Abstract

Radiotherapy (RTx) is a highly effective treatment for head and neck cancer that can cause concurrent damage to surrounding healthy tissues. In cases of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC), the auditory apparatus is inevitably exposed to radiation fields and sustains considerable damage, resulting in dysfunction. To date, little research has been conducted on the changes induced by RTx in the middle ear and the underlying mechanisms involved. Dexamethasone (DEX) is widely used in clinical practice because of its immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory properties. The present study investigated the effects and underlying mechanisms of DEX delivered via intratympanic administration on RTx-induced damage to the middle ear and human middle ear epithelial (HMEE) cells. Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats were exposed to fractionated RTx (6.6 Gy/day for 5 days), and middle ear samples were collected at 1 and 4 months. Rats that received RTx presented a significant increase in the thickness of the submucosal layer in the middle ear and disorganization of the ciliated epithelium in the Eustachian tube (ET) mucosa. Importantly, intratympanic administration of DEX 30 min before RTx resulted in a lower degree of damage than that in the control group. Furthermore, DEX pretreatment downregulated the expression of cell death pathway markers in HMEE cells. Our collective results potentially support the use of DEX to reduce radiation-induced damage in the middle ear and may contribute to the development of future studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Radiotherapy (RTx) is a common treatment option for head and neck cancer (HNC)1. While this approach is effective in controlling local tumors, the treatment can adversely affect surrounding normal tissues and structures, thereby impacting the quality of life of patients2. Common side effects of RTx in the ear include radiation-induced mucositis and hearing loss due to fluid accumulation and ear canal stenosis3,4. However, to our knowledge, few studies have focused on the effects of radiation treatment on the ear.

In patients treated with RTx for HNC malignancies, the incidence of otitis media with effusion (OME) varies considerably (8–29%)5. Patients receiving radiation therapy for nasopharyngeal cancer (NPC) are particularly prone to OME, with documented rates as high as 48% in those receiving conventional radiation therapy6,7. Negm and coworkers reported the effects of different RTx modalities on the middle ear and Eustachian tube (ET) in a clinical cohort of patients with HNC8. Christensen et al. further identified a relationship between OME and ET dysfunction in RTx-treated patients and highlighted the risk of OME after RTx9.

Despite rapid technological advances, effective and complete treatment approaches for RTx-induced OME remain controversial. Conventional treatments for OME include incisional myringotomy10, tympanic aspiration11, and ventilation tube insertion12. Laser myringotomy and intratympanic steroid injection have been proposed as alternative treatment options and have demonstrated promise in a case series involving 27 patients13.

Dexamethasone (DEX), a synthetic glucocorticoid, is widely used to manage various inner ear disorders, including sudden hearing loss14, acoustic trauma15,16 and Ménière’s disease17. DEX has additionally been shown to protect hair cells in the organ of Corti from damage-induced ototoxic levels of TNF-α18,19 and preserve hearing in guinea pig models of cochlear implantation20.

Here, we investigated the effects of intratympanic DEX injection on RTx-induced middle ear damage in a rat model and established the related cell damage mechanisms via irradiated human middle ear epithelial (HMEE) cells.

Results

Intratympanic dexamethasone reduces radiation-induced middle ear damage: histopathological findings

To evaluate the effects of intratympanic (IT)-DEX on the middle ear mucosa after RTx, we examined middle ear bulla and Eustachian tube samples from the rats at 1 month and 4 months (Fig. 1). Compared with that of the control group, the submucosal layer of the middle ear was significantly increased at 4 months following RTx, as shown in Fig. 2A. Notably, the animals that received IT-DEX exhibited a significant decrease in the thickness of the submucosa layer at 4 months compared with those in the RTx treatment group (Fig. 2B; p < 0.0001).

