Abstract

Load frequency control (LFC) is critical for maintaining stability in interconnected power systems, addressing frequency deviations and tie-line power fluctuations due to system disturbances. Existing methods often face challenges, including limited robustness, poor adaptability to dynamic conditions, and early convergence in optimization. This paper introduces a novel application of the sinh cosh optimizer (SCHO) to design proportional–integral (PI) controllers for a hybrid photovoltaic (PV) and thermal generator-based two-area power system. The SCHO algorithm’s balanced exploration and exploitation mechanisms enable effective tuning of PI controllers, overcoming challenges such as local minima entrapment and limited convergence speeds observed in conventional metaheuristics. Comprehensive simulations validate the proposed approach, demonstrating superior performance across various metrics. The SCHO-based PI controller achieves faster settling times (e.g., 1.6231 s and 2.4615 s for frequency deviations in Area 1 and Area 2, respectively) and enhanced robustness under parameter variations and solar radiation fluctuations. Additionally, comparisons with the controllers based on the salp swarm algorithm, whale optimization algorithm, and firefly algorithm confirm its significant advantages, including a 25–50% improvement in integral error indices (IAE, ITAE, ISE, ITSE). These results highlight the SCHO-based PI controller’s effectiveness and reliability in modern power systems with hybrid and renewable energy sources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The main function of load frequency control (LFC) in interconnected power systems is to quickly minimize frequencies and tie-line power deviations after failures and load changes, and to maintain a stable and reliable working point1. Classical production power plants (thermal generators and gas units) use primary and secondary control cycles for LFCs. However, renewable energy alternatives are widely preferred in power systems today in order to prevent ever-increasing environmental pollution and solve increasing economic problems due to fuel consumption. Photovoltaic (PV) systems are more attractive in terms of renewable energy alternatives and require an effective way to address the LFC problem2.

The integration of renewable energy sources, particularly PV systems, into traditional power grids poses challenges related to frequency and voltage control due to their zero or low inertia characteristics. Addressing these challenges requires advanced control strategies, optimization algorithms, and hybrid techniques to enhance the performance of PV-integrated microgrids. In this regard, various control structures and techniques to solve the LFC problem have been studied by researchers. The early proposed methods in the literature can be listed as robust control3, pole placemen4, decentralized control5, and variable structure6. Although these techniques provide the desired performance in the power system, there are some disadvantages that make it difficult to implement them. To overcome these obstacles, alternative techniques such as artificial intelligence-based neural network, sliding mode controller, and fuzzy logic have been proposed7,8. While these techniques are effective against nonlinear factors in power systems, their complex structures and intensive calculation processes are the biggest disadvantages.

Another proposed alternative to the LFC design problem is the use of metaheuristic algorithms. The biggest advantages of these algorithms are their ability to handle nonlinear functions, their easy integration into the system, and their lack of complex structure9,10,11,12,13. Therefore, recent advancements in metaheuristic algorithms have demonstrated their effectiveness in tackling complex optimization problems in power systems. For instance, an optimized fuzzy logic controller with adaptive membership functions tuned using the sorted position-based grey wolf optimization algorithm was proposed in one of the reported studies14. The method minimizes discrepancies between reference and control signals, demonstrating improved frequency stability and efficiency in PV-based microgrids. In another study, an adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system and deep neural network-based controller, optimized using the hybrid honey badger-based grey wolf optimization algorithm was proposed15. This approach regulates output waveforms, significantly reducing errors and enhancing performance metrics such as switching time and frequency stability in microgrids. The lion algorithm was proposed in a different study16 for fractional-order proportional-integral controller which was used to design LFC in interconnected power systems. The proposed controller demonstrated superior performance in terms of convergence, gain optimization, and transient stability compared to traditional methods.

It is feasible to encounter a variety of other options that have been reported for LFC. In this context, some of the important algorithms used in literature for the LFC problem can be listed as Lyrebird optimization17, walrus optimization18, particle swarm optimization19, artificial rabbits optimization20, salp swarm algorithm21, marine predators algorithm22, modified whale optimization23, firefly24, teaching–learning based optimization25,26, and its hybrid version with local unimodal sampling27, hybrid simulated annealing based quadratic interpolation optimizer28, hybrid harmony search and cuckoo optimization29, symbiotic organism search30, Harris hawks optimizer and its enhanced version31,32, multi-verse optimizer33, imperialist competitive34, grey wolf optimization35, bees algorithm36, enhanced coyote optimizer37, honey badger38, hybrid whale optimalization algorithm with simulated annealing39, rime algorithm40, gorilla troops optimization41 and wild horse optimizer42.

Through these metaheuristic algorithms, different controller structures were designed to solve the LFC problem. Nevertheless, in most of these metaheuristic algorithms some difficulties, such as local minima trap, early convergence, and inadequate ability to search the entire scale of the problem in the higher dimensions, are encountered. Therefore, despite the advancements, limitations in robustness, convergence speed, and adaptability persist, necessitating new solutions. In this regard, this study proposes the sinh cosh optimizer (SCHO)43 as a novel solution to tune a proportional-integral (PI)44 controller for the LFC design problem.

