchers mentioned above also pointed out that increased doses of prometryn had a significant decrease in enzyme activity, possibly due to the disruption of the structural integrity of the enzymes. Pesticide-induced ROS have been reported to disrupt membrane permeability, cause mitochondrial damage, and induce mutations in DNA47,48. The production of ROS in plants under biotic and abiotic stress, at levels that exceed the power of the antioxidant system, is referred to as oxidative stress. SOD and CAT are two important antioxidant enzymes that function in the suppression of oxidative damage49. The first of these two key antioxidant enzymes catalyzes the breakdown of the peroxide radical into oxygen and hydrogen peroxide, and the second catalyzes the neutralization of hydrogen peroxide by converting it into water and oxygen50. A significant marker of oxidative stress associated with ROS accumulation is the increase in MDA levels in cells. MDA is a product produced by peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids in cellular membranes, and due to its electrophilicity, it attacks DNA, proteins, and enzymes and causes functional disorders in these molecules33. Huang et al.51 suggested that the toxicity of prometryn in non-target organisms is attributable to the disturbance of ROS balance. Indeed, the combined evidence from increased MDA accumulation, enhanced antioxidant enzyme activation, and genotoxicity indicates that prometryn triggers oxidative stress in the meristematic cells of A. cepa roots (Table 3). It has been established that triazine herbicides, including prometryn, not only inhibit growth but also reduce chlorophyll content and photosynthetic efficiency52. In this study, root-applied prometryn decreased the chlorophyll content in newly developing leaves compared to the control group (Table 3). This finding suggests that this herbicide can be transported from the application sites in the root to the upper parts of the plant. Increased levels of radicals such as intrinsic hydrogen peroxide or singlet oxygen have been reported to cause photoinhibition by inhibiting the repair of photosystem II53. It may be suggested that prometryn binds to the D1 protein in the chloroplast, causing an interruption in the electron transport chain, resulting in increased accumulation of ROS and degradation of chlorophyll. Pesticides can also bind directly to photosynthetic pigments, disrupting the structure and function of these molecules, or reduce pigment synthesis by disrupting key enzymes in the chlorophyll synthesis pathway54,55.

Co-administration with LSE reversed these biochemical disruptions, particularly at the higher concentration, demonstrating strong antioxidant and photoprotective activity (Table 3). These changes were more evident in the PMTLSE-II group, in which the dosage of LSE in the mixture was elevated. The findings revealed that the application of LSE, which does not induce adverse effects when used alone in A. cepa cells, led to a reduction in prometryn-induced oxidative stress and membrane damage. Additionally, it exhibited a capacity to protect the photosynthetic apparatus when applied at the same time with prometryn. The present findings are corroborated by those of Tayarani-Najaran et al.56, who previously demonstrated that LSE suppressed ROS accumulation and oxidative stress-induced toxicity associated with 6-hydroxydopamine treatment in PC12 cells. Additionally, the pretreatment of A172 cells with Lavandula viridis extract, another Lavandula species, resulted in a reduction in ROS accumulation, a regulation in the expression of antioxidant enzymes, and an enhancement of cell viability against H2O2 toxicity57. Sebai et al.58 reported that the volatile compounds contained in LSE have high antioxidant capacity, as evidenced by DPPH and radical scavenging activity analysis. Bioactive compounds present in LSE, including naringin, syringic acid, rutin, cinnamic acid, caffeic acid, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, catechin, and p-coumaric acid, have been demonstrated to have significant antioxidant potential59,60, which may contribute to the decline of prometryn-induced biochemical damage in cells of A. cepa root.

Prometryn administration induced a range of structural root meristem tissue abnormalities in A. cepa (Table 4 and Fig. 2). In contrast, treatment with LSE alone (LSE-I and LSE-II groups) did not result in any detectable abnormalities in root meristem tissue (Fig. 2a, c, f, and h). However, the group exposed solely to prometryn exhibited severe epidermis cell damage (Fig. 2b), cortex cell damage (Fig. 2d), thickening of cortex cell walls (Fig. 2e), flattened cell nucleus (Fig. 2g), and thickening of conduction tissue (Fig. 2i). Co-treatment LSE with prometryn (PMTLSE-I and PMTLSE-II groups) led to a dose-dependent amelioration of these abnormalities. In the PMTLSE-II group, LSE significantly reduced epidermis cell damage, cortex cell damage, thickening of cortex cell wall, and flattened cell nucleus to a minor level, while completely preventing thickening of conduction tissue. The findings are in alignment with those of the study conducted by Çakir et al.33, which demonstrated that the administration of prometryn in A. cepa resulted in the thickening of the cortex cell wall, the flattening of cell nuclei, the presence of unclear vascular tissue, and damage to the epidermis and cortex cells. The alterations observed in the configuration of meristematic tissue are the result of a combination of A. cepa's adaptive responses aimed at reducing the uptake of prometryn into the plant, and prometryn-induced damage to cell membranes and DNA33. Furthermore, studies demonstrating the deleterious effects of glyphosate and paraquat herbicides on the root meristem of A. cepa corroborate our findings61,62. In the present study, the deleterious effects of herbicide-induced oxidative stress on root development were observed. Furthermore, other findings of the study also support the idea that herbicide-induced oxidative stress plays a role in impairing root development. On the other hand, co-treatment with LSE significantly mitigated the structural abnormalities caused by prometryn, especially at higher concentrations. The tolerance-enhancing effect of LSE may be related to its antioxidant capacity, which could reduce reactive oxygen species and stabilize cellular components.