Schematic overview of the in vivo studies on SD rats. Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats were randomly divided into control and dexamethasone (DEX) treatment groups before exposure to radiotherapy (RTx). DEX or saline (0.06 mL) was administered via intratympanic (IT) injection for 5 days at a dose of 5 mg/mL (sample volume. = 60 µL). After 30 min, the SD rats received a total cranial radiation dose of 33 Gy in five fractions (5 × 6.6 Gy) over five days. The animals were sacrificed at two different time points (1 month and 4 months) after the completion of RTx to assess both the short- and long-term effects of the combined treatment regimen on the experimental outcomes.

Hematoxylin‒eosin histological analysis of middle ear pathology after DEX-IT injection prior to radiotherapy. Representative images of the submucosal layer of the middle ear cavity at each time point following DEX injection prior to radiotherapy are shown. Following radiotherapy, a significant increase in the submucosal thickness of the middle ear was observed at 4 months, which was reduced by DEX administration in groups (A, B). (C) Hematoxylin-eosin staining was performed on the Eustachian tube (ET) at 1 and 4 months after radiotherapy. The ET thickness of the submucosa was significantly increased at both time points post-radiotherapy and markedly reduced in the DEX pretreated groups (red arrow). The scale bars represent 200 μm (upper) and 50 μm (lower). (D) Measurement and quantification of submucosal thickness in the ET. All the graphs present the means ± S.E.M.s (n = 3 per group, for a total of 15 rats). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test; ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. All the data in the graphs represent the means ± S.E.M.s (n = 5 per group, a total of 25 rats). Scale bar = 20 μm. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test; ****p < 0.0001.

Compared with those of the control group, the submucosal layer thickness of the Eustachian tube significantly increased, and epithelial damage was observed at both 1 and 4 months after RTx. Interestingly, the IT-DEX group presented markedly greater submucosal layer thickness and a relatively healthier epithelial layer than did the RTx group at both time points (Fig. 2C,D; p < 0.0001). The results indicate that IT-DEX attenuates middle ear mucosal damage in rats induced by RTx.

Cytotoxicity evaluation of dexamethasone and radiotherapy in human middle ear epithelial cells

We utilized the Sartorius IncuCyte® system to examine the cytotoxic effects of DEX and RTx on HMEE cells. First, to assess the viability of HMEE cells following DEX treatment, we conducted a Cytotox Green assay. The results revealed a dose-dependent increase in the number of dead cells in the DEX-treated group compared with the control group (Fig. 3B). Before validation of the protective effect of DEX on HMEE cells, the duration of treatment (up to 72 h) and RTx dose (10–20 Gy) were optimized. Notably, the percentage of green area per phase area increased with RTx exposure (Fig. 3C; p < 0.0001).

Analysis of the time and concentration dependence of the cytotoxicity induced by DEX and radiotherapy in human middle ear epithelial (HMEE) cells. (A) Experimental timeline of radiotherapy and dexamethasone treatment of HMEE cells. (B) HMEE cells plated in 24-well plates were incubated in media supplemented with different concentrations (0, 10, 25, 50, or 100 µg/mL) of DEX for various durations. Cell viability was measured via a Cytotox Green assay. (C) HMME cells were irradiated (10–20 Gy), and the IncuCyte® system was used for real-time monitoring of the effects of radiotherapy on the green area/phase area. The data represent the means ± S.E.M.s of three independent experiments. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test; ****p < 0.0001.

Dexamethasone effectively attenuates RTx-induced HMEE cell death

For determination of the effect of DEX on RTx-induced HMEE cell death, fluorescence levels after incubation with IncuCyte™ Cytotox Green reagent, a cyanine nucleic acid dye with high affinity for DNA, were evaluated. As shown in Fig. 4A, RTx-induced a marked increase in green fluorescence in HMEE cells (indicative of dead cells) at 48 h and 72 h (p < 0.0001), whereas pretreatment with DEX reduced the phase area per green area in relation to the control (Fig. 4B). These observations demonstrate that DEX increases the survival of HMEE cells in response to RTx-induced cell death.

