Abstract

Rocks in enhanced geothermal systems (EGS) are often subjected to both thermal shock and dynamic loading. In this study, we use the discrete element method (DEM) to develop a numerical model of granite and systematically investigate crack evolution and damage under the combined effects of sinusoidal dynamic loading and thermal shock applied after cooling. Results show that the highest crack formation occurs during cooling, primarily as tensile and tensile-shear cracks. Crack density increases with both thermal shock temperatures and the number of dynamic load cycles. At a high-temperature case studied (500 °C), mechanical properties deteriorate significantly, accompanied by extensive crack development. DEM simulations visualizing crack propagation and damage evolution provide critical numerical insights for reservoir stimulation and wellbore stability assessment in EGS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

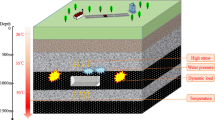

Over recent decades, the extensive reliance on fossil fuels has led to the release of substantial amounts of harmful gases, particularly CO2. These hazardous gases have been released into the atmosphere, which not only triggers severe pollution but also gives rise to a range of ecological damage and environmental problems1,2. Growing awareness of ecological sustainability has prompted researchers to pursue green, renewable alternatives to conventional fossil fuels. Among these, geothermal energy, derived from the Earth’s internal heat, offers several advantages, including abundant reserves, wide geographic distribution, low carbon emissions, high safety, and renewability3,4. Geothermal energy is usually associated with hot dry rock (HDR), a rock type that is mainly made up of granite5.

The primary approach to harnessing geothermal energy is the Enhanced Geothermal System (EGS). This method involves drilling into HDR formations and using hydraulic fracturing to increase reservoir permeability, thereby creating effective pathways for heat extraction. Throughout the drilling and fracturing processes, HDR is subjected to the combined effects of cooling from the working fluid and dynamic mechanical loads. These interactions induce rock fracturing, which is essential for creating the necessary flow channels. However, these same processes can also adversely affect wellbore stability. Consequently, investigating the HDR mechanical behavior under the combined influences of thermal shock and dynamic loading is of paramount importance for the efficient and safe extraction of geothermal energy6.

Numerous studies have considered high-temperature conditions to examine the mechanical and damage behavior of HDR. Existing experimental and numerical simulation research indicates that elevated temperatures can initiate and propagate cracks within rocks. For instance, Yao et al.7 studied coarse-grained marble heated to 200 °C, 400 °C, and 600 °C, and found that while heating improved ductility to some extent, it also caused damage. Similarly, thermal experiments on granite within 100–800 °C8,9,10 showed that mechanical properties degrade markedly once temperatures exceed 400 °C, accompanied by accelerated crack growth. The formation of thermal cracks is mainly attributed to mismatches in thermal conductivity and expansion among mineral constituents. These variations create uneven temperature gradients and deformation incompatibilities, generating thermal stresses that accumulate at mineral boundaries, cleavage planes, or defects. When these stresses exceed a critical threshold, cracks typically initiate along mineral edges, within crystals, or at particle contacts. Numerical simulations11,12,13,14 across temperatures from 200 to 1000 °C have yielded conclusions consistent with experimental observations, showing that local stress concentrations induced by thermal expansion are a potential mechanism for the initiation of thermal cracking. Moreover, the crack density increases with temperature, with the cracks predominantly localized at the grain boundaries. Factors such as grain size distribution and shape also influence crack propagation during heating. Kim et al.15 examined igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic rocks subjected to heat treatment at 100 °C, 200 °C, and 300 °C, followed by rapid fan cooling, and subsequent cyclic heating and cooling at 100 °C. Their findings indicated that rocks with higher heterogeneity and coarser grains exhibited a greater propensity for crack propagation, whereas finer and more homogeneous rocks showed a higher potential for crack healing.

Given the prevalence of cooling processes during geothermal energy extraction, research into the effects of thermal shock on the mechanical properties and damage behavior of HDR has gained increasing attention. Numerous experimental studies16,17,18,19 have demonstrated that thermal shock induces more severe crack propagation in HDR compared to heating alone. For example, Wang et al.20 conducted physical tests and static-dynamic mechanical experiments on red sandstone subjected to 10, 20, 30, and 40 thermal shock cycles, finding that thermal shock significantly degraded most of its physical and mechanical properties. Han et al.21 investigated the effects of rapid thermal cooling on sandstone heated between 100 °C and 800 °C using uniaxial compression, wave velocity, acoustic emission, and SEM analyses. Their results showed that both density and P-wave velocity decay rates increased with temperature. Wu et al.22 examined granite, shale, and sandstone subjected to liquid nitrogen cooling after heating to different temperatures, and reported that higher initial temperatures led to greater damage, mainly through the development of intergranular cracks. Huang et al.23 studied granite with pre-existing flaws under thermal shock, finding that both the flaws and thermal shock significantly impacted the rock’s properties, with thermal damage escalating gradually with increasing temperature.