The SCHO is one of the latest mathematical based metaheuristic optimization techniques and has been successfully applied to some engineering optimization problems. The biggest advantages of this algorithm can be listed as having a balanced exploration–exploitation, and not being affected by the nature of the problem, along with being simple and flexible. Some applications of the SCHO include automatic voltage regulator design45, prediction of biological activities46, aircraft pitch angle control47 and Parkinson’s disease detection48. Considering the success and superiority of the SCHO in engineering problems in the reported studies, this paper proposes the solution to the LFC design problem in a two-area power system consisting of PV and thermal units. The hybrid power system is modeled with Area 1 consisting of a PV-based power system, including a maximum power point tracker (MPPT), and Area 2 comprising a thermal power system with governor, turbine, reheater, and generator dynamics. The optimization objective is to minimize the integral of time-weighted absolute error (ITAE) to achieve rapid stabilization and minimal steady-state errors. Proportional (\({k}_{p1}\) and \({k}_{p2}\)) and integral (\({k}_{i1}\) and \({k}_{i2}\)) parameters of the controllers are optimized considering the boundaries adopted in the previous studies. The SCHO is initialized and its unique exploration and exploitation phases ensure efficient global optimization of the PI controller parameters. The proposed SCHO-based PI controller is tested against step load changes, parameter variations, and solar radiation fluctuations. Its performance is compared with (salp swarm algorithm-based PI21, whale optimization algorithm-based PI23 and firefly-based PI24 controllers using metrics such as settling time, overshoot, undershoot, and different error-based performance indices (IAE, ITAE, ISE, ITSE)49,50,51. Therefore, the proposed SCHO-based PI controller addresses the above-mentioned gaps, achieving faster stabilization and superior error minimization metrics compared to existing methods. The main contributions of this work include:

-

1.

The first application of the SCHO algorithm for LFC in hybrid PV-thermal systems.

-

2.

Superior performance in minimizing error-based metrics and achieving faster stabilization.

-

3.

Enhanced robustness under parameter variations and dynamic conditions, such as solar radiation fluctuations.

-

4.

Comprehensive comparison with state-of-the-art methods, demonstrating the proposed approach’s effectiveness and reliability.

Mathematical model of SCHO algorithm

SCHO consists of five important components. These can be listed as initialization phase, exploration phase, exploitation phase, bounded search strategy and switching mechanism, respectively43.

Initialization phase

Like other metaheuristic methods, SCHO starts from randomly selected candidate solutions (\(X\)), given in Eq. (1), and candidate solutions are updated in each iteration43.

Here \(N\) is the number of candidate solutions (population size), \(d\) is the number of variables in the optimization problem, and \({x}_{ij}\) is \({i}^{th}\) solution’s \({j}^{th}\) position. It is obtained as \(X=LB+rand(N,d)\times (UB-LB)\), where \(LB\) and \(UB\) represent the lower and upper bounds of the variables, respectively, and \(rand\) represents the random value between 0 and 1.

Exploration phase

In order to avoid local minima in subsequent iterations, two-stage exploration is used in SCHO and the switch value (\(T\)) is given in Eq. (2)43.

Here, floor is the rounding down function in the MATLAB program and \({t}_{max}\) is the maximum number of iterations. In the first exploration phase, position updating is done using the following definition43.

Here \({r}_{1}\) and \({r}_{2}\) are random numbers ranging from 0 to 1, \(t\) is the current iteration, \({X}_{ij}^{t}\) and \({X}_{ij}^{t+1}\) are the \({i}^{th}\) solution in the \({j}^{th}\) position for the current iteration and the next iteration, respectively. Solution \({X}_{j}^{best}\) is the best solution of the \({j}^{th}\) position. The weight factor \({W}_{1}\) is given in Eq. (4)43.

Here, \({r}_{3}\) and \({r}_{4}\) are random numbers varying between 0 and 1, and \({a}_{1}\) is a parameter that decreases according to the number of iterations and is calculated with the following definition43.

The position update of the second exploration phase of the SCHO is performed using the following definition43.

Here \({W}_{2}={r}_{6}{a}_{2}\) is the weight factor, \({a}_{2}=2\cdot \left(0.5-\frac{t}{{t}_{max}}\right)\) and \({r}_{5}\) and \({r}_{6}\) are random numbers varying between 0 and 1.

Exploitation phase

In SCHO the exploitation is performed within two stages and in the first stage, the positions are being updated via Eq. (7)43.

Here, \({r}_{7}\) and \({r}_{8}\) are random numbers that are produced within [0, 1] and \({W}_{3}\) is a weighting factor represented by Eq. (8)43.