Dexamethasone reduces the extent of HMEE cell death induced by radiotherapy (RTx). (A) Images of HMEE cells preincubated with 25 µg/mL DEX before exposure to RTx for 30 min, followed by staining with IncuCyte® Cytotox Green. Compared with that in cells incubated for 24 h (control), green fluorescence was significantly increased following exposure to RTx (10 Gy) at 48 h and 72 h. Cytotox Green confluence after RTx treatment was reduced in the presence of DEX. Scale bar = 300 μm. (B) Graphs indicate a time-dependent increase in green fluorescence (cell death)/phase area for 72 h. All data represent the means ± S.E.M.s of three independent experiments. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test; **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001.

Dexamethasone reduces mitochondrial ROS production induced by RTx in HMEE cells

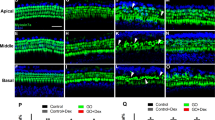

To determine whether DEX exerts antioxidant effects, we examined RTx-induced mitochondrial ROS levels in HMEE cells via live-cell imaging systems with the fluorescent dye MitoSOX™. RTx clearly promoted mitochondrial ROS production, which was attenuated upon DEX pretreatment, at 48 h and 72 h (Fig. 5A, B; p < 0.0001). Collectively, these data suggest that DEX inhibits the generation of mitochondrial ROS induced by RTx in HMEE cells.

Pretreatment with dexamethasone (DEX) ameliorates radiotherapy (RTx)-induced mitochondrial ROS production. (A) Fluorescence images of MitoSOX™ Red-stained HMEE cells exposed to DEX and RTx obtained with IncuCyte® live imaging. Representative fluorescence images showing the localization of MitoSOX™ Red fluorescence. Scale bar = 300 μm. (B) The fluorescence intensity of mitochondrial superoxide is displayed on the graph via ImageJ software. The data are presented as the means ± S.E.M.s of biologically independent samples (n = 3). Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. ns not significant, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001.

Dexamethasone affects RTx-induced cell death signaling in HMEE cells

Next, we investigated the effects of RTx and DEX treatments on apoptosis-associated proteins in HMEE cells. To this end, western blot analysis was conducted to examine cleaved caspase 3 (C-Caspase 3) protein levels. Notably, RTx significantly increased the expression of C-Caspase 3, which was completely inhibited by DEX pretreatment (Fig. 6A, B; p < 0.0001). Additionally, DEX suppressed the RTx-induced increase in the protein levels of necroptosis markers, including receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 3 (RIPK3) and phosphorylated mixed lineage kinase domain-like pseudokinase (p-MLKL) downstream of RIPK3 (Fig. 6C, D; p < 0.01). DEX further significantly decreased the increase in the protein levels of markers related to cell death signaling caused by RTx in HMEE cells.

Pretreatment with dexamethasone (DEX) affects the radiotherapy (RTx)-induced death pathway in HMEE cells. (A) HMEE cells were incubated in the absence or presence of 25 µg DEX prior to exposure to 10 Gy radiotherapy (RTx) for 72 h. Cleaved caspase 3, RIPK3, p-MLKL and TGF-β protein levels were determined via western blotting. (B–E) Measurement of the band intensities of proteins via ImageJ software. The data are presented as the means ± S.E.M.s (n = 3) of triplicate samples; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001.

Discussion

This study focused on the effects of dexamethasone (DEX) on radiation-induced middle ear damage. RTx induced mucosal damage in the middle ear bulla and Eustachian tube, which was significantly reduced by IT-DEX (Fig. 2). Pretreatment with DEX affected cell viability and mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) production triggered by RTx in HMEE cells (Figs. 3, 4 and 5) and reduced cell death via inhibition of the apoptosis and necroptosis pathways (Fig. 6).

