Abstract

Understanding the mechanisms underlying the successful invasion of the guppy, Poecilia reticulata, a globally invasive species, is important in the field of invasion biology. The body color pattern of male guppies is known to influence predation risk; however, the relationship between body color pattern and local predator guilds has been addressed in only a few studies. To investigate this relationship, we analyzed 32 water samples and 305 male guppies from eight introduced populations on the main island of Okinawa, Japan. The environmental DNA metabarcoding analysis of teleosts from the waters identified six potential guppy predator families, Anguillidae, Eleotridae, Gobiidae, Cichlidae, Mugilidae, and Cyprinidae; however, there was no detection of Characiformes, which are one of the major predators of guppies in their original habitat. Using imaging analysis of color spot areas of male guppies, we found that 16 of 18 potential predator × color combinations exhibited a statistically significant association between body color and the presence of predator families. For example, a negative association between orange spots and Anguillidae, and a positive association between blue-green spots and Cichlidae. These results suggest that the guppy in Okinawa was ecologically released from a major predator in its native habitat and adapted to the new environment through color pattern changes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The artificial introduction of organisms into non-native ranges can lead to biological invasion, which has been regarded as a major threat to biodiversity worldwide during the Anthropocene. In particular, the invasion of medium to large predators, such as mongooses, ferrets, sea lampreys, and Nile perch, which prey on native organisms, has attracted the attention of ecologists and conservation biologists, because it can lead to the extinction of prey1. Conversely, small omnivorous fish such as guppies and mosquitofish have also been purposefully introduced in many countries, primarily to control mosquitoes. This has led to their global spread from temperate to tropical regions, which also raises concerns about their potential impacts on native ecosystem functioning and biodiversity2.

The invasion success of alien species is influenced by biotic resistance, the ability of native communities to hinder or prevent invasion3. The characteristics of alien species, such as the width and flexibility of resource use or niches, genetic variation, and propagule pressure, also play a role in their invasion success. In the new habitat, alien species may become invasive owing to their release from natural enemies such as predators, competitors, parasites, and pathogens, which limit their distribution and population density to their original range (ecological release)4,5,6. In contrast, alien species may encounter new enemies that limit their spread in the new habitat7,8,9 or prevent their establishment completely3,10,11,12. The invasion and establishment of small fish, which occupy an intermediate trophic level in the food web, are associated with inherent traits or characteristics that protect them from natural enemies in the new habitat. Therefore, investigating the interaction of these small fish with the local biota of their new habitats is important for understanding the mechanisms of the distribution expansion of invasive species. Such studies also allow evaluation of how diverse alien species affect a wide range of introduced environments13,14,15,16,17.

The guppy, Poecilia reticulata, represents a remarkable case in ecology and evolution, particularly with respect to its broad distribution and trait flexibility. Native to South America, including Venezuela, Trinidad and Tobago, and northern Brazil, it has now been artificially introduced and established in more than 61 countries, including USA, Mexico, Hawaii, Palau, Brazil, Peru, Singapore, Thailand, Philippines, Japan, Italy, Spain, Kenya, South Africa and others spanning North America, Australia, Southeast Asia, East Asia, Southern Europe, and Africa (FishBase homepage www.fishbase.org)18. The invasive success of guppies has been linked to pre-adaptation, which has been analyzed from multiple perspectives, including behavioral traits19,20,21,22, tolerance to anthropogenic environments14,15,17, active interactions with other fish23,24, and genetic background16. The guppy is capable of forming populations from a few ancestral individuals25 and of evolving by utilizing genetic variation present in the founding population despite experiencing a bottleneck during introduction16. It is highly tolerant to polluted environments15,26 and reportedly possesses behavioral and cognitive traits that help to avoid predation19,20,22,27. These are inherent characteristics of the guppy that contribute to its ecological success in introduced habitats.

Furthermore, the guppy may have adapted to diverse habitats through the microevolution of its body color, which has been shown to confer a predation avoidance effect through camouflage or cryptic coloration28,29,30,31. Male guppies exhibit remarkable intraspecific body color polymorphism with highly variable ornamentation, consisting of yellow, orange, iridescent, silver, and black color spots of varying sizes. These ornamentations are sexually selected traits but are also conspicuous to predators in natural environments28. Consequently, selective pressure for predation avoidance favors less conspicuous coloration in predator-rich habitats28. In other words, male guppy coloration reflects a trade-off between sexual selection and natural selection through predation avoidance28. The rapid and flexible microevolution of body coloration may have contributed to predation avoidance in newly colonized habitats of introduced guppies. However, few studies have addressed the relationship between the body color patterns of male guppies and local predator guilds in introduced habitats15,32. Empirical investigations of this issue are often challenging in the wild, as local fish assemblages can be taxonomically rich and water conditions frequently turbid, making predator identification difficult.

In this study, we focused on the main island of Okinawa (hereafter Okinawa Island), Japan, where the guppy P. reticulata has been introduced and established for several decades. We conducted environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding analysis to comprehensively monitor fish fauna, including potential guppy predators. The guppy on Okinawa Island is considered to have been introduced approximately in the 1960s33. The guppy is invasive in Japan through expanding its distribution mainly in the central and southern parts of Okinawa Island by replacing the native Japanese rice fish Oryzias latipes and the mosquitofish Gambusia affinis, which were introduced earlier and had once become dominant (Fig. 1)13,33. Currently, guppies inhabit a variety of environments, from small rivers, lakes, and artificial ponds to tributaries of relatively large rivers. In these environments, a variety of predatory fish are present, including the giant mottled eel (Anguilla marmorata), carnivorous Gobiidae, and the introduced Cichlidae. Using Okinawa Island as a model system, we aimed to investigate the microevolution of guppy body color ornamentation and its relationship with predator fauna in their introduced habitats. In this study, we focused on eight representative sites in the central and southern parts of Okinawa Island, where guppies have been established (Fig. 1C). We sampled male guppies and analyzed their body color patterns. We then statistically analyzed the association of these patterns with the estimated local fauna of predatory fish using eDNA metabarcoding. This approach can help us understand how the introduced guppy interacts with native biota to establish itself.

Water and guppy sampling sites. (A) A map of Japan and the archipelago of Ryukyus. (B) A map partially covering the Ruykyus archipelago including Okinawa Island. (C) Sampling sites at the middle to southern area of Okinawa Island. River systems and ponds were shown by blue lines. The water and guppy sampling sites were indicated by reddish orange-edged white dots. IRN, OYM, CHB, SNB, URN, OPC, TMY, and NSZ indicate site names Iri-nuka, Oyama, Chibu, Senbaru, Uranishi, Okinawa Prefectural Plant Protection Center, Tomoyose, and Nishizaki, respectively. IRN is an independent small spring and is not connected to other river systems. The confluence of the downstream of URN and SNB is marine water and thus guppies do not migrate between these two sampling sites. Adobe Illustrator 2021 v25.2.1 was used to draw the figure based on map imagery. The map imagery was obtained from OpenStreetMap (https://www.openstreetmap.org/) licensed under the Open Data Commons Open Database License by the OpenStreetMap Foundation and the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 license (CC BY-SA 2.0).

