Abstract

The increasing level of cadmium (Cd) contamination in soil due to anthropogenic actions is a significant problem. This problem not only harms the natural environment, but it also causes major harm to human health via the food chain. The use of chelating agent is a useful strategy to avoid heavy metal uptake and accumulation in plants. In this study, randomized design pot experiment was conducted to evaluate potential role of malic acid (MA) and tartaric acid (TA) foliar spray to mitigate Cd stress in Spinacia oleracea L plants. For Cd stress, S. oleracea plants were treated with CdCl2 solution (100 µM). For control, plants were given distilled water. One week after Cd stress, MA and TA foliar spray was employed at concentration of 100 and 150 µM for both. The results of this study revealed that Cd stress (100 µM) significantly reduced growth attributes, photosynthetic pigments and related parameters and gas exchange attributes. Cadmium stress also stimulated antioxidant defense mechanism in S. oleracea. Cd stressed plants had elevated levels of Cd metal ions in root and consumable parts (i.e. leaves) and caused severe oxidative damages in the form of increased lipid peroxidation and electrolytic leakage. MA and TA supplements at both low and high levels (100 and 150 µM) effectively reversed the devastating effects of Cd stress and improved growth, photosynthesis and defense related attributes of S. oleracea plants. These supplements also prevented excessive accumulation of Cd metal ions as indicated by lowered Cd metal contents in MA and TA treated plants. These findings demonstrated that MA and TA treatments can potentially reduce Cdl induced phytotoxicity in plants by reducing its uptake and enhancing photosynthesis and defense related parameters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

During the last few years, increased population in urban areas, industrial revolution, extensive farming, and excessive consumption of natural assets that seriously damages agricultural regions have made metal pollution the greatest critical environmental problems1. Cadmium (Cd) being an unnecessary metal, adversely impacts plant growth and development. It is recognized as a severe consequential contaminant due to its more solubility in water, leading to deleterious impact even at minimal level2. Cadmium pollution in leafy vegetables is a significant matter due to their high accumulation potential3. It is a significant toxic pollutant commonly found in soil, often surpassing the national soil environmental quality standards, which typically set the threshold at 1 mg/kg4. The World Health Organization (WHO) states that the maximum permissible amount of Cd in people is 25 µg kg−1 of total body weight, whereas the acceptable level of both soil and vegetation is 0.02 and 1 mg kg−1, respectively5. The absorption of Cd by plants hinders both growth and the intake of necessary nutrients6. The main sources of Cd are sewage effluent along with fertilizers containing phosphates, which are used to enhance soil fertility. There are fertilizers that include at least 300 mg/kg of Cd. Cd disrupts crucial physio biochemical processes, leading to severe inhibition of plant growth and development7. Cd accumulates significantly within plants, resulting in growth inhibition, prevent photosynthesis, and the possibly emergence of significant physiological stressors, including cellular mortality8. In addition to limiting the development of photosynthetic pigments and reducing photosynthesis efficiency, Cd stress may elevate the production of reactive oxygen species and increase peroxidation9. Additionally, Cd diminishes the uptake of essential ions by plants leading to chlorosis in the leaves. Calcium (Ca), Phosphorus (P), Magnesium (Mg), potassium (K), and Manganese (Mn) movement and absorption are often inhibited by Cd10. It is essential to figure out an acceptable way to clean up soil polluted with Cd as metals can pile up in vegetation and penetrate the body of a person via food sources, posing a threat to health and potentially triggering prolonged toxicity9.

Under the influence of metal stress, organic acids play a role in maintenance of plant growth by influencing chemical structure, secondary metabolic products, and the accumulation of ions for regulating homeostasis11. Low molecular weight organic acids (LMWOAs) seem to be important for the activation and movement of metals in the environment12. Malic acid (MA) is an organic dicarboxylic acid that is produced throughout plant cell metabolic processes and is essential for the Krebs cycle, which produces energy. The metabolism of MA in plant mitochondria is facilitated by the malic enzyme, a capability considered unique to plants13. Its versatile nature, lack of toxicity, widespread accessibility, and cost effectiveness make it suitable for use as an agent of cross-linking in various applications14. It has a different role in plants like regulating pH and maintaining the osmotic equilibrium within the vacuole15. It is essential for the regulating the turgidity of cells as well as pH level within cytoplasm in variety of plants16. It can reduce oxidative harms by controlling the enzymatic as well as non-enzymatic antioxidants in stress caused by Cd in Miscanthus sacchariflorus7. It has been studied especially for its ability to alleviate the adverse impact of stress caused by heavy metals. A prior study shown a considerable improvement in pear fruit condition and absorption of nutrients when MA and NPK fertilizer applied in combination17. Malic acid aids in nutrient absorption, functions of stomata, and temporarily stores carbon in C3 plants. MA facilitates the dissolve insoluble elements as well as lowers the pH level of a soil that is alkaline18.

Tartaric acid (TA) is typically found in plants, including algal to vegetation, where it plays a variety of roles in the cells’ metabolic activities19. The root zone of plants secretes TA, which influences the absorption as well as the elimination of metals that are in soil20. TA might be spontaneously produced by soil microbes as well as plants’ root exudates8. Further investigations revealed that TA effectively stimulates development of plants and accumulates heavy metal contaminants from the soil21. TA is a metal chelator that mobilize metals in the soil and increase their intake by plants22. Tartaric acid was key for reducing the ultra-structural damage induced by Cd to plants23. Furthermore, it could minimize the oxidative damage resulting from metal stress. Metallic elements can become easier to transport around the rhizosphere because of its capacity to make complexes with metallic ions20. Ultimately, it serves as a metal chelator, a powerful antioxidant, as well as a synergistic agent for various other antioxidants24.

Spinach (Spinacia oleracea) is a popular leafy crop from the Amaranthaceae family with large, green leaves, significantly high growth rate, and the potential to accumulate metals6. It is extensively grown worldwide and is advised by nutritionists for intake in diet. Turkey, China, Japan, Indonesia, and the United States are some of the greatest suppliers of S. oleracea for marketing25. Large-scale S. oleracea production occurs in Pakistan as a cold-season vegetable. S. oleraceais well-known for having a higher level of iron26. S. oleraceais a major source of essential vitamins (A, B, C and K), minerals (Ca, Mg, K and Mn) folate and dietary fibers. It comprises of 91% water, 4% carbohydrate, and 3% amino acids27. It serves as one of the most significant protein forms because it contains essential amino acids28. Leafy greens possess a higher capacity to uptake extremely harmful substances and are major contributor to a substantial 70% of total buildup of Cd among individual29. For its extensive use in diet, it is essential to eradicate the prevailing threat of heavy metal toxicity in its consumers. For this reason, there is an urgent need for developing new ways to limit heavy metal accumulation in consumable parts of S. oleracea plants.

The effect of MA and TA exogenous supplements on growth, physiological, biochemical attributes, and Cd uptake in S. oleracea plants is least explored. While MA and TA are known to play roles in physiological and metabolic pathways, their specific mechanisms in enhancing growth and reducing Cd uptake under stress conditions remain unclear. Both MA and TA are metal chelators and have potential to mobilize metal ions and detoxify them in above ground parts of plants. Research on mitigating heavy metals toxicity often focuses on widely studied organic acids like citric acid, oxalic acid, or EDTA. These compounds are extensively studied because they are well-documented as effective chelators for reducing heavy metal toxicity. MA and TA, while naturally occurring organic acids, have received less attention in terms of their application in reducing heavy metal stress. Despite limited exploration, interest in MA and TA is growing due to their natural occurrence in plants and potential role in metal detoxification. Their dual role in chelation and improving metabolic functions makes them promising candidates for future research. It is hypothesized that exogenous application of MA and TA supplements can eliminate Cd metal accumulation in S. oleracea plants under Cd stress conditions. This study aimed to investigate the impact of MA and TA on the growth and physiological responses of S. oleracea exposed to Cd stress. To evaluate the role of MA and TA in alleviating the adverse effects of Cd toxicity on plant growth, photosynthesis, gas exchange parameters and antioxidant enzyme activities. This study also aimed to examine the potential of MA and TA in limiting Cd metal accumulation in consumable parts of S. oleracea. These findings will contribute valuable insights into potential strategies for mitigating heavy metal stress in S. oleracea and can bring innovation in agricultural practices with improvements for food security and environmental health.

