Abstract

Prior studies examined Acidocin 4356’s antibacterial and antivirulence effects against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, including cell membrane penetration abilities. Building on prior research, an in-vitro co-culture of human cells was established to evaluate the selectivity of Acidocin (ACD) by concurrently cultivating human cells and bacterial pathogens. This study evaluated the antibacterial effectiveness of ACD against Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) revealed significant biofilm dispersion at ACD concentrations as low as 1/2 MIC. The cytotoxicity of ACD was evaluated on two human cell lines, Calu-6 and THP-1, using the MTT assay. The IC50 values were 114 µg/mL and 24 µg/mL after a 12-hour treatment duration. In a co-culture model, the IC50 increased to 118 µg/mL, showing greater resilience of THP-1 cells under these settings, mimicking in-vivo conditions. Fluorescent microscopy and flow cytometry analysis confirmed the MTT results, showing ACD’s potent antimicrobial effects and minimal toxicity to human cells, even after 12 h of treatment. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) study revealed that normal Calu-6 cells included papillary outgrowths and microvilli, while infected cells displayed secretory vesicles, indicating an active response to P. aeruginosa infection. The present study thus serves as a critical step toward the development of an innovative therapeutic strategy targeting biofilm-associated infections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One of the most significant advances in contemporary medicine is the use of antibiotics to treat bacterial infections. However, since the invention of antibiotics, the evolution of antibiotic resistance has posed a significant threat to human health. Antibiotic misuse or overuse has increased antibiotic resistance and the rate of mortality brought on by multidrug-resistant bacteria since the COVID-19 crisis began five years ago1. Hospital infections frequently involve the ESKAPE pathogens that include six nosocomial pathogens Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter spp. The great propensity of ESKAPE bacteria to breed resistance has made treating severe infections more difficult and increased infection mortality2. The development of bacterial biofilm is one method employed by these bacteria to avoid being successfully treated by antimicrobial drugs3. In contrast to planktonic cells, bacteria in biofilm formations exhibit a 10-1000-fold increase in antibiotic resistance4,5. The presence of P. aeruginosa in the airways of cystic fibrosis patients or infections caused by S. aureus and A. baumannii contaminating medical types of equipment are examples of how bacterial biofilms have a significant impact on chronic infections2. A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa are priority pathogens on the WHO list that are difficult to treat and eliminate using new antibiotics6. Natural products have been regarded as potential therapeutic agents against pathogenic microorganisms ever since the development of antibiotics. However, the growing number of diseases caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria emphasizes the vital need to develop novel antimicrobial medicines in modern medicine. Indisputably, the most promising strategy to combat the antibiotic resistance crisis involves the use of compounds derived from natural structures7. In this regard, the use of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) as next-generation antibiotics has attracted the attention of researchers. Unlike conventional broad-spectrum antibiotics, which can disrupt the host microbiome and accelerate antibiotic resistance, AMPs offer a more targeted approach. This selectivity not only lowers the likelihood of resistance development but also minimizes disruptions to the commensal microbiota, preserving its vital function in human health and development7. These AMPs are broad-spectrum therapeutic agents that target fungi, bacterial biofilms, and the ESKAPE group of bacteria8. Because they target the bacterial cell membrane, these substances are more effective and have fewer side effects than chemical ones. They also exhibit a lower level of bacterial resistance when used as antibiotic alternatives9. The side effects of AMPs, which include toxicity to mammalian cells and hemolytic activity, are one issue restricting their therapeutic application10. Many businesses have commercialized AMPs and peptidomimetics; however, due to their toxicity towards mammalian cells, their use has been limited to topical treatments11. Current cell culture procedures do not accurately represent in-vivo situations, including intercellular communication, because they solely consider a particular type of cell12. Co-cultivation of many cell lines can mimic the situation of the lung epithelium, composed of different cell types. Co-culture with alveolar macrophages, which produce substantial amounts of biological chemicals (oxygen radicals, growth-regulating proteins, or protease) in lung injuries, has been considered in recent studies as a method to assess toxicity13. The therapeutic effects of a bioactive drug should normally occur at concentrations lower than those that injure the host cells14. The concentration of AMPs in antimicrobial and toxicity assays is quite varied, and in-vitro evaluation of AMPs’ antimicrobial activity and toxicity is carried out in independent tests under different circumstances15. As a result, investigating the antimicrobial activity and toxicity of AMPs in settings where bacteria and human cells are co-cultured can be regarded as an appropriate screening method to ascertain their effectiveness. In a previous study, a novel AMP, designated as ACD, was isolated from the probiotic bacterium Lactobacillus acidophilus ATCC 4356 with a molecular weight of 8.3 kDa16. Its capacity to disrupt membranes appears to be mostly dependent on its amphiphilic characteristics. The structure of ACD includes numerous positively charged and hydrophobic amino acids, allowing it to adopt a three-dimensional amphiphilic conformation, and is necessary for interacting with bacterial membranes. The peptide sequence also comprises a GXXXG motif, a structural feature implicated in helix-helix interactions and membrane penetration16. These properties contribute to ACD’s dual function as an antibacterial and anti-virulence agent. Its stability against proteolytic degradation highlights its therapeutic potential, especially for biofilm-associated and respiratory infections. To evaluate the antibacterial properties of ACD peptide, it was tested against P. aeruginosa. The therapeutic effect of this peptide was also confirmed in vivo using a mouse model infected with P. aeruginosa16. Notably, ACD displayed antimicrobial efficacy in a variety of physiological circumstances while exhibiting minimal hemolytic activity at high concentrations, making it a promising candidate for restricting the establishment and development of P. aeruginosa biofilms. However, uncertainty persisted regarding the AMP’s range of activity and its impact on different mammalian cells16. To address this, the anti-biofilm activity of ACD against some pathogens from the ESKAPE group was assessed and contrasted using P. aeruginosa in the initial phase of this investigation. Then, using coculturing the THP-1 and Calu-6 cell lines, a lung cell model was developed that mimics the conditions possibly representing lung epithelial environments. The toxicity of ACD on these cell lines was subsequently investigated and evaluated separately for each mono-cultured cell line. Additionally, an in-vitro infection model was developed involving co-cultured Calu-6 lung epithelial cells with each of the selected bacteria from the ESKAPE group. The goal was to test ACD’s antimicrobial activity under more realistic circumstances, assess its impact on human cells, and determine how selective it was against bacteria compared to human cells.