Results

Guppy and environmental water sampling

To analyze the potential interaction between predator fish fauna and the body color ornamentation of male guppies on Okinawa Island, Japan, we collected 32 water samples and 305 male guppies (Table 1). Sampling was conducted at eight sites in the central to southern areas of Okinawa Island, which represent the main habitat of the guppy on this island (Fig. 1). In each site we sampled guppies four times from April to September, 2018, resulting in collecting 9.5 ± 0.2 (mean ± S.E.) male guppies per survey (Table 1). To analyze fish fauna including potential predators of the guppy, we filtered approximately 1,000 mL of environmental water of the guppy habitats on site at each sampling date, obtaining 32 samples of highly pure eDNA with the mean concentration of 46.8 ng/μL ± 5.0 with OD260/280 values of 1.93 ± 0.02. The detailed method of eDNA extraction using the Sterivex filter unit (Merck Millipore, Milan, Italy) and the DNeasy PowerWater Sterivex Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) is described in the Methods section.

Environmental DNA metabarcoding sequencing for fish and vertebrates

To estimate the potential predators of the guppy and their approximate abundance, we performed an eDNA metabarcoding analysis for vertebrates, including teleost fishes, from the 32 water samples obtained using the MiFish universal primers34, producing a total of 469,826 raw sequences using the MiSeq platform and the Nano flow cell (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Fhrom each sample, three PCRs were performed with different DNA polymerases and annealing temperatures (for details, see Methods) to detect more diverse species, generating 4,894.0 ± 303.2 reads per PCR. After quality-based data filtering (see Methods), 167,858 sequences (35.7%) remained at 1,748.5 ± 247.8 per PCR. Most of the filtered sequences were non-amplified trash sequences (203,254 reads, 43.3%) or had an insufficient sequence length (97,705 reads, 20.8%). The remaining 1,009 (0.2%) were sequences in which neither end of the primer was found.

As a result of taxonomic profiling analysis of the filtered sequences using the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Blast Plus program35, the NCBI nucleotide collection database (nt)36, and the MitoFish database37,38,39, we found 163,576 sequences as effective ones having Blast hit to vertebrate species with 1,703.9 ± 245.6 per PCR and 98.85% ± 0.013 sequence similarities. Among them, we found 28 freshwater teleosts, four marine teleosts, two reptilians, two avians, and seven mammalian operational taxonomic units (OTUs) composed of 160,827 (98.3%), 19 (0.01%), 496 (0.3%), 13 (0.01%), and 2,221 (1.36%) sequences, respectively (for the full list, see Supplementary Table S1). Sequences from marine teleosts, which may be sourced from human foods, waste, or aquariums, and those from terrestrial tetrapods were excluded from the present analysis. A total of 24 species of freshwater teleosts were identified by merging the three subdivided OTUs of Carassius auratus and Cyprinus carpio into one species because they were considered to be the same species (Table 2).

Of the 24 teleosts, 18 were identified as potential guppy predators (Table 2) using the following criterion. Based on feeding behavior and body size data from FishBase18, carnivorous and omnivorous species larger than 10 cm in adult size were considered possible predators, including five Cichlidae, three Eleotridae, three Gobiidae, two Mugilidae, two Cyprinidae, one Anguillidae, one Poeciliidae, and one Synbranchidae species (see Methods). Two other herbivorous species of Cichlidae and Loricariidae, three smaller species (<10 cm in adult size) of Poieciliidae, Gobiidae, Ambassidae, and guppies, were not included as potential guppy predators (Table 2). The eDNA sequence counts from three separate PCRs were corrected by considering the detection of a few to a few dozen sequences from the negative control and blank-index samples. From a total of six negative PCR control samples (twice for each PCR), teleost sequences were detected in three negative control samples: two sequences each of Oreochromis niloticus and C. auratus from one, two sequences of P. reticulata from another, and two sequences of O. niloticus from another. From a total of 64 index blank samples, teleost sequences were detected in six blank samples: 22 and 37 sequences of C. carpio from two blanks, four and five sequences of P. reticulata from other two blanks, 13 sequences of O. niloticus from one blank, and three O. aureus and six O. niloticus sequences from another blank (Supplementary Table S1). The sequences detected from negative and blank samples were thought to be derived from index-sequencing errors (index hopping), not experimental contamination, as these species were detected with relatively higher sequence counts. We subtracted the maximum sequence count of each species detected in these negative-control and/or blank-index samples from the whole sample data, and then the sequence counts from the three PCRs were summed for each sample. Based on this correction and aggregation, the number of detection sites and detection times for each teleost and family were summarized, showing at least four detection times for six potential predator families: Cichlidae, Eleotridae, Gobiidae, Mugilidae, Cyprinidae, and Anguillidae (Table 2). Based on the absolute number of eDNA sequences, Cichlidae was estimated to be the predominant fish group at five of eight sampling sites (SNB, URN, OPC, TMY, and NSZ), Gobiidae at two sampling sites (OYM and CHB), and Cyprinidae at one sampling site (IRN) (Table 4). Predator detection patterns differed by sampling sites (Fig. 2). At TMY and NSZ, four and five predator groups were repeatedly detected, respectively. At CHB, SNB, and URN, Cichlidae and Anguillidae, Cichlidae and Cyprinidae, and Cichlidae were repeatedly detected, respectively, being considered as main predators. At the other sampling sites IRN, OYM, and OPC, predators were not detected repeatedly (Fig. 2) Guppies were detected at all sampling sites 29 times in 32 surveys (90.6%).

Schematic representation of relative sequence read counts of teleost fish species detected. Columns indicate the sampling sites and water samples of four time points investigated in this study. IRN, OYM, CHB, SNB, URN, OPC, TMY, and NSZ indicate site names Iri-nuka, Oyama, Chibu, Senbaru, Uranishi, Okinawa Prefectural Plant Protection Center, Tomoyose, and Nishizaki, respectively. Rows indicate teleost species detected using eDNA analysis arranged by family and predation habit on guppies as summarized in Table 2. Matrices colored in magenta shading show relative sequence read counts normalized to logarithm of counts per million (cpm) reads for each sample. Raw sequence read counts were provided as Supplementary Table S1.