To further analyze the evolution and mechanisms of thermally induced fractures in HDR under thermal shock, numerous numerical simulations have been conducted. Yang et al.24 developed a thermo-mechanical model to analyze the mechanical response of heterogeneous granites and demonstrated that, maximum thermal stress during cooling was over 30% higher than during heating under the same temperature conditions. The thermo-mechanical coupling model developed by Zhou and Zhu25 suggests that cooling also induces an increase in the number of cracks in granite. When the heating temperature rises from 200 to 600 °C, the number of cracks increases, strength decreases, and the failure mode progressively transitions from shear failure to a mixed mode of tensile and shear failure. Additionally, Wang et al.26 identified that tensile stress–induced micro-crack extension and coalescence are the primary drivers of granite degradation during cooling. Other studies27,28 on cyclic thermal shock demonstrated that thermal stress type and distribution govern micro-crack initiation and propagation: tensile stress generates open cracks perpendicular to its direction, while compressive stress enlarges pre-existing cracks along the compression axis. Once micro-crack density reaches a threshold, further thermal shock does not greatly increase crack numbers but instead enlarges existing crack length and aperture. Wu et al.29 modeled the damage behavior of granites treated by high temperatures under water-cooling impacts, concluding that crack growth is influenced not only by mineral grain expansion but also by moisture evaporation and mineral phase transitions.

In summary, the aforementioned studies highlight how thermal treatment and thermal shock alter rock properties, emphasizing their effects on fracture development and the links between temperature, stress, and mechanical degradation. Although valuable numerical studies exist, current research still heavily relies on experimental methods, which typically only allow observation of the final failure state. Capturing the real-time evolution of internal temperature and stress within rocks remains challenging, leading to significant constraints in understanding the dynamic damage process due to implementation difficulties or excessive costs. Moreover, most existing studies26,27,30,31 focus on single factors (e.g., solely thermal treatment or dynamic loads) and neglect the critical combined effects of these elements. Therefore, this study uses the Particle Flow Code (PFC), a discrete element-based numerical method that represents rock as an assembly of particles, to examine the effects of combined thermal treatment and dynamic loading. Through PFC simulations, this research aims to directly observe crack propagation and damage evolution in rocks during testing, providing a viable and insightful approach for investigating the dynamic damage failure process of rocks under coupled thermo-mechanical conditions.

Theory and method

PFC principle

The fundamental theory underlying the PFC was initially proposed by P.A. Cundall, utilizing the discrete element method to simulate interactions between particles based on the force–displacement law and Newton’s second law32. By adjusting micro-mechanical parameters of particles, the macroscopic physical behavior of materials can be effectively modeled33.

In PFC, inter-particle forces are generated through contacts. According to the force–displacement law, the contact force \({F}_{m}\) between two particles is calculated as follows when overlap occurs34 :

where \({F}_{m}^{n}\) and \({F}_{m}^{s}\) are the normal and tangential components of the contact force, respectively; \({K}^{n}\) is the normal stiffness; \({U}^{n}\) is the normal relative displacement; \({k}^{s}\) is the tangential stiffness; and \(\Delta {U}^{s}\) is the tangential relative displacement.

The force–displacement law facilitates the computation of forces acting on all particles. Combined with Newton’s second law, particle displacement and acceleration can be derived32. The motion of particles, including translational and rotational behaviors, is governed by the following equations:

where \({F}_{i}\) is the unbalanced force on the particle at time t, m is the mass of the particle, \(\ddot{u}\) is the translational acceleration of the particle, \({M}_{i}\) is the unbalanced moment of force on the particle at time \({t}_{0}\), I is the rotational inertia of the particle, and \(\ddot{\theta }\) is the angular acceleration of the particle.

Within the PFC framework, heat propagation is idealized as occurring through a network of thermal pipes and reservoirs, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Consequently, the governing equation for conductive heat transfer is expressed as

where \({q}_{i}\) is the heat flux, \({q}_{v}\) is the heat source intensity, \(\rho\) is the density, \({C}_{v}\) is the specific heat capacity, and \(T\) is the temperature.

The continuum Fourier law defines the relationship between heat flux and temperature gradient as follows35:

where \({k}_{ij}\) is the thermal conductivity tensor.

Applying the macroscopic frameworks of the heat conduction equation and Fourier’s law to a discrete particle system requires defining a correspondence between continuum-level thermal properties and particle-scale parameters.

Assuming that the unit thermal resistance of a one-dimensional heat pipe p is \(\eta\), then its thermal power is:

where \({Q}^{\left(p\right)}\) is the heat output of the heat reservoir, \(\Delta T\) is the temperature difference between the two ends of the heat pipe, and \({l}^{\left(p\right)}\) is the length of the heat pipe.

In a heat pipe, there is a non-linear relationship between the thermal conductivity and the thermal resistance per unit length, as follows:

where k is the heat transfer coefficient, \(\phi\) is the porosity, \({V}^{\left({P}_{r}\right)}\) is the particle volume, \({N}_{pa}\) is the total number of particles, and \({N}_{p}\) is the number of activated heat pipes.

Thermo-mechanical coupling in PFC requires the simultaneous use of thermal and mechanical modules. When a thermal pipe is bonded, temperature changes induce additional normal contact forces between particles. The thermo-mechanical contact force components can be described as36

where \({F}^{n}\left(T\right)\) is the temperature-related normal force, \({F}_{m}^{n}\left(T\right)\) is the normal component of the temperature-related contact force, \(\Delta {F}_{t}^{n}\left(T\right)\) is the change in the temperature-related normal force component, \({K}^{n}\left(T\right)\) is the temperature-related normal contact stiffness, \({\overline{\alpha }}_{t}\) is the thermal expansion coefficient, \(\overline{L }\) is the effective length of the heat pipe, \(\Delta T\) is the temperature increment, \(\Delta {F}^{s}\left(T\right)\) is the temperature-related tangential force increment, \(\Delta {F}_{m}^{s}\left(T\right)\) is the temperature-related contact force increment tangential increment, and \(-{k}^{s}\left(T\right)\) is the temperature-related shear stiffness.