Results

Antimicrobial properties of ACD against planktonic forms of bacteria

The first set of pathogens against which we examined the antibacterial activity of ACD was the ESKAPE group of bacteria, which includes Enterobacter spp., E. faecium, S. aureus, K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii, and P. aeruginosa. Semi-purified ACD peptide could prevent all these bacteria from growing at a dose of 100 µg/mL. However, as Fig. 1a illustrates, A. baumannii was more susceptible to its effects. Therefore, P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii were selected as indicator bacteria for further investigation because the impact of ACD on P. aeruginosa was demonstrated in the prior work16. Using the optical density (OD) measurement and fluorescein diacetate (FDA) assay to define cell viability, the minimum inhibitory concentration of 90% (MIC90) and minimum inhibitory concentration of 50% (MIC50) values for ACD were determined (Table 1; Fig. 1b). For A. baumannii, the MIC50 values were found to be 70.51 µg/mL and 79.79 µg/mL, as determined via the OD measurement and FDA staining procedure, respectively. Using the same methods, the MIC50 values for P. aeruginosa were found to be 87.85 µg/mL and 86.38 µg/mL. Figure 1b illustrates a linear and direct association between the rise in peptide concentration and the suppression of growth for both bacterial strains, with a significantly greater level of inhibition noted for A. baumannii compared to P. aeruginosa.

Antimicrobial activity and minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) determination of ACD against ESKAPE pathogens. (a) Evaluating the antimicrobial effects of semi-purified ACD (at a concentration of 100 µg/mL) on the growth of various bacteria from the ESKAPE group. Notably, A. baumannii showed a heightened sensitivity to ACD. The data are based on three independent experiments. **0.001 > P < 0.01, *0.01 > P < 0.05. (b) Determination of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of ACD against P. aeruginosa using (i) the OD600 method, and (ii) the fluorescence method, and determination of the MIC of ACD against A. baumannii using (iii) the OD600 method, and (iv) the fluorescence method. The figure illustrates a direct linear relationship between the increase in peptide concentration and the inhibition of bacterial growth. The data is derived from three independent experiments.

Antibiofilm activity of ACD peptide

The anti-biofilm properties of the ACD peptide were examined using three different techniques: electron microscopy, confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM), and crystal violet staining (Figs. 2 and 3). The crystal violet staining results showed that both bacteria’s biofilm biomass was reduced in response to different concentrations of MIC and 2MIC as well as a low concentration of ACD, i.e. 1/2MIC (Fig. 2a). It is worth noting that both bacteria appear to lose more biomass at 1/2MIC than at MIC. Figure 3 displays FE-SEM images of P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii following treatment with ACD at different concentrations. The P. aeruginosa control sample exhibits a biofilm with a homogenous and thick structure (Fig. 3a.i). Most of the cells are in their normal state, and the biofilm’s sturdy structure is visible. In the sample treated with 1/2MIC concentration, P. aeruginosa bacteria are in separate clusters, with large cavities observed between these cellular groups (Fig. 3a.ii). However, most cells in this sample remain intact and alive. In the P. aeruginosa sample treated with MIC concentration, unlike the 1/2MIC concentration, the biofilm’s continuous structure is preserved in many areas, and cellular connections remain intact (Fig. 3a.iii). Nevertheless, a greater number of deformed and degraded cells can be observed compared to the 1/2MIC concentration. In the samples exposed to 2MIC concentrations, the bulk of the biofilm cells and the biofilm architecture have been obliterated, resulting in only a few cells remaining on the surface (Fig. 3a. iv). The A. baumannii control samples demonstrate a unified, interconnected perspective on biofilm construction (Fig. 3b.i). The bacteria formed a hollow biofilm, and the cells resembled coccobacilli. The samples treated with the peptide at 1/2MIC concentration demonstrated that the cells were separated from one another, even though many deformed cells were not apparent, and the cells were not completely detached from the surface. The continuous structure of the biofilm no longer existed and most of the cells had separated into individual cells (Fig. 4b.ii). At MIC concentration, the cell density is surprisingly higher than that of the samples treated with 1/2MIC peptide concentration, even though the dispersion of the biofilm structure and the distances between the biofilm clusters are evident and increased in comparison to the control (Fig. 3b.iii). The number of cells was significantly reduced, and no cell-to-cell interactions were observed in the samples treated with 2MIC peptide concentrations (Fig. 3b.iv).

Effects of ACD on biofilm biomass and structure of P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii. (a) Crystal violet staining of biofilm biomass for both bacteria, (i) A. baumannii and (ii) P. aeruginosa, in response to different concentrations of ACD of 1/2MIC, MIC, and 2MIC. Three separate experiments were conducted, each with three replicates. (b) Three-dimensional Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) images demonstrating the effects of ACD on the biofilm structure and cell membrane integrity of P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii at varying concentrations (1/2MIC, MIC, and 2MIC). The live cells are stained green, while dead cells are stained red. (i) Control images for both bacteria show an integrated biofilm structure with green-colored cells. (ii) Upon treatment with 1/2MIC concentration of ACD, red cells become visible in both bacterial species, indicating membrane damage and PI dye uptake. (iii) At MIC concentration, the number of red cells increases with a higher red cell population in P. aeruginosa compared to A. baumannii. (iv) The 2MIC concentration results in an almost entirely red biofilm for both bacterial species, indicating extensive membrane damage and a high level of PI dye uptake. For the CLSM analysis, two fields of view were examined for each condition.

Effect of ACD on P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii biofilms. FE-SEM microscopic images illustrating the differential effects of ACD on the biofilm structure and cell-to-cell connections of P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii at varying concentrations (1/2MIC, MIC, and 2MIC). (a) Effect of ACD on P. aeruginosa (i) The control image displays homogeneous biofilm structure, (ii) Treatment with 1/2MIC concentration of ACD reveals the biofilm that lost its continuous structure, although most cells remain healthy, (iii) At the MIC concentration, the biofilm structure is still present. However, there is a noticeable increase in distorted and killed cells compared to the 1/2MIC treatment. (iv) Treatment with 2MIC concentration results in a significant disruption of the biofilm structure, leaving only a few cells remaining on the surface. (b) Effect of ACD on A. baumannii bacteria: (i) The control image shows a cohesive, interconnected biofilm structure with coccobacilli-shaped cells. (ii) Upon treatment with 1/2MIC concentration of ACD, the continuous biofilm structure begins to disappear, with cells becoming separated and fewer distorted cells visible. (iii) At the MIC concentration, the biofilm structure is further dispersed, with increased distances between biofilm clusters and a surprisingly higher cell density compared to the 1/2MIC treatment. (iv) The 2MIC concentration results in a drastic reduction in cell numbers, with no visible cell-to-cell connections. An average of six fields of view were examined for each condition.

