Abstract

This paper presents a nine-level switched-capacitor (SC) based on ANPC inverter structure, where efficiency, compactness, and reliability are essential. Unlike conventional ANPC-based and previously reported SC topologies, the proposed structure suppresses the hard charging issue in SCs by inserting an inductor in the charging path, effectively reducing peak charging currents and associated switch stress. The inverter achieves natural self-starting and self-voltage-balancing of capacitors without additional circuitry, while requiring fewer active switches in the conduction path. These features lead to reduced component count, and minimized power losses. A peak efficiency of 96.9% is obtained at a rated power of 0.3 kW. Experimental verification confirms the theoretical predictions, demonstrating stable capacitor voltage under varying load conditions and modulation indices. Comparative analysis highlights the superiority of the proposed topology over existing SCMLIs in terms of efficiency, charging current suppression, and reduced component requirements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multilevel inverters (MLIs) are widely used in the development and integration of solar PV, fuel cells, electric vehicles (EVs), and uninterruptible power supplies (UPS)1. Compared with conventional two-level inverters, MLIs offer several advantages, including reduced dv/dt characteristics, improved efficiency, superior EMC, design flexibility, and high fault tolerance. However, achieving these benefits comes at the expense of increased circuit complexity. The requirement for multiple DC sources, switches, diodes, capacitors, and other passive components increases the size, cost, and voltage stress of the system2. Conventional FC-MLIs often suffer from capacitor voltage imbalance, to overcome this, balancing circuits, voltage and current sensors, are introduced3. Moreover, these topologies typically provide only half of the DC-link voltage at the output, which necessitates additional front-end DC–DC converters or transformers for boosting, further increasing complexity and reducing efficiency4

Switched-capacitor (SC) MLIs have been proposed to alleviate the aforementioned issues by integrating switched capacitors into the power circuit, the inverter can achieve boosting capability, natural capacitor voltage balancing, and reduced DC source5–7. For instance, nine-level SCMLIs have been reported in8, but the switches in these designs experience high voltage stress, increasing the overall cost. Similarly,9 presents a nine-level inverter but employs a large number of SCs and switching devices in the current loop, significantly lowering efficiency. The cascaded approach in10 generates higher voltage levels but relies on transformers, raising the overall cost. The topology in11 uses series charging of capacitors but suffers from voltage imbalance due to unequal impedance in the charging paths, degrading waveform quality over time. The structure in12 reduces voltage stress but requires 12 switches and 4 SCs, leading to higher losses. Similarly,13 reduces voltage stress but sacrifices efficiency, achieving only 92.8%. A notable ANPC-based nine-level SC inverter was proposed in14, which uses only nine switches, two diodes, and two SCs. However, one of the capacitors must be rated at double the DC-link voltage, which increases volume and cost. Another hybrid nine-level inverter reported in15 uses fewer switches but fails to address the hard charging of SCs, leaving switches exposed to high current spikes and high voltage ratings. The author in16 demonstrates a topology with quadruple voltage gain using fewer components, but the switches in the charging paths face severe current spikes, demanding high current ratings and raising cost. Likewise,17 proposes a single-stage nine-level topology with voltage gain, but it requires a large number of devices and an H-bridge for polarity reversal, increasing circuit complexity, stress, and cost.

To mitigate inrush currents in SCs, several soft-charging techniques have been introduced18–21. These include resonant and quasi-resonant charging approaches, which significantly reduce charging spikes and improve efficiency. However, they often depend on a higher number of capacitors, diodes, and inductors, which increase cost, complexity, and losses. For instance,18 uses seven switches, eight diodes, three SCs, and two inductors to generate only seven levels, making it inefficient in terms of component utilization. The quasi-resonant approaches in19 and20 reduce spikes but suffer from higher capacitor ripple and low efficiency. In21, a nine-level inverter is achieved with fewer devices, but scalability comes at the expense of additional SC cells, raising complexity. Other designs22,23 also use inductors to reduce inrush current but rely on isolated DC sources or large numbers of switches, again increasing size and cost.

Recent studies have proposed compact seven-level24–26 and nine-level27–29 SCMLIs. Although some of these designs achieve a reduced number of components, most still face challenges such as high switch voltage stress and severe current spikes during capacitor charging. In particular, the ANPC-based nine-level SCMLI in28 demonstrates an effective reduction in component count compared with earlier topologies but still suffers from several critical drawbacks:

-

The topology in28 employs two extra diodes in the charging loop compared to the proposed topology, increasing conduction losses.