The effect of temperature variation on tangential forces is computed incrementally using a frictional sliding model:

where \({F}_{t}^{s}\left(T\right)\) and \({F}_{t+\Delta t}^{s}\left(T\right)\) are the tangential components of the temperature-dependent contact force at time t and \(t+\Delta t\) , respectively, \({F}_{t}^{n}\left(T\right)\) is the normal component of the temperature-dependent contact force at time t, \(\Delta {U}_{t}^{s}\) is the tangential increment of the contact displacement corresponding to the contact force at time t, \(\Delta t\) is a short time interval, and \(\mu\) is the coefficient of friction. Figure 2 shows a schematic diagram of the calculation process of the PFC program developed in this study.

Crack identification and classification criteria

In the study of crack dynamics using PFC, the model identifies and records cracks when parallel bonds fail. Bond failure is determined based on the Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion37. Specifically, when the normal tensile stress in the bond exceeds or equals the tensile strength,

where σn is normal tensile stress, and σt is normal strength. The parallel bond undergoes tensile failure.

When the tangential shear stress in the bond satisfy the following equation,

where τ is tangential shear stress, μ is coefficient of friction, and c is cohesion. The parallel bond undergoes shear failure.

In PFC, the classification of crack types is automatically determined at the moment of bonding failure32. When the bond experiences tensile failure, the crack is classified as a tensile crack. In the case of shear failure, two scenarios are considered. If the shear force at the time of failure is smaller than the cohesive force of the bonding particles, it suggests that the failure may have occurred under low normal stress conditions, characterizing it as a tensile-shear mixed-mode failure. Conversely, if the shear force during failure is greater than or equal to the cohesive force of the bonding particles, the failure is classified as a compression-shear failure, which is typically observed under higher normal compressive stresses, and is predominantly governed by high shear stresses.

Model construction

Method verification

To ensure the applicability of the PFC particle flow method for mechanical and thermal calculations of rock, its suitability was verified through uniaxial compression, heat transfer and thermo-mechanical coupling simulations, respectively.

Mechanical verification

We developed a rock particle model and performed uniaxial compression simulations, as shown in Fig. 3a. The dimension in the PFC model is 50 mm × 100 mm. The parallel bond contact model was applied to represent particle interactions, effectively capturing the key physical and mechanical properties of the rock material. By adjusting the contact parameters, we ensured that the mechanical behavior aligned with real-world conditions. A detailed list of the parameters is referred from Fan et al.38 and can be found in Table 1.

The model contains 7753 particles, with loading applied under strain control through the top and bottom walls at a strain rate of 0.5 s⁻1. Stress–strain curves obtained after rock failure were compared with experimental results38, as shown in Fig. 3b. The experimental and simulated curves exhibit similar trends and close agreement, demonstrating that the PFC method can effectively capture rock mechanical behavior. Discrepancies between the two curves may be due to the PFC rigid particle model which does not consider the inherent heterogeneity of the actual rock, leading to the slight overpredictions by the PFC method.

Thermal verification

A numerical heat transfer model was established to assess the efficacy of PFC in simulating conductive heat transfer within rock media. This model comprised a rectangular assembly of 400 spherical particles, illustrated in Fig. 4a. Model parameters were calibrated based on typical thermophysical properties of rock39, including a particle density ρ of 2850 kg/m3, thermal conductivity k of 3.5 W/(m·K), and specific heat capacity C of 1015 J/(kg·K). Constant temperature boundary conditions were applied, setting the leftmost particles to 100 °C and the rightmost particles to 0 °C, whereas the initial temperature for all particles within the specimen was uniformly defined as 0 °C. Heat transfer computations were executed under these prescribed conditions until the system reached a state of thermal equilibrium.

For validation purposes, the thermal response of particles located along the bottom row of the model was selected for comparative analysis. Temperatures obtained from the PFC simulation for these particles were compared against the theoretical predictions derived from classical heat conduction theory. The governing equation for heat conduction is expressed as40:

where T denotes temperature, t represents time, \(\kappa\) is the thermal diffusivity, and x is the spatial coordinate.

A comparison between the PFC simulation results and the analytical solution is presented in Fig. 4b, utilizing normalized values for both particle position (horizontal axis) and temperature (vertical axis). At durations of 600 s and 1200 s, heat penetration remained limited, inducing noticeable temperature changes predominantly in the vicinity of the leftmost (heated) particles. Upon reaching overall thermal equilibrium, the temperature distribution within the model transitioned to a linear profile, indicating a uniform steady-state gradient. The close alignment between the PFC results and the theoretical solution confirms that the PFC thermal model provides a reasonable approximation of the thermal response in rocks.

