Abstract

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disease of unknown etiology. To identify new targets related to the initiation of CD, we screened a pair of twins with CD, which is a rare phenomenon in the Chinese population, for genetic susceptibility factors. Whole-exome sequencing (WES) of these patients revealed a mutation in their SERPINB4 gene. Therefore, we studied a wider clinical cohort of patients with CD or ulcerous colitis (UC), healthy individuals, and those with a family history of CD for this mutation by Sanger sequencing. The single-nucleotide difference in the SERPINB4 gene, which was unique to the twin patients with CD, led to the substitution of lysine by a glutamic acid residue. Functional analysis indicated that this mutation of SERPINB4 inhibited the proliferation, colony formation, wound healing, and migration of intestinal epithelial cells (IECs). Furthermore, mutation of SERPINB4 induced apoptosis and activated apoptosis-related proteins in IECs, and a caspase inhibitor significantly reduced these effects. Transcriptome sequencing revealed that the expression of genes encoding proinflammatory proteins (IL1B, IL6, IL17, IL24, CCL2, and CXCR2) and key proteins in the immune response (S100A9, MMP3, and MYC) was significantly upregulated during SERPINB4 mutant-induced apoptosis. Thus, the heterozygous SERPINB4 gene mutation causes the dysfunction of IECs, which would disrupt the intestinal epithelial barrier and contribute to the development of intestinal inflammation. The activation of SERPINB4 might represent a novel therapeutic target for inflammatory bowel disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

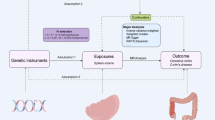

Crohn’s disease (CD), a type of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), is a lifelong progressive disease with a tendency for symptoms to flare up or subside as the condition alternates between periods of activity and remission1,2 .All segments of the gastrointestinal tract can be affected3, but the terminal ileum and colon are most commonly affected. Inflammation is typically segmental, asymmetrical, and transmural. The typical clinical manifestation of the disease is abdominal pain, chronic diarrhea, weight loss, and fatigue1. The cause of the disease is unknown, but it is believed to result from the interplay between genetic susceptibility, environmental factors, and the intestinal microbiota, resulting in an abnormal mucosal immune response and compromised epithelial barrier function1,4,5.

Recent evidence suggests that the intestinal epithelium contributes to the development and perpetuation of inflammation in IBD6,7. In addition to having a barrier function, intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) act as sensors for pathogen- and damage-associated molecular patterns and regulators of immune cells8,9,10,11. Certain genetic variations affect the function of the intestinal epithelial barrier, including mutations in the epithelial adhesion genes EPCAM and SPINT212. Specifically, disruption of epithelial pathways drives intestinal inflammation, including autophagy defects13, endoplasmic reticulum stress14, abnormal lipid antigen presentation15, and dysfunction of the inflammasome16,17. Breakdown of the epithelial barrier underpins IBD16, and abnormal intestinal permeability appears to precede the development of CD, and therefore might be involved in its pathogenesis18.

Genome-wide association studies have identified more than 320 loci that confer a higher risk of IBD19,20,21. To date, most genetic associations with IBD have been identified in individuals with European ancestry. In particular, Professor Liu’s team identified 80 IBD loci using East Asian alone, and 320 through a meta-analysis of ~ 370,000 EUR individuals (~ 30,000 cases), of which 81 were new22. However, many of these variants are likely to be rare and they require functional characterization. We previously identified heterozygous IFNA10 and IFNA4 variants that were causes of impaired function and were CD susceptibility genes in Chinese patients in a study performed in multiple centers23. These findings provide further understanding of the genetic heterogeneity that underpins CD, and other studies have shown the genetic complexity of familial CD, demonstrating a role for both common and rare variants24,25. Furthermore, a higher incidence of IBD has been identified in twin pairs and multiply affected families26. The mutant allele frequency was 43% in the healthy twins with CD, but only 9% in twins of patients with UC (p = 0.01)27. Therefore, the genetic influence on CD appears to be higher than that on UC28.

Human SERPINB4 is an evolutionarily duplicated serine/cysteine protease inhibitor that plays roles in apoptosis and autoimmunity29. Serpin polymers can also induce autophagy, and thereby may improve autoantigen presentation30,31. SERPINB3 and B4 are 98% and 92% identical with respect to their nucleotide and amino acid sequences, respectively. Because epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) is associated with greater cellular proliferation, metastasis, and resistance to anti-cancer therapy, SERPINB4 can promote cell transformation, migration, and resistance to a number of cell death-inducing agents32,33. In addition to promoting EMT, SERPINB4 has been shown to upregulate the expression of MYC34. Furthermore, oncogenic Ras-induced inflammatory cytokine production, including of IL6, IL8, PF4, and CSF2, has been shown to be mediated by SERPINB435. Because of the pleiotropic functions of serpin proteins, any mechanistic link between mutations in genes encoding serpins and the response to immunotherapy is likely to be multifaceted and complex36. In the dbSNP database, several mutant types of SERPINB4 gene have been reported, and the mutations can cause auto-aggregation and misfolding, which can lead to plaque formation, inflammatory aggregation and autophagy. Mutations in SERPINB4 can lead to a number of pathological conditions, such as inflammation-associated diseases, abnormal immune response and tumorigenesis29,37. However, the importance of SERPINB4 in intestinal epithelial cells remains unclear and requires further exploration.

Here, we describe the identification of a heterozygous SERPINB4 gene mutation that was unique to a pair of twins with CD. We found that this variant inhibits the proliferation of, and induces apoptosis in IECs, probably through increases in the expression of proinflammatory molecules. Thus, the activation of SERPINB4 might represent a novel therapeutic target for IBD.

Methods

Patients and ethics statement

A pair of twins visited our department because of recurrent diarrhea and blood in their feces of 3 years’ duration, and they were diagnosed with the ileocolonic type of CD. This diagnosis was based on standard clinical, endoscopic, radiologic, and histologic criteria, and the clinical features of the twin patients are shown in Supplementary Table 1. They developed the disease during the same year, but none of their immediate family members, including their parents, had a history of CD or other relevant illnesses (Fig. 1A). In addition, we obtained peripheral blood samples from 20 patients with CD, 10 patients with UC, 2 members of the families of patients with a history of CD, and 10 healthy individuals at the Department of Gastroenterology, Zhongshan Hospital of Xiamen University (Supplementary Table 2). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee (approval no. 2022-089) of Zhongshan Hospital of Xiamen University, Fujian Province, China. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants in the study.