Materials and methods

Experimental design and layout

The S. oleracea seeds were obtained from the Punjab seed corporation, Lahore. The experiment was performed in natural conditions, at the Botanical Garden, University of Education, Lahore. The average moisture level was 58% with an average of 25/11 oC day/night temperature during the experimental duration. The average rainfall during these months was approximately 11 mm per month. Soil used for this experiment was sieved to remove debris, rocks, and other impurities. About 5 kg of the soil added in pot. The pot used in this study was 11 cm in diameter and 20 cm in height. The soil was loamy and coarse in texture with pH 7.23 and EC 860 dS/m. When cadmium (Cd) applied in soil the pH of soil becomes 6.07 and EC was 1376 dS/m. Two factor completely randomized design pot experiment with three replicates was conducted to evaluate the toxic effect of Cd (100 µM) and ameliorative role of MA (malic acid) and TA (tartaric acid) treatments at different concentrations (100 and 150 µM), see Table 1. Seeds were sown in the month of November 2023. Seeds were sterilized with 10% sodium hypochlorite solution for 10 min and then rinsed thoroughly with distilled water more than 3 times. Healthy and uniform sized seeds (10–12 per pot) were sown in the plastic pots evenly. After germination thinning was performed and 4 same sized seedlings were kept at uniform distance. At 2–3 leaf stage, the seedlings were exposed to different treatments (Table 1). 2 weeks after germination, for Cd stress S. oleracea plants were treated with 500 mL of CdCl2 solution (100 µM), only for once during whole experimental period. For control, plants were treated with the same volume of distilled water. One week after Cd stress, MA and TA foliar spray was done at concentration of 100 and 150 µM for both. During this whole experiment, MA and TA were applied 2 times in total at specific interval of 15 days. On the 8th week of the experiment, plants were harvested for the growth analysis. Although all four plants within each pot showed uniform growth pattern, we selected the healthier and most vigorous plant within the pot for further analysis. After harvesting, plants were carefully cleaned with pure water to remove soil particles from the plant sample. The plant samples were wiped with smooth fabric to remove moisture. Growth parameters (root and shoot lengths, fresh weights, and dry weights) were recorded using weighing balance and ruler. After harvesting plant samples were stored in deep freezer at 4 oC for assessment of biochemical attributes listed below.

Assessment of physiological attributes

Determination of chlorophyll and carotenoid contents

Fresh leaf sample (0.5 g) from each replicate was taken and crushed with pestle and mortar. After that 10 mL of 80% acetone was added in crushed leaf sample to prepare its extract. The prepared extract was then filtered and kept in refrigerator (4 oC) for 24 h. The optical density of filtrate was read at 480, 645, 663 nm. Chlorophyll a and b contents were measured using following formulas30.

In this; V = Volume of extract (mL), W = Weight of fresh leaves, OD = Optical density.

The following equation was used to calculate carotenoid content as stated by Lichtenthaler31.

Relative water contents (RWC%)

The leaves of uniform size were taken from every replicate. Each leaf was promptly weighed (FW) these leaves were allowed to soak in distilled water for three hours in 25–26 °C. After that, their turgid weight (TW) was noted. Kept all these leaves in oven (24 h) for drying at 80 °C. Then dry weight (DW) of leaves was recorded. RWC of the sample were calculated by using formula32.

Measurement of gas exchange parameters

During 12:00–2:00 pm, Infrared Gas Analyzer (IRGA) LCpro SD (ADC Bio Scientific Ltd. Hoddesdons, UK) was used to determine the stomatal conductivity (gs), net photosynthesis rate (Pn), transpiration rate (Tr) as well as intracellular carbon dioxide (Ci) on fully developed leaves. The leaf chamber had a pressure of 998 kPa, flow rate 200.5 mL/min, with average leaf temperature 30 °C and light intensity was 914 mmol m−2s−1. From the center of the rosette 3rd completely developed leaf was selected for measuring gas exchange parameters.

Soil plant analysis development (SPAD) value measurement

For measuring SPAD value, we selected 3rd fully developed leaf from the center of the rosette. Readings were taken from minimum 10 different positions of the same leaf avoiding the midrib region and then averaged. The soil plant analysis development value of leaf was measured by using atLEAF CHL BLUE (0131 − 58 Ver 1.3). This device measures the chlorophyll content in terms of relative nitrogen content of leaf by measuring light transmittance.

Estimation of chlorophyll fluorescence

An OS30p + Chlorophyll Fluorometer (Opti-sciences, Inc. | Hudson, NH 03051, USA) was used to measure the parameters of chlorophyll fluorescence. Before taking readings, leaves were dark adapted for 15 min using clips. Dark adapted leaves were then exposed to instant light measure potential and maximum quantum efficiency of PSII photochemistry (Fv/Fm).

Estimation of biochemical attributes

Total phenolics

Weighed dried leaf powder (0.5 g) and homogenized in 80% acetone for a minute. The resultant mixture was then centrifuged at 4000 g for fifteen minutes at 4 oC. After removing the supernatant, dry solid leftovers were collected for further processing. 10 mL of methanol was then added in air dried solid residues. Following that, reaction mixture comprising 2 mL of prepared solution, 0.8 mL of Na2CO3(7.5%) and 1 mL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent was prepared. This reaction mixture was left over for 30 min, and OD was read at 765 nm using A UV/VIS spectrophotometer. Gallic acid equivalent per gramme of dry product were calculated for estimating the total amount of phenolic compounds33.

Leaf proline

Proline contents were determined using the procedure described by Bates et al.34. 0.2 g fresh leaf was taken and mixed in 5 mL of 3% sulfosalicylic acid. Whatman filter paper was then used for purifying the mixture. Acid ninhydrin was prepared by mixing 2.5 g of ninhydrin, 60 mL of glacial acetic acid and 40 mL of Orthophosphoric acid (6 M) in a beaker. In test-tube, 2 mL of acid ninhydrin, 2 mL of glacial acetic acid, and 2 mL of homogenized solution were taken. After that, these test tubes were placed in an oven at 100 °C for 60 min. Following that these test-tubes were placed in ice bath to stop the reaction. 4 mL of toluene was added in the resulting product and mixed rapidly using vortex machine. Chromophore was extracted from the liquid phase that contained toluene. Absorbance was read at 520 nm using UV/VIS spectrophotometer.

Estimation of stress markers

Malondialdehyde (MDA)

It was estimated following method proposed by Cakmak & Horst35 with few modifications. Homogenate of fresh leaf (0.5 g) was prepared in 3 mL of 1% trichloroacetic acid (TCA). This homogenate was centrifuged at 20,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 oC. The supernatant (0.5 mL) was taken in test tubes containing 3 mL of 0.5% thiobarbituric acid which was prepared in 20% TCA solution. The resultant mixture was heated at 95 oC for 50 min using a shaking water bath. The reaction was ended through rapid cooling using an ice water bath. Once again samples were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min and OD was read at 532 and 600 nm using UV/VIS spectrophotometer. The following formula was used to determine level of MDA (nmol) in each sample.

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)

It was determined by using the method discussed by Velikova et al.36. Using pre chilled pestle and mortar, 0.5 g of fresh leaf was blended in 0.1% TCA solution. This mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 oC. 0.5 mL of supernatant was transferred to the test tube. 1 mL of potassium iodide solution and 0.5 mL of potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7) were added in this test tube. Components in the test tube were mixed rapidly using vortex machine and OD was read at 390 nm using UV/VIS spectrophotometer.

Relative membrane permeability (RMP%)

Fully matured uniform sized leaves were taken from each replicate. These leaves were chopped and added in 20 mL of deionized water. The mixture was rapidly mixed over vortex machine for 5 s and checked for electrical conductivity (EC0) value using EC meter. After that this mixture was kept in refrigerator on 4 °C for whole day and EC1 was evaluated. Following that the mixture was heated in autoclave for 20 min at 120 °C and EC2 were noted. The RMP (%) was measured using formula as suggested by Yang et al.37.