Structural root meristem tissue abnormalities caused by the herbicide 6000 mg/L prometryn in A. cepa. Normal appearance of epidermis cells (a), epidermis cell damage (b), normal appearance of cortex cells (c), cortex cell damage (d), thickening of cortex cell wall (e), normal oval-shaped nucleus (f), flattened cell nucleus (g), normal appearance of conduction tissue (h), thickening of conduction tissue (i). Bar = 10 µm.

Molecular docking studies are instrumental in uncovering the interactions between small molecules and macromolecules, providing critical insights into their potential effects on cellular mechanisms63. In this study, molecular docking analyses were performed to evaluate the binding affinities and interaction dynamics of prometryn with a range of essential macromolecules. These macromolecules included tubulins, DNA topoisomerases, glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase, and protochlorophyllide reductase, all of which play vital roles in cellular functions such as microtubule dynamics, DNA topology regulation, amino acid metabolism, and chlorophyll biosynthesis, respectively64,65. The interactions between prometryn and these macromolecules are of significant interest due to their potential consequences for cellular integrity. For instance, disturbances in microtubule dynamics, governed by tubulins, can compromise critical processes like cell division and intracellular transport66. Similarly, alterations in DNA topology, controlled by DNA topoisomerases, may result in karyotypic instability, including chromosomal abnormalities67. Additionally, changes in glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase activity can disrupt amino acid metabolism, while interactions with protochlorophyllide reductase may impair chlorophyll biosynthesis and reduce photosynthetic efficiency68. The outcomes of the molecular docking analysis are detailed in Table 5 and Fig. 3, highlighting the binding affinities and interaction profiles of prometryn with the selected macromolecules. These results offer a basis for understanding the molecular-level effects of prometryn and its broader implications for cellular processes, chromosomal stability, and photosynthetic performance.

Prometryn exhibited a strong binding affinity to the tubulin alpha-1B chain, as indicated by the free energy of binding and a relatively low inhibition constant. The interaction was primarily mediated by two hydrogen bonds with GLU71, suggesting that this residue plays a critical role in stabilizing the binding of prometryn. The absence of hydrophobic interactions implies that the binding is predominantly driven by polar interactions. This strong binding affinity may disrupt the structural integrity or function of tubulin, potentially leading to microtubule destabilization. The binding affinity of prometryn to the tubulin beta chain was slightly stronger compared to the alpha-1B chain, with a comparable inhibition constant. The interaction involved two hydrogen bonds with GLU181 and one with TYR222, along with hydrophobic interactions involving CYS12 and TYR222. The dual nature of these interactions (both polar and hydrophobic) suggests a more complex binding mechanism, which could enhance the stability of the prometryn-tubulin complex. This binding may interfere with tubulin polymerization or depolymerization, further supporting the observed mitotic disruptions and chromosomal abnormalities in the study.

Prometryn showed moderate binding affinity to DNA topoisomerase I, with a free energy of binding of −4.92 kcal/mol and an inhibition constant of 248.28 µM. The interaction was stabilized by two hydrogen bonds each with ASP500 and GLU510, as well as hydrophobic interactions with LEU530 and HIS511. While the binding affinity is lower compared to tubulin, the interaction with DNA topoisomerase I could still impair its function, potentially leading to DNA damage due to the enzyme’s role in relieving torsional stress during DNA replication and transcription. The binding affinity of prometryn to DNA topoisomerase II was similar to that of topoisomerase I (−4.90 kcal/mol), with an inhibition constant of 254.86 µM. The interaction involved three hydrogen bonds with ASP541 and two with GLU461, along with hydrophobic interactions with ALA46, LEU616, and HIS759. These interactions suggest that prometryn may bind to the active site or a regulatory region of topoisomerase II, potentially inhibiting its function.