Pedigree and confirmation of the SERPINB4 gene variant identified in twin patients with Crohn’s disease. (A) Pedigree of the twin patients with Crohn’s disease, “white square box” represents healthy males, “white circle” represents healthy females, and “black filled square box” represents male patients. (B) Sequencing chart for the SERPINB4 gene mutation, showing the A-to-G mutation at the 478th base. (C–D) The mutation caused the 160th amino acid to change from AAA (lysine) to GAA (glutamic acid); prediction of the protein architecture, made using Alpha Fold3 software. (E) Effect of SERPINB4 expression on the survival rate of patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma (COAD). (F) Volcano plot showing the effects of high SERPINB4 expression in intestinal epithelial cells after stimulation, according to the GEO database. (G) Effects of the high SERPINB4 expression in intestinal epithelial cells following stimulation, according to the GEO database.

Whole-exome sequencing

WES was performed on DNA extracted from peripheral blood samples from the twin patients with CD at the BGI Genomics Institute in Shenzhen, China. Efficient capture and enrichment of the entire exonic regions of the genome were achieved using liquid-phase capture systems (Agilent (Beijing, China) and BGI’s proprietary system). Subsequently, high throughput sequencing was performed using the DNBSEQTM technology platform (BGISEQ-500). The target region captured by the chip is approximately 60.46 Mb long. Variant detection was conducted within this target region, and the clean reads obtained were aligned to the human reference genome sequence GRCh37/HG19. The mean alignment rate was 99.97% and the mean sequencing depth was approximately 258.50× (Supplementary Table 3). Quality control analysis of the sequencing data met the criteria for a valid analysis.

Screening of susceptibility gene mutation sites

After confirming the quality of the sequencing data and filtering out low-quality reads, bioinformatic and gene polymorphism databases were used for their analysis. SNPs were detected in 102,986 and 125,685 locations, and indels were detected in 16,380 and 23,498 locations. Thus, SNPs accounted for the majority of variants, and most of these were heterozygous. Multiple databases were screened for susceptibility gene loci using the following two approaches. (1) Variants with MAF ≥ 1% in the 1 000 Genomes Project database, the NHLBI-ESP6500 European American population database, and the NHLBI-ESP6500 African American population database were excluded. The pathogenicity of the variants was predicted using deleteriousness prediction software (SIFT, PolyPhen2, and Mutation Assessor). Each was used to obtain a score and predict whether a particular variant or amino acid substitution would affect protein function. (2) Synonymous mutations, intergenic regions, and intron variants were filtered out, as were known SNP loci in the dbSNP database. Subsequently, the scores obtained using SIFT, PolyPhen2, and Mutation Assessor were filtered, such that the retained variants had been predicted to be deleterious by at least one of these pieces of software. We then expanded the number of DNA samples by collecting 20 from patients with CD, 10 from patients with UC, 10 from healthy controls, and 2 from the family members of patients with CD, all of which were subjected to Sanger sequencing.

Cell culture

The normal intestinal epithelium cell line NCM460 was obtained from Incell Corporation, LLC (www.incell.com) and the CRC cell line HCT116/HCT8 was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA). NCM460 cells were cultured in 1640 medium (C11875500BT, Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (ST30-3302, PAN, Germany) and 1% streptomycin/penicillin (C0222, Beyotime, China). HCT116/HCT8 cells were cultured in DMEM medium (C11995500BT, Gibco) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (ST30-3302, PAN) and 1% streptomycin/penicillin (C0222, Beyotime). And all cells were maintained at 37℃ in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

Construction of an adenoviral vector for SERPINB4 and SERPINB4-Mu overexpression

We purchased human full-length SERPINB4 (NM_002974.3) and mutant (c.478 A > G/ p.Lys160Glu) overexpression adenovirus from WZ Biosciences Inc (Shandong, China): pAdM-SERPINB4-FH-GFP and pAdM-SERPINB4-Mu-FH-GFP, with pAdM-FH-GFP as the control vector. The restriction enzyme sites used were Asisl/Mlul, and the C-terminal of the expressed proteins were fused to an HA tag. A schematic diagram and sequencing peak plots of adenovirus vectors have been provided in the Supplementary Fig. 2A,B. Viral stocks were diluted with 10% glycerol and stored in aliquots at − 80 °C until use.

Adenovirus administration and detection of transgene expression

Cells were spread in 6-well plates until the density reached 70–80%. 1 × 106 pfu/well of adenovirus with a green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene expression cassette was administered. 48 h later, cells were inspected by a fluorescent microscope. To confirm whether adenoviral vector could effectively express the target genes, we performed qPCR to detect the relative expression of the genes. Subsequent experiments were performed using these adenovirus-infected cells.

RNA sequencing (RNA seq)

NCM460 and HCT116 cells were infected with adenovirus for 48 h, followed by 24 h of incubation with apoptosis inducer (C0006S, Beyotime) at a dilution of 1:1 000. RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent and sequenced using Illumina. Eukaryotic RNA Sequencing was performed by APTBIO (Shanghai, China). This involved RNA extraction, sample testing, library construction, library quality control, sequencing, and subsequent bioinformatic analysis, which included the quantitative analysis of gene expression, differential gene expression analysis, functional enrichment analysis, and gene structure analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1). Specifically, the next-generation sequencing platform was used to sequence the transcriptome library and HISAT2 software was used to align the clean reads with the designated genome. The genome version used was Homo_sapiens_Ensembl_104 (http://may2021.archive.ensembl.org/Homo_sapiens/Info/Index).

Scratch wound healing assay of intestinal epithelial cells

Lines were drawn on the bottom of empty six-well plates using a ruler (horizontally and vertically, to divide it into three equal parts), then cells were seeded, and after they had adhered to the plate, they were infected with SERPINB4 or mutant-overexpressing adenoviruses or empty vector in triplicate. Once the cells reached 100% confluence, a 200µL yellow pipette tip was used to make a uniform scratch along the rule in each well. The detached cells were then washed away with PBS buffer. Serum-free medium was added to the wells, and then at least five images per well were captured under a microscope after 0, 24, and 48 h. The scratch wound healing rate was then analyzed using Image J software, and calculated as: (Area at 0 h − Area at 24–48 h / Area at 0 h) × 100%.