Total soluble protein (TSP)

To prepare enzymes extract, 0.5 g fresh leaf was taken and crushed in pestle and mortar to make a homogenate in precooled 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (10 mL, pH 7.8). This homogenate was taken in conical flasks and centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 20 min at 4 oC. Enzymes extract obtained in the form of supernatant was stored in deep freezer for later use. For estimation of TSP, 100 mg of Coomassie Brilliant Blue was dissolved in 50 mL of ethanol (95%) and this solution was added in 100 mL of 85% phosphoric acid. The final volume was raised to 1 L and prepared Bradford solution. Enzymes extract (0.1 mL), and this Bradford solution (5 mL) were mixed in test-tube. UV/VIS spectrophotometer was then used to determine the optical density at the wavelength of 595 nm.

Determination of antioxidant enzymes activities

Catalase (CAT) and peroxidase activities

For estimation of CAT activity reaction mixture was prepared by adding 0.1 mL enzymes extract (discussed for TSP), 1.9 mL H2O2(5.9 mM), 1 mL phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.0). Its OD was checked at 240 nm after every 30 s in time frame of 2 min38. For POD activity a reaction mixture was prepared that contained; 0.7 mL of 50 mM of phosphate buffer (pH 5.0), 0.6 mL of 20 mM guaiacol, 0.6 mL of 40 mM H2O2and 0.1 mL for enzymes extract. Using UV/VIS spectrophotometer, absorbance was noted at wavelength of 470 nm for every 30 s in total of 150 s for the estimation of POD acctivity39.

Ascorbate peroxidase (APX) and Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity

A reaction solution containing 2.70 mL of 50 mM phosphate buffer, 0.10 mL ascorbic acid (7.50 mM), 0.10 mL 300 mM H2O2, as well as 0.10 mL enzyme extract (for TSP) was prepared. To estimate the APX enzymes activity OD was read at 290 nm for every 30 s in time period of one minute using UV/VIS spectrophotometer40. For SOD activity, the reaction mixture was made of 0.3 mL of 130 mM methionine, 0.3 mL of 50 µM nitro blue tetrazolium, 0.3 mL of 100 µM EDTA-Na2and 0.3 mL of 20 µM riboflavin. After adding 0.05 mL of the enzyme extract into the reaction mixture, the entire mixture was exposed to 4000 lx light for 20 min. Superoxide anions produced on illumination of riboflavin react with nitro blue tetrazolium in presence of methionine and form formazan, a blue colored complex. SOD present in the sample solution will react with these superoxide anions and this will ultimately result in less products of formazan. Hence, change in color or OD was read at 560 nm to estimate presence of SOD enzymes using UV/VIS spectrophotometer41.

Determination of nutritional ions and cd contents

For the purpose, 0.1 g dry powder of root and shoot was taken in test tubes. 2 mL H2SO4 was added in the tubes and left for overnight. Following that these samples were heated in digestion flask and added in it H2O2 dropwise till the solution became colorless. This solution was filtered, and total volume was raised to 50 mL using distilled H2O. Flame-photometer was used to measure the K+ and Ca2+ contents. While for Cd atomic absorption spectrophotometer was operated. Standard solutions of K+, Ca2+ and Cd were prepared and used to draw standard curves for quantification of these minerals.

Statistical analysis

Two-way ANOVA, graphs and LSD mean compare test were employed using R software. Correlation and PCA analysis were also performed on R. Graph bars presented an average of three replicates ± standard errors. Graphs bars sharing same letters (obtained after LSD test using R software) are not significantly different at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Effect of malic and tartaric acid on biomass and growth attributes of S. oleracea grown in cadmium contaminated soil

Shoot length

Cadmium stress reduced shoot length by 9%, as equated to control plants. Shoot length was improved with MA and TA supplements. Their exogenous application was highly effective (p < 0.001) against shoot length. Like, MA1 and MA2 incremented shoot length by 44 and 37% in control plants while 50 and 46% in stress plants. Similarly, TA supplements improved shoot length by 33 and 26% in control while 38 and 31% in stress plants, compared to their respective controls. Combined treatment of MA and TA at both low and high levels was more effective than their sole treatments (Figs. 1 and 2A).

Effect of malic acid and tartaric acid on (A) shoot length, (B) root length, (C) number of leaves and (D) leaf area of Spinacia oleracea plants grown in control and Cd contaminated soil. Data presented in the graph is the mean of three replicates ± standard error. Similar letters obtained after LSD mean compare test shows non-significant differences at p < 0.05.

Root length

As shown in Fig. 2B various treatments applied in this research work had highly significant impact (p < 0.001) on root length. Cadmium (Cd) reduced root length by 16% compared to control. Subsequent increase in concentrations of malic acid (MA) and tartaric acid (TA) successively improved root length in both control and stress conditions. Malic acid treatments MA1 and MA2 increased root length by 20 and 44% as equated with control. Similarly, under Cd toxicity these supplements increased root length by 40 and 21%, respectively. TA1 and TA2 also had similar effects on root length. Following treatments increased root length by 60 and 84% in control plants while 64 and 93% in stress plants. It was observed that high concentrations for MA and TA were less effective than low concentrations.

Number of leaves and leaf area

S. oleracea plants grown in Cd contaminated soil also had a lower number of leaves compared to control plants. Similarly, these plants also had reduced leaf area or size. Various treatments applied in this research had significant impact on leaf number and area at p < 0.001. Number of leaves and leaf area were reduced by 28 and 33%, respectively, in Cd treated plants compared to control. Similar to SFW, plants treated with varying concentrations of MA and TA supplements had improved number of leaves and leaf area up to 35–80% in stress conditions (see Fig. 2C & D).

Shoot fresh and dry weight

Shoot fresh and dry weight were also effectively hampered by Cd contamination. Effect of all treatments applied in this work over SFW and SDW was significant (p < 0.01 and p < 0.001, respectively). Cd stress reduced SFW and SDW by 29 and 24%, respectively, compared with control plants. On the other hand, MA and TA applications, either sole or synergistic, reversed this loss in SFW and SDW under Cd stress. These treatments, when applied on different concentrations, incremented SFW and SDW up to 27–76% under stress conditions as compared to stress only plants (Fig. 3A & B).

Effect of malic acid and tartaric acid on (A) shoot fresh weight, (B) shoot dry weight, (C) root fresh weight and (D) root dry weight of Spinacia oleracea plants grown in control and Cd contaminated soil. Data presented in the graph is the mean of three replicates ± standard error. Similar letters obtained after LSD mean compare test shows non-significant differences at p < 0.05.

Root fresh and dry weight

Root fresh and dry weights were significantly impended by Cd toxicity. These were reduced to 2.03 and 0.4 g in stress plants from 2.63 to 0.51 g in control plants, respectively. Malic and TA treatments effectively recovered this loss in plant biomass in stress plants. MA at 100 and 150 µM increased RFW by 23 and 41% in control whereas by 22 and 34% in stress plants. Similar to this TA supplements incremented RFW by 49 and 60% in control whereas by 40 and 64% in stress plants, respectively, compared to their respective control groups. MA and TA treatments also incremented RDW in similar way (Fig. 3C & D).

Effect of MA and TA on photosynthesis related attributes of S. oleracea grown in Cd contaminated soil

Chlorophyll a, b, and carotenoid pigments

Figure 4A-C depicts that photosynthetic pigments were highly reduced in Cd treated plants. As chlorophyll a and b were reduced by 37 and 15%, respectively, compared to control. Similarly, carotenoids were reduced by 14% in Cd treated plants, compared with control. On the other hand, MA and TA supplementations significantly improved these all pigments in both control and stress conditions. As shown in Fig. 4A, MA1 and MA2 increased chl a by 5 and 19% in control plants whereas by 44 and 85% in Cd stressed plants, compared to their respective controls. Similarly, TA1 and TA2 increased chl a by 26 and 68% in control group whereas by 88 and 104%, respectively, in stressed group of plants. Their synergistic application was even more effective to improve chl a in Cd stressed plants. While chl b were increased up to 23–77% with MA and TA supplementation in control conditions. Although in Cd stressed plants this increment in chl b ranged in 40–103% with MA and TA supplements compared to stress only plants. Similarly, MA and TA supplements alone or synergistically improved carotenoids in both control and stress conditions. For example, in Cd treated plants MA supplements at 100 µM and 150 µM increased carotenoids by 25 and 16%, respectively. Similarly, TA treatments at 100 µM and 150 µM improved carotenoids by 31 and 65%, respectively, compared to stress only plants. Synergistic application of MA and TA also effectively improved (46–71%) carotenoids in Cd stressed plants. All the treatments employed in this work had highly significant effects on these photosynthetic pigments at p < 0.001.