Prometryn exhibited a relatively lower binding affinity to glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase with an inhibition constant of 444.65 µM. The interaction involved hydrogen bonds with ALA301, GLU123 (× 2), and THR303, as well as a hydrophobic interaction with ALA301. This enzyme plays a crucial role in chlorophyll biosynthesis, and its inhibition by prometryn could explain the observed reduction in chlorophyll content in the study. The binding, although weaker compared to other targets, may still be sufficient to disrupt the function of the enzyme, leading to disruption of amino acid metabolism and chlorophyll production.

The binding affinity of prometryn to protochlorophyllide reductase was similar to that of glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase, with an inhibition constant of 457.29 µM. The interaction involved hydrogen bonds with GLY15 and ASN86 (× 2), along with extensive hydrophobic interactions with multiple residues (VAL14, ALA88, VAL223, LEU228, LYS193, LEU139, PHE229). This enzyme is also involved in chlorophyll biosynthesis, and its inhibition by prometryn could further contribute to the observed reduction in chlorophyll content. The extensive hydrophobic interactions suggest that prometryn binds deeply within the active site, potentially causing significant functional disruption.

The molecular docking results provide strong evidence that prometryn interacts with multiple macromolecules involved in critical cellular processes, including microtubule dynamics (tubulin), DNA integrity (topoisomerases), and chlorophyll biosynthesis (glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase and protochlorophyllide reductase). The high binding affinities to tubulin, in particular, align well with your experimental observations of chromosomal abnormalities and mitotic disruptions. Similarly, the interactions with chlorophyll biosynthesis enzymes support the observed decrease in chlorophyll content. These findings collectively suggest that prometryn exerts its toxic effects through multiple mechanisms, disrupting both structural and metabolic processes. Results of our study align with Çakir et al.33 reported that prometryn binds strongly to tubulin and DNA topoisomerases, disrupting mitotic spindle formation and genomic stability in A. cepa. These findings broaden the mechanistic understanding of Prometryn toxicity by linking its genotoxic effects with interference in photosynthetic metabolism.

Medicinal plants, which contain a wide variety of secondary metabolites, are generous gifts of nature. A notable component of secondary metabolites is phenolic compounds, which are distinguished by the presence of a phenol ring in their molecular structure68. The accumulation of phenolic chemicals in plant tissues is considered an adaptive response of the plant to biotic and abiotic stressors69. The efficacy of phenolic compounds can be attributed to their inherent antibacterial properties, antioxidant activities, particularly the capacity to neutralize ROS, and their ability to reinforce cellular barrier function and stimulate defense gene activation70. According to the phenolic profile determined by LC/MS–MS, the phenolic compounds found in LSE were rosmarinic acid, caffeic acid, p-coumaric acid, protocatechualdehyde, sesamol, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, salicylic acid, vanillin, gentisic acid, taxifolin, quercetin, rutin, naringenin, and syringaldehyde, from most to least (Table 6 and Fig. 4). Although the phenolic contents of LSE have been previously revealed by various studies, factors such as the extraction method, the solvent utilized, the geographical region in which the plant is cultivated, and the age of the plant have caused changes in the results obtained71. In this study, growth retardation (Table 1), genotoxicity (Table 2), oxidative stress (Table 3), and meristematic tissue damage (Table 4) were alleviated, and pigment content (Table 3) was increased in the PMTLSE-I and PMTLSE-II groups exposed to LSE mixed with Prometryn compared to the PMT group exposed to prometryn alone. As the dose of LSE in the mixture increased, the therapeutic effect also increased. In this study, the protective activity of LSE against the pesticide prometryn in A. cepa was demonstrated for the first time. However, Tayarani-Najaran et al.56 demonstrated that pretreatment with phenolic-rich LSE led to a reduction in 6-hydroxydopamine-induced free radical formation and an enhancement in cell viability. In addition, the protective potential of various plant extracts against pesticide-induced multiple toxicity in A. cepa has been previously 42,72. The most prevalent phenolic compound present in LSE was identified as rosmarinic acid, a finding that aligns with the observations reported in the study by Karan73. Zhang et al.74 proved that rosmarinic acid promoted SOD and CAT activity in kidney and liver tissues of aging mice and reduced MDA formation, contributing to membrane integrity. In addition, rosmarinic acid was shown to reduce ethanol-induced DNA damage in mice by Comet assay75. Furthermore, Arikan et al.76 reported that rosmarinic acid contributes to the maintenance of photosynthetic efficiency by reducing radical accumulation and protecting the photosynthetic apparatus in Arabidopsis thaliana exposed to heat stress. Caffeic acid, one of the most abundant phenolic compounds in LSE (Table 6), has been reported to reduce DNA damage caused by oxidative stress by chelating intracellular iron77. In addition, according to the study of Sevgi et al.78 rosmarinic acid and caffeic acid found in remarkable amounts in LSE, were strong protectors for DNA against the toxic and mutagenic effects of hydrogen peroxide and UV. The antioxidant property of p-coumaric acid has been associated with the presence of a phenyl hydroxyl group that allows it to donate hydrogen or electrons79. It has also been stated that the antioxidant and anticancer properties of p-coumaric acid and caffeic acid depend on prooxidant-antioxidant equilibria in the presence of reduced glutathione80. Mehmood et al.81 showed that caffeic acid increased growth, antioxidant enzyme activities, mineral and water content, and decreased lipid peroxidation and hydrogen peroxide accumulation in T. aestivum under salt stress. Protocatechualdehyde, which was abundant in LSE (Table 6), has been suggested to be effective in alleviating chromium-induced oxidative stress by quenching ROS and free nitrogen species, preventing DNA and apoptosis, and affecting enzymes and proteins in membranes82. Kumar et al.83 demonstrated that sesamol, which was found to be ranked fifth in terms of abundance in LSE (Table 6), led to a reduction in the frequency of radiation-induced total CAs and MNs and Comet tail DNA % in mice. Phenolic compounds in the composition of LSE applied to A. cepa from the root medium were effective in protecting the photosynthetic pigments in the leaves of the plant. In support of these findings, Nehela et al.84 demonstrated that benzoic acid and protocatechuic acid enhanced growth and chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b content while also contributing to the regulation of ROS homeostasis in response to toxicity caused by Alternaria solani in tomato. Salicylic acid is considered to be a significant contributor to the protection of A. cepa against the toxicity of prometryn (Table 6). Indeed, according to Fatma et al.85, exogenously applied salicylic acid reduced oxidative stress and increased photosynthetic pigment content in Vigna radiata subjected to pesticide stress.

