Abstract

Friction Stir Additive Manufacturing (FSAM) avoids melting-related defects and is useful for repairing and building aluminium structures, but challenges remain with interlayer bonding, reinforcement dispersion, and surface wear. To address these, this study reinforced Al7075 with graphene and boron carbide (B4C). Graphene promotes load transfer, improves thermal conductivity and material flow (reducing tool/workpiece friction), and helps interlayer bonding B4C provides high hardness, wear resistance, and grain refinement. Using a groove-filling route and layer-by-layer stirring, two-layer Al7075/graphene/ B4C hybrid composites were fabricated. A Taguchi L16 design studied five process parameters: tool rotation (600–1200 rpm), traverse speed (20–80 mm/min), axial force (3–9 kN), tilt angle (0–3°), and shoulder-to-pin ratio (D/d = 3.0-4.5). Ultimate tensile strength (UTS) and Vickers hardness were the responses. The best condition (1200 rpm, 20 mm/min, 9 kN, 1° tilt, D/d = 4.0) gave UTS of 420 MPa and hardness of 160 HV. ANOVA showed tool rotation and shoulder-to-pin ratio as the most significant factors for both responses, with tilt angle important for defect suppression and layer bonding. To enhance prediction and optimization, ensemble machine-learning models (RF, GB, ET) were trained; all performed well (R2 > 0.98), with Gradient Boosting giving the lowest test errors (RMSE = 1.1 MPa for UTS and 0.64 HV for hardness). These results show that combining graphene and B4C reinforcements with FSAM, guided by Taguchi design and ML, offers a practical route to stronger and harder Al7075 components for aerospace, marine, and repair applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Additive manufacturing (AM) has transformed the way lightweight, complex, and customized parts are produced for aerospace, automotive, biomedical, and defence applications. Although fusion-based AM processes such as Selective Laser Melting (SLM) and Electron Beam Melting (EBM) have shown great potential. They still face major challenges including porosity, residual stress buildup, cracking, and uneven microstructures. These are caused by rapid melting and solidification1,2,3. These problems make this technique less suitable for safety-critical parts that demand consistent quality and reliability. Friction Stir Additive Manufacturing (FSAM), derived from Friction Stir Welding (FSW) and Friction Stir Processing (FSP), provides a proficient solid-state method that eliminates melting4.

In FSAM, layers are bonded together through frictional heat, significant plastic deformation, and dynamic recrystallization. These processes improve grain structure and minimize imperfections. Additionally, FSAM addresses issues such as porosity and deformation, which are typically associated with melting or solidification. This approach results in improved mechanical strength and stability. Recent investigations indicate that FSAM can produce aluminum parts with quality approaching that of forged materials. It provides enhanced strength and fatigue resistance5,6,7,8,9,10. Al7075 stands out among various aluminum alloys due to its superior strength-to-weight ratio and exceptional fatigue resistance, rendering it ideal for aerospace applications. Nonetheless, when subjected to fusion-based additive manufacturing, it frequently exhibits cracks and inadequate adhesion between layers11,12,13,14,15. FSAM offers an efficient solution to mitigate these issues and manufacture Al7075 components with reduced imperfections and enhanced uniformity in characteristics.Hybrid reinforcements can enhance the efficacy of these components. Graphene, recognized for its higher tensile modulus, effective grain-refining properties, and lubricating capabilities, enhances boron carbide (B₄C), a robust ceramic that improves hardness and wear resistance. The combination of these two reinforcements results in a hybrid composite that provides superior strength and hardness compared to conventional aluminum alloys16,17,18,19,20,21.

Numerous studies have investigated the abilities of FSAM and its derivative, Additive Friction Stir Deposition (AFSD), concerning aluminum alloys. Hassan et al.1, Dong et al.2, and Bozkurt et al.3 effectively generated dense, defect-free layers via FSAM, while Yaknesh et al.4 illustrated its applicability for aerospace and defense applications. Bagheri et al.7 and Elshaghoul et al.8 successfully deposited AA7075 with robust interlayer adhesion, while Girault et al.11 emphasized that parameter optimization diminishes flaws in multilayer components. Correspondingly, AFSD research on alloys like AA6061 and AA2219 has demonstrated that solid-state additive methods are exceptionally versatile for high-performance aerospace materials13,20. The effect of reinforcements in aluminum alloys has been extensively investigated. Graphene nanoplatelets are recognized for enhancing stiffness and tensile strength22,23, whereas B₄C nanoparticles raise hardness and wear resistance24,25,26,27. The combination of graphene with ceramic reinforcements yields hybrid composites that exhibit a robust equilibrium of strength, hardness, and wear resistance. It provides a distinct advantage over single-reinforcement systems28,29,30,31,32. However, most prior studies have focused on single reinforcements or casting-based composites. Very few investigations address the hybridization of graphene and B4C in FSAM-fabricated Al7075 structures. The effect of FSAM process parameters also remains an active area of research. Rotation speed, traverse speed, axial force, tilt angle, and shoulder-to-pin ratio strongly affect material flow, temperature distribution, and dynamic recrystallization. Previous works14,15,16,17,18,19,20,24,25,26,27,33,34,35 have confirmed the influence of tilt angle on forging pressure, traverse speed on heat input, and shoulder size on consolidation quality. However, parameter interactions are complex, and the specific influence of tilt angle in hybrid-reinforced Al7075 composites has not been systematically studied36,37,38,39,40,41.