-

Efficiency is limited at high load power due to additional conduction devices in the charging loop.

Building upon these limitations, this paper proposes a nine-level SCMLI based ANPC that overcomes the shortcomings of28. The primary contributions are as follows:

-

The configuration generates nine output levels from a single DC input with fewer semiconductor devices compared with28.

-

The configuration requires fewer devices in the conduction paths.

-

The devices in the proposed configuration experience lower TSV compared with28, reducing switch stress and enabling the use of lower-rated devices.

Proposed 9 level MLI topology

Brief description of the basic multilevel unit

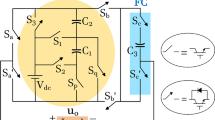

Figure 1 illustrates the configuration of the proposed switched capacitor-based 9-level inverter designed to generate a single-phase AC output. This topology employs a single DC input source (Vdc), 11 power switches (S1–S11) with antiparallel diodes, along with two DC-link capacitors (C1, C2) and two switching capacitors (CSC1 & CSC2) to achieve 9 distinct voltage levels. The DC-link capacitors, C1 and C2, function by dividing the input DC voltage into two equal parts, providing a midpoint connection that serves as the neutral point for the load. The switching capacitors, CSC1 and CSC2, are alternately charged by the input source and discharged through the load, facilitating the generation of the 9-level AC output waveform. A closer analysis shows that the proposed topology shares certain features with the approach reported in28. However, the proposed topology uses fewer components and experiences lower voltage stress.

To enhance the reliability of the capacitor charging process, a soft-charging inductor is incorporated into the circuit. This inductor effectively limits the inrush current during the charging of the switched capacitors (CSC1 & CSC2), thereby reducing current spikes and alleviating voltage stress across the semiconductor devices. The soft-charging inductor ensures smoother capacitor voltage buildup and minimizes switching losses. The direction of current flow during different switching states is visually indicated by red lines in Fig. 2. Additionally, the charging process of the switched capacitors is illustrated in green.

Description of output voltage states

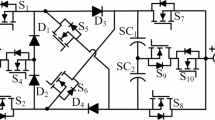

The output voltage levels generated by the proposed topology during the positive and negative half-cycles are shown in Fig. 2(a-l) and are described as follows:

-

State A (\({V}_{o}=0\) ): In this state, only three switches are activated to produce a zero voltage level, as shown in Fig. 2a. During this state, capacitors (CSC1 & CSC2) begins to charge.

-

State B (\({V}_{o}=0.25{V}_{dc}\) ): As depicted in Fig. 2b, capacitor (CSC2) continue charging, resulting in an output voltage of 0.25Vdc. In this state, the capacitor (CSC1) is bypassed.

-

State C \(( {V}_{o}={0.5V}_{dc}\) ): Illustrated in Fig. 2c, this state involves a configuration where capacitors (CSC1 & CSC2) continue charging. The current flows through switches \({{S}_{1}, S}_{3}\), and \({S}_{10}\). Simultaneously, \({S}_{6}\) and \({S}_{8}\) are turned on to charge the switched capacitors.

-

Sate D \(( {V}_{o}=0.75{V}_{dc}\) ): Achieved by following the current path through switches \({{S}_{1}, S}_{4}\), \({S}_{9}\) and \({S}_{10}\), as shown in Fig. 2(d). The capacitor (CSC1) starts discharging while capacitor (CSC2) do not undergo any charge or discharge cycle. The output voltage level in this state is 0.75Vdc.

-

State F \(({V}_{o}=1.0{V}_{dc}\) ): This is the final stage of the positive output staircase waveform, as seen in Fig. 2e. during this operating mode, the capacitors (CSC1 & CSC2) continue discharging. The output voltage can be obtained by following the path \({{S}_{1}, S}_{4}\), CSC1,\({S}_{8}\), CSC2 and \({S}_{10}\) to produce \(1.0{V}_{dc}\).

Similar analysis can be applied over negative half cycle of the output voltage. The switching pattern used to generate 9-level output voltage presented in Table 1.