The results of this study clearly show that LSE improves A. cepa’s tolerance to prometryn-induced toxicity. LSE appears to has an important role in protecting cellular function under oxidative stress caused by the prometryn. This protection likely results from its ability to enhance ROS scavenging and stabilize cell membranes. The extract may also contribute to DNA repair and cell-cycle regulation, complementing its antioxidant role. These observations agree with previous work reporting that essential oils from L. stoechas reduce genotoxicity and strengthen antioxidant systems in organisms exposed to pesticides 86,87.

The protective activity of LSE stems from its high content of phenolic acids and other bioactive molecules with metal-chelating and radical-scavenging abilities. By rapidly neutralizing superoxide and hydroxyl radicals, these compounds prevent lipid peroxidation and protect photosynthetic pigments. Studies with lavender extracts have shown similar effects, reduced pesticide-induced oxidative injury and enhanced enzymatic antioxidants88. Comparable mechanisms likely help A. cepa maintain genomic stability, protect spindle and chromosomal structures, and sustain ROS balance. Altogether, this study offers the first experimental evidence that LSE enhances plant resistance to prometryn toxicity by reducing oxidative and genotoxic stress while reinforcing intrinsic antioxidant defenses and preserving genomic integrity.

Conclusion

The present study offers information about the potential role of LSE in enhancing the tolerance of A. cepa to prometryn-induced toxicity under laboratory conditions. In line with prior research on herbicide toxicity, elevated doses of prometryn elicited acute phytotoxic, oxidative, and genotoxic effects in A. cepa. In contrast, LSE exhibited a dose-dependent protective effect, which may be attributed to its diverse and rich phytochemical composition capable of mitigating oxidative damage and improving cellular resilience. While earlier reports have described toxic and genotoxic outcomes of LSE at high concentrations, the present findings suggest that moderate and optimized low doses may exert beneficial, rather than deleterious, effects. Overall, these results indicate the potential applicability of LSE as a bioprotective agent against pesticide-induced stress. However, the findings are limited to short-term laboratory conditions using A. cepa, and further in vivo and field-based studies are needed to identify the specific phytochemicals responsible for these effects and to verify their efficacy in different organisms and environments.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Dhananjayan, V., Jayanthi, P., Jayakumar, S. & Ravichandran, B. Agrochemicals impact on ecosystem and bio-monitoring. In Resources use efficiency in agriculture (eds Kumar, S. et al.) 349–388 (Springer, Cham, 2020).