Thermo-mechanical coupling verification

Our thermo-mechanical coupling model is validated according to Zhao41 and Qiu et al.42. As shown in Fig. 5a, the model dimensions are 76 mm × 38 mm, consisting of four different mineral components: quartz, feldspar, plagioclase, and mica. A parallel bonding model is employed to describe the particle–particle contact, with particle radii ranging from 0.17 to 0.29 mm. The thermal expansion coefficients (α) of the different minerals are listed in the Table 241. The thermal conductivity (k) and specific heat capacity (C) are uniformly set to 3.5 W/(m·K) and 1015 J/(kg·K), respectively. To simulate real conditions, temperature is applied to the specimen by using the outermost particles as the heat source, as shown in Fig. 5b. The initial temperature of the specimen is set to 20 °C.

Mineral particles with a particle size range of 0.17 to 0.29 mm are generated using the volume fraction method to form the rock sample. After applying the temperature load, uniaxial compression testing is conducted by applying velocity to the top and bottom loading plates. The resulting peak uniaxial compressive strength is shown in Fig. 6. When compared with the results of Zhao41 and Qiu et al.42, the strength errors for the four temperature conditions are 0.12%, 4.45%, 4.88%, and 0.97%, respectively, and 3.05%, 5.69%, 9.73%, and 7.32%. The trend of peak strength variation obtained from the model is consistent with the research findings, which validates the rationality of the temperature loading method and the thermal coupling approach employed in this study.

It is worth noting that the temperature field and mechanical field are coupled sequentially in calculations. This approach has been widely used in the literature12,41 because of its high computational efficiency. Also, Gee and Gracie43 compared the fully coupled and sequential coupling methods for thermo-mechanical coupling models and pointed out that, when implemented with sufficiently strict iteration tolerances, the sequential coupling method can converge to the same solution as the fully coupled method, thereby producing results with comparable accuracy.

Model construction

Parameters

As an acidic igneous rock, granite predominantly consists of minerals including quartz, potassium feldspar, and mica. Its complex mineralogical composition contributes significantly to its heterogeneous nature. To incorporate this heterogeneity into the numerical model, a methodology following Wang et al.44 was adopted, assigning particles to seven distinct groups representing key mineral constituents: quartz, biotite, plagioclase, orthoclase, amphibole, pyroxene, and other minerals, based on their typical composition and properties. The proportional distribution of these minerals and their respective coefficients of thermal expansion, sourced from Fei45, are detailed in Table 3. The resulting PFC model of the rock is illustrated in Fig. 7, featuring a stochastic distribution of mineral types, thereby enhancing the representation of real granite’s heterogeneous characteristics.

Interactions between particles are governed by contact models. The PFC framework offers various contact models to simulate diverse material behaviors. The parallel bond model was selected here, as this model facilitates the transmission of both force and moment between particles, while still permitting sliding under certain conditions. This model is, in particular, well-suited for simulating bonded granular materials such as cement, rock, and similar geomaterials. The micro-mechanical parameters defining the contact behavior are provided in Table 4.

Thermal shock and dynamic load settings

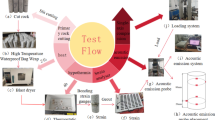

Geothermal reservoir temperatures typically range from 200 to 500°C. Moreover, temperatures exceeding 500 °C may induce complex mineral decomposition and other chemical reactions, such as the α-β quartz phase transition, which cannot be accurately modeled using current particle mechanics methods41. Therefore, this study does not account for the potential effects of mineral phase transitions and other chemical reactions on rock damage, and the maximum heating temperature is set at 500 °C. Consequently, five target heating temperatures were investigated: 200 °C, 250 °C, 350 °C, 450 °C and 500 °C, followed by cooling to a uniform temperature of 20 °C. Aligning with common experimental practice using muffle furnaces, a heating rate of 5 °C/min was implemented in the simulations. During heating, the rock surface experiences temperature changes prior to the interior. Accordingly, the outermost layer of particles in the model was designated as the thermal boundary, as illustrated in Fig. 8. To replicate the heat treatment process, specific thermal histories were imposed on the particles constituting this boundary. Initially, all particles were assigned a uniform temperature of 20 °C. Subsequently, the boundary particles were heated at the prescribed rate of 5 °C/min. Upon reaching the target temperature, an isothermal holding period of 2 h was enforced, succeeded by a rapid cooling (thermal shock) event using 20 °C water. Dynamic loading was applied subsequent to the completion of the cooling phase.

To facilitate loading and reduce computational load, a dynamic load application surface was established on the left side of the rock model using the PFC wall function, and Hopkinson bar approximate loading was performed. The loading setup is shown in Fig. 9a. Based on the stress equilibrium results of the Hopkinson bar test reported by Wang et al.44, a sinusoidal wave function for loading was adopted, with the peak incident load converted to 393,750 N. The dynamic load curve is shown in Fig. 9b. Four loading conditions were set: three low loading cycle counts of 1, 3, and 5; and one high loading cycle count of 50.

Analysis of results

Heat treatment temperature variation patterns

Throughout the thermal treatment, heat is progressively transferred from the external surfaces towards the interior of the numerical rock specimen. The evolution of temperature distribution within the rock model under the various target temperature conditions is illustrated in Fig. 10.