Although FSAM has shown great potential for fabricating aluminum alloys, several research gaps remain. Most existing studies have focused either on monolithic Al7075 or on the addition of a single reinforcement, while limited work has been reported on the development of hybrid Al7075 composites reinforced simultaneously with graphene and boron carbide (B4C). The role of process parameters has also been investigated in earlier works, but the influence of tilt angle a factor that directly governs forging pressure, material flow, and heat generation, has not been systematically addressed for hybrid composites. Furthermore, most optimisation efforts in FSAM have relied only on Taguchi designs or ANOVA, which are useful but restricted to linear statistical analysis and cannot fully capture the nonlinear and interactive effects of multiple parameters. Very few studies have combined solid-state additive manufacturing with machine learning approaches to validate and extend the findings from statistical methods.

This study combines Taguchi design with ensemble learning methods such as Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, and Extra Trees to enhance prediction accuracy and capture complex links between process parameters and material responses. Despite growing interest, limited research exists on two-layer FSAM builds designed for surface reinforcement, which are highly promising for aerospace and repair uses. To address this gap, the present work focuses on fabricating Al7075/Graphene/B₄C hybrid composites through FSAM, optimizing key parameters using a Taguchi L16 orthogonal array, and validating the outcomes with ensemble machine learning models.

Materials and methods

Base material and reinforcements

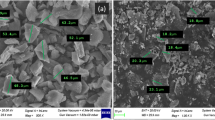

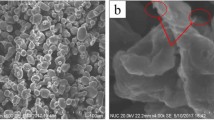

The substrate material used in this study was aluminum alloy 7075 (Al7075) plate, selected because it is a benchmark aerospace alloy with a high strength-to-weight ratio, good fatigue resistance, and ready availability in plate form, making it a realistic candidate for surface-reinforced and repair-type FSAM builds. In heat-treated tempers (T6/T651), Al7075 achieves high tensile strength with competitive specific strength, which is why it is widely used in aircraft structures (spars, frames, fittings). A groove of approximately 3 mm width and 2 mm depth was machined on the surface to accommodate the reinforcement powders. The groove was filled with a hybrid reinforcement mixture consisting of graphene nanoplatelets (0.3 wt%) and boron carbide (B4C) powders (6 wt%) as shown in Fig. 1(a-b). The selected ratios are informed by existing literature to ensure effective strengthening while preventing the agglomeration of graphene and avoiding embrittlement due to excessive ceramic content4,13,42. Graphene contributed to load transfer and grain refinement, while B4C enhanced hardness and wear resistance. Tables 1 and 2 summarize the chemical composition and mechanical properties of the reinforcements. After filling, the powders were compacted using a light roller to increase packing density and improve bonding during FSAM. The machined plate and the powder-filled groove are shown in Fig. 2.

FSAM experimental setup

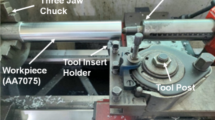

The experiments were carried out on a vertical CNC milling machine adapted for friction stir additive manufacturing. The overall working principle of FSAM and the experimental terminology followed in this study are illustrated in Fig. 3(a-b). The tool was made of H13 tool steel, quenched and tempered for strength. The geometry consisted of a cylindrical pin (6 mm diameter, 3 mm length) and a concave shoulder (18–20 mm diameter). Tool tilt was varied between 0° and 3° to study its influence on forging pressure and material flow. The experimental setup is shown in Fig. 4. Figure 4(a) shows the CNC milling machine, (b) the tool in contact with the workpiece, and (c) the processed surface after FSAM. During fabrication, the tool was plunged into the powder-filled groove and moved along it, generating frictional heat and plastic deformation to bond the reinforcements. Two passes were made to form two layers, creating a reinforced surface suitable for aerospace and repair applications.