Here, \({r}_{9}\) and \({r}_{10}\) are random numbers changing from 0 to 1. \({r}_{11}\) and \({r}_{12}\) are randomly produced numbers within [0, 1]. The second phase of the exploitation is performed with the following definition43.

Bounded search strategy

In SCHO, the potential search areas are fully discovered with the bounded search strategy. The rule for this strategy is given in Eq. (10)43.

Here, \(m\) denotes the positive integers starting from 1 and \({BS}_{1}=floor\left(\frac{{t}_{max}}{1.55}\right)\).

Switching mechanism

With this mechanism, the SCHO ensures the balance and transition between exploration and exploitation. The \(sinh\) and \(cosh\) based switching mechanism (\(A\)) used in SCHO is calculated as follows43.

Here, \({r}_{13}\) is a randomly produced number within [0, 1]. In the SCHO algorithm, the exploration phase is executed when \(A>1\) and the exploitation phase is executed when \(A<1\). The explanatory flow diagram of SCHO is shown in Fig. 1.

Modeling of photovoltaic and thermal power systems

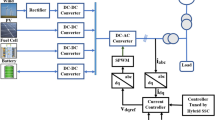

A two-zone power system model is considered to verify the effectiveness of the proposed SCHO-based controller. Area 1 consists of a PV-based system and Area 2 is a thermal power system. The transfer function of the solar PV system, which includes a PV panel, converter, filter and maximum power point tracker (MPPT), is given in Eq. (12)21,23,24.

The thermal power system in Area 2 consists of a generator, turbine, reheater and governor components. The transfer functions of these four components are defined in Eqs. (13)–(16), respectively21,23,24.

In order to make appropriate comparisons with the SSA-based PI21, WOA-based PI23 and FA-based PI24 control methods in the literature, the values of the parameters of the hybrid PV-thermal power system were chosen as \(A=18\), \(B=900\), \(C=100\), \(D=50\), \({K}_{g}=1\), \({T}_{g}=0.08\) s, \({K}_{t}=1\), \({T}_{t}=0.3\) s, \({T}_{r}=10\) s, \({K}_{r}=0.33\), \({K}_{ps}=120\) Hz/puMW, \({T}_{ps}=20\) s, \(R=2.5\) Hz/pu, \(B=0.8\) pu and \({T}_{12}=0.545\) puMW/Hz52. The block diagram of the entire system is shown in Fig. 2.

Definition of optimization problem

The traditional PI controller consists of proportional (\({k}_{p}\)) and integral (\({k}_{i}\)) parameters53. In the PV-thermal power system, one PI controller is recommended for each of the two areas. The transfer function of the PI controller in the PV system region is given in Eq. (17).

The transfer function of the PI controller in the thermal power system region is given in Eq. (18).

It is aimed to minimize frequency deviations ((\(\Delta {f}_{1}\) and \(\Delta {f}_{2}\)) and tie-line power variations (\(\Delta {P}_{tie}\)) in the hybrid PV-thermal power system by using PI controllers. In this paper, integral of time weighted absolute error (ITAE) was preferred as the objective function54 and its definition is provided as the minimization of Eq. (19).

Here, \({t}_{sim}\) represents the simulation time, and it was found sufficient to take it as 30 s in this study. The limits of the parameters of the PI controllers, given in Eq. (20), were considered during the minimization of the ITAE performance metric through the SCHO algorithm.

The interval \([-2, +2\)] was selected to ensure a fair comparison with the other approaches-based controllers, as these bounds are consistent with those used in the cited literature. This uniformity in parameter limits ensures that the results accurately reflect the optimization potential of the SCHO relative to other approaches, providing a meaningful and unbiased evaluation of its performance. The parameter bounds defined in Eq. (20) serve as constraints to ensure meaningful optimization and allow a fair comparison with other controller design methods. Additionally, the ITAE objective function minimizes frequency and tie-line power deviations, effectively constraining the system to maintain stability and desired performance metrics.

In order to find the optimal control parameters (\({k}_{p1}\), \({k}_{i1}\), \({k}_{p2}\) ve \({k}_{i2}\)) in the optimization problem and to adjust the control of the relevant system, the proposed SCHO algorithm was run 30 times, using a population size (\(N\)) of 40 and the maximum number of iterations of 50. The population size of 40 was chosen to ensure consistency with reported works in the literature, facilitating fair comparisons. Additionally, this value provides an optimal balance between performance and computational efficiency. While reducing the population size would decrease the algorithm’s effectiveness, increasing it would lead to minimal performance gains while introducing additional computational overhead. In the best run, the minimum ITAE objective function value was reached.

Figure 3 illustrates the application of the SCHO to the LFC problem in a two-area hybrid power system. The algorithm initializes with a predefined population size and maximum iterations, then iteratively minimizes the ITAE objective function by assigning optimized PI controller parameters to Area 1 and Area 2. The PI controllers regulate the system to minimize frequency deviations (\(\Delta {f}_{1}\), \(\Delta {f}_{2}\)) and tie-line power deviations (\(\Delta {P}_{tie}\)) under varying operational conditions, such as parameter variations and load changes. This block diagram provides a holistic view of the SCHO-based controller’s integration and operational workflow within the hybrid power system.