Analysis of Fig. 8 reveals that upon completion of the heating phase, the model’s surface attains the target temperature, whereas significant internal regions remain at substantially lower temperatures. The computed temperature gradients between the interior and exterior upon heating completion were 152.91 °C, 259.29 °C, and 329.09 °C for target temperatures of 200 °C, 350 °C, and 500 °C, respectively. This demonstrates a positive correlation between the target heating temperature and the resultant thermal gradient at the end of heating, with higher targets inducing more severe thermal contrasts. Following the 2-h isothermal holding period, a significant increase in the internal temperature of the model was observed. Consequently, the internal–external temperature differences reduced markedly to 17.71 °C, 36.78 °C, and 49.13 °C for the respective target temperatures, indicating a substantial mitigation of the thermal gradient compared to the immediate post-heating state. The temperature distribution within the model became more homogeneous, characterized by a diminished thermal gradient. Upon conclusion of the cooling phase, the model approached near-complete cooling, with only isolated central regions retaining slightly elevated temperatures. Residual internal–external temperature differences of 6.23 °C, 12.34 °C, and 19.95 °C were recorded for the initial target temperatures of 200 °C, 350 °C, and 500 °C, respectively. At this stage, the interior temperature marginally exceeded the surface temperature, with a maximum differential of 19.95 °C, signifying that the model had essentially reached a fully cooled state with a minimal remaining thermal gradient.

Thermal shock crack variation patterns

Differential thermal expansion among constituent minerals, induced by temperature variations, can lead to crack initiation within the rock. Figure 11 presents a comparison between the simulated and experimentally observed17 crack patterns subsequent to thermal shock. In the numerical results, crack distributions are denoted by colored segments: green for tensile cracks, red for tensile-shear cracks, and blue for compressive-shear cracks. Quantitative analysis of crack propagation is further supported by the statistics on crack numbers presented in Fig. 10.

Examination of Figs. 11 and 12 indicates that during the heating phase, crack initiation was minimal at target temperatures lower than 300 °C. A modest increase in crack count was observed at 500 °C, although the overall number remained comparatively low. The isothermal holding stage witnessed an increase in crack numbers relative to the heating phase, yet the counts persisted at relatively subdued levels. The most pronounced crack development occurred during the cooling stage, particularly under thermal treatments conditions of 350 °C, 450 °C, and 500 °C, where the number of generated cracks increased significantly and exhibited a positive correlation with the preceding target heating temperature, a trend consistent with experimental findings. This underscores that the cooling phase is predominant for thermal damage initiation in rocks under such conditions. The rapid cooling induces substantial thermal contraction in the previously expanded minerals. The mismatch in contraction magnitudes among different mineral types generates significant internal stresses, culminating in the formation of numerous microcracks. Furthermore, analysis of the failure modes reveals that damage was predominantly manifested as tensile and tensile-shear cracks, with compressive-shear cracks constituting only a minor fraction. This can be attributed to thermal stresses and the heterogeneous expansion of mineral grains, which collectively amplify the role of tensile mechanisms in rock failure. As a result, the tensile stress mechanism is identified as the primary cause of the rock damage observed under such thermo-mechanical conditions25,47.

Dynamic load crack variation patterns

The application of dynamic loading induces further damage and can lead to failure within the rock specimen. The extent of rock damage and failure was visualized using discrete fracture network representations. Figure 13 displays the state of damage and failure, including fracture distribution patterns, for rocks subjected to varying thermal shock temperatures and numbers of dynamic load cycles. Detached particle clusters visible in Fig. 13 represent fragments that have spalled off from the main rock body. Newly formed cracks within the rock model are indicated by colored segments (using the same scheme as Fig. 11). The quantitative relationship linking the number of cracks to both the heating temperature and the number of dynamic load cycles is graphically presented in Fig. 14.

Figures 13 and 14 collectively demonstrate a general trend of increasing crack numbers with higher thermal shock temperatures and greater numbers of dynamic load cycles. For temperatures ≤ 350 °C, the absolute number of cracks remained relatively low. Although a positive correlation with load cycle count was observed, the increase was gradual, suggesting that the extent of dynamic load-induced damage and failure was relatively moderate under these thermal conditions. At the elevated heating temperature of 500 °C, a more noticeable increase in crack count was evident, indicating enhanced rock damage. This was visually manifested in the model by the initiation of fragmentation and spalling. Overall, under a fixed thermal treatment temperature, the crack count generally increased with the number of dynamic loading cycles from 200 to 500°C. In addition, for a constant number of load cycles, the crack count nearly doubled as the heating temperature increased to 500 °C. Under high-cycle dynamic loading (50 cycles), the number of cracks increased sharply as the temperature rose from 350 to 500 °C, resulting in severe damage and failure of the rock. These results indicate that the severity of rock damage under dynamic loading is synergistically influenced by, and increases with, both the preceding heating target temperature and the number of applied dynamic load cycles. The slight non-monotonicity or partial decrease in crack numbers observed between 250 °C and 350 °C in some instances (Fig. 14) is likely attributable to the inherent stochasticity associated with the micro-mechanical contact properties defined in the model.

Discussion

The simulation results presented in Fig. 12 demonstrate a substantial increase in crack generation during the cooling phase compared to the heating phase, coupled with a positive correlation between crack quantity and thermal shock temperature. The propagation of micro cracks under 650 °C was further investigated and found to conform to this trend, as exemplified in Fig. 1544. This phenomenon is widely attributed to the development of more intense thermal stresses during cooling24. Microcracks initiated during heating may disrupt uniform heat conduction, leading to an irregular internal temperature distribution and an amplified thermal gradient upon cooling. Consequently, the actual thermal stresses experienced during cooling could surpass initial predictions. Furthermore, residual stresses likely accumulate within the rock by the end of the heating phase. The interaction between these residual stresses and the new thermal stresses generated during subsequent cooling contributes to the differential in overall stress magnitude and damage extent between the heating and cooling stages.