RTx is utilized primarily as a key treatment for cancer and contributes strongly to improving patient prognosis, although its potential to cause long-term adverse effects, such as fatigue and irritation of the skin in the target area, is increasingly recognized21. In particular, RTx for head and neck or brain malignancies potentially exposes ear and brainstem regions to substantial doses of ionizing radiation22. Early radiation-induced ototoxicity is characterized by inflammation, mucosal edema, and epithelial changes in the tissues of the outer, middle, and inner ears4. While all parts of the ear may be affected, otitis media is particularly common because of irreversible changes in the middle ear mucosa23. Moreover, inflammatory responses and tissue changes induced by radiation may also contribute to the pathogenesis of otitis media with effusion (OME), with several studies reporting an association between dosimetric factors and OME24,25,26. Various therapeutic approaches have been investigated to date, including antibiotics, surgical interventions and drug delivery27,28,29. The primary objective of this study was to explore proactive strategies for preventing middle ear damage.

IT injection is an effective and minimally invasive approach for addressing various inner ear pathologies by delivering therapeutics directly into the middle ear, facilitating their rapid diffusion into the inner ear via the round window membrane30,31,32. This approach is commonly employed for targeted drug delivery, particularly for steroids, which exert anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating effects. DEX is one of the most widely utilized glucocorticoids for IT injections. This drug mediates immune suppression in the inner ear by downregulating genes involved in cytokine signaling and cell adhesion while also influencing ion homeostasis33. Thus, DEX is particularly effective for managing inflammatory conditions of the middle ear. Some studies have indicated that IT-DEX has shown promise in improving hearing outcomes in several conditions including OME, noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) and sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSNHL)34,35,36. Additionally, Han et al. evaluated the thickness of the middle ear mucosal layer following IT DEX injection combined with histamine in both mouse and in vitro models37. In the present study, IT-DEX injections effectively reduced inflammation of the middle ear bulla and Eustachian tube mucosa following RTx treatment in a rat model (Fig. 2).

RTx not only causes direct damage to cancer cells but also induces immunogenic cell death via two main pathways: regulated cell death (RCD) and accidental cell death (ACD)38. Moreover, radiation damage to the inner ear can trigger multiple pathways that promote apoptosis in immortalized organ of Corti (OC)-derived and cochlear cell lines39. A number of studies have examined the signaling pathways underlying inflammation in OME40,41. The mechanisms of glucocorticosteroid-induced apoptosis and its regulation were described in an earlier report by Distelhorst et al.42. Here, we observed increased apoptosis and necroptosis, along with activation of the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling pathway, a key mediator of fibrosis, in HMEE cells following exposure to RTx. Our findings suggest that DEX pretreatment potentially mitigates damage to the middle ear via the modulation of not only mitochondrial ROS but also the associated cellular and molecular pathways (Figs. 5 and 6).

In summary, the results of this study demonstrate that RTx induces long-term histopathological changes. Furthermore, on the basis of data from RTx-exposed HMEE cells pretreated with DEX, we propose that DEX may mitigate RTx-related middle ear side effects.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male Sprague‒Dawley (SD) rats (a total of 40 rats, 6 weeks of age) were purchased from Samtaco (Osan, South Korea). After one week of acclamation, the animals were randomly assigned to experimental groups (no radiotherapy control, radiotherapy + saline, radiotherapy + dexamethasone). All the rats were maintained in a temperature- (22 °C) and humidity-controlled (45–55%) environment under a 12 h/12 h dark‒light cycle (7:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m.) and provided pelleted food (Envigo, #2018 Teklad Global 18% Protein Rodent Diet) and water ad libitum.

All animal procedures were approved by the Chungnam National University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC, committee reference number #CNU-096). The experiments were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

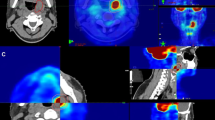

Irradiation of animals and cells

Radiotherapy was delivered via an Elekta Synergy Platform linear accelerator (Elekta, Crawley, UK) in the Radiation Oncology Department of Chungnam National University Hospital. The dose rate was Gy/min, covering the appropriate field size. The animals were randomly divided into the no RTx control, RTx + saline (intratympanic injection with normal saline), and RTx + DEX groups, with the experimental group receiving intratympanic dexamethasone (DEX) injections. A field size of 4 × 2 cm2 was used, and the animals received a total of 33 Gy of cranial radiation in five fractions (5 × 6.6 Gy) delivered over five days, with a calculated effective biological dose (α/β = 3.5) of fractionated irradiation.