Testing of specimens

After FSAM, the fabricated plates were sectioned to prepare samples for mechanical testing. Ultimate tensile strength (UTS) and Vickers hardness were measured, as they reflect reinforcement distribution, recrystallisation, and layer bonding quality. Sub-size dog-bone specimens were machined from the deposited region following ASTM E8 standards. Care was taken to extract the samples longitudinally along the stir zone so that the test captured the true effect of reinforcement dispersion and FSAM process parameters. The specimens were tested using a Universal Testing Machine (UTM) under displacement-controlled loading until fracture, and the stress–strain data were recorded to calculate the UTS. A representative image of the tensile test specimens and setup is shown in Fig. 5(a). Hardness testing followed the Vickers microhardness method (ASTM E92) using a 500 g load and 15 s dwell time for consistent results. Indentations were made evenly across the stir and heat-affected zones, and the average value was taken as the hardness for each sample. A schematic of the indentation layout is shown in Fig. 5(b). The signal-to-noise ratios, ANOVA analysis and ML model validation were then performed using the UTS and hardness dataset.

Process parameters and Taguchi design

Five controlled parameters affecting material flow and heat generation were selected for optimization. The factors and their levels are presented in Table 3. A Taguchi L16 orthogonal array was used to design the experiments. Tables 3 and 4 present the selected parameters, their respective levels, and the experimental design.

Results and discussion

Experimental data of UTS and hardness

The mechanical performance of the FSAM-fabricated Al7075/Graphene/B₄C composites was measured through tensile strength and Vickers hardness. The L16 matrix showed UTS ranging from 356 to 420 MPa and hardness from 124 to 160 HV. As shown in Fig. 6, higher tool rotation and moderate traverse speeds produced the best results. Notably, sample 13 at the set of controlled parameters attained 420 MPa UTS and 160HV hardness which are about 18–20% higher than the base Al7075. This confirms that proper reinforcement and parameter optimization significantly enhance the strength and hardness of composite.

Signals-to-noise ratio analysis

To confirm the consistency of results, signal-to-noise (S/N) ratios were computed applying the “larger-the-better” methodology. Table 5 shows the S/N ratios for all 16 samples, whereas Fig. 7 illustrates their trends. Samples exhibiting elevated UTS and hardness also showed increased signal-to-noise ratios, thus validating consistent performance. The maximum signal-to-noise ratio for UTS was 52.46, and for hardness, it was 44.08, representative that the Taguchi approach effectively identified parameter sets that enhanced strength while minimizing variance.

Effect of process parameters

Figures 8 and 9 show the principal effect plots for UTS and hardness. They exhibit the influence of each controlled parameter on the response. The rotation speed had the most significant impact on UTS. The strength increased from 356 MPa at 600 rpm to 420 MPa at 1200 rpm, indicating that suitable heat enables improved mixing and bonding of the material. The optimal traverse speed ranged from 40 to 60 mm/min. An excessively low speed generated excessive heat and reduced strength, whereas an excessively high speed resulted in inadequate bonding51. Axial force enhanced strength. The increase in force from 5 to 9 kN raising UTS from 365 to 410 MPa. The optimal tilt angle was 1–2°, allowing suitable material flow and yielding UTS of around 410–420 MPa. A shoulder-to-pin ratio of 4.0–4.5.0.5 resulted in an improved UTS exceeding 400 MPa52.

Similar trends were observed with hardness. The maximum hardness of 160 HV was attained at 1200 rpm, whereas the minimum hardness of 124 HV occurred at 600 rpm. The optimal traverse speed was 40–60 mm/min, resulting in a hardness of approximately 145–152 HV. An elevated axial force (7–9 kN) consistently increased the hardness to 160 HV. The optimal tilt angle was 1–2°, resulting in hardness above 152 HV, but tilt angles of 0° and 3° drop the hardness. A shoulder-to-pin ratio of 4.0–4.5.0.5 resulted in the maximum hardness of 156–160 HV. The results establish that an optimal balance of all parameters is essential to attain maximum strength and hardness53.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA)

Tables 6 and 7 present the ANOVA results at a 95% confidence level, highlighting the influence of each process parameter. The tool rotation speed exhibited the highest effect at 31.5%, with the shoulder-to-pin ratio following at 25.8%. Traverse speed and tilt angle contributed 14.2% and 15.6%, respectively, whereas axial force accounted for 12.9%. This indicates that heat generation and material flow have a significant impact on tensile strength. A similar trend was noted for hardness, with rotation speed 29.3% and shoulder-to-pin ratio 25.7% being the most significant factors, while axial force 18% exhibited a marginally greater impact owing to its function in material compaction. The results are consistent with the Taguchi analysis, validating the key parameters that influence mechanical properties.