Correlation of population density and eDNA sequence counts of Cichlidae

We confirmed that the density of Cichlidae, which are potential predators of the guppy, was positively and significantly correlated with the detected eDNA sequence counts of Cichlidae. A visual survey of Cichlidae density was successful, as the water was relatively shallow (approximately 0.3 to 0.5 meters deep) and clear enough to see the bottom at the four sites, SNB, URN, TMY, and NSZ, for the three sampling dates, although species-level identification was not possible. This produced a mean density ranging from 0.23 to 10.04 Cichlidae per square meter (m2) (Table 3). Using this visually observed density as an explanatory variable, the eDNA sequence counts of the six species of Cichlidae (Table 2) were summed for each relevant sample and used as the response variable in the analysis of a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) with a Poisson error structure, obtaining a statistically significant positive correlation (eEstimate = 1.089, eStd Error = 1.003, z = 24.531, p <0.001). This model included sampling site and date as random effects and the total number of raw sequences of each sample as an offset parameter, supporting the approximate representation of eDNA sequence counts as abundance of the predator fish.

Association between potential predator presence and guppy male ornamentation

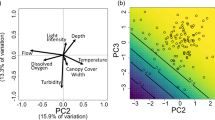

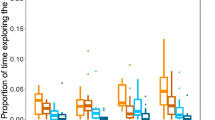

Likelihood-ratio tests comparing between GLMM models with and without sampling sites as the explanatory variable (see Methods) revealed that the ratio of three color areas (orange, black, and blue-green) of 305 male guppies were significantly different among sampling sites (orange: Chi-square = 155,113, d.f. = 7, p <0.001; black: Chi-square = 188,797, d.f. = 7, p <0.001; blue-Green: Chi-square = 780,951, d.f. = 7, p <0.001; Supplementary Fig. S1). Based on eDNA sequence detection of potential predator fish (Table 2; Supplementary Table S1) and color spot analysis of these guppy males (Table 1), we found that carnivorous and omnivorous predator candidates, that is Anguillidae, Eleotridae, Gobiidae, and Cichlidae, exhibited largely negative (suppressive) effects on guppy ornamentation, whereas omnivorous Mugilidae and Cyprinidae showed no or positive relationships (Fig. 3). Among these six predator families, which were detected for more than four time points and at least dozens of sequences (Table 2; Supplementary Table S1), Anguillidae, Gobiidae, and Cichlidae consistently showed significantly negative association with the sum of areas of black spots (hereafter, the black area) of the guppies (Fig. 3; GLMM; coefficients of logistic regression = –14.926 to –0.055, exponential coefficient (eCoef) = 0.000 to 0.947, Holm method-corrected p <0.05). The former two families also had negative correlations with the sum of areas of orange spots (the orange area, hereafter) (GLMM: coefficients of logistic regression = –23.346 to –0.121, eCoef = 0.000 to 0.886, Holm method-corrected p <0.05). Eleotridae showed a significantly negative effect on the sum of the areas of blue-green (iridescent) spots (hereafter, the blue-green area) (generalized linear model, GLM; coefficients of logistic regression = –0.507 to –0.180, eCoef = 0.602–0.835, Holm method-corrected p <0.05). In contrast, the effects of Mugilidae and Cyprinidae on the colored areas were largely statistically non-significant or inconsistent between the results from the presence/absence and absolute eDNA sequence counts (Fig. 3). The association of Cyprinidae with the orange area was the only one that was significantly and consistently positive, regardless of the sequence detection indicators (presence/absence or sequence counts) (GLMM: coefficients of logistic regression = 0.034–0.080, eCoef = 1.035–1.083, Holm method-corrected p <0.05). In the carnivorous Eleotridae, Gobiidae, and Cichlidae, the estimated effects on color spot areas were not consistent between the sequence detection indicators (presence/absence or sequence counts) for orange and black, blue-green, and orange and blue-green areas, respectively (Fig. 3).

Statistical evaluation of an association between detection of potential predators and ornamentation of guppy males. (A) Association scores between presence/absence or sequence count of each fish family and each color area of guppy males. Columns indicate six families detected as potential guppy predators and their ecological characteristics, including food habits and temporal niches. Rows indicate analyzed color spots and eDNA indicators, i.e., presence/absence and the absolute number of sequences. Each cell shows association scores: the scores before the slash symbol indicate the coefficient of logistic regression. Plus and minus scores indicate positive and negative associations, respectively. The scores after the slash indicate the exponential coefficient (eCoef) of the regression, where scores larger and lower than 1.0 indicate positive and negative associations, respectively. Significant negative and positive associations corrected for the significance level of multiple testing by the Holm method were shown by light-blue and pink shading, respectively. Gray shading shows absence of statistical significance. (B) Schematic illustration of color spot analysis of guppy males. Orange, blue-green (iridescent), and black color spots were measured as numbers of pixels by digital photographs taken at fixed distances between fish body and camera lens with a color reference card exemplified.

Discussion

In this study, we comprehensively analyzed fish fauna in multiple guppy habitats on Okinawa Island, Japan, using eDNA metabarcoding to address the ecology and evolution of the introduced guppy (Fig. 2; Table 2). We found that the fish fauna, including potential guppy predators on Okinawa, were largely similar to those on Trinidad Island at the order level (Table 4), which is one of the main native distributional ranges of the guppy. Among the known major predatory fishes of guppies in these native habitats, Anguilliformes, Cichliformes, and Gobiiformes31,47 have also been found in freshwater ecosystems on Okinawa Island. It is noteworthy that Characiformes fishes, which are one of the main predators of guppies in their original habitat, but are not naturally distributed in East Asia and Eurasia regions48, were not detected in the current survey in Okinawa. Six families of carnivorous to omnivorous characids are native to Trinidad Island (Table 4), including the fish-eating Erythrinidae (trophic level 3.77–4.02), such as Hoplias malabaricus, which preys on guppies31, whereas no characid was found in Okinawa in this study. In contrast, Cypriniformes (carp and crucian carp) and Perciformes (Ambassidae glassy fish) were found to compose the fish fauna of the guppy habitats in Okinawa, whereas they were not found in the Trinidad Island habitat (Table 4). Carps and crucian carps are detritivorous and planktivorous (Table 2) and are not thought to prey on guppies46. The Indian glassy fish Parambassis ranga is small (Table 2) and is not thought to prey on guppies. Taken together, these results suggest that the guppy populations on Okinawa Island have been ecologically released4,5,6 from Characiformes, which are one of the major predators in native habitats. In addition, the current dominance of the guppy in the studied habitats on Okinawa also suggests that biotic resistance3 by the local predatory fish fauna, if any, is not strong enough to prevent its invasion.