The cells were irradiated at a rate of 10 Gy/min or 20 Gy/min using a field size of 30 × 30 cm2. DEX was administered 30 min prior to RTx exposure at concentrations of 0, 10, 25, 50–100 µg/ml. Following irradiation, the cells were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 environment until harvest.

Dexamethasone injection

Intratympanic injection was performed as described previously32. Briefly, SD rats were anesthetized with Alfaxan (10 mg/kg via intramuscular injection; Careside, Sungnam, South Korea) and xylazine (10 mg/kg via intramuscular injection; Bayer Animal Health, Monheim, Germany) and maintained at 37 °C on a heating pad. Dexamethasone sodium phosphate (5 mg/mL; Huons, Sungnam, South Korea) or normal saline (0.06 mL of physiologic saltwater (0.9% NaCl)) was injected into the tympanic cavity via an insulin syringe with a 31-gauge needle (BD, Seoul, South Korea).

Histopathologic examination

Samples from the middle ear and Eustachian tube of the rats were collected at 1 and 4 months post-radiotherapy. Harvested tissue samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 4 °C for 24 h and decalcified in 10% EDTA for 2 weeks at room temperature. The samples were subsequently embedded in paraffin and sectioned at a thickness of 4 μm (middle ear bulla) or 10 μm (Eustachian tube) via a mechanical implant microtome (Leica RM2235, Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). The sections were stained with hematoxylin (Sigma‒Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) according to a previously described protocol43 for evaluating morphological changes and submucosal thickness. Imaging was conducted via a slide scanner (Panoramic MIDI version 1.23, 3DHISTECH, Ltd., Budapest, Hungary), and the thickness was quantified. All histological analyses were performed via a light microscope (Olympus BX51; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) at 40x magnification.

Cell culture and live-cell imaging

Human middle ear epithelial (HMEE) cells were maintained in a mixture of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and bronchial epithelial basal medium (BEBM, Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA) at a 1:1 ratio44. The growth medium was supplemented with bovine pituitary extract (52 µg/mL), hydrocortisone (0.5 µg/mL), human epidermal growth factor (hEGF; 0.5 ng/mL), epinephrine (0.5 mg/mL), transferrin (10 µg/mL), insulin (5 µg/mL), triiodothyronine (6.5 ng/mL), retinoic acid (0.1 ng/mL), gentamycin (50 µg/mL), and amphotericin B (50 ng/mL). All the cells were maintained in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 and 95% air at 37 °C. HMEE cells were plated in 12-well plates at a density of 0.5 × 105 cells/well for cytotoxicity and MitoSOX assays or in 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well for western blot experiments.

The IncuCyte®S3 system is an image-based, real-time system that enables automatic acquisition and analysis of cellular images. Real-time assessment and quantification of the cells were performed via the IncuCyte®S3 live-cell analysis system (Sartorius, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). As cells die and lose membrane integrity, the dye penetrates and fluorescently labels the nuclei, allowing the identification and quantification of dying cells over time through the appearance of green labeled nuclei. HMEE cells were seeded in a 12-well plate and treated with DEX and Cytotox Green assay reagents the following day (EssenBioScience, Hertfordshire, UK). After 30 min of treatment, the plate was inserted into an IncuCyte®FLR for real-time imaging at 2 h intervals. Fluorescence detection of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) was conducted via MitoSOX™ Red reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), a dye that emits red fluorescence when oxidized by superoxide anions in the mitochondria. The intensity of MitoSOX™ Red fluorescence was quantified via ImageJ software.

Western blotting

Harvested cell samples were collected via centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 10 min and homogenized in lysis buffer (RIPA Lysis and Extraction Buffer, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA, #89900) supplemented with Halt™ protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA, #78442) as described previously45. After homogenization, lysates were obtained via centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 30 min. For determination of protein concentrations within the lysates, a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA, #23225) was used according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The absorbance of the samples was measured at 562 nm via a microplate reader (Tecan, Inc., Durham, NC, USA).