Boulahia, K., Carol, P., Planchais, S. & Abrous-Belbachir, O. Phaseolus vulgaris L. seedlings exposed to prometryn herbicide contaminated soil trigger an oxidative stress response. J. Agric. Food Chem. 64, 3150–3160 (2016).

Gui, Y. et al. Root exudation of prometryn and its metabolites from Chinese celery (Apium graveolens). J. Pestic. Sci. 47, 1–7 (2022).

Li, Q. P. et al. Warning analysis on excess prometryne residues of aquatic products in China. J. Food Saf. Qual. 5, 108–112 (2014).

Ni, J. et al. Removal of prometryn from hydroponic media using marsh pennywort (Hydrocotyle vulgaris L.). Int. J. Phytoremediation. 20, 909–913 (2018).

Turgut, K., Baydar, H. & Telci, I. Cultivation and breeding of medicinal and aromatic plants in Turkey. In Medicinal and Aromatic Plants of Turkey (eds Máthé, A. & Turgut, K.) 131–167 (Springer, Cham, 2023).

Benítez, G., González-Tejero, M. R. & Molero-Mesa, J. Pharmaceutical ethnobotany in the western part of Granada province (southern Spain): Ethnopharmacological synthesis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 129, 87–105 (2010).

Gilani, A. H. et al. Ethnopharmacological evaluation of the anticonvulsant, sedative and antispasmodic activities of Lavandula stoechas L.. J. Ethnopharmacol. 71, 161–167 (2000).

Bouyahya, A. et al. Lavandula stoechas essential oil from Morocco as novel source of antileishmanial, antibacterial and antioxidant activities. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 12, 179–184 (2017).

Mushtaq, A. et al. Biomolecular evaluation of Lavandula stoechas L. for nootropic activity. Plants 10, 1259 (2021).

Camilo-Cotrim, C. F., Bailão, E. F. L. C., Ondei, L. S., Carneiro, F. M. & Almeida, L. M. What can the Allium cepa test say about pesticide safety? A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 48088–48104 (2022).

Srivastava, A. K. & Singh, D. Assessment of malathion toxicity on cytophysiological activity, DNA damage and antioxidant enzymes in root of Allium cepa model. Sci. Rep. 10, 886 (2020).

Leme, D. M. & Marin-Morales, M. A. Allium cepa test in environmental monitoring: A review on its application. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 682, 71–81 (2009).

Karaismailoglu, M. C. Investigation of the potential toxic effects of prometryne herbicide on Allium cepa root tip cells with mitotic activity, chromosome aberration, micronucleus frequency, nuclear DNA amount and comet assay. Caryologia 68, 323–329 (2015).

Staykova, T. A., Ivanova, E. N. & Velcheva, D. G. Cytogenetic effect of heavy-metal and cyanide in contaminated waters from the region of southwest Bulgaria. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 41–46 (2005).

Ünyayar, S., Celik, A., Çekiç, F. Ö. & Gözel, A. Cadmium-induced genotoxicity, cytotoxicity and lipid peroxidation in Allium sativum and Vicia faba. Mutagenesis 21, 77–81 (2006).

Zou, J., Yue, J., Jiang, W. & Liu, D. Effects of cadmium stress on root tip cells and some physiological indexes in Allium cepa var. agrogarum L.. Acta Biol. Cracov. Ser. Bot. 54, 129–141 (2012).

Beauchamp, C. & Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutase: Improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 44, 276–287 (1971).

Beers, R. F. & Sizer, I. W. A spectrophotometric method for measuring the breakdown of hydrogen peroxide by catalase. J. Biol. Chem. 195, 133–140 (1952).

Kaydan, D., Yagmur, M. & Okut, N. Effects of salicylic acid on the growth and some physiological characters in salt stressed wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). J. Agric. Sci. 13, 114–119 (2007).

Witham, F. H., Blaydes, D. R. & Devlin, R. M. in Experiments in Plant Physiology. (eds Witham, F. H.) 1–11 (Van Nostrand Reinhold Co, 1971).

Ayhan, B. S. et al. A comprehensive analysis of royal jelly protection against cypermethrin-induced toxicity in the model organism Allium cepa L., employing spectral shift and molecular docking approaches. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 203, 105997 (2024).

Lacey, S. E., He, S., Scheres, S. H. & Carter, A. P. Cryo-EM of dynein microtubule-binding domains shows how an axonemal dynein distorts the microtubule. Elife 8, e47145 (2019).

Staker, B. L. et al. The mechanism of topoisomerase I poisoning by a camptothecin analog. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99, 15387–15392 (2002).