The association between the eDNA detection (“Presence” in Fig. 3) of potential predatory fish and the color spot areas of male guppies on Okinawa Island was statistically significant in 16 of 18 potential predator × color combinations (Fig. 3). Among the six fish families recorded more than four time points in the guppy habitats (Table 2; Fig. 2; Fig. 3), the spot area of male guppies showed a significant negative association with the presence of carnivorous groups in eight of the 12 potential predator × color combinations (Anguillidae, Eleotridae, Gobiidae, and Cichlidae) (Fig. 3). This relationship was observed in both diurnal and nocturnal predators, although it appeared weaker in the latter (Fig. 3). These findings support the ecological trade-off hypothesis whereby larger and more conspicuous male color spots enhance attractiveness to females, whereas smaller and less conspicuous spots increase survival under predation pressure49,50,51. However, the direction of the association varied depending on the color-predator family combination. For example, the blue-green spot was larger in the presence of Anguillidae, Cichlidae, and Cyprinidae, but smaller in the presence of Eleotridae, Gobiidae, and Mugilidae (Fig. 3). Furthermore, for omnivorous families (Mugilidae and Cyprinidae), the spot area of male guppies showed a positive association in four of the six fish-color combinations (Fig. 3).

These results suggest that the guppies introduced to Okinawa Island have developed adaptive male traits shaped by the balance between local sexual and natural selection pressures that they have experienced. Similar evolutionary responses of male guppies to predation regimes have been experimentally demonstrated in their native range in Trinidad Island28,49. In general, exotic species may face biotic resistance through interactions with local organisms3. The Okinawa guppy may have mitigated such pressures by adopting more cryptic body colors in response to local predatory fish.

However, the association patterns between fish eDNA data and color spots in male guppies observed in this study were complex (Fig. 3). Regarding Gobiidae vs. the blue-green area, Cichlidae vs. the orange and blue-green areas, and Cyprinidae vs. the blue-green and black areas, the direction of the correlation was reversed between the analyses using the presence/absence and those using the eDNA sequence counts of the predatory fish (Fig. 3). In all these cases, we confirmed that the relationship between the predator eDNA sequence counts and male guppy color spots was nonlinear. Notably, the presence of predators (the presence/absence of eDNA) and high abundance of predators (higher eDNA sequence counts) did not always exhibit correlations in the same direction with guppy color spot areas. This discrepancy can be attributed to the following factors. Food webs are flexible, and the predation pressure on guppies may change in a complicated manner depending on the densities of the predator and prey52,53: for example, due to intra-guild predation, competition, and/or shifts in food niches. Other environmental factors may affect color spots, such as the textures and color patterns of the background environments. The reddish-brown soil called “Shimajiri-maaji” and “Kunigami-maaji” are common in the riverbed of Okinawa. Structural colors are known to have cryptic optical effects under sunlight54. Therefore, future studies should examine how the green-blue spots of male guppies appear in the vision of predators on riverbeds under the intense Okinawan sunlight. Such optical effects might influence male conspicuousness to females, even in the absence of predators15,32,51. Furthermore, as seen in Anguillidae and Eleotridae, the association differed depending on the color spot type and predator combinations (Fig. 3). This may be attributed to the specificity of the color vision of the focal predator. It would also be important to elucidate how guppy body coloration and the presence of predatory fish are related to the underwater color environment estimated by such as the diffuse attenuation coefficient, Kd(λ)55,56,57.

This study suggests that the guppy introduced to Okinawa Island has adapted to new local environments through color pattern changes, despite the possible occurrence of a genetic bottleneck similar to the one introduced to Hawaii16. Guppies have attracted the attention of biologists because of their robustness against genetic bottlenecks, often forming healthy introduced populations25. Guppies can adapt to new environments by effectively utilizing the limited genetic variation present in the founding population16 through mechanisms such as rare male advantage or negative frequency-dependent sexual selection58. Furthermore, multiple introductions of guppies to Okinawa Island, as suggested by Shoji et al.50 may have provided additional genetic variation. On the other hand, male guppy color development exhibits ontogenetic plasticity in response to poor feeding conditions and high predation risk, leading to a reduction in color development rate before sexual maturity and a decrease in the final color area after sexual maturity59. It is important to note that the relationship between male guppy color area and predator community composition revealed in this study may be influenced not only by genetic responses to natural and sexual selection but also by ontogenetic plasticity. Future studies on Okinawan guppy populations should examine these possibilities in detail.

The present study has several technical limitations. First, the copy number of mtDNA used as a species marker gene in eDNA metabarcoding can vary depending on the animal species, tissues, and cell types60. Therefore, the eDNA sequence counts and abundance of the organism are not necessarily in complete proportion to each other, and some noise, including PCR bias, is included. Our analysis, focusing on Cichlidae (Table 3 and Results), showed that eDNA sequence counts for Cichlidae were significantly and positively correlated with visually assessed population density. This suggested that the eDNA sequence count of predatory fish roughly reflected their abundance; however, certain precautions are still necessary in quantitative analysis and interpretation using the eDNA sequence counts. In addition, eDNA detection of fish species, including potential guppy predators, indicates only their presence, and correlations between predator fish and guppies only indicate possible associations rather than confirmed interactions. To ascertain predator-prey relationships, direct observation of predatory behavior and controlled rearing experiments are essential. Furthermore, this study could not analyze yellow and silver spots among the five previously described guppy color spot types due to technical limitations, such as the low repeatability of area measurements. Future research should improve guppy color spot analysis by adopting advanced methods such as quantitative color pattern analysis (QCPA)51,61.

In summary, the guppy introduced into Okinawa Island established populations and dominated small rivers, ponds, and other freshwater environments13,33. Although Okinawan guppies have been ecologically released from the predator Characiformes, they may have encountered predator fish fauna similar to those in their native habitats. Although predatory fishes on Okinawa Island were likely to have influenced the color spot traits of male guppies to be cryptic, they did not provide strong enough biotic resistance to prevent guppy invasion. The eDNA approach provides useful information for understanding the ecology and evolution of introduced fish.

Methods

Sampling design and collection sites of guppies and environmental water

To analyze the relationship between the ornamental color patterns of male guppies and potential predator fishes, we chose eight sampling sites covering the middle to southern habitat area of the guppy on Okinawa main island (Fig. 1). At each site, we repeated the sampling of male guppies and environmental water four times from April to September 2018 (Table 1). On each sampling date, we conducted a visual survey of the local density of Cichlidae, which are representative guppy predators. Detailed methods of guppy and environmental water sampling, and density analysis of Cichlidae are described in the following subsections. The present study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) guidelines.