Protein samples (10–20 µg) prepared in protein sample buffer were loaded onto 8–12% SDS‒polyacrylamide gels (Hoefer, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) and separated, followed by transfer onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). The membranes were blocked in Tris-buffered saline with Tween®20 (TBS/T) containing 5% skim milk to prevent nonspecific binding and incubated with primary antibodies (Table 1) overnight at 4 °C to induce specific binding to the target proteins of interest. The membranes were subsequently washed with TBS/T buffer four times and then incubated with secondary antibodies (Table 1) at room temperature for 2 h. For visualization of the protein bands of interest, Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) was used, which produces a luminescent signal where the secondary antibody is bound. Chemiluminescent signals were captured and quantified via an Azure 300 Chemiluminescent Western Blot Imaging System (Azure Biosystems, Dublin, CA, USA).

Image processing and statistical analysis

All the statistical analyses and data graphing were conducted via GraphPad Prism 10 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). For histopathological analysis, Adobe Photoshop CS6 and a slide scanner program (Panoramic MIDI version 1.23, 3DHISTECH, Ltd., Budapest, Hungary) were used for adjusting the image contrast and superimposing images where necessary. The experiments were repeated multiple times, and all the measurements were obtained from distinct samples. Sample sizes were determined without preconceived expectations of the effect size. The data are presented as the means ± standard errors of the means (S.E.M.). The statistical significance of the in vivo data was assessed via one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Two-way ANOVA was used to evaluate cytotoxicity and mitochondrial ROS levels, and western blot analyses were performed. The specific types of tests performed are indicated in the figure legends. Significance was set at p < 0.05, p < 0.01, p < 0.001 and p < 0.0001, denoted *, **, *** and ****, respectively, in the figures. Data with p values > 0.05 were considered not significant.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Alfouzan, A. F. Radiation therapy in head and neck cancer. Saudi Med. J. 42, 247–254. https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2021.42.3.20210660 (2021).

Singh, G. K., Yadav, V., Singh, P. & Bhowmik, K. T. Radiation-induced malignancies making radiotherapy a two-edged sword: a review of literature. World J. Oncol. 8, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.14740/wjon996w (2017).

Brook, I. Late side effects of radiation treatment for head and neck cancer. Radiat. Oncol. J. 38, 84–92. https://doi.org/10.3857/roj.2020.00213 (2020).

Jereczek-Fossa, B. A., Zarowski, A., Milani, F. & Orecchia, R. Radiotherapy-induced ear toxicity. Cancer Treat. Rev. 29, 417–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0305-7372(03)00066-5 (2003).

Talmi, Y. P. et al. Quality of life of nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. Cancer 94, 1012–1017 (2002).

Low, W. K. & Fong, K. W. Long-term post-irradiation middle ear effusion in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Auris Nasus Larynx 25, 319–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0385-8146(98)00035-2 (1998).

Kew, J. et al. Middle ear effusions after radiotherapy: correlation with pre-radiotherapy nasopharyngeal tumor patterns. Am. J. Otol. 21, 782–785 (2000).

Negm, H., Mosleh, M., Hosni, N., Fathy, H. A. & Fahmy, N. Affection of the middle ear after radiotherapy for head and neck tumors. Egypt. J. Otolaryngol. 30, 5–9 (2014).

Christensen, J. G., Wessel, I., Gothelf, A. B. & Homoe, P. Otitis media with effusion after radiotherapy of the head and neck: a systematic review. Acta Oncol. 57, 1011–1016. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186X.2018.1468085 (2018).

Yousaf, M., Malik, S. A. & Zada, B. Laser and incisional myringotomy in otitis media with effusion—a comparative study. J. Ayub Med. Coll. Abbottabad 26, 441–443 (2014).

Gates, G. A. Acute otitis media and otitis media with effusion. Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery 3rd ed St Louis: Mosby (1998).