In practical underground energy engineering applications, such as geothermal energy extraction and underground mining, rocks are frequently subjected to thermal shock and dynamic loading, either independently or in combination16,48,49. Rocks in coal mining areas, for instance, often endure cyclic dynamic loading within a complex stress environment, making them highly susceptible to micro-crack initiation. As illustrated in Fig. 14, an escalation in the number of loading cycles induces a dramatic proliferation of cracks within the rock mass. The coalescence of these micro-cracks into macroscopic fractures ultimately compromises and jeopardizes the stability of the geological formation. Therefore, continuous monitoring of rock fracturing is crucial during mining operations. Conversely, in EGS, the inherently low permeability of HDR means that an increased crack network can significantly enhance heat extraction efficiency50. Figure 12 indicates that elevated thermal shock temperatures yield a greater number of cracks. Consequently, field engineering practices often prioritize reservoir zones with higher initial temperatures. Under such conditions, cracks are more prone to propagate, interconnect, and form complex fracture networks, thereby improving reservoir permeability. Furthermore, this study exclusively considered water as the cooling medium. The selection of the cooling medium itself can influence micro-crack generation. Zhang et al.51 compared water and supercritical CO₂ (SC-CO₂) as cooling media (Fig. 16a). We also compared the number of micro-cracks of Zhang et al.51 with that calculated in this study (Fig. 16b). The results in Fig. 16 all suggest that utilizing SC-CO₂ can induce a greater density of micro-cracks in the rock compared to water, potentially leading to superior heat extraction efficiency. This observation is consistent with the findings of Zhou et al.52, who, although not capturing the dynamic behavior of microcracks, indicated that increasing fracture network density improves thermal extraction efficiency when SC-CO₂ is used as the working fluid, as opposed to water. This aspect offers a promising avenue for further exploration in future work using the proposed PFC model.

This study employed DEM for numerical simulation, a technique particularly adept at modeling dynamic damage processes and nonlinear large deformations in rocks53. An inherent requirement of DEM models, however, is the calibration of particle-scale parameters, a process that can sometimes lead to significant discrepancies when compared to empirical measured data. Additionally, computational expense typically constrains DEM applications to relatively small-scale models. In contrast, the Finite Element Method (FEM), for instance, is highly effective for simulating large-scale mechanical problems54. Nevertheless, FEM encounters inherent challenges in simulating discrete crack propagation, often necessitating complex remeshing strategies that can lead to mesh distortion issues. Recognizing these complementary strengths and limitations, numerous studies55,56,57,58 have investigated coupled DEM-FEM approaches. Such hybrid methodologies aim to leverage the advantages of both techniques, enabling the simultaneous simulation of large-scale rock mass deformation and stress evolution while accurately capturing the intricacies of dynamic damage processes and crack propagation at a smaller scale. Therefore, future research could focus on integrating DEM and FEM to investigate the mechanical damage behavior of HDR under the coupled effects of thermal shock and dynamic loading. This integrated simulation framework holds promise for yielding more comprehensive insights.

Conclusion

The PFC model developed in this study visually illustrates crack propagation and damage evolution in rocks under thermal shock and dynamic loading. The conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

During thermal shock, when the rock reaches the target temperature, there is still a large temperature difference inside. After maintaining a constant temperature for 2 h, the temperature difference decreases, and at this point, the minerals inside the rock mainly undergo thermal expansion, resulting in fewer cracks.

-

(2)

The cooling stage of thermal shock is critical for rock damage. The number of cracks increases substantially during cooling, consistent with experimental observations. These cracks are primarily tensile and tensile-shear, indicating that tensile stress from temperature differences is the main driver of thermally induced damage.

-

(3)

Analysis of the dynamic load response shows that higher heating temperatures amplify damage under the same number of load cycles. With a large number of cycles (e.g., 50), fragmentation and spalling occur even at moderate temperatures (e.g., 350 °C), and the total crack number increases. This demonstrates that high temperatures combined with repeated dynamic loading significantly accelerate crack propagation and macroscopic damage.

Data availability

The datasets and materials used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bashir, A. et al. Comprehensive review of CO2 geological storage: Exploring principles, mechanisms, and prospects. Earth Sci. Rev. 249, 104672 (2024).

Abanades, J. C., Rubin, E. S., Mazzotti, M. & Herzog, H. J. On the climate change mitigation potential of CO2 conversion to fuels. Energy Environ. Sci. 10(12), 2491–2499 (2017).

Kuan, C. et al. Research status of geothermal energy detection technology in middle-deep depths in China. Prog. Geophys. 40(1), 54–69 (2025).

Wang, C., Qu, M. & Yu, H. Principle of Earth materials: A historical perspective of thermodynamics of the Earth. Bull. Geol. Sci. Technol. 43(04), 191–204 (2024).

Dong, L., Zhang, Y., Wang, L., Wang, L. & Zhang, S. Temperature dependence of mechanical properties and damage evolution of hot dry rocks under rapid cooling. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 16(2), 645–660 (2024).