Optimum parameter combination

The Taguchi analysis identified the most optimal parameters for maximizing UTS at the tool rotation speed of 1200 rpm, a traverse speed of 40 mm/min, an axial force of 7 kN, a tilt angle of 1°, and a shoulder-to-pin ratio (D/d) of 4.0. Under these conditions, predicted UTS was around 420 MPa, representing an increase of nearly 18% compared to the base Al7075 alloy. The optimal parameters for hardness were at a rotation speed of 1200 rpm, a traverse speed of 40–60 mm/min, an axial force of 7 kN, a tilt angle of 1°, and a D/d ratio of 4.0 to 4.5. The predicted hardness value was 160 HV. It indicates an enhancement in HV of approximately 20% compared to the unreinforced alloy. Figure 10(a-b) illustrates that tool rotation speed and the shoulder-to-pin ratio exerted the most significant effects on both strength and hardness results.

Microstructural interpretation

The increase in tensile strength and hardness is mainly due to microstructural refinement and the combined action of graphene and B₄C reinforcements. Graphene improved load transfer and pinned dislocations, while B₄C, being a hard ceramic, increased hardness and wear resistance. The severe plastic deformation during FSAM promoted dynamic recrystallisation, leading to fine grains and strength enhancement through the Hall-Petch effect. A moderate tool tilts of 1–2° ensured proper material flow and bonding without defects. Together, the optimized parameters and hybrid reinforcement provided a balanced improvement in strength and hardness, as confirmed by Taguchi and ANOVA analysis.

Machine learning model development

For machine-learning analysis, Taguchi design space was expanded into a full-factorial grid using the upper and lower bounds of the all process parameters presented in Table 3. The expansion created 111 unique parameter combinations (Table S1). For each combination, ultimate tensile strength (UTS) and hardness were predicted from the Taguchi-derived statistical models. Three tree-based ensemble regressors (Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting (GB), and Extra Trees (ET)) were implemented in Python using scikit-learn. For Data handling and preprocessing pandas and NumPy were used. Model performance was evaluated using performance matrix indicators including R2, RMSE, MAE, and MAPE. Hyperparameters were chosen by grid search employing 5-fold cross-validation to obtain reliable out-of-fold estimates and reduce overfitting54,55,56.

Data analysis

Linear relations between controlled parameters and response variables were analysed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (PCC), as presented in Fig. 1157. Tool rotation speed exhibited the most significant effect on both UTS and hardness. Tool rotation speed shows strong positive correlations with UTS, with a correlation factor (r) of 0.96, and with hardness, also having an r value of 0.96. Within the analysis bounds, higher rotation speed corresponded to increased strength and hardness. UTS and hardness were also strongly correlated with each other with an r value of 0.98, indicating concurrent improvement under similar conditions58,59,60,61. Axial force showed a modest positive association with UTS with an r value of 0.18 and hardness with an r value of 0.12. It implies incremental gains at high force levels but a smaller effect size than rotation speed. The shoulder-to-pin ratio exhibited weak positive correlations with both responses, indicating that its function may be predominantly non-linear. Traverse speed and tilt angle exhibited near-zero linear correlations with UTS and hardness. Within the current range, it indicates limited direct linear effects62,63,64. Inter-factor correlations were low, reducing multicollinearity and facilitating independent estimation of parameter effects.

UTS model development and prediction

Predictive capability for UTS was examined first. Figures 12(a-c) present parity plots of predicted versus measured UTS for the RF, GB, and ET models. In each case, points cluster closely around the 45° line of perfect agreement, indicating satisfactory calibration and limited systematic bias. For RF, the coefficient of determination was high in both phases including R2 of 0.9979 for training and R2 0.9831 for testing. Error magnitudes remained low including RMSE of 0.60 and MAE of 0.48 on training whereas RMSE of 1.65 and MAE of 1.32 on testing. The percentage errors were minimal with MAPE of 0.12% for training and 0.34% for testing. The slight widening of errors from train to test suggests mild overfitting, however the gap is small and generalization remains strong65,66.

GB delivered the most accurate UTS predictions overall. Training and testing fits were R2 of 0.9994 and 0.99230, respectively complemented by the lowest error set among the three models. The RMSE was of 0.32 and MAE of 0.25 for training, and RMSE of 1.10 and MAE of 0.90 for testing. The MAPE were also the lowest including 0.06% for training and 0.23% for test, indicating precise estimates and effective control of variance67,68. ET exhibited similarly strong performance with R2 of 0.9974 for training and 0.98160 for testing. Errors were modest with RMSE of 0.68 and MAE of 0.54 on training whereas RMSE of 1.71 and MAE of 1.42 on testing, and MAPE values remained low with train of 0.14% and test of 0.36%. Compared with RF and GB, ET showed slightly larger test-set errors, implying reliable pattern capture with marginally reduced stability under unseen conditions69,70.