Collection of guppy males and quantification of ornamental color spot areas

On each date, 5 to 11 male guppies were collected using a portable landing net with a 770 cm2 and 2 mm mesh. We differentiated and picked up the males from the population based on the presence of gonopodium and color spots on the body trunk. The collection of guppies was carried out under regulations of the Ministry of the Environment, Government of Japan. The license number was not assigned to the current guppy sampling because guppies were not defined as specified alien species in Japan and the collection of them by academic staffs for research purposes was allowed without a license. They were transported to the university by car in plastic containers (15 × 10 × 10 cm; length × width × height). At the university, the containers with fish were subsequently kept in a dark room to prevent unexpected changes in color ornamentation due to the room light environment or stress until the fish were picturized. All photographs were taken within one week of collection in the following way. A male guppy was placed in a thin acrylic cage to move the left side of the body forward. The color image was captured using a digital single-lens reflex camera Canon Eos kiss X4 (Canon, Tokyo, Japan) and a 70 mm F2.8 EX DG MACRO MACRO lens (Sigma, Kanagawa, Japan) with a fixed distance between the camera and fish in the acrylic case. All methods using fish were carried out in accordance with guidelines and regulations of the Ichthyological Society of Japan. To minimize stress while taking photographs, fish were photographed without anesthesia in a small acrylic case filled with aquarium tank water. The experimental protocols using the guppy were approved by the Animal Experiments Committee of the University of the Ryukyus (Permission number: A2017108). This approval includes the experimenters’ license for handling guppies. The obtained image data were analyzed using Inkscape 0.92 (The Inkscape Project; inkscape.org) to quantify the ratio of the area of each color spot to the body area (number of pixels per total number of pixels of the body). An individual usually has multiple spots of the same color, and the sum of the ratios is defined as the colored area. The orange, black, and blue-green (iridescent) spots were traced manually using a pen tablet device (Wacom Intuos, Wacom, Saitama, Japan) and the spot area was estimated (Fig. 3). This tracing was conducted by a single researcher (Yuta S.). According to our preliminary analysis, yellow and silver spots appearing on the body side and tail were not included in the present study because these spots were less feasible to quantify and exhibited low repeatability. The total body area (number of pixels) of the left side of the guppy was estimated by tracing the body shape, excluding the dorsal and anal fins and orbital parts. All data from body color spot analysis and a summary statistics of collected guppy sizes for each sampling site are provided in Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Table S3, respectively. We did not adopt the R package patternize62 in our analysis because the automated analysis of this program could not distinguish between orange spot and base skin color of guppies, which exhibited relatively high variation among individuals.

Environmental water sampling

Water samples were collected manually using a clean plastic bucket and disposable gloves (Lavender Nitrile, Powder-Free Exam Glove, Kimberly-Clark Health Care, Roswell, GA, USA). Approximately 1,000 mL of the surface water of the river or ponds was filtered using a Sterivex filter with a 0.45 μm pore size membrane (Merck Millipore) and a 50 mL disposable syringe (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) until the filters were clogged by the filtrates. After filtration, the unit was tightly sealed using polypropylene Luer-fitting caps (ISIS, Osaka, Japan) and preserved in a cold reservation box with an ice pack for transportation to the university. These filter units were maintained at −30 °C until DNA extraction was carried out.

Population density estimation of Cichlidae

The population density of Cichlidae, which are representative predators of guppies, was estimated using a visual survey. Among the eight sampling sites, four sites where the existence of Cichlidae was visible were analyzed (referred to as SNB, URN, TMY, and NSZ in Fig. 1) from April to September 2018 on the same day and site of environmental water and male guppy sampling. Approximately 10 m2 of each site was set as a unit census tract (URN, 8.4m2; NSZ, 11.3m2; TMY, 14.0m2; SEN, 12.8m2) and living adult Cichlidae were counted visually using a tally counter five times per survey. The average number of individuals was used as population density (individuals/m2) (Table 3).

Environmental DNA extraction

Total eDNA was extracted from the water filtrates in the Sterivex unit using the DNeasy PowerWater Sterivex Kit (Qiagen). The standard manufacturer’s protocol was used with the following modifications. The Sterivex units were incubated at room temperature for 15 min to thaw the DNAiso reagent used for sample preservation. The reagent was then removed and discarded using a 10 mL disposable syringe (Becton, Dickinson and Company). After the addition of the MBL solution to the above kit, filter units were incubated at 65 °C on a heat block for 10 min to lyse the cells and other biomaterials in the filtered residues. At the final eDNA elution step, 20 µL of RNase-free water (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used, obtaining a total of 40 µL eDNA solution from each filter unit by the elution step twice. The eDNA was stored at −30 °C after quantification of its concentration (ng/μL) and quality (OD260/280) using a Nanodrop 2000c Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

PCR amplification and sequencing

From each eDNA sample, we amplified partial fragments of the mitochondrial (mt) 12S rRNA genes of various vertebrates, including teleost fish and tetrapods, to analyze the local fauna and potential predators of the guppy. The two-step tailed PCR was applied as previously described34 using the PCR primer named MiFish targeting vertebrate mt-12S rRNA. Each forward and reverse primer was combined with the priming region for second-round indexing PCR and DNA sequencing and random hexamer nucleotides for effective sequencing using a MiSeq platform (Illumina). The oligonucleotide sequences of these tailed primers have been described by previous study34. The typical target length (base pairs, bp) excluding the primer region of the MiFish PCR product, was 169 bp.

In the first step, two PCR enzyme systems were applied: HiFi HotStart ReadyMix (KAPA Biosystems, Wilmington, MA, USA) at an annealing temperature of 63 °C, and PrimeSTAR HS DNA polymerase (Takara) at two different annealing temperatures of 53 °C and 58 °C, separately. In each system, the final concentration of MiFish-U primers was set to 0.30 μM with 1.5 μL of template eDNA. Three PCRs, using each polymerase and annealing temperature, were performed for all samples. Using different types of polymerases and annealing settings with different fidelity is expected to amplify relatively more diverse DNA types than is possible when using only one of them, because of their different susceptibility to DNA sequences, particularly to secondary structures.