Effect of malic acid and tartaric acid on (A) chlorophyll a, (B) chlorophyll b, (C) carotenoids and (D) relative water contents of Spinacia oleracea plants grown in control and Cd contaminated soil. Data presented in the graph is the mean of three replicates ± standard error. Similar letters obtained after LSD mean compare test shows non-significant differences at p < 0.05.

Relative water contents

Figure 4D showed that S. oleracea plants reduce RWC from 54% in control to 45% in Cd contaminated soil. This reduction in RWC is also reflected in reduced shoot fresh weight in Cd stressed plants. Conversely, MA and TA treatments successfully retrieved this reduction in RWC. These treatments also add to RWC under all conditions. Like, MA at low and high level improved RWC by 39 and 17%, respectively in control pants. Whereas this increased RWC by 46 and 25% in Cd stressed plants. Similarly, TA supplements at low and high level increased RWC by 49 and 39% in control whereas by 60 and 51% in Cd stressed plants. Synergistic application of MA and TA at high level was not very effective in incrementing RWC. Furthermore, various treatments applied in this work had highly significant effects on RWC at p < 0.001.

Gas exchange attributes (photosynthesis rate, transpiration rate, stomatal conductance, and intercellular CO2)

Net photosynthesis rate (Pn) was significantly hampered (22%) by Cd stress compared to control. While MA and TA supplementations either alone or in combination improved Pn in both control and stress conditions. For example, MA at low and high level improved Pn by 14 and 31% in control plant compared to non-treated control. Similarly, TA1 and TA2 did this by 39 and 50%. While in Cd stressed plants MA1, MA2, TA1 and TA2 enhanced Pn by 30, 39, 66 and 78% respectively, compared to stress only plants (Fig. 5A).

Effect of malic acid and tartaric acid on (A) net photosynthesis rate, (B) transpiration rate, (C) stomatal conductance and (D) intercellular CO2 in Spinacia oleracea plants grown in control and Cd contaminated soil. Data presented in the graph is the mean of three replicates ± standard error. Similar letters obtained after LSD mean compare test shows non-significant differences at p < 0.05.

The results in Fig. 5B & C revealed that Tr and gs were also lowered (36 and 35%, respectively) by Cd toxicity. On the other hand, MA and TA treatments rescued this reduction in gs and Tr. These treatments improved gs and Tr in control plants as well. Like, MA at low and high level increased gs by 35 and 22% while Tr by 20 and 44%, respectively, compared to non-treated control. Similarly, TA improved gs by 59 and 74%, while Tr by 65 and 80%, respectively. Correspondingly, these treatments incremented gs and Tr in Cd stressed plants that ranged in 30–114%, compared with non-treated stress plants. Conversely, intercellular CO2 was increased (41%) in S. oleracea plants when given Cd stress. Although synergistic application of MA and TA reduced (11%) Ci in Cd stressed plants compared to stress only plants (Fig. 5D).

Soil analysis plant development (SPAD) value

Various treatments applied in this research work had highly significant impact (p < 0.001) on SPAD value. SPAD value was significantly hampered (8%) by Cd stress compared to control. While MA and TA supplementations either alone or in combination improved SPAD value in both control and stress conditions. For example, MA at low and high level improved SPAD by 11 and 18% in control plant compared to non-treated control. Similarly, TA1 and TA2 did this by 26 and 33%. While in Cd stressed plants MA1, MA2, TA1 and TA2 enhanced SPAD by 13, 19, 33 and 43% respectively, compared to stress only plants (Fig. 6A).

Effect of malic acid and tartaric acid on (A) soil plant analysis development value and (B) quantum efficiency of PSII in Spinacia oleracea plants grown in control and Cd contaminated soil. Data presented in the graph is the mean of three replicates ± standard error. Similar letters obtained after LSD mean compare test shows non-significant differences at p < 0.05.

Quantum yield of photosystem II (Φ PSII)

Quantum efficiency of PS II was reduced significantly (22%) in Cd stressed plants. This is also reflected by reduced photosynthesis rate under Cd stress. However, MA and TA treatments either alone or synergistically improved Fv/Fm in all conditions. For example, MA1 and MA2 increased efficiency of PSII by 9 and 15%, respectively in control plants. While these treatments increased Fv/Fm by 10 and 15% in Cd stressed plants compared with their respective control. Similarly, TA1 and TA2 enhanced Φ PSII by 15 and 23% in control plants whereas by 17 and 20% in Cd stressed plants, respectively, compared with their corresponding controls. Synergistic applications of MA and TA also effectively improved Fv/Fm in Cd stressed conditions. All the treatments applied in this work imposed highly significant (p < 0.001) effects on Φ PSII of S. oleracea (Fig. 6B).

Effect of MA and TA on biochemical parameters of S. oleracea grown in Cd contaminated soil

Total phenolics

In this study total phenolics were increased by nearly 2 folds in Cd stressed plants compared to control. Similarly, MA and TA treatments further enhanced total phenolics in all conditions. For example, MA at 100 µM and 150 µM increased total phenolics by 139 and 70% whereas TA at 100 µM and 150 µM increased this by 107 and 135%, respectively, compared to control. While in Cd stress plants these treatments increased total phenolics by 35, 22, 14 and 26%, respectively, compared with non-treated stress plants. Synergistic application of MA and TA was not very effective in incrementing total phenolics in Cd stressed plants (Fig. 7A).

Effect of malic acid and tartaric acid on (A) total phenolics, (B) leaf proline and (C) total soluble proteins in Spinacia oleracea plants grown in control and Cd contaminated soil. Data presented in the graph is the mean of three replicates ± standard error. Similar letters obtained after LSD mean compare test shows non-significant differences at p < 0.05.

Leaf proline

Proline is an osmo-protectant and has antioxidant properties. It also has a role in role maintaining ions homeostasis and osmotic potential. Thus, proline is a good indication for stress level in plants. In this research, proline contents were significantly enhanced in Cd treated plants. Compared with control plants, Cd stressed plants had nearly two folds more proline contents. Furthermore, MA and TA treatments either alone or in combined form effectively improved proline contents in both control and stress plants. For example, in Cd stressed plants MA1 and MA2 application increased proline contents by 12 and 22%. Similarly, TA1 and TA2 increased this by 29 and 37%, respectively, compared to non-treated stressed plants. All treatments applied in this work had highly significant (p < 0.001) effects on proline contents in S. oleracea (Fig. 7B).

Total soluble protein (TSP)

In Cd treated plants soluble proteins were increased by 54% compared to control. Furthermore, MA and TA supplements also enhanced soluble proteins in both control and stressed plants. MA supplements alone more effectively improved soluble proteins in Cd stressed plants compared to TA treatments and their synergistic application. MA1 and MA2 incremented soluble proteins by 30 and 22%, respectively, in Cd stressed plants compared to non-treated ones (Fig. 7C).

Effect of MA and TA on stress markers in S. oleracea grown in Cd contaminated soil

Malondialdehyde content

It was observed that Cd stress posed oxidative damage to S. oleracea plants. This is also evident from elevated levels of lipid peroxidation (malondialdehyde contents), hydrogen peroxide and relative membrane permeability. Lipid peroxidation as estimated by increased concentration of malondialdehyde was enhanced by 10% in Cd treated plants compared to control. It was further observed that MA and TA treatments at low and high levels, maintained cell’s integral structure. These supplements reduced lipid peroxidation i.e., malondialdehyde contents, in stressed plants compared to non-treated ones. The combined application of MA and TA at 100 µM was more effective in performing these actions. It reduced MDA contents by up to 47% in stressed plants compared to their respective control (Fig. 8A).