Li, Q. et al. Coupling characteristics and stability evolution of ice-rich moraine soil slopes on the Tibetan Plateau under climate change. Bull. Geol. Sci. Technol. 44(01), 112–125 (2025).

Yao, M., Rong, G., Zhou, C. & Peng, J. Effects of thermal damage and confining pressure on the mechanical properties of coarse marble. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 49(6), 2043–2054 (2016).

Zhang, W., Shi, Z., Zhang, X., Wang, Y. & Wu, Y. Study on thermal crack characteristics of granite in Shandong Province, China under different temperatures and heating/cooling treatments. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 61, 105127 (2024).

Wu, Z., Zhang, D., Liang, Y., He, S., Xie, H. & Li, M. Mechanical and microstructural properties of Gonghe granite for enhanced geothermal systems: Thermal effects and energy evolution. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. (2025).

Li, D., Ma, J., Wan, Q., Zhu, Q. & Han, Z. Effect of thermal treatment on the fracture toughness and subcritical crack growth of granite in double-torsion test. Eng. Fract. Mech. 253, 107903 (2021).

Jin, Y. et al. Experimental and numerical simulation study on the evolution of mechanical properties of granite after thermal treatment. Comput. Geotech. 172, 106464 (2024).

Zhu, Y. et al. Numerical study of the influence of grain size and heterogeneity on thermal cracking and damage of granite. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 233, 212507 (2024).

Dang, Y., Yang, Z., Yang, S. & Liu, X. Thermal damage and crack propagation mechanisms of defective crystalline rocks: An experimental and numerical investigation. Theoret. Appl. Fract. Mech. 139, 105113 (2025).

Zhou, L., Zhao, Z., Duan, Z., Yang, J. & Jin, Y. Electromagnetic–thermal–mechanical–damage coupling simulation of rock under microwave irradiation based on the COMSOL–peridynamics method. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 58(9), 10295–10314 (2025).

Kim, K., Kemeny, J. & Nickerson, M. Effect of rapid thermal cooling on mechanical rock properties. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 47(6), 2005–2019 (2014).

Sha, S., Rong, G., Chen, Z., Li, B. & Zhang, Z. Experimental evaluation of physical and mechanical properties of geothermal reservoir rock after different cooling treatments. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 53(11), 4967–4991 (2020).

Yu, P., Pan, P.-Z., Feng, G., Wu, Z. & Zhao, S. Physico-mechanical properties of granite after cyclic thermal shock. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 12(4), 693–706 (2020).

Yu, L., Peng, H.-W., Zhang, Y. & Li, G.-W. Mechanical test of granite with multiple water–thermal cycles. Geotherm. Energy 9(1), 2 (2021).

Fan, L. F., Li, H., Xi, Y. & Wang, M. Effect of cyclic impact on the dynamic behavior of thermally shocked granite. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 57(7), 4473–4491 (2024).

Wang, P., Xu, J., Liu, S. & Wang, H. Dynamic mechanical properties and deterioration of red-sandstone subjected to repeated thermal shocks. Eng. Geol. 212, 44–52 (2016).

Han, G. et al. Effects of thermal shock due to rapid cooling on the mechanical properties of sandstone. Environ. Earth Sci. 78(5), 146 (2019).

Wu, X. et al. Damage analysis of high-temperature rocks subjected to LN2 thermal shock. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 52(8), 2585–2603 (2019).

Huang, Y. H., Yang, S. Q. & Bu, Y. S. Effect of thermal shock on the strength and fracture behavior of pre-flawed granite specimens under uniaxial compression. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 106, 102474 (2020).

Yang, Z., Tao, M., Fei, W., Yin, T. & Ranjith, P. G. Grain-based coupled thermo-mechanical modeling for stressed heterogeneous granite under thermal shock. Undergr. Space 20, 174–196 (2025).

Zhou, L. & Zhu, Z. A coupled thermo-mechanical peridynamic model for fracture behavior of granite subjected to heating and water-cooling processes. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 16(6), 2006–2018 (2024).

Wang, P., Wang, G., Wang, C. & Jiang, Y. Fracture mechanisms of granite subjected to varied thermal treatments: Insights into cooling-induced failure characteristics. Theoret. Appl. Fract. Mech. 138, 104942 (2025).

Wang, J. et al. Thermomechanical properties and fracture behavior of dry-hot granite subjected to cyclic thermal shock and dynamic tensile loading. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 192, 106165 (2025).

Pai, N. et al. An investigation on the deterioration of physical and mechanical properties of granite after cyclic thermal shock. Geothermics 97, 102252 (2021).

Wu, X. et al. Effect of water-cooling shock on mechanical behavior and damage responses of high-temperature granite in enhanced geothermal systems (EGS). Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 239, 212937 (2024).

Zhu, X., Lin, X. & Liu, W. Microscopic crack propagation and rock-breaking mechanism of heterogeneous granite under impact by special-shaped PDC cutters. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 247, 213716 (2025).

Huang, D., Hou, X., Wang, X., Li, W. & Rong, L. Experimental study on dynamic tensile mechanical properties of granite with different mineral compositions. Constr. Build. Mater. 491, 142785 (2025).

Cundall, P. A. & Strack, O. D. L. A discrete numerical model for granular assemblies. Géotechnique 29(1), 47–65 (1979).

Preh, A. & Poisel, R. 3D Modelling of Rock Mass Falls Using the Particle Flow Code PFC3D. na (2007).