Comparison of the MTT assay representing treatment toxicity of ACD on Calu-6 and THP-1 cell lines in monoculture and co-culture settings. (a) A comparative overview of the viability across Calu-6, THP-1 and co-culture of Calu-6 and THP-1. ACD has no significant impact on cell viability at 20 µg/mL. ACD toxicity begins at 40 µg/mL for both cell lines under monoculture settings, with a higher impact on THP-1 cells. The ensuing figures are designed with a focus on determining the MIC50.The cell viability of (b) Calu-6 cell line, (c) THP-1 cell line, and (d) the co-culture of Calu-6 and THP-1 cells upon treatment with different concentrations of ACD. Co-culture conditions reveal an increase in overall cell viability, with IC50 values for THP-1 and Calu-6 cells rising to 118 µg/mL in co-culture from their respective values of 24 µg/mL and 114 µg/mL in monoculture. The results are based on three separate trials, with three replicates for each variation. ***P ≤ 0.001, **0.001 > P < 0.01, *0.01 > P < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA, significant difference from the control group).

The results obtained from CLSM analysis are shown in Fig. 2b. In control samples, it is evident that both bacteria have an integrated biofilm structure with green-colored cells (Fig. 2b). The cells whose membranes have been affected by the peptide and rendered permeable to PI red dye are represented by the red cells in the samples treated with ACD peptide. Regarding the two bacteria, cells with red colors can be observed in the samples that were treated with a 1/2MIC concentration (Fig. 2b.ii). However, the quantity of red cells in the samples treated with MIC concentration of peptide is higher (Fig. 3b.iii). With the higher inhibition of A. baumannii biofilm in the crystal violet staining method, it is worthy of consideration that the red cell population is higher among P. aeruginosa than in A. baumannii. Both bacteria treated with 2MIC ACD concentrations have nearly completely red-colored biofilms (Fig. 5b.iv).

Comparative analysis of ACD toxicity on Calu-6 and THP-1 cell lines in monoculture and co-culture conditions using fluorescent microscopy. The figure presents microscopic fluorescent images of viability analysis of Calu-6 and THP-1 cell lines in monoculture and co-culture conditions, stained with FDA-PI dyes, after treatment with different concentrations of ACD. The green cells represent live cells, while the red cells indicate dead cells. The figure underscores the differential response of the cell lines to ACD concentrations and the protective effect of co-culture, especially for THP-1 cells which confirms the findings from the MTT assays.

Examining the cytotoxicity of ACD

The cell viability was investigated at different concentrations of ACD peptide in monocultures and co-cultures of THP-1 and Calu-6 cell lines using the MTT method. Figure 4 depicts the toxicity of ACD against Calu-6 and THP-1 cell lines starting from a concentration of 40 µg/mL. However, the extent of this toxicity is much higher in the THP-1 cell line than in Calu-6, with viability reaching less than 30%, while it is over 80% in Calu-6 (Fig. 4a). It is noteworthy that the co-culture of THP-1 cells with Calu-6 leads to an increase in the overall cell viability and IC50 for THP-1 and Calu-6 cells, which were respectively 29.8 and 114.04 µg/mL, increased to 118.01 µg/mL in co-culture (Fig. 4b-d). While the survival rate of Calu-6 cells in monoculture is significantly different from co-culture in some concentrations, the almost three-fold increase in the survival rate of co-cultured cells compared to THP-1 monoculture indicates a significant improvement in the survival of THP-1 cells in co-culture after treatment with ACD.

Calu-6 and THP-1 cell survival in both monoculture and co-culture situations was investigated using a fluorescence microscope with FDA-PI double staining after 12 h of first ACD peptide administration, as improved cell viability turned out in the co-culture condition. Figure 5 shows that all cells in the control samples (no treatment) are alive and green. At a dose of 20 µg/mL, no toxicity was observed in any of the cell lines. The viability of THP-1 cells is dramatically reduced at a concentration of 60 µg/mL. At a 100 µg/mL ACD concentration, THP-1 cells were almost entirely dead, while Calu-6 cells in monoculture typically looked green and alive with a few red cells. In the co-culture condition, the number of dead cells at an ACD dose of 100 µg/mL was significantly lower, with more than 70% alive and few dead cells apparent. This was substantially lower than the number of dead THP-1 cells in monoculture mode. This also suggests that THP-1 cell survival is much higher in co-culture over monoculture. Both cell lines lost their viability in monoculture and co-culture conditions at ACD concentrations of 160 µg/mL or above (Fig. 5). These findings were further corroborated by cell counting using Trypan blue staining and a hemocytometer (data not shown).

During the initial hours after treatment, flow cytometry analysis using FDA-PI double staining was employed to carefully examine the viability of both cell types in co-culture, as compared to monocultures. Two distinct cell populations were isolated by centrifugation, using ideal conditions for the buoyancy of THP-1 cells and the adhesive properties of Calu-6 cells. In Fig. 6, the results of flow cytometry analysis regarding the viability of each cell type after 3 h of treatment with 60 µg/mL ACD (the first hour after treatment when the difference in population survival between monoculture and co-culture conditions was noticeable) are presented. Similar experiments were conducted on monocultures treated with the ACD peptide. Figure 6a shows that in THP-1 cells, the cell population whose membrane has become permeable to PI in the mono-culture state differs significantly from the untreated cells, highlighting that ACD tends to be deleterious in this condition. However, in co-cultures treated with ACD, there was no significant difference in the dead cell population, and the toxicity was reduced compared to monocultures. ACD treatment of Calu-6 cells after three hours had no toxicity against the cells, and as expected, there was little difference in cell survival between the treated and control groups in both monoculture and control models (Fig. 6a). Figure 6b depicts the flow cytometry data, which supported the pattern observed in the MTT assay (Fig. 4). The results of both experiments demonstrate that THP-1 cells do not survive as well in monoculture settings as they do in co-cultures. However, there was no change in Calu-6 cell survival between monoculture and co-culture.