Effect of malic acid and tartaric acid on (A) malondialdehyde, (B) hydrogen peroxide and (C) relative membrane permeability of Spinacia oleracea plants grown in control and Cd contaminated soil. Data presented in the graph is the mean of three replicates ± standard error. Similar letters obtained after LSD mean compare test shows non-significant differences at p < 0.05.

Hydrogen peroxide

Hydrogen peroxide is a reactive oxygen species whose elevated level indicates stress in plants. In this research H2O2 was significantly increased (23%) in S. oleracea plants when exposed to Cd toxicity. Whereas MA and TA alone and synergistic applications, changes plant’s metabolism that detoxified reactive oxygen species (ROS), and reduced their level, especially H2O2 contents. Malic acid at low and high levels reduced H2O2 by 31 and 19% respectively in stressed plants compared to non-treated plants. TA supplements also reduced H2O2 in similar fashion. Its low and high concentration resulted in 10 and 22% reduction of H2O2 contents (Fig. 8B).

Relative membrane permeability

S. oleracea plants grown in Cd contaminated soil had loss their selective permeability. This interrupted the cell’s proper functioning and development. Relative membrane permeability in Cd exposed plants was increased by 62% compared to control. Alternatively, MA and TA supplementations either alone or synergistically reduced RMP in stressed plants compared stress only plants. For example, MA1 and MA2 reduced RMP by 40 and 59% whereas TA1 and TA2 did this by 32 and 46%, respectively, compared to non-treated stressed plants. However, their synergistic application did not perform much differently than alone treatments (Fig. 8C).

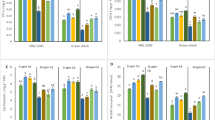

Effect of MA and TA on enzymatic antioxidants in S. oleracea grown in Cd contaminated soil

Catalase (CAT)

S. oleracea plants survived even in Cd contaminated soil. These plants might have adaptive mechanisms to scavenge oxidative damage caused by Cd toxicity. Furthermore, this might also involve synthesis of enzymatic antioxidants or elevation in their activity. In this work, increased activity of enzymatic antioxidants like catalase, peroxidase, ascorbate peroxidase and superoxide dismutase were observed in S. oleracea plants exposed to Cd stress. Catalase enzyme activity was increased by nearly one and half folds in stressed plants compared to control. MA and TA supplementations either alone or in combination further enhanced CAT activity in both control and stress plants, compared to their respective controls (Fig. 9A).

Effect of malic acid and tartaric acid on (A) catalase, (B) peroxidase, (C) ascorbate peroxidase and (D) superoxide dismutase activities in Spinacia oleracea plants grown in control and Cd contaminated soil. Data presented in the graph is the mean of three replicates ± standard error. Similar letters obtained after LSD mean compare test shows non-significant differences at p < 0.05.

Peroxidase (POD)

Peroxidase activity was also increased in Cd stress treated plants compared with control. This incremented POD activity by 67%. Nonetheless, MA and TA applications either alone or synergistic, had incremented POD activity in non-treated control. But these treatments reduced POD activity in Cd stressed plants as equated to non-treated stress plants. For example, MA1 and MA2 incremented POD by 49 and 32% in control plants while these supplements reduced POD by 11 and 20%, respectively, compared to their respective control plants. TA supplements also affected POD activity in similar fashion (Fig. 9B).

Ascorbate peroxidase (APX)

As depicted in (Fig. 9C) APX activity was enhanced significantly (72%) in Cd treated plants, compared with control. Whereas MA and TA treatments also enhanced APX activity in control plants. Conversely, these treatments hampered APX activity in Cd stressed plants compared to stress only plants. This showed reduced stress level in action of MA and TA supplements. Synergistic applications of MA and TA were more effective than alone treatments. For example, in Cd stressed plants, MA and TA synergistic treatments at low and high concentrations caused maximum reduction in APX activity (36 and 35%, respectively).

Superoxide dismutase (SOD)

Superoxide dismutase activity was also enhanced in Cd stressed plants. In this case, MA and TA supplements, either alone or in combination increase SOD activity in all conditions. Cd stress incremented SOD activity by 95% as compared to control. Whereas MA and TA treatments at low and high levels further improved SOD activity up to 15–36% compared to stress only plants. Various treatments applied in this work had highly significant effects on these enzymatic antioxidants at p < 0.001 (Fig. 9D).

Effect of MA and TA on nutritional ions (K + & Ca 2+ ) and Cd accumulation in root and shoot of S. oleracea grown in Cd contaminated soil

Treatments applied in this work had significant effects on K+ and Ca2+ in root (p < 0.01) and shoot (p < 0.001) of S. oleracea plants. K+ in root and its subsequent concentration in shoot was significantly deprived (20 and 5%, respectively) in Cd treated plants. Conversely, these plants when treated with various levels of MA and TA regained K+ ions in root as well as shoot. MA1 and MA2 incremented the K+ ions in root of Cd stressed plants by 32 and 17%, respectively. Similarly, TA1 and TA supplements also improved these ions in roots of Cd stressed plants. Furthermore, application of MA and TA also improved K+ ions in shoot of S. oleracea in both control as well as stress plants. This increment ranged in 16–59% in control plants whereas 25–57% in stressed plants (Fig. 10A & B).

Effect of Malic acid and Tartaric acid on (A) potassium in root, (B) potassium in shoot, (C) calcium in root and (D) calcium in shoot of Spinacia oleracea plants grown in control and Cd contaminated soil. Data presented in the graph is the mean of three replicates ± standard error. Similar letters obtained after LSD mean compare test shows non-significant differences at p < 0.05.

Ca2+ ions were also reduced in root and shoot of S. oleracea when exposed to Cd stress. In contrast, MA and TA treatments either alone or in combination effectively overcome this reduction. Like MA1 and MA2 increased Ca2+ ions in root by 11 and 22% while in shoot by 5 and 8%, respectively. Similarly, TA1 and TA2 enhanced Ca2+ ions in root by 28 and 36% while in shoot by 10 and 11%, respectively (Fig. 10C & D).

Cd contamination of soil resulted in significant uptake of Cd heavy metals by roots (352 µg g−1 DW) and its subsequent translocation towards shoot (176 µg g−1 DW) with TF (translocation factor) of 0.5. Further, treatments of MA and TA alone or in combination significantly lowered Cd uptake in roots and its translocation towards shoot (as shown in Table 2).

Pearson’s correlation and principal component analysis

Pearson’s correlation results in the Fig. 11 showed that growth and physiological attributes including RL, RFW, RDW, SL, SFW, SDW, NL, LA, Chl a, Chl b, carotenoids, RWC, Pn, Tr, gs, Ci, SPAD value, ΦPSII as well as nutritional ions (K+ & Ca2+) under the effect of MA and TA foliar spray in S. oleracea plant given Cd stress were positively correlated. Whereas, growth parameters were negatively correlated with biochemical attributes (total phenolics, leaf proline & TSP), stress markers (MDA, H2O2 & RMP), enzymatic antioxidants (CAT, POD, APX & SOD) and Cd concentration in root and shoot of S. oleracea under the effect of MA and TA when given Cd stress or not. Principle component analysis (Fig. 12A & B) revealed that the first two components PC1 and PC2 had the maximum contribution among all explained variances (Fig. 12A). Where PC1 had 59.47% and PC2 had 20.33% contribution. PCA showed that all treatments applied in this study were successfully dispersed in the whole dataset. Results showed that Cd stress (6) had significant effects on growth, photosynthesis related attributes, biochemical parameters, and essential mineral contents of S. oleracea in control or under the treatment of MA and TA supplements.