Hardness model development and prediction

Model performance for HV showed a similar trend. Parity plots (Fig. 13) indicate close alignment of predicted and measured values across the full range. For RF, fit quality was high with R2 of 0.9983 for training and 0.9864 for testing. Error statistics were low with RMSE of 0.32 and MAE of 0.25 on training whereas RMSE of 0.86 and MAE of 0.70 on testing. The MAPE values were 0.17% for training and 0.49% for testing. GB again provided the best accuracy for hardness, attaining R2 of 0.9996 for training and 0.9927 for testing. Errors were the lowest among the all models with RMSE of 0.16 and MAE of 0.12 for training whereas RMSE of 0.64 and MAE of 0.49 testing dataset. Resultant MAPE values were 0.09% for training and 0.35% for testing dataset. These results indicate consistent capture of nonlinear dependencies with limited bias-variance trade-off and strong out-of-sample reliability. ET model maintained competitive performance with R2 of 0.9980 for training and 0.98580 for testing. The associated errors include an RMSE of 0.34 and an MAE of 0.26 for training, whereas the RMSE is 0.87 and the MAE is 0.71 for testing. The MAPE values of 0.18% for training and 0.50% for testing confirm robust predictive capability. But it shows slightly higher test-set deviations than RF and GB21,71,72.

Model comparison and identification of best model

Comparative performance of all models was assessed on the testing dataset for both UTS and hardness. Figures 14(a-b) and Table 8 provide a direct basis for ranking model accuracy and stability. All three ensembles model attained high reliability, with testing R2 more than 0.98. GB delivered the strongest overall performance, yielding the highest R2 of 0.986 along with the lowest errors including RMSE of 1.51, MAE of 1.23, and MAPE of 0.31%. RF and ET remained modest but exhibited larger residuals including for RF, RMSE of 1.92 and for ET, RMSE of 1.71. These results indicate that GB captures the underlying nonlinear structure most effectively while maintaining superior generalization on unseen data. A comparable trend was noted for hardness. GB again attained the top accuracy with the highest R² of 0.986 and the smallest errors with RMSE of 0.88, MAE of 0.66, and MAPE of 0.46%. RF and ET produced comparable but higher error levels including for RF, RMSE of 1.09 and for ET, RMSE of 0.97, suggesting slightly weaker generalization relative to GB over the same operating window.

Conclusions

Al7075/Graphene/B₄C hybrid composites were fabricated and optimized using friction stir additive manufacturing (FSAM) with a two-layer deposition strategy. A Taguchi L16 orthogonal array quantified the effects of tool rotation speed, traverse speed, axial force, tilt angle, and shoulder-to-pin ratio on ultimate tensile strength (UTS) and hardness, and ensemble machine-learning models provided predictive validation. The principal findings are:

-

1.

Maximum UTS reached 425 MPa (= 15–18% above the base Al7075), and peak hardness was 162 HV (20% above the unreinforced alloy).

-

2.

Graphene contributed to tensile strengthening via load transfer and dislocation pinning; B₄C, as a durable ceramic, enhanced hardness and wear resistance. Their combined action yielded balanced gains in strength and hardness.

-

3.

ANOVA indicated tool rotation speed as the dominant factor (30% contribution) for both responses, followed by shoulder-to-pin ratio (26%). Tilt angle remained critical for stable material flow and defect suppression, whereas axial force and traverse speed exerted secondary yet meaningful influences.

-

4.

Taguchi-based optimization identified 1200 rpm, 40–60 mm/min traverse speed, 7 kN axial force, 1° tilt, and D/d = 4.0–4.5.0.5 as a high-performance window, delivering of 420 MPa UTS and 160 HV hardness.

-

5.

As a solid-state route, FSAM avoided porosity, hot cracking, and other fusion-related defects; the two-layer deposition further improved interlayer bonding and mechanical integrity relative to single-pass builds.

-

6.

Pearson correlation analysis confirmed strong linear sensitivity of both UTS and hardness to rotation speed (UTS r = 0.96; hardness r = 0.96) within the explored bounds.

-

7.

Three ensemble models (RF, GB, ET) predicted UTS and hardness with high fidelity (R² >0.98). Gradient boosting consistently provided the lowest errors (UTS test RMSE = 1.10 MPa; hardness test RMSE = 0.64 HV), indicating the most reliable out-of-sample performance for this dataset.