Transwell cell migration assay

After infecting intestinal epithelial cell lines with SERPINB4 or mutant-expressing adenoviruses, the cells were trypsinized, resuspended in base medium, counted, and diluted to 2.5 × 105 cells/mL. Subsequently, 200 µL of each cell suspension was added to the upper chamber of a 24-well Transwell plate, and 500 µL of complete medium was added to the lower chamber. After allowing the cells to settle for 10 min, the plate was placed in a cell culture incubator. After 48 h, the cells were fixed, stained, and counted. Each treatment was performed in triplicate, and at least five fields of view were used per well to calculate the mean number of cells for each treatment, using Image J software.

Clone formation assay

After infecting intestinal epithelial cell lines with SERPINB4 or mutant-expressing adenoviruses, the cells were then harvested and resuspended in complete medium, counted, and diluted to 250 cells/mL. Subsequently, 500 cells were seeded into each well of a six-well plate, with three replicates per treatment. The plates were placed in a cell culture incubator, and the medium was replaced every 2–3 days until the cells had been cultured for 14 days or until the majority of the individual clones consisted of > 50 cells. Subsequently, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, stained with crystal violet for 20–30 min, washed several times with PBS buffer, dried, and photographed, and the results were analyzed using Image J software.

Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

After infecting the cells with SERPINB4 or mutant-expressing adenoviruses, the cells were trypsinized and counted, then 1 000–10 000 cells were seeded into each well of a 96-well plate. The cells were divided into a medium group, a normal cell group, an experimental group, and a control group, with 6–8 per group. To prevent evaporation, 100 µL of PBS buffer or medium was added to the outer wells. The plate was incubated in a cell culture incubator, and after 0, 24, 48, 72, 96, 120, 144, and 168 h, 10 µL of CCK-8 solution was added to each well and incubated for 0.5–4 h. Finally, the OD at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader, and the viability of cells in each well was calculated.

Apoptosis assay

After infected the epithelial cell lines with SERPINB4 or mutant-expressing adenoviruses, an inducer of apoptosis (C0006S, Beyotime) was added at a dilution of 1:1 000, and the incubation time was adjusted according to the sensitivity of the cells. An Annexin-V-APC/PI detection kit (#CA011, Signalway Antibody, USA) was used to assess apoptosis, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Both the supernatants and the cells were collected, and the cell pellets were washed twice with cold PBS buffer, then 400 µL of Annexin-V binding solution was added and mixed well. From this mixture, 100 µL of cell suspension was transferred to a new tube, and in the dark, 5 µL of Annexin-V-APC solution was added and gently mixed, then incubated on ice for 10 min. After this, 5 µL of PI solution was added and gently mixed, and the mixture was incubated on ice for 5 min in the dark. After this staining, the cells were analyzed using a flow cytometer (Beckman CytoFlex S).

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay

After infecting intestinal epithelial cell lines with SERPINB4 or mutant-expressing adenoviruses, an inducer of apoptosis (C0006S, Beyotime) was added at a dilution of 1:1 000, and the incubation time was adjusted according to the sensitivity of the cells. A One-step TUNEL Apoptosis Detection Kit (red fluorescence) (C1090, Beyotime) was used, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cells were cultured in six-well plates, and after incubation with the apoptosis induced, they were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and then incubated with PBS buffer containing 0.3% Triton-X-100 for 5 min at room temperature. During this time, the TUNEL detection solution was prepared and it was added immediately after the incubation, along with an anti-evaporation membrane, and the cells were incubated in the dark at 37 °C for 60 min. After incubation, the anti-evaporation membrane was removed, and the cells were washed three times with PBS buffer. Subsequently, the cells were incubated with DAPI for 5–10 min. After three more washes with PBS buffer, the cells were mounted, examined under a fluorescence microscope, photographed, and quantified.

Western blotting

After 48 h of incubation with adenoviruses overexpressing the target gene, the intestinal epithelial cell lines were lysed in RIPA buffer (#R0010, Solarbio, China) containing protease inhibitors (CW2200, cwbio, China), phosphatase inhibitors (CW2383, cwbio), and PMSF (EA0005, Sparkjade, China). The protein concentration of each was quantified using a BCA assay (P0012, Beyotime). SDS–PAGE gels of varying concentrations were prepared according to the molecular size of the target proteins, then the lysates were electrophoresed and transferred to 0.2-µm PVDF membrane (ISEQ00010, Merck Millipore Ltd, Tullagreen, Cork, Ireland). Electrophoresis was performed at a constant voltage of 80 V and electrotransfer was performed at 250 mA for 60 min. A 5% skim milk solution was prepared in TBST and used to block the resulting membranes for 60–90 min, which were then washed three times with TBS containing 5% Tween 20. The membranes were then incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C on a shaker, and then with secondary antibody for 60–90 min at room temperature. Images were detected with WesternBright ECL HRP substrate (K-12045-D50, Advansta) on Azure 300 Imager and processed using ImageJ software with brightness/contrast adjustment applied to an entirely digital image if necessary.

Cell stimulation

Cells were spread in 6-well plates until the density reached 70–80%. After infecting the intestinal epithelial cell lines with SERPINB4 and mutant-expressing adenoviruses, the cells were treated with 100 ng/mL TNFA (PHC3016, Gibco), then the cells were harvested after 6–24 h for RNA extraction. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was then used to measure the relative mRNA expression of genes expressing inflammation-related cytokines and chemokines in each sample.

Real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using Trizol reagent (15596018CN, Invitrogen, USA). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from total RNA using Transcriptor Reverse Transcriptase (11141ES60, Yeasen, China). Real-time fluorescent quantitative PCR was performed using SYBR Green Master Mix (11202ES60, Yeasen) on an Applied Biosystems 7500 instrument. The amplification program was as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 10 s, annealing at 55–60 °C for 20 s, and extension at 72 °C for 20 s. A melting curve was then created using the default settings of the instrument. Relative gene expression was calculated with ΔΔcycle threshold normalized to GAPDH. Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 4.

Statistical analysis

The experimental data were analyzed using Prism version 8 (GraphPad) and SPSS 13 statistical software (IBM, Inc. Armonk, NY, USA). Student’s t-test was used to compare continuous datasets between two groups, and one-way ANOVA was used for three or more groups. Spearman’s rank correlation test was used to evaluate the relationships between continuous variables. The data are presented as the mean ± SD of at least three independent experiments. P < 0.05 was considered to represent statistical significance.