Pearson’s correlation for all studied parameters of S. oleracea plants treated with foliar spray of malic acid (MA) and tartaric acid (TA) in control and Cd spiked conditions. (Various abbreviations used are as follows; RL; root length, RFW; root fresh weight, RDW; root dry weight, SL; shoot length, SFW; shoot fresh weight, SDW; shoot dry weight, nL; number of leaves, LA; leaf area, Chl; chlorophyll, RWC; relative water content, Pn; net photosynthesis rate, Tr; transpiration rate, gs: stomatal conductance, Ci: intercellular CO2, SPAD; soil plant analysis development value, Fv/Fm; maximum quantum efficiency of PSII, TSP; total soluble proteins, MDA; malondialdehyde, H2O2; hydrogen peroxide, RMP; relative membrane permeability, CAT; catalase, POD; peroxidase, APX; ascorbate peroxidase, SOD; superoxide dismutase, K; potassium, Ca; calcium, Cd; cadmium).

Principle component analysis for all studied parameters of S. oleracea plants treated with foliar spray of malic acid (MA) and tartaric acid (TA) in control and Cd spiked conditions. (A) bar graph for percentage of explained variances, (B) PCA biplot. (Various abbreviations used are same as given in Fig. 11. Dots with numbers 1–12 represented different treatments applied in this experiment. Where; 1 = Control, 2 = 100 µM malic acid, 3 = 150 µM malic acid, 4 = 100 µM tartaric acid, 5 = 150 µM tartaric acid, 6 = 100 µM Cd stress, 7 = 6 + 2, 8 = 6 + 3, 9 = 6 + 4, 10 = 6 + 5).

Discussion

Cadmium (Cd) contamination in agrarian soils constitutes a significant environmental concern42. Cd has the potential to disrupt vital physiological processes in plants, including gas exchange, water utilization efficiency, photosynthesis, and nutrient uptake. Such disruptions may manifest as inhibited growth, chlorosis of foliage, and diminished biomass production43. In the present investigation, it was observed that Cd-induced stress adversely influenced plant growth, morphology, and photosynthetic capability. Cd toxicity resulted in the reduction of leaf size, leaf count, and the relative water content of S. oleracea. Furthermore, existing literature corroborates that Cd adversely affects the growth and developmental processes of various crops, including Triticum aestivum44, Zea mays45, Brassica napus46, and Solanum lycopersicum47. The detrimental impact of Cd stress on plant growth and size may be attributable to impairment of the photosynthetic apparatus and/or alterations in the structural integrity of the plant46. The observed reductions in plant growth and biomass may also stem from oxidative stress, diminished activity of antioxidant enzymes, and/or compromised uptake of essential mineral nutrients47. It is plausible that the observed retardation in plant growth is linked to a deceleration in cellular expansion48. The observed decline in photosynthetic efficiency may result from cadmium’s interference with the enzymatic activities associated with the Calvin cycle and the electron transport chain. Additionally, Cd may disrupt the gaseous exchange mechanisms within the plant system49.

In this investigation, Cd stress was found to diminish the concentration of soluble proteins within the leaves of S. oleracea. This phenomenon may be attributed to heightened oxidative stress induced by Cd toxicity46. Stressful environmental conditions can perturb the equilibrium between the synthesis and degradation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in plants50, resulting in cellular membrane damage and disruption of the membrane system’s integrity and functionality51. Cd toxicity elicited oxidative damage in S. oleracea plant tissues, as evidenced by increased levels of malondialdehyde (MDA), hydrogen peroxide, and electrolyte leakage. Such oxidative effects have also been documented in Brassica napus52 and Brassica juncea53. In addition, the activities of antioxidant enzymes were observed to escalate when plants were subjected to Cd stress. This increase may be indicative of the plant’s activation of defensive mechanisms to mitigate the detrimental impacts of Cd exposure54. Additional studies have indicated that Cd can influence the activity of antioxidant enzymes and modulate the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) across diverse plant taxa54.

Plants synthesize a range of secondary metabolites, including proline, flavonoids, and phenolics, which can confer tolerance to metal toxicity. Proline accumulation is frequently observed as a response to metal-induced stress in various plant species. This accumulation may be implicated in signaling pathways and in mitigating damage to cellular membranes55,56. The accumulation of proline may assist in maintaining cellular water homeostasis and in protecting enzymatic functions, thereby preserving the structural integrity of macromolecules and organelles. Cd stress was observed to elevate the concentration of total phenolic compounds within plants. These phenolic compounds, possess the capacity to scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS) and facilitate the sequestration and translocation of deleterious metals within plant systems57.

Cadmium toxicity markedly diminished the concentrations of calcium (Ca2+) and potassium (K+) in both the roots and shoots of S. oleracea. Reduced K+concentrations in plants subjected to Cd stress may have induced the closure of stomata, thereby impairing photosynthetic activity and gas exchange58. This investigation determined that elevated concentrations of Cd in the soil correspondingly led to a substantial increase in the accumulation of Cd within the roots and shoots of S. oleracea plants. Previous research has also demonstrated that higher soil Cd concentrations can result in augmented Cd levels in the tissues of other species, including Zea mays59, Boehmeria nivea60, and Triticum aestivum61. Plants have developed a range of adaptive mechanisms to regulate the concentration of heavy metal ions in their cellular compartments, thereby averting excessive accumulation62.

Organic chelators are gaining prominence due to their cost-effectiveness and ease of degradation compared to synthetic alternatives, which tend to be expensive and pose environmental contamination risks22. Numerous studies have indicated that organic acids can enhance plant growth and mitigate the detrimental impacts of toxic elements such as chromium63, cadmium54, lead64, copper65, and arsenic66. The application of MA and TA has resulted in improved growth, biomass accumulation, and photosynthetic pigment content in S. oleracea seedlings under Cd stress. Zaheer et al.65 stated that malic acid and tartaric acid have been shown to promote increased chlorophyll production and other pigments while enhancing gas exchange, contributing to improved growth and biomass. As posited by Mallhi et al.67organic acids may enhance plant growth under conditions of metal toxicity by mitigating the harmful effects of metals and augmenting nutrient uptake, likely due to their ability to form complexes with nutrients, thereby facilitating their absorption by plants63.

Organic acids may facilitate the maintenance of photosynthesis in plants by enhancing their capacity to regulate water loss, sustaining the functionality of pivotal enzymes associated with photosynthesis, and preserving the structural integrity of chloroplasts22,68. In this investigation, the application of MA and TA potentially ameliorates the growth of S. oleracea plants under Cd stress by augmenting the synthesis of photosynthetic pigments and optimizing gas exchange processes. In the present study, the administration of MA and TA resulted in improved adaptability of the plants to water absorption and retention, thereby elevating the relative water content within the plant20. This phenomenon may also be associated with the heightened transpiration rates observed in S. oleracea plants under the influence of MA and TA.

In this study, the application of MA and TA augmented the activity of antioxidant enzymes and mitigated oxidative stress. Additional studies have corroborated that organic acids can enhance the activity of antioxidant enzymes in plants experiencing various stress conditions7,8. The incorporation of MA and TA contributed to the alleviation of adverse effects induced by Cd stress in S. oleracea plants by diminishing electrolyte leakage, malondialdehyde (MDA), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) concentrations. Application of organic acids may have facilitated the upregulation of protective enzyme gene expression, such as POD1, Cu/Zn-SOD, and GPX1, thereby enhancing the activities of the respective enzymes7. The findings of this study imply that MA and TA may enable plants to endure Cd-induced oxidative stress by stimulating the activity of antioxidant enzymes and curtailing the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS).

Guo et al.69 documented that application of MA and TA on S. oleracea plants under Cd stress promoted the exudation of organic acids from their root systems. This may represent a mechanism by which plants can confer resilience in Cd-contaminated environments. Organic acid treatments on S. oleracea plants have been shown to enhance tolerance to Cd stress by diminishing the concentration of free Cd ions in the roots and shoots of the plants. This phenomenon may be attributed to the capacity of organic acids to form complexes with Cd, thereby rendering it less bioavailable for uptake by the plants. The addition of MA and TA to S. oleracea plants under Cd stress resulted in a significant reduction of Cd concentrations in both the roots and shoots when compared to plants subjected exclusively to Cd exposure. It is plausible that MA and TA served to protect the cellular membranes, thereby mitigating the accumulation of Cd in various plant tissues. In a related study, Javed et al.70 observed that S. oleracea plants exposed to Cd stress exhibited elevated levels of Cd in their roots and shoots. Nevertheless, the application of ascorbic acid (150 mM) resulted in a significant decrease in the uptake of Cd.