Schwarz, Y., Manogaran, M. & Daniel, S. J. Ventilation tubes in middle ear effusion post-nasopharyngeal carcinoma radiation: to insert or not? Laryngoscope 126, 2649–2651. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.26149 (2016).

Kuo, C. L., Wang, M. C., Chu, C. H. & Shiao, A. S. New therapeutic strategy for treating otitis media with effusion in postirradiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 75, 329–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcma.2012.04.016 (2012).

Alexiou, C. et al. Sudden sensorineural hearing loss: does application of glucocorticoids make sense? Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 127, 253–258 (2001).

Yildirim, A., Coban, L., Satar, B., Yetiser, S. & Kunt, T. Effect of intratympanic dexamethasone on noise-induced temporary threshold shift. Laryngoscope 115, 1219–1222. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MLG.0000163748.55350.89 (2005).

Zhou, Y. et al. Primary observation of early transtympanic steroid injection in patients with delayed treatment of noise-induced hearing loss. Audiol. Neurootol. 18, 89–94. https://doi.org/10.1159/000345208 (2013).

Pradhan, P., Lal, P. & Sen, K. Long term outcomes of intratympanic dexamethasone in intractable unilateral Meniere’s disease. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 71, 1369–1373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12070-018-1431-3 (2019).

Dinh, C. T. et al. Dexamethasone protects organ of corti explants against tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced loss of auditory hair cells and alters the expression levels of apoptosis-related genes. Neuroscience 157, 405–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.09.012 (2008).

Kang, B. C., Yi, J., Kim, S. H., Pak, J. H. & Chung, J. W. Dexamethasone treatment of murine auditory hair cells and cochlear explants attenuates tumor necrosis factor-alpha-initiated apoptotic damage. PLoS ONE 18, e0291780. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0291780 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Effects of a dexamethasone-releasing implant on cochleae: a functional, morphological and pharmacokinetic study. Hear. Res. 327, 89–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2015.04.019 (2015).

Majeed, H. & Gupta, V. StatPearls (2024).

Grewal, S. et al. Auditory late effects of childhood cancer therapy: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Pediatrics 125, e938–e950. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-1597 (2010).

Wright, C. G. & Meyerhoff, W. L. Pathology of otitis media. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. Suppl. 163, 24–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/00034894941030s507 (1994).

Yao, J. J. et al. Dose-volume factors associated with ear disorders following intensity modulated radiotherapy in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 5, 13525. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep13525 (2015).

Wang, S. Z. et al. Analysis of anatomical factors controlling the morbidity of radiation-induced otitis media with effusion. Radiother. Oncol. 85, 463–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2007.10.007 (2007).

Walker, G. V. et al. Radiation-induced middle ear and mastoid opacification in skull base tumors treated with radiotherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 81, e819–e823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.11.047 (2011).

Rovers, M. M. et al. Antibiotics for acute otitis media: a meta-analysis with individual patient data. Lancet 368, 1429–1435. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69606-2 (2006).

Richards, M. & Giannoni, C. Quality-of-life outcomes after surgical intervention for otitis media. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 128, 776–782. https://doi.org/10.1001/archotol.128.7.776 (2002).

Qureishi, A., Lee, Y., Belfield, K., Birchall, J. P. & Daniel, M. Update on otitis media—prevention and treatment. Infect. Drug Resist. 7, 15–24. https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S39637 (2014).

Antonelli, P. J., Winterstein, A. G. & Schultz, G. S. Topical dexamethasone and tympanic membrane perforation healing in otitis media: a short-term study. Otol. Neurotol. 31, 519–523. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181ca85cc (2010).

Hargunani, C. A., Kempton, J. B., DeGagne, J. M. & Trune, D. R. Intratympanic injection of dexamethasone: time course of inner ear distribution and conversion to its active form. Otol. Neurotol. 27, 564–569. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mao.0000194814.07674.4f (2006).

Jeong, S. H. et al. Junctional modulation of round window membrane enhances dexamethasone uptake into the inner ear and recovery after NIHL. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms221810061 (2021).