Figure 4 shows the change curve of ITAE according to the number of iterations. As can be seen from the figure, with few iterations (\({11}^{th}\) iteration), the SCHO algorithm converged to the global value (\(\text{min}\left(ITAE\right)=2.9119\)) without getting stuck in the local minimum. These results confirm the effectiveness and potential of the balanced exploration–exploitation mechanisms of the SCHO algorithm.

Simulation results

Compared methods

In order to demonstrate the stability and superiority of the proposed SCHO-based PI controller over the PV-thermal power system, comparisons were performed using three basic control methods which adopted the same system parameters and the same controller limits. The optimal values of the parameters of the proposed SCHO and the PI controllers based on SSA21, WOA23 and FA24 reported in the literature are listed in Table 1.

Case studies

A \(10\%\) step change (\(\Delta {P}_{d1}=0.1\) pu and \(\Delta {P}_{d2}=0.1\) pu) in both areas

In this case study, 10% load variations were assumed in the two areas. Comparative system responses of the power system are shown in Figs. 5, 6 and 7. The most important time performance metrics of the system are settling time (\({t}_{set}\)), undershoot (\({U}_{shoot}\)) and overshoot (\({O}_{shoot}\)). When calculating settling times, a tolerance band of ± 0.1 Hz for \(\Delta {f}_{1}\) and \(\Delta {f}_{2}\) and a tolerance band of ± 0.025 MW for \(\Delta {P}_{tie}\) were considered. Besides, the overshoot and undershoot are calculated as the maximum positive and negative deviations from the steady-state value observed during the transient response, respectively. These metrics provide insights into the system’s dynamic behavior and stability following disturbances.

In Fig. 5, frequency changes for Area 1 are plotted over time, and in Table 2, the values of comparative system metrics are provided. Compared to SSA21, WOA23 and FA24 based PI controllers in the literature, the frequency change in Area 1 (\(\Delta {f}_{1}\)) was suppressed most effectively with the proposed SCHO based PI controller at 1.6231 s. With the proposed control approach, the \({U}_{shoot}\) and \({O}_{shoot}\) values of the oscillations for the \(\Delta {f}_{1}\) signal were found to be − 0.1569 Hz and 0.0209 Hz, respectively, and these values are much lower than the values obtained with the three control approaches in the literature.

The comparative time response to the \(\Delta {f}_{2}\) change for Area 2 is given in Fig. 6 and the numerical values of the system performance metrics are given in Table 2. Looking at the relevant figure and table, the best system response belongs to the system optimized with SCHO, and the frequency change in Area 2 (\(\Delta {f}_{2}\)) is between − 0.2217 Hz and 0.0459 Hz, and the oscillations were quickly settled into the desired tolerance band in 2.4615 s.

The plots of tie-line power changes (\(\Delta {P}_{tie}\)) obtained from all control approaches over time are shown in Fig. 7. Numerical values of comparative performance metrics are listed in Table 2. Looking at the table, it is clear that the lowest values of \({t}_{set}\), \({U}_{shoot}\) and \({O}_{shoot}\) metrics are found with the proposed SCHO-based PI control approach. All graphical time responses and numerical findings obtained in this case study show that the dynamics of the system after the fault of the first recommended SCHO tuned PI controller compared to its effective competitors in the literature (PI control methods based on SSA21, WOA23 and FA24) and confirmed its superiority and potential in improving determination.

Influence of solar radiation variation

In this case study, the effectiveness and robustness of the SCHO-based controller in suppressing oscillations was tested by considering random solar radiation changes in Area 1. Figure 8 illustrates the random variations in solar radiation considered during the test period (0–80 s). These variations mimic dynamic changes in PV output, which are common due to environmental factors such as cloud cover and atmospheric conditions.

Figure 9 presents the system’s frequency deviations (\(\Delta {f}_{1}\), \(\Delta {f}_{2}\)) and tie-line power deviation (\(\Delta {P}_{tie}\)) under solar radiation fluctuations. The SCHO-based PI controller effectively suppresses oscillations, demonstrating its capability to stabilize the system within minimal settling times and low overshoot values. Therefore, the SCHO-based PI controller confirms that it has a robust control structure by successfully and quickly dampening the oscillations in the system during fluctuations in PV power production.

Comparison of well-known integral of error-based performance indices

This section evaluates the effectiveness of different optimization methods for the PI controller design in the load frequency control of a hybrid PV and thermal power system. By leveraging integral error-based performance indices (integral of absolute error (IAE), integral of time-weighted absolute error (ITAE), integral of squared error (ISE), and integral of time-weighted squared error (ITSE)) a comprehensive analysis of the controllers is performed. These indices are mathematically expressed as given in Eqs. (21), (22) and (23).