The use of organic acids has shown promising results in enhancing plant resilience, ultimately leading to improved growth and nutrient uptake under heavy metal stress. Results indicate that malic and tartaric acids may play a crucial role in the detoxification processes within plants, facilitating the chelation of Cd ions and reducing their harmful effects on cellular functions. These findings suggest that incorporating malic and tartaric acids into agricultural practices could be a viable strategy for improving crop tolerance to Cd contamination, thereby promoting sustainable food production in affected areas. Further research is needed to explore the optimal concentrations and application methods of these organic acids, as well as their long-term effects on soil health and overall ecosystem balance.

Conclusion

Cd metal contamination of the soil and its accumulation in consumable parts of crop plants especially leafy vegetables is a serious challenge to deal. The use of chelating agent is a useful strategy to avoid heavy metal uptake and accumulation in plants. The results of this study revealed that Cd stress (100 µM) significantly reduced growth attributes, photosynthetic pigments and related parameters and gas exchange attributes. Cd stress also stimulated antioxidant defense mechanism in S. oleracea. Cd stressed plants had elevated levels of Cd metal ions in root and consumable parts (i.e. leaves) and caused severe oxidative damage in the form of increased lipid peroxidation and electrolytic leakage. MA and TA supplements at both low and high levels (100 and 150 µM) effectively reversed the devastating effects of Cd stress and improved growth, photosynthesis and defense related attributes of S. oleracea plants. These supplements also prevented excessive accumulation of Cd metal ions as indicated by lowered Cd metal contents in MA and TA treated plants. These findings demonstrated that MA and TA treatments can potentially reduce heavy metal induced phytotoxicity in plants by reducing its uptake and enhancing photosynthesis and defense related parameters.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Altaf, M. A. et al. Deciphering the melatonin-mediated response and signalling in the regulation of heavy metal stress in plants. Planta 257, 115 (2023).

Kiran, Bharti, R. & Sharma, R. Effect of heavy metals: an overview. Mater. Today Proc. 51, 880–885 (2021).

Waheed, S. et al. Ca2SiO4 chemigation reduces cadmium localization in the subcellular leaf fractions of spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) under cadmium stress. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 207, 111230 (2021).

Yang, Y. & Shen, Q. Phytoremediation of cadmium-contaminated wetland soil with Typha latifolia L. and the underlying mechanisms involved in the heavy-metal uptake and removal. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 4905–4916 (2020).

Latif, J. et al. Unraveling the effects of cadmium on growth, physiology and associated health risks of leafy vegetables. Revista Brasileira De Bot. 43, 799–811 (2020).

Nobaharan, K., Abtahi, A., Asgari Lajayer, B. & van Hullebusch, E. D. Effects of biochar dose on cadmium accumulation in spinach and its fractionation in a calcareous soil. Arab. J. Geosci. 15, 336 (2022).

Zhang, S. et al. Effects of Exogenous Organic acids on cd tolerance mechanism of Salix variegata Franch. Under cd stress. Front. Plant. Sci. 11, 594352 (2020).

Hu, J. et al. Effects of Exogenous Organic acids on the growth and antioxidant system of Cosmos bipinnatus under Cadmium stress. Hortic. Sci. Technol. 40, 459–470 (2022).

Liu, J. X., Zhang, S. Y. & Zhou, J. Effects of Cadmium stress on growth and photosynthetic physiological characteristics of Robinia pseudoacacia seedlings. For. Res. 36, 168–178 (2023).

Haider, F. U. et al. Cadmium toxicity in plants: impacts and remediation strategies. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 211, 111887 (2021).

Liu, W. et al. Effects of EDTA and Organic acids on physiological processes, Gene expression levels, and Cadmium Accumulation in Solanum nigrum under Cadmium stress. J. Soil. Sci. Plant. Nutr. 23, 3823–3833 (2023).

Geng, H. et al. Leaching behavior of metals from iron tailings under varying pH and low-molecular-weight organic acids. J. Hazard. Mater. 383, 121136 (2020).

El-Shanhorey, N. & Barakat, A. Effect of lead and cadmium in Irrigation Water and Foliar Applied Malic Acid on Vegetative Growth, Flowering and Chemical composition of Salvia Splendens plants (B) effect of Cadmium. Sci. J. Flowers Ornam. Plants. 7, 483–499 (2020).

Sethi, S. et al. Malic acid cross-linked Chitosan based hydrogel for highly effective removal of chromium (VI) ions from aqueous environment. React. Funct. Polym. 177, 105318 (2022).

Saavedra, T. et al. Effects of foliar application of organic acids on strawberry plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 188, 12–20 (2022).

Lu, J. et al. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of the aluminum-activated malate transporter gene MdALMT14. Sci. Hortic. 244, 208–217 (2019).

Si, P., Shao, W., Yu, H., Xu, G. & Du, G. Differences in Microbial communities stimulated by Malic Acid have the potential to improve nutrient absorption and fruit quality of grapes. Front. Microbiol. 13, 850807 (2022).

Rekha, K., Baskar, B., Srinath, S. & Usha, B. Plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria Bacillus subtilis RR4 isolated from rice rhizosphere induces malic acid biosynthesis in rice roots. Can. J. Microbiol. 64, 20–27 (2018).

Babayan, B. et al. Tartaric Acid Synthetic Derivatives for Multi-Drug Resistant Phytopathogen Pseudomonas and Xanthomonas Combating. system 4, (2020).

Jamal, A. et al. Investigating the efficacy of tartaric acid and zinc-mediated endogenous melatonin induction for mitigating arsenic stress in Tagetes patula L. Sci. Hortic. 322, 112399 (2023).

Yuan, T. et al. B.-h. Tartaric acid coupled with gibberellin improves remediation efficiency and ensures safe production of crops: a new strategy for phytoremediation. Sci. Total Environ. 908, 168319 (2024).

Chen, F. et al. Unlocking the phytoremediation potential of organic acids: a study on alleviating lead toxicity in canola (Brassica napus L). Sci. Total Environ. 914, (2024).

Zhang, S. et al. Effects of Exogenous Organic acids on cd tolerance mechanism of Salix variegata Franch. Under cd stress. Front. Plant. Sci. 11, 109790 (2020).

Jantwal, A., Durgapal, S., Upadhyay, J., Joshi, T. & Kumar, A. Tartaric acid. in Antioxidants Effects in Health: The Bright and the Dark Side 485–492Elsevier, (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-819096-8.00019-7

Gilani, M. et al. Mitigation of drought stress in spinach using individual and combined applications of salicylic acid and potassium. Pak J. Bot. 52, 1505–1513 (2020).

Zubair, M. et al. Physiological response of spinach to toxic heavy metal stress. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26, 31667–31674 (2019).

Sofy, M., Mohamed, H., Dawood, M., Abu-Elsaoud, A. & Soliman, M. Integrated usage of Trichoderma Harzianum and biochar to ameliorate salt stress on spinach plants. Arch. Agron. Soil. Sci. 68, 2005–2026 (2022).

Yoon, Y. E. et al. Influence of cold stress on contents of soluble sugars, vitamin C and free amino acids including gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in spinach (Spinacia oleracea). Food Chem. 215, 185–192 (2017).

Bashir, S. et al. Role of sepiolite for cadmium (cd) polluted soil restoration and spinach growth in wastewater irrigated agricultural soil. J. Environ. Manage. 258, 110020 (2020).

Aron, D. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts. Plant. Physio. 24, 1–15 (1949).

Lichtenthaler, H. K. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. in Methods in Enzymology vol. 148 350–382 (Elsevier, (1987).

Jones, M. M. & Turner, N. C. Osmotic Adjustment in leaves of Sorghum in response to Water deficits. Plant. Physiol. 61, 122–126 (1978).