Results

Identification of a unique heterozygous SERPINB4 gene mutation in twin patients with CD

Through the WES of peripheral blood DNA samples from a pair of twins with CD, we obtained several candidate gene variants (data not shown), and these were further validated using a larger group of clinically obtained DNA samples (Supplementary Table 2) by Sanger sequencing. We performed bioinformatics analysis on each of these candidate genes. We identified a heterozygous SERPINB4 gene mutation that was a unique variant in the twin patients with CD. The single-nucleotide difference at the mutation site was an A-to-G mutation at the 478th base in the sequence corresponding to the NM_002974.3 transcript, leading to the substitution of lysine (AAA codon, a basic amino acid) at position 160 in the corresponding protein sequence by glutamic acid (GAA codon, an acidic amino acid) (Fig. 1B,C). As shown in Fig. 1D, we used Alpha Fold3 software to predict the changes in protein architecture that would occur following this modification. The change of a basic amino acid to an acidic one would result in an alteration to a side chain that might alter the function of the SERPINB4 protein, and this possibility should be investigated in detail.

Through an analysis of SERPINB4 in multiple public databases (Pathway Commons, KEGG, and GEO), we found that patients with colorectal cancer with high expression of SERPINB4 (N = 69) have a significant higher survival rate than those with low or medium levels of expression (N = 210) (Fig. 1E). In addition, the expression of SERPINB4 was significantly upregulated when IECs were stimulated, suggesting that it may have anti-apoptotic and pro-proliferative effects in such cells (Fig. 1F,G).

The human squamous cell carcinoma antigens (SCCA) locus on chromosome 18q21 contains two paralogous genes, SERPINB3 and B4. In mice, the corresponding locus, which is on chromosome 1D, hosts four genes (Serpinb3a, b3b, b3c, and b3d), but no SERPINB4 gene. Therefore, we established a SERPINB3 knock-in mouse model, in which the single-nucleotide change at the 478th base was mutated from A to G, as in the human SERPINB4 gene, to investigate the functional implications of this variant in vitro.

The mutation in SERPINB4inhibits the proliferation and migration of intestinal epithelial cells

To further investigate whether the growth rate and proliferative capacity of IECs are affected by the SERPINB4 variant, we overexpressed full-length SERPINB4 and SERPINB4-Mut using an adenovirus vector in normal epithelial NCM460 and colon cancer HCT116 cell lines. Adenovirus with a green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene expression cassette was administered. 48 h later, adenovirus-infected cells were inspected by a fluorescent microscope (Supplementary Fig. 2C). To confirm whether adenoviral vector could effectively express the target genes, we performed qPCR to detect the relative expression of the genes (Supplementary Fig. 2D). After this the CCK-8 assay demonstrated that infection with SERPINB4-Mut significantly inhibited the proliferation of the NCM460 and HCT116 cells vs. infection with adenovirus expressing full-length SERPINB4 or empty vector; and there was no significant difference between these (Fig. 2A,B). Furthermore, the cell colony formation experiment revealed that the number of colonies formed in the SERPINB4-Mut-infected HCT116 cells was significantly lower than that in the control vector-infected cells (Fig. 2C,D). Thus, the described mutation of SERPINB4 inhibits the proliferation and colony formation ability of IECs.

The mutation of SERPINB4 inhibits the proliferation of intestinal epithelial cells. (A) CCK-8 reagent was added to NCM460 cells, and the OD value at 450 nm was measured after 7 days to analyze the cell growth rate. (B) CCK-8 reagent was added to HCT116 cells, and the OD value at 450 nm was measured after 7 days to analyze the cell growth rate. (C) HCT116 cells were seeded on six-well plates for culture, then fixed and stained, and the number of cell clones was counted under a microscope. (D) Quantitative analysis of the number of cell clones. (E) Scratch experiments were performed on intestinal epithelial cells infected with the named adenoviruses, and photomicrographs were obtained. (F) Quantification of the area of migration of intestinal epithelial cells after 24 and 48 h. (G) Transwell cell migration experiments were performed on intestinal epithelial cells infected with the named adenoviruses, and migrating cells were identified using a fluorescence microscope. Scale bar: 100 μm; (H) Quantification of the number of migrating intestinal epithelial cells after 48 h. Data were mean ± SEM of n = 3 independent experiments. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons were used to estimate significant differences in (A–B, D, F and H), respectively. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

We next conducted this wound healing assay in NCM460 cells that were overexpressing either full-length SERPINB4, the mutant form, or the control vector, and found that the wounded area in the SERPINB4-infected culture healed faster, with a significantly larger area of migration, than control-infected cells at the 48-h time point. However, cells infected with the SERPINB4-Mut exhibited a slower healing rate and a significantly smaller area of migration than those of the other two groups. (Fig. 2E,F). To further investigate the effects of this protein on cell migration, a Transwell cell migration assay was conducted in HCT116 cells, which showed that the number of migrating cells in the mutant group was significantly lower than in the other two groups (Fig. 2G,H). Thus, the SERPINB4 mutation reduces the wound healing and migration abilities of IECs.

The mutation of SERPINB4 induces apoptosis in IECs

To further evaluate whether the SERPINB4 variant affects the function of IECs, we overexpressed full-length SERPINB4 or SERPINB4-Mut in the NCM460 cell line, then treated the cells with an inducer of apoptosis. This revealed that the proportions of early and late apoptotic cells were significantly higher in the SERPINB4-Mut-infected cells than in the SERPINB4- or control vector-infected cells (Fig. 3A,F). We then employed a TUNEL assay to detect apoptosis in the NCM460 cells, and found that the number of apoptotic cells was significantly higher in the SERPINB4 mutant-infected cells than in the SERPINB4- and control vector-infected cells (Fig. 3C,G). Thus, the SERPINB4 mutation induces apoptosis in IECs.