These metrics assess not only the magnitude of the error but also its impact over time, making them critical in judging controller performance in dynamic systems.

Table 3 provides a numerical comparison of the performance indices for the proposed SCHO-based PI controller against other optimization-based controllers. The results indicate that the SCHO-based PI controller outperforms the competing methods in all indices. The SCHO-based controller achieves the lowest values for both IAE and ITAE indices, reflecting minimal accumulated error and a significant reduction in time-weighted errors. This indicates a rapid and efficient suppression of system oscillations. The squared error indices of ISE and ITSE further emphasize the superiority of the SCHO-based approach. The reduced error magnitude and its time-weighted impact signify a more precise and reliable control action over the entire simulation period. The results validate the SCHO algorithm’s balanced exploration and exploitation capabilities, ensuring robust and efficient tuning of the PI controllers. By achieving superior performance in all four indices, the SCHO-based PI controller demonstrates its potential as a reliable solution for LFC challenges in hybrid power systems. The proposed method also illustrates better adaptability and robustness compared to traditional optimization techniques.

Robustness analysis under parameter variations

This section investigates the robustness of the proposed SCHO-based PI controller by examining the system’s response to parameter variations. Robustness is a critical criterion for control systems operating under diverse and unpredictable real-world conditions, as it ensures stability and performance despite variations in system parameters. The test for this section considers the fault scenario with simultaneous \(\pm 25\%\) variations in the time constants of key power system components, including the governor, turbine, reheater, and generator. These variations simulate real-world conditions where system parameters may fluctuate due to aging, maintenance, or environmental factors. Figures 10, 11, and 12 illustrate the dynamic responses of the system when subjected to parameter changes in the LFC framework.

The response of frequency deviation in Area 1 (\(\Delta {f}_{1}\)), given in Fig. 10, demonstrates the stability and adaptability of the SCHO-based controller. Despite parameter variations, the oscillations are effectively dampened, and the system quickly converges to a stable state. This indicates the controller’s ability to maintain performance, particularly in renewable energy integrated systems like PV power plants where variability is inherent.

The response for frequency deviation in Area 2 (\(\Delta {f}_{2}\)), given in Fig. 11, associated with the thermal power system, confirms the robustness of the controller in handling variations typical in thermal generation processes, such as fuel supply inconsistencies and mechanical delays. The SCHO-based controller exhibits minimal overshoot and ensures rapid stabilization, showcasing its balanced approach to parameter adaptation.

The tie-line power deviation (\(\Delta {P}_{tie}\)) response, given in Fig. 12, illustrates the controller’s capacity to stabilize inter-area power flows under parameter uncertainties. The SCHO-based controller minimizes fluctuations and achieves rapid convergence, which is critical for preventing cascading failures and ensuring reliable power exchange between areas. The robustness analysis confirms that the SCHO-based PI controller maintains superior performance under parameter variations. Key performance metrics such as settling time, overshoot, and undershoot remain within acceptable limits across all scenarios. This robustness is attributed to the SCHO algorithm’s effective exploration–exploitation balance, which ensures the controller parameters are well-optimized to handle uncertainties.

Handling of power system non-linearity

Power systems inherently exhibit nonlinear behaviors, such as governor dead-band effects, generation rate constraints, and saturations in various components. These nonlinearities can significantly impact the stability and performance of LFC strategies, making it imperative to evaluate controller robustness under such conditions. The analyses performed in this study, though focused on linear dynamics, indirectly demonstrate the proposed SCHO-based PI controller’s capability to handle nonlinearities through effective damping of oscillations, robustness to parameter variations, and adaptability to dynamic inputs.

As illustrated in “A \(10\%\) step change (\(\Delta {P}_{d1}=0.1\) pu and \(\Delta {P}_{d2}=0.1\) pu) in both areas” and “Robustness analysis under parameter variations” sections, the SCHO-based PI controller effectively minimizes overshoots and settling times under both nominal and perturbed system conditions. Nonlinearities, such as generation rate constraints, are known to exacerbate oscillatory behavior in power systems. The controller’s demonstrated ability to suppress oscillations suggests that it is well-equipped to mitigate the destabilizing effects of such nonlinearities. The robustness analysis in “Robustness analysis under parameter variations” section, which tested the controller under simultaneous parameter variations, serves as an indirect indicator of its performance under nonlinear conditions. Since parameter changes often amplify the impact of system nonlinearities, the controller’s ability to maintain stability and achieve low steady-state errors reflects its resilience to nonlinear effects. The controller’s performance under solar radiation fluctuations (“Influence of solar radiation variation” section) highlights its adaptability to dynamically changing inputs. Nonlinearities introduced by renewable energy sources, such as power output variability and intermittency, are effectively managed by the SCHO-based controller, further indicating its efficiency in nonlinear environments. Moreover, a key advantage of the SCHO is its balanced exploration–exploitation mechanism, which enables it to find global optima in complex problem spaces. Nonlinear systems often result in highly nonconvex optimization landscapes. The SCHO-based PI controller’s demonstrated superior performance in minimizing integral error-based indices (IAE, ITAE, ISE, ITSE) suggests that it can address the challenges posed by nonlinearities effectively.