Modulation scheme

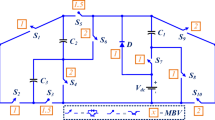

To eliminate the necessity for synchronization among multiple triangular signals and to minimize the computational complexity associated with multi-carrier modulation schemes, single carrier sinusoidal pulse width modulation (SC-SPWM) is implemented to generate gating signals by comparing sinusoidal modulating signal with a single triangular carrier signal. Figure 3 show the evolution of the comparison zone both on the positive and negative sides of the sinusoidal reference.

Sizing of passive components

Capacitor sizing calculation

To determine the capacitance values, the maximum discharging duration (LDT) of the capacitors within the period half-cycle is taken into account24.

To determine the required capacitance, the LDT must be considered. Capacitor CSC1 discharges during the interval from θ3 to (π − θ1), while capacitor CSC2 also discharges during the interval from θ1 to (π − θ2), as shown in Fig. 4. Hence, the capacitance of the switched capacitors calculated considering that + Vdc and − Vdc levels:

where ∆QSC represents the total charge supplied by switched capacitor during half-cycle, ∆Vr denotes the allowable voltage ripple, Req is equivalent parasitic load impedance.

Selection of current limiting inductor

The equivalent circuit representing the charging current loop is shown in Fig. 5. The equivalent source voltage (Veq), switched capacitor (CSC), and parasitic load impedance (Req). During the ON switching sequence, the charging current can be expressed mathematically as;

The circuit’s resonant time period (tr) and frequency (ωr) are determined by the following equation24:

Hence, The required \(L_{ch}\) can be determined by:

Therefore, the maximum charging current can be determined as follows:

where \(\phi = \tan^{ - 1} \left( {\frac{{2\omega_{s} L_{ch} }}{{R_{eq} }}} \right)\).

It can be seen clearly from Eq. (5), the maximum inductor current is inversely proportional to the inductance (Lch). In this study (Lch = 0.25mH) is selected to limit the charging current and provide smooth charging of switched capacitor.

Power loss and harmonic distortion analysis

Power loss analysis

The proposed configuration divides its total power losses into three groups: switching losses, conduction losses, and ripple voltage9. As a result, the total of these loss components is a full measure of the overall energy loss in the proposed inverter.

Conduction losses

The switch’s internal resistance causes conduction losses in a semiconductor switch. The load current that flows through the switch meets the parasitic elements in its path, which are the switch’s ON state resistance (Rs), the diode’s internal resistance (Rd), the forward voltage drops (Vd) of the diode, and the capacitor’s internal resistance (Rc).

To find the conduction losses, we first calculate the conduction losses of a standard power transistor and diode. Then we apply these calculations to the multilevel inverter context. We can calculate the instantaneous conduction losses of a transistor (pcd,SW (t)) and a diode (pcd,D (t)) like this:

where VSW and VD represent, respectively, on-state voltages of the semiconductor switch and diode while equivalent resistances of the semiconductor switch and diode are represented by RSW and RD.

The total conduction loss can be determined by

Switching losses

During the activation and deactivation phases of a semiconductor switch, switching losses occur. Throughout these processes, the switch experiences non-zero voltage and current levels, leading to the creation of switching losses in the semiconductor switch. We look at switching losses over the basic cycle. Upon completion of the turnoff period, denoted as tff, the voltage across the switches undergoes a linear climb to achieve Vsw. The turn-off loss of the switch can be calculated as follows:

where I is the current flowing through the switch before it turns OFF, Vsw,i is the off-state voltage on the switch, PL-off,i is the turn-off loss of the switch i, and toff is the turnoff time of the semiconductor switch.

Following the turn-on period, represented as ton, the voltage across the switches experiences a linear fall from Vsw to zero. The turn-on loss of the switch can be calculated as follows:

where PLon,i is the turn-on loss of the switch i, ton is the turn-on time of the switch, and I is the current through the switch after turning ON.

The average switching power loss can be written as follows:

where fo is the fundamental frequency, Nsw is the number of switches.

Ripple voltage losses

Another important power loss in SCMLIs is the percentage of voltage ripples in the capacitor (ΔVr). The ripple losses can be calculated by:

where PRP is the ripple losses, fsw represents the switching frequency, C is the capacitor’s capacitance, and ΔVr is the capacitor’s voltage ripples.

The overall efficiency can now be readily estimated subsequent to the determination of the aggregate power losses within the system, facilitated by the following equation.