Comparative Analysis of the toxicity of ACD at 60 µg/mL concentration on Calu-6 and THP-1 cell lines in monoculture and co-culture conditions following a 3-hour treatment period. (a) Flow cytometry chart depicting the toxicity of ACD on Calu-6 and THP-1 cell lines in co-culture and monoculture conditions. While Calu-6 cells show no significant difference in viability between co-culture and monoculture, THP-1 cells exhibit enhanced viability when treated with ACD in co-culture compared to monoculture. (b) Comparing the viability of Calu-6 and THP-1 cells in monoculture and co-culture conditions. There is a significant difference between THP-1 treated in monoculture condition and control, THP-1 treated in monoculture condition, and THP-1 treated in co-culture condition. No significant difference is observed in Calu-6 cell survival between the two conditions. The data are based on three independent experiments, and two replicates were used for each variation. **0.001 > P < 0.01, *0.01 > P < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA).

Selectivity and effectiveness of ACD in an in-vitro infection model

After ensuring the reduction of toxicity under conditions of the simultaneous presence of two cell lines treated with ACD, the peptide’s ability to inhibit bacteria was also investigated in an in-vitro infection model, including Calu-6 cells co-cultured with each of the P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii (Fig. 7). Figure 7a shows the results of counting bacterial cells treated with ACD after 12 h in an in-vitro infection model. As it is clear from the figure, ACD at a concentration of 20 µg/mL does not show toxicity against Calu-6 and THP-1 cells in monoculture mode (Fig. 4), causing a significant reduction in the number of bacteria by almost 2–3 times (Fig. 7a). The preliminary analysis of the data obtained confirmed the effectiveness of ACD in inhibiting the growth of both P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii bacteria while not being toxic to human cells in this model. In the following, the selectivity of ACD towards bacterial cells compared to human cells was further investigated by simultaneously measuring the viability of bacterial and human cells in an in-vitro infection model using flow cytometry analysis. Figure 7b, c illustrates the results acquired from flow cytometry analysis in the P. aeruginosa-infected model, as well as the quantitative diagram of this analysis, respectively. As can be seen, treatment of human cells with ACD at different concentrations for 3 h did not affect their survival. The reason behind selecting a 3-hour treatment duration for this experiment is primarily because it marks the earliest time point at which the effect of ACD on bacteria could be distinctly discerned. Meanwhile, the concentration of 60 µg/mL significantly inhibited the growth of P. aeruginosa bacteria, so at a concentration of 100 µg/mL, almost half of the bacterial cells lost their integrity to PI.

Investigation of the selectivity effects of ACD in an in-vitro infection model. (a) The viability of P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii co-cultured with Calu-6 cells after a 12-hour treatment with ACD. Bacterial viability was assessed by counting the bacterial cells. At a concentration of 20 µg/mL, ACD effectively reduces bacterial counts in both species by approximately 2–3 folds, without exhibiting toxicity against Calu-6 cells. (b) Flow cytometry analysis of Calu-6 cells co-cultured with P. aeruginosa, treated with increasing concentrations of ACD for 3 h. The viability of Calu-6 cells remains unaffected across all concentrations of ACD, while the percentage of dead P. aeruginosa bacteria increases with higher concentrations of the peptide. In the infected model (i), P. aeruginosa maintains high viability. Treatment with ACD at 20 µg/mL concentration (ii) does not significantly alter P. aeruginosa viability. However, with increasing concentrations (iii,iv), P. aeruginosa viability progressively reduces. (c) Quantitative chart representing the viability of Calu-6 cells and P. aeruginosa bacteria treated with different concentrations of ACD (20, 60, and 100 µg/mL). The chart highlights that the viability of Calu-6 cells remains consistent across all concentrations, while the viability of P. aeruginosa bacteria decreases significantly at concentrations of 60 µg/mL and 100 µg/mL. The data are based on three independent experiments, and three replicates were used for each variation. **0.001 > P < 0.01, *0.01 > P < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA, significant difference from the control group).

Figure 8 depicts the results of flow cytometry analysis revealing the simultaneous effect of ACD on A. baumannii and Calu-6, as well as its quantitative examination. As can be seen, all concentrations of ACD caused a significant decrease in the bacterial population, while it did not affect the survival of Calu-6 cells (Fig. 8). Overall, flow cytometry analyses in an in-vitro infection model confirmed the peptide’s selectivity for bacterial cells over eukaryotic cells.

Selective inhibition of A. baumannii by ACD in an in-vitro infection model co-cultured with Calu-6 cells. (a) Flow cytometry analysis of Calu-6 cells and A. baumannii treated with increasing concentrations of ACD for 3 h. The viability of Calu-6 cells remains unaffected across all concentrations of ACD, while the percentage of dead A. baumannii bacteria increases with higher concentrations of the peptide. (i) The infected model (no treatment) presents a certain level of A. baumannii viability. (ii) Application of 20 µg/mL ACD initiates a reduction in A. baumannii viability. (iii) Increasing the concentration to 60 µg/mL ACD continues to maintain a similar reduction in viability as seen with the 20 µg/mL dosage. (iv) With a higher concentration of 100 µg/mL ACD, there is a significant decrease in A. baumannii viability, indicating a heightened bacterial death rate with increased ACD concentration. (b) Quantitative chart representing the viability of Calu-6 cells and A. baumannii bacteria treated with different concentrations of ACD (20, 60, and 100 µg/mL). No statistically significant difference is observed in Calu-6 cell viability across all treatment groups. However, significant differences are observed in A. baumannii viability when treated with ACD concentrations of 20 µg/mL (p-value: 0.037), 60 µg/mL (p-value: 0.044), and 100 µg/mL (p-value: <0.001) compared to the control. The results are based on three separate trials, with three replicates for each variation. ***P ≤ 0.001, **0.001 > P < 0.01, *0.01 > P < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA, significant difference from the control group).

P. aeruginosa was used in the following experiment to validate the effectiveness and selectivity of ACD peptide. Although ACD at 60 µg/mL was shown to be toxic to Calu-6 cells after 12 h in monoculture mode (Fig. 4), the effect of this peptide concentration on Calu-6 cells and P. aeruginosa was also investigated after 12 h of treatment in a co-culture infection model (Fig. 9). Although fewer than 20% of bacteria remained alive (Fig. 9a), the Calu-6 cell population showed no noticeable changes (Fig. 9b). Indeed, this result shows that the peptide effectively inhibits P. aeruginosa cells in the infection model, and it does so without causing adverse effects on Calu-6 cells even after 12 h of treatment.