Conclusions

In this paper, a novel application of the SCHO was proposed for tuning PI controllers to enhance the load frequency control in a two-area hybrid power system consisting of PV and thermal units. By addressing critical challenges such as parameter variations, solar radiation fluctuations, and nonlinear effects, the proposed SCHO-based PI controller demonstrated significant advancements over traditional optimization-based methods, including SSA, WOA, and FA. Key numerical findings that substantiate the efficacy of the proposed method can be explained as follows. Settling times of 1.6231 s and 2.4615 s for frequency deviations in Area 1 and Area 2, respectively, were achieved under step load changes, significantly outperforming the best alternative methods. The tie-line power deviation was stabilized at 1.9986 s, compared to 2.3188 s for SSA, 4.3108 s for WOA, and 2.5018 s for FA. The SCHO-based PI controller recorded the lowest IAE and ISE values at 0.9022 and 0.0773, respectively, indicating its ability to minimize both accumulated and squared errors over time. Time-weighted indices such as ITAE and ITSE further emphasized its superiority, with values of 2.9119 and 0.1097, respectively, surpassing all competing methods. Simulation results confirmed the controller’s robustness to simultaneous parameter variations in governor, turbine, and generator time constants, as well as its adaptability to solar radiation fluctuations. The SCHO algorithm’s balanced exploration and exploitation capabilities, coupled with its ability to avoid local minima, played a pivotal role in achieving these outcomes. The results conclusively establish the proposed SCHO-based PI controller as an effective and reliable solution for LFC in modern hybrid power systems.

Future studies could extend the findings of this research by explicitly incorporating nonlinearities such as governor dead-band effects, generation rate constraints, and saturations in the power system model. Additionally, the application of the SCHO to other renewable energy-integrated systems or multi-area grids with higher levels of complexity presents an exciting avenue for exploration.

Data availability

All data are available within the manuscript.

Change history

18 March 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92478-8

References

Fathy, A., Yousri, D., Rezk, H., Thanikanti, S. B. & Hasanien, H. M. A robust fractional-order pid controller based load frequency control using modified hunger games search optimizer. Energies 15, 361 (2022).

Davtalab, S., Tousi, B. & Nazarpour, D. Optimized intelligent coordinator for load frequency control in a two-area system with PV plant and thermal generator. IETE J. Res. 68, 3876–3886 (2022).

Tan, W. & Xu, Z. Robust analysis and design of load frequency controller for power systems. Electric Power Syst. Re. 79, 846–853 (2009).

Hasan, N. Design and analysis of pole-placement controller for interconnected power systems. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Adv. Eng. 2, 212–217 (2012).

Tan, W. & Zhou, H. Robust analysis of decentralized load frequency control for multi-area power systems. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 43, 996–1005 (2012).

Bengiamin, N. N. & Chan, W. C. Variable structure control of electric power generation. IEEE Trans. Power Apparatus Syst. 101, 376–380 (1982).

Andic, C., Ozumcan, S., Varan, M. & Ozturk, A. A novel sea horse optimizer based load frequency controller for two-area power system with PV and thermal units. Int. J. Robot. Control Syst. 4, 606–627 (2024).

Kumar, R. & Sikander, A. A new hybrid approach based on fuzzy logic and optimization for load frequency control. Int. J. Model. Simul. https://doi.org/10.1080/02286203.2024.2315327 (2024).

Izci, D. & Ekinci, S. The promise of metaheuristic algorithms for efficient operation of a highly complex power system. In Comprehensive Metaheuristics (eds. Mirjalili, S. & Gandomi, A.) 325–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-91781-0.00017-X (Elsevier, 2023).

Veerendar, T. & Kumar, D. CBO-based PID-F controller for load frequency control of SPV integrated thermal power system. Mater. Today Proc. 58, 593–599 (2022).

Saha, A., Dash, P., Bhaskar, M. S., Almakhles, D. & Elmorshedy, M. F. Evaluation of renewable and energy storage system-based interlinked power system with artificial rabbit optimized PI(FOPD) cascaded controller. Ain Shams Eng. J. 15, 102389 (2024).

Ahmed, M., Magdy, G., Khamies, M. & Kamel, S. Modified TID controller for load frequency control of a two-area interconnected diverse-unit power system. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 135, 107528 (2022).

Davoudkhani, I. F. et al. Maiden application of mountaineering team-based optimization algorithm optimized 1PD-PI controller for load frequency control in islanded microgrid with renewable energy sources. Sci. Rep. 14, 22851 (2024).

Sharma, D. Fuzzy with adaptive membership function and deep learning model for frequency control in PV-based microgrid system. Soft Comput. 26, 9883–9896 (2022).