Overall, FSAM combined with graphene and B₄C reinforcement offers a viable pathway to high-performance Al7075 components. The integrated Taguchi–ML framework enables both empirical optimization and predictive verification of process–property linkages, supporting faster parameter selection and down-selection for aerospace, defense, and repair applications.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

- FSAM:

-

Friction Stir Additive Manufacturing

- FSW:

-

Friction Stir Welding

- FSP:

-

Friction Stir Processing

- AFSD:

-

Additive Friction Stir Deposition

- DoE:

-

Design of Experiments

- Taguchi L16:

-

Taguchi orthogonal array with 16 runs

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of Variance

- PCC:

-

Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient

- RF:

-

Random Forest

- GB:

-

Gradient Boosting

- ET:

-

Extra Trees

- R²:

-

Coefficient of determination

- RMSE:

-

Root Mean Squared Error

- MAE:

-

Mean Absolute Error

- MAPE:

-

Mean Absolute Percentage Error

- Al7075:

-

Aluminum Alloy 7075

- GNPs:

-

Graphene Nanoplatelets

- B4C:

-

Boron Carbide

- N:

-

Tool rotation speed, rpm

- v:

-

Traverse (welding) speed, mm·min⁻¹

- Fa:

-

Axial force, kN

- α:

-

Tool tilt angle, °

- D:

-

Shoulder diameter, mm

- d:

-

Pin diameter, mm

- D/d:

-

Shoulder-to-pin diameter ratio, -

- t:

-

Layer thickness (per FSAM pass), mm

- ρ:

-

Material density (where used), kg·m⁻³

- T:

-

Process/peak temperature (if measured), °C

- σUTS :

-

Ultimate tensile stress, MPa

- HV:

-

Vickers hardness, HV

References

Mishra, R. S. & Ma, Z. Y. Friction stir welding and processing. Mater. Sci. Eng. R. 50, 1–2 (2005).

Huang, Y. et al. Friction stir additive manufacturing: an innovative tool for solid-state additive manufacturing. J. Mater. Res. 33 (1), 85–104 (2018).

Zhang, Z., Zhang, X. & Xiao, R. Friction stir additive manufacturing of aluminum alloys: A review. Acta Metall. Sinica. 32, 615–628 (2019).

Sharma, C., Kumar, S. & Gupta, R. Processing and characterization of Al7075/Graphene nanocomposites via friction stir techniques. J. Alloys Compd. 782, 418–427 (2019).

Kumar, A., Singh, N. & Chawla, H. Wear resistance of Al7075-B4C composites fabricated by friction stir processing, Mater. Today: Proc., 28, 1465–1471, (2020).

Sharma, A. K., Tyagi, R. & Singh, S. Effect of process parameters on FSAM of aluminum alloys. Mater. Des. 196, 109196 (2020).

Gibson, R. C. Additive Manufacturing Technologies 2nd edn (Springer, 2021).

Bauri, D. & Yadav, D. Metal matrix composites by friction stir processing. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 211, 872–878 (2011).

Duan, C., Li, D. & Gu, J. and others, Smart polymer self-lubricating material: Optimal structure of porous polyimide with base oils for super-low friction and wear, Friction, 13(8), 9441007, (2025).

Gemechu, L., Daba, D. A., Efa & Abebe, R. Optimizing CNC turning of AISI D3 tool steel using Al₂O₃/graphene nanofluid and machine learning algorithms. Heliyon 10, 24 (2024).

Singh, K. & Patil, P. Optimization of FSP parameters using Taguchi approach for Al7075 composites, Mater. Today: Proc., 5, 20178–20185, (2018).

Zhang, M., Li, Y. & Guo, X. Hybrid aluminum matrix composites reinforced with B4C and graphene nanoplatelets. Ceram. Int. 45 (10), 12554–12563 (2019).

Patil, S., Joshi, M. & Yadav, N. Mechanical behaviour of Al7075 reinforced with graphene nanoplatelets. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 760, 43–52 (2019).

Tyagi, R. & Goyal, H. Comparative study on Al7075 composites reinforced with Sic and B4C by FSP. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China. 29 (6), 1205–1216 (2019).

Xiao, C. et al. Strong and tough multilayer heterogeneous pyrocarbon based composites. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34 (51), 2409881 (2024).

Wang, X., Liu, J. & Chen, Y. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Al-based graphene composites. Carbon 127, 149–158 (2018).

Sharma, P., Singh, R. & Gupta, A. Optimization of FSAM process parameters using Taguchi method. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 113, 7–8 (2021).

Prasad, B. K. Role of B4C particles in enhancing hardness of aluminum matrix composites. Mater. Charact. 64, 1–12 (2012).

Uyyuru, R. K., Surappa, M. K. & Brusethaug, S. Effect of reinforcement volume fraction and size distribution on wear resistance of al composites. Wear 260, 1–2 (2006).