The mutation in SERPINB4 induces apoptosis in intestinal epithelial cells. (A) Flow cytometry was used to analyze the early, mid, and late stages of apoptosis in NCM460 after the induction of apoptosis. (B) Western blotting was performed to measure the expression of apoptosis-related proteins (BAX, BCL2, cleaved caspase 3, and cleaved PARP1 in NCM460 cells. Original gels are presented in Supplementary Fig. 3. (C) TUNEL assay with DAPI staining were used to detect apoptosis in NCM460 cells after the induction of apoptosis using a fluorescence microscope. Scale bar: 100 μm. (D) Western blotting was performed to measure the expression of apoptosis-related proteins, such as cleaved caspase 3 and cleaved PARP1 in HCT116 cells. Original gels are presented in Supplementary Fig. 3. (E) After the induction of apoptosis in NCM460, a suitable amount of caspase inhibitor (Z-VAD-FMK) was added, and the level of apoptosis was assessed using flow cytometry. (F) Quantification of the total proportion of apoptotic NCM460 cells. (G) Quantification of the TUNEL-positive rate. (H) Quantification of the level of apoptosis in NCM460 cells after the treatment of cells with caspase inhibitor. Data were mean ± SEM of n = 3 independent experiments. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons were used to estimate significant differences in (F–H). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

To elucidate the mechanism involved in the effect of SERPINB4 on apoptosis, we lysed the two types of IEC lines after infection with each of the adenoviruses and measured the expression of apoptosis-related proteins. We found that the expression of BCL2 protein was significantly lower, and those of BAX and cleaved-PARP1 were significantly higher, in the SERPINB4-Mut-infected NCM460 cells than in the control vector-infected cells (Fig. 3B). In addition, the protein expression of cleaved-caspase 3 and cleaved-PARP1 was significantly higher in the SERPINB4-Mut-infected HCT116 cells than in the control vector-infected cells (Fig. 3D). Thus, the SERPINB4 mutation induces the expression of apoptosis-related proteins in IECs.

To determine whether the effect of SERPINB4-Mut on apoptosis is mediated through caspase-3, the NCM460 cells were treated with a caspase inhibitor under the same pro-apoptotic conditions, and the effect was evaluated using flow cytometry. We found that the early apoptosis of the cells was significantly inhibited by the caspase inhibitor, because the overall proportion of apoptotic cells was not significantly increased by the SERPINB4-Mut, as described above, and there were no significant differences in the apoptosis ratios among the cell groups (Fig. 3E and H). These findings indicate that caspase inhibition largely prevents the apoptosis-inducing effect of the SERPINB4-Mut in IECs.

SERPINB4 -Mut increases the expression of genes encoding proinflammatory factors

To further explore the potential mechanisms underlying the apoptosis and cellular proliferation caused by the SERPINB4 mutation, we infected the intestinal epithelial NCM460 cells with SERPINB4- and mutant-expressing adenovirus, then induced apoptosis and performed RNA Seq. The RNA Seq analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1) revealed 268 upregulated genes and 165 downregulated genes in the SERPINB4-Mut infected cells vs. the SERPINB4-infected cells (Fig. 4A). Of these, IL23A, NLRP10, IL24, CSF2, and TNFRSF10D were highly expressed in SERPINB4-Mut-infected cells, and the differentially expressed genes were mainly related to inflammation, implicating proinflammatory pathways in the development of the enteritis caused by the SERPINB4 mutant (Fig. 4B). Functional enrichment analysis showed that the significantly differentially expressed genes in SERPINB4-Mut-infected cells were core genes involved in IgA-mediated intestinal immunity networks, cytokines, and inflammatory responses. A heatmap of the differentially expressed genes also showed that genes such as IL6, CXCR4, CXCL1, CXCL2, CSF3, and CSF2 were expressed at significantly higher levels in the mutant-infected cells (Fig. 4C–F). In addition, there were differences between the cell groups in the expression of target genes of transcription factors, including BAX, BCL2, CCL2, IL1B, and IL6 (Fig. 4G). Furthermore, the upregulated genes in the mutant group represented pathways such as cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction, and the NOD-like receptor, NF-κB, and TNF signaling pathways (Fig. 4H). Taken together, these data indicate that the expression of proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines is high during SERPINB4 mutant-induced apoptosis, consistent with it causing inflammation in IECs.

RNA sequencing analysis of NCM460 cells infected with SERPINB4- or mutant-expressing adenovirus and the induction of apoptosis. (A) Differentially expressed genes between SERPINB4-Mut and SERPINB4-overexpressing cells. (B) Clustering graph and enlarged view of the differentially expressed genes between the SERPINB4-Mut and SERPINB4-overexpressing genes. (C,E) Results of GSEA enrichment analysis and heatmaps of differentially expressed genes in the IgA-mediated intestinal immunity pathway from the KEGG database for the SERPINB4-Mut and SERPINB4-overexpressing cells. (D,F) Results of the GSEA enrichment analysis and heatmaps of differentially expressed genes in the cytokine and inflammatory response pathway from the WIKIPATHWAYS database for the SERPINB4-Mut and SERPINB4-overexpressing cells. (G) Sankey diagram of the regulatory relationships between transcription factor target genes. (H) Results of the KEGG enrichment analysis of SERPINB4-Mut and SERPINB4-overexpressing cells, displaying the top 20 significantly enriched pathway entries.

Next, we infected NCM460 and HCT116 cells with SERPINB4- or mutant-expressing adenovirus, then treated the cells with TNFA to induce apoptosis and used qPCR to measure the expression of inflammation-related genes that had been shown to be differentially expressed. We found that the relative mRNA expression of IL1B, IL6, IL17, IL24, CCL2, and CXCR2 were significantly higher in mutant-infected cells than in SERPINB4-infected cells (Fig. 5A–F), further validating the results of the transcriptome sequencing.

mRNA expression of inflammation-related genes in NCM460 and HCT116 cells infected with adenovirus expressing SERPINB4 or its mutant, followed by TNFA stimulation. (A, B) Relative mRNA expression of IL1B and IL24 in NCM460 cells. (C–F) Relative mRNA expression of IL6, IL17, CCL2, and CXCR2 in HCT116 cells. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 (One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test).

SERPINB4 -Mut increases the expression of the S100A9, MMP3, and MYC genes, which encode key regulators of the immune response

We have shown that SERPINB4-Mut increases the production of proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines in both IEC lines. We also found that the relative expression of the S100A9, MMP3, MYC, DCR1, and CSF1 genes was significantly higher in the SERPINB4-Mut-infected group than in the SERPINB4-infected group of TNFA-treated apoptotic NCM460 cells (Fig. 6A–E).