Sharma, D. Frequency control in PV-integrated microgrid using hybrid optimization-based ANFIS and deep learning network. In Electric Power Components and Systems 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325008.2023.2280109 (2023).

Sharma, D. & Yadav, N. K. LFOPI controller: A fractional order PI controller based load frequency control in two area multi-source interconnected power system. Data Technol. Appl. 54, 323–342 (2020).

Sharma, A. & Singh, N. Load frequency control of connected multi-area multi-source power systems using energy storage and lyrebird optimization algorithm tuned PID controller. J. Energy Storage 100, 113609 (2024).

Dev, A. et al. Enhancing load frequency control and automatic voltage regulation in Interconnected power systems using the Walrus optimization algorithm. Sci. Rep. 14, 27839 (2024).

Dhanasekaran, B., Kaliannan, J., Baskaran, A., Dey, N. & Tavares, J. M. R. S. Load frequency control assessment of a PSO-PID controller for a standalone multi-source power system. Technologies 11, 22 (2023).

El-Sehiemy, R., Shaheen, A., Ginidi, A. & Al-Gahtani, S. F. Proportional-integral-derivative controller based-artificial rabbits algorithm for load frequency control in multi-area power systems. Fractal Fract. 7, 97 (2023).

Çelik, E., Öztürk, N. & Houssein, E. H. Influence of energy storage device on load frequency control of an interconnected dual-area thermal and solar photovoltaic power system. Neural Comput. Appl. 34, 20083–20099 (2022).

Halmous, A., Oubbati, Y., Lahdeb, M. & Arif, S. Design a new cascade controller PD–P–PID optimized by marine predators algorithm for load frequency control. Soft Comput. 27, 9551–9564 (2023).

Khadanga, R. K., Kumar, A. & Panda, S. A novel modified whale optimization algorithm for load frequency controller design of a two-area power system composing of PV grid and thermal generator. Neural Comput. Appl. 32, 8205–8216 (2020).

Abd-Elazim, S. M. & Ali, E. S. Load frequency controller design of a two-area system composing of PV grid and thermal generator via firefly algorithm. Neural Comput. Appl. 30, 607–616 (2018).

Sahu, B. K., Pati, S., Mohanty, P. K. & Panda, S. Teaching–learning based optimization algorithm based fuzzy-PID controller for automatic generation control of multi-area power system. Appl. Soft Comput. 27, 240–249 (2015).

Veerendar, T. & Kumar, D. Teaching–learning optimizer-based FO-PID for load frequency control of interlinked power systems. Int. J. Model. Simul. 43, 683–705 (2023).

Sahu, B. K., Pati, T. K., Nayak, J. R., Panda, S. & Kar, S. K. A novel hybrid LUS–TLBO optimized fuzzy-PID controller for load frequency control of multi-source power system. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 74, 58–69 (2016).

Izci, D. et al. Dynamic load frequency control in power systems using a hybrid simulated annealing based quadratic interpolation optimizer. Sci. Rep. 14, 26011 (2024).

Gheisarnejad, M. An effective hybrid harmony search and cuckoo optimization algorithm based fuzzy PID controller for load frequency control. Appl. Soft Comput. 65, 121–138 (2018).

Guha, D., Roy, P. K. & Banerjee, S. Symbiotic organism search algorithm applied to load frequency control of multi-area power system. Energy Syst. 9, 439–468 (2018).

Yousri, D., Babu, T. S. & Fathy, A. Recent methodology based Harris Hawks optimizer for designing load frequency control incorporated in multi-interconnected renewable energy plants. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 22, 100352 (2020).

Kumar, V., Sharma, V. & Naresh, R. Leader Harris Hawks algorithm based optimal controller for automatic generation control in PV-hydro-wind integrated power network. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 214, 108924 (2023).

Ali, H. H., Kassem, A. M., Al-Dhaifallah, M. & Fathy, A. Multi-verse optimizer for model predictive load frequency control of hybrid multi-interconnected plants comprising renewable energy. IEEE Access 8, 114623–114642 (2020).

Arya, Y. et al. Cascade-I λ D μ N controller design for AGC of thermal and hydro-thermal power systems integrated with renewable energy sources. IET Renew. Power Gener. 15, 504–520 (2021).

Guha, D., Roy, P. K. & Banerjee, S. Load frequency control of interconnected power system using grey wolf optimization. Swarm Evol. Comput. 27, 97–115 (2016).

Shouran, M., Anayi, F. & Packianather, M. The bees algorithm tuned sliding mode control for load frequency control in two-area power system. Energies 14, 5701 (2021).

Abou El-Ela, A. A., El-Sehiemy, R. A., Shaheen, A. M. & Diab, A. E. G. Enhanced coyote optimizer-based cascaded load frequency controllers in multi-area power systems with renewable. Neural Comput. Appl. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-020-05599-8 (2021).