Selective toxicity of ACD against P. aeruginosa in a co-culture infection model with calu-6 cells using flow cytometry analysis. (a.i) Flow cytometry analysis illustrating the impact of a 12-hour treatment with 60 µg/mL ACD on P. aeruginosa. The treatment results in a substantial decrease in bacterial viability, dropping to 11.8% from over 70% in the untreated infected model. (a.ii) Quantitative chart representing the statistically significant reduction in P. aeruginosa viability after a 12-hour treatment with ACD (p-value: 0.018). (b.i) Flow cytometry analysis of Calu-6 cells under three conditions: control (absence of bacteria and treatment), infected (presence of bacteria but absence of treatment) and treated (presence of both bacteria and ACD treatment). The analysis reveals a consistent viability across all conditions, even with the 60 µg/mL ACD treatment for 12 h. (b.ii) Quantitative chart showing no statistically significant difference in Calu-6 cell viability across the three conditions, highlighting the selective toxicity of ACD against P. aeruginosa without affecting the human cells. The data are based on two independent experiments, and two replicates were used for each variation. *0.01 > P < 0.05 (t-test, significant difference from the control group).

TEM analysis of Calu-6 cells in an in-vitro infection model

Achieving a thorough investigation was the primary objective of TEM analysis. TEM images demonstrated that control Calu-6 cell samples displayed longer and more numerous microvilli than the cells subjected to P. aeruginosa alone, or cells exposed to bacterial cells with ACD peptide. Interestingly, P. aeruginosa-infected cell samples exhibited more secretory vesicles and secreted more mucus around the cells than the Calu-6 cells infected with P. aeruginosa plus ACD peptide and control samples. The papillary outgrowths observed at control Calu-6 cells and P. aeruginosa-infected cells appear more numerous than those of Calu-6 cell samples infected with P. aeruginosa plus ACD peptide (Fig. 10).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis of Calu-6 cell line under different conditions. Control: Control samples of Calu6 cells cultivated alone. Infected model: Calu6 cells infected with P. aeruginosa. Treated: Calu6 cells infected with P. aeruginosa and treated with 100 µg/mL of ACD for 4 h.

Discussion

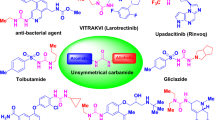

Each year, antibiotic-resistant bacteria cause hundreds of deaths. Certain Gram-negative bacteria, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, have a high level of inherent resistance to a wide range of antibiotics17. Both innate and acquired antibiotic resistance mechanisms, such as biofilm formation and multidrug-resistant persistent cells, are necessary for P. aeruginosa to develop drug resistance18. Consequently, the development of new antimicrobial compounds is needed to replace or combine with antibiotics17. Antibacterial peptides have become increasingly popular as alternatives to conventional antibiotics in recent years due to their broad antimicrobial activity, membrane targeting strategies, rapid killing, and rarely the emergence of antibiotic resistance19. Furthermore, antimicrobial agents can be developed with an emphasis on anti-biofilm properties because of the diverse functional properties of AMPs20. We have previously shown that ACD inhibits the growth of P. aeruginosa in both planktonic and biofilm forms. The ability of ACD peptide to prevent Pseudomonas infections was further demonstrated by additional research employing a mouse model16. The antibacterial activity of ACD was investigated in the current study against additional pathogens of the ESKAPE group in addition to its toxicity and selectivity towards bacterial cells as a possible cause of a significant number of hospital infections. The results of this study confirmed that ACD has antibacterial effects against bacteria belonging to the ESKAPE group. This peptide, however, showed better activity against P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii. Therefore, these microorganisms were selected for further analysis. Contrary to the dual function of AMPs (growth or a lack of growth), the anti-biofilm effects have varying degrees, such as preventing the initial attachment of microbial cells, inhibiting the maturation of the biofilm, destroying the already-formed biofilm, or spreading the cells within the biofilm20. Acidocin 4356, a bacteriocin peptide that disrupts biofilms, was demonstrated in the present study to function similarly to nisin A in terms of disrupting the plasma membranes and biofilm structure of A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa20.