S100A9, MMP3, MYC, and DCR1 play crucial roles in the regulation of immune responses and the development of inflammation. The high expression of these key genes in mutant-infected cells is consistent with the SERPINB4 mutation promoting apoptosis in IECs and disrupting the IEC barrier. The increase in the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines likely promotes the expression of S100A9, MMP3, MYC, and DCR1, which in turn may have a significant effect on inflammation in IECs.

Discussion

IBD is a genetically complex disease, and more than 240 IBD susceptibility loci have been identified to date38. Most genetic associations with IBD have been identified through studies of individuals of EUR ancestry. A recent study identified 80 IBD loci in EAS alone and 320 in a meta-analysis of ~ 370,000 EUR individuals (~ 30,000 cases), of which 81 were new22. However, many of these gene variants are likely to be rare in Chinese patients with CD, and further functional studies are required. To further investigate the etiology and pathogenesis of CD in Chinese people, we have attempted to identify genetic susceptibility factors in this population. Initially, we used the platform of the BGI Genomics Institute in Shenzhen to perform whole-exome sequencing of DNA from a pair of twins diagnosed with CD at our hospital, which is a rare occurrence in the Chinese population. Subsequently, Sanger sequencing was performed on a wider selection of clinical DNA samples in an attempt to corroborate the findings.

In total, 23 susceptibility gene loci were identified, and 18 of these loci were potentially unique to the twin patients. One of these was an A-to-G mutation of the SERPINB4 gene at the 478th base in the corresponding NM_002974.3 transcript, resulting in a change from a lysine to a glutamic acid residue at amino acid position 160 in the protein, representing a switch from a basic to an acidic amino acid. This change may cause alterations in protein structure and function, which should be investigated in future research. SERPINB4 is a serine/cysteine protease inhibitor that inhibits inflammation by reducing cathepsin activity. However, the specific mechanism involved requires further in-depth exploration. Furthermore, it remains to be determined how an alteration in SERPINB4 protein expression affects disease behavior.

SCCA 1 and 2 (SERPIN B3 and B4) are members of the ovalbumin serpin (ov-serpin)/clade B serpin family that inhibit cell death, enhance cell growth, induce EMT, and inhibit the defense against tumors and parasites39. Mice do not have the SERPINB4 gene, and therefore we established a SERPINB3 knock-in mouse model, incorporating the single-nucleotide change identified in the SERPINB4 gene in the twin patients with CD. Using the derived cells to explore the effects of the SERPINB4 mutation in vitro, we found that the cell growth rate and proliferation and the migration ability of IECs were reduced by this mutation, whereas the apoptosis of the IECs was significantly increased. This variant was found to promote the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines, which might lead to damage to the intestinal epithelial barrier, thereby further promoting the development of inflammation.

SERPINB4 has previously been shown to increase the expression of MYC, and thereby stimulate EMT34, and more marked apoptosis was induced after the infection of epithelial cell lines with SERPINB4 mutant-expressing adenovirus than after infection with normal SERPINB4. RNA Seq revealed higher expression of multiple genes related to the inflammatory response, such as MYC, S100A9, DCR1, MMP3, and CSF1. Recent studies have shown that S100A9 plays a prominent role in the regulation of inflammatory processes and the immune response40,41,42. Its primary extracellular effects are proinflammatory43 and the induction of apoptosis44. RNA Seq results also suggest that SERPINB4 mutation activates multiple pathways including the IL17 signaling pathway and TNF signaling pathway. In SERPINB4-Mu subgroups, these signaling pathways were largely enriched. The activation of these pathways widely stimulates multiple signaling pathways in a variety of cancer cells, participates in the proliferation, metastasis and regulates the immune escape of tumor cells45,46. Binding to TLR4 and AGER activates the MAP kinase and NF-κB signaling pathways, resulting in the further activation of proinflammatory pathways. S100A9 induces cell death via autophagy and apoptosis, and this involves cross-talk between mitochondria and lysosomes, mediated through reactive oxygen species and BNIP3. In addition, it regulates neutrophil number through an anti-apoptotic effect47,48. MYC is a proto-oncogene which encodes a nuclear phosphoprotein that plays a role in cell cycle progression, apoptosis, and cellular transformation49,50. MMP3 is a metalloproteinase with broad substrate specificity that plays a significant role in autoimmune diseases51,52. Finally, DCR1, also known as TNFRSF10C, is a member of the TNF receptor superfamily, and although it does not induce apoptosis53, it is a p53-regulated gene and its expression is induced by DNA damage54.

We also found that the expression of IL1B, IL6, IL17, IL24, CCL2, and CXCR2 was high in the SERPINB4 mutant-infected cells, and there were significant differences in IgA-mediated intestinal immunity, cytokine and inflammatory response, autophagy, and toll-like receptor signaling pathways. The results of the present study provide important insight into the effects of the described SERPINB4 mutation to promote enteritis and the mechanisms involved. Furthermore, the activation of SERPINB4 might represent a novel therapeutic target for IBD.

It has been reported that SERPINB4 inhibits granzyme M through its specific reaction center loop32. Granzyme is a key cytotoxic effector molecule released by CD8+ T-cells and NK-cells upon recognition of malignant cells, which can effectively trigger tumor cell death55. Moreover, granzyme M from NK cells enhances the inflammatory cascade downstream of the LPS-TLR4 signaling pathway, leading to lethal endotoxemia56. In this study, overexpression of SERPINB4-Mu impaires the proliferation and induces apoptosis. Therefore, in the absence of granzyme, wild type SERPIINB4 still maintains cellular homeostasis, but the way of its activation still needs to be further investigated.