Wang, Y. R. et al. Producing irreversible topoisomerase II-mediated DNA breaks by site-specific pt (II)-methionine coordination chemistry. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 10861–10871 (2017).

Mizutani, H. & Kunishima, N. Crystal structure of glutamate-1-semialdehyde 2,1-aminomutase from Aeropyrum pernix. https://doi.org/10.2210/pdb2ZSL/pdb (2011).

Zhang, S. et al. Structural basis for enzymatic photocatalysis in chlorophyll biosynthesis. Nature 574, 722–725 (2019).

Guex, N. & Peitsch, M. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-pdb viewer: An environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 18, 2714–2723 (2005).

O’Boyle, N. M. et al. Open Babel: An open chemical toolbox. J. Cheminform. 3, 33 (2011).

Morris, G. M. et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 2785–2791 (2009).

Çelik, T. A. & Aslantürk, Ö. S. Cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of Lavandula stoechas aqueous extracts. Biologia 62, 292–296 (2007).

Mohammed, A. H. M. & Amin, R. S. H. Prometryn effects on growth, yield and chemical composition of the harvested seeds of soybean plants. J. Appl. Sci. Res. 3, 476–484 (2007).

Çakir, F., Kutluer, F., Yalçin, E., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Acar, A. Deep neural network and molecular docking supported toxicity profile of prometryn. Chemosphere 340, 139962 (2023).

Kalefetoğlu Macar, T., Macar, O., Yalçιn, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Preventive efficiency of cornelian cherry (Cornus mas L.) fruit extract in diniconazole fungicide-treated Allium cepa L. roots. Sci. Rep. 11, 2534 (2021).

Üstündağ, Ü., Macar, O., Kalefetoğlu Macar, T. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Effect of Melissa officinalis L. leaf extract on manganese-induced cyto-genotoxicity on Allium cepa L.. Sci. Rep. 13, 22110 (2023).

Kesti, S., Macar, O., Kalefetoğlu Macar, T., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Yalçın, E. Investigation of the protective role of Ginkgo biloba L. against phytotoxicity, genotoxicity and oxidative damage induced by Trifloxystrobin. Sci. Rep. 14, 19937 (2024).

Yalçin, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Spectroscopic contribution to glyphosate toxicity profile and the remedial effects of Momordica charantia. Sci. Rep. 12, 20020 (2022).

Đikić, D. et al. The effects of prometryne on subchronically treated mice evaluated by scge assay. Biol. Futur. 60, 35–43 (2009).

Parlak, V. Evaluation of apoptosis, oxidative stress responses, AChE activity and body malformations in zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos exposed to deltamethrin. Chemosphere 207, 397–403 (2018).

Çelik, T. A. & Aslantürk, Ö. S. Cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of aqueous extracts of Rosmarinus officinalis L., Lavandula stoechas L. and Tilia cordata Mill. on in vitro human peripheral blood lymphocytes. Cumhuriyet Sci. J. 39, 127–143 (2018).

Macar, O., Kalefetoğlu Macar, T., Yalçin, E., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Acar, A. Molecular docking and spectral shift supported toxicity profile of metaldehyde mollucide and the toxicity-reducing effects of bitter melon extract. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 187, 105201 (2022).

Yirmibeş, F., Yalçin, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Protective role of green tea against paraquat toxicity in Allium cepa L.: Physiological, cytogenetic, biochemical, and anatomical assessment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 23794–23805 (2022).

Topatan, Z. Ş et al. Alleviatory efficacy of Achillea millefolium L. in etoxazole-mediated toxicity in Allium cepa L.. Sci. Rep. 14, 31674 (2024).

Rajam Srividya, A., Sangai Palanisamy Dhanabal, V. & Vishnuvarthan, J. Mutagenicity/antimutagenicity of plant extracts used in traditional medicine: A review. World J. Pharm. Res. 2, 236–259 (2012).

Mersch-Sundermann, V. et al. Assessment of the DNA damaging potency and chemopreventive effects towards BaP-induced genotoxicity in human derived cells by Monimiastrum globosum, an endemic Mauritian plant. Toxicol. In Vitro 20, 1427–1434 (2006).

Jiang, L. & Yang, H. Prometryne-induced oxidative stress and impact on antioxidant enzymes in wheat. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 72, 1687–1693 (2009).

Min, N. et al. Developmental toxicity of prometryn induces mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and failure of organogenesis in zebrafish (Danio rerio). J. Hazard. Mater. 443, 130202 (2023).