Our findings showed that ACD induces biofilm dispersion and destruction at concentrations below MIC, in contrast to the traditional antibiotic compounds, which require concentrations of 10 to 1000 times higher to act against biofilm as effectively as inhibiting planktonic cells21. However, the antimicrobial, and anti-biofilm capabilities of host defense peptides are considered two distinct processes to the point that anti-biofilm peptides are occasionally categorized apart from AMPs. For instance, at concentrations lower than those necessary for planktonic cells, certain host defense peptides, such as Indolicidin and LL-37, demonstrate anti-biofilm properties20. Nevertheless, some peptides exhibit both antibacterial and anti-biofilm properties, such as Hylin-a1 and its analogs targeting A. baumannii22, and the K6 peptide which is effective against P. aeruginosa and S. aureus23. In both P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii, the ACD biofilm inhibition test showed biofilm destruction at all three concentrations of 1/2MIC, MIC, and 2MIC. This is contrary to other peptides, such as Lyronne and P15s, which show no biofilm degradation ability even at a concentration as high as 3MIC24. At a concentration of 1/2MIC, this peptide destroys the biofilm but still cannot completely prevent the proliferation of planktonic cells. Indeed, it was found that intact biofilms disintegrate more efficiently at a concentration of 1/2MIC than at the MIC. Hence, unlike the relationship between the peptide’s activity against planktonic cells, there was no linear association between the anti-biofilm activity of ACD peptide and its concentration. Compared to AMPs like ZY425 and LI1426, which typically exhibit linear anti-biofilm effects, ACD demonstrates non-linear anti-biofilm action. Biofilm dispersion and destruction occur even at 1/2MIC concentration of ACD peptide, which is much lower than a 2MIC concentration but unexpectedly higher than the samples treated with MIC concentration, as evidenced by electron microscopy analysis and crystal violet staining. However, in contrast to the sample treated with 1/2MIC concentration, the sample treated with MIC concentration contained noticeably more dead cells, according to the results of the CLSM examination. It might be speculated that at lower concentrations, ACD appears to be able to remove living cells from the biofilm matrix, but as the concentration rises, it promotes cell death, killing many connected cells. An earlier study on the anti-biofilm function of peptide 1018 revealed that at concentrations that cannot prevent the growth of planktonic cells, it destroys the mature biofilm, while concentrations that are too low lead to the biofilm dispersal and higher concentrations result in the death of attached cells27. Intriguingly, the treatment of the three-day biofilm with ACD at MIC concentration resulted in a similar reduction in biomass as seen with a 1/2MIC concentration. Considering that the formation of P. aeruginosa ATCC 27,853 biofilm is complete in 18 to 24 h after cultivation, it seems that at this time, the MIC concentration treatment was not able to kill the living cells in the biofilm and destroy the biofilm structure, while the three-day biofilm, where the rate of biofilm formation decreases, this peptide concentration could decrease biofilm biomass as well. The selectivity and cytotoxicity of membrane-active AMPs toward mammalian cells present a fundamental challenge for advancing these agents into clinical studies28. To overcome this challenge, the development of hybrid synthetic peptides has been proposed as a new strategy for designing novel peptides with improved selectivity against bacterial cells19. It implies that AMPs can eradicate microorganisms without significantly harming the host cells. This assumption is supported by laboratory findings showing AMPs are non-hemolytic against different microbes at concentrations much higher than the MIC11. For example, modified forms of the BiF peptide exhibit minimal hemolytic activity even at concentrations far exceeding the MIC29. Similarly, ACP demonstrates non-hemolytic properties against host cells and is effective against Candida albicans yeast, aligning with these findings30. The treatment with ACD concentrations higher than 3MIC in our previous investigation resulted in 20% hemolysis, demonstrating the peptide cell selectivity16. Following the findings that ACD was not toxic to human erythrocytes, ACD activity was examined in an infected mouse model, and in-vivo analysis confirmed the peptide’s ability to treat Pseudomonas pulmonary infection with no significant tissue damage in lung cells16. It was therefore expected that this peptide would not be particularly toxic to human cells. Unexpectedly, ACD displayed toxicity against human cells, particularly THP-1, at MIC50 concentration (79.79 µg/mL), which prevented the growth of half the bacteria. The ACD peptide is more toxic to THP-1 cells than epithelial cells, which may be explained by the fact that THP-1 cells have a higher capability for internalizing peptides than epithelial cells31. It was unexpected that the outcomes of our two recent studies on the application of ACD revealed a substantial difference between hemolysis and toxicity to other human cells14. This has led to the elaboration of three hypotheses. First, 5 × 105 cells/mL were used for the toxicity test, and 2 × 106 CFU/mL (four times the number of cells in the toxicity test) were used to evaluate the antibacterial activity. Consequently, if the compound in question does not have specific cell selectivity, the concentration of the peptide required to kill the bacteria is expected to be at least four times the concentration necessary, regardless of the proliferation and rapid increase in the number of P. aeruginosa cells, compared to eukaryotic cells. While the concentration of MIC90 and IC50 is almost the same, indicating the lower toxicity of this peptide against eukaryotic cells, the study of toxicity by measuring cell viability is assumed to be only an experimental observation (experimental illusion). However, due to the confluence of 100% of Calu-6 cells, which includes 5 × 104, it was not possible to examine this issue. Secondly, for cytotoxicity screening of different drug formulations for pulmonary applications, different respiratory cells with varied purposes would be used to more appropriately achieve the in-vivo performance of the compound of interest. As a result, the selection of each of the different cell lines for toxicity studies will have a different outcome, and at the same time, all the in-vivo conditions are not to be considered. Therefore, in this study, the toxicity study was conducted in both monoculture and co-culture compared to each other. Thirdly, in many previous studies, cell selectivity was measured using the Therapeutic Index (TI) method, and cytotoxicity was evaluated solely on specific cell types, such as macrophages12 and the lung fibroblast MRC-5 cell line29, often overlooking the simultaneous analysis of co-cultured mammalian cells and bacteria. This means that a comparative assessment to understand the peptide’s selectivity attachment under these co-existing conditions was missing. A higher selectivity of bacteriocins toward cancer cells compared to normal cells was previously reported32. As per Bobone and Stella’s14 findings, there seems to be a correlation between the selectivity of AMPs against bacteria and their co-cultivation with mammalian cells. However, this is the first documented case of an AMP exhibiting higher selectivity against bacteria than human cells. This novel observation also highlights the complexity of AMP interactions within mixed cellular environments, particularly in the context of therapeutic applications. The differential selectivity observed in ACD emphasizes the importance of evaluating AMPs not only in isolation but also in co-culture models that better mimic the physiological conditions experienced during infections. Such models provide crucial insights into the nuanced behavior of AMPs, including potential off-target effects that could arise in clinical settings.

Limitations and future directions

Notwithstanding the encouraging results of this study, many limitations must be recognized to contextualize the conclusions drawn and to underscore potential avenues for further investigation. While ACD displayed significant antimicrobial and anti-biofilm action against P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii, its efficacy against other members of the ESKAPE group has yet to be identified, underscoring the need for further investigations to examine its broader therapeutic potential. Furthermore, all experiments were performed under in-vitro circumstances, which, although offering controlled contexts for mechanistic investigations, do not entirely mimic the complexity and variety of in-vivo systems. Consequently, subsequent research utilizing animal models or other clinically pertinent in-vivo environments is essential to confirm the efficacy and safety of ACD as an antibacterial agent. Likewise, although our findings indicate that ACD has non-linear anti-biofilm activity, the molecular processes behind this phenomenon are unknown, necessitating more extensive research to determine how ACD interacts with biofilm components and bacterial signaling pathways. The long-term implications of ACD treatment also remain unexplored, particularly the potential for P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii to develop resistance after prolonged or repeated exposure, underscoring the significance of evaluating the sustainability of ACD as a therapeutic option. Finally, exploring combination therapies or optimized ACD formulations could improve its antimicrobial efficiency, increase stability under a variety of environmental conditions, and shed light on synergistic effects with existing antibiotics or other antimicrobial agents. Addressing these limits and uncertainties in future studies will help us better understand ACD’s therapeutic potential and function in treating biofilm-associated infections caused by multidrug-resistant pathogens.

Materials and methods

Antimicrobial activity assessment

The procedure employed to assess the antibacterial efficacy of ACD has been described in a previous publication16. The bacteria K. pneumoniae ATCC 700,603, A. baumannii ATCC 19,606, E. faecium ATCC 51,559, S. aureus ATCC 25,923, E. coli ATCC 25,922, and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27,853, were inoculated into Muller-Hinton broth and incubated until they reached an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.01. A 96-well plate was inoculated with a series of ACD dilutions at the desired concentration before being incubated with the bacterial solution. Two qualitative approaches were employed to assess antibacterial activity: the fluorescence method, which evaluates the intensity of the bacteria’s fluorescence emission in a fluorescence microplate reader, and the OD600 measurement after incubation. Before measurement, the bacteria are incubated with diluted FDA for 20 min.