The proposed inverter efficiency is further analyzed at different load conditions considering conduction losses, switching losses, and capacitor ripple losses using PLECS software as depicted in Fig. 6 (a). The efficiency achieved using PLECS software is relatively high 97.12% and 96.81% at an output power of 300W and 900W respectively when an inductor is used to provide soft-charging of switched capacitors. The distribution of losses in each capacitor and switch, including switching, ripple, and conduction losses, is given in Fig. 6 (b).

Total harmonic distortion (THD) analysis

To check the quality of the output voltage waveform, the THD is determined using this formula:

Here, V1 is the RMS value of the fundamental component of the output voltage, and Vh represents the RMS value of the hth harmonic component for h ≥ 2 h. This metric provides a quantitative measure of the distortion level in the output voltage waveform generated by the proposed switched-capacitor multilevel inverter.

The output AC voltage vo(t) of the proposed design has a total harmonic distortion (THD) that remain below 10% of the RMS value of its fundamental component. This makes sure that the inverter meets grid and power quality standards.

Results and discussion

This section analyses and discusses the simulation and experimental findings of the provided nine-level inverter.

Simulation results

The simulation outcomes of the proposed SC-MLI have been performed using PLECS software. A 300V magnitude source is employed to assess the inverter effectiveness. In generating gate pulses for the proposed inverter in this study, single carrier PWM is applied.

The steady-state waveforms for the output voltage (vo), output current (io), DC-link capacitor voltages (C1 & C2), and SCs voltages (CSC1 & CSC2), are depicted in Fig. 7. The voltage waveforms clearly demonstrate nine distinct levels with step voltage of 34V and the peak value of 300V, with the capacitor voltages balanced for entire fundamental period.

The waveforms of capacitor currents under hard charging and when introducing inductor to provide soft charging are illustrated in Fig. 8. Under hard charging, the peak currents ISC1max and ISC2max reach 68.35A at rated power. When an inductor is introduced in the charging path, the peak charging currents (ISC1max, ISC2max) reduced to 13.92A at rated power. This demonstrates that the use of an inductor reduces the charging currents by approximately 5 times, effectively mitigating current spikes during capacitor charging.

Figure 9 shows the performance of the proposed inverter under step variation in load demand. shows the waveforms of output voltage (vo), load current (io), supplied by the proposed topology and the voltages across the switched capacitors (CSC1 & CSC2) when load undergoes a step variation at time instant at t = 1.0s from (20Ω + 20mH) to (10Ω + 20mH). Due to sudden variation of R-L load, the proposed inverter is able to maintain ac output voltage without undergoing unwanted dip in voltage and the load current follows the corresponding transition. The ripple voltage of the SCs changes within 10% of its maximum value, which is acceptable. The waveform analysis reveals that the suggested inverter responds positively to variations in load. Figure 10 illustrates the variation in modulation index (ma) from values of (ma = 1.0 to ma = 0.5) and from (ma = 0.5 to ma = 0.2) respectively. It is observed that a reducing Ma leads to a slight reduction in the magnitude of both output voltage and current. Also, the inverter is able to maintain the voltage across SCs at various ma.

Experimental results

A test bench has been constructed to experimentally verify the performance of the different power electronic interfaces and the proposed inverter circuit. A laboratory prototype with a power capacity of 900W was developed, and experimental data were acquired under diverse load scenarios. Figure 11 illustrates the experimental arrangement of the proposed inverter. The DSP TMS320F28379 processor is utilized to implement the single carrier PWM, essential for generating gate pulses for the power semiconductor switches. The parameters of the proposed inverter are detailed in Table 2.

The waveforms of the output voltage (vo), load current (io), and voltage across the SCs (CSC1, CSC2) are shown in Fig. 12a when the proposed SC-MLI is powering (R-L) load. the operation of the proposed SC-MLI is validated by connecting it to constant R-L load at (20Ω + 20mH). Figure 12b depicts the equivalent waveforms of the SCs voltage and current. It can be observed that due to the use of soft-charging technique, the current on both SCs undergo smooth charging and discharging without exist of spikes in current waveform.

Experimental Results (a) Output voltage, current, and dc-link voltages, (b) voltage and currents of SCs, (c) Step change in R-L load from (10 Ω + 20 mH) to (20 Ω + 20 mH), d) Step change in R-L load from (20 Ω + 20 mH) to (10 Ω + 20mH), (e)change in modulation index (ma) from at (d) 1 to 0.5 (f) 1 to 0.2, (g) Waveforms of the output voltage While changing the reference dc-link voltages from 300 V to 350, (h), and from 300 to 300 V.