The HiFi HotStart ReadyMix (Kapa Biosystems) was used in a total reaction volume of 12.0 μL with the PCR condition as follows: 95 °C for 3 min followed by 35 cycles at 98 °C for 20 sec, 63 °C for 15 sec, and 72 °C for 15 sec, and finally at 72 °C for 5 min. The PrimeSTAR HS DNA polymerase (Takara) was used in a total reaction volume of 10.0 μL with the PCR conditions as follows: 94 °C for 3 min followed by 35 cycles at 98 °C for 10 sec, 53 °C or 58 °C for 15 sec, and 72 °C for 30 sec, and finally at 72 °C for 5 min. The first-round PCR products were diluted into RNase-free water (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 10-fold and subjected to a second-round indexing PCR. PCR was conducted by adding dual-index tags (D5, D7, A5, and A7 series) to identify sample origins and MiSeq flow cell-binding nucleotides (Illumina) as previously described63,64. The Ex Taq Hot Start Version (Takara) was used in a total reaction volume of 10.0 μL with 1.0 μL of the diluted first-round PCR products and 0.30 μM of tag-indexing primers with the PCR condition as follows: 98 °C for 30 sec followed by 12 cycles at 98 °C for 40 sec, 65 °C for 30 sec, and 72 °C for 30 sec, and finally at 72 °C for 5 min.

DNA sequences of the tag-indexed second-round PCR products were determined using MiSeq (Illumina). All PCR products with unique combinations of dual indices for each sample were pooled in equal amounts (2.5 μL) for semi-quantitative purposes. The pooled samples were purified using a 1.0% L03 agarose gel (Takara) and a MinElute Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen) according to a standard protocol. The eluted DNA solution was further purified and concentrated using AMPure XP magnetic beads (Beckman Coulter) by removing short DNA fragments (<100 bp) using a standard purification protocol. The obtained sequencing library was quantified using the Qubit 3.0 with the dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and finally, the 6 nM library was obtained by dilution using RNase-free water (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The volume molarity of the library was calculated based on the average molecular weight of a DNA nucleotide (660 g/mol), the DNA concentration, and the length of the second-round PCR products (approximately 365 bp). DNA sequencing was conducted using the MiSeq Reagent Kit v2 300 cycles (Illumina) for 151 bp paired-end sequencing. PhiX control v3 DNA (Illumina) and random shotgun DNA samples prepared using the Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina) were incorporated into the sequencer as spike-in DNA at 1% and 5% volumes, respectively.

Sequencing data analysis

The sequence data obtained using MiSeq were subjected to quality-based primary data processing. The 3’-tail nucleotides of each sequence with an error rate >10−1 were removed using the program DynamicTrim65. The tail-trimmed paired-end sequences were merged using FLASH software66 and processed by custom Perl scripts (available at Dryad data repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.54v2q)34to exclude sequences containing basecall failures (N bases) and having atypical length compared to the expected PCR target sizes described above. The filter-pass range of the sequence length before primer removal was 204–254 bp for vertebrate mt-12S rRNA. Primer sequences with a maximum five-base mismatch were removed using TagCleaner67. Sequences lacking primers at either end were discarded. Identical sequences within each sample were merged into a de-replicated sequence while keeping their count information using UCLUST (derep_fulllength command)68. The singleton sequences in each sample were aligned with ≥2 counts effective sequences at ≥99% sequence similarity to remove sequencing error and/or intra-species variations. The number of aligned singletons was added to the count information of the matched effective sequence, and unmapped singletons were discarded.

These quality-filtered effective sequences were analyzed to estimate their taxonomic origins based on sequence similarity to known reference sequences using the NCBI BLAST Plus program35. The NCBI nucleotide collection databases (nt)36 and MitoFish37,38,39 were used as reference databases. The Blastn-based species annotation according to the BLAST top-hit results was performed at the sequence similarity and e-value thresholds of 90% and 10−5, respectively. The sequence counts of the species from three separate PCRs with different DNA polymerases and annealing temperatures (the HiFi HotStart ReadyMix at 63 °C and PrimeSTAR HS DNA polymerase at 53 °C or 58 °C) were summed for each sample. The body size and ecological information of the detected teleosts, summarized in Table 2, were obtained from Fishbase18,40, Pongthana et al.41, WEB Fish Dictionary42, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) fish database43, Mexican Fish.com44, the Manko Waterbird and Wetland Center Web Site45, and Hosoya et al. (2019)46. The carnivorous and omnivorous teleost larger than 10 cm in adult size were considered possible predators of guppies based on the linear equation y = 0.291x−9.005, where y and x were prey and predator body sizes (mm)69. The guppy body size was set to 20 mm because most of the sampled guppy individuals (93.4%; 286/305) were less than 20 mm (Supplementary Table S2).

Statistical analysis

To evaluate the possible effect of potential guppy predators on the color spot sizes of male guppies, we performed the following statistical analyses. First, we constructed a GLMM with a Poisson error structure to confirm the association between eDNA sequence counts and population density (individuals/m2) of predator fish using data from Cichlidae (Table 3). The model included the Cichlidae density as the explanatory variable, the total Cichlidae sequence counts (genus Oreochromis and Amatitlania) from each relevant sample as the response variable, the sampling site and season as a random effect, and the total number of raw sequences from each sample as an offset.

Next, we investigated the effect of sampling sites on the relative spot area of orange, black, and blue-green (iridescent) of guppy males. We constructed two GLMMs with a binomial distribution as the error structure for each color analysis. One model included the sampling site as the explanatory variable, and the relative area (%) of each color spot (ratio of the number of color spot pixels to the total number of pixels of the body excluding the dorsal and anal fins and orbital parts) as the response variable, and the season as a random effect. The other model included the relative area of each color spot as the response variable, and the season as a random effect. To examine the significance of the effect of sampling site, we used likelihood-ratio tests to compare a model including sampling site as the explanatory variable, and season as random effects, to a model including only the random effect. The significance level was corrected using Holm’s method for multiple testing.

Finally, we analyzed the association between the total eDNA sequence count or presence/absence of eDNA of potential predator fish families and the relative spot area of orange, black, and blue-green (iridescent) of guppy males from each sampling site and date, as shown in Table 1. We constructed a GLMM or GLM with a binomial distribution as the error structure to assess this association. A GLMM was adopted for fish families detected in more than two sites, and a GLM was adopted for those detected at one site. Both models included the log 10-transformed total sequence counts or presence/absence of eDNA of each predator fish family as the explanatory variable, and the relative area of each color spot as the response variable. In the GLMM of fish families detected in more than two sites, the sampling site and season were set as random effects. The significance level was corrected using Holm’s method for multiple testing. Potential predator fish families that were detected less than twice were excluded from the association analysis. All statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.3.370.

Data availability

Raw sequence reads generated by MiSeq in the present study are available in the DDBJ Sequence Read Archive (DRA) for vertebrate metabarcoding data. BioProject accession number: PRJDB35691.

References

Simberloff, D. Invasive species: What everyone needs to know (Oxford University Press, 2013).

El-Sabaawi, R. W. et al. Biodiversity and ecosystem risks arising from using guppies to control mosquitoes. Biol. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2016.0590 (2016).