Eradication of biofilm

Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) medium plus 0.2% glucose was used to inoculate P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii overnight cultures. Next, the 96-well plate was incubated until an entirely developed biofilm appeared. After incubation, the planktonic bacteria were removed, and the biofilm was treated with different concentrations of peptide and incubated for 1 h. Three techniques were used to measure biofilm degradation. First, the crystal violet staining method was used to calculate the biofilm biomass. Next, the samples were prepared for Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FE-SEM) analysis to look at the morphology of the biofilm16. In a nutshell, the biofilms on the coverslips were established first, and then water was removed by a series of washes. The samples were prepared for imaging using a TESCAN MIRA3 XMU FE-SEM. Finally, P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii biofilm were double stained using Fluorescein diacetate (FDA) and Propidium iodide (PI) for live/dead analysis16. Following the process of double staining the samples, confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) was utilized to image the biofilm structure. Images were processed using NIS-Element Viewer 4.5 imaging software.

Cell culture procedure

Two human cell lines, including human leukemia monocytic cell line (THP-1) and Calu-6, a human lung adenocarcinoma cell line, showing epithelial morphology, were cultured, respectively, in Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 (RPMI) medium and Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37 °C in 5% CO2.

THP-1 and Calu-6 monocultures model

In 96-well plates, 50,000 Calu-6 epithelial cells and 50,000 THP-1 monocytes (per well) were cultivated in RPMI 1640 medium and DMEM medium, respectively, and grew for 24 h before different treatment regimens to conduct additional research.

THP-1/Calu-6 co-cultures model

50,000 Calu-6 cells (per well) were seeded in a 96-well plate in 100 µl DMEM and grown for 24 h. Then, the medium was removed and 100 µl RPMI medium without FBS and antibiotics containing 50,000 THP-1 cells were seeded on top in Calu-6 cells. Mixtures with monocytes and epithelial cells were prepared and were grown for a determined time under different treatments to further analyze.

Cytotoxicity assessment

Three distinct techniques were used to gauge cell viability. The following provides a succinct summary of how the assays performed.

MTT assay

THP-1 and Calu-6 monocultures and co-cultures were treated with different concentrations of ACD peptide and incubated for 12 h. Then, the media were removed, and the cells were washed twice with PBS buffer. Media containing 0.5 mg/mL 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2 H-tetrazolium bromide were added and incubated for 4 h. Then the media were removed, and 100 µl of Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to each well. After 30 min of incubation, the absorbance was measured at 570 nm on a microplate reader, and cell viability was evaluated in comparison with control samples.

Fluorescent microscopy

THP-1 and Calu-6 monocultures and co-cultures were treated with various concentrations of peptides, and the cells were incubated for 12 h. The cells were twice washed with PBS buffer after the media was removed. Then, the cells were double stained for live/dead using PI and FDA. A stock solution (10 mg/mL) in acetone was used to prepare a working solution of FDA (100 µg/mL) in PBS. One µL of this solution was applied to each medium-filled well before incubating for 20 min. Following that, fluorescence microscope imaging and PI staining (50 µg/mL) were carried out.

Flow cytometry analysis

During the initial few hours of treatment, the cell viability of monocultures and co-cultures was meticulously evaluated by flow cytometry. THP-1 cells were removed from the suspension of co-cultures using centrifugation at 800 rpm for 5 min. Adherent Calu-6 cells were harvested by gentle trypsinization with a 0.05% trypsin-EDTA solution. Cells were washed with PBS buffer and suspended in a 100 µl RPMI medium. The live/dead double staining experiment was conducted by following the same methodology as described in the fluorescent microscopy section for FDA and PI staining. After staining, FCM analysis was performed, and data were analyzed by FlowJo Software.

In-vitro infection model

P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii were harvested after reaching the logarithmic phase of growth by centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 10 min. When the multiplicity of infection (MOI) was 20 for P. aeruginosa and 4 for A. baumannii, they were then suspended in 100 µL of DMEM media and added to the Calu-6 cells in a monoculture model. The infected samples were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere and treated with different concentrations of the ACD peptide at 3- and 12-hour post-infection.

Transmission electron microscopy

In order to prepare the sample for TEM analysis, coverslips were placed into each well (24-well plate) to enable cell adhesion and growth. Subsequently, DMEM high glucose media is used to seed 150,000 Calu-6 cells into each well, and the consistent distribution of cells over the coverslip is verified to ensure uniform growth. The 24-well plate is incubated for 24 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator. The old medium is gradually aspirated from each well to replace the growth media and get the cells ready for bacterial infection to ensure that no cells have detached after 24 h. Then, fresh high-glucose DMEM medium is added to each well. To introduce bacterial pathogens and allow them to interact with Calu-6 cells, except for control samples, P. aeruginosa was added to the respective wells and incubated for 1 h to allow bacterial adhesion and initial infection. The samples were labeled into two groups: treatment and infection model. For the treatment group, specific amounts of peptide were added to each well and incubated for an additional 4 h to allow peptide action. The 24-well plates were centrifuged at a gentle speed using a plate centrifuge to allow bacteria and floating cells to adhere to the coverslip. Necessary care was taken to avoid dislodging the adhered cells on the coverslips. For sample fixation, the medium and any floating debris were slowly aspirated from each well. Then, glutaraldehyde solution (2.5%) was added to each well, ensuring the coverslips were fully submerged and incubated for one hour at room temperature. Following exposure of cells to P. aeruginosa bacterium and ACD peptide, attached cells were washed with culture media and fixed in situ with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH7.2) at 4 °C for 2 h. The cells were then washed 3 times in sodium cacodylate buffer (0.1 M). Specimens were fixed in 1% buffered osmium tetroxide at 4 °C for 1 h to ensure proper fixation. The process of dehydration involved varying the percentage of ethanol from 10 to 100%. Using a diamond knife on a Leika ultramicrotome, the specimens were cut into the random, ultrathin (60 nm thick) sections, placed onto copper grids without contrast, and examined using a transmission electron microscope (TEM).

Data availability

The data associated with this article is available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Miethke, M. et al. Towards the sustainable discovery and development of new antibiotics. Nat. Rev. Chem. 5 (10), 726–749. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41570-021-00313-1 (2021).

De Oliveira, D. M. P. et al. Antimicrobial resistance in ESKAPE pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 33 (3), 19. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00181-19 (2020).

Davies, D. Understanding biofilm resistance to antibacterial agents. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2 (2), 114–122. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd1008 (2003).

Høiby, N., Bjarnsholt, T., Givskov, M., Molin, S. & Ciofu, O. Antibiotic resistance of bacterial biofilms. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 35 (4), 322–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.12.011 (2010).

Bjarnsholt, T. et al. Silver against Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Apmis 115 (8), 921–928. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0463.2007.apm_646.x (2007).