Stara, A., Kristan, J., Zuskova, E. & Velisek, J. Effect of chronic exposure to prometryne on oxidative stress and antioxidant response in common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.). Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 105, 18–23 (2013).

Sule, R. O., Condon, L. & Gomes, A. V. A common feature of pesticides: Oxidative stress-the role of oxidative stress in pesticide-induced toxicity. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 5563759 (2022).

Shakir, S. K. et al. Pesticide-induced oxidative stress and antioxidant responses in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) seedlings. Ecotoxicol. 27, 919–935 (2018).

Huang, P. et al. Prometryn exposure disrupts the intestinal health of Eriocheir sinensis: Physiological responses and underlying mechanism. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 277, 109820 (2024).

Wang, Z. et al. Effects of co-exposure of the triazine herbicides atrazine, prometryn and terbutryn on Phaeodactylum tricornutum photosynthesis and nutritional value. Sci. Total Environ. 807, 150609 (2022).

Murata, N., Takahashi, S., Nishiyama, Y. & Allakhverdiev, S. I. Photoinhibition of photosystem II under environmental stress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1767, 414–421 (2007).

Liu, N., Huang, J., Liu, X., Wu, J. & Huang, M. Pesticide-induced metabolic disruptions in crops: A global perspective at the molecular level. Sci. Total Environ. 957, 177665 (2024).

Shahid, M., Shafi, Z., Ilyas, T., Singh, U. B. & Pichtel, J. Crosstalk between phytohormones and pesticides: Insights into unravelling the crucial roles of plant growth regulators in improving crop resilience to pesticide stress. Sci. Hortic. 338, 113663 (2024).

Tayarani-Najaran, Z. et al. Protective effects of Lavandula stoechas L. methanol extract against 6-OHDA-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 273, 114023 (2021).

Costa, P., Sarmento, B., Gonçalves, S. & Romano, A. Protective effects of Lavandula viridis L’Hér extracts and rosmarinic acid against H2O2-induced oxidative damage in A172 human astrocyte cell line. Ind. Crop. Prod. 50, 361–365 (2013).

Sebai, H. et al. Lavender (Lavandula stoechas L.) essential oils attenuate hyperglycemia and protect against oxidative stress in alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Lipids Health Dis. 12, 189 (2013).

Ezzoubi, Y., Bousta, D. & Farah, A. A phytopharmacological review of a Mediterranean plant: Lavandula stoechas L.. Clin. Phytosci. 6, 1–9 (2020).

Elrherabi, A. et al. Antidiabetic potential of Lavandula stoechas aqueous extract: Insights into pancreatic lipase inhibition, antioxidant activity, antiglycation at multiple stages and anti-inflammatory effects. Front. Pharmacol. 15, 1443311 (2024).

Çavuşoğlu, K. Investigation of toxic effects of the glyphosate on Allium cepa. J. Agric. Sci. 17, 131–142 (2011).

Acar, A., Çavuşoğlu, K., Türkmen, Z., Çavuşoğlu, K. & Yalçın, E. The investigation of genotoxic, physiological and anatomical effects of paraquat herbicide on Allium cepa L. Cytologia 80, 343–351 (2015).

Kitchen, D. B., Decornez, H., Furr, J. R. & Bajorath, J. Docking and scoring in virtual screening for drug discovery: Methods and applications. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 3, 935–949 (2004).

Buey, R. M., Díaz, J. F. & Andreu, J. M. The nucleotide switch of tubulin and microtubule assembly: A polymerization-driven structural change. Biochem. 45, 5933–5938 (2006).

Vedalankar, P. & Tripathy, B. C. Evolution of light-independent protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase. Protoplasma 256, 293–312 (2019).

Parker, A. L., Kavallaris, M. & McCarroll, J. A. Microtubules and their role in cellular stress in cancer. Front. Oncol. 4, 153 (2014).

Zagnoli-Vieira, G. & Caldecott, K. W. Untangling trapped topoisomerases with tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterases. DNA Repair 94, 102900 (2020).

Nisa, R. U. et al. Plant phenolics with promising therapeutic applications against skin disorders: A mechanistic review. Agric. Food Res. 16, 101090 (2024).

Luna-Guevara, M. L., Luna-Guevara, J. J., Hernández-Carranza, P., Ruíz-Espinosa, H. & Ochoa-Velasco, C. E. Phenolic compounds: A good choice against chronic degenerative diseases. Stud. Nat. Prod. Chem. 59, 79–108 (2018).

Saini, N. et al. Exploring phenolic compounds as natural stress alleviators in plants-a comprehensive review. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 133, 102383 (2024).