Lamuela-Raventós, R. M. Folin-Ciocalteu method for the measurement of total phenolic content and antioxidant capacity. Meas. Antioxid. Activity Capacity: Recent. Trends Appl. 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119135388.ch6 (2017).

Bates, L. S., Waldren, R. P. & Teare, I. D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant. Soil. 39, 205–207 (1973).

Cakmak, I. & Horst, W. J. Effect of aluminium on lipid peroxidation, superoxide dismutase, catalase, and peroxidase activities in root tips of soybean (Glycine max). Physiol. Plant. 83, 463–468 (1991).

Velikova, V., Yordanov, I. & Edreva, A. Oxidative stress and some antioxidant systems in acid rain-treated bean plants protective role of exogenous polyamines. Plant Sci. 151, 59–66 (2000).

Yang, G., Rhodes, D. & Joly, R. J. Effects of high temperature on membrane stability and chlorophyll fluorescence in glycinebetaine-deficient and glycinebetaine- containing maize lines. Aust J. Plant. Physiol. 23, 437–443 (1996).

Chance, B. & Maehly, A. C. [136] Assay of Catalases and Peroxidases. {black Small Square}. Methods in Enzymology vol. 2 (1955).

Nickel, K. S. & Cunningham, B. A. Improved peroxidase assay method using leuco 2,3′,6-trichloroindophenol and application to comparative measurements of peroxidatic catalysis. Anal. Biochem. 27, 292–299 (1969).

Nakano, Y. & Asada, K. Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate-specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts. Plant. Cell. Physiol. 22, 867–880 (1981).

Beauchamp, C. & Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutase: improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 44, 276–287 (1971).

Ma, J. et al. Effect of phosphorus sources on growth and cadmium accumulation in wheat under different soil moisture levels. Environ. Pollut. 311, 119977 (2022).

Rizwan, M., Ali, S., Rehman, M. Z. & Maqbool, A. A critical review on the effects of zinc at toxic levels of cadmium in plants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26, 6279–6289 (2019).

Rehman, M. Z. et al. Effect of inorganic amendments for in situ stabilization of cadmium in contaminated soils and its phyto-availability to wheat and rice under rotation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 22, 16897–16906 (2015).

Vaculík, M., Pavlovič, A. & Lux, A. Silicon alleviates cadmium toxicity by enhanced photosynthetic rate and modified bundle sheath’s cell chloroplasts ultrastructure in maize. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 120, 66–73 (2015).

Ali, B. et al. Physiological and ultra-structural changes in Brassica napus seedlings induced by cadmium stress. Biol. Plant. 58, 131–138 (2014).

Hédiji, H. et al. Impact of long-term cadmium exposure on mineral content of Solanum lycopersicum plants: consequences on fruit production. South. Afr. J. Bot. 97, 176–181 (2015).

Dias, M. C. et al. Cadmium toxicity affects photosynthesis and plant growth at different levels. Acta Physiol. Plant. 35, 1281–1289 (2013).

Singh, P., Singh, I. & Shah, K. Alterations in antioxidative machinery and growth parameters upon application of nitric oxide donor that reduces detrimental effects of cadmium in rice seedlings with increasing days of growth. South. Afr. J. Bot. 131, 283–294 (2020).

Rehman, M. et al. Effects of rice straw biochar and nitrogen fertilizer on ramie (Boehmeria nivea L.) morpho-physiological traits, copper uptake and post-harvest soil characteristics, grown in an aged-copper contaminated soil. J. Plant. Nutr. 45, 11–24 (2021).

Zafar-ul‐hye, M. et al. Effect of cadmium‐tolerant rhizobacteria on growth attributes and chlorophyll contents of bitter gourd under cadmium toxicity. Plants 9, 1–21 (2020).

Jung, H. et al. Ascorbate-mediated modulation of cadmium stress responses: reactive oxygen species and Redox Status in Brassica napus. Front. Plant. Sci. 11, 586547 (2020).

Alam, P. et al. Foliar application of 24-epibrassinolide improves growth, ascorbate-glutathione cycle, and glyoxalase system in brown mustard (Brassica juncea (L.) Czern.) Under cadmium toxicity. Plants 9, 1–24 (2020).

Ehsan, S. et al. Citric acid assisted phytoremediation of cadmium by Brassica napus L. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 106, 164–172 (2014).

Rehman, M. et al. Red light optimized physiological traits and enhanced the growth of ramie (Boehmeria nivea L). Photosynthetica 58, 922–931 (2020).

Sulandjari, Sakya, A. T. & Prahasto, D. H. IOP Publishing, p 12055,. The application of phosphorus and potassium to increase drought tolerance in Pereskia bleo (Kunt) DC with proline and antioxidant indicators. in IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science vol. 423 (2020).

Chen, S. et al. Phenolic metabolism and related heavy metal tolerance mechanism in Kandelia Obovata under Cd and Zn stress. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 169, 134–143 (2019).

Wasaya, A. et al. Evaluation of fourteen bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genotypes by observing gas exchange parameters, relative water and chlorophyll content, and yield attributes under drought stress. Sustain. (Switzerland). 13, 4799 (2021).

Anwar, S. et al. Impact of chelator-induced phytoextraction of cadmium on yield and ionic uptake of maize. Int. J. Phytorem. 19, 505–513 (2017).

Tang, H. et al. Effects of selenium and silicon on enhancing antioxidative capacity in ramie (Boehmeria nivea (L.) Gaud.) Under cadmium stress. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 22, 9999–10008 (2015).

Arshad, M. et al. Phosphorus amendment decreased cadmium (cd) uptake and ameliorates chlorophyll contents, gas exchange attributes, antioxidants, and mineral nutrients in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under cd stress. Arch. Agron. Soil. Sci. 62, 533–546 (2016).

Ali, S. et al. Alleviation of chromium toxicity by glycinebetaine is related to elevated antioxidant enzymes and suppressed chromium uptake and oxidative stress in wheat (Triticum aestivum L). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 22, 10669–10678 (2015).

Afshan, S. et al. Citric acid enhances the phytoextraction of chromium, plant growth, and photosynthesis by alleviating the oxidative damages in Brassica napus L. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 22, 11679–11689 (2015).

Bilal Shakoor, M. et al. Citric acid improves lead (pb) phytoextraction in brassica napus L. by mitigating pb-induced morphological and biochemical damages. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 109, 38–47 (2014).

Zaheer, I. E. et al. Citric acid assisted phytoremediation of copper by brassica napus L. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 120, 310–317 (2015).

Bhat, J. A. et al. Newly-synthesized iron-oxide nanoparticles showed synergetic effect with citric acid for alleviating arsenic phytotoxicity in soybean. Environ. Pollut. 295, 118693 (2022).

Mallhi, Z. I. et al. Citric acid enhances plant growth, photosynthesis, and phytoextraction of lead by alleviating the oxidative stress in castor beans. Plants 8, (2019).

Vega, A., Delgado, N. & Handford, M. Increasing Heavy Metal Tolerance by the exogenous application of Organic acids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 5438 (2022).

Guo, H., Chen, H., Hong, C., Jiang, D. & Zheng, B. Exogenous malic acid alleviates cadmium toxicity in Miscanthus sacchariflorus through enhancing photosynthetic capacity and restraining ROS accumulation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 141, 119–128 (2017).

Javed, S. et al. Cadmium stress mitigation in different cultivars of Spinach (Spinacea Oleracea) with Foliar application of ascorbic acid. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 71, 40 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Authors are thankful to Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2025R393), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2025R393), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AS; Experimentation and Methodology, AAS; Conceptualization, Supervision and Validation, SU; Statistical analysis, writing-original draft preparation, SA & MK; Data curation and Formal analysis and SS & MKG; Resource acquisition and Investigation. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

We declare that the manuscript reporting studies do not involve any human participants, human data or human tissues. So, it is not applicable.

Our experiment follows with the relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shabbir, A., Shah, A.A., Usman, S. et al. Efficacy of malic and tartaric acid in mitigation of cadmium stress in Spinacia oleracea L. via modulations in physiological and biochemical attributes. Sci Rep 15, 3366 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85896-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85896-1