In normal physiological state, SERPINB4 in the colonic mucosa is usually maintained at a low level32. It is important to maintain the normal physiological function of the intestine, protect the intestine from damage and regulate intestinal immune homeostasis. When the intestine is stimulated by inflammatory factors, SERPINB4 expression is up-regulated, and SERPINB4 may be involved in intestinal mucosal repair and immunoregulation processes during the development of inflammation. It should be noted that due to the wide variety of intestinal inflammatory diseases other than IBD and the differences in pathogenesis, clinical manifestations and treatment options among different diseases, the levels of SERPINB4 in these diseases may also differ. In future studies, it is necessary to further delve into the specific mechanism of SERPINB4’s roles in intestinal inflammatory diseases, as well as its potential application value in disease diagnosis, treatment and prognostic assessment.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CD:

-

Crohn’s disease

- IBD:

-

Inflammatory bowel disease

- IECs:

-

Intestinal epithelial cells

- EMT:

-

Epithelial–mesenchymal transition

- CCK-8:

-

Cell counting kit-8

- qPCR:

-

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- RNA Seq:

-

RNA sequencing

- SCCA:

-

Squamous cell carcinoma antigens

- SERPINB4 -Mut :

-

SERPINB4 mutation

- TUNEL:

-

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling

- UC:

-

Ulcerous colitis

- WES:

-

Whole-exome sequencing

References

Torres, J., Mehandru, S., Colombel, J. F. & Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Crohn’s disease. Lancet 389, 1741–1755. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31711-1 (2017).

Agrawal, M., Spencer, E. A., Colombel, J. F. & Ungaro, R. C. Approach to the management of recently diagnosed inflammatory bowel Di sease patients: A user’s guide for adult and pediatric gastroenterolog ists. Gastroenterology 161, 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2021.04.063 (2021).

Jia, K. & Shen, J. Transcriptome-wide association studies associated with Crohn’s disease: Challenges and perspectives. Cell. Biosci. 14, 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13578-024-01204-w (2024).

Roda, G. et al. Crohn’s disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 6, 22. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-020-0156-2 (2020).

Armstrong, H. et al. Host immunoglobulin G selectively identifies pathobionts in pediatric inflammatory bowel diseases. Microbiome 7 (1). ARTN 110.1186/s40168-018-0604-3 (2019).

Dotti, I. et al. Alterations in the epithelial stem cell compartment could contribute to permanent changes in the mucosa of patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut 66, 2069–2079. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312609 (2017).

Martini, E., Krug, S. M., Siegmund, B., Neurath, M. F. & Becker, C. Mend your fences: The epithelial barrier and its relationship with mucosal immunity in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 4, 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.03.007 (2017).

Ostvik, A. E. et al. Intestinal epithelial cells express immunomodulatory ISG15 during active ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. J. Crohns Colitis 14, 920–934. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa022 (2020).

Peterson, L. W. & Artis, D. Intestinal epithelial cells: Regulators of barrier function and immune homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 14, 141–153. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri3608 (2014).

Allaire, J. M. et al. The intestinal epithelium: Central coordinator of mucosal immunity. Trends Immunol. 39, 677–696. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2018.04.002 (2018).

Graham, D. B. & Xavier, R. J. Pathway paradigms revealed from the genetics of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 578, 527–539. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2025-2 (2020).

Holt-Danborg, L. et al. SPINT2 (HAI-2) missense variants identified in congenital sodium diarrhea/tufting enteropathy affect the ability of HAI-2 to inhibit prostasin but not matriptase. Hum. Mol. Genet. 28, 828–841. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddy394 (2019).

Kabat, A. M., Pott, J. & Maloy, K. J. The mucosal immune system and its regulation by autophagy. Front. Immunol. 7, 240. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2016.00240 (2016).

Hooper, K. M., Barlow, P. G., Henderson, P. & Stevens, C. Interactions between Autophagy and the unfolded protein response: Implications for inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 25, 661–671. https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izy380 (2018).

Iyer, S. S. et al. Dietary and microbial oxazoles induce intestinal inflammation by modulating aryl hydrocarbon receptor responses. Cell 173, 1123–1134e1111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.04.037 (2018).

Parikh, K. et al. Colonic epithelial cell diversity in health and inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 567, 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-0992-y (2019).

Rathinam, V. A. K. & Chan, F. K. Inflammasome, inflammation, and tissue homeostasis. Trends Mol. Med. 24, 304–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmed.2018.01.004 (2018).

Turpin, W. et al. Increased intestinal permeability is associated with later development of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 159, 2092–2100.e2095. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.08.005 (2020).

Furey, T. S., Sethupathy, P. & Sheikh, S. Z. Redefining the IBDs using genome-scale molecular phenotyping. Nat. Rev. Gastro Hepat. 16, 296–311. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-019-0118-x (2019).

Hu, S. X. et al. Inflammation status modulates the effect of host genetic variation on intestinal gene expression in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Commun. 12, 1122 (2021).

Somineni, H. K. et al. Whole-genome sequencing of African americans implicates differential genetic architecture in inflammatory bowel disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 108, 431–445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.02.001 (2021).

Liu, Z. et al. Genetic architecture of the inflammatory bowel diseases across east Asian and European ancestries. Nat. Genet. 55, 796–806. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-023-01384-0 (2023).

Xiao, C. X. et al. Exome sequencing identifies novel compound heterozygous IFNA4 and IFNA10 mutations as a cause of impaired function in Crohn’s disease patients. Sci Rep-Uk 5, 10514 (2015).

Levine, A. P. et al. Genetic complexity of Crohn’s disease in two large Ashkenazi jewish families. Gastroenterology 151, 698–709. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.06.040 (2016).

Brand, E. C. et al. Healthy cotwins share gut microbiome signatures with their inflammatory bowel disease twins and unrelated patients. Gastroenterology 160, S721–S721 (2021).

Annese, V. Genetics and epigenetics of IBD. Pharmacol. Res. 159, 104892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104892 (2020).

Jess, T. et al. Disease concordance, zygosity, and NOD2/CARD15 status: Follow-up of a population-based cohort of Danish twins with inflammatory bowel disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 100, 2486–2492. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00224.x (2005).

Halfvarson, J., Bodin, L., Tysk, C., Lindberg, E. & Järnerot, G. Inflammatory bowel disease in a Swedish twin cohort: A long-term follow-up of concordance and clinical characteristics. Gastroenterology 124, 1767–1773. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-5085(03)00385-8 (2003).

Riaz, N. et al. Recurrent SERPINB3 and SERPINB4 mutations in patients who respond to anti-CTLA4 immunotherapy. Nat. Genet. 48, 1327–1329. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3677 (2016).

Iversen, O. J., Lysvand, H. & Slupphaug, G. Pso p27, a SERPINB3/B4-derived protein, is most likely a common autoantigen in chronic inflammatory diseases. Clin. Immunol. 174, 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2016.11.006 (2017).

Gatto, M. et al. Serpins, immunity and autoimmunity: Old molecules, new functions. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 45, 267–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-013-8353-3 (2013).