Celep, E., Akyüz, S., İnan, Y. & Yesilada, E. Assessment of potential bioavailability of major phenolic compounds in Lavandula stoechas L. ssp. stoechas. Ind. Crops. Prod. 118, 111–117 (2018).

Kutluer, F., Güç, İ, Yalçın, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Toxicity of environmentally relevant concentration of esfenvalerate and Taraxacum officinale application to overcome toxicity: A multi-bioindicator in-vivo study. Environ. Pollut. 373, 126111 (2025).

Karan, T. Metabolic profile and biological activities of Lavandula stoechas L. Cell. Mol. Biol. 64, 1–7 (2018).

Zhang, Y., Chen, X., Yang, L., Zu, Y. & Lu, Q. Effects of rosmarinic acid on liver and kidney antioxidant enzymes, lipid peroxidation and tissue ultrastructure in aging mice. Food Funct. 6, 927–931 (2015).

De Oliveira, N. C. et al. Rosmarinic acid as a protective agent against genotoxicity of ethanol in mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 50, 1208–1214 (2012).

Arikan, B., Ozfidan-Konakci, C., Alp, F. N., Zengin, G. & Yildiztugay, E. Rosmarinic acid and hesperidin regulate gas exchange, chlorophyll fluorescence, antioxidant system and the fatty acid biosynthesis-related gene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana under heat stress. Phytochemistry 198, 113157 (2022).

Kitsati, N. et al. Lipophilic caffeic acid derivatives protect cells against H2O2-Induced DNA damage by chelating intracellular labile iron. J. Agric. Food Chem. 60, 7873–7879 (2012).

Sevgi, K., Tepe, B. & Sarikurkcu, C. Antioxidant and DNA damage protection potentials of selected phenolic acids. Food Chem. Toxicol. 77, 12–21 (2015).

Roychoudhury, S. et al. Scavenging properties of plant-derived natural biomolecule para-coumaric acid in the prevention of oxidative stress-induced diseases. Antioxidants 10, 1205 (2021).

Kadoma, Y. & Fujisawa, S. A comparative study of the radical-scavenging activity of the phenolcarboxylic acids caffeic acid, p-coumaric acid, chlorogenic acid and ferulic acid, with or without 2-mercaptoethanol, a thiol, using the induction period method. Molecules 13, 2488–2499 (2008).

Mehmood, H. et al. Assessing the potential of exogenous caffeic acid application in boosting wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) crop productivity under salt stress. PLoS ONE 16, e0259222 (2021).

Singh, V. et al. Hexavalent-chromium-induced oxidative stress and the protective role of antioxidants against cellular toxicity. Antioxidants 11, 2375 (2022).

Kumar, A. et al. Sesamol attenuates genotoxicity in bone marrow cells of whole-body γ-irradiated mice. Mutagenesis 30, 651–661 (2015).

Nehela, Y. et al. Benzoic acid and its hydroxylated derivatives suppress early blight of tomato (Alternaria solani) via the induction of salicylic acid biosynthesis and enzymatic and nonenzymatic antioxidant defense machinery. J. Fungi 7, 663 (2021).

Fatma, F., Kamal, A. & Srivastava, A. Exogenous application of salicylic acid mitigates the toxic effect of pesticides in Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek. J. Plant Growth Regul. 37, 1185–1194 (2018).

Selmi, S., Rtibi, K., Grami, D., Sebai, H. & Marzouki, L. Lavandula stoechas essential oils protect against malathion-induced reproductive disruptions in male mice. Lipids Health Dis. 17, 253 (2018).

Boubsil, S., Djemil, H., Mergued, A. & Abdennour, C. Lavender (Lavandula stoechas) essential oils attenuate Lambda-Cyhalothrin induced liver damage in Rabbit. Bol. Latinoam. Caribe. Plantas Med. Aromát. 24, 236–244 (2025).

Hajirezaee, S. et al. Protective effects of dietary lavender (Lavandula officinalis) essential oil against malathion-induced toxicity in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Ann. Anim. Sci. 22, 1087–1096 (2022).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.M. and T.K.M designed the experiments; O. M., T. K. M., A. A., K.Ç. and E. Y. performed the analyses; O.M. and T. K. M. wrote the manuscript with the help of A. A, K. Ç and E.Y edited the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Statement regarding experimental research on plants

Experimental research and field studies on plants and plant parts (A. cepa bulbs), including the collection of plant material, comply with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Macar, O., Kalefetoğlu Macar, T., Çavuşoğlu, K. et al. The role of Lavandula stoechas L. extract in enhancing tolerance to prometryn toxicity. Sci Rep 16, 1887 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33722-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33722-z