Zenni, R. D. & Nuñez, M. A. The elephant in the room: The role of failed invasions in understanding invasion biology. Oikos 122, 801–815 (2013).

Wolfe, L. M. Why alien invaders succeed: support for the escape-from-enemy hypothesis. Am. Nat. 160, 705–711 (2002).

Mitchell, C. E. & Power, A. G. Release of invasive plants from fungal and viral pathogens. Nature 421, 625–627 (2003).

Torchin, M. E., Lafferty, K. D., McKenzie, V. J. & Kuris, A. M. Introduced species and their missing parasites. Nature 421, 628–630 (2003).

Robinson, J. V. & Wellborn, G. A. Ecological resistance to the invasion of a freshwater clam Corbicula fluminea: Fish predation effects. Oecologia 77, 445–452 (1998).

Reusch, T. B. H. Native predators contribute to invasion resistance to the non-indigenous bivalve Musculista senhousia in southern California. USA. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 170, 159–168 (1998).

Byers, J. E. Physical habitat attribute mediates biotic resistance. Oecologia 130, 146–156 (2002).

DeRivera, C. E., Ruiz, G. M., Hines, A. H. & Jivoff, P. Biotic resistance to invasion: Native predator limits abundance and distribution of an introduced crab. Ecology 86, 3364–3376 (2005).

Freestone, A. L., Ruiz, G. M. & Torchin, M. E. Stronger biotic resistance in tropics relative to temperate zone: effects of predation on marine invasion dynamics. Ecology 94, 1370–1377 (2013).

Beaury, E. M., Finn, J. T., Corbin, J. D., Barr, V. & Bradley, B. A. Biotic resistance to invasion is ubiquitous across ecosystems of the United States. Ecol. Lett. 23, 476–482 (2020).

Tsurui-Sato, K. et al. Reproductive interference in live-bearing fish: the male guppy is a potential biological agent for eradicating invasive mosquitofish. Sci Rep https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-41858-y (2019).

Dias, M. S. et al. Historical distribution and current drivers of guppy occurrence in Brazil. J. Fish. Biol. 96, 877–885 (2020).

Gomes-Silva, G. et al. Water pollution affects fish community structure and alters evolutionary trajectories of invasive guppies (Poecilia reticulata). Sci. Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138912 (2020).

Rosenthal, W. C. et al. Invasion and rapid adaptation of guppies (Poecilia reticulata) across the Hawaiian Archipelago. Evol. Appl. 14, 1747–1761 (2021).

Bueno, M. L. et al. Ecosystem variables importance in the presence and abundance of a globally invasive fish. Sci. Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.162795 (2023).

Froese, R. & Pauly, D. FishBase 2000, concepts, design and data sources (eds. Froese, R. & Pauly, D.) (ICLARM Contrib. No.1594. International Center for Living Aquatic Resources Management (ICLARM)), (Laguna, Philippines, 2000).

Sievers, C. et al. Reasons for the invasive success of a guppy (Poecilia reticulata) population in Trinidad. PLoS One https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0038404 (2012).

Swaney, W. T., Cabrera-Álvarez, M. J. & Reader, S. M. Behavioural responses of feral and domestic guppies (Poecilia reticulata) to predators and their cues. Behav. Process. 118, 42–46 (2015).

Riesch, R. et al. Resource competition explains rare cannibalism in the wild in livebearing fishes. Ecol. Evol. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.8872 (2022).

Feyten, L. E. A., Ramnarine, I. W. & Brown, G. E. Microhabitat conditions drive uncertainty of risk and shape neophobic responses in Trinidadian guppies Poecilia reticulata. Ecol. Evol. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.10554 (2023).

Valero, A., Macías, G. C. & Magurran, A. E. Heterospecific harassment of native endangered fishes by invasive guppies in Mexico. Biol. Lett. 4(149), 152 (2008).

Fraser, D. F. & Lamphere, B. A. Experimental evaluation of predation as a facilitator of invasion success in a stream fish. Ecology 94, 640–649 (2013).

Deacon, A. E., Ramnarine, I. W. & Magurran, A. E. How reproductive ecology contributes to the spread of a globally invasive fish. PLoS One https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0024416 (2011).

Holitzki, T. M., MacKenzie, R. A., Wiegner, T. N. & McDermid, K. J. Differences in ecological structure, function, and native species abundance between native and invaded Hawaiian streams. Ecol. Appl. 23, 1367–1383 (2013).

Bassar, R. D., Lopez-Sepulcre, A., Reznick, D. N. & Travis, J. Experimental evidence for density-dependent regulation and selection on Trinidadian guppy life histories. Am. Nat. 181, 25–38 (2013).

Endler, J. A. Natural Selection on color patterns in Poecilia reticulata. Evolution 34, 76–91 (1980).

Endler, J. A. Variation in the appearance of guppy color patterns to guppies and their predators under different visual conditions. Vis. Res. 31, 587–608 (1991).

Endler, J. A. Multiple-trait coevolution and environmental gradients in guppies. Trend. Ecol. Evol. 10, 22–29 (1995).

Magurran, A. E. Evolutionary ecology: The trinidadian guppy (Oxford university press, 2005).

Martínez, C., Chavarría, C., Sharpe, D. M. & De León, L. F. Low predictability of colour polymorphism in introduced guppy (Poecilia reticulata) populations in Panama. PLoS One https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0148040 (2016).

Kochi, R. Medaka & Poeciliid fish in The Flora And Fauna Of Inland Waters In The Ryukyu Islands (eds. Nishida, M., Shikatani, N. & Syokita, S.) 492-495 (Tokai University Press, Kanagawa, 2003) (In Japanese).

Miya, M. et al. MiFish, a set of universal PCR primers for metabarcoding environmental DNA from fishes: Detection of more than 230 subtropical marine species. R. Soc. Open Sci. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.150088 (2015).

Camacho, C. et al. BLAST+: Architecture and applications. BMC Bioinform. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-10-421 (2009).

Sayers, E. W. Database resources of the national center for biotechnology information. Nucl. Acid. Res. 50, D20–D26 (2022).

Iwasaki, W. et al. MitoFish and MitoAnnotator: A mitochondrial genome database of fish with an accurate and automatic annotation pipeline. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2531–2540 (2013).

Sato, Y., Miya, M., Fukunaga, T., Sado, T. & Iwasaki, W. MitoFish and MiFish pipeline: a mitochondrial genome database of fish with an analysis pipeline for environmental DNA metabarcoding. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1553–1555 (2018).

Zhu, T., Sato, Y., Sado, T., Miya, M. & Iwasaki, W. MitoFish, MitoAnnotator, and MiFish Pipeline: updates in ten years. Mol. Biol. Evol. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msad035 (2023).