Sun, Y., Sheshadri, N. & Zong, W. X. SERPINB3 and B4: from biochemistry to biology. Semin Cell. Dev. Biol. 62, 170–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.09.005 (2017).

Chuang, T. P. et al. ALK fusion NSCLC oncogenes promote survival and inhibit NK cell responses via SERPINB4 expression. P Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2216479120. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2216479120

Turato, C. et al. SerpinB3 and yap interplay increases myc oncogenic activity. Sci. Rep. 5, 17701. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep17701 (2015).

Ray, R. et al. Uteroglobin suppresses SCCA gene expression associated with allergic asthma*. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 9761–9764. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.C400581200 (2005).

Sivaprasad, U. et al. SERPINB3/B4 contributes to early inflammation and barrier dysfunction in an experimental murine model of atopic dermatitis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 135, 160–169. https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2014.353 (2015).

Fidalgo, F. et al. Family-based whole-exome sequencing identifies rare variants potentially related to cutaneous melanoma predisposition in Brazilian melanoma-prone families. Plos One. 17, e0262419. ARTN e026241910.1371/journal.pone.0262419 (2022).

Lee, J. C. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies distinct genetic contributions to prognosis and susceptibility in Crohn’s disease. Nat. Genet. 49, 262–268. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3755 (2017).

Izuhara, K. et al. Squamous cell Carcinoma Antigen 2 (SCCA2, SERPINB4): An emerging biomarker for skin inflammatory diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 1102. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19041102 (2018).

Bao, X. W. et al. An immunometabolism subtyping system identifies S100A9 + macrophage as an immune therapeutic target in colorectal cancer based on multiomics analysis. Cell Rep. Med. 4, 100987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2023.100987 (2023).

Marinkovic, G. et al. S100A9 links inflammation and repair in myocardial infarction. Circ. Res. 127, 664–676. https://doi.org/10.1161/Circresaha.120.315865 (2020).

Chen, Y., Ouyang, Y. Z., Li, Z. X., Wang, X. F. & Ma, J. S100A8 and S100A9 in cancer. Bba-Rev Cancer 1878, 188891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.188891 (2023).

Franz, S., Ertel, A., Engel, K. M., Simon, J. C. & Saalbach, A. Overexpression of S100A9 in obesity impairs macrophage differentiation via TLR4-NFkB-signaling worsening inflammation and wound healing. Theranostics 12, 1659–1682. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.67174 (2022).

Zhong, C. R. et al. S100A9 derived from chemoembolization-induced hypoxia governs mitochondrial function in hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Adv. Sci. 9, e2202206. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202202206 (2022).

Masola, V., Greco, N., Tozzo, P., Caenazzo, L. & Onisto, M. The role of SPATA2 in TNF signaling, cancer, and spermatogenesis. Cell. Death Dis. 13, 977. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-022-05432-1 (2022).

Amatya, N., Garg, A. V. & Gaffen, S. L. IL-17 signaling: The Yin and the Yang. Trends Immunol. 38, 310–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2017.01.006 (2017).

Gong, C. et al. S100A9(-/-) alleviates LPS-induced acute lung injury by regulating M1 macrophage polarization and inhibiting pyroptosis via the TLR4/MyD88/NFκB signaling axis. Biomed. Pharmacother 172, 116233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2024.116233 (2024).

Wang, G. et al. S100A9 aggravates early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage via inducing neuroinflammation and inflammasome activation. iScience 27, 109165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2024.109165 (2024).

Oncel, S. et al. Efficacy of butyrate to inhibit colonic cancer cell growth is cell type-specific and apoptosis-dependent. Nutrients 16, 529. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16040529 (2024).

Khan, F., Pandey, P., Verma, M. & Upadhyay, T. K. Terpenoid-mediated targeting of STAT3 signaling in cancer: An overview of Preclinical studies. Biomolecules 14, 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom14020200 (2024).

Liu, M. L., Wilson, N. O., Hibbert, J. M. & Stiles, J. K. STAT3 regulates MMP3 in Heme-Induced endothelial cell apoptosis. Plos One. 8, e71366 (2013). doi:ARTN e7136610.1371/journal.pone.0071366.

Lerner, A., Neidhöfer, S., Reuter, S. & Matthias, T. MMP3 is a reliable marker for disease activity, radiological monitoring, disease outcome predictability, and therapeutic response in rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract. Res. Cl. Rh. 32, 550–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2019.01.006 (2018).

Sheridan, J. P. et al. Control of TRAIL-induced apoptosis by a family of signaling and decoy receptors. Science 277, 818–821. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.277.5327.818 (1997).

Willms, A. et al. Impact of p53 status on TRAIL-mediated apoptotic and non-apoptotic signaling in cancer cells. Plos One 14, e0214847. ARTN e021484710.1371/journal.pone.0214847 (2019).

de Poot, S. A., Bovenschen, N. & Granzyme, M. Behind enemy lines. Cell. Death Differ. 21, 359–368. https://doi.org/10.1038/cdd.2013.189 (2014).

Anthony, D. A. et al. A role for granzyme M in TLR4-driven inflammation and endotoxicosis. J. Immunol. 185, 1794–1803. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1000430 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81970460), the Natural Science Foundation Program, Fujian Province (no. 2023J011598), and the Key Laboratory of Intestinal Microbiome and Human Health in Xiamen, China.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81970460), the Natural Science Foundation Program, Fujian Province (no. 2023J011598), and the Key Laboratory of Intestinal Microbiome and Human Health in Xiamen, China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OXM, LJH and LY performed the major experiments; ZXL, HYN, LLY, HYD, XGJ, MP and YZY assisted with the experiments; and OXM and LJH assisted with the draft of the manuscript. GB revised the manuscript and supervised this study. All the authors have read and approved the final submitted manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee (approval no. 2022-089) of Zhongshan Hospital of Xiamen University, Fujian Province, China. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants in the study.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to publish

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication of the Supplementary Table 1.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ouyang, XM., Lin, JH., Lin, Y. et al. The SERPINB4 gene mutation identified in twin patients with Crohn’s disease impaires the intestinal epithelial cell functions. Sci Rep 15, 2638 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87280-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87280-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

CCL8 suppresses ovarian cancer progression via M1 macrophage polarization and NF-κB-mediated apoptosis

Scientific Reports (2025)