Figure 12c and d shows the output voltage (vo), load current (io), and voltages across the SC when an R-L load is subjected to a step change at t = 0.25s from (10 Ω + 20 mH) to (20 Ω + 20 mH) and from (20 Ω + 20 mH) to (10 Ω + 20 mH). Despite the rapid application of the R-L load, the generated output voltage effectively maintains the AC output voltage without an unwanted drop, and the proposed topology can maintain the SC voltages and output voltage step during sudden load changing conditions.

The performance of the proposed structure is investigated in this case under varied modulation index conditions. The waveforms of the output voltage (vo), load current (io), and voltage across the SCs (CSC1, CSC2) where the modulation index (ma) of the suggested inverter changes from ma = 1.0 to ma = 0.5 at time instant t = 0.1s shown in Fig. 12e. Its observed that the DC-link voltages were effectively balanced during these dynamic operations.

Figure 12f test the performance of proposed inverter when ma of the suggested inverter changes from ma = 1 to ma = 0.2. The output voltage waveform (vo) clearly shows that changing the modulation index leads to a drop in levels in the single-phase AC output voltage, decreasing from 9 to 2 levels. Despite this alteration, the proposed inverter continues to operate as a multilevel inverter with lower levels, and the voltage across SCs (CSC1, CSC2) remains balanced. This finding confirms the robust performance in response to modulation index fluctuations.

The proposed SCMLI topology was further tested under source voltage variation from 300 to 350 V and back to 300 V, as illustrated in Fig. 12g, h. The resulting output currents maintained constant peak value and their sinusoidal waveform. The results highlight its capability to maintain consistent output voltage and waveform quality despite fluctuations in the input source. This feature makes it highly suitable for renewable energy applications, where source voltage variations are common due to the intermittent nature of solar PV and wind energy.

From the Fig. 13, the voltage THD is 8.6%. Furthermore, the spectrum indicates that voltage harmonics reside around the switching frequency (i.e., 5 kHz), and hence, small filter is enough to bring even the voltage THD within the limits of IEEE-519 standards.

Quantitative comparisons against conventional topologies

A comparison study is conducted in this part against some of the latest topologies8–]29 to illustrate the feature stated in the previous section. The comparison takes into account the available number of power switches, diodes, capacitors, voltage gain, and TSV. Table 3 describes the topologies in terms of comparative parameters. In terms of number of power switches, the topologies mentioned in8,12, and13 used high number of power devices. It is seen that the number of switches per voltage level of the proposed SC-MLI is among the least in comparison.

The topology presented in 8,9,13,14,15,16,17,23 and 29 suffer from high current spike and hence the switches are selected with high voltage ratings which increases the overall inverter cost and the overall efficiency of these topologies is relatively less due to high loss across the power switches. The topology proposed in 12,17,21,23, and 28 they use soft-charging technique which significantly decreases the current spike. However, topology in 12 use high number of inductors to provide soft-charging which make bulky inverter structure. In contrast, the proposed topology [P] uses only one inductor with minimum inductance (0.25mH) to provide soft charging to SCs.

When it comes to the boosting factors, the gain shown in references8,9,12–]17,21-23,27, and29 comes from using switches with higher voltage ratings. This raises the total standing voltage (TSV) across the switches, which makes the inverter more expensive and complicated. The proposed topology and the one in28, on the other hand, are unity-gain inverters that greatly lower the voltage stress on the semiconductor devices. This kind of technique is very useful for applications with low to medium power needs where cost, size, and thermal performance are very important design criteria.

In terms of THD, the topologies presented in29 and 17 exhibit lower harmonic content in the output voltage. However, the proposed inverter offers low THD compared to the other topologies listed in the comparison table, demonstrating improved output waveform quality.

The value of total Standing Voltage (TSV) is the main traditional metric employed for the evaluation of SC-MLI topologies. The topologies9,13,15,17,27, and29 experience higher TSV, which directly impacts their performance and results in lower efficiency compared to the proposed topology. The proposed SC-MLI topology has considerably lesser TSV than existing topologies.