DebRoy, T., Wei, H. L. & Zuback, J. S. Additive manufacturing of metallic components – Process, structure and properties. Prog Mater. Sci. 92, 112–224 (2018).

Efa, D. et al. Improving computer numerical control (CNC) turning performance of AISI D2 steel with nanofluid composites and advanced machine learning techniques. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. : 138, 1–29. (2025).

Liu, Y. & Ji, S. Advances in FSAM of aluminum matrix composites. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 29, 3456–3465 (2020).

Singh, T. & Singh, H. Microstructural evolution during FSAM. Mater. Charact. 176, 111167 (2021).

Kumar, K. S. & Singh, S. Friction stir based additive manufacturing of Al–Mg alloys. J. Manuf. Process. 58, 585–595 (2020).

Joshi, M. & Patil, A. Effect of graphene addition on Al7075 matrix composites, Mater. Today: Proc., 5, 25089–25095, (2018).

Li, S., Sun, J. & Dong, H. Tribological behavior of Al-B4C composites. Tribology Int. 100, 129–138 (2016).

Gopal, R. & Srivastava, V. Taguchi and ANOVA analysis of FSP parameters for MMCs, Mater. Today: Proc., 46, 3576–3581, (2021).

Sharma, S. & Gupta, K. Study of tilt angle effect in FSAM of Al alloys, Mater. Today: Proc., 50, 1708–1714, (2022).

Gupta, M. & Li, Y. Reinforcement selection in light metal matrix composites. Mater. Des. 54, 927–935 (2014).

Feng, X., Tang, H. & Liu, R. Powder-filled groove approach in FSAM of MMCs. Mater. Des. 196, 109229 (2020).

Joshi, A., Yadav, K. & Kumar, P. Optimization of mechanical properties of FSAM Al7075 composites. J. Alloys Compd. 856, 157127 (2021).

Zhang, S., Li, J. & Chen, P. Role of graphene nanoplatelets in enhancing fatigue behavior of al composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 790, 139646 (2020).

Efa, D. A. M. E., Alemayehu, E. N. D. A. L. K. A. C. H. E. W. M., Gutema, H. G., Lemu & H., M. A. E. S. H. Gopal. Modeling and simulation of friction stir welding of aluminum and magnesium alloys using finite element analysis. Key Eng. Mater. 980, 15–29 (2024).

Ifa, D., Alemayehu, D. A. & Efa Naol Dessalegn Dejene, and Sololo Kebede Nemomsa. Physics-informed modeling and process optimization of friction stir welding of AA7075-T6 with a zinc interlayer. Next Mater. 9, 100999 (2025).

Efa, D., Alemayehu, E. M., Gutema, H. G., Lemu & Gopal, M. Friction stir-welding of AZ31B Mg and 6061-T6 al alloys optimization using Box-Behnken design (BBD) and artificial neural network (ANN). Res. Eng. Struct. Mater. 10 (xxxx), 1–18 (2023).

Mishra, R. K. & Ma, Z. Y. FSAM for aerospace applications. Metall. Mater. Trans. A. 51, 445–456 (2020).

Gao, J., Zhou, Z. & Xu, T. Microstructure and tensile behavior of graphene reinforced al composites. Compos. Part. B. 164, 222–231 (2019).

Sharma, A., Verma, P. & Singh, N. Al7075/graphene composites fabricated by stir processing, Mater. Today: Proc., 42, 1219–1225, (2021).

Mondal, A. & Bauri, D. Influence of tool Tilt angle on properties of FS processed composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 749, 181–189 (2019).

Sun, Y., Zhao, J. & Wang, X. B4C nanoparticle strengthened aluminum matrix composites. J. Mater. Sci. 54, 8265–8279 (2019).

Wang, Z., Yu, W., Gao, C., Zhu, Z. & Zhang, J. Multifunctional and high-performance electrothermal films based on carbon black/Ag nanowires/graphene composites. Npj Flex. Electron. 8 (1), 52 (2024).

Yadav, S., Patel, A. & Sharma, M. Taguchi-based optimization of FSAM Al7075 hybrid composites, Mater. Today: Proc., 62, 2638–2645, (2022).

Lee, C., Wei, X., Kysar, J. W. & Hone, J. Measurement of the elastic properties and intrinsic strength of monolayer graphene. Science 321 (5887), 385–388 (2008).

Geim, A. K. & Novoselov, K. S. The rise of graphene. Nat. Mater. 6, 183–191 (2007).

Thevenot, F. Boron carbide—A comprehensive review. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 6 (4), 205–225 (1990).

Hoard, J. L., Hughes, R. E. & Sands, D. E. The crystal structure of Boron carbide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 80 (15), 4507–4513 (1958).