World Health Organization. Prioritization of Pathogens to Guide Discovery, Research and Development of New Antibiotics for Drug-Resistant Bacterial Infections, Including Tuberculosis (No. WHO/EMP/IAU/2017.12) (World Health Organization, 2017).

Rossiter, S. E., Fletcher, M. H. & Wuest, W. M. Natural products as platforms to overcome antibiotic resistance. Chem. Rev. 117, 19. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00283 (2017).

de Pontes, J. T. C., Borges, A. B. T., Roque-Borda, C. A. & Pavan, F. R. Antimicrobial peptides as an alternative for the eradication of bacterial biofilms of multi-drug resistant bacteria. Pharmaceutics 14 (3), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics14030642 (2022).

Lashua, L. P. et al. Engineered cationic antimicrobial peptide (eCAP) prevents Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm growth on airway epithelial cells. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 71 (8), 2200–2207. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkw143 (2016).

Greco, I. et al. Correlation between hemolytic activity, cytotoxicity and systemic in vivo toxicity of synthetic antimicrobial peptides. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69995-9 (2020).

Matsuzaki, K. Control of cell selectivity of antimicrobial peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1788 (8), 1687–1692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.09.013 (2009).

Ajish, C. et al. Cell selectivity and antibiofilm and anti-inflammatory activities and antibacterial mechanism of symmetric-end antimicrobial peptide centered on D-Pro-Pro. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 666, 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2023.04.106 (2023).

Grabowski, N. et al. Surface-modified biodegradable nanoparticles’ impact on cytotoxicity and inflammation response on a co-culture of lung epithelial cells and human-like macrophages. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 12 (1), 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1166/jbn.2016.2126 (2016).

Bobone, S. & Stella, L. Selectivity of antimicrobial peptides: a complex interplay of multiple equilibria. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1117, 11. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3588-4_11 (2019).

Savini, F. et al. Selectivity of antimicrobial peptides: association to bacterial and eukaryotic cells and cell-density dependence. Biophys. J. 110 (3), 417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2015.11.2254 (2016).

Modiri, S. et al. Multifunctional acidocin 4356 combats Pseudomonas aeruginosa through membrane perturbation and virulence attenuation: experimental results confirm Molecular Dynamics Simulation 1–21 (2020).

Kalelkar, P. P., Riddick, M. & García, A. J. Biomaterial-based antimicrobial therapies for the treatment of bacterial infections. Nat. Rev. Mater. 7 (1), 39–54. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41578-021-00362-4 (2022).

Qin, S. et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: pathogenesis, virulence factors, antibiotic resistance, interaction with host, technology advances and emerging therapeutics. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 7 (1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-022-01056-1 (2022).

Ajish, C. et al. A novel hybrid peptide composed of LfcinB6 and KR-12-a4 with enhanced antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory and anti-biofilm activities. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-08247-4 (2022).

Hancock, R. E. W., Alford, M. A. & Haney, E. F. Antibiofilm activity of host defence peptides: complexity provides opportunities. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19 (12), 786–797. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-021-00585-w (2021).

Pulido, D. et al. A novel RNase 3/ECP peptide for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm eradication that combines antimicrobial, lipopolysaccharide binding, and cell-agglutinating activities. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60 (10), 6313–6325. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00830-16 (2016).

Park, H. J., Kang, H. K., Park, E., Kim, M. K. & Park, Y. Bactericidal activities and action mechanism of the novel antimicrobial peptide Hylin a1 and its analog peptides against Acinetobacter baumannii infection. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 175, 106205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejps.2022.106205 (2022).

Chou, S. et al. Synthetic peptides that form nanostructured micelles have potent antibiotic and antibiofilm activity against polymicrobial infections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 120 (4), 120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2219679120 (2023).

Mulkern, A. J. et al. Microbiome-derived antimicrobial peptides offer therapeutic solutions for the treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Npj Biofilms Microbiomes 8 (1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-022-00332-w (2022).

Mwangi, J., Yin, Y., Wang, G., Yang, M., Li, Y., Zhang, Z. & Lai, R. The antimicrobial peptide ZY4 combats multidrugresistantPseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116 (52), 26516-26522. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1909585117 (2019).

Shi, J., Chen, C., Wang, D. et al. The antimicrobial peptide LI14 combats multidrug-resistant bacterial infections. Commun. Biol. 5, 926. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-022-03899-4 (2022).

Haney, E. F., Trimble, M. J., Cheng, J. T., Vallé, Q. & Hancock, R. E. W. Critical assessment of methods to quantify biofilm growth and evaluate antibiofilm activity of host defence peptides. Biomolecules 8 (2), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom8020029 (2018).

Ganesan, N., Mishra, B. & Felix, L. Antimicrobial peptides and small molecules targeting the cell membrane of Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 87 (2), 22. https://doi.org/10.1128/mmbr.00037-22 (2023).

Wongchai, M., Wongkaewkhiaw, S., Kanthawong, S., Roytrakul, S. & Aunpad, R. Dual-function antimicrobial-antibiofilm peptide hybrid to tackle biofilm-forming Staphylococcus epidermidis. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 23 (1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-024-00701-7 (2024).

Zou, K. et al. Activity and mechanism of action of antimicrobial peptide ACPs against Candida albicans. Life Sci. 350, 122767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2024.122767 (2024).

Arezki, Y. et al. A co-culture model of the human respiratory tract to discriminate the toxicological profile of cationic nanoparticles according to their surface charge density. Toxics 9 (9), 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics9090210 (2021).

Al-Madboly, L. A. et al. Purification, characterization, identification, and anticancer activity of a circular bacteriocin from Enterococcus thailandicus. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2020.00450 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by the National Institute of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (NIGEB) (GNo:729).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.T. and S.M. performed experiments; K.A.N. designed and developed the main idea, initiating the project; M.R. F.S. A.A. AND S.S. contributed to the cell culturing part of the study; S.G. analyzed the results of biofilm formation; H.V. contributed to the electron microscopy imaging; K.A.N. supervised the project, analyzed and interpreted all the data and wrote the manuscript; All the authors have seen and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Talaee, M., Modiri, S., Rajabi, M. et al. Selective toxicity of a novel antimicrobial peptide Acidocin 4356 against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii in human cell-based in vitro infection models. Sci Rep 15, 2450 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86115-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86115-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Heterologous expression and optimization of the antimicrobial peptide acidocin 4356 in Komagataella phaffii to target Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology (2025)