Potyondy, D. O. & Cundall, P. A. A bonded-particle model for rock. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 41(8), 1329–1364 (2004).

Yan, C. & Zheng, H. A coupled thermo-mechanical model based on the combined finite-discrete element method for simulating thermal cracking of rock. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 91, 170–178 (2017).

Xia, M. Thermo-mechanical coupled particle model for rock. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 25(7), 2367–2379 (2015).

Kiyingi, W., Xiong, R., Jin, Y. & Guo, J. Geological carbon dioxide storage and subsurface rock mechanics—Geomechanical risks, modelling practices, and risk mitigation strategies. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 144, 103195 (2025).

Fan, X. et al. Numerical simulation of single-joint rock fracture evolution based on PFC. J. Tsinghua Univ. 64(07), 1238–1251 (2024).

Winkler E M. Physical Properties of Stone [M]//WINKLER E M. Stone in Architecture: Properties, Durability. 32–62 (Berlin, Heidelberg, Springer Berlin Heidelberg. 1997).

Tourchi, S. et al. A full-scale in situ heating test in Callovo-Oxfordian claystone: observations, analysis and interpretation. Comput. Geotech. 133, 104045 (2021).

Zhao, Z. Thermal influence on mechanical properties of granite: A microcracking perspective. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 49(3), 747–762 (2016).

Qiu, L., Xie, L., Qin, Y., Liu, X. & Yu, G. Study on strength characteristics of soft and hard rock masses based on thermal-mechanical coupling. Front. Phys. 10, 963434 (2022).

Gee, B. & Gracie, R. Comparison of fully-coupled and sequential solution methodologies for enhanced geothermal systems. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 373, 113554 (2021).

Wang, J., Dai, F., Liu, Y., Tan, H. & Zhou, P. Thermophysical-mechanical behaviors of hot dry granite subjected to thermal shock cycles and dynamic loadings. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. (2024).

Fei, Y. Thermal expansion. Mineral Phys. Crystallogr. 29–44 (1995).

Li, Z. & Rao, Q.-H. Quantitative determination of PFC3D microscopic parameters. J. Cent. South Univ. 28(3), 911–925 (2021).

Zhu, D., Jing, H., Yin, Q., Ding, S. & Zhang, J. Mechanical characteristics of granite after heating and water-cooling cycles. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 53(4), 2015–2025 (2020).

Yang, S.-Q., Ranjith, P. G., Jing, H. W., Tian, W. L. & Ju, Y. An experimental investigation on thermal damage and failure mechanical behavior of granite after exposure to different high temperature treatments. Geothermics 65, 180–197 (2017).

Xie, X., Hou, E., Zhao, B., Feng, D. & Hou, P. Investigating the damage characteristics of overburden and dynamic evolution mechanism of surface cracks in gently inclined multi-seam mining: A case study of Hongliu coal mine. Environ. Technol. Innov. 36, 103897 (2024).

Kumari, W. G. P., Ranjith, P. G., Perera, M. S. A., Chen, B. K. & Abdulagatov, I. M. Temperature-dependent mechanical behaviour of Australian Strathbogie granite with different cooling treatments. Eng. Geol. 229, 31–44 (2017).

Zhang, W. et al. Study on the cracking mechanism of hydraulic and supercritical CO2 fracturing in hot dry rock under thermal stress. Energy 221, 119886 (2021).

Zhou, L., Zhu, Z. & Xie, X. Performance analysis of enhanced geothermal system under thermo-hydro-mechanical coupling effect with different working fluids. J. Hydrol. 624, 129907 (2023).

Wang, F. et al. Grain-based discrete element modeling of thermo-mechanical response of granite under temperature. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 56(7), 5009–5027 (2023).

Habib, F., Sorelli, L. & Fafard, M. Full thermo-mechanical coupling using eXtended finite element method in quasi-transient crack propagation. Adv. Model. Simul. Eng. Sci. 5(1), 18 (2018).

Liu, H. et al. Mesoscopic numerical modeling of soil-rock mixtures: Investigation of mechanical behavior and failure mechanisms based on FDEM. Comput. Geotech. 186, 107455 (2025).

Liu, P. et al. FDEM numerical study on the large deformation mechanism of layered rock mass tunnel under excavation-unloading disturbance. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 159, 106497 (2025).

Han, H. et al. Modelling dynamic fracture and fragmentation of rocks under multiaxial coupled static and dynamic loads with a parallelised 3D FDEM. Comput. Geotech. 172, 106483 (2024).

Min, G., Fukuda, D., Oh, S. & Cho, S. Investigation of the dynamic tensile fracture process of rocks associated with spalling using 3-D FDEM. Comput. Geotech. 164, 105825 (2023).

Funding

This research was supported by Jiangsu Funding Program for Excellent Postdoctoral Talent (No. 2025ZB669).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Longshan Su actively contributed to the study by participating in the study design and article writing. Hongyu Li and Qifu Chi played an important role in the study by numerical analysis and data collection. Xin yang and Xuecheng Gao provided assistance in therms of data review and analysis, and article writing. Xu Huang significantly contributed to the research through study design and paper revision. It is important to note that all authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Su, L., Li, H., Chi, Q. et al. Dynamic damage and crack propagation of granite under thermal shock: DEM modeling insights. Sci Rep 16, 4054 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34104-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34104-1