MacArthur, C., Hausman, F., Kempton, B. & Trune, D. R. Intratympanic steroid treatments may improve hearing via ion homeostasis alterations and not immune suppression. Otol. Neurotol. 36, 1089–1095. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0000000000000725 (2015).

Hembrom, R. et al. A comparative study between the efficacy of intratympanic steroid injection and conventional medical treatment in resistant cases of otitis media with effusion. Bengal J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 29, 11–16 (2021).

Lee, S. H. et al. Cochlear glucocorticoid receptor and serum corticosterone expression in a rodent model of noise-induced hearing loss: comparison of timing of dexamethasone administration. Sci. Rep. 9, 12646. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49133-w (2019).

Tsai, Y. J. et al. Intratympanic injection with dexamethasone for sudden sensorineural hearing loss. J. Laryngol. Otol. 125, 133–137. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022215110002124 (2011).

Han, J. S. et al. Safety and efficacy of intratympanic histamine injection as an adjuvant to dexamethasone in a noise-induced murine model. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 178, 106291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejps.2022.106291 (2022).

Wang, Y., Wang, Y., Pan, J., Gan, L. & Xue, J. Ferroptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis in cancer: crucial cell death types in radiotherapy and post-radiotherapy immune activation. Radiother. Oncol. 184, 109689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2023.109689 (2023).

Dinh, C. et al. Dexamethasone protects against radiation-induced loss of auditory hair cells in vitro. Otol. Neurotol. 36, 1741–1747. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0000000000000850 (2015).

Kerschner, J. E., Yang, C., Burrows, A. & Cioffi, J. A. Signaling pathways in interleukin-1beta-mediated middle ear mucin secretion. Laryngoscope 116, 207–211. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlg.0000191467.63650.9e (2006).

Kerschner, J. E., Khampang, P. & Hong, W. Dexamethasone modulation of MUC5AC and MUC2 gene expression in a generalized model of middle ear inflammation. Laryngoscope 126, E248–E254. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.25762 (2016).

Distelhorst, C. Recent insights into the mechanism of glucocorticosteroid-induced apoptosis. Cell. Death Differ. 9, 6–19 (2002).

Lyu, A. R. et al. Effects of dexamethasone on intracochlear inflammation and residual hearing after cochleostomy: a comparison of administration routes. PLoS ONE 13, e0195230. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0195230 (2018).

Chun, Y. M. et al. Immortalization of normal adult human middle ear epithelial cells using a retrovirus containing the E6/E7 genes of human papillomavirus type 16. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 111, 507–517. https://doi.org/10.1177/000348940211100606 (2002).

Lyu, A. R., Kim, J., Jung Park, S. & Park, Y. H. CORM-2 reduces cisplatin accumulation in the mouse inner ear and protects against cisplatin-induced ototoxicity. J. Adv. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2023.11.020 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research has supported by National Research Foundation (NFR) of Korea grants to M.J.P. (NRF-2020R1I1A3052557); K.S.J (NRF-RS-2023-00242668); Y.-H.P (NRF-RS-2024-00334688, NRF-RS-2024-00406568, and Chungnam National University Hospital 2023-CF-009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SJK, HCK and S-AS hypothesized, designed, performed the experiments, analyzed data, and prepared figures; JS, HCK, S-AS assisted with experiments and animal handling and performed biochemical assay; SJK and MJP conceptualized and refined hypothesis, designed research studies, data analysis and wrote manuscript; JHL, KS and Y-HP conceptualized and refined experimental design and interpretation, and edited manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

If the animal was dead before the set end point due to individual variation, the experiment would be terminated humanely by euthanasia with CO2 upon that time. We confirmed that all experiments in this study were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. All the procedure of the study is followed by the ARRIVE guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kwon, H.C., Kim, S., Jin, S. et al. Intratympanic administration of dexamethasone attenuates radiation induced damage to middle ear mucosa. Sci Rep 15, 3127 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87195-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87195-1