Ozumcan, S., Ozturk, A., Varan, M. & Andic, C. A novel honey badger algorithm based load frequency controller design of a two-area system with renewable energy sources. Energy Rep. 9, 272–279 (2023).

Nayak, P. C., Mishra, S., Prusty, R. C. & Panda, S. Hybrid whale optimization algorithm with simulated annealing for load frequency controller design of hybrid power system. Soft Comput. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-023-09072-1 (2023).

Ekinci, S. et al. Automatic generation control of a hybrid PV-reheat thermal power system using RIME algorithm. IEEE Access 12, 26919–26930 (2024).

Can, O. & Ayas, M. S. Gorilla troops optimization-based load frequency control in PV-thermal power system. Neural Comput. Appl. 36, 4179–4193 (2024).

Tabak, A. & Duman, S. Maiden application of TID μ1 ND μ2 controller for effective load frequency control of non-linear two-area power system. IET Renew. Power Gener. 18, 1269–1291 (2024).

Bai, J. et al. A Sinh Cosh optimizer. Knowl. Based Syst. 282, 111081 (2023).

Ekinci, S., Izci, D., Can, O., Bajaj, M. & Blazek, V. Frequency regulation of PV-reheat thermal power system via a novel hybrid educational competition optimizer with pattern search and cascaded PDN-PI controller. Results Eng. 24, 102958 (2024).

Izci, D. et al. Refined sinh cosh optimizer tuned controller design for enhanced stability of automatic voltage regulation. Electr. Eng. 106, 6003–6016 (2024).

Ibrahim, R. A. et al. Boosting sinh cosh optimizer and arithmetic optimization algorithm for improved prediction of biological activities for indoloquinoline derivatives. Chemosphere 359, 142362 (2024).

Abualigah, L., Ekinci, S. & Izci, D. Aircraft pitch control via filtered proportional–integral–derivative controller design using sinh cosh optimizer. Int. J. Robot. Control Syst. 4, 746–757 (2024).

Jovanovic, L. et al. Detecting Parkinson’s disease from shoe-mounted accelerometer sensors using convolutional neural networks optimized with modified metaheuristics. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 10, e2031 (2024).

Izci, D. Design and application of an optimally tuned PID controller for DC motor speed regulation via a novel hybrid Lévy flight distribution and Nelder-Mead algorithm. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 43, 3195–3211 (2021).

Ekinci, S., Izci, D., Abualigah, L., Ghandour, R. & Salman, M. Prairie dog optimization-based tilt-integral-derivative controller for frequency regulation of power system. In 2024 8th International Artificial Intelligence and Data Processing Symposium (IDAP) 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/IDAP64064.2024.10710671 (IEEE, 2024).

Izci, D., Ekinci, S. & Hekimoğlu, B. A novel modified Lévy flight distribution algorithm to tune proportional, integral, derivative and acceleration controller on buck converter system. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control 44, 393–409 (2022).

Ekinci, S., Izci, D., Salman, M. & Hilal, H. A. Load frequency controller design of a two-area power system via artificial rabbits optimization. In 2024 Advances in Science and Engineering Technology International Conferences (ASET) 01–05. https://doi.org/10.1109/ASET60340.2024.10708668 (IEEE, 2024).

Izci, D., Köse, E. & Ekinci, S. Feedforward-compensated PI controller design for air–fuel ratio system control using enhanced weighted mean of vectors algorithm. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 48, 12205–12217 (2023).

Izci, D. & Ekinci, S. Comparative performance analysis of slime mould algorithm for efficient design of proportional–integral–derivative controller. Electrica 21, 151–159 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by European Union under the REFRESH—Research Excellence For Region Sustainability and High-Tech Industries Project via the Operational Programme Just Transition under Grant CZ.10.03.01/00/22_003/0000048; in part by the National Centre for Energy II and ExPEDite Project a Research and Innovation Action to Support the Implementation of the Climate Neutral and Smart Cities Mission Project TN02000025; and in part by ExPEDite through European Union’s Horizon Mission Programme under Grant 101139527. The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Lukas Prokop and Stanislav Misak for their exceptional supervision, project administration, and overall guidance throughout the course of this project. Their expertise and support were instrumental to its success.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Serdar Ekinci, Davut Izci: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Investigation, Writing—Original draft preparation. Mohit Bajaj, Vojtech Blazek: Validation, Supervision, Resources, Writing—Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in which Figure 3 was incorrectly captured.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ekinci, S., Izci, D., Bajaj, M. et al. Novel application of sinh cosh optimizer for robust controller design in hybrid photovoltaic-thermal power systems. Sci Rep 15, 2825 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86597-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86597-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A memorized multi-objective Sinh-Cosh optimizer for solving multi-objective engineering design problems

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

Design of a novel and robust 2-DOF PIDA controller based on enzyme action optimizer for ball position regulation in magnetic levitation systems

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

The novel controller design tuned by puma optimizer for load frequency control in two-area PV-thermal power system

Sādhanā (2025)