The cost function (CF) of all topologies has been determined considering the device count with the voltage ratings of devices:

where \(\alpha\) is factor which is associated with the voltage stress across the power switches, for safety, this factor considered to be 90% of the maximum allowable voltage across the switch (\(\alpha = 0.9\)). It is observed from Table 3 that, due to large number of power switches and switched capacitors, The CF of these topologies is high in comparison to the proposed SC-MLI [P].

Conclusion

This study introduced a novel 9-level SC-MLI featuring a single DC source and reduced number of power switches. The main features of this configuration are minimized TSV across the power switches and the integration of inductor between the input source and the SC charging loop, enabling soft charging of capacitors. This approach effectively minimizes current spikes and reduces total standing voltage stress across the power switches. A detailed comparative analysis highlights the superiority of the proposed topology over recent SC-MLIs in terms of component count, efficiency, and performance. Power loss calculations, including both switching and conduction losses, confirm high efficiency, achieving 96.96% at 300W and 96.42% at 900W. A laboratory prototype of the basic unit was developed, and the experimental validation confirmed close agreement with simulation results under various modulation indexes, demonstrating the practical viability and robustness of the proposed SC-MLI design.

Data availability

Data and codes for simulation-based items can be furnished on demand from the corresponding author.

References

Rahimi, T. et al. Single-phase 15-level inverters for uninterruptible power supply applications: Fault-tolerant strategies. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 69(4), 1055–1067. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCE.2023.3320632 (2023).

Ranjan Das, S. et al. Fuzzy controller designed-based multilevel inverter for power quality enhancement. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 70(2), 4839–4847. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCE.2024.3389687 (2024).

Yao, M., Hiskens, I. A. & Mathieu, J. L. Mitigating voltage unbalance using distributed solar photovoltaic inverters. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 36(3), 2642–2651. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRS.2020.3039405 (2021).

Bana, P. R., Panda, K. P., Naayagi, R. T., Siano, P. & Panda, G. Recently developed reduced switch multilevel inverter for renewable energy integration and drives application: Topologies, comprehensive analysis and comparative evaluation. IEEE Access 7, 54888–54909. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2913447 (2019).

Awadelseed, A., Lewicki, A. & Kondratenko, D. 1-ϕ seven-level switched-capacitor boost multilevel inverter topology with optimized number of components. IEEE Access 13, 64148–64159. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3558617 (2025).

Barzegarkhoo, R., Forouzesh, M., Lee, S. S., Blaabjerg, F. & Siwakoti, Y. P. Switched-capacitor multilevel inverters: A comprehensive review. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 37(9), 11209–11243. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPEL.2022.3164508 (2022).

K. Jena et al. A novel multigain switched-capacitor-based topology with reduced part count. International Transactions on Electrical Energy Systems 2024. https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/2944846 (2024).

Sathik, M. J. A nine level ANPC boost type inverter topology with reduced component stress. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 71(1), 380–384. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSII.2023.3305230 (2024).

Iqbal, A., Awadelseed, A. & Guzinski, J. High-efficiency switched-capacitor multilevel inverter topology with lower number of switching components. IEEE Access 13, 84941–84953. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3569148 (2025).

Awadelseed, A., Lewicki, A. & Iqbal, A. Single-phase 15-level switched-capacitor boost multilevel inverter topology for renewable energy applications. IEEE Access 12, 90782–90793. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3419265 (2024).

Jena, K. et al. A single DC source generalized switched capacitors multilevel inverter with minimal component count. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 2023, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/3945160 (2023).

Dhara, S. & Somasekhar, V. T. A nine-level transformerless boost inverter with leakage current reduction and fractional direct power transfer capability for PV applications. IEEE J. Emerg. Select. Top. Power Electron. 10(6), 7938–7949. https://doi.org/10.1109/JESTPE.2021.3074701 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. A nine-level switched-capacitor step-up inverter with low voltage stress. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 18, 1147–1159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42835-022-01187-z (2023).

Harbi, I., Ahmed, M., Hackl, C. M., Kennel, R. & Abdelrahem, M. A nine-level split-capacitor active-neutral-point-clamped inverter and its optimal modulation technique. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 37(7), 8045–8064. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPEL.2022.3144876 (2022).

Lin, W., Zeng, J., Hu, J. & Liu, J. Hybrid nine-level boost inverter with simplified control and reduced active devices. IEEE J. Emerg. Select. Top. Power Electron. 9(2), 2038–2050. https://doi.org/10.1109/JESTPE.2020.2983205 (2021).