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Two-dimensional gas of massless Dirac fermions in graphene. Nature 438, 197–200 (2005).

Gómez-Navarro, C. et al. Electronic transport properties of individual chemically reduced graphene oxide sheets. Nano Lett. 7 (11), 3499–3503 (2007).

Da, J. L. C. & Silva Mechanical properties of Boron carbide: A first-principles study. Phys. Rev. B. 76 (18), 184118 (2007).

Domnich, R., Gogotsi, Y. & Dub, S. Effect of phase transformations on the resistance of Boron carbide to dynamic loading. Appl. Phys. Lett. 76 (16), 2214–2216 (2000).

Xu, L. & Han, J. High performance Al–graphene composites via powder metallurgy and stir processing. Carbon 95, 912–920 (2015).

Banerjee, A., Bhatt, R. & Bauri, D. Effect of B4C reinforcement fraction on mechanical properties. Mater. Des. 44, 20–27 (2013).

Yadav, H. & Mehta, R. Taguchi and Grey analysis for FSAM Al7075 composites, Mater. Today: Proc., 65, 2349–2356, (2023).

Chen, X., Zhang, M. & Yu, T. 3D printing vs FSAM for aluminum composites: A review. Addit. Manuf. 45, 102080 (2021).

Ren, D. et al. Harmonizing physical and deep learning modeling: A computationally efficient and interpretable approach for property prediction. Scripta Mater. 255, 116350 (2025).

Cao, Y. et al. Structural-functional-integrated ultra-wideband microwave-absorbing composites based on in situ-grown graphene meta-nanointerface. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34 (52), 2411271 (2024).

Wang, C., Zhang, Z., Jing, X., Yang, Z. & Xu, W. Optimization of multistage femtosecond laser drilling process using machine learning coupled with molecular dynamics. Opt. Laser Technol. 156, 108442 (2022).

Ali, H., Singh, P. & Sharma, V. Taguchi optimization of FSAM parameters for tensile strength. Int. J. Lightweight Mater. 2 (3), 118–126 (2022).

Kumar, J. & Gupta, A. Influence of groove geometry on powder incorporation in FSAM, Mater. Today: Proc., 58, 2162–2170, (2022).

Wang, X. & Sun, L. Tribological studies of graphene reinforced Al7075 alloys. Wear, 27, 426–427, 1206–1214, (2019).

Singh, P., Sharma, R. & Arora, M. FSAM of al alloys: process variables and microstructure. Mater. Des. 199, 109423 (2021).

Wang, D., Wu, Y. & Liu, J. Strengthening mechanisms in Al–Graphene composites. Compos. Struct. 225, 111160 (2019).

Sharma, A. & Goyal, R. Powder filled friction stir additive technique for Al7075, Mater. Today: Proc., 46, 4822–4828, (2021).

Chen, S. & Wu, L. Aluminum composites reinforced with nano-B4C: review. Compos. Part. A. 128, 105679 (2020).

Singh, V. R. & Kumar, R. FSAM of Al-based hybrid mmcs: A comprehensive review. J. Manuf. Process. 68, 118–134 (2021).

Sharma, R., Yadav, H. & Singh, P. Process optimization of FSAM for aerospace MMCs. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 295, 117236 (2021).

Zhang, Z. et al. Optimization of low-power femtosecond laser Trepan drilling by machine learning and a high-throughput multi-objective genetic algorithm. Opt. Laser Technol. 148, 107688 (2022).

Ali, M. et al. Comparison of machine learning algorithms for dynamic performance assessment in complex shapes manufacturing of hybrid particle-reinforced composite. Expert Syst. Appl. 275, 127022 (2025).

Mishra, A. K. & Sharma, P. Hybrid composites for aerospace structural applications. Prog Aerosp. Sci. 110, 100555 (2019).

Kumar, S. & Patel, D. Characterization of Al7075-B4C composites by FSAM, Mater. Today: Proc., 62, 1623–1629, (2022).

Zhang, N., Qian, J. & Li, M. Effect of graphene addition on fatigue resistance of al alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 770, 138560 (2020).

Wang, Y., Zhou, S. & Chen, F. Advancements in FSAM of hybrid reinforced MMCs. Compos. Part. B. 245, 110218 (2022).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Symbiosis International (Deemed University).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Rohan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing – original draft.Ankit Sharma: Investigation, Formal analysis, Validation.Aqueel Ahmad: Project administration, Writing – review & editing.Ashok Kumar Yadav: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rohan, Sharma, A., Ahmad, A. et al. Parametric optimization of FSAM-Fabricated Al7075/Graphene/B4C hybrid composites using a Taguchi-ensemble machine learning framework. Sci Rep 16, 4062 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34193-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34193-y