FishBase Consortium. FishBase. A global information system on fishes https://www.fishbase.se/ (2024).

Pongthana, N., Nguyen, N. H. & Ponzoni, R. W. Comparative performance of four red tilapia strains and their crosses in fresh-and saline water environments. Aquaculture 308, S109–S114 (2010).

Zukan.com Corporation. WEB fish dictionary https://zukan.com/fish/ (2024) (In Japanese).

The U.S. Geological survey. USGS science for a changing world: Fishes https://nas.er.usgs.gov/taxgroup/fish/default.aspx (2024).

Snow, J. Mexican Fish.com. Photographs And Species Information From Mexico https://mexican-fish.com/ (2024).

Manko waterbird and wetland center. The manko waterbird and wetland center web Site https://www.manko-mizudori.net/ (2024) (In Japanese).

Hosoya, K., Uchiyama, R., Fujita, T., Takeuchi, H. & Kawase, S. The Freshwater Fishes Of Japan (Yamato Keikoku Sha, Tokyo, 2019) (In Japanese).

Chang, C. H. Does predation pressure alter the visual properties of prey? An assessment of the guppy Poecilia reticulata. Ichthyol. Res. 72, 19–28 (2025).

Facey, D. E. et al. (eds) The Diversity of Fishes: Biology, Evolution and Ecology 3rd edn. (John Wiley & Sons, 2022).

Endlar, J. A. A predator’s view of animal color patterns in Evolutionary Biology, Volume 11 (eds. Hecht, M.K., Steere, W.C. & Wallace, B.) 319-364 (Springer, Boston, 1978).

Shoji, A., Yokoyama, J. & Kawata, M. Molecular phylogeny and genetic divergence of the introduced populations of Japanese guppies. Poecilia reticulata. Conserv. Genet. 8, 261–271 (2007).

Yong, L., Croft, D. P., Troscianko, J., Ramnarine, I. W. & Wilson, A. J. Sensory-based quantification of male colour patterns in Trinidadian guppies reveals no support for parallel phenotypic evolution in multivariate trait space. Mol. Ecol. 31, 1337–1357 (2021).

Kondoh, M. Foraging adaptation and the relationship between food-web complexity and stability. Science 299, 1388–1391 (2003).

van Velzen, E. et al. Flexibility in aquatic food web interactions: linking scales and approaches. Ecosystems 28, 23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-025-00968-7 (2025).

Kjernsmo, K. et al. Iridescence as camouflage. Curr. Biol. 30, 551–555 (2020).

Son, S. & Wang, M. Diffuse attenuation coefficient of the photosynthetically available radiation Kd(PAR) for global open ocean and coastal waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 159, 250–258 (2015).

Saad, J. F., Unrein, F., Tribelli, P. M., López, N. & Izaguirre, I. Influence of lake trophic conditions on the dominant mixotrophic algal assemblages. J. Plankton Res. 38, 818–829 (2016).

Rojo, J. H., Rodríguez, P. & Boy, C. C. Morphological differentiation in the widespread fish Galaxias maculatus: Do darker environments imply bigger eyes?. Hydrobiologia 847, 2863–2872 (2020).

Potter, T. et al. Female preference for rare males is maintained by indirect selection in Trinidadian guppies. Science 380, 309–312 (2023).

Ruell, E. W. et al. Fear, food and sexual ornamentation: Plasticity of colour development in Trinidadian guppies. Proc. R. Soc. B. 280, 20122019 (2013).

Garesse, R. & Vallejo, C. G. Animal mitochondrial biogenesis and function: A regulatory cross-talk between two genomes. Gene 263, 1–16 (2001).

van den Berg, C. P., Troscianko, J., Endler, J. A., Marshall, N. J. & Cheney, K. L. Quantitative colour pattern analysis (QCPA): A comprehensive framework for the analysis of colour patterns in nature. Method. Ecol. Evol. 11, 316–332 (2020).

Van Belleghem, S. M. et al. Patternize: An R package for quantifying colour pattern variation. Method. Ecol. Evol. 9, 390–398 (2018).

Sato, Y. et al. Inter-individual differences in the oral bacteriome are greater than intra-day fluctuations in individuals. PLoS One https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0131607 (2015).

Sato, Y. et al. Environmental DNA metabarcoding to detect pathogenic Leptospira and associated organisms in leptospirosis-endemic areas of Japan. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-42978-1 (2019).

Cox, M. P., Peterson, D. A. & Biggs, P. J. SolexaQA: At-a-glance quality assessment of Illumina second-generation sequencing data. BMC Bioinform. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-11-485 (2010).

Magoc, T. & Salzberg, S. L. FLASH: Fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatic 27, 2957–2963 (2011).

Schmieder, R., Lim, Y. W., Rohwer, F. & Edwards, R. TagCleaner: Identification and removal of tag sequences from genomic and metagenomic datasets. BMC Bioinform. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-11-341 (2010).

Edgar, R. C. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatic 26, 2460–2461 (2010).

Truemper, H. A. & Lauer, T. E. Gape limitation and piscine prey size-selection by yellow perch in the extreme southern area of Lake Michigan, with emphasis on two exotic prey items. J. Fish Biol. 66, 135–149 (2005).

R Foundation for Statistical Computing. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing https://www.r-project.org (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank N. Katsube and S. Fujimoto at the University of the Ryukyus for their assistance with fish sampling and rearing. This research was supported by the Center for Research Advancement and Collaboration and the Center for Strategic Research Project of the University of Ryukyus. Computations were partially performed on the NIG supercomputer at ROIS National Institute of Genetics.

Funding

This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research: Grant ID 26249024, 15H04425, 16H04846, and 17H01249 to K.T.; 17K19298, 20K12258, and 23K28279 to Yukuto S.; 19K12419 and 24K03131 to K.T.-S.; and 23K23965 to K.T., Yukuto S., and K.T.-S.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.T.-S, K.T., Yuta S., O.D., and Yukuto S. designed the study. Yuta, S., O.D., and K.T.-S. conducted fieldwork. Yuta S., K.T.-S., and Yukuto S. performed the DNA experiments, including DNA sequencing. Data analysis was performed by Yuta S., K.T.-S, and Yukuto S. K.T. and K.T.-S. supervised the whole process of the study. Yukuto S. and K.T.-S. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Yukuto S., K.T.-S., and K.T. revised the manuscript. All authors discussed the results, contributed to subsequent drafts of the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sato, Y., Sato, Y., Deki, O. et al. Estimated predator composition using environmental DNA analyses and color patterns of male guppies in introduced rivers. Sci Rep 16, 4066 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34186-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34186-x