Jena, K., Kasinath et al. A 4-X Gain 9-Level Multilevel Inverter Topology with Reduced Part Count. Scientia Iranica, (2025).

Varesi, K., Esmaeili, F., Deliri, S. & Tarzamni, H. Single-input quadruple-boosting switched-capacitor nine-level inverter with self-balanced capacitors. IEEE Access 10, 70350–70361. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3187005 (2022).

Sathik, J., Siddique, M. D., & Almakhles, D. 1-φ dual boost ANPC type inverter topology with high voltage gain. In IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications, 60(2), 3418–3426. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIA.2024.3350011 (2024).

Pal, P. K., Jana, K. C., Siwakoti, Y. P., Ali, J. S. M. & Blaabjerg, F. A switched-capacitor multilevel inverter with modified pulsewidth modulation and active DC-link capacitor voltage balancing. IEEE J. Emerg. Select. Top. Power Electron. 12(2), 1215–1229. https://doi.org/10.1109/JESTPE.2023.3285690 (2024).

Zeng, J., Wu, J., Liu, J. & Guo, H. A quasi-resonant switched-capacitor multilevel inverter with self-voltage balancing for single-phase high-frequency AC microgrids. IEEE Trans. Industr. Inf. 13(5), 2669–2679. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2017.2672733 (2017).

Kumari, S. & Sandeep, N. A self-balancing switched-capacitor-based dual boosting nine-level inverter. IEEE J. Emerg. Select. Top. Power Electron. 11(5), 5311–5320. https://doi.org/10.1109/JESTPE.2023.3298398 (2023).

Mansourizadeh, H. et al. A 13-level switched-capacitor-based multilevel inverter with reduced components and inrush current limitation. Sci. Rep. 15, 290. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-84148-y (2025).

Seifi, A. et al. Capacitor based topology of cross-square-switched T-type multi-level inverter. Sci. Rep. 14, 3166. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-53568-1 (2024).

Singh, A. K., Mandal, R. K. & Anand, R. Quasi-resonant switched-capacitor-based seven-level inverter with reduced capacitor spike current. IEEE J. Emerg. Select. Top. Power Electron. 11(2), 1953–1965. https://doi.org/10.1109/JESTPE.2022.3224536 (2023).

Zeng, J., Lin, W. & Liu, J. Switched-capacitor-based active-neutral-point-clamped seven-level inverter with natural balance and boost ability. IEEE Access 7, 126889–126896. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2927351 (2019).

Zaid, M. et al. Performance analysis and control of a novel 7-level active neutral point clamped (ANPC) topology. IET Power Electron. 16, 1255–1270. https://doi.org/10.1049/pel2.12466 (2023).

Liu, J., Wu, J., Zeng, J. & Guo, H. A novel nine-level inverter employing one voltage source and reduced components as high-frequency AC power source. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 32(4), 2939–2947. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPEL.2016.2582206 (2017).

Pal, P. K., Jana, K. C., Siwakoti, Y. P., Majumdar, S. & Blaabjerg, F. An active-neutral-point-clamped switched-capacitor multilevel inverter with quasi-resonant capacitor charging. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 37(12), 14888–14901. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPEL.2022.3187736 (2022).

Islam, S., Siddique, M. D., Iqbal, A. & Mekhilef, S. A 9- and 13-level switched-capacitor-based multilevel inverter with enhanced self-balanced capacitor voltage capability. IEEE J. Emerg. Select. Top. Power Electron. 10(6), 7225–7237. https://doi.org/10.1109/JESTPE.2022.3179439 (2022).

Funding

This research was funded in whole by National Science Centre, Poland under 2024/53/N/ST7/00711. For the purpose of Open Access, the author has applied a CC-BY public copyright license to any Author Accepted Manuscript (AAM) version arising from this submission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ahmed Awadelseed performed experiments and analyzed the obtained data, writing original paper. Arkadiusz Lewicki reviewed the research proposal and supervised the study. Charles Odeh performed validation, formal analysis, and analyzed the obtained data. Atif Iqbal reviewed the research proposal and supervised the study. All the authors participated in writing and giving feedback on the manuscript and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Awadelseed, A., Lewicki, A., Odeh, C. et al. A nine-level switched-capacitor multilevel inverter based on ANPC topology with optimized component count and suppressed charging current. Sci Rep 16, 5126 